5

HELL-CATS

Heads turned when a woman with soft eyes and brown curls entered the Executive Mansion, quiet as a small bird. It was a familiar face to most of those present, as it was to much of the world. Her work had been greatly acclaimed, setting abolitionists to beaming and slaves to cheering, but Harriet Beecher Stowe was a self-effacing woman, who maintained the credit should rightfully go to God. “I merely did his dictation,” she protested. The only person who did not recognize the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin when she arrived on December 2, 1862, was Abraham Lincoln. Senator Henry Wilson had given her a spirited introduction, but the President was not listening, and the name slipped by him.1

Stowe was not surprised. She did not like this man, who ignored her letters and looked about distractedly; moreover she was distressed over the conduct of the war, which she thought slow and indecisive. She viewed the conflict in moral terms—a war about rescuing an oppressed people from unspeakable cruelty—not constitutional niceties. A few weeks earlier, when Lincoln publicly declared he would keep every slave in bondage if that was the only way to save the Union, Stowe had shot back her own views. “My paramount object in this struggle is to set at liberty them that are bruised, and not either to save or destroy the Union,” she wrote, parodying the President’s style. “What I do in favor of the Union, I do because it helps to free the oppressed; what I forbear, I forbear because it does not help to free the oppressed.”2

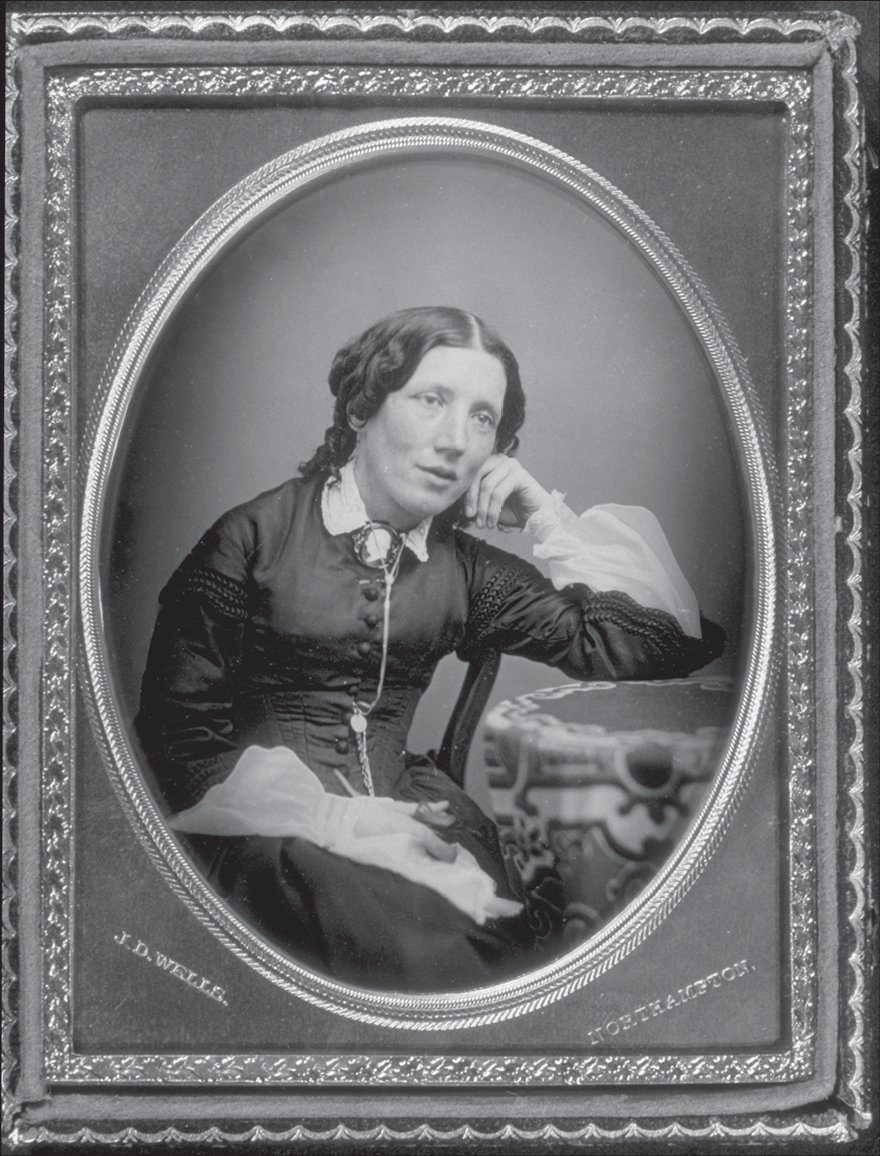

Harriet Beecher Stowe, daguerreotype by J. D. Wells, 1852

SCHLESINGER LIBRARY, HARVARD UNIVERSITY

It had been difficult for the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin to arrange this meeting. Her remarkable reputation had not been enough to secure the appointment. She had to finagle it through political contacts like Wilson and even lower herself to cajole the First Lady into an invitation, even though she viewed Mary Lincoln with some scorn. But Stowe had an object in mind and she persevered. She was anxious to know if the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation Lincoln had issued in September would prove “a reality & a substance, not a fizzle out at the little end of the horn.” She did not expect much from the President, who she feared was a “well-meaning imbecile.” But she did want one thing: reassurance that the proclamation would not come to an “impotent conclusion,” and that she could use it with her British contacts to leverage support for the Union. Whatever she expected, however, Stowe could not have imagined the scene that took place.3

For the President shambled in, “a rough scrubby—black-brown withered—dull eyed object . . . I can give you no idea of the shock.” He did nothing to open conversation after Wilson left the room, but sat by the fire, moodily staring at Stowe, her sister Isabella, and daughter Hattie.4 Although Mrs. Stowe was known as a “delightful” conversationalist, she was shy in such situations, and they remained in awkward silence until Isabella offered some small talk about “the charming open wood fire,” and “at last Mr. Lincoln—was ‘reminded of a man out west.’ . . .” Stowe matched the President’s story with one of her own and, the ice broken, finally got the guarantee she wanted. Lincoln would “stand up to his proclamation,” she reported, and would not allow the nervous border states to block the way. “I have noted the thing as a glorious expectancy!” Stowe rejoiced, and went off to drink tea with Mrs. Lincoln. The unfriendly presidential manner and the chatter of his wife (“an old goose & a gobbler at that”)—not to mention the rusty tin pans lying around the office (“much worse than those Eddie [her brother] is accustomed to feed his chickens from”)—made the whole experience seem a bit surreal. The three ladies returned to their hotel and, barely able to contain themselves, “perfectly screamed and held our sides while we relieved ourselves of the pent up laughter that had almost been the cause of death.” It was not, they noted, Lincoln’s jokes that caused their hilarity.5

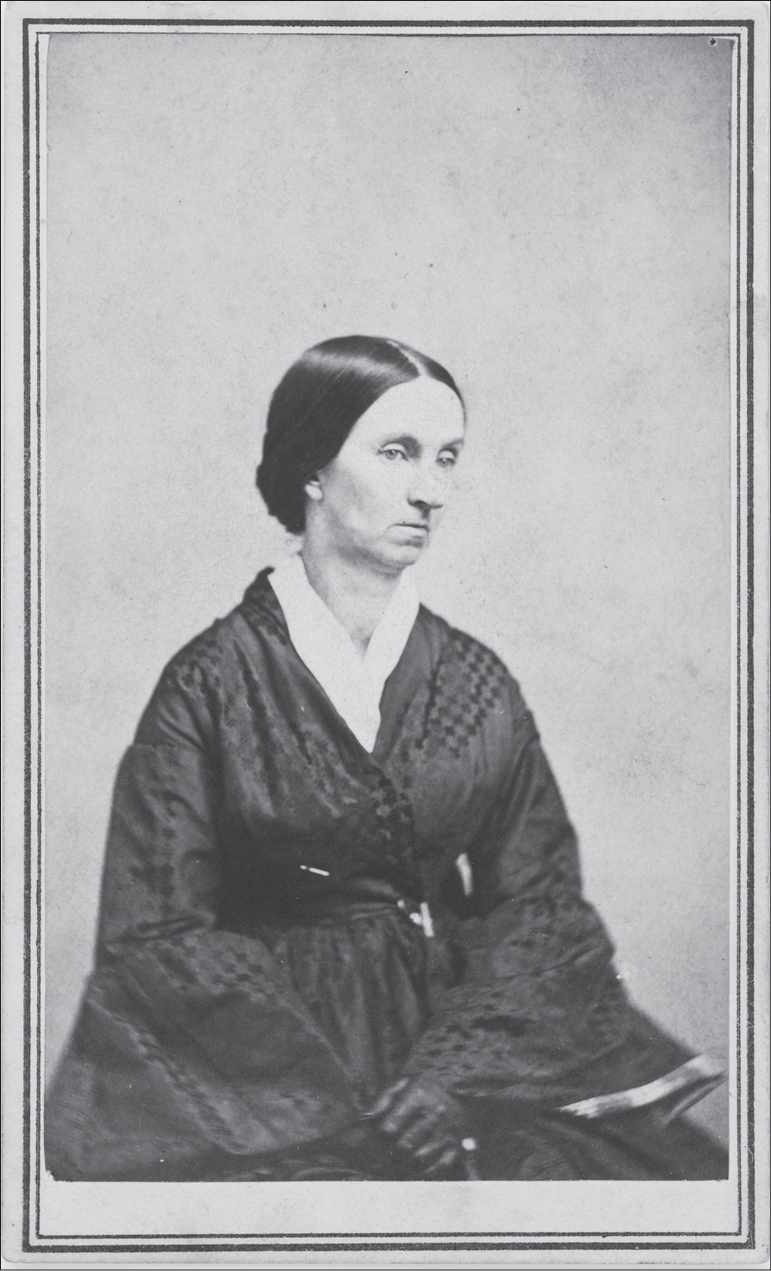

Jane Grey Swisshelm, carte de visite by Joel Emmons Whitney, c. 1865

NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY

Mrs. Jane Swisshelm sat in the President’s anteroom, eyes alert, patience strained to the limit. A longtime editor, she had an opinion on everyone in that town of little-big men, and swished her skirts through court and Congress with ease. The delicate beauty of her youth was still apparent in her late forties, making her sharp political judgments unsettling to some. Worse, she could trim a pretty bonnet and make a tasty biscuit, blurring the lines of domestic and public spheres that defined gender roles of the day. Men were afraid of Jane Swisshelm. She broke barriers wherever she traveled: she had been the first woman to take a seat in the congressional reporters’ gallery, shed her husband when he became disagreeable, and stood down the opposition while her printing press was being burned in St. Cloud, Minnesota. When opponents taunted her about “unfeminine activities,” she spit back retorts that hit squarely below the belt:

You say—and you are witty—That I—and tis a pity—

Of manhood lack but dress;

But you lack manliness,

A body clean and new,

A soul within it, too.

