4

OF FATHERS AND SONS

John Ross did not look like a storybook Indian: he wore no paint or feathers, and his expressive voice neither whooped nor grunted. Nonetheless, he was chief of the Cherokee, one of the largest and most resourceful tribes in North America. On September 11, 1862, he arrived at the White House, dressed in the fine clothes he enjoyed, a top hat crowning his brow. He was an old hand at this Washington game. For more than thirty years Ross had been parlaying with presidents, Supreme Court justices, and congressmen to uphold his people’s rights against an ever encroaching white tide. Now he had come once more to speak with the “Great Father,” as many Native Americans called the President. Ross was better educated than the man he was about to meet; had been in public office longer; and was more financially secure. As head of a sovereign nation he had important business with Abraham Lincoln, and he was anxious to get to work.1

Ross’s skill as a leader was honed during a turbulent period in Cherokee history. Born in 1790 to a Scottish father and half-Native mother, he was raised bilingually, studying both sacred Cherokee traditions and Enlightenment principles. Ross—or Guwisguwi (“A rare bird”)—was drawn to politics, and by age thirty his talents were well recognized. In 1827 he was elected president of a convention that drew up the first codified tribal statutes in North America. Modeled after the United States Constitution, it featured three clearly defined branches of government, with a principal chief who was elected every four years. During the same period, the Cherokee established newspapers, a rigorous school system, and profitable businesses. A “syllabary” was developed by the genius named Sequoyah—a rare instance of nonliterate people inventing a system of writing. After its publication, literacy among the Cherokee surpassed that of their white neighbors. In 1828 Ross was elected the first principal chief of this energetic nation.

Ross’s priority was to protect the Cherokees’ fertile territory, which bordered on Georgia and Tennessee. Land lust had begun to squeeze the area’s “Five Civilized Tribes,” and President Andrew Jackson strongly supported white demands for open settlement. Lobbying relentlessly for peaceful relations, Ross hired William Wirt, a noted attorney, to represent his people before the law. John Marshall’s Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Cherokee, defining them in Worcester v. Georgia as a sovereign nation, and guaranteeing them protection on their land. But the iron-willed president and Georgia officials defied the rulings, demanding that the Indians be moved west of the Mississippi. “John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it!” Jackson reportedly exclaimed. “Build a fire under them. When it gets hot enough, they’ll go.”2

Under pressure, the Cherokee themselves began to differ on their best course. Ross, with his faith in the law, could not believe they would be forced to leave. Others, sensing their options would only diminish, advised negotiating an agreement before they were dispossessed altogether. Three prominent men challenged Ross: John Ridge, Major Ridge, and Elias Boudinot, the brilliant editor of the Cherokee Phoenix. Boudinot’s brother, Stand Watie, a lawyer and an entrepreneur, joined them to make a potent opposition. Against Ross’s will, these men signed the Treaty of New Echota in 1835, which granted the Cherokee a homeland on the southwestern plains, protection, and annuities if they relinquished their ancestral lands. Under the treaty terms, the U.S. Army escorted the tribe on a forced march, thousands of miles, to “Indian Territory” (present-day Oklahoma). This “Trail of Tears” was a logistical and psychological horror that cost a third of the Cherokee their lives. John Ross lost his wife, Quatie, as well as substantial property, in the catastrophe.3

Still chief of the nation, Ross remained resilient, establishing successful businesses and working to unite his exhausted people. Factionalism was his main concern. Tensions with the pro-treaty bloc had heightened after the Ridges and Boudinot were murdered by men loyal to Ross—though apparently without his knowledge. Watie’s rivalry was sharpened by anger over his brother’s death, as well as financial interests in developing the new land. Important differences of opinion also existed about what defined their nation—whether it was bound by traditional kinship relations; or by laws and institutions that would include those of mixed-blood and non-Cherokee backgrounds. In addition, there were frictions with the “Old Settlers”—tribes removed to Indian Territory prior to the Cherokees’ arrival, including the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole.

For two decades Ross struggled to strengthen the national structures he thought underpinned Cherokee success and to renew his people’s vitality. By the outbreak of the Civil War, he had succeeded to a remarkable degree. Jealousies were muted, at least on the surface. Watie and Ross cooperated in council meetings; schools and churches were created; democratic institutions rebounded under the roof of a handsome capitol building; agriculture and husbandry flourished as they had hoped. Progressive in his views, Ross introduced humane prison sentences and built seminaries for girls as well as boys. The chief and his new wife built a large house called Rose Hill, owned fifty slaves, and led a life befitting the head of a proud nation. A Cherokee man described this era of peace and comparable plenty, on the eve of war. He longed “to hear the cows lowing the hogs squealing and see the nice garden and the yard with roses in the waving wheat and stately corn growing,” he told his family, “and be conscious that there was no one in want.”4

In 1862 John Ross was a slight, silver-haired septuagenarian, but in attainments and renown he stood as high as Abraham Lincoln. There were many similarities between the two men that might have created a sympathetic bond. Both had been born outside the easy paths of success but had risen through talent, pluck, and opportunism. Both believed fervently in education as a refining influence on society. Ross’s gift for the elegant phrase at times rivaled the President’s, and he shared Lincoln’s understanding of how shrewd words could shape political ends. Each expressed a profound dedication to democratic government and an understanding that compromise and unity were its essential underpinnings. Ross did not consider himself a vassal of the United States, but he admired its institutions, and deftly interwove them with native traditions of negotiation and consensus building—a style that resembled Lincoln’s own way of governing.5

As the country splintered over Lincoln’s election, Ross viewed the situation with concern. “If the good people of these United States duly appreciate the blessings of liberty they enjoy,” he told his wife, they “should choose some great & good conservative Patriotic Man . . . under the Banner of the Union and Constitution.” His vote would have been cast for the Constitutional Unionist John Bell, not Lincoln. Ross was wary of the Republicans—wary, as a slaveholder, of their policy against the institution’s expansion; and nervous about William Seward’s claim that the territory south of Kansas should be “vacated” by the Five Nations. Ross was also only too aware of the fragile geographic position of the Cherokee, surrounded as they were by Kansans, who were engaged in a violent internal struggle over slavery, and Texans, who were already blustering about disunion. Hoping to maintain neutrality, he shunned zealous secessionists, as well as “Abolitionism, Freesoilers, and northern Mountebanks.”6

Ross admitted that the Cherokees’ Southern roots and slave property fostered greater cultural affinity with the secessionists, but he also recognized he was bound by treaties with the United States that theoretically safeguarded his people. “‘The Stars and Stripes’ though an emblem of superior power, is also the Shield of [Cherokee] protection. They all know that Flag—many of them have fought beneath it,” he wrote defiantly to a newspaperman who had “hissed” about the pro-slavery sympathies of “savages.” “But,” Ross added, “if ambition, passion and prejudice blindly and wickedly destroy it . . . they will go where their institutions and their geographical position place them.” Although he deeply regretted the conflict, Ross made it clear his main concern was to prevent outside interference in Cherokee affairs. A group of Texans, sent to woo the chief, found him “diplomatic and cautious,” and noted he agreed with Lincoln’s refusal to consider the Union dissolved. Declining to join either side, Ross advised the Cherokee to refrain from partisan speeches or provocative activities that might incite a fratricidal war.7

But the strategy of neutrality failed. A convergence of events tested Ross’s impartiality and ruptured the tenuous cooperation among tribal members. With the onset of war, Lincoln declined to supply the protection the Cherokee had been promised, instead removing federal troops from the borders of Indian Territory. It proved an unfortunate policy. Not only did the President’s action break treaty obligations, leaving Ross and his fellow chieftains vulnerable to rebel incursions, it closed the Union’s best route for infiltrating Texas, while allowing the Confederates to penetrate toward Kansas. Indian agents in the vicinity—many of them holdovers from the Buchanan era—aided the unrest by openly supporting the South, sometimes causing drunken demonstrations. (Lincoln claimed it was impossible to get new men into place, but the accounts of eager politicians and speculators show they had little trouble moving into the area.)8 Factionalism among the Five Nations also played a decisive role in undermining neutrality. The Choctaw and Chickasaw were committed to slavery and unequivocally for the South; the Seminole were fervently antislavery, but comparatively weak; Creeks and Cherokees were divided among themselves. Also opposing Ross’s policy were Stand Watie’s followers, who were largely slave owners and solidly pro-South. They saw opportunity within shaky tribal politics, as well as benefits in doing business with a Confederacy anxious to make concessions. Feeling that Ross’s National Party had for years “had its foot upon our necks,” Watie tried to force a confrontation by attempting to raise the Confederate flag in Tahlequah, the Cherokee capital. Some 150 “armed and painted” neutralists halted the demonstration, but Confederate leaders quickly capitalized on the divisions.9

Using an effective carrot-and-stick policy, Jefferson Davis posted the belligerent General Ben McCulloch in the region while sending a smooth-talking envoy, Albert Pike, to negotiate with the tribes. Pike offered the Cherokee a nearly irresistible deal. It included everything they had been trying to obtain from the United States for more than a dozen years, including armed protection; unrestricted title, and perpetual possession of their country; payment of $500,000 for lands bordering Kansas that were destabilized by squatters and outlaws; Confederate assumption of annuities; and a delegate seat in the Confederate House of Representatives. Pike considered Ross a smart, decisive leader, but he was able to shake the chief’s determination by threatening to make a direct agreement with Watie. Correctly surmising that Watie had everything to gain by a tribal split and backed by the strong presence of Confederate soldiers, Pike wedged apart the unity Ross had wrought with so much difficulty.10

