Between 1953 and 1956, the journalist and writer Guido Piovene traveled the length and breadth of Italy in a motor car. RAI (Radio Audizioni Italiane), the state-owned public service broadcaster, had commissioned Piovene to describe and report on the state of a country undergoing rapid change. In spirit and approach, the result was not unlike English Journey (1934) by novelist and dramatist J. B. Priestly. A native of Vicenza, Piovene had been a foreign correspondent in both France and the United States, so he came to his Italian “grand tour” with a native’s knowledge and an outsider’s curiosity. He referred to himself as a “traveler-diarist” and described in radio broadcasts his impressions of the people and places he encountered along the way, in a style that was part investigative journalism, part chronicle, and part essay.

Piovene’s Viaggio in Italia (1957) offers a snapshot of a country on the eve of the great “economic miracle” of the late 1950s and early 1960s, which would transform Italy. Some of Piovene’s encounters tell of an unchanging, impoverished, peasant Italy. Visiting a group of hovels in the small town of San Cataldo (Basilicata), Piovene observes the domestic scene:

A sole pallet serves the whole family; getting undressed is an unknown custom; the chickens’ excrement on the few pieces of furniture seems to be accepted as part of the normal decoration, alongside the peppers and lard, both ornamentation and foodstuff. The peppers, lard, tomato preserve, and, more rarely, pasta; these are eaten sitting in a circle by fishing out of a central dish with tin forks.

On a feast day in the Sila mountains of Calabria, all that the town of Taverna had to offer visitors for food, despite its promising name, were large, flat biscuits and “loaves of bread sprinkled inside with tomato sauce.”

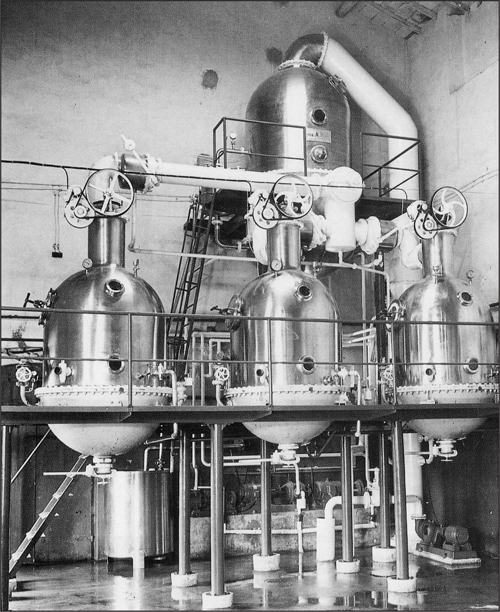

But Piovene also provides examples of development and prosperity, and not just in the north. Land reclamation on either bank of the Sele River, in the province of Salerno, had permitted the expansion of intensive agriculture, mostly fruits and vegetables. The “old food industries” benefited the most, Piovene notes, especially tomato processing, for which Salerno was famous. The Naples area boasted numerous industries—steel in Bagnoli, textiles, and, not least, food—“like the Cirio plant, whose products cover the whole range of diet and is the largest in Europe.” Farther north, in the province of Parma, Piovene praises the Barilla pasta factory, whose owner also was a technician, “expert in market surveys.” Piovene applauds the “American look” of a factory making tomato sauces. The Althea plant, partly owned by Cirio, produced its Sugoro tomato sauce and “instructed tens of thousands of housewives.” “It numbers among our fine industries,” Piovene enthused, “structured not very differently from those that I have seen in America, with the same hygienic concern, the same careful study in the choice of ingredients, the same laboratory-clean appearance” (figure 34)

The three decades following the end of World War II were years of momentous change in Italian society, bringing rapid and extensive industrialization and urbanization. Regional cultures crisscrossed north and south as a result of internal migrations, all affecting Italians’ dietary habits and patterns. Likewise, new methods of food preservation, presentation, packaging, and marketing spread as well. Supermarkets slowly began to compete with small shops, and multinational food corporations with local producers. Although these dietary changes were both qualitative and quantitative, paradoxically, they appeared to change very little.

Figure 34 The four shiny boules give this tomato-processing plant the kind of “laboratory-clean appearance” that so impressed the visiting journalist Guido Piovene. The interior is of Baiocchi, Valentini and Company, Vigatto (Parma), early 1950s. (From Pier Luigi Longarini, Il passato… del pomodoro [Parma: Silvia, 1998])

The closing years of World War II had brought Italy to its knees, dividing the country between the south, which had been liberated by the Allies, and the north, which still was controlled by the Nazis. Everywhere the economy was in tatters, and hunger was part of daily life. If Italians were not starving or even severely malnourished, it was only because of food relief. This began in 1944, but only in the Allied areas, under the auspices of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. The program began in earnest the following year, and by war’s end, it was distributing some 2 million food rations each day to Italian children. In addition, a local and private provisioning network fed millions of hungry Italians. The municipal welfare boards (enti comunali di assistenza) ran soup kitchens (cucine popolari) and distributed money, food parcels, clothing, and medicines. In 1959, fifteen years after the end of the war, 4 million Italians were still receiving some form of assistance from their local boards.

Even after the emergency had passed, Italy remained poor relative to the industrialized West. For example, its per capita gross domestic product was less than 33 percent that of Switzerland. In addition, in Italy the average salary was 60 percent that of West Germany, 40 percent that of France, and 14 percent that of the United States. An Italian parliamentary inquiry of 1952/1953 reported that on average, Italians consumed 50 percent of the sugar eaten by the French and 33 percent of that enjoyed by the British. Their meat consumption was only 25 percent that of the British and 20 percent that of the Danish. Indeed, 38 percent of Italians—some 4.5 million people—never bought meat at all, and another 27 percent bought it just once a week. Although these figures did not take account of any animals raised domestically, like chickens or rabbits, they were shocking nevertheless. In the south, bread and field greens, along with other vegetables, remained the staples.