Nature must change her plan

Ere you can be a man.6

Swisshelm believed that women had not only the right but an obligation to influence issues of the day. She thought it a moral imperative to tackle the world’s wrongs and overturn societal prejudice. Women might be disenfranchised, she maintained, but they could write, lecture, petition, and lobby—and nothing less than their own welfare was at stake. The “life, liberty, and happiness of woman depends on the policy of her own country,” Swisshelm asserted in an early editorial, and females must help form those policies. As an accomplished orator she brooked no compromise, argued unrelentingly, and, as one critic noted, was “disagreeably witty.” She would make a perfect martyr, concluded an adversary, “for she would risk the stake any time for the privilege of the last word.” The ink might flow acrid from her pen, but it had helped Abraham Lincoln win votes in Minnesota, where she was considered the “Mother of Republicanism.” Now, in January 1863, Swisshelm had come to Washington on an official mission to persuade the chief executive to take strong action against the Sioux Indians. She meant to be heard.7

Lincoln did not hear her. He was busy with other matters; he was overbooked; he could not be persuaded. After three attempts to gain a private interview, Swisshelm was advised to see him at a reception, but, as she remarked, if the President would not seriously discuss her concerns, she had little interest in a grip-and-grin meeting at a crowded levee. It was “useless to see Mr. Lincoln on the business which brought me to Washington,” she concluded, “and I did not care to see him on any other. He had proved an obstructionist . . . and I felt no respect for him.” Convinced the President was stumbling through his job, “without any comprehensive plan” and “getting deeper and deeper into the mire,” she instead called on Edwin Stanton, an old friend from her days as an editor in Pittsburgh. Not until she had gained her object in other ways would she finally go through a receiving line and shake the President’s hand.8

Talented, temperamental Anna Dickinson appeared on the political horizon in 1861 “like a meteor,” Elizabeth Cady Stanton would write, “as if born for the eventful times in which she lived.” A young, lithe Philadelphian, Dickinson had grown up with the rising abolition movement—and with the Quaker assumption that women could and should speak their minds. While still in her teens she began to agitate in antislavery and feminist causes; as the national crisis heightened, she waded into political topics as well. She made some early faux pas, bashing popular figures such as General George McClellan, a mistake that resulted in dismissal from her job at the United States Mint, but once she found her ground, her confidence soared. Veteran abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison arranged a series of lectures for the twenty-year-old; and when Wendell Phillips requested that she substitute for him at a Boston rally, afterward embracing Dickinson with tears in his eyes, her reputation gained national status.9

Anna E. Dickinson, photograph, c. 1855–65

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

By 1863 Dickinson had become something of a phenomenon. She had youth, natural presence, and an undaunted spirit. She spoke without notes, and her rich contralto voice was said to have the mesmerizing power of a spiritual medium. One critic who saw Dickinson pacing the stage compared her to a tigress in a cage: if anything, he wrote, “her look was more fierce, her bearing more majestic, and her wrath more terrific.” Mingling argument, pathos, and invective in her talks, she created an oratorical style whose power was compared to Demosthenes and Joan of Arc. Dickinson spoke before thousands at New York’s Cooper Institute; and in the run-up to the 1863 elections Republican officials in four states organized mass meetings starring Dickinson. All were close races that were critical for Lincoln’s war policies. In these campaigns Dickinson was not asked to address reform-minded women or argue social issues, but to sway male voters—a most unusual circumstance at the time. One Connecticut official, who admitted his initial skepticism, conceded that Dickinson “had not spoken ten minutes before all prejudices were dispelled . . . ; sixty minutes and she held fifteen hundred people breathless with admiration . . . ; two hours and she had raised her entire audience to a pitch of enthusiasm which was perfectly irresistible.” Every candidate she supported won.10

Dickinson was happy to stump for Republicans, but her real interest was in the plight of slaves, freedmen, and the U.S. Colored Troops. She was frustrated with Lincoln, who, she believed, gave only lip service to the cause of emancipation, and angered when the President overturned proclamations by Generals John Frémont and David Hunter that liberated slaves in their military districts. “Abraham Lincoln,” Dickinson fumed, “had made such an Ass of himself for the Slave Powers to ride” that he was stifling army recruitment and demoralizing the nation. Mollified somewhat by the Emancipation Proclamation but still concerned that nothing was being done to help ex-slaves thrive as free men, she took the stage with antislavery luminaries like Frederick Douglass to attack the administration’s lackluster policies and halfway measures.11

At the zenith of her career, Dickinson was invited by one hundred members of Congress to speak in the Capitol, the first woman so honored. On January 16, 1864, escorted by Vice President Hannibal Hamlin and the Speaker of the House, Dickinson stepped onto a platform in the Hall of Representatives to address the nation’s leaders on “The Perils of the Hour.” The audience saw a “slim waisted girl with curls cut short as if for school,” wrote an army officer who was present, “eyes black with the mirthfulness of a child, save when they blaze with the passions of a prophetess, holding spell bound . . . two thousand politicians, statesmen and soldiers!” Dickinson challenged Copperheads, railed against the perfidy of secession, and praised the nobility of Union troops. Her most impassioned language, however, was reserved for Lincoln’s recently announced reconstruction policy, which showed generosity to former slaveholders and promised nothing for the freedmen. “Let no man prate of compromise,” she thundered. “There is no arm of compromise long enough to stretch over . . . the mound of fallen heroes, to shake hands with their murderers.” Her words were undiluted, even when Lincoln and his wife entered the room. The President sat with head bowed while she denounced his actions and was too abashed to speak when called to the podium. It was a sensitive moment, for the Republicans had not yet nominated their candidate for the November presidential election. A congressman sympathetic to Dickinson’s viewpoint remarked that the address was “full of beautiful things and brilliant consecutions”—but it was “very sharp. I should as soon have a chest of joiner’s tools for a wife.”12

Dickinson’s remarkable performance was capped by a surprise finale. After roundly censuring Lincoln, she suddenly changed direction and gave a stirring endorsement for his reelection. The war had been a people’s war, she cried, and it must be guided by a man of the people. There was much to lament, but also much left to do; and the man to do it was Lincoln. Just why Dickinson chose to alter her tone so completely is unclear. Historians have speculated that she may have been embarrassed by Lincoln’s presence, or that she was counseled to soften her message. Perhaps she instinctively knew she needed an upbeat ending for the largely Republican audience. If so, she got the response she desired. The rousing conclusion brought forth “volleys of cheers” and a personal greeting afterward from the President. “You have conquered Washington,” wrote an admirer, “you have taken the capital.”13

Dickinson immediately regretted the endorsement. Three days later, at an interview arranged though Pennsylvania representative William D. Kelley, she renewed tensions with Lincoln. Their conversation centered on efforts to implement his reconstruction plan in Louisiana. It had been hastily pushed through and threatened to leave many freedmen in a state of quasi-slavery. According to Dickinson, she told the President this was “all wrong.” She was also offended by his soiled shirt and stockings, his “old coat out at the elbows, which looked as if he had . . . used it for a pen wiper,” and became impatient when Lincoln tried to change the subject with the ubiquitous “that reminds me of a little story.” “I didn’t come to hear stories,” snapped Dickinson. Three months later there was another meeting, at which both parties apparently tried to make amends, with Dickinson offering a semiapology and Lincoln declaring he would rather “have her on his side . . . than any twenty men in the field.” But there was no agreement on reconstruction policy, which Dickinson had hoped to influence. When Lincoln closed the conversation by saying if abolitionists wanted him to lead, “let them get out of the way and let me lead,” Dickinson vowed: “I have spoken my last word to President Lincoln.”14

Dickinson publicly complained about the unfortunate encounters, and Kelley—himself in need of party approval at the time—admonished her. The congressman gave a modified version of events, in which a more cordial Lincoln essentially ignored the triumphant rhetorician and Dickinson remained demurely quiet. Dickinson was known to be excitable, and her self-assurance may have turned to overconfidence in these meetings. That she may have overreacted is entirely possible. Yet nothing in her account was at variance with depictions by myriad male visitors who also witnessed Lincoln’s shabby attire, dependence on homely tale-telling, and reluctance to take advice. When Dickinson began to belittle the President on the campaign trail, however, matters became more serious. All agreed that the meteoric ascent of America’s Joan of Arc had lost its trajectory and was shooting dangerously into uncharted space.15

Clara Barton had been marching in lockstep with Abraham Lincoln since the beginning of his administration. One of the earliest women employed by the government, during the 1850s she had surpassed male colleagues at the Patent Office in quality and quantity of work. Nonetheless, when James Buchanan assumed the presidency, Barton was accused of being a “Black Republican” and summarily dismissed. After the votes were tallied for Lincoln, she was brought back, praising the new chief executive and bemusedly stating she had returned to Washington to “watch the play.” The play proved far more dramatic than Barton imagined. Within months she found herself in a wartime capital, chafing to contribute to the fight. “I cannot rest satisfied,” she wrote to a friend; “it is little one woman can do, still I crave the privilege of doing that.”16

