6

THE HOLLOW CROWN

The man on the wharf wore a baggy coat of rebel gray and carried a stick as tall and tough as he was. Some who saw him thought he looked scruffy and dangerous, but to others, Duff Green seemed almost a mystical apparition: a white-haired, wispy-bearded, sharp-eyed prophet come to warn that pride and defiance lingered in the smoldering ashes of the Confederate cause. It was April 5, 1865, two days after the fall of Richmond. Green intended to board Admiral David Dixon Porter’s flagship, the USS Malvern, which was moored on the James River, downstream from the occupied city. He had a pass from the military governor allowing him through the lines, and he had a few words to say to the President of the United States, who was on the ship.1

Porter was concerned about the old man’s “uneasy, restless look” and he was worried about that stick, which he called a “club . . . big enough to knock a house down.” But Abraham Lincoln knew Duff Green and allowed him to enter the presidential cabin. Green, a Kentuckian, had lived and taught in Elizabethtown during the years that Lincoln’s father did carpentry work there and was, in fact, related to the President by marriage (both Lincoln and the nephew of Green’s wife, Ninian Edwards, married Todd sisters). When Lincoln was elected to Congress, he boarded at the Greens’ lodging house on Capitol Hill. Although their politics increasingly diverged, the two men maintained a cordial friendship and shared an interest in promoting public works to develop the nation’s potential.2

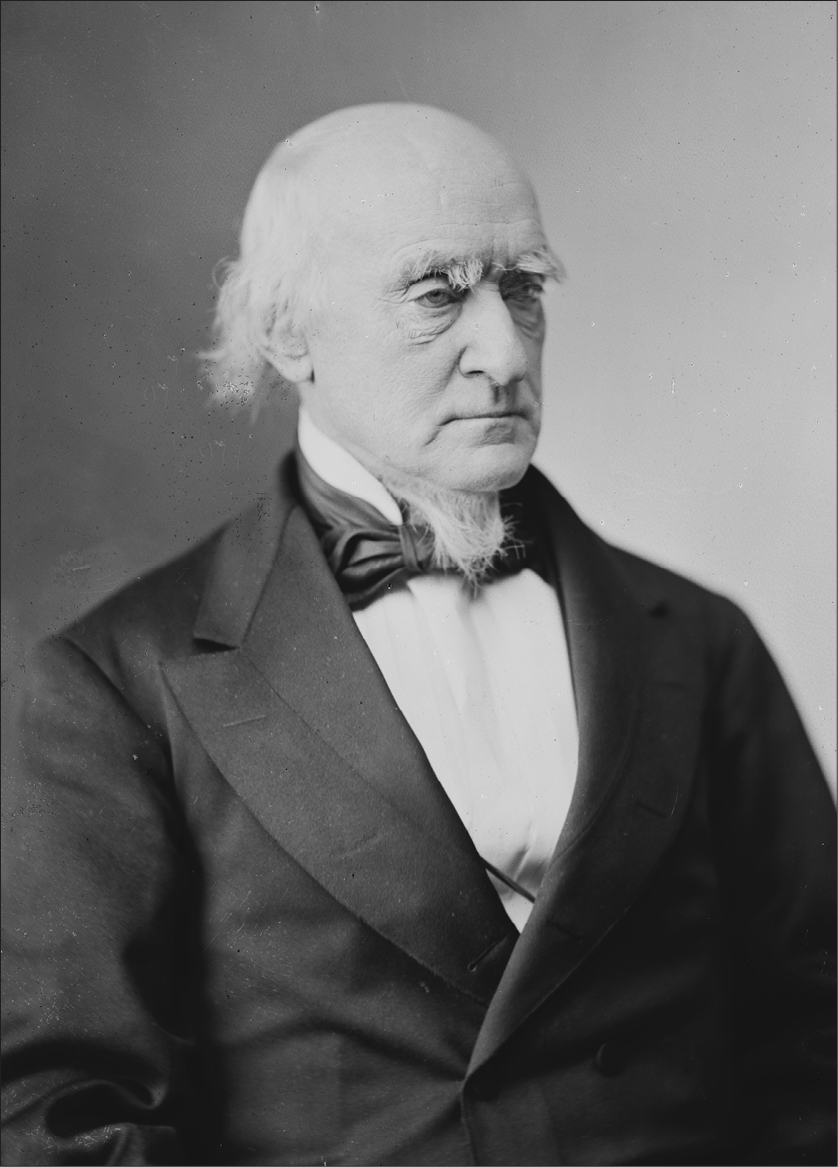

At a time when Lincoln was still learning the congressional ropes, Green was a near legendary figure in the capital, epitomizing the energy, opportunity—and sometimes the violence—of America’s turbulent society. He had been by turns a surveyor; a lawyer; a representative to Missouri’s 1820 constitutional convention, and to both houses of the state legislature; a brigadier in the militia; the owner and editor of several influential newspapers, including the St. Louis Enquirer and United States Telegraph; a member of Andrew Jackson’s “kitchen cabinet”; and the special agent of President John Tyler in Europe and Mexico. Excited by the extraordinary chances to make money in America, Green also organized numerous industrial enterprises. He was an early Southern sectionalist, backing nullification in the 1830s and joining secret societies such as the Knights of the Golden Horseshoe, which hoped to extend Southern interests throughout the Caribbean basin. He shunned secession, however, and hoped to unify and develop his region within the structures of the United States.3

USS Malvern, photograph taken near Hampton Roads, Virginia, December 1864

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

In politics Green could be as fiercely partisan as Lincoln, zealously backing John C. Calhoun and other Democrats, particularly as a newspaperman. His unrestrained editorials won applause from those sharing his views, as well as from advocates of a free press. But in the vitriolic politics of the day, the heated commentary sometimes brought on public clashes. In the late 1820s, Green attacked a rival from the Daily National Intelligencer on the Senate floor and reportedly gouged out his eyes. On another occasion, when James Watson Webb of the New York Courier challenged him, Green pulled a gun, forcing Webb to run for his life into the Capitol. Most famously, he so incensed Congressman James Blair of South Carolina by repeatedly referring to the Union party as “Tories” that the 350-pound Blair assaulted him in the street, kicking him into the gutter and jumping on him until he had broken Green’s arm, collarbone, and several ribs. After this incident, Green semiretired from the journalistic world and acquired his well-known stick. It was a prop he would employ with some drama, until at age seventy-four he finally broke it while beating a man who had insulted him in a railroad car.4

Green joined his ardent political agenda with an equally ambitious pursuit of entrepreneurial schemes. He gained exclusive contracting privileges for canal construction, and underwrote the rebuilding of Norfolk’s Gosport shipyards, which the British had destroyed during the Revolution. Using his considerable influence, Green gained lucrative government contracts for the yard to produce naval vessels, among them the USS Powhatan, which Lincoln had attempted to use for the resupply of Fort Sumter. Once railroads became state-of-the-art technology, Green was indefatigable in their promotion. Believing Northern industrialists were wresting away the advantage in transportation, mining, and land development, he worked to expand competing Southern systems. In the 1850s he laid plans for a line that would link Washington and New Orleans via the rich valleys of Virginia and Tennessee, and another from Washington to Mobile, through Richmond, Raleigh, and Atlanta—essentially the routes still used today. From the state of Texas he obtained more than ten thousand acres of land and a loan of six thousand dollars per mile for a network of freight roads. Increasingly worried that Northern “fanatics” would wage an “unholy war” on slavery, Green saw economic expansion as the key to maintaining Southern power. Disunion was not the answer, he told the governor of Alabama. “Our only hope lies in this. . . . We must develop our resources and . . . increase the profits of labor by diminishing the expense of transporting its products to market. . . . Give us good Roads, and union & concert and we need fear no danger.”5

Green particularly trained his eye toward the Pacific, hoping to strengthen the Southern states by joining their interests to the West. By the tense election year of 1860, he had formulated the most cogent scheme to date for a railroad stretching to the state of California. Working with the president of Mexico, Green obtained charters for a line linking Vera Cruz to the Pacific by way of Mexico City, which he planned to connect to his Texas roads, as well as to the New Orleans line. Approval for this project gave him capital to acquire mining rights and to attract further investment for the transcontinental venture. On the eve of war, Green finally knit together a complicated coalition of states and individuals interested in supporting the project, with a holding company in Pennsylvania. The future looked bright as he envisioned a railroad that would extend the Southern way of life, increase trade and immigration, and link the region’s ports to Europe and the mineral wealth of Mexico. Best of all, it could be constructed with cheap slave labor, something Northern investors understood to be a distinct advantage of the southerly route. It was “no small triumph to have devised the means of building the first road to the Pacific,” Green justifiably boasted to his wife. The pearl of American promise was within reach; he had only to open the oyster.

Then Abraham Lincoln was elected president—on a platform that expressly threatened plans to extend Southern interests into the western territories.6

When Duff Green stepped aboard the Malvern, he meant to deliver a lecture and offer a proposal. His lecture addressed what he saw as Lincoln’s chronic misunderstanding of the South—a perpetual tone deafness that had been present since before the inauguration. Depending on which version of the encounter is read, Green delivered his speech forthrightly, but politely; or with a kind of unleashed fury that had Porter calling for his sailors and Lincoln returning insults, his coarse hair standing on end “and his nostrils dilated like those of an excited race horse.” Green was certainly capable of the capricious act, and Lincoln too could lose his cool with gusto. Still, it is hard to believe completely Porter’s account of Green threatening with his stick, and accusing the President of playing the tyrant, with Lincoln responding that Green was nothing but a “political hyena” whose prejudices had unleashed the rebellion. Porter has the interview ending with the chief executive melodramatically shouting: “Miserable imposter! vile intruder! . . . Go, I tell you, and don’t desecrate this national vessel another minute!” For his part, Green recalled that he took special care to be respectful, that Lincoln received him kindly, and that their conversation had been candid. Another eyewitness, former Supreme Court justice John Archibald Campbell, later wrote that he was present at the beginning of the interview and observed “no intemperate language, nor indecorous deportment on [Green’s] part, or of exasperation on the part of the President.” One of Lincoln’s bodyguards claimed to have seen an angry Green, incensed at the “notorious crime of setting the niggers free,” refusing to shake hands. None of these stories ring entirely true, since all were penned by participants who were under pressure, or looking for self-justification, when their accounts were written. Most likely the meeting was a tense one, with Green expressing himself in characteristically colorful style to a weary president who was out of patience with harangues from men he had now virtually vanquished.7

Nonetheless, Green had a point to make, and it was not a subtle one. Ultimately he wanted to know how Lincoln intended to deal with the collapsed Confederacy, but his immediate concern was the impression the President had left on a visit to Richmond the previous day. For several weeks Lincoln had been accompanying the Union Army and Navy in its final struggle to capture the rebel capital. His tour of the city, almost immediately after its capitulation, capped weeks of anxiety, as Lee’s men fell back. The war was not yet over—Appomattox was four tense days away and Joe Johnston still stood his ground in the Carolinas—but it had become increasingly clear how the contest would end. Lincoln had witnessed sights both grisly and inspiring in recent weeks, and his mood seemed to swing between nervous apprehension and buoyancy over a victory now within grasp.8

