3

TWO EMANCIPATORS MEET

On the day he met Abraham Lincoln, Sergeant Lucien P. Waters was fed up.1 He was fed up with the suffocating summer heat, which to his Northern sensibilities felt close to 120 degrees. He was fed up with the Union’s frustrated advances in Virginia, which left his men demoralized and his horses exhausted. Most of all he was fed up with the fact that more than a year into the conflict the country’s noblest goals were far from being met. The South was still in rebellion, the slaves were still in bondage, and thousands of patriotic young men were mired in a war that seemed to be waged for little more than naked belligerence. “War for the sake of war is hellish,” Waters confided to his family, voicing his fear that a nation dedicated to true liberty was fast fading from view. In August 1862 Sergeant Waters decided he would run these thoughts by the President—and when he did so he left us a remarkable sketch of a leader under pressure.2

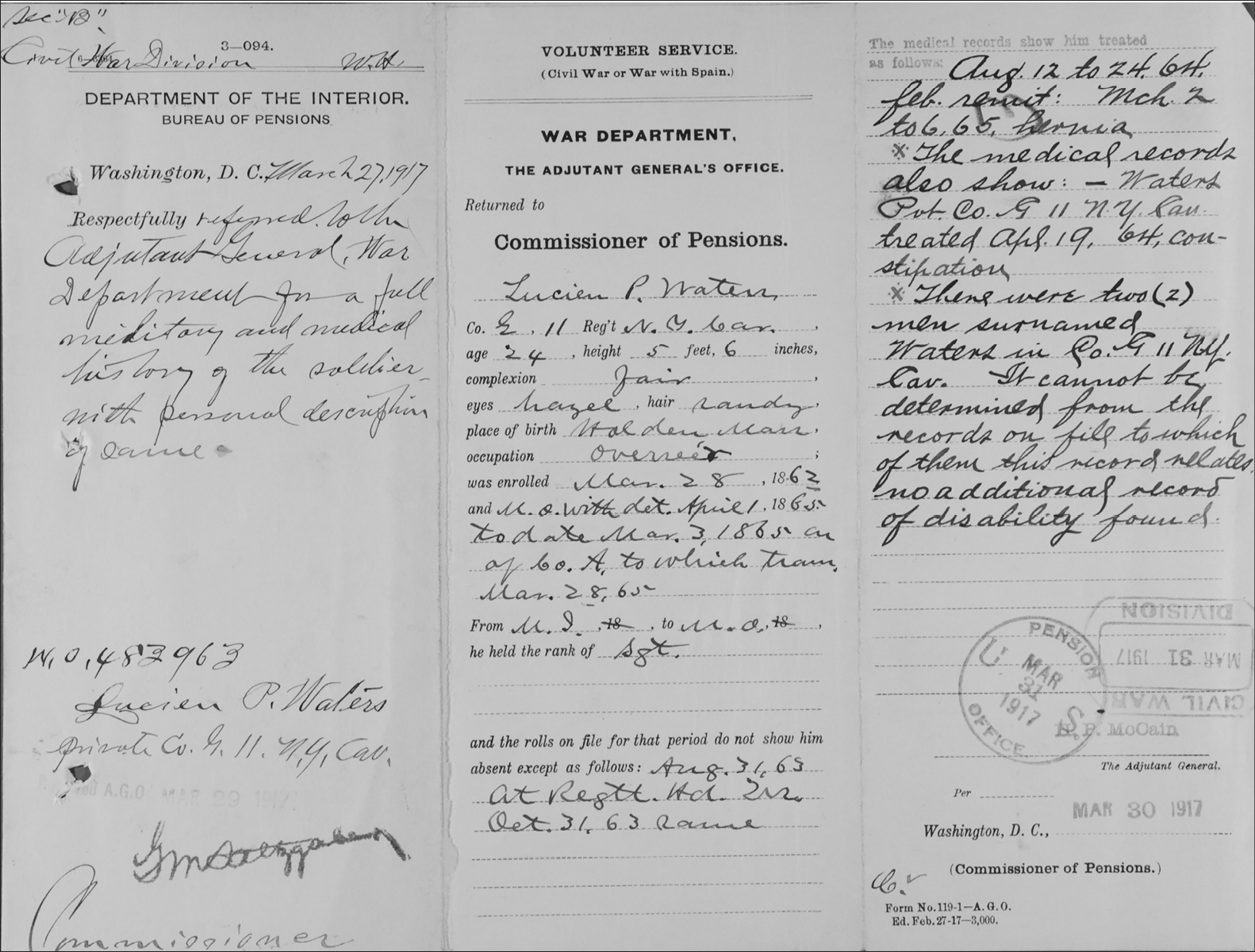

Lucien Parkhurst Waters was twenty-four years old when he joined a New York cavalry regiment in the spring of 1862. The youngest son in a Presbyterian preacher’s large family, he was working in Yonkers as a supervisory mechanic when the war broke out. Service records describe Waters as five feet six inches tall, of fair complexion, with hazel eyes and sandy hair, though a wartime carte de visite shows him sporting dark curls. Waters described himself as possessing “a loving & earnest heart . . . an ordinary education, & a practical knowledge of several trades & departments of business, having of late had charge of quite a number of men.”3 He was also an unhesitating Republican who used stationery with a beardless “Honest Abe” adorning the letterhead. Fiercely opposed to slavery, Waters originally hoped to serve his country by going to the Sea Islands of South Carolina to teach African Americans who were under the protection of the occupying Union Army.4

Instead, a charismatic colonel named James B. Swain persuaded Waters to join the regiment he was just forming. Swain was working at the behest of Assistant Secretary of War Thomas A. Scott, and the 890 men he enlisted came to be known as “Scott’s 900.” Initially they were attached directly to the First U.S. Cavalry, but were later redesignated the Eleventh New York Volunteer Cavalry. In early 1862 Swain was on the lookout for sharp men because he understood that they would be assigned as special forces. Scott wanted this regiment to scout, to surprise and intercept civilians aiding the rebels, and to disrupt irregular behavior by Union troops. As part of Washington’s defense system, they were to act generally as the eyes and ears of the government. “Were the secret history of the regiment written,” Swain later recalled, “even those most intimate with its Colonel would be astonished at the extent and character of the secret service he was detailed to perform.”5

Lucien Waters was attracted by the promise of adventure and by the opportunity to strike a personal blow against slavery. Accordingly, on March 28, 1862, he was mustered in for three years, with the rank of private. A month later he was promoted to sergeant of Company G, a position that entitled him to bed and board and seventeen dollars per month. Dressed in new blue uniforms, with yellow blouses, Scott’s 900 appeared a dashing outfit when it left in early May on what Waters called their “patriotic pilgrimage to the Land of Freedom.”6 They were assigned to a comparatively luxurious post in Washington on Meridian Hill named after their colonel’s wife, whose maiden name was Relief. Lucien’s letters from Camp Relief contain the typical soldier’s complaints about food and the confinement of camp life. He hated “those damp stinking barracks,” he told his folks, and acquired an interest in vegetarianism after encountering some sutlers who were apparently selling pies made of rat meat. He also found that having direct responsibility for “the whole company or portions of it, as the case may be,” was not light work. The long days were crowded with supervising drills, looking after the soldiers’ health, maintaining proper conditions in the stables, and ensuring day to day—sometimes minute by minute—discipline. “My duties crowd so Thick upon me,” Waters told his parents, adding that he spent more time breaking up fights than patrolling.7

One thing Waters did not grouse about was the quality of the horses. The regiment had unusually fine steeds, with Company G riding spirited iron grays. There was a reason for this privilege: not only was Scott’s 900 charged with maintaining peace along the Potomac, it was made part of the escort for President Lincoln. A group of five or six men sometimes guarded the White House carriageway, or rode at the President’s side as he made calls around town, but their particular duty was to accompany him when he traveled to and from his summer home, three miles from the White House. Rumors of assassination had followed Lincoln from the time he was elected and the danger only increased as rebel actions grew bolder during the warm days of 1862. Lincoln’s friends thought the dark, wooded road up to the cottage was a likely path to misadventure and had persuaded the Army to provide some protection. The long-stirruped president, surrounded by his little knot of soldiers—sabers drawn and accoutrements clanking—became a familiar Washington sight in the morning and late evening. Walt Whitman recorded that he frequently saw them pass and thought them more somber than ceremonious. Others who noticed the slow-trotting procession that summer were amused by its unassuming appearance: “I have seldom witnessed a more ludicrous sight than our worthy Chief Magistrate presented on horseback,” wrote one New York soldier. “It did seem as though every moment the Presidential limbs would become entangled with those of the horse he rode. . . . That arm with which he drew the rein, in its angles and position, resembled the hind leg of a grasshopper.”8

Since the day Lincoln had arrived unannounced at the capital, ridiculously dressed in mock disguise, he had been embarrassed by rumors that he was fearful in public. Now he chafed under his guard and sometimes sneaked away early to avoid its company. He lobbied steadily for the unit’s disbandment, grumbling about it to anyone who would listen. “I do not believe that the President was ever more annoyed by anything than by the espionage that was necessarily maintained almost constantly over his movements,” recalled a member of the regiment. “Nearly every day we were made aware of his feelings upon the matter.” Lincoln reportedly told one acquaintance that the guard made so much clatter he could not carry on a conversation with his wife and that he “was more afraid of being shot by the accidental discharge of one of their carbines or revolvers, than of any attempt upon his life.” But what he really hated about the escort was the conspicuousness of it, the inconvenience, and the intrusion on his privacy.9