The Italian food industry was in a fragile state, tied as it was to the poor condition of the country’s agriculture. A report for the Constituent Assembly in 1947 commented on the decline of the tomato-canning industry “in the last few years.” The report linked the drop to the limited availability of fresh tomatoes, as well as the fact that more and more Italians were preserving their own. The immediate postwar years were the most difficult for Italians, as the habits of restraint, austerity, and self-sufficiency proved to be deeply ingrained.

Ninety percent of Italian homes lacked one or more of the modern amenities, such as electricity, running water, or a toilet. Their kitchens usually consisted of a fireplace or a single burner where soup or beans might be cooked. Kitchen ranges, known as cucine economiche, had been available since the 1930s, but they still were beyond the means of most Italians. In the early 1950s, the kitchen of middle-class rural families was still basic, furnished with only a breadboard, a flour chest, a wooden table and chairs, a cupboard, a pasta board, and various pans, glasses, and an earthenware pot for cooking legumes. Their diet was equally simple: dishes requiring only basic preparation.

This was the country that the Christian Democratic Party proudly represented as “frugal and peasant”; the Italian Communist Party derided as “poor, depressed, and colonized by U.S. capital”; and the far-right Italian Social Movement nostalgically saw as “destined for misery after losing its ‘place in the sun.’” In the tense climate of the immediate postwar years, hunger was an important political issue. The Christian Democrats promoted their ability to put food on Italy’s tables, with the generous assistance of the United States. A poster from the hard-fought election campaign of 1948 between the Christian Democrats of Alcide De Gasperi and the Communists of Palmiro Togliatti warned Italians: “Don’t think you can season your pasta with Togliatti’s speeches. So intelligent people will vote for De Gasperi—who has obtained free from America the flour for your spaghetti and the sauce to go with it.”

The shattered and poor country of the immediate postwar years was depicted in the neorealistic films of the time, like Ladri di biciclette (The Bicycle Thief, 1948) and Miracolo a Milano (Miracle in Milan, 1951), both directed by Vittorio De Sica. It also turned to its sense of humor—but only after the worst had passed. In Totò a Parigi (Toto in Paris, directed by Camillo Mastrocinque, 1958) the eponymous protagonist boasts: “I am a genuine starving wretch; mine is an atavistic hunger. I come from a dynasty of starving wretches: my father, my brother, my great-grandfather, my great-great grandfather, my great-great-great grandfather, all the ancestors in my family and collateral branches.” In his many films, the tragicomic Totò, developed and played by the Neapolitan actor Antonio De Curtis, became an icon of the hungry Italian, past and present. It was natural, then, for many people to assume that Italy would remain the poor and proletarian country it always had been.

Instead, beginning in the mid-1950s and in less than two decades, Italy ceased to be a predominantly peasant country and became a major industrial nation. The country’s potential was finally realized. Several factors lay behind this “economic miracle”: vast sums of money were made available by the United States through the Marshall Plan. The end of economic protectionism after Fascism boosted modernization and Italy’s capacity to compete. New sources of energy were developed; the steel industry was transformed; and the infrastructure, like expressways, was upgraded. Besides monetary stability, and perhaps most important, the cost of labor remained low.

As an example of the extent of the country’s manufacturing boom, let us consider refrigerators. In 1951, Italy produced just 18,500, but six years later the figure was 370,000, and by 1967 Italy was producing 32 million, making Italy the third largest producer of refrigerators, after the United States and Japan. Moreover, between 1958 and 1965, the number of families who owned a refrigerator rose from 13 to 55 percent.

Italians were putting their refrigerators to good use. By 1952, Italians were consuming as much food as they had before the outbreak of World War II, and food consumption kept rising in both quantity and quality, in an uninterrupted series of increases and improvements. For the first time, the majority of Italians had the freedom to choose what they wanted to eat.

They exercised this freedom in interesting ways. The consumption of maize, in the form of polenta, plummeted, as it was too closely associated with centuries of poverty and malnutrition. Between 1965 and 1969, it was only one-third of what it had been between 1951 and 1955, down from 48.4 to 16.9 pounds per person a year. Tomato consumption, by contrast, doubled in the same period, rising from 43.1 to 88 pounds per capita. This was substantially more than the overall increase in fruit and vegetable consumption, which itself went up by more than 50 percent, and meat consumption almost tripled. Food imports increased dramatically to meet this demand, rising to 33 percent of the nation’s imports. At the same time, as a proportion of annual income, domestic expenditure on food fell below 50 percent for the first time, to 37 percent between 1965 and 1969.

As many as 3 million Italians, from government employees to factory workers, also regularly ate in company cafeterias, where they got a substantial meal consisting of a pasta or soup course, followed by a second course of cheese, eggs or meat, with vegetables on the side, for next to nothing. According to one union member writing in 1953, at the Marelli factory in Sesto San Giovanni (Milan), workers “eat very well: risotto or pasta with sauce, well seasoned; a varied second course and good wine, too.” Moreover, “there are workers whose home is close by and yet still prefer to eat at the canteen.” High praise indeed, given the symbolic importance of the midday meal at home. More and more Italians thus became accustomed to eating at least one of their meals outside the home.

Italians put all this food to good use, growing an average of 1.6 inches from 1951 to 1972, to 5.7 feet. But they did not grow fat. Indeed, what is most striking is that even though Italians could now afford to, they did not turn to a high-fat, high-protein diet. Of course, they did buy more meat, dairy products, fats, and sugar, and they ate more refined grains (in white bread) at the expense of rye, barley, and maize. The consumption of legumes dropped. Italians also started to buy their foods in different ways. The first supermarket opened in Milan in 1957, to much consternation. Customers (and the curious) were surprised to see so many different products and goods in the same place, but they did not like the idea of self-service, helping themselves without the intervention of the shopkeeper.

