Besides the Eleusinian mysteries, the late-fall pre-planting rites of the Thesmophoria were the most characteristic of the festivals of Demeter. The thesmophoria themselves, usually translated as “the things laid down,” were offerings flung into a natural crevice or man-made chamber in the rock known as a megaron, left to decay, and then retrieved and plowed into a nearby ritual field, thus securing the region’s fertility for the season to come. By metaphoric extension, the Thesmophoria became associated with the civilization that developed in the wake of sedentary agriculture, the “things laid down” being understood as a code of civil laws, the goddess’s title being translated into Latin as legifera, “law-giver.” A small temple just outside Rome, built by Herodes Atticus, can now be firmly identified as dedicated to Demeter/Ceres due in part to the recent discovery of a well-preserved megaron there. Herodes used the construction of this sanctuary as a gesture of synchesis linking himself to the goddess of laws in order both to exonerate himself of his wife’s bloodguilt and to increase his own social standing.

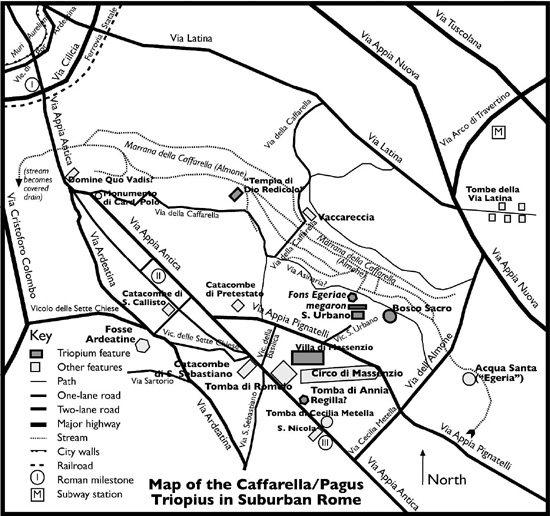

For those classicists unfamiliar with the field of cultural geography, I should explain that it functions as a sort of theoretical archaeology, specifically accounting for the placement of man-made features within the context of the natural environment—a system of both built and natural features commonly referred to as a “landscape”—by means of studying these features’ location, function, and meaning. Geographers often refer to this study as a “reading” of the cultural landscape, and its construction as “writing.” The implication is that we communicate cultural values such as wealth, status, and national origin by how we construct or “write” these systems. It struck me that a particularly felicitous subject for such a study might be a sacred landscape system “written” by the famous Greek sophist and antiquarian Herodes Atticus. I knew of such a site through reading Rodolfo Lanciani’s narrative of the remains of a sacred grove in the Almo Valley, south of Rome,1 and, given the opportunity to study it during a sabbatical semester spent in Rome from January to June 1993, determined to learn all I could. I carried out research both at the site in the Caffarella valley just off the Via Appia Pignatelli southeast of Rome’s Porta Appia (Fig. 9.1), and in the libraries of the Vatican and the American Academy at Rome. This body of information ultimately became the core of my Master’s thesis. With the help of my husband, Robert R. Lucchese, I was able to explore a series of caves and tunnels at the site that I identified, I believe for the first time, as a perfectly preserved thesmophoric megaron. I quickly shared my discovery with local archaeologists at their Via Campitelli office, and it was clear that they were as yet unaware of the existence of the megaron at the site. In the summer of 2000, I returned to the site and discovered a vent resembling a man-hole cover over the bailing hatch of the megaron. This suggests that some exploratory work has proceeded below, the extent of which I do not know. It is high time, however, that a wider audience of classicists was made aware of this uniquely complete temple complex, and perhaps that excavations begin.

Figure 9.1. Map of the Caffarella/Pagus Triopius in suburban Rome. By the author.

In reading landscapes, geographers often discover that their creators or “authors” have made figurative references, creating some higher symbolism at the site. This is especially the case, I would argue, when the landscape’s creator is in fact an author—in this case, a sophist, famous for his store of antiquarian references and clever figures of speech.2 The method by which Herodes Atticus seems to have evoked complex implications from this temple complex struck me as being like the trope of synchesis. In synchesis, nouns and their modifiers appear in a line of poetry in an interlocked word order, a-b-a-b, or, to use Clyde Pharr’s example from the back of the “purple Vergil,” saevae memorem Junonis iram (“fell Juno’s unforgetting hate”).3 The effect is for syntactically unrelated words to attract each other’s meaning in the reader’s eye and ear, so that unconsciously, they are linked: Juno with “hate” and “mindful” in a way that underlines her general state of mind in the Aeneid.

Synchesis seems to me to be a particularly fruitful figure for studying the sanctuaries of traditional “animistic” religions like those of Greece and Rome. Evocation of divine presences by a particular setting perceived as numinous is in itself synchesis, linking feeling to deity. One thinks of the awe-inspiring Shining Rocks of Delphi and their uncanny focusing of light and sound, their beauty and loftiness, their enclosure of the Kastalia spring, creating a natural focus of the numinous that became Apollo’s precinct. In the case of Herodes Atticus’ construction of the Demeter temple complex, the setting is natural enough, peaceful and enclosed, the soil fertile as only volcanic tuffs can make it (Fig. 9.2). But many symbolic linkages are also both made and exploited if already extant, linkages intended, as I argue, to improve the sophist’s status as well as symbolically to refute the suspicion that he had killed his wife.

In presenting this information, I follow a threefold scheme. First, I present the basic premise of Ceres as an “indigenous deity in Magna Graecia,” as the theme of this symposium would require. Then, I detail the ritual of the Thesmophoria and the landscape features it requires for its performance in terms of Herodes Atticus’ temple complex, within the context of the surrounding Pagus Triopius area.4 Finally, I return to the trope of synchesis in this sacred pagan landscape.

Figure 9.2. La Caffarella from the north side of the valley, on the bluff near the Vaccareccia farmhouse. Photo by the author, June 1993.