Lincoln may have resented the presence of his bodyguards, but for the most part he was genial and companionable with the cavalrymen. The unit was entertained by what they termed his “oddities” and impressed by his unpretentious and polite conversation. Lucien Waters reported that the President bowed solemnly and awkwardly to the troops as he rode by, and others recalled that occasionally he would come into camp and chat with the men, sometimes even sharing their simple supper. They in turn took advantage of their unusual access. The escort’s bivouac was so close to the first family’s cottage that their boisterous talk could be heard from the veranda. Lincoln would rise and ask them to lower the racket and when he did so they would pepper him with complaints of poor equipment and inedible rations. He apparently took their words seriously. One guard thought the commander in chief went so far as to address every one of their grievances, and told how he had once ripped apart a pair of shoddy socks with his powerful hands and stuffed them into his pocket to use in a protest to the War Department. “The great man, bending beneath the weight of the Republic and its gigantic war, found time amid all his cares to be just to the common soldier,” he wrote in amazement.10

In addition to protecting the President, Scott’s 900 was ordered to keep an eye on the activities of Southern sympathizers who lived near Washington. Those who sided with the Confederacy were spiriting supplies into Virginia, secretly establishing rebel militia units, and passing information to Jefferson Davis’s army. Company G drew duty in both Maryland and northern Virginia, where it broke up local recruiting rings, patrolled polling places, and intercepted smuggled goods. Waters confided to his parents that the work was “attended with a great deal of hazard” and demanded a clear head, since the unit was frequently accosted by hostile civilians as well as rogue “secesh” raiding parties. He likened the citizenry of southern Maryland to “starving wolves” who grew bolder as they edged toward desperation. At night the patrols faced particular danger. The contact was frequently violent, especially because Scott’s 900 preferred to fight with sabers, implying close hand-to-hand combat. After one fierce skirmish, Waters wrote of a sickening field hospital, located by a stream that had become “so coloured & mixed with the blood from the wounds & amputations” that the horses refused to drink from it. A comrade admitted that because of the use of sabers, some of the men had become “horribly disfigured.”11

Like many army units in slaveholding territory, Scott’s 900 attracted African Americans who hoped to find a safe haven within the Union lines. From the early days of the war, an unofficial policy of sheltering these runaways arose. Dubbed “contraband of war” by General Benjamin Butler, who accepted some of the earliest refugees into his camp at Fort Monroe, Virginia, the fugitives were employed as laborers or simply followed the Army for protection. Initially, the practice had been largely ad hoc, with each commander forming his own procedures, and some taking pains to return the refugees to their owners. With the Confiscation Act of August 1861, however, Congress officially sanctioned the forfeiture of any property—including slaves—being used for Confederate military purposes. By the time Waters entered the ranks, the guidelines had been strengthened. On March 13, 1862, Lincoln signed a bill that created a uniform policy for dealing with runaways and prohibited military officers from returning them to bondage.12

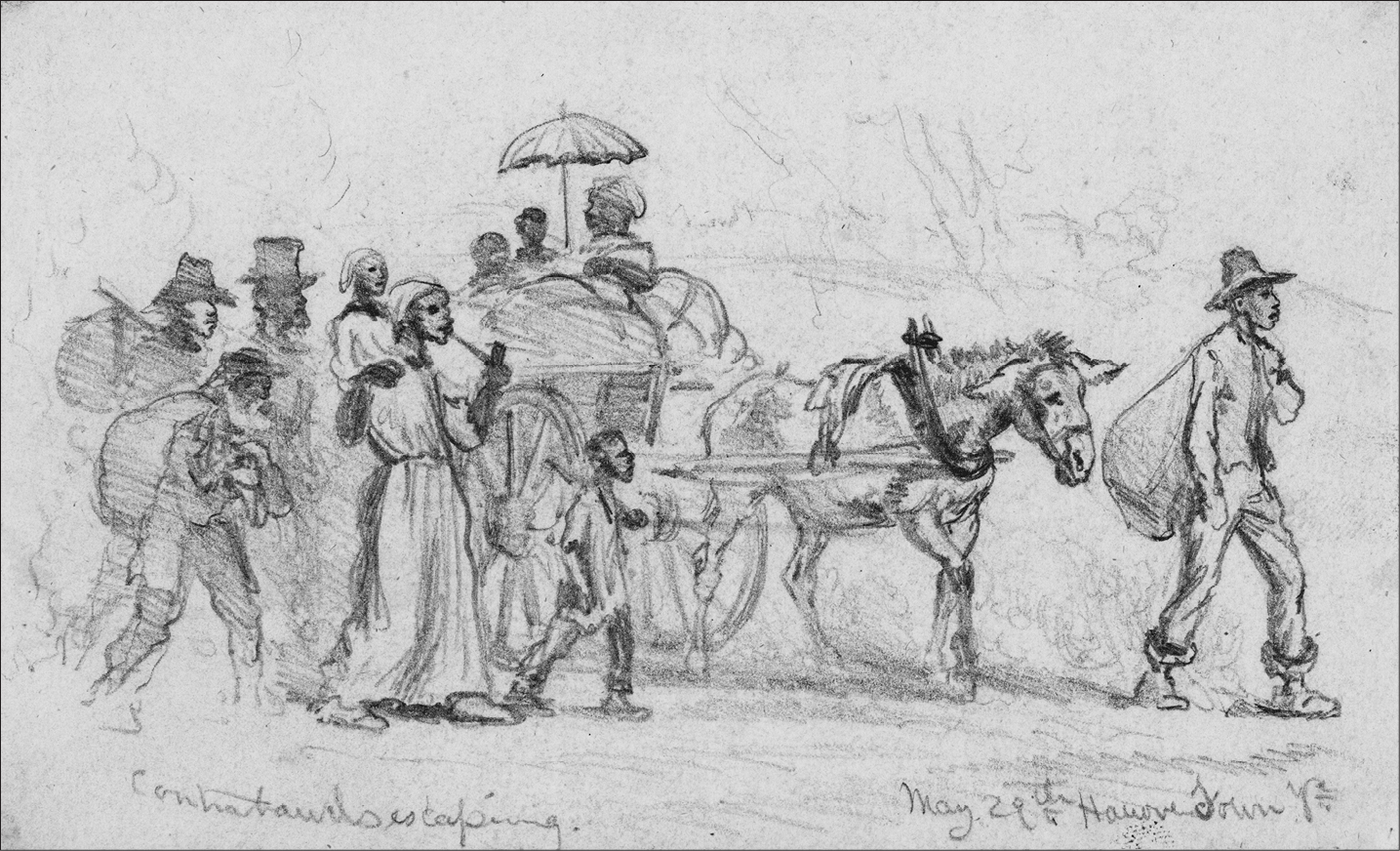

Contrabands Escaping, pencil, by Edwin Forbes, May 29, 1864

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Colonel Swain clearly approved of the orders and “liberated” more than a dozen slaves only a few weeks after his outfit went on duty, setting them to work as military servants. Some men in his regiment took the policy a step further, by taunting neighboring slaveholders about inhumane treatment, threatening the owners with “confiscation” if they did not cooperate, and sometimes encouraging the blacks to run away. Lucien described the scene when one slave, fleeing from “the rankest sort of secessionist,” escaped into their camp and was hunted down by the master. After hiding the runaway in a weedy lot, he wrote, “we gave [the planter] ‘particular rate’ in regard to his slave & in regard to his enlightenment &c. . . . The boys swore by all they held sacred that he should never take the darkey out of camp. He quailed & said he was a loyal citizen. It was too late to play that game.”13

As can be imagined, not every slave fared as well as this man. Once in Yankee camps, the contraband had a variety of experiences. Colonel Willis A. Gorman of the First Minnesota protected every black person who came within his jurisdiction, declaring he would not “be at all displeased to see the whole slave population run away.” Some, like General Joseph K. Mansfield, went further, instituting extraordinary measures to encourage those who ran from the “tirents and wicked men” of the South.14 Many Northern soldiers, however, used their charges in a manner that differed little from the bondage the slaves were fleeing, working them harshly for meager food and clothing, or treating them as court jesters who would sing, dance, or have head-butting contests for the amusement of the troops. Both Waters and one of his comrades from Company F noted that this was the case in their camp, where the men would “throw the darkies up in blankets” for fun or steal from the refugees. Although Colonel Swain was sympathetic to the slaves, it infuriated Waters that in the colonel’s absence Company G’s captain made a point of contacting masters to retrieve the runaways who came within their lines.15

Swain and other liberal officers thought they were doing the commander in chief’s bidding by depriving slaveholders of property that could aid the Confederacy and encouraging the slaves to self-liberate. Actually, at this point, Lincoln’s policy was to refrain from intimidating slave owners or encouraging runaways. Indeed, Lincoln thought the constitutional soundness of the Confiscation Act dubious. The eradication of slavery had not been his prime war goal, and although his attitude toward manumission was evolving in important ways during this period, his convictions lagged far behind those of committed abolitionists. Deeply concerned about alienating the loyal slave states of Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri, he had only reluctantly allowed the Confiscation Act to become law. In addition, slavery had just recently been outlawed in the District of Columbia, increasing tensions in the crucial area surrounding the nation’s capital. The need to keep the border states in the Union and the pro-South Democrats at least superficially calm was thus pitted against Lincoln’s impatience to end the war. By the summer of 1862 the chief executive had finally come to the conclusion that robbing the rebels of a key part of their labor force (not to mention the psychological blow of a mass defection of their “faithful” servants) could hasten the end of the conflict. However, for both political and practical reasons he drew the line at enticing slaves to escape. On July 1, he told Illinois senator Orville Hickman Browning that although he had agreed to protect runaways and employ them in the Union cause, “no inducements are to be held out to them to come into our lines for they come now faster than we can provide for them and are becoming an embarrassment to the government.”16

