Due to the extremely limited number of literary sources, which are often merely scholiastic or hypomnematic documents providing scarce information, our reconstruction of the religious panorama of Magna Graecia, like that of Sicily, remains largely based on archaeological, monumental, and epigraphical evidence. We need not stress the importance of this documentation, insofar as it bears direct witness to the specific local realities, nor do we need to mention the difficulties and risks at times involved in its historico-religious exegesis. Such risks are even greater when we try to deal with monumental complexes that, due to the absence of explicit identifying elements (in a few lucky cases we have dedicatory inscriptions), leave us more or less uncertain regarding their association with one cult or another. The very structure of the religious horizon in Magna Graecia and Sicily, with its peculiar Greek-style polytheistic features, characterized by the departmentalization of divine figures and their respective sphere of influence, but also — at the same time — by the possibility of associations and convergences between them, leads scholars to be extremely cautious in circumscribing and defining the sphere of divine action and of the respective cults in relation to archaeological evidence. There do exist, however, some special cases for which the significant frequency of the emergence of sufficiently homogeneous and peculiar documentary contexts from a monumental point of view, throughout the area of Greek cultural and religious influence, makes it possible with reasonable confidence to identify the divine personality to which they are linked and their underlying ritual praxis. This in fact is the situation for the many sacred sites recognizable as dedicated to the Demeter cult and in particular associated with that characteristic ritual praxis that literary and epigraphic sources call Thesmophoria. Without being able here to dedicate space to a description of a phenomenon that is in any case well known, it is sufficient to mention that in the wide-ranging and varied panorama of Greek religious tradition, in terms of antiquity and pan-Hellenic diffusion, a major role was played by cults to Demeter Thesmophoros, named according to a common use of Greek liturgical language in the form of the neutral plural, τὰ θεσμοφόρια, that is, the “Thesmophoria.”1

Among the peculiar characteristics of these cults, in addition to being strictly esoteric and reserved for women,2 there is on one hand the mesh of qualified relationships between the mythical and ritual plane, and on the other the type of sacred space in which the latter is situated.3 The literary sources, while of varying documentary value in relation to their age and provenance, testify to the existence of a fairly specific connection between the cult actions performed by the Thesmophoriazousai, that is, the women who celebrate the rite, and a primordial crisis involving Demeter and her daughter Kore-Persephone, who is ritually evoked in the Thesmophoria context. To use the definition of Clement of Alexandria, the women who celebrated the Thesmophoria performed a sacred festival evoking the divine event, narrated in the myth (τὴν μυθολογίαν . . . ἑορτάζουσι), to which he briefly alludes by mentioning

Pherephatta’s flowerpicking, her kalathos, and her rape by Aidoneus, and the cleft in the earth, and the pigs of Eubuleus that were swallowed up together with the Two Goddesses, according to which aetiology the “megarising” women at the Thesmophoria threw in pigs. This myth the women celebrate variously in festivals around the city, Thesmophoria, Skirophoria, Arrhetophoria, acting out the rape of Pherephatta in many ways.4

This event substantially corresponds to that described in the pseudo-Homeric Hymn to Demeter, which, however, is specifically Eleusinian, explicitly linked to that peculiar religious structure which were the mysteria, namely the esoteric initiation rites celebrated only at the sacred site of Eleusis.5 The mythical theme in question is reflected in extensive literary documentation, with more or less significant variations often linked to local traditions and cults, including, in fact, some of a Thesmophoria nature. These are Hades-Pluto’s abduction of Kore-Persephone, her Mother’s grieving and search for her, and the Daughter’s return, albeit only periodically, which brings an end to Demeter’s grief, with positive consequences for humanity. In particular, they represent the restoration or foundation of the agrarian rhythms of cereal farming and thus of chthonic fertility, a guarantee of continued survival for men and animals.

These mythical events are articulated within a cosmic scenario, implying a series of movements of the protagonists not only in a vertical perspective (descent of Demeter from Olympus, ascent of Hades from the underworld and his katabasis with the abducted maiden, return of her to her Mother on the earth and then together with her to the heavenly dwelling), but also horizontally (Demeter’s wandering over the earth looking for her Daughter, and her many xeniai at human hosts). This creates a sort of mythical “cartography” involving the three cosmic levels but whose fulcrum is the earth. It is, in fact, here that the vectors of action of the deities come into contact and conflict (Persephone picks flowers on a plain, from which emerges Hades’ chariot, only to plunge back down into it; the earth is journeyed over by a mourning Demeter, is made sterile by the angered goddess, then once more blossoms with Persephone’s re-emergence from the underworld). The divine event and its “geography” involve the human dimension, which in turn is actively collocated in the “space” and time of myth through ritual practice and the definition of the sacred space in which this unfolds.

