1

A WARY HANDSHAKE

Of course it was a dismal day. The sky was as leaden as the national mood. Washington, D.C., had suffered incessant storms that winter, and on March 12, 1861, the roads were sticky with mud from the latest squall. Nervous residents could not help comparing the gloomy weather to the turbulent politics threatening the country. Seven Southern states had left the Union since the election of Abraham Lincoln, forming a new Confederate States of America. The outgoing Buchanan administration had only halfheartedly defended federal property against the secessionists, and efforts to find a peaceful resolution to the crisis were faltering. Now it appeared that the new government was following the same uncertain path. “We are a weak, divided, disgraced people, unable to maintain our national existence,” the Republican magnate George Templeton Strong wrote in alarm. The New York Herald agreed. It was a “deplorable state of affairs,” complained its editors. “All joy, all hope, is fled.”1

Against this dreary backdrop a curious apparition appeared about midday. At the stolid, neoclassical War Department a large group of military officers in full-dress uniform was assembling, their gold-crested buttons and vivid sashes piercing the dull light. Falling into two columns, they lined up behind Secretary of War Simon Cameron and Lieutenant General Winfield Scott, the Army’s venerable chieftain. In perfect formation, they marched to the Executive Mansion along the tree-lined footpath that connected the two buildings. At the door Scott himself solemnly rang the bell. The United States Army had come to call on its new commander in chief.2

By one count, seventy-eight men paraded into the East Room. Such a large group overfilled the space and they began to snake around the perimeter in an undulating line. The officers were resplendent in dark blue frock coats, tall patent leather boots, gilt scabbards, and black-plumed hats. Set against the shabby yellow wall covering of the “nation’s parlor,” their presence was all the more splendid. It was a “spectacular exhibition,” noted one of the company; another observer thought he had “never seen an equal number of such fine-looking men in uniform.” They stood at attention, kid-gloved fingers lightly pressing the stripes of their trousers, silently awaiting the President. After a few moments, Lincoln entered, accompanied by several cabinet members. Some officers had been influenced by newspaper accounts to expect an afternoon of jesting, and now they were surprised. The man before them was as clumsy as his descriptions, but his face was deadly serious.3

The East Room of the White House, c. 1861–65

WHITE HOUSE COLLECTION

The new president had good reason to be grave. Since taking the oath of office on March 4, he had been confronted with multiple crises, sometimes on an hourly basis. Two days into the job, Lincoln learned that the Confederate Congress had called out 100,000 troops to protect its territory. The attorney general and the secretary of war had just informed him that there was no legal way to stop the shipments of arms reportedly being rushed to Charleston, New Orleans, and nearby Baltimore. Samuel Cooper, a New Yorker who had served for a decade as adjutant general of the Army, left his post on March 6 and headed straight for the Confederate capital—taking with him detailed knowledge of personnel, matériel, and federal intentions. On March 11 the rebel government adopted a constitution containing elaborate legal justifications for a separate nation. A delegation from that “nation” was in Washington at the moment, under instruction to establish “diplomatic ties.” Humiliation was in the air, as federal institutions unraveled and Southern sympathizers sniggered over everything from congressional defections to the disappearance of patent files. Worse yet, the country was broke. When Buchanan’s treasury secretary Howell Cobb followed his native state of Georgia out of the Union, he left the nation bankrupt.4

Most pressing was the question of whether to withdraw United States forces from Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor. This crisis had been transferred to Lincoln just hours after his inauguration. Since his election, occupation of the fortress had been an emotional flashpoint: a contest between the South’s angry belief that it was no longer governed by consent and Northern determination to protect Union prerogatives and Union property. On March 5 the War Department received a letter from the officer in charge of the garrison, Major Robert Anderson, stating that provisions were nearly exhausted and that Confederate leaders were blockading the harbor, forcing a showdown. Lincoln would have to reinforce the fort or retreat, with all the symbolism that implied.5

The news came as a shock, for Lincoln had wanted to move slowly, to buy time, allay passions, and reassure nervous Unionists south of the Mason-Dixon Line. As president-elect he had tried to downplay the crisis, terming it “artificial” and claiming there was “nothing going wrong.” Once he realized that something was going terribly wrong, and that matters had moved beyond cool reflection, he hoped the separatist fervor would burn itself out. His deliberative political style would prove a handicap, as every day the situation in Charleston became more perilous. While Lincoln temporized, South Carolina strengthened its defenses. Anderson told his superiors he needed twenty thousand soldiers to defend the fort, a number larger than the entire standing army. Now he impatiently awaited the President’s reply. “I thought the policy of this new admins. would have been developed by this time,” he complained the day before the Army reception, adding that Lincoln’s promise to “put the foot down firmly” against secession appeared easier said than done.6 In fact, the President was getting a swift lesson in the difference between a campaigner’s offhand remarks and the grim responsibility of actually leading the nation through perilous times. The dilemma had paralyzed his predecessor—though Buchanan later claimed he had stood ready to support Anderson, if only he had been asked. No matter how meek—or even traitorous—Buchanan’s inaction seemed, Lincoln now found himself hesitating in just the same manner. “Is it possible that Mr. Lincoln is getting scared[?]” wrote an influential Illinoisan. “I know the responsibility is grate; But for god sake . . . I don’t want to bequeath this damnable question to any posterity.”7

The Sumter situation was particularly tricky, for it was not just a question of defending a fort or robustly exerting executive authority. It was coupled with an urgent need to keep those slave states that straddled North and South in the Union. These “border states” included Missouri, the President’s native Kentucky, and the entire region surrounding the nation’s capital. Of these, Virginia was most significant, not only because of its proximity to Washington, but in terms of size, industrial output, and prestige. Maryland, whose communication lines linked the government to the rest of the nation, was also of critical importance. The ties that attached these states to the Union were fraying in March 1861, and their leaders made clear that any “coercion” against the South would result in those bonds being cut completely.

The tension between these two issues—the need to restore confidence in the border states, yet firmly uphold federal laws and national dignity—had, in fact, been a theme of Lincoln’s inaugural address. That had been a tense day, the proceedings clouded by rumors of Confederate insurrection or attempted assassination. General Scott had summoned all his imposing powers to ensure the new president’s safety, calling up hundreds of troops to guard the Capitol grounds and personally commanding the sharpshooters placed on adjacent roofs. Lincoln was not yet master of simple, compelling statements, and his long message attempted to placate hostility on all sides, while conceding nothing. Despite an emotional appeal to the shared history that bound together the American people, the laboriously crafted address received a mixed response, both North and South. “Never did an oracle, in its most evasive response, receive so many, and such various interpretations, as did the President’s inaugural,” observed the New York Times.8 Within the military it sparked general dismay. “Mr Lincolns inaugural came to day,” wrote an officer named William T. H. Brooks, who was stationed in Texas. “If it can appease or quiet the troubled waters it must bear a different interpretation from what I can give it.” At Fort Sumter, officers saw little in the speech to resolve either their dilemma or the nation’s. “We have just received the inaugural and from it we derive no hope at all that there will be any peaceful settlement,” wrote Assistant Surgeon Samuel Wylie Crawford, despairing that “so many qualifications” in the President’s words would undermine the address’s impact. Soldiers wanted to hear a simple declaration of intent, but this speech smacked of equivocation. “A steel hand in a soft glove” was how Major Samuel Heintzelman described it, a few days before stepping into the East Room to greet the President. “I fear it will lead to Civil War.”9

The Sumter issue pressed on Lincoln to the point that he was physically ill, losing sleep and suffering chronic headaches. Before the end of that tempestuous March, his wife reported he had keeled over from worry and fatigue. One of his aides referred to those days as “the terrible furnace time,” when public anxiety was stoked to the limit, and old patterns of governing melted away in the political fire. Lincoln wanted desperately to avoid appearing as stymied as Buchanan yet found himself unable to formulate a decisive policy. He later told Orville Hickman Browning, a Republican ally, that all the “troubles and anxieties of his life had not equaled” those he faced during the Sumter crisis.10

