Introduction

The active anti-Semitism which flared up quickly after the German occupation did not falter. Lithuanians are voluntarily and untiringly at our disposal for all measures against Jews, sometimes they even execute such measures on their own.

Report from OTTO STAHLECKER, commander of Einsatzgruppe A1

Stahlecker’s report highlights the complexity of understanding the behavior of perpetrators and collaborators in the East: an SS officer praising the readiness of local Lithuanians to participate in the murder of their Jewish neighbors. This development particularly pleased Stahlecker as he had previously noted the relative difficulty of “organizing” pogroms. Naturally, he does not mention those who helped or rescued Jews. Yet one must understand each of these groups to truly view the Holocaust in Eastern Europe in its proper historical context. This requires empathy, the ability to view the world through their eyes and worldviews; empathy differs from sympathy in that we are not required to feel pity, sadness, or concern (at least not for perpetrators and collaborators).

The report above explicitly mentions perpetrators (“German occupation”), collaborators (“Lithuanians”), and victims (“Jews”). It does not mention bystanders. I argue that there is no such thing as a bystander and will abandon the “perpetrators, victims, bystanders” paradigm followed by many prominent historians.2 “Bystander” implies a neutral observer not taking part yet everyone exposed to the Holocaust took part in some way, albeit on a broad spectrum from rescue to murder. Put another way, a man in a crowd watching the Lietūkis garage massacre in Kaunas is participating as an onlooker. He gives approval as a spectator by not leaving. If we view acts of genocide as communal behavior, this approval is an important factor. Our observer’s actions certainly do not equal a killer’s, but they move him toward to the perpetrator side. Conversely, if the same observer threw up his hands in disgust and walked away, we would not consider him a rescuer or resister, but his actions move him toward him to that side. Neither action killed or saved a victim, but nor are they neutral. One cannot, simply put, ever be completely neutral.

Those non-Germans choosing to side with the invaders also placed themselves along a spectrum of complicity for a variety of reasons. Only recently have researchers examined this group more closely. Unlike German perpetrators, Eastern Europeans who collaborated with the Nazis occupy a more complicated place in their own national histories as well.

Indeed, many Holocaust survivors have more bitter memories of neighbors and local populations who ignored, victimized, or marginalized them than of Nazis that sought to kill them. Paradoxically, there are very few Jews who survived the Holocaust without the help of at least one (and quite often many) non-Jews who frequently did so in the face of very real danger. Studies into these rescuers, those who helped or saved Jews, are also complex. All kinds of people became rescuers and saved Jews for a variety of reasons.

This chapter offers a brief overview of behaviors and motivations of perpetrators, collaborators, and rescuers in Eastern Europe. This discussion must be, by its very nature, somewhat sweeping, for scholars have dedicated mountains of research and countless studies to all three groups. Indeed, while sharing important similarities, specific places and times and longer histories inextricably link the phenomena of perpetration, collaboration, and rescue. Thus, I will not attempt to present an exhaustive treatment of any group but will rather sketch out the important roles individuals and groups played in the Holocaust in the East as well as some of the scholarly explanations for why they made the choices they did.

“I never saw Stangl hurt anyone,” he said at the end. “What was special about him was his arrogance. And his obvious pleasure in his work and his situation. None of the others—although they were, in different ways, so much worse than he—showed this to such an extent. He had this perpetual smile on his face . . . No, I don’t think it was a nervous smile; it was just that he was happy.”

STAN SZMAJZNER, Treblinka survivor, on camp commandant, Franz Stangl3

Studies of perpetrators initially dominated Holocaust history. After all, without perpetrators, there would have been no Holocaust. Perpetrator studies sought to understand or explain the behavior of men such as Stangl and the seemingly inexplicable mentalities that Szmajzner observed. How could someone responsible for a camp that murdered thousands each day be “happy?” Addressing the behavior and motivations of the killers requires an understanding not only of history but also of psychology.

The label of “perpetrator” encompasses a broad array of positions, organizations, and behaviors. For our purposes, a perpetrator (or a perpetrator organization) directly furthered the Nazi genocidal project, including primarily the Holocaust, but also other policies directed against Sinti/Roma, Slavs, Soviet POWs, the handicapped, homosexuals, and others. Many of these individuals were not German, and will be discussed in the section on collaborators.

Who were the perpetrators? We have already encountered many: the Einsatzgruppen, the German Army, the SS, and camp personnel. Yet, others were not engaged directly in the physical murder of Jews but were still responsible for their deaths. Adolf Eichmann, the deportation expert, arranged the complicated logistics of moving large numbers of Jews from across Europe to extermination centers. Most famously, Hannah Arendt held him up as an example of a “desk murderer,” those individual bureaucrats who facilitated the Holocaust without ever directly confronting it. She even coined the term “banality of evil” to describe what she saw as faceless officials performing mundane (but vital) tasks without the fervor of other killers. Christopher Browning has noted that Arendt correctly identified this group of people, but was wrong in believing Eichmann to be one of them. Further examination found that “Eichmann exemplified willful evil: a man who consciously strove to maximize the harm he did to others.”4 Various “population experts” involved in planning the mass starvation of Slavic peoples provide another example. Thousands of people from secretaries to railway officials to architects knowingly acted as accessories to the murder of millions.

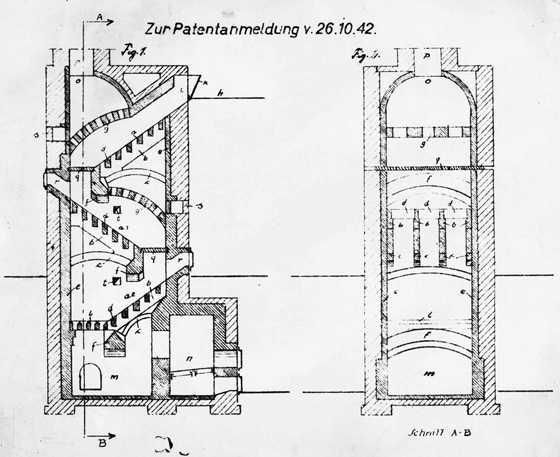

Another excellent example of this kind of “desk murderer,” both at the individual and organizational levels, was the company Topf and Sons. Topf and Sons was an established firm in Erfurt, Germany, which manufactured, among other things, crematoria for funeral homes and industrial incinerators beginning in 1914. The owners, Ludwig and Ernst Topf, and their crematorium engineer, Kurt Prüfer, were all party members. The company’s complicity in the Holocaust began with Prüfer designing and supplying the Buchenwald concentration camp with a mobile oven to burn bodies.5 Topf and Sons became the primary supplier of ovens to the Nazi camp system, with at least twenty-five installations completed.6 Soon, however, it became far more involved in the process of murder as the oven contractor to Auschwitz. More ominously, Topf began building ventilation systems into its designs, proving that designers knew their ovens were being used in an integrated gas chamber complex from which poison gas needed to be extracted. Company employees installed the ovens and ventilation systems on-site in Auschwitz and one of them testified after that the war that:

After returning from Auschwitz, I reported to the head of the company, Ludwig Topf, that I had successfully completed testing the fan and exhaust systems in the second crematorium of Auschwitz Camp [Crematoria II in Birkenau]. In passing, I reported to him that the SS men had gassed a group of inmates in the gas chamber and their corpses had been burned in the crematory ovens. L. Topf showed no reaction. (Moscow, March 11, 1948)7

The firm’s complicity peaked with an application for a patent imagining a four-story “continuous-operation corpse incineration oven for mass use.”8 Engineers at Topf and Sons recognized that corpse disposal slowed the extermination process and proposed solutions for their clients.

