Is the tomato in Italy a victim of its own success? Pietro Citati seems to think so. In an article a few years ago in Italy’s leading newspaper, La Repubblica, the literary critic, writer, and newspaper columnist waxes nostalgically about the tasty tomatoes of the summers of his youth in Liguria. (Citati was born in 1930.) He remembers that the tomato “constituted the heart of my world.” “Not tomato sauce, or rice and tomatoes, which are already corruptions, but the pure tomato, seasoned with oil and salt.” Citati’s tomato was the “supreme fruit of the Mediterranean: gilded, caressed, loved by the sun, that gave form to its inner meaty pulp, where my teeth bit into it, its delicate skin, its seeds, exquisite aroma, and color, worthy of a Chardin or a Veronese.” Artists like those may come and go, but the tomato, Citati suggests, is in irreversible decline.

Nowadays, tomatoes look the same everywhere in Italy. Whereas “the real tomato has different, complicated shapes, with splits and streaks, and often pronounced baroque features, which so pleased the Neapolitan painters of the seventeenth century,” tomatoes today taste of nothing; they are full of water. We have lost much, much more than we realize, Citati warns: “Previously, the pulp, juice, and color passed into the brain, bathing it, just as the tomato had been penetrated and bathed by the sun.” He hopes that somewhere in the Mediterranean, perhaps in Africa, people still are growing the tomatoes of yesteryear. Or maybe some daring young grower in Liguria, Puglia, or Sicily will come forth and offer them for sale. It would not take much capital, only “excellent seeds, a little water, sun, diligence, care, attention, and a supermarket offer.” “Real tomatoes” would be in great demand. Citati himself would be prepared to spend $13 a pound (€20 a kilogram) for them.

Citati’s article appeared in August 2006 in the midst of the tomato season and at a time when most Italians were taking things easy. It was meant to stir up controversy, and it did. To my knowledge, no one wrote in to object that Neapolitan painters were not yet painting tomatoes in the seventeenth century. But in letters to newspapers and agricultural magazines and in blogs, people commented on every other point Citati raised. Many agreed with him, mentioning their preferred varieties that had been lost to “progress.” Yet there was more to this article than the nostalgia (and the deteriorating taste buds) associated with the aging process. If tomatoes do not taste like they once did, it was because they themselves were different. New hybrids were developed to increase yields, withstand pests and disease, and make harvesting easier, but rarely to taste better. Some blamed the subsidies from the European Union (EU); others, market demands. Growers admitted that they were only following the expectations of the market and the food industry. Other respondents, growers and consumers alike, maintained that was not true. You could still find choice—and “heirloom” varieties, if you were prepared to hunt them out—and pay more. And there’s the rub. If people were truly prepared to pay four or five times more for their fruits and vegetables, there would be no problem. But they were not prepared to do so. So why should the supermarkets or the large distributors be interested?

Carlo Petrini, the founder of the Slow Food movement, went even further. In an interview for La Repubblica, he stressed the environmental effects of what he called the “overproduction of food.” In response to Citati’s offer to spend more on “real tomatoes,” Petrini noted that Italians were spending a smaller proportion of their incomes on food than ever before, half the figure of 1970, and they could spend even less, say 10 percent, by buying tomatoes from China. But saving money had hidden costs: the Chinese tomatoes were “obtained by slave labor,” had “traveled by ship, consuming energy” and polluting, and might result in the disappearance of traditional Italian varieties of tomato. Petrini concluded by calling the overproduction of food the main source of the world’s pollution. “We produce food for 13 billion people,” he pointed out, “and there are 6.3 billion of us, and 800 million go hungry.”

Today’s tomato is as complex as the world in which we live, and it is harder than ever to take sides. Who is right, and who is wrong?

Tomato processing is both a specialized and a lucrative business. Using cutting-edge technology, tomatoes intended for tomato paste are cultivated by direct seeding, sown by precision machines using coated seeds, and harvested entirely by machine. The varieties are almost exclusively modern hybrids, with names like ‘Perfect Peel’, ‘Isola’, and ‘Snob’. (Who was the person at Asgrow who thought up that last one?) Tomatoes intended for canning whole are cultivated slightly differently. Instead of direct seeding, “plug” seedlings are used, and the tomatoes are harvested still predominantly by hand. Only hybrids are grown, such as ‘Hypeel’, ‘Italpeel’, and ‘Calroma’.

Today’s tomato never stands still. Multinational seed companies are hard at work on developing ever newer hybrids, able to withstand drought or give us more of what is “good for us,” such as antioxidants like lycopene, supposed to help prevent cancer and heart disease. Although genetically modified tomatoes seemed a real possibility in the 1990s, they turned out to be a dud.