De facto, the sacred site, the Thesmophorion, presents some typical structural connotations that—although we should take all the precautions necessary in the exegesis of the individual monumental complexes—often clearly indicate its identity as a center of the Demeter cult. The typical elements that combine to help identify a Demeter Thesmophoros scenario are an extramural location,6 a site in an elevated position (on high ground or hillsides), proximity to water (seashores or riverbanks), and—less often archaeologically verifiable even if often mentioned by ancient sources — the presence of natural or artificial underground cavities (the megara).

There naturally exist many variables in this scenario, as can be seen in the passage quoted above, when Clement of Alexandria stresses that the women celebrate their festive rites connected to the mythical theme of the abduction and search for Persephone ποικίλως κατὰ πόλιν (which can be translated not only as “variously in festival around the city” but also as “in different ways from city to city”) and mentions, alongside the Thesmophoria, other ceremonies such as the Skirophoria and Arrhetophoria,7 which the sources also connect to the sphere of Demeter. In any case, the data evoked recur with significant frequency in the archaeological contexts identifiable with certainty or good approximation as Thesmophoria, or are illustrated as such by the relevant sources. It can be seen from this that the Thesmophoria and the numerous similar cult centers identifiable in the area in which Greek religious history unfolded8 imply a qualified relationship between the symbolic organization of the ritual space and the specific mythical parameter to which the ceremonies performed there are linked. Much more important, then, is the contribution of archaeological evidence to the historico-religious knowledge of the widespread and articulated mythical-ritual Demeter sphere, relatable to a varying extent to the Thesmophoria, as is illustrated by the literary sources. At the same time, the many “variables” that this evidence displays in the different regions of the Greek and Hellenized world confirm the continuous adaptability of this sphere to local realities, differentiated over time and in their respective historico-cultural referents. More widely, they illuminate the flexibility of the religious model represented by Greek polytheism, in its peculiar dialectic between general structures of a pan-Hellenic dimension and local “inventions,” linked to the various communities and relative traditions composing the variegated scenario of the peoples that saw themselves as Hellenes, due to community of language, customs, and religious traditions (cf. Hdt. 8.144.2).

In this background, it is possible correctly to collocate the historico-religious exegesis of the wide-ranging material that has come to light in recent years in the chora of Poseidonia-Paestum, in San Nicola di Albanella, and that is now fully accessible to critical study, after preliminary information9 provided in M. Cipriani’s excellent and methodologically exemplary monograph.10 It is part of an articulated framework of Demeter presences that archaeological investigation is revealing to be increasingly wide and rich, with local peculiarities, not only in the area of Paestum11 but in Magna Graecia as a whole.12 This has led us to reappraise that impression of marginality which once seemed to characterize the pan-Hellenic personality of Demeter in this region, compared to the extensive evidence of major cults in the ancient sources associated with important sanctuaries, such as those of Hera in Poseidonia13 and Crotone14 or of Persephone in the grandiose complex of Mannella at Locri.15