Unaware of these views, Lucien Waters seized the moment to work toward his ideal of “an honorable peace or none at all.” His view of slavery’s menace was far less equivocal than the President’s. In his mind there was only one reason for the war: the righting of a grave humanitarian wrong. If Lincoln favored calculated pragmatism to address America’s contradiction between freedom and bondage, Lucien oozed passion. He had abhorred slavery from afar; when he encountered its reality he was disgusted. He witnessed beatings, figures misshapen from overwork, and nearly white children, unacknowledged by their planter fathers, who were kept in servitude. Riding through several plantations near Port Tobacco, Maryland, Waters told his parents he believed God frowned on the nation while it indulged in the “damnable stinky curse of protecting the institution of Slavery!” and that his own resolve to fight for a true land of liberty was doubled. “The issues are becoming sharper,” he exclaimed, “& it behoves the people of the North to awake from their supiness [sic] to save, what I hope in the future we may call ‘great freedom’s land,’ but which at present does not answer to that name.”17

Frustrated by what he believed was near sinful inaction in the face of a national moral crisis, Sergeant Waters decided to move on the issue personally. For many of his compatriots, emancipation was a secondary war goal, but from the beginning of the conflict Waters had known that he was fighting for freedom. He fervently believed in liberation for the individual bondman, but also in liberation of the country from the political straitjacket of slavery. Unable to see swift movement in his government’s policies, Waters became a kind of self-appointed emancipator, seeking out slaves he could help. He told his parents that he wished he could “divide myself into four able bodied soldiers to do battle for the cause” and thought that in his zeal he might at least do the work of two men. Invoking the words of abolitionist preacher Henry Ward Beecher, he proclaimed that if the Lincoln administration would not move on the issue, he at least had the use of his “wits & legs.” Shocked that “incompetency & tretchery” characterized many government officials, Lucien vowed that he would “labor & suffer alone with The Thought That my motive was right.” Within weeks, he could tell his brother James that his name had spread like wildfire from plantation to plantation as a harbinger of freedom for the slaves.18

Using secret paths and hideaways known to the bondmen, Waters encouraged many to run away, smuggling some to Washington aboard U.S. gunboats that plied the Potomac River. He wrote false passes, told tall stories to slaveholders, and collaborated with like-minded sailors to conceal his freedom seekers. In one instance Waters helped a runaway fashion a halter from a grape vine when the owner, fearful that his property would flee, denied him the use of leather equipment. Another time he went six miles on foot to tell some fugitives about the presence of a boat nearby, secreting them in the marshes as they waited to be taken aboard. The sergeant also tried to protect the contraband in camp against the robberies and humiliations some of his men inflicted on them. Perhaps most remarkably, he was a rare example of a white man who defended the African Americans’ innate ability and noted their strong human ties to family and friends. At a time when Lincoln was still questioning whether blacks could live effectively among whites, Waters scribbled this notation on the back of a letter written him by a grateful escapee: “This letter should show that ‘niggers’ are not so stupid as is so commonly claimed. It also shows by its many requests to friends left behind them in bondage that one’s work is not ended with simply getting the parties into freedom—for they have those they love as their lives which they leave behind them.”19

Among the black people, Waters became known as the “bobolition Sergeant,” but among whites he gained a reputation for being a “damned abolitionist.” He admitted that the local planters would as soon shoot him as a dog and intended to do so if they caught him. His midnight rescue operations were conducted behind the backs of both his captain and the captain of transport. Waters did not mince words in their company, however, and stoutly told his parents that he would “fawn on no man, neither do I play the sycophant to any superior officer & for the sake of his good will & pleasure sacrifice my manhood by hiding my true sentiments. . . . NO! By all that is true & holy, my manhood is not for sale.” Believing that in this war there was only one “great object each man should have in view,” he continued to risk the ire of plantation lords and his authorities, conducting his freelance manumissions to the very end of the struggle. By the summer of 1862 Waters was luring dozens at a time away from their masters. “My hand is in at stealing darkies,” he confessed. “I have traveled on foot & on horse & have brought & protected them to Camp secretly. . . . My name is without a mistake, a terror to the planters, & a talisman of good to the slave. The first they enquire for is Sgt. Waters & he never proves untrue to them.”20

Lucien Waters had taken morality and the law into his own hands.

Waters mistakenly thought he was pursuing his Moses-like mission with the blessing—indeed, under the orders—of the commander he called “Uncle Abe.”21 So it was not for approbation that he sought an interview with the President. Rather, his plan was to get Lincoln’s approval for a furlough. Waters called it a discharge, though it was meant to be temporary—the idea was that he would go on a recruiting expedition in New York, sign up twenty men for his regiment, and gain a lieutenancy by doing so. The matter was small, and the moment unpropitious, but Lucien was an impatient young man and despite the doubts of his colonel, he wanted to press forward. By the time sergeant and commander in chief met, both men had been under weeks of pressure; they were as flammable as dry tinder. The meeting that Waters recorded was, therefore, a startling one.22

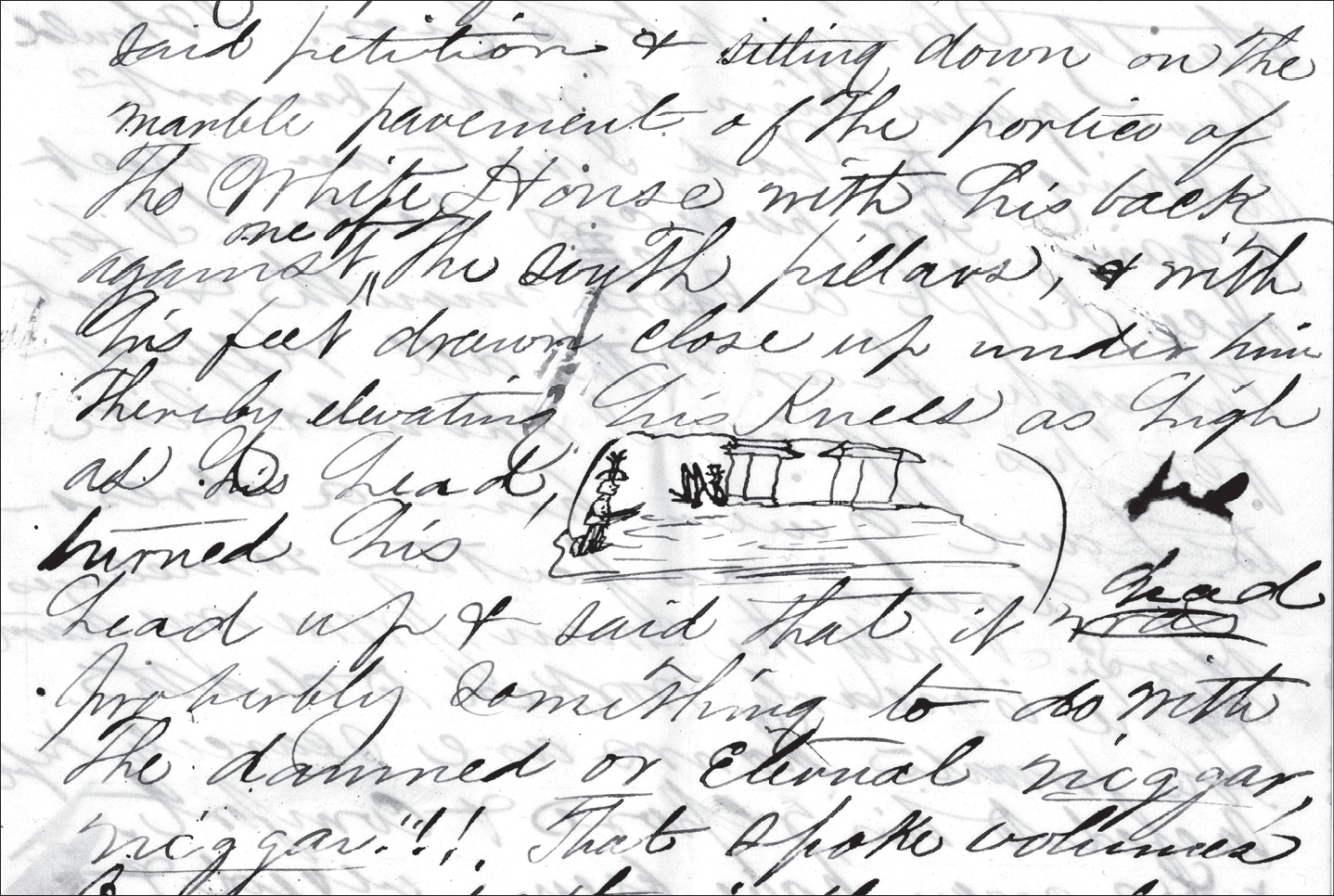

Waters appears to have waylaid the President sometime during the second week of August 1862, for he described the encounter to his brother on August 12, but made no mention of it in letters of July 31 or August 5. He intercepted Lincoln on the portico of the White House and handed over his request for a temporary discharge. Lincoln, who virtually never turned a petitioner away—and certainly not a blue-clad soldier—took the paper and unceremoniously plopped down on the floor of the portico, leaning back against a column, his knees drawn up “as high as his head.”23 It was his characteristic pose, awkward but engagingly unself-conscious—the essence of a man without pretense. There are many accounts of the lanky Midwesterner lounging in this way, or balanced uncomfortably on the chairs that never seemed to fit him. Friends, family, and strangers commented on the way Lincoln’s legs would swing across chair arms or how he would tell stories in his office, “reaching out with his long arms to draw his knees up almost to his face.” Others remarked on how his feet and legs wandered all over the floor in front of him, until guests “had serious apprehensions that they would go through the wall into the next room.”24