In Europe, tomato concentrate made with genetically modified tomatoes was first marketed in Britain in 1996. But a backlash in the United States against another transgenic tomato, the ‘FlavrSavr’—which contained a deactivated gene responsible for producing the enzyme that enabled the fruit to soften—took down the tomato concentrate with it. Even though the American public has come to accept genetic modification in commodities like maize and soybeans, tomatoes were seen as a step too far. Italians’ opposition to transgenic tomatoes came from both consumer groups and growers’ associations. One frequently stated objection was that farmers would have to buy their seeds each year from multinationals like Monsanto, since the seeds contained in the fruits they grew either would be sterile or would not grow the same tomatoes. (The same has been true since the 1950s for most of the hybrids grown in Italy and everywhere else.) Today, no genetically modified tomatoes are sold anywhere in the EU, either fresh or processed. But Europe’s strong biotech lobby has not given up. Research continues on genetically modified tomatoes, ready for the day when consumers are “willing” to accept them. In addition, tomatoes in pill form, enabling us to benefit from their cholesterol-reducing lycopene (especially in tomato concentrate) without actually having to eat them, is already in the testing stage.

Tomato processing is one of Italy’s great successes, leading to the export of products proudly bought and sold as “made in Italy” for more than a century. In addition to entrepreneurial know-how, there has been help along the way. The agricultural subsidies introduced by the European Common Market in the 1970s continue, albeit in a slightly different form (although as I write, the entire Common Agricultural Policy is under review). As it stands, under a quota system, Italy’s share of the European Union’s subsidies for tomato cultivation is slightly more than half the European total. Starting in 2001, Italian growers have received a subsidy from the EU for cultivating tomatoes destined for processing. Recently, however, the subsidy has been half the grower’s price, or, to put it another way, once the costs are accounted for (fertilizer and labor), any profit that the growers make for their labors is the subsidy itself.

Subsidies have had the effect of encouraging cultivation for processing. Not all tomatoes end up in tubes, cans, or jars, which explains why so many are sold and consumed fresh locally. In addition to payments to growers, the EU also provides millions of euros in export subsidies, which enables Italian producers to export at low prices. Not surprisingly, California producers—and the state is the world’s largest tomato processor—would like to see an end to these subsidies. Although the United States government pays the country’s maize farmers an astonishing $25 billion a year (representing around 80 percent of their earnings) and more than $1 billion to rice growers (representing the total value of their crop), the growers of fresh produce, including tomatoes, receive no direct support. The countries hardest hit by the EU subsidies, however, are those of West Africa because Italian producers have been able to flood the market there with cheap tomato paste, undercutting, for example, Ghanaian producers.

In addition to the subsidy, the EU enforces a tariff of 14.4 percent on imported tomato products, to make them more expensive, and the World Trade Organization prohibits developing countries from responding in kind if they want its assistance. So Ghana cannot protect its fledgling industry, even though developed countries can. For instance, in order to make its own processed tomatoes competitive with subsidized Italian tomatoes, the Australian government also imposes a tariff on them, although at 5 percent, it is relatively low.

Tomato products thus are very big business in Italy. Although the country exports far more than it can produce from locally grown tomatoes, it makes up the shortfall by importing processed (or partly processed) tomatoes from other countries, such as Turkey and China. Italian growers, and much of the press too, have been extremely hostile to Chinese imports, often using expressions like “yellow peril.” In 2004, Italy imported 165,000 tons of tomato concentrate from China, worth $88 million. Because the tomato concentrate was repackaged in Italy, the label could read “made in Italy,” and because it was imported in unfinished condition, it was exempt from import duties. This “country of origin” legislation passed in 2006 was meant to outlaw this sort of ambiguous labeling, but in 2004, tomatoes rotted in Italian fields because it was not commercially viable to harvest them.

The irony in this is that the Chinese, apart from their increasing consumption of fast foods, seldom eat tomatoes. The origins of “ketchup” may have been Asian, but the condiment never contained tomatoes. The Mandarin word for “tomato” is , transliterated as fanqie (literally, “barbarian eggplant”). Finally, in the 1990s, Italian producers, eager for a cheap source of processed tomatoes, helped construct factories in China and advised on cultivation. The Chinese were happy to oblige and now export processed tomatoes on their own to Europe and Africa, and are now the world’s largest producer of tomato concentrate.

These subsidies and cost cutting were not enough to save Italy’s Cirio Company from bankruptcy in 2003, taking down thousands of investors with it. Until then, Cirio had managed to retain a place in Italian hearts by positioning itself as a traditional company, tracing its roots back to its founder, Francesco Cirio, in the mid-nineteenth century. In reality, though, it had long ago ceased to be a family company, and in any case, processed tomatoes were a later addition to the company’s repertoire. Cirio was declared insolvent after defaulting on more than $1.4 billion in bonds and was dismantled and sold. In 2004, the company’s Italian branch was purchased by a consortium, led by the rival food-processing company Gruppo Conserve Italia, based in Bologna. The Cirio brand was relaunched in 2008 in a television commercial featuring the famous French actor Gérard Dépardieu using Cirio canned tomatoes to prepare a pasta sauce for his expectant guests. Dépardieu beams proudly at the camera, boasting in hybrid Franco-Italo-Neapolitan, “Tengo ‘o core italiano” (I have an Italian heart). The commercial’s message was at once international and local, modern and traditional, with a hint of passion and southern Italian sunshine.