By the time she took a seat in the President’s waiting room in February 1865, Barton had “done” a great deal. One of the earliest people to recognize the insufficiency of Union medical arrangements, she not only collected supplies but went to hospitals and camps to distribute them personally. Many women labored at the front, but only a handful were actually on the battlefield, under fire, as was Barton. On fields like Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Fort Wagner she extracted bullets, braved firestorms that shot away portions of her skirt, and bound amputated limbs under artillery bombardment. “I am told that she seemed on such occasions totaly insensible to danger,” an administration confidant remarked. She also instructed recently freed slaves, turned her rooms into a vast warehouse for medical goods, and fought to obtain proper food and treatment for the wounded. “The patriot blood of my fathers was warm in my veins,” she stated, by way of explanation. By war’s end the name Clara Barton was recognized in households across the North. Already she was known popularly as the “angel of the battlefield.”17

Clara Barton, photograph, c. 1865

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Moreover, she had championed not just the common soldier but Lincoln himself, defending his policies when few wartime workers would do so. “I grant that our Government has made mistakes, sore ones too in some instances,” Barton candidly told New York editor Thaddeus Meighan from the siege of Charleston, “but we shall never strengthen their hands, or incite their patriotism by deserting and upbraiding them.” She claimed to have no political motive (“as I am merely a soldier, and not a statesman, I shall make no attempt at discussing political points”), but her attitudes marched forward at the same pace as the President’s. “Who am I going to vote for?” Barton taunted her skeptical feminist friend Frances Dana Gage in 1864. “Why I thought for president Lincoln, to be sure. I have been voting for him for the last three years.” He had not assessed the situation clearly at the opening of the war, she admitted, and had stumbled badly in military affairs, but Barton still stood by her man. She would support whomever the Republicans nominated, she told Gage, but she hoped the “care worn face” that had become “very dear” to her would again head the presidential roster.18

Now Barton was seated for the third day in Lincoln’s vestibule, hoping to offer him one more service. She was a striking figure at age forty-three. Her face was not beautiful, but strong-featured and full of character. Her gray-tinged black hair, specially dressed that day by a friend, was tied back in a tasseled silk net; her hands were nervous in the new gloves she had bought for the occasion.19 The war was nearing its end and, again sensing a need she could fill, Barton wanted to propose a program to catalog “missing” soldiers. There had been no system of identification, no detailed prison rosters, and nearly two hundred thousand graves were unmarked. On the home front, where thousands of households waited nervously to hear a familiar footstep, it was an anxious issue. Barton hoped to interview men returning from Southern prisons who might remember a missing comrade’s fate and to compile lists for official records. The War Department had embraced the project, and Barton sent a formal petition to Lincoln, summoning her most influential contacts to endorse it. Massachusetts congressman William Washburn penned a strong letter recommending Barton as “one of the most useful devoted valuable ladies in the country,” and General Ethan Allen Hitchcock, who was in charge of prisoner exchange, also tried to catch Lincoln’s attention. Even powerful Senator Henry Wilson, who often consulted Barton on military matters, wrote the President, advising that “Miss Barton calls on you for a business object and I hope you will grant my request. It will cost nothing. She has given three years to the cause of our soldiers and is worthy of entire confidence.”20 Yet here she was waiting again at the White House, turned away by the guards. Bitterly disappointed, Barton left, succumbing to tears in the privacy of her rooms. “I . . . do not feel it my duty to bring myself to public mortification in order to do a public charity,” she crossly concluded.21 Nonetheless, she borrowed some courage as well as a fur coat from a fellow war worker and tried the White House door the next day. Once more she was not admitted. In the end, Lincoln delegated the issue to General Hitchcock. Considering this an authorization, Hitchcock approved the plan.22

Miss Barton was never received by the President.

These stories show Lincoln in an impatient mood, annoyed with petitions and the high-pitched public criticism that forms part of every presidential brief. There may have been genuine reasons for the unfriendly reception these women received at the White House. Lincoln was irritated after Republican defeats in the election of November 1862 when Stowe met him, and not particularly receptive to charges of inaction; Swisshelm was seen as something of a harpy, swooping in to whip the President into stronger action against the Sioux, just when he wanted to back away from the situation; Dickinson had publicly denounced his policies in sarcastic terms. But . . . Clara Barton? That snub is harder to understand, given her fame, and her staunch loyalty to Lincoln.

The same discouraging note was sounded in a long string of encounters with other women. Anna Ella Carroll, a widely respected pamphleteer who had written powerful pieces that helped keep Maryland in the Union, was turned away with an explosive presidential laugh when she sought the pay promised for her work. She was then mortified to find Lincoln had openly ridiculed her to other influential men.23 Mary Livermore and Jane Hoge, who collected a half million dollars for medical stores while directing the Western Sanitary Commission, called for words of encouragement but found Lincoln’s reception so “dispiriting” that it “cost those of us who belonged to the Northwest a night’s sleep.” Julia Ward Howe, author of “Battle Hymn of the Republic”—essentially the Union Army’s anthem—was treated “perfunctorily” by the President, and rudely overlooked as he spoke to her escort, Governor John Andrew.24 Mary Abigail Dodge, whose writings under the pseudonym Gail Hamilton bolstered home-front morale after a string of military disasters, was unable to get an appointment with either Lincoln or his wife when she called to offer her services. Cordelia Harvey, widow of a Wisconsin governor who had been killed at the front, and herself a hospital worker, was also roughly treated. She tried to gain approval for a convalescent facility behind the battle lines, only to meet with a scowl and a “snap” from Lincoln that she was presuming “to know more than I do.” (In fact, Harvey did know considerably more than Lincoln about hospital conditions. She persevered, but persuaded him only after she raised the issue of soldier votes in the Midwest.)25 A Quaker activist met with similar testiness. When she entered a plea for immediate emancipation, counseling the President to fulfill the Lord’s design, he responded with “ill-subdued impatience.” “Has the Friend finished?” he asked testily. Lincoln then retorted that if God had instructions for him, He would give His advice personally, not through a lady.26

And so the progression of discomfiting stories continued, forming a clear and consistent pattern. Indeed, the intriguing question is not whether Abraham Lincoln rebuffed the leading women of his day, but why he did so.

II

Lincoln’s professional reputation rose at a time when women were beginning to gain a voice and a purpose in the political world. In the early days of the republic, it was believed women’s role in democratic development lay in educating their children to support patriotic ideals. In the decades after the Revolution, the rise of evangelical religion encouraged women to support causes that softened the harsher edges of society, such as temperance, or school and asylum reform. As it became more acceptable for women to take a public part in such movements, the line was blurred between their “legitimate” role in domestic matters and participation in the male “sphere” of civic affairs. When the first female antislavery society was founded in Boston in 1833, for example, charter members feared losing their reputations, so strong was the bias against women’s involvement. Four years later there were seventy-seven similar societies. Such organizations offered an increasing opportunity for women to contribute, teaching managerial skills as well as methods of pressuring the government. Charity leaders wrote bylaws, ran meetings, and through acts of incorporation were able to raise money, invest funds, or bring lawsuits—all activities that were prohibited to married women. At the same time, women were reshaping their outlook. They no longer saw worldly affairs solely through the prism of relationships to men but relied on their own views and trusted their own competence.27

The election of 1840 proved a watershed for women’s direct participation in the political pageant. The Whigs, hoping to portray themselves as the more honorable party, believed they could downplay vulgar “male” motives (like greed and ambition) by harnessing female “purity” to elevate the tone of their platform. Understanding the value of public theater, Whigs enlisted women as moral standard-bearers to write tracts, present banners, and join parades. Ladies did not hesitate to become allegories of virtue, riding in white gowns atop floats dedicated to “Liberty and William Henry Harrison” or pinning bright partisan buttons to their bodices. Slogans such as “Calhoun, Tecumseh, Cass or Van / With the LADIES’ aid we’ll beat the whole clan” or—later—“The girls Link on to Lincoln” helped push Whig and Republican candidates across the victory line. Democrats, who preferred to keep women at a pristine distance from rough political arenas, reluctantly followed suit.28

All this was a far cry from male-dominated political rituals that had featured drinking, acrimonious debate, and symbolic “pole-raisings.” (The last was a particular craze in Lincoln’s Springfield district, where rival parties cut huge tree trunks, then compared the length of their “poles” and competed to see who could raise them most rapidly—with the obvious corollary that the quicker the pole was erected, the more potent the candidate.)29 Once women were given a role, they proved an asset. Their presence at rallies was not only morally uplifting but subliminally erotic, as evidenced in excited descriptions of “exquisitely moulded arms” and “bounding bosoms.” Lincoln, who was a spirited campaigner in the 1840 contest, must have been aware of this trend, for women played an active part in his home state. Mary Todd, whom he was courting, was among the enthusiasts. “This fall I became quite a politician,” she confided to a friend, “rather an unladylike profession, yet at such a crisis, whose heart could remain untouched?” By 1844 women were an accepted feature of electioneering, and Henry Clay could declare: “I hope the day will never come when American ladies will be indifferent to the fate and fortunes of our common country, nor fail . . . to demonstrate their patriotic solicitude.”30

Many early feminists were allied to the antislavery movement and gravitated naturally to the Republican Party, which most nearly expressed their views after the demise of the Whigs. Women were present at the creation of the party at Ripon, Wisconsin, in 1854, and were eagerly sought to grace serenades and speeches. When the Republicans nominated John C. Frémont for president in 1856, reform-minded women made strong statements on his behalf. Frémont’s dashing looks, reputation as a western trailblazer, and outspoken opposition to slavery reflected many female hopes for the country’s future. He was all the more attractive since his wife, Jesse Benton Frémont (also known as Jessie), was conspicuous in the campaign. Jesse Frémont, a scion of Missouri’s influential Benton family, was a hardheaded political broker in her own right and the power behind her husband’s compelling public image. “Isn’t it pleasant to have a woman spontaneously recognized as a moral influence in public affairs?” enthused Lydia Maria Child, an early advocate of abolition and women’s rights. “What a shame that women can’t vote! We’d carry ‘our Jessie’ into the White House on our shoulders, wouldn’t we?”31