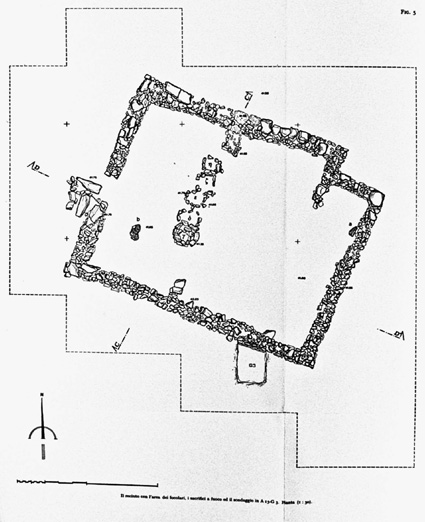

Without offering a detailed description of the site, impossible here as well as being superfluous to my ends, it is sufficient to consider the peculiar geographical situation of the sacred site, situated in a small valley 16 kilometers northeast of Poseidonia, in the northern section of the La Cosa River and dominated by the uplands of San Nicola and the Vetrale. This is thus a country environment abundant in water, perfectly in line with the whole series of Demeter Thesmophoros sites?16 The sacred area, which dates back to the fifth century BCE, consists of a dry-stone-walled enclosure (Figs. 8.1-8.3), perhaps with a partial or temporary roof, within which are situated fireplaces for sacrificial offers and a number of votive deposits, containing numerous miniature vases (skyphoi, kotyliskoi, one-handed cups, and krateriskoi) found turned over toward the ground, according to a custom reported in various Thesmophoria sanctuaries, and in particular at Gela Bitalemi, which, defined explicitly as such by a dedicatory inscription “to Thesmophoros,”17 is the closest and most specific parameter of comparison for the sacred site in question.18 In addition to ceramic cooking containers, bearing traces of fire as a witness to their use for communal meals inside the sacred area, the votive deposit in which all the material was sealed at the end of the fifth century BCE, when the religious activity of the small sanctuary seems to have ceased, has provided a rich series of votive terracottas displaying various iconographic typologies. These represent one of the most significant elements of the entire context from the historico-religious perspective and confirm a specifically “local” component of the cult practiced there, explicit clues of which were already provided by the many choroplastic items coming from votive offerings of the region of Paestum or other sites in Magna Graecia.19

Figure 8.1. The enclosure with the area of the hearths, the sacrifices by fire. Fig. 5 Cipriani.

Figure 8.2. The enclosure after excavation seen from the east. Tab. 5 Cipriani.

Figure 8.3. The hearths b, e, g. Tab. 8a Cipriani.

This region has moreover been identified as the origin of the icono-graphic motif. Alongside a rich group of fictile statuettes of various sizes showing a female character wearing drapes, with a high polos, carrying a piglet (Figs. 8.4-8.7), and sometimes a large cista or a patera or plate with objects identified as cakes,20 according to a popular iconographic pattern that probably originated in ancient Gela, there is a smaller but nevertheless significant number of fictile representations of young men with similar attributes (see Figs. 8.9-8.13 below).21

The female figures in question may be interpreted as images of offerers, even if in many cases we may justifiably suspect an alternative or perhaps intentionally ambiguous meaning, such as representations of the titular deity of the cult (Fig. 8.8),22 or, in the cases of ascertained or probable Thesmophoria identity of the cult context, of Demeter herself carrying the animal and considered as the speaking emblem of the essential ritual act. The entire documentation, from Aristophanes’ Thesmophoriazousai to a well-known scholion of Lucian’s Dialogues of the Courtesans, highlights the central role played by the bloody rite in the form of sacrifice of the animal for food23 and in that entirely peculiar action of the megarizein, that is, of throwing the piglets in underground cavities called megara. Lucian’s scholion,24 rather late but probably depending on a source of the first century BCE, reveals with great expressiveness a scenario of a secret female rituality from which, sources agree, men were barred. Any indiscreet curiosity on their part put them at the risk of terrible punishments, as recounted in well-known mythical and historical episodes.25 The passage deserves to be remembered, since, while it confirms that dialectic relationship of the Thesmophoria cult with the mythical horizon of the primordial divine event, already evoked in the text of Clement of Alexandria, it mentions a male figure explicitly linked to the very act of the megarizein. The text then reads?26

Thesmophoria: a festival of the Greeks encompassing mysteries, also known as Skirophoria (Θεσμοφορία ἑορτὴ Ἡλλήνων μυστήριαπεριέχουσα, τὰ δὲ αὐτὰ καὶ Σκιροφορία καλεῖται). It was [or “they were”] held, according to the more mythological explanation, because [when] Kore, picking flowers, was being carried off by Pluto (ἤγητο δὲ κατὰ τὸνμυθωδέστερον λόγον, ὄτι [ὄτε] ἀνθολογοῦσα ἡρπάζετο ἡ Κόρη ὑπὸ τοῦΠλούτωνος), one Eubuleus, a swineherd, was at the time grazing his pigs on that spot, and they were swallowed up together in Kore’s pit (τότε κατ’ἐκεῖνον τὸν τόπον Εὐβουλεύς τις συβώτης, ἔνεμεν ὗς καὶ συγκατεπόθησαντῷ χάσματι τῆς Κόρης); wherefore, in honor of Eubuleus piglets are thrown into the pits of Demeter and Kore (εἰς οὖν τιμὴν τοῦ Εὐβουλέωςῥιπτεῖσθαι τοῦς χοίρους εἰς τὰ χάσματα τῆς Δήμητρος καὶ τῆς Κόρης).

