1

Schemas and Scripts: Cognitive Instruments and the Representation of Cultural Diversity in Children’s Literature

John Stephens

Cognitive poetics over the past couple of decades has suggested some powerful approaches to literature as a form of human cognition and communication with a specific potential for responding to social reality. The theory offers some vital insights into how readers construct mental representations in their minds, and it has the further possibility of forging connections between representations of social ideology and the various reader response theories that remained widespread in children’s literature criticism long after they seemed to have disappeared from general literary theory and practice. To explore a small example of how some basic structures of cognition function in literature, this chapter argues that processes whereby the cognitive instruments of schema and script are textually modified have played a central function in positive representations of cultural diversity, as such modifications are an expression within story worlds of wider transformations of social mentalities. The contexts for these processes have been the various stages of the rise (and decline) of multicultural ideologies over the past four decades since they began to be identifiable in the 1960s – in the USA, for example, the Civil Rights movement was followed by programs in the 1970s to reorganize primary and secondary education to benefit students from minorities. However, as Will Kymlicka has recently pointed out, local processes such as this are part of a much larger process involving the conversion of ‘historic relations of hierarchy or enmity into relations of democratic citizenship’ (2007: p. 88). He points to strategic reasons why groups and states developed some willingness to support or accept multicultural reform, including big issues such as ‘changes in the geopolitical security system of the Western democracies, and changes in the nature of the global economy’ (2007: p. 88). Kymlicka thus adduces the following sequence of movements:

(i) a revolution in ideas about human rights and human equality following World War II;

(ii) processes of decolonization between 1948 and 1966, and the concomitant contesting of assumptions about ethnic and racial hierarchies;

(iii) racial desegregation initiated by the American civil rights movement, and then local adaptations of civil rights liberalism in numerous other countries (e.g., where minorities had been assimilated, losing language and culture, rather than segregated);

(iv) the establishment of ‘rights-consciousness’ (an assumption of equality) as an element of modernity.

Although children’s literature around the world has thematized multiculturalism and cultural diversity in varied ways, the sequence referred to above has functioned as a basic ground for representing diversity in children’s literature, and in many places it still does so. On the whole, children’s literature has sought to intervene in culture to affirm multicultural models of human rights and human equality, and it has done this by striving to transform the schemas and scripts that were common in Western cultures up until the mid-twentieth century and are still quite pervasive today. To effect such a transformation, children’s texts have primarily attempted to transform the central components of schemas, and hence the story scripts into which they are drawn. As Lyn Calcutt et al. argue, ‘As clusters of ideas for thinking with, cognitive schemas can facilitate our understanding of how social categories are conceptualized’ (2009: p. 171), so changes made within a cluster allow others to be conceptualized in fresh and nonthreatening ways. Importantly, this process involves a whole range of everyday schemas as well as those directly involving cultural diversity.

The transformative potential of schemas and scripts

Schemas are knowledge structures, or patterns, which provide the framework for understanding.1 They shape our knowledge of all concepts, from the very small to the very large, from the material to the abstract. Thus schemas shape our knowledge of:

(i) objects (e.g., attributes or characteristic spatial and functional relationships – motion along a path, bounded interior, balance, and symmetry [Turner, 1996: p. 16]);

(ii) situations (personal relationships; gender roles; etc);

(iii) genres (fantasy; realism; adventure story; a narrative about friendship; etc);

(iv) cultural forms and ideologies.

Schemas do this because they are aspects of memory. As we read a verbal text, or look at a picture book, the data matches part of a schema in the memory and activates it. Generally, a schema consists of a network of constituent parts, and the stimulus evokes the network and its interrelations, especially what is normal and typical about that network. A schema is instantiated (a) by naming it; or (b) by citing a selection of constituent parts. Whereas a schema is a static element within our experiential repertoire, a script is a dynamic element, which expresses how a sequence of events or actions is expected to unfold.2 One does not need to be given every event in the causal chain that constitutes a script to understand it. Rather, one infers the complete script from a core element and identifies unexpressed causal links between events (see Schank and Abelson, 1977: p. 38). A simple script informs an incident portrayed in Michelle Cooper’s The Rage of Sheep (2007), in which the 15-year-old female narrator, Hester, is taking her dog for a walk and they encounter a cat. The dog chases cat script has basic components: Fred, the dog, approaches a shrub. A cat bursts from the shrub and runs away. Because a reader recognizes the script, it would be redundant to include intermediate steps such as: The cat saw the dog approaching. The cat was afraid of the dog. We understand the minimal sequence because we can draw on our store of stereotyped sequences of actions that form a crucial part of human beings’ knowledge about the world. Creative works involve a further level of connectivity between the pre-stored, dynamic knowledge representations bound up with everyday life and the stereotypic plot structures that readers use to anticipate the unfolding story logic of creative works (see Herman, 2004: pp. 89–91). Of course, the logic of a created story does not follow a stereotypic script, and the process of connecting apparently deviant or merely unexpected events may involve readers in unfamiliar insights and perceptions, or may even transform the script into another way of understanding the world.

Much of the transformative potential of schema and script is evident in the ways Cooper transforms the simple script:

‘Stop that,’ I told him as he strained towards a quivering shrub. ...

‘You’re a horrible, disobedient dog,’ I said, ‘and I really don’t know why I –’

The shrub exploded and a furry grey animal shot out and dashed down the footpath. Sodden leaves flew everywhere as Fred, legs skittering in all directions, hurled himself after it.

‘Fred!’ I shouted, trying to hang onto his worn leash and stay upright. ‘Stop!’

‘Woof!’ said Fred. He gave a giant lunge forward and snapped the leash in two. Free at last, he streaked along the road, jaws snapping, the grey thing barely a length in front of him.