Women were in fact moving exactly in the direction Child indicated—from moral influence to an aspiration for true political rights. The emphasis on changing society through good works was giving way to a call for legal reforms, especially against practices that denied women control over their property, their labor, and their children. Early political organizers, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, who spearheaded the first women’s rights conference at Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848, wanted concrete legislation that would overturn decades of officially mandated subordination. Increasingly, they were willing to make themselves unpopular to fight for it. By the time of Lincoln’s presidency, they could point to some real gains. The New York State Earnings Act of 1860 gave a woman the right to sue and to retain wages in her own name. Twenty-nine of the thirty-five states had passed some kind of legislation granting married women control of their prenuptial property by 1865. Women were writing tracts under their own names or taking the public platform without apology. Their words sometimes carried great weight. Anna Ella Carroll, who essentially wrote the textbook on presidential war powers and influenced several antebellum elections, could attest to this. So could Harriet Beecher Stowe, whose views held such power that people confused Uncle Tom’s Cabin with a government document. Petticoats in a parade no longer gratified women: they wanted a voice and a way of making it heard. “The speculative has in all things yielded to the practical,” commented “Isola” to the women’s rights journal Una in 1852. “In this sense, moral suasion is moral balderdash.”32

What such women wanted was to turn the dynamic inside out. Instead of inspiring men to reach a superior feminine moral standard, they wanted an equal chance to fix those standards politically. As they grew bolder, “strong-minded women” (a popular and not altogether flattering term for advocates of liberal reform and female rights) expanded their scope of action. They spoke out for better education, for dress reform, for the ability to choose a profession—and to be paid for their work. Increasingly, they also demanded the ballot, without which, many thought, they could never truly be part of the democratic community. Crusaders like Sarah Smith Martyn, who founded the New York Female Moral Reform Society in the 1830s, came to believe that disenfranchising women underlay “the whole enormous structure of evil which . . . must be removed before the regeneration of the world can take place.”33

If the ballot was essential, it was also maddeningly elusive. Yet what had once been unthinkable was now at least discussable. Three weeks before Lincoln gave his celebrated 1860 address at New York’s Cooper Institute, Henry Ward Beecher—Stowe’s brother—stunned the same house with a rousing speech on “Women’s Influence in Politics.” In it he further blurred the boundaries of gender-based spheres. Political rights would not detract from a woman’s role as moral guardian, he argued, but would make her an even richer asset at home. “Whatever makes her . . . a larger-minded actor, a deeper-thoughted observer, a more potent writer or teacher,” the Brooklyn-based clergyman declared, “makes her . . . a better wife and mother.” Beecher advocated giving women the vote and also encouraged them to hold public office. The body politic, he argued, would be strengthened by contributions from both men and women, for their interests were one. Indeed, his plea was for men, who were robbed of a better society by limiting women’s involvement. The ideas were bold, but just as striking was the speaker and his forum. Beecher was a known reformer, but he was also a Protestant minister, popular with the middle class. His words had a power and reach enjoyed by few others in America. Once he spoke out, the quest for a female role in national politics entered the mainstream.34

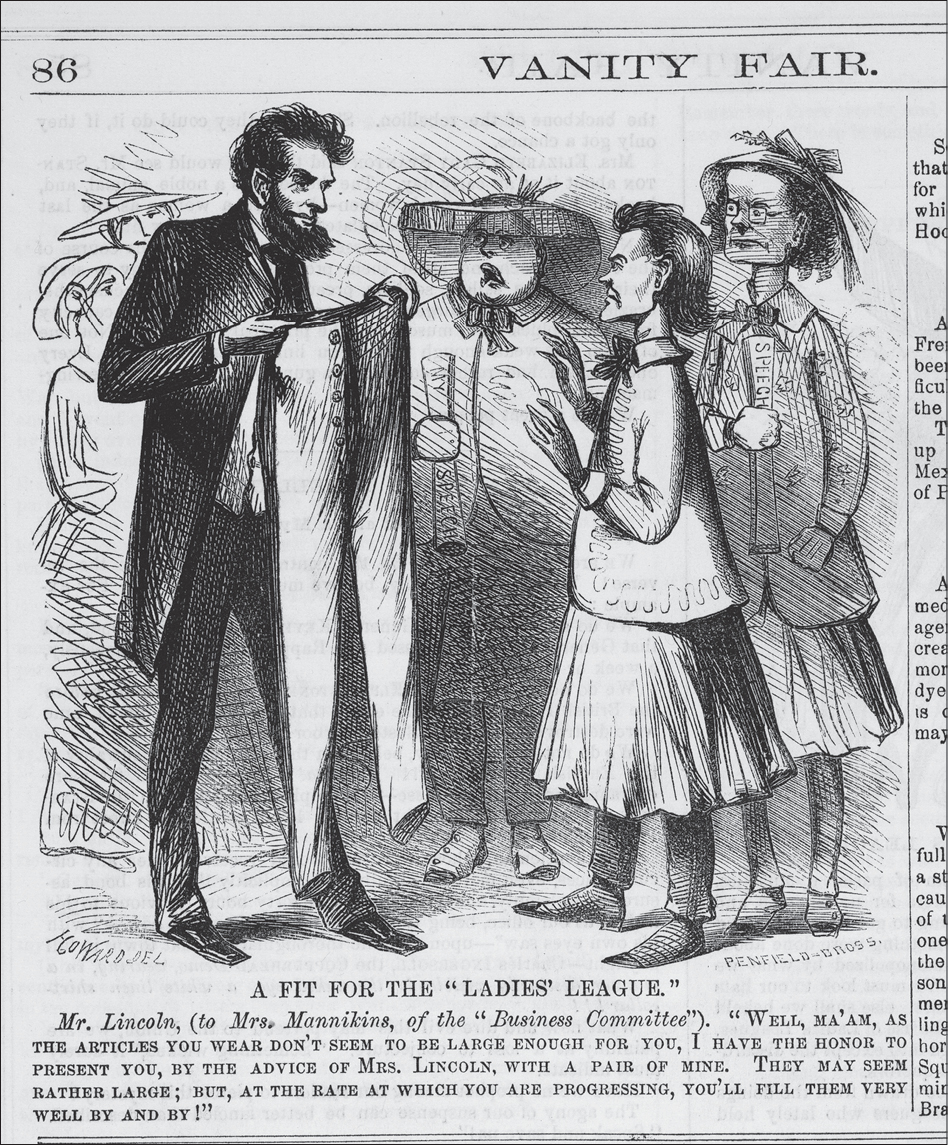

Progressives like Henry Ward Beecher might uphold female aspirations, but many people looked askance at women’s public visibility. It ruffled sensibilities to see ladies give impassioned speeches, and it bred fears that orderly societal relations were about to be upended. Pioneering women were sometimes viewed as curiosities, or simply ignored, but many people considered them meddling misfits. When well-regarded activist Caroline Healey Dall lectured on “Women’s Rights Under the Law,” a prominent Harvard scientist, Josiah Parsons Cooke, likened it to “hen-crowing,” and accused her of trying to “annihilate marriage.” He was all for open discussion, Cooke concluded, but “when obscenities constitute the material of a lecture, it is time for the police to interfere.” Antislavery champion Charles Sumner was generally an ally of women; nevertheless, he discouraged Julia Ward Howe from publicly reading her essays. (“I did not expect your sympathy in this undertaking,” complained Howe. “But I do feel that I have cast too much ‘love oil’ on your head for you to throw cold water on mine.”) Others simply thought the movement and its leaders ridiculous. Feminists were a subspecies afflicted with “Gynaekokracy,” opined a journalist from Geneva, New York, “bold, unblushing, flippant, unfeminine and bad imitators of men.” Petroleum V. Nasby and Artemus Ward both roasted feminists, liberally using terms like “she-devils” to describe them. Vanity Fair ran cartoons showing beefy activists boisterously bullying boys and prodding the President.35 Women were also nervous about the burgeoning feminist movement and many took care not to associate too closely with it. Mary Lincoln joined others who denied they were “strong-minded,” declaring she had a “terror” of that breed. Nonetheless, she viewed herself as a ringside adviser to her husband and admitted she thought it wrong to withhold “a word fitly spoken . . . in due season.”36

“A Fit for the ‘Ladies’ League,’” wood engraving, Vanity Fair, May 30, 1863

Just what Lincoln thought about women’s growing political involvement is difficult to know with certainty. He was not particularly keen on political pageantry of any form, preferring behind-the-scenes strategizing with a few collaborators to flashy, emotion-laden spectacles. “I think too much reliance is placed in noisy demonstrations,” he stated. “They excite prejudice and close the avenues to sober reason.”37 As a young man Lincoln once declared he favored sharing government with everyone who helped bear its burdens: “Consequently I go for admitting all whites to the right of suffrage, who pay taxes or bear arms (by no means excluding females).” Some have seen this as a clear statement of support for women’s rights. Others have found it an ironic, even sarcastic comment, since women did not join the militia in 1836, and only a few held property in their own name, making them taxpayers.38

While living in New Salem, Lincoln belonged to a debating society that discussed whether women should be educated and have voting rights, but his opinion on these issues is not recorded. On the stump, he cautioned against the danger of curbing freedoms for one group in order to elevate another, but when he invoked the principles of the Declaration of Independence or asked rhetorically, “Who shall say, ‘I am the superior, and you are the inferior?’” he was discussing male prerogatives and did not include women in the discussion. His law partner William Herndon claimed Lincoln’s innate sense of justice made him uncomfortable denying privileges to others that he personally enjoyed, and that he “often” said women were the “other and better half of man” and entitled to full rights. Lincoln did not publicly support this, said Herndon, for he felt the moment had not yet come to put it before the people. These comments were written nearly half a century after the two men shared an office in Springfield, however, and Herndon’s quirkiness makes him a problematic source. In any case, if Lincoln believed women deserved greater civil liberties, he never acted on it in any way.39