The indigenous Italic cult examined in this chapter is that of the great Italic goddess Ceres. Magna Graecia is here understood as extending northward (by Roman imperial times) to include Rome. Ceres seems to have provided the “increase” or growth function to the grain, the most mysterious and delicate aspect of farming: In The Roman Goddess Ceres, Barbette Spaeth traces the stem Cer- to the Sanskrit ker-, meaning “to create, to be born.” Spaeth additionally claims that Ceres has “the oldest written evidence of any Roman divinity.” She cites the inscription found at Falerii, dating to about 600 BCE:“Let Ceres give far. ”5 The “old-time” religious rites of the Arval Brethren, aimed at securing the peace and health of the Roman state, included prayers to Ceres paired with Tellus, goddess of the earth, in their celebration of the Cerealia on 19 April.6

The chief Ceres cult spot within the pomerium was the Aedes Cereris on the Aventine hill, founded after the great famine of 493 BCE. The Sybilline books called for the importation of her cult from Sicily, where the grain shipments also originated, complete with a priestess who continued to conduct all her rituals in Greek.7 While there was a distinctly Greek character to the pre-existing cult of Ceres in the city of Rome, it had some unusual local and typically Roman political linkages, quite different from those we will see made by Herodes. This temple was associated with the plebs: records of the Tribuni Plebis were kept here, and here Ceres formed a sort of plebeian triad with Liber and Libera (Italian equivalents of Dionysus/Triptolemos and Kore/Persephone) against the patrician Capitoline (and originally Etruscan) triad of Jupiter-Juno-Minerva.8 Thus there is a sufficiently early presence for the cult of Ceres in central Italy to call it “indigenous” by the time of Herodes Atticus, the Greek sophist whose importation of a very Greek version of the Ceres cult in about 170 CE is under consideration here.

By imperial times, all these deities had become uniquely entwined with local Roman culture, whatever their places of origin. Augustus, no less than his adoptive father Julius Caesar, placed himself firmly within the popular camp, wooing the impecunious but undeniably numerous plebs in part by identifying himself with the grain dole and thereby with the goddess who secured a continuing supply of that grain: Ceres (Fig. 9.3). By means of statues and coinage depicting his wife Livia in the guise of Ceres and himself in the Cereal crown of the Arval Brethren, Augustus implied that his own godlike charisma helped keep the plebeians fed, just as, less symbolically, he did in fact administer the system that provided the dole. From that time forth, Ceres was commonly paired with the emperor and his wife.9

Figure 9.3. Portrait bust of the emperor Augustus’s wife, Livia, as Ceres. Capitoline Museum. Photo by the author.

Walter Burkert calls the Thesmophoria “the most widespread Greek festival and principal form of the Demeter cult.”10 This is saying a great deal when one considers the modern fascination with the Eleusinian mysteries; it seems logical that the most frequent appeals to Demeter must have been for the yearly harvest and not for individual concerns about afterlife, a function additionally performed by other deities. Thus, the Thesmophoria were to be observed with regularity each fall, for a period of three days just before the fall planting in November (= 11-13 Pyanopsion). Whether the Aventine temple carried out these rituals is questionable, as they required the presence of a ritual wheat field, and Burkert does specify that they were common to suburban sanctuaries. The point of the ritual is clearly to provide some kind of sympathetic magic to assist the fertility of the whole season’s crop. By opening the planting season with the Thesmophoria, the rest of the region’s fields could be thought of as being blessed as well.

This ritual was strictly off-limits to men or to unmarried women; we are told that Athenian husbands were required by law to allow their wives to take part, and it would be very interesting to know what Roman laws were on the subject. Given the already greater freedoms enjoyed by Roman matrons over their Athenian sisters, one may assume that their access was not hampered by any special prejudice. How popular the Thesmophoria was among Roman women, however, is not clear, as we have no record of such performances at Rome that I have found, whereas we do read of the famous ritual of the Bona Dea—possibly a Latin equivalent of Ceres, with rituals similarly off-limits to men.11

The worshipers spent three days and nights camped out, as it were, at the sanctuary, the nights taken up with stories and songs, mostly lewd and thus bringing good luck, the days concerned with the retrieval of last year’s offerings, the proper treatment of these remains, and the production and insertion of new offerings. The hatch leading down into the megaron was unsealed, and one woman was sent first to scare away any snakes with noise or song, and perhaps to set up lamps like those found at the Demeter sanctuary at Knossos.12 Then the “bailers” descended into the chamber to scoop the remains of last year’s offering of piglets and cakes, known as megara or magara, into special baskets called kistai, which they put on their heads as they ascended once more into daylight. The kistophora figure is a standard representation of this part of the ritual, and several such statues, elegantly rendered in Hymettan marble, were found in the fields near the tomb of Cecilia Metella, off the Via Appia not far from the temple site (Fig. 9.4).13 The remains were then apparently offered to the goddess on the altar (possibly mixed with grain and hopefully accompanied by fragrant incense smoke) before being plowed into the adjacent sacred field. It would seem that this last chore must have been performed by a man, since it is so depicted in iconography representing the first farmer, Triptolemos.14

Figure 9.4. A Kanephoros or Kistophoros, carved from Hymettan marble and found near the Tomb of Cecilia Metella on the Via Appia in 1784. Now in the Braccio Nuovo of the Vatican Museums. Photo by the author.

Perhaps the blessed offering waited until the closing of the festival to be plowed, as there was still the new offering to be laid down, the whole point of the Thesmophoria. The “laying-down” was after all originally the application of the magical fertilizer of rotted piglets and cakes, scooped up from the megaron into the kistai, onto the sacred field, before the planting of the seeds. In preparation for the next Thesmophoria, new female piglets15 were dropped into the megaron along with cakes made into phallic and other appropriate shapes.16 Once the hatch of the megaron was resealed, the contents of the baskets plowed in, and no doubt the tidying of the sanctuary done, the business of the festival was complete.