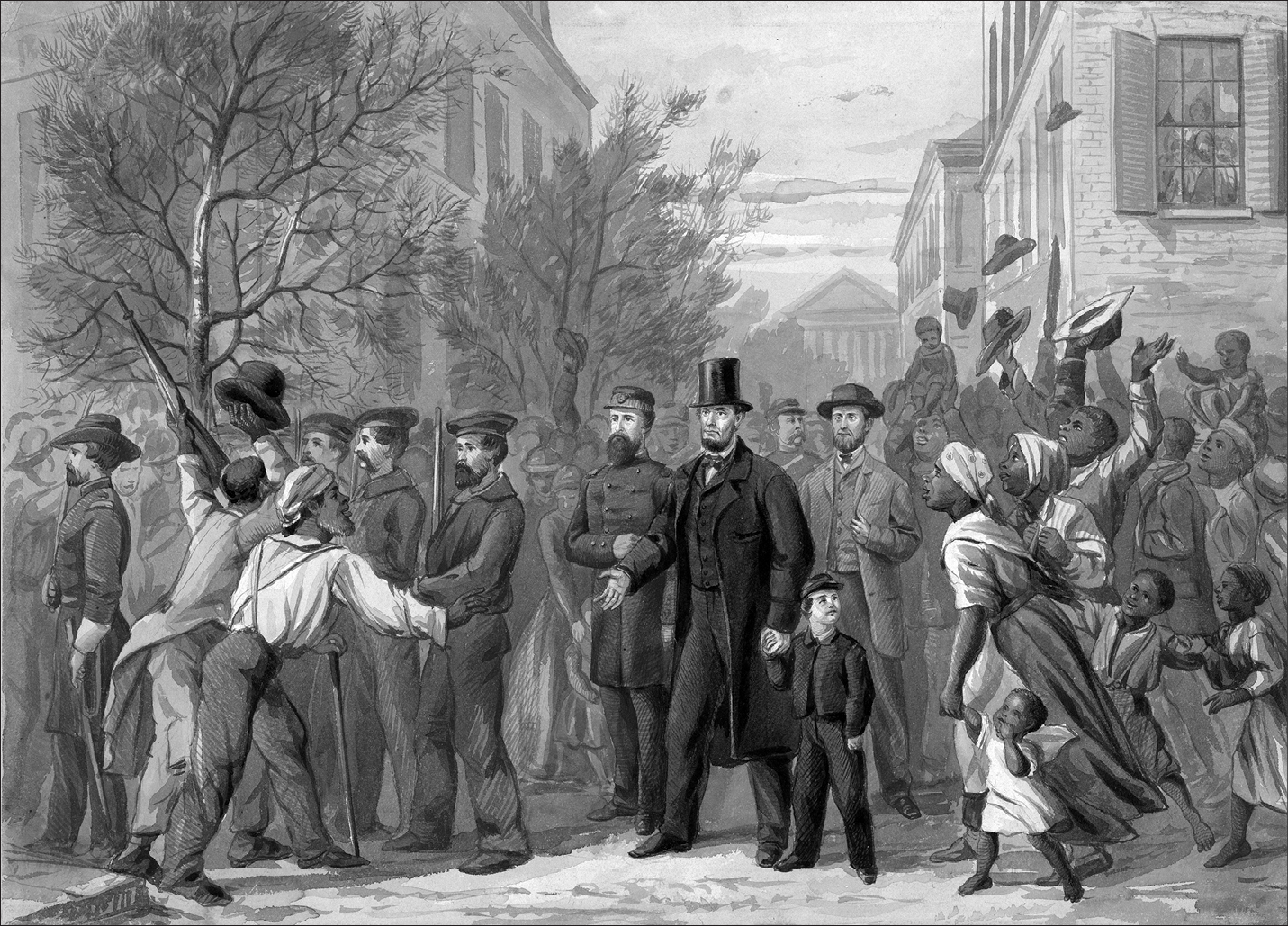

Lincoln in Richmond, pencil, by Lambert Hollis, April 4, 1865

NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY

Although he had been invited to the front by Grant, the top military men were also agitated. They had been handed additional responsibilities when Lincoln’s demanding wife arrived, with young Tad in tow; but their main worry was for the President’s safety. Lincoln had enjoyed the action scenes, and he had reportedly even teased Porter into making the Malvern’s presence known, so it would flush out some rebel fire. In Richmond the commander in chief walked openly through the streets, while Porter called agitatedly for an escort, and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton wrung his hands back in Washington. Even the New York Times, which normally backed Lincoln, thought the exposure unwise. “If President LINCOLN has ‘gone to the front,’ or entered Richmond, he has departed widely from the discretion and good judgment which have hitherto marked his conduct,” the editors opined. “He has no right to put [himself] at the mercy of any lingering desperado in Richmond, or of any stray ballet [sic] in the field, unless some special service can be rendered by his personal presence. It seems to as he might have left to Gen. GRANT the closing up of the great campaign.”9

Prudent or not, Lincoln arrived in Richmond just hours after the Union cavalry galloped into the old city square and raised the Stars and Stripes above the seat of Confederate government. African American troops had been at the front of the procession, pride in their step, their exultant huzzahs filling the air. They found a city blanketed by a haze of red smoke so thick it blotted out the sun, with the populace reeling in stunned disbelief. Signs of defeat had been growing for weeks, but no one had really thought the Yankees could dislodge Lee. Now the highest officials had fled the capital, burning tobacco warehouses, detonating arsenals, and blowing up gunboats to keep them from Union hands. “The city was in a state of indescribable consternation,” reported the French consul. “The silence which precedes great events was terrifying.”10 Then the fires spread through the town into business and residential districts, forcing many to take refuge with a few scanty possessions on the Capitol lawn. Boulevards and alleys were covered with pulverized glass from windows shattered by the explosions; and down the center of the streets ran long, smoldering piles of paper, “torn from the different departments’ archives . . . from which soldiers in blue were picking out letters and documents that caught their fancy.” Worse, the retreating army had smashed open stores of whiskey, meaning to destroy them before the liquor could enrage the invaders, and a rabble both white and black was scooping it from the gutters with pitchers and hands. In fact, wrote one Union occupier, “its contaminating influence came very near making me drunk, the air smell[ed] like the bung of a whiskey keg.”11 Chaos, alcohol, and distress led to boisterous behavior, including looting and unearthly screaming. One shocked citizen described how a “gang of drunken rioters dragged coffins sacked from undertakers, filled with spoils from the speculators’ shops,” while howling madly. It was one of the most chilling sights of the war, reported another eyewitness: “a city undergoing pillage at the hands of its own mob, while the standards of an empire were being taken from its capitol, and the tramp of a victorious enemy could be heard at its gates.” Through it all crowds of African Americans, of every age, streamed into the city, loudly celebrating their liberation. One day later, on April 4, the President of the United States waded into this pandemonium.12

It was an almost overwhelming day. Lincoln had come with Porter by boat up the James River, through a landscape littered with destroyed rebel ships and the carcasses of dead horses. Twice the group had to change boats to pass by obstructions, and the presidential flotilla was partly conducted in rowboats. A Union vessel under David Farragut’s command had been caught in the shoals and the group was grounded again when Porter tried to help his comrade—an embarrassing moment for two admirals in the presence of their commander in chief. Always there was the threat of undetected torpedoes in the water. It was early afternoon before the party (which included Tad, celebrating his twelfth birthday that day) landed on a sandbar in a seedy section of town and began clambering up a steep hill into the city. The sight must have been extraordinary: smoking, half-crumbled façades; hot, sooty, choking air; the detritus of a fallen nation. There was no one to greet the President, and Porter, nervous for his safety, had only a few Marines to accompany him. Then, suddenly, there was a shout from a group of African Americans who were repairing a bridge close to the landing. Someone—likely a reporter named Charles Coffin, who was standing nearby—told the group that the lanky man in the long black coat and top hat, stepping off a modest launch, was Abraham Lincoln.13

A spontaneous jubilation began, creating one of the most extraordinary scenes in American history. As Lincoln and the small group climbed the hill and walked through the devastated cityscape, black women and men joined a growing throng. The city’s newly freed people had been celebrating for days, pouring into the streets to shout and sing and dance for joy at their emancipation and to salute the U.S. Colored Troops who occupied much of Richmond. Part of the elation was that they were able to move freely in the city at all, for among the fetters of bondage were restrictions on where slaves could go and whom they could meet. “We uns kin go jist any whar—don’t keer fur no pass—go any whar yer want ’er,” one overjoyed freedman told a journalist from the New York Herald, who recorded the dialect. “Golly! de Kingdom hab kum dis time fur sure.” As the presidential party moved toward the former rebel capitol, the crowd grew, some turning handsprings, some praising Lincoln as if he were Moses or the Messiah, many trying to touch his boots or shake his hand. “They received him with many demonstrations that came from the heart,” noted a member of the Twenty-Ninth Connecticut, a U.S. Colored Regiment, “thanking God that they had seen the day of their salvation, that freedom was theirs, that now they could live in this country, like men and women, and go on their way rejoicing.” George Bruce, a reporter who described the unaffected outburst in his diary, called it the “wildest spectacle ever seen,” with people throwing hats and clothing into the air, then “throwing themselves flat upon the ground and remaining there for some seconds” in a “species of demonstration or worship.” The sight of Lincoln, holding Tad’s hand as he moved wearily up the hill in the center of the crowd, noted Bruce, was “one of the most remarkable in history.” Porter, nearly frantic at the possibility of being crushed by the mob or becoming targets of an assassin, waved the flat of his sword “lustily” and was much relieved when they encountered General George Shepley, the newly appointed military governor, near Capitol Square.14

