Marketing Libraries with Google+

Amy West, University of Minnesota

Google+ is an attempt to leverage Google’s massive user base into a coordinated identity service by using social features to knit together the existing Google product line. For example, Google Events connects the video chat service Hangouts with Google Calendar and Google Photos (formerly Picasa Web). Google+ now supports broadcast hangouts, communities (topical groups), organizes contacts into circles, sharing of Google Drive files, and photos and video from YouTube.

Google product users will find value from the integration of services they already use with the social features. Thus, for library users who already use Google, getting content from a library via Google+ will be a highly integrated experience that happens relatively seamlessly. Other social media content, such as Facebook updates, can also be more easily brought into Google+; for instance, through direct linking to the Google Calendar. Google+ is an asset for libraries using Google for their events calendars, user contacts, file creation and storage, photo storage and editing. Used well, Google+ can be a valuable tool for creating an integrated social presence.

Compared to other social media tools, Google+ is reasonably well designed. It connects Google’s products, has good mobile applications, and already has a high number of potential users based on the use of Google Search. Specific features relevant to library marketing include:

Broadcast hangouts—useful for author readings, instruction, and other activities

Communities—useful for book groups and other topical approaches

Contacts via Google+ Circles—target content via existing contacts

Google Drive files—can be shared, and include forms for assessing the services you provide to users

Events—useful to leverage Google Calendar and push events directly to Google Calendar

Photos—include photos with Google Events to create a single photo pool for an event, which can create a deeper sense of engagement

Google Search—helps ensure that your library comes up prominently in Google searches

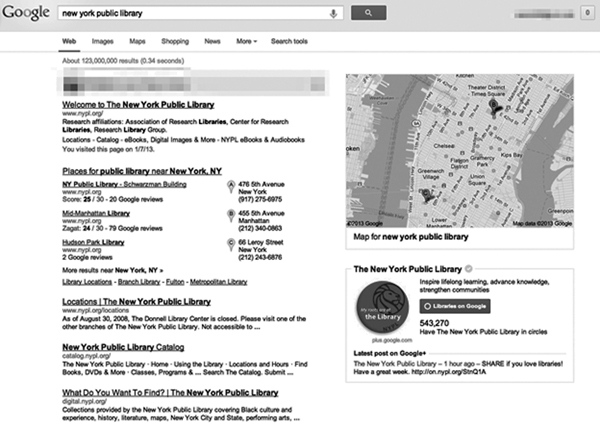

When pursued rigorously, such as the New York Public Library’s Google+ presence shown in figure 6.1, engagement levels seem, from the outside, to be on par with Facebook. However, there is “an unavoidable sense of emptiness in Google+” (Efrati 2012). Currently, there are few examples of libraries with active presences and engaged users in Google+. However, Google+ is not the ghost town some people think it is, as it experienced a 66 percent increase in 2011 through 2012 (Bamburic 2012).

Figure 6.1. Google+ page for New York Public Library

Working within the Google Apps environments can limit various features available to standard Google accounts. As an example, the author confirmed with her institution’s IT staff that sharing files from Google Drive to Google+ is not available in the instance of Google Apps for Education used at the University of Minnesota. For the author, this significantly limits the value of Google+ as tool for communicating with her users. However, as more people and organizations explore Google+ as a social media tool, it is likely that most issues, including this one, will be remedied.

Google+ unfortunately requires that any institutional presence be tied to an individual. Thus, creating a Google+ page for a library is a task that must be tied to an individual. Although ownership of pages can be reassigned as needed, this is one more activity that must be monitored. Depending on the volatility of a library’s staffing, this could progress into a maintenance issue. Including this task into a social media plan and regular procedures is vital.

Despite some flaws, a library that uses Google to provide a significant amount of its technology infrastructure—or whose patrons appear to be heavy users of Google+—may find Google+ to be an excellent choice for a marketing tool. However, if a library wants to reach the largest number of users on the most regular basis, Google+ may not be a good choice at this time, especially if it is the only social media tool. The New York Public Library presence, however, does demonstrate that there is an audience who uses Google+ and that it can be an effective marketing tool.

