Within the now considerable corpus of scholarship devoted to the antique body, the Roman cult of Mithras has been prominent mainly by its absence.1 Neglect is not difficult to explain. The obsession with deciphering the “true” meaning of the cult relief, the identification of the cult as an “astral religion,” the fixation upon origins, the silence of the literary sources, our ignorance of Mithraic ritual practice, and more important still, the difficulty of adapting a theoretical discourse elaborated elsewhere for a cult attested almost solely through archaeology and the uncertain value of the results to be expected—all these factors have contributed to this neglect. Moreover, the cult’s initiatory character has encouraged the assumption that the function of initiation was primarily discursive, to impart a specifiable quantum of Mithraic lore expressible in discrete constatives. Against this background, the potential value of taking the body as our point of entry is that it allows us to raise the issue of whether initiation in this cult gave rise to a type of knowledge or understanding that can be termed specifically Mithraic. In this chapter I wish to suggest that it did, in that important aspects of Mithraic identity could only be transmitted effectively “through action, enactment, performance,” not through language.2

As with all treatments of the ancient body, we are dealing in the case of the cult of Mithras only with mediated or represented, and thus constructed and notional, male bodies. Even with this proviso, however, the material, textual and iconographic, available for exploitation is wretchedly small. Reliable textual evidence, so important, for example, in relation to the cult of the martyrs (Grig 2004), fails entirely.3 By comparison with the iconographic material from other “universal” cults in the Roman Empire, those of the Mater Magna and Isis in particular, there are almost no images of Mithraists: the complete—and most curious—absence of Mithraic funerary iconography is one reason for this; another is the absence of relevant narrative or “documentary” panel paintings from Pompeii or Herculaneum. To an overwhelming degree, the surviving Mithraic body is, as it were, the body of Mithras himself; Mithraic art directs the implied gaze almost exclusively toward the god and, as an afterthought, his assistants, the twins Cautes and Cautopates (Elsner 1995: 210-221). That said, four classes of images of Mithraists survive, all from within the context of temple decoration: 1) images of servants at the sacred banquet of Mithras and Helios, who thus mediate directly between mythic model and cult-praxis; 2) one or two groups of banqueters within the context of the cult image, who likewise mediate between myth and praxis; 3) the images of grade members, some as types, some “portraits” with personal names, at S. Prisca, probably also on the columns supporting the roof of the Barberini mithraeum (CIMRM 394), both in Rome; and 4) images of initiation. I propose to discuss here only this last category, which consists, with a handful of exceptions, of seven individual images from the mithraeum of S. Maria Capua Vetere in Campania. This choice was of course suggested by the fact that Capua lies only a short distance from the Villa Vergiliana in Cuma; and indeed, the members of this conference were able to visit the mithraeum courtesy of the Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici delle Province di Napoli e Caserta.

Since these images of men undergoing different, but apparently unpleasant and frightening, initiation rituals are unaccompanied by any kind of text, their role in the mithraeum, and more generally in the cult, remains uncertain. It can be understood, if at all, I suggest, only by the rather lengthy detour taken in this chapter. I present first an archaeological account of the paintings and their subjects, based upon the original report by Minto and the more recent treatment by Vermaseren. The following sections offer two different approaches to their contextualization, the first with reference to the Foucauldian théâtre de terreur, the second to Christian patientia.

Two features of the podium frescoes at Capua—their poor state of preservation and their failure to perform the service required of them by the commentators, namely to “illustrate” rituals known from, or at any rate alluded to by, literary sources—no doubt explain why, despite their obvious importance, they have been relatively neglected in the specialist literature. Of recent standard publications, Reinhold Merkelbach devotes just a few lines to them, without any attempt at closer analysis (1984: 136-137).4 Robert Turcan (2000: 84) and Manfred Clauss (2000: 103) are likewise rather off-hand. Only Walter Burkert (1987: 102-104) has properly emphasized their exceptional nature in the evidence for ancient mysteries.5 Minto himself deplored their state of preservation when they were found.6 The only color plates available, from photos taken in 1967 by Antonio Solazzi, when the mithraeum was in a poor state of repair (the Soprintendenza has devoted laudable efforts recently to dehumidify it), were published by M. J. Vermaseren in his brief monograph devoted to the temple (1971), and subsequently re-used by A. Schütze (1972).7 Since color plates were not available for the present volume, although they are really the only, albeit inadequate, means of illustrating the remnants of the podium frescoes, I have adopted the pis-aller of confronting the earliest published images, those of Minto, with rough tracings based on Vermaseren’s plates. Where these do not agree, Minto’s images, although far from satisfactory, should be given greater weight because of the massive deterioration during the intervening half-century.

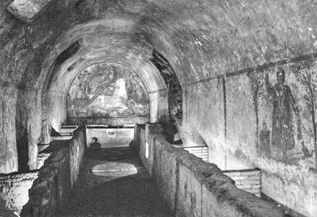

Figure 16.1. Capua general.

The mithraeum of S. Maria Capua Vetere, one of the best-preserved ever found (Fig. 16.1), was discovered in late September 1922 during work for the foundation of a house in the vico Caserma, about 450 m south of the Roman amphitheater, and excavated early in 1924 by A. Minto (Minto 1924). Like the mithraea at Caesarea Maritima in Judaea and at Marino in the Alban Hills, the temple was constructed in one of several series of intercommunicating vaulted cryptoportici, evidently used for storage of wine or the like, which seem to have occupied several areas in the center of the city. The mithraeum, oriented due west-to-east (cult fresco to the west, rear wall with fresco of Luna to the east), was fitted up in the hindmost room of its series, which had been built c. 100-140 CE not far from the Capitol. It was approached by a passage 3.30 m wide (Fig. 16.2a, area denoted o), which was, however, partly blocked in Phase III by the extension of the southern podium. The internal dimensions of the cryptoporticus are 12.18 m x 3.49 m, the height of the vault 3.22 m.8 Set high up in the southern vault were three trapeziform scuttles to provide daylight when and as necessary (Fig. 16.2a).

