In 1992, during the construction of a gas pipeline, the Archaeological Superintendence of Naples and Caserta, under my direction, undertook emergency excavations at Cumae (Campania).1 Architectural remains, dating back to the Roman age, were found on an area of about 480 square meters, lying on the site identified by Paget2 as pertaining to the Greco-Roman port of the town, right in the middle of what was argued to be the access canal (Fig. 13.1). The excavations brought to light some fragmentary Egyptian statues and various scattered fragments of Egyptianizing materials. A collaborative team of classical archaeologists and Egyptologists was formed with the purpose of approaching the site from different points of view.

According to many scholars, first of all to Paget, the ancient harbor of the Greek and Roman town of Cumae occupied the bay lying to the south of the promontory on the top of which the Cumaean acropolis was set. At present, the area is completely filled up by coastal sediments. Geoarchaeological cores have proved that in ancient historical times, the harbor of Cumae was located in the lake of Licola in the northern area of the town, whereas the area at south never was a harbor.3 Although the form and the function of most of the structures are mostly identifiable, some remains of the complex pose problems for which the present report cannot offer definitive solutions. These problems are mainly due to the fortunes of preservation. Other uncertainties remain because a railway and modern cultivations have inhibited excavations in certain critical areas. Further excavations in these areas, conducted by the Centre J. Bérard of Naples for the Project Kyme I and II, proved the existence in the area of many villae maritimae.4 For this reason, we cannot exclude the possibility that some natural or artificial canals and basins, connected to the sea or to spring water, were in this area in antiquity. Although this is very difficult to demonstrate, recent studies and research carried out by Professors F. Bernstein and D. Orr (University of Maryland, College Park), who pursued excavations in the area of the Isaeum in 1998-2000 and who are now working out their data, appear to be going in this direction.

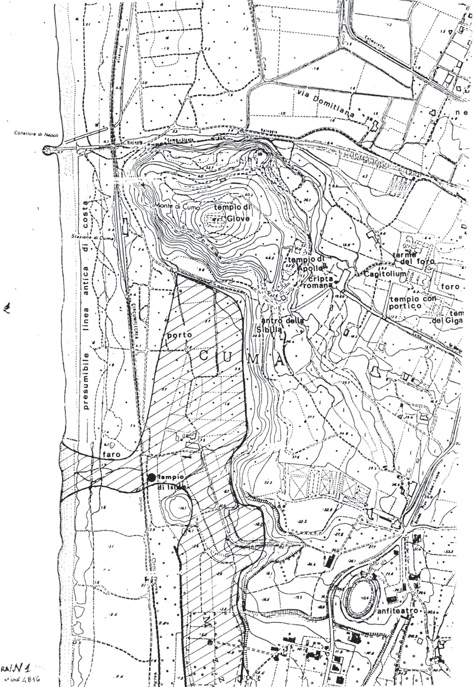

Figure 13.1. Cumae (Campaniae). The harbor area. The black point indicates the Isaeum related to the hypothesis of Paget.

It has been possible to identify (Fig. 13.2):

• Remains of a flight of stairs, leaning on the north wall of the podium (Fig. 13.3);

• part of an apsidal hall leaning on the south wall of the podium but not connected to it and with the access on the east side;

• remains of a quadrangular room on the east side of the podium, separated from the latter by an L-shaped corridor;

• a rectangular pool, facing the north side of the podium;

• remains of a porticus surrounding the pool.

It is clear from the extant remains that there were several stages in the construction of the complex. The structural sequences observed provide the basis for discerning at least four distinct building phases, dating back to a period ranging from the first century BCE to the second century CE. The type of building material used, the methods of construction, and the structural relationship noted provide the evidence.

The podium shows two different building phases (Fig. 13.4). Restoration works in its south/east side revealed a first lower structure as large as the upper one, formed by two rectangular vaulted rooms.5 They were filled up by spring water and sandy sediments that made excavations impossible; but archaeological prospecting made it possible to recognize their dimensions. The association with fragments of late Campana A dates back to not before 100 BCE. The more recent upper podium, based on little vaults in opus reticulatum, was built with the system already known in the so-called Pausilypon Temple (first half of the first century CE). The use of such a technique could be justified by the nature of the sandy soil and the vicinity of the sea. The walls of the little vaults, originally completely closed, were covered with a thin surface of signinum. The building technique (opus reticulatum of irregular type) allows it to be dated back to the second half of the first century BCE. To this period belong the flight of stairs, room, corridor, pool, and porticus, all built in the same technique. The apsidal hall was added at the end of the first century BCE or at the beginning of the following one. Later it was modified. It sets directly on the sandy soil. In a later period, the sides of the pool were made higher, together with the floor of the porticus in opus sectile, realized using tarsias of slate, old red, cipolin, and variegated marble. The floor had a complex geometrical decorative pattern (Fig. 13.5) similarly occurring at Ponza and Capri in the Augustan age and at Ostia until 130 CE.