GOOGLE+ ACCOUNTS

Libraries have several options for establishing accounts. As mentioned above, there has to be a real person using her real or commonly accepted name already using Google+. Per the Google Names Policy, “Pages require a personal profile to act as the administrator of the page, though the administrator may remain anonymous to those interacting with the Google+ page” (Google 2011). Once one or more individuals have been designated to set up accounts, there are two relevant categories: pages and communities. Libraries do not have to have a page to create a community, although it is helpful.

The options for the types of pages include local businesses/places or institutions. Since the business/place option asks for a primary phone number immediately, this choice would work best for single-location libraries or branches within a larger system. Multiple location library systems should start with the institutional option.

Select a name for your library, indicate the users for which the content is appropriate, and agree to the “Google+ Pages Additional Terms of Service” (Google 2013). The current groups for determining appropriateness are everyone, two age groups, and “alcohol related”. As with other social media tools, try to keep library names consistent and recognizable across marketing tools.

While the library staff managing the Google+ page should read and understand the additional terms of service (Google 2013), there are a few elements that warrant special attention:

1. With respect to the age groups, “Google reserves the right to restrict the content on your Google+ Page at its discretion.”

2. With respect to content on pages, “Google reserves the right to block or remove Google+ Pages that violate . . . third party rights . . . ”

3. “Google may, without notice, remove your Google+ Pages if they are dormant for more than nine months.”

Libraries posting content about books may want to think through how they present content on pages because demands to ban books are, unfortunately, not rare. Unlike decisions about removing books from collections, the decision to remove a page is in Google’s hands and not at the library’s discretion.

Google has shown itself to be very interested in supporting third-party claims to intellectual property regardless of the merit of the claims. Recent attempts to remove a remix video consisting of content from Buffy the Vampire Slayer and the Twilight series demonstrate how little interest YouTube, which is owned by Google and tied to Google+, had in properly adjudicating an “entirely meritless copyright claim” (McIntosh 2013). A library might want to post video of author readings, clips from newly acquired resources, and similar items. Google’s approach thus far has been to lock out any user whom it feels is acting against its terms of service, names policy, or other rules; this means that a library could find itself unable to access its own account. This is a case where libraries could help Google understand copyright and fair use.

Once a library has set up a page, it should keep it active, as Google reserves the right to remove a page if it becomes dormant. The library could lose access to photos as well as posts in that case. However, keeping pages up to date is a necessity for any social media tool.

Once a page is live, the library has many options: posting, +1 (similar to liking on Facebook), commenting, resharing others’ posts, adding to circles other users who have added the library page, starting a hangout, and hosting an event. If necessary, the option to block and ignore people is also available. A library could choose to set up a circle, which is a group of contacts, although for promotional purposes this seems to be a feature of little use unless the library chooses to maintain one circle of all the users it discovers. Libraries could also have circles for smaller groups, such as summer reading participants. The primary promotional value of circles is to push notifications to users. This will be discussed more in the section on advertising. Internally, circles could be useful for tracking content shared by other libraries. Thus, if a library system has an individual page for each branch, then placing the other branches into a single circle makes it easy to learn about and to share content across library branch pages.

Once a library has a page, the communities feature will also be of use. For example, a library-run book club would be an obvious candidate. Communities are similar to Google Groups: they are topical, may require permission to join, may be private, and can send notifications on new content. Figure 6.2 provides an example of a community for librarians, LibTecWomen.

The communities feature was just introduced in December of 2012 and thus has yet to become popular. Communities also highlight two related issues for Google. A post at GigaOm in March 2012 noted that perhaps the biggest problem with adoption of Google+ is that, as a late entrant to social networks, “Google needs Google+, but Google users do not” (Ingram 2012). Users likely to use a social network seem to have already settled into existing sites such as Facebook and Twitter, and there is no clear imperative yet for using Google+, other than easily integrated options.