Ross tried to rally the Five Nations, or persuade them to form a coalition, but by the summer of 1861, the other tribes had formed alliances with the South—and Watie was leading a regiment in their support. Surrounded on three sides by hostile forces, abandoned by the federal government, and troubled by a string of Union defeats, including a bloodbath at nearby Wilson’s Creek in Missouri, Ross suspected Confederate leaders were about to forcibly end his neutrality. Federal agents finally impressed Washington with the gravity of the situation, but the administration fumbled arrangements until it was too late. On August 21, 1861, Ross called together four thousand tribesmen and appealed in eloquent language to their long history of honor and cohesion. As he had throughout his career, Ross deferred to what he believed was the best interest of the Cherokee; and, to the surprise of his audience, ended his speech by announcing an alliance with the Confederacy. “We are in the situation of a man standing alone upon a low, naked spot of ground, with the water rising rapidly all around him,” Ross poignantly declared. “If he remains where he is, his only alternative is to be swept away and perish. The tide carries by him, in its mad course, a drifting log. . . . By seizing hold of it he has a chance for his life.” Advising the equally divided Creeks to follow his lead, Ross signed Pike’s treaty on October 7. “The Cherokee People stand upon new ground,” Ross told his nation. “Let us hope that the clouds which overspread the Land will be dispersed and that we shall prosper as we have never before done.”11

It had been the most pragmatic of decisions, born of a need to survive. But Ross’s hope for peace and Indian unity was quickly disappointed. The Cherokee raised two regiments for the Confederate Army, one under Stand Watie and another led by men who had supported Ross. However, Opothle Yohola, the neighboring Creek leader, was strongly pro-Union. Convinced his tribe would be massacred by Southern forces, he took flight to Union lines in Kansas, joined by some of the loyal Cherokee. He was pursued by rebel Colonel Douglas H. Cooper, with an army that included soldiers from all five tribes—a grim realization of the fratricidal war Ross had worked to avoid. After a series of short, but bloody battles, Cooper took hold of Indian Territory. Thousands of Cherokees fled to Kansas, living in desperate conditions and exacerbating tensions in the area. It also soon became evident that Southern leaders were unwilling or unable to uphold their rosy treaty promises. Annuities were rarely forthcoming. Native regiments were undermanned, undersupplied, and unprepared to guard Indian Territory. Confederate agents were scattered or distracted by military matters. Internal quarrels led to inaction in Richmond, as well as the dismissal of Pike, whom the Indians had trusted. Ross urgently reminded Jefferson Davis of his treaty responsibilities, as well as the federal threat on the Kansas border, and asked for means of self-defense. He received no response.12

Agents and military officers reported the volatility to Washington, asserting that most Native Americans under Confederate control would prefer to be aligned with the Union. But the cabinet hesitated to intervene, especially after hearing an account of Watie’s exceptional performance at the Battle of Pea Ridge, including some exaggerated rumors involving mutilated prisoners. Lincoln led the vacillation. He was under “hard pressure” from political patrons, but tried to order the creation of a “snug, sober column” to keep peace. He dispatched and recalled men in such confusing fashion, however, that officers such as General James Lane, who simultaneously served as a senator from Kansas, and General David Hunter only quarreled over rank or worked against one another. When Lincoln twice more reversed plans, Hunter refused all cooperation, and Lane openly ignored the commander in chief’s orders, complaining he had been publicly humiliated by that “d—d liar, demagogue, and scoundrel” in the White House. Not until June 1862 was a Union force finally dispatched to the area; and it was July before federal troops were able to reestablish their authority.13

Meanwhile the plight of the refugees had become frightful. An army surgeon reported seeing hundreds lying naked in the snow, without blankets or food. According to one report, seven hundred Creeks and Cherokees froze to death in a few days. William Coffin, the superintendent of Indian affairs for Kansas, begged for assistance: the “destitution, misery, and suffering amongst them,” he wrote, “is beyond the power of my pen to portray.” The fate of Ross and his followers became yet more precarious as they fell victim to both armies in the to-and-fro contest. In late summer 1862 Chief Ross was “arrested” and removed to the protection of the Union line, accompanied by his family and the Cherokee archives. Many of his followers also defected, assured by federal officers that they would be given immunity as long as they ceased all guerrilla activities and promoted peace. A large number not only laid down their Confederate arms but joined the Union forces.14

In Kansas, Ross claimed that most Cherokee had never really abandoned their loyalty to the United States. The treaties signed with the Confederate government, he argued, were only a desperate response to dire circumstances. Most who met him took him at his word. They advised Ross to discuss his case in Washington, arming him with supportive letters of introduction to the president. General James Blunt, appointed commander of the Department of Kansas after the Lane-Hunter debacle, represented Ross as “a man of candor and frankness upon whose representations you can rely.” He also backed Ross’s assertion that he had aligned with the South only after the United States failed to meet its treaty obligations. Mark Delahay, a Republican collaborator, reminded Lincoln that despite their brief flirtation with the rebels, Cherokee warriors would be valuable to the Union cause. Indeed, maintained Delahay, the volatility along the border and the refugee problem could not be solved without their help.15

But Lincoln already knew about the situation and was unconvinced. When he raised the issue with the cabinet, he advocated a hard policy of invading Indian Territory with a force of white and black soldiers and repossessing it from the tribes. Assistant Secretary of the Interior John P. Usher, whose portfolio included Indian affairs, objected. He proposed that it would be better to deal “indulgently with deluded natives,” win their goodwill, and at the same time impress them with the immense power of the federal government. Most other secretaries concurred, and the President reluctantly dropped his proposed offensive against the Cherokee.16

When John Ross crossed the White House vestibule on September 11, 1862, Lincoln met him coolly. He was still uncertain about the chief’s sincerity, and leery of making concessions to a man who shifted his allegiance under pressure. The President’s skepticism is interesting, for he was himself struggling to steer his ship through a crisis, and relying on practical expedients to keep it afloat. If anyone understood the difficulties of clinging to ideals in the midst of a clamorous civil war (or to the legal instruments that protected them), he did. Just a few weeks before, he had succinctly expressed his belief that absolutist principles were subordinate to the larger good of national survival. If he could save the Union by abolishing slavery, he would do it, Lincoln had told the New York Tribune; but if it could only be saved by retaining the institution he would do that instead—whichever worked best. By the time of Ross’s interview, the President had circumvented the law on issues ranging from increasing the size of the Army to spending unappropriated Treasury funds, and was only days away from reversing his oft repeated pledge not to meddle with slavery in states where it already existed. But the similarity of Ross’s circumstances eluded Lincoln, and he dismissed the chief with a lawyerly request that he put his thoughts in writing.17

Ross wrote at length, reciting the pressures that had pushed him toward the Confederacy, stressing that at the first opportunity his nation had again “rallied spontaneously” to the Union cause. Complete restoration of U.S.-Cherokee relations had been thwarted only by the untimely withdrawal of federal troops from Indian Territory, he noted, which left his people prey to rebel depredations. He asked for the reinstatement of exiting treaties, as well as the safeguards they promised, and for a proclamation listing assurances he said Lincoln had given during their interview. Lincoln answered noncommittally that he had decided nothing definite, but would look into the matter. If the Cherokee remained loyal, the President would provide “all the protection which can be given them consistently with the duty of the government to the whole country.”18

In the following weeks, Ross met Lincoln again and talked several times with William P. Dole, the capable commissioner of Indian affairs. Dole was persuaded enough of Ross’s position that he publicly admitted the administration had erred—first by creating uncertainty over slavery’s future, and then by abandoning Indian Territory. He allowed that in the absence of federal support, it was understandable the tribes had “quietly submitted to the condition of affairs by which they were surrounded.” In addition, Ross petitioned Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to make Indian Territory a military district, with sufficient troops to protect life and property, or to allow loyal Cherokee to form a “Home Guard” under Union auspices. Lincoln also followed up, querying Interior Secretary Caleb B. Smith about Cherokee relations and proposing that a unit under the command of General Samuel Curtis be used to guard Indian Territory. But in putting the plan into force, Lincoln was still hesitant, and he requested Curtis’s opinion rather than sending an order. Curtis replied that the troops “available” in the southwest were too scanty to spare; in any case, he doubted that occupying the area would be of much use. Once again, no action was taken to relieve the tribes.19

Meanwhile, in Ross’s absence from the region, Stand Watie was made principal Cherokee chief, and the territory became a pawn of rival groups. Already “despoiled” by Confederate soldiers (some of them Watie’s men), the tribes now faced equally unscrupulous federals. General Blunt’s intention to return the refugees to their homes seemed well meaning, but, in reality, his own men were robbing them, and the territory was increasingly dangerous. “These Vandals have entered our houses, insulted the weak and unprotected—and stripped them of every last thing they possess,” wrote an eyewitness. Government agents reportedly joined in the plunder, and the plight of the starving refugees became increasingly horrific. By year’s end, wrote an observer, the camps had become “literally a graveyard.” The Cherokee wanted to continue supporting the Union and to return to their self-sufficient ways, a blue-clad soldier observed, but the “cruel and disappointing” lack of assistance was undermining their loyalty.20