Waters was amused enough that he drew a sketch of the President for his brother. It is just a little scribbled cartoon, but it wonderfully captures the informality of the scene. There sits Abraham Lincoln, with a familiarity almost unimaginable today, legs folded and tall hat in place, looking for all the world like a cricket perched on the nation’s front porch. And Waters put himself in the drawing too, replete with dress hat and saber, striking a daring pose. It might have been a whimsical moment, but then Lincoln rather spoiled the magic. Before he bothered to read the sergeant’s request, he turned up his head and remarked moodily that the paper had “probably something to do with ‘The damned or Eternal niggar, niggar.’”25

“That spoke volumes to me,” Waters glumly remarked, and in retelling the story he placed two exclamation marks after Lincoln’s words. He viewed it as proof that the chief executive was under the “insiduous & snaky influences” of Washington’s many Southern sympathizers, the same influences that had kept slavery alive for decades. Lincoln had no idea, of course, of Waters’s political leanings—was unaware of his freelance emancipations—and that makes his outburst the more intriguing. (Had the President known of Waters’s activities, there might have been additional expletives flying across the portico. One of the most powerful recollections ever written of an enraged Lincoln came from a military officer who had lured Maryland slaves to join the Union Army. The chastised officer “did not care to recall the words of Mr. Lincoln.”) As it was, Lucien was offended enough and admitted to his brother that he would have liked to give the President “a ‘right smart’ talking to.” But mindful that he had approached Lincoln to ask a favor, he kept his opinions to himself.26

Lucien P. Waters’s sketch of Lincoln on the porch of the White House, August 12, 1862

NEW-YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Contemporary readers will likely share Waters’s surprise and disappointment. Did Lincoln, known for his eloquence and his marks of respect to African Americans, speak this way? Why did he assume the issue was about slavery before he had even read the cavalryman’s petition? Did the soldier perhaps make up or embellish the story to impress his brother?

The evidence suggests that the encounter took place just as Waters described it. Waters is a highly credible source—a staunch Republican who had not only voted for Lincoln but sympathetically observed him firsthand. All of his letters show that he prized candor, almost to the point of recklessness, and that he was willing to stand courageously behind his beliefs and his words. We also know that a certain coarseness was a feature of Lincoln’s character and that he could be brusque and sarcastic, especially when he was displeased or under pressure. One friend recalled that generally Lincoln had a very good nature, though “at times, when he was roused, a very high temper. . . . [I]t would break out sometimes—and at those times it didn’t take much to make him whip a man.” In addition, accounts of Lincoln’s outbursts during times of stress show that he used the word “nigger” in connection with serious political issues, not just in colorful stories. For example, Edward Lillie Pierce, a dedicated educator of ex-slaves, told of an 1862 interview at which the President “did not behave well. He talked about ‘The itching to get niggers into our lines.’ His son was very ill and quite likely that had something to do with his temper at the time. I never met him again, and as I remember did not care to.”27

And by August 1862, Lincoln himself admitted he was so overwhelmed that he was more or less living day to day. The Peninsula campaign of George McClellan had ended in disaster during the appalling Seven Days’ battles; in the West progress was stalled; the public mood was explosive. White House aides noted that their boss had grown “sensitive and even irritable,” especially on the subject of slavery’s future. That summer the President snapped at a Union officer who came to ask him for permission to bring his wife’s body from the South, and when he later apologized, Lincoln acknowledged that he was “utterly tired out” and had become “savage as a wildcat.” Horace Maynard, a Southern congressman who had remained in Washington, advised Senator Andrew Johnson, his fellow Tennesseean and Unionist, that Lincoln had expressed “himself gratified in the highest degree that you do not . . . raise any ‘nigger’ issues to bother him.” Another conversation, nearly identical to the one with Waters, took place around the same time, when Connecticut governor William A. Buckingham made a call to present a petition from antislavery activists in his state. Before Buckingham could speak, Lincoln said “abruptly, and as if irritated by the subject: ‘Governor, I suppose what your people want is more nigger.’” Lincoln evidently changed to a more conciliatory tone when he saw that Buckingham was startled, but his initial reaction had its impact.28

The source of Lincoln’s discomfort was his own confliction over the seemingly irresolvable problem of emancipation. He was as troubled by the bondmen’s plight as Lucien Waters, but was disinclined to approve the kind of precipitous acts his young sergeant favored. Lincoln had long felt a moral repugnance at slavery, but he had a competing attachment for the Constitution, which set the United States apart from all other nations in the great experiment of democracy. That document specified that the federal government should not interfere with the prerogatives of the states—and slavery was one of those prerogatives. Lincoln’s formula for the elimination of the offensive institution was to persuade the states to relinquish it themselves, gradually, and with compensation. He hesitated to move too quickly lest he outpace public opinion or alienate the border states, whose fragile support was essential. “I hope I have God on my side, but I must have Kentucky,” he is famously reported to have quipped. Provocative exploits like those of Sergeant Waters were exactly what he feared might push Unionist slaveholders toward secession.29

Lincoln wanted to move on the slavery issue, but he wanted to move cautiously and deliberately. No perfectionist, he preferred to embrace the art of the possible in his politics. He did not like risky actions, and he likened the destruction of slavery to the removal of an irritating wen (or cyst) on a man’s back. Although the sufferer may have wished the growth had never occurred, Lincoln observed, it was another thing to have the surgeon remove it in a dangerous operation. He also understood the value of careful timing. Leonard Swett, one of his most trusted political confidants, remarked that Lincoln was not one to hurry an issue; rather, he preferred to get himself into the right place to act, and wait for an opportune moment.30 The President himself described his anxiety over abolition as if he were a farmer waiting for pears to mature in a frustratingly slow season. “Let him attempt to force the process, and he may spoil both fruit and tree,” he noted. “But let him patiently wait, and the ripe pear at length falls into his lap!”31

Many of those benefiting from historical hindsight have viewed Lincoln’s desire to move gingerly on the issue of slavery as wise—if frustrating to those anxious for a quick end to the institution. He had a keen appreciation of the difficulty most people have in accepting great change, and he knew that no matter how prudent the course, emancipation, either as a moral policy or as a military tool, was a revolutionary act. Like all experimental weapons it had the advantage of novelty—but also the liability of being untried and therefore the potential to backfire. After all, what he was searching for was a lasting resolution to the nation’s troubles, not an additional source of division. As one longtime political observer noted, as radical as he might be as to ends, he was ever conservative as to means.32

Here then was Lincoln’s dilemma in that stifling summer of 1862: how to satisfy the diverse components of the Union on a subject so volatile it had brought on war itself.

Lincoln’s cautionary notes were like a plaintive oboe among the tubas. Dedicated citizens like Lucien Waters, who were exasperated that the President did not act swiftly to right a monstrous wrong, were quick to express their chagrin. Abolitionist Wendell Phillips thought the Illinoisan a “huckster” whose antislavery principles did not go much beyond those of most Southerners. Senator Charles Sumner badgered him every few weeks, promoting the idea that emancipation was necessary to win the war. Horace Greeley, the feisty editor of the New York Tribune, loudly proclaimed similar views as did “preachers, politicians, newspaper writers and cranks who virtually dogged his footsteps, demanding that he should ‘free the slaves.’”33 Union generals got ahead of him, trying to jump-start liberation in their military districts, and had to be reined in. African American voices were also heard within the din. On August 1, 1862, a group of freedmen gathered in front of the White House for a prayer meeting. “One old chap with voice like a gong prayed with hands uplifted,” recalled a witness. “‘O Lord command the sun & moon to stand still while your Joshua Abraham Lincoln fights the battle of freedom.’”34

At the same time, the White House was attuned to nervous rumblings from those who wanted slavery left out of the conflict, either to avoid societal upheaval or for constitutional reasons. Some were slaveholding Union men who warned the President not to “make slaves freemen, but to prevent free men from being made slaves.” Lincoln’s own best friend, Joshua Speed, was among them. His advice was to stay clear of state laws—such as those in his native Kentucky—that actually forbade manumission. And not all the critics came from Dixie. There was a robust set of Yankees who made considerable money either directly or indirectly from slavery, or who otherwise sympathized with the South. As Lincoln pondered the question of liberation and the dislocations it might cause, Washington’s Daily National Intelligencer served up a daily dish of news about riots perpetrated against free black laborers in Ohio, St. Louis, and Brooklyn—reports that can only have reinforced the chief executive’s concerns about a post-emancipation society.35

Then there was the Congress. For six months it had been closely monitoring the administration’s performance through the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. Its secret hearings, occasional leaks to the press, and brash statements challenged executive and military authority, to Lincoln’s annoyance. The Joint Committee was also in the antislavery vanguard and heavily influenced congressional actions on the matter. Seizing the initiative, it launched a spirited debate over whether slavery should be abolished, and who had the right to do so. Men like Senator Charles Sumner asserted in strong language that there was “not a single weapon in [war’s] terrible arsenal, which Congress may not grasp”—and, indeed, Congress had already grasped a good many. (Not everyone was in agreement with this proactive stance: Orville Browning, for example, had some animated discussions with the President on this theme just about the time Lucien Waters showed up on the White House steps. Senator Browning argued that to talk of proclamations and confiscation schemes was to usurp powers that were not meant to be given to the federal government and that could not be sustained.) The legislature had pushed the edges of its authority by passing bills that forbade slavery in the District of Columbia and United States territories, and by closing a treaty with Great Britain for suppression of the slave trade. While Lincoln was not necessarily opposed to these acts, he disliked the heedlessness with which some measures were approved, as well as the power plays by Congress. “Sumner thinks he runs me,” he sarcastically told a friend.36