II

Lincoln was suffering from these intense pressures as he faced his finely arrayed officers, but there were other reasons for his distraction. He was new to this world of official events and was not particularly comfortable with the military. At his first levee, three days previous, an invitee noted how the President had gracelessly received the public in oversized white gloves “with much the same air & movement as if he were mauling rails.” Military niceties particularly confounded him. On March 8 he had hosted a similar group of naval officers, with an embarrassing outcome. Participants remarked that Lincoln was confused by the imposing ceremony, interrupting formal introductions several times to chat with casual visitors or sign papers. Before the end of the reception he abruptly ran off, leaving the officers to stand uncomfortably at attention while he searched for his wife, who wanted to see the display of gold braid. When a senior officer made a handsome speech, pledging allegiance to the beleaguered Union, Lincoln dismayed the company by not responding. “The interview was not at all calculated to impress us . . . and there were many remarks made about the President’s gaucherie, far from complementary to him,” noted a naval man.11

Despite his discomfort among the officers, Lincoln was not without military experience. In 1832 he volunteered with the Illinois militia when it was called out to combat the Sauk and Fox Indians. Those tribes, led by Black Hawk, had been tricked into moving from their ancestral lands but decided to fight for their territory.12 The Army was ultimately victorious against Black Hawk, but the campaign was a badly directed affair, marked by undersupplied troops, slipshod skirmishing, and missed opportunities. Lincoln saw little combat, though he did have enduring memories of camp deprivation and the unsavory burial of mutilated corpses. It was not, he later remarked, a war “calculated to make great heroes of men engaged in it.”13

The Black Hawk War also offered Lincoln his only opportunity to command soldiers. He was selected captain of his first company, an honor that gave him lasting pride. A number of his men remembered him as fair, frank, and companionable. His record of real leadership was more problematic. Accounts mention several situations in which he could not control his troops, who straggled, pillaged, and were sometimes unable to march on account of drunkenness. Captain Lincoln himself was disciplined for recklessly shooting off his gun. Called to organize a field formation for the minor purpose of crossing a fence, he could not command forcefully enough to direct his soldiers through the narrow gate. In his next company Lincoln was not elected captain. His difficulties reflected the unprofessional tone of the whole campaign, but they also foreshadowed problems he would have as commander in chief.14

Lincoln experienced army life at its worst during the Black Hawk War, but that was only part of his martial malaise. He shared the popular mistrust of a standing armed force, whose starched and steely-eyed commanders seemed a throwback to the hated feudal powers of Europe. As a congressman during the Mexican War he also spoke disparagingly of the military tradition of valor, calling it “an attractive rainbow, that rises in showers of blood—that serpent’s eye, that charms to destroy.” He again scorned the armed forces during an address to Whig supporters in 1852. Lincoln was then promoting Winfield Scott for the presidency, yet he ridiculed the high-blown military imagery that dominated the campaign. Recalling a local muster day, he mocked the pretension of militia leaders, exaggerating their uniform into “a paste-board cocked hat . . . about the length of an ox yoke . . . [and] five pounds of cod-fish for epaulets.” He went so far as to assign the citizen-warriors a cutting motto: “We’ll fight till we run, and we’ll run till we die.” Although he was agile in political circles, which relied on popularity and personal ties for success, Lincoln was never really at ease with military culture, or embraced its heritage of discipline and battlefield gallantry.15

Now, in the East Room, he uncertainly faced officers whose epaulets were not of codfish, but richly embroidered with gold and silver thread: emblems that in their eyes signified pride and sacrifice and honor. These were the very qualities the President would desperately need as the nation careened into war. If Lincoln appreciated the tradition and service represented by the martial decorations, however, he most certainly failed to communicate it to the men standing at attention.

At least part of Lincoln’s discomfort stemmed from his newly acquired role as head of the armed forces. Among the Constitution’s more problematic clauses is the single sentence that establishes the president as commander in chief of the Army and Navy. This stipulation is at once all-encompassing and vague; granting full responsibility, yet unspecific on the actual exercise of authority. Although the president is not part of the military establishment, he retains ultimate command, including selection of leaders, direction of institutional structures, and the authority to pardon. In the twentieth century, the clause was interpreted to give the president every power a supreme leader is allowed in international law, but this had yet to be recognized in 1861.

Lincoln could look to several predecessors who had interpreted their military function broadly. George Washington did not hesitate to order an extraordinary armed operation during the 1794 Whiskey Rebellion. When federal prerogatives were challenged, he skillfully avoided real strife by displaying military might, yet limiting the action. Four decades later, Andrew Jackson’s stern threat of force silenced states’ righters when they attempted to nullify national law. James K. Polk, a strong and decisive wartime president, used the Army as a tool to implement his political goals. Devising an invasion of Mexico for the thinly veiled purpose of acquiring territory, he stretched the executive role by avoiding a congressional declaration of war, as well as by taking a hands-on approach to questions of strategy and command. The unwavering military stance of his successor, Zachary Taylor—which made no concessions at all to those threatening the federal authority—deflected the crisis of 1849–1850 by convincing the opposition that he would never back down. As a congressman, Lincoln protested what he saw as unauthorized use of the military by Democrats like Jackson and Polk.16

In the early days of 1861 Lincoln had little desire to follow these examples or to flex his military muscles. His ambitions for the presidency had been imagined differently: an opportunity to preside over party and patronage and to put a few domestic policies in place. Although he would greatly expand presidential war powers, Lincoln arrived in office without a blueprint for doing so. He executed an abrupt about-face, however, when he ordered significant belligerent measures within a few weeks, many of them of questionable legal status. (With Congress out of session, among other things he increased the size of the regular army, ordered a blockade of Southern ports, seized suspicious individuals without warrant, and funded it all with unauthorized sums from the Treasury.) Lincoln later maintained that extraordinary times demanded extraordinary measures, making the case with enough conviction that Congress then upheld him. Ironically, he also justified the actions by invoking the very presidents he had previously criticized. When the wisdom of resupplying Fort Sumter was questioned, he retorted, “[Y]ou would have me break my oath and surrender the Government without a blow. There is no Washington in that—no Jackson in that—no manhood nor honor in that.” The tension between presidential prerogative and shared constitutional authority over matters of war, coupled with the anomaly of a civilian leading professional soldiers, would challenge Lincoln for the next four years. 17

III

Lincoln entered the East Room flanked by Simon Cameron, his war secretary of one day. Cameron was a wiry, silver-haired man in his early sixties, with a thunderous, jutting brow. He was a famous wheeler-dealer from the Keystone State—Scott liked to say that Cameron “carried Pennsylvania in his breeches pocket”—with a reputation for being more shrewd than honest. Although the new secretary had served as a state militia officer in the 1820s, and was given the honorific title “general,” he seemed more like one of Lincoln’s pasteboard warriors than a real soldier. Cameron himself admitted he knew nothing about military matters and had been appointed because of his talent for backroom bargaining. Lincoln was warned from many corners not to undermine presidential credibility by such an appointment, and, indeed, he vacillated about putting the Pennsylvanian in the cabinet. “The country believes him not only unprincipled, but corrupt [and] intellectually incompetent for the proper discharge of the duties of a Cabinet officer,” Lincoln’s close associate George C. Fogg cautioned. “Besides, he has indulged in expressions of contempt for you personally, which should render his official connection . . . an impossibility.” But Lincoln was beholden to Cameron for support during the nomination process and thought he would have a quarrel on his hands if he did not give him an office. In the end, Lincoln bowed to partisanship, making a selection more political than principled.18

Simon Cameron, secretary of war, photograph by Mathew Brady, c. 1861

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Among those offended by Cameron were the regular officers, who had watched his shady dealings while he was an Indian agent in the 1830s. “It appeared to me a simple absurdity that a man of his noted reputation as a peculator, not merely a speculator, could really be advanced to a high position in the government,” wrote a brigadier general who refused to serve under the man. The appointment was especially irritating because there were clearly more compelling candidates for the post. One of the best, Judge Joseph Holt, had already impressed the nation by his performance as secretary of war in the final months of the Buchanan administration. As a Kentuckian, he had been under intense pressure from his family to join the Confederate cause yet had never faltered, either in questions of personal integrity or in his ability to deflect crisis. The New York Tribune asserted that Unionists were more indebted to Holt “for arresting the progress of treason than to all other men.” Similar accolades came from the seceding states, where Holt’s “firm, manly, patriotic, and wise administration of the War Department” convinced many that retaining him would do much to appease the exasperated South. Holt was probably in the East Room that March 12, for Lincoln had summoned him just prior to the reception. The contrast between his studious, deferential manner and that of the hawk-eyed Cameron could not have been sharper.19

