2

PFUNNY PFACE

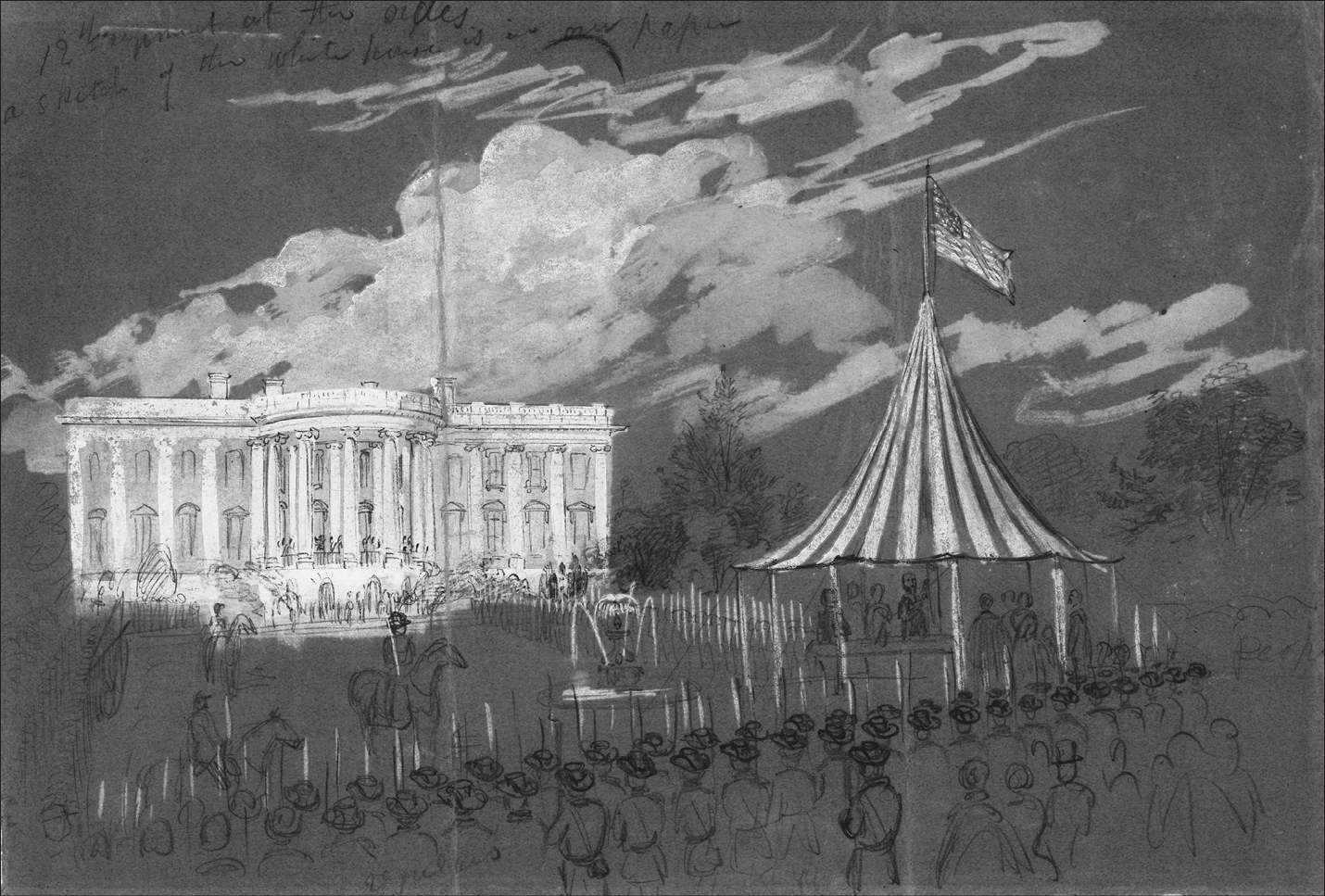

The President was hurrying across the South Lawn of the White House. Abraham Lincoln’s strides were long and loping, but his face was pensive. It was a fine day in late June 1861, and he looked forward to inaugurating a new Marine bandstand. The young soldiers had tacked together a makeshift marquee to stage their performances and a crowd stood in festive anticipation on the close-cut grass. Lincoln liked martial tunes and the gaiety that surrounded such occasions. His task that afternoon was an enjoyable one: to run the Stars and Stripes up the new flagpole, giving a much needed morale boost to the worried nation.1

Lincoln proceeded through a crowd of uniformed soldiers on the lawn. The Marine detachment was there, of course, but so were band members from the Twelfth New York Regiment, and an honor guard from the Third U.S. Infantry Division. These were not the first military men the President had met that day, however. He had just left a tense discussion with his senior commanders, a debate over the steps needed to end the rebellion quickly. General Irwin McDowell was recommending a swift movement against rebel forces at Manassas Junction, some twenty miles from Washington. General Winfield Scott disagreed with the plan, maintaining that the troops were undisciplined, unready, and unfit for battle. Instead he advocated a choking blockade on the Mississippi, a lengthier process, but one Scott felt would more effectively subdue the Confederacy. Lincoln and some cabinet members shook their heads at these slow campaign proposals. The Northern public wanted to avenge the April 12 insult at Fort Sumter, wanted to teach the impertinent rebels a swift lesson. The Southern boys were just as green as the Yanks, Lincoln reasoned, and the country was growing impatient. As in so many instances, the commander in chief looked first to political considerations to shape battle strategy. The nation’s mood called for action.2

The President was still pondering this as he walked into the sunshine with Secretary of State William Seward and Generals Scott and Joseph Mansfield. He was also preoccupied by the message he would deliver to Congress in a few days. Like the public, the legislators wanted an explanation for the slow military response. Moreover, Lincoln would have to defend the unparalleled—indeed possibly illegal—measures he had authorized in the first months of his presidency. In the heat of the moment Lincoln had taken on exceptional powers, justifying them through his authority as commander in chief and the constitutional responsibility to see that the laws were faithfully executed. Without statutory authorization he had approved actions that ranged from suspending the writ of habeas corpus in several places and arresting persons who were “represented to him” as prospective traitors, to increasing the Army well beyond its authorized size. Lincoln was an attorney who respected the law and he thought these unusual moves were warranted by the crisis. Nonetheless, they were irregular. The bright bunting and trilling melodies on the South Lawn would be rendered meaningless if Lincoln’s extraordinary acts undermined the values they symbolized.3

Lincoln Raises the Flag at the White House, pencil, by Alfred R. Waud, June 29, 1861

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

An observer that day noticed Lincoln’s “abstract and serious eyes” and sensed that the President had “withdrawn to an inner sanctuary of thought.” The onlooker remarked something else as well: some part of Lincoln was sizing up the situation, cannily regarding the flagpole and the arrangements, and trying to figure out how he was going to get that “heap of stuff through the hole at the top of the partition.” The marquee looked something like a carelessly constructed circus tent, with the mast running through a small opening at the top, allowing barely enough room for the standard to squeeze through. The flag itself was a ceremonial one, taken from the war steamer USS Thomas Freeborn, which two days before had been engaged in a naval skirmish at Mathias Point, Virginia. The rebels had won the day, harvesting the first naval death of the war by repulsing the Union ships and killing the Potomac flotilla’s commander. Not only were these associations sobering, but the flag was immense. Measuring nearly seven by nine feet, it was far too large and heavy for the unstable new flagstaff.4

The President certainly wanted the ceremony to go off well. Reverend Smith Pyne from St. John’s Church across Lafayette Square had been invited to give the invocation, and the regimental brass was already sounding the national anthem’s opening stanza. In previous months, at similar events, Lincoln had given stirring tributes to the banner and all it represented. He had told audiences that he considered it his sacred duty to maintain “every star and stripe of the glorious flag,” and that he had pondered the original thirteen stars, what they meant, and how the field had expanded to thirty-four. Each new star on the flag, he noted, “has given additional prosperity and happiness to this country.” His sentiments were echoed on postal envelopes, which patriotically declared “Not a Star Must Fall.” At an emotional post office opening, the chief executive had spoken about the honor of raising the flag, how it had “hung rather languidly about the staff” until “a glorious breeze soon came and caused it to float as it should.” Lincoln concluded with the hope “that the same breeze is swelling the glorious ensign throught [sic] the whole nation.”5

“Not a Star Must Fall,” Civil War envelope, c. 1861–62

WARREN E. SAWYER PAPERS, THE HUNTINGTON LIBRARY

So the band played, and the Reverend Pyne prayed, and Lincoln stepped forward to hoist the Stars and Stripes above the rickety gazebo. Then, the very problem he had feared materialized in the most mortifying fashion. As he pulled on the cording, the huge flag caught between the pavilion and the pole and “stuck so fast that the President had to tug away with all his strength.” Lincoln’s powerful arms did manage to raise the ungainly material, but when Old Glory appeared above the crowd, “lo! the upper stripe and 4 of the stars were torn off & dangling [from] the rest of the flag.” One witness thought five stars had flown off; another believed the entire flag had been shredded. It was painfully reminiscent of satirist Artemus Ward’s recent commentary in the new humor magazine Vanity Fair: “Feller sitterzens . . . the black devil of disunion is trooly here, starein us all squarely in the face! . . . Shall the star-spangled Banner be cut up into dishcloths?”6

Lincoln also tried to make light of the mishap. A few days later, at a similar ceremony before the Treasury Building, he remarked that he understood his job was to hoist the banner “which, if there be no fault in the machinery, I will do.” Once raised, he added, the people would have to do their part to keep the national standard afloat. But even the President’s closest friends, who had gathered on the White House lawn for a jolly evening concert, were unsettled by the implications of the ripped flag, representing as it did the rent condition of the Union, and Lincoln’s inability to mend the tattered nation. “A bad omen, as all thought,” noted Benjamin French, his loyal commissioner for public buildings. “A bad augury,” echoed the Chicago Tribune, adding that the damaged flag did not show the half of it, as eleven states had actually been torn from Union. Superstition and inference weighed heavily on the spectators. The discomfort was only relieved when a plucky Marine advised the President that he should not worry too much about the dangling stars. “Never mind,” said the serviceman, “we can sew ’em on again.”7

One of the striking things about the flag-raising tale is that it is so little known. This is surprising, since the documentation is excellent and the story itself both humorous and haunting. Its symbolism is so pronounced that it might well have become a venerable part of the patriotic canon. Yet it is not one of the stock anecdotes about Lincoln. Perhaps this has been conscious—the image of a president wrenching apart the nation’s flag just as his country embarks on fratricidal war is too unsettling to be the stuff of popular lore. It may have been suppressed at the time by administration-friendly publications such as the Daily National Intelligencer, which declined to mention the incident in its coverage, noting instead that the “evening was pleasant and every thing passed off happily.” The story has been edited out of later publications as well: Commissioner French’s eyewitness account was not included in printed collections of his papers, and modern biographers have ignored the incident. Nevertheless, it is a tale worth telling, not only for its ominous overtones, but because it is exactly the kind of portentous yarn that Lincoln himself liked to spin.8

Recollections of Lincoln, particularly those that appeared after his assassination, are notably unreliable and frequently at odds with accounts written as events unfolded. Dimness of memory, grief, and self-conscious attempts to sanctify the “martyr-president” all undermine their historical value. Mary Todd Lincoln noted this soon after her husband’s death: “There are some very good persons, who are inclined to magnify conversations & incidents, connected with their slight acquaintance, with this great & good man.” But one characteristic clearly impressed nearly everyone who had even the briefest contact with Lincoln, and there is such a critical mass of similar accounts that they must be taken seriously. That was his great fondness for storytelling, and the way that he used his skill as a raconteur to enhance both his personal and political power.9

People remembered Lincoln trading yarns with cronies in Indiana and Illinois, amusing fellow politicos in the Capitol’s back rooms, joking with soldiers in the field, or breaking up cabinet meetings to read from his favorite humorists. These are among the most endearing images of the sixteenth president, the delightful human element that has created a rapport across the centuries. At certain points in his presidency, Lincoln became almost a caricature of himself in this regard, yet his penchant for wit and parable, for the apt reply or saucy joke, was so natural that whatever ulterior purposes his tales served, they seem to have been grounded in a genuine love of laughter.