There is some overlap in the Google+ services, which can be confusing. For example, Google Groups, Google’s dedicated forum tool, offers nearly all the same features as Google+ Communities. Events can also be set up as just regular meetings on a public calendar. It’s not obvious, based on a feature comparison, when a library needs to use one tool and when to use a different one. Thus, libraries will want to make some decisions about how to use Google+ most efficiently for the best effect for patrons. It seems that a library can get the most benefit from Google+ if the library works with it as much as possible. For example, it might be best to decide up front that once a Google+ presence is established, all future library events will be handled as events and not simply just as open meetings in Google Calendar. Likewise, your library might create only communities and move its groups to Google+ Communities. However, despite the fact that Google+ has been in operation since 2011, relatively slow adoption and periodic introduction of new features that overlap with existing products has made it difficult to find enough high-quality examples of library Google+ use to develop good practice guidelines that are unique to Google+.

Figure 6.2. Google+ page for LibTech Women

All of that said, if the author worked in a library that was just beginning to establish a social presence, then Google pages and communities both appear to be effective methods for reaching out to library users. Pages bring with them the power of Google. Even Internet users who do not have Google accounts are likely to use Google Search. This means that unlike with Facebook pages—which are mostly gated within Facebook—current and potential users would see much more of a library’s social presence through simple Google searches. Thus, setting up a solid Google+ presence can be a strong marketing tool.

Figure 6.3. Collection image, New York Public Library

Libraries can populate the service with all the kinds of content available from networks such as Facebook and Twitter. For each section below that discusses specific Google+ features, the default setting should be “Public.” Content on this setting is viewable to all Internet users who come across it, and it is sharable to other social networks.

Google+ posts can be either very short, such as Twitter tweets, or long, which might serve as a substitute for a separate blog. The NYPL typically includes an image illustrating each post they make, as demonstrated in figure 6.3. This is an excellent practice, as it keeps the page from being text heavy and gives the library the opportunity to show off visual materials from its collection. Libraries are encouraged to follow the NYPL’s lead—and also to follow best practices for social media as discussed in this chapter, in other chapters of this book, and in other books and articles.

Photos

Photos are a formal section of Google+ and, name notwithstanding, also include videos in addition to photos. Photos are optimized for upload from mobile devices via instant upload, which is activated by default or from individual posts. Picasa, Google’s desktop image editor, is well integrated with Google Photos. Google+ automatically creates an album of images added to posts, an album of profile pictures, and an album of instant uploads. Uploaded videos can come from or be sent to YouTube. A library may also choose to keep its videos uploaded only in Google+. However, as discussed in chapter 4, there is more opportunity for users to find your video content through connecting them to YouTube.

Google’s requirement that content in Google+ be connected to individuals is a weakness with respect to the photos tool. While images uploaded via instant upload go to a private album, the connection of pages to individuals still leaves ample opportunity for accidental cross-posting. If library staff responsible for a library page also use Google+ for themselves, it will be important to make sure that the staff either turn off instant upload on their mobile devices or do not work on the library’s page from their mobile devices. Picasa suffers from a similar problem: library photos edited in Picasa cannot be directly shared to a library page. Instead, they are uploaded to the account of the library staff person currently signed into Picasa. As mentioned before, with enough pressure, Google may consider allowing organizational accounts, just as Facebook made modifications to allow organizations to join.

Hangouts

Hangouts is the name Google+ uses for video conferencing. This is the best feature of Google+. One can hang out with groups of individuals, up to ten at once, or do a “Hangout On Air,” known as a broadcast hangout, which would be ideal for author events where either bringing the author in to speak in person is not feasible or where a library covers a large geographic area and in-person attendance at events might be difficult. “Hangouts On Air” are automatically saved to YouTube, which permits library users to “attend” after the event is over. Hangouts are also great for meetings, although a library should be careful to change the default setting from “Public” to whatever sharing level is appropriate (unless, of course, the meeting is public). Hangouts look like video conferences except that if a user comes across one that is ongoing, there will be an “on air” message.