Establishing as it does the preeminence of Demeter/Ceres as the bringer of agriculture to human society, the festival of Thesmophoria symbolized for thoughtful Greeks the coming of civilization itself.17 Once the realization of the full consequences to human society of the discovery and adoption of sedentary agriculture had been made, the thanks due to the great civilizer Ceres could properly be rendered. The very structure of civilization could be attributed to her arrival on the scene, just as civilization could collapse if she withdrew her favor. Sanctuaries recorded the results of her wrath: crop failures so radical that people were reduced once more to eating acorns, as in the troglodytic days, destroying the stratified fabric of society.18 Thus the “things laid down” of the festival were identified with human laws, laws that came about with the complexity of the urban society that agriculture made possible.

Proper keeping of the festival of Demeter Thesmophoros must have been important, then, not just to the continuation of agriculture in the form of the local wheat crop, but also to the continuation of urban civilization. The whole complex structure of civilization, after all, was based on the foundation of these particular laid-down things. The Latin translation of thesmophoros is the much less ambiguous legifera—“law-giver.”19 The Roman plebs could support Ceres’ worship in this sense as much as in that of the matron of the grain-dole; after all, it was protective institutions like the Tribuni plebis that began to protect the plebs from the arbitrary customs of the patricians. With a sense of her enlarged importance, the city fathers as well as the mothers could support the cult of Ceres as one of those to be honored above local deities, and beside the great sky-gods Jupiter and Juno, who brought not only supreme justice but also the rain and breezes to assist Ceres in the growth of the seed. Civic leaders could use their loyalty to Ceres to reinforce the favor not only of the distant Olympian goddess but also of the very tangible, and numerous, common people.

The lands known as Pagus Triopius or the Triopium belonged to the family of Annia Appia Regilla, the wife of Herodes Atticus at the time Herodes built the Ceres temple there. Although it well could have been named Pagus20 since time immemorial, it is clear that it is its association with Ceres that gave it the modifier Triopius. Triopas was a mythical Thessalian king who somehow offended Ceres, possibly by misappropriating materials for her temple.21 He fled to Caria, where he is said to have founded the Ceres sanctuary of Triopium, though traces of this sanctuary have not yet been found. The extent of ancient Pagus Triopius seems to have corresponded roughly to the lands between the Via Appia and the Via Latina from the Via della Caffarella to the Via di Cecilia Metella (see Fig. 9.1), or perhaps as far down the Via Appia as the Villa of the Quintilii, who were famous detractors of their neighbor Herodes, as he was of them.22 The part of this land that borders the little Almo (or Almone) River is now known as La Caffarella, after the Almo’s medieval name, Marrana della Caffarella.

In any case, at the death of his wife, Herodes dedicated this rich and extensive region, with any villages and farms upon it, to the exclusive use of the goddess Ceres, to Liber and Libera, the deified Faustina, and to the goddess of fertility and vengeance, Ops/Nemesis. This he declared in verse on two marble tablets, set up within Pagus Triopius, which fell into the hands of the Borghese family (see Figs. 9.5 and 9.6, and see the appendix here for the full CIG reference and translation). One of these (“of Marcellus”) is easily visible in the Greek inscription room of the Louvre Museum in Paris. These inscriptions warn all comers that this land is not to be used for any purpose but to honor the goddesses, or else Nemesis will take her revenge. The first, excerpted below, has no author attribution, but according to Jennifer Tobin23 may be the only surviving piece of writing by Herodes — the expert in ex tempore speaking, not literature:

3 Come here, both of you, that you may honor this rich place

4 In the neighboring suburbs of hundred-gated Rome,

5 Pagus, host to Triopa of the Grain [Demeter]

6 So that you may call it Triopea’s among the immortal gods.24

The assemblage of sacred structures within the temenos of the Demeter temple is quite complete. There is, of course, the little temple itself facing due east, the megaron, lying along its northern flank and also running due east-west, the sacral field in which the megaron lies, the remains of the oak grove on the hill just east of the temple, and the Fons Egeriae, just under the lip of the bluff to the northwest—seemingly unconnected, but I rather think part of the whole. Finally, there is the tomb or cenotaph of Regilla, once proudly fronting on the Via Appia, but now entirely vanished.

Figure 9.5. Inscription 1 from Visconti 1794.

Figure 9.6. Inscription 2 from Visconti 1794, “Of Marcellus.”

The temple was built of elegant second-century brickwork and once boasted a porch with two marble Corinthian columns in antis. Within the last few hundred years, however, this porch has been bricked in to prevent a collapse, as may be observed from the impressive crack that runs up the left face of the entablature (see map and Fig. 9.7). A glance at the plan (Fig. 9.8) shows that the interior is a single, barrel-vaulted room, lit by windows high in the end wall and one over the entry door. Stairs behind the apparently sixteenth-century church altar lead down to a tiny crypt (decorated with a Madonna and Child fresco). A very un-Christian marble altar stands to the right of the door as one enters: circular and wound about with a writhing carven snake (Fig. 9.9), it is inscribed in Greek as being offered to Dionysus by the hierophant, the standard appellation for one who has been an initiator at Eleusis.25

The statues of Faustina the Elder as Ceres, of Faustina the Younger as Libera, and of Annia Regilla in her function as priestess have all vanished from the temple.26 Remaining, however, is the original, well-preserved stucco decoration (Fig. 9.10) on the vault and upper walls of the cella, although the wall panels themselves were frescoed in the eleventh century with scenes from the lives of Christ, St. Cecilia, and St. Urbano, to whom the temple was rededicated at some early date. The stuccoes feature two friezes of trophies and a vault decoration of octagonal coffers with a central boss. This boss is decorated with two divine figures: a bearded male figure undraped to the waist and holding a bird in his hand, and a draped female figure, also with a bird (Fig. 9.11). If we can assume Jupiter and Venus as the attributions of these figures, these in addition to the friezes would seem to refer to Annia Regilla’s Trojan ancestry, as the gens Appia, along with many other patrician families, apparently traced their lineage back to Troy.