Men particularly liked Abe’s stories, and liked the fact that they tickled the teller as much as the listener. “He is [of] a gay & lively disposition, laughs & smiles a great deal & shows to most advantage at such times,” wrote John Henry Brown, an artist who traveled to Springfield in 1860 and regretted that he could not depict this effervescence in the campaign portrait he was painting. In anticipation of a good laugh, Lincoln apparently became oblivious to expected social composure. He liked to rub his trouser leg with delight or run his fingers through his bristly black hair until it stood out in all directions; and when the punch line came, he would double up until “his body shook all over with gleeful emotion” and “drawing his knees, with his arms around them, up to his very face,” he would let out a jagged eruption of high-pitched laughter.10

As remarkable as these gyrations were, what impressed Lincoln’s audiences most was the transformation of his face when he turned to jesting. The normally coarse features, the air of aloofness or distraction, the sadness that suffused his countenance, would soften when he looked up “with his peculiar smile and eye-twinkle” to recall a story. Noah Brooks, a newspaperman who spent a good deal of time with the President, wrote that “[f]ew men ever passed from grave to gay with the facility that characterized him,” and a military confidant described how his “small eyes, though partly closed, emitted infectious rays of fun.” Even his less admiring contemporaries, like the journalist and legislator Donn Piatt, who described Lincoln’s face as “dull, heavy, and repellent,” acknowledged that it “brightened like a lit lantern when animated.” (The winning smile may in fact have been a gap-toothed, jack-o’-lantern grin, for we know that Lincoln had at least twice submitted to the dentist’s pliers.) He had a peculiar habit, as well, of screwing up his face and wrinkling his nose, then screaming with laughter until, as a loyal Republican visitor noted, the President resembled a wild animal—an “affinity with the tapir and other pachyderms.” Still, the transformation was beguiling. As funny as the jokes were, it was Lincoln’s way of sharing them, his “unfeigned enjoyment,” that made them memorable. “There was a zest and bouquet about his stories when narrated by himself that could not be translated or transcribed,” remembered one friend. “The story may be retold literally, every word, period and comma, but the real humor perished with Lincoln.”11

Some believed Abe Lincoln inherited the storytelling gift from his father, indeed thought Thomas Lincoln outshone his son in this respect. Wherever it was acquired, it soon became a defining part of the long-limbed Midwesterner’s character. Like so many other aspects of Lincoln, we know of it largely through secondhand information, for, interestingly, it does not permeate his own writings. There is little amusing in the papers that have been left to us—most are wooden documents, often clumsily written, unless highly polished for political purposes. As a younger man, he experimented with satire, publishing some barbed opinion pieces in local papers, or occasionally producing a ribald poem or pointed commentary for a public statement. Sometimes these got him into trouble. In 1842, for example, he went overboard in his lampoon of a rival politician named Shields, landing with an awkward challenge to a duel. Lincoln’s wit was evident at that event as well, however, for when he was allowed the choice of weapons he demanded “cavalry broadswords of the largest size” brandished from a narrow plank, rendering the encounter as ridiculous as possible. Many of these early mockeries seem adolescent—a kind of rustic gasconade—and Lincoln had largely dropped them by the time he became a serious contender for national office. By then the smart aleck in him had matured into a wryer, more sophisticated wit. There is very little levity in the papers of his presidency, though he occasionally lapsed into sarcasm when exasperated with his generals. Scornful remarks like the one to George McClellan—“if you don’t want to use the army I should like to borrow it for a while”—only diminished respect for him in military circles, however, and this kind of taunting letter also became rarer as the years went on.12

Instead, Lincoln’s legacy of fun has come to us through the oral tradition. Abe’s listeners fondly remembered the yarns told from atop stumps or around a smoky fire, and repeated them to others. Many of the jokes seem to have lost their context or punch after so many decades, but some are still delightfully fresh. Most of them came from Lincoln’s experience among country folk, and even after years in the spotlight, he still relied on blustering preachers, unscrupulous millers, or hogs mired in mud to make his point. He wove many strands together in his tales—fables, allegories, and stories grounded in metaphor—but always with an ear for homely phrases and an eye to the familiar scenes of life. “He had a marvelous relish for everything of that sort,” recalled an Illinois acquaintance. “He always maintained stoutly that the best stories originated . . . in the rural districts.” Lincoln was not above the social prejudices of his region, and mercilessly mimicked Irishmen, Dutchmen, and African Americans in many a gag line. He knew the cadence of frontier speech—the lingo of flatboat men and Yankee peddlers and Negro minstrels—and used their expressive language to portray the logical illogic of the unschooled. Lincoln also relished the absurd, in speech and in simile. “No one could ever use the term fac simile in his presence, without his adding ‘sick family,’” stated a colleague from Lincoln’s circuit-riding days. Sometimes he coined unique words or novel phrases to give life to a particular character or idea. Meddlesome people he called “interruptuous”; those who were easily duped were “dupenance.” Albert B. Chandler, a young man who kept a journal while working at the War Department telegraph office, noted how peculiar names and alliterations caught the President’s eye, and how he would repeat them over and over until they were fixed in his mind. One night Lincoln laughed with the boys over an invention that used a trapdoor to rob a chicken of its newly laid egg, inducing her to produce another. Its title—“The Double Patent Back-Action Hen Persuader”—set him rocking on the legs of his chair.13

Lincoln also liked to deflate the self-important or highly placed. Likening them to ignorant (if shrewd) hicks was a handy way to accomplish this. He compared his cabinet members to skunks or pumpkins, and rival Democrats to a squirrel hunter shooting in desperation at a louse dangling before his gun sight. When pressured by adversarial religious sects, Lincoln regaled his cabinet with tales of a Presbyterian minister who denounced Universalists for believing that all men could be saved. “We brethren,” fumed the Presbyterian, “we look for better things.” In 1863, after the long preparation for bombarding Charleston ended in a fizzle, Lincoln reproached Admiral Samuel Du Pont by telling him he felt like a hungry man who had been made to stand through a very long grace, only to be served a miserable plate of soup. And the chief executive dismissed Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase’s ambitions to take over the presidency as just like a “horsefly on the neck of a ploughhorse—which kept him lively about his work.”14

Lincoln appears to have been a natural raconteur, but his performances were not entirely spontaneous. Several friends remarked on the conscious effort he made to hone his comic skills, both to tickle the audience and to sharpen his points. One remembered that Lincoln quickly sized up his listeners, brought out new and appropriate material, and never “vexed the dull ears of a drowsy man by thrice-told tales.” An army officer claimed the President explained his method for holding attention by saying that there were two ways to tell a story. “If you have an auditor who has the time and is inclined to listen,” explained Lincoln, “lengthen it out, pour it out slowly as if from a jug. If you have a poor listener, hasten it, shorten it, shoot it out of a pop-gun.” There is nothing particularly insightful about this observation: every good comedian knows that gauging an audience is the secret to packing a punch. Lincoln’s delightfully expressive language, however, makes it a memorable anecdote. Apparently, the President also chose the timing of his routines and balked at performing on demand. When a New Yorker visiting the presidential summer retreat begged for “one of your good stories,” he was chastened by Lincoln’s curt refusal, and the remark that his stories were not a carnival act, but a useful way of directing discussion.15

During Lincoln’s lifetime, a number of books appeared with titles like Old Abe’s Joker (1863) or Old Abe’s Jokes (1864). They purportedly contained original Lincoln material, but most of their contents were actually tired, recycled jests. A journalist named Alexander McClure, who claimed to have an intimate relationship with the President, later produced an anthology of Lincoln’s stories, but few can authoritatively be traced to him. One historian who made a detailed study of bons mots attributed to Lincoln found that many had been circulating literally for centuries, but that “Old Abe” had a knack for shaping their context and making them his own. Lincoln himself told Noah Brooks that only about one-sixth of the stories credited to him had actually been his invention. “I don’t make the stories mine by telling them,” he said, laughing. “I am only a retail dealer.”16

It seems clear, however, that Lincoln actively looked for new stories. His compatriots in Illinois remembered that he keenly took in every comical episode or bizarre name, and loved to collect gossip at local fairs or minstrel shows. The jokes that can be authentically attributed to him show that he picked up material wherever he found it: in the literature of the day, or from political cartoons and offhand remarks. Some said that he kept a file of the best ones in his desk. A general who traveled with Lincoln was amused to see the lanky executive sprawl across the deck of a boat to cut an absurd article out of a newspaper and then read it with great glee to every member of the party. A New York politician told how the President held up a White House receiving line for an apparently intimate conversation with one attendee. When the tête-à-tête ended, a curious crowd pressed the man for details and learned that he had shared an anecdote a few days before “and the President, having forgotten the point, had arrested the movement of three thousand guests in order to get it on the spot.”17

What seems to have been truly original were Lincoln’s clever quips, the one-liners that gave him a reputation for shrewdness and quick repartee. These witticisms were widely replayed and admired at the time, and still please us today. Take, for example, the remark that he could not execute those who ran from battle because it “would frighten the poor devils too terribly to shoot them,” or his comment that trying to get the Army of the Potomac to move was “jes like shovlin’ fleas!” When a captain was court-martialed for voyeurism, Lincoln could not resist playing on the name of Count Piper, the Swedish ambassador to Washington, with a double pun: the guilty officer, he told John Hay, “should be elevated to the peerage . . . with the title of Count Peeper.” Then there is his wonderful retort to Senator Benjamin F. Wade, who stormed the White House in the tense days of 1862, barking that the President was leading the country to Hell, and that in fact they were within a mile of it at that very moment. “Yes,” Lincoln replied, thoughtfully gazing out the window, “it is just one mile to the Capitol.” It was this kind of delicious tidbit that launched Lincoln into the enduring pantheon of American wits, alongside Benjamin Franklin, Mark Twain, and Will Rogers.18

