How did painters—and users — of Greek vases in the seventh and sixth centuries BCE view Dionysus? It was this question to which I intended to respond in a new history of the images of Dionysus and his followers up to the years before 500 BCE.1 This history had to be reconstructed in the most objective and systematic way possible, by searching in the meanwhile to overcome the preconceptions of Dionysus that we all have inherited from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.2 Given that in the period under investigation, Greek ceramics can be dated with sufficient precision, it would not seem too hazardous to establish a connection between the history of the images and the history of religions.

It is necessary to say forthwith that the Dionysus theme is, numerically, the most important of the vase inventory. This is not surprising if it is considered that the Greek figured pottery is functionally linked to the symposium—certainly not a daily event but relatively widespread and frequent in the ancient world. In this mass of representations, the evidence of mythological deeds involving the participation of Dionysus, such as the wedding of Thetis and Peleus, the return of Hephaestus, the Gigantomachia, and the birth of Athena, are relatively few. Much more consistent are iconographic themes that cannot be attributed in an unambiguous way to the mythical sphere, but that would seem rather to refer to that of ritual: the meeting of Dionysus with a matron figure, the dance of grotesque characters and of satyrs with or without Dionysus, and the rider of the mule. Every one of these subjects constitutes its own iconographic line whose sequence can illuminate the history of the cult of Dionysus.

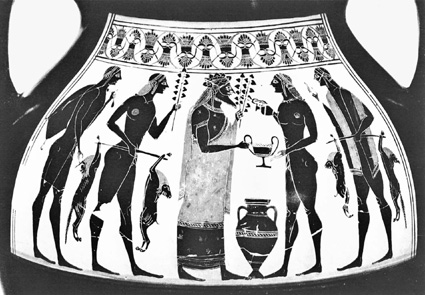

In the seventh century, the decorative inventory of pottery is dominated in all of Greece by the animal frieze. The few mythological images are found on vases of defined categories, as, for example, on the monumental Cycladic craters (the so-called Melian amphorae) or on Protoattic pottery. But already in this phase—an important observation also for the history of religion—we meet the first images of Dionysus and of the Dionysiac world: the god facing a bride,3 the figure of a savage satyr attacking a female figure,4 and above all—not only in Attica — the grotesque dancers whose only attribute, when it exists, is the drinking horn, and whose dance is displayed around a crater.5

In the first quarter of the sixth century, the general panorama of ceramic representations changes conspicuously with the introduction of new shapes, often in lesser dimension, and with an increase in the quantity of production. This innovation can be put in the context—at least at Athens, where ceramic production is particularly conspicuous—of the new political order attributed to Solon. A notable increase in the citizenry, and thus in the custom of symposia, appears to be related to this new order.6 In this phase, again dominated by animal friezes, the Dionysiac theme remains preeminently that of the grotesque dancer found especially on Corinthian perfume vases, Attic symposium cups, and ritual vessels used in Boeotia.7 There are also examples of satyrs attacking nymphs8 and of the mule-rider, possibly identifiable with Hephaestus.9

Near or shortly after 580 BCE, we have the first reliable representation of Dionysus on some luxurious dinoi, of which the most complete comes most likely from an Etruscan grave.10 (Some fragments with the same theme, however, were found at the Acropolis of Athens.) The god is depicted in an image signed by the great artist Sophilos, one of the few that also represents mythological scenes. It is not possible here to address interpretations, influenced by nineteenth-century preconceptions, of the Dionysus in this image as a marginal or minor deity.11 I will limit myself to observations more relevant to the history of religions. The very elaborate composition of this scene relates to the fact, well attested in Homer, Aeschylus, and Pindar, that the marriage of Peleus and Thetis was intended by Zeus to avoid a cosmic revolution. A revolution would in fact have come to pass if Thetis, whose son was destined to be stronger than his father, had been impregnated by Zeus himself or his brother Poseidon. With Peleus as father, this son remained a mortal, and so no danger to the order of the cosmos. To the extent that he was the protagonist of the Trojan War, necessary because of the overpopulation of the earth, Achilles would then instead have contributed to the stability of the rule of Zeus.