II

John Ross was not the first Native American Lincoln met at the White House, nor the last. Chiefs often came to Washington, either on their own volition or at the behest of agents or politicians. Usually one party or other hoped to gain concessions. The government wanted the cessation of hostilities, treaty amendments, or the acquisition of more land, while tribal leaders petitioned for the fulfillment of agreements already in effect, larger annuities, or an end to the epidemic of swindling. Dressed in traditional finery, the chiefs inevitably drew attention, sometimes inspiring artists and writers to record their stories and appearance. Not everyone was pleased with the commotion these visits aroused. Many tribal leaders did not particularly enjoy being gaped at, and whites who felt they had suffered at Native hands thought the notoriety unseemly. “The Red Lake Indians create a sensation here as a deputation of Indians always do,” complained Minnesota editor Jane Swisshelm in 1864. “The popular sympathy of Washington is in favor of Red men and Rebels, and individuals of either class are apt to be feted.”21

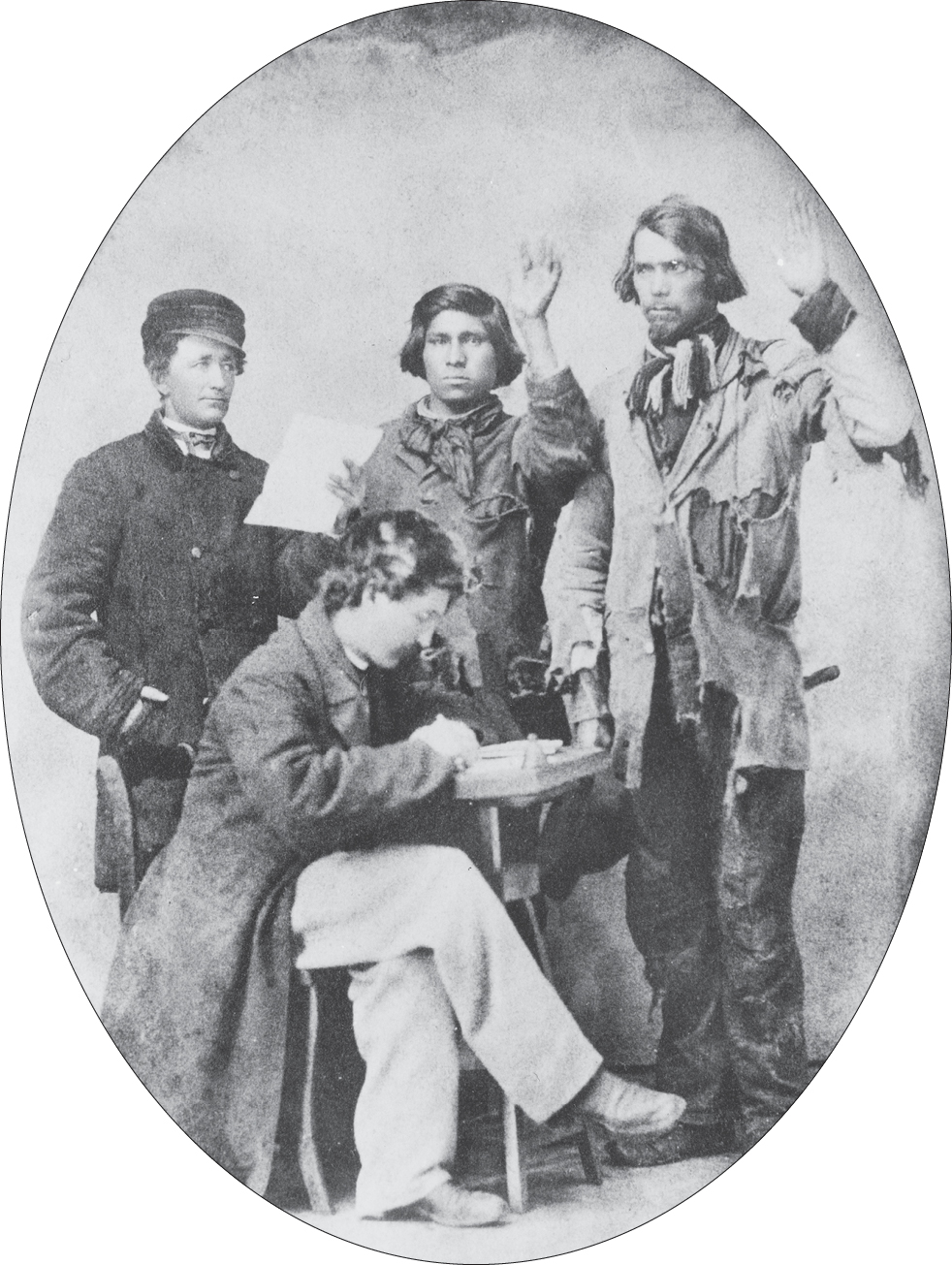

Native Americans on the steps of the White House, photograph, c. 1861–65

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

The Lincolns began receiving Native American representatives just weeks after their first inauguration. Some of these visits seem to have been social—Mary Lincoln invited a Seneca woman to sing at a reception in early April 1861 and accepted invitations to other concerts of indigenous music. The President amused three Potawatomi delegates that same month, when he tried out the few Native words he knew, then addressed them in childlike English. “Where live now? When go back Iowa?” Lincoln awkwardly inquired, apparently oblivious to the Potawatomi spokesman’s “very exceptional” English. Chippewa, Osage, Delaware, Sioux, and Winnebago chiefs entered the Executive Mansion, as well as representatives of western tribes. Some, like John Ross, stayed in Washington for long periods, conducting in-depth negotiations.22

Southern Plains delegation at the White House, photograph, March 27, 1863. [In the front row left to right: War Bonnet, Standing Water, Lean Bear, and Yellow Buffalo. In the center at the back, J. G. Nicolay, President Lincoln’s private secretary, and on the extreme right, Mary Todd Lincoln.]

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

The most heralded White House meeting took place on March 27, 1863. More than a dozen chiefs were present, representing the Cheyenne, Kiowa, Arapaho, Comanche, and Apache peoples, whose hunting grounds covered vast areas of the southwestern plains. The visit had a formal agenda—to press the chiefs to amend treaties from the early 1850s that had allowed the United States to build roads, depots, and military posts guarding emigrant routes. With the discovery of gold and silver in Colorado and Nevada years later, those routes had become increasingly crowded, and the government wanted more Indian land. But the treaties had already squeezed the tribes onto ever diminishing tracts, a provision that was misunderstood by some chiefs, and unacceptable to others. The Cheyenne and Arapaho, who had already adapted to a buffalo-centered existence after being pushed out of the eastern woodlands, found the idea of living in a constricted space with limited grassland particularly repugnant. Claiming that they had been bribed to sign the original treaties, several chiefs simply refused to honor them, or to sign further documents. Others actively resisted abandoning their hunting culture. As white settlement mounted, Native American frustration also rose, and hostilities increased. Settlers blamed the Indians for loss of livestock and for terrifying attacks on their forts and cabins, while the tribesmen accused the newcomers of stealing ponies, deflowering their women, spreading disease, and encouraging drunkenness. By bringing the chiefs to Washington, the Lincoln administration hoped to win new agreements that would place the Indians on reserves that were smaller and farther from whites, and limit their movements by controlling where they could obtain goods and receive annuities.23

The business at hand was serious and the tribal leaders took it seriously, arriving in ceremonial attire. Photographs taken at the encounter show them wearing supple garments of buckskin or cloth, the sleeves and trousers intricately embroidered with beads. Several chiefs carried a staff of office, decorated with fur or trophies; a few sported feather headdresses and some wore soft hats, fastened with memorial pins. No bare-breasted “savages” were present, and, despite later reports, their bodies were unpainted. A journalist for the Washington Morning Chronicle saw “hard and cruel lines in their faces,” but noted they were “evidently men of intelligence and force of character.” The solemnity of the occasion was undercut by the presence of a large crowd, invited by the Lincolns to view the proceedings. Diplomats from three continents had been summoned to the East Room, as well as society grandees, cabinet officials, and newspapermen. The First Lady joined the gathering, as did Miss Kate Chase, the treasury secretary’s fashionable daughter. “I am in a tremendous hurry as we are all going to the President’s in ½ an hour to see the wild Indians,” Benjamin French, the commissioner of buildings, wrote excitedly. For many invitees this was a rare moment. Native Americans had been uncommon on the Eastern Seaboard for more than half a century; and some knew of them only through the romantic literature of James Fenimore Cooper. Others had formed their opinions from more lurid tales of marauding bands on the frontier.24