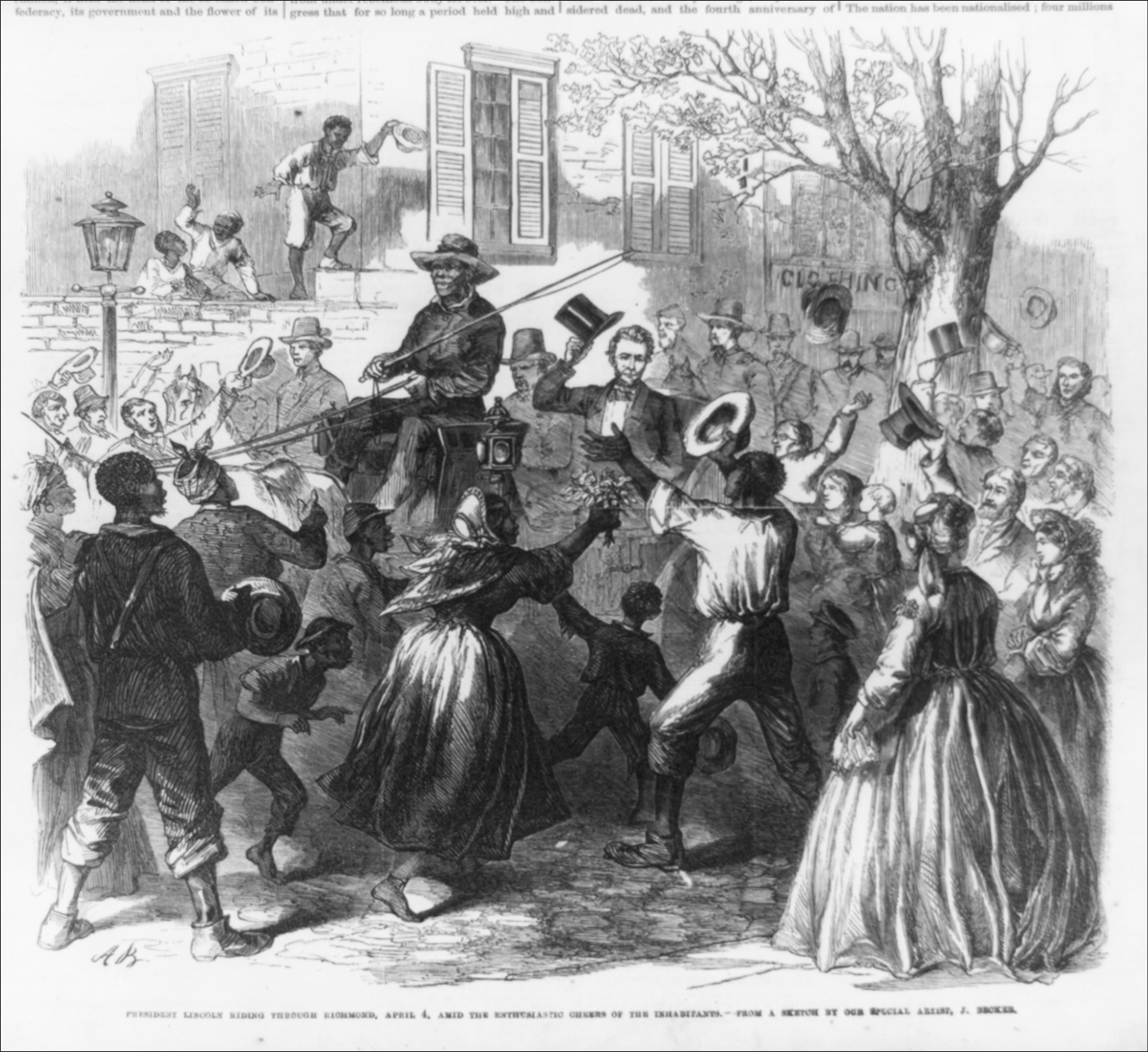

“President Lincoln riding through Richmond, April 4, amid the enthusiastic cheers of the inhabitants,” wood engraving,

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, April 22, 1865

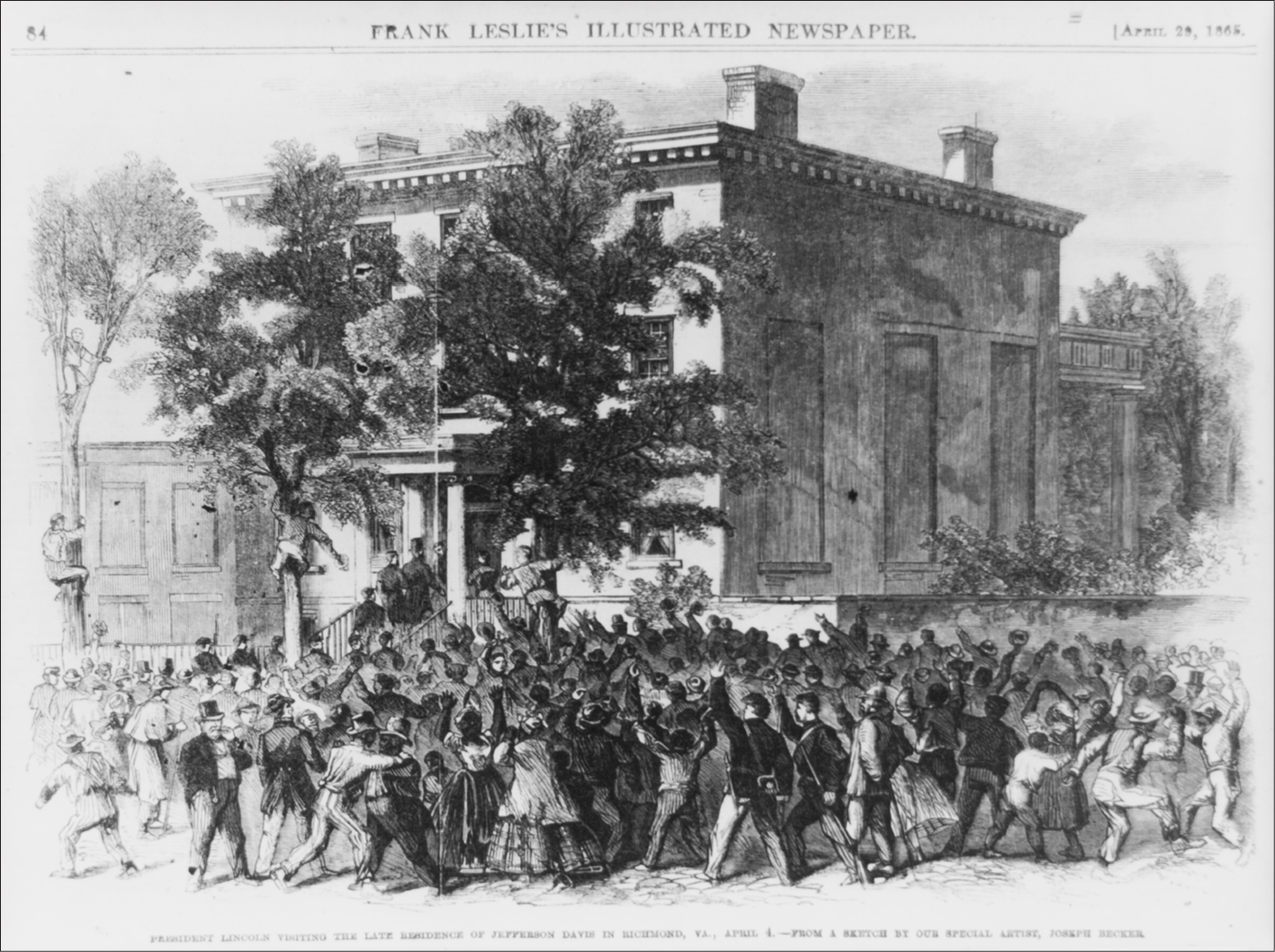

“President Lincoln visiting the late residence of Jefferson Davis in Richmond, April 4,” wood engraving,

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, April 29, 1865

Shepley and other officers escorted Lincoln to their headquarters in the White House of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis’s former seat of power. An exhausted Lincoln sank into a chair—Davis’s old desk chair, according to some—and consulted with the generals. A few prominent men who had not fled arrived to sound out the President on his plans for peace. Some witnesses reported that Lincoln wrote dispatches, toasted Union success with a sherry flip, and wandered over the house with boyish curiosity and glee. Others stated he addressed a crowd of former slaves in front of the mansion, telling them they were as free as he, and “had no master now but God.” Exactly what transpired is not clear, but certainly Lincoln, who had been through a week of extreme tension, was awed by the magnitude of what he was witnessing, and emotionally worn out. Around 4:35 p.m. the Malvern arrived at Richmond’s wharves and fired a thirty-five-gun salute, signaling to the citizenry that they had an extraordinary visitor. Lincoln and Porter then climbed into a small, two-seated military wagon, drawn by four horses, with Tad on his father’s lap, and a clattering horse guard following. Moving briskly, they toured what was left of the once noble heart of the Confederacy, passing Thomas Crawford’s heroic statue of George Washington, the elegant Capitol designed by Thomas Jefferson, the ghostly burnt mansions, the old slave auction rooms, and notorious Libby Prison. All the while, they were surrounded by a weeping, cheering, exultant African American crowd. At one point the President’s party hastily retreated from an encounter with the sorry-looking funeral cortege of Confederate general A. P. Hill, who had been killed two days earlier near Petersburg. Sometime around 6:30 p.m. the entourage reached the wharf and boarded the Malvern, for the return trip to the Union base at the village of City Point.15

It had been a memorable, raucous, and risky day. What lingered was the image of those ecstatic freedmen and -women, so grateful for their liberation, and so hopeful of better prospects. A few working-class whites had joined the procession—what one stylish matron called “the low, lower, lowest of creation”—but for the most part the white population had remained purposefully absent from the scene. Many found the display of black enthusiasm distasteful or frightening. “I wish you could have witnessed Lincoln’s triumphal entry into Richmond,” sniffed Mary Custis Lee, who still believed her husband would be victorious. “He was surrounded by a crowd of blacks whooping & cheering like so many demons there was not a single respectable person to be seen.” Some Richmonders were too overcome to enter the streets and “kept themselves away from a scene so painful,” or they were too angry to acknowledge Lincoln with their presence. One woman reported remaining at home during the procession sobbing “Dixie” into her pillow; a minor bureaucrat, finding himself so agitated he could not write, went out to see what was happening, but “ran into so many Negroes and Negresses there that I couldn’t stand it. I went home, heartbroken.” The white population was wary but also curious, and they surreptitiously watched the scene from behind half-closed shutters or lowered blinds. One blue-coated cavalryman reported seeing as many as sixteen faces peering through a single window. “You know Lincoln came to Richmond Tuesday the 4th and was paraded through the streets,” whispered an unreconstructed rebel. “The ‘monkey show’ came right by here, but we wouldn’t let them see us looking at them.”16 There were Northern sympathizers in Richmond, people like Elizabeth Van Lew, who had hoarded tiny flags and secretly sung “The Star-Spangled Banner,” and even gathered intelligence for federal authorities. But no great contingent of closet Unionists came forth and the few who did only earned the scorn of their neighbors. Although the city was in desperate straits, there was little gratitude that an end to the long, dreadful ordeal had finally come. And virtually no respect was paid to the leader of the hated Yankees.17