As the naysayers predicted, Cameron’s appointment proved most unfortunate. The secretary of war snubbed the rest of the cabinet, often failing to attend meetings, and handed out key military contracts through his pals in Pennsylvania, circumventing normal procedures. Before the disastrous first battle at Bull Run in July 1861, the War Department seemed to move in slow motion, only backhandedly preparing for combat. The result was a terrible waste in lives and money that alienated both regular officers and volunteers. Although Cameron would later try to defend his actions, saying he faced unprecedented “dangers and difficulties” and oversaw a military structure simultaneously disintegrating and mushrooming, his ineptitude became ever more injurious. By October 1861 John Nicolay, Lincoln’s private secretary, would write: “Cameron utterly ignorant and regardless of the course of things; selfish and openly discourteous to the President, Obnoxious to the Country; Incapable either of organizing details or conceiving and advising general plans.” Still, Lincoln kept him on. The military preparedness of the nation limped along until Cameron crossed the President politically—by preempting him on the formation of an African American army regiment—and was exposed by Republican congressman Henry Dawes for plundering the Treasury. Only then was he eased out.20

The selection of Simon Cameron for what was arguably the most critical position in the administration raised questions among officers about just how well Lincoln understood the gravity of the nation’s situation. His appointment seemed insulting; an indication that politics, not military concerns, took priority at this pivotal juncture. In addition, Cameron not only irritated the South but proved so weak that Confederate leaders were encouraged to break openly with the administration. Indeed, in the early weeks of the crisis it almost seemed that Lincoln wanted to dismiss the importance of national defense. When he met with William Tecumseh Sherman a few days after his inauguration, the President was so dismissive of the need for trained soldiers that the offended Sherman swore he would not serve him. “If this be the Rule,” Sherman told his brother, a Republican senator from Ohio, “Mr. Lincoln must expect all National men to slide out of his service, and the want of appreciation of fidelity . . . will lead to the betrayal of his army & navy.” Lincoln’s apparent disdain for the regular forces was already being whispered through the ranks, demoralizing men just when their services were taking on increasing importance.21

Entering the East Room alongside Lincoln and Cameron was the officer who had formed this army, and now stood ready to introduce it to the President. Lieutenant General Winfield Scott was seventy-four years old, born on a farm outside Petersburg, Virginia, just before the Constitution was written. A colossus of a man, Scott had an imposing physique that dwarfed the sinewy Lincoln. He was thought by some to favor Southern ways and Southern men, but most of the public saw only his decades of commitment to the nascent United States. Scott had been a young lion in the poorly managed War of 1812; then went on to lead a stunning set of victories during the Mexican conflict, taking risks and executing maneuvers that profoundly influenced protégés such as Robert E. Lee. His masterpiece, however, was the formation of a highly trained, strictly disciplined, and modernly administered military force.22

General Winfield Scott, photograph by Mathew Brady, c. 1861

NATIONAL ARCHIVES

In the early 1820s, Scott joined with Secretary of War John C. Calhoun and West Point Superintendent Sylvanus Thayer to persuade skeptical Americans that a permanent corps of professionally trained troops would pose no threat to their society. Instead of representing armed oppression, they argued, these men would guard the peace and provide a model of leadership for the entire nation. To codify his beliefs, Scott wrote a manual called General Regulations for the Army; or, Military Institutes, which contained rules for everything from the proper salute to standardized procurement forms. It ensured that military leaders would take no liberties with their authority, but literally do everything “by the book.” In addition, a West Point education stressed national service, encouraging soldiers to identify with the whole country, rather than promote sectional interests. Despite setbacks, the creation of this skilled cadre had been a brilliant success. By the 1850s the United States Army was recognized internationally for its accomplishments, and its leader was considered one of the world’s finest field commanders. As he aged, however, the brilliant Scott had taken on the characteristics of a puffed-up martinet, becoming pompous, inflexible, and gouty. Those who observed him in the winter of 1861 differed on whether he alone had wit enough to stem the crisis, or simply blocked the way of those who did.23

Scott had never before met the new chief executive, though they shared an old Whig Party background. In the 1860 race, Scott favored John Bell, the Constitutional Union Party candidate, but saw little to fear in the Republican victory. He tried to calm those who believed Lincoln meant to challenge existing laws or bully the South. Despite his Virginia background, Scott was dedicated to the federal government and opposed to the principle of secession. Indeed, he thought the menacing rhetoric of Charleston hotheads was ridiculous. “I know your little South Carolina,” he scornfully told the wife of one of that state’s senators. “I lived there once. It is about as big as Long Island, and two-thirds of the population are negroes. Are you mad?” Even before the November poll, the general wrote a lengthy essay on the national crisis, sending it to Buchanan, as well as political allies among Virginia Unionists. When a Republican confidant called on the old warhorse, he recorded that Scott believed Lincoln to be an honest politician and questioned only whether he was “a firm man.”24

Scott had a habit of overstepping his military authority to offer sweeping political analyses and unsolicited advice to his presidents. Though well intended, their format was often rambling and the tone presumptuous. He had gotten into trouble with past leaders such as Polk for blurring the lines between martial expertise and political meddling. The “Views” he expressed in October 1860 followed this pattern. In them, he advised a public expression of conciliation to the secessionists, backed by a clear commitment to the use of force—specifically, the reinforcement of all military facilities in the Southern states. By these means Scott hoped that “all dangers and difficulties will pass away without leaving a scar or a painful recollection behind.” But his “Views” were roundly ignored, both before and after the election. In late December he again urged the secretary of war to strengthen fortifications while there was still time, complaining that inaction not only endangered the Union but was causing him to sleep poorly. He worried too about Lincoln’s reticence during this period, feeling that both the outgoing and incoming administrations were playing into Southern hands by allowing them to preach, plan, and prepare war. The president-elect’s “silence,” Scott warned, “may be fatal.”25

IV

At the White House, Scott began to introduce the blue-coated men, who were moving toward the President in rank order. Emotions in the room were volatile, yet the officers’ faces were trained to impassivity, and Lincoln had no idea what thoughts were forming under those patent-leather visors. Neither could the military men fathom his feelings. The issues were too complex to discuss on such an occasion and few speeches were made. Not knowing how to salute as per Scott’s regulations, the President pumped hands; but the unease was too palpable to dispel with a cordial greeting. The room, recalled several, was strangely quiet.26

As Scott called out the names, Lincoln may have noticed something striking about this group. Newspapers had commented on the inflated number of officers on duty in Washington during the inauguration, but the line moving slowly toward the chief executive was strangely short. In fact, the small cadre was sadly indicative of the country’s modest defenses. George Washington’s sage advice—that “to be prepared for war is one of the most effectual means of preserving peace”—had seldom been taken to heart. Over the years, the same mistrust of a standing army that Lincoln expressed had led congressmen to reduce the size of the officer corps, cutting military budgets arbitrarily, and sometimes indulging in open ridicule. As a result there were only 1,100 officers and some 15,000 men in the regular army in early 1861. This slim force had to guard a continental nation of thirty million inhabitants, one that was more or less at perpetual war with Native Americans, border ruffians, and foreign adventurers. James Buchanan maintained that his failure to hold the southernmost forts was due to the inadequacy of forces—that at best he could spare only 500 men to respond to urgent situations. Even though the fifteenth president’s statesmanship was open to question, his understanding of the scanty resources available to him was not.