Small, family-run shops and town-center markets remained the norm, and Italians maintained a traditional balance in favor of carbohydrates and vegetable protein—in other words, pasta and bread, vegetables and fruit. Although they were buying a lot more food, the content and structure of their meals did not seem to change much, and they prepared their food in familiar ways.

The American foreign correspondent and food writer Waverley Root commented, and it was meant as a compliment, that “Italian cooking has remained basically amateur cooking even when it is executed by professionals.” A dish as simple as “meatballs in tomato sauce” could be elevated to literary status. In a short story by that name (“Le polpette al pomodoro,” 1957), the poet Umberto Saba tells his daughter of the love that he and her mother, Lina, felt for each other, a love that she expressed through the cooking of her “favored dishes.” “If I tell you that her meatballs were love, I would not be telling you anything new,” Saba writes.

In the postwar years, La cucina italiana was resuscitated and returned to advocating basic Italian foods. Joining it was Vera Rossi Lodomez and Franca Matricardi’s Il cucchiaio d’argento, a cookbook that first appeared in 1950 and became a staple of kitchens throughout the country (and a common wedding present). What was new was not so much the content but the notion that women would now be trying to maintain standards on their own, without the help of servants.

Italians remained attached to the cooking of the past, in both structure and content. The paradox was that many people were eating this way for the first time. What we now consider the typical Italian meal structure—a primo piatto of pasta, rice, broth, or soup; a secondo piatto of fish, meat, or cheese, plus one or more contorni, or vegetable side dishes; followed by a dessert of fruit or a sweet—was only now becoming the norm for the majority of the population. In an upwardly mobile society, a family’s ability to adhere to this formula was a sign of status and belonging.

Amid all this abundance, though, renunciation and thrift were still regarded as national virtues. In Elio Vittorini’s neorealist novel Conversazione in Sicilia (Conversation in Sicily), the protagonist, Silvestro, returns to his native Sicily on a quest for “lost human kind.” Food brings back childhood memories for him, flavors lost and found again. These were simple, peasant foods: herring, peppers during the summer, broad beans with cardoons (edible thistle stalks), and “lentils cooked with onion, dried tomatoes, and bacon… and a sprig of rosemary too.” His mother recalls that he always wanted a second helping—indeed, he would have given his firstborn son for a second helping—which, needless to say, he never got.

The novel, written in 1936/1937 and first published in 1941, in the depths of Fascism, met with popular and critical success in the 1950s, when it was paired with drawings made for it by the Sicilian artist Renato Guttuso. By then, Silvestro’s mother would have been able to let him have a second helping of lentils, and more.

In Conversazione in Sicilia, Silvestro’s mother reminds him how she dried tomatoes at home for the family. This was just as Italians, especially in certain areas of the south, had been doing for a hundred years or more. But in other ways, the tomato’s place in cooking was changing and quite dramatically so. First, it was associated with an unparalleled rise in pasta consumption. In 1947, the Neapolitan writer Giuseppe Marotta wrote of spaghetti as “the ideal food for the person who has toiled from morning to night.” Marotta fantasized about becoming a cloistered monk, forever enclosed in the monastery of a spaghetti factory, with its endless blue packets of pasta, bringing with him only cans of tomatoes. From middle class to working class: the dream was at last coming true. Italians could now eat spaghetti al pomodoro to their heart’s content, and they did, to the extent that stereotype and reality began to fuse. What would Marinetti have made of it?

In the same year, 1947, the Neapolitan playwright Eduardo De Filippo wrote a poem in which the fussy narrator reminds his listeners and his long-suffering wife how to make a proper ragù. This was the sauce based on cheaper cuts of meat and tomato paste and cooked at a low heat for hours, first detailed by Pellegrino Artusi in the late nineteenth century and becoming Sunday “gravy” in the United States. If it was not cooked properly—it had to peppiare, or simmer slightly, to use a beautifully onomatopoeic Neapolitan word—it was not ragù, but just meat with tomatoes:

The Meat Sauce

The meat sauce I like

Only Mamma knew how to make.

Since I married you,

We talk about it for the sake of it.

I’m not hard to please;

But I’d rather you didn’t make it anymore.

Yes, all right, as you like.

Do we have to fight about it?

What do you think? This is a meat sauce?

And so I’ll eat it for the sake of it…

But will you let me say something?…

This is meat with tomatoes.

[’O rraù

’O rraù ca me piace a me

m’o ffaceva sulo mammà.

A che m’aggio spusato a te,

ne parlammo pe’ ne parlà.

Io nun songo difficultuso;

ma luvàmmel’ ‘a miezo st’uso.

Sì, va buono: cumme vuò tu.

Mò ce avéssem’ appiccecà?

Tu che dice? Chest’ ‘é rraù?

E io m’ ‘o mmagno pe’ m’ ‘o mangià…

M’ ‘a faja dicere na parola?…

Chesta é carne c’ ‘a pummarola.]

De Filippo transformed the poem into the focus of one of his most successful plays, Sabato, domenica e lunedì (Saturday, Sunday, and Monday, 1959), in which the ritual of the Sunday meal, the preparation for it, and the aftermath famously become the centerpiece of a family fight.

In both Britain and the United States, Italian food already was synonymous with spaghetti and tomato sauce. In 1950s Britain, it was still mysterious and exotic enough that in 1957, BBC television could get away with broadcasting a short documentary on that year’s bumper “spaghetti harvest.” Amid scenes of “spaghetti trees,” it referred to the “spaghetti plantations in the Po valley,” the fortunate disappearance of the nasty “spaghetti weevil,” and the achievements of plant breeders in developing new varieties with equal-length strands, which facilitated harvesting. The date of the broadcast, April 1, ought to have given the game away, but many viewers still were fooled.