On the three oblique sides of the temple is a partial wall, perhaps for shoring up the higher ground behind it. Directly to the north of the temple is a small oblong field, level and currently kept free from briars, which one may assume is the sacral field for the first plowing. In this field, at an unknown distance from the temple,27 is the hatch to the megaron, now exposed to the open air for the first time in perhaps 1,500 years (Fig. 9.12a). The megaron beneath the hatch (Fig. 9.12b) also runs due east-west, and is square-cut out of the reddish tufa below. The ceiling is not far above the head, and one suspects the soft dirt of the floor has risen considerably since its time of ancient use. The chamber is perhaps 2 meters wide and 27 meters in length, at least to the point where there is a collapse or an in-filling, at the far west end (see plan, Fig. 9.13). The centrally located hatch (about 18 meters along the megaron) ascends perhaps 5 meters to the surface, also carved from the tufa and rectangular in cross-section, with toeholds chipped into the eastward surface. Before the opening was installed within the last ten years, there was a broken slab of white marble at what I imagine was the ancient ground level, with what seemed to be a rusted pipe or oil drum above that, all of which was sealed with earth.28 I did not dig in the soft matter of the floor, but I suspect that a thorough excavation of the megaron and careful study of the removed material might well produce piglet bones, to discover whether in fact the megaron was ever used for its primary function.

Figure 9.7. The exterior of S. Urbano, taken from the southeast; note the massive crack running from frieze to roof, no doubt necessitating the brick infill. Photo by the author, 1993.

Figure 9.8. Canina’s reconstruction of the interior of S. Urbano, in section crosswise (left) and lengthwise (right). The location of the boss showing the two deity figures on the vault has been marked and x’s indicate the location of the later Christian frescoes. Canina 1853.

Figure 9.9. An altar to Dionysus, either in its original position or found nearby and set within the church of S. Urbano. Piranesi 1780; Vatican Library listing: Cicognara XI.3837.

Figure 9.10. Stucco representations of weaponry at the spring of the vault of S. Urbano. Note the battle trophies and captured standards. Piranesi 1780.

Figure 9.11. Stucco boss in the center of the vault of S. Urbano, possibly representing Jupiter and Venus. Piranesi 1780.

Before the addition of the modern opening via the hatch, the only egress from the megaron after its entrance was sealed, no doubt after the peace of the Church, was through a tunnel that branches off its eastern end (see Fig. 9.13). This tunnel, of unknown age and function, is carved very differently out of the soft tufa: the ceiling and sides are curved rather than tall and straight-sided, like the megaron, with two broader chambers with alcoves of undefined purpose. Just at the point of exit into the open air, one comes to a wide, low, bifurcated hall, suggestive of a stable, with occasional shallow shelves one imagines to be used for lamps or fodder. It was by following a path up the bracken-covered hillside below the temple that I found the entrance to the tunnel and thence to the megaron; the entrance is invisible from below, and nearly invisible even from across the valley (see Fig. 9.1). Given the questing nature of the zigzag upper reaches of the connecting tunnel—turning back inward when the hill’s exterior support wall is reached—it must be that either the carver of the tunnel began from the hatch and cut a way out to a known cave, or the carver cut a way in to reach the known megaron. In either case, the simultaneous knowledge of both the cave and the megaron was necessary, it seems to me, for the connection to have been made, arguing for a very early carving of the extra tunnel, before the entrance to the hatch became obliterated, as it was when I first saw it.

Figure 9.12. Photos taken inside the megaron: (a) The hatch as viewed from directly below, with a fragment of a marble cover, above which was what looked like an oildrum. The toe-holds can be seen angling from left to right directly below the lid fragment; (b) The view from east to west of the megaron, where the entry to the hatch is just where the light of the flash fails. Photos by the author, 1993.

Figure 9.13. Rough plan of the megaron and tunnels and chambers connecting it with the slope of the hill, made by the author using a Silva compass and pacing system as indicated.

Figure 9.14. Photograph of the Bosco Sacro, taken at the end of the nineteenth century looking west toward S. Urbano. In 1993 there were only three trees in place, but many have been recently planted, as the area is developing into a city park. Domenico Anderson/ALINARI Archives, Florence (1890).

My chief reason for studying the Caffarella landscape was the continuing existence there of a sacred grove. This cluster of ilexes, standing upon the knoll just east of the façade of the temple, is sadly thinned from its former abundant state. In a photograph of the late nineteenth century, the temple stands stark without surrounding foliage while the grove looms dark and full (Fig. 9.14). Now, the temple is scarcely visible behind its pines, whereas only three slim specimens of ilex remain in their proper places (see Fig. 9.2). This is perhaps the very grove to which Juvenal refers when he mentions “trees inhabited by refugee Jews” beside the Fountain of Egeria.29 I myself have seen one of these trees with a rope ladder let down, in February, perhaps to let a cold shepherd take shelter from drizzle under the boughs.

A sacred grove is a standard accompaniment to a sanctuary of Demeter, as may be seen from references in Pausanias.30 As we have seen in the case of Triopas, the goddess can remove her benison if offended, sending man back to the acorns of the woods for sustenance, where he was before agriculture came into the world. This is the interpretation of the presence of an ilex wood before her temple in the Caffarella; orchard trees would clearly represent an extension of her benevolent domesticating power over nature, whereas oaks do quite the opposite. The use of oaks here is in keeping with the somber, admonitory text of Herodes’ boundary inscriptions.31

Egeria was the water nymph who gave the law to King Numa, and with whom he consorted on a nightly basis. She is understood to have been a wood-loving nymph, and she had a fountain also at Lake Nemi, in the sanctuary of Diana Nemorensis. She was imagined as living not far from Rome, but definitely in the countryside.32 Her spring is located at the base of the bluff upon which St. Urbano/Temple of Demeter stands (see again Figs. 9.1 and 9.2), and is a cool spot overhung with a great nut-tree, wildflowers, and brambles, opening off of the path that was once the Via della Caffarella (until it met a gate and turned left across the Almone toward the Vaccareccia) and may have been the ancient Via Asinaria (a quiet mule-road, parallel and downhill from the great Via Appia and across the stream from the Via Latina). Water still runs from an alcove to the left of the back wall whence it used to spring, from under a reclining male statue, possibly of Numa. The sides of the nymphaeum are lined with brick and set with niches; the vault is concrete with the imprints of slabs of stone, and floor is paved with squared stones (Fig. 9.15).