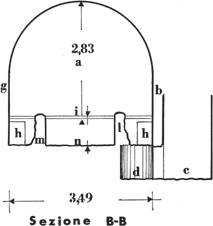

The mithraeum seems to have been established on a modest scale in the latter part of the reign of Antoninus Pius, or perhaps under M. Aurelius and L. Verus. Because it had been carefully cleared and then partly filled with rubble before being abandoned, no furnishings, pottery, or coins were found in situ. Dating the phases of use is therefore attended by more than the usual uncertainties. Largely on the basis of stylistic differences between the paintings, Vermaseren (who did not conduct any new excavations) distinguished three phases, two with subdivisions. In Phases I and IIa-b, there were no podia of the kind usually found in mithraea. Instead, there were low seats (Fig. 16.2b, at h), 1.25 m long, 0.39 m wide, and 0.45 m high, which on the left (south side) abutted a water cistern, 0.55 m deep, and on the right (north side), a basin connecting with a deep sump or drain (Fig. 16.2b, at d).9 The implication, I think, is that in these two phases, meals were eaten from portable lectus in the eastern part of the temple, toward the entrance. This hypothesis is supported by the facts that 1) the wall-paintings of Phase IIb, which continue below the level of the later podia, decorate not the cult-fresco area but the eastern section; and 2) whereas the eastern part of the floor simply consisted of tamped earth, the floor of the western section of the central aisle, up to the end of the cisterns, was made of cement into which broken slabs of different types of marble had been pressed. This more elaborate treatment implies that this area, nearer to the cult fresco, had a special cultic status. The wall panels on either side at this level were empty, except for a cut-down (i.e., re-used) Eros-Psyche relief (CIMRM 186) set into the south wall below the central scuttle (Fig. 16.2a, near g).10

Figure 16.2a. Capua plan 1. Longitudinal (A-A) section of the mithraeum. The representation of the entrance corridor is at first sight misleading; the view is however taken from line a in section B-B, looking south (i.e., toward g).

Figure 16.2b. Transverse (B-B) section. The fascia walls of the Phase IIIa-b podia are marked m and l.

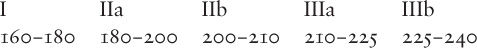

I have already mentioned that the painted decoration of the mithraeum belongs to different periods. Vermaseren ascribed one poorly preserved fresco (so faint that Minto did not see it), Panel III on the north wall (Fig. 16.2a, somewhat east of m) to Phase I; the main frescoes on the western wall (Mithras and the bull, CIMRM 181 and Fig. 16.1 here) and the east wall (Luna, CIMRM 182) to Phase IIa; the remaining panels, Cautes (north wall, CIMRM 182), Cautopates (south wall, CIMRM 183) and the feast scene (southeast corner), to Phase IIb. The podia were extended to 8.35 x 0.90 m at the beginning of IIIa, and the fascia frescoes were painted somewhat later, during Phase IIIb. Absolute dates are difficult to estimate, since the cult fresco itself has been assigned assorted dates between 160 and 200 CE. An expert commentator has indeed recently observed that “for the third century in particular the chronological fabric [of Roman painting] remains completely uncertain” (Ling 1991: 187). A decade after Vermaseren’s monograph, however, the classical archaeologist P. Meyboom, after a careful comparison between the Capua, Marino, and Barberini Mithraic frescoes, concluded that Phase IIa at Capua is to be dated 180-190 CE (Meyboom 1982). On that basis, we can construct the following scheme:

The extension and widening of the podia can thus be dated to the first quarter of IIIp. The fascias were constructed of “materiale vario” and buttressed by low transverse walls (see Fig. 16.1); the actual podia were formed by filling the spaces so created, including the cistern, the basin, and apparently the sump, with dry rubble. This infill, which fell away as usual toward the long side-walls to accommodate more diners, was then covered in plaster. During the second quarter of the third century, the fascias were inexpertly covered in poor quality, porous plaster and painted with the frescoes that are my concern here (Fig. 16.3).

Since they are the only new decoration of the temple at this period, it seems likely that the frescoes were the result of a votive undertaking, comparable to the marble revetting of the podia at the Mitreo Aldobrandini in Ostia paid for by Sex. Pompeius Maximus (AE 1924: 119 = CIMRM 233). Their date seems to group them with a number of other relatively late Mithraic images depicting mythic or ritual moments that have no earlier counterpart in the cult’s iconographic repertoire. Examples might be the highly original feast scenes on the reverse of the Fiano Romano relief (CIMRM 641) and on the terra sigillata dish from the Skt. Matthäus Roman cemetery in Trier (CIMRM 988); the interest in the details of the First Sacrifice shown by the altar of Flavius Aper in Poetovio III (CIMRM 1584); and the recently published Syrian relief now in the Israel Museum (De Jong 2000). This tendency toward “iconic discursivity” in the third century can be paralleled in other “universal” cults of the Roman Empire.

The podium frescoes consisted originally of thirteen panels, six on the right (north) fascia, and seven on the left (south; Fig. 16.3). Just seven can still be deciphered to some extent, four on the right fascia and three on the left; but even in these cases, both the reading order and the precise events depicted are unclear. It is, of course, a truism that the apparently simple act of describing neutrally “what one sees” turns out to be conditioned, often to a crippling degree, by a priori assumptions. Minto, who had discussed the frescoes with Cumont in some detail (Cumont 1924), thought that the reading order proceeded up the right-hand podium starting nearest to the eastern wall (here RI → RVI) and continued back down the left (southern) podium (LVII → LI).11 What sense such an order might have made, Minto does not say; but he evidently believed that the sequence represented the initiations for all seven initiatory grades, acting as a sort of anticipatory program: “I fedeli, contemplando queste scene liturgiche, dovevano provare la suggestione di tutta la loro vita religiosa, attraverso i diversi gradi di iniziazione” (Minto 1924: 373). He had evidently not worked this hypothesis out very carefully, since it is quite unclear how thirteen panels could have represented initiations into seven grades.

Figure 16.3. Schematic representation of the arrangement of the scenes on the podium frescoes. The right side represents those on the North podium, the left those on the south.