Source: Bundesarchiv Dahlwitz/Hoppegarten.

One area of perpetrator studies that historians have only recently begun to investigate is the role of women as participants in the Nazi genocidal project. Some fell into the category of the desk murderer or functionary. Nevertheless, we should not overlook the importance of the support these women lent their husbands, even simply knowing the nature of their work. Historian Claudia Koonz aptly summarized the value of the moral support offered by perpetrators’ wives, writing

Nazi wives did not offer a beacon of strength for a moral cause, but rather created a buffer zone from their husbands’ jobs. Far from wanting to share their husbands’ concerns, they actively cultivated their own ignorance and facilitated his escape.9

They provided a respite and a sanctuary enabling their husbands to continue their “difficult” work. Indeed, Franz Stangl’s wife admitted that “I believe that if I had ever confronted Paul with the alternatives: Treblinka—or me; he would . . . have chosen me.”10 She never put that question to the man who presided over the murder of between 870,000 and 925,000 human beings. Stangl’s interviewer also concluded “that he was profoundly dependent on her approval of him as a husband, a father, a provider, a professional success—and also as a man.”11

Other wives did want to participate in their husbands’ careers. Some benefited financially, as with Hans Frank’s wife in Poland. Other women, many single, were secretaries writing the Einsatzgruppen reports tallying Jews murdered in the East or serving in offices engaged daily in the persecution of Jews. Liselotte Meier, a secretary to the Nazi administrator in Lida, Belarus, accompanied her boss as he personally shot Jews. Despite strong evidence, Meier denied that she had also shot Jews, claiming not to remember.12 Other women, too, became killers like Meier. Liesel Willhaus, the wife of the Janowska camp commandant in Lwów, enjoyed shooting prisoners from her balcony. One survivor recalled her leaning on the balcony and shooting while SS men sat behind her on stools laughing as she apparently hit a prisoner in the neck, killing him.13 Another commandant’s wife “ordered her dog to attack the Jewish children who worked in the camp garden”; a survivor recalled the task of retrieving the victims’ limbs.14

In one final example, Erna Petri, wife of a German manager of an agricultural estate, murdered six Jewish children who had been seeking refuge there . . . after feeding them first.15 Petri told the court that “I wanted to prove myself to the men.”16 In this sense, Erna sought to be seen as an equal perpetrator with the men around her. Historian Wendy Lower presents these female perpetrators and others to refute the idea that “violence is not a feminine characteristic and that women are not capable of mass murder.” Moreover, she warns that “minimizing the violent behavior of women creates a false shield against a more direct confrontation with genocide and its disconcerting realities” while introducing an understudied class of perpetrators.17

What did the perpetrators do? The most obvious and well-covered actions were, of course, the murder of Jews and others. However, victimization took many forms, depending on individual, organization, and situation. Rampant theft of Jewish property occurred on both individual and group levels. For example, one German Army officer sent a train car of looted Jewish goods from Belarus to his home in Bavaria. One of his men observed that his comrades returning from a killing site had “acted as grave robbers. They had taken 10–15 rings, watches, valuable pieces of clothing.” They then mailed these items home to their families in Germany.18 As Jews moved into ghettos, Nazi officials systematically looted the bulk of their belongings left behind. In Lwów, one survivor in the Janowska camp recalled that Germans stole carpets, bedclothes, tablecloths and all manner of so-called “Jewish residue” and delivered them to be cleaned in the camp laundry where she worked.19 Throughout the East, Nazi administrators continually extracted exorbitant “ransoms” from the population in attempts to steal as much wealth from the Jewish communities as possible before their liquidation. As early as July 1941, German authorities in Bialystok demanded a ransom of 5kg of gold, 100kg of silver, and 2 million rubles in exchange for the release of 4,000 men taken prisoner by Police Battalion 316. Inhabitants, mainly women, desperately raised the money. One survivor recalled that “women are roaming the streets, weeping and begging us: Give us gold, silver, money, in order to save our husbands and sons.” The ransom was collected but, unfortunately, the 4,000 men had already been shot.20 Sometimes, theft was blatant and petty. In Kaunas on August 20, 1942, two Nazi civil administrators visited the Jewish council, stole 31,000 marks from the cashbox, and left.21

Sexual violence against Jewish women accompanied many other crimes during the Holocaust in Eastern Europe. This topic is only now beginning to receive the attention it deserves. Perpetrators across Eastern Europe raped and sexually victimized their victims as a matter of course in ghettos, camps, mass shooting sites, and elsewhere. These attacks ranged from violent assaults to coerced sex to sexualized violence. For example, when Himmler visited Sobibor in February and March 1943, three hundred attractive young Jewish women were specifically selected to be gassed as a demonstration.22 Not infrequently, Jewish women were raped at mass shooting sites prior to their deaths. Often, evidence of rape is not direct. A non-Jewish witness near the Ponary Forest wrote in his diary that a group of pretty young Jewish women was brought to the site. However, “the Germans, after bringing the Jewish women, removed the [Lithuanian collaborators] as far as the gate; nearly an hour elapsed from the arrival until the first shots were fired.”23 In Ukraine, the local Gestapo chief, Hummel, took two Jewish girls to his house on the day of the mass shooting, presumably killing them later.24 In both instances, the implication is clear that these women were raped before their death. In Romania, officers arranged “orgies” during the deportation of Jews.25 Sexual violence took place in the camps as well. Franz Stangl recalled that, on his first visit to Treblinka, camp personnel told him that then commandant Dr. Eberl “had naked Jewesses dance for them, on the tables.”26 In an act of sexualized violence, an SS man at the Janowska camp ordered two prisoners to have sex in public while the guards stood around and laughed. Both prisoners were shot when the SS grew bored of the spectacle.27 What is critical about such crimes beyond their sheer horror is that they were never part of the Nazi genocidal plan. Indeed, Nazi laws prohibited sexual contact between Jews and Germans. Sexual violence of all kind was completely voluntary, as was theft. This insight demonstrates the degree to which some perpetrators were most definitely not following orders, but making their own choices to victimize Jews to further their own interests.