As the chiefs entered the room, the crowd pressed them so tightly that the throng had to be physically held back. Nonetheless, it was reported, the visitors “maintained the dignity or stolidity of aspect characteristic of ‘the stoics of the woods’” and appeared unimpressed by the trappings of the White House. They were seated on the floor along one side of the room, where the guests could better see them. Commissioner Dole introduced the chiefs one by one to the President: Lean Bear, War Bonnet, and Standing Water of the Colorado Cheyenne; Yellow Buffalo, Lone Wolf, Yellow Wolf, White Bull, and Little Heart from the Kiowa tribe; Arapaho chiefs Spotted Wolf and Nevah; Comanche leaders Pricked Forehead and Ten Bears; Poor Bear of the Apaches; and a Caddo principal chief called Jacob. While the crowd jostled rudely for the best view, Lincoln invited the chiefs to speak. Just what they said and how much they understood of the meeting is unclear, for only one interpreter had been provided for men speaking several different dialects. (Indeed, one witness later noted that the translator interpreted every speech identically.) The crowd tittered when Lean Bear, nervous before an audience, had to prop himself against a chair; Lincoln checked their laughter, but himself joined in when another earnest speech was translated as a petition for “many sausages.” One tribal leader candidly remarked that his only request was that the “Great Father” send them home as soon as possible.25

Lincoln then addressed the group, apparently extemporaneously. His speech pointed up the differences between white and red men: the “big wigwams” of the whites; their greater population; their evident prosperity. He advised the chiefs that this was because Europeans cultivated the land, living on agricultural products rather than wild game. The President avoided prescribing a course for the Indians but admitted he saw no viable path for them but to adopt the ways of white men. Lincoln went on to assert that a Euro-American aversion to war aided their success: “we are not so much disposed to fight and kill one another as our red brethren.” This was a rather astonishing statement, coming as it did after decades of foreign and Indian wars, and in the midst of brutal civil strife. There were settlers who broke treaties, or whose actions were reprehensible, continued Lincoln, but the chiefs would understand that “it is not always possible for any father to have his children do precisely as he wishes them to do.” The lecture concluded with a geography lesson from Joseph Henry of the Smithsonian Institution that explained the formation of the American continent, and talked of “canoes shoved by steam” that traveled around the globe. One observer thought Lincoln had admirably adapted “his ideas, his images, and his diction” to those whom he addressed. Others in the crowd found the message patronizing and suggested that “he was blending with the advice a little chaffing.”26

Lincoln ended the ceremony by giving each chief a peace medal to wear on his breast and an American flag. These, he explained, were more than mementos; they were a pledge of federal protection. As he left the room, the President dryly quipped to a reporter that it was the first delegation he had recently met “which did not volunteer some advice about the conduct of the war.” After he left, a photo shoot was held in the conservatory, where guests, including Lincoln’s young secretaries, vied for a spot in the groupings. John Nicolay later had his photograph made into a stereopticon show, and John Hay dined out on witty stories of the visit. The Indians observed it all “with becoming gravity.”27

It was the most succinct statement of cultural values and Indian policy that Lincoln would ever make, and an ominous one for the Native Americans. But the sobering message was lost in the White House spectacle, smacking as it did of Phineas T. Barnum’s circus—indeed, literally so. The great showman heard of the visit, and paid “a pretty liberal outlay of money” to bring the chiefs to New York. Such excursions were not unheard of—chiefs were often taken to major cities to see and be seen, as well as to be impressed with the scale of the white man’s empire. When an Indian agent told Barnum the chiefs would go to his American Museum only if visitors appeared to be paying homage, Barnum set up an elaborate ruse to convince them that the customers were not there to gawk, but to honor them. Barnum was a longtime Indian hater who felt no hesitation about exhibiting Native American leaders alongside armless women and two-headed monkeys, but he gave his display a further twist. While the chiefs sat onstage, without benefit of translation, Barnum described their characteristics in sensational terms. Patting them familiarly and smiling unctuously, he led them to believe he was singing their praises. He had a particular dislike for the Kiowa chieftain Yellow Buffalo, who he believed was responsible for the death of a white family. “This little Indian, ladies and gentlemen is Yellow Bear,” Barnum began his deprecating monologue, starting with a misnomer, who “has tortured to death poor, unprotected women, murdered their husbands, brained their helpless little ones; and he would gladly do the same to you.” Giving Yellow Buffalo a stroke on the hand, he had the chief bow to the audience, as if to admit the ringmaster’s words were just. At length the chiefs discovered the game and, highly offended that people had been charged money to insult them, refused to appear again. Their “wild, flashing eyes were anything but agreeable,” Barnum later recalled. “Indeed, I hardly felt safe in their presence.”28

The Native American spectacles continued throughout the Lincoln years, to the embarrassment of some invitees. But most viewed the display as P. T. Barnum did: a kind of freak show, blending “barbarian” Indian ways and picturesque artifacts. Despite their disdain and fear, Euro-Americans were fascinated by the tribes. At the White House, Nicolay collected Indian lore and studied the “simplicity & superstition” of Native spiritual beliefs, all the while publishing articles that criticized “their idleness, their filth, their savage instincts and traditions.” His conclusion was that indigenous peoples possessed “none of the beauty which the refining emotions of love, generosity, pity, or moral courage lend to . . . civilized man and woman.” Renowned scientist Louis Agassiz hoped to study this “natural man,” soliciting the War Department for the bodies of “one or two handsome fellows” who had died in federal prisons, as well as the severed heads of several others. He included a recipe for embalming fluid with his request. Hay was also eager to collect artifacts. When his compatriot Nicolay was on a western assignment, he asked for a pair of beaded slippers—if, he joked, Nicolay’s hide had not already been made into a “festive tomtom.” Lincoln too liked the feathers and the finery: he was sent a handsome pair of quillwork moccasins and slipped them on with a grin. Observing the scene, Hay asked Nicolay whether he thought the exquisite craftsmanship might persuade their boss against appointing a “peculating” man as the tribe’s agent. “I fear not, my boy,” Hay concluded. “I fear not.”29

Exactly what Lincoln’s intentions were toward Native Americans is not entirely clear. As in so many instances, his writings show ambivalence and his words do not always match his actions. Certainly, his remarks to the Plains delegation reflected the standard platitudes and paternalistic tone of the day. As the Great Father, he did not hesitate to expound the Euro-American worldview, as if to ignorant children. Nor did he envision a future when different races might respectfully share the land. “That portion of the earth’s surface which is owned and inhabited by the people of the United States, is well adapted to the home of one national family; and it is not well adapted for two or more,” the President had told Congress just a few months earlier. Yet the idea of educating, Christianizing, and settling the Indians on agricultural lands was considered enlightened at the time. Many believed that obliterating the ancient ways would not only remove the threat to white advancement but benefit Native peoples. In hoping to acculturate the Indians there was at least a small recognition of their humanity—though they were easily reduced to subhuman stereotypes when it became morally or economically convenient to do so. Some of Lincoln’s fellow Whigs had sympathized with the plight of Native Americans—notably, John Quincy Adams, who avowed that Indian policies were “among the heinous sins of this nation”—but many did so only when it was useful as a partisan tool. Lincoln’s political model, Henry Clay, for example, liked to thump Andrew Jackson for his callous removal policies, even though a few years earlier Clay had declared that the “Indians’ disappearance from the human family will be no great loss to the world.” Only rarely did whites spend enough time in Native communities to respect the cultures. Sam Houston, George Thomas, General Ethan Allen Hitchcock, and a handful of missionaries were among the very few, and, in the end, even they acquiesced to policies that corralled the tribes. The rest of the country simply thought the Indians should be exterminated.30

Lincoln’s lecture to the chiefs expressed several of his strongest convictions. He had long believed that tilling the soil was an indispensable route to economic independence, for poor whites as well as people of color. He enthusiastically supported the Homestead Act, which he thought would give “every man . . . the means and opportunity of benefitting his condition.” He also believed in the redeeming value of work—a pointed message for Native peoples, whose hunting culture was widely considered a lazy man’s life. “Useless labour” was the same as idleness, Lincoln once commented; and “idleness would speedily result in universal ruin.” Upward mobility, self-definition, and the value of a helping governmental hand were themes Lincoln reiterated many times. He saw successful citizens as “miners” who exploited resources for public benefit and criticized the “indians and Mexican greasers” who had “trodden upon and overlooked” the continent’s mineral riches. To Lincoln’s mind, using technological knowledge to tame the daunting expanse of North America meant progress and prosperity.