Through the dedication of the Triopium, Herodes makes a series of gestures on his own and his wife’s behalf, creating synchesis between themselves and the place, and between themselves and their imperial patrons. Let us remind ourselves of the facts about Herodes: he was an extremely wealthy sophist from Attica, an Aiacid, a priest at Athens of the Roman imperial cult, an antiquarian and tutor to M. Aurelius and L. Verus, a man of unstable temper and tyrannical leanings. His wife, Annia Appia Regilla,33 was a kinswoman of Faustina the Elder, wife of Antoninus Pius, a member of the ancient Appian gens, thus, as we have seen, a descendant of Aeneas of Troy. She was also a priestess of Demeter and mother of Herodes’ five children. Her death in premature childbirth, apparently after being beaten by a freedman on Herodes’ orders for a trivial offense, brought on a lawsuit for wrongful death by Regilla’s brother.34 Although his superior oratory won the day and he was acquitted of his wife’s murder, Herodes nevertheless additionally proceeded to dedicate all of his wife’s clothing to Demeter at Eleusis and her Triopium lands to the goddesses Demeter and Kore, as well as to the goddess of vengeance, Ops/Nemesis.

Figure 9.15. Canina’s rendering of the Fons Egeria, in many ways better than any modern photograph, since bramble growth prevents one from standing far enough back to do it justice. The water flow is now, however, from the farthest-in left-hand niche. Canina 1853.

Herodes nowhere explicitly states in any dedicatory inscription that he is innocent, or wealthy, or on good terms with the emperor’s family, but all of these statements are implicit in the relationships he sets up within the landscape of the Triopium. I here examine three basic relationships: the links between the cults of Demeter of Greece and Ceres of Rome, the links between Herodes’ family and the Roman imperial family, and the links between the expiation of blood-guilt and Herodes himself.

We have seen earlier in the barrel vault inside the Temple to Ceres/Demeter (the modern St. Urbano church) some well-preserved stucco reliefs (see Fig. 9.11). I have mentioned that along the frieze at the spring of the vault, we see a decorative collection of stucco trophies—shields, weapons, armor—and that on a boss at the apex of the vault are two divinities, one male, bearded and draped from the waist down, one female, fully draped. The male deity has a small bird of prey, possibly an eagle, perched on the back of his right hand. The female deity holds a small bird, possibly a dove, in a little sling on her right hand as she looks back over her left shoulder toward the god beside her. I submit that we see here depicted Regilla’s lineage: as a supposed descendant of Aeneas, she would be related to both Venus/Aphrodite (Aeneas’ mother) and Jupiter/Zeus (the father of Aeneas’ ancestor Dardanus). The arms on the vault thus can be the spoils of Aeneas’ Italian triumphs.

Yet this Ceres temple does more than celebrate Regilla’s heritage. By linking Roman Ceres with Demeter, Herodes sets up a synchesis between Roman and Greek historical glory. The Greek nature of the goddess is clear from the little cylindrical altar still protected inside the church (see Fig. 9.9), with its Greek hierophantic inscription. Herodes claimed that he could trace his ancestry back to the great Ajax Telamon of Aegina35 The loyalty, strength, and tragic end of the Iliad’s Ajax Telamon would have been known to all fellow antiquarians. Against this we have the hero Aeneas, himself loyal and long-suffering, who tragically lost his first wife in the conflagration of Troy. Can Herodes even be reminding us of this notable parallel: his own loss with that of Aeneas? With a character as fixated upon rank and glory as Herodes’, it is not impossible to imagine.

Then there is the remarkable choice of the location for the Ceres/Demeter temple on the brow of a hill, under which lay the Grotto of Egeria. By connecting the cult of Demeter with that of Egeria, Herodes makes yet another elegant sophistic link between the traditions of Greece and Rome. Egeria, the muse of King Numa, the lawgiver of ancient Rome and establisher of the Vestal cult, among others, can be compared with Demeter Thesmophoros, the lawgiver of the Greeks, very neatly indeed. Herodes’ ancestor Cecrops also formed a link, as we have seen, with the law-giving days of Athens, making him nearly divine himself and surely worthy to own the Fons Egeriae. As Numa descended into Egeria’s grotto for midnight communion, so the kistophorai descended into the megaron to retrieve the “things laid down” that will bring fertility to the crops and thereby structure to society, and Cecrops (half-man, half-serpent) had his chthonic connections—a neat piece of sophism.