What caused perpetrators to willingly participate in the Nazi genocidal project? Identifying perpetrator motivation is an incredibly complicated endeavor. We must look at two scales: the macro, societal level and the micro individual/group scale. Many scholars of different disciplines (historians, sociologists, anthropologists, social psychologists, political scientists) have addressed the question of what makes societies capable of mass atrocities. Earlier research suggested authoritarian societies and personalities were to blame. Later research added more complexity. Sociologist Harald Welzer argues convincingly that a change in the nature of social belonging sets the stage for atrocities. He writes:

Its alteration consists in the categorical redefinition of who belongs to one’s own moral universe and who does not – who belongs to one’s own group (‘us’) and who, as a member of a different group (“them”), is an “other,” a stranger, and ultimately a deadly enemy.28

This process of “othering” is not unique to the Holocaust, but is present in all genocides. Drawing on this, historian Thomas Kühne adds that in Germany after World War I,

the ethical code revolving around individual responsibility . . . was displaced by a moral system in which the only thing counting as “good” is that which appears good for one’s own community, whilst everything figures as “bad” which is detrimental to it.29

Thus, we can see that group norms at a societal level helped create the conditions that dehumanized the victims and placed them outside the usual protections of “civil” society. This also applies at the micro level. Finally, social psychologist Albert Bandura provides us with a helpful framework for summarizing how some societies create and tolerate perpetrators in their midst. He states that three conditions create the moral disengagement necessary for perpetrators (and their societies) to distance themselves from the immorality of their behavior:

1.Moral Justification: The perpetrator society views the victimization and killing of the targeted group as a necessary, indeed, vital service for the survival of the community.

2.Euphemistic Labeling of Evil Actions: Vague and innocuous speech is used to both mask the immoral actions being committed and relieve perpetrators from confronting their own moral misgivings.

3.Exonerating Comparisons: Societies and perpetrators justify the necessity of criminal actions by the great threat (often imagined) posed by the “enemy.” A utilitarian calculus then justifies immoral behavior in contrast with the much greater danger posed by the victim group.30

Taken together, these frameworks help us understand how German society (as well as some Eastern European societies and perpetrators) justified their actions against Jews and others on a state or national level. While it may seem odd, it is critical to recognize that no ideologically motivated perpetrator of genocide believes they are doing something wrong; on the contrary, genocidal ideologies always promise to improve society or save it from existential threats, even if the methods used cause moral discomfort.

At the individual or small group level, a diverse set of goals, beliefs, and environmental factors influence perpetrators to commit murder. These can be divided into dispositional (internal motivations and beliefs) and situational (external factors).31 Earlier debates considered whether ideological or circumstantial factors drove participation in killing but now, historical consensus recognizes that both influence each other. Therefore, while an individual may be more or less moved by one factor or another, neither is sufficient alone to explain perpetrator behavior.

Thus, some perpetrators were definitely radical antisemites who saw the murder of Jews as completely acceptable. Eichmann, the so-called banal bureaucrat, was secretly recorded in hiding, reminiscing about telling his staff at the end of the war that “I will gladly jump into my grave in the knowledge that five million enemies of the Reich have already died like animals.” In Theresienstadt, he told the Jewish Council that “Jewish death lists are my favorite reading matter before I go to sleep.”32 A Wehrmacht soldier described his commander as a “Jew hater;” this commander supervised the murder of 8,000–10,000 Jews in the town of Slonim in what is now Belarus.33 An Einsatzgruppen commander in Ukraine led by example at one killing; he murdered an infant and mother saying “you have to die for us to live.”34 These kinds of behavior and language represent the powerful antisemitism embraced by some of the killers. For others, particularly collaborators, antisemitism also combined with anti-Bolshevism as powerful motivation.

For others, antisemitic prejudices may have been present, but did not form the primary motivation. In its own perverse way, the Holocaust provided previously unavailable career opportunities. The Topf example is a good one, but career prospects were also important for the killers. Many ambitious SS officers saw service in the Einsatzgruppen as a path to more rapid advancement. Conversely, those Nazi officials who had failed or disgraced themselves in the Reich often flocked to the East attempting to revive dead careers. One Nazi press officer noted that many of the civil administrators in the East (responsible for ghettos, Jewish policy, etc.) were:

The idle and worthless type of . . . bureaucrat . . . the eternally hungry “Organizer” with a swarm of like- minded Eastern hyenas, his whole multitudinous clique, recognizable by the two big “Ws”—women and wine . . . 35

We have already seen that those who began in the T-4 euthanasia program found further employment in the extermination centers of the East.

Perhaps the most mundane and yet most thoroughly disturbing motivation for killing was simple peer pressure. In July 1942, the commander of Reserve Police Battalion 101 informed his men that they would be murdering Jews. He then gave them the opportunity to refuse. Only around thirteen chose this moment to step out—without consequence.36 The vast majority proceeded into the woods where they murdered almost 2,000 Jewish men, women, and children. Yet, these were not die-hard Nazis; they were middle-aged family men from one of the least Nazi-friendly areas in Germany.

Most simply could not resist the power of peer pressure and the expectations of the group. One scholar has called this “The Extraordinary Nature of the Collective.”37 It was common across the East for perpetrators to justify their participation on the grounds that they did not want to appear weak in front of their comrades or did not want their comrades to think they were avoiding “work” and passing it along to them. This reasoning also explains why most of those who refused used their own weakness as the excuse (at least publicly). They could then remain a part of the group; had they expressed their opposition in moral terms, they would be accusing their comrades of evil and would likely have been shut out of the only community available. One scholar has hypothesized that the very act of killing or transgressing standard morality created its own form of comradeship which “lived off collective breaches of the norm.”38 None of the preceding motivations for participation provides the only answer, but rather, they represent some ingredients present in varying amounts in a dangerous cocktail of spiraling violence.