(Cooper, 2007: pp. 88–89)

Stored in the memory, previous experiences form structured repertoires of expectations about current and emergent experiences. Although Hester is myopic and cannot identify what she sees here, the schema (static repertoire) allows readers to perceive that the running ‘furry grey animal’ is probably a cat, while the dynamic script repertoire further enables readers to anticipate how events will unfold (a) when a dog encounters an animal that flees, and (b) when the owner is unable to control the dog. In this example, readers not only recognize a sequenced set of particular objects involved in a particular event but also a sequence of objects that belong to categories (cat/dog/hostility) involved in an event (a chasing) that belongs to a more comprehensive category (a pursuit script). A reader’s process is not preordained, however, and as Raymond W. Gibbs argues, readers will decide both ‘what script is relevant and how it should be modified to fit the situation in hand’ (2003: p.33) – in other words, readers may understand the text creatively. When these skeletal elements of repertoire are elaborated as narrative fiction, a writer has various options beyond expressive representation of setting (‘a quivering shrub’, ‘sodden leaves’). Schema and script can be modified for comic purposes, as when in The Rage of Sheep Fred’s antics become a comic source of humiliation for Hester, although the further possibilities of a myopia schema are not developed at this point. The myopia schema functions rather as a recurring, characterizing motif, as Hester deals with the consequences of concealing her eye problem from parents and teachers. As such, however, it runs in parallel with other things that set Hester apart – especially her academic cleverness and her brown skin. Sustained mapping of a schema throughout a text is a key element in drawing out the significance from the story world, because once readers recognize and mentally instantiate the schema, the recurrence or addition of further components enables the schema to be modified for socially transformative purposes. This possibility is vital for representations of cultural diversity. I will further develop the argument below.

When readers recognize the beginning sequence of a script, they anticipate what is to come and derive satisfaction from how the text expands the script by completing or varying the expected pattern. Thus readers assume that Fred will not catch the cat and that Hester will face some kind of problem, but that is all the script imparts. When readers respond to the script and its further articulation, they are engaged in what Mark Turner (1996: p. 20) refers to as ‘narrative imagining’: readers predict what will happen and subsequently evaluate the wisdom or folly involved. Hester’s attempt ‘to hang onto [Fred’s] worn leash’ (my italics) does not just anticipate that the leash will break but also that Hester is victim of her own or her parents’ carelessness. Second, narrative imagining is a cognitive instrument for explaining how the story moves from a normal situation (girl walking dog) to a bizarre or humiliating situation (girl trying to entice dog back out of a sewerage overflow pipe).

Modifying the variable components of a schema

In principle, if children’s literature is to affect how the mind understands and structures the world, this will be most evident in picture books, which target audiences at a stage of mental development when schemas may not be fixed in memory in a particular form. To illustrate how this works in practice, I turn now to a simple example from a collection of stories published by Janet and Allan Ahlberg in 1987, at a time when children’s literature in England was most optimistic about cultural diversity. In this story, ‘The jackpot’, a giant has a problem with boys named Jack, all of whom want to play out the Jack and the Beanstalk story. The giant’s solution – to capture the Jacks and relocate them at a distance from his house – only serves to make them work together:

The Jacks formed a football team ... Now the giant is plagued with Jacks, twelve at a time (eleven plus a substitute). Often they arrive roped together like climbers. (Ahlberg & Ahlberg, 1987: unpaged)

At this point, the text has introduced the schema for a cooperative group or team. The word team itself evokes the schema. Now, the team schema has some constant components: it consists of a group linked in a common purpose, and its members have complementary skills and coordinate their efforts. The schema also has variable components: the concept covers different kinds of teams – here a football team and a climbing team – and the background of the members may be homogeneous or heterogeneous. The team drawn by Janet Ahlberg in the illustration that accompanies the text demonstrates variables of ethnicity, class, age, and dress preferences. The text-picture interaction here has gone considerably further than exploiting illustrations to represent a multicultural society as setting for a fractured fairytale about the otherness of giants (who are not depicted as other at all). The illustration shows a heterogeneous group represented as linked in a common, mutually supportive purpose. But the illustration also impacts on the language, so that ethnicity, class, and so on are represented as normal variables. Hence the cooperative, multicultural society has the potential to change the schemas used to make sense of the world.

Practices of representation and multicultural scepticism

The problem for children’s literature has been that models of human rights and human equality can be simplistic and may fail to engage with the actual politics of diversity. As far as I am aware, it has been uncommon for the literature to address the problematics of contemporary cultural diversity, and then almost only in the YA novel. Opponents of multiculturalism challenge at least two of the assumptions Kymlicka sees as positive schemas – erasure of ethnic and racial hierarchies, and rights-consciousness. It’s also probable that no two countries are diverse in precisely the same way. The so-called New World settler societies – Australia, Canada, USA, and so on – have at least three broad ethnic components with some distinct sub-groups. A map for the USA might thus look something like this:

Indigenous Americans (‘Amerindians’) |

|

European settlers (since the 16th century) |

|

‘cultural groups that by virtue of race, ethnicity, or religious background differ from the culturally dominant white Europeans’ |

African Americans

Asian Americans

Hispanic Americans

Jewish Americans |

(M.D. Kutzer, 1996. Writers of Multicultural Fiction for Young Adults, p. 2) |

|

A comparable map for Australia would look like this: |

|

Indigenous Australians |

|

European settlers (since the 18th century) |

|

Migrant groups (since the 19th century), but in children’s literature mostly imagined as mass migration after 1950 |

Refugees (political, economic)

European migrants

East and South-East Asian migrants

South Asian migrants

West Asian migrants |

On the other hand, a map for the United Kingdom is like this: |

|

‘Anglo-Saxons’ |

|

Celtic substate nationalist groups |

Scotland

Wales

Northern Ireland |

Migrant groups (characteristically, but not exclusively, from former colonies) |

Refugees (political, economic)