Some of Lincoln’s sayings and aphorisms were simple country corn, but a great number were also smutty. The witnesses are too many to doubt that Lincoln relished lewd scenes and double entendres. Illinois friends remarked that he had “a Great passion For dirty Stories,” that his mind “ran to filthy stories—that a story had not fun in it unless it was dirty,” and that “the great majority of Lincolns stories were very nasty indeed.” A fellow lawyer claimed that when he once asked why Lincoln did not collect his anecdotes and compile a book, Lincoln drew himself up and replied, “Such a book would Stink like a thousand privies.” When the writer Nathaniel Hawthorne visited the White House in July 1862, he recorded conversations that “smack of the frontier freedom, and would not always bear repetition in a drawing-room.” (Hawthorne cut them from his article for the Atlantic Monthly.) Walt Whitman apologized to friends in 1863 for Lincoln’s crudeness by saying that “underneath his outside smutched mannerism, and stories from third-class country barrooms,” there was some practical wisdom. Hugh McCulloch, Lincoln’s last treasury secretary, was another who allowed that “the stories were not such as would be listened to with pleasure by very refined ears, but they were exceedingly funny.”19

Some of the ribald stories have been left to us. Most seem sadly juvenile, filled as they are with outhouse pranks, vomiting drunks, sexual high jinks, and bare behinds. Few are ennobled by illuminating insights or memorable lines, and, at least in the retelling, hardly elevate Lincoln to the level of a backwoods Chaucer. At best they contain some simple, clever puns. “How is a woman like a barrel?” ran one Lincoln ditty from the age of coopers and crinolines. “You have to raise the hoops before you put the head in.” Another story circulated by Lincoln told how the great Revolutionary hero Ethan Allen traveled to England, where many Britons made fun of the Americans. One day they hung a picture of George Washington in a “Back house” where Allen would see it. When he made no comment, they finally asked if he had recognized the likeness. Allen replied that he thought it very appropriate for Englishmen to see it there because “their [sic] is Nothing that Will Make an Englishman Shit So quick as the Sight of Genl Washington.” Another moment of indelicacy was recorded at the War Department, where one night the President sat reading a stack of telegrams. When he came to the bottom of the pile he announced: “Well, I guess I have got down to the raisins.” Puzzled, the telegraph operators asked what he meant. He explained that a little girl he knew, having eaten too large a share of treats filled with raisins, became violently sick. After “an exhausting siege of throwing up, she gave an exclamation of satisfaction that the end of her trouble was near, for she had ‘got down to the raisins.’”20

Leonard Swett, who concerned himself with the sixteenth president’s reputation, was among those who winced at such lore, but he proposed that there was no vulgarity in Lincoln’s character, only the desire to make his point. “It was the wit he was after—the pure jewel, and he would pick it up out of the mud or dirt just as readily as he would from a parlor table.” Historians of the apologist school have also sometimes downplayed the off-color jokes, feeling they might interfere with the heroic portrayal of their subject. (Biographer David Herbert Donald was among those who regretted that some of the rougher tales had been lost through prudery.) But scatological jokes only appeal to a certain kind of jester, and scrubbing Lincoln to the point of one-dimensionality cannot take the salt from his skin. Lincoln’s stories were never of the tittering, parlor variety but were made for a thigh slap and a guffaw. Indeed, much of the pungency in his rural style came from its earthiness.21

Whether silly, spicy, or sage, Lincoln’s jokes served several purposes for him. The most straightforward, of course, was to indulge his fondness for a chuckle. It was not just that he wanted an audience—though it is clear that he craved that too. What seemed to animate him was the tonic of hilarity. He felt a “deep satisfaction expressed in the ha ha,” one admiring friend attested. Both before and during his time in public office he went to music halls and minstrel shows, treated visitors to juicy bits from his favorite comic stories, and surrounded himself with others who liked to laugh. His secretary John Hay recorded a wonderful scene of the President wandering the halls at midnight dressed only in nightclothes (“his short shirt hanging about his long legs & setting out behind like the tail feathers of an enormous ostrich”) in order to recite an inane poem. Lincoln indulged the antics of his children, attended their magic lantern shows (they sent him complimentary tickets), and was vastly amused by a cabin they built on the White House roof, dubbed the “Ship of State.” He was merry at receptions, and visitors recalled hearing a good deal of laughter coming from his cabinet rooms. He even bantered while being shampooed. He had a strong sense of the ridiculous, and on occasion relaxed by inviting Tom Thumb or “Hermann the Prestidigitateur” to perform after dinner, liking the ludicrous spectacles, and taking part in the performances. In these situations, wrote an administration official, the beleaguered president looked “natural & easy. He is Old Abe & nothing else.”22

Many have thought that Lincoln’s pursuit of laughter was a much needed antidote to his introspective, melancholy disposition. The swift change in his countenance, from shadow to sunshine, argues for this, as do the observations of long-standing friends, who saw how his moods would shift rapidly within a single day. His closest confidant, Joshua Speed, maintained that telling tales was “necessary to his very existence,” replacing any desire to escape with drink or dice. Longtime law partner William H. Herndon agreed. An eccentric man, Herndon was nonetheless in a position to observe Lincoln at close range. He quoted his partner as saying that if “it were not for these stories—jokes—jests I should die: they give vent—all the vents of my moods & gloom.” Herndon’s curious assessment was that Lincoln was naturally slow-moving and slow-thinking; he needed stimulation not only to chase depression but to increase the flow of blood to the brain and awaken his full productive power. Assistant Secretary of War Charles A. Dana echoed these thoughts, though in less peculiar terms, stating that the “safety and sanity” of the President’s intelligence were maintained through the outlet of humor.23

Those studying Lincoln’s moods have indeed found dangerous dips and erratic behavior, particularly in his younger days. But the dynamics of his psyche have remained elusive. Lincoln, as always, tells us next to nothing—his writings offer little illuminating introspection and few clues about the trials and tensions of his life. Some intriguing studies have concluded that Lincoln’s changeable disposition was the consequence of childhood losses. Others refer to an abnormal homeostasis. Several of Lincoln’s associates related that he took “blue mass” pills, a common remedy of the era for many disorders, and one group of modern doctors has proposed that he suffered mercury poisoning as a result. The medication was concocted from almost pure mercury, in dangerous doses, and could have caused Lincoln’s explosive laughter and unrestrained outbursts of temper, as well as the insomnia, memory loss, and neurological instability that seem to have plagued him. There is no clinical evidence, however, and only shaky historic grounds for any authoritative analysis of Lincoln’s “mercurial” nature. Whatever the cause, sadness and mirth seem inextricably linked in the man. His jokes often pointed up the absurdity of fretting over trivial concerns, or the frivolity of human vanity, and how such disproportion may lead to a wasted life. Perhaps it was this classic overlap of comedy and tragedy, pride and futility, that gave his humor such force.24

Whatever psychological benefits joking had for Lincoln, his storytelling was also a powerful social tool. On the most basic level it made him popular. Community acceptance was important on the rough frontier—a dangerous place where goodwill was crucial for survival, not to mention success. Abe Lincoln was a strange young man there: he looked odd, and he seemed to disdain the pleasures of the local boys. He disliked hunting, drinking, or smoking; shied away from chasing girls; and, as he got older, increasingly made himself a curiosity by climbing trees to read a geometry book or a worn copy of Shakespeare. It was fortunate for Lincoln that he was as physically impressive as he was: those loose-jointed limbs were deceptively strong, and once the hardscrabble crowd figured out that he could outrun, -jump, and -wrestle them, they treated him with respect. But comedy was what made Abe’s company desirable. He was fun and irreverent, and the fellows would gather in little knots to hear him perform. No matter how ludicrous he became, no matter if he wobbled on the line of good taste, his dignity never suffered. He may have been a clown, but he was admired, not reviled. When Lincoln’s career interests grew, his good-natured banter became important for cementing professional friendships. Every politician both craves and needs popularity, and comedy was the way Lincoln first attracted a crowd.25

Humor also gave Lincoln power. It was not just the power to command applause, but the ability to control a situation. As a laboring man he could undermine a strict foreman by luring the field hands from their work for some jesting; as an attorney he influenced decisions in the courtroom—sometimes thwarting justice—by suggesting a droll analogy to the case at hand. His aptitude for homey phrasing that plainspoken jurors could understand earned him a fine reputation for summing up a case, as did his ability to think on his feet. Nor was he above using stagecraft to gain his point. A fellow circuit lawyer described the way Lincoln swayed one jury when there was a seemingly airtight case against his client.

He picked up . . . a paper, from the table. Scrutinizing it closely, and without having uttered a word, he broke out into a loud, long, peculiar laugh, accompanied by his most wonderfully funny facial expression. There was never anything like the laugh or the expression. A comedian might well pay thousands of dollars to learn them. It was magnetic. The whole audience grinned. He laid the paper down slowly, took off his cravat, again picked up the paper, looked at it again, and repeated the laugh. It was contagious. . . . He then deliberately took off his vest, showing his one yarn suspender, took up the paper, again looked at it, and again indulged in his own loud, peculiar laugh. . . . Judge Woodson, the jury and the whole audience could hold themselves no longer, and broke out into a long, loud, continued roar; all this before Lincoln had ever uttered a word.

Needless to say, the prosecution’s case was completely destroyed, though apparently Lincoln took care that the damages paid were fair.26

Lincoln also manipulated his personal conversations by the timing and tenor of his jokes. He could end an interview, sidestep an argument, deflect tension, or buy time for reflection—all by announcing that something “reminded him of a little story.” The astute people around the President understood that he had the last word, that he was leaving them laughing, but they were helpless against his prowess. William Howard Russell, a skeptical British observer of the American scene, attended a dinner soon after Lincoln’s first inauguration at which Attorney General Edward Bates began a diatribe against a minor political appointee. Lincoln quashed the impending quarrel by raising a chuckle with “some bold west-country anecdote,” and while the company was laughing he beat a quiet retreat “in the cloud of merriment produced by his joke.” Pennsylvania Republican Titian J. Coffey was another who admired Lincoln’s ability to stage-manage a situation. “The skill and success with which Mr. Lincoln would dispose of an embarrassing question or avoid premature committal to a policy advocated by others is well known,” he commented. “He knew how to send applicants away in good humor even when they failed to extract the desired response.” Longtime friend and bodyguard Ward Hill Lamon called the jokes “labor-saving contrivances,” whose purpose was to expose a fallacy or disarm an opponent.27

He also knew how to make his point without belaboring it. As Lincoln’s stature grew, he told his stories less to tickle the funny bone than to drive home an argument. His repertoire came to resemble a set of illustrative fables that could clarify issues or persuade detractors. Aphorisms and apologues became a kind of shorthand for him, helping, as Lincoln reportedly told one visitor, to “avoid a long and useless discussion . . . or a laborious explanation.” As a raconteur, for example, he could subtly voice his sympathy for those who quaked under battle fire by telling the story of a private who advised his captain that he had as “brave a heart as Julius Caesar ever had; but some how or other, whenever danger approaches, my cowardly legs will run away with it.” (The commander in chief’s leniency toward “leg cases” became famous during the conflict.) When Lincoln compared the problem of slavery to a venomous snake in bed with a child—a terrible danger, but one that must be handled with skill and caution—it was an analogy that every prairie family could understand.28