As we have earlier seen, the connection between the imperial family and the “corn” supply was venerable by Herodes’ time. By taking upon himself the right to dedicate a temple to Demeter/Ceres and erect within it statues to both the reigning empress Faustina and her daughter as Demeter and Kore (Ceres and Libera), as well as to Regilla as Priestess/Hero, Herodes was reminding Rome rather boldly of his imperial connections. Not only was he hereditary chief priest, the archiereus in Athens of the imperial cult,36 he had, after all, been Marcus Aurelius’ and Lucius Verus’ rhetoric tutor in their boyhoods, and seems to have relished his (however temporary) rule over the future rulers of the world. There is something of the tyrant in Herodes, as the Athenians were heard to complain: namely, the impulse that caused him to use his great wealth in an imperial way, endowing Sardis and Olympia with public waterworks and attempting to cut the Isthmus of Corinth with a canal, as Nero had also tried to do37

Regilla is linked in synchesis with the imperial women: her statue shares space within the temple with theirs. Herodes reminds his audience that he is related to the imperial family through his wife. He is one of them, this seems to imply, a fellow member of the imperial family via his wife and earlier tutorship; he is in the big leagues, he can be as generous and magnanimous as the emperor himself, he can put empresses on pedestals of his own making. This is Herodes the tyrant, as charged by the Athenians.38

The final but most obvious linkage in the mind of anyone who had followed his trial for murder would have been Herodes and Ops/Nemesis, but no one who suspected his guilt would have believed him capable of such an audacious gesture. To dedicate all of his wife’s possessions and estates to the three goddesses, and especially to the third, Nemesis, would imply that those gifts were not tainted with murder. Tainted lands and goods would be unfit for such an offering, in which case the gift would be better dedicated to the underworld deities, or to Zeus the Lawgiver himself, or simply to the emperor. Herodes’ victory in the lawcourts was, after all, no guarantee of his innocence: with his cleverness at ex tempore speaking, how could he not have been victorious, whether or not he was actually guilty? His own famously exaggerated grief was a mark against him39 No, his self-chaining to disaster, the synchesis of his innocence to the dedication of Regilla’s property, was his last, best hope to be believed.

This bold stroke is at once the most important synchesis and the least convincing of them all. The prolix dedicatory inscriptions, their poetic preciousness, and the typically Herodean excess of his demand that no one use this land ever again on pain of the vengeance of Nemesis, combine with the dedication of the land itself to create the opposite of what Herodes intended. That is, the “I think he doth protest too much” feeling—which had long lived in the world before Shakespeare coined a phrase for it—is overwhelming. All it took was for the dangling disaster, the Damoclean sword that Herodes himself had set over his head by his hybris, to fall upon him, as it finally did at the end of his long life, to prove that he had in fact had a hand in Regilla’s death. Once again distraught, this time over the death of two adopted daughters—struck by lightning as they slept in a tower—he is said to have been extremely perfunctory in his respect toward Emperor Marcus in the tyranny lawsuit, as well as unforgivably poor in the delivery of his speech. He courted death, and was only saved by the grudging and over-used affection of the emperor toward his old tutor; Herodes rarely or never returned to Rome thereafter.

When Herodes married Annia Appia Regilla, he linked his Greek historical heritage to that of Rome, and further back, to Troy. More important for our interests were his linkages with the gods: himself to Demeter through the priesthood of his wife and the lands he dedicated in her name; his wife—as semi-deified hero—to the divine empress Faustina and her daughter; and the sacred landscapes of suburban Rome to those of Asia Minor and Greece. By adding his wife to the heroic pantheon and her lands to the gods, he also hoped to lay aside any suspicions that he was responsible for Regilla’s death, placing himself in the position of grieving innocent. How could he be other than innocent, if he called upon the dread goddess Nemesis herself to be satisfied with his offering?

By adding this piece of Latium to the sacred landscape of Magna Graecia, Herodes was participating in a long tradition of Greek colonization of Roman culture. Did the Romans resist this takeover of their spiritual heritage? There is no reason to think they did; the great gods that had saved Rome from disaster had come from afar to do so: the Magna Mater from Asia Minor, Aesculapius and Apollo from Greece, and now Ceres from Sicily. Roman “animism” was an exercise in accretion, and the Romans were great connoisseurs of antiquarian sophistry and reflected glory: in fact, of synchesis.

A. Greek Inscription from the Pagus Triopius (no. 1 in Visconti 1794; CIG 3:916, no. 6280) = IG 14.1389 (Kaibel) = IGRom 3.1155 (Moretti) = 146 Ameling. Inscriptions translated by the author from Visconti’s Latin rendering of the Greek.