Vermaseren, on the other hand, concluded that the reading order on both podia was from east to west (i.e., RI → RVI, then LI → LVII). In his view, the panel scenes depict a more or less complete sequence of initiation rituals, all undergone by a neophyte, or would-be Corax, in which members of different grades, such as Miles and Nymphus, act as initiators (Vermaseren 1971: 49). Although he claims to believe that these representations have little or no relation to any initiation rituals reported by literary sources, in practice he constantly attempts to interpret the panels in the light of these texts. Since my concern here is less with their supposed documentary value than with their treatment of the body and its implications for the “truth” conveyed by the cult of Mithras to its adherents, I can lay these questions of reference and reading order to one side. For what it is worth, however, my opinion is that initiatory tests were not standardized between temples, and that each Mithraic community devised its own forms of initiation with reference to certain “sacralized moments” in the myth of Mithras, in particular the “Initiation of Helios/Sol” scene that occurs on complex reliefs, where Mithras seems often to be threatening or intimidating the sun god.12 There was thus a mere family resemblance between the initiation rituals of one mithraeum and those of the next, and there is therefore no reason to attempt to force the texts onto the iconography. In the immediate case of Capua, I cannot agree with Vermaseren that the scenes all relate to the initiation of a single grade. No coherent sequence of events can be made out, and at least panels RII and LIII seem to be very similar kinds of tests, in that both involve fire. There is therefore no practical alternative but to approach them from the spectator’s point of view, as a group, and to try to make out an overall or general claim about the implied role of the body. The meaning of the panels to the donor and to the Capuan Mithraists of c. 230 CE cannot now be recovered.

I first offer a brief description of each of the seven surviving panels, arbitrarily following Vermaseren’s order and placing Minto’s images alongside what are frankly interpretative tracings of the figures still visible in Solazzi’s plates published by Vermaseren. In general, since the panels were in much better condition in 1924, Minto’s accounts, though very brief, are preferable to Vermaseren’s. All the panels, which range in width from 0.63 m (LV) to 1.63 m (LIII) but are mostly around 1 m wide, are enclosed within a red-stripe border (there are no inner frames); the scenes occupy roughly the center of each panel. They thus fall clearly into the tradition of tabulae pictae in the post-Severan linear style, familiar from several examples in Rome, and Christian catacombs in particular, where the central motif is isolated within its frame—the only hint of an environment is offered by the indication of ground—and body contours, rather than the volumes or spatial relationships, are emphasized (Ling 1991: 188-191). To avoid having to be too precise about the identity of the initiating persons, I term the main initiator, sometimes called Pater by Vermaseren, the “teletarch,” his assistant the “mystagogue.” This does not imply that I think that all the figures represent the same status or individual.

RIGHT-HAND PODIUM

RI (Fig. 16.4a-b).13

This panel depicts just two persons.14 A small naked figure, blindfolded, with his hands stretched out apprehensively, walks to the left. Behind him, to his left, is a much larger figure, dressed like the mystagogues in the remaining panels, in a short white tunic reminiscent, except perhaps for its color, of those worn by ordinary workers or slaves in Alltagsszenen.15 He appears to be guiding the initiand forward by placing his left arm on his shoulder. This is the only scene that appears to have a clearly introductory, and therefore quasi-narrative, role.

The initiand, again naked and blindfolded, is half-kneeling on his right knee, with his hands bound behind his back. The editors rightly see an allusion—probably condensed—to the posture of captured prisoners.17 Behind him, a bearded mystagogue, dressed in the same fashion as in RI,18 and with his left hand at his waist, seems with his right hand to be pushing the initiand’s head forward, or at any rate preventing it from jerking back. The mystagogue’s left leg is demonstratively far back, as though to resist pressure: this stance is emphasized by the lengthy ground/shadow line. Facing the initiand stands a likewise bearded, thus fully adult, man apparently wearing a helmet, and dressed in a dark tunic and a cloak, which billows out behind him. In his left hand, he is holding a lighted torch in the initiand’s face; the billowing cloak is evidently intended to suggest the threatening nature of the movement, just as the mystagogue’s stance is intended to suggest the initiand’s instinctive recoil.19

The initiand stands naked in the center, his hands apparently bound behind his back, held resolutely by the mystagogue, whose body is hunched forward. The teletarch, on the left, dressed in tunic, trousers, and cloak, faces the initiand, evidently again to induce fear and pain. Although the entire central area, including the teletarch’s head, has been damaged (perhaps even in antiquity), he is most probably again being threatened—here the initiand’s eyes are not bandaged, so that he could see what was happening. Vermaseren’s account of this scene (he apparently thought the initiand was holding a sword, and was being embraced by the mystagogue) is bizarre.

Figure 16.4a. In Figures 16.4-16.10, each figure is doubled into a and b: a is the image provided by Minto in the 1920s, and b is Gordon’s drawing from Vermaseren. This image: Minto 2.

Figure 16.4b. R1.

Figure 16.5a. Minto 3.

Figure 16.5b. R2 revised.

RV (Fig. 16.7a-b).21

In the center, the initiand half-kneels on his right knee. Although Vermaseren claims the initiand’s arms are resting on his thighs, Minto correctly saw that they are bound behind him.22 He also believed that the mystagogue, again standing behind the initiand, is extending a crown over the initiate’s head. In his view, this was a reference to a victory, apparently over fear.23 Minto, on the other hand, writing half a century earlier, saw no crown, and reckoned that this scene should be linked to LIV and III, in each of which the initiand is kneeling between teletarch and mystagogue. I incline to think he was right, and that the object being held over the initiand’s head here is the same as, or related to, the round object on the ground in LIV, with the crux of the scene to be found in the now-lost action of the teletarch. Vermaseren’s view was heavily influenced both by Tertullian—although he finally rejected his relevance here—and by his notion that there was a status progression toward the cult niche, so that at some point there had to be some sort of reward for the initiand.

Figure 16.6a. Minto 5.

Figure 16.6b. R4.

Figure 16.7a. Minto 4.

Figure 16.7b. R5.