Caribbean

South Asia

African countries

Etc. |

Kymlicka’s proposed tripartite structure can be varied in many ways, but a European perspective would wish to include the rather different forms that emerged in various East European countries from the early 1990s and, alongside the masses of principally economic refugees entering Europe, might be seen as components in a global retreat from the multicultural ideologies of the previous two decades. The broad tripartite structures clearly indicate that responses to them in children’s literature will be different in different countries, but we need to ask whether in general the practices of representation are ultimately robust enough to respond to the current more sceptical climate. As Clare Bradford (2006: p. 117) remarks, children’s literature often produces a weak multiculturalism, and I would argue that this weakness derives not just from naïve optimism but also from weak uses of representational strategies. As has long been recognized, at the inception of multicultural children’s literature cultural flows tended to be in one direction, because perspective and focalization were usually located with a principal character from the dominant, or majority, culture. When that deficiency had been addressed by the late 1980s, stronger strategies were enabled, but those processes were not always sufficiently marked by fluidity and processes of dismantling and reformation to stand against the negative public socio-political rhetoric. Young people are still regularly offered versions of weak multiculturalism, as in the following example from Bobbie Kalman, What is Culture?, a schematic representation of types of clothing in an opening from a recent (2009) series (originated in Canada, but published multinationally in four English-speaking countries) (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Diagrammatic representation of ‘The Culture of Clothing’, from What Is Culture? by Bobbie Kalman

Images: 1. South Asian bride; 2. boy in traditional Korean costume; 3. children in ‘comfortable modern clothing’; 4. Indian children in traditional dress; 5. a Japanese family; 6. Indonesian Muslim boys.

The strategy in this particular volume, as in others in the series, is to stress that all over the world people have different ways of life (p. 5) but a common humanity. How this page is interpreted is determined by its opening statement: ‘Most children around the world wear modern clothes, like the clothes you wear’ (p. 14). First, the second-person addressee, ‘you’, locates perspective in an assumed majority culture; second, when the sentence is rephrased as the caption for the group photograph at image 3 it asserts a normative schema: ‘Most children wear comfortable modern clothing. Jeans and T-shirts are favourite everyday outfits.’ While this may be a consequence of globalized culture, the formulation ‘comfortable modern ... everyday’ effectively erases otherness, and is the grounding schema in terms of which we are to understand the other five images in this opening. The two images immediately above the group photograph (images 1 and 2) are literally marginal, placed on either side of the centrally positioned text, and state or imply a self-conscious dressing up.

This text informs readers that ‘Some children wear traditional clothes at special times, such as on holidays, at weddings, or during festivals’, and images 1 and 2 depict ‘a young South Asian woman’ dressed for her wedding and a boy ‘in a traditional Korean suit’. The three images on the right-hand page state or imply that they depict archaic practices: children dressed in ‘traditional Indian jackets’ for a party (4), a Japanese grandmother in a kimono, while ‘the rest of the family is dressed in modern clothes’ (5), and Indonesian Muslim boys, distinguished by their ‘long loose shirts’ and ‘caps on their heads’ (identified as a religious practice). The Japanese family photograph offers the most marked example, as the children are two generations away from traditional culture. In a culturally diverse society no action occurs in isolation, but will to some extent be dependent on actions performed in another part of the system, and what a practice signifies in one place will not necessarily offer the same signification elsewhere. In this example, the grounding schema – clothes that are ‘comfortable, modern, everyday’ – consigns all ‘other’ clothing styles to the cultural periphery.

Robust representations of cultural diversity

A more robust strategy for negotiating cultural difference between generations can be seen in Old Magic (1996 text, Allan Baillie; illustrations, Di Wu). This is as an important book because of its robustness, on the one hand, and because it was published in the year Australian social policy took a sharp turn to the right. Within five years Australia had passed from what Graham Huggan calls ‘multiculturalism fatigue’ to ‘unofficial dismantling’ of multiculturalism through the first decade of the twenty-first century (2007: p. 110). The ideology hammered out in the early 1970s as part of a vision of Australia as a vibrant, culturally diverse country had receded into the background of public discourse as the advocacy of diversity and glocalization that had informed children’s literature for twenty years was perforce largely replaced by a literature of resistance against regressive social policies and aggressive border protection.3

Old Magic represents a bricolage of cultures: it is the story of an Indonesian grandfather and grandson living in Australia, told by an Australian and illustrated in a Chinese style. The first opening instantiates three schemas. First, the child Omar is an extreme example of the modern global child assumed as the norm in Kalman’s ‘Culture of Clothing’; second, the Kakek (grandfather) embodies traditional cultural practice; third, the setting is a schematic version of an Australian backyard (see Figure 1.2).

The diagonal vector which constructs the scene, running left to right and top to bottom, deploys Omar’s almost central placement to emphasize his over-determined display of modern, Western male child icons: reversed cap, back-pack, Walkman, skateboard, basket-ball, Nike trainers. His difference from his grandfather is underlined by repeated colours (each has a garment of red and green), the contrasting head-wear and foot-wear, and the contrast between his grandfather’s distinctively Indonesian features and his own less marked features. The scene, then, both depicts cultural fissure and foregrounds Omar’s globalized lack of cultural distinctiveness.