1. O guardian of the Athenians, worthy of honor, Trito-born [Athena],

2. And you who watch over the works of men, Rhamnusian Plenty [Ops/Nemesis],

3. Come here, both of you, that you may honor this rich place

4. In the neighboring suburbs of hundred-gated Rome,

5. Pagus, host to Triopa of the Grain [Demeter],

6. So that you may call it Triopea’s among the immortal gods.

7. However that may be, when you have come to both Rhamnous and broad Athens,

8. Having left the sonorous halls of Father Zeus,

9. Thus you hasten to the vine abundant in grapes,

10. And the fields of standing corn, and the trees laden with fruit,

11. Consecrating the tender grasses, the herbage of the nourishing meadows.

12. For Herodes names this land sacred to you both.

13. As much as is enclosed with a wall running ‘round it,

14. Not to be altered by future man, and also to remain inviolate

15. Since truly Athena has nodded the terrifying helmet-crest

16. With her own immortal head lest anyone be permitted

17. To move a single clod or even a stone,

18. For indeed those exigencies are not at all to be overlooked by the Fates,

19. If anyone give injury to the sanctuaries of the gods.

20. Hear then, local dwellers, and neighboring farmers,

21. This place is sacred, for the goddesses are unchanging,

22. And are greatly honorable, and prepared to lend an ear.

23. Nor indeed should anyone ruin the rows of vines, or the groves of trees,

24. Or the herbage greening and growing with the much-nourishing moisture,

25. With an axe, which is handmaiden to black Hell,

26. Building a new tomb, or disturbing an old one:

27. It is not right (themis/fas) for the dead to lie in land sacred to the gods,

28. Save for that one who may be related by blood and from the posterity of him who has declared it:

29. For truly that is hardly improper, as the avenging god is well aware.

30. For indeed Athena lay King Erichthonios in a temple,

31. So that he might cohabit with the sacred things.

32. If these rules not be heeded by someone, if he does not obey them,

33. But despises them, this act will not turn back upon him without punishment,

34. But unlooked-for Nemesis, and the avenging demon who prowls about,

35. Will punish that fellow; truly he will always bring down perilous misfortune.

36. Nor indeed should he slight the great power of Aeolidan Triopa [Demeter]

37. By destroying the fallow lands of Demeter.

38. For you should all sufficiently fear punishment, and the notice here,

39. Lest the Triopan Fury follow.

B. Greek Inscription from the Pagus Triopius (no. 2 in Visconti 1794; CIG 3:916, no. 6280), labeled “Of Marcellus.”

1. Come here to the temple, women of Tiberside,

2. Bringing holy offerings of incense to the image of Regilla.

3. For she was of the line of wealthiest Aeneas,

4. The illustrious blood of Anchises, and of Idaean Aphrodite:

5. She came to marry a man from Marathon; however, the celestial goddesses

6. Honor her, both new Ceres and Ceres of old,

7. To whom is named sacred the effigy of a beautiful woman.

8. She indeed lives with the heroines

9. In the Isles of the Blessed where Saturn reigns;

10. For this reward is her lot for her goodwill;

11. Thus Jupiter has pitied her grieving spouse

12. Lying in bleak old age on his widowed couch

13. Since those dark, greedy Fates have snatched

14. The children from that worthy woman’s house,

15. A half part of the many: for two have so far survived their birth,

16. Infants, unknowing of evil, up to now utterly ignorant

17. That savage Fate has snatched away such a mother,

18. Before she could come to honored old age.

19. Henceforward Jupiter, solace to that man weeping inconsolably,

20. As is the Emperor, like Father Jove in appearance and counsel,

21. Jupiter indeed has sent his blooming consort [Ganymede],

22. Worthy to be carried by the Elysian breezes of Zephyr.

23. But he gave to the boy sandals having stars around the ankles,

24. Which they say also Hermes wore,

25. Then when he led Aeneas out of the Argives’ war,

26. Through the shadowy night. Truly he had shining around his feet

27. The health-giving orb of Lunary light.

28. This once upon a time the Aeneadans sewed on their shoe

29. A sign of honor for the noble sons of the Ausonians [Italians].

30. The ancient sandals, ornament of Tyrrhenian men,

31. Shall not spurn him, though a Cecropidan [Athenian],

32. Since he was descended from Herse and Hermes,

33. If indeed truly Ceryx was progenitor of Herodes Theseides [Athenian].

34. Because he is honored, and a consul elected in the usual manner,

35. And gathered into the kingly senate, where is the place of the Princeps.

36. Nor is there anyone in Greece nobler in respect to race or in respect to

37. Eloquence than Herodes, whom they also call the “tongue of the Athenians.”

38. For truly she was herself a beautiful descendent of Aeneas,

39. And a Ganymedean, and was the child of the Dardanians

40. And Erichthonidan Tros. You, however, if it pleases you, perform sacred rites

41. And sacrifice the victims: truly the business of sacred rites is not for the unwilling,

42. But if any desire to care for the hero shrine inspires pious men:

43. For she is not a mortal nor yet a goddess,

44. Therefore her fate is not the sepulcher nor yet the holy temple,

45. Not the honors appropriate to mortals or like those for the gods.

46. The monument is indeed like that of Athens,

47. Truly the soul remains near the scepter of Rhadamanthus.

48. This, however, is the likeness of Faustina, a pleasing one, set

49. In Pagus of Triopa, where of old she had ample plains

50. And the order of vines, and the fields set with olives.

51. Nor will the goddess, queen of women, spurn

52. The handmaiden of her own honor, and attendant nymph.

53. For neither did Diana when lovely Iphigenia was clinging to her throne,

54. Nor indeed did Athena look down upon Herse with a terrible glance,

55. Nor, in ordering Regilla herself to join the heroines of old,

56. Will the nourishing mother of great-souled Caesar deem her

57. Insignificant for the arriving chorus of demi-goddesses of old,

58. When it so happens that she herself is foremost in the Elysian chorus,

59. As is also Alcmene, and blessed Cadmeides [Semele].

1. Lanciani 1901, esp. the chapter “The Sacred Grove of the Arvales”; the photograph of the grove is on page 121.

2. Wright 1921: 209: Herodes asks of a certain neologism, “In what classic is that to be found?” and on 307 he is referred to as the “most famous of orators.”

3. Pharr [1930] 1964: 79, item no. 442.

4. The inscription from Pagus Triopius is found in L. Moretti, Inscriptiones Graecae Urbis Romae, vol. 3 (Rome, 1979), no. 1155 = no. 146 in Ameling’s monograph (cf. note 22 below).

5. Spaeth 1996: 1-2.

6. Warde Fowler 1971: 161.

7. Richardson 1992: 80-81. See also the discussion in Warde Fowler 1971: 255.

8. Spaeth 1996: 66-75. It is to Ceres, Spaeth points out, that the Tribunus Plebis is sacrosanct and thus it is to her that expiatory sacrifices must be made when a tribune is attacked. The implication is that such a violation endangers the city’s growth and health.

9. Richardson 1992: 81: the Ara Ceres Mater et Ops Augusta, consecrated in 7 CE, is a good example of this linkage of Ceres with Livia and Augustus.

10. Burkert 1985: 242. Unless otherwise noted, all details concerning the ritual of the Thesmophoria are drawn from pp. 242-247.

11. Richardson (1992: 59-60) refers to the temple of the Bona Dea, also on the Aventine hill. He credits Macrobius with the note that no men were allowed in the temple (Macrobius Sat. 1.12.20-26). The famous story of Clodius Pulcher’s invasion of these women-only rites in 62 BCE is from Plutarch’s Life of Julius Caesar.

12. A clay oil pedestal lamp with a broad circular channel and some sixty wicknozzles is illustrated in pl. 26 of Coldstream 1973.

13. The kanephoros pictured is listed in Guattani, Monumenti antichi, as having been discovered in 1784 not far from the Tomb of Cecilia Metella. Entry LXI refers to a Caryatide, while LXX, the pictured statue, is listed as Canefora. Inscribed on the basket of the statue were the names of the artists, Kriton and Nikolaos, Athenians, and naturally the statue was of the finest marble, probably from Herodes’ own quarries.