In addition, the power of education was almost a credo with him: a sacred obligation to harness the wisdom of the past and apply it to the future. His personal story was a testament to America’s promise of a fluid society: if he believed in anything, it was the ability to rise through individual will and the application of knowledge. “Degraded” was the word he used to describe cultures that did not possess written records or depended on oral tradition to transmit knowledge—an intriguing statement from a man who made many of his most salient points as a raconteur. Adaptability was another of Lincoln’s keys to success on the ever expanding geographical and intellectual frontiers of American society. Indian adoption of white ways was simply one more sign of social mobility. For Native American culture to remain static was to resist the dynamic nature of the time; it was contrary not only to enterprise and advancement but to the moral worth they embodied.31

Many of these assertions stemmed from Whig and Republican ideas about the nature of “progress” and the unstoppable trajectory of the country’s development. Americans’ abiding belief in the perfectibility of man was also at play here. Lincoln’s call for Indians to “adapt or die” reflected his faith in the power of opportunity—a power he believed was embodied in the Declaration of Independence. Lincoln focused attention on this revered document in the years leading to his presidential election, reinterpreting it in many ways. In the promise of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” he saw freedom of movement, the latitude to invent and reinvent oneself, and the chance to rise through ambition and energy. It was this that led him to defend the slave’s right to “eat the bread without the leave of anybody else, which his own hand earns,” and to admit (at least tacitly) that the guarantees expressed in the Declaration should be extended beyond the realm of white males. “As a nation, we began by declaring that ‘all men are created equal.’ We now practically read it ‘all men are created equal, except negroes,’” he told his friend Joshua Speed, adding that he feared the nativist Know-Nothing party would like it to read “‘all men are created equal, except negroes and foreigners and catholics.’” Lincoln never specifically included Native Americans in mankind’s inalienable rights, but he hinted at it when Stephen Douglas goaded him on citizenship for “negroes, Indians and other inferior races” during the last of their famous debates. The leaders of the American Revolution, Lincoln retorted, “intended to include all men. . . . They meant to set up a standard maxim for free society . . . [for] all people, of all colors, everywhere.”32

Yet, significantly, he never grappled with the contradiction between his ethnocentric vision of the Indians’ future and the right of self-determination. For Lincoln, there was no reason Native Americans should not flourish, as long as they did so on white men’s terms. The liberty to pursue a destiny different from the invaders of their continent, and to fashion a way of life unique to themselves, was not the bargain that was offered. What was offered was that they abandon any habit that seemed offensive or strange to whites, that they accept limitations on their movements, and that the value of land be viewed from the settlers’ perspective. But the Indians were reluctant to abandon their traditions and worldview, which were fundamentally at odds with Lincoln’s scenario. It is difficult to generalize, for nearly six hundred distinct cultures existed among Native peoples, but much of their belief embraced a concept of inhabiting, but not disrupting the land; a delicate balance between harvesting Earth’s resources and leaving them undisturbed; and a commitment to ensuring bounty for the next generation. Although they could, and did, manipulate nature, they were not convinced that bending the landscape to man’s will was either ethical or profitable.

For many tribes, the land itself was sacred, imbued with spiritual qualities. As the home and resting place of their ancestors, it was filled with a power that was to be respected in its own right. Acquisition was not the route to status or well-being in these societies, nor did they prize individual gain over collective good. Lincoln’s concept of civilization as a community of diligent miners, exploiting nature for personal benefit, was fundamentally at odds with Native credos, as was his belief in the value of private land ownership and settled communities. In fact, farming was considered an inferior profession by many Native Americans, and toiling at any hard labor was thought demeaning. Alexis de Tocqueville observed in the early 1830s that Indians compared “the farmer to the cow who plows a furrow, and in each of our arts he perceives nothing but the work of slaves.” That Indians lived on far rawer terms than many of their white counterparts is clear. That they could be ruthless is also evident: brutalities committed by Native Americans rivaled all the atrocities visited in return by whites. But their resistance to European ways, overcome in most cases only by violence against them, also bespoke pride, as well as contentment with their heritage and lifestyle. “We do not own this,” the Lakota said of the grand American expanses, “we only borrow it from our children.”33

The cultural friction was intensified by a sliding scale of expectations on the part of the whites. Whatever their loftily stated goals, that scale was pegged to self-interest. The original idea of “removing” tribes from European settlements had foreseen them as permanent residents west of the Mississippi River, but by the time Lincoln entered office, whites coveted that land too and intended to cajole, chase, or cheat the Indians to obtain it. This included the rich territory owned by John Ross’s tribe, which had—strikingly—lived up to every expectation of “civilization” set out in Lincoln’s culturally bound dictums, including conversion to Christianity and the establishment of a written language. None of this exempted them from the insatiable hunger of industrialists, railroad speculators, and ambitious farmers, and much of the tension that led to Cherokee defection in 1861 centered around encroachments on their property. Ownership of Indian Territory was supposedly guaranteed by treaty, but Americans of all persuasions had already dismissed the idea of Indian entitlements. The word “enough” did not exist in the vocabulary of ambition.

Republicans as well as Democrats were complicit in this—as they were in placing the blame squarely on Native Americans. Indians were frequently referred to as demons who undermined development—“Satans of the forest,” “devils in the path,” “evil forces that pollute the ways of the righteous.” Yet Indians were not the worm in the democratic apple. The worm in the apple was the cankerous American tendency toward avarice, which turned opportunity into opportunism and allowed greed to be rationalized under the guise of progress. That complication—that the other side of Liberty’s coin was etched with License—riddled the whole national saga, but was particularly true in regard to Native Americans. The entire white relation to indigenous peoples was based on the presumption that might—political, financial, or firepower—made right. Lincoln cleverly reversed this in his 1860 address at the Cooper Institute (now known as The Cooper Union), avowing that “right makes might”—but with the Indians he either could not determine what was right or subordinated it to political expedient. It was telling that Native Americans, who were disbarred from legal representation, unleashed much of their violence defending themselves against encroachments on their property. Their issues were the very ones Lincoln the lawyer had fought to protect for his clients: the right not to be swindled, rightful recognition of established boundaries and legally protected lands, and freedom of movement. The similarity between American values and Indian interests never registered with the sixteenth president, or with most other white people. In the end, Lincoln’s defense of American opportunity would be distorted by the sham nobility of “progress.” But for those hungrily eyeing Indian holdings, it reflected little more than appetite.34

III

Prior to taking office, the President had had few personal encounters with Native Americans. Indians were a legendary part of the pioneer experience, but by the time of Lincoln’s birth, in 1809, most had been driven from the Ohio River Valley. The southern part of Indiana, where he spent his youth, had been home to the Iroquois, who kept it as a hunting preserve, leaving it relatively empty. The last organized Indian resistance against white encroachment in the area ended with Tecumseh’s defeat in 1813. By the time the Lincolns moved to Spencer County five years later, the local Delaware and Miami peoples had ceded their lands and moved westward.35

Although he had little direct experience with Indians, young Abraham was influenced by the vivid tales he heard from his family. Most impressive was a grisly story of his grandfather’s death at the hand of an Indian, and the near kidnapping of his father. Accounts differ, but many sources indicate that shortly after moving to Kentucky the elder Lincoln—also named Abraham—was killed while working in the fields, and six-year-old Thomas, playing nearby, was snatched up by the assailant. The eldest son, Mordecai, watching the scene from their house, shot the murderer, who dropped Thomas. In recounting the story, Lincoln emphasized that his grandfather’s death had not been in a battle or fair fight but was the result of Native American “stealth.” There were other tales as well. One involved his mother’s dearest girlhood friend, who was taken captive when a raiding party killed her father but was later miraculously released. Another story told how a family living near the Lincolns in Spencer County, Indiana, had been heartlessly butchered by the last few Shawnees in the area—and vividly described the rough justice a vigilante group meted out to the Native men afterward. Both accounts were true. Later in life Lincoln would also hear his wife’s fund of Indian lore, including the killing of Mary Todd’s great-uncle during a battle with Miami and Chickasaw warriors, and how another relative was forced to run a Shawnee gauntlet and nearly lost his scalp.36

Such stories fed the sharp nighttime fear of the wilderness. Lincoln remembered the warnings of Indian treachery as vividly as he recalled the scream of the panther. Exaggerated or not, the tales instilled an understanding of the high stakes of survival on the frontier, and the need to subdue “wild” men if civilization was to triumph. It was also the way myth and mistrust were spread. Herman Melville, who so often had his finger on the quixotic American pulse, expressed the power of such oral traditions in The Confidence-Man. On the frontier, Melville wrote, a father thought it best

not to mince matters . . . but to tell the boy pretty plainly what an Indian is, and what he must expect from him . . . histories of Indian lying, Indian theft, Indian double-dealing, Indian fraud and perfidy, Indian want of conscience, Indian bloodthirstiness, Indian diabolism. . . . The instinct of antipathy against an Indian grows in the backwoodsman with the sense of good and bad, right and wrong.37

The elder Abraham Lincoln’s death was, in fact, more than just an adventure story: his relatives believed it had signaled a downward spiral in the fortunes of the Lincoln clan. The family typified the restless pioneers of the late eighteenth century, migrating over the years from Massachusetts to Pennsylvania, and then settling for a time in Virginia before making the trek into Kentucky around 1782. They seem to have been scrappy fortune seekers, eager to improve their lot, and willing to take on the wilderness challenge of wild beasts and violent men. (As a presidential candidate, Lincoln stated his family included some peace-loving Quakers, but, if so, they were ties by marriage.) In all their settlements the Lincolns owned substantial acreage and held positions of responsibility. There is also considerable evidence that some family members were slaveholders. Abraham senior possessed several thousand acres of fine Kentucky bluegrass and was instrumental in building the fort near which he was killed. He died intestate, and under Kentucky law the property was inherited by his eldest son, who built a handsome house with a Palladian window and fine woodwork, which still stands in Washington County.38