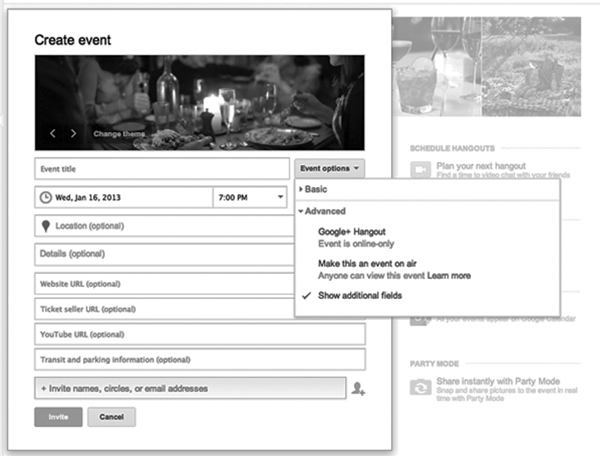

Events

Events are another useful feature of Google+. Used to the fullest extent, an event brings together Google Calendar, Photos, and Hangouts, as shown in figure 6.4. Any individual or circle invited to an event will see the event on the calendar, and people joining an event, but not specifically invited, can add it to their own calendar. The event can be set as a hangout, and, if “Party Mode” is enabled, users of Android devices can upload images and video in real time. “Party Mode” should therefore be used with caution. Attendees of an event can also share their photos to a single album. This latter option is probably better for libraries. It encourages engagement without making it too easy for users to share content that might not be appropriate. The sharing of guest photos can be turned off in the “Actions” menu once an event has been created. Libraries may wish to use this option if they are concerned about unmoderated posting of photos and videos.

Figure 6.4. Google+ event setup

Google Drive Files

Google Drive files—particularly forms for service assessment and gauging user satisfaction with library services—can be shared via Google+ pages by making the file public and pasting the link into a post on a page. However, it is still not possible to share Google+ pages from inside of Google Drive. Using that path, the file will end up being shared on the staff person’s Google+ stream and not on the library’s page. This is another area where Google+ could be more cognizant of the need for changes to occur in order to allow organizations to use Google+ effectively.

MAINTAINING AND ADVERTISING

A benefit of using Google+ is that you can make your Google+ page eligible to show up on the right-hand side of the Google Search page for relevant queries, thus making your Google+ page more discoverable (Google 2013), as shown in figure 6.5.

In addition to this primary method of advertising, one use of Google+ Circles for library pages is to send notifications of new content to users. Unfortunately, the information displays differently depending upon the user’s settings, and some users may turn notifications off completely. However, this is still a feature for libraries to try. Another more common advertising method is to use Google’s AdWords service to direct traffic to the Google+ page.

The most effective way to promote a Google+ page is to regularly post interesting content with eye-catching visuals that addresses user needs. For example, if a library’s users value knowing about new books that the library has acquired, a Google+ page would be an ideal location to highlight new acquisitions along with cover images. Ultimately, Google+ follows the rule for other social media: popularity depends on the user’s perception of the usefulness of the information presented. People are likely to appreciate knowing about the upcoming events, newly acquired materials, and workshops a library offers. If a library’s users already employ Google and find the library’s Google+ page, the users can easily stay aware of the library’s content.

Figure 6.5. Google+ advertisement in Google Search

EVALUATING, ASSESSING, AND USING STATISTICS

At this point in Google+ development, it is not clear how a library would assess Google+ Pages effectively. Google+ does provide the number of +1s and reshares for each post, which offers some evaluative information. Libraries can probably assume that items that are liked and shared are useful and perhaps offer additional information on these topics. Items that are not shared or +1ed may need clarification, more user friendly terminology etc. According to the Google+ Help site, pages for businesses get usage statistics, but there is nothing specifically noted about pages for organizations. As Google+ enhances their services, one can hope that additional analytics become available, especially those that are useful for organizations.

