One of the features that most differentiates between Olympic religiosity and mystery cults in general (and particularly Orphic religiosity) is the image of the underworld. The religion of the polis is public and collective; its rites, its sacrifices, its processions serve as an element of social cohesion, as a way of integrating the individual in the community. This “bent toward this world” of the Olympic religiosity is consistent with the negative appeal offered by its image of the underworld, a dark and sinister place, populated by ἀμενηνὰ κάρηνα (Od. 10.521, etc.), ghosts without feelings. The Homeric image of Hades is so negative that a great hero like Achilles (Od. 11.489-491) says the following:

I should choose, so I might live on earth, to serve as the hireling of another,

of some portionless man whose livelihood was but small, rather than to be lord over all the dead that have perished. (Trans. G. Murray)

Nobody, not even Achilles himself, is free of this dark and sad fate, common to all. Mystery cults, on the other hand, allow people a religious life, to which they gain access by free choice, through initiation and the celebration of certain rites (τελεταί). They present an underworld in which the believer can reach different states, better or worse, by performing certain acts during his or her lifetime.

We have some data at our disposal that allow us to reconstruct a relatively coherent Orphic image of the underworld. Our information is both textual and iconographic.

The textual information available is of three types: 1) the gold lamellae, which allude to the joyful fate of the initiates after death and present us with some of the characteristics of the underworld;1 2) other texts that attribute features of the afterlife, either to Orpheus or to anonymous τελεταί, and that complement the image offered by the golden lamellae, especially regarding the fate of the initiates or of those who fail in the journey of the soul to the meadow of the blessed; and 3) texts that talk about the underworld, without quoting the source of the expressed ideas, but that are fairly coincident with the scheme reconstructed from the texts of the other two types, and therefore seem to be related to the Orphic world or a very similar field.

Iconographic information is problematic, and therefore it has been discussed whether there are parallels between the Orphic scheme of beliefs and the one shown by some pieces of Apulian pottery, specifically those that represent infernal scenes and some pinakes from Locri. For instance, Guthrie (1935: 187) denies the existence of such parallels, while Schmidt (1975: 129) considers that the Apulian vases representing Hades must be interpreted within an Orphic context, although she does not believe that they coincide with the world of the gold lamellae (cf. Schmidt 2000). Pensa (1977) dedicated a monograph to this topic with a well-balanced discussion of all relevant literature. Giangiulio (1994), for his part, has studied the relations between the religious and cultural thought of the gold lamellae, Apulian pottery, and the pinakes, as well as the Orphic-Pythagorean field.

In this chapter I focus on the analysis of a concrete aspect: the reconstruction of the common features between the Orphic infernal imagery and the imagery presented by the quoted iconography (Apulian and Locrian). However, it is not an iconographic analysis (which would be quite out of my professional expertise), but the attempt to reconstruct what we could call a common conceptual paradigm of the underworld expressed either in texts or in images, which has some points in common with the traditional Homeric one, but which differs from it in some fundamental features. In order to make the comparison easier, I itemize the different aspects.

We find in the text of the gold lamellae some verbs meaning “going down,” referring to the access of the soul to Hades, which obviously implies that Hades is situated in its traditional place, that is, beneath the earth.2 Some passages also allude to its darkness.3 The iconography on its part presents Hekate or Persephone or the Erinyes bearing torches (almost always in the shape of a sail) and includes the infernal image of Cerberus and some mythical damned sinners, which tradition places beneath the earth (ex. gr. Ruvo 1094, Naples SA 11, Munich 3297). To this extent, the image of Hades as an underground and dark place is not different at all from the traditional one (cf. ex. gr. Il. 8.477-481, 22.61, 22.482-483; Od. 24.203-204).

Both Homer and the gold lamellae refer to Hades as δόμοι or δῶμα.4 Homer even repeatedly alludes to the “doors of Hades” (Il. 5.646, etc.), but we find a marked difference in assessment between the Homeric description of Hades (Od. 20.64-65) as “the dread and dank abode, for which the very gods have loathing,” as opposed to its description as the “well-built house” of Hipponion 2.

The image of Hades in Apulian pottery shows buildings with smart columns, dwellings worthy of the divine sovereigns that inhabit them. On the other hand, a characteristic of the infernal geography of the gold lamellae is a white cypress, which is repeatedly alluded to as an enticement of one of the springs5 but is absent both in other literary descriptions of the place and in the figurative representations.

In contrast to Homeric Hades, defined as hateful without exception, the underworld described in the gold lamellae presents a totally different feature, since it has two roads, two possibilities, two fates for its inhabitants. First, we are told about two springs; to one of them, that of Memory, go only those who have been warned by the author of the sacred text included in the gold lamellae, while to the other, which has no name—but logically we have to consider it the spring of Oblivion—go the rest of the souls of the dead.6

There is also in Hades a privileged space, a locus amoenus, defined as a sacred meadow7 and separated from a much more unpleasant and gloomy place, often identified with Tartarus. The access to this locus amoenus is controlled by guards and by Persephone herself.

In one amphora, maybe from Vulci, today lost, the souls of the initiates were represented, standing before the guards that keep watch on Memory’s fountain, according to a description of the piece written by Albizzatti (1921: 260; cf. Pairault-Massa 1975: 199): “In a meadow full of flowers, separated from the region of the condemned by two trees with birds among the branches, two naked young men crowned with ivy and bearing thyrsus are on a grassy elevation, from which a spring rises. Behind each tree an oriental archer is kneeling and shooting an arrow.”

Those who have been warned not to drink of Lethe’s spring know a certain kind of truth;8 they have a knowledge of something that they must have acquired before, when they were alive, and that is not shared by everybody. It is, then, an initiatory knowledge that they must retain.9 It is clear, therefore, that in order to gain access to the privileged space in the underworld, it is necessary to be a μύστης, to have received an initiation. The μύσται know the roads they must follow and some kind of password (σύμβολα, Ent. 19, Pher.) that they have to say before the beings that guard the underworld,10 who block the way for those who do not have this information. Because of that, the water they have to drink is that of Memory, the goddess-guarantor of memory and initiation, and for this reason it is said that the gold lamellae themselves were Μναμοσύνας . . . ἔργον.11

The initiates are called μύσται καὶ βά̱ κχοι . . . κλε(ε)νινοί, “famed initiates and bacchi” (Hipp. 16). The gold leaf from Pherai tells us that the μύσται are free of punishment, which implies that those who are not μύσται are exposed to punishment. The Thurii lamellae reveal to us that the initiates also pay a penalty;12 we must therefore suppose that it is a general punishment for the whole of mankind. Our documents define this punishment as a terrible cycle from which the initiates manage to free themselves.13

However, apart from being initiated, the candidates to inhabit the locus amoenus claim to be in special conditions of purity, as in the famous initial declaration of the purity of the gold lamellae from Thur. (488-490) i: “Pure I come from the pure.”

The demand for the purity of the μύσται is also found in a fragment of the Rhapsodies (Orph. fr. 340 B. = 222 K.):

All who live purely beneath the rays of the sun,

so soon as they die have a smoother path

in a fair meadow beside deep-flowing Acheron, (…)

but those who have done evil (ἄδικα ῥέξαντες)

beneath the rays of the sun,

the insolent, are brought down below Kokytos

to the chilly horrors of Tartaros. (Trans. W.K.C. Guthrie)

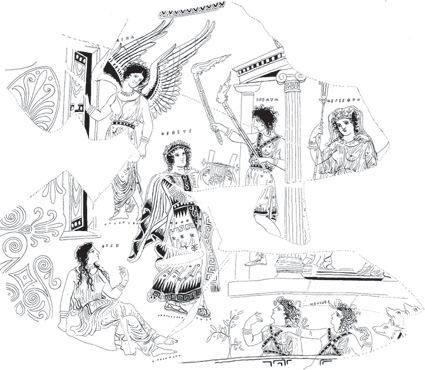

Figure 6.1. Fragment of Apulian Pottery from Ruvo. Ancient collection Fenicia, c. 350 BCE.

It is worth mentioning that in this passage, the pure are contrasted with the unjust, which implies that the observance of justice is a feature of the ritual Orphic purity and therefore that acting against Justice supposes impurity.