Figure 8.4. Statuette of female offerer with piglet: Type A I. Tab. 16 Cipriani.

The rotten remains of what is thrown into the megara below are recovered by women called “dredgers” who have spent three days in ritual purity and descend into the shrines and when they have recovered the remains deposit them on the altars (τὰ δὲ σαπέντα τῶν ἐμβληθέντων εἰς τὰμέγαρα κάτω ἀναφέρουσιν ἀντλήτριαι καλούμεναι γυναῖκες καθαρεύσασαιτριῶν ἡμερῶν καὶ καταβαίνουσιν εἰς τὰ ἄδυτα καὶ ἀνενέγκασιν ἐπιτιθέασινἐπὶ τῶν βωμῶν). They believe that anyone who takes some and sows it with their seed will have a good crop (ὦν νομίζουσι τὸν λαμβάνοντα καὶτῷ σπορῷ συγκαταβάλλοντα εὐφορίαν ἕξειν).

They say that there are also serpents below about the pits, which eat up the great part of the material thrown in; for which reason they also make a clatter whenever the women dredge and whenever they set those models down again, so that the serpents they believe to be guarding the shrines will withdraw.

The same thing is also known as Arrhetophoria and is held with the same explanation to do with vegetable fertility and human procreation. On that occasion, too, they bring unnameable holy things fashioned out of wheat-dough: images of snakes and male members. And they take pine branches because of that plant’s fertility. There are also thrown into the megara (so the shrines are called) those things, and piglets, as mentioned above—the latter because of their fecundity, as a symbol of vegetable and human generation, for a thanksgiving offering to Demeter; because in providing the fruits of Demeter she civilized the race of humans. Thus the former reason for the festival is the mythological one, but the present is physical. It is called Thesmophoria, because Demeter is given the epithet “Lawgiver” (Thesmophoros), for having set down customs, which is to say laws (thesmoi), under which men have to acquire and work for their food.27

Figure 8.5. Statuette of female offerer with piglet and cist placed upon the shoulder: Type B I. Tab. 17b Cipriani.

Figure 8.6. Statuette of female offerer with piglet and cist placed upon the shoulder: Type B IIA. Tab. 18a Cipriani.

The text of the scholion, subject to numerous exegetic approaches since E. Rohde placed it at the disposal of the scientific community,28 is certainly the result of a complex tradition, with the intervention of one or more editors and epitomists. However, it seems to be related substantially to the Thesmophoria, despite the mention of two other festivals, both reserved for women, and one of which, the Skirophoria, was also dedicated to Demeter. We should note, together with the ritual’s nature as “fertility cult,”29 its strong “political” value, insofar as it is aimed at founding and ensuring the continuity and prosperity of the human group through “fair offspring” celebrated on the Athenian day of Kalligeneia, which are the prevalent values of Thesmophoria cults. In its intimate links with a dramatic divine event of the time of the origins, it evokes, together with the great figures of the divine realm (Demeter, Kore-Persephone, Hades-Pluton), a figure—the swineherd Eubuleus—who, despite his anthropomorphized guise, also has the traits of a superhuman figure, and in fact was offered the piglets thrown into the underground cavities.

Figure 8.7. Statuette of female offerer with piglet and cist placed upon the shoulder: Type D IIA. Tab. 21a Cipriani.

Figure 8.8. Statuette of female deity seated on throne, low polos on her head. She wears a chiton and himation; in her right hand she holds a phial and in her left a patera with pomegranates. Tab. 29 Cipriani (from the small votive deposit).

Our documentation often presents the couple of the Mother and Daughter linked, in a triad formula, with a male figure, a Zeus or a Hades, often designated by the euphemistic attribute of Eubuleus,30 in the context of cults whose identity as Thesmophoria is more or less evident. The literary and epigraphic sources that reflect this religious framework are at times confirmed by the presence of images of a male figure found in sites identifiable as places of Demeter’s cult. An example of this situation is found at Iasos,31 where a bearded figure with a high polos, cloaked and bearing a patera, evokes a divine personality of the type of Zeus or Hades, as opposed to the young image of offerer with a piglet, such as is found in the sanctuary of San Nicola d’Albanella. The latter, as has been noted, has more specific parallels in Greek contexts in Asia, such as Halicarnassus,32 and in Corinth, from whose Thesmophorion come statues of youths bearing on their chests animals, which are not clearly identifiable (Figs. 8.9-8.13).33 I should add, however, that the style of the statuette from Paestum is extremely similar to that of some images of youths found in the Demeter sanctuaries of Morgantina, which also provided, in the sanctuary in the north of the city, a dedication to a mysterious male figure called Elaielinos.34