However calculated the effort, Lincoln’s effect was clearly very real. He had the knack most coveted by political comedians: first to make his audience laugh—and then to make them think. Even those who sparred with the Lincoln administration understood his gift for winning a debate with a telling phrase. George McClellan, 1861: The President’s stories “were as usual very pertinent & some pretty good. . . . he is never at a loss for a story apropos of any known subject or incident.” Horace Greeley, 1864: “President Lincoln . . . has had no predecessor, who surpassed him in that rare quality, the ability to make a statement which appeals at once, and irresistibly.” Congressman Henry Dawes, a radical Republican: “He was a storyteller, not for the story’s sake, but for the use he could put them to, to clinch an argument, to show up an absurdity as in a looking glass, or to make plain an impossibility.” Dawes once sought the President’s advice about circumventing a knotty political problem. Lincoln replied with a parable. “You were a farmer’s boy and held [a] plow, I guess,” he said. “What did you do when you ran against a stump, drive through and smash everything, or plow around it?” That was all he said, noted the congressman—and that was enough.29

This kind of Lincoln lore seems to indicate that the President profited by a mild approach and soft political invective. However, though he quoted Shakespeare’s warning about the “power to hurt”—how a withering remark could ultimately wither the critic—he did not always heed the caution. Lincoln could, and did, use his verbal agility to crush opponents, as well as to buttress his arguments. At times his attack was savage. He sometimes used sophisticated logic to undermine an argument, but he could also descend into personal assaults, even when the victim was not present to defend himself. This was particularly true in Lincoln’s younger days, when he took on some of the most prominent men in his region, undercutting them on the stump and in the local press, and leaving their reputations in question. For example, Lincoln confronted a celebrated local preacher, Methodist circuit rider Peter Cartwright, not with measured argument but with caustic newspaper attacks, which unjustly accused him of hypocritical acts. Cartwright fought back, but Lincoln, who had hidden behind a pseudonym, escaped relatively unscathed. In another notable case, Lincoln challenged a rival politician named Jesse B. Thomas, employing all his powers of smirking enfilade fire, until his opponent publicly dissolved in tears. The episode, which came to be known as the “Skinning of Thomas,” was something of a cautionary moment; even Lincoln understood that he had overstepped the mark, and took some care afterward to avoid handing up total humiliation.30

Despite his attempts at self-restraint, however, lawyer Lincoln was, in the words of Judge David Davis, “hurtful in denunciation, and merciless in castigation.” He continued to jab at political adversaries, especially pompous or preening men, referring to them as “dogs,” “caged and toothless” lions, or “little great men.” According to one loyal retainer, Lincoln even boasted of his “hits” when he thought he had got the best of a situation. Stephen A. Douglas cringed when encountering the sneering Lincoln during their famous debates: Abe Lincoln’s reasoning could be got around, Douglas maintained, but “every one of his stories seems like a whack upon my back. . . . [W]hen he begins to tell a story, I feel that I am to be overmatched.” The desire to undercut his opponents, by fair means or foul, was part of Lincoln’s inordinate ambition, his unflagging desire to win. It came as handily to him as a half nelson had in the years when wrestling defined his local dominance. Some of this urge to lead by belittling continued into his presidency, when he took delight in deflating the egos of his cabinet and generals, sometimes ungenerously. “Mr. Lincoln,” wrote his ever admiring secretary John Nicolay, “seems always to have been as adroit in answering a fool according to his folly as in silencing the follies of men who consider themselves wise.”31

Thus, for Lincoln, humor was an important weapon, sometimes with a razor-sharp point. At times, it was also a refuge. Lincoln was an intensely self-absorbed person, private and protective. He was not good at small talk and had trouble forming deep bonds. His law partner thought he drew a defensive circle around himself, meant to ward off the curious and shelter him from unnecessary conversation. The comedic act was part of this. It gave Abe a way to connect with people without truly revealing himself. He would “laugh and smile and yet you could see . . . that Lincoln’s soul was not present,” Herndon wrote. Lincoln’s political ally Leonard Swett thought so too. “He always told enough only of his plans and purposes to induce the belief that he communicated all, yet he reserved enough to have communicated nothing.” Martinette Hardin, the sister of Lincoln’s fellow Whig legislator John Hardin, recalled that Lincoln was often mute in genuine discussions, or that he did not respond at all until he could interject a little joke. Moreover, Lincoln’s stories were also prefaced with a kind of disclaimer—that he had heard them from someone else, or read them somewhere—which distanced him from the barbs or bawdiness of the laugh line. Lincoln defended his silence, once saying that although he was a taciturn man, it was more unusual “to find a man who can hold his tongue than to find one who cannot.” Nonetheless, his joshing precluded dialogue, making much of his interaction one-sided. Engaging tales and set-piece routines let Lincoln control a conversation, without truly interacting.32

Storytelling also provided him with a script. The popular impression today is that Lincoln was a master of both beautiful prose and inspired conversation. He worked dutifully at the English language and became a fine writer, but this, like his compelling dramatic talents, was not spontaneous—it was a skill he practiced and honed, one requiring prodigious application and constant revision. All the available evidence during his lifetime shows him to be an awkward conversationalist, with a poor grasp of grammar and elegant expression. He was largely at a loss when he had to speak extemporaneously. Even Lincoln’s admirers saw him as a “country clodhopper . . . always stiff and unhappy in his off-hand remarks,” or praised his political insights while acknowledging his sad lack of grammar. “I wish he would leave off making little speeches,” faithful retainer Benjamin French remarked. “He has not the gift of language, though he may have of western gab.” Two fellow party men noted that he was “not a successful impromptu speaker,” that he was “often perplexed to give proper expression to his ideas; first, because he was not master of the English language; and secondly because there were, in the vast store of words, so few that contained the exact coloring, power, and shape of his ideas.” John Hay, whose veneration for his chief knew few bounds, squirmed after reading the “hideously bad rhetoric” and indecorous language of a pivotal presidential letter and even accused his boss of uncommon dexterity at “snaking a sophism out of its hole.”33

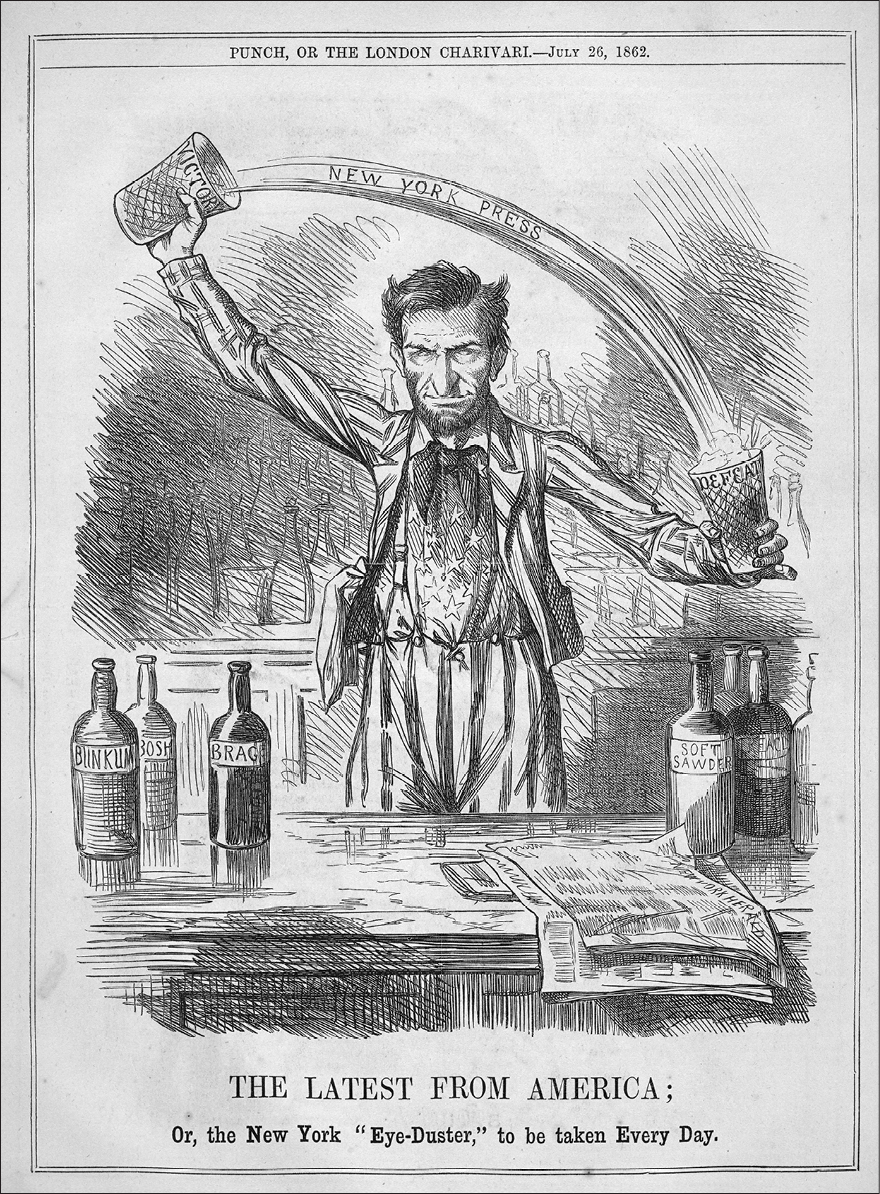

What is remarkable is not that Lincoln lacked communications skills, but that he came so far from such a shaky base. Well aware of his shortcomings, he avoided off-the-cuff remarks and apparently wrote down and committed to memory any appropriate phrases that might serve him. Noah Brooks remembered him struggling to avoid improper or overly quaint phrases. Finding Lincoln laboring at his desk over a manuscript, Brooks was surprised to hear the President say that he had to be “mighty careful” when addressing the nation. He had once used the expression “turned tail and ran,” Lincoln said, which outraged some Bostonians, and he had resolved to give no more unrehearsed speeches. He reiterated this at a fair held in February 1864 to benefit the United States Sanitary Commission. After noting that “a little fraud” had been perpetrated by not telling him he was expected to speak, Lincoln sidestepped the matter by noting that it “was very difficult to say sensible things” and that he had better keep quiet or both he and the country might be in trouble. Even in his penultimate speech, a response to a serenade celebrating Union victory, he made the embarrassing admission that he had nothing to say on the great occasion. The set-piece stories and quips he perfected offered him a sturdy safety net to avoid this discomfort in both formal and informal discussion.34

At times the fund of jokes also provided a shield against those who would make the President himself the object of fun. Humor helped him ward off criticism before it bruised too deeply, as well as maintain much needed perspective. He was a natural target for lampooning—if ever a human seemed formed for ridicule, it was Abraham Lincoln. His unusual height would have been enough to cause comment, but added to this was “the loose, careless, awkward rigging” of his frame; the stooped, shuffling walk; and a shock of coarse, unruly black hair that one amused citizen likened to “an abandoned stubble field.” The prominent nose was clownishly tipped in glowing red. His face had an unfortunate simian cast: more than one observer thought that a president who “grinned like a baboon” was a disgrace to the nation. He paid little attention to his dress and this only increased the opportunities to scoff. Lincoln routinely greeted guests of all rank in scruffy carpet slippers and rumpled suits. One soldier who met the commander in chief thought his clothing was the dirtiest he had ever seen. Another visitor compared him to a shabby undertaker, and when Nathaniel Hawthorne came to call, he was startled to encounter the nation’s highest official in “a rusty black frock-coat and pantaloons, unbrushed, and worn so faithfully that the suit had adapted itself to the curves and angularities of his figure, and had grown to be an outer skin of the man.” What saved the President from being completely ludicrous were his utter lack of pretension, a winning twinkle in his eye, and an ability to impress guests with his sincerity. Hawthorne saw this, and it overrode his surprise at a hairdo that had apparently seen neither brush nor comb that morning; so did a young James A. Garfield, who recognized Lincoln’s peculiar power to impress men with his candor and direct gaze. George Templeton Strong spoke for many when he confided to his diary: “He is a barbarian, Scythian, yahoo, or gorilla, in respect of outside polish . . . but a most sensible, straightforward, honest old codger.”35