Apulian iconography would appear to confirm this idea, if indeed the goddess Justice (Dike) is represented in a ceramic fragment from Ruvo (ancient collection Fenicia, c. 350 BCE [Fig. 6.i]). Here the goddess appears next to Victory (Nike), who half-opens a door. Persephone and Hekate are also present with two torches.14 This door, half-opened by Victory, who seems to be offering a dead follower of Orpheus a way to a better place, is extremely suggestive. Justice is a well-known divinity within Orphism. In an old Orphic theogony, there were undoubtedly some passages referring to her as a goddess partner of Zeus, who watches the injustices of men so that Zeus can punish them. Plato refers to this immediately after alluding to Zeus’ hymn:

With him followeth Justice always, as avenger of them that fall short of the divine law. (Pl. Leg. 716a; Orph. fr. 32B. = 21K, trans. R. G. Bury)

Burkert has pointed out that the Platonic passage seems to paraphrase a similar verse from the Rhapsodies:

And Justice, bringer of retribution, attended him [Zeus], bringing succor to all.15

The same topic appears in a passage from a judicial speech in which one of the litigants tries to have an influence on the jury’s vote, referring to the way in which Justice watches over the unfair:

You must magnify the Goddess of Order (Εὐνομία) who loves what is right and preserves every city and every land; and before you cast your votes, each juryman must reflect that he is being watched by hallowed and inexorable Justice, who, as Orpheus, that prophet of our most sacred mysteries, tells us, sits beside the throne of Zeus and oversees all the works of men. Each must keep watch and ward lest he shame that goddess.16

It is quite significant that in the Derveni Papyrus (col. IV.5-9), the only fragment quoted from Heraclitus (B94 D.-K. = fr. 52 Marcovich) is that according to which the sun will never go above its measures, because the Erinyes, Justice’s assistants, will know how to find him. This passage, which refers to a transgression and to a punishment, reminds us of Hesiod’s description of Justice and the just state in Works and Days 212-224.

Therefore, the knowledge they have and the keeping of a pure way of life, which includes respect for Justice, allows the initiates that persevere with a pure or “correct” way of life to have a special fate in the underworld, in a sacred meadow.17 Because of that, we find several instances of gold lamellae that only indicate that the bearer is a μύστης (cf. Bernabé and Jiménez San Cristóbal 2008: 161-163, 267-269), thus serving to identify his (or her) status.

Those who gain access to the meadow are described as ὄλβιοι (Pel. 7; Thur. [488] 9) due to the happiness of their fate, and they are even claimed to achieve a special status, defined either as that of a ἥρως,18 or even as that of a θεός.19 The knowledge they require is revealed by an authorized anonymous narrator, whom we suppose is Orpheus (cf. Bernabé and Jiménez San Cristóbal 2008: 181-183).

A similar framework appears in other texts in which the τελεταί are mentioned. Pindar (fr. 131a Maehl. = 59 Cannata) therefore refers to the happiness produced by the “initiations that free from sorrows,” and in another fragment (fr. 137 Maehl. = 62 Cannata) mentions the fortune of the initiates that know “the end of life and the beginning disposed by Zeus.” The place where the blessed arrive in the underworld is a sweet-smelling locus amoenus, full of flowers, where they devote themselves to activities of the spirit (Pind. fr. 129 Maehl. = 58 Cannata), whereas those who have lived unholy lives lie in the darkness (Pind. fr. 130 Maehl. = 58b Cannata). In Olympian Ode 2.56, Pindar contrasts the fate of the violent souls, who immediately pay their punishment, to that of the good, who win themselves an existence free of hardship.

Plato for his part talks also about those who established the τελεταί to present us with a dual Hades, with one fate for initiates and those who have been purified, and another for those who have not:

And I fancy that those men who established the mysteries (τελετάς) were not unenlightened but in reality had a hidden meaning when they said long ago that whoever goes uninitiated and unsanctified to the underworld will lie in the mire, but he who arrives there initiated and purified will dwell with the gods. (Pl. Phd. 69c; Orph. fr. 434 III B. = 5 K.; trans. W.R.M. Lamb)20

Such an opinion had to be widespread in Athens, judging by the harsh criticism made by Diogenes the Cynic against those who believed that it was possible to win a special fate in the underworld only by being initiated:

It is absurd of you, my young friend, to think that any tax-gatherer,21 if only he be initiated (ἕνεκα τῆς τελετῆς), can share in the rewards of the just in the next world, while Agesilaus and Epameinondas are doomed to lie in the mire. (Iulian. Or. 7.25 [Diog. V.B332 Giannantoni = Orph. fr. 435 B.; trans. W. C. Wright)22

Diodorus transmits an important piece of information, which he probably took from Hekataeus of Abdera (fourth to third century BCE, cf. FGrH 264F25):

Orpheus … brought from Egypt most of the mystic ceremonies, the orgiastic rites … and his fabulous account of his experiences in Hades … the punishments in Hades of the unrighteous, the Fields of the Righteous, and the fantastic conceptions current among the many, which are figments of the imagination—all these were introduced by Orpheus in imitation of the Egyptian funeral customs. (Diod. Sic. L96.2-5; Orph. fr. 55B; trans. C. H. Oldfather)

Leaving aside the question of the supposed Egyptian origin that Diodorus’ source ascribes to the τελεταί,23 we find in this text the same scheme in which the punishments are opposed to the meadow. We can also see that Orpheus is held responsible for this imagery. The τελεταί seem, then, to be accompanied as λεγόμενα by a series of texts, which the old tradition mainly attributed to Orpheus.

The gold lamellae are silent24 about what happens to those who do not know the passwords or cannot identify themselves as μύσται. It seems that they should have a worse fate, without doubt in the dark and muddy places referred to in the other sources. Let’s try to get a more precise idea of this “space for the noninitiated.”

First of all, the Derveni Papyrus, clearly belonging to the Orphic framework, mentions the “terrors of Hades,” regrettably in a very fragmentary context:

The terror of Hades … ask an oracle … they ask an oracle … for them, we will enter the prophetic shrine to enquire, with regard to people who seek prophecies, whether it is permissible to disbelieve in the terrors of Hades.25 Why do they disbelieve [in them]?26 Since they do not understand dream-visions or any of the other realities, what sort of proofs would induce them to believe? For, since they are overcome by both error and pleasure as well, they do not learn or believe. Disbelief and ignorance are the same thing. For if they do not learn or comprehend, it cannot be that they will believe even if they see dream-visions…. (P.Derveni col. V.3ff.; Orph. fr. 473B; trans. R. Janko)

The vague allusion to the “terrors of Hades” ([τὰ] ἐν Ἃιδου δεινά) only informs us about the fact that in the Orphic lore, there was talk of those terrors. And an Orphic priest, as the Derveni’s commentator seems to be, considers it absurd that people do not believe in them.27

We find also in some close passages of the papyrus the presence of Erinyes that threaten the souls, of demons beneath the earth, of punishments in the underworld or perhaps also of initiates,28 as well as of certain rites carried out by the magoi to avert these dangers.

The fact that the terrors of Hades were also subject of the τελεταί is clear from a pair of texts of Origen:

And accordingly he [Celsus] likens us [sc. the Christians] to those who in the Bacchic mysteries introduce phantoms and objects of terror. (Origen Contra Celsum 4.10; Orph. fr. 596.I.B)

Celsus … shows us who have been moved in this way in regard to eternal punishments by the teaching of heathen priests and mystagoges.29 (Origen Contra Celsum 8.48; Orph. fr. 596.II.B)

As a concrete instance of punishment for the noninitiated, Plato mentions, in Phaedo 69c (a text to which I have already referred), “to lie in the mire.” This detail is recurrent in other texts. In addition to the ones that I will mention later, there are two by Aristophanes in the parody of the journey to the underworld of Frogs,30 and one by Aelius Aristides.31

Another text by Diodorus, coming from the same source as the one previously quoted, offers further information:

Many other things as well, of which mythology tells, are still to be found among the Egyptians, the name being still preserved and the customs actually being practiced. In the city of Acanthi, for instance, … there is a perforated jar to which three hundred and sixty priests, one each day, bring water from the Nile.32 (Diod. Sic. 1.97.1; Orph. fr. 62 B.)

Disregarding again the supposed Egyptian origin of the rites, it is clear that Diodorus’ source tries to base on an Egyptian custom (probably only a way of measuring time on a big clepsydra33 ) the typical image of the infernal punishment that involves pouring water into a large earthenware jar with holes. The two specific punishments that we have found so far in the texts, the mire and the sentence to carry water to vessels that cannot be filled, can be also found in Plato, in a curious variant: carrying water in a sieve.34

But Musaios and his son [cf. Bernabé 1998a: 46] … the unrighteous and unjust they plunge into a kind of mud in Hades and make them carry water in a sieve. (Pl. Rep. 363c; Orph. fr. 431 B. = 4 K.; trans. W.K.C. Guthrie)

In another text, Plato refers to the same tradition, to which he gives a symbolic interpretation:

The part of the soul in which we have desires is liable to be over-persuaded and to vacillate to and fro, and so some smart fellow, a Sicilian, I daresay, or Italian, made a fable in which—by a play of words—he named this part, as being so impressionable and persuadable (πιθανόν), a jar (πίθος), and the thoughtless (ἀνόητοι) he called uninitiates (ἀμύητοι); in these uninitiates that part of the soul where the desires are, the licentious and fissured part, he named a leaky jar (πίθος) in his allegory because it is so insatiate. So you see this person, Callicles, takes the opposite view to yours, showing how of all who are in Hades—meaning of course the invisible (ἀιδές) —these uninitiates will be most wretched, and will carry water into their leaky jar with a sieve, as my story-teller said, he means the soul: and the soul of the thoughtless he likened to a sieve, as being perforated, since it is unable to hold anything by reason of his unbelief and forgetfulness. (Pl. Gorg. 493a; Orph. frr. 430.II, 434.II.B; trans. W.R.M. Lamb)

Leaving aside the symbolic interpretations (which show that this kind of analysis was quite common in the fourth century BCE), as well as the free Platonic re-elaboration, which served his own philosophical and literary interests, the analyzed text presents the noninitiated in the underworld as being punished by bearing water in a sieve to a vessel with holes.