Elizabeth David, whose book Italian Food had introduced some British cooks to the subject a few years earlier, wanted to do away with the stereotype. She commented that “only the very credulous would suppose that Italians live entirely upon pasta asciutta and veal escalopes.” Italian restaurateurs and waiters might expect foreigner travelers to want only “spaghetti in tomato sauce, followed by a veal cutlet,” but David knew better. She was right to stress the variety of Italian food, in all its regional and local splendor, and her book rightfully remains a classic. The irony was, however, that it was just this kind of meal to which millions of Italians were then aspiring and replicating.

These aspirations are most memorably depicted in the films of the period. This desire for food can be found in Miseria e nobiltà (Poverty and Nobility, directed by Mario Mattioli, 1954), starring, of course, Totò. In the film, the brothers Felice and Pasquale pawn an overcoat in order to purchase the necessary ingredients for a decent meal: spaghetti with sausage sauce, followed by eggs with fresh mozzarella. Felice (Totò) gives Pasquale detailed and lengthy instructions on the choice of the ingredients, which themselves are part of the anticipation. When the spaghetti is finally served, “full of sauce” according to Felice’s instructions, it is the realization of a dream. After their long wait, the famished diners lose their inhibitions, grabbing at the spaghetti with their hands and shoving it into their mouths, with Felice even filling his pockets.

In another film from the same year, another memorable image appears, perhaps the best-known food scene in all Italian cinema (famous enough to be available as a clip on YouTube). In Un Americano a Roma (An American in Rome, directed by Steno, 1954), Alberto Sordi plays Nando Moriconi, a working-class teenager infatuated with all things American. In one scene, Nando prepares his idea of an American supper—a slice of bread topped with a mixture of jam, mustard, yogurt, and milk—only to spit it out in disgust (no wonder) in favor of a heaping plate of spaghetti with tomato sauce his mother has left for him (figure 35). American culture and optimism might be fine, the film seems to say, but the food has to be Italian.

Sophia Loren, a symbol of vivacious, curvaceous Italian womanhood, once told an interviewer: “Everything you see, I owe to spaghetti.” Her mixture of memoir and recipes, In cucina con amore, published in Italian in 1971 and in English the following year, is testimony to the continuing earthiness typical of Italian postwar cookery. Writing at a hotel in Geneva, Switzerland, while she was expecting her first child, Loren looked back on her poor childhood (as Sofia Scicolone) in Pozzuoli, on the Bay of Naples. She praises her grandmother for teaching her how to make monotonous and cheap foods taste good and varied, and she provides a recipe for spaghetti with tomato sauce, a version of which is “handed down from mother to daughter in every Neapolitan household.”

The change in tomato consumption was first and foremost one of quantity, but just as important was the change in quality. Many Italians could remember a time when the tomato “was hated, as heralding the worst of ills,” in the words of writer-painter-composer Alberto Savinio. Even the Tuscan peasants who cultivated tomatoes refused to eat “the ‘red’ soup because they believed it was harmful to health,” according to Ettore Magelli. Many Italians also could remember when preserving tomatoes meant days of toil in the hot sun or kitchen.

Figure 35 The teenager Nando Moriconi (Alberto Sordi), lover of all things American, feeds his Italian side in Un Americano a Roma (1954).

Now women could choose to buy processed tomatoes if they so desired, along with the newer, ready-made pasta sauces and condiments, to go with their new kitchens. Old-style conserva, formerly sold loose by weight and wrapped in wax paper, was harder to find in shops. Instead, tomato processors launched new products: tomato concentrate in tubes and cubes, and ready-made sauces with mushrooms or meat. Products like these allowed postwar Italian women to become urban, stay-at-home casalinghe (housewives), mixing motherhood, domestic cleaning, and meal preparation at a time of increasing expectations. Convenience foods, like “labor-saving” appliances, represented the sort of change that allowed things to remain much the same for three decades. The figure of the homemaker, as both an ideal and a reality, helped absorb the social upheaval of the period.

The tomato was also being used in new ways, appearing in different guises and finding its way into dishes where it never used to be. Just one example among the many possible: the famous Roman dish bucatini all’amatriciana. Bucatini, a long tubelike pasta, is served with a sauce of onion, bacon (guanciale, from the pig’s cheek or jowl, to be precise), black pepper, and tomatoes, with Pecorino cheese grated on top, and is said to have originated in the town of Amatrice, in northeastern Lazio. At one time, it contained no tomatoes, a “white” sauce that survives today (or that has been rediscovered) as amatriciana bianca.*

Not everyone thought that creeping “tomatoization” was a good thing. It was nothing less than an invasion. Writing shortly before his early death in 1961, Richard Bethell, fourth Lord Westbury, a long-time resident in Rome and all-around bon vivant, bemoaned the tomato’s conquest of Italian cookery in no uncertain terms:

Had the tomato stopped its advance as a sauce for pasta asciutta, I would have little to say against it. But its conquest has been complete, and it is now particularly impossible in central Italy to eat soup, fish, flesh or salad without the ever-present tomato drowning every other taste.

We cannot imagine Lord Westbury being overly enthusiastic about eggs served with tomatoes.

Eggs and Tomatoes (Uova al piatto con pomidoro)

Remove the skins from 1lb. of tomatoes. Into a shallow, two handled egg dish pour a small cupful of olive oil, and in this fry a sliced onion. When it is golden add the chopped tomatoes and stew them for about 15 minutes, seasoning with salt, pepper, garlic if you like, nutmeg, fresh basil or parsley. When the tomatoes are reduced more or less to a pulp break in the eggs and cover the pan. The eggs will take about 6 or 7 minutes to cook and should be left until you see that the whites are set and the yolks still soft. From the moment the eggs are put in, the dish can alternatively be put, covered, in a medium hot oven.

Elizabeth David, Italian Food (1954; repr., Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1963), 143.