Di Wu interprets some iconic features used to represent an Australian backyard – the tree, the style of house, and the clothes-line (known as a ‘Hills hoist’) – through Chinese painting techniques. The house architecture alludes to a late Victorian cottage design, which is a local icon that frequently appears in Australian picture books, even though examples in Australian suburbs are now becoming rare. The tree, prominent in the foreground, is aesthetically Chinese, and this aesthetic further shapes how viewers look at the house and the Hills hoist, visualized from the elevated near-to perspective of a Chinese painting. The effect is comparable to that seen in ‘The Jackpot’, in that the sub-schemas that comprise the ‘Australian backyard’ schema both instantiate that schema and indicate that the historically familiar components can be re-signified if presented in a different representational style. The setting has thus been glocalized by this blending of artefacts and pictorial codes from different cultures. Against this background setting, the grandfather and Omar embody extreme cultural diversity. The verbal text declares a problem in culture – ‘Omar was in trouble the moment he stepped into the backyard. The kakek was sweeping the earth before him with a feather.’ The nature of this trouble, however, lies not so much in what Omar has done but in his personal embodiment of culture and its opposition to the culture practised by his grandfather. As the story unfolds, Omar enters into a local/global dialogue by setting out to reclaim his heritage. He does this by building an Indonesian dragon kite for his kakek. Once again, however, the kite is depicted from a Chinese perspective, thus modifying the local by envisaging a kind of global Asian dragon-image. Despite the introduction of this other form of globalization, Baillie and Wu are still able to represent a hybridization of local and global as a glocalization that restores meaning to community, as the final openings of the book depict the kite in flight and assert the healing of the cultural divide.

Figure 1.2 Old Magic by Allan Baillie and Di Wu,4 Opening 1

A further key schema is evoked here with an effect again quite similar to that identified in the Ahlbergs’ text. The dragon kite is an idea in the mind, constructed and remembered by traditional cultural practice. But that schema can be instantiated by bringing together surprising, nontraditional variables (such as sheets of plastic and table-tennis balls) so that they form a signifying pattern. When Omar and his kakek fly the kite together, their physical postures are an isomorphic mirroring, and this pattern is repeated in the sky above them where Omar’s kite is doubled by a cloud-shape once again painted by means of a specifically Chinese technique. The complex patterns constitute a highly expressive integration of cultural forms.

Multiculturalism, in conjunction with the dominant theme of children’s books, that of personal identity development, has been concerned with ways whereby social conjunction and communalism replace conflict and overcome difference to bring about multicultural awareness and agency. In other words, a book such as Old Magic conforms to a particular narrative script. Readers may sympathize with Omar, but the script – an action structure consisting of conflict, self-reflection, creative action, and social integration – invokes a cultural and cognitive stereotype about identity that indicates Omar is in the wrong in embracing shallow post-modern culture at the cost of his cultural heritage. Baillie has used a script here that is very common in picture books, and its very stereotypy is quite powerful in affirming an outcome that embraces cultural diversity.

Wherever questions of difference are addressed in picture books, the cognitive instruments employed to model attitudes and possible transformations in attitude are apt to pivot on the representations of scripts and schemas. The process is principally characterized by the unfolding of a schema to a point of full realization, which in turn may take several forms. It may disclose a social good which one or more of the represented participants must recognize and embrace, as in Michael Rosen and Bob Graham’s parable This Is Our House (1996), or which defines a central participant’s state of lack, as in Liz Lofthouse and Robert Ingpen’s Ziba Came on A Boat (2007); it may express a cultural assumption in such a way that readers will feel obliged to reject it, as in Armin Greder’s The Island (2007; originally Die Insel, 2002); or it can be transformed from a negative to a positive signification, as in Allan Baillie and Caroline Magerl’s Castles (2005). In all of these variations, schemas develop metonymic functions, and scripts evolve into full-blown parables. The script in each is based on the four-component structure observed in Old Magic (conflict, self-reflection, creative action, and social integration), although not all four are equally realized in every case, and creative action may be distributed variously amongst participants.

Schema and the development of metonymic function

An overt example in which basic cognitive instruments become metonymy and parable is This Is Our House (1996), a story about a group of small children struggling to enjoy the use of a large cardboard box they have re-described as a ‘house’. At the beginning, one of the children, George, commandeers the house:

George was in the house.

‘This house is mine and no one else is coming in,’ George said.

‘It’s not your house, George,’ said Lindy. ‘It belongs to everybody.’

‘No it doesn’t,’ said George. ‘This house is all for me!’

(Rosen & Graham, 1996: unpaged)

George’s schema for belonging and exclusion is framed by a speech act, ‘This house isn’t for ...’, which introduces each of the sub-schema categories he identifies as elements of difference that justify exclusion. The text deals with a problem of relations between groups, where those marked as Other are a problem for the protagonist, but not the actual root of the problem, since difference is being imposed upon them. George at no point evokes race as a cause for exclusion, though Graham’s illustrations indicate that this is consistently an oblique motive. For example, when Luther (depicted by Graham as of Caribbean descent) enlists Sophie’s help, they are rejected because Sophie wears glasses. Graham’s illustrations situate the ‘house’ in an open space surrounded by high-rise residential buildings. Visually, it is like an island, and evokes 1990s discourses in which, as Elaine Vautier succinctly expresses it, ‘Britain is figured as a small island with capacity limits and a precarious balance to be maintained against the invasion of foreignness by outsiders who bring their unwanted alien cultures’ (2009: p. 131). The most explicit reference to ethnicity occurs when Rasheeda (ethnically South Asian) decides to tunnel into the ‘house’, with all its hints of illicit entry by would-be migrants, but the text/illustration interaction consistently prompts a metonymic reading of the schema as racialized exclusion. The conflict which drives the script is constantly challenged by the creative action of the excluded children, who devise inventive and socially constructive reasons for entering the ‘house’, but finally can only transform the situation when George must leave to go to the toilet. On his return, to find the house crammed with the other children, his practice of arbitrary exclusion is turned against him – ‘ “This house isn’t for people with red hair,” said Charlene.’ After a futile outburst of frustrated rage, George engages in self-reflection, abandons his obsession with possession and control, and transforms his grounding schema, so that the ‘house’ is ‘for everyone’. The final phase of the underlying script – social integration – thus emerges as the book’s predominant theme.