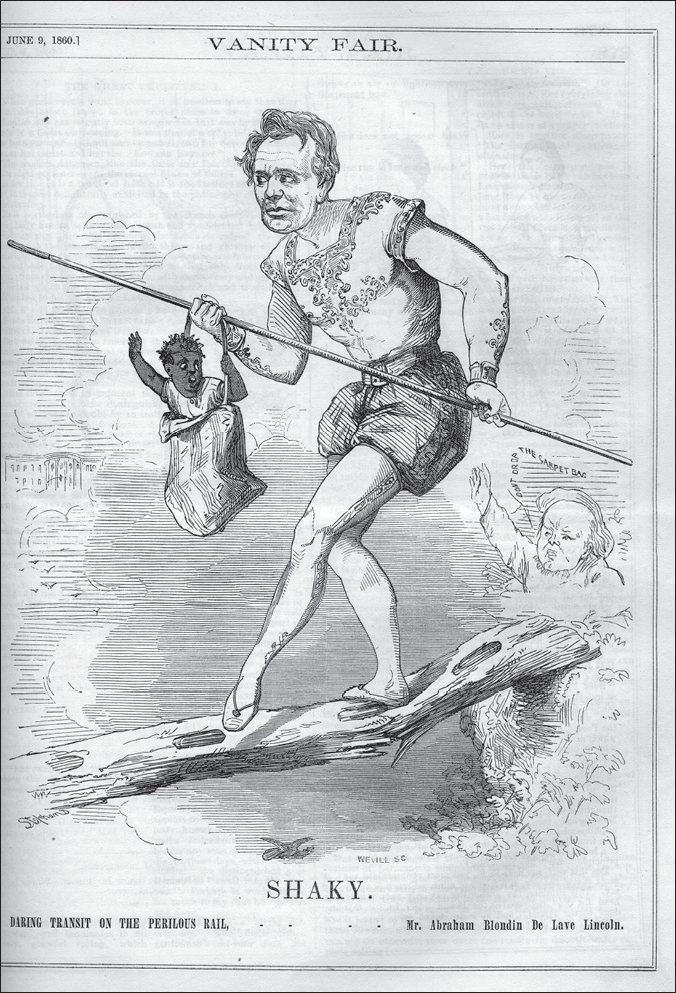

“Shaky,” wood engraving, Vanity Fair, June 9, 1860

Lincoln learned to “whistle off” those who snickered at his appearance or to preempt them with self-mockery. Laughing took the sting from his detractors, overcoming their taunts with an aura of good-humored self-acceptance. An Illinoisan who met Lincoln in 1858 noted that he was just as gangly as reported, but his sharp eyes made it clear that “if a man should insult him he would laugh at him and shame him out of it sooner than to fight him.” When Stephen Douglas tried to gain advantage in the 1858 senatorial election by pointing up his distinguished national reputation, Lincoln admitted that there was not much in his “poor, lean, lank, face” that was presidential. He then adroitly linked Douglas’s “round, jolly, fruitful” countenance to greed, patronage, and corruption. Lincoln also poked fun at his own ungainly figure on horseback, chortled over satirical pieces that pictured him vowing “to split 3 million rails afore night,” and borrowed laugh lines from scornful cartoonists such as the one who pictured him as “Shaky” in Vanity Fair. One wonderful anecdote claimed that when a rival accused Lincoln of being two-faced, he responded: “If I had another face do you think I would wear this one?” Alas!—like so much Lincoln lore—this story is probably apocryphal. More credible is the wisecrack the President made after he contracted a mild form of smallpox in 1863: “There is one consolation about the matter. . . . [I]t cannot in the least disfigure me!”36

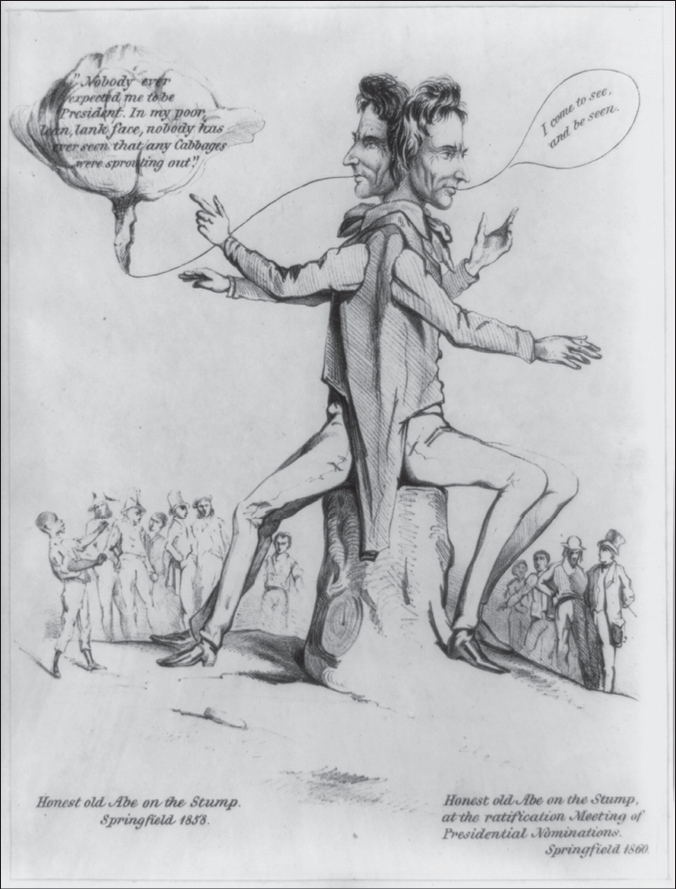

“Honest old Abe on the Stump, Springfield, 1858”; “Honest old Abe on the Stump, at the ratification Meeting of Presidential Nominations, Springfield 1860,” lithograph

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Lincoln effectively shrugged off remarks about his eccentric physique, but he disliked being made to look ridiculous, and he had a pronounced sensitivity to serious criticism. Acquaintances found him “touchy” when his self-esteem was tried: he was “keenly sensitive to his failures and it would not do to mention them in his presence.” When he could not dismiss a slight, he sometimes struck back fiercely. His first foray into satire was a smarty-pants piece of verse that cast doubt on the virility of some local cronies who had chosen not to invite him to a wedding. Lincoln’s early public writings are filled with unconstrained language denouncing the “fabrication and falsehood” of his rivals or deriding them as “not more foolish and contradictory than they are ludicrous and amusing.” The president-elect was embarrassed in 1861 when detractors branded him a coward for surreptitiously entering Washington in order to circumvent threats on his life. That mortification may have caused him to take unwise risks thereafter. Nor was he laughing when Maryland senator Reverdy Johnson questioned his policies toward Unionists in Louisiana, or when he was squeezed by a Christian committee on emancipation, or when his old friend Carl Schurz bluntly criticized the way the war was being handled. Lincoln lashed out at these men, saying that he had been “very ungenerously attacked” and that he mistrusted “the wisdom if not the sincerity of friends, who would hold my hands while my enemies stab me”; he also accused the press of maligning him. “You think I could do better; therefore you blame me already. I think I could not do better; therefore I blame you for blaming me,” he petulantly retorted. In Schurz’s case Lincoln tried to backtrack, making light of the outburst by slapping his knee with a loud laugh and saying, “Didn’t I give it hard to you in my letter? Didn’t I?” But Schurz had already picked up the “undertone of impatience, of irritation” and recognized how defensive the President had become. Herman Haupt, an army engineer whom Lincoln esteemed highly, witnessed a similar explosion when a member of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War frankly told the President how dissatisfied the military was with his leadership. “Stop right there!” the commander in chief shouted, drawing a hand across his chest. “Not another word! I am full, brim full up to here.” It is striking that so many similar outbursts were recorded, since Lincoln also liked to preach a philosophy that advised self-control and the avoidance of “personal contention,” and at times took pains to avoid confrontation. Such explosions help us understand how vulnerable Lincoln could be, how fragile he was under the armor of bonhomie. It appears that the man who had “skinned Thomas” had a thin skin himself.37

Wordplay is part of the comedian’s genius, but another important element is timing. After Lincoln’s death many noted with admiration how perfectly pitched his taglines could be. Unfortunately, just because a witticism is apt does not always make it appropriate. During his lifetime the President faced significant criticism for his near addiction to joking, and for the way it interrupted real dialogue or showed insensitivity to the severity of the nation’s crisis. He reverted to flippancy too easily when the business at hand was somber, and he jested with people who were not well acquainted with him, and consequently liable to misunderstand his levity. As early as 1839, his Illinois constituency showed concern for his “assumed clownishness,” advising Lincoln to give up the “game of buffoonery,” which not only lacked dignity but failed to persuade an audience of his points. In 1861 a British journalist was dismayed to find Lincoln, his legs sprawled over the railing of a veranda, “letting off” one of his jokes to federal officers in the field, apparently oblivious to a menacing Confederate flag waving in the near distance. Military men also frowned at their commander’s inexplicable mirth. William Thompson Lusk, a captain with the New York Highlanders (and a man willing to support Lincoln), was greatly offended in the wake of 1862’s disastrous Virginia campaigns. “The men are handed over to be butchered—to die on inglorious fields,” he protested. “Lying reports are written. . . . Old Abe makes a joke.” The Army was willing to fight, he mourned, but “the brains, the brains—we have no brains to use the arms and limbs and eager hearts with cunning.” A fellow officer echoed the sentiment. “What is to become of us with such a weak man at the head of our government, be he ever so honest?” he queried. “One who . . . turns off things of the most vital interest with a joke?” A Southerner who beseeched Lincoln to take measures to protect Unionists caught in the Confederacy listened patiently while the President trotted out a string of stories. Then he responded candidly:

Mr. Lincoln, this to me, sir is the most serious and all absorbing subject that has ever engaged my attention as a public man. I deprecate and look with horror upon a fratricidal war. I look to the injury that it is to do, not only to my own section—that I know is . . . desolated and drenched in blood—but I look to the injury it is to do to humanity itself, and I appeal to you, apart from these jests, to lend us your aid and countenance in averting a calamity like that.