Elizabeth David might have been “charmed” by the vivid color that tomatoes provided. But she, too, included the “too frequent appearance of tomato sauce” as one of the “faults of Italian cooking” (along with the excessive use of cheese and powerful herbs like rosemary). Other food writers agreed. Waverley Root noted in 1971 that the tomato “is ubiquitous in Italian cooking today.” Root probably would have preferred the Italian cooking of “yesterday.” In his section on the food of Florence, for instance, tomatoes appear in a wide variety of dishes from tripe to minestrone and from mutton stew to liver. But aside from an obligatory reference to the production of tomato paste in the Parma region, the tomato industry is conspicuous by its absence from Root’s book, as if he were trying to exorcize its presence in his search for “pure” regional food.

Tomatoes do make a brief appearance in Root’s chapter on Sardinia, drying on rooftops, to be used instead of paste, “a manufactured product too expensive for poor Sardinia.” In the chapter Root dedicates to the Campania region, tomatoes appear in the form of melanzane alla parmigiana (eggplant Parmesan), where the “Parma” could perhaps refer as much to the tomato paste as to the Parmesan cheese. In fact, Parma, or any of its food products, may have had little to do with the origins of the dish as prepared in the Italian south. Some purists today prefer to call the dish parmigiana di melanzane, arguing that the parmigiana actually refers to its layers, derived from the Sicilian word for the slat of a shutter (parmiciana).

The misgivings of gastronomes like Bethell, David, and Root aside, and regardless of the raging debates over nomenclature, tomatoes were spreading, for better or worse. All the tomatoes, fresh and processed, that Italians had been buying since the 1950s had to go somewhere. So where were they coming from?

On the surface, the tomato industry in Italy seemed to remain quite traditional. Tomatoes still were harvested predominantly by hand. Canning factories still tended to be located close to the fields, even if the tomatoes were now “sent to their destiny aboard giant trucks,” in the words of the Neapolitan writer Domenico Rea, rather than in “those heavy carts, drawn by horses.”

But in the postwar decades, there were enormous changes here too, in both quantity and quality. Most of the quantitative increase came in the late 1950s and early 1960s, before tailing off slightly during the 1970s. Italian tomato production rose by 75 percent from 1957 to 1967, much more than any other crop. In 1967, the country harvested some 3.9 million tons. Land dedicated to tomato cultivation increased from 271,816 acres in 1957 to 321,237 acres ten years later. Productivity increased, too, with the quantity of tomatoes produced per rising steeply from 1957 to 1967.

These national statistics hide important shifts at the regional level. In the region of Emilia Romagna, tomato cultivation actually declined during this period, and production fell, particularly during the 1970s, by some 20 percent, as did the amount of land devoted to tomato cultivation. The increase in tomato cultivation and production was thus mostly in the south, with production in the regions of Campania and Puglia nearly doubling.

Puglia also was the chief beneficiary of rising rates of productivity. In 1959, an acre in Emilia Romagna produced almost three times as many tomatoes, by weight, as did an acre in Puglia. This disparity narrowed during the 1960s but then rose in the late 1970s, so that by 1984 the three regions had similar productivity rates. More remarkable still, an acre of land in Puglia now produced on average almost three times as much as it had in the 1950s. Nevertheless, Puglia was still sending most of its tomato crop to Campania for processing, much as it had done since the 1880s. The bulk of the south’s canning plants were in Campania, where, in the late 1960s, 164 plants employed some 1,500 people during the canning season, even though most of the factories remained relatively small-scale operations.

Italians consumed large amounts of tomatoes fresh, or freshly cooked, but most of the tomato crop was processed in some way, primarily into peeled whole tomatoes or tomato concentrate. The change instead was who was buying them. Before World War II, increased production would have been reflected in increased exports abroad. Now, as we have seen, Italians were consuming tomatoes in greater quantities than ever before. Exports of processed tomatoes did rise between 1957 and 1967, but “only” by 25 percent. But tomato production rose by 75 percent during the same period, feeding the Italian boom.

The main importers of Italian processed tomatoes remained Britain, the United States, and West Germany. But there was a perceptible shift. Britain and the United States were importing less: Britain presumably because other Mediterranean countries were now competing to supply canned tomatoes, and the United States because of its expanding domestic production, notably in California, which led the world in tomato cultivation and production. The country that took up the slack thus was West Germany. It was no coincidence that by this time, West Germany was also the European country with the highest number of Italian immigrants. For this reason, the increasing German importation of Italian processed tomatoes was, at least in part, an extension of Italian “domestic” consumption.

Tomato productivity increased because of the introduction of new methods of cultivation, including the greater use of fertilizers and pesticides. But, above all, the increase was due to the adoption of new varieties of tomato.

This qualitative shift was a surprise, for it overturns our ideas about “traditional” foods. As early as 1954, Ettore Magelli reported on the virtual disappearance of the ‘San Marzano’ tomato from cultivation in the province of Salerno. Only the occasional plant could still be found growing amid other varieties, most notably the related ‘Lampadina’ (Lightbulb), with its smoother skin, more easily removed for canning. Another guide to tomato cultivation, written by Arturo Giordano and published in 1961, attributed this decline to poor technical skills in the region, primarily the failure to select and separate the best and most appropriate seeds. The result was accidental crossbreeding, or hybridism, and the victim was the ‘San Marzano’ and overall tomato quality.

Whether intentional or accidental, the introduction of different varieties was actually nothing new, as the development, adoption, and processing of new varieties had been part of tomato agriculture and industry since at least the 1880s. Perhaps it was the Fascist period, when there was little change, that was the exception.