If, then, the existence of a male figure of a divine nature in the Thesmophoria mythical-ritual context is fairly widespread and may represent a precise religious referent for the iconographic motif under discussion, in my opinion this latter probably reflects a cultic practice, that is, the presence of male offerers. This does not, however, exclude the divine referent, but rather is composed harmoniously with it. De facto, there are some known cases of Demeter cults with a significant male component, such as the sanctuary of Demetra Prostasia and Kore situated in the sacred wood (ἄλσος) at Pyraia, mentioned by Pausanias:

On the direct road from Sicyon to Phlius, on the left of the road and just about ten stades from it, is a grove called Pyraea, and in it a sanctuary of Demeter Protectress and the Maid. Here the men celebrate a festival by themselves, giving up to the women the temple called Nymphon for the purposes of their festival. In the Nymphon are images of Dionysus, Demeter, and the Maid, with only their faces exposed (τὰ πρόσωπαφαίνοντα).35

Figure 8.9. Statuette of male offerer with piglet held to chest: Type F IA. Tab. 24b Cipriani.

Figure 8.10. Statuette of male offerer with piglet held to chest: Type F IB. Tab. 24d Cipriani.

Figure 8.11. Statuette of male offerer with piglet in his right hand and arm held to his side: Type G I. Tab. 25a Cipriani.

In other cases, the men play a complementary ritual role, as Pausanias narrates of the sanctuary known as Misaeum, near Pellene:

It is said that it was founded by Mysius, a man of Argos, who according to Argive tradition gave Demeter a welcome in his home. There is a grove in the Mysaeum, containing trees of every kind, and in it rises a copious supply of water from springs. Here they also celebrate a seven days’ festival in honor of Demeter. On the third day of the festival the men withdraw from the sanctuary and the women are left to perform on that night the ritual that custom demands (καταλειπόμεναι δὲ αἱ γυναῖκες δρῶσιν ἐντῇ νυκτὶ ὁπόσα νόμος ἐστὶν αὐταῖς). Not only men are excluded, but even male dogs. On the following day the men come to the sanctuary, and the men and the women laugh and jeer at one another in turn (σκώμμασιν).36

Figure 8.12. Statuette of male offerer with piglet in his right hand and arm held to his side. The left hand held to the chest holds a plate of fruit: Type H IA. Tab. 26b Cipriani.

The ritual praxis described by Pausanias, unlike that of Demetra Prostasia, involves the contemporaneous presence of men and women in an initial phase of the rite, followed by a strict separation of the sexes with the celebration of a nighttime dromenon, exclusively for women, which we may justifiably recognize as a Thesmophoria ritual. This seems confirmed by the element of play, with verbal obscenities, peculiar to Thesmophoria contexts. The integration of the two sexes in the first and last phases of the Mysaeum ritual may find a parallel in the Sicilian festivals mentioned by Diodorus Siculus, which also lasted for a long time (ten days), with widespread popular participation and the exchange of skommata, although his accounts make no explicit references to separation of the sexes or practices reserved for women?37

Figure 8.13. Statuette of male offerer with piglet in his right hand and arm held to his side. The left hand held to the chest holds a plate of fruit: Type H Ib. Tab. 27a Cipriani.

A confirmation of the presence of men in contexts of an evidently Thesmophorian nature, in circumstances and ways that naturally remain unknown to us, comes also from archaeological finds from many Demeter cult sites, through male images, dedications, or objects connected to the male world. Among the various examples of Demeter sanctuaries that have given wide and qualified evidence of male devotion are Heraclea; the new foundation of the ancient Siris in Magna Graecia, where a sanctuary of Demeter Thesmophoros was found to contain many votive dedications made by men;38 and Fratte near Salerno. Among the various terracotta statuettes found in a votive deposit, there are many of male offerers with a pig.39 The case of the sanctuary of San Nicola di Albanella, however, entirely maintains its specificity. The iconographic model in question is to be identified as a local “creation” of the Paestum region. It seems to reflect an extremely peculiar religious horizon, of which it is impossible to measure all the significances, but which in any case vividly expresses an active and qualified male presence on a cultic level in a Demeter scenario with clear connotations of a Thesmophoria ritual. Probably, as in the case of the cult of Demeter Prostasia, this scenario will have involved a parallel, distinct, but complementary ritual activity of the two sexes. This confirms the richness and typical mobility of the Demeter mythical-ritual context, which, while clearly displaying on the one hand fundamental pan-Hellenic tendencies, on the other unfolds in a myriad of local expressions, creating a dense constellation of cults deeply rooted in the territory that were able to adapt to the various socio-cultural and religious situations of the numerous communities in the Greek world.