The pseudo-Platonic dialogue Axiochus, after narrating the fate of those inspired by a good spirit when they were alive, who are going to gain access to the place for the righteous, tells about those who directed their lives toward bad deeds (cf. Violante 1981):

They are led by Erinyes to Erebos and Chaos through Tartarus, where they find the dwelling of the unrighteous, the Danaids’ jars without bottom, Tantalus tormented by thirst, Tityos’ entrails devoured and always reborn, Sisyphus’ stone without end…. There they waste away in everlasting punishments, licked by wild beasts, constantly burnt with Furies’ torches and ill-treated by all kind of tortures. (Ps.-Pl. Axiochus 371e; Orph. fr. 434.IX B.)

In the burlesque description of the underworld offered by Aristophanes (Frogs 144-145), he does not mention the wild beasts, but he alludes to “snakes and vermin of all kinds.”

Another passage enlarges our knowledge about the close relation existing between the description of the terrors of Hades and the initiations:

In this world it [the soul] is without knowledge, except when it is already at the point of death; but when that time comes, it has an experience like that of men who are undergoing initiation into great mysteries: and so the verbs τελευτᾶν [die] and τελεῖσθαι [be initiated], and the actions they denote, have a similarity. In the beginning there is straying and wandering, the weariness of running this way and that, and nervous journeys through darkness that reach no goal (ὕποπτοι πορεῖαι καὶ ἀτέλεστοι), and then immediately before the consummation every possible terror, shivering and trembling and sweating and amazement. But after this a marvelous light meets the wanderer, and open country and meadow lands welcome him; and in that place there are voices and dancing and the solemn majesty of sacred music and holy visions. And amidst these, he walks at large in new freedom, now perfect and fully initiated, celebrating the sacred rites, a garland upon his head, and converses with pure and holy men; he surveys the uninitiated, unpurified mob here on earth, the mob of living men who, herded together in murk and deep mire, trample one another down and in their fear of death cling to their ills, since they disbelieve in the blessing of the Otherworld. (Plut. fr. 178 Sandbach; Orph. fr. 594 B.; trans. F. Sandbach)

This passage was analyzed by Díez de Velasco (1997: 413-416) as an excellent example of the features of a mystic experience: the result of a voluntary itinerary, movement through phases of darkness and suffering, and passing through an ineffable peak experience, which changes the identity of the one who feels it and which is ended with the union with an otherness of a transcendent kind. I consider this frame to be quite correct regarding the analysis of the phenomenon as included within a general typology; however, there are some details that could be added (cf. Bernabé 2001b).

Plutarch specifically states that the experience of death is similar to the one suffered by those who take part in the initiations into great mysteries. The identification of the mysteries to which he is referring has been a matter of discussion among scholars. Thus Foucart (1914: 393) believes that Plutarch refers to the mysteries of Eleusis. Díez de Velasco (1997: 413) seems to agree with this. However, Mylonas (1961: 265) considers that he alludes to an Orphic initiation, on the basis of the mention of the mire. Dunand (1973, 3:248) for his part thinks that Plutarch talks about Isis’ mysteries (but cf. Graf 1974: 132-139). The most likely interpretation would be that he refers to mysteries in general, and this is the most widespread opinion nowadays.35

In any case, the experience of the τελετή is considered to be very similar to that of death. This statement is “confirmed” by an etymological argument, quite typical of the philosophical analysis of the time: there is a strong bond between death (τελευτή) and τελετή, which motivates, in a cause-effect relation (διὸ καί), the etymological bond existing between their names. Such a bond, if not made explicit, was suggested by Plato in a famous passage, in which the etymological relation is a kind of wink at the reader:

And they produce a mass of books of Musaios and Orpheus, … according to whose recipes they make their sacrifices. In this way they persuade not only individuals but cities that there are means of redemption and purification from sin through sacrifices and pleasant amusements, valid both for the living and for those who are already dead (τελευτήσασιν). They call them teletai, these ceremonies which free us from the troubles of the Otherworld.36 (Pl. Rep. 364e; trans. W.K.C. Guthrie)

But what are the strong relations between the τελετή and death? Plutarch’s description is outstandingly ambiguous, because in some moments of his exposition he expresses contents that are common and similar to initiation and death, but in other cases he talks about realities that are only proper to initiation, and in others, about aspects that are only ascribed to death. We need to analyze the text part by part to see what comes from the imago inferorum and what from τελετή, although it seems in advance that the second tries to reproduce in some way the conditions of the first.

The journeys in darkness at the first moment are without doubt the movement of the soul toward Hades, a dark and gloomy place. The effects of terror, which are described, are physical effects, more suitable for initiation, where it is the person, not the soul, who suffers the experience; but it is not ruled out that Plutarch had in mind that the soul, when it arrived at Hades, would see the terrors that are alluded to several times.

It is obvious that the initiate passes through a phase of fear and confusion. But Plutarch subtly plays with the words. In the initiation level, ἀτέλεστοι does not mean “unfinished,” but “who are not yet initiated” (later, τέλος will mean “initiation”). By using ὕποπτοι, he can even play with a correlative ἐπόπται, “initiated in the highest grade of the mysteries,” and then invoke the meaning, “that they have not yet reached contemplation.”

Later, by means of a strong contrast, Plutarch describes what the soul of the dead sees at the end (τέλος) of the journey: it is a meadow and pure places (καθαροί), where there are a series ofὁρώμενα (light, dances, holy visions) and a series of λεγόμενα (sounds, sacred words). We suppose that in the τελετή these pleasant visions would be represented in some way. But now the description tends more to the experience of death than to the one of the mysteries, since what Plutarch describes is more similar to the meadow of the blessed in the underworld than to the entrance to an illuminated telesterion.

The description that follows, however, is exclusive to the mysteries. According to the mystery beliefs, the soul that, after death, reaches the meadow of the blessed never comes back. Therefore, the return described by Plutarch is the return of an initiate after initiation, while the following passage, in which is described the mob of living beings that persist in the fear of death in the middle of mire, is absolutely imprecise. It could be said to belong to real death. We have already seen the texts that talk about the mire, where the noninitiated lie, but if Plutarch is referring to them, how can those who are already dead persist in the fear of death? The persistence in the fear of death and the distrust of good things in the afterlife is characteristic of people who are alive and uninitiated. The reference is, then, deliberately ambiguous.

On the other hand, Plutarch informs us about the acquisition of knowledge in the τελετή. He tells us that the soul obtains knowledge at death’s door and that this situation is similar to the τελετή, from which can be deduced that knowledge is also acquired in the τελετή. Outside of initiation and death, there is only ignorance. Plutarch tells us about a liberation, which is without doubt opposed to the fear of the noninitiated, and he mentions the sanctity and purity of those who have been initiated, in contrast to the dirtiness and the mire of those who have not been initiated. Finally, he refers to the hope in a fate in the underworld, which the noninitiate cannot enjoy. We suppose a contrariis that the initiate would have hope in the underworld.

Thus, it seems that the τελετή was an experience similar to death or, better, a kind of rehearsal, so that the individual experiences the real death in advance and is not afraid of it. So it is possible to explain the constant confusion between the domain of initiation and that of real death, with which the author plays in the whole passage.

In another interesting text, a Bononiae Papyrus (third to fourth century CE, published after several other editions by Lloyd-Jones and Parsons 1978 = Orph. fr. 717B; cf. Bernabé 2003: 281-289), we find part of a poem in which is described the fate of the blessed and the condemned in Hades, whose coincidences with book 6 of the Aeneid have been high-lighted countless times. In verses 77 and 79 of the anonymous poem, we are told about the circulation of souls into and out of the underworld, and two roads are mentioned. There is probably one that goes down, that of the dead, and another one that goes up, that of those who have to be reincarnated. In verse 78 we are told about other souls that arrive, probably of those who have just died. In 124 there is mention of the “daughter of Justice, the very famous Retribution.”

In verse 129, we read θ]νητῶν μελ[έ]ων σκιόεν[τα] χιτῶνα, “the gloomy tunic of the mortal members,” an image that expresses the idea of reincarnation. We already know a similar image in other texts—for example, in Empedocles (B126 D-K), σαρκῶν ἀλλογνῶτι περιστέλλουσα χιτῶνι, “clothing in an unfamiliar garment of flesh” (cf. Gigante [1973] 1988). As components of the punishment, we find (PBonon. 26ff.):

] Ἐρινύες [ἄλλο]θεν ἄλλαι

]ς δ’ ἐκέλευσ[εν] ἑκάστη(ι)

πληγαῖς φον]ίοισιν ἱμά[σσει]ν.

Erinyes, one from one place, another from another,

and someone urged each of them

to whip them with bloody lashes.