Devastated by the collapse of their cherished hopes and smarting under the rebuke to their arrogant assumption of Southern fighting superiority, the white population also deeply resented the presence of so many black faces in blue uniform. Many thought the gesture unnecessary and impolitic, though even the most bitter admitted that the Union occupiers had conducted themselves well. (Federal soldiers had worked diligently to put out the fires, quickly establish order, and overall acted with discretion and courtesy.) What rankled was the fact of Lincoln’s arrival in Richmond—a humiliating sign that Virginia was now under “the policy of the conquerors.” From their perspective, the poky presidential contingent was little short of a triumphal tour by a despised tyrant.18 Lincoln undoubtedly felt he was entering the city as a peacemaker—numerous accounts of his conversations at this time show him earnestly advising others to “judge not” and to seek a speedy route to reunion. Perhaps he was hoping his presence in the fallen capital would reassure the public that he meant conciliation, or even to win them over with his unpretentious manner.19 But the spectacle of the small group struggling up the hill on foot, surrounded by a shrieking black mob, or dashing through the city with cavalrymen thrusting the public away with brandished bayonets only reinforced everything Southerners abhorred. A few who peered through those shuttered windows glimpsed only an old, tired man, but most saw the specter of their worst fears: military subjugation and uncontrolled bands of Negroes roaming the city, all at the hands of a undignified jokester. The sight of “these people in Richmond” had made him physically ill, wrote one man; another, who had escaped the city, but heard of Lincoln’s visit from former governor “Extra Billy” Smith, mused: “I wonder how gentlemen can avail themselves of the misfortunes of the people they have been fighting, by such selfish & ungallant intrusions upon their private rights. . . . [I]t sickened my heart to think of the humiliation inflicked upon the people of my own state.”20

Worse was the gossip about tactless conduct by the presidential party. Rumors of Lincoln’s gleeful lounging in Davis’s chair—or sleeping in his bed—were quickly whispered from person to person, as were reports of the “disgusting sight” of him familiarly shaking hands with black men or drinking toasts over the burning bier of the Confederacy. The “indelicate” visit of Mary Todd Lincoln and Julia Grant two days later only rubbed salt into the wound. “It is said that they took a collation at . . . our President’s house!!” exclaimed a woman who had been one of the war’s first refugees. “Ah! it is a bitter pill. I would that dear old house, with all its associations, so sacred to the Southerners . . . had shared in the general conflagration.” Most of the stories were embellished, often with each retelling. Still, the evidence indicates that Lincoln had indeed indulged his curiosity to see the fallen Confederate capital; had put his feet up and his guard down while there; had risked his own safety, and that of his young son, and with it the stability of the government; and was in high spirits, perhaps understandably given the relief and excitement of the moment. Mrs. Lincoln, too, seemed less than discreet in her conduct, playfully asking friends if they would not like to “dine with us, in Jeff Davis’ deserted banqueting hall?”21 In the end it was not really important whether or not the tales were true—it was the perception that mattered, and at that moment it mattered greatly. A mighty war was ending and with it the collapse of an empire and a way of life. Just as Lincoln was contemplating what policies to pursue with the defeated rebels, Southerners were also deliberating their future course. The perception they got from Lincoln’s excursion in Richmond was of an unwise victor, chuckling over his spoils in a most offensive manner. As always, humorist David Ross Locke, lampooning the visit a few days later, captured perfectly the tone of popular disgruntlement. “Linkin rides into Richmond! A Illinois rail-splitter, a buffoon, a ape, a goriller, a smutty joker, sets hisself down in President Davis’s cheer, and rites dispatches,” cried his character Petroleum V. Nasby. “Where are the matrons uv Virginia? Did they not bare their buzzums and rush onto the Yankee bayonets . . . rather than see their city dishonored by the tread uv a conkerer’s foot? Alars!” To many Southern minds, this sideshow would define their future reality.22

Duff Green had also heard the gossip from “Extra Billy” and General Shepley, an old friend, who had given him the pass to the Malvern. He was well aware of the way Richmond had reacted to Lincoln’s visit. Porter maintained that this prompted Green’s shipboard call, as well as how he addressed the President rudely, calling Lincoln a “Nero” who had come “to triumph over a poor conquered town, with only women and children in it; whose soldiers have left it, and would rather starve than see your hateful presence here.” Whether Green attacked Lincoln as Porter insisted, or merely stated in his pointed style that this was not the way to sway the hearts and minds of bitter Confederates, is not clear. But Green admitted his purpose was to influence Lincoln’s thinking on postwar treatment of the South, and that he believed the chief executive was veering dangerously from reality, particularly in the treatment of ex-slaves. Lincoln, he maintained, was using his best wits to determine how to win over the former rebels, but acting in a manner that had the opposite effect—and not for the first time.23 It appears the President was already aware of the unfortunate optic of his tour, however. He discussed it with General Marsena Patrick about the time Green came on board; and with the First Lady’s favorite the Marquis de Chambrun and Charles Sumner, who accompanied his wife to the town a few days later. The reception, with the leading citizens “in total eclipse,” had not been a good omen, he told the Marquis; and Sumner noted that “he saw with his own eyes at Richmond & Petersburg, that the only people who showed themselves were negroes. All the others had fled or were retired in their houses.” Both Chambrun and Sumner left Lincoln’s room admiring his goodwill, but concerned for his naïveté. “I am very unhappy,” Sumner confessed to Salmon Chase, now chief justice of the Supreme Court, “for I see in the future strife, & uncertainty for my country.” The President, he worried, had not the disposition to make cogent plans and “follow them logically & courageously.”24

II

The brief encounter on the USS Malvern was not the first time Duff Green had given Lincoln a prophesying message. In the nervous weeks following South Carolina’s secession, Green had been sent by President James Buchanan to Illinois to invite the president-elect to come immediately to Washington. Buchanan knew the two men were connected and hoped that Green’s forceful manner, and his own pledge that Lincoln would be treated with honor, might persuade the president-elect to dispense with tradition and party politics long enough to unite in a platform of peace. On December 28, 1860, Green had what he termed a “Special Interview” at the Lincoln home in Springfield. He carried with him a copy of the recently passed Crittenden Compromise, a last-ditch effort by Kentucky senator John Crittenden to thwart war. The plan extended the line of the Missouri Compromise to the Pacific Ocean, prohibiting slavery north of the 36°30' parallel, and addressed Southern concerns about enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act. It also guaranteed that slavery would continue where it already existed. Hoping Lincoln would endorse Crittenden’s work, Green tried to impress him with the urgency of the situation, as well as the intensity of Southern fears. Lincoln had been elected, he noted, by a minority vote from a single region. That rankled Southerners, who felt they had become a “subject province, conquered by the ballot-box.” Dismissing abolitionists as little more than a honking gaggle of fanatics, Green recited the familiar pro-slavery arguments about paternal master-slave relations, topping it off with pseudo-biblical warnings against conflict between labor and capital, or among weak and strong states. Green spoke passionately, for, as he later noted, the moment was opportune, never to come again.25

But Lincoln was cautious. Green later stated that at first he responded positively to Buchanan’s invitation, then backed away, saying he was obliged to wait in Springfield for a visit from hard-line Republican Benjamin Wade. Lincoln thought Crittenden’s compromise might quiet agitation for the time being but believed slavery was only the current pretext in a power struggle that would quickly erupt again, over questions like the possible annexation of Mexico. The real issue, noted the president-elect, was one of “propagandism”—a war of words that had mushroomed on both sides until fears outpaced realities. He had been elected by his party, said Lincoln, and he intended to stick with it; but added that questions such as the Crittenden Compromise or any legislation prohibiting interference with slavery belonged with the people and the states. If such legislation should pass, “he would be inclined not only to acquiesce, but to give full force and effect to [the] will thus expressed.” Green asked Lincoln to put his thoughts in a message that could be published and he did so, in a wordy letter drawing on party-platform language about the “inviolate” right of a state “to order and control its own domestic institutions.” In the end, the president-elect shied away even from this qualified statement, adding an impossible condition that the document could not be published unless half the senators from the Deep South concurred with it in writing. Green returned home empty-handed. “I saw and had a frank conversation with Mr. Lincoln,” he later reported to Jefferson Davis, “but found it impossible to convince him of the dangers of the impending crisis or the necessity of his intervention.” To the president-elect, Green left a warning: “he alone could prevent a civil war, and that if he did not go [to Washington], upon his conscience must rest the blood that would be shed.”26

Duff Green was hardly a disinterested emissary—he not only abhorred secession but had his own entrepreneurial projects at stake, which were destined to fail if the nation divided. However, he was not the only Unionist urging Lincoln to send the country a message that would allay panic. From both North and South, the president-elect was entreated to make a succinct declaration of his commitment to the nation as a whole, and his intention to uphold the principles that bound it together. The moment was unimaginably tricky, for the factions were so polarized that guarantees sought by one section only enflamed others. “The eyes of the whole nation will be upon you while unfortunately the ears of one half of it will be closed to any thing you say,” Lincoln’s close friend Joshua Speed advised him. “How to deal with the combustible material lying around you without setting fire to the edifice . . . of which you will be the chief custodian in is a difficult task.” Some, like North Carolina Unionist John Gilmer, believed it was the Republicans’ duty to defuse the crisis, and wanted Lincoln to lay out his program specifically, on sensitive points such as emancipation in Washington, D.C., or whether Congress had authority to interfere with slavery in the states. Others criticized Buchanan’s mixed message regarding secession (he declared it nothing short of revolution, but believed he had no power to prevent it), urging Lincoln to speak firmly against the Fire-Eaters, quashing any notion that he would tolerate their challenge to national unity. When he did so, advised one supporter, the president-elect should mark his words with “the thunder of brevity.”27

Montgomery Blair, seen as an uncompromising Republican, went so far as to query Supreme Court justice John A. Campbell about the precedent of a statement from the president-elect. Campbell, a Southerner who hesitated at secession, thought the measure would be extraordinary but not unconstitutional, and perhaps might forestall a tragedy based on misunderstanding. Republican power brokers William Seward and Thurlow Weed also saw that the stakes had changed since the election. Their party had won largely because of a three-way split among Democrats rather than a clear consensus of the voters, and the urgent questions were no longer those posed in the antislavery Republican platform, but the ones inherent in the nation’s crumbling stability. They believed their party’s job now was to pull back from brinkmanship and restore the Union. “I want to meet Disunion as Patriots rather than as partisans—as a People rather than as Republicans,” Weed told Lincoln a few days after South Carolina seceded.28 But the majority of the president-elect’s compatriots urged him to hold fast to party and platform. A weak-kneed retreat from policies that were approved at the polls would look defensive at best, they argued, and might signal that the government was unable to defend its institutions, emboldening the South to make more aggressive demands. Moreover, there were legitimate ideological issues, which should not be compromised.29 Congressman Samuel R. Curtis put the dilemma clearly:

We cannot as republicans shrink back from the principles we have advocated and the people have approved. We might declare as we have done a thousand times that we have made no war on the South and will make none on their institutions . . . ; but for us to say as they desire that slaves are property and must be so regarded under the Constitution we cannot say it because we do not believe it[.] Neither can we say that slavery is a moral or political blessing because we do not believe it.30