Whereas in scenes RII, IV, and V, the teletarch stands on the left of the scene, in the corresponding panels on the southern podium he seems always to be on the right; that is, it appears to be an implicit rule of the sequence, for whatever reason, that the initiand should face the central aisle or passage.

The upper part of the panel is destroyed. In the center, a naked initiand, his body expressionistically elongated, lies prostrate on the ground, or possibly on some kind of raised construction, since the feet of the principals extend much further down the panel; that would account for the “objects” below him, especially at the foot and hand.25 Several indecipherable objects are arranged above him. Among them, on the small of his back, Vermaseren was surely right to see a scorpion (identified by Minto as a snake), its tail raised in a threatening manner as though about to sting. What the mystagogue, on the left, is doing cannot be made out (Vermaseren thought he was dropping something onto the initiand’s feet). The teletarch, of whom now almost nothing remains, though Minto could see much more, seems once again to be threatening the initiand. Whether the latter’s head was raised, as Vermaseren thought, or the blob belongs to the object held by the teletarch, can no longer be determined: Minto, at any rate, does not mention it.

Figure 16.8a. Minto 8.

Figure 16.8b. L2.

Figure 16.9a. Minto 6.

Figure 16.9b. L3.

Almost nothing of this panel can now be deciphered. The initiand is kneeling in the center, on both knees; the mystagogue, one leg stretched far back, and grasping his shoulders, seems to be pushing him forward with considerable violence. To the right, the teletarch, wearing a helmet (Vermaseren) or Phrygian cap (Minto) and a fluttering cloak, implying rapid movement, holds a lighted torch below the initiand’s arms or hands. Vermaseren is mysteriously reminded of the claim by Porphyry (Antr. 15) that initiands into the grade Leo had their hands purified with honey instead of water, because it is a fiery liquid.

LIV (Fig. 16.10a-b).27

In a scene very similar to LIII, but especially in 1924 better preserved, the initiand, again on both knees, has his arms crossed over his breast (Vermaseren) or being held behind his head(?). The mystagogue, in white tunic and with his legs straddled, again grips the initiand from behind. The teletarch, head lost but otherwise in the same garb as in LIII, holds a staff, sword, whip, or similar object in his right hand. To the left of the initi and is a round object, identified by Vermaseren and Merkelbach as a loaf; Vermaseren even believed that the teletarch was placing it there with his right hand, and so turned the scene into an allusion to the divine/human banquet. In fact, there are two objects, one roughly circular, divided by seven centripetal lines into eight sections, beneath which is a blob of red paint. The first object bears no resemblance to loaves depicted elsewhere in the Mithraic corpus, or in still-lives, so there is no reason, compelling or otherwise, to accept Vermaseren’s account. As mentioned earlier, I incline to think it is related to the object being held over the initiand’s head in RV, perhaps in an allusion to Mithras Kosmophoros, Mithras-Atlas in his role as world-carrier.

Considered as documents in the ordinary sense, then, fragmentary and bereft of all ancient commentary as they are, the panels from the podia at Capua are deeply frustrating. We may, however, suggest that the basic error of previous commentators has lain precisely in the attempt to force them to “say the same” as the equally fragmented and problematic literary texts, mainly Christian and thus deeply suspect, which claim to speak for the cult of Mithras. For it must be obvious that the panels do not “depict” rituals in any direct or uncomplicated sense. They represent idealized, constructed allusions to rituals, allusions that could be claimed to have some special significance either for the donor or for the larger community of the mithraeum around 230 CE. As such, their greatest value may lie not in their supposed (but ever hypothetical or “deferred”) documentary character, but in their revelation of a structure of oppositions, which we may plausibly claim to be the basic structural elements of the rituals actually performed, whatever they were.

Oppositions at any rate there certainly are. We can point first to the contrast between the sizes of the participants: although the initiand is consistently presented at the center of the spectator’s attention (to which we shall return), he is always the smallest figure present, smaller than the mystagogue, and much smaller than the teletarch.28 His size thus correlates with his prescriptive insignificance, and confirms, if further proof were needed, the nondocumentary quality of the scenes.29 Second, the nakedness of the initiand is stressed by the tone of brick red or brown used, contrasting with the white of the mystagogues and the imposing appearance of the teletarch, enhanced by his billowing cloak and his military helmet (if that is what his headgear is). Nakedness outside sporting or athletic contexts implies absence or negation of social status, most markedly when it is deliberately contrasted, as here, with the wearing of clothes.30 Then again, where the detail can be seen, the officiants are bearded, the initiand beardless, thus signalling the prescriptive contrast between maturity/membership and youth/initiation. Even more important in the present context are the contrasts between the body postures: between prostration, two types of kneeling, being pushed, constrained, and tied; and vigorous, dominating actions. These contrasts of posture/ autonomy are reinforced by the fact that the initiand is, at least in some panels, blindfolded, alluding to the key contrast between knowledge and ignorance. All of these oppositions can be summarized in the grand contrast between agency and submission, between the free, purposive action of an agent and the enforced reaction of a subject. The Mithraic schéma corporel is dual and hierarchical, such that the scheme of autonomous action can only be acquired through the scheme of subjection (cf. Bourdieu 1979: 210-211).

Figure 16.10a. Minto 7.

Figure 16.10b. L4.

Given that they are so clearly focused on the suffering body of the initiand, it seems plausible to look in the first place to Michel Foucault to help us contextualize the Capuan images. The Foucauldian body is a socially appropriate body, the product of historically specific discourses and practices, an “anatomical body overlaid by culture.”31 Initially, in his work on social discipline (1975), Foucault’s perspective emphasized solely the relation between the materiality of the body and its discursive regulation in theory and practice. On his account, concentrated on the nineteenth century but with ample reference back to earlier monastic, military, and penal practice, the body is molded, trained, and pressed by a variety of techniques into becoming a socially useful instrument (1975: 30-31). “The phenomenon of the social body is the effect not of a consensus but of the materiality of power operating on the very bodies of individuals.”32 By way of the notion of “bio-power,” the subject was not only redescribed in materialist terms but also shown to be historically contingent. With the publication of the three volumes of L’histoire de la sexualité (1976-84), however, Foucault’s social body became primarily a gendered body, a sexually differentiated body.33 Leaving this to one side for the moment, I want first to explore aspects of the Mithraic body with reference to Foucault’s earlier distinction between a type of social order based upon “le modèle représentatif, scénique, signifiant, public, collectif” and one based on “le modèle coercitif, corporel, solitaire, secret, du pouvoir de punir” (Foucault 1975: 134).