And in verse 33, we see γαμψ]ώνυχες εἰλαπινασταί, “guests with crooked talons,” which, according to Lloyd-Jones and Parsons, refer to Harpies (cf. Pherecydes fr. 83 Schibli: φυλάσσουσι δ’ αὐτὴν . . . Ἅρπυιαι, “The Harpies guard it [sc. Tartarus]”). Both the Erinyes whipping the souls and the Harpies with terrible faces coincide with Vergil’s Aeneid: virginei volucrum [sc. Harpyiarum] vultus, foedissima ventris / proluvies, uncaeque manus, et pallida semper / ora fame (3.216-218); Gorgones Harpyiaeque (6.289); hinc exaudiri gemitus et saeva sonare / verbera (6.557-558); continuo sontes ultrix accincta flagello / Tisiphone quatit insultans (6.570-571). The privileged place is described in the Bononiae Papyrus as “splendid shining multicolored dwellings” (v. 126) and as a place where “neither the cloud of black waters nor hail accumulate nor the incessant rain oppresses, but there is prosperity day after day” (vv. 131ff.).

To sum up all that we have seen so far, it seems that the infernal punishments consisted mainly in: 1) a stay in a dark and muddy place, which involves fear, lack of comfort, and anxiety; 2) carrying water in a sieve to a vessel with holes (one of the models of useless effort, which was the worst punishment of which the Greeks could conceive in the underworld); 3) the attack of hostile beings, either wild animals and snakes, or Furies, Harpies, or similar monsters, which tore the souls into pieces or lacerated them, or burnt them with torches, although that naturally did not involve their destruction; and 4) after a period of punishments, the opportunity to try for salvation again in a new existence.

The most remarkable thing about the punishments imagined in Hades is that they are corporal. It is clear that it was assumed that the ψυχαί would keep in the underworld a kind of corporal configuration; at least, they were supposed to be able to suffer from physical agents. They also drink water, talk, and, in general, behave like people. The Orphic woman buried in Hipponion had a lamp beside her, and she had in her mouth a gold leaf, which gave her instructions for her journey through the underworld. If she hoped to use the lamp and to read the letters of the gold leaf, then she did not imagine this journey without her eyes and hands.

Apulian iconography offers us a similar frame in a series of pieces in which the infernal punishments of archetypical sinners are represented. This is the case of a crater of St. Petersburg (B.1717, 325-310 BCE), where Ixion’s punishment is shown. The center is occupied by a magnificent building seat of the infernal rulers, Persephone and Hades. Hades attends Hermes’ arrival. Below we see the Danaids carrying jugs of water to fill the vessel that is never filled. In the upper part appears one of the typical punishments — Ixion, tied to the wheel and accompanied by a Fury, a typical character in these representations (cf. Aellen 1994: passim), where the Furies are attendants of the gods responsible for punishing the condemned. In another two vases we find Hades and Persephone, out of their shrine: in one, from St. Petersburg (B.1716, 330-310 BCE), a Fury is at their right and the Danaids are below in the center; in another, from Ruvo (1094, 360-350 BCE [Fig. 6.2]), a Fury punishes a condemned person who seems to be more terrified than mortified. Indeed, literary sources do insist more on the “terrors of Hades” than on the physical punishments.

The space reserved for the initiates is nicer. It is in Hades, under the earth, imagined as a meadow,37 called the “meadow of the blessed” (Diod. Sic. 1.96.2-5 = Orph. fr. 55 B.) or “Persephone’s meadow,”38 and it is the place reserved for those who are in a situation of ritual purity.39 Plutarch presents it as full of light and pleasant music.40

A wide description of the happiness of this place can be found in the pseudo-Platonic Axiochus 371c, and it includes typical features like the meadow, the limpid waters, the music and dances, the gentle breeze under a warm sun, together with more cultural ones, like conversations for philosophers and a theater for poets. The author points out, too, that “there the initiated have an honored place, and they perform there their sacred rites.”

Figure 6.2. Apulian Crater. Ruvo 1094.

Linked to the mention of a meadow in Orph. fr. 487.6 are Persephone’s groves (ἄλσεα).41 Meadows and groves create an idyllic locus amoenus, which evokes rest and happiness, in short as reflection in the underworld of many earthly loci amoeni consisting in a little forest on the banks of a river. This will be the place where the initiate will enjoy eternal happiness. Similar descriptions can be found in fragments from Pindar’s Threnoi (see above).

Apulian pottery does not offer us clear images of the happy place, which we could ascribe to an Orphic environment, although a series of pieces represent a heavenly place related to Dionysus.42 Other works belonging to the immense Dionysian iconography are not, of course, incompatible with this universe. For example, a Basel amphora (S29; cf. Schmidt, Trendall, and Cambitoglou 1976: 6 and 35ff., tab. 8e, 10a)43 in which we find an “automatic” wine miracle. This image reminds us of the “wine happy honor” of Pelinna gold leaf, or of a crater from Tarentum (61.602) in which a woman receives a satyr in a naiskos, as well as the numerous symposiac scenes, including those that decorate the sarcophagus from the so-called Tomb of the Tuffatore (Diver), that could allude to a banquet in the underworld. However, it is obviously difficult to demonstrate an Orphic presence in these cases. We also find works in which Orpheus appears, where the possible relation to the locus amoenus or the netherworld meadow would be indicated by the presence of the mediator or by details such as Nike (Victory) half-opening a door.44

The goddess that rules over the netherworld according to the Thurii gold lamellae is Persephone. The souls come, imploring, before her.45 The goddess may also be mentioned in Ent. 20, καὶ φε (cf. Bernabé 1999b). Persephone is without doubt identified with Brimo, mentioned in Pherecydes, and with the one called “Queen of the Dead” in the Thurii lamellae ([488490] 1), the Roma lamella (1), and probably in the Hipponion lamella (13).46 She is not only the queen of the dead, but she is also responsible for the last decision regarding those that arrive at the netherworld.47 Hades, under the name Eucles, and Dionysus, with the epithet Eubuleus, are also mentioned together with her. In the Pelinna fragments, Dionysus appears again in a more significant way, as Βάκχιος, to whom is attributed the liberation of the soul of the dead. The strange epithet Ἀν(δ)ρικεπαιδόθυρσον, which serves as σύμβολον in Pher., also refers to him.

The relationship between Bacchus and Persephone is typically southern Italian,48 and it is probably due to the well-known Orphic myth according to which Dionysus is Persephone’s son, the Titans tear him apart, and from the remains men are born (cf. Bernabé 2002).

The same role for Persephone can be found in Pindar (fr. 133 Maehl. = 65 Cannatà cf. Bernabé 1999a). Persephone and Dionysus also appear, together with Orpheus, in a fragment of the Rhapsodies:49

The happy life … which the initiates in Dionysus and Kore according Orpheus wish to achieve:

“He commends them

to cease from the cycle and have respite from evil.”

This role for Dionysus is absolutely alien to the Homeric world, and Persephone’s role is totally different from the one represented by the goddess in Homer and Hesiod, where she is repeatedly mentioned as a horrible goddess.50

The hypothesis that the text of the gold lamellae was considered a work of Orpheus is very plausible (cf. Bernabé and Jiménez San Cristóbal 2008: 181-183; Riedweg 2002). Orpheus, due to his quest for his dead wife, is supposed to have seen what happened in the underworld and come back to tell about it. It is therefore clear that the Thracian bard was considered by the users of the gold lamellae as a human mediator, who through initiation explains the path that the souls have to follow to achieve their salvation. The numerous texts that ascribe to Orpheus the τελεταί or concepts about the underworld related to them insist on the same idea.51

But we have seen that there is also a divine mediator, Dionysus, because it is this god who intercedes with Persephone for the soul of the Pelinna believer, a role he has also in the Gurob Papyrus (18-22; cf. Hordern 2000), in which the participants in the rite invoke Eubuleus (Dionysus), also called Ἰρικεπαῖγε,, and they ask the god to save them.

Some features of this view of the netherworld appear in the Locri pinakes, from the second quarter of the fifth century BCE (cf. Giangiulio 1994; Olmos 2008: 284-288). In one of them (Mus. Arch. Naz. Reggio Calabria 58729 [Fig. 6.3]), the wine-god offers a kantharos of wine and a branch with bunches of grapes to the corn goddess. It is highly probable that they are Dionysus and his mother Persephone. There are other exemplars, one of which was precisely found in Hipponion. In these images, Dionysus is the mediator who symbolically substitutes the faithful supplicant on his arrival at the kingdom of death, when he presents himself before the god’s mother. In another model (Reggio Calabria 21016, mid-fifth century BCE; cf. Olmos 2008: 284-288, with discussion of interpretations [Fig. 6.4]), we find Persephone represented as the “goddess of underworld beings,” to whom the Thurii gold lamellae allude, enthroned with Hades and accepting the offerings of an invisible supplicant, who is without doubt deceased.