As Confederate momentum remained unchecked, the Polish-born writer Adam Gurowski acidly summed up the situation: “And so Davis is making history and Lincoln is telling stories.”38

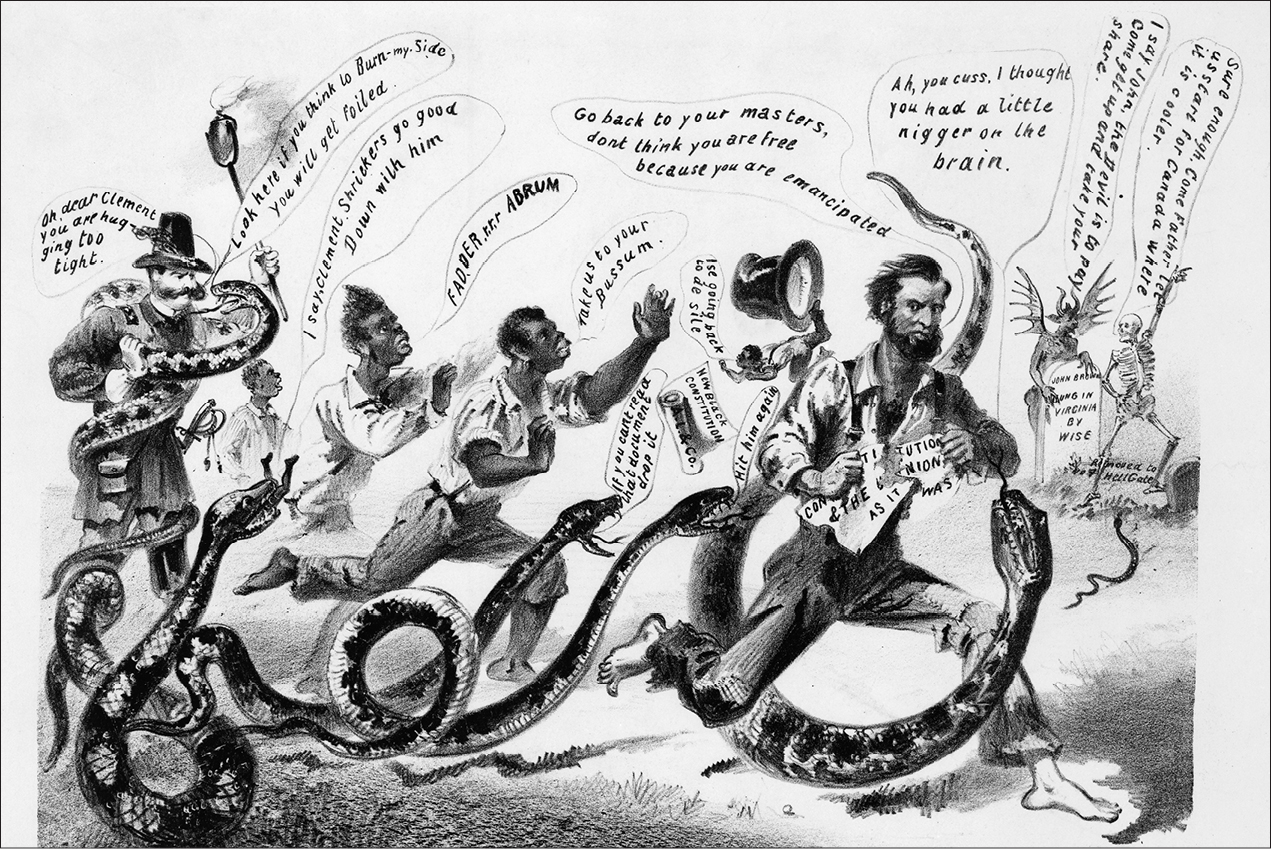

Among those most annoyed by Lincoln’s perpetual joshing were senior members of his government. McClellan, of course, thought anecdotes told by the “Gorilla” were “ever unworthy of one holding his high position.” Salmon Chase was also offended by the constant banter when “danger was too imminent & the occasion too serious for jokes”—as it was during a midnight discussion of desperate reinforcement operations at Nashville in September 1863. Secretary of War Stanton and Senator Henry Wilson simply abhorred the stories, and Stanton, particularly, was not above showing his anger to the President, his staff, or the military brass. Stanton had hoped when he took office that there would be “no jokes or trivialities” and that the contest would be taken in “dead earnest.” He was to be disappointed. Benjamin French, despite his fondness for the man, had to admit that Lincoln’s judgment and timing were often astonishingly poor. After Confederate general Jubal Early made a daring raid on Washington in July 1864, pointing up the impotence of Union intelligence and defensive strategy, French went round to his chief’s office to express alarm. He was regaled with a long Lincolnian story that compared a yokel who thought he saw a wolf’s tail with the Union Army, now so far in the rear of the Confederates “that it is doubtful if they will even get sight [of] their tails.” French got “mad & came away disgusted.” The President showed so little concern for beating the rebels, noted French, that he was jeopardizing the welfare of the country.39

II

To a large degree Abraham Lincoln was able to overcome his curious physical appearance and clumsy perpetual joking through his sympathetic nature. But this personal touch was only felt by the small number of people with whom he actually had contact. The vast majority of the nation knew their chief magistrate through partisan broadsides, or newspaper accounts, some of which were little more than printed hearsay. And by the 1860s elected officials were publicly commented on more than ever before. Americans were not shy about expressing their opinion of a president’s fitness for office, whether justified by firsthand knowledge or not.

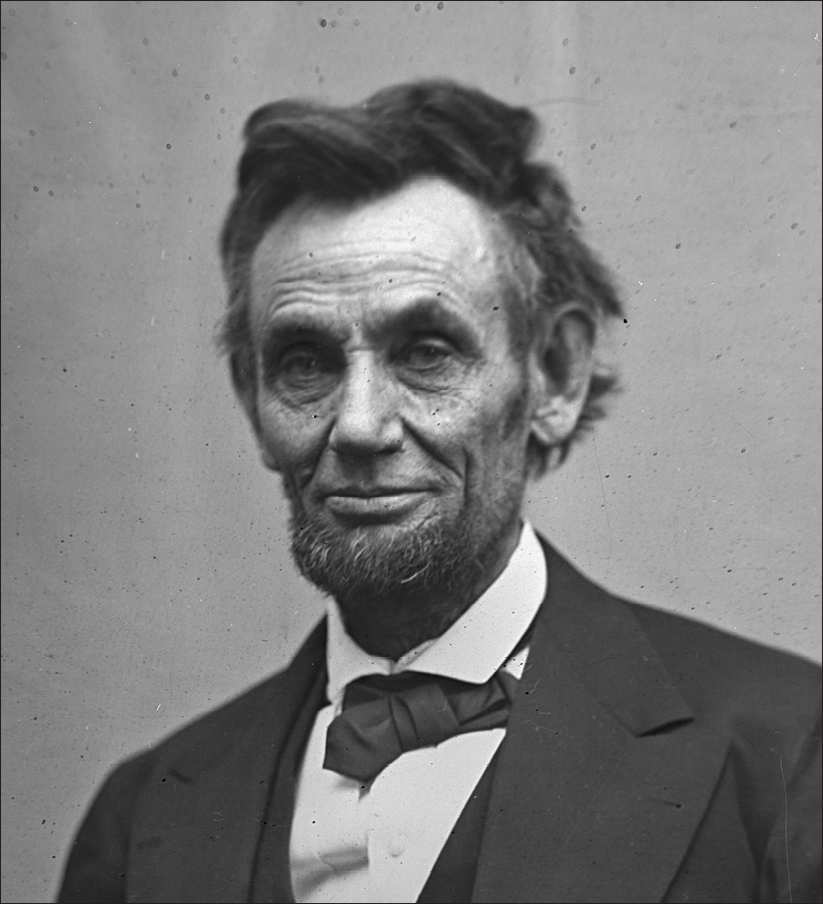

Abraham Lincoln, photograph by Alexander Gardner, February 5, 1863

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Lincoln’s tenure coincided with the rise of photography, and the boost it gave to the cult of political personality. He was the most photographed president to date, and it appears he liked to have his portrait taken. Unfortunately, the camera did not love him. The sharp imagery of the glass plate prints showed every detail of his gaunt face, unruly mane, and tortured necktie. The warts were literally there, and the benevolent expression lost, in all but a handful of pictures. In addition, his flapping appendages and western gaucherie were simply meant for caricature. It was also the golden age of lithography, and the illustrated papers had a field day, in the North as well as the South. Because they could narrate a great deal with a few sketchy lines, using sarcasm or allegory to distill complex emotions or policies, cartoons held a disproportionate influence. They became as emblematic as the Capitol dome, creating stereotypes more potent than a slogan. Moreover, with the telegraph and mails well established, the reach of these images was vast and immediate. The entire nation was able to share an impression or a chuckle at Washington foibles in real time, forming a collective consciousness that could be either unifying or highly divisive. The New York Herald recognized that technology and the popular press had combined to make Lincoln an “eccentric addition” to the gallery of prominent men, for “it is only in the present age of steam, telegraphs and prying newspaper reporters, that a subject so eminent . . . could have been placed under the eternal microscope of critical examination.” It was no longer possible to cover up an unfortunate moment like the misbegotten flag raising—it zipped across the wires in an instant.40

Political satire had, of course, existed for centuries. After all, Machiavelli delighted in exposing the wiles of power-hungry princes, whose professions of goodwill were in absurd contrast to their private ambitions. But political humor had become particularly forceful in the United States, where the most scathing remarks went unpunished, and where growing literacy created a wide audience. By the mid-nineteenth century, poking fun at the nation’s leadership had grown to be a fine art. The paradox between presidential celebrity and its bossy bed partner, the rule of law, was simply too good to pass up. In addition, the colorful trappings of each polling season smacked of farce, nearly begging for a sardonic spree. The campaign of 1840, in which Lincoln participated, was an excellent example. It was almost devoid of substance, the goal of each party being simply to win the spoils of office for itself—and the log-cabin origins of William Henry “Tippecanoe” Harrison, invented by early image makers, were in preposterous juxtaposition to his genteel upbringing. By the time of Lincoln’s election, the spoofs were more fearless and more widespread. The inevitable clumsiness of self-rule and the perpetual cycle of political mischief were kept on prominent display, warning the public not to take its rulers too seriously. In London’s Punch, the comic-strip version of Lincoln, outfitted in striped pants and a star-spangled vest, became confused at times with Uncle Sam (who grew a beard when Abe did), but the image was not meant to elevate the President. Instead, it mocked his inability to hold the Union together.41

“The Latest from America; Or, the New York ‘Eye-Duster,’ to be taken Every Day,” wood engraving by John Tenniel, Punch, July 26, 1862

In a sense Lincoln was the first true media president, though Buchanan had come in for some impressive drubbing during the last days of his administration. Lincoln’s sensitivity about off-the-cuff remarks, and their possible misinterpretation, is one indication that he recognized the burgeoning power of the fourth estate. Another is the way he and Republican leaders took concrete measures to appease newspapermen. Joseph Medill, the influential editor of the Chicago Tribune, for example, advised Lincoln after his 1860 nomination that the party would want to mollify “his Satanic Majesty” James Gordon Bennett, publisher of the critical New York Herald. Bennett’s “affirmative help is not of great consequence,” Medill cautioned, “but he is powerful for mischief.” Medill thought Bennett, who longed for social status, could be bought by a White House invitation or two. It proved not to be so. Like several other prominent journalists, Bennett remained true to the Union, but not necessarily to administration policies. In 1863 Lincoln was still trying, in his words, to “humor” the Herald by giving its reporters advance copies of documents or special access. As time went on, his “management” of the press would edge perilously close to state censorship.42