There is evidence that Lincoln defended women skillfully in his years as a trial lawyer, particularly in cases of sexual violation. In his first public defense, a young woman brought suit against a seducer who refused to marry her. Lincoln won his client a substantial award by arguing that a man’s soiled reputation could be “washed” clean, while a shamed woman was like a broken bottle that could never be mended. In other cases, Lincoln successfully advocated child support for unwed mothers, won damages for a woman raped by her father, and prosecuted the violator of a seven-year-old girl, persuading the jury to sentence him to eighteen years in prison. Once in the White House, he seems to have been favorably disposed to loyal women who were in need or who had been directly wronged. The President responded positively to widows and to those who appeared helpless. He also showed sympathy to families of slain U.S. Colored Troops, understanding that the South’s refusal to recognize black marriages denied wives many rights, including pensions. In these cases Lincoln could play the traditional male role of protector and generous benefactor. Women clamoring for position, promoting reform, or proposing better ways to manage the war, no matter how constructive, found a far less receptive hearing. These were not supplicants, but demandeurs, who challenged him with both their ideas and their expectations. The parade of forthright females rebuffed in the presidential office indicates a great deal of ambivalence on Lincoln’s part about ladies who sought something more than a patronizing dispensation of favors.40

III

Lincoln’s discomfort with accomplished women also reflected his innate malaise around the fair sex. The origins of this are puzzling, for in early life he had positive relationships with his mother, stepmother, and older sister Sally. Nancy Hanks Lincoln was by every account a woman of intelligence, industry, and kindness. An in-law recalled that “she was a brilliant woman—a woman of great good sense and Modesty. . . . Tho[ma]s Lincoln & his wife were really happy in Each others presence—loved one another.” Others remembered the President’s mother as tenderhearted, but marked by sadness.41 Some said Abe, with his dark hair, hazel-gray eyes, and sharp features, took after her physically as well as temperamentally. It is uncertain whether she was literate, but at least one account has Lincoln stating that “[a]ll that I am or hope ever to be I get from my Mother.” Whether Nancy Lincoln resembled the “angel mother” concocted by later artistic imagination is more doubtful. Women aged quickly on the frontier, and her son’s only description mentioned a “want of teeth” and “weather-beaten appearance in general.” It was commonly acknowledged that her death in 1818 was a calamity for the family and a sorrow in the community.42

After Nancy Lincoln’s burial, the household was run by Abe’s sister Sarah—known as Sally—who was two years older than her brother. Sally took after her father physically and was a bright child: “a gentle Kind, smart—shrewd—social, intelligent woman—She was quick & strong minded,” stated a neighbor.43 Abraham was disturbed when Sally married Aaron Grigsby at age nineteen, believing Grigsby treated her badly. He made his displeasure clear enough that the Grigsbys did not invite him to a double family wedding. Lincoln’s response was to pen a scathing poem called “Book of Chronicles,” long remembered in the community as a “good—sharp—cutting” satire about a mix-up of bridal chambers, featuring pointed barbs about the masculinity of the male Grigsbys. The “Chronicles” heightened tensions among the in-laws and resulted in a fistfight—the neighborhood’s standard way of resolving differences. William Grigsby, who offered the fight, refused to take on the much larger Lincoln, and John Johnston, Lincoln’s stepbrother, was substituted. When the contest started going against Johnston, Lincoln stepped in and thrashed Grigsby. Sally died in childbirth after little more than a year of marriage, and Abe was said to have been devastated.44

The anchor in Lincoln’s youth was his stepmother, Sarah Bush Johnston Lincoln, a woman who impressed Herndon as rising “high above her surroundings.” Thomas Lincoln had known her before his marriage to Nancy Hanks, and he returned to Kentucky to wed Sarah about a year after Nancy’s death. A widow with three children, Sarah was described as tall, handsome, and “straight as an Indian.” A photograph taken later in life shows a woman with large, pale-colored eyes and regular features, her face framed in a ruffled cap. She was practical and unflappable, a good choice “to tie to,” as one neighbor remarked, and equal to the work of raising five children in a frontier cabin. Sarah arrived in Indiana with a wagonload of furniture and a few books, set to washing the children until they “looked more human,” and proved to be a sympathetic parent. She thought Abe a good, obedient boy, encouraged his reading, and was proud of his success. She later said that “his mind & mine . . . seemed to run together—move in the same channel.”45 Lincoln appears to have felt more affection for his stepmother than for his father, and took some trouble to provide for her in later life. Unfortunately, some of the funds were apparently siphoned off by other family members, and they ceased altogether after Lincoln was assassinated. Sarah Lincoln, who had not wanted her stepson to be president, mourned his death, spending her final years in poverty and loneliness.46

Sarah Bush Johnston Lincoln, photograph by H. R. Martin, c. 1865

CHICAGO HISTORY MUSEUM

There were shadows behind these bright relationships, however. Lincoln’s mother and sister both died when he was comparatively young. For a child, the death of a parent is a seminal experience and can have significant emotional consequences, often lasting a lifetime. We do not know exactly how these tragedies affected young Abraham, and there is no clinical evidence, but some have postulated that the early losses were responsible for his enduring melancholy. They may have also caused him to beware of emotional attachments to women, attachments that might end abruptly, through no fault of his own.47 Lincoln sympathized with a young girl whose father died in battle, saying that though sorrow comes to all, “to the young it comes with bitterest agony, because it takes them unawares.” He memorized a poem by Scottish poet William Knox called “Mortality,” which spoke of a girl, alive with beauty and pleasure, who was erased from the Earth “like a swift-fleeting meteor.” Lincoln spoke of his reverence for this poem (“I would give all I am worth, and go in debt, to be able to write so fine a piece as I think that is”) in the same breath as the memory of a trip he made in 1844 to the graves of his mother and sister. On that visit he mourned anew the “things decayed and loved ones lost” and felt keenly his helplessness against mortality.48

Other clouds hung over these relations, having to do with sexuality. Sister Sally had died in childbirth. Lincoln may have viewed this as the wages of passion, or blamed it on her husband’s lust. His mother’s reputation also seemed smudged with uncertainty. Herndon reported that Lincoln told him his mother was a bastard, the illegitimate child of Lucy Hanks and a well-off Virginia planter, and that Abe believed he had inherited superior traits from this man. There may have been some truth to the story, for Lucy Hanks was charged with fornication in Mercer County, Kentucky, and no wedding certificate was ever found for her. Herndon believed this caused Lincoln to feel he was different from other men, feeding his self-absorption and depression. There were rumors about the chastity of Nancy Hanks Lincoln as well. Several acquaintances speculated that she had had relations with neighbors, and that her son was perhaps not fathered by Thomas. (Cousin Dennis Hanks denied this; and Lincoln’s fellow circuit rider Henry Whitney pointed out that Thomas and Nancy Lincoln had been married before Abraham’s birth, making his legitimacy presumptive in law.) Whether true or not, such gossip may have disturbed the sensitive boy, causing him to mistrust sexual instincts or feel that the consequences of lovemaking were grave and intimidating.49

Lincoln’s odd looks and eccentric personality also fed his nervousness around the opposite sex. He formed friendships with sympathetic older ladies or the wives of his friends, but many witnesses remembered his discomfort around girls his own age. Some put this down to shyness; others thought he disdained girls as “too frivolous.”50 He could boast the standard attainments of frontier boys and was a fine athlete, but his outsized limbs, craggy features, and uncontrollable hair were made for mockery. An acquaintance from Lincoln’s Indiana years remembered that all the young ladies made fun of him, sometimes to his face. He appeared to join in the laughter and tried to spend time with the girls, “but no sir-ee, they’d give him the mitten every time.” His self-consciousness may have been sharpened by his stepbrother’s popularity. The smooth-talking Johnston was “mighty good lookin’ and awful takin’,” one woman recalled, while Abe “wus so quiet and awkward and so awful homely” that the girls shunned him. At times Lincoln joined them in self-deprecation, admitting that “if any woman, old or young, ever thought there was any peculiar charm in this distinguished specimen . . . I have, as yet been so unfortunate as not to have discovered it.” During the 1860 campaign, he reportedly quipped that it was lucky for him women could not vote, because his portraits would have defeated him.51

Lincoln’s peculiar looks were matched by his chronic social clumsiness. He had perfected an easy affability with the boys but clammed up in mixed company. Friends described a man who retreated into bashful silence when he could not avoid women, or introduced himself by shifting uncomfortably from foot to foot, making bizarre gestures, and proclaiming, “I don’t know how to talk to ladies!” Lincoln’s sister-in-law recalled that he did not have the knack of polite parlor talk, and Mary Owens, a young woman who kept company with him in 1836, wrote that he was too self-absorbed to offer the little attentions that “make up the great chain of womans happiness.” She recounted how once, when crossing a dangerous stream together on horseback, he showed no concern for her safety, and said he reckoned she could take care of herself. Owens thought this kind of careless comment sprang from a want of training rather than intentional rudeness.52 Most likely, it was a symptom of Lincoln’s habitual distraction, for both his mothers—from whom he might have absorbed some etiquette—were considered uncommonly decorous in their frontier community. In addition, Lincoln did not help himself by playing the buffoon in social situations. More than one person remembered him cutting up at barn raisings and corn shuckings, drawing his pals into a corner to tell crude stories until the girls complained he was “smashing up things generally.” Rather than quit, he would perform stunts to ruin the party. “Abe would go to all the dances in the country but would not dance, would get to one side . . . and tell jokes & funny stories & . . . turn handsprings and stand flat footed and lean backwards until his head would touch floor or ground, and a great many other athletic performances.” If Lincoln felt an adolescent triumph in these antics, they did not endear him to the girls.53