This story about a group of children struggling over enjoyment of an imaginatively transformed site succinctly illustrates how a schema develops metonymic function: a cardboard box is also a house, and the house-schema is a metonym for a community, and eventually a country. The signifying process is thus a figurative chain, as the tenor of one figure becomes the vehicle for the next. The figures are metonyms, rather than metaphors, as each tenor maintains its significance as well as acts as a vehicle in a process of further figuration:

At each stage of meaning transfer the figurative ground linking vehicle and tenor is ‘a habitable space shared by a group of people’, and hence the transformation of the schema within the script of conflict, creative action, self-reflection, and social integration readily enables the interpretative step that enables an understanding of the narrative as a parable about discourses of inclusion and exclusion in England in the 1990s.

Schema and script in the metaphorical relationship of verbal text and illustration

Creative action may be represented as a pivotal narrative element in schema transformation, as demonstrated by Allan Baillie and Caroline Magerl’s Castles (2005). As with This Is Our House (1996), a crucial element of this book is that the script – here a clearly articulated version of the conflict, creative action, self-reflection, and social integration script – assumes there is always some form of suspicion of, and hostility towards, otherness in initial encounters with strangers. This suspicion is constituted as a problem that needs to be overcome. In other words, the script naturalizes self-other conflict, and if this is taken to be an everyday life schema – a pre-stored knowledge representation – then self-other relations will always have a fragile basis. In this case, the script is instantiated in a way that conflict is overcome. Like This Is Our House (1996), Castles (2005) is about a struggle for territory, but in this case between a girl and a boy on an otherwise empty beach.

Castles (2005) follows a picture book convention whereby a metaphorical relationship is established between verbal text and illustration because each of these semiotic codes tells a different story. The strategy is varied here because both codes cross from time to time between a depiction of children playing on a beach and the fantasy world they imagine (readers may immediately recall the great pre-text for such dual narratives, John Burningham’s Come Away from the Water, Shirley [1977]). Castles is grounded in the story opening by the schemas princess and castle:

One day a Princess came to the beach. She built a castle.

The illustration depicts an everyday beach scene, in which a young girl in a swimming costume builds a sand castle. At this point, Princess is an indeterminate term, either a general descriptor or the girl’s self-image. The second opening introduces a different castle schema, that is, what the girl imagines her castle to be: ‘A wondrous castle. Its gleaming towers were so high their bright banners tickled the drifting clouds.’ The illustration also shifts to represent this schema, both in castle architecture and the princess’s clothes. The ground has now been laid for text and illustration to interact by variously depicting the everyday and the imaginary and hence to interrogate how the princess schema functions to express a sense of self. How this sense of self is depicted in Castles (2005) accords remarkably closely with the elements identified in cognitive psychology as central to a self-schema. According to Jean Knox, these are: the central role of physical action in creating agency and identity; the importance of the bodily perspective from which one views the world; the question of peri-personal space; and the impact of other people on our sense of self and our experience of identity and agency (Knox, 2009: p. 308). When the ‘Princess’ finds her essentially solipsistic fantasy intruded upon by a newcomer – a boy simply labelled as a Pirate – each of these elements that ground the self must be modified or activated as the narrative script unfolds by means of some contrasting schemas:

Then on a dark afternoon a Pirate came along the beach.

‘Watcha doing?’ he said.

‘Something,’ said the Princess, trying to ignore him.

But the Pirate built a pirate ship with cannons next to the castle.

(Baillie & Magerl, 2005: unpaged; my emphases)

Constructing her castle in isolation does not constitute the girl’s agency and identity any more than does her Princess-perspective on her real and imagined worlds. While Knox defines peri-personal space as the space within reach of a particular part of the body (such as the hand), she also notes that the use of tools or implements expands the reach of peri-personal space so that ‘far’ space becomes ‘near’ space (2009: p. 318). Also pertinent here is Jean Mandler’s suggestion (after Lakoff and Johnson) that image schemas – the means whereby ‘spatial structure is mapped into conceptual structure’ – underlie a person’s understanding ‘of the metaphorical extensions of objects and events to more abstract realms’ (Mandler, 1992: p. 591). This Is Our House exemplifies how George’s peri-personal space within the carton/‘house’ readily takes on the meaning of a metaphorical space, and likewise in Castles the operations of mind and imagination also function as tools to extend peri-personal space by converting ‘far’ space into ‘near’ space. Hence the Pirate’s aggressive response to the Princess’s act of exclusion (implicitly a gendered act) challenges her peri-personal space in both physical and mental domains, and this becomes an important first step in transforming script into parable.

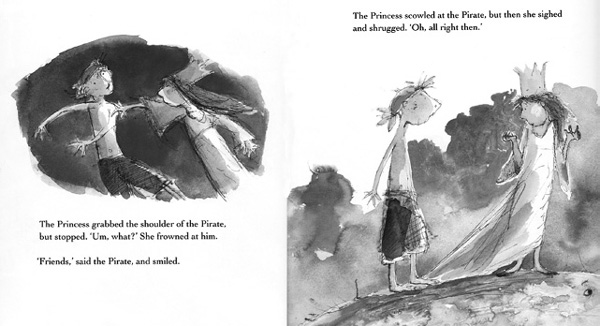

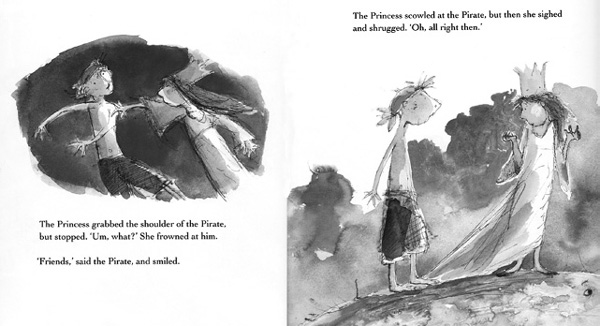

In a travesty of creative action Princess and Pirate project girl-boy rivalry through a script for a fantasy war, which is played by imagining monstrous flying creatures as weapons. The strategy – and hence the rules of the game – is initiated by the Princess, who maintains the upper hand until the Pirate makes a surprise move and disconcerts the Princess by proposing a truce and friendship. Self-schema is then transformed in the sequence depicted in opening 13 (see Figure 1.3): on the left-hand page, the girl asserts control, and hence agency, by a physical gesture that dominates the boy’s peri-personal space (an aggression-schema is evoked visually by her out-thrust arm and acute body angle); the boy, in contrast, leans back and holds his arms away, where they are visible and also form an embracing oval shape that visually echoes his verbal proffer of friendship. On the right-hand page, peri-personal space is neutral but expresses potential in a moment of self-reflection, as is evident in the slightly forward-leaning heads and the visible hands. At this point each child is poised to impact upon the other’s sense of self and exercise of agency. Social integration follows, as the two join hands, and the final opening depicts the two in everyday beach costume happily chatting as they lie together on the girl’s beach towel.