In the procession of the gods who celebrate the marriage of Peleus and Thetis, Dionysus, god of the vine, appears in a central position and with a more active role than that of the other actors. Of the many deities present, he is in fact the only one represented in the act of speaking—and he is turned toward Peleus. Sophilos—and after him also the great vase painter Kleitias—therefore attributes to Dionysus a crucial role in the wedding of Thetis and Peleus: that of the guarantor of the stability of the cosmos.

Sophilos’ and Kleitias’ images can be dated between c. 580 and 565 BCE. Thus we find them in the years in which the reforms of Solon were put into effect. The purpose of these reforms was, as is well known, to avoid internal revolution and to guarantee the continuity and stability of the polis. Hence the choice of the theme of the marriage of Peleus, which also represents the benefit of making clear the centrality of a proper marriage, that is, of the oikos, as the basic foundation of the polis -system of Solon.12

In the second quarter of the sixth century, the panorama of Dionysiac iconography becomes more complex. The subject of the dancers remains on cups, but explicitly associated with the symposium setting. Dionysus is represented jointly with a matron figure—as on the Cycladic crater of the seventh century—on tondos of a series of these cups:13 the allusion to matrimony is still evident here.

The crater, and then the dinos, remains another type of important vase of this phase, also in regard to support of the now more frequent mythological imagery. Here the figure of the satyr returns, but in two versions, one savage and one domesticated and associated with wine. I will not dwell on this theme, which is important for the history of religion but too complex for this discussion.14 The figure of Dionysus is present in the first representations of the Gigantomachia, on the side not of the Giants but, significantly, of the Olympians. We then find him in two contexts on the famous François Vase, dated around or shortly after 570 BCE.

In the procession of the gods depicted by Kleitias, Dionysus has substantially the same role as on the dinos of Sophilos.15 It is an analogous role, here also of the peace-maker of the Olympic family and thus of the guarantor of cosmic stability, which becomes attributed to the return of Hephaestus (not by chance, another tale of marriage).16 The figure of Hephaestus, a son repudiated and then reintegrated, as well as the god of fire, with doubtful Eastern or Lemnian origins, is perfectly explained, from the point of view of the history of religion, as a mythological reflection of the system of Solon, which made possible, as is well known, the return of the exiled Athenians and promoted the development of the crafts.17

Already on the François Vase we have a first version of the Dionysiac thiasos. This subject henceforth becomes increasingly more important. We fit it in monumental versions, on the famous crater of Lydos in New York,18 and then in variations on many amphorae. The fact that the latter dramatically increase in number around 560 BCE, and that these mythological images then definitively supplant the animal frieze, is related to the demand of the Etruscan market.19 The problem of the relationship between Athens and its western market, hitherto unduly neglected by archaeologists, is important also for the history of religions, as will be seen at the conclusion of this chapter.20

In the thiasos, the anonymous matron figure often returns with Dionysus, as we noted earlier.21 The grotesque dancers are replaced increasingly by satyrs accompanied by their partners (who would be called not “maenads” but “nymphs,” as they are explicitly identified on the François Vase22 ). Inside the thiasos, we often meet the mule-rider, normally anonymous but sometimes identifiable with Hephaestus. For the history of religions, it is important to note that the images of the mule-rider seem to refer rather to a ritual than to the myth of the return of Hephaestus to Olympus managed by Dionysus; it must, then, deal with a ritual of reintegration. In any case, the thiasos, with or without Dionysus, with or without the mule-rider, does not appear to develop only at the mythological level, but also at the human level; that is, it reflects a ritual situation.