We must close our brief overview of perpetrators by examining how they rationalized and coped with their own behavior. Why? Because the overwhelming majority of perpetrators in the Holocaust, including the killers themselves, were not insane and were not sociopaths. While initial studies had hoped to find that Holocaust perpetrators were psychologically abnormal, the truth is that most of them were quite healthy. This explains why so many experienced trauma as a result of their actions. Though perhaps hard to believe, some of the most dedicated, antisemitic murderers (such as Himmler) were disturbed by the experience. An SS officer in an Einsatzgruppen “suffered a nervous breakdown, because he couldn’t stand the killing any more, particularly his own part in the shootings, and he requested a transfer back home.”39 His request was granted. Many other leaders and also low-level perpetrators experienced similar trauma, what one might call today post-traumatic stress, yet continued to kill or to participate. Already in 1939, a low-level Einsatzgruppen member from the Polish campaign reported being “depressed” about whether he would be able to leave behind his “criminal habits” that he had picked up.40 By November 1941, Himmler had established mental hospitals, including one near Berlin, “where SS men are cared for who have broken down while executing women and children.” A designer of the gas vans testified that one reason for their construction was that “the firing squads could not cope with the psychological and moral stress of the mass shootings indefinitely.”41 These perpetrators and others relied on a variety of techniques in order to rationalize and assuage their own discomfort.

The theory of cognitive dissonance neatly explains some of this trauma and one method of alleviating it, even among deeply committed Nazis. The theory says that when our actions and our belief systems are not in alignment, we experience mental and emotional stress and must change one or the other to bring our psyches back into balance. For many, it was far easier to change beliefs to justify behavior than to alter or end their participation in murder. Reserve Police Battalion 101 provides an extreme example of this rationalization, where a policeman testified that he intentionally shot only children after the mothers were killed. He explained this saying, “It was supposed to be, so to speak, soothing to my conscience to release children unable to live without their mothers.”42

Other perpetrators sought to avoid the repercussions of their behavior by compartmentalizing or separating their murderous behavior from the rest of their lives. One scholar called this “doubling,” where perpetrators attempted to live two separate lives. Franz Stangl tried this approach. In her interview, reporter Sereny attempted to understand why he dressed up in a formal uniform to meet arriving trains at the ramp. “I tried once more,” she wrote. She asked him, “but to attend the unloading of these people who were about to die, in white riding clothes . . . ?” Stangl replied simply, “It was hot.”43 Stangl’s reply indicates his complete detachment from the event and that he could not or did not wish to explain why he would treat arrivals as such important events. Stangl claimed that “the only way I could live was by compartmentalizing my thinking. By doing this I could apply it to my own situation.”44 Stangl was not alone in this approach.

Language, as mentioned above, also played an important role in the “sanitizing” of crimes. Words like “Final Solution,” “Cleansing Actions,” “special measures/special handling (Sonderbehandlung),” “resettlement to the East,” among others provided perpetrators with a vocabulary allowing them to avoid facing their own actions. Stangl referred to victims as “cargo.” Einsatzgruppen and army units involved in killing often reported their victims as either partisans, which gave the appearance of legitimate military targets or with a variety of euphemisms such as “partisan helper,” “suspect civilian,” “stranger to village,” “wanderers,” and “civilians without identification.”45 Such linguistic camouflage attempted to create mental/emotional distance from troubling activities.

To cope with their actions and the trauma they created, some perpetrators painted themselves as the victims, not the Jews. They stressed the difficult nature of their duties that they carried out in the service of others. In this characterization, Germans steeled their own emotions in order to sacrifice for the greater good of cleansing Europe of the threat posed by Jews and others. A killing unit member told his men forcefully, “‘Good god! Damn it! A generation has to go through this for our children to have some peace.”46 Himmler himself proclaimed it was a “holy duty” for commanders to ensure that men who carried out the “burdensome duty” of killing never “suffer damage to the spirit.”47 The implication again is that the murder of the Jews was a deep sacrifice in which killers were victims.

Perhaps the final and most mundane solution for many was alcohol. Just as it had been in the euthanasia killing centers, alcohol and excessive drinking played a vital role in deadening the senses of killers and helping them fulfill their tasks. One scholar has concluded that “SS and police forces operating in the occupied territories abused alcohol on a tremendous scale.”48 As an EK leader, remarked to an Army officer, “We have to carry out this unhappy task, shooting all the way to the Urals. As you can imagine, it’s not pretty and one can bear it only with alcohol.”49 If the abuse of alcohol at shooting sites helped soothe the shooters’ consciences, it often resulted in poor performance leaving victims wounded but not dead. In the camps as well, alcohol figured prominently as a way to escape the tedium and also the trauma of living in a factory of death. Alcohol, despite Himmler’s wishes that it not be used, not only perhaps temporarily assuaged mental trauma, but it also caused perpetrators to become even more violent. At the Janowska camp in Lwów, a drunken SS-man fired wildly into prisoners waiting for their meal, killing fifteen Jews.50 Similar behavior and levels of drunkenness could be found at all the extermination centers in the East as well.

Perpetrator behavior, motivations, and coping mechanisms varied widely in time and space and this brief introduction certainly cannot be all-inclusive. However, the vast majority of perpetrators, whether direct or indirect, were not insane, sociopathic, or even particularly abnormal psychologically. They were, in most ways, ordinary individuals. Certainly, some were sadists drawn to violence, but most were not. This is and should be an uncomfortable truth highlighted by the quite different motivations and modes of participation sketched out above. As Christopher Browning closes his path-breaking book on the “ordinary men” of Reserve Police Battalion 101 “if [these] men . . . could become killers under such circumstances, what group of men cannot?”51

Local Collaborators in the Holocaust in Eastern Europe

For me, the situation was even more tragic because the orgy of murders was not only the deed of the Germans, and their Ukrainian and Latvian helpers. It was clear that our dear policemen would take part in the slaughter (one knows that they are like animals) but it turned out that normal Poles, accidental volunteers, took part as well.

Polish witness, STANISŁAW ŻEMIŃSKI, Łuków, Poland52

Local collaboration with Nazi occupiers in Eastern Europe is, perhaps, one of the most contentious histories for the modern populations of these countries. For a relatively small group of local non-Jews, then and now, this collusion with the enemy against the Jews was as tragic as it was to Żemiński (later murdered at Majdanek). His words are all the more damning as Poland is reluctant to recognize collaboration during the Holocaust. In this case, one author astutely notes that Poland is very proud not to have had a collaborationist government like Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, and the German puppet states. However, he explains that this phenomenon was “not because a sufficiently prominent person could not be persuaded to cooperate, but because the Germans had no interest in granting the Poles authority.”53 Poland is not at all alone in this regard, however. Starting almost immediately after the war, even as the Soviets tried and executed collaborators, the official history largely buried the issue of local collaboration. The approved “dominant view” was that “the entire ‘Soviet population’ stood up to face the Nazi invader.”54 To recognize otherwise would be admitting that nationalities and ethnicities had rejected the Soviet system so strongly that they sided with the Nazis. While exact numbers are difficult to determine, they are significant. By 1942, 8,000 Lithuanians served in mobile police battalions, ten of which directly participated in the murder of Jews.55 In the Baltic States, Belarus, and Ukraine, over 75,000 locals had volunteered to become “policemen” serving the Nazis by July 1942.56 In Ukraine, “the ratio of Germans to local collaborators in many departments and police organizations ran from one to five in 1941, to 1 to 20 or more by 1943. The SS there consisted of 15,000 Germans and 238,000 native police at the end of 1942, reflecting a ratio of nearly 1 to 16, a rate that rose to 1:25 or even 1:50 in some eastern regions by 1944.”57 Another scholar estimated that at least one million Soviet citizens collaborated with the Nazis.58 These numbers do not begin to include countless individual collaborators of all kinds.