His allies feared that allowing the legislature to take such a lead suggested serious weakness in the commander in chief. Deliberations turned as warm as the weather, peaking over a second Confiscation Act, which Congress passed in July 1862. That act stated that any slave who was owned by a disloyal master and took refuge behind Union lines would be considered a captive of war and set free. Whether the slave had been used as a tool for the Confederate war effort was no longer the criterion for manumission. Several cabinet members, as well as legislators like Browning, thought Lincoln should veto the act. Indeed Browning saw it as a watershed in his presidency. “I said to him that he had reached the culminating point in his administration,” the senator confided to his diary, “and his course upon this bill was to determine whether he was to control the abolitionists and radicals, or whether they were to control him.” Angered at the idea of being bullied by Congress, Lincoln sent a peevish note to Capitol Hill demanding that certain qualifying provisions be included in the second Confiscation Act. He also sent the draft veto message he would publish were the provisions not included—gaining the point, if not the whole match.37

Lincoln’s pique with the Congress was further evidence of his foul mood that summer, for as a general rule he had tried to work cooperatively with the legislature. Matters were exacerbated by the way some cabinet members, as well as other officials, were trying to outmaneuver him to score their own points. Browning was not satisfied by merely arguing with the chief executive about the second Confiscation Act; he began working with Attorney General Edward Bates to force Lincoln’s hand on the veto. Cabinet officers were speaking directly to generals on the sensitive subject of military emancipation, even advising them to go around the President’s orders and formulate their own policies on the ground. Petitioners wrote to Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase and other counselors rather than approach the President openly. Several cabinet officials did not hesitate to advocate practices that had not been cleared by their boss.38

It seemed as though Lincoln’s management of his government, his army, and even his own party was foundering. Leonard Swett recalled meeting with him that August and being shown a dispiriting bundle of letters from New York Tribune reporter Charles Dana, reformist Robert Dale Owen, and others. The gist of their message was that the administration was composed of “a set of ‘wooden heads’ who were doing nothing and telling the country to go to the dogs.” Senator John Sherman (brother of General William Tecumseh Sherman) was another who despaired of Lincoln’s executive ability. Writing from his home state of Ohio, he expressed the deep discontent of the public over the course of the war. “Oh God, how I feel what a blessing it would be, if in this hour of peril we had a strong firm hand at the head of affairs—who would use boldly all the powers of his office to put down this rebellion. . . . If we fail my conviction is that history will rest the awful responsibility upon Mr Lincoln—[not] for want of patriotism but for want of nerve—”39

These critics were known to hold views that differed from the President, but they were not unthinking men. Indeed Owen’s open letter to Stanton of July 23, a remarkably cogent and polished statement of Lincoln’s options regarding slavery as a war tool, was thought by Swett to outshine the President’s own ruminations on the subject. The fact was, even Lincoln’s most loyal supporters were alarmed. He himself acknowledged his responsibility for the leadership crisis in a speech to the Union Meeting of Washington on August 6. “If the military commanders in the field cannot be successful, not only the Secretary of War, but myself for the time being the master of them both, cannot be but failures.”40

And looming in the background were the awful consequences of a false step: more obscene death lists—an exhausted and shattered nation—the terrible judgment of history. Lincoln was all too aware of this. His campaign biographer, John L. Scripps, had written him a candid note, beseeching him to understand that the success of free institutions was in his hands. “You must either make yourself the grand central figure of our American history for all time to come, or your name will go down to posterity as one who . . . proved himself unequal to the grand trust,” he cried. When the celebrated historian George Bancroft similarly remarked that Lincoln’s leadership had come at a moment that would be remembered by all peoples, and that no outcome would be acceptable that did not include some redress of the slave issue, the President soberly responded that these matters were very much on his mind. It argued, he said, for clear judgment—and caution.41

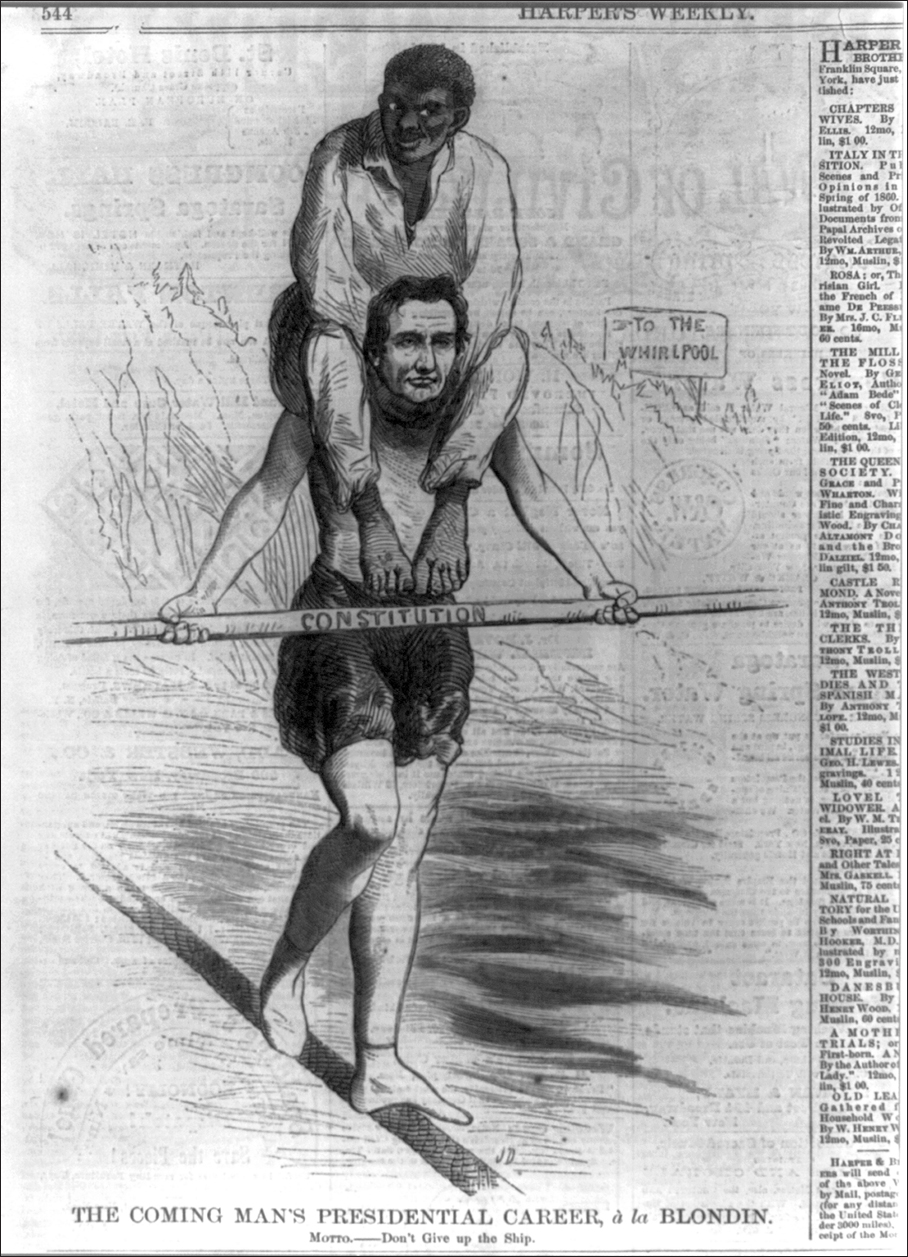

“The Coming Man’s Presidential Career, à la Blondin,” wood engraving, Harper’s Weekly, August 25, 1860

Under pressure from all sides, Lincoln likened himself to the great aerialist Charles Blondin, who had crossed the thundering chasm of Niagara Falls on a tightrope. Imagine, he said, that all the riches of the United States—its wealth and welfare, fine achievements, democratic dignity, past traditions, and future hopes—were strapped to Blondin’s back as he made the perilous crossing. Would it be helpful, he dryly asked, to have the public screaming “Blondin, a step to the right! Blondin, a step to the left!” as he tiptoed across the void? No, he concluded, it would be better to remain silent, to hold all comment but prayerful petition, until he safely reached the other side.42

Critics might complain that the presidential aerial act was “elephant-like” and that his slowness across the precipice was “marked with blood and disasters.” Still, in a remarkable show of fortitude, Lincoln did not lose his footing. Instead, he used his political finesse to form a policy that satisfied his own complex requirements and could be made to satisfy those of his diverse constituency. Although Lucien Waters and most of America did not yet know it, by midsummer he had decided to use his powers as commander in chief to release a military proclamation that would free the slaves of defiant Southerners and enlist their services for the Union Army. Such an order would preserve the authority of the executive branch without overtly defying either the Congress or the Constitution. It would also avoid punishing Unionist slaveholders, or too directly threatening the border states. In addition, it would provide much needed manpower to the Union service and demoralize the Confederate public. In short, it would buttress the President’s shaky authority, giving him the lead on both emancipation and the conduct of the war.43

It was, in some ways, a tardy move, reflecting actions that had already been occurring spontaneously, and political views that were more prescient than Lincoln’s own. (Lucien Waters had needed no such proclamation to give life to the principles he held sacred; he simply acted out his beliefs.) Nonetheless, the proclamation would also stretch the public imagination in unforeseen ways, offering a more concrete goal for the war than the status quo ante of 1860, bravely embracing a new kind of societal “progress,” and challenging the oxidizing precepts of the slave-owning community. Although Lincoln’s proclamation would also generate invective and fear, it was couched in terms that checked a mass rejection of its principles. Its cunning lay in a formulation that made it at least marginally acceptable to the majority of citizens. Many people looked back in later years and realized that it was this ability to inch along the narrow lane to consensus—to steer “the great balance-wheel”—that defined Lincoln’s political skill.44