It is in the third quarter of the sixth century that Dionysiac iconography marks the most dramatic changes, plausibly related to innovations in Athenian cult practice. The most important two types of support are now the amphora and the cup. Among amphorae, the most innovative productions from the iconographic point of view are those by the Amasis Painter, an excellent vase painter who was particularly interested in Dionysus. Here there are two innovations to keep in mind. The first pertains to the series in which Dionysus is seen in the center of a group of ephebes with the attributes of hunters or with equipment associated with the transportation of wine (Fig. 4.1). Here also, one would have to dwell on their particular iconography.23 Obviously the representations, all anonymous, allude to an event that is not mythological but ritual, which concludes a period of time spent by the ephebes outside the city. A mythological model of their encounter with Dionysus, patron of the polis, could be that of Oinopion with his father, as the great contemporary of the Amasis Painter, Exekias, represents it.24 The written information that survives is too fragmentary to know what kind of ritual and what kind of festival of the Athenian cult calendar are involved. The representations on vases, moreover, would not be descriptions of but allusions to them. In any case, we can deduce from these images that wine had an important role.25

Figure 4.1. Attic black-figured amphora by the Amasis Painter, Munich 8763. Panteon 35.4, 1977, 290 fig. 2. Courtesy Staatliche Antikensammlungen und Glyptothek.

The second innovation that interests us here is contained in the images of the thiasos by the Amasis Painter, in which not only is a role of leadership attributed to the partners of the male dancers, but ritual symbols, such as wreaths and shoots of ivy, are added. The representations say clearly that women are to introduce the dancers (and the satyrs) into the sphere of Dionysus.26 Here, too, we are in the dark as to the corresponding rituals, but we will find elements capable of clarifying the sense of these figures in contemporary productions of cups.

The kylikes were and remain the most important supports of the Dionysiac images. Cups with scenes of men’s lives, including symposia and grotesque dances, are followed by particularly refined vases, such as LittleMaster cups. The choice of figures here is greatly reduced, but one of the most frequent motifs is that of the female bust, evidently of a hetaera. We therefore remain in the ambience of symposia. Little-Master production continues to about 540 BCE. At this point, a type of cup entirely new in shape and decoration comes into fashion, apparently invented by Exekias: the eye-cup, the first and most celebrated of which is the one at Munich, from Vulci, with Dionysus reclining on a ship in the shade of a vine, encircled by dolphins.27

Instead of dwelling on the cup of Exekias, I shall look, if only for a moment, at a contemporary kylix from Capua of the same shape but without eyes on the outside, the work of a great anonymous vase-painter labeled by Beazley the Kallis Painter. The decoration is absolutely unique, which has made its interpretation difficult?28 On side A and side B we see only busts of Dionysus, explicitly named, and of hetaerae, similar to those of the Little-Master cups (Figs. 4.2-4.3). The fact that Dionysus is the protagonist of both sides indicates that we are dealing not with a singular scene but with two separate episodes, connected by a path. The attributes confirm this. On side A are branches of ivy and a drinking-horn (signs of a moment still very close to wilderness); on side B, vine-shoots and a cantharus (symbols of a civilized life).

On side B, in front of Dionysus, is a single female character explicitly called Semele, identifying her as the mother of Dionysus. Curiously, she is presented not as a matron but as a maiden. The gesture of Semele is also most unusual, without parallel in all of ancient art. It represents the goal of a Dionysiac journey and can be interpreted as gestural equivalence of the maxim, “I have seen but I do not speak.” The Dionysiac journey is thus a journey of initiation. We have two pieces of evidence for this reading. First is the fact, well attested even in Homer, that Semele died before the birth of Dionysus; she has therefore retained the status and the image of a maiden. She became a mother and her status changed, in death, just as happens to the initiate. The second confirmation lies in the fact that Semele was killed by lightning, as some of the famous Bacchic Mystery Leaves also say about initiates.29 If this interpretation is plausible, we must consider the Capua cup as evidence of Bacchic mysteries with Semele as protomystës.

Figure 4.2. Cup by the Kallis Painter, Napoli Stg. 172, Side A: photograph of the museum. Courtesy Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali.

Figure 4.3. Cup by the Kallis Painter, Napoli Stg. 172, Side B: CVA Napoli 1 pl. 22.1. Courtesy Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali.