1. For a detailed description of the ritual practice and its mythical foundations, cf. Sfameni Gasparro 1986: 223-306. See also Parke 1986: 82-88; Chandor Brumfield 1981: 70-103; Versnel 1993: 229-288; Clinton 1996: 111-125.

2. A fresh look on the variety of religious rules of the women in classical Greece is offered by Dillon 2002. See also my previous contribution (Sfameni Gasparro 1991: 57-121).

3. An analysis of the theme may be found in Sfameni Gasparro 2000: 83-106. Cf. also Guettel Cole 1994: 199-210 (reprint in Buxton 2000: 133-154).

4. Βούλει καὶ τὰ Φερεγάττης ἀνθολόγια διηγήσωμαί σοί καὶ τὸν κάλαθον καὶτὴν ἀρπαγὴν τὴν ὑπὸ Ἀιδωνέως καὶ τὸ σχίσμα τῆς γῆς καὶ τὰς ὖς τὰς Εὐβουλέωςτας συγκαταποθείσας ταῖν θεαῖν, δι’ ἣν αἰτίαν ἐν τοῖς Θεσμοφορίοις μεγαρίζοντες χοίρους ἐμβάλλουσιν Ταύτην τὴν μυθολογίαν αἱ γυναῖκες ποικίλως κατὰ πόλινἑορτάζουσι, Θεσμοφόρια, Σκιροφόρια, Ἀρρητοφόρια πολυτρόπως τὴν Φερεφάττηςἐκτραγῳδοῦσαι ἁρπαγήν: Clem. Alex. Protr. 2.17 (Marcovich 1995: 26).

5. Cf. Sfameni Gasparro 1986: 29-134, with relevant documentation. Among later contributions, cf. Clinton 1987: 1499-1539; 1988: 69-79; 1992; 1993: 110-124.

6. Therefore, this is only one of the three patterns of sanctuary location for Demeter cults, as noted by Guettel Cole (1994: 199-216, reprinted in Buxton 2000: 133-154). The sanctuaries of Demeter, in fact, may also be located between the walls of the city and the country or placed within the walls, even on the acropolis, as in the case of Thebes. The problem of the extramural location of some cult centers and of their probable characteristic as privileged meeting places for Greek colonists with the indigenous populations has been dealt with and variously solved by scholars. Here I would like to mention only, apart from Hermann’s rather schematic classification (1965: 47-57), the analyses of Vallet (1968: 67-142), Ghinatti (1976: 601-630), and Pugliese Carratelli (1988b: 149-158). A sociological interpretation of the relations between the Greeks and local people that takes into account the changes in the historical situation is proposed by Torelli (1977a: 45-61). Asheri (1988: 1-15) opportunely proposes the possibility of various motivations, in relation to different times and places, recommending caution in interpreting the phenomenon, not limited to Magna Graecia and Sicily, but widely reported also in the motherland and in the colonies of Asia Minor. A detailed list of the extraurban places of worship in the Archaic age in Magna Graecia can be found in Leone 1998.

7. Cf. Chandor Brumfield 1981: 156-179; Sfameni Gasparro 1986: 259-277; Foxhall 1995: 97-110.

8. Sfameni Gasparro 1986: 285-307.

9. Cf. Ardovino 1986: 97-99; Cipriani 1988: 430-445; Cipriani and Ardovino 1989-90: 339-351.

10. Cipriani 1989.

11. A brief but clear overview of these presences can be found in Ardovino 1986: 91-102.

12. For Taranto and its territory, cf. Lippolis 1981; De Juliis 1982: 295-296: votive offering of Via Regina Elena (cf. Tab. XLVII.3-4: female figure with cross-shaped torch, piglet, and plate with fruit). For Locri, Sanctuary Parapezza, cf. Grottarola 1994; for Santa Maria d’Anglona (Matera), cf. Rüdiger 1967.