For his part, Lincoln had made up his mind before the election that it was not only unseemly but useless to offer concessions. He probably knew through long political experience that his position was a weak one. He had been elected despite an unprecedented boycott of his candidacy in the South, and in that section he was considered illegitimate. Moreover, the Electoral College would not meet until mid-February, and until it pronounced him president he had no official status. Lincoln had long since come to the conclusion that Southerners were not listening to him; were, in fact, willfully deaf to protestations that he was a conservative man, with no intention of meddling in the internal affairs of slave states. He had said as much ten months earlier in his address at New York’s Cooper Institute and he reiterated it the day before the election to a visitor who suggested he make an overture to honest Southern men who were genuinely alarmed. “There are no such men,” Lincoln curtly told him, while his secretary took notes. “It is the trick by which the South breaks down every northern man.” “Honest” men, he protested, would read his numerous public statements and see that they had nothing to fear. Repetition would change nothing. “Having told them these things ten times already, would they believe the eleventh declaration?” The president-elect told Duff Green that, in any case, he was personally more comfortable with silence—“whether that be wise or not”—and he preferred to watch and wait and let passions die down. It was as if he was back in the days of his youth, sizing up his wrestling opponent Jack Armstrong; taking care to avoid showing weakness; watching for the chance to disarm him—and hoping to find common ground to overcome animosity.31

But the situation was not as clear-cut as a young man’s wrestling-ring show of strength. Lincoln was also concerned that compromise would alienate his supporters and send him to Washington “as powerless as a block of buckeye wood.” He was bound by fundamental Republican ideals and goals and by the party’s successful drive to promote policies that much of the North and West supported. It was, in fact, exactly what Southerners feared: a sectional party, representing the aspirations of modest farmers, craftsmen, and local businesses. The interests of these small-scale capitalists differed from those of ambitious entrepreneurs like Duff Green, Dixie’s large agricultural enterprises, and even the Southern yeomen who were indirectly dependent on the plantation system. The issues were not limited to slavery, but ranged from tariffs to turnpikes; and many were intrinsically linked to Southern dreams and Southern identity. In general, Republicans supported free labor rather than the chattel arrangements that helped make the Gulf states so prosperous, but that did not mean the party was uniformly emancipationist. The 1860 platform upheld the right of states to control their own “domestic institutions” and, in any case, as New York Tribune editor Horace Greeley admitted, most Americans would “only swallow a little Anti-Slavery in a great deal of sweetening.” Yet it was the issue of slavery’s expansion that gave form and flavor to Republicanism—what Lincoln called “its active, life-giving principle.”32

Within these terms, Lincoln was considered a moderate. He did not agree with abolitionists who thought the eradication of slavery was more important than maintaining the country’s unity, nor did he side with those who believed every possible concession should be made in order to save the Union. His was a delicate dance between upholding old constitutional guarantees of state prerogatives and directly challenging slave-power aspirations. From the point of view of Southern interests, sectionalists arguably jumped the gun in assessing Lincoln. Had they stuck by the Union, instead of seceding, the uneasy coalition probably would have tottered on for a good while, probably to their advantage, for Lincoln, in 1860, was wedded only to the containment of slavery, not its abolition. The Republicans, however, had spent little energy canvassing the South and even moderates below the Mason-Dixon Line believed the party’s trump card was the growing Northern population, which guaranteed a majority that could perpetually roll over and flatten Southern concerns. Moreover, the issues had long since crossed the bounds of rationality. A tide of emotionalism had engulfed the South, fostered by a handful of zealots who were skillful at raising the public temperature. Lincoln tried repeatedly to present himself as a conservative man, wedded to Revolutionary truths and obligated to the limitations of the Constitution, but he was unable to persuade Southerners of either his leadership capability or his goodwill. The words he used simply touched every raw Southern nerve.33

To this mix was added what was perhaps the least palatable ingredient for the South: a tang of moral superiority. The antislavery views expounded by key Republicans did not merely reflect pragmatic issues of law and economics, but humanitarian concerns that branded slave owners as callous, exploitative, or downright wicked. Left to themselves, only a handful of Southerners unconditionally defended their system; most were only too aware of its limitations, both practically and ethically. Yet few were able to imagine a post-emancipation society in which white and black citizens interacted freely. Burdened with what they considered impossible choices, many agreed with Northern moderates who hoped the system would die of its own accord, at some vague future date. Nevertheless, they did not want to be hectored by the Yankees, who they believed had their own moral failures, and whose rhetoric was putting them on the defensive. The momentum to overturn slavery, or at least revisit its legitimacy, pushed Southerners to develop an elaborate set of religious, economic, and racial justifications for human bondage, which they used not only to argue their position, but to convince themselves of its virtue. Lincoln was no radical; nonetheless, he had punctured this façade by expressing a view of the system that dismissed the middle ground. The words that propelled him to national recognition were absolutes, posing the great questions of the day in terms that allowed Southerners no option but to embrace slavery’s eradication or admit wrongdoing.34

The president-elect had said the unsayable: that slavery was not just a national dilemma, to be solved nationally, but that it was evil, and that the South was responsible for its wickedness. “The Republican party think it wrong,” Lincoln stated during his 1858 senate-race debates with Stephen A. Douglas; “we think it a moral, a social and a political wrong . . . that extends itself to the existence of the whole nation.” He repeated the uncompromising image of right and wrong many times during the debates, and publicly thereafter. Lincoln ridiculed Douglas for claiming there was no moral issue at stake, scoffing that his opponent saw “this matter of keeping one-sixth of the population of the whole nation in a state of oppression and tyranny unequalled in the world . . . an exceedingly little thing—only equal to the question of the cranberry laws of Indiana.”35 Privately, Lincoln admitted he saw no way that the issue would be resolved peaceably; still, he proclaimed himself proud of his words. “It gave me a hearing on the great and durable question of the age, which I could have had in no other way,” he told his friend Anson Henry. “I believe I have made some marks which will tell for the cause of civil liberty long after I am gone.”36

He had once been careful to avoid blaming Southerners for their “peculiar institution,” claiming that in a similar position Northern men would have felt and acted much the same. Once in full electioneering mode, however, candidate Lincoln began to chastise the region for close-mindedness, for exacerbating sectional differences, and for irresponsibly holding the nation hostage to threats of disunion. Claiming—incorrectly, as it happened—that the Declaration of Independence had been the work of men who wanted to dismantle slavery, Lincoln placed the North on the brighter side of history and the South outside the reach of reason. He capped it all with the pronouncement that “right makes might,” a dubious assertion, that was seen below the Mason-Dixon Line as a thinly veiled threat. His words were at once courageous and rash: while Lincoln recognized slavery as a horrible blight in America’s idealistic garden of liberty, he also taunted Southern extremists by making a direct hit to their pride. Perhaps Lincoln believed challenges to Southern principles would only be taken as just so much campaign rhetoric, yet he knew his speeches were being carried telegraphically across the country, and that they touched the South at its most vulnerable points. In a region where questions of honor were grounds for murder, the provocation could not be underestimated.37

One of the reasons Duff Green had traveled to Springfield was to offer the president-elect a chance to soften the hard-nosed verbiage, prove he was sensitive to Southern concerns, and underscore his intention to govern the country from a national, not sectional perspective. Green saw that mistrust of Lincoln stemmed from his own pronouncements, which had left the South with little room to maneuver. “We propose to measure Mr. Lincoln by his own standard,” ran a typical comment in the New Orleans Daily Crescent, which also reprinted quotations from many of his antislavery speeches. The Crescent dismissed attempts by Northern newspapers to portray the president-elect as a “moderate, kindly-tempered, conservative man . . . [who] will make one of the best Presidents the South or the country ever had,” concluding, “Will you walk into my parlor said the spider to the fly?” Green, knowing the danger, did not ask Lincoln to retract his words, but he did want him to play down some of the harsher messages, particularly his praise of John Brown, his moralistic Cooper Institute speech, and the 1858 address that declared “this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free.” Lincoln’s worshipful secretaries, John Nicolay and John Hay, later accused the old editor of trying to force their boss to accept personal responsibility for the growing rebellion, but Green told his family that the goal was quite the opposite: “to relieve him of that responsibility by satisfying the South that they had no reason to fear that he would make or countenance in others any attempt to emancipate their slaves.” Green was also trying to reassure secessionists that Lincoln represented only a small faction even within his own party, and that the opposition majority in Congress could defend their interests more effectively if they stayed and voted their way out of the dilemma. He viewed the moment as one of “folly and delirium,” he told Lincoln, but cautioned that no one should take lightly the power of the demagogues, or the determination of the Southern people to fight for their rights.38

Lincoln was disinclined to walk back his words, and in any case he was not convinced of the urgency of the moment. He thought many Southerners were simply reacting to a disappointing electoral loss or threatening secession to gain leverage. Reasonable men, he believed, would in time see him as benign, or even friendly to their concerns. He tenaciously held to the misguided assumption that, outside South Carolina, there were far more loyal citizens than secessionists. “There is much reason to believe that the Union men are the majority in many, if not in every other one, of the so-called seceded States,” he would write. The president-elect appeared oblivious to the increasing danger of the situation, as hard-line disunionists seized the moment to strengthen their position before he actually made compromises that would soothe Southern anxieties. Lincoln was right in thinking that sophisticated men knew he had no intention of meddling with slavery in the Gulf states, but he underestimated how perfectly his electioneering had played into radical hands. His reluctance to offer reassurances that countered the radicals’ inflated rhetoric simply handed them the advantage. Radical Southerners also wanted to move quickly to curtail Lincoln’s power to dispense the kind of favors that might calm criticism. He was beginning to organize his cabinet, as well as look at key federal positions—post offices, custom houses, and land agencies. Secessionists wanted to leave the Union before a large number of Lincoln’s followers were appointed to influential positions in Southern communities. Postmasters might propagandize; customs officials might hold local interests hostage to patronage; and strong personalities might even attract a Republican following. At the same time, the Fire-Eaters wanted to leave the Union before Lincoln could appoint moderate Southerners, a move that might appease those still on the fence about secession. Yet, even as anxious disunionists scrambled to maximize every moment, Lincoln, a lifelong temporizer, persisted in believing time was on his side, that the heated moment would cool, and that prudence would conquer passion. Duff Green left Springfield without the soothing presidential letter he sought, and the Fire-Eaters were left with an uncontested field. “O why does not Mr. Lincoln speak?” implored a Southerner who was desperate to stitch up the fragmented sections. “We are in fact drifting upon the rocks.”39