In theory this skeletal force was to be fleshed out by a three-million-strong militia, but this was something of a chimera. Fragmented geographically and controlled by local officials, the state militias were generally disorganized and undisciplined, scarcely fit for emergencies. At best, most were outfitted for duty at ceremonial “muster days,” like the one Lincoln had mocked, or drilled to adorn funeral parades. The striking ineptitude of the militia in the War of 1812, or in debacle-prone contests like the Black Hawk War, had not dispelled popular fantasies about the nobility of “citizen-soldiers,” however. Nor had the splendid performance of the regular army in Mexico inspired robust congressional support. The army budget already stood at its lowest point in years, when, on the very precipice of crisis in December 1860, the Senate called for an inquiry into how it could be further reduced. Atop this shaky foundation, Scott’s achievement in maintaining professionalism and morale was little short of remarkable.27

The aged appearance of many officers added to dismay about the undersized force. The entire army was led by only five generals, whose average age was over seventy. Two of these—Scott and Quartermaster General Joseph E. Johnston—faced the President that day, as did a half dozen colonels, who nearly outpaced the generals in years. Most of them manned administrative departments—and some had been at the same desk for decades. The number of promotions was strictly regulated by Congress, so that no one could move up unless a position was vacated. Since there were no annuities, no one retired. The result was an organization clogged at the top with men past their prime, shored up by frustrated subordinates. “The vegetables,” one wag termed them. “Few die and none retire” was another popular witticism. An assistant adjutant general made a “conjectural calculation” that in the prevailing circumstances it would take an incoming lieutenant fifty-eight years to reach the level of colonel. All of this fostered a smoldering resentment among enterprising officers, who chafed at their enforced obeisance to the hierarchical reliquary and yearned for greater opportunities.

That March 12, Lincoln was introduced to Colonel George Gibson, the Commissary Department’s nominal head, who had held that post since 1818 and was now completely unequal to its duties. Farther down the line stood his assistant, an infirm lieutenant colonel named Joseph P. Taylor, who was just as advanced in years and just as incapable of responding to the exigencies of war. Surgeon General Thomas Lawson, who had been in the Army since 1809 and kept a dictatorial hold on his post for twenty-five years, also doddered past Lincoln. His duties were performed by a subordinate for a few more weeks—then Lawson figuratively dropped in the saddle. Henry K. Craig, whose white hair and strikingly red face provoked ridicule, had served in the Ordnance Bureau for thirty years and controlled its affairs for a decade. Despite shocking reports of arms transfers from the bureau to the South in early 1861, Craig was clinging to his post, citing “seniority” as justification. His case was typical: virtually all of these worn-out men genuinely believed that decades of staff service equated with professionalism, and, if open to bureaucratic changes in theory, they resisted them in practice. The War Department had been functioning for years on the strength of red tape, neatly tied up by lower-ranking aides, whose loyalty—and ambition—kept the bureaus running. More than one person observed that no one at the War Department, with the possible exception of Scott, seemed fitted for the responsibilities of the moment, let alone those of the age.28

Lincoln was inheriting a miniature army, wizened at the top and stifled throughout the ranks. Yet these were not toy soldiers. Among them were some of the finest field officers in the world, as well as pioneers of military arts. West Point was not only the earliest but the best center of scientific education in the United States. Its graduates had presided over the techno-revolutionary marvels of the last four decades, developing superior weaponry, redirecting water routes, and engineering roadways that linked the vast expanses of the continent. Many defined themselves as scientists rather than soldiers. Chief Engineer Joseph Totten, an accomplished chemist near the head of the receiving line, had invented a novel type of cement to fortify coastal installations against the pounding tides. William Buell Franklin, a captain, also about to meet the President, was at the moment supervising construction of a new Capitol dome, an engineering marvel with great symbolic significance for the fractured nation. A few paces ahead of him stood Captain Montgomery Meigs. A gifted engineer, Meigs already coupled his notable eccentricity (he ate milk toast with cucumbers and French dressing for breakfast) with technical genius and artistic sensibility. He had conceived and constructed the Washington Aqueduct, a beautiful structure that encompassed the world’s grandest stone arch. His magnificent Pension Office Building, with its carved frieze of Union soldiers marching toward infinity, was still in the future, but Meigs’s talents already stood out in high relief.29

In addition, many officers had won laurels in the Mexican War and viewed the looming threat of combat with far greater understanding than their fellow citizens. Despite its political sins, that war had been a tour de force for the regular army and the Navy. They had fought the larger Mexican Army on its own territory, outmaneuvering the enemy on punishing terrain by what General Scott liked to call “head-work.” Many of the men standing before Lincoln had received two or three “brevet” promotions for their valor—which in the absence of genuine advancement gave them rank and recognition. Under Scott’s direction, American forces then occupied Mexico with a generosity to the conquered nation that was unheard of at the time, inventing the concept of a just peace. Scott himself had faced down the world’s skeptics. Even the Duke of Wellington, who had raised his eyebrows at Scott’s bold drive toward Mexico City, finally admitted: “His campaign is unsurpassed in military annals. He is the greatest living soldier.”30

The officers of the United States Army had no reason to apologize as they stood before their new president. They were better educated than he was, and more poised and polished to boot. Posted all over the continent, they knew intimately the challenges of the wild and sprawling country. They were also politically sophisticated, having suffered the consequences of self-serving officials who sacrificed national interests for party or privilege; and they had witnessed a great deal more of war’s violent reality than Abraham Lincoln could imagine.

They were, moreover, entirely aware of these advantages.

One would like to think the commander in chief had been briefed about the condition of his army before he was introduced, but this kind of staff work was never a strength of the Lincoln White House, and especially not in these early days. Nonetheless, he probably knew enough to realize that, despite its gloss, the military fabric was unraveling. For one thing, the Army was out of funds. In 1860 Congress had seen fit to appropriate no greater monies than it received in 1808, though America’s population had quadrupled, and its territory nearly doubled. The situation was particularly acute because Buchanan’s headstrong, incompetent war secretary, John B. Floyd (Holt had served for only the final months of the administration), had taken no action to ready his department for conflict. Outgoing Treasury chief Howell Cobb had meanwhile done his best to exhaust the coffers before departing, and the armed forces had not been funded in months. From Washington Territory to Santa Fe, supplies, provisions, and pay were in short supply—or nonexistent. “We are all out here in a state of great anxiety as to our future, the Paymasters have no money, the QMaster [quartermaster] has none, & the Commissary but little,” complained a still loyal, but anxious, soldier named Cadmus Wilcox from his western post. A visitor to Fort Washington, guarding the Potomac River approach to the capital, was stunned to see how shabbily it was maintained and how thinly manned. When Scott was broached on the fort’s condition, he retorted that a few weeks earlier it “might have been taken by a bottle of whiskey. The whole garrison consisted of an old Irish pensioner.” In the Navy the state of affairs was equally lamentable. Arriving at his new post in early March, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles found near disarray: “No one can realize the confusion and utterly deplorable condition of things that then existed in naval administration,” he recalled. Over at the War Department, Cameron discovered that they were virtually devoid of munitions, and that Massachusetts senator Henry Wilson (who would later take a spirited pro-army stance as head of the Military Affairs Committee) was proposing to save money by allocating outmoded smoothbore weapons to the forces. “These arms were good enough to fight the Mexican War with,” Wilson calmly asserted.31

As it happened, ordnance was a particularly sensitive point with the Army at that moment. Congress had underfunded munitions for decades, and though there were shops and machines enough to produce 40,000 stands of arms a year, appropriations were too small to turn out more than 18,000. Even this scant supply became the subject of a scandal when outgoing war secretary Floyd was accused of allowing large numbers of arms to be sold to firms that later transferred them to arsenals in the South. Actually, Floyd—a reluctant secessionist—had not directly sold federal weapons to state agents. He had, however, instituted practices that made old armaments available to militias, and new production methods open to copy by nongovernmental manufacturers. Nonetheless, an incensed Northern public believed the worst, and the credibility of the Army as a whole suffered. Several fine officers, notably General John E. Wool and Major Alfred Mordecai, were stunned to find their reputations under fire when they carried out Floyd’s orders to furnish the weapons. Mordecai, one of the most respected men in the service, was particularly suspect since he had close family ties in North Carolina and Virginia. The “chafe of public affairs” he experienced during the arsenal questioning influenced Mordecai’s decision to resign from the Army, though he later declined to fight for either side.32

V

The munitions scandal fueled worries that Southerners in the Army were tacitly keeping their old commissions, while actively working on behalf of the seceding states. And, indeed, some were playing this double game. Captain Bernard Bee, a South Carolinian, sent a remarkable letter to Virginian Henry Heth, describing his clandestine activities among the companies at Fort Laramie in Nebraska Territory. He was encouraging sympathetic officers to keep their units intact, Bee confided, then to march them southward, bringing “all they can with them.” He requested that Heth call on Jefferson Davis to affirm that if a state seceded, its native sons would be absolved of any previously sworn loyalty oaths. Such an assurance, noted Bee, would “aid me in bringing men and material South.” In a like spirit, Quartermaster General Joseph E. Johnston was using his office to explore transportation projects that would benefit the expanding Southern territories. He proposed his ideas to none other than George B. McClellan, a former army officer and railroad executive with pro-slavery sympathies, with whom he had dreamed similar dreams in the 1850s. Others, like former United States marshal Ben McCulloch, were actively conspiring with the secessionists, both politically and militarily. Two weeks before Lincoln’s inauguration, McCulloch played a key role in forcing another Southern officer, General David E. Twiggs, to surrender federal troops and property under his command in Texas.33

The Twiggs incident—and the mistrust it had fostered—was uppermost on everyone’s mind that afternoon at the Executive Mansion. A native of Georgia, Twiggs had given distinguished service in every American conflict since 1812 and had been honored by Congress for his role in the Mexican War. One of the septuagenarians who populated the higher ranks of the service, he had been ill for a year when, on December 13, 1860, he took over the Department of Texas from Lieutenant Colonel Robert E. Lee, who was acting in his absence. Sensing the drift toward disunion, Twiggs wrote the same day to Scott for instructions. Scott replied that at this critical moment all decisions were political, and that he too was unable to get a clear idea of President Buchanan’s intent.