If a library links its Google+ page to its main website, Google Analytics should provide some usage data. As well, if a post is publicly reshared, which occurs when a user sets the share to public when he reshares it, a library can use Google Ripples to see the effects. DiSilvestro (2012) describes Google Ripples and how to use Ripples for marketing. Libraries can explore these options to determine how best to use the data. As with all tools, regular assessment of users and responding to their comments is the best means of evaluation and assessment.

BEST PRACTICES AND CONCLUSIONS

The New York Public Library is as an excellent model of library use of Google+. The NYPL follows standard social media recommendations: they post regularly and in visually arresting ways, they mix content about events with posts on their collections, they include both basic library information (hours, directions) and events/specials, and they keep an informal but still professional tone in their posts. For the most part, the New York Public Library Google+ presence mirrors its Facebook presence and, to a lesser extent, its Twitter presence. Given the moderately high levels of +1s, moderate to low levels of reshares of their posts, but very high numbers of views, NYPL seems to have found a user group that values its Google+ presence. Libraries are advised to follow the NYPL example.

As mentioned, Google+ does have a significant weakness: it requires that all content, even content meant to represent institutions or businesses, be tied to specific people. This introduces opportunities for inadvertent cross-posting of content as well as significantly decreasing individual privacy by forcing the connection between an individual’s personal and professional identities. Although Facebook also connects people and group content, Facebook isn’t necessarily as popular as a search, e-mail, calendar, video, blogging, news-reading, and document storage tool. Google+’s potential lies in its ability to bring all these elements together.

Unfortunately, because Google+ requires that a single person be responsible for the page, this risks a single person’s activities across both personal and professional domains be confused if she is doing so from her personal Google account. If a library and its staff members are all comfortable with this level of risk, Google+ can be very useful. Pages are easy to create and draw on the power of Google Search for promotion. Google+ ties into existing tools, including Google Calendar, Picasa Web, Chat, and Drive, thus making Google+ a potentially powerful tool for socially connected and tightly integrated content. The new Google+ Communities feature has great potential for library use, especially for book groups and similar events. Hangouts provide the opportunity for even small or isolated libraries to connect with authors virtually and to support other community events.

If Google+ continues to add improvements, especially those that solve some of the issues for organizations, Google+ will warrant a reexamination to see whether intervening changes make it a better option for libraries. Certainly, since its debut in 2011, it has improved significantly. One would hope that this record of steady service improvement will continue. If libraries, and other organizations, provide feedback to Google and Google+, it more likely that we will see the necessary improvements to make Google+ a highly useful social media tool.

References

Bamburic, Mihaita. 2012. “Google+ and ‘Ghost Town’ Are a Contradiction.” Betanews. July 27. http://betanews.com/2012/07/27/google-and-ghost-town-are-a-contradiction/.

DiSilvestro, Amanda. 2012. “Google+ Ripples Explained.” Search Engine Journal. September 11. www.searchenginejournal.com/google-ripples-explained/48275/.

Efrati, A. 2012. “The Mounting Minuses at Google+.” Wall Street Journal. February 28. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970204653604577249341403742390.html.

Google. 2012. “Webmaster Tools: Google+ Pages.” December 3. http://support.google.com/webmasters/bin/answer.py?hl=en&answer=1708844

Google. 2011. “Google+ Help: Google+ Profile Names Policy.” Last updated 2013. http://support.google.com/plus/bin/answer.py?hl=en&answer=1228271.

Google. 2013. “Google+ Policies & Principles: Google+ Pages Additional Terms of Service.” Last updated 2013. www.google.com/intl/en/+/policy/pagesterm.html.

Ingram, M. 2012. “Google Plus: The Problem Isn’t Design, It’s a Lack of Demand.” GigaOM. March 15. http://gigaom.com/2012/03/15/google-plus-the-problem-isnt-design-its-a-lack-of-demand/.

McIntosh, J. 2013. “Buffy vs Edward Remix Unfairly Removed by Lionsgate.” RebelliousPixels blog. January 9. www.rebelliouspixels.com/2013/buffy-vs-edward-remix-unfairly-removed-by-lionsgate.