Figure 13.2. Cumae (Campaniae). Plan of the Isaeum: A. podium; B. flight of stairs; C. apsidal hall; D. room; E. corridor; F. pool; G. porticus.

The northern side of the pool was decorated with a fountain in the Fourth Pompeian Style, as testified by shells, pumice stones, and remains of mosaics made of blue glass tesserae.6 The rebuilt section should be dated probably after the year 62 CE. Finally, the two pillars of the room in opus latericium go back to the second century CE. As in the case of the town of Cumae, the building activities stopped after this period.

While the evidence for absolute chronology for the site is limited, six major periods of its use emerge from a combined study of the finds, techniques of construction, and geological factors. Four of these six periods have left the above described architectural remains, whereas use of the site in the second and third centuries CE can be argued only on the basis of a few findings, among which are a bronze coin of Marcus Aurelius (assis, 174-175 CE, inv. 292849) and various fragments of Rough African ware. The site was destroyed probably in the late fourth century CE and abandoned, apart from sporadic use in the fifth to eighth century CE, as some fragments of Larga Banda ware witness.

The excavation of the pool, filled up with debris caused by the destruction of the roof, walls, and decorations of the building and hardened with water-lime, uncovered three Egyptian acephalous statuettes:

• Inaros as Naophorus of Osiris (Fig. 1.3.6, inv. 241834) of black basalt (height 40 cm, width 14.5 cm, thickness 17.5 cm), belonging to the XXX Dynasty (380-343 BCE);7

• an Isis (Fig. 13.7, inv. 241835) of black basalt (height 31.5 cm, width 14.5 cm, thickness 10.5 cm), dated first century BCE;8

• a Sphinx (Fig. 13.8, inv. 242046), in grey granite with green venations (50 × 15 × 16 cm), dated to the Ptolemaic era;9

• and some other marble fragments:

• six fragments in white marble, of Roman imperial age, three of them (inv. 292836: feet; 292837: right forearm; 292838: arm) pertaining to a statuette, representing perhaps Harpocrates-Horus like a child (Fig. 13.9); two others (inv. 292840: left hand holding a cornucopia; 292841: inferior limb) pertaining to a statuette representing maybe a standing Harpocrates (Fig. 13.10), whose graphic reconstruction was proposed by the author on the occasion of the exhibition Nova Antiqua Phlegraea;10

• a nemes fragment in red marble of Roman imperial age, maybe from another sphinx or from a Pharaoh statuette.11

Figure 13.3. Cumae (Campaniae). Section of the Isaeum: A. podium; F. pool.

Other objects were uncovered in the excavation of the pool:

• A fragment with the head and part of a body of a snake in black glass of Roman imperial age (inv. 292839), maybe a cultural object;

• a fragment of a mosaic (white marble; green and red glass pulp), perhaps part of the older floor of the porticus (inv. 292846);12

• a large fragment of a fresco in the initial Fourth Pompeian Style (inv. 292844), dated to the first years after 62 CE, maybe connected to the floor in opus sectile of the porticus;

• several fragments of a black fresco, probably pertaining to the wainscot of a wall.13

All of these objects evoke a deep Egyptian atmosphere and seem to have been intentionally destroyed and concealed.

This is the first evidence for the presence in Cumae of a place for the cult of Egyptian deities, apart from the uncovering of an Anubis statue (1836) and a fragmentary Harpokrates statue (1837), now lost, both of the Roman period and coming from the downtown area14 (probably from the line of the northern urban walls).

The extensive remains and the findings provide new evidence for a re-evaluation of whether Cumae also had an Isaeum.15 It is noteworthy that at Cumae, Egyptian findings, or objects imitating them, were found in several graves of the archaic Greek period, during the excavations made in the last century in the necropolis area. The hiatus recorded by the archaeological findings between the archaic Greek period and the first century BCE is probably only apparent: among the several negotiatores of Italic origin registered on the island of Delos, one (Minatos Staios) comes from Cumae and is associated with the Sarapeum; the other five belong to the gentes of the Staii, Heii, and perhaps Lucceii, whose involvement in the life of the town is well known from inscriptional and archaeological evidence. The hypothesis that such Cumaean negotiatores could have contributed, in the period ranging from the end of the third century BCE to the first century BCE,16 to the introduction of Egyptian cults in their native land, perhaps confined in the beginning within the private religious sphere, is not groundless.