Ironically, Jewish survivors usually hold their non-Jewish neighbors in higher contempt than the Nazis. Lithuanian survivor, Leib Garfunkel, wrote that “One of the factors that so exacerbated the suffering and pain of the Jewish population in Lithuania, and intensified their tragic fate, was the inhuman attitude toward the Jews on the part of many of their Lithuanian co-nationals, on all social levels.”59 For many Jews, the Nazis were like a natural disaster. They murdered Jews; that was their nature. But when non-Jewish neighbors joined in, the personal betrayal cut far deeper. This pain was felt not least because local collaboration was terribly important to the success of the Nazi genocidal project. One can argue that “without the active support of mayors, city councils, housing offices, and a plethora of local administrators, the identification, expropriation, and ghettoization of the Jewish population especially in rural areas would have exceeded the limited logistic capabilities of German occupation agencies.”60

While a minority of non-Jews actively assisted the Nazis and an even smaller minority participated in killing, the majority of non-Jews in the East were passive observers at best or approving beneficiaries. For this reason, no discussion of the Holocaust in Eastern Europe would be complete without an examination of local complicity. These collaborators operated under different conditions and had their own objectives set deeply in the local context. While I will use the term “collaborator” in this section, many of these individuals’ actions made them perpetrators as well, in that they actively participated in killing Jews.

First, not all regions of Eastern Europe collaborated with the same frequency or zeal as others. Generally, areas which had strong and enduring nationalist movements exhibited more intense collaboration. This is why the experience of Soviet occupation is so important in understanding the Holocaust. It neither solely explains collaboration nor solely caused it, but it did create fear, anger, and hatred in nationalist circles, many of which were already antisemitic. Garfunkel himself noted that Lithuanian antagonism toward Jews was “a side effect of the miserable downward slide in relations between the Lithuanians and the Jews, especially during the first year of Soviet rule and the annexation of Lithuania to the Soviet Union.”61 Such conditions made collaboration more likely with the Nazis who dangled vague prospects of national independence before these groups. By contrast, in areas like Belarus, which lacked a strong history of nationalist sentiment due to its multinational population and relatively short history, collaboration was not as widespread, though certainly not absent.

What did collaboration look like? Collaborators assisted the Nazis in a variety of ways, from providing information to committing murder themselves. But they also distinguished themselves from German perpetrators by acting out of sheer self-interest, often economic in nature. First and foremost, individuals willing to cooperate with Nazi occupiers could provide important information that was often deadly to Jews. One scholar has noted that in Ukraine “without local knowledge it would have been difficult for the Germans even to identify the Jews.”62 One informant in Kharkov told authorities “I am hereby informing you . . . that the Jewess Raissa Nikolayevna Yakubovich is registered in the house registry as a Jew. She now refuses to show her passport and claims to have lost it. I insist that Raissa Yakubovich is a Jew . . .”63 It is not difficult to imagine Raissa’s fate. In the tiny village of Krupki in Belarus, it was the Belarussian mayor who stood read out the names of his Jewish citizens to ensure that all were present for the Einsatzgruppen to murder.64

Information gathering took a more sinister form when collaborators actively sought out Jews in hiding, like Raissa, and turned them over to the authorities. This often surpassed simple informing. Many collaborators escalated victimization into blackmail by uncovering Jews in hiding and extorting money under threat of betrayal. In Lwów, a survivor observed that “blackmailers learned of . . . hiding places and demanded large sums of money for keeping quiet, almost on a monthly basis.” He described the dangers faced by Jews attempting to “pass” or hide in the local population, writing “individual blackmailers, crooks, and even children wandered the streets and had reached such a degree of expertise that they could identify at a glance a Jew in disguise.”65 This kind of collaboration could be quite lucrative.

Hunting Jews and turning them into authorities represented a more extreme mode of informing. Both individuals and organizations engaged in this behavior. Jan Grabowski, a Polish historian, has quite bravely detailed the actions of the so-called Blue Police in Poland. This organization was formed from pre-war Polish policemen and augmented with new recruits, including those who had not been qualified to serve under the Polish state.66 By 1943, there were around 16,000 Polish policemen working with German authorities.67 While a good number of these police were members of the resistance, many others actively collaborated to the extent that the underground kept lists of them. German occupiers needed these police to fulfill “normal” police functions so that the Nazis could carry out their racial policy; however, the Blue Police often took part in anti-Jewish actions as well. This often included uncovering Jews in hiding. One former officer testified, for example, that “in the fall of 1942 . . . we went to the village of Żdżary where we caught four Jews (among them one Jewess), who were hiding in the house of one Szkotak. The Jews were later brought to Radgoszcz, and shot by the Germans.”68 Grabowski emphasizes that “the deadly efficiency of the ‘blue’ police in the process of exterminating the Jews was linked, on the one hand, to their excellent knowledge of the area and, on the other, to the dense network of available informers.”69 Jew hunting was a pastime not limited, of course, to Poland. Throughout the occupied East, individuals and organizations assisted the Nazis in uncovering Jews in hiding either in the hopes of financial gain or to curry favor.

Local populations invariably sought to benefit financially from the plight of their neighbors. This behavior uniformly transcended national boundaries. Often, participants belonged to no official local or German organization, but were simply opportunistic civilians. Non-Jews from the Baltic to the Crimea routinely stole from Jews under cover of the Holocaust. In its most passive form, this kind of theft occurred as Jews were removed from their homes and killed. Sara Gleich, a survivor from Mariupol’, Ukraine wrote in her diary that, when she and her family were rounded up, “the neighbors waited like vultures for us to leave the apartment . . . They all rushed into the apartment. Mama, Papa, and Fanya with her children immediately kept going, they could not bear to watch it. The neighbors quarreled over things before my eyes, snatching things out of each other’s hands and dragging off pillows, pots and pans, and quilts.”70 Ukrainian authorities in the town imitated German authorities, demanding a ransom of two kilograms of pepper, 2,500 tins of black shoe polish, and seventy kilograms of sugar from the Jewish Council.71 Two days later, between 8,000 and 16,000 Jews from Mariupol’ had been murdered by Einsatzgruppe D.72 In Poland, a local peasant was ordered to bury murdered Jews. Afterward, the Nazis gave him a dress, shoes, and a scarf as compensation but he complained, “only afterwards did I [find] out that there was a bullet hole in the back of the dress.”73 In Łodz´, a Jewish school boy remembered that local Poles would frequently point out wealthy Jews to Germans in return for a portion of the loot.74

Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

The most damning form of collaboration, however, resulted directly in the murder of Jews. This usually fell into two categories: at mass killing sites and at extermination centers. During the “Holocaust by Bullets,” German killers often sought precisely this kind of assistance to alleviate the stress of killing. By the end of 1941, local auxiliaries did much of the shooting while German authorities supervised and directed them. These auxiliary units, called Schutzmannschaften (or Schuma battalions), were made up of young volunteers. The 13th Belarusian Battalion is one example. This group of young men represented some of the 130,000 Belarusians who collaborated with the Nazis.75 Formed in 1943 (much later than similar units elsewhere) the 13th guarded POW and concentration camps and participated in ghetto clearing operations in at least three towns in Belarus. The 13th Battalion also participated in Operation Cottbus, a “large antipartisan action” in June 1943. While purportedly directed against partisans, this operation intentionally killed far more civilians (and Jews) than actual enemy combatants. The results tell the tale: around 10,000 killed—6,087 “fell in battle,” 3,709 “executed,” 599 captured (who likely were murdered shortly thereafter). German losses? 89 killed. Non-German (collaborator) losses? 40 killed. Enemy weapons captured? Around 900 for 10,000 enemies.76 What is borne out of this and similar operations is that Jews and civilians were murdered when (most often) partisans could not be found or killed. If this operation is suggestive, others were not.

The commander of Einsatzgruppe A reported in October 1941 that “in all anti-Jewish steps, the Lithuanians take a stand alongside us, willingly and unreservedly.”77 Certainly, some embellishment adorns these reports. However, Lithuanian Schutzmannschaften were deployed across the East to directly participate in the murder of Jews. During the December 1941 massacre of 5,000 Jews in Nowogrodek, Belarus, a German sergeant observed that the actual shooting was done by a Lithuanian auxiliary unit.78 In March 1942, an Estonian Police Battalion murdered the remnants of the ghetto and, in February 1943, a Lithuanian Battalion helped murder another 5,500 Jews from Nowogrodek.79 Lithuanian Schutzmannschaften also killed Jews during large actions in Słonim and many other towns and villages throughout north and central Eastern Europe. Ukrainian auxiliaries were equally active. 1,200 of the roughly 1,500 shooters at the Babi Yar massacre were Ukrainian police.80 By July 1942, 75,000 Schutzmannschaften were assisting the Nazis.81

Beyond supporting Nazi mass shooting operations, collaborators also served as guards at extermination centers, where they formed the overwhelming majority of armed personnel preventing Jewish escapes or uprisings. By the end of 1941, the SS began searching through the masses of Soviet POWs for volunteers to assist them in controlling the East, particularly in anti-Jewish policy. Only non-Russian ethnicities (ethnic Germans, Ukrainians, Lithuanians, Belarussians, etc.) could volunteer; the Germans did not trust “bolshevized” ethnic Russians. By July 1941, SS officer Hermann Höfle had established a camp to receive these potential collaborators from the Red Army at a place called Trawniki, near Lublin.82 There, the SS trained them to serve as camp guards and executioners. These “Trawniki men” were often referred to by both prisoners and Germans as “Askaris,” after local East African contingents that had supported German colonial forces in the early 1900s. The goal of the education at Trawniki was quite clear, as remembered by one former member: “When we completed training . . . the Germans ordered each of us to shoot a Jew. They apparently did this in order to be better able to rely on our loyalty to them.”83 Approximately 5,000 men served as Trawniki men, all of them directly engaged in the murder of Jews; they operated as guard forces in all the extermination centers, they participated in mass executions, and they assisted with ghetto liquidations (including the Warsaw ghetto.) Other auxiliaries, particularly Ukrainians and Lithuanians, also served.

Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Often, motivations differed for those in collaborationist organizations vs. individuals. Underlying much collaboration, however, was a foundation of antisemitism that saw Jews as inferior, a threat, or as complicit in Soviet oppression. Nazi occupation did not create these conditions, but certainly exacerbated them. Many were at best indifferent if not happy to see their own “Jewish question” resolved. As the famous Polish resistance fighter, Jan Karski, noted, “dislike of the Jews created a narrow bridge on which the [German] occupier and a significant part of the Polish society could meet.”84 Even a Polish underground newspaper wrote that “ . . . every true Pole knows that in a reborn Poland there will be room neither for a German nor for a Jew.”85 Collaborators in other regions expressed similar sentiments.

To many Eastern Europeans in small towns, the price of one’s soul was relatively cheap. Financial rewards could be great and immediate, as we have observed above; it should be pointed out that the value of a coat, household goods, and so on, was much higher for the relatively poorer Eastern Europeans than in the West. In the town of Iodi in Belarus, for example, while Germans were murdering the Jews, “the local population looted all the [Jewish] homes.”86 Extortion all too often accompanied murder as well. In Poland, a man named Kozik hid three Jews, who paid him for this service. When they ran out of money, he killed them with an axe.87 These behaviors were not uncommon, as Jews in hiding were helpless against such attacks.

For those who joined collaborationist organizations (Schuma battalions, Trawniki, Iron Guard, Arrow Cross, etc.), financial gain was also a motivation. Members received higher pay, uniforms, food allowances, additional privileges, protection from their own potential victimization by the Nazis, and the opportunity to do their own robbing of Jews. Collaborators slightly higher in the chain of command individuals also received substantial compensation. A Ukrainian working for the German intelligence section in Krakow would receive a “beautiful, two-room, fully furnished apartment, including a telephone and radio.”88 This would have been the height of luxury. In uncertain times, financial stability and even advancement were powerful motivators.

For other collaborators, particularly those who joined organizations, political aspirations were an important motivation. Many were nationalists who had seen their countries occupied and victimized by the Soviets. They hoped, naively, that cooperation with the Nazi state would lead to independence. In almost all occupied areas however, the Nazis swiftly dispersed or marginalized nationalist groups. Virulent nationalist leaders often found themselves in forced exile in Germany or in prison. Yet, for many of the rank and file, simply the feeling of combating the Soviets alongside the Nazis left a glimmer of hope for national rebirth, even if it were an entirely unrealistic one. Organizations such as the Latvian Legion, a unit of the Waffen-SS, were extreme examples of this kind of thinking, often made up of men who had previously served in the Schutzmannschaften and who had murdered Jews.