This delicate course, melding military authority with popular opinion, was not original to Lincoln, nor did he embrace it easily. Prominent antislavery men such as the Boston preacher William E. Channing had been promoting it since the 1830s and some of those around the President, including Generals John C. Frémont and David Hunter, had tested the waters months beforehand by decreeing liberation in their military districts. Even though Lincoln overturned their diktats, those efforts helped crystallize the idea of using a military justification for a groundbreaking societal act. That rationale was beautifully set forward by Robert Dale Owen, who noted that it was a long accepted principle that the government could appropriate property in times of peril to further the common good; and given the shocking spillage of treasury and blood there was no reason to hesitate. Chase was for it, and even cautious Browning thought that slaves should be seized in order to rob the rebels of advantages in labor and morale. But Lincoln had preferred to stick to his long trodden path of gradual, compensated manumission, and to avoid provoking further hostility in slaveholding regions.45

Finally, in early July, with the Union Army in crisis, it became clear that new military muscle needed to be bared. The public was in an uproar: John Nicolay, a White House secretary, complained that he “heard more croaking” in those days than any time since the war began, and that it was coming from all social classes. The pressure was heightened by reports—true or not—that McClellan was about to defy the commander in chief by freeing the slaves under his jurisdiction, and that “the President would not dare to interfere with the order.” Lincoln made one last unsuccessful effort to push gradual emancipation, then seriously pondered the course of “military expediency” his counselors had proposed. His favorite Kentuckians were also softening their opposition to liberating and arming blacks, and this may have influenced his change of heart. Recognizing that “we had about played our last card, and must change our tactics, or lose the game!” he began at least mentally to draft a proclamation. Newspapers speculated that the move was afoot, cutting through the stagnant air with rumors that border state slave interests might no longer trump humanity and national unity. 46

On July 13 Lincoln told several cabinet members he now felt it was essential that the slaves be freed or the country itself would be indefinitely bound by the chains of war. By the time he called his cabinet together a week later to discuss the new policy, the President had written a draft proclamation. On reading the paper aloud, he again met with a frustrating variety of opinion. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton and Attorney General Bates gave their immediate and hearty approval. Chase remained largely silent, though he confided to a friend that “these measures, if all of them are adopted will decide everything.” Postmaster General Montgomery Blair sent a disapproving letter that ran to nine pages. The comments that had the most resonance for Lincoln, however, were those of Secretary of State William Seward, who wanted to be perfectly sure the citizens would accept this radical action. For although the proclamation was carefully characterized as a measure that would help win the war, and stopped short of universal manumission (critics would complain that it left more than 800,000 souls in bondage), few doubted that the decision would “loose the wheel” on the emancipation movement, propelling it forward with new momentum. Lincoln agreed that such a daring political move, made while the war news was so dismal, might appear to be the “last shriek, on the retreat.” So for the remaining months of summer, amid the oppressive national malaise, he kept quiet about the proclamation. Tensely gauging public opinion, he waited for victory.47

The First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation, engraving after Francis B. Carpenter’s 1864 painting. [From left to right: Edwin M. Stanton, secretary of war; Salmon P. Chase, secretary of the treasury; President Abraham Lincoln; Gideon Welles, secretary of the navy; Caleb B. Smith, secretary of the interior; William H. Seward, secretary of state; Montgomery Blair, postmaster general; Edward Bates, attorney general.]

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

If Lincoln had already determined his course toward emancipation, why would he make such an easily misconstrued remark to Lucien Waters a few weeks later? Most likely he was still testing the strength of popular support. One of the reasons he rarely turned away petitioners like Waters was that it helped him to hear their views. Immersion in the throngs became what Lincoln later called his “public opinion baths.” It was a way, in the days before pollsters, that he could unofficially gauge the effect of the war on the national psyche. A shrewd judge of the popular will, Lincoln did not believe widely held views could be disregarded and once wrote that there was no higher consideration in a democracy than the force of public sentiment. With it, he maintained, “nothing can fail; without it nothing can succeed.” It was molding popular perception, he noted, that was the test of the politician.48

The difficulty of leading public opinion, however, was one of his greatest frustrations. It was also a deep source of criticism. There were plenty of people, including loyal allies, who questioned the President’s judgment in exhausting his time and temper with the petty concerns of persons “proper and improper” who jostled through his anteroom. His awestruck young secretaries, as well as Senator Henry Wilson, were among those who tried to dissuade him or redirect his schedule to more official business. Lincoln himself expressed annoyance with the crowds, and admitted his bone weariness. Still, he discouraged anything that kept the masses away.49

The teasing question was (and is now) whether his hands-on democracy was actually persuading anyone—whether it was at all effective in shaping the popular will. Adam Gurowski, a grudgingly respected Washington gadfly, doubted it, and said so in his usual unrestrained verbiage: “Mr. Lincoln never did anything in advance of the people’s wish, never showed any prescience. Lincoln acts when the popular wave is so high that he can stand it no more or when the gases of public exasperation rise . . . powerfully and strike his nose.” It was not just blowhards like Gurowski who were worried. Attorney General Bates thought the President’s “amiable weakness” allowed him to be co-opted and darkly noted in his diary that public opinion was “always a manufactured article” and that weak men allowed their enemies to control public opinion against them, but strong men created popularity for themselves. A War Department official commented that Lincoln never rose above the people and was strong just so long as he led only in the direction they wanted to follow. From Massachusetts a concerned woman expressed herself plainly about this to Salmon Chase, stating that in the “mazes” of the slavery issue she hoped “neither you nor Mr. Lincoln would wait for the popular voice but would lead it by definite actions.” Emancipation was indeed a labyrinth and Lincoln was still feeling his way through it.50

His public opinion “baths” were probably inadequate to the challenge. (Historian David Donald called them “retail, rather than wholesale, tactics to shape public opinion.”) However, tradition and geography had given him few overt ways to reach the populace directly. Speechifying was not thought seemly, and even his messages to Congress were read aloud by the chamber clerks, with the pithy bits lost in their drone. Newspapers were unreliable and highly local. The only one with any pretense to national scope, the New York Tribune, was edited by the capricious Horace Greeley, who was hardly a trusted ally. It was not that Lincoln was unwilling to use a politician’s tools to prod his constituents. No prude, he did not hesitate to be manipulative, elusive, or downright disingenuous when it served his purpose of swaying public sentiment. He knew when to be coy and at the time he met Sergeant Waters he thought it prudent to mask his intentions. The President was in fact unwilling to reveal his hand even to favored cronies at that sensitive moment, let alone confide in an unfamiliar cavalryman. The last thing he wanted to do was feed the relentless Washington rumor mill by letting his emancipation plan out piecemeal.51

Instead he was looking to shape a platform that could be widely accepted in the spirit of national interest. To consolidate support he often floated positions that rose above parochialism to a larger ideal that could be embraced by everyone. Sometimes he did it through his cornpone parables, and sometimes by directly challenging his interlocutors to view a situation from his perspective. He used this latter ploy a few days before he encountered Lucien Waters. When Cuthbert Bullitt, the U.S. marshal for Louisiana, passed on complaints that the administration’s contraband policies were disadvantageous for Unionist slaveholders in the federally occupied portion of the state, the President retorted: “What would you do in my position? . . . Would you give up the contest leaving any available means unapplied?” Then, in a masterly argument, he subordinated all other interests to the prime goal. Everything he did, Lincoln protested, was done for one reason: to uphold the Union. “The truth is, that what is done, and omitted, about the slaves, is done and omitted on the same military necessity. . . . I shall not do more than I can, and I shall do all I can to save the government, which is my sworn duty as well as my personal inclination.” To give the message a longer reach, he showed it to friends, who were impressed at his unfettered determination to protect the government.52

A few weeks later, Lincoln hit upon an even more effective way to manipulate the national viewpoint when he published a public letter in response to a particularly critical New York Tribune piece by Horace Greeley. Reprinted across the country, it gained immediate currency. In it he once more placed the country’s integrity above all other considerations and clearly stated that any form of emancipation was simply a tool for preserving the Union. Understanding that much of the citizenry needed justification for an action as bold as liberating the slaves, Lincoln made the one argument with which most everyone could agree.53

There was yet another public issue stifling the air when Lucien Waters appeared uninvited on the White House portico. As an observant abolitionist pointed out, Lincoln dreaded “the magnitude of the social question” and wondered whether the slaves could be freed without rending the nation’s civil fabric. The President had long been concerned about this and spoke openly about the perils of “amalgamation.” For that reason he advocated colonization, by which liberated blacks would be removed to another country. He had a pronounced interest in this program, which on some occasions he dubbed “deportation” and on others characterized as “voluntary.” It seems to have stemmed from the early days of his political career, when colonization had been promoted by his hero, Henry Clay. “I cannot make it better known than it already is, that I strongly favor colonization,” Lincoln declared a few weeks before signing the Emancipation Proclamation. He maintained his enthusiasm for resettling freedmen at least until mid-1864, by which time several actual attempts at the project had ended in disappointment, if not disaster. It was indicative of Lincoln’s compartmentalized beliefs about African Americans, in that while he genuinely believed that slavery was wrong, and that “the man who made the corn should eat the corn,” he also resisted the ideal of real equality in a color-blind society. It also reflected his conservative nature—he was a man of his time and a cautious one too—and his dislike of sudden change. Moreover, the President knew that most white Americans agreed with him and were fearful of black customs and competition. He was skating on thin constitutional ice in his advocacy of emancipation and felt that if his decision to “proclaim” liberation was to be accepted, it must come with a social outlet rather than a threat.54