14. The iconography associated with the Thesmophoria, including details of Triptolemos/Eleusinus as first farmer plowing up the soil, is described in great detail by Eggeling in his Mysteria Cereris et Bacchi in Vasculo (in Pasquali 1735: 6-74). See also Simon 1983: 21, showing a frieze of the sacred plowing.

15. Female piglets were Ceres’ favorite offering. The porca praesentanea was sacrificed to Ceres, according to Varro (in Non. Marc., 163 Müller, cited by Spaeth 1996: 54), to cleanse a family at a funeral, especially when an inheritance was received; the porca praecidanea was sacrificed before the crops were harvested and in honor of a dead person whose burial might have been improper.

16. Burkert 1985: 242.

17. Pausanias mentions a temple of Demeter Thesmophoros on the road to Hermione as being in Theseus country, implying here as in other places in his narrative that the lawgiver Theseus and Lawgiver Demeter naturally might be found together. Cf. Pausanias 32.8.

18. At the “Black Demeter” worship site at Phigalia, in Arcadia (Pausanias 7.42.1-7), the sanctuary was in a cave; the goddess’s image had a horse head, out of which sprang a serpent and other images; the image wore a tunic to its feet, and held in one hand a dolphin, in the other a dove. The first image at the site had caught fire, at which point the fields became barren, and the Delphic oracle gave the following explanation: the Arcadians had been acorn-eaters, and had twice been nomads and fruit-eaters. The goddess had caused them to cease pasturing, and could cause them to begin pasturing again. Of worship at this site, Pausanias notes: “I offered no burnt sacrifice … I offered grapes and other cultivated fruits, honeycombs and raw wool, full of its grease.” No pigs, interestingly enough.

19. Ceres Legifera was an Italic deity credited with the division of the fields and settled living, so that men did not “wander here and there without law.” She is invoked at the plowing of the pomerium and at weddings, along with Jupiter. Cf. Spaeth 1996: 52-53.

20. OCD3, s.v. pagus, “term of Roman administrative law for subdivisions of territories, referring to a space … where there was no focal settlement.”

21. OCD3, s.v. Triopas, whose son Erysichthon was punished with unquenchable hunger.

22. Philostr. VS 165. The Quintilii claimed Herodes was always putting up marble statues everywhere. He answered them that it was his marble (he owned — and depleted—most of the Hymettan marble quarries in Greece), and he could do what he liked with it.

23. The best source in English on the life and times of Herodes Atticus is Jennifer Tobin’s excellent 1997 study. In German, the classic is Walter Ameling’s 1983 Herodes Atticus.

24. CIG 3:916, no. 6280; translation mine, from Visconti’s (1794) Italian rendering of the original Greek.

25. OCD3, 706: “Hierophantes, chief priest of the Eleusinian mysteries, was chosen for life from the hieratic clan of the Eumolpidae” — apparently one of Herodes’ many public offices.

26. They are referred to in the dedicatory inscriptions noted above and in the appendix here.

27. It is approximately 10 meters; the distance is hard to gauge, as a fence lies between the building and the hatch.

28. There was some variation in megaron shape. Burkert (1985: 243) refers to the few surviving examples of megara as consisting of, in one instance, a circular “well” leading down into a natural crevice (at Agrigentum), and of a rectangular pit with a roofed opening above ground level (at Priene). He also notes the presence of pig bones and marble votive pigs in a circular pit at the Demeter sanctuary at Cnidos.

29. Juvenal in Satire 3.10-20 also complains of the alterations made in the Fons Egeriae, in “caves so unlike nature,” and “marble to outrage the native tufa.”

30. At the same Arcadian “Black Demeter” site mentioned above, Pausanias describes “a grove of oaks around the cave, and a cold spring that rises from the earth” (Pausanias 8.42.12). Another grove-temple combination appeared at the sanctuary of “Mysian Demeter,” located near Pellene in Achaia, and founded, says Pausanias, by a man named Mysius, “who gave Demeter a welcome in his home.” As he says, “There is a grove in the Myseum, containing trees of every kind, and in it rises a copious supply of water from springs” (Pausanias 7.27.9).

31. There is in a downstairs room of the Capitoline Museum a decapitated column, reused as a milestone column by Maxentius (who was also, we should remember, cannibalizing Herodes’ villa for circus decorations), which Herodes had inscribed simply enough, in Greek and Latin: ANNIA REGILLA / WIFE OF HERODES / LIGHT OF THE HOME / WHOSE LANDS THESE ARE (CIG pars 33.875, no. 6184).

32. See OCD3, s.v. “Egeria,” which perpetuates this locational error.

33. Herodes’ full name was Lucius Vibullius Hipparchus Tiberius Claudius Atticus Herodes; Regilla’s was Appia Annia Atilia Regilla Caucidia Tertulla.

34. Appius Annius Braduas, Regilla’s brother, sued Herodes for her murder, the accusation being that Herodes had had his favorite freedman Alcimedon beat Regilla, who was then expecting their fifth child, so that she fell and died in a miscarriage. It seems typical of that unadmirable age that not only was Braduas’ attack couched in a speech praising himself and his family’s pedigree, but also that Herodes’ reaction, far from being that of a devastated husband who had deeply loved his wife, was simply to sneer at Braduas’ showy aristocracy, saying that Braduas wore his nobility on his toes—since aristocrats were allowed to wear special celestial decorations on their sandals (Philostr. VS 2.555 [Wright 1921]). This ugly debate is even echoed in the “Of Marcellus” inscription listed in the appendix, lines 23-37 holding most of the boastful references to “starry sandals” and ancestry.

35. Tobin 1997: 13-14.

36. Ibid.: 29.

37. Ibid.: 34.

38. Ibid.: 38-47.

39. Philostr. VS 2.557-559 (Wright 1921).