The presence of the double ankh (hieroglyphic, symbol of the life) in the hand of Isis makes her a goddess of the dead, as “the goddess who brings in her hands the keys of Hell,”17 probably with the intention of representing at Cumae Isis assimilated to Selene-Luna-Hekate and to their related chthonic aspects, more than an Isis Pelagia, Euploia, or Pharia, as has until now been supposed because of the location of the remains near the sea.18 In this tradition, the presence of two lunar calendars of the Roman imperial age, carved on the walls of the so-called Antro della Sibilla at Cumae, could be explained.19 Under the same point of view, the Anubis uncovered in the downtown area, if this was not its original site but the Isaeum itself, is well connected with Isis as her son, who accompanies his mother to try to find the body of Osiris.

Figure 13.4. Cumae (Campaniae). Section of the Isaeum: A. upper podium; B. lower structure.

Figure 13.5. Cumae (Campaniae). Porticus of the Isaeum: graphic relief of the floor in opus sectile.

Figure 13.6. Cumae (Campaniae). Isaeum: Inaros statue.

The identification of the remains as the Isaeum is strengthened by the presence of the podium, the base of the temple, and of the pool for the lustral water.

As mentioned above, a fountain was found on the north side of the pool, decorated with shells. Shell decoration for nymphaea is usually associated in the Augustan age with the cult of Venus Anadyomene, who is associated with the idea of death/rebirth, and is joined to the cult of Egyptian deities or, more generally, to that of mystery deities.20 The presence at Baiae of a sanctuary dedicated to Venus Lucrina,21 located near Punta Epitaffio (in front of which a fragment of a naophorus was found in the submerged area, perhaps not accidentally), is noteworthy22 a sanctuary of Aphrodite Euploia was situated at Pizzofalcone, in Naples.23 The location of this sanctuary, on the top of a low hill facing the sea, was probably connected with coastal routes, because of their easy identification and territorial distribution.24

Figure 13.7. Cumae (Campaniae).Isaeum: Isis statue.

Figure 13.8. Cumae (Campaniae). Isaeum: Sphinx statue.

Figure 13.9. Cumae (Campaniae). Isaeum: Statue of Harpokrates-Horus like a child. Graphical reconstruction proposed by the author.

The Isaeum thus far uncovered could not be the sole sanctuary of the Egyptian cult in Cumae: the Roman Anubis statue, found near the northern urban walls, on the property of Angelo Luongo, not far from the necropolis, represented as Hermanubis in the function of Psychopompus, allows the hypothesis of a public sanctuary located in this area.

This last statue and the group of the three statuettes from the Isaeum present, however, a characteristic in common: they have all been mutilated. The statue has been beheaded, deprived of part of the face, left arm, and right hand; the group of statuettes has been beheaded, obliterated with a voluntary destructive act of the sanctuary, expressing explicit condemnation by opponents of the cult. The other two statuettes representing Harpokrates-Horus have also been completely destroyed and obliterated. This manner of obliteration of the Isaeum statuettes seems to tally with two other cases in the Phlegrean Fields: a beheaded naophorus found in the beginning of the twentieth century in the area of the Pausilypon;25 another beheaded one recently uncovered in the Collegium of Via Celle at Pozzuoli, from a stratum dating back to the fourth century CE.26 Transposed on a religious level, the symptom is very similar to the damnatio memoriae, but better expressed as Ichonarum Phobia. The subject needs to be researched, as I am in the process of doing.

Destruction must have been brought on by Christians after the Edict of Constantine (313), or probably after the Edict of Theodosius (392), because literary sources testify that the Isis cult flourished during the whole fourth century CE until the destruction of the Serapeum in Alexandria (391). This event can have taken place at the latest at the beginning of the fifth century CE, if S. Paolino, Nola’s bishop, in 404 writes against the Isis cult (Carmina 19, vv. 110-130), when the intolerance of paganism was very strong. With regard to this datum, it is noteworthy that Q. Aurelius Symmachus Eusebius (consul in 391) speaks of setting sail from his Cumanum (Ep. 2.4.2.); the villa must have been located at the sea’s edge, although we do not have further information.27 The possibility that the architectural remains were part of a villa maritima, probably his villa, seems more hypothetical. Since the Symmachi together with the Nicomachi were conspirators in the last pagan resistance to Christianity by the senatorial aristocracy, and considering the dimensions of the building and of the statuettes, it is therefore a reasonable assumption that the Isaeum was a private sacellum dedicated to the pagan cult. The conjecture that the remains were part of a villa has some basis, since recent researches, carried out in 1995 by the Centre J. Bérard of Naples in the harbor area, revealed the presence of architectural remains of three villas.28

Figure 13.10. Cumae (Campaniae). Isaeum: Statue of a standing Harpokrates. Graphical reconstruction proposed by the author.