Two days after Waters penned his account of their tête-à-tête, Lincoln met with a group of African American leaders and proposed that after liberation all blacks should relocate to another country. There was little dialogue at this session. Lincoln read from a prewritten paper that, while attempting courtesy, was brutal in its paternalistic directness. He once again reiterated his belief that the differences between the races were too vast to be overcome, and that this unpleasant fact had to be accepted. “I cannot alter it if I would,” were his words. While recognizing that blacks had suffered greatly, he seemed to blame them not just for white discomfort, but for causing the war, apparently forgetting that Africans had been involuntary immigrants to America, and that blacks had not originated the conflict—slavery had. He then threw out the question of whether his audience would not join him in promoting emigration, painting a picture of a new chance in a new land. The former slaves should embrace a revolutionary spirit akin to George Washington’s and make a gesture benefiting everyone—one that would help them shed the discrimination of white Americans. Unfortunately, the situation he described (he had Central America in mind) did not mesh with information at his command, which had given a grim description of fetid air and filthy corruption in the proposed new homeland.55

Some have viewed the meeting at least in part as a public performance, meant to reassure nervous Northerners that they might not have to absorb the freedmen. That a journalist was present, and a story carried around the country the next day by the Associated Press, points to this. But Lincoln’s decades of support for the issue and his eagerness to put the theory into practice in 1863 and 1864 argue against a stage-managed act. Indeed, it appears that in his mind, emancipation could not be justified without a program of removing the freed people. Nor is its unseemliness merely a symptom of present-day sensibilities. In 1862 most African American leaders, as well as progressives, thought the meeting more than unfortunate. “How much better would be a manly protest against prejudice against color!—and a wise effort to give freemen homes in America!” Treasury Secretary Chase exclaimed to his diary the next day. Frederick Douglass was so offended by reports of the encounter that he viewed them as proof of Lincoln’s “contempt for Negroes and canting hypocrisy” and fourteen years later still chafed at the memory. A wide variety of newspapers, including the very ones Lincoln may have been trying to influence, protested against its impracticality as well as its inhumanity. “Mr. Lincoln draws pleasing pictures of the prosperity which the exiles may enjoy in their new home, and earnestly urges them to give one more proof of their regard for the white man by getting out of his way,” the popular Harper’s Weekly snidely opined.56

Lucien Waters, who abhorred the biases that underpinned slavery, was in agreement with Harper’s. More idealistic than Lincoln, he fought the war as much to shackle prejudice as to liberate the bondman. The contrast between his view of emancipation and that of his commander is noteworthy. Waters made it his business to smuggle slaves through the swamps of Maryland to a life free of coercion, but he also carried their testimony—precious in its rarity—through the bayous of bigotry, to prove their worthiness as citizens. Refusing to limit himself to liberating African Americans, he chronicled their abuse by former masters, voluntarily sending in reports on the treatment of the contraband. Even when his regiment faced horrible decimation during bitter and fruitless combat in Louisiana and he plaintively wrote that it required “all the philosophy & fortitude” of his character to keep going, Lucien knew he was fighting for universal values, not just military advantage. “The glorious cause for which I contend, consoles me for all suffering & sacrifices,” he maintained. “I thank God that I am counted worthy to be one of the number who are appointed to sustain the hopes of humanity in freedom & equality of rights.”57

Ultimately, Lincoln would also embrace a more inclusive doctrine, but not until the opposition of Latin American nations, the dearth of colonization volunteers, and a tragic experiment near Haiti proved his “solution” unworkable. The need to absorb the former slaves, particularly those who had fought for their freedom, would force the President to change and adapt—to take a leap in the dark by accepting that inevitably American society would become multiracial. The social dislocation he hoped to avert was, in fact, unavoidable.58

No wonder, then, that the chief executive whom Sergeant Waters encountered was in a testy mood. The critical deliberations of that overheated summer and the necessity to keep mum; to wait and hope and meanwhile absorb criticism; to be disingenuous when he prized candor; to endlessly explain himself—all this weighed on Lincoln and caused him to snarl in frustration. With pressure from every side and slavery on his mind, it is not surprising that he assumed Waters’s business would add another noisy opinion to the cacophony around him. Lincoln’s rude comment may also have been an attempt to evade the troublesome issue of slavery altogether, by closing the conversation before it began. But why the choice of words, the offensive expletive about the “Eternal niggar”?

The record is clear that “nigger”—and its second cousin “cuffee”—were part of Lincoln’s private as well as public vocabulary. The body of evidence from those who knew him is so great that there can be little doubt that he used the coarse epithets in anecdotes and stories. He hugely enjoyed David Ross Locke’s satirical Nasby Papers, featuring the eponymous poor white preacher who spouted pearls of wisdom such as “Niggers was ordained 2 be bondmen from the very day Noah took a overdose uv the Great Happyfier.”59 Journalists who attended Lincoln’s speeches during the 1850s reported him frequently evoking the word, though it is not always apparent how much of this was the speaker and how much the scribe. It is notable, however, that many of these reports were corrected by Lincoln himself, who may have sometimes eliminated the attention-grabbing pejorative.60

After he entered the White House, Lincoln evidently thought better of using such language in his presidential statements, though racial epithets are frequently quoted in his private conversations. In later years, friends and admirers, including historians, tried to explain away his crude usage, some on the grounds that it was just an innocent way of provoking mirth, others that the greatness of his soul overrode any vulgarity of voice. Still others remarked that the unpleasant words should be covered up since the public simply did not want to know this side of Lincoln’s character.61

There is no question that the word “nigger” was a derogatory term during Lincoln’s lifetime, not considered a part of a gentleman’s speech. As early as the 1760s, writers noted that words like “Negur” were used by the “vulgar and illiberal” to demean their subjects. By 1837 a visitor to the United States commented that “‘Nigger’ is an opprobrious term employed to impose contempt upon [blacks] as an inferior race.” Years before abolitionist William Seward became Lincoln’s secretary of state, he was reportedly so offended by the extensive use of the expression by Senator Stephen Douglas that he once berated him by saying, “Douglas, no man who spells Negro with two gs will ever be elected President of the United States.”62 In one instance Lincoln apparently tried to explain his choice of the word “cuffee” by saying that he was a Southerner by birth “and in our section that term is applied without any idea of an offensive nature.” But, if crude, Lincoln was not naïve, and if this anecdote is true, it argues more for the ubiquity of racial slurring than the President’s unlikely ignorance of its denigrating tone. For while it is true that the use of such words was widespread (even Senator Benjamin Wade, an aggressive critic of Lincoln’s slow move toward emancipation, called Washington a “god-forsaken Nigger rid[d]en place”), one is hard-pressed to explain it away as a term of regional slang. Indeed dismissing the degrading connotation of the words itself makes an uncomfortable statement.63

Like all profanity, “nigger” was meant to show the speaker’s irreverence and shock his audience. The fact that Lincoln seemed to use such words in anger or under pressure underscores his understanding that these were expletives, chosen to demean the object of discussion or emphasize his irritation. In addition to the recollections of his minstrel-style stories, there are private tales like that of Waters, in which he blurts out the remark in annoyance, using it to put off his interlocutor. In every one of these incidents, the statement was abrupt and the emphasis ugly. Indeed, if alienating his audience was Lincoln’s goal, he surely succeeded.64

In public speaking, grabbing attention seems to be what Lincoln frequently wanted to achieve by using such a loaded expression. He had more than a little of the thespian in him and was a gifted writer: he knew the value of words. Without excusing the crudeness of his choice, it is evident he often said it when he wanted to mock those who used the term without irony—in other words, to belittle the belittlers. Lincoln regularly called on sarcasm to make his sharpest points. Earnest and eloquent speech sometimes fell flat with the masses, and what better way to point up the vulgarity of the bigot than by parroting his words? And Lincoln was an accomplished mimic. Many of his references to “niggers” were in speeches lampooning Stephen Douglas for his fable of the Negro and the crocodile, in which black folks were said to be to the white man as reptiles were to Africans. The joke was on Douglas in these performances, not on the blacks. Interestingly, Lincoln was just as capable of cruelly imitating pompous New Englanders as he was Southern racists. In one hilarious impersonation, he caught the exact tone of a Democrat who was trying to blame a shoe factory strike on the conflict over slavery: “I cannot dawt thot this strike is the thresult of the onforchunit wahfar brought aboat boy this sucktional controvussy!”65

Lincoln’s use of such pejorative speech also points up the power of environment on even the largest intellect. There is no reason to doubt his assertion that he believed slavery was intrinsically wrong and that he could not remember a time he did not feel so.66 Casually referring to “niggers” reflected cultural boorishness rather than naked hypocrisy. Americans had woven such an intricate pattern of racial relationships, such a set of conflicting principles and interactions, that few escaped the contradictions. Robert E. Lee, for example, was never known to have uttered the word “nigger” and thought such language beneath him; yet he treated the slaves under his control with harsh disdain. When Lincoln slipped into coarse speech, or guffawed over Reverend Nasby’s preposterous pronouncements, he was reflecting a way of acting he had absorbed almost by osmosis, not necessarily a politically motivated code of conduct. Indeed, given his impoverished frontier upbringing, it is striking that he did not let prejudice prevail more often.67