Apulian pottery offers us a series of pieces in which, together with the kings of the underworld and the condemned, appears a mediator who can be either Dionysus or Orpheus. In an Apulian crater conserved in the Museum of Art of Toledo, Ohio (340-330 BCE; cf. Johnston and McNiven 1996; Olmos 2008: 291-293 [Fig. 6.5]), we find the only representation preserved in which Dionysus makes a pact with Hades, shaking hands with him in the presence of Hermes. Next to Dionysus are the members of his retinue, a paniskos and a maenad with a thyrsus and a tambourine, who dances with the bare breast. On the other side of the temple are represented the condemned Actaeon and Agave. The message of the pact is clear: the initiates in the mysteries of Dionysus, the mystai, will receive special treatment in the netherworld and will find rest from their toils.

Frequently, Orpheus is the mediator. It is obvious that his presence in the netherworld is related not to the search for Eurydice (who never does appear, at least in an unequivocal manner),52 but rather to his role as a protector of certain souls on their arrival at the underworld. In an Apulian crater from Canosa of the Munich Museum (Fig. 6.6),53 Orpheus arrives at the palace of Hades and Persephone. He is dressed in the oriental manner, as a Thracian singer, and his long priestly dress flaps to the rhythm of his dancing step, which follows the sounds of the zither. It seems as if he wants to seduce the gods with his chant. A man, a woman, and a child come behind him. Although the role of these characters has been discussed, it seems obvious that they are a family of initiates. In the vessel we find also numerous personifications and heroes: Justice beside Theseus and Peirithoos; the judges of the netherworld, Aeacus, Minos, and Rhadamanthys; the Erinyes; great sinners like Sisyphus or Tantalus; Hermes Psychopompus; Cerberus, tamed by liberator Herakles; and the Danaids; but, as Schmidt (1975: 123) points out, they show little zeal in their hard work, as though they are going to be absolved soon.54 The big Apulian crater is a representation of the kingdom of Justice and the cosmic order, which punishes the impious actions of the noninitiated. The queen Persephone and her husband Hades preside over its reestablishment in the underworld space.

Figure 6.3. Locrian Pinax. Reggio Calabria 58729.

We find a similar model in other Apulian craters, like one of Matera (no. 336, 320 BCE), and another at Karlsruhe (B4, 350-340 BCE; cf. Pensa 1977: 24). In another one, at Naples, from Armento (SA 709, 330-310 BCE [Fig. 6.7]; cf. Pensa 1977: 27), the same themes are repeated, but without the characteristic representation of a building. Orpheus arrives in the presence of Hades and Persephone, and he has a woman by the hand. In the light of the other exemplars, it seems clear that we have to interpret the scene as Orpheus presenting a deceased woman before the gods of the netherworld rather than as a rendering of Orpheus with Eurydice.55

An interesting variant is offered to us by the fragments that were in Ruvo (ancient collection Fenicia, c. 350 BCE [see Fig. 6.1]; cf. Pensa 1977: 25), to which I have already referred, in which we see Victory half-opening a door—that of the netherworld—and Justice, Orpheus, Persephone, and Hekate with two torches.

Figure 6.4. Locrian Pinax. Reggio Calabria 21016.

Figure 6.5. Apulian Crater. Toledo, Ohio.

Finally, in another crater at Naples (3222, 350-340 BCE; cf. Pensa 1977: 24), we find beside Orpheus other characters and personifications, like Megara, the Poinai, Ananke, Sisyphus, Hermes, Triptolemus, Aeacus, and Rhadamanthys.

As for Victory, she is not alien to the world of the gold lamellae either: in Thur. (488) 6, the reference to the soul that was liberated from the cycle and “came on quick feet to the desired crown” is that of the winning athlete; although the image of the crown in the gold lamellae is polyvalent, it is at the same time a funerary crown and a mystic, banquet, and triumphal one (cf. Bernabé and Jiménez San Cristóbal 2008: 121-128).

Together with this quite widespread type, in which we find the scene of prizes and punishments, the divine rulers and the mediator, there is a different type that also shows Orpheus as mediator, but without the presence of the damned sinners and of Persephone. We have variants: one is a red-figured Apulian amphora attributed to the Ganymedes painter (Basel, Antikenmuseum 540, 330-320 BCE; cf. Olmos 2008: 280-283 with bibliography [Fig. 6.8]). A man seated within a white shrine or naiskos, very similar to Persephone’s palace represented in other pieces, receives Orpheus. He is seated on a portable chair. It is curious enough that a chair with these characteristics seems to have been represented in one of the bone tablets from Olbia, also from an Orphic environment (IGDOlb. 94c Dubois; cf. West 1982 [Fig. 6.9]). The most interesting feature is that the deceased holds a volumen in his hand. There is little doubt that this is a funerary initiation text. The image makes explicit that the knowledge that Orpheus transmits to the initiates is in a text.

Another Sicilian piece, from Leontini (Trendall 1967: 589 n. 28; cf. Schmidt 1975: 177-178), is also similar to piece from Olbia in many aspects, but without the presence of a text. We see Orpheus and Hermes in a naiskos with a deceased woman.

Figure 6.6. Apulian Crater from Canosa. Munich Museum 3297.

Figure 6.7. Apulian Crater from Armento. Naples Museum SA 709.

A different type is found in a crater of the British Museum in London (F270 [Fig. 6.10]; cf. Schmidt 1975: 120-122 and tav. XIV; also Pensa 1977: 30). Orpheus and a young man are at the entrance to Hades, marked by a herm. Orpheus bears Cerberus with a chain because he has tamed him with his music, and thus he assumes the function of a protector that defends the young man, without doubt an initiate, against the terrors of Hades.

We see that the basic features of the underworld represented in the iconography we have studied make up a conceptual universe in agreement with the one presented in the textual Orphic fragments:

1. The underworld is an underground and dark place, but has buildings.

2. It is ruled over by Persephone and Hades, although the main character is a friendly and affable Persephone.

3. It is a dual space, with prizes and punishments.

4. For the punishments, the artists choose as paradigmatic representation the clearest and most recognizable sinners of the mythical tradition, like Sisyphus, Ixion, or the Danaids. The latter appear to be carrying out the typical punishment of filling vessels that cannot be filled. The beings responsible for the punishment are the Erinyes.

5. The prizes are related to the idea of proximity to the divine, and they are symbolized by the presence of the mediators.

6. There is a divine mediator, Dionysus, and a human one, Orpheus (always represented at the frontier between the palace and the rest of the space, sometimes with the clear presence of the believer).

7. We find in one case the representation of text as support of the Orphic revelation.

8. The personifications of Justice and Victory allude to the need of the mystēs to respect the dictates of the former and to the triumph they can receive in the underworld if they reach the status of the privileged. They also indicate that Justice presides over the triumph of those who are privileged in contrast to the defeat and punishment of those who are not.

Figure 6.8. Apulian Amphora from Basel. Antikenmuseum 540.

Figure 6.9. Olbia Bone Tablet.

Figure 6.10. Apulian Crater. British Museum F270.

Schmidt (1975: 129), however, states that the universe of the Apulian infernal pottery does not coincide with the one of the gold lamellae:

The original inspiration of the netherworld images in Apulian art perhaps must be searched in an epic of religious coloring, or better in religious poetry belonging to a certain cultural level. This poetic background is not necessarily Orphic.

Yet Orpheus’ presence, particularly in the amphora of the Ganymede artist, led this scholar to assert:

We could suppose that the figurative creation derived from these sources would have been reused also by followers of some Orphic ideas … in the … image of the new amphora by Ganymede painter … we could deal with an “Orphization” of a more generic prototype.

This statement is unfounded and dictated, I think, by two prejudices, which seem to be superseded. The first prejudice is the idea that the gold lamellae reflect the beliefs of people of low cultural level. But it does not seem appropriate to attribute low cultural level to believers who can afford expensive gold lamellae, put in rich tombs, whose beliefs seem to have been shared by the Sicilian tyrants that contract Pindar. The second prejudice is the supposition that the verses of the gold lamellae are a kind of sub-literature. Riedweg (2002) makes a strong case that there is a hieros logos behind them. This poem would be without doubt an example of an “epic of religious coloring” or a “religious poetry belonging to a certain cultural level” required by Schmidt. Also wrong is the idea (Schmidt 1975: 133) that the representation of Dionysus’ birth from Zeus’ thigh is not Orphic because Semele’s son is not Orphic. As I have demonstrated in another paper (Bernabé 1998b), and as is reflected in the corresponding fragments of my edition (Bernabé 2004b), this topic was already dealt with in the Rhapsodies and probably before.

The only possible doubt is whether we can call “Orphic” this religious continuum that we have reconstructed, which would probably present differences of detail from place to place. But it is obvious that if we do not do so, the explanation is more complicated. What other movement could we reconstruct that joins Persephone and Dionysus with Orpheus as mediator, resorts to sacred texts, and presents a netherworld with the possibility of prizes and punishments? It seems more plausible to think that the texts serving as basis for the artists would be the ones used in the τελεταί, which would include performances of the sacred mystery in the form of κατάβασις in a kind of imitatio mortis, preparing the believer for the great experience.