The capability of a picture book to transform the conflict, creative action, self-reflection, and social integration script into a parable about human relations in general and the importance of others to individual subjectivity formation are readily evident in Castles (2005). The same script can, of course, be varied. The perspective of the Princess dominates Castles, if only because she is first to stake a claim to the territory. But the perspective can be inverted if notions of place and ownership are contested.

Schema construction and social context

A common strategy in picture books and narrative fictions for young readers is to instantiate a core schema by accumulating a mix of essential and optional components of the schema across the extent of the text (see Stephens, 1995). This is a powerful strategy for inculcating, questioning, or modifying a schema, and has great potential for thematization of cultural diversity as racial difference. A good example of such schema construction, within a context that renders the framing script variable, can be seen in Armin Greder’s The Island (2007), which demonstrates both an extended schema (stranger) and a locally instantiated schema (wall). Greder first published the book in German (Die Insel, 2002) and an English version was subsequently brought out in 2007 by an Australian publisher (Greder has published in both German and English from time to time). In between these editions, Die Insel had been translated into several other languages. The multiple contexts in which Die Insel/The Island has appeared have significant implications for the text’s schemas, because the very different contexts of reception (re-)create effectively different books. In a review of Die Insel, Herbert Huber related the book to xenophobia in Germany and Europe more generally (‘Fremdenfeindlichkeit ist allerorts spürbar (nicht nur in Deutschland)’),5 and connected the wall built around the island in the book’s penultimate opening with predominantly right-wing demands to wall off Europe from outsiders (‘Europa ist gerade dabei die Mauer um die EU ... weiter zu verstärken’). The Australian edition of The Island (2007) was published without the subtitle that had appeared in the German (and translated) editions – Eine tägliche Geschichte (‘An Everyday Story’) – and without the expansion of this idea that had appeared on the back cover (Eine tägliche Geschichte/ über den Umgang mit den Fremden und über die Mauern in den Köpfen ‘an everyday story about dealings with strangers and the walls inside the head’). A potential effect of this change is to narrow the application of the book, so that it would be usual to read it specifically as a protest against the then Australian Government’s draconian policy on refugees and border control. Instead of a metaphorical wall around the European Union, Australian readers would interpret the wall as literalizing the fortress mentality pursued by government and its cultivation of what Wayne Weiten (2001: p. 561) refers to as ‘catastrophic thinking ... which involves unrealistically negative appraisals of stress that exaggerate the magnitude of one’s problems’. Thus the treatment of the stranger washed up on the island’s shore has strong local resonance: the islanders ‘took him to the uninhabited part of the island, to a goat pen that had been empty for a long time ... then they locked the gate and went back to their business’. In 2007, any illegal immigrants who attempted to reach Australia by sea were detained in remote, inhospitable camps or sent to some small neighbouring countries which had been funded to establish detention centres there.

Figure 1.3 Castles by Allan Baillie and Caroline Magerl, Opening 13

According to this localized reading, The Island (2007) exemplifies a post-multicultural mentality that had emerged in the ten years preceding its publication. Australia officially declared itself a multicultural society in 1972, and for the next 25 years Australian children’s fiction was constructed either in terms of a narrative which saw Australian culture as moving from a society imagined as grounded in the values of a settler culture with British origins to one embracing cultural diversity; or, alternatively, as a narrative depicting Australia as always already a multicultural society, proclaiming the existence of multicultural tendencies long before modern multicultural policy. Few twenty-first-century texts have reproduced either history, however, and this is probably because between the election campaign of 1996 and the subsequent rhetoric of ‘homeland security’, which culminated in the shameful handling of illegal immigration in 2001 and beyond, the concept of a multicultural Australian society was ‘disremembered’,6 even if the fabric of society was not affected. As the ethnic other became identified politically as would-be migrants from Asia attempting to enter Australia illegally by boat, the multicultural migration narrative in children’s literature became replaced by a new, more politically pointed genre, the refugee narrative.

What the cover summary of Die Insel (2002) referred to as ‘mental barriers’ (die Mauern in den Köpfen) are evident as a hostile stranger-schema which constrains the narrative script of conflict, self-reflection, creative action, and social integration because it precludes both creative action and concluding social integration. The Island (2007) is presented from the perspective of the island’s inhabitants, who throughout the book accumulate a bundle of components of a xenophobic schema for outsider, stranger (the schema is overtly identified as a ‘stranger’-schema towards the end of the book when the people decide to take the man, put him on his raft, and push him back out to sea). The following descriptors are thus applied to the stranger:

Not like them

‘Wouldn’t like it here’

‘Would probably work for less pay’

Unhygienic

Unskilled

Unfit for work

Culturally alien

Is a ‘savage’

‘Eats with his hands’