The vast majority of Nazi collaborators in the Holocaust were Eastern European, either as individuals or as organizations. Without their help, the murder of the Jews there would have been much more difficult. From providing information to seeking individual rewards to refusing to shelter Jews, many locals intentionally or unintentionally made the task of the Nazis easier. Like perpetrators (a category which must extend to many collaborators as well), however, they did so for a variety of reasons stemming from the mundane to the ideological.

“Brave People”: Helping and Rescue in Eastern Europe

“Memorable Sunday,” survivor EDMUND KESSLER, 1942–44, Lwów89

Edmund Kessler survived hidden in a secret cellar by a Pole and nicely sums up one of the fundamental paradoxes of the Holocaust: most non-Jews did not help or rescue a single Jew, yet practically every Jew who survived was helped or rescued at some point by a non-Jew. The choice to rescue or even aid Jews carried great risk for non-Jews, particularly in Eastern Europe where they were far more likely to be executed along with their families, unlike in the West. The instinct of most human beings in a situation such as Nazi occupation is to avoid scrutiny and protect those closest to them. This natural tendency made each rescuer a rather unique individual and each rescue a unique event, conducted according to the circumstances on the ground. Rescuers formed a tiny minority of those encountering Jews during the Holocaust, but they critically show us that not everyone lost their humanity or stood idly by as their neighbors and the Nazis murdered Jews. To the contrary, the bravery of rescuers demonstrates that it was possible to save Jews and casts a harsh light on those who chose to benefit from the occupation instead.

Before exploring how and why some individuals risked their lives to save Jews, we must define what “rescue” and “helping” mean in the context of the Holocaust. Yad Vashem of the Israeli Holocaust Museum officially recognizes some rescuers as “Righteous Gentiles” or “Righteous Among the Nations” using a relatively strict definition. First, they recognize four main forms of rescue: “hiding Jews in the rescuers’ home or on their property, providing false papers and false identities, smuggling and assisting Jews to escape, and the rescue of children.”90 Moreover, Yad Vashem withholds the designation if rescuers saved Jews for financial gain, religious conversion, for adoption, or as a result of other resistance activities. Lastly, in order to qualify, rescuers must have actively risked their lives.91 These conditions, not always unreasonable, do, however, limit the number of individuals who become “Righteous.” Not infrequently, monetary exchanges lead to a disqualification from consideration for the award of Righteous.92 A well-known scholar has critiqued the Yad Vashem standards, arguing they “also [provide] a misleading model of what is required in order to assist those in need, even those in dire need.”93

The numbers and national breakdowns for Eastern European awardees can be found in Table 11. The Righteous in Western Europe are overrepresented likely due to more documentation, the lack of Soviet interference, and general societal acceptance of rescue behavior, something often lacking in the East (France, for example, has nearly 4,000 names.)

TABLE 11Righteous Gentiles by country (Eastern Europe).

|

Country |

Righteous |

|

Poland |

6620 |

|

Ukraine |

2544 |

|

889 | |

|

Hungary |

837 |

|

Belarus |

618 |

|

Russia |

197 |

|

Latvia |

135 |

|

Moldova |

79 |

|

Romania |

60 |

|

Bulgaria |

20 |

|

Estonia |

3 |

|

Total |

12,002 |

Source: “Names and Numbers of Righteous among the Nations—Per Country & Ethnic Origin, as of January 1, 2016,” Yad Vashem, http://www.yadvashem.org/righteous/statistics.

Certainly, the numbers are even higher if we include without moral judgment those who saved Jews for less than ideal reasons. We must also recognize that many rescuers remain unknown due to their own wishes or having simply been lost in time. Thus, we may consider a more inclusive definition that counts those who actively prevented the murder of Jews. To this category, we should add that of “helper.” Very few rescuers acted in isolation. In fact, research shows that successful rescue depended upon a network of people working together, either knowingly or unknowingly. For example, one person may have helped a Jew escape the ghetto, another provided food and housing for a night or two, another supplied false documentation and took the Jew to a hiding place while the rescuers there protected him/her. In addition, we should consider those who knew about such behavior and out of sympathy did not report it.

What did rescue look like? As with everything in the Holocaust, rescue was inevitably a local affair. The options, methods, and likelihood of success often depended on local conditions, time period, and environment—sometimes in surprising ways. It could be more difficult to hide one Jew in a small village than to hide twenty in a large city. Helping behavior carried perhaps the lowest level of risk, but was important nonetheless. Many survivors recall a moment’s temporary hiding or a gift of food and clothing as critical to their survival. In Ukraine, Leah Bodkier fled a killing action and was fed and clothed by local Ukrainian peasants before she found a permanent hiding place.94 Two girls fleeing a mass shooting in Belarus recalled being taken in by a Christian woman who told them, “You do not have to tell me where you are coming from. I know. God has brought you to the right house.” She fed them, treated their wounds, and hid them until the next morning, when the girls left of their own volition, fearing for the safety of their rescuer.95 Edmund Seidel escaped a death train bound for Bełżec but found himself naked in the snow. He survived only thanks to a local woman who gave him clothing.96 A German soldier in Słonim hid a young Jewish boy in his headquarters during an Aktion.97 He later brought the boy and his family food in the ghetto. His actions were not secret and were at least accepted by his comrades.

Even during frequently vicious and chaotic pogroms, individuals tried to intervene to save Jews. In Lwów, several individual German soldiers protested, one shouting that “we are not Bolsheviks, after all.”98 Of course, being German protected them from the reactions of the crowd. Others were not as lucky. During the Iasi Pogrom, a former professor was shot trying to save a Jew along with a priest attempting to do the same.99

The most dangerous but most vital forms of rescue were escape and permanent hiding. These actions were riskiest, but also most likely to ensure survival. Many rescuers saved Jews by enabling their escape from the Nazis, either from ghettos and camps or from Nazi territory itself. In the latter category fall, for example, two diplomats in Lithuania: the Japanese consul, Chiune Sugihara and the Dutch consul, Jan Zwartendijk. These diplomats saved Jews in 1940, before Lithuania came under Nazi control but at a crucial point when Jews were attempting to flee Soviet persecution and fleeing Nazi occupation. Together, they helped around 8,000 Jews escape Europe.100 Most famously, Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg, assisted by other diplomats, established an “international ghetto” in Budapest, Hungary, and helped issue documents protecting around 50,000 Jews from deportation. Individuals also smuggled Jews across borders and out of ghettos and camps. A most extraordinary example of this is German Sergeant Anton Schmid. He worked in a rear area unit in Vilnius, Lithuania that used Jewish slave labor from the ghetto. He filled a cargo truck weekly with Jews from the ghetto which he drove across the border into Belarus where he released them in safer areas.101 Oskar Schindler is a more famous example, managing to transport several thousand Jews to his own factory in Czechoslovakia, away from Nazi killing. In the Romanian town of Chernivtsi, the mayor and other citizens “stood up for the Jews and managed to retain 20,000 individuals [from deportation] by identifying them as being ‘important for the war effort.’”102