Twiggs wrote four more times to Washington, candidly stating that a crisis was brewing, and that he did not want personally to be responsible for starting a fratricidal war. He pointed out the difficulties of defending a department that included 10 percent of the Army’s assets, but was spread over a thousand miles of rough territory. He told Washington that Sam Houston, Texas’s Unionist governor, had warned him of the secessionists’ plan to commandeer federal property. Houston was trying to work out a sub-rosa arrangement to keep the Army in Texas, but Twiggs admitted to the governor that he had no instructions on how to respond to such a request. He then dutifully relayed the entire correspondence to headquarters.

Completely cut off, and convinced that “coercion” would not help the situation, Twiggs asked to be relieved of command before Lincoln’s inauguration. The request was granted, but communication delays meant the order did not reach him until after the Texas convention had voted for disunion. At that point, Twiggs was forced to conduct negotiations with a junta of secessionist politicians and Ben McCulloch’s unruly band of Texas Rangers—without support from Washington. Unnerved, the general waffled rather than readying his men for a counterchallenge; and in the end he capitulated. Twiggs did try to arrange the most “honorable” deal he could without resorting to an armed confrontation: ordnance and arsenals, including the symbolic Alamo, were turned over to the rebels, but he secured safe passage out of the state for his troops. (That there was considerable pressure to take captives is clear from McCulloch’s records, for he angrily wrote that to let the soldiers go was “an insult to the commissioners and the people of the State.”) Nevertheless, Twiggs’s surrender shocked the North, deepening the shadow of suspicion over the Army.34

In one of his last acts as president, Buchanan cashiered Twiggs, without court-martial. It was an unprecedented move, and officers debated whether they had been more betrayed by Twiggs or the authorities in Washington. William T. H. Brooks, who would become a Union general, told his father during the withdrawal from Texas that Twiggs had been treated high-handedly. “We got the news about Gen Twiggs being struck from [the] rolls of the Army by todays mail—It is an exhibition of very petty spite to call him a coward,” Brooks protested, adding that few people understood the difficulty of their situation. Nonetheless, he acknowledged, military men were in “a most humblifying situation, placed so by his act—We don’t go out exactly as prisoners of war but it is the next thing to it.” Edward Hartz, another West Point man serving under Twiggs, was incensed by the general’s actions but thought the furor over the Lone Star State was ridiculous. He considered Texas worthless, Hartz declared: “[She] has never brought anything into the Union but . . . her quarrels and her debts.” Twiggs, thinking he had taken all proper measures, was stunned by Buchanan’s dismissal, and for the rest of his life wrote threatening letters in a shaky hand to the ex-president. “This was personal, and I shall treat it as such, not through the papers but in person,” he warned Buchanan. “So prepare yourself. I am well assured that public opinion will sanction any course I may take with you.” A few weeks later, he joined the Confederate forces.35

Those standing before Lincoln in the East Room were still reeling from the incident. Most felt little charity toward Twiggs. Major Samuel Heintzelman asserted that no officer should ever relinquish arms under his control, and that Twiggs’s actions were treasonous. Lieutenant Colonel Lee, just arrived from San Antonio, took pains to assure colleagues that, had he continued in command, the secessionists would not have gotten “the arms from [his] troops without fighting for them.” It seemed the whole officer corps was mourning the loss of its integrity. Crusty old General John Wool spoke for many, mincing no words. “Twiggs has proved himself worse than an hundred Benedict Arnolds,” he thundered. “It was rumoured last evening that he had been shot. The news is too good to be believed. A greater villain never existed.”36

The Twiggs affair stunned the regular officers, but his was not the only early defection from their ranks. Adjutant General Samuel Cooper’s sudden departure, a few days before the Army’s introduction to the new president, had rubbed salt into the wound left by Twiggs. Cooper was married to a Virginian—indeed, the sister of pro-slavery senator James Murray Mason—and these ties had overridden his own New York heritage. He could no longer “dissemble” on a daily basis, Cooper told the one comrade who dared write him for an explanation; and he had decided he would “at least, have the consolation to feel that I shall go down to my . . . resting place without self reproach.” Others were leaving in an equally painful manner. Future Confederate general Ambrose P. Hill, then a lieutenant assigned to a coastal survey team, pointedly requested that his resignation be accepted before the sixteenth president’s inauguration. His demand was honored. There was also a gap in the blue-coated line where Mississippian John Withers, a much admired assistant adjutant general, usually stood. His resignation was accepted on March 1, and his duties turned over to a co-worker, Captain Julius P. Garesché, who now moved forward to meet Abraham Lincoln.37

Garesché was a dark, serious man whose amiability masked a fiery temperament that some linked to his Cuban heritage. He was greatly distressed by the resignations of Cooper and Withers, both of whom he liked. The departure of his boss was all the more disturbing because Garesché’s two brothers were Southern sympathizers, then under suspicion in St. Louis. Captain Garesché shared his siblings’ fear of slave insurrection, which his family had experienced in the Caribbean, but he was intensely loyal to the Union. With his superiors gone, Garesché was now assigned to keep the Army’s official register. There was a pot of bloodred ink on his table, and a straightedge ruler beside it. As withdrawals arrived in the adjutant general’s office, Garesché drew thick scarlet lines across each departing soldier’s name, fully aware that if they were deserters in his eyes, they were heroes to others. By May 1861 the toll of resignations would encompass more than a third of the regular officers, and the pages of the roster grew into a crimson-blotched omen of the carnage to come. Garesché’s grisly end seems also to have been foretold in the stained pages. He had embraced a charismatic brand of Catholicism, which induced a premonition of sudden, violent death in battle. Just as he prophesied, Garesché fell “in a cloud of blood” in his first field assignment, when a cannonball blew off his head during the December 1862 action at Stones River, Tennessee.38

As Garesché’s roster became ever more blotted, many were outraged that these resignations were being countenanced at all. The military academies had taught that officers should give equal allegiance to all elected authorities, regardless of their political leanings. This was what distinguished democratic armed forces from those led by tyrants, who demanded personal fealty. Every military man had sworn an oath to defend the United States against “all opposers, whatsoever,” and desertion of the old flag mocked this premise. To some it appeared that by accepting the resignations, rather than treating them as treasonous, the administration was deliberately furnishing the South with a well-organized force, tailor-made to protect its interests. Naval captain Samuel F. Du Pont “spoke out plainly” against those who he believed served two masters and chafed at the demoralization the departures caused. “The Department should not have accepted a single resignation,” he wrote passionately, “if a brother of mine could have been of the number, I should never wish to see his face again.” In fact, Navy Secretary Welles ultimately decided it was impolitic to ignore the flight to rebellion. After the action at Fort Sumter, naval officers were stricken from the rolls if they resigned and then took up arms for the South. Many considered this dismissal the most painful event of their lives, and some spent a lifetime trying to reestablish their honorable status.39