Is a threat to the community

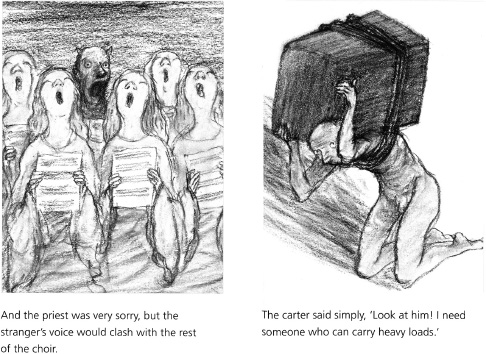

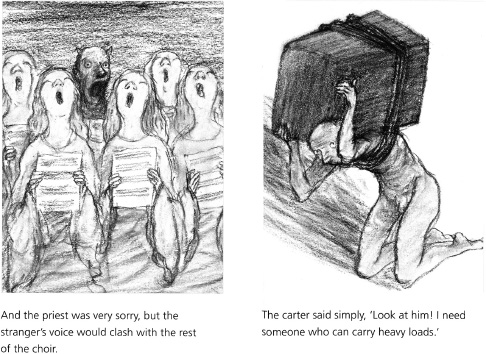

This schema-building commences with opening 1. In a discussion of system justification theory, Kasumi Yoshimura and Curtis Hardin (2009: p. 298) explain that ‘people view group differences and social inequality as legitimate and natural because of epistemic, existential, and relational motivations to justify and rationalise the existing social order’, and the full range is exemplified in the stranger-schema in The Island (2007). In opening 8 (Figure 1.4), for example, an epistemic community is evoked by the carter and the priest adducing, respectively, existential and relational reasons for excluding the stranger: he cannot carry heavy loads and his voice ‘would clash with the rest of the choir’.

The illustrations function in ironical relationship with the text, an irony emphasized by the reciprocal eye contact between the stranger and viewers: in the carrying scene, eye-contact from above the kneeling figure stresses that the imaged load is too heavy for anyone to lift, and in the choir scene, where the stranger is explicitly demonized by the attribution of devil’s horns, dark skin, and a position behind the other singers (the devil’s position), eye-contact past the choristers establishes an appeal against this imposed positioning. Here, and pervasively, the illustrations show that the islanders’ shared beliefs and pressure on their fellows to conform – and hence the stranger-schema they construct – are xenophobic and unnecessary. Devoid of both self-reflection and creative action, the islanders corrupt creativity into phantasmagoric nightmares of otherness. Many children will recognize the citations of iconic images of anxiety from F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922) or Edvard Munch’s The Scream (one of the works of art most frequently cited in picture books), but many will also recognize Fuseli’s The Nightmare from Anthony Browne’s earlier citation of it in The Big Baby.

Figure 1.4 The Island by Armin Greder, Opening 8 (right-hand page)

Greder doesn’t close the book with the bleak images of the islanders’ inhumanitarian action in pushing the stranger out to sea and out of the book, but with a final account of their subsequent isolationism and cultural loss. In this way, it suggests a powerful statement about some consequences of a move away from a society committed to multiculturalism.

Schema and empathic imagination

The function of script and schema as cognitive instruments for portraying cultural difference is illustrated in a contrastive way in another refugee narrative, Liz Lofthouse and Robert Ingpen’s Ziba Came on a Boat (2007). In contrast to The Island (2007), which elides any possibility of attributing subjectivity to the stranger, Ziba Came on a Boat works by narrating the inner thoughts and memories of a child on a refugee boat, a strategy which minimizes the text’s status as fiction and privileges instead the activity of empathic imagination. The mixing of high modality and soft focus in Robert Ingpen’s illustrations works beautifully with the text to mediate relations between familiarity and otherness, especially in the way the book embeds a major schema within its narrative script:

Schema: normal childhood belonging

laughter of children

peaceful environment

friends

everyday play

shared family life

parents’ everyday activities

story-telling

belonging in culture

education and schooling

life without fear

freedom

An important aspect of this schema is its normative content, even though what is visually represented in the illustrations will seem alien or exotic to Western children. The familiar script of conflict, self-reflection, creative action, and social integration is deployed here in a way that neatly counterpoints the schema, in that the conflict stems from living in a war zone, but is then deeply experienced as a loss of a normal childhood schema. The verbal text presents self-reflection not merely in the form of memories and hopes but in a rhythm of travelling that interlinks the motions of the boat and the motions of Ziba’s mind. Her memory of her mother busy weaving is a simple example, but its deft combination of simile and metaphor maintains a figurative and imaginative discourse:

Up and down went the wool, in and out,

like the boat weaving through the murky sea.

(Lofthouse & Ingpen, 2007: unpaged; my emphasis)