Perhaps Lincoln broke up dances and relished smutty jokes as a defense against his fear of sexuality—fear that he was unattractive, or of the consequences of normal male-female interaction. His courting history was certainly rocky. He saw several young women while living in New Salem and Springfield, including Mary Owens and a girl named Sarah Rickard. These relations were not easy, with Lincoln inept at flirtation and alternating between angst-ridden fantasies and self-recrimination. “Perhaps any other man would know enough without further information,” Lincoln wrote to a woman who was anxious to resolve their uncertain relationship, “but I consider it my peculiar right to plead ignorance, and your bounden duty to allow the plea.” It is a striking sentence, indicative of his self-centered tone as a suitor. (In one such letter he uses the word “I” twenty-six times in thirty-seven lines, and throws all responsibility for the relationship onto the lady.) Yet, perhaps nagged by the specter of his sister’s abuse, Lincoln also stated that he wanted badly to do right by women. He was not entirely sure what that meant and the dilemma made him hesitant. The unhappy outcome of several of these relations (Rickard reportedly “flung him high & dry,” and Owens also ultimately rejected him) cannot have bolstered his confidence.54

Lincoln’s most intense relationship appears to have been with Anne Rutledge, the daughter of an innkeeper in New Salem. By all accounts Anne (pronounced “Annie,” according to her sister) was a nice-looking girl, not overly intellectual, but sympathetic. There is evidence that Anne and Abraham enjoyed a close rapport, but the extent of the relationship is unclear. Anne was engaged to another man—which was perhaps part of the attraction for Lincoln, who was clearly most comfortable with safe, unavailable women. When Anne died of a fever, Lincoln’s grief was extreme enough to excite local comment, and his friends “feared that reason would desert the throne.” The legend of their ill-starred romance was inflated by Herndon, who later claimed that Rutledge was Lincoln’s true love, and her death a blow from which he never recovered. The most credible comments on the relationship were made by Anne’s sister Sarah, who, on reading a newspaper account of the affair, denied most of the rumors, including stories that Lincoln and Anne were engaged. “She came to her mind a little before she died & called for Lincoln,” recalled Sarah, “then they were left in the room alone & no one ever knew what they said she died soon after that. . . . There was not any of that kissing between them & there is a lot more there that is not true at all.” But there is no doubt that Lincoln was deeply affected by his friend’s death. The whole affair must have reinforced his sense that loving was a high-risk business.55

Some writers have interpreted Lincoln’s discomfort around women as a sign of uncertainty about his masculinity, suggesting he was “undersexed,” or possibly homosexual or bisexual. They cite his clumsiness in female company, his fumbling attempts at forging relationships, and his fear when faced with the possibility of a real attachment. They also look at the close camaraderie Lincoln shared with men—his strong friendship with Joshua Speed, and his evident fondness for young courtiers such as Nicolay and Hay, as well as for the flashy drillmaster Elmer Ellsworth. There was also gossip about the President’s close relation with a guard officer at his summer residence. Sometime in 1862 Lincoln did take a shine to Captain David Derickson, and the friendship was so widely known that it appeared as part of the 115th Pennsylvania regimental history. Drawing room chitchat included reports that Derickson sat at table with Lincoln when Mary was absent and even shared the presidential bed. Sleeping habits were much more casual in that era of overcrowded conditions and lower standards of privacy, however, so that a sexual implication was not necessarily self-evident, especially as it was talked about so openly. When Washington insider Virginia Woodbury Fox recorded the hearsay in her diary, she remarked: “What stuff!”56

In that era of prudery, the salacious revelations may have had more to do with Derickson’s access to privy information or ability to angle for position than any illicit acts. That all of Lincoln’s favorites were actively heterosexual also argues against the theory of closet liaisons. A more likely scenario, particularly once Lincoln became president, is the one seen in every White House: a powerful man, isolated by position, and anxious to maintain his authority, finding it easier to interact with low-level aides who openly admire him, than with competitive men who might benefit from a too candid discussion. Lincoln’s young companions arguably tickled his ego more than his physical fancy.

Whatever smoldered behind the rumors, there is abundant evidence of Lincoln’s heterosexuality. His political ally David Davis wrote that he was “a Man of strong passion for woman,” whose conscience kept him from seducing girls. Herndon seconded this, noting that Lincoln had “terribly strong passions for women—could scarcely keep his hands off them.” Lincoln told him that after Anne Rutledge’s death he fell into some of the seamier habits of the local lads and feared he had contracted syphilis from a casual tryst. Herndon also said that from the time Lincoln came to Springfield in 1837, he and Joshua Speed were “quite familiar—to go no further—with the women.” Speed was a well-known ladies’ man who sometimes helped set up assignations for his friend and, along with other “old rats” in the area, liked sexual gossip. Lincoln apparently shunned this kind of disrespectful talk. His friends commented that, if anything, his moral standards were liberal. His idea was “that a woman had the same right to play with her tail that a man had and no more nor less,” including the right to stray from the marriage vow if she chose. But Lincoln did not want to dabble in extramarital affairs, and when tempted, used his strong will to “put out the fires of his terrible passion.”57

Within the context of his day, Lincoln was also considered a “manly” man. This is particularly interesting since so much Lincoln lore glorifies traits usually considered feminine. After his assassination, and well into the twenty-first century, the sixteenth president was praised for his tenderness toward children and animals, his dislike of bloodshed, his kindness and avoidance of confrontation, and his love of “right” over “might.” He did indeed embody some of these things, some of the time. But they were not necessarily considered womanly characteristics in his day. The rough masculinity of the Jackson era prized physical power, rugged individualism, and a willingness to fight with the fists for dignity, power, or survival. Lincoln, whose love of book learning, absentminded ways, and outlandish appearance distinguished him from other frontiersmen, was fortunate in having inherited his father’s two outstanding traits: a powerful, athletic body, and a gift for storytelling. Thomas Lincoln had been obliged to prove himself by sheer physicality—winning neighborhood respect when he clobbered the local bully at a Kentucky tavern—much as his son took on the Grigsbys to defend his sister. In both cases, the lion of the territory was the most powerful slugger. As a kinsman noted, no one ever again tested Thomas’s “manhood in personal combat,” and this allowed him to become the mediator in community disputes. His son’s strength also earned him the right to make peace, rather than continually fight other males.58

But as midcentury approached, Lincoln consciously moved away from the cruder male stereotypes, embracing a new sensibility about masculinity that was sweeping the nation’s middle class. Restraint, self-reliance, and financial success were now considered the measure of a man; family concerns were his legitimate “sphere” as much as a woman’s; and real power came from directed energy and self-control. Maleness was not defined as a set of physical attributes, like muscularity, but as a series of actions. A true man achieved, rising in society and assessing masculinity by his economic standing vis-à-vis other men. De Tocqueville noticed this obsession to “get ahead,” seeing the American male as “restless in the midst of abundance”—forever glancing over a shoulder to gauge his comparative advantage. During this period, Lincoln stopped viewing himself as an axe-swinging, arm-wrestling strongman of rural districts and began identifying with the Whig Party’s professional men and bourgeois aspirations. He was especially taken by Whig leader Henry Clay. Although a Virginia aristocrat, Clay adopted the persona “Harry of the West” to promote the virtues of “self-made men,” a term he coined in 1832. To rise through “patient and diligent labor,” argued Clay, was to be a man worthy of the highest esteem. The conceit worked well for Lincoln, whose desire for betterment and earnest application to learning would become the stuff of national myth.

Interestingly, it was this generation of men who so neatly defined the concept of separate spheres for the sexes, the better to demark success in the male world. At the same time, their philosophy softened gender boundaries, so that men might also be admired for child rearing or their interest in culture. Mixed messages formed part of this credo and contributed to the anxiety de Tocqueville recognized in aspiring Americans, as well as the sexual confusion manifested by young men like Lincoln.59

IV

As he rose in society, Lincoln wanted to associate with women of a better class. Thus Mary Todd enters the stage. Lincoln evidently met the vivacious Kentuckian during the Tippecanoe campaign of 1840, when she and her friends were among the young women enjoying the excitement. Plump, bright-eyed Mary was one of sixteen children in a prosperous plantation family with important connections throughout the Ohio Valley. Her sister Elizabeth had married into the prominent Edwards family of Illinois, and when Mary visited them in 1839, she was a popular addition to Springfield society. Well-educated and an enthusiastic Whig, Miss Todd had supped with Lincoln’s hero Henry Clay, and she enjoyed parlor politics and flirtatious repartee. She was also ambitious. Mary told more than one person that she intended to marry a man who would become president. Lincoln caught her eye.60

The two corresponded, planned group outings, and occasionally met, probably at the Edwards home. Twenty-one-year-old Mary was described as the “very creature of excitement,” and her sister recalled that Lincoln was often struck dumb in her company. Their backgrounds were strikingly different and Mary’s family thought Lincoln an unsuitable match. Still, the two had similarities. Both had lost mothers at a young age; both enjoyed reading and reciting poetry and were obsessed by politics. Yet whatever fascination Lincoln felt for Mary Todd in 1840, by the following year he had either rethought the friendship or possibly was smitten by another visitor, the bewitching Matilda Edwards. Even Mary admitted she had never seen a lovelier girl than Matilda, who stole several Springfield hearts during her stay. Mary apparently tried to keep Lincoln’s interest by playing her many beaux off one another, but according to later accounts, he broke off the relationship in an awkward interview.61

What happened next is not entirely clear. Lincoln sank into a deep depression, which he called “the hypo,” making him “the most miserable man living.” On Mary’s side there was self-accusation, perhaps for playing too fast and loose with her suitors. Ultimately some friends intervened and a rapprochement followed. The two wed on November 4, 1842. Acquaintances speculated that Mary was the more interested party, and that Lincoln struggled with his sense of honor for having led her on. Others thought Lincoln’s insecurity left him doubting his ability to make a woman happy. There was also talk that he was selling his soul to gain the patronage of Mary’s powerful family. In any case, Joshua Speed was not “entirely satisfied” that his friend’s “heart was going with his hand.”62 Historians have wondered if a sexual element was not present, compelling the couple to marry quickly. The wedding did take place in haste, under arrangements that were unseemly for the elite Edwards family, and particularly for Mary, who loved parties, finery, and attention. Robert Todd Lincoln was born almost nine months to the day from the Lincolns’ marriage; but even had the couple enjoyed premarital relations, Mary could not possibly have known with certainty that she was pregnant. (Abraham was unsure too. The following March he told Speed he could not “say, exactly yet” if Speed would have “a namesake at our house.”) Both bride and groom were silent about their decision to wed, except for Abraham’s cryptic comment that his marriage was a “source of profound wonderment.”63