Lincoln thought any pronouncement, however soothing, would be “futile” since the South “‘has eyes but does not see, and ears but does not hear.’” Once he did speak out, however, he found Southerners were paying quite close attention. Lincoln broke his verbal fast in February 1861 as he made his way from Springfield to Washington, D.C., for the inauguration, which was to take place on March 4. It was a lengthy railway tour, covering more than nineteen hundred miles and lasting nearly two weeks. The new First Family was escorted by a clamorous company of political allies, military officers, and hangers-on. The train halted in dozens of towns and crossroads, where remarks were made to cheering crowds. The route was a northerly one, and the enthusiasm contrasted sharply with sobering events farther south. The threat of secession had now become a reality, as seven states withdrew from the Union, forming the Confederate States of America, just days before Lincoln embarked on the trip. In Washington, a peace conference had been called to resolve the situation, but members of the new Confederacy had declined to attend, and the careworn leaders, bereft of fresh ideas, were dubbed an “Old Gentleman’s Club.” The explosive political situation and fatigue of the journey put increasing pressure on the president-elect at an already tense moment.40

Republican leaders had hoped the trip would lay down important political markers about the upcoming Lincoln government while rallying public support. But the president-elect’s performance during these days was not one that inspired confidence. His speeches were often impromptu, rather than carefully worded, and sometimes deteriorated into flippancy or inappropriate language. He seemed uncertain of the right note to strike, now dismissing the emergency as an “artificial” crisis gotten up by politicians; then speaking of the situation in the gravest terms, hinting at violence, and vowing (with a deliberate stamp on the podium) “to put the foot down firmly” if need be. Whether the talk was tough or conciliatory, he kept on the defensive. Claiming there was little cause for worry, and no justification for the South’s precipitous actions, he denied responsibility for the controversial policies that had triggered such an outsized response. If blood was to be shed, Lincoln maintained, “it shall be through no fault of mine.”41

Those who came out to hear him liked the speeches. It could be argued that they were tailor-made to each situation, with more casual language for his comfortable western neighbors and harder lines aimed at prominent men of the East. But Lincoln seems not to have considered that the media age was already upon the nation, and what played popularly to dirt farmers in Peoria did not always sound good in press reports elsewhere. Serious Northern supporters such as Charles Francis Adams, a Massachusetts congressman and the son of the sixth president, who were looking for calm, cogent leadership, were dismayed by the drift of the president-elect’s pronouncements. “His beginning is inauspicious,” Adams remarked. “It indicates the absence of the heroic qualities which he most needs.” Nervous Southerners, particularly those against secession, were even more distressed, for they were desperately hoping a strong hand would take hold of the national reins and guide them back home. “I am afraid Lincoln is a fool . . . if I may judge by a speech he made yesterday on his journey about ‘Nobody is hurt’ ‘nobody is suffering’ ‘nothing is wrong,’” worried Dr. Charles Carter, a pro-Union cousin of Robert E. Lee:

all this is sheer nonsense, because everybody about here is “hurt,” and “suffering,” and everything is “wrong” in the eyes of everyone except these robber republicans; who have ruined the country and now pretend that all is right, when 6 states are forming an independent government, and that they see nothing the matter; and at the same time cry out “no compromise,” “Chicago Platform[,]” The “Union shall be preserved!”42

In addition, the unprecedented tour, with its look of a traveling circus, provided a spectacle that secessionist leaders, in no mood to be charitable, found easy to mock. “He no sooner compelled to break that silence, and to exhibit himself in public, than the delusion [of a man of ability] vanishes,” wrote an editor in New Orleans, asserting that in silliness, duplicity, and ignorance “the speeches of Lincoln, on his way to the capital, have no equals in the history of any people, civilized or semi-civilized.” Genteel Southerners, contrasting Lincoln’s entourage with the more stately procession of Jefferson Davis, who made a similar whistle-stop trip to his inauguration, concluded that Lincoln was a vulgar upstart. “We are told not to speak evil of Dignities, but it is hard to realize he is a Dignity,” scoffed one skeptical North Carolinian. “How glorious was the President elect on his tour, asking at Railway Stations for impudent girls who had written him about his whiskers & rewarding their impudence with a kiss! Faugh!” Lincoln had spoken at last; but his words were too late and too confused to calm passions or persuade critics; and his style only undercut his ability to instill confidence.43

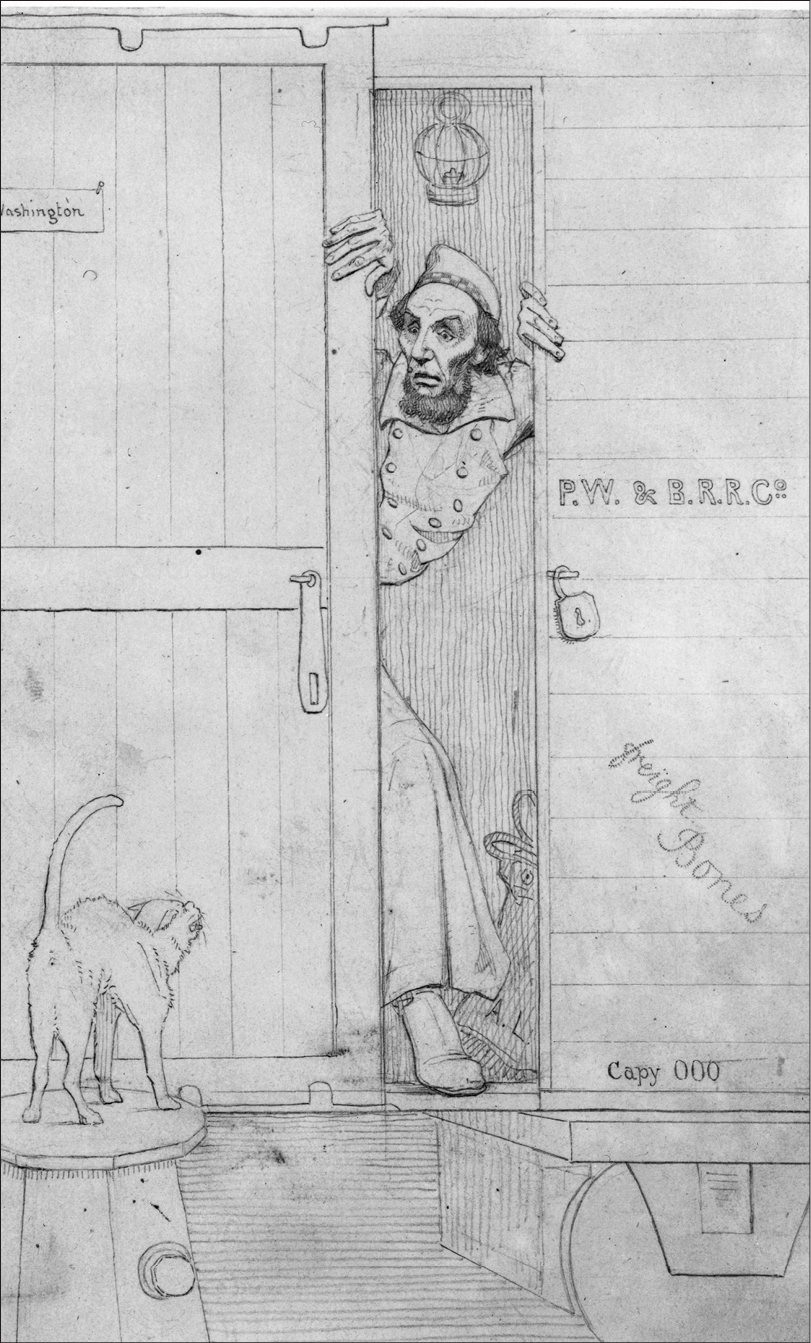

Passage Through Baltimore, pencil, by Adalbert John Volck, 1861. Gift of Maxim Karolik for the M. and M. Karolik Collection of American Watercolors and Drawings, 1800–75

MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON

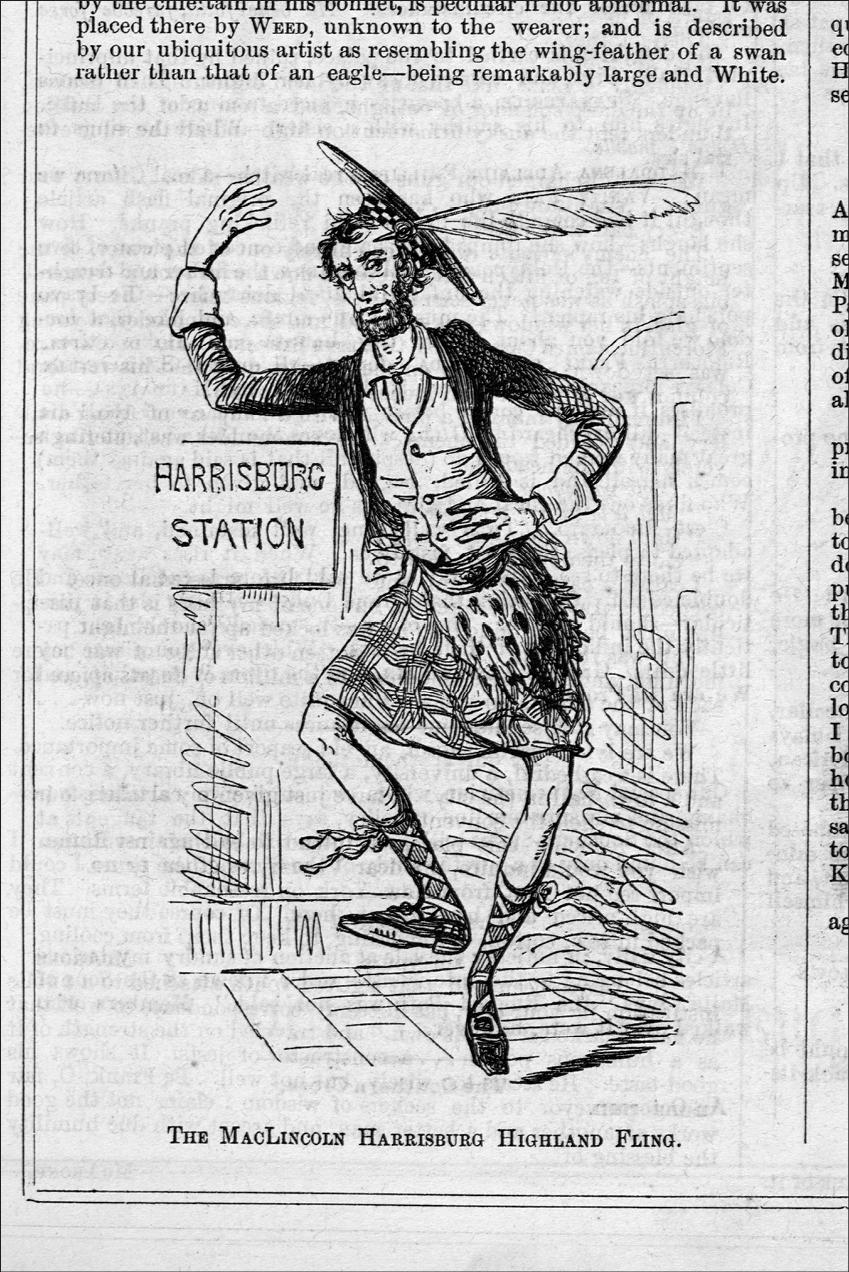

Lincoln’s meandering expedition was capped by an unfortunate incident on arrival. Security en route had been an issue from the start, and the presence of military officers and secret service men showed that threats against the incoming administration were not taken lightly. While in Pennsylvania, Lincoln’s party was advised that an assassination plot had been uncovered by detective Allan Pinkerton. An ambush was allegedly planned for Baltimore, where there was a good deal of “secesh” sympathy, and where the entourage would have to change trains before continuing to Washington. The report was a serious one, and those responsible for Lincoln’s security, including General Winfield Scott, took it seriously. The president-elect was reluctant to alter his plans, and only after coaxing agreed to arrive incognito, by a different train. There is every indication that it was a prudent move, aimed at deflecting either an escalation of tensions or an outright crime. The subterfuge might have been handled more elegantly, however. Lincoln’s eccentric figure was difficult to disguise and he arrived dressed like a muffled-up scarecrow, reportedly wearing a soft “Kosuth” hat—which was made more ludicrous by the imaginative New York Times describing it as a Scotch-plaid cap and Vanity Fair showing the president-elect dancing the Highland fling. North and South tittered over reports of the disguise and seriously questioned the courage of a man who hid behind a cloak while traveling through the pro-slavery state of Maryland. (Mortified by the ridicule, Lincoln erred on the side of imprudence thereafter, with tragic results.) Among those who took advantage of the incident was humorist George Washington Harris, who wrote three stories featuring a backwoods character named Sut Lovingood, who claimed to have traveled in the procession as a bodyguard. Published in a New Orleans newspaper in 1861, and widely reprinted, Lovingood’s description embellished Lincoln’s costume, padding it with liquor bottles, and painted Abe’s face red until “when I wer dun with him he looked like he’d been on a big drunk fur three weeks.” Such reports, even tongue in cheek, fed the growing Southern caricature of Lincoln as an absurd bumbler, who not only was inept and cowardly, but had a fondness for mean whiskey. Worse, it appeared to be proof that the man was exactly what they most feared: an impostor who had sneaked into the presidency through the back door.44

“The MacLincoln Harrisburg Highland Fling,” wood engraving, Vanity Fair, March 9, 1861

“I went to Springfield,” Duff Green told Lincoln, “to urge you to exert your influence to prevent the war.” But could he, in fact, have halted the impending catastrophe? Historians have debated that critical issue with spirit, without coming to consensus. Some have seen Lincoln’s actions during the secession winter as deliberate and canny; a ploy to remain on the defensive, forcing the South to initiate any hostile act. Others have seen him as reactive, stumbling into war without an overall strategy. His papers show him to be highly conflicted, claiming to sympathize with slaveholding regions and anxious to avoid bloodshed, but shunning compromise, which he thought would only leave the issues hanging. Lincoln was probably right that by the time he arrived in Washington nothing he could do or say would change the most intransigent Southern minds—in their rage they had become as deaf as the sea. Yet his inflexible silence was frightening, since it seemed to shut out the possibility of dialogue. Over time, there were signs that Lincoln was moving toward some concessions: he put two men from slave states in his cabinet, for example, and developed a paper that called for the repeal of laws interfering with the Fugitive Slave Act. However, he privately reiterated his rigid “right and wrong” interpretation of slavery to influential Southerners and never stepped back from opposition to the territorial expansion of slavery—and that was precisely what pricked Southerners the most. A conciliatory gesture, showing at least a willingness to forestall disaster, might profitably have been made. Its absence further hardened attitudes and placed him as the chief protagonist in a standoff. Others in his circle, such as secretary of state–designate William Seward, showed more determination to work with the South—particularly the border states—to resolve issues peaceably, but Lincoln undercut their efforts. By denying the crisis and eschewing compromise, rather than reassuring the public that he intended to be smarter than the problem, Lincoln placed himself in the worst possible position for conflict resolution.45

Lincoln’s most important opportunity to reassure Southerners came at his inauguration on March 4, 1861. He had worked hard on the address, which he hoped would show both firmness and goodwill, softening the message at the encouragement of Seward and others who read the draft. The new president spoke of his constitutional duty to keep government functions, such as postal service and the collection of tariffs, running smoothly, and of his obligation to protect United States property—though he sidestepped the issue of “reclaiming” federal assets that had already been seized by the rebels. He also promised to keep “obnoxious strangers” from administrative positions in the South and expressed “no objection” to a constitutional amendment that would prohibit interference with slavery where it existed. But Lincoln also refused to admit that his “dissatisfied countrymen” had any legitimate grievances. Instead, he called secession “the essence of anarchy,” asserted that the Union of states was “perpetual,” and unequivocally placed responsibility for the rift on Southern shoulders.46

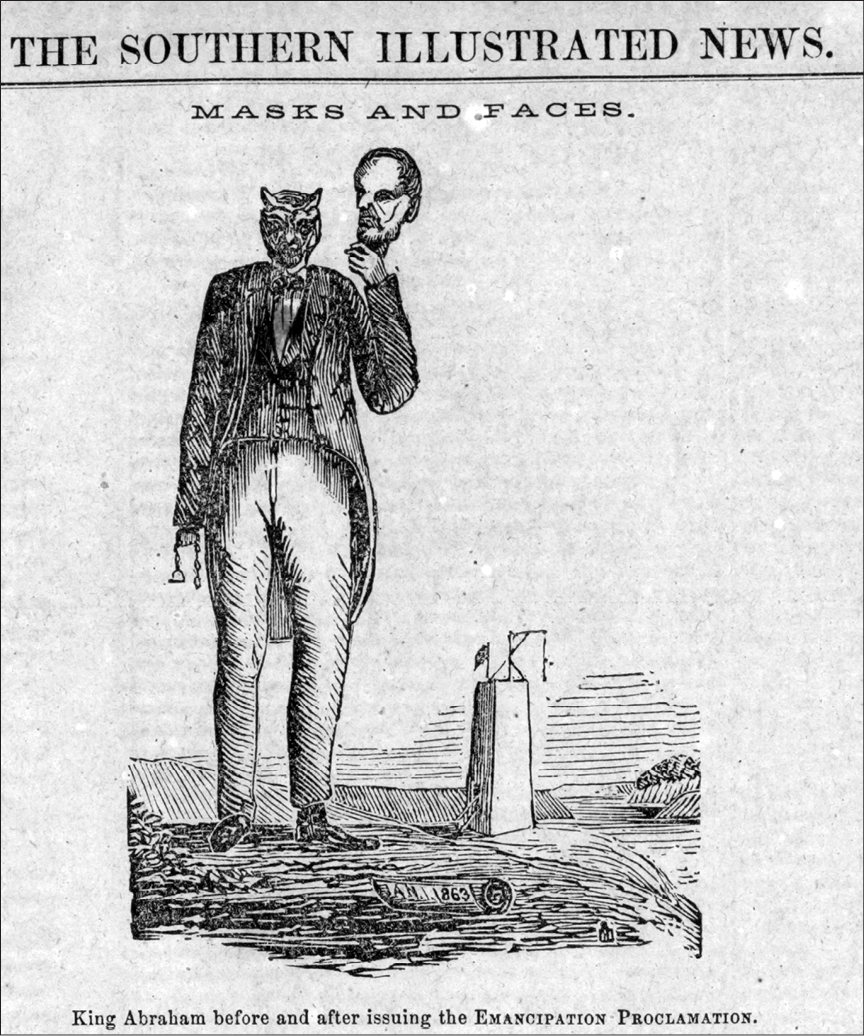

The address concluded on a lofty note, but the ceremony left many people with a sense of malaise. Security remained a concern, and the tight controls Scott placed throughout the city seemed the antithesis of a democratic celebration. “For the first time in the history of the United States it has been found necessary to conduct the President-elect to the Capitol surrounded by bayonets and with loaded cannon,” wrote the daughter of a Union general, who thought the large military presence “detracted much” from the spirit of the day. She did not find Lincoln’s words entirely reassuring. “On that sea of faces turned toward him I could read every variety of expression from exultation to despair”; and though the band hushed the crowd by playing “Dixie,” she continued, “I knew positively that there was no hope for the South.” In regions where many still favored a peaceful solution, newspapers put the best possible spin on the address. “It is not unfriendly to the South,” maintained the loyalist North Carolina Standard. “It deprecates war, and bloodshed, and it pleads for the Union.” In New York, the civic leader George Templeton Strong observed that “Southronizers” thought Lincoln’s message was pacific and likely to avert confrontation. “Maybe so,” wrote a skeptical Strong, “but I think there is a clank of metal in it.” The clank was loud and clear to ardent separatists. In Charleston the Mercury announced that “‘King Lincoln’ O! low-born, despicable tyrant” had made a declaration of war. Sectional conflict “awaits only the signal gun,” agreed the Richmond Enquirer. In Montgomery, Alabama, capital of the infant Confederacy and its new congress, Georgia representative T. R. R. Cobb snatched a copy of the inaugural address from the telegraph but candidly admitted that “it will not affect one man here, it matters not what it contains.”47

Lincoln had hoped to set a determined tone, softened by conciliation, but stress fractures between the two halves of this policy became apparent in the weeks following his swearing in. He particularly wanted to avoid alarming border states like Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee, which had not yet joined the secession movement. In those areas, a burning question was whether Lincoln would try to force states back into the Union, and even those with the strongest loyalties balked at the idea of a “coerced” federation. “If the bond of the Union can only be maintained by the sword & bayonet,” wrote an agonized Robert E. Lee, “its existence will lose all interest with me.” Southerners were already suspicious of Republican motives, and Lincoln’s inaugural pledge to protect government property sounded ominous. The question of whether to resupply—or in some cases reoccupy—forts that had been seized by zealous rebels became a pressing one just days into his presidency. At Charleston, where Fort Sumter’s defenders were running out of food, and South Carolinians were blocking the harbor, the situation had become desperate. Lincoln tried to cut some creative deals—considering, among other things, the abandonment of the fort in exchange for a pledge that Virginia would remain in the Union.48 But like Jefferson Davis and South Carolina governor Francis Pickens, he was a new man on the job; and although intensely nervous about the state of affairs, he was anxious not to appear weak. Under Seward’s influence he approved the convoluted plan mentioned earlier that would have sent subsistence supplies, but no arms, to Sumter, and military reinforcements to another threatened post at Fort Pickens, Florida. It was a flawed operation, featuring the secretary of state planning an operation without the knowledge of either the war or navy secretary, and junior army men commanding ship movements, all of which was complicated by faulty communications and poor weather. The predictable result was that rebel forces opened fire on Fort Sumter. Lincoln’s response was to call out seventy-five thousand militia, including troops from the border states, to protect government interests. With their fears that force would be used now realized, Virginians voted for secession rather than supply men to support what they considered “coercion,” and three other states quickly followed. Lincoln, conscious of his inaugural pledges, and determined not to cede the moment to the rebels, countered by blockading Confederate ports. When a group of loyal Baltimoreans questioned his judgment, he forthrightly upheld his actions. “You would have me break my oath and surrender the Government without a blow. . . . I have no desire to invade the South; but I must have troops to defend this Capital.”49