It is also notable that Lincoln never used the word “nigger” in letters or official texts, and rarely in serious extemporaneous speech. Perhaps he simply thought it inappropriate for more formal writing. But he also understood the difference between the transience of mere talk and the lasting quality of the written word. Casual words, as Lincoln’s friend Joshua Speed once reminded him, are “forgotten . . . passed by—not noticed in a private conversation—but once put your words in writing and they Stand as a living & eternal Monument against you.”68

Whatever Lincoln’s motives, his language failed to impress Lucien Waters, who viewed it as the unbecoming statement of a man still enchained by the influences of the Slavocracy. Waters did not chastise the President, however, though he was chafing to do so. The sergeant had observed the exhausted leader at close range, knew that he had scarcely a moment to relax, realizing as well that the demands of war and America’s diverse constituency made every decision hard and contradictory. Moreover, Waters had an object to achieve with his petition—he wanted that furlough. As he told his brother, he therefore kept “a close mouth.”69

And what of his petition? Did Lincoln grant Waters his leave? It appears not. The timing was disastrous, because one of the many questions vexing Lincoln was how to invigorate his military machine. The Union Army was suffering stalemate in the West and before Charleston, and it was outmaneuvered by Robert E. Lee in Virginia. Losses in recent battles had been stunning. The size of the Confederate force before Washington was a subject of anxious discussion, with rebel strength greatly exaggerated. By early August the President had approved a change of command and a controversial draft of 300,000 men, with serious penalties for those trying to dodge their responsibility. The new influx of green soldiers would need supervision. Colonel Swain had warned Waters that the army chiefs were looking to keep seasoned men, so his plan was therefore unlikely to be approved. Swain had his ear to the ground. The commander in chief himself valued the veteran units and said that “one recruit into an old regiment is nearly . . . equal in value to two in a new one.” Under such circumstances, Lincoln could ill afford to indulge one officer’s self-serving schemes. Indeed, a senior officer in the War Department witnessed the chief executive brush away another soldier from Scott’s 900 during a similar petition for personal favors. “Now, my man, go away, go away!” he cried out. “I cannot meddle in your case. I could as easily bail out the Potomac River with a teaspoon as attend to all the details of the army.” In the end, military records show that Waters served throughout the war without a single day of furlough.70

An acquaintance of Lincoln once remarked that he was “an artful man.” Lucien Waters could not have guessed on that August day the extent to which “Uncle Abe” was practicing his art, balancing on the cusp of history. Although it was a brief exchange, Waters glimpsed the President in all his complexity: the crude backwoodsman; the harried public servant; the dedicated champion of American-brand democracy, who passionately believed that the people must have access to power; the hardheaded politician; the gangly, near gargoyle of a man. Waters thought perhaps he should have taken Lincoln to task for his crass speech but was astute enough to perceive the great pressure under which he was laboring, and ultimately rationalized and forgave the outburst. What is remarkable is the directness and confidence with which these men faced each other. Lincoln did not hesitate to listen to the concerns of a common citizen, and Lucien showed no fear in the presence of the nation’s leader.

Service record of Lucien P. Waters

NATIONAL ARCHIVES

The differing brands of emancipation favored by Abraham Lincoln and Lucien Waters are what make their brief encounter so compelling. Waters, more impatient and optimistic, showed his dedication through actions, not fine words. Convinced that Americans could and should embrace the freedmen, he was loath to shunt them into a separate future. His war was one of unwavering conviction. When he saw that the government would not instantly eradicate the hated institution of slavery, Waters simply moved to remedy the situation himself. Lincoln was without question the more hesitant liberator. His views were cautious and pragmatic, and more skeptical about both African American potential and his nation’s capacity for racial absorption. To uphold the law, he was willing to promote political practices that he personally abhorred. Caught within a dynamic that he could not control, Lincoln was forced to evolve his thinking over time, as facts proved his assumptions wrong and popular clamor made his divisive policies obsolete. But the stakes were also higher for Lincoln. As a sitting president, bound by law and tradition, and entangled in an epic societal transformation, he could not just mount his iron-gray steed and single-handedly entice slaves to freedom like an idealistic sergeant. He accomplished the great work of emancipation, but without the zeal of Waters and his political counterparts, who pushed him until his views more closely reflected the absolutism he had once shunned. In the end, probably both perspectives were needed to clear the awful stench of slavery from the land.

It is too bad that Waters did not enjoy a richer dialogue with his president, for they had much in common. At heart both were distressed by the festering sore of slavery; both wanted to lance the boil. Both cherished a belief in democracy’s innate practicality and goodness. In their short conversation they were living out the fundamental principles of the republic: that in a nation of the people the dialogue between governor and governed is essential; that where all men might rise there can be no pretense—no undue deference from a simple sergeant; no arrogance or intimidation from his commander. Waters belonged to an outfit charged with protecting the President, but Lincoln understood instinctively that he must not be too protected, lest he become isolated—an island of power without a public causeway to keep him honest and responsive and relevant.

When Lucien Waters described his meeting with Abraham Lincoln, he only meant to give his brother a little picture of an eccentric leader in an unguarded moment. What he left us was a lasting sketch of direct democracy, in all its roughness and grandeur.

Abraham Lincoln’s commitment to emancipation and, ultimately, a more equitable place for blacks in American democracy grew over time. He never embraced the idea of perfect equality among the races, but he did drop his more blatant prejudices, including his public support for colonization. He was at first noncommittal about the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which abolished slavery forever from all parts of the United States, but later helped to promote its passage through the House of Representatives. He signed the measure, sending it to the states for ratification, on February 1, 1865. He began work that would redefine the meaning of citizenship and won the respect of many African Americans, including Frederick Douglass, who had criticized him throughout the emancipation summer. We do not know, however, what his vision for a postwar society would have been, for it is impossible to ascertain from the contradictory documents left to us after his assassination on April 14, 1865.71

Lucien Waters continued to serve with the Eleventh New York Cavalry until 1865. After several years of lobbying, in 1864 Colonel James B. Swain finally succeeded in having the men of Scott’s 900 transferred to the field. Their new assignment was to scout and interrupt “disloyal” behavior, first in Louisiana, and later in Tennessee and Arkansas. It was punishing work amid a hostile citizenry. Aggressive fighters making lightning raids, such as Nathan Bedford Forrest, challenged the regiment, as did the harsh climate. Sickness took its toll as well: Scott’s 900 lost an astonishing 819 men to disease, at least in part due to the incompetence of Union Army doctors. Waters wrote bitterly of the deprivations suffered by the men. Nevertheless, he was determined to persist in his fight for “the priceless legacy of human freedom which the future imperatively demand[s] of us.” He also continued to work on behalf of the freedmen, helping many to escape the lingering burdens of servitude and writing about the disgraceful treatment blacks received at the hands of their former masters. It was perhaps an indication of the hardship the regiment suffered that Waters left the army on March 28, 1865, just weeks before the end of the war and exactly three years to the day from his initial appointment.

After he was mustered out, Waters returned to his fiancée, Mary G. Smith, and his career in Brooklyn. He planned to be married in late May 1866. When Lucien failed to appear at the wedding, his bride tracked him down at his brother’s house and discovered he had suffered a stroke, falling in the street just after purchasing a wedding ring. Mary and Lucien were married as he lay in bed. He died a few days later, on June 10, 1866.72

Following is the text of Lucien Waters’s letter to his brother Lemuel Waters of August 12, 1862, with its original punctuation and grammar.

Camp Relief “Scotts 900”

Washington D.C. Aug 12 ’62

Very dear Bro. Lemuel & Family:

I have only a few moments in which to answer your two very kind missives, lately received from New York & The Catskill. You will excuse me if I do not as extensively reply to your patriotic & metaphysical suggestions as The importance of The Themes would seem to demand. I am not in The best of health These days, & having very arduous tasks to perform in keeping my Co. straight in The absence [of] my superior officer, I have not time to devote to any Thought on any subject disconnected with my duties or even to read The news of The day. After The duties of the day are over, I try to keep awake by The Camp fire & Think over The past with its many pleasing recollections, to Think of the gigantic issues which are growing out of This nations present convulsions, & Throes to rid itself of its many hellish corruptions, & to plant my feet on The only ground on which I have ever cared to stand; & That is to labor & suffer alone with The Thought That my motive was right & Though The issue was not as sharp & desisive as The more advanced & patriotic minds would have it, & Though incompetency & tretchery characterized The heads of The government, yet I try to draw a balm from our present ills, & trust The all-wise controller of events to so shape our reverses as to awake The canelle73 of America, to Their rights & The rights of Africa’s trodden race. I would here rehearse a conversation which I had with President Lincoln as I presented a petition for him to sign in conjunction with my Col. for my discharge from The Army. He in his characteristic style but not in a very dignified manner, took the said petition & sitting down on The marble pavement of The portico of The White House with his back against one of The south pillars, & with his feet drawn close up under him Thereby elevating his Knees as high as his head, [picture drawn here] turned his head up & said that it had probably something to do with “The damned or Eternal niggar, niggar.”!!. That spoke volumes to me as to the influences by which he was constantly surrounded, & which influences are the same as have for the past Thirty years made slaves to The aristocratic minds of the South, of every Executive who has occupied a place at the head of the nation.

A man has much to contend with, that would keep pure where such insiduous & snaky influences are constantly brought to bear. I should have given him a “right smart” talking to had I not an object to gain. For policies sake I for once kept a close mouth, & not through fear. With all respect for his office, I should like to have given him a dressing down as father sometimes says. I pity the man from my heart for he is nearly worked to death. His private hours are scarcely kept sacred to his repose & comfort, & he may have been vexed & tormented with a hundred that very day who were trying to worm something out of the government for their own personal agrandiziment. Charity, Charity should be our watch word as well as the keen acumen of criticism.