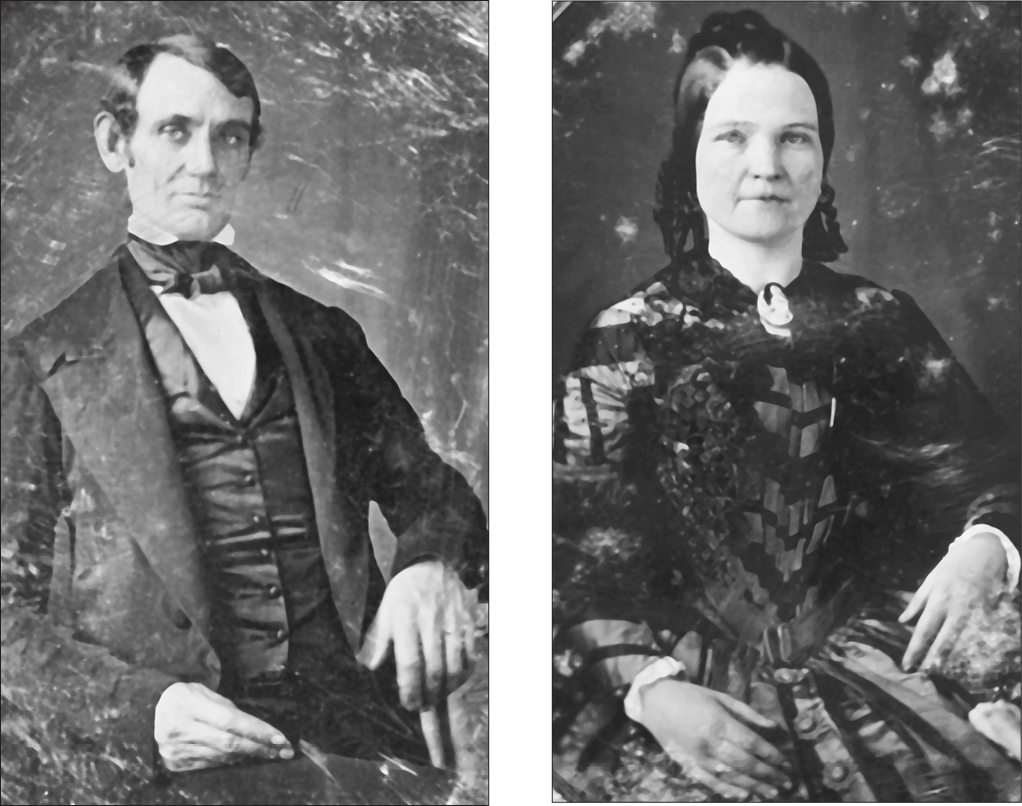

Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln, daguerreotypes by Nicolas H. Shepard, c. 1846

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

The relationship between a man and a woman is among the most basic and ancient of conflicts; each contains some element of mystery, as well as tension. The inner workings of the Lincoln marriage are particularly opaque, for scanty evidence of it survives. Mary sentimentally spoke of her husband’s “dear loving letters,” but only a few remain today. Perhaps she or their son Robert destroyed them; perhaps there were never more than a handful to begin with. Herndon thought his law partner wrote “fewer social letters—& even political ones” than any man he knew, and Lincoln admitted he avoided writing letters to women, “as a business which I do not understand.” The correspondence that does exist is kind and confiding, full of pets and plans and the domestic details that make up every life. The rest of what we know is secondhand, often relayed decades after the fact, making it exceedingly hard to sort the marital wheat from the chaff.64

The impression given in many recollections is that of an uneasy marriage between two difficult partners, whose tastes and inclinations sometimes clashed. Lincoln was moody and aloof, slovenly and coarse, careless and overindulgent with their four sons. He retreated into himself, whereas his extroverted wife looked for companionship and comfort—which she did not always receive. She was from a well-heeled home and she expected to live with a certain gentility. Lincoln’s muddy boots, unschooled table manners, and informal habits sorely tried her. Mary was often left alone, to feel vulnerable and unprotected while her husband rode the court circuit, or swapped stories in male-only back rooms. She was also apt to scold and demand, and many friends recounted ugly bouts of henpecking. Lincoln often ignored or laughed at this, which was perhaps an impolitic response. Nonetheless, his compatriots tended to think he was the long-sufferer. The frictions are illustrated by an instance when Lincoln harnessed himself like a horse to the baby carriage and, lost in thought, allowed the buggy to overturn and pitch the child—“kicking and squalling”—into the gutter. He did not notice and trotted on, but Mary flew from the house, full of fright and fury. Her husband ran off “with great celerity,” without waiting to face her stormy protest. Whether they fought it out or toughed it out in these situations is impossible to know; but a separation was clearly never in order. A cousin thought they were mismatched, but overlooked each other’s foibles and appreciated the values that lay beneath. Herndon, who was not an admirer of the marriage, concluded that “when all is known the world will divide between Mr. Lincoln and Mrs. Lincoln its censure.”65

There were also bright sides to the relationship. Mary was volatile and thin-skinned, yet she was “a delightful conversationalist, and well-informed on all the subjects of the day.” Lincoln had brought large debts to the marriage and in the early years she was game enough to live (and give birth) in a tavern. Mary epitomized devotion to a wife’s circumscribed sphere, in which home life was bound by the man’s expectations and career. Her husband was loyal and hardworking and intellectually stimulating, with serious prospects of becoming a leader in the state, if not the nation. What Abraham and Mary shared was the sum of these worlds: pleasure in their growing sons and searing sorrow at the death of Eddie, the second eldest; a comfortable life; excitement in their future prospects. Moreover, their political ambitions meshed. Mary was not only politically astute but enormously proud of “Mr. Lincoln” and protective of his interests. She encouraged him to dream large. He, in turn, took her advice seriously. There is also evidence that they enjoyed their companionship. Having looked forward to time alone when he arrived in Washington as a congressman, Lincoln almost immediately missed his wife. “I hate to stay in this old room by myself,” he admitted; a few months later, he encouraged Mary to “come along, and that as soon as possible.” After the ballots were counted on that fateful November night in 1860, the first person the president-elect ran to tell was his wife. “Mary, Mary!” he cried out, “we are elected!”66

The election would affect a great deal, including Lincoln’s family relations. From the beginning it was a controversial win, and the president-elect and his wife became targets for those wanting to diminish the Republican triumph. The nation’s deteriorating stability, a strenuous (and often criticized) whistle-stop trip to Washington, and threats of assassination did not lessen the tension. Nor was the situation helped by both Lincolns’ naïve expectations of the presidency. Republican insiders doubted the president-elect knew how to conduct himself in his new position and feared he and his wife would become objects of fun. Both Lincolns showed strain under these pressures.67

The White House was the prize they had worked for all their lives, but from the start the Lincolns were uncomfortable there. The transition from obscurity to First Lady had been abrupt for Mrs. Lincoln. She had envisaged herself as a grand hostess and was unprepared for either criticism or national crisis. Now the spotlight was trained on her without mercy. “Her smiles and her frowns become a matter of consequence to the whole American world,” observed journalist William Howard Russell. “If she but drive down Pennsylvania Avenue, the electric wire thrills the news to every hamlet in the Union.” Her dress, her manners, and, most of all, her political maneuvering were soon talked about. Mary first overstepped her position by spending large sums for furnishing the White House, without thought to either regulations or discretion. The Executive Mansion undoubtedly needed renovation, but it infuriated Lincoln to find her buying “flub dubs for this damned old house” while soldiers suffered.68 Mrs. Lincoln also sent unwise letters to major political figures, in which she censured generals and cabinet members, tried to influence appointments, or promoted Kentucky-bred horses for the cavalry. (There are indications that she was quite effective in her lobbying: Washington insiders stated that “she always succeeds,” and men of prominence like New York Herald owner James Gordon Bennett and Senator Charles Sumner courted her for access and information.) She was also vulnerable to intriguers like Henry “Chevalier” Wikoff, a professional rogue notorious for leaking information and angling for personal gain. Such men sometimes led Mrs. Lincoln into verbal indiscretion. If the motive was to help her husband, the impression it left accomplished the opposite.69

There were many who knew and admired Mary Lincoln, finding her, as did Commissioner of Grounds Benjamin French, “a smart, intelligent woman” who “bore herself well and bravely & looked Queenly.” George Bancroft, a renowned historian and a Democrat, was similarly “entranced” by the First Lady, whom he thought “a fair counterpart to Mr Lincoln’s brains.” General John Sedgwick noted how she visited his corps hospital “giving little comforts to the sick, without any display or ostentation.” Indeed, the dichotomy between those judging from afar, such as a catty diarist named Maria Lydig Daly, who concluded Mrs. Lincoln was little more than “a vulgar, shoddy, contractor’s wife,” and those who actually knew her is striking. But the damage had been early done and only worsened under the pressure of war. Mary Lincoln’s intrigues were whispered about both North and South, with the truth sometimes embellished. Some thought she was passing along state secrets, either through foolhardiness or from lingering Southern sympathy. Her relatives were slaveholders and three Todd brothers and a brother-in-law were enrolled in the Confederate Army, sparking “dark insinuations against her . . . Union principles, and honesty.” A British journalist observed that “the poor lady is loyal as steel to her family and to Lincoln the first, but she . . . has permitted her society to be infested by men who would not be received in any respectable private house.” The First Lady’s image had become so distorted that no number of admiring comments could bring it back into focus.70