It had been a badly bungled job, though Lincoln would later gloss it over, presenting the loss of Fort Sumter as a clever ploy to make the Confederates fire the first shot. But his stated intent had been to avoid that shot, and to the South his actions put him squarely in the role of provocateur. Those hoping against hope for a peaceful resolution felt there was now no turning back. It was not just that Lincoln had called out troops to fight against fellow Americans, it was his manner of doing it that so incensed Southerners. Lincoln had refused to engage with Virginia’s representatives in Washington, dismissing them with instructions to read his inaugural speech if they wanted to know his intentions, and they had learned of his call for troops from the newspaper. Shocked and embarrassed, men like William Cabell Rives, who had worked hard to keep the Old Dominion from seceding, reluctantly admitted that “the times, & the nature of the contest, render it impossible for me to maintain a position of neutrality.” His family, which had once pronounced the hotheads in Charleston “as capricious as monkeys,” now watched in disbelief as Rives took a seat in the Confederate Congress. “I see nothing in Civil War to rejoice over let who may be victor,” another prominent Virginia Unionist declared. “Yet I consider Lincoln’s course utterly infamous, as well as wholly unwarranted. . . . His silence & stillness has been like a tiger’s preparatory to his leap.” Secretary of State Seward had also fostered bad will when he hinted unofficially about a brokered peace and withdrawal from Fort Sumter, causing many Southerners to feel they had been willfully misled. “Your President and Cabinet knew [Fort Sumter’s] force and condition,” a young Memphis rebel wrote hotly to his loyalist brother, “and after weeks of lying assurances of peace and evacuation of the Fort to get time to prepare to replenish it, the President issued his war proclamation, which he knew was . . . the signal for action.” Caroline Plunkett, an ardent North Carolina Unionist who had once written that “[i]f I had a sheet of the largest size before me I could fill it with the one subject, my country, my country, my country,” became physically ill when she read of Lincoln’s proclamation and took to her bed in sorrow. She rose a converted woman. “I secede in my heart from the present administration, now that it has adopted coercive measures,” Plunkett declared. She had resisted all family entreaties to drop her Union loyalty, she noted, “but Lincoln & his administration have now done it effectually & if I were a man I would lend all my aid to the Southern confederacy against them.”50

III

Disaffection of the kind expressed by Caroline Plunkett was the last thing Lincoln had wanted to produce. It seemed a constant mystery to him that his policies—and indeed his person—alienated so many. The “good people of the South who will put themselves in the same temper and mood as you do,” he had told Samuel Haycraft, a Kentucky friend, “will find no cause to complain of me.” What he failed to realize was how few Southerners were in the same “temper and mood” as the pro-Republican Haycraft. In 1860, as in 1865, the thing Duff Green wanted to impress on Lincoln was that he was misreading the South and badly underestimating its commitment to the slave economy and to independence. As the secession movement gained force, Lincoln, still clinging to the idea that it would all end in “smoke,” tried to convince Southerners that he sympathized with their concerns. In reality, he knew very little about the region, and was particularly naïve about the aspirations of cotton state demagogues like Barnwell Rhett of South Carolina, or Alabama’s William Yancey.51

Born in Kentucky, of parents with Virginia lineage, Lincoln has sometimes been portrayed as a Southerner, or as having a special sensitivity to the tastes and inclinations of the region. He married into a prominent bluegrass family, avidly read the Louisville Journal, and revered Henry Clay, one of Kentucky’s most accomplished politicians. He spent most of his life in parts of Indiana and Illinois that had a pronounced Southern accent, carried by migrants who crossed the Ohio River, bringing their habits and opinions with them. As a rising attorney, Lincoln had close friends and law partners who came from Kentucky stock, some of them retaining deep-seated social and racial views that reflected the hierarchical, pre-industrial prejudices of the Southern system. Laws that sanctioned quasi-bondage or the use of slave labor, or that excluded blacks, were well known in Illinois. (Some referred to the region as a kind of “breakwater” between the extremes of North and South, but abolitionist critics dismissed lower Illinois as a de facto slaveholding area.) Lincoln noted that he differed with his friends on many of these issues, though “not quite as much . . . as you may think.” He had witnessed slavery firsthand, on visits to Kentucky and Missouri, and on two long flatboat journeys to New Orleans. While seeing slavery as ethically wrong and economically disadvantageous, he did not believe in racial equality and confessed he had no idea how to form a post-emancipation society. “When the southern people tell us they are no more responsible for the origin of slavery, than we . . . and that it is very difficult to get rid of it, in any satisfactory way, I can understand and appreciate the saying,” Lincoln remarked in his famous Peoria speech of 1854. “I surely will not blame them for not doing what I should not know how to do myself.”52 Lincoln did do something about it; but just how to absorb blacks into the larger culture puzzled him for the rest of his life. Despite the fact that he professed affinity with Southern people and Southern manners, and on rare occasions defined himself by their terms, Lincoln also pointed to his Pennsylvania and New England roots when it was politically expedient. Most often he was considered a westerner—a “sturdy Sire of the Prairies”—as indeed was Henry Clay. Only those who mistrusted him, or thought him too tolerant of Dixie men and Dixie institutions, labeled Lincoln a Southerner.53

Lincoln may well have identified with his border region, but the South did not identify with him. Southerners saw him as a prototype of the fanatic Yankee: dangerous because he was tough and unsentimental, vulgar in manner and dress—“the kind who are always at corner stores, sitting on boxes, whittling sticks,” concluded the Confederate gadfly and diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut. They did not share his vision of progress based on free labor, or the cries for universal suffrage and other means of leveling the society. Where Lincoln saw opportunity in programs such as homesteading, they saw little more than a chance for men to carve out lives of drudgery. This was not their ambition; it flew in the face of a strongly gentrified worldview. Their dream of upward mobility embraced ownership of land and slaves, luxury and leisure, and deference from those below, not a hardscrabble life on the frontier. That much of Southern reality bore no resemblance to this ideal did not matter: it was the aspiration that counted, the chance that yeomen could reach toward the aristocracy, and the certainty that someone was below—an African American—to keep them above the bottom rung. Eliminating that rung, by flooding the society with free black workers, only made the status of lower-class whites highly precarious. William Brownlow, a Tennessee Unionist, captured the power of antebellum fantasy when he asked a man in rebel uniform what “rights” he was fighting for. The reply was “the right to carry his negroes into the Territories,” remarked Brownlow. “At the same time, the man never owned a negro in his life, and never was related, by consanguinity or affinity, to any one who did own a negro!” Although Southern yeomen were concerned about their wages and working conditions, and were more suspicious of disunion than firebrands above and below, they did not equate improving their lot with fundamentally altering the society. One of the problems Southerners had with Lincoln’s program was that in a highly stratified world it seemed to lump everyone together, with policies that appeared disadvantageous to all but the slaves. As Mississippian J. Quitman Moore vehemently remarked, the Republican platform was “Radical, leveling, and revolutionary—intolerant, proscriptive, and arbitrary—violent, remorseless, and sanguinary.” The result was a society that moved “constantly downward.”54

Moreover, since the 1840s, middle-rank Southerners had believed there were advantages in capital controlling labor. The bustling economic expansion of the region, in railways and industry, supported this conviction. As the president of the Mississippi Central Railroad explained in 1855, “in ease of management, in economy of maintenance, in certainty of execution of work—in amount of labor performed—in absence of disturbance of riotous outbreaks, the slave is preferable to free labor.” By 1861 more than fourteen thousand slaves were working on the railroad, many of them skilled blacksmiths, quarrymen, carpenters, and foremen. They held similar jobs in factories such as Richmond’s Tredegar Iron Works. Only four Northern states exceeded their Southern counterparts in numbers of new railroad miles laid in the 1850s, and the remarkable growth of this industry was part of the justification for creating an independent nation. Lincoln never understood that the South had fundamentally changed its economic landscape, though Duff Green and others tried to enlighten him. It was no longer a pre-industrial agricultural sector, dominated by comparatively few plantation owners who controlled an assorted peasantry of gang laborers and subsistence-level poor whites, along with the political decision-making process. The Old Northwest, Lincoln’s territory, was the South’s only rival for burgeoning industry—the eastern states were already outpaced—and Southerners saw less to admire in Republican plans for national growth than did their Northern counterparts. Instead they worried that those plans would level off their progress and stifle their prospects.55

Added to this were genuine questions of political philosophy over the right of secession. Southerners certainly wanted to protect slavery, and they wanted to retain the stratified, class-driven society that rewarded a few and provided dreams to others. But they also wanted the liberty to choose their own brand of democracy, not have it dictated by the North. They did not believe the Yankees’ “might” derived from “right,” but from the larger population that gave them a lopsided advantage in representative government. Part of the drive to expand into the territories, to build railroads and extend their customs and laws, was to shore up their base of support—to augment the numbers, if you will. Without this, Southerners saw no way to enjoy a fair share of the government’s power. The consequence they feared was continual humiliation at the hands of a sectional group that wanted to bully them into a republic that no longer represented Southern interests. A West Point man, posted to Texas at the time of its secession, advised his father that the debate was not just a public show of bravado, or a ploy to gain leverage—it represented a sincere concern about the tyranny of a majority. “I had expected to hear bluster and fanaticism, but was disappointed,” wrote Lieutenant Edward Hartz. “[T]hey spoke with a conviction of injury which must be redressed.” Southerners believed that fighting oppression was part of their birthright, the same impulse that had motivated separatists when the British crown restricted self-government in the colonies. Moreover, volunteer withdrawal from the Union had never been clearly barred by American statutes: the Constitution was silent on the issue. Northern as well as Southern states started threatening secession only a few years after the Revolution, and the legitimacy or illegitimacy of separation lay largely in the eye of the beholder. James Petigru, a distinguished South Carolina jurist noted for staking his personal integrity on supporting the Union in 1860, nonetheless maintained that the federal government had no power to extend its authority over the people of a state, even in cases of disunion. Men like Lincoln believed this self-contradictory aspect of American democracy could be resolved by public debate, regular exercise of the ballot, and a high degree of local autonomy on the fundamental issues of society. What worried the South was that the game was now rigged so that they could never win. Many Southerners had practical problems with secession—the expense, tensions, and spiraling fragmentation it could create. But nearly all believed they had a right to select their own kind of government. “Surely,” argued a moderate, “it is contrary to the theory of our Government to subjugate a people who are unanimously opposed.”56