Court records indicate that that heir, Mordecai Lincoln, provided his younger brother Thomas with the opportunity to learn a trade—cabinetmaking and carpentry—and the education needed to practice it. Mordecai probably also helped his brother acquire his first property, for which Thomas paid cash. Official documents suggest that Thomas, like other Lincolns, was a respected member of the community: a landowner and stock raiser, with enough income to hold a memorable wedding, pay his debts, and make loans to his neighbors. His son, however, grew up with the impression that Thomas had been disadvantaged, becoming a “wandering, laboring boy” who attained no more education than to “bungling sign his name.” Thomas’s signature in court records and other documents belies this, showing a clear, practiced hand, until late in life. Neighbors noted that Thomas Lincoln’s cabinetry was “sound as a trout,” and the pieces left to us are marked by carvings, inlays, and fine proportions, indicating mathematical expertise and an appreciation of artistic trends. By Lincoln’s boyhood, his father may have already suffered the eye injury that would undermine his ambition, and which perhaps accounts for the “bungled” writing. The sixteenth president’s knowledge of family history was not perfect—the date he gives for his grandfather’s murder is in error, as is the Quaker lineage. Perhaps he was simply misinformed. But Lincoln showed a consistent tendency to overstate the level of his father’s poverty, and at times seems even to have scorned his own background. It may have been a matter of good politics—grassroots origins appealed to his audiences, as they do to contemporary voters. In his earliest known political address, Lincoln described himself as being from the “most humble walks of life,” just as he later attached a fictional impoverished background to Henry Clay for the benefit of a Whig audience.39

Still, despite exaggeration, there is no question that Abraham Lincoln was raised on the frontier, in log houses that seem impossibly cramped to present-day eyes, and that as a boy he wore hide breeches, which shrank to his calves as they met sun and rain and his own phenomenal growth. Lincoln’s aspirations also outgrew his environment. Southern Indiana was not a place noted for its ambition. Had settlers followed the Iroquois example, they would have shunned its poor soil, unhealthy situation, and limited potential. Lincoln’s father believed he was bettering himself by moving across the Ohio to an area free from the competition of skilled slaves, and surveyed in a more regulated manner. (In Kentucky he had lost a series of property suits because of the archaic landowning patterns inherited from Virginia law.) But Thomas seems also to have made some poor decisions in Indiana—for example, following the advice of his kin to settle in a dense forest, difficult to cultivate, rather than in a town that could support his trade. There were good decisions as well, notably marrying two supportive women and establishing a community reputation for decency, generosity, and side-splitting storytelling. Thomas Lincoln was the man called on to settle disputes at the Little Pigeon Creek Baptist Church, chosen to serve on the school committee, and always willing to take out-of-luck relatives into his modest home. He was certainly not “shiftless” or “poor white trash,” as some have claimed. He was a landholder and possessed the qualities necessary for success on the frontier: optimism, physical strength, and resilience.40

But the neighborhood Thomas Lincoln chose was far from markets or cultural centers and offered little inspiration for betterment. Those studying the region have found it was a highly egalitarian society, where landownership was the sole measure of status. There was no strong impetus to acquire worldly goods or compete with neighbors. The settlers were not lazy or improvident, but neither were they drawn by the lure of high wages or opportunities for profit. A cousin who came to live with the Lincolns remarked that the family was “like the other people in that country. None of them worked to get ahead. They wasn’t no market for nothing unless you took it across two or three states.” Another relative reinforced the image of Thomas Lincoln as a “man who took the world Easy—did not possess much Envy. He never thought that gold was God.” When in 1830 Thomas Lincoln left Indiana for Illinois, he was evidently able to sell off hundreds of bushels of corn and scores of hogs—a far cry from subsistence farming. Still, his land dealings lost him money, and he was never able to retrieve the promise of his more prosperous ancestors. To his mind, the trouble had all started with the Indians.41

Some have portrayed Thomas Lincoln as a petty household tyrant, lording over his talented son like a slave driver, and a few reminiscences do paint him in that fashion. The majority, however, speak of him as did cousin John Hanks: “he was a good quiet citizen, moral habits, had a good sound judgement, a kind Husband and Father Even and good disposition was lively and cherfull.” Thomas seems to have been a typical father of the era, schooled in eighteenth-century notions of the patriarchal family. Life on the frontier was difficult, and most men believed their role was to ensure survival and instill habits that would enable their children to face hardship. Sons and daughters were expected to bow to their parents’ wishes and contribute to the economic welfare of the family. This was serious business, and strong words and occasional whippings would have been normal in that rough-and-ready society. The idea of the household head as a companionable guide through life’s vicissitudes, or as the indulgent spoiler of a child-centered family—the “spare the rod” style favored by Abraham Lincoln with his own unruly boys—would not come into vogue for several decades, when middle-class ease allowed such indulgence. Lincoln himself denied feeling he was in bondage—but neither did he want to duplicate his father’s life. This too seems normal: that a sixteen-year-old chafed under parental authority and longed to pocket his own earnings is hardly revelatory. From Thomas Lincoln’s perspective, his son, no matter how talented, was not shaping up to be of much assistance on the farm, or to help him in old age—important sociological considerations in that time and place. Abe was apt to drop chores to study a book; and he was also something of a smart aleck, correcting his less educated father in front of others and even contradicting visitors. One kinsman recalled that “the worst trouble with Abe was when people was talking if they said something that wasn’t right Abe would up & tell them so. Uncle Tom had a hard time to break him of this.” There may have also been competition between father and son, both of whom were powerfully built and relished an appreciative audience. It is easy to imagine Thomas’s annoyance when he “was telling how any thing happened and if he didnt get it just right or left out anything, Abe would but[t] in right there and correct it.” According to several stories, Abe also challenged his teachers, and finally dropped out of his catch-as-catch-can schooling because he felt he had surpassed the master—which he may have done. Thomas still pushed him to learn “cipherin”—which his son later ridiculed—because he hoped to set the boy up in his own craft of cabinetmaking. Evidently Abe showed no interest in the trade; though there are two surviving pieces of furniture said to have been made by him.42

Later in life, Abraham showed Thomas little of the respect generally considered due the older generation. He did not assist on the farm, though his father was lame and blind, and offered only meager financial assistance, even with his law practice flourishing. As an older man, Thomas Lincoln expressed modest pride and affection for his son, despite their spotty interaction. Stories of Lincoln’s refusal to visit his father’s deathbed in 1851 are exaggerated, however. He had come quickly the previous year, at some expense and difficulty, when he received a letter advising that Thomas was dying and crying for his son in a manner “truly Heart Rendering.” But his father recovered. At the time of Thomas’s final illness, Mary Todd Lincoln was also unwell; in addition, it may have seemed just another false alarm. Unfortunately, the farewell letter penned by Abraham is quite callously worded. There is little to indicate whether Lincoln resented his parents or was embarrassed by them, or whether he only wanted to retreat to his self-created world. One thing, however, was certain: he did not want to continue the downward slide that had begun with an Indian attack on his namesake.43

Lincoln’s most direct Indian experience came in his early twenties, when he joined the militia to fight against Black Hawk (Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak), the Sauk leader. The Black Hawk War was the culmination of a decades-long misunderstanding between the tribes and ambitious frontiersmen in the Old Northwest. The Sauk and Fox, along with their neighbors the Winnebago and Miami, had been pushed ever westward, ultimately agreeing in 1804 to cede their homeland east of the Mississippi and move across the river. They had been residents of the area for some eight thousand years, subsisting much as the Lincolns and their neighbors did, by a combination of corn farming and hunting. According to some accounts, in the early 1800s they were so successful in the fur trade that they sold up to $60,000 worth of pelts annually. Sauk and Fox territory also included a productive lead mine, which Indians as well as whites valued. The treaty negotiation was tense and murky, with the usual difficulties of translation and cultural interpretation, which contributed to misunderstanding about boundaries, as well as the land’s use after its transfer. Article 7 stated that as long as the tracts remained property of the United States “the said tribes shall enjoy the privilege of living and hunting upon them.” Chiefs who agreed to the sale believed this meant that they would have perpetual use of the land, which included their ancestral burying grounds and other hallowed places.44

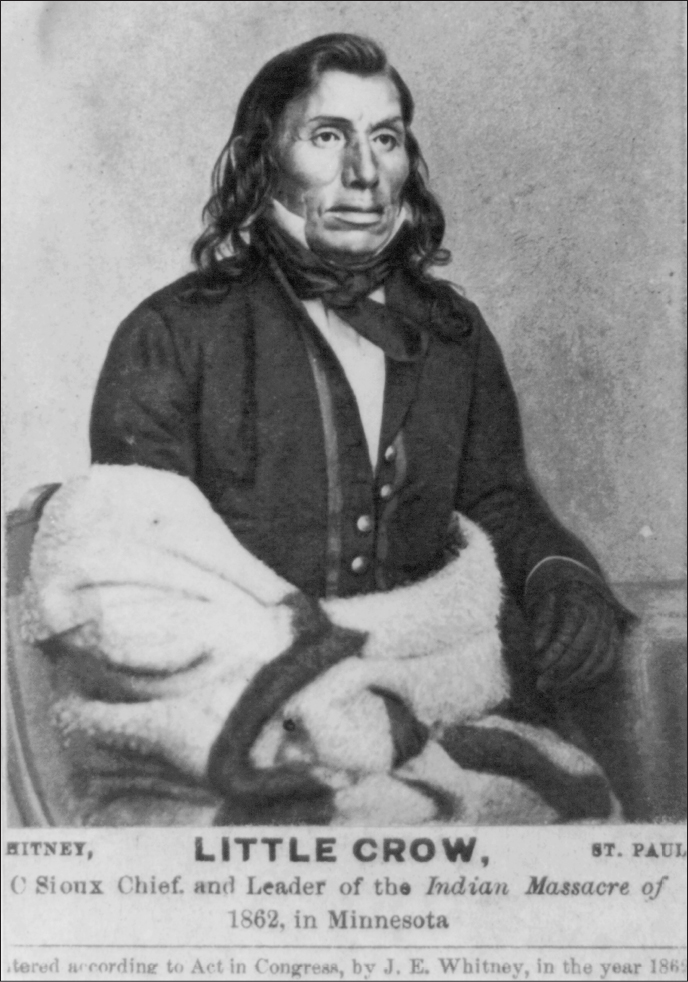

The concept of selling land itself was foreign to the Sauk and Fox culture. Black Hawk stated this clearly the following year: “My reason teaches me that land cannot be sold. The Great Spirit gave it to his children to live upon, and cultivate . . . and so long as they occupy and cultivate it, they have the right to the soil. . . . Nothing can be sold but such things as can be carried away.” Moreover, the documents had little meaning for the chiefs. They were unable to read them to start with; but, in any case, paper agreements were not part of the Sauk tradition of honor. When Edmund P. Gaines, the general in charge of Indian relations for that region, spoke with Quash-ma-quilly (Jumping Fish) about the treaty, the Sauk spokesman said he was told his people had been released from the arrangement. Asked for legal proof of this, he replied: “I am a red skin & do not use paper at a talk, but my words are in my heart, & I do not forget what has been said.”45