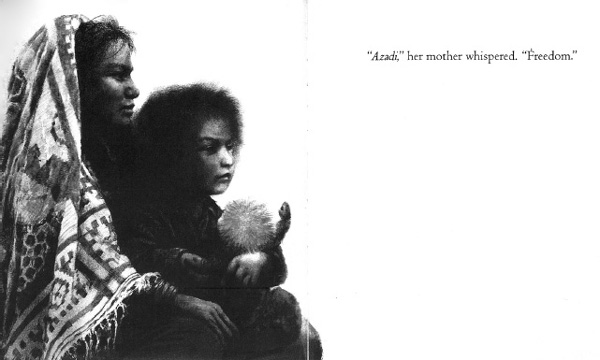

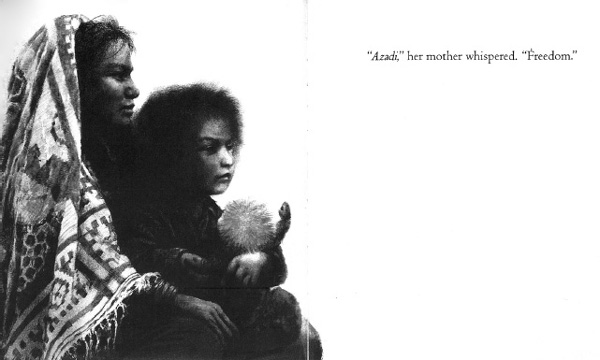

By playing out the script as a story about a journey taken while confined on a small boat travelling through ‘an endless sea’, and by evoking the normal childhood schema as loss and absence, Lofthouse depicts a curtailment of Ziba’s self-schema. Her peri-personal space is constrained by the situation, and her opportunity for creative action is limited, except that it occurs as the mind figuratively processes its thoughts and memories and thereby enacts the impact of other people on subjective agency. Because the book doesn’t offer an arrival, the self-schema is posed as a future possibility. The third opening before the final one (Figure 1.5) offers what is described as a ‘dream’ – a reinstatement of the normal-childhood schema in a welcoming, multicultural society, as depicted in the illustration (although not stated as such in the text). This image combines with the penultimate opening to express the hope of social reintegration (although this hope is modified by the final opening’s reminder that arrival has not taken place). The penultimate opening is structured as an image of hope, with mother and child gazing towards the right-hand page which is empty apart from the five words which express hope for the future: ‘ “Azadi,” her mother whispered. “Freedom.” ’ The empty page emphasizes the left-to-right, top-to-bottom vector running from mother to daughter to doll – a very expressive representation of cultural otherness unfolding symbolically into the schema of everyday childhood.

The ending of Ziba Came on a Boat (2007) is very open: the past tense of the title suggests there has been an arrival, but this isn’t shown on the final page. Adult readers know all too well that at the time of the book’s publication what awaited Ziba was not that happy multicultural childhood affirmed by Ingpen, but indefinite detention. That, fortunately, is no longer the case. Again more for adult readers is the context in Australia of the cry Azadi, a catchword frequently shouted by Hazara people from Afghanistan during demonstrations in Australia against detention policies (and the title of a notable docudrama on this topic).7 Ziba Came on a Boat espouses a politics of refugee visibility in opposition to the oppressive practices of detention offshore or in a remote region, and it does so through narrative strategies that promote the visibility of other people’s cultural values while proposing a restoration of basic human practices. To engage in debate about the status of refugees and the failure of multi-cultural policy, it makes very effective use of the structure of script and schema.

Figure 1.5 Ziba Came on a Boat by Liz Lofthouse and Robert Ingpen, Opening 14

As vital cognitive instruments, script and schema prove to be widely powerful strategies for investing normative cultural ideas with richness and subtlety. In the case of the representation of cultural diversity, the particular domain I have taken as my focus here, script and schema function as transformative instruments, enhancing understanding of relationships between selfhood and otherness and informing social action designed to foster equity and social justice.

Further Reading

Gavins, J. & Steen, G. (eds) 2003. Cognitive poetics in practice. Routledge, London.

This collection of essays is a useful introduction to cognitive poetics as a field in literary criticism. Contributors show how cognitively oriented theories of language can be used to read literary texts (although there are no direct applications to children’s literature). Of particular interest are the essays by Crisp, Burke, and Semino which explore how the body’s perceptual interactions within the world structure conceptual representations of that world.

Herman, D. 2002. Story logic: problems and possibilities of parrative. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln. Ch. 3.

Starting from the distinction between a mere sequence of actions and a narratively organized sequence, in this chapter Herman explores the implications of various uses of the script concept, ranging from knowledge representations of actions bound up with everyday life to the plot structures readers use to anticipate story logic.

Stephens, J. 1995. ‘Writing by children, writing for children: schema theory, narrative discourse and ideology.’ Revue Belge de Philologie et d’Histoire, vol. 73, no. 3: pp. 853–63 (revised and reprinted in Bull, G. & Anstey, M. (eds). 2002. Crossing the boundaries. Prentice Hall, French’s Forest, NSW. pp. 237–48).

An approach (through cognitive poetics) to how schemas function within a child’s capability for making sense of the world and shaping it as narrative, and how writing for children addresses this capability. Turner, M. 1996. The literary mind. Oxford University Press, New York.

An important work in the emerging field of cognition studies in literary and narrative theory (as well as other disciplines), Turner’s study examines the cognitive principles at work in the domains of discourse interpretation and narrative comprehension, and in doing so it includes close discussion of image schemas.

Notes

1The concept derives originally from cognitive linguistics (especially the work of Lakoff and Johnson (1980) on image-schemas), and more recently from computer technologies. In the last few years it has been taken up in significant ways in areas of narrative theory that are drawing on theory of mind – for example, David Herman’s Story Logic.

2In earlier studies (Stephens, 1995 and 2002; Tsukioka and Stephens, 2003) I subsumed script within schema, distinguishing object or image schemas from story or narrative schemas. Here I follow the practice in neo-narratology of referring to the latter as scripts.

3As Anna Katrina Gutierrez puts it (2009: p. 160), glocalization reconciles globalization and local resistance ‘by appropriating the global and localizing it, thus taking the foreign element and giving it a local flavour, returning it to the world with a new significance’.

4I wish to thank the following for permission to reproduce the illustrations in this chapter: Allan Baillie, for Old magic; Penguin Australia, for Castles and Ziba came on a boat; and Allen & Unwin, for The island.

5The issue was earlier comprehensively summarized by Jacqueline Bhabha (1998: p. 596) in a categorization that implicitly anticipates Kymlicka’s tripartite structure: ‘Distinctions between [European] Union citizens, third-country nationals, settled integrated residents, more temporary migrants, single and dual nationals, and monocultural and multicultural families generate contestation as to whether the terms intimate consequences of difference. At issue is whether national, ethnic, racial, or religious characteristics affect eligibility for the benefits and protections traditionally associated with citizenship. Many of the divisive political issues that have arisen over the past twenty years within the boundaries of individual member states now arise within a broader European context’.

6See Jessica Raschke, ‘Who’s knocking now?’ (2005); John Stephens and Robyn McCallum, ‘Positioning otherness’ (2009); Huggan, Chapter 4.

7Azadi (2005), an Australian short film, written and directed by Anthony Maras, explores the issue of mandatory detention of asylum seekers in Australia.