The most difficult form of rescue was hiding Jews. Rescuers contended not only with the difficulty of creating hiding places, but they also had to devise clever ways to supply their Jews with food without raising the suspicions of neighbors who might well turn them in for a reward. Frequent Nazi (and local collaborator) searches for Jews also made hiding them an incredibly stressful and perilous endeavor. Hiding took many forms. In Vilnius, a Catholic priest and a nun hid eleven of their Jewish archive workers in the monastery.103 The director of the zoo in Warsaw, Jan Zabinski, used his empty complex to hide Jews and personally hid twelve Jews in his own house, where his wife and son helped.104 Pavel Gerasimchik, a poor Ukrainian peasant and father of three, volunteered to hide a Jewish family he had known before the war. It was a difficult decision, but he and his family worked to provide the additional food necessary and successfully hid the family until the end of the war. Gerasimchik even returned a gold watch the Jews had given him.105

Rescuers providing hiding places also placed their families in danger, for all would be shot if they were caught. In Kharkov, a journalist, Alexandra Byelova, was caught hiding a Jewish girl and executed. The Nazis executed Lithuanian Joudka Vytautas along with two Jewish women she had hidden.106 A survivor recalled that, after the liquidation of the Lwów ghetto and subsequent search for hidden Jews, “the corpses of Poles who had been discovered giving shelter to Jews and the corpses of the Jews themselves could be seen all over the town, in the streets, in the squares and in all residential quarters.”107 One historical study identified at least 700 Poles executed for hiding Jews.108 Rescuers had more to fear than the Nazis. Local non-Jews often murdered their neighbors for hiding Jews, as was the case for Lithuanian carpenter Jonas Paulavicius. His family hid twelve Jews. His neighbors only discovered his actions at the end of the war. They called him “Father of Jews” and murdered him in 1952.109

Why did rescuers do what they did? What motivated them to take such incredible risks, often for strangers? These questions are central to understanding why individuals chose to behave humanely in the face of overwhelming danger and the Eastern European context in which they acted. Some rescuers, particularly clergy and religious personnel, were driven more by their Christian faith. These individuals often baptized Jewish children and gave them to Christian families or attempted to convert them. One survivor from Kaunas described the priest who hid her, saying, “I understood from what he said that he was interested in rescuing children younger than me, so he could teach them Christianity . . . He would issue birth certificates and arrange for children to be placed with farmers in the villages . . . He said to me once, after liberation, that his profit consisted of sixty or seventy children who had been baptized into Christianity and whose parents were no longer alive.”110 Even a devoutly religious Catholic antisemite in Warsaw illegally secured the safety of 300 Jewish children by placing them in Christian orphanages and convents.111

Of course, moral or positive reasons did not motivate all rescuers. Many hid Jews simply for the financial opportunities they represented. One survivor described her feelings toward her rescuer: “Why should I be grateful? . . . He loved money . . . He did it only for money, besides every week he kept raising the price . . . and threatened that if the war would drag on, he would not keep me.”112 She was lucky. Other “rescuers” of this kind often killed Jews when their money ran out. Other would-be rescuers murdered or denounced their charges if they feared they would be discovered. Rescuers motivated by personal greed were also more likely to sexually or physically abuse their protectees.

Yet, in her study of rescuers, scholar Nechama Tec found that only 16 percent of the rescuers were “motivated by financial gain.”113 In fact, many rescuers chose to help Jews out of their own moral understanding of right and wrong. Tec has done the most extensive research on these altruistic rescuers. Her path-breaking work gives us the best insight, so far, into what made some people choose the difficult path in helping Jews. She identified six common elements of their personalities and motivations:

1)Individuality or separateness, which means that they did not quite fit into their respective social environments

2)Independence or self-reliance to act in accordance with personal convictions, regardless of how these were viewed by others.

3)Broad commitments to stand up for the needy and an enduring history of performing charitable acts.

4)A tendency to perceive aid to Jews in a matter-of-fact, unassuming way, with consistent denials of heroic or extraordinary qualities of rescue.

5)Unpremeditated, unplanned start of rescue, that is, a rescue that was extended gradually or suddenly, even impulsively.

6)Universalistic perceptions about the Jews. Rather than seeing Jews in those they were about to protect, they saw them as people totally dependent on aid from others. Such perceptions come with an ability to disregard all attributes except those expressing extreme suffering and need.114

Tec’s rubric, derived from interviews with 309 survivors who described 565 rescuers, gives us perhaps our best understanding of what kinds of people became rescuers.115 Like perpetrators, one factor alone, such as personal beliefs or circumstance, cannot explain rescuer motivation and behavior. Rather, as we have seen, rescuers came from all walks of life and were influenced by both personal beliefs and situational factors. Not all rescuers had pure motives, and yet, in the end, many of them did rescue Jews. Others were guided by a moral compass, but acted only when they suddenly found themselves confronted with the opportunity to help. Anton Schmid best expressed the simple humanity and courage of most rescuers. He wrote his sister before his execution for smuggling Jews to safety: “my dearest Steffi and Gerta, it is a terrible blow for us, but please, please forgive me. I acted only as a human being and did not want to hurt anyone.”116

This examination of the complicated phenomenon of perpetrators, collaborators, and rescuers shows us several important characteristics about the human response to the Holocaust in Eastern Europe. In all three cases, we see that individuals involved were motivated not by one particular factor, be it ideology, personal gain, antisemitism, or situational and environmental factors. Rather, these men and women chose to behave as they did due to the complex interplay of all of these factors, with some being more influential at different times and places. Perhaps more importantly, we learn that most perpetrators were not insane and more ordinary than not. Likewise, rescuers show us that it was possible, even in the face of incredible danger and overwhelming difficulty to retain one’s humanity and help others in need. In both cases, the actors may well have more much in common with us than not.

Selected Readings

Grabowski, Jan. Hunt for the Jews: Betrayal and Murder in German-Occupied Poland. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2013.

Hilberg, Raul. Perpetrators, Victims, Bystanders: The Jewish Catastrophe, 1933–1945. New York: Aaron Asher Books, 1992.

Lower, Wendy. Hitler’s Furies: German Women in the Nazi Killing Fields. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013.

Sakowicz, Kazimierz, and Yitzhak Arad. Ponary Diary, 1941–1943: A Bystander’s Account of a Mass Murder. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005.

Tec, Nechama. When Light Pierced the Darkness: Christian Rescue of Jews in Nazi-Occupied Poland. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.