In any case, the ‘San Marzano’ remained a popular variety in Italy, despite what the manuals had to say about it. In 1965, it still represented a bit more than one-third (35%) of the country’s tomato production, but by this time it had already been overtaken by a similar, but newer, variety, the ‘Roma’. Its name may have been Italian, but it was developed at the Plant Industry Station in Beltsville, Maryland, in the mid-1950s. With the canning industry in mind, plant breeders there crossed the ‘San Marzano’, ‘Pan American’, and ‘Red Top’ varieties to produce a plant that was more productive, more resistant to disease, and had larger fruits than the ‘San Marzano’.

Moreover, the ‘Roma’ is determinate, rather than indeterminate like the ‘San Marzano’. This means that the plant stops growing when the fruit sets on the top bud, and the fruits then ripens around the same time, making harvesting easier and reducing labor costs. The ‘Roma’ also does not require pruning and needs very little staking, for it is a “bush” tomato. Indeterminate varieties like the ‘San Marzano’, by contrast, grow like vines unless regularly pruned, and they flower, set, and ripen fruit throughout the growing season. It is easy to see why Italian growers, particularly in the south, began to favor the ‘Roma’ over the ‘San Marzano’. By 1969, the ‘Roma’ accounted for half the Italian tomato harvest; the ‘San Marzano’, only one-fifth.

Curiously, the ‘Roma’ became, and remains, one of the best-known varieties in North America and Australia. Its name, shape, and taste helped it become a symbol of “Italianness” in the New World. So successful was it that in the United States. it is sometimes assumed to be a traditional Italian tomato. It is traded as an “heirloom” variety by seed collectors and lovingly grown and bottled by the descendants of Italians in a culinary reinforcement of ethnicity.

In Italy in 1969, for the first time, new pear-shaped, early-maturing varieties found a place—albeit small, only 5 percent—in tomato production. Varieties like the ‘Heinz 1706’, ‘Ventura’, and ‘Chico’ were attractive to growers because they mature over a shorter period. The ‘Chico’, for instance, is closely related to the ‘Roma’ but is slightly larger and lower in acidity. It was developed for commercial purposes by the Petoseed Company in Chico, California. These varieties represented 25 percent of the Italian tomato harvest in 1973 and 30 percent in 1977, on the way to supplanting both the ‘Roma’, down to 30 percent in 1973 and 20 percent in 1977, and the ‘San Marzano’, 10 percent in 1973 and only 5 percent in 1977.

Another novelty tomato in 1973 was a “square” variety, like the ‘Petomech’ and the ‘Cal-j’, resistant to bulk handling and cracking. Two years after their introduction in Italy, square varieties constituted 10 percent of tomato production, rising to 30 percent by 1977.

Could we expect to find some stability in the large, furrowed, round varieties favored in Emilia Romagna? After all, in 1969 they still made up 25 percent of the tomato crop. But there was change here, too. In the early 1950s, in an increasingly competitive industry, Parma-based producers started to look for less acidic, sweeter varieties. To find a tomato that was less tart, they turned to the American cultivars that were then being developed for the “fresh,” or salad, market. The preferred variety was the ‘Geneva 11’, developed in New York State by Cornell University’s plant breeders. Other varieties developed by Heinz’s and Campbell’s plant breeders were grown as well. Even so, round tomatoes accounted for just 15 percent of tomato production in 1977.

If the history of the “Italian” tomato began with its crossing from the New World to the Old in the sixteenth century and then its return to the Americas in the late nineteenth century in immigrants’ baggage, it now crossed the Atlantic yet again, in the form of cultivars developed by American researchers and agribusinesses.

Other factors—and a good deal of chance—were responsible for taking the tomato into parts of Italy where its place in the diet earlier had been limited or nonexistent. One factor was the bathtub.

In 2000, a family doctor in Turin told the historian Laura Fiorini that in the late 1960s, southern Italian “immigrants” in the city would fill their bathtubs with soil and grow tomatoes in them. It is hard to say whether the implication that tomatoes were more important to these people than hygiene is a simple racist slur, an urban legend, or the reflection of a different reality. (From a practical point of view, light levels would be a bit low in the average apartment bathroom for successful tomato cultivation, but at least watering and drainage would not be a problem.)

The doctor’s memory echoes one of the most significant and traumatic social occurrences of the postwar decades in Italy: internal migration. The people to whom the doctor was referring were recent arrivals from the south, living in cheaply built, high-density, subsidized housing and employed at the nearby Fiat car factory. But years before the memory was shared with the historian, this story already was legendary, an infamous indication of the ongoing divide between north and south. The southern singer-songwriter Mimmo Cavallo, a native of Lizzano (Puglia), even made growing tomatoes in the bathtub a badge of southern Italian identity in his song “Siamo meridionali” (We’re Southerners, 1980).

The prosperity in Italy referred to earlier in this chapter had a pronounced regional dimension. The main beneficiaries of the economic miracle were the northeast—the industrial triangle formed by Milan, Genoa, and Turin—and some parts of the center, the areas where the capital, resources, and expertise were concentrated. The result was a growing imbalance between north and south. During the 1960s, northern Italians continued to spend more on food than southerners did. But because northerners earned more, the sum spent on food represented a smaller portion of their annual incomes. Northerners still consumed more meat, dairy products, fruit, sugar, and fats than did southerners. For their part, southerners consumed more carbohydrates, fish, and dried legumes.

Poor Italians coped as they often had done: they migrated, bringing their dietary habits (and aspirations) and their gardening skills with them. Millions went overseas, for instance, to Canada and Australia. Just as the previous wave of immigrants had been attracted to food manufacture and marketing, 13 percent of Toronto’s food retailers were Italian by 1961, and Italians owned 250 food stores and markets in Montreal by the late 1960s. In Australia, Italians and their descendants still grow a significant proportion of the tomatoes. Landownership there was initially made possible by the “share-farming” arrangement, in which the landholder provided the land, irrigation, and housing, and the grower kept two-thirds of the produce.