We have, then, a piece of evidence for placing the institution of Bacchic ceremonies at Athens around or shortly after 540 BCE. In this light, the thiasoi by the Amasis Painter, which assign to women the role of intermediaries in the encounter between men—dancers and satyrs—and Dionysus, would be explained. The motif of the pair of eyes, standard decoration of Attic cups of these same years and lasting for two generations, would also be explained: the eye-cups signify seeing, even understanding by way of seeing, and are easily understood as a playful allusion to the mysteries. All this happens between 540 and 530 BCE, in the age of Peisistratus. We know of important innovations in the cult of Dionysus created by Peisistratus, like the procession in honor of Dionysus Eleuthereus, and like the performance of tragedies (in which the problem of seeing, which can fail to coincide with knowing, is one of the recurring themes, i.e., in the case of Euripides’ Pentheus and Auge, and of Lycurgus and Oedipus).30 To Onomacritus, active at Athens in these same years, Pausanias attributes the establishment of the Bacchic orgia.31 The iconographic situation cannot but confirm the introduction of Bacchic ceremonies at Athens and, shortly after, their adoption at Capua.

There can be no doubt that the kylix with Semele was created at Athens, but it is well established that it comes from S. Maria Capua Vetere—the perfect state of preservation shows this—from a noble tomb of ancient Capua. The evidence here, even if from two or three generations later, comes from the so-called Lenaea stamnoi, some of which were found at Capua (Fig. 4.4). This, too, is a topic that would deserve a separate presentation. In this case, I limit myself to assuming the relevant dates for the history of religion, which can be deduced from research of the past thirty years.32

What dates are secure, or at least highly likely, for these famous stamnoi? It is a question of an Athenian production destined generally for export to the West, especially to Vulci and to the zones of Campania culturally bound to Vulci, namely Capua and the surrounding area.33 The figures allude to orgiastic rites performed by women—not formal but rather domestic rites—concentrating on a temporary effigy of Dionysus and including the consumption of wine by women. An entire series of lekythoi in late black figure (i.e., in the fifth century), the majority found in tombs of Greece, alludes to rituals similar to those on the stamnoi. The archaeological evidence thus confirms the existence in the years around 500 BCE, in Greece as well as at Vulci and in Magna Graecia, of Dionysiac rites performed by women (even if the sporadic presence of satyrs confirms that men, too, were permitted to participate).34 The provenance from tombs of both stamnoi and lekythoi makes it plausible that these rites would have had — or would have been able to assume—a funerary orientation.

Figure 4.4. Attic red-figured stamnos by the Villa Giulia-Painter, Rome, Villa Giulia 93: Frontisi-Ducroux 1991: 73, figs. 7-8. Courtesy Françoise Frontisi-Ducrouz.

Figure 4.5. Attic Red-figured Volute Crater from Spina, Ferrara 2897: From S. Aurigemma, Scavi di Spina I (Rome, 1960), pl. 22a. Courtesy Museo Nazionale Archeologico de Spina.

With this I come to the final vase that contributes to the history of religions in Greece and Italy, the famous Attic volute crater of the Parthenon period, found in one of the richest tombs of Spina (the famous Etruscan harbor on the Adriatic), whose owner was an aristocrat of Vulci descent (Fig. 4.5).35 We have here, too, the representation of an orgiastic Dionysiac dance, in which not only women but also men and children participate. A procession with a covered liknon, clearly an allusion to secret rites, is seen in addition to the dance. The object of the celebration is a divine couple on a throne, the iconography of which associates it more with Hades than with Dionysus. I will not dwell on earlier interpretations, which propose to identify the divine couple as Sabazius and Cybele (we know the couple’s provenance is Asia Minor).36 It is in fact not only the iconography that renders the identification unlikely, but also the Etruscan provenance of the crater and the well-known, rich tomb equipment of which it was a part. If instead we consider the archaeological dates and compare them to what we know of the reception of the Greek gods, especially Dionysus, by the Etruscans, we would be able to deduce that here we are dealing with a ceremony that is secret, Dionysiac, and funerary, Athenian in origin but adapted to the religious custom of the Etruscans.