Foucault’s aim in Surveiller et punir was to write a genealogy of the modern “scientific-judicial complex,” which turns individuals into objects of a particular form of discursive knowledge. For heuristic purposes, he contrasted this complex with an early-modern world in which high rates of mortality and the absence of an industrial regime produced a “worthless” body, which was at the same time of the greatest symbolic interest. The socio-political value of this pre-industrial body lay in its ability concretely to manifest the dis-symmetry between the power of the state and that of the individual (1975: 59). So far from concealing its repressive work, Power gloried in its right to inscribe itself in the most gruesome fashion upon the body. Conversely, an audience was indispensable. For— in a sense — it is the spectator, not the culprit, who is the primary actor in exemplary punishment. Without spectators, the spectacle lacks all moral sense. In the specific cases of corporal and capital punishment, there are three criteria of successful ritualization: the quantum of suffering must be appropriate to the crime; the suffering must be signalled to the audience in such a fashion that it be never forgotten; and the “excess” of violence must be intelligible as the writing of power (1975: 37-39). The effect of such punishment was to expose the crime, itself unspoken or hidden, by means of rituals of humiliation and suffering. Among the rituals are the nicely regulated procedures of torture, which, like Kafka’s “eigentümlicher Apparat” in In der Strafkolonie (1914), simultaneously punished as they revealed the truth (1975: 46). The “corps montré, promené, exposé, supplicié” is not intended to re-establish a moral equilibrium but destined symbolically to affirm the superiority of constituted authority. “Le supplice ne rétablissait pas la justice; il réactivait le pouvoir” (1975: 53).

Distantly in the wake of Foucault (and Norbert Elias), ancient historians have explored the symbolic functions of violent spectacle in antiquity, both in the “théâtre de terreur”34 and in the history of gladiatorial combat.35 Among these, Kathleen Coleman especially has shown how strikingly the Roman principate confirms Foucault’s account of the symbolic value of the body in pre-industrial state repression.36 Indeed, the explicitness, inventiveness, memorability, and expense of Roman ceremonies of degradation, the apparently unlimited ability of the judicial system to produce “worthless bodies” (in Latin: vilis sanguis), the centrality of the spectators’ consent and desire (Occide! Verbera! Ure!: “Kill him, thrash him, burn him!” Seneca Ep. mor. 7.5), and the enthusiastic occlusion of justice for the sake of reinvigorating Power—all these serve to make the Principate the example Foucault must have wished he had thought of.

Placed in this context, the Mithraic initiation rituals depicted in the Capua Mithraeum are extremely suggestive. Although they of course have no connection with the apparatus of state power, their images of subjection, degradation, and suffering imply an imaginaire based on the same premises as the théâtre de terreur, namely, the exemplary production of vilis sanguis, the ingenious multiplication of forms of humiliation, the use of physical suffering to underwrite the triumph of Power, and a heightened interest in the reactions of the implied spectator. One remembers that Capua boasted the second largest amphitheater in the entire Roman world, built in the late Flavian/Trajanic period over the Republican amphitheater where Spartacus had trained, and was the center of an important gladiatorial training-school, commemorated by the Museo dei Gladiatori recently installed in the Antiquario dell’Anfiteatro dell’antica Capua.37 Of course, these Mithraic depictions are of voluntary sufferings and humiliations, of performances rather than of tortures, of roles assumed and played out. But we cannot deny the evidence that the performances were not “mere” playacting: they were accompanied by the intentional infliction of pain, to say nothing of terror and humiliation. The burning torch pushed into the face of the initiand in RII, the apparent singeing of the man’s arms in LIII, and above all, the scorpion placed on the bare back of the man in LII make this evident. The element of role-playing does not in fact constitute a decisive difference from the real théâtre de terreur. Rather, the Mithraic teletarchs and mystagogues see in that real-world violence a symbolism perfectly appropriate to their own ends, the production of a Mithraic body “fit for the job.”38

We may legitimately conclude that the primary intention of the degradation of the Mithraic body, as depicted on the podia, is to image, both to the subjects and to the spectator, the superiority of constituted Power, the legitimacy of authority, and the mystic connection between hierarchy and salvation. If we compare the gallus, for example, the role of Power becomes clear: in imitation of Attis, the gallus inflicts upon himself, at least in the ideal-prescriptive narrative, a wound that, if he survives the act, separates him from all normal familial-social aims and obligations; the loss of blood correlates with the loss of manhood, the loss of manhood signifies an existence solely for the Mother. The act marginalizes the network of social obligations and dues that constitutes social life, but remains itself as exceptional as Christian martyrdom. In the cult of Mithras by the mid-third century CE, if we can generalize at all from Capua, the initiate was induced to believe that he could only attain self-identification with Mithras by accepting the right of beneficent Authority to inflict pain and terror for his own good, not once but repeatedly. Whether this was understood in the manner of Musonius Rufus and popular Stoicism as an acquisition of ataraxia and apathēia (Francis 1995: 1-52), or more stringently as a rejection of sin, as Porphyry’s account of the Lion’s purification with honey would suggest, constituted Authority is perceived as controlling the sole road to the higher end. The salvific claim of Power is inscribed on the mind via suffering flesh. In the course of that inscription, both subject and spectator rehearse the mythic “suffering” of Mithras and intuit the grand saving Otherness of the Lord of the Cosmos.