Other Italians took jobs in other parts of Europe. By 1965, 2 million Italians, three-quarters of whom were from the south, were working in West Germany, Switzerland, France, and Belgium. The Italian government negotiated bilateral agreements with other European countries, linking surplus labor to trade and import agreements. For instance, in 1955, Italy signed a precedent-setting agreement with West Germany that created the guest-worker (Gastarbeiter) migrations of the 1960s. We have seen that tomato imports to Germany increased, partly as a result of this immigration. In Belgium, Italians worked in the coal mines, often in terrible conditions. By the 1970s, however, the derogatory label sales macaronis (dirty macaronis), as Italians there were sometimes called, had been dropped. Both the immigrants and their cuisine came to be accepted, even valued, in the host country. Testimony to this is the appearance of a recipe for Italian pasta sugo in the 1972 edition of the much-loved Flemish-Belgian cookbook Ons kookboek. It is just one example of what has been called the “Italianization” of Flemish cuisine.

The main difference in the postwar migratory wave compared with previous ones was that most of the movement took place within Italy. Out of a population of 50 million, as many as 45 million Italians changed their town of residence between 1955 and 1981. Fifteen million were long-distance migrants, including the 8 million or 9 million southern Italians who moved north. Most left the rural south for jobs in the cities of northern and central Italy, as rural workers could expect to at least double their incomes in factory jobs. They also were attracted by the regular hours and wages. Although peasants had always had more than enough to do during harvesttime, they had few means of earning money during the winter months.

The populations of both Milan and Rome grew markedly during this period, but it was the city of Turin, given its smaller size, that felt the impact of internal migration most strongly. Between 1951 and 1967, its population increased from 719,300 to 1,124,714. Turin also received a much higher proportion of southern immigrants, mainly from the provinces of Foggia and Bari (in the Puglia region) and Reggio Calabria. This influx, of more than 330,000 southern Italians, made Turin the third largest “southern” city in Italy, after Naples and Palermo.

The Turinese were not ready for the migrants’ poverty and “strange” habits. Each group regarded the other as foreign and threatening. By the 1960s, one-third of Fiat’s employees in Turin were southern born. Workers were tagged by their origins: a Piedmontese was a minestra (after their penchant for soup); a native of the Veneto was a polenta; and a southerner was a maccheroni. Food preferences were an obvious marker, but they also paved the way to the eventual cultural mixing. The company cafeteria was often the place where the assimilation began.

Turin’s infrastructure—its housing, hospitals, and schools—was not ready either. Infant mortality rose sharply owing to the unhygienic and overcrowded conditions in which the early migrants and their families lived. The daily effort to establish oneself took priority over comfort. In 1962, one migrant to Turin described his day as “work, spaghetti, and sleep.” The realization of pasta as a staple is seen not as a sign of abundance but as mere survival. The poor and crowded living conditions became a scandal. Turin’s largest employer, Fiat, argued that housing was not its responsibility, but the city’s. Tower blocks were belatedly built, allowing families to own an apartment of their own—complete with bathtub. These developments, like those at Mirafiori Sud, where almost three-quarters of the residents came from the south, were not much to speak of, but they were usually a great improvement over their previous conditions.

To move to the factories of the north, Italians in the south sold their houses and land and abandoned their parents but brought with them packets of pasta, bottled tomato sauce, and dried figs. When the fictitious southern migrants Antonio Capone and his brother Peppino arrive in the capital of the north, Milan, they are dressed in winter parkas, as if equipped for an expedition to Siberia. Once in the apartment where they are staying, Antonio removes from his suitcase a loaf of bread, a whole cheese, and, with great reverence, two packets of spaghetti. On the wall behind them, a prosciutto, a braid of garlic, and a string of chilies hang from nails. The film is Totò, Peppino e la malafemmina (Toto, Peppino, and the Hussy, directed by Camillo Mastrocinque, 1956), sending up the southern migration that was just beginning.

What the new residents could not bring with them they “imported” from the south. On Sundays, Turin’s market at Porta Palazzo was transformed into a meeting place for southern immigrants, especially when truckloads of olive oil or tomatoes arrived. (Today, this practice has been continued by more recent immigrants to the city, for example, from sub-Saharan Africa.) A southern Italian stallholder at Porta Palazzo remembered that the smaller tomatoes common in the south “at first… didn’t exist here [in Turin]. Then we brought them in, and so the southerners knew where to find them.” Just as Italians in the Americas had done two generations earlier, southerners fanned out from Turin’s wholesale vegetable market each morning, peddling the fruit and vegetables at competitive prices to restaurants, bars, and cafeterias. Other southerners set up their own “importing” businesses, bringing in canned whole tomatoes, apparently “not available in Turinese shops” and apparently not seeing the irony in having to import canned tomatoes to the city of Francesco Cirio’s birth.

Gradually, as conditions improved, dietary habits changed, affecting the host city as much as it did the more recent arrivals. Turin, like much of northern Italy, eventually became just a bit “southern” owing to the increased consumption of pasta, pizza, olive oil, and fruits and vegetables.

The southerners in the north changed too, variously following the patterns of continuity, assimilation, or rejection that we encountered in chapter 5. The realization of the pasta al pomodoro dream came at a cost. Turinese family doctors were struck by how much pasta their southern patients could eat. That the elderly, especially, ate the same foods as they had in the south, but in greater quantities—in addition to more meats and fats—eventually led to high rates of metabolic diseases, hypertension, diabetes, and obesity.

The southerners’ first reactions to Turinese cuisine were decidedly negative. In the words of one southern migrant: “Southerners found themselves eating with Piedmontese, these people who eat broth 365 days a year, and they put a little wine in it, turning it purple, which for someone from Puglia is a bit revolting.” Another complained that Piedmontese “foods are more doctored, whereas in the south the foods are poorer but more genuine.” This was symbolized by agnolotti, the stuffed egg-pasta parcels that are one of Piedmont’s great contributions to Italian cuisine but about which one migrant claimed: “I never eat them, on principle, because I don’t know what’s inside; I’m suspicious.”