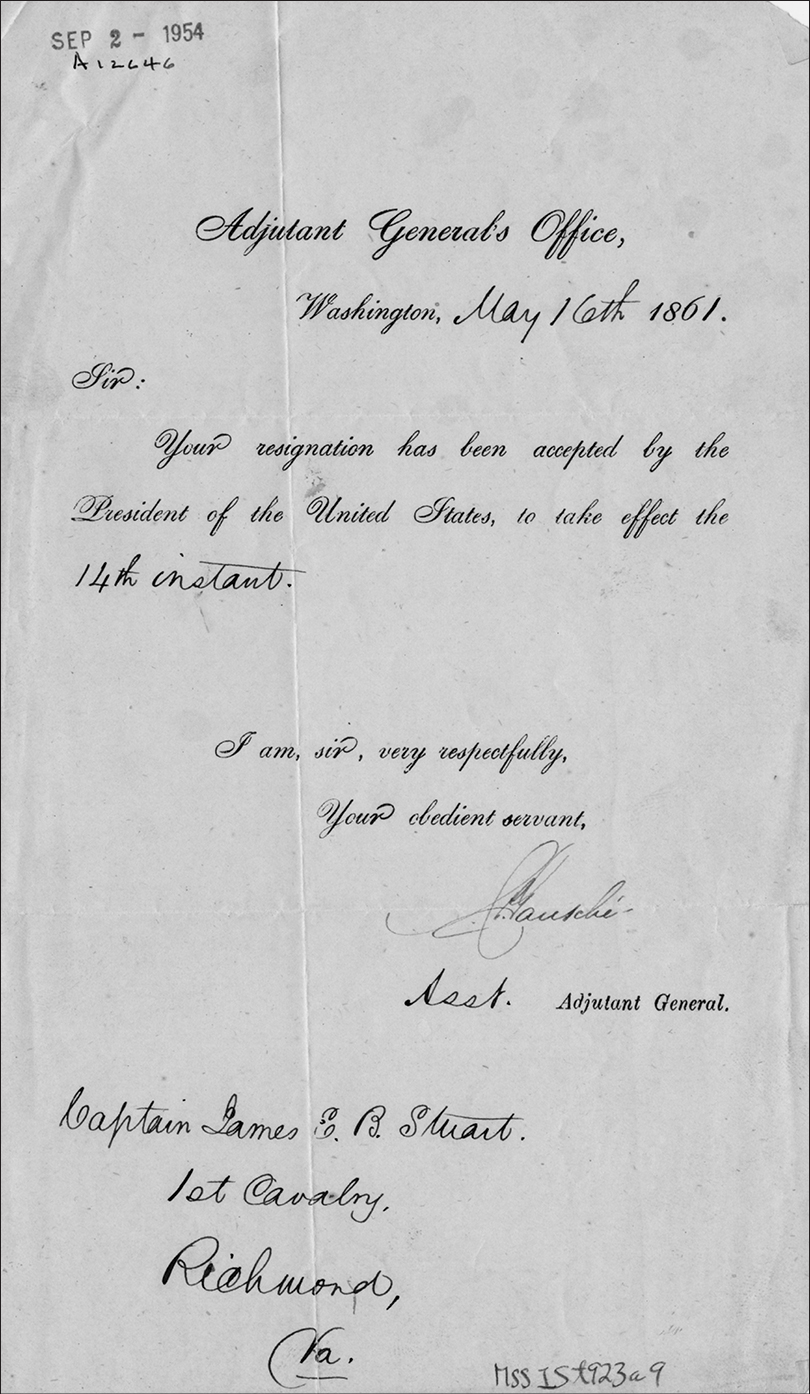

But at the War Department Cameron took a different tactic, obligingly consenting to all resignations. In a few weeks the pace of defections was so brisk that the department actually began sending out form letters, approving, without question, the relinquishment of commissions. Remarkably, those letters were signed “respectfully, Your obedient servant” by the secretary. Much of the public looked askance at this, calling for loyalty oaths to be administered to the remaining officers or demanding that those who resigned be apprehended and tried. Navy lieutenant David Dixon Porter was one of many who thought that anyone resigning just as the nation faced a critical test should be imprisoned. As commander in chief, Lincoln could have halted the easy approval of resignations, of course, by establishing a uniform policy among all the armed forces or by placing disloyal officers under military arrest for the safety of the country. He could also have proposed that defections of this kind constituted treason. But in early 1861 Lincoln’s mind was bent on calming emotions, not heightening them, and he took no action. As a result, the United States Army and Navy evaporated before him.40

The Army form letter of resignation for J. E. B. Stuart, May 16, 1861

VIRGINIA HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Officers who remained in service found their long habits of cooperation severely tested as they faced the “new, supreme, untried, cursed grief” of guessing who might next abandon Old Glory. Welles and Cameron both noted when taking up their duties that the air was poisonous with doubt and distrust. Military men found their easy familiarity so strained that they “gradually receded from that frank communion which is apt to exist between officers of the same service” or sometimes exploded into open quarrels. Assistant Adjutant General Dabney Maury, anxiously waiting news at a frontier post, remarked that even socializing was highly orchestrated so that men on opposite sides of the debate would not have to meet. Margaret McLean, who on March 12 floated into the East Room with Mary Lincoln to view the resplendent gathering, must have been reminded of a reception a few weeks earlier where she had watched officers play guessing games about who would stay with the old army and who would go. McLean was the daughter of an erect, somber man near the head of the reviewing line, Colonel Edwin Sumner, who would serve the Union, though without particular distinction. She was also the wife of a Virginia secessionist, Captain Eugene McLean, who stood at attention farther down the ranks.41

Collegiality was swiftly eroding, and the uniformed men mourned its loss. “The breaking up of the associations of a life time . . . ; the abandonment of high positions . . . ; the crushing out of hopes, aspirations, plans, friendships & all the prospects of life that we have so carefully originated, cherished and digested; all these come to us with a force that none other of our Countrymen feels or can feel,” mused a devastated officer named Henry Wayne, who had been decorated for gallantry during the Mexican War but felt he must side with his fellow Georgians. Beyond dashed ambitions and broken relationships there were more serious consequences. In the rough-and-tumble of field life, where isolation was common, and pay, promotion, and reinforcement uncertain, shared hardships had forged ties that allowed the military to function with cohesion and resolve. “All its venerated customs of service and its immutable regulations, its mathematical tactics and rigid discipline, its cherished history and sacred legends, its unyielding esprit . . . [were] to be swallowed up and diffused,” lamented a Northern officer. As traditions began to crumble, so did the confidence and mettle of the forces.42

Some of the men in the East Room were attempting to shore up their institution by rekindling the old camaraderie. Captain William Farrar (“Baldy”) Smith was one who spent a good deal of the secession winter trying to persuade Southern-leaning colleagues to remain loyal to the United States. But many officers lashed out at the political wrangling they believed responsible for the nation’s predicament. Lieutenant Custis Lee, the youngest of the three Lee family members greeting Lincoln that day, had sorrowfully broached this with his Ohio comrade James B. McPherson just as the crisis began. “You know Mac that I am not much of a politician; and have a great disinclination for the dirty business . . . but have been obliged to read and see a great deal in reference to it recently; and must say that I hardly know what to think of the signs of the political times.” In the election Lee, like Winfield Scott, had supported John Bell, but he thought fears of the new Republican administration were overblown. Yet he was pessimistic about the ability of politicians to manage the emergency. “I have heretofore thought them harmless; but they have finally succeeded in bringing the country to the verge of dissolution, if not to the fact,” he glumly remarked. As if in echo, General Wool poured out his rage to Republican Party boss Thurlow Weed: “Treason, imbecility, and intrigue rule the hour!”43

Custis Lee and Wool, like most of their compatriots, had kept aloof from political shenanigans. Many army men, including Scott, actually refused to vote because they felt the role of the military was to act with equal loyalty under all governments. There were those who tried to pull political strings, of course, hoping for place or promotion, or liked to hobnob with elected officials and talk the talk of national strategy. But among the West Pointers it had been a point of pride to shun parochialism or undue partisanship. Julius Garesché, for example, leaned toward the Democrats, but never acted on his beliefs since “it was not considered a proper thing for an Officer to take a prominent position in party discussion or to pronounce any decided opinion on the subject.” Now, to their dismay, some were directly blaming the Republicans for a platform that had inflamed the country. In Texas, Edward Hartz pointed at Lincoln as author of “the unholiest of unholy wars ever instituted,” all for the sake of “so many miserable negroes.” The men were tired of listening to the President’s “wing flaps & crowings,” complained an officer at Jefferson Barracks in the border state of Missouri: they wanted Lincoln to act. At Fort Sumter, the garrison was appalled to find itself being held responsible for a predicament caused by partisan bellowing and administrative bungling. As the situation worsened, tempers and rhetoric were dangerously inflamed. “The truth is we are the government at present,” Assistant Surgeon Samuel Crawford wrote hotly to his brother from Charleston harbor. “It rests upon the points of our swords.”44