The federal government saw it differently. Under pressure from settlers who coveted the mines and fertile river lands, they began selling the property in 1829. For a time the tribes coexisted with whites in uneasy proximity. The pioneers became increasingly anxious, however, as frictions between the Sauk and Fox and their rivals, the Sioux, filled the night air with war cries, making movement dangerous. One local scout overheard Black Hawk warning against the loss of ancestral forests, as well as complaining that costly government goods were being shipped to the Sioux. “Shall the treasures of the pale-faces reach their destination?” the scout heard Black Hawk cry. (“A fierce and thrilling shout” was the only answer to his question.) In 1831 a settler remarked that tensions were not just setting nerves on edge, but retarding emigration. Rumors of an Indian war, he noted, excited “as much dread among the frontier settlers, as does the howling of wolves among sheep.”46

Over the next year the unrest grew, as Black Hawk moved many hundreds of Native families to an area around Rock River, not far from the lead mines. The sixty-five-year-old warrior was not strictly a chief—indeed, many of his own tribe saw him as a chronic malcontent and troublemaker. Keokuk, head of the Sauk, a shrewd and pragmatic man, was among those who tried to dissuade Black Hawk. But the Hawk and his followers were heavily influenced by a spiritual leader called The Prophet, who believed that the purity of native traditions needed to be revived. Under his influence, the clan determined to plant corn annually on their ancient territory. Black Hawk’s motive was in many ways idealistic: even the army men sent to restrain him were impressed by his sincerity. When Black Hawk spoke of “the tie he held most dear on earth,” recorded one officer, “on . . . his fine face there was a deep-seated grief and humiliation that no one could witness unmoved.” The Sauk leader ignored official warnings to leave. Complaints from farmers began to escalate—including some from men who were themselves illegal squatters. “You cannot imagine the anoyance,” wrote one. “The citizens of some of the counties made no crops last year, & can make none this year. Business of every kind is che[cked]. . . . Horses & cattle &c &c are every day stolen and the whole country is kept in a constant state of alarm.” Black Hawk refuted the charges, vowing he had done nothing beyond peacefully growing corn on inherited lands. But when he crossed the river again in April 1832, Illinois governor John Reynolds declared it an “invasion” and called out the militia.47

Abraham Lincoln joined several thousand young men in answering the governor’s call. His motivation remains uncertain. He was an itinerant worker at the time, living far from Rock River, without property to protect. Perhaps he felt some latent vengeance for his grandfather’s death; perhaps, as a friend suggested, he was stirred to action by the local “Patriock Boys,” who had signed up to “Defend the frontier settlers . . . from the Savages tomihock and Skelping Knife.” Another acquaintance said Lincoln left the impression the campaign was largely a “holiday affair and chicken-stealing expedition.” He was mustered into the Fourth Volunteer Regiment in late April 1832.48

Lincoln’s company consisted of sixty-nine local men, a rough lot by all accounts. A traveler who saw the volunteers described them as “unkempt and unshaved, wearing shirts of dark calico”; and a fellow militiaman called the band “the hardest set of men he ever saw.” Like the others, Lincoln had no arms of his own and was issued a smoothbore flintlock rifle. Emotions ran high. Many had given up their spring plowing and hopes for a good crop to wage the war. Few had sympathy with Native concerns. “I wish some of your Presyters folks was here that was so troubled about the Indians being hurt,” one wrote, alluding to the Presbyterian reputation for compassion toward Native Americans, “they wood sing another song.” All were ready for a fight, Lincoln included. A comrade recalled that he “often expressed a desire to get into an engagement” and wondered how the hardscrabble boys would “meet Powder & Lead.”49

Lincoln was elected captain of the company, something he later remembered with pride. His selection may have been due to his physical prowess—he could beat almost everyone at racing, jumping, or wrestling, and he took on any bully who threatened his crowd. Some of the men claimed the volunteers idolized their captain and would follow him anywhere. The circumstances of the election, however, were questionable and recollections vary. The men all spoke of Lincoln without rancor, but some suggested he was “indolent and vulgar” and had been chosen to spite another candidate, or because of his reputation for laxity. Discipline was, in fact, a serious problem with all the volunteer companies. Crisp commands and orderly camps were rare. Captain Lincoln’s authority followed this pattern. Reportedly, his men responded to commands by saying “Go to the devil, sir!” or broke into whiskey barrels and drank until they were unfit to march. At times they were so rowdy that they could not be directed even to cross a fence. Lincoln was punished for his laxity, as he was for excitedly shooting off his gun without authorization. But he was far from alone in his want of authority. Another officer in the battalion reported there was no effort to drill troops, that they obeyed or disobeyed as they pleased, and sarcastically concluded: “this way men may grow grey in service without becoming soldiers.” The problems mirrored the disorganization of the campaign as a whole, which included a chronic lack of coordination between the untrained volunteers and regular troops. Colonel Zachary Taylor, one of the senior officers, described it as simply “a tissue of blunders, miserably managed from start to finish.”50

Lincoln’s tenure as captain was short. After thirty days the conflict was largely contained and his regiment was disbanded. He apparently told his law partner that he reenlisted because he was out of work and had nothing better to do. He was again mustered in, this time by Lieutenant Robert Anderson, who would later gain fame as Fort Sumter’s commanding officer. (Anderson was one of several latter-day luminaries who took part in the 1832 war. Others included Albert Sidney Johnston, Jefferson Davis, and Winfield Scott.) In his two subsequent tours Lincoln was not reelected captain and joined the units as a private. He was initially part of Elijah Iles’s Mounted Rangers, which was formed in response to a call for horse troops that could chase the elusive Indians more effectively. When that unit also disbanded, Lincoln was attached to Captain Jacob Early’s Free Spy Company. Formed for reconnaissance work, the unit was elite and autonomous, taking orders directly from the commanding general, drawing no guard or other duties, and receiving a larger allowance of rations.51

In all this, Lincoln saw few hostile Indians and virtually no action. The campaign consisted largely of pursuing Black Hawk’s warriors around the northwest corner of Illinois, trying to block their raids on forts and settlements. At this they succeeded badly. In one instance they passed through an area where two hundred Fox lay in wait, without suspecting them; two days later they discovered to their horror that local white settlements had been burned and the terrified survivors were huddled in a stockade. Time and again they were outmaneuvered by their Native opponents, arriving too late to assist local residents. As Lincoln would later write, it was not a war “calculated to make great heroes of men engaged in it.” Due to mismanagement, the green volunteers were futilely marched long distances on the double-quick, while supply trains lagged far behind. Lincoln later recalled the absurdity of the organization, as well as the hardships, admitting that he was often hungry. It was “the quintessence of folly,” one of Lincoln’s compatriots in the Fourth Regiment reported. “No doubt Gen. Black Hawk was much amused and not a little edified in the arts military by his civilized and scientific enemies.”52

Participants remarked that it was fortunate the full chaos of their organization was not known to the Indians, or the militia might easily have been slaughtered. Lincoln was present in the aftermath of one disorderly disaster, an engagement known as Stillman’s Run, which appears to have made a lasting impression. In mid-May, Black Hawk, believing he was outnumbered and despairing of hoped-for support from the outside, apparently sent a group of three men under a white flag to negotiate with the state troops. Either missing the flag—or mistrusting its sincerity—the militia imprisoned the braves and fired on another group that approached. Outraged, Black Hawk then attacked the camp at dusk and, to his surprise, routed the much larger force with a small band. The militia had been drinking, and virtually no discipline had been maintained in the battle. It was a “disgraceful affair,” Taylor reported, with settlers fleeing in terror, and the army missing a perfect chance to force Black Hawk back across the river “without there being a gun fired.” The Sauk and Fox warriors suffered few casualties, but twelve militiamen were killed. The Fourth Regiment arrived the next morning, finding the mutilated bodies still on the field. Lincoln later gave a vivid description of the scene to a reporter, recalling the revulsion of seeing hacked and scalped men, and how the reddish early morning sun bathed everything in a bloody light. Others verified the grisly scene, describing headless corpses, and shallow graves dug with hatchets and hands, in the absence of proper equipment. Lincoln was part of that burial detail. It was, as he said, “frightful.”53