The underworld of Apulian pottery is not always a terrible place. It can be a pleasant place if the faithful resorts to the due mediators, and if he/she is a follower of the Orphic-Dionysian mysteries. These vessels transmit, then, above all, a religious message, a message of hope, which is substantially the same as the one found in the gold lamellae.

The reasons for the few differences between the texts and the representations have to be seen in the nature of both channels: one is discursive, and the other is a visual representation, which forces the artist to represent, condensed, in one scene, what the texts would tell in several episodes, and to visualize some concepts that are difficult to reflect by means of images.

The benefits of the situation obtained by the initiate’s soul in the underworld, about which pottery is not very explicit, can be known through the statements of the gold lamellae. First, the initiate is free of punishment (ἄποινος, cf. Pher.), which implies that the noninitiated must suffer punishment.56 Second, he enjoys the privilege of wine, mentioned in the Pelinna gold leaf as “happy honor” (Pel. 6: οἶνον ἔχεις εὐδ(α)ίμονα τιμή(ν)) and present in the Gurob Papyrus, according to a recent rereading (Hordern 2000). Thur. (488) 6 mentions a crown (although the crown is a polyvalent symbol, as we have seen; see above). Both features, characteristic of the symposium, approximate the situation ridiculed by Plato, defined as “everlasting drunkenness,” the frame of happy life in the underworld alluded to in the gold lamellae:

But Musaios and his son grant to the just more exciting blessings from heaven than these. Having brought them, in their writings, to the House of Hades, they make them recline at a drinking-party of the righteous which they have furnished, and describe them as passing all their time drinking, with garlands on their heads, since in their opinion the fairest reward of virtue is everlasting drunkenness. (Pl. Rep. 363d (Orph. fr. 431B; trans. W.K.C. Guthrie; cf. Bernabé 1998a: 46)

Other passages coincide in presenting the underworld as a banquet with plenty of wine. Aristophanes (Frogs 85) alludes to the “feast of the blessed” in the underworld, and (fr. 504 K-A) puts forward the need to go soon down to Hades to drink, because those who are there are called happy precisely due to their constant drinking of wine. Pherecrates (fr. 113.30-33 K-A) describes how, in the underworld, young maids offer cups full of wine (cf. Aristoph. fr. 12 K-A). In an epigram from Smyrna (Epigr. Gr. 312.13ff. Kaibel) is described the present fortune of the deceased: “The gods are seeing me as a friend, while I enjoy the banquet beside the tripods and immortal tables.” Passages like this have led Pugliese Carratelli (1993: 64 [= 2001: 118s]) to consider that Orphism, which primitively would have been a mere mystic theology, would have degraded due to a materialist version later spread and spurned by Plato. But the situation can be exactly the opposite.

The third benefit that the soul of the mystēs achieves in the underworld is happiness (ὄλβος),57 a complex concept, which we do not know how to define, whether as a “material wellness” or as a deeper feeling arising from the company of the gods. Finally, the mystēs achieves also glory, according to Hipp. 16. These conditions are consistent with the sensation of triumph underlying the mention of the crown, to which I have repeatedly alluded. After the hard proof of having passed through several lives in this world, and after the constant training of the one that keeps an ascetic life, the soul achieves the crown of triumph: after its victory in the final proof, it is glorious and happy and celebrates with an eternal banquet.

The condition acquired by the soul is defined in different ways. Plato’s statement (Phd. 69c), “It will dwell with the gods,”58 places the initiates in a clear situation of privilege, although he does not tell us plainly that they also become gods. The gold lamellae offer us an ambiguous testimony. Sometimes the mystēs is called “hero” (Ent. 2, Pet. 11), which means a change in the traditional heroic status that belonged to those who had distinguished themselves by their deeds in war. It seems that, in the religious schema of the gold lamellae, it is the memory of the initiation that allows one to reach this status (Ent. 2).59 It is predicted that the soul will “reign” (Pet. 11), but, since it is a reign shared with a group (“you will reign with the other heroes”), we suppose that the expression only means that the soul has freed itself from any submission. Finally, the new state of the soul is alternatively defined as “becoming a god” in the lamellae from Thurii as well as in the lamella from Rome,60 but probably we do not have to understand that it is a personal god who receives worship if we take into account that the idea of divinization was exceptional in the Greek religious world.61 It is more likely that the situation reached by the initiate after his liberation and definitive death, which is defined as a rebirth in the bosom of the chthonic goddess and is symbolized by the image of the divine kid breastfed by her in his new happy life, is a glorious new life, in which the mystēs identifies with Dionysus (let us remember that he is βάκχος himself). Although his stay in the underworld does not totally match that of the gods, it involves going beyond the human condition and acquiring a divine (superhuman) status, although probably of a lower grade than that of traditional gods,62 that is, that which is defined by a synonymous term as the condition of “hero.”

Above I reviewed a series of conditions that the mystēs must fulfill to gain access to the privileged space in the underworld. In short, he must have experienced initiation, which gave him a certain knowledge about the course of the universe and the place of his soul in the whole; and he must have passed through certain rites, which included the ecstatic experience and which involved both the expiation of a blame shared by all human beings and the acquisition of a ritual purity, which had to be retained subsequently within the strict confines of justice. All of this allowed the initiate’s soul to triumph in the tests that served as filters for the soul on its way to the underworld.

Nevertheless, the sources describe for us two models of access to the locus amoenus. In one of them, the ritual element was the main one, in such a way that it was enough that the initiate know a series of formulas and passwords (on some occasions, it seems that it was enough that he simply bear the identification as mystēs) to gain access to the due place. This is the schema we find in the Orphic gold lamellae. Another model existed as well, according to which the soul suffered a trial. (This is the one that we find, for example, in Pind. O. 2, or in the Er myth of Plato’s Republic and later in the Bononiae Papyrus.) In this case, what was fundamental for determining the fate of a deceased in the underworld was his behavior on earth. We do not know whether both models coexisted or if the second was a result of an evolution of the first (in which case it would have been proposed for the first time by Pindar and Plato and assumed later in Orphism).63 In any case, the image of the Orphic underworld seems to have its roots in very old precedents: an early belief in a Mother Earth that produces a new rebirth; the image, probably Indo-European, of the green meadows of the underworld;64 possible Egyptian influences in which the soul is questioned and has to pronounce certain passwords to gain access to a more pleasant underworld; and perhaps East Indian influences in a theory of reincarnation—all of this set in an infernal scenario, which is basically the traditional Greek one of Homer and Hesiod, but subverted in its symbolism and its meanings. The result is an original synthesis, and, as such, is deeply Greek. This model had validity for a long time, although it was always limited to more or less isolated groups of followers who never formed a Church.

The naiveté of some aspects of this belief makes it unacceptable for more rationalist minds. That, together with the fact that the punishments probably had from the very beginning a precise symbolic value, favors a reinterpretation and reanalysis of the described schema. The mire is typical of people who have not cleaned themselves of their sins (cf. Plot. 1.6.8), and the sieve is a reminder of the cause for the punishment: the inability to separate from the soul the titanic and evil elements that belong to it while retaining the Dionysian and positive elements (cf. Bernabé 1998a: 76). In Plato, on the one hand, we find traces of symbolic interpretations, which could be his or could reflect those existing in his time. On the other hand, the philosopher adapts the initiation model to philosophy and points out that the initiates are the real philosophers, whereas those who are in the mire and in darkness are the ignorant. The process of symbolization will come to its late consequences with the Neoplatonists, but this is not the right moment to go into this question. Let us leave as more interesting, then, the function that the presentation in the Orphic τελεταί of the terrors of the underworld initially assumed: on the one hand, the scale representation of fate in the underworld led the subject to carry out the rites due and to behave correctly; on the other, it calmed his anxieties by convincing him why he has thus been given a means of attaining happiness in the underworld. The presentation of the terrors of Hades functioned, then, as a kind of psychological vaccine that must have been extraordinarily effective.

This chapter is one of the results of a Research Project financed by the Spanish Ministry of Education and Science (HUM2006-09403). I am very grateful to Helena Bernabé for the translation of this paper into English, to Sara Olmos for her drawings, and to Patricia Johnston and Giovanni Casadio for their revision of the text and helpful suggestions.

1. In this chapter and only for the sake of convenience (for want of a more explicit term), I talk about “initiates,” referring without distinction to those who have received the μύησις and to those who have celebrated the τελεταί, although it is obvious that the μύησις are not only limited to initiation (cf. Jiménez San Cristóbal 2002). From now on, I will use the following abbreviations for the gold leaves: Eleuth. = Eleutherna (Orph. frr. 478-480 Bernabé [from now B.] = 32b I-III Kern [from now K.] and 482-483 B.); Ent. = Entella (Orph. fr. 475 B.); Hipp. = Hipponion (Orph. fr. 474 B.); Malib. = Malibu (Orph. fr. 484 B.); Pel. = Pelinna (Orph. frr. 485-486 B.); Pet. = Petelia (Orph. fr. 476 B. = 32a K.); Phars.= Pharsalus (Orph. fr. 477 B.); Pher. = Pherai (fr. 493 B.); Rom. = Roma (Orph. fr. 491 B. = 32g K.); Thur. = Thurii (Orph. fr. 487-490 and 492 B. = 32f-cd and 47 K., quoted with the number of the fragment of B.). The English translation of the gold leaves is generally that of Radcliffe G. Edmonds.