Lincoln understood that, for the president, public commentary was one of democracy’s more fiery trials. Citizens cherished their right to heckle their leader—to deride not only his policies but his personal traits. The playful slap at authority was a kind of leveling exercise. It stripped down the powerful by implying that their leadership was a hilarious sham that could be knocked away by jeers as easily as by violence. “Democracy,” H. L. Mencken would write, “is the art and science of running the circus from the monkey cage.” It was this, the vaudeville of republican government, that made parody such a forceful expression of popular will.43

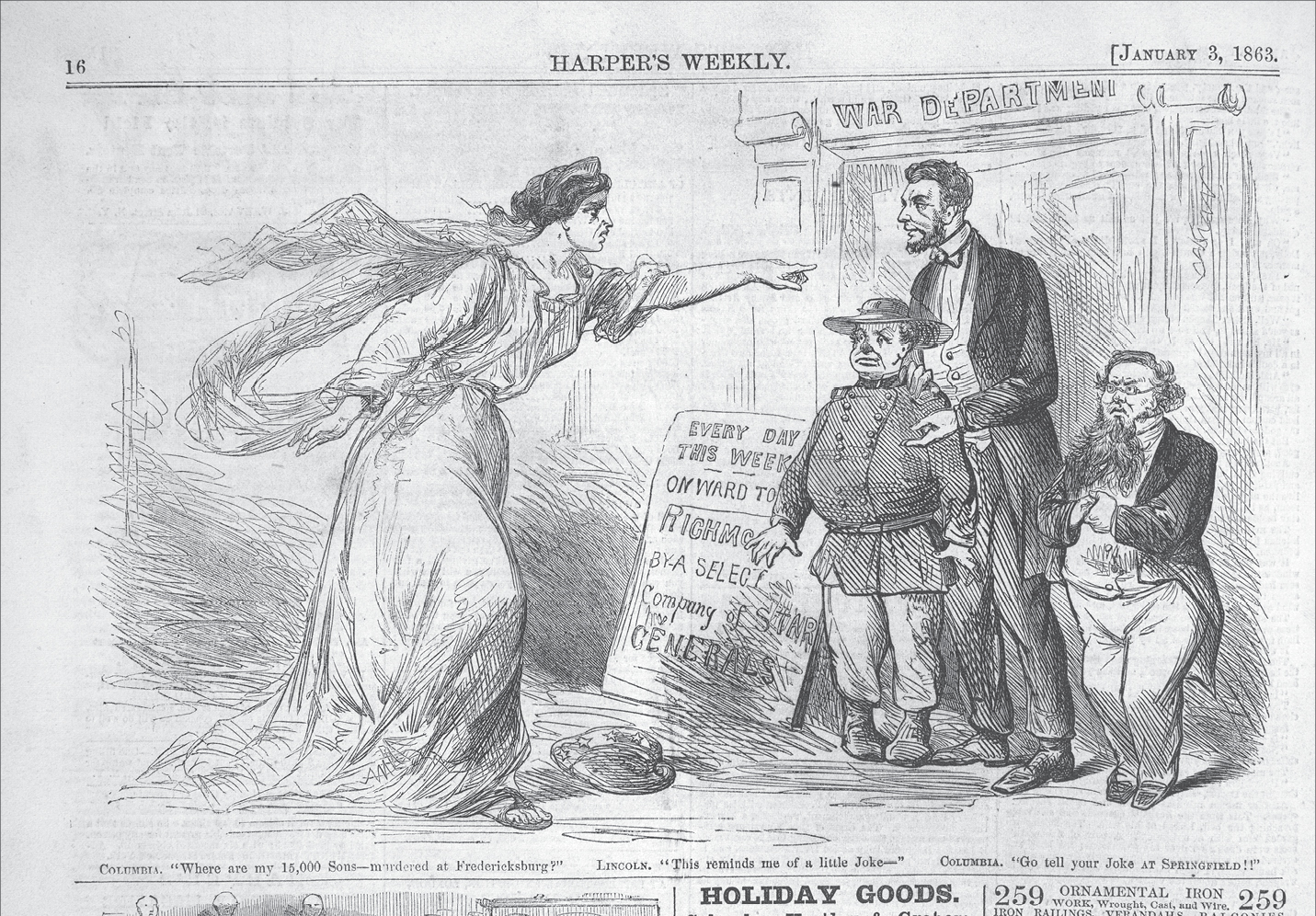

The freedom to complain publicly had long been one of the hallowed distinctions between authoritarian regimes and elected government, but this did not necessarily make it more comfortable. Lincoln was greatly distressed, for example, by a cartoon Harper’s Weekly ran after the Union debacle of December 1862, which showed “Columbia” asking the President, “Where are my 15,000 Sons—murdered at Fredericksburg?” and Lincoln replying, “This reminds me of a little joke—” He did not guffaw at the New York Herald’s February 19, 1864, editorial, which began, “President Lincoln is a joke incarnate. His election was a very sorry joke. The idea that such a man as he should be the President of such a country is a very ridiculous joke.” He found the New York World’s semifictitious account of his request for saucy songs during a trip to the Antietam battlefield so mortifying that he could not bear to look at it. The story was not entirely true, though accounts by officers present attest that the President rode through the battlefield in an ambulance, listening to aides sing childhood ditties and “grinning out of the windows like a baboon,” and that he later shared smutty stories at the mess table. Lincoln wrote a reply for the songster’s signature, maintaining that the revelry had taken place off the field and not at his request, but the piece was widely replayed by the opposition press, and the damage had been done.44

“Columbia: ‘Where are my 15,000 Sons—murdered at Fredericksburg?’ Lincoln: ‘This reminds me of a little Joke—’,” wood engraving, Harper’s Weekly, January 3, 1863

Lincoln did not relish being the brunt of jokes, but as the highest elected official in the land, he could not just counteract the satire with a clever retort or belittle the humorists who criticized him. Others could do this, however, and he was fortunate to have surrogates who could lightheartedly scoff at the scoffers. Nothing was sacred to the era’s comic writers, including the sentimental trappings of patriotism and battlefield glory. Artists made a travesty of democratic virtues by mingling them with the gore of war, and they contrasted the nation’s noblest aspirations with the haplessness of its leaders. The pundits might castigate Lincoln for escaping through laughter, but the public appreciated that the horrors surrounding them could be relieved by a little hilarity, and irreverent newspapers, books, and jokes circulated quickly.45

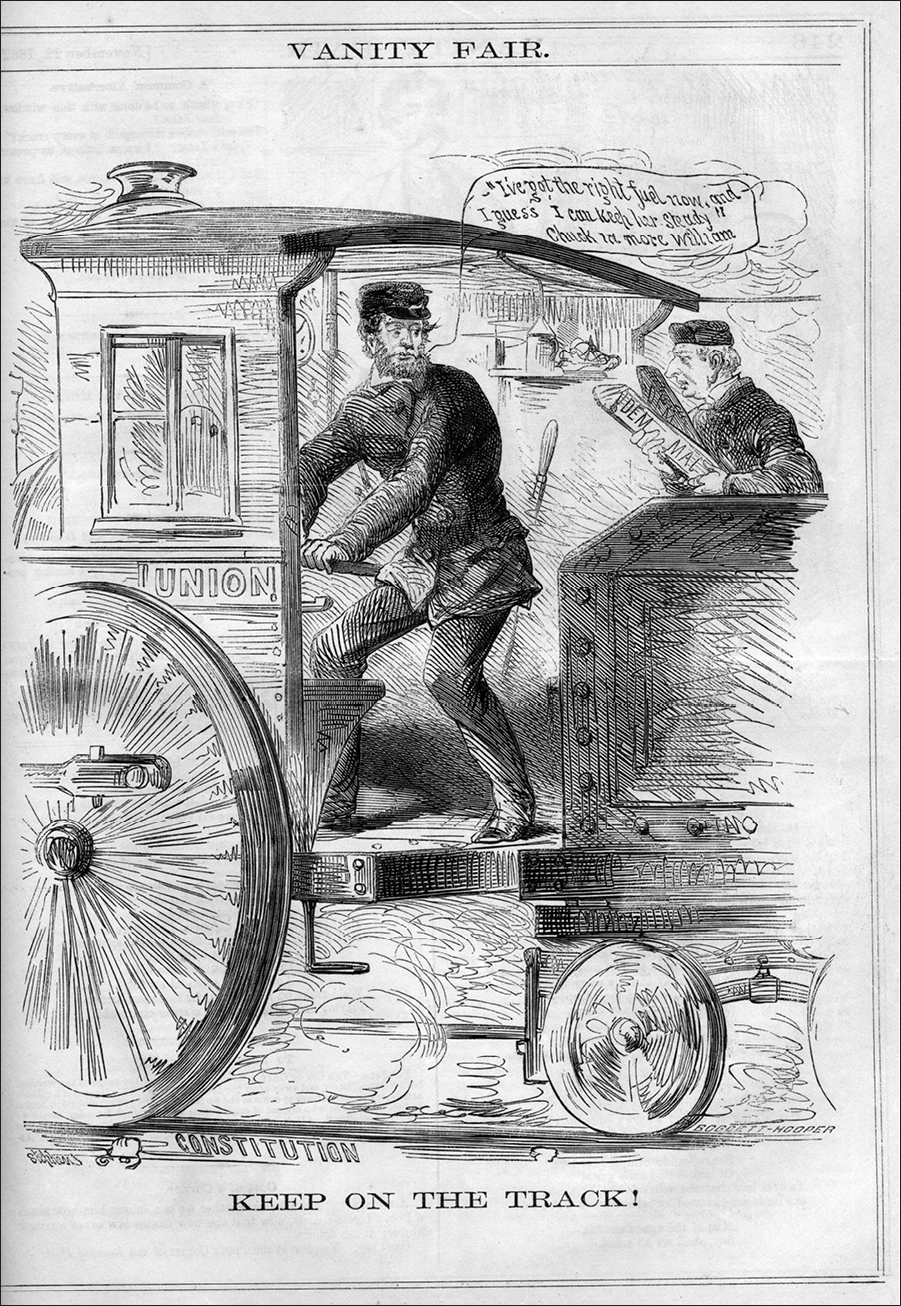

The President himself liked to read popular rags such as Pfunny Pfellow, as well as columns in local papers that ran mock editorials on military matters. “An order has been issued by the Secretary of the Navy prohibiting sailors from using, hence forth, the expression ‘shiver my timbers,’ which is no longer applicable now that wooden war ships are doomed to extinction,” ran one lampoon. Given the popularity of ironclads, the piece continued, Secretary Welles was proposing the phrase “Flummux my rivets.” Lincoln was particularly drawn to Vanity Fair, whose self-proclaimed goal was the castigation of secessionists, shady contractors, and “flagitious politicians.” “Union and the Constitution is our motto,” they boasted. “A Rod in [a] Pickle for all who Deserve it, and a word in aid of all who need and are worthy of it.” Until it closed in July 1863, Vanity Fair’s editors made free with a wide variety of leaders, taking aim at everyone from Winfield Scott to Henry Ward Beecher. They treated Confederates like irritating relations who should be ignored, while robustly criticizing excessive abolitionists, political hacks posing as generals, and anyone else who hindered the foot soldier. Lincoln underwent some ribbing as well. He was pictured as a silly man who traded on poor witticisms and impotent public statements while doing little to end the conflict. Ran one ditty:

We have found a way

At the present day

To fix the affairs of the nation.