The experience of initiation, and indirectly of viewing these scenes, conveys, I suggest, an intuitive perception of a complex truth. On the one hand, the experience and contemplation of physical suffering offers the sole effective means of subjective self-identification with the Mithras of the bull-killing, who seems at S. Prisca to declare, perlata humeris t[ul]i maxima divum, “I have borne the commands of the gods on my shoulders right to the end”.39 ) On the other hand, that same physical suffering marks an irreducible ontological distinction between mortal and divinity. If Mithras can step into the Chariot of the Sun, humans cannot, suffer how they will. All that remains ultimately is the mystical association, which cannot be articulated because it endures only in the body itself, between Power and salvation.40

At the same time, the gender issue will not go away. The exclusion of the female in these images is all too striking: we are everywhere confronted, in this private, sacred space, by the painterly convention of the bronzed masculine body. Although maleness is in the Mithraic context paradigmatic, this is not the maleness of the elite demand to enter the “marketplaces and council halls and law courts and gatherings and meetings” (Philo De specialibus legibus 3.31,169).41 Yet the body with which the spectator is invited to identify is in a sense a feminized body, a subject acted upon, suffering, rather than agent, active. The key must, however, be the role of the passions: the feminization is incomplete precisely because the infliction of pain and suffering issues not in still more passion but in the opposite, in their rejection. The Capuan images of initiation suggest the attraction for some men in the mid-third century CE of an image of the pure circulation of Power, from domination to submission back to domination, in which women could play no part. Such pure circulation surely offered a means of overcoming the “ambiguity and division of gender.”42

It may, however, also be that we should look more specifically at wider developments in the mid-third century CE for our contextualization of the Capuan images. A few years ago, Brent Shaw brought together a number of themes relevant to the issue of the Christian glorification of bodily suffering and torture (Shaw 1996). He saw this glorification as an inversion of the classical attitude, which, he claims, saw submission as effeminate or cowardly. Perhaps it would be more accurate to claim that the martyrs’ exaltation of death would have struck Aristotle, for example, as hybristic, because their suffering is offset by the expectation of future glory (Rhet. 2.8.1385b16-23). The ordinary classical view was that death, bodily injury, and mutilation must excite our compassion (éleos) (1386a5-16). At any rate, tracing a line from 4 Maccabees to Cyprian’s De bono patientiae of the mid-third century,43 Shaw argues that hypomonē, “endurance,” which had been a female merit or virtue connected with the pains of childbirth, becomes central to an ideology of meritorious suffering, such that the victim of torture can claim the same merit as that traditionally associated with the active heroism of andreía, “manliness.” At latest by around 200 CE, when Tertullian’s De patientia was written, this virtue is of supreme importance in Christianity, for through it one becomes master of one’s body: the control of food intake and sexual appetite leads up to a readiness to endure the worst pains in the cause of martyrdom. The ability to resist suffering and torture thus becomes an important feature in Christian self-definition. Consistent with this exaltation of endurance is St. Paul’s transformation of the negative word tapeinós, “mean, low, wretched, subordinate,” into the ideal of meritorious self-abasement, tapeinosophrýnē, “humility” (Ephesians 4.2).

Although all this can properly be seen as a shift prompted by necessity, as a response to the objective situation of Christians exposed to arbitrary suffering, there are traces of a similar move in a pagan context. Seneca, for example, discusses endurance primarily within the context of bodily illness and public torture in the arena.44 But for him, the lesson to be drawn is to learn to avoid situations that might expose us to such dangers: since he has no promise of eternal life, the path of glorification is not open to him. Moreover, he is at pains to distinguish a less meritorious passive endurance from an active one: gladiators and athletes endure pain not simply to fight but to fight better; and the ideal of resistance to torture is not mere passivity but the reduction of the torturers to helplessness. Seneca thus avoids the paradoxicality of the Christian view and maintains a form of active manliness within the passive or “feminized” virtue of endurance. We might suggest that something of this kind is implied at Capua: the initiand must endure pain, humiliation, and confusion, but in a context in which this suffering is rendered purposive and therefore, in a sense, active. The model is anyway Mithras, whose endurance of the bull hunt was rewarded by the fulfillment of his cosmic role in doing it to death.

That said, two other features of the Capua frescoes are of interest in suggesting the double nature of the torments applied. One is the role of fire. As we saw, two of the scenes seem to involve torches — in RII, having a burning torch thrust into one’s face; in LIII, having to endure having one’s arms burned from below. Fire occurs regularly in lists of tortures and sufferings, in the arena and elsewhere: it is second in Seneca’s list in Ep. mor. 14.4 (ferrum circa se habet, et ignes, et catenas …), and third in Achilles Tatius’ Cleitophon and Leucippe, when Leukippe dares Thersander to do his worst: “Bring out against me the scourges, the wheel, the fire, the sword.”45 Fire is thus a “cliché of torment.” At the same time, the torch resonates widely within the symbolism of the cult of Mithras, emblematic of the opposition between light and darkness. The torch is thus not simply a torch.

Secondly, we recall the man lying prone in LII. My first thought was that this must have evoked the idea of the male pathic, who “acts like a woman” in suffering the penetration of his body by another man: one of the key verbs in this connection is inclinor, “lie prone.” But the recognition of the scorpion sitting on his back makes clear that the sexual connotation of “lying prone” must be secondary to that of being exposed defenseless to the scorpion’s sting, or the threat of its attack. Scorpions were reputed to be ever on the lookout for the opportunity to sting.46 At the same time, in the Mithraic context, not only does it allude to the bull’s death, at which the scorpion stings its scrotum, but also a special relationship to the sun, since scorpions’ venom was at its most poisonous at midday (Pliny NH 11.88).

I would suggest, then, that the larger context of the Capuan frescoes may be an awareness of the role of patientia in sustaining the readiness of Christians, not merely male but also female, to accept martyrdom. From the initiation scene of the Mainz Schlangengef,äß where a Father is threatening to shoot an initiand with a bow and arrow, we may conclude that some kind of initiatory suffering had probably always been a feature of the cult of Mithras, just as it has been in other initiatory cults.47 Jan Bremmer has recently stressed that we should not see the pagan cults of the second and third centuries CE in isolation from Christianity (Bremmer 2002: 4155). Although the examples he gives do not seem to me very convincing, particularly as regards Mithras, the thought perhaps should not be dismissed entirely. For Christian patientia, as experienced in the intermittent éclats prior to the Decian persecution, may indeed have stimulated among contemporary Mithraists a desire to explore in ritual a specifically male, active endurance of suffering, thus offering a “conservative” answer to the imaginative impact of the public suffering of Christian martyrs. Picking up a term from the pseudepigraphic Jewish Testament of Job, we might call such a response to the Christian challenge Mithraic makrothymía (17.7).