2. Hipp. 4; Ent. 6: ἔνθα κατερχόμεναι ψυχαὶ νεκύων ψύχονται, “There the descending souls of the dead refresh themselves”; Pel. 7: καὶ̣̣ σ̣ὺ μὲν εἶς (Luppe: κἀπ(ι)μένει ed. pr.) ὑπο̣ γῆ̣ν, “And you will go (or ‘they await you’) beneath the earth.”

3. Hipp. 9: Ἄιδος σκότος ὀρφ(ν)ήεντος, “The misty shadow of Hades”; cf. Ent. 11.

4. Hipp. 2: εἰς Ἀίδαο δόμους εὐήρεας “To the spacious halls of Hades”; cf. Pet. 1: εὑρήσ{σ}εις δ’ Ἀίδαο δόμων ἐπ’ ἀριστερά, “You will find in the halls of Hades a spring on the left”; Phars. 1: Ἀίδαο δόμοις, “In the halls of Hades”; as well as Il. 15.251, δῶμ’ Ἀίδαο, and Od. 10.491, εἰς’ Αίδαο δόμους.

5. Hipp. 3: πὰρ δ’ αὐτὰν ἑστακῦα λευκὰ κυπάρισ(σ)ος, “And by it stands a glowing white cypress tree”; cf. Ent. 5; Pet. 2; Phars. 2. About its symbology, see Bernabé and Jiménez San Cristóbal 2008: 25-28, with bibliography.

6. Hipp. 2: ἔστ’ ἐπὶ δ(ε)ξιὰ κρήνα / . . . / ἔνθα κατερχόμεναι ψυχαὶ νεκύωνψύχονται, “A spring is on the right … there the descending souls of the dead refresh themselves”; 5: ταύτας τᾶς κράνας μηδὲ σχεδὸν ἐγγύθεν ἔλθηις, “Do not go near to this spring at all”; cf. Ent. 4 and 7; Pet. 1 and 3. Cf. also Hipp. 6: πρόσθενδὲ εὑρήσεις τᾶς Μναμοσύνας ἀπὸ λίμνας . . . ὕδωρ, “Further on you will find, from the lake of Memory, refreshing water”; cf. Pet. 4; Ent. 8; Phars. 4. The idea only reappears in Pausanias 9.39.8, about a place that is not infernal, but that tries to be a reflection of the otherworld, the Trophonius’ cave.

7. Thur. (487) 6: λειμῶνάς θ’ {ε} ἱεροὺς καὶ ἄλσεα Φερσεφονείας, “Persephone’s sacred meadows and groves”; Thur. (489) 7: ὥς με{ι} πρόφ(ρ)ω(ν) πέμψη(ι) ἕδρας ἐςεὐαγέ{ι}ων, “That, gracious, may send me to the seats of the blessed.”

8. Phars. 7: πᾶσαν ἀληθείην καταλέξαι, “You should relate the whole truth.” Cf. Tortorelli Ghidini 1990.

9. Thur. (487) 2: πεφυλαγμένον εὖ μάλα πάντα, “Bearing everything in mind”; cf. Ent. 2:μ]εμνημέ(ν)ος ἥρως, and Bernabé’s (1999b) interpretation, “Hero that remembers” (i.e., the one who is a hero because he remembers initiation).

10. First before the guards that keep watch on Mnemosyne’s water; cf. Hipp. 10: Γῆς παῖ(ς) εἰμι καὶ Οὐρανοῦ ἀστερόεντος, “I am the child of Earth and starry Heaven” (cf. Ent. 10; Pet. 6; Phars. 8; the declaration ἐμοὶ γένος οὐράνιον [“My race is heavenly”], Ent. 15; Pet. 7; Malib. 4; and Ἀστέριος ὄνομα [“My name is Asterios”], Phars. 9), and last, before Persephone herself, Thur. (488-490) 1:ἔρχομαι ἐκ καθαρῶν καθαρά, “Pure I come from the pure”; or Thur. (488) 3: ὑμῶνγένος ὄλβιον εὔχομαι εἶμεν, “I also claim that I am of your blessed race.”

11. Hipp. 1: Μναμοσύνας τόδε ἔργον, “This is a work of Memory”; cf. Orph. Hymn. 77.9-10:μύσταις μνήμην ἐπέγειρε / εὐιέρου τελετῆς, λήθην δ’ ἀπὸ τῶν〈δ’〉ἀπόπεμπε, “For the initiates stir the memory of the sacred rite and ward off oblivion from them” (trans. A. N. Athanassakis).

12. Thur. (489) 4: πο〈ι〉νὰν δ’ ἀνταπαπέ{ι}τε{σε}ι〈σ〉’ ἔργων ἕνεκα οὔτι δικα〈ί〉ων, “I have paid the penalty on account of deeds that are not just.” About ποινή among the Orphics, cf. Santamaría Álvarez 2005.

13. Thur. (488) 5: κύκλο〈υ〉 δ’ ἐξέπταν βαρυπενθέος ἀργαλέοιο, “I flew out of the circle of wearying heavy grief.”

14. It seems to me much more likely to read Δ]ΙΚΗ instead of ΕΥΡΥΔ]ΙΚΗ (too long for the space) in the inscription next to the seated woman, and ΝΙΚΑ instead of ΑΙΚΑ next to the winged woman. The winged Victory is a topic figure. But cf. Pensa 1977: 47.

15. Burkert 1969: 11 n. 25; Orph. fr. 233 B. = 158 K., trans. W.K.C. Guthrie. The passage has echoes in Parm. B1.14 D-K: τῶν δὲ Δίκη πολύποινος ἔχει κληῖδαςἀμοιβούς, “And Justice, bringer of retribution, holds the keys, which allow her to open first one gate then the other”; cf. also Bernabé 2004b: 54-57, 129.

16. Ps.-Demosthenes 25.11 (Orph. fr. 33 B. = 23 K.), trans. J. H. Vince. About Eunomia, cf. Hes. Theog. 902; Solon fr. 3.32 Gent.-Prato; Pind. O. 13.6, B.13.18, 15.55; Orph. fr. 252, Hymn. 43.2, 60.2.

17. We are also told about a sojourn of the pure in Thur. (489-490) 7, and specifically about a meadow, Thur. (487) 5, in addition to Pind. fr. 129.3 Maehl. (in a fragment with probable Orphic influences; cf. Bernabé 1999a); Pherecrates fr. 114 K-A; Aristoph. Frogs 449; Synesius Hymn. 3.394ff. The image of the meadow is not alien to Platonic eschatology. In a series of passages with a possible Orphic influence, we are told that the judges pronounce the definitive sentence in the meadow, where two roads start—one leads to the Island of the Blessed, and the other to Tartarus (Pl. Gorg. 524a)—or that the souls have to stay seven days in a meadow before going to Necessity and the Parcae and finding a new fate (Pl. Rep. 616b). But the philosopher seems to have innovated; cf. §11. About the Orphic signification of the presence of Dike in the Apulian pottery, cf. Pensa 1977: 7-8; about δίκη among the Orphics, cf. Jiménez San Cristóbal 2005.

18. Pet. 11: ἄ[λλοισι μεθ’] ἡρώεσσιν ἀνάξει[ς], “You will reign with the other heroes”; cf. Ent. 2: μ]εμνημέ〈ν〉ος ἥρως;;; and note 9 above.

19. Thur. (487) 4:θεὸς ἐγένου ἐξ ἀνθρώπου, “You are born god, instead of a mortal”; cf. Thur. (488) 9.

20. Cf. Bernabé 1998a: 46; and Pl. Rep. 363c, where there is attributed to Musaios and his son (that is, to Orphic traditions) a doctrine, according to which the fair and the unfair and the impious have different fates in the underworld, as well as Pl. Gorg. 493a; Origen Contra Celsum 4.10, 8.48.

21. The contrast is outstandingly sarcastic, since this group of people has a very bad reputation, because of the procedures they used to collect.

22. Cf. Graf 1974: 81, 103-107, 141; Bernabé 1998a: 56.

23. The assertion that Orphic rites come from Egypt seems to be a sign of the attempt of the Ptolomean to associate Greek religion with the Egyptian one, and to favor religious syncretism. Cf. Díez de Velasco and Molinero Polo 1994, related to another reference by Diodorus Siculus (1.92.2), about the hypothetic Egyptian origin of Caron and his boat (these conclusions are, however, perfectly applicable to the passage with which we are dealing); cf. also Díez de Velasco 1995: 44 and n. 106; Bernabé 2000; Casadio 1996b: 205 n. 16, with bibliography.

24. Probably because they have only selected the information that is immediately useful for the initiate and also because it could be considered a bad omen to mention the possibility of failure in the moment of death. Cf. Bernabé and Jiménez San Cristóbal 2008: 232-233.