The Isaeum is, finally, not only a new historical and topographical datum for Cumae, but also a geological and archaeological one. The podium shows two different building phases, revealed by restoration works in its south/east side. The first lower structure dates back to not before 100 BCE, most likely to the first half of the first century BCE. The more recent upper podium goes back to the second half of the first century BCE. A geological drilling, executed during the excavations, made it clear that the reconstruction was necessary, due to the subsidence of the littoral, the effects of which were previously unknown in this area. The association of the archaeological datum with the geological one has made it possible to understand that, in the period from the first half to the second half of the first century BCE, the Cumaean littoral sank 1.04 meters.

Paolo Caputo is at the Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici delle Province di Napoli e Caserta, responsible for the archaeological site and the Archaeological Park of Cumae and for the Archaeological Diving Unit of the Soprintendenza.

1. The present contribution is the result of the research and studies I have directly carried out in the last ten years after the Isaeum was uncovered. The research has been already illustrated in the following studies: Caputo 1991: 169-172; 2003a: 87-94; 1998: 245-253; 2003b: 209-220; 2003c: 45-51; De Caro 1994: 11-15; De Caro 1993-94: 189-190; Caputo, Morichi, Paone, and Rispoli 1996: 174-176; De Caro 1997: 350-351.

2. Paget 1968.

3. Pasqualini 2000: 69-70; Morhange et al. 2000: 71-82. These data contrast methodologically with the older data, coming from another analysis made in the same area: Arthur, Guarino, Jones, and Schiattarella 1977: 5-13.

4. Bats 1997: 23-24.

5. Their walls were covered with a surface of signinum. This structure could have had the function of a former podium, used probably also as a water reserve. See the case of Delos, where under Serapea A and B were built water reserves, one of which was fed directly by the Inopos. An Alexandrine literary tradition, reported also by Callimachus (Hymn to Delos 206-208), considered the river a branch of the Nile (Roussel 1916: 30-31, 45). This religious fiction had the purpose of assimilating the holy water to that of the Nile, considered holy. In the case of Cumae, the water reserves could have fed the pool for the holy water. It is perhaps noteworthy that a water-bearing stratum was found during the restoration works of the structure.

6. Caputo 2003c.

7. De Caro 1994: 12-13; Cozzolino 1997: 448; ibid.: 21-25, 31-54.

8. Di Maria 1997: 448.

9. Ibid.: 450.

10. Caputo 2000: 90.

11. Ibid.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. Ruggiero 1888: 204-205.

15. For the several Egyptian traces in Roman Campania and the introduction there of the Isis cult, see Malaise 1972a: Acerrae, 1; Ager Falernus, 1; Boscoreale, 1; Cappella, 1; Capua, 1-4; Carinola, 1; Cumae, 1; Herculaneum, 1-5, 7-10 ter, 20; Liternum, 1; Misenum, 10-13; Neapolis, 1, 3, 4, 7-12; Puteoli, 4, 9-18, 28; Stabiae, 1-2; Aeclanum, 1; V. Tran Tram Tinh 1964, 1972; Mueller 1969; DeCaro 1992. For the introduction of the cult at Cumae, see above, note 1.

16. Hatzfeld 1912: Heii, n. 1, pp. 41-42; Lucceii, n. 1, p. 47; Staii, nn. 1-4, p. 80. See also Malaise 1984: 1615-1691.

17. Apul. Met. 11.

18. Also the sanctuary of Fondo Iozzino at Pompeii was located outside the town, near the mouth of the river Sarno and in the harbor area, not very far from the Porta Nocera. The site, occupied from the Archaic age, was reorganized in the Samnitic period (third century BCE). A thick enclosure wall circumscribed the area, inside which another surrounding wall delimited three small temples. Two clay statues of women were found near two of them (ending of the second/beginning of the first century BCE). One statue is identical to a Rhodian type representing Hekate-Artemis. A replica comes from the Monte Santo Stefano, a Rhodian sanctuary, where the cult of an infernal deity is proved. Both statues allow the identification of the sanctuary near Pompeii as dedicated to Demeter, a land goddess, whose cult is located outside the town, where Hekate’s cult is also attested; see S. De Caro in Zevi 1991: 41-42.

19. Ruggieri 1998: 68-80.

20. Gros 1976: 138-143.

21. J. Beloch (1890: 178) situates the temple on Punta dell’ Epitaffio. Although architectural remains are not individuated, the sanctuary is testified by literary historical sources (Stat. Silv. 3.150; Mart. Epigr. 11.81) and an inscription (CIL 10.3692).

22. Di Fraia, Lombardo, and Scognamiglio 1986: 221 n. 22, figs. 2-3; Pirelli 1997: 450.

23. Napoli 1967: 418; Stat. Silv. 2.2.76-82 and 3.1.149; IG 14.745 and p. 690; Peterson 1919: 200.

24. See Napoli 1967: 418.

25. De Caro 1994: 15.

26. Cozzolino 1997: 451; Cozzolino 1999: 25-31.

27. D’Arms 1970: 226.

28. See Bats 1997.