13. Cf. de la Genière and Greco 1990: 63-80; Tocco Sciarelli, de la Genière, and Greco 1988: 385-396. See a brief overview on the cults of ancient Bruttium in Sfameni Gasparro 1999: 53-88; 2002: 329-350.

14. For the cult of Hera Lacinia, cf. Giangiulio 1982: 7-69; 1984: 347-351.

15. Cf. Locri Epizefiri, ed. Barra Bagnasco 1977; Barra Bagnasco 1984. Among the numerous studies on the terracotta tablets with religious scenes, see Prückner 1968 and Torelli 1977a: 147-184. The complete publication of the pinakes is in progress. Cf. Lissi Caronna, Sabbione, and Vlad Borrelli 1999.

16. Cf. Sfameni Gasparro 1986: 223-338, for a detailed discussion of the theme accompanied by ample documentary exemplification. See also Kron 1992: 611650; Lissi Caronna, Sabbione, and Vlad Borrelli 2003 and 2007.

17. See the various reports of Orlandini 1966: 8-35; 1967: 177-179; 1968: 1766; 2003: 507-513. A graffito on a fifth-century Attic vase fragment is a dedication “to the Thesmophoros from the skanai of Dikaios.” On other fragments of Attic skyphoi there are fragmentary inscriptions: DA … and (T)ESMOFOR…. The sanctuary of Demeter and Kore was in use from the mid-seventh century to 405 BCE, that is, up to the Carthaginian destruction of Gela.

18. The numerous and peculiar analogies between the two contexts have been highlighted by Ardovino (1999: 169-185), who made an in-depth comparative analysis and identified two correlated religious “systems” in the sites at Gela and Paestum.

19. Cf. Cipriani (1989: 119), who mentions similar types found at Fratte, Eboli, Capua, and Taranto (Winter 1903: 189, 5a-b).

20. Distinctions are made between a number of different types, which, however, are all considered to be based on prototypes from Gela analyzed by Sguaitamatti (1984). Cf. Cipriani 1989: 104-118. The typology identified by the scholar may be schematically summarized as follows: Section I: Plastic of medium size (100-103)—Type A: Female statue with piglet held to her chest; Type B: Idem with piglet in front of her bust, cist, and torch; Type C: Female head with cist. Section II: Small plastic—Type A: Female statue with piglet in front of her bust (see Fig. 8.4); Type B: Female statue with piglet in front of her bust and cist (see Figs. 8.5-6); Type C: Female statue with piglet in front of her bust and patera or plate with sweets; Type D: Female statue with piglet held head-down along the right side of the body and cist (see Fig. 8.7); Type E: Female statue with piglet held head-down along the right side of the body and patera with sweets.

21. Cipriani 1989: 118-128. Three main types have been identified, with minor variants: Group F: Male statuette with piglet held in front of the bust (see Figs. 8.9-10); Group G: Male statuette with piglet held head-down along the right side of the body (see Fig. 8.11); Group H: Male statue with piglet held head-down along the right side of the body and patera with sweets (see Figs. 8.12-13). All the types are dated to the mid-to-late fifth century.

22. This is the case of the female figures sitting on a seat or throne, which are most probably intended to represent the goddess, as in Figure 8.8.

23. The most explicit literary source on this use is an Aristophanes’ scholion: Schol. in Ranas v. 338: “He said this because in the Thesmophoria meat is eaten and since they sacrifice the piglet to Demeter and Kore … he said this since the piglet is sacrificed at the Thesmophoria” (τοῦτο εἶπε διὰ τὸ κρεοφαγεῖν ἐν τοῖςΘεσμοφορίοις καὶ ὅτι Δήμητρι καὶ Κόρῃ δύουσι τὸ ζῷον . . . τοῦτο δὲ εἶπε δὶ τὸχοιροσπαθεῖν τοῖς Θεσμοφορίοις). The archaeological documentation widely confirms this use. In addition to the site under consideration, it is sufficient to remember the highly significant cases of Bitalemi, with its rich votive deposits including a head of the animal, and Corinth, with its many banqueting halls. See White 1981: 24, with reference to Second report, LA 9 (1977), p. 172 pl. 74b: a stone statuette of a seated figure bearing a plate on which, among fruit or small loaves of bread, is found a piglet’s head, in an evident allusion to the sacrifice of the animal and to the consequent communal meal. Cf. White 1993.