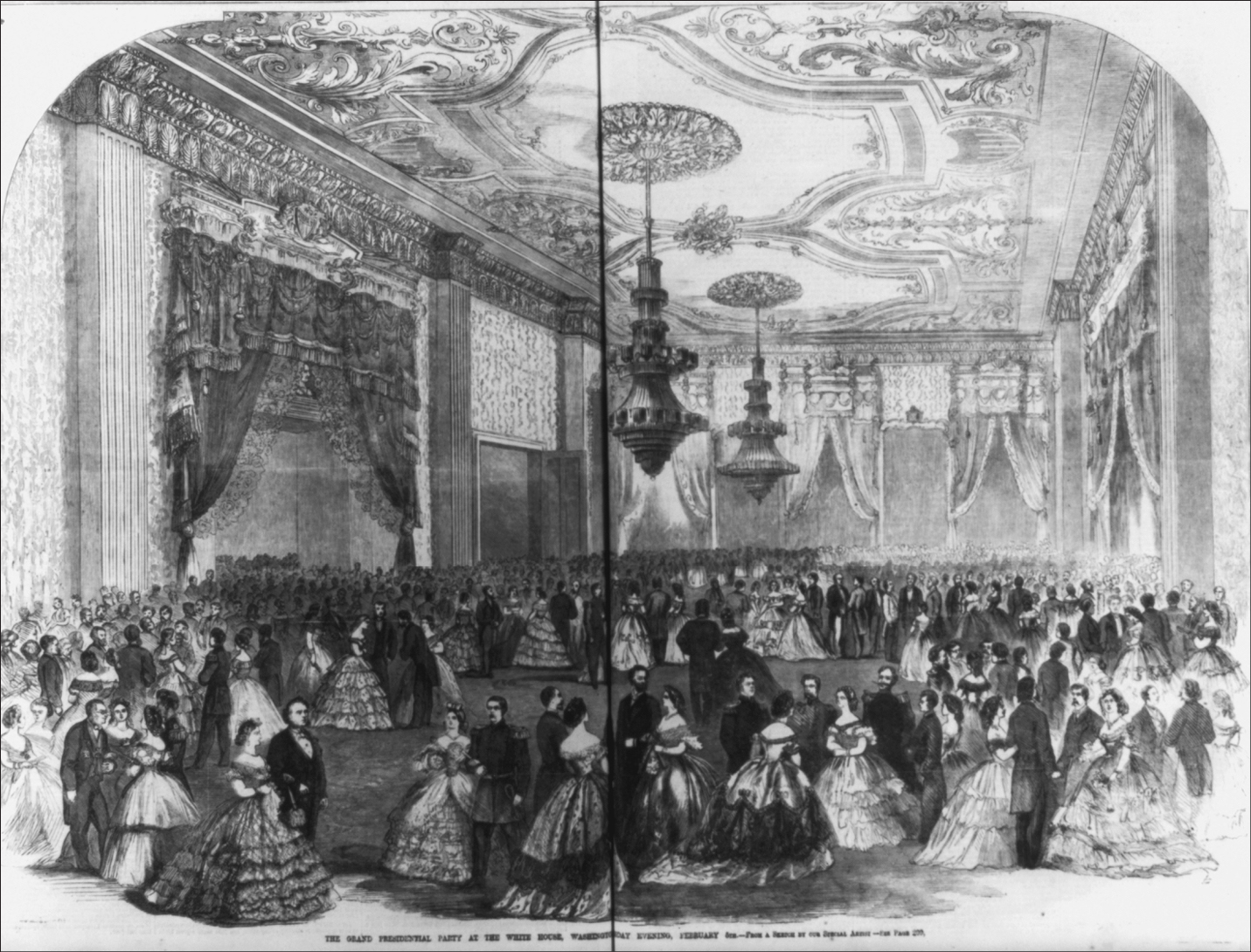

And the missteps continued. There were rounds of receptions that Mary must have envisioned in the Dolley Madison mode—elegant levees at which opponents could meet and ideas be exchanged. Her husband hated these events but did nothing to prevent them. The fact that the Executive Mansion was used to present evenings of conjuring tricks by “Hermann the Prestidigitateur” or Barnum-like displays of Tom Thumb and his bride did not elevate the reputation of either Lincoln. The unfortunate optic reached its apogee when the Lincolns gave a lavish and ill-timed ball on February 5, 1862. Refreshments included more than a ton of turkeys, pheasants, and venison, as well as spun-sugar confections in the shape of nymphs and a fully gunned Fort Sumter. Such a wartime spectacle was unseemly to say the least, and it caused a backlash in both press and political circles. “A dancing-party given at the time the nation is in the agonies of civil war!” exclaimed Henry Dawes, a Republican congressman already critical of corruption in Lincoln’s administration. “With equal propriety might a man make a ball with a corpse in his house!” Even staunch supporters boycotted the affair. The questions now were not about the First Lady’s overspending but the President’s judgment.71

“Grand presidential party at the White House, Washington, Wednesday evening, February 5th,” wood engraving,

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, February 22, 1862

Family tensions came to a head with the illness of Willie Lincoln during that ill-fated dance. By many accounts he was the most likable, and perhaps the most promising, of their boys. He and younger brother Tad had caught typhoid fever, and, despite their parents’ desperate ministrations, Willie began to succumb as the party roared below. Both Lincolns were devastated. Nicolay recalled how the President came to his room in tears; a nurse brought in to help recorded his nightlong vigils at Tad’s bedside. Indeed, the tragedy may have affected his stability. Under constant pressure from the slow advance of the war, he now made a series of extremely poor military decisions, with serious consequences. Still, he had the distraction of official business and constant company, while his wife lay in a darkened room, falling prey to self-reproach, as well as to anxiety for her sons. Although Tad recovered, eleven-year-old Willie died at five in the afternoon on February 20 in the carved rosewood bed, now known as the Lincoln Bed. Mary, already suffering from isolation and public criticism, sank to new levels of despair. Friends came to help, and she tried to relieve her mind by dabbling in spiritualism, but her once coveted position now seemed a “mockery.”72

Lincoln’s Midnight Thinky, pencil, by Charles W. Reed, c. 1862

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Perhaps she took morphine as well, for it was a popular remedy for a variety of physical and psychic ailments. More than one person thought the drug detached Mary’s mind from reality. Misfortunes only multiplied, as several Todd men fighting for the Confederacy were killed in horrible battles like Shiloh, Vicksburg, and Chickamauga. These were losses she could not mourn publicly, and “like a barrier of granite” they estranged the First Lady from her family. One sister, the widow of Southern general Benjamin Helm, came to visit; but the press was quick to resent the presence of a rebel officer’s wife in the White House, and Mrs. Helm soon retreated. Once Mary was cut off from sympathy and blasted as “the scape-goat for both North and South,” a close acquaintance remarked: “I do not believe her mind ever fully recovered its poise.”73

The double burden of grief and public pressure formed a gulf in the Lincolns’ marital relations. There is evidence that both partners tried to console each other but were handicapped by the wartime situation and their own divergent personalities. “Sister has always a cheerful word and a smile for Mr. Lincoln, who seems thin and care-worn and seeing her sorrowful would add to his care,” Mrs. Helm noted in her diary, and the President tried to find medical help and kindly friends to soothe his wife’s misery. Despondent, Lincoln became recklessly oblivious to his personal safety, complaining that the war was destroying him, and wandering alone at night without a guard. “I often meet Mr. Lincoln in the streets,” wrote State Department translator Adam Gurowski. “Poor man . . . ! [His] looks are those of a man whose nights are sleepless, and whose days are comfortless.”74 Lincoln’s imprudent outings filled his wife with fear, as did the idea that his draft-age son, Robert, might also be lost to the conflict. She became increasingly erratic, her clandestine correspondence more frequent, and swings of emotion more pronounced. Many of the President’s colleagues had not particularly liked Mary Lincoln in Springfield; now they viewed her as a dangerous interloper, incautious in her words and actions. Secretaries called her the “Hell-Cat,” and Republicans worried she was revealing sensitive information to the opposition. Her imperiousness was also noted. Although Mary could be exceedingly gracious, she often demanded special prerogatives. She also appears to have been jealous of her husband’s time and imagined he gave attention to other ladies. At a military review toward the close of the war, Mrs. Lincoln raised a fuss when an officer’s good-looking wife rode alongside the President, causing her to fear the young woman would be mistaken for the First Lady. The episode was much magnified by Adam Badeau, an aide to General Ulysses S. Grant, raising more eyebrows. Grant’s wife, Julia, who was present, later tamped it down, describing it as awkward but not a major scene. Still, it was indicative of Mary Lincoln’s volubility during these years, and her dangerous flirtation with unreality.75

In her anxiety, Mary fell into a pattern of frantic economizing, alternating with compulsive overspending. Gossips thought she starved her husband, or lowered the tone of the White House by grazing cows and goats on the lawn. Actually she tried to persuade the President to eat and sleep more regularly and orchestrated their summer moves to the Soldiers’ Home, where the breezes and political pressures blew cooler. At the same time, she made eye-popping purchases, “ransacking” jewelers and dry goods stores, inviting criticism of her self-indulgence. The First Lady was undoubtedly the prey of sharp-eyed merchants in Washington and New York; and the problems were compounded by Lincoln’s inattention to household finance. However, this kind of aberrant behavior also bespoke her fear of destitution and desire to escape through compulsive spending. After her eldest son, Robert, joined the Army the wild splurges increased. Toward the end of the war, Mary bought eighty-four pairs of kid gloves and $3,200 worth of jewelry within a few weeks. Some believed she had also begun to steal objects. At the time of Lincoln’s death, she was $25,000 in debt—as much as his yearly salary.76

More grief would come to Mary Todd Lincoln, as each of her worst nightmares came true: her husband murdered before her eyes; her kin and eldest son estranged; Tad succumbing to death while in his teens; and the horrid specter of poverty slowly tightening its grasp. Her eyes, once universally described as “sparkling,” became dull with the inability to absorb more disaster. Yet her descent into darkness, destructive as it was to her family and to herself, was never malicious. To read her life’s correspondence, with its shattering chain of sorrows, is to be moved more to pity than to disdain.77

V