As far as their specific content is concerned, the podium frescoes of the Capua Mithraeum are likely always to remain enigmatic, virtually uninterpretable. That is why, for all their evident importance as documents, they have effectively fallen out of discussions of Mithraic ritual/initiation. For what they mainly demonstrate is the disagreeable truth that iconographic studies in the absence of written texts cannot take us very far. However, by studying their structure of oppositions and linking them to wider issues—namely, the relation between ritual action and the State theater of cruelty, and the emergence of heroic-passive values in early Christianity, and even Seneca—we may find a way of recuperating them just as the frescoes themselves deteriorate physically beyond all hope of restoration.

1. The ancient body: e.g., Heuzé 1985; Sissa 1987; Konstan and Nussbaum 1990; Gleason 1995; Wyke 1998a, 1998b; Foxhall and Salmon 1998; Shaw 1998; Cooper 1999; Williams 1999; Scanlon 2002. I offered a rather different account of the topic to the conference “Divinas Dependencias” (1998); see now Gordon 2005a.

2. Kirtsoglou 2004: 16. A different approach to this issue, through the notion of “star-talk,” will be found in Beck 2006.

3. An unreliable tradition of extreme tests of endurance imposed upon Mithraic initiates is preserved in the sixth-century commentaries on Gregory of Nazianzus by Ps.-Nonnus, Comm. in Greg. Naz. Serm. 4.70, §6; 47; Serm. 39 §18 (see now most conveniently Nimmo Smith 2001: 7, 34-35, 104-105). The details—up to 80 tests, fasting for 50 days, “passing through fire, through cold, through hunger and thirst, through much journeying by land and sea” — are hyperbolic, but the Capuan paintings suggest there is a grain of truth within them. Marius Maximus is the likely source of another tradition, that the emperor Commodus killed someone during a Mithraic initiation cum illic aliquid ad speciem timoris vel dici vel fingi soleat (Hist. Aug., Commod. 9; cf. Rives 1995: 72 n. 37). The anecdote fits well with Maximus’ love of lurid gossip. Ad speciem timoris would, however, likewise fit well with the Capuan paintings.

4. However, Merkelbach does provide clear black-and-white plates of five of the scenes (1984: 287-290, figs. 28-32). These are the same images as those reproduced in Vermaseren’s Corpus (1956-60: figs. 57-61, hereafter cited as CIMRM ), albeit in a whimsical order.

5. Almost the sole analogy among the images collected in Bianchi 1976a is the well-known whipping-scene in the Villa of the Mysteries, Pompeii. Fear, even terror, by contrast seems to have been commonly employed in the Greek mysteries.

6. The decay is due partly to the poor quality of the original plaster, partly to the absorption of moisture from the tamped earth floor (Minto 1924: 367).

7. Although his color plates are of great value, Vermaseren was no archaeologist, and his publication, despite being fuller than Minto’s, is unfortunately poorly organized, and confused or uninformative on many archaeological questions.

8. All these internal dimensions are taken from Minto (1924: 356). For some reason, Vermaseren gives the external dimensions, and by a slip gives the width of the mithraeum as 3.37 m (1971: 3).

9. This sump was also connected to the masonry altar (Fig. 16.2a and b, at i) by a concealed channel. In addition, there was a well behind wall b (Fig. 16.2b, at c), equipped with footholds for descent. The cistern on the southern (left) side was 1.28 m long by 0.67 m wide; the dimensions of the basin and sump (right) could not be determined for fear of causing the collapse of the walls of podia h and l at this point (Minto 1924: 357 with fig. 4). Vermaseren seems wrongly to have believed that the cistern and basin continued to function as such after the construction of the podia (1971: 5). They did not: Minto found them full of the rubble used to infill the podia (1924: 358).

10. Vermaseren believed (1971: 50 n. 1) that the relief was inserted during Phase I, which seems very unlikely.

11. Minto 1924: 368-372. Unfortunately, he confused the order of the scenes on the left podium: as is clear from the draughtsman’s Roman numerals, the order should be his figs. 15, 14, 16. He also fails to mention his own Scene VIII (= Vermaseren 1971: LIII).

12. Cf. Clauss 2000: 149-151; Turcan 2000: 98. Merkelbach (1984: 123-124) presents some examples, although his interpretation is eccentric.

13. Minto 1924: 368, scene I, fig. 10 = CIMRM 187 = Vermaseren 1971: 26-27 with pl. xxi = Merkelbach 1984: 287, fig. 28.

14. This is no doubt why Merkelbach (1984: 287, fig. 29), wanting to make it congruent with the others, claims that a Pater (or at any rate a “teletarch”) was depicted to the left. Neither Minto nor Vermaseren mentions the fact. There is indeed a blob in front of the initiand, which on a black-and-white photo might be a clenched hand; but the color photo shows that it is simply a hole in the plaster. As so often, Merkelbach’s claims are to be taken with a large pinch of salt; and anyway, there were probably only two persons depicted in RIII (unrecoverable).

15. Vermaseren oddly claims that this figure is the Pater, when it quite clearly is not (1971: 27, inconsistent with his p. 26). The identity of the raised object on his head is uncertain. It is most likely an illusion due to damage to the plaster: all the other mystagogues have bare heads.

16. Minto 1924: 369, scene II, fig. 11 = CIMRM 188 = Vermaseren 1971: 28-34 with pl. xxii = Merkelbach 1984: 288, fig. 30.