24. For a recent discussion of the text, its chronology and authorship, see Lowe 1998: 149-173.

25. See, for example, the story of Battos, the founder of the city of Cyrene, who was said to have tried to profane the secret rites of Demeter and was thus subjected to the terrible punishment of eviration by the Sphaktriai, the priestesses in charge of sacrifices to the goddess. For an exegesis of this tradition, related by Elianus (fr. 44 Hercher) and confirmed in two entries in the Suda s.v. Θεσμοφόρος (“Demeter tesmophoros: Battos, the founder of Cyrene desired to know the mysteries of Demeter and used violence, rejoicing with greedy eyes”) and s.v. Σφάκτριαι (“Priestesses in charge of sacrifices: dressed in the sacred stole all the sacrificers, abandoned the sacrifice and raised their drawn swords, with their hands full and faces wet with the blood of their victims, all together on an agreed signal, leapt on Battos to evirate him”), see Detienne 1979: 185-214 (Italian trans. 131-148); Cosi 1983: 123-154.

26. Scholion to Lucian Dialogues of the Courtesans, ed. H. Rabe, Scholia in Lucianum (Leipzig, 1906), 275-276.

27. Translation by Lowe (1998: 165-166). Cf. also Chandor Brumfield 1981: 73-74.

28. Rohde 1901: 355-369.

29. This traditional definition is to be understood in the sense of a ritual praxis finalized to promote and to control the fertility of both the fields and the female citizens. This interpretation is proposed by Nixon (1995), who stresses the antifertility drug or pharmaka resulting from the use of some plants (pennyroyal, pomegranate, pine branches, and vitex) linked with the Demeter and Kore cults, both Eleusinian mysteries and Thesmophoria. These cults, therefore, are intended also to control human fertility.

30. Cf. Sfameni Gasparro 1986: 102-110.

31. Cf. Levi 1967-68.

32. These are ephebic images with a piglet, which, according to Cipriani, were wrongly interpreted by Higgins (1954: 130 and tabs. 64, 454-455 and 457) as female and from the early fourth century. See also the terracotta statuettes from a votive deposit in Gortina (Crete) in Platon 1957: 144-145.

33. Cf. Bookidis and Fischer 1972: 317: many fragments of statues. “All appear to depict a young man wrapped in himation, carrying an offering…. Best preserved is a statue of a draped youth,” which “date[s] to the late fifth or early fourth century B.C. (Pl. 63 a, b).” A terracotta mask depicting a bearded man was found east of the theater. Bookidis identifies the type as Dionysos-Hades (Bookidis and Fischer 1974: 290-291 pl. 59). Cf. the previous preliminary reports by Stroud 1965: 18, pl. 8 (terracotta figurines of small children, and several examples of the type of the “temple-boy”) and 1968: 325, pl. 95c, e (a standing, draped archaic kouros), pl. 95d (fragments of male figure). See also the final publication of the Corinth sanctuary by Bookidis and Stroud (1987).

34. Cf. the reports of the excavations by Sjôqvist (1958a, 1958b, 1960, 1962, 1964), Stillwell (1959, 1961, 1963, 1967), and Stillwell and Sjôqvist (1957).

35. Pausanias 2.11.3, ed. and trans. W.H.S. Jones (London and Cambridge, Mass., 1964), 304ff.

36. Pausanias 7.27.9-10, ed. and trans. W.H.S. Jones (London and Cambridge, Mass., 1961), 342ff.

37. Diod. Sic. Bibl. 5.3-4.

38. Cf. Neutsch 1968: 187-234, tabs. 1-33; Ghinatti 1980: 137-143; Sartori 1980: 401-415. The sanctuary of Iasos, which with every probability is also a Thesmophorion, due to the quality of the archaeological finds, has provided a significant number of fictile statuettes depicting a bearded male figure, with polos and patera, interpretable as a deity (perhaps Hades or Zeus Eubuleus), companion of the Thesmophoros goddesses. They illustrate a triadic formula common in many sites, above all in the Cyclades (cf. Sfameni Gasparro 1986: 91-110, 169-175). At the same time, these votive images could also reflect, with a particular relief of the male component of the divine sphere, a cultic role of the male element on the human level. Cf. the documentation in Levi 1967-68: 569-579.

39. Cf. Sestieri 1952: 126, Stratum XIX-XX.