Finally, in midsummer, Black Hawk’s braves were cornered on the Wisconsin border at the Battle of Bad Axe. From start to finish the campaign had been a debacle. Begun as a protest against the duplicity of the treaty process, it ended with death and defeat for the Sauk and Fox. For the white settlers it devolved into a panic, fostering fear, economic loss, and the spread of cholera, which was brought to the area by the regular troops. Lewis Cass, the secretary of war, vowed to make an example of Black Hawk and his followers. He advocated humane treatment for the leaders—they were more valuable as hostages than dead. But the tribes had now lost their bargaining power and they were swiftly banished so far to the west that another attempt to return could never be made. The full tragedy was that the Sauk and Fox, although beset by intertribal rivalries, had made their peace with white expansion, feeling it was better to adapt than engage in endless confrontation. “I cannot be persuaded that the Indians crossed our border with any hostile intention beyond that of raising corn for their subsistence,” wrote one of the more circumspect members of the Fourth Regiment, “and whilst I freely grant that this was an infraction of the treaty of Rock Island . . . the manner in which we have attempted to repel it was as unwise and injudicious as the result has proved disastrous and inglorious.” Ironically, in many ways the shady practices and inflationary ways of the land speculators posed a greater threat to settlers than did the impoverished Indians. But the presumption of the whites, with their open disdain of Native American ways, and their insatiable taste for resources, provoked a deadly conflict where one need not have occurred.54

To the end Black Hawk believed that the land of his ancestors was worth holding and his tribe’s honor worth defending. In a dignified speech, he told his jailers he was proud to have fought those who despised him and would rest in peace for having attempted to save his nation. After a few months he was released, and, in a curious reversal of fortune, was sent on a mission to the Eastern Seaboard, along with his eldest son and The Prophet. Journalists interviewed the warrior; he sat for portraits and was paraded before “Great Father” Andrew Jackson, in much the same manner as the Plains chiefs during Lincoln’s time. Assessing the huge cities and the government’s power, Black Hawk had the last, apocalyptic word. “I see the strength of the white man,” he told a reporter. “They are many, very many. The Indians are but few. They are not cowards, they are brave. But they are few.”55

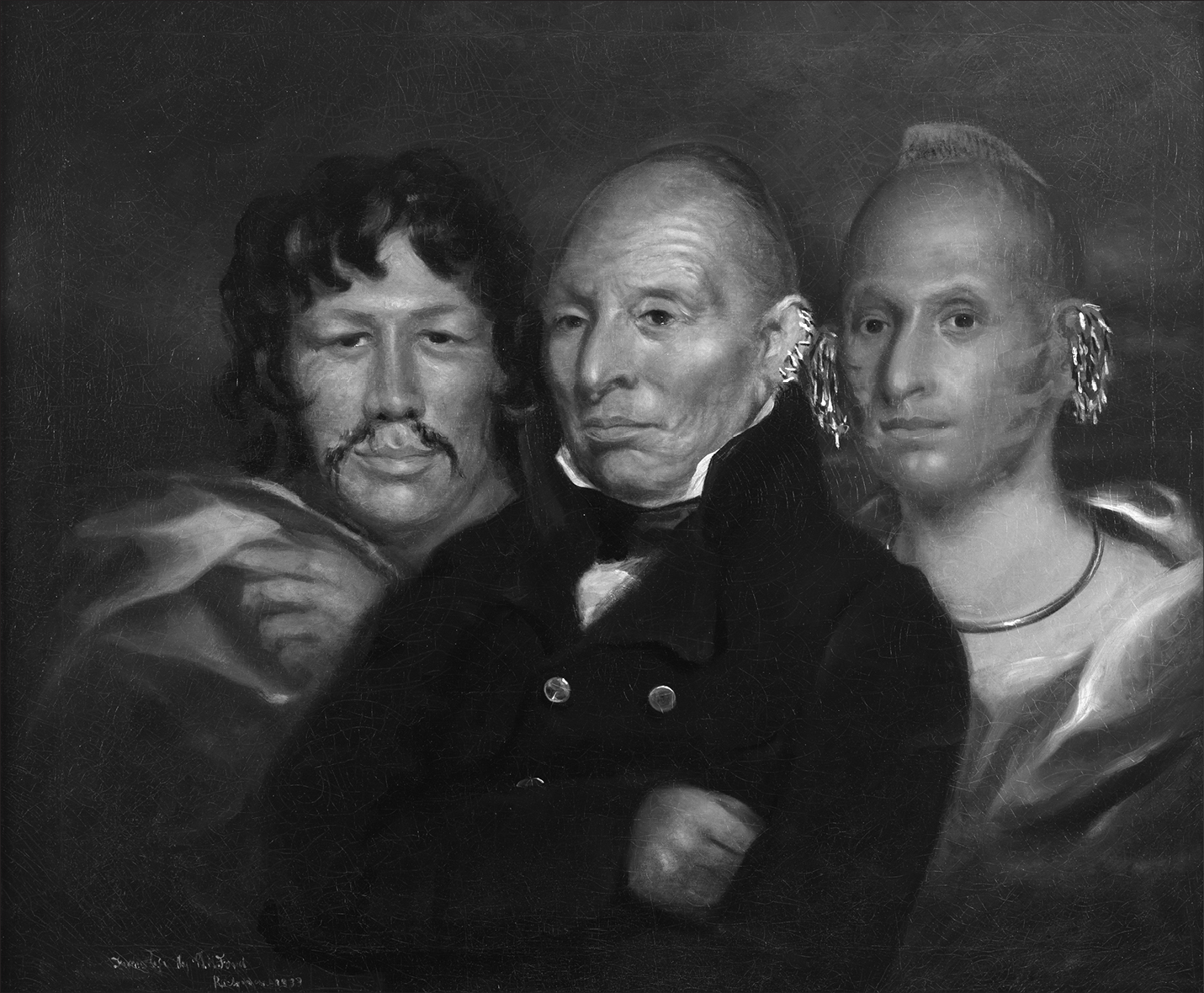

Wabokieshiek (known as The Prophet), Black Hawk in European dress, and his son Nasheaskuk, oil on canvas, by James Westhall Ford, 1833

LIBRARY OF VIRGINIA

IV

How much Abraham Lincoln reflected on his Black Hawk War experience is not known—generally he deprecated the conflict and his role in it. But the same tragic cycle of fraud, displacement, and retribution continued to spin uncontrollably during his presidency. He certainly had a similar conflict in mind when John Ross walked into his office in September 1862. An eruption of violence by the Dakota and Ojibway peoples of Minnesota a few days earlier had created panic, and a demand for government action. Ross protested that the Cherokee had nothing to do with the Minnesota crisis and that relations should be based solely on the provisions of his own treaty. Nonetheless, pressures created by the Dakota may well have influenced Lincoln’s ambivalence about the situation in Indian Territory.56

The Dakota, particularly the group known as the Santee Sioux, were a people of decided personality. Missionaries described a lively culture with a sophisticated calendar of ceremonial games, music, and dancing. The Sioux were “naturally reverent,” wrote one minister, with a language that contained no profane words. They lived a stable, semiagricultural life, growing crops and hunting buffalo and other game. They were also known for their tall, merciless braves, who were feared by other Indians as well as by whites. The common frontier sign for the tribe was a hand drawn sharply across the throat. The Dakota’s ferocious fighting ability had allowed them to dominate the upper plains for centuries, but they were rivaled by their bitter enemies the Ojibway (or Chippewa), a distinctive linguistic and cultural group. In 1851 the Dakota agreed to cede some 24 million acres of land to the United States, for the usual consideration of annuities, gifts, and protection. The new treaty confined the tribe to a narrow, 150-mile-long strip on the Minnesota River. In 1858 this treaty was amended—a hard bargain that allowed government roads and forts on the property; penalized the Dakota for destructive acts; and forbade alcohol. Neither side strictly upheld its provisions.57

With the rush of settlers to the area came increased efforts to acculturate Native Americans to white ways. Attempts to develop settled agricultural communities and instill habits of European dress and religion had some success. However, despite the efforts of sympathetic missionaries such as Episcopal bishop Henry Whipple, many Sioux felt the superimposed values were at odds both spiritually and materially with their way of life. The “civilizing” process created significant tensions between those who became farmers and leaned toward white society, and the majority of tribespeople, who wished to retain their traditional culture. As Sioux chief Big Eagle (Waŋbdí Tháŋka) explained, farming was considered women’s work, beneath the dignity of a brave; and the “cut-hairs”— those who adopted the ways of the settlers—were mistrusted. Nor were the motives of the missionaries and federal agents benign. There was obvious arrogance in assuming white ways were superior, but the government also meant to undermine traditional social structures and diminish native cohesion. “The theory, in substance, was to break up the community system among the Sioux; weaken and destroy their tribal relations; individualize them by giving each a separate home and having them subsist by industry,” admitted Thomas J. Galbraith, an inexperienced businessman whom Lincoln appointed as the Dakota agent. Internal tribal conflict grew, and several antiwhite leaders were selected for chiefdom a few months before the uprising. Control over their increasingly restless people collapsed. Attacks on farmer Indians increased, and war drums were heard in the night.58