Not all southerners were so hostile to Piedmontese food. In September 1972, the Fiat company magazine, Illustrato Fiat, reported the curious case of one of its workers and his family from Gallipoli (Puglia). The wife admitted that “we’ve become used to a different taste in food. Southern Italian salamis, for example, are too heavy. The cheese is too sharp. Back down in Gallipoli, for the whole fifteen days of our holidays, I had to cook different meals for my family from the ones my in-laws ate.” Not a statistically valid sample, of course, but an indication of the possible different reactions to novelty and difference.

More typical perhaps was the gradual, almost imperceptible, change in ingrained habits. The change was not just geographical, but social and economic as well. Foodways developed in the rural south seemed less appropriate in the modernized, industrialized, urbanized north. As one southern woman in Turin recalled years later, in the late 1990s,

I have to say that we kept on making preserves.… We did them less with the advent of the refrigerator, obviously. Still, even now people continue to make preserves, of tomatoes, for example. As long as my mother-in-law and my mother were able to do it, when we went down south for the summer holidays, the whole family would be busy for days making sun-dried tomatoes and bottles of sauce. Now we don’t make them anymore, but often we’re given them as presents or we buy them from friends who make them.

Why bother, when Cirio preserves were a household name? Viewers of Italian television were treated to a fifty-second spot for Cirio pelati during the popular program Carosello. With picturesque views of the Bay of Naples and mandolin music in the background, the voice-over reminded viewers that a can of Cirio tomatoes would bring “the taste of the sun” to their tables. Indeed, the word “sun” was uttered four times during the short commercial.

Advertising prospered from the boom and in turn fed consumption. By the 1970s, the economic miracle had more than doubled Italian incomes, and by the end of the decade, the rift between north and south, at least in regard to food consumption, had all but disappeared. Consumers, apprehensive at first, were inundated with advertisements for Cirio preserves, Buitoni pasta, Knorr soup cubes, and Pavesini biscuits. Most advertising was for food, with “mother” in the starring role (or target), showing the products as part of the modern Italian lifestyle, as important as owning a refrigerator or washing machine.

The television program Carosello reinforced the attraction to brand names. It is no coincidence that the program began in the same year, 1957, that Milan’s first supermarket opened and that it ended some twenty years later, during the rapid expansion of private television channels and massive advertising. Carosello was the advertising window that brought daytime programming to a close and led into the evening programs. For the RAI (now Radio Televisione Italiana), the state broadcaster and still suspicious of advertising, the program offered a compromise. It mixed short films, sketches, and cartoons with commercials, which starred well-known personalities, like the singer Mina praising the virtues of Barilla pasta. By 1960, Carosello was the most frequently watched program in Italy, affecting the tastes, aspirations, and choices of millions of Italians.

With hunger banished, the tomato began to assume its place in the much-touted “Mediterranean diet.” Fresh tomatoes, no longer eaten out of necessity by Italian peasants and the urban poor as a matter of subsistence during the dog days of summer when little else grew, could now be appreciated for bringing “summer” into the lives of urban consumers. Liguria’s mixed salad known as condijon (or condiglione in Italian) could take its “rightful” culinary place alongside France’s “salade niçoise,” which it resembles. In the south, varieties of tomato developed for the canning industry or to be hung during wintertime and eaten because they were cheap, were now gastronomic fare, like the ‘Tramonti’ tomato.

We end on a high note. At the end of the 1970s, Italian tomato cultivation and production began to climb again, following a few years of decline, due in part to the oil crisis and resulting recession. Soon there were more Italian tomatoes than ever before, at any time in this fruit’s history. Land dedicated to tomato cultivation reached a peak of 358,000 acres in 1984 and, combined with higher-yielding varieties, saw tomato production soar to three times what it had been in 1957.

September Salad

The tomato is really mature. If it isn’t harvested, it will fall from the bush.… It is in this month that the celebration of the tomato reaches its apex.

The little Tramonti tomato is squat and bellied, hard as a rock, with a gut full and blind. It is ideal for preparing the classic tomato salad to eat together with moistened maize [corn] bread. You slice the tomatoes, sprinkle on some salt, sliced onion, a sea of oil; and by itself, it can keep a person on his feet full of energy till evening. But many people further flavor this classic salad with green chilies, sliced eggplant, and red peppers, with cubes of cucumber and a shower of basil leaves. This food contains all of summer.

Domenico Rea, “I mesi” (1988), in Domenico Rea: Opere, ed. Francesco Durante (Milan: Mondadori, 2005), 1483–84.

The reason was subsidies. In 1984, food and agricultural subsidies formed 70 percent of the European Common Market’s total budget. Beginning in 1978, as part of Europe’s Common Agricultural Policy, all of Italy’s tomato-growing regions took advantage of the subsidies negotiated by the Italian government. The subsidies were paid to processors, who passed part of them on to growers. The policy also included tariffs on imported goods and export subsidies to encourage exports. The aim was to guarantee a minimum price for a whole range of agricultural goods. Moreover, subsidies were regarded as a social tool to assist economically deprived areas and preserve the rural environment. In the case of tomato production, subsidies were intended to protect European producers from world competition, primarily that of California, at a time when market prices were very low. In Italy, the main beneficiary was Puglia, still one of Italy’s poorest regions. Its production of tomatoes consequently increased by a factor of ten to become the country’s highest producing region.

At the time, this growth in food production was seen as a good thing. Farmers and producers earned more; exports rose dramatically; and European consumers paid lower prices.

The Italian tomato had never had it so good.

* The effects were just as pronounced in Spain. It is hard to imagine gazpacho—that ingenious chilled “soup” made of tomatoes, bread, oil, vinegar, and garlic—without tomatoes. But, in fact, it started out as a simple way of using stale bread, softened in oil.