What is the contribution of the history of the images of Dionysus and his followers on Greek vases to the history of religions? The first important datum is the confirmation that Dionysus pertains not—or not only—to the exterior but to the center of the polis: that he is a peace-maker and guarantor of continuity. This is not intended to deny the importance of Dionysiac escapes such as the symposium, official festal moments of Dionysus, and Bacchic cults. But these escapes, of limited duration and in a controlled space, were the instruments through which the polis managed to reconfirm its cohesion and stability?37

After 550 BCE, in vase-paintings, the indications of rituals for which explicit testimonia are lacking in the surviving ancient texts increase. One of these rituals develops, one could say, around the mule-rider: one could speak of a rite of integration for people who did not enjoy complete citizenship, whose mythological prototype was Hephaestus. Another ritual would appear to have had as protagonists the ephebes of Athens, who were readmitted to the city after staying outside of it. To less official Dionysiac rituals could be referred the many images of thiasos beginning around 560 BCE.

Iconography can make important contributions also to the discussion of the Bacchic mysteries. Eminent examples are the kylix by the Kallis Painter discovered at Capua from around 540 BCE, the ritual scenes around an effigy of Dionysus that can be dated between 490 and 420 BCE, and the crater discovered at Spina, dated between 440 and 430 BCE. It is not unlikely that precise observations of Dionysiac iconography of the fifth century will, in the future, reveal further information relating to the history of religions in Greece and Italy.

1. Isler-Kerényi 2001a.

2. Isler-Kerényi 2001b.

3. Isler-Kerényi 2001a: 35, figs. 1-2; disregarded by Carpenter 1986.

4. Isler-Kerényi 2001a: 38, fig. 7.

5. Ibid.: figs. 8-9. The connection of this dancer with the theater, i.e., with the origin of comedy, so often discussed in the past, is not in fact verifiable: see Isler-Kerényi 2007b: 77-95.

6. Ehrenberg 1965: 25; Isler-Kerényi 1993: 3ff.

7. Isler-Kerényi 2001a: 39-80.

8. Ibid.: 107, fig. 34; 108, figs. 35-36; 109, fig. 37.

9. Ibid.: 70, fig. 13.

10. Ibid.: 109ff., figs. 38-40.

11. Carpenter 1986: 126. For a more extensive analysis, see Isler-Kerényi 1997a and then 2001a: 83-87.

12. Vernant 1973; Lacey 1983: 171 and passim.

13. Isler-Kerényi 2001a: 78, fig. 27.

14. It is treated separately in a forthcoming monograph: Civilizing Violence.

15. Isler-Kerényi 2001a: 111, fig. 41.

16. Ibid.: fig. 42.

17. Isler-Kerényi 1993: 8-9; Isler-Kerényi 2001a: 96ff. and 225.

18. Metropolitan Museum 31.11.11; Carpenter 1989: 29 (108.5); Shapiro 1989: tab. 74c.

19. Carpenter 1986: 35.

20. But see now Reusser 2002.

21. But neither in the sixth century nor later does she bear the name of Ariadne. On this problem, see Isler-Kerényi 2001a: 122ff.

22. On the problem of the correct denomination, see Hedreen 1994: 47-54.

23. Isler-Kerényi 2001a: 131-133.

24. Ibid.: 134 and 160, fig. 75: the two protagonists are explicitly named.

25. Cf. Scheibler 1987: 68-69, 107; Bérard and Bron 1984: 126-127.

26. Isler-Kerényi 2001a: 127-129.

27. For an interpretation of this cup, see ibid.: 178-188.

28. Ibid.: 175-178.

29. Riedweg 1998: 392-393, Ai, A2-3; for a critique of the Orphic interpretation of the lamellae, see now Calame 2002.

30. Isler-Kerényi 2001a: 181.

31. Pausanias 8.37.5 (cf. Isler-Kerényi 2001a: 226-227); Scarpi 2002: 376-377.

32. Isler-Kerényi 1997b: 99-101, with nn. 101-127. See also Peirce 1998.

33. We also know a stamnos from Kerch (Panticapaion) in the Crimea: CVA Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow (IV), pls. 12-13.

34. Cf. Guettel Cole 2003: 206: “Any rituals certifying completion of the ceremonies that generated these texts [= the tablets] must have been privately organized, performed in obscurity, and under no official control.”

35. For an analysis, see Isler-Kerényi 2003, where I discuss the Etruscan side of the phenomenon.

36. Simon 1953: 80-85.

37. So, with different arguments, see Vernant 1990: 238; Bierl 1991: 49-54, 219-226.