If the officers mistrusted their untried commander in chief, Lincoln was equally chary of the men in uniform. He was all too aware of the irregularities at various arsenals, the disaffection of senior officers, and incidents such as the one at Pensacola, Florida, where two naval men surrendered the United States Navy Yard to the rebels, then calmly resumed their duties, this time for the Confederacy. Before he arrived in Washington, Lincoln had begun to inquire about the loyalty of military men surrounding him. He was concerned about Fort Sumter’s commander, Kentuckian Robert Anderson, and made a point of soliciting Joseph Holt’s opinion on the subject. Even venerable General Wool thought he might be distrusted by the president-elect, and took the unusual step of officially proclaiming his unswerving devotion to the United States.45

Lincoln was particularly nervous about Winfield Scott and had him checked out more than once before they met. When Scott ran for president in 1852, Lincoln had both campaigned and voted for him, and now, in the midst of turmoil, he badly wanted to rely on the seasoned lieutenant general. In reality, Scott was so firm in his national allegiance that he lashed out at overtures from Confederate officials, as well as at critics who believed his taste for Virginia ham smacked of disloyalty. When Kentucky senator John J. Crittenden wired to ask the general’s intentions, he sent back a curt reply: “I have not changed. I have had no thought of changing. I am for the Union. Winfield Scott.” But in the days following the inauguration, Scott had also sent a series of disturbingly contradictory messages to the Executive Mansion on the critical issue of Fort Sumter, bouncing between opinions in a way that seemed erratic, if not duplicitous. It tarnished Lincoln’s bright hopes for a collaborative administration, feeding instead the President’s inclination toward secrecy and maneuver.46

Scott initially thought he and his men could ward off catastrophe if only the civil authorities would allow him. “Gen Scott told Brother John [naval officer John Rodgers] today that he ‘believed he could save the country if they would let him,’” an officer’s wife named “Nannie” Rodgers Macomb confided to Montgomery Meigs in early 1861. Scott had seen this situation before, during the nullification crisis of 1832, when Andrew Jackson quietly dispatched him to South Carolina with orders to strengthen military facilities while avoiding overtly provocative actions. Scott was not opposed to using force: he told another naval man that “there were worse things than bloodshed & he didn’t mind shedding a little if it would preserve the Union, it was a good country & worth preserving.” But his 1832 experience proved a false model during the secession winter. Emotions had grown rawer in the ensuing decades, and prospects in the slave states brighter. Moreover, although Scott had strongly recommended in late 1860 that federal forts in the South be strengthened, he now believed the rebels had been allowed so much leeway that Charleston and other key spots were well fortified. The time for showboating was over.47

Nine days before the reception Scott penned these thoughts to incoming secretary of state William Seward. Indicating that the moment for a swift rebuke to the secessionists had passed, he mapped out four options for the crisis-gripped administration: conciliation with the rebels; calculated inaction; military aggression; or peaceful acceptance of disunion. Fort Sumter had no military importance, he argued, and it could be abandoned without sacrificing the larger political point. When Lincoln directed him on March 5 to reinforce all United States military establishments, the general dragged his feet, and the instruction had to be underscored with a written command. Then, the day before the meeting in the East Room, with the secretary of war’s concurrence, Scott actually ordered Major Anderson to withdraw from Sumter—an order that had to be rescinded by Lincoln. He caused further doubts by handing the President a paper the next day—possibly at the reception—advising that to hold Sumter would be continuously to reinforce it, making confrontation inevitable.48

Scott’s messages jolted the cabinet and angered Lincoln, but in fact the government was also at odds with itself. When he entered the East Room on March 12, the President had come directly from a meeting with an old Washington guru, Francis P. Blair, who bluntly told him that “the surrender of Fort Sumter was virtually a surrender of the Union.” Some cabinet members had gone further, devising a secret plan to resupply the garrison with coastal survey vessels—an arrangement that was ultimately deemed impractical, and of which Lincoln may have been unaware. At the same time, Seward, in agreement with Scott, was hatching schemes to placate the secessionists. The President was receiving conflicting advice from all over the country, some urging him to abandon the polarizing stronghold, while others stated it was imperative he stand his ground. Meanwhile, Unionist leaders in border states were begging for a clear policy that would strengthen their hands, and Northerners were beginning to panic. “Is Democracy a Failure?” the usually sympathetic New York Times asked in a biting editorial that month. The Union could only survive, it maintained, through a radical reform of its structure and purpose. “Are we great enough for it—are we capable of it?” asked the Times editors. “One thing is, at least, certain, face it we must.”49

VI

Lincoln struggled over Sumter’s defense, but most of the officers in the East Room agreed with Scott. Several had been involved in the developing events, and all were sobered by the prospect of waging war over an insignificant, half-built fortification that lacked the capacity to defend anything, including itself. (One ordnance expert concluded that guns placed at the fort could not reach a single target in Charleston and that any firing would be “exceedingly wild at such an elevation and non-effective.”) Captain Fitz-John Porter, who was sent to assess the situation the previous autumn, had recommended the garrison’s command be turned over to Anderson, whose Southern credentials might placate the local population. The change of command had already taken place when Major Don Carlos Buell, a colleague of Porter who was now standing about midway up the blue line facing Lincoln, arrived to consult with Anderson about the situation in December 1860. Buell had strict orders to avoid confrontation. He interpreted these liberally, by helping orchestrate a clandestine movement of the vulnerable federal force from Fort Moultrie to the more secure Sumter. That action, engineered in the dark of Christmas night, only enraged South Carolinians. When Governor Francis Pickens took immediate measures to fortify the harbor, war began to look unavoidable.50

Short of stature, but long on martial savvy, Buell was thought by some to have a greater grasp of the deteriorating situation than any man in the Army. By the time Lincoln met the elegant major on March 12, he almost certainly knew of Buell’s actions in Charleston and may also have heard that Buell had Southern family connections. Perhaps this is why the President failed to consult him, for it is striking that as Lincoln formulated his strategy, he conferred with neither Porter nor Buell, the two men in Washington with the greatest firsthand understanding of Anderson’s predicament. Instead he sent a new team to Charleston, which included a midrank navy man, but no army officer, and the burly Ward Hill Lamon, a former law partner whom Lincoln came to use as a kind of White House bouncer. Lamon confused the situation by stepping completely outside his brief to converse unofficially with Pickens and to inform both the governor and Major Anderson—erroneously—that the fort would soon be evacuated. Sumter’s force viewed this expedition, led by a man who “had never been in a small boat nor in a Fort before,” with scorn; and Pickens angrily concluded he had been willfully misled. It was an ominous preview of Lincoln’s pattern of shunning professional military expertise to rely on amateurs with whom he had personal ties. Uncertain as he was, these were the only men the President felt he could count on.51

Part of Lincoln’s problem was that he had listened to gossip from the military men around him. All of it was unsolicited and much of it self-serving, but in his ignorance of personalities and procedures he had rather gullibly swallowed these accounts. Even before the election, some officers had sent Lincoln lengthy descriptions of supposed betrayal in the Army. These astonishing letters went well beyond the boundaries of the military’s crisp code of conduct. Lincoln’s files held furtive notes from lieutenants, captains, and disgruntled majors, and even one toadying message from the venerable Colonel Sumner. Scott was also guilty of stretching his prerogative in this fashion, but he was the leading general in a crisis-stricken nation, with some justification for directly addressing his future commander. A few of the men aired their long-held grievances; many were fawning or openly currying favor. All were far outside established military regulations, which prohibited unauthorized communication with government officials and required formal messages to go through hierarchical channels.