17. Minto 1924: 369; Vermaseren 1971: 29-30.

18. Vermaseren and Merkelbach introduce fantasies here, the first claiming that the mystagogue is wearing a cape over his tunic “bordered with red” (1971: 28), the second improving on this by claiming that the tunic itself carries a clavis (a red-purple stripe), that is, alludes to the toga praetexta of curule magistrates (1984: 288, fig. 30). These lines are simply the outlines of the man’s clothes, intended to provide visual help in identifying his action. The strong outline at the extreme right, however, is also intended to reinforce the sense of forward movement or pressure.

19. The horizontal line running across his body, through his hand and toward the initiand’s face, is certainly the result of damage, and does not indicate that the teletarch is holding a spear, as Merkelbach claims (ibid.), and as even the color photo suggests. Minto thought the object he is holding was a sword (1924: 369), which makes no sense if the initiand is blindfolded. Vermaseren must be right to think it is a torch.

20. Minto 1924: 369, scene III, fig. 12 = CIMRM 190 = Vermaseren 1971: 34-36 with pl. xxiii. Minto despaired of making sense of this panel; Merkelbach ignores it completely. Panel RIII (= Vermaseren 1971: 34; see note 14 above) seems to have represented a man walking left; some blobs of paint in front of him indicate that there was another person (ibid.: 34); Minto mentions panels III and IV together, but describes only RIV.

21. Minto 1924: 370, scene V, fig. 13 = CIMRM 191 = Vermaseren 1971: 36-42 with pl. xxv = Merkelbach 1984: 297, fig. 28 (part only), also pp. 95-96 and 136.

22. Vermaseren likewise wrongly claims that the initiand has a beard. The supposed “sword” on the ground below him is simply a ground-line.

23. Vermaseren did, however, rightly understand that this scene is irreconcilable with the account of the initiation of a Mithraic “miles” given by Tertullian (De cor. 15). Merkelbach, on the other hand, blithely sees them as compatible.

24. Minto 1924: 371-372, scene IX, fig. 16 (on p. 374) = CIMRM 193 = Vermaseren 1971: 43-44 with pl. xxvi = Merkelbach 1984: 289 fig. 31.

25. Merkelbach cites [Ambrosiaster] Quaestiones veteris et novi testamenti 93.1 here, a passage referring to the Mithraic initiand being pushed across a water-filled ditch and having his bonds, made of chicken guts, cut by his “liberator.” This, too, is likely to be pure fantasy.

26. Minto 1924: 370, scene VIII, fig. 14 (on p. 372) = CIMRM 195 = Vermaseren 1971: 44-45 with pl. xxvii.

27. Minto 1924: 370, scene VII, fig. 15 (on p. 373) = CIMRM 194 = Vermaseren 1971: 45-47 with pl. xxviii = Merkelbach 1984: 290 fig. 32 and p. 137.

28. The one exception is LII, where, if the initiand were standing, he would be about 1.5 times taller than the mystagogue. But his complete subjection and humiliation can be more effectively expressed the further he extends over the ground or couch.

29. Bourdieu mentions the findings of W. D. Dannemeier and F. J. Tumin in 1964, according to which subjects tended to overestimate the size of individuals in keeping with their subjective estimate of their authority or importance (Bourdieu 1979: 229 with n. 28).

30. Cf. Brown 1988: 96 n. 54. Müller (1997: 87) notes that in the medieval period, disrobing the person to be punished was part of the humiliation. Older views of specifically religious nakedness (e.g., Heckenbach 1911) are generally naive.

31. Gatens 1999: 229.

32. Gordon 1980: 55. I do not of course wish to endorse Foucault’s characteristic reification of abstractions, which subsequently turn out to be the real agents of history (cf. Giddens 1982: 221-222).

33. Cf., for example, Ortner and Whitehead 1981; Butler 1993; Price and Shildrick 1999; Davis-Sulikowski et al. 2001; Kirtsoglou 2004.

34. Du châtiment dans la Cité 1984; MacMullen 1986; Bodel 1994; Cantarella 1991; Hinard and Dumont 2003.

35. For example, Ville 1981; Hopkins 1983: 1-30; Golvin and Landes 1990; Domergue, Landes, and Pailler 1990; Welch 1994; Kyle 1998; Beacham 1999; Junkelmann 2000; Von den Hoff 2004.

36. Coleman 1990; cf. 1993.

37. The museum, largely inspired by Dssa Valeria Sampaolo, contains some material from the amphitheater, more, however, from that at Pompeii. The epigraphic materials are collected in Fora 1996.

38. “C’est-à-dire le schéma corporel en tant qu’il est dépositaire de toute une vision du monde social, de toute une philosophie de la personne et du corps propre”: Bourdieu 1979: 240.

39. Vermaseren and van Essen 1965: 204-205. (Line 9, lower layer, left wall, c. 210 CE.) Vermaseren reads t(u)li, but the l is imaginary. Forgetting that the -a of perlata must be elided in the scansion, he claims that this is the sole pentameter line, which is also very implausible. A proper metrical hexameter, comparable to most of the other lines, could be produced by assuming a short word of three long syllables here, such as t[radux]i. But difficulties abound: it is not even certain that it is a first-person utterance; and in Vermaseren’s drawing (p. 203, fig. 67), the word is impossibly short, yet with a long gap between the i and m of maxima.

40. See the suggestive remarks of Müller 1997: 90, on the role of the broken body of Christ in medieval Passion plays.

41. Cited by Lieu 2004: 182.

42. Ibid.: 190.

43. Shaw seems to think 4 Maccabees is Hellenistic, but it can in fact be dated between c. 18 and 55 CE.

44. Esp. Seneca Ep. mor. 14.4-6.

45. Achilles Tatius Cleitophon and Leucippe 6.22.4, resuming her more rhetorical outburst at 21.1.

46. Cf. elatae metuendus acumine caudae / Scorpios ….: Ovid Fasti. 4.163-164; semper cauda in ictu est: Pliny NH 11.86-87.

47. The Mainz Schlangengefäß: Horn 1994: 23, with pls. 7, 14-16; Beck 2000b: 149-154, with pl. XIII. Others: as Burkert (1987: 102) rightly says, “From Australian aborigines to American universities.” A good example of the patterned use of initiatory whipping in New Guinea is provided by Barth 1975: 57 (twice), 65.