25. Janko (2001: 20 n. 85) brings up Protagoras’ book Περὶ τῶν ἐν Ἅιδου, quoted by Diog. Laert. 9.55 and Sext. Emp. Math. 9.66, 74.

26. Tsantsanoglou (1997: 110) understands that the commentator addresses the profane, whose punishments in Hades are evident, trying to convince them of the fact that only by purifying themselves and by initiation will they be able to achieve a happy life in the netherworld. Cf. Pl. Rep. 364b-365b, as well as Janko 1997: 68.

27. The reference to dreams probably alludes to nightmares suffered by certain individuals and considered as proofs of the real existence of torments in the netherworld.

28. We can read ]υστ[ in col. (maybe μ]υστ[-?).

29. Cf. also Procl. In Pl. Rep. 2.108.17 Kroll, in which, nine centuries later, we still find the association of the τελεταί with the terrors of Hades within a scheme, which seems to be the same: there are initiations associated with terrors, which have a cathartic effect, because they produce in the faithful a community with the divine, according to the idea that the divine is indescribable.

30. Aristoph. Frogs 145 (where we are told about “much mud and shit of eternal flow”), 273.

31. Aristid. 22.10; cf. also Plot. 1.6.6. About the topic, cf. Graf 1974: 103-107; Kingsley 1995: 118-119; Casadesús 1995: 60-63; Watkins 1995: 289-290; West 1997: 162 and n. 257. Other passages in which we are told about prizes and punishment in connection with Orpheus are Pl. Rep. 363c (Orph. fr. 4311, 4341 B. = 4 K.); Diod. Sic. 1.96.2 (Orph. fr. 55 B.); cf. also the symbolic interpretation by Pl. Gorg. 493a; and Bernabé 1998a.

32. The Munich Attic amphora with black figures (Beazley, ABV, p. 316) from the end of the sixth century BCE, in which are shown Sisyphus and some winged beings (the ancestors of the Danaids) that throw water into a big jar (Albinus 2000: pl. 4).

33. Cf. the commentary by Anne Burton 1972: ad loc., p. 279.

34. The instrument for the punishment, the sieve, maybe evokes the cause of suffering: the incapacity to separate the soul from the evil aspects. Cf. Harrison 1903: 604-623; and Bernabé 1998a: 76.

35. Sorel 1995: 107-108; cf. Burkert 1987: 91-92; Brillante 1987: 39; Riedweg 1998: 367 n. 33; Lada-Richards 1999: 90, 98-99, and 103.

36. We can ask ourselves if Plato points out this resemblance or if, rather, he ironically alludes to an etymology, which may be Orphic. The latter possibility will not surprise us, considering the great love of etymological games typical of the Orphic; cf. Bernabé 1999c.

37. Pher.: εἴσιθ〈ι〉 ἱερον λειμῶνα. ἂποινος γὰρ ὁ μύστης, “Enter the holy meadow. For the initiate has paid the price.”

38. Thur. (487) 5-6: χαῖρ〈ε〉, χαῖρε· δεξιὰν ὁδοιπόρ〈ει〉 / λειμῶνάς θ’ {ε} ἱεροὺςκαὶ ἄλσεα Φερσεφονείας, “Hail, hail, by taking the path on the right / toward the sacred meadows and the groves of Persephone.” The same meadow appears in a funerary epigram dedicated to someone called Aristodicus of Rhodes (AP 7.189.34), and in the Orphic hymn dedicated to Persephone, who is reborn in spring and is kidnapped in autumn (Orph. Hymn. 29.12, cf. 18.2). Λειμωνιάδες, a derivative of λειμών, describes the Hours, “partners in games of holy Persephone,” in Orph. Hymn. 43.3. Cf. also Orph. Hymn 51.4, 81.3, and the commentaries by Ricciardelli (2000a) on the quoted passages. A similar epithet, Λειμωνία, is assigned to Persephone in an inscription from Amphipolis (middle of the third century BCE); cf. Feyel 1935: 67. About the meadow in general, cf. Velasco López 2001.

39. Thur. (489-490) 7: ὥς μ{ει} πρόφ〈ρ〉ων πέμψη〈ι〉 ἕδρας ἐς εὐαγέ{ι}ων̣, “That She [Persephone], gracious, may send me to the abode of the blessed” (cf. Orph. fr. 340 B. = 322 K.). For this reason, the soul declares its purity in Thur. (489-490) 1.

40. Cf. also the description of the world of the blessed in Aristophanes’ Frogs.

41. Persephone’s sacred grove is already known to Homer and to other authors—for instance, Eur. HF 615. The echoes of this image even reach a Latin author as late as Claudianus (fourth century CE), who was much influenced by Orphism and describes in De raptu Proserpinae (2.287ff.) the goddess’s happy world as a pleasant place with groves and meadows.

42. I am referring to the images studied by Cabrera Bonet (1998).

43. From the same tomb where the Apulian amphora attributed to the Ganymedes painter (Fig. 6.8) appeared.

44. Cf. the quoted fragments of the ancient collection Fenicia (c. 350 BCE).

45. Thur. (489) 6: νῦν δ’ ἱκέτι〈ς〉 ἥκω παρ〈ὰ〉 ἁγνὴ〈ν〉 Φε〈ρ〉σεφόνε〈ι〉αν, “Now I come, a suppliant, to holy Phersephoneia.”

46. If we accept the extremely plausible corrections ἐρέουσιν (Lazzarini) and ὑποχθονίωι βασιλείαι (West). Maybe ὑποχθονίωι βασιλείαι was also in Ent. 16.

47. In addition to Hipp. 13, cf. Thur. and Pel.

48. Cf. Casadio 1994, in particular the evidence from Taras, Locris, and Sybaris.

49. Procl. In Pl. Ti. 3.297.3 Diehl; Simplic. in Cael. 377.12 Heiberg (Orph. fr. 348 B. = 229-230 K.).

50. Cf. Il. 9.457: ἐπαινὴ Περσεφόνεια, “awesome Persephone” (in other cases in Il. 9.569; Od. 10.491 534, 564, 11.47; Hes. Theog. 568). Only once (Od. 10.509) are the ἄλσεα Περσεφονείη (“groves of Persephone”) mentioned in a non-negative form.

51. For example, in the quoted passages Pl. Rep. 364e; Ps.-Demosthenes 2.5.11; Diod. Sic. 1.96.2-5; Procl. in Pl. Ti. 3.297.3 Diehl; Simplic. in Cael. 377.12 Heiberg.

52. Cf. Pensa 1977: 5-7, about the possible presence of Eurydice in some Apulian vases.

53. Munich, Antikensammlungen 3297, IV BCE fin.; cf. Pensa 1977: 23-24; Olmos 2008: 288-291, with bibliography (Fig. 6.6).

54. Pensa (1977: 37-46) offers a very interesting alternative interpretation of the Danaids.

55. According to Pensa (1977: 46), the little Eros between Orpheus and the woman confirms that she is Eurydice, but Eros has many different and important functions in Orphism; cf. Calame 1999: XI; Bernabé 2004a: frr. 64 and 65.

56. They coincide in this with other examined sources; see Pl. Phd. 69c, Gorg. 493a, Rep. 364e; Iulian. Or. 7.25; Plut. fr. 178 Sandbach.

57. The mystēs is called ὄλβιε in Thur. (488) 9 and τρισόλβιε in Pel. 1.

58. Iulian. Or. 7.25 talks also about “dwelling with the divine beings.” Cf. the “holy visions” of Plut. fr. 178 Sandbach.

59. If we have to read in line 2 μ]εμνημέ〈ν〉ος ἥρως, “Hero that remembers”; cf. Bernabé 1999b.

60. Thur. (487) 4: θεὸς ἐγένου ἐξ ἀνθρώπου, “You are born god, instead of a mortal”; Thur. (488) 9: ὄλβιε καὶ μακαριστέ, θεὸς δ’ ἔσηι ἀντὶ βροτοῖο, “Happy and most blessed one, a god you shall be instead of a mortal.” Scarpi (1987: 200ff.) has pointed out the difference in the use of tenses: “You will be god” projects deification into the future, in contrast to “You are already god,” now, as a consummated fact, maybe the result of the experience never lived before. In Rom. 3 we read: Καικιλία Σεκουνδεῖνα νόμωι ἴθι δῖα γεγῶσα, “Come, Cecilia Secundina, legitimately converted into goddess.”

61. Cf. the reference of Hdt. 4.94 to Zalmoxis’ followers. In the Hellenistic period only, the deification of the dead is integrated within the frame of official religion, but as a privilege reserved for the sovereigns.

62. Scarpi (1987) compares the situation of the souls of the initiates with that of the Hesiodic men of the golden age (Hes. WD 109-126), who, when the Earth hides their bodies, become demons, guardians of justice, and of givers of wealth.

63. García Teijeiro (1985: 141) considers turning the meadow into the place where the judgment of the souls was celebrated to be a Platonic innovation; cf., from a different point of view, Bañuls Oller 1997: 10-12.

64. Cf. Puhvel 1969; Motte 1973: 247; García Teijeiro 1985; Velasco López 2001: 136-144.