Major David Hunter, in a letter marked “Private and Confidential,” took it upon himself to warn Lincoln in October 1860 of Southern officers’ “most certainly demented” views on slavery. Posted to isolated Fort Leavenworth in Kansas, he was well out of the informational loop, yet he ominously predicted that the Army and Navy might cooperate in a coup d’état when the new president entered office. For good measure he recommended himself for a generalship. In an extraordinary seven-page letter, Captain John Pope slammed those who had “embarrassed” the government in its hour of need and were now rewarded for their “treachery” by secessionist authorities. He also took the opportunity to assure Lincoln of his personal fidelity, as well as to remind the president-elect that he was a son of Illinois. Captain George W. Hazzard went further, naming names of those he thought disloyal, including his superior officer—a breach of etiquette that would have been grounds for a court-martial had the letter been intercepted. Lieutenant Colonel Erasmus Keyes, an aide in Scott’s office, laid bare his long-festering grudge against Southern colleagues and boldly suggested a few candidates for secretary of war.52

Had Lincoln better understood the importance of discretion and hierarchy for a functional army, he would have forwarded these effusions to the War Department with an order that the practice be halted. Instead, he not only absorbed the extracurricular tales but embraced the storytellers. Sumner, Hunter, Hazzard, and Pope were all invited to accompany him when he traveled from Springfield to the inauguration, and Keyes became an early favorite, charged with confidential missions pertaining to Fort Sumter. Ostensibly the officers were invited in order to protect the president-elect, but they appear to have been rarely called upon for this duty. Instead, they took full advantage of their proximity to Republican nabobs to express ex officio opinions and lobby for position. These were probably the first “military briefings” Lincoln experienced and their influence was pronounced. The hearsay heightened fears of disloyalty by those not sharing his party allegiance and reinforced his predilection for trusting personal allies, rather than the structures of government. His willingness to accept unauthorized information even before he had any authority, and to embrace those acting outside the system, signaled the start of the President’s unfortunate mingling of informal political ways with the military’s stricter means.53

Colonel Elmer Ellsworth’s Chicago Zouaves, pencil, by Alfred R. Waud, 1861

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

The Death of Col. Ellsworth,

hand-colored lithograph, Currier & Ives, 1861

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

As if to underscore the point, a diminutive twenty-three-year-old named Elmer Ellsworth was also invited on the train trip. Ellsworth, a Lincoln enthusiast who had helped in the election, was besotted by military lore. He had put together a drill team of Chicago cadets loosely based on French Zouave companies in North Africa, including their colorful dress of embroidered jackets and loose pantaloons. The company toured Northern cities, entertaining crowds with marching formations and acrobatic stunts. After Lincoln’s election Ellsworth hastily mustered a group, composed mainly of New York City firemen, to defend the capital. When the newly formed Eleventh New York Infantry marched into Washington, the troop received a personal welcome from Lincoln. Ellsworth styled himself their colonel, but he was a parade-ground warrior, ignorant of combat. Nonetheless, one of Lincoln’s first official acts was to nominate Ellsworth for two inappropriately high posts in the War Department. Attorney General Edward Bates advised the President that he did not have the power to do this, and concerned Republicans warned it presaged a “reign of mediocrity and imbecility”; nonetheless, Lincoln remonstrated that he was “pressed to death for time and don’t pretend to know anything of military matters,” ordering Bates to “fix the thing up so that I shan’t be treading on anybody’s toes.” The ludicrousness of this was not lost on the nervous nation. “Old Scott is to resign in favor of Col. Ellsworth,” teased humorist Artemus Ward. “Col. Ellsworth is only thirteen years of age.”54

Scott was seriously worried about the boasting Ellsworth, whose “hard set” of men had trashed their quarters in the Capitol and terrorized townspeople. Lincoln, too, cautioned Ellsworth on the “great delicacy” of the situation, saying he wanted nothing done that might alienate still loyal Virginians. Their concerns turned out to be justified.55 A few weeks after the bombardment of Fort Sumter, the flamboyant “colonel” circumvented orders by wrenching a rebel flag from atop a Virginia hotel—a reckless, amateurish act that cost him his life. Ellsworth’s compatriots—“wild with rage”—nearly burned down the town. His body was taken to the White House and laid in state in the East Room, where a mournful president sat in silence at his feet as military officers stood at command. The nation pronounced Ellsworth a martyr, but the undisciplined move actually exacerbated tensions at a sensitive moment, something Lincoln acknowledged.56

Colonel Elmer Ellsworth Lies in State in the East Room, pencil, by Alfred R. Waud, May 25, 1861. The people shown are numbered as follows: 1. General Winfield Scott; 2–3. general officers; 4. Edwin Sumner; 5. reporters; 6. President Abraham Lincoln; 7. William Henry Seward; 8. officers; 9. Reverend Smith Pyne.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Ellsworth was probably not at the reception on March 12, for he was a militia man, outside the regular army. However, the President’s other new favorites—Sumner, Hunter, Hazzard, and Pope—were among the company. The rest of the officers were largely unfamiliar to Lincoln. He knew Scott, of course, and had glimpsed men like Colonel Charles Stone, who was called to Washington to organize local volunteers guarding the inauguration. One of the few Lincoln had previously met was Lieutenant Colonel Robert E. Lee, standing about a third of the way down the line. They had served together as “managers” for President Zachary Taylor’s 1849 inaugural ball, in a day when both men embraced Whig principles. Lincoln was a congressman at the time and Lee, a kinsman of Taylor, had just returned with honors from the Mexican War. While it is doubtful that Lincoln and Lee knew each other well, they must have had at least a passing acquaintance.57

Robert E. Lee, retouched photograph by Mathew Brady, c. 1859

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

The lanky president and booming Scott aside, Lee was arguably the most striking figure in the East Room. His commanding presence had been noted since he was a West Point cadet, and his magnetism included social charms as compelling as his military skill. Lee enjoyed a reputation for cool bravery, most recently showcased in his near perfect operation against John Brown’s insurrection at Harpers Ferry. This was not the silver-bearded figure so familiar to generations of Americans, but a man of matinee-idol looks, with curling black hair, a neat mustache, and an easy, “brilliant” smile. He was a particular favorite of Scott, with whom he had fought in Mexico. It was a mutual admiration that caused some chatter within the officer corps. In Scott’s eyes “even God had to spit on his hands when he made Bob Lee,” sarcastically commented one colleague.58 The general had called Lee home from Texas in February, and it was widely rumored that he would be given a prominent position.

Promotion was not on Lee’s mind at this time, however. In March 1861 he was as troubled as Lincoln at the idea of dismantling the nation. Like the President and Joseph Holt, he saw disunion as a recipe for weakness, and he worried “whether we are to continue as a united powerful & prosperous nation, or to be divided into separate communities, feeble at home, powerless abroad, wrangling, quarreling, fighting & destroying each other.” Friends reported that the normally unflappable Lee openly wept when he heard Texas had seceded. Now he was pressed by the weight of conflicting allegiance: to his state, his profession, his political principles—and to his cruelly divided family.59

The intricate network of relatives shared by Lee and his wife, Mary Custis Lee—a great-granddaughter of Martha Washington—was nearly unparalleled in its proud service to Virginia. They had also been instrumental in creating a strong and secure central government for the United States. Lee’s own father, Revolutionary War hero Light-Horse Harry Lee, had proposed that the Constitution open with the words “We the People” rather than the more ambiguous “We the States.” Most of Lee’s relatives from his own generation opposed disunion and many were actively working to restore the old compact. The day before Lincoln’s reception, Williams Carter Wickham, whose mother was Lee’s first cousin, wrote a plaintive note to Scott, begging him to do all in his power to aid Virginia conservatives who were fighting secession. A brother-in-law, William Marshall, was a Republican stalwart who had been recommended for attorney general in the Lincoln cabinet. Marshall’s wife, Anne Lee Marshall, never spoke to her brother again after Lee made his fateful decision to join the South. Even Lee’s immediate family was Unionist. A daughter reported that when Lee told his wife and children he had resigned from the United States Army, the pronouncement was so distressing that they faced him in stunned silence. Yet a brother, Charles Carter Lee, was a fanatical sectionalist, and some of the younger family members were eager to mark themselves with distinction in the rebellion. The schism in the Lee family was evident in the lineup before Lincoln, for in addition to the troubled lieutenant colonel, the group included his cousin, Major John Fitzgerald Lee, then judge advocate of the Army, and Robert E. Lee’s eldest son, Custis, both of whom were leaning against disunion. Major Lee would retain his post, and his brother, Samuel Phillips Lee, a senior naval officer, served the Union throughout the war.60