The magic pill

For every ill

Is—issue a Proclamation!

For the most part, however, Vanity Fair cut the President a good deal of slack, and forcefully nipped at administration foes, relieving some pressure from the government. Lincoln mentioned to at least one acquaintance that the magazine’s pointed reviews were “very helpful to him.”46

Whatever their political benefit, the President liked the satirists because they gave him an excuse to chuckle away his fatigue or irritation. Lincoln was especially tickled by the writings of longtime Vanity Fair editor Charles Farrar Browne, who became indistinguishable from his fictional creation “Artemus Ward.” Browne was a professional journalist who took his role as critic seriously; he saw his writings as a correction against the excesses of the era. The “shaft of ridicule,” he noted, “has done more than the cloth-yard arrows of solid argument in defending the truth.” Yet his pseudonymous persona Artemus Ward was pure burlesque. An itinerant carnival barker, Ward traveled around the country with an exhibition consisting of “three moral bares,” a kangaroo, and a wax model of George Washington. Ward’s travels allowed him to observe, with canny accuracy, the social curiosities of the era, from unorthodox religious cults to the burgeoning women’s movement. Browne’s ear for dialect was extraordinary, whether he parodied the “flatulence” of a pompous local sheriff or the malapropisms of a clodhopper quoting Shakespeare. The writings are peppered with Ward’s particular sagacity, such as his comment on the virtues of thrift: “By attendin strickly to bizniss I’ve amarsed a handsum Pittance.” This use of wacky misspellings, bombastic speechifying, and gross exaggeration gave the writings a distinct sense of absurdity. “People laugh at me more because of my eccentric sentences than on account of the subject-matter in them,” Browne once noted. Still, Artemus Ward’s sympathy was always for the small-town citizen, and he pointed up, as did Lincoln, the shrewd pragmatism of frontier folk. In his story “The Draft in Baldinsville,” Ward roasted draft dodgers as well as prattling politicians who intoned the need to fight while remaining safely at home. “War meetin’s is very nice in their way, but they don’t keep Stonewall Jackson from comin’ over to Maryland and helpin’ himself to the fattest beef critters. What we want is more cider and less talk,” opined Ward. The writings were something more than a send-up of bucolic simpletons. They made a plea for common sense and moderation that proved an antidote to the fanaticism of the war.47

It is not surprising that Charles Farrar Browne had such an appeal for Lincoln, for they shared a number of traits. Both were awkward and ambling, noted for their ill-fitting trousers and unruly hair. Both were sometimes given to morbid introspection, cracking jokes to chase depression. Both cared passionately about language; they popularized stories and expressions that have survived for many generations, influencing the growth of a characteristic American humor. Politically they were further apart, with Browne reflecting the more conservative and pro-slavery leanings of Midwestern Democrats. At best he gave lukewarm support to the sixteenth president’s program. When Vanity Fair published Ward’s story of a fictional meeting with Lincoln and several cabinet members in April 1862, it poked fun at both the style and ineffectiveness of the war leaders, and the magazine consistently pushed for a return to older interpretations of the Constitution. Still, Browne and Lincoln shared an animosity toward draft evaders and the radicals in Congress, and the President found Ward’s send-up of provincialism to be instructive as well as amusing.48

Lincoln liked to pull a copy of Artemus Ward’s His Book out of his pocket to read passages aloud. He thought the mildly blasphemous “High Handed Outrage at Utica” particularly funny, though that episode seems to have lost its pungency over time. He regaled his cabinet with an interpretive reading of the piece on September 22, 1862, just before announcing his decision to publish the Emancipation Proclamation, a juxtaposition of gravity and mirth that greatly annoyed Edwin Stanton. Lincoln’s penchant for these comedic routines became known outside Washington, and in 1863 the New York Herald published an editorial called “Artemus Ward and the President,” which claimed the performances were meant to convulse the cabinet with laughter so that they would agree to whatever Lincoln proposed. “We scarcely know which most to admire, the simplicity, the sublimity or the success of the idea.” Most descriptions of the President’s readings, however, give the impression that he simply enjoyed sharing a good story, whether it was his or borrowed from someone else.49

The presidential office also held the writings of Robert Henry Newell, a New York journalist who used his pen to highlight the more ludicrous side of the military situation. It is interesting that Lincoln appeared to enjoy Newell’s work, for they were not closely allied politically, and Newell had little admiration for those wielding power. He opened his first commentary with the words “Though you find me in Washington now, I was born of respectable parents, and gave every indication . . . of coming to something better than this.” On virtually the same day, Newell inaugurated his character Orpheus C. Kerr—whose name was a play on “office seeker”—in a drawing sent to Lincoln’s secretary of state. Showing a harried official sorting through piles of petitions for office, it pointedly reproached administration spoilsmen. Newell was a highly educated man who shunned the use of dialect and sprinkled his columns with literary allusions, but he had a keen eye for paradox and the affectations of those wielding power. He disliked equally abolitionists, antiwar Democrats, the arrogance of the South, and the wasteful incompetence of civilian and military leaders. He once described Lincoln as bowing “like a graceful door-hinge,” and expressed bemusement at the President’s near obsessive penchant for long anecdotes. He was not personally hostile, however, and seems to have gained some respect for the chief executive over time. Nonetheless, Newell was one of the most effective and biting satirists of the administration. George Templeton Strong thought the Orpheus C. Kerr papers the “most brilliant product of the war,” likened them to champagne, and pronounced their author a “genius of the Rabelaisian type.”50

Lincoln’s interest in the adventures of Orpheus C. Kerr is all the more intriguing because Newell’s main thrust was antimilitaristic, and he dared poke fun at the nearly untouchable embarrassment of the Army of the Potomac. He took a steely-eyed view of the war, shunning popular romanticism, and the empty bravado of the battlefield. The majority of Newell’s stories involved Kerr’s service with the hapless “Mackeral Brigade” of the “Army of Accomac,” a unit known for its “remarkable retrograde advances.” Most of the brigade’s actions centered on efforts to cross a puddle-sized body of water called Duck Lake in order to capture a two-house burg named “Paris.” It was an amphibious operation, with the Navy patrolling the lake in an ironclad, rigged up from a converted stove, whose front grate came unhinged in violent action. Experiments with pontoon bridges and novel weapons constantly backfired. Across Duck Lake, the rebels constructed massive batteries and rival ironclads in plain sight of the Union men, and occasionally the two sides went fishing together. For those familiar with the disappointing progress in the Eastern Theater during 1862 and 1863, the stories are a wonderful take on the imbecilities of the campaign, and only a hilarious hairline from the truth. Perhaps this is also what caught Lincoln’s eye. He was wildly frustrated by the operations of the Army of the Potomac, with its seemingly irrelevant movements and inexplicable failures. Perhaps a mordant presidential cackle over the Mackeral Brigade forestalled an explosion of another kind. Pinning the failure on military ineptitude may also have soothingly removed any discomfort about Lincoln’s own responsibility for the debacles in Virginia and Charleston harbor, which Kerr only thinly disguised.51

Orpheus C. Kerr offered a laugh at the Army’s expense and Artemus Ward set up the arrogance of petty officials and small-time hucksters. But arguably no one filled Lincoln with more glee than David Ross Locke’s fabulous character Petroleum Vesuvius Nasby.

Vesuvius Nasby erupted onto the scene in April 1862, in one of Locke’s regular columns for an Ohio newspaper. A preposterous bucolic preacher, who lived at “Confederit X. Roads,” he liked to remain lubricated with the whiskey he called “koncentratid kontentment” and was opposed to “methodis, Presyterin, Luthrin, Brethrin, and other hetrodox churches.” Like Charles Farrar Browne, Locke used cacography and tortured common sense in his caricature, in this case a spoof of the Copperheads—as those who opposed the war were popularly known. Nasby parroted their racial prejudice and blustered over the evils of conscription, which the antiwar party used as a rallying point against Lincoln. The commentary was scathing, whether it roasted outspoken critic Clement Vallandigham (“The trooth is, Vallandigum . . . hez tongue, without discreshun. . . .”), Democratic journals (“The Noo York Illustratid Flapdoodle”), or the lame excuses of draft dodgers (“I am bald-headid, and hev bein obliged to wear a wig these 22 years”). Nasby’s sermons were delivered in a pseudo-trenchant style that purported to show a principled abhorrence of fratricidal war, but Locke’s stinging wit exposed these attitudes as nothing more than ignorance and bigotry.52

Like other humorists, Locke had a day job as an editor. He wrote serious political commentary against the mismanagement of the Union effort, as well as the “masked secessionists who go about grinning at every reverse.” But nothing matched the reach or genius of Petroleum V. Nasby’s uncouth voice. Locke was aware that his satire influenced the public more profoundly than his straightforward reporting. Objectivity was not his goal, nor was pure humor. Having personally experienced the disruption of his neighborhood by antiwar politics, as well as religious divisions that were altogether too similar to Nasby’s “Church uv the Noo Dispensashun,” he determined to speak out strongly. “I have simply exaggerated error in politics, love, and religion,” he told a friend, “until the people saw those errors and rose up against them.”53

Lincoln greatly admired Locke’s inventive turns of phrase, and reportedly once told him that “for the genius to write these things I would gladly give up my office.” It was said that the President read the Nasby Papers more than he did the Bible, and his worn copy, now in the Library of Congress, attests to his faithful perusal. Lincoln pulled Nasby from his pocket as often as he did Artemus Ward’s His Book, sometimes interrupting serious strategy sessions to regale his cabinet with the latest exploits from Confederit X. Roads. Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner was surprised to find Lincoln in March 1865 so engaged with Locke’s writings that he set aside other business to “initiate” Sumner into their hilarity. The senator thought it a “delight to see him surrender so completely to the fascination,” but was concerned that Lincoln kept a group of legislators waiting more than twenty minutes while he recited Nasby’s pseudo-wisdom.54

Lincoln’s partiality for Nasby reflected something more than frivolity. The nation’s leader recognized that Locke had handed him a salve against the bruises of rough and ready democracy—indeed, a cunning restraint against an unschooled public’s right to jeer at authority. Locke played havoc with the pretensions of armchair critics and shrewdly undermined the credibility of the naysayers. Hypocritical preachers, pompous journalists, and self-righteous politicians were felled with the nib of his pen. Petroleum V.’s naïve assessments, his blunt, Swiftian japery, and his unerring eye for paradox became an unofficial machine for administration efforts to suppress the opposition. Although Edwin Stanton evidently dubbed Locke’s humor “the God damned trash of a silly mountebank,” in the end it may have been more effective at stifling criticism than the sterner measures devised by Lincoln’s administration. Locke’s writings were a “constant and welcome ally,” Sumner admitted. “Unquestionably they were among the influences and agencies by which disloyalty in all its forms was exposed, and public opinion assured on the right side.”55

III