Italy has never produced a film to rival The Attack of the Killer Tomatoes! (1978), directed by the Italian American director John De Bello. In this parody of Hollywood B-movies, a housewife peeling some tomatoes triggers the rebellion of a multitude of large, angry tomatoes intent on conquering the planet. For Italians, the reality of work in tomato fields probably is horrific enough. But worse was the organization and exploitation of Italian labor by local gang bosses, depicted in Michele Placido’s film Pummaro’ (1989). The film tells the story of a Ghanaian medical student, Kwaku, who travels to the Caserta area (Campania) to find his brother, a tomato picker nicknamed Pummaro’, who has disappeared. The harsh conditions of the tomato pickers, many of whom were African immigrants, are vividly depicted. In scenes evocative of depictions of African American slavery, fields of cotton are replaced by fields of tomatoes. Pummaro’ was one of the first Italian films to recognize that Italy—for so long a nation of emigration and, more recently, of internal migration—was now on the receiving end, with immigrants performing the tasks that Italians now shunned.

Since the expansion of the EU in 2004, eastern Europeans have taken the place of Africans. In the summer of 2006, when Citati launched his tirade against flavorless tomatoes, an investigative journalist went undercover to explore the conditions of immigrant tomato pickers in the vast, treeless plain south of Foggia (Puglia), known as the Tavoliere. Fabrizio Gatti had investigated the terrible humanitarian conditions of the Italian refugee camp on the island of Lampedusa, passing himself off as a refugee and experiencing life there firsthand. The following year, once again for the respected Italian newsmagazine L’espresso, Gatti disguised himself as an immigrant tomato picker for an investigation that won him the European Union’s “journalist of the year” award.

Pretending that he was a Romanian was easy. For between $21 and $28 a day, Gatti worked under a ruthless gang boss. Lodging, for which Gatti had to pay $7 a night, was a disgusting makeshift shack without water or electricity. If the workers showed up late for work in the fields, they would be beaten. If they missed a day, even if they were sick, they had to pay a fine of one day’s labor. The farm owners and tomato buyers either ignored such abuses or anonymously tipped off the local police to the presence of illegal immigrants working in the fields, typically on payday, so that the police raid relieved the boss from having to pay them. Even Doctors Without Borders set up a mobile hospital in the area, like those used in war zones in the developing world. Workers also “disappeared.” Gatti finally had to flee on a bicycle when he was told that his gang boss was angry with him.

In its underlying violence and inhumanity, the Tavoliere’s labor system has changed little from the days of the landless day laborers, locally called giornatari, who assembled before dawn each day in the central square in the hope of securing a day’s work. A hundred years ago, the main crop in the Tavoliere was wheat. The overseer, or gang boss, known by the military-sounding title of caporale (corporal), hired the workers on behalf of the estate owner. He rode on horseback and carried a long thick stick, pointing at the giornatari he wished to hire and leading them to the distant fields and sometimes beating them with it if they were slow. The giornatari of the Tavoliere were in an even worse position then Parma’s day laborers (examined in chapter 6) because they had no system of tenant farming to go back to. All they had was year after year of hired toil in different places, for no set wage and no job security. When the giornatari did revolt, as they did in 1920, occupying uncultivated lands, they were violently put down by an alliance of large and small landowners, gang bosses, and local police, leaving dozens dead.

Today, the main crop is tomatoes rather than wheat, but the system of caporali and giornatari persists. The difference is that now the gang bosses are Polish, exploiting other Poles, hired in their own country and bused south across Europe, where they soon descend into a form of labor slavery from which there is no easy escape. In many ways, the modern version is worse, as journalist Alessandro Leogrande suggested. At least in the old system the bosses lived with the giornatari, in the same communities, and relied on their labor, which helped limit their excesses. There are no such checks on the modern bosses—foreigners hiring other foreigners—who themselves are transients. The Italian farm owners collaborate with them, turning a blind eye to abuses—financial, physical, and psychological—because of the pressure on them to keep costs to an absolute minimum. “Because nothing, but nothing, down here can stop the tomato harvest. Not the weather, not the rain, not the hail; so we can forget the law or the denunciations by day laborers,” wrote Leogrande. Nonetheless, recent legal action against the system, beginning with accusations made by three brave Polish workers, has had some effect. Since 2008, mechanical harvesters have started to replace handpicking, a sure sign that new laws and increasing checks on illegal labor practices are starting to have an effect.

Tomato cultivation has been associated with other ills, too. In a country where water is a scarce and often unpredictable resource, agriculture is responsible for more water consumption than any other sector. Paradoxically, agriculture also is the main culprit for its pollution. The massive use of chemical fertilizers and herbicides end up in the water supply, posing a threat to human health. The Sarno, one of the rivers (along with the Sele) that enabled the success of tomato cultivation and production in the province of Salerno in the early twentieth century, is now its victim. Huge amounts of water are taken from the Sarno during the fifty or sixty days of the growing season. Actually, nobody seems to know how much water is used, or even how much is really needed. What does the river get in return? A reddish liquid, colored by the skins and seeds left over from canning. The river, which is only 15 miles long, is today one of Europe’s most polluted.

New hybrid varieties of tomatoes have vastly increased productivity since the 1950s. At the same time, local or traditional varieties (varietà tipiche) are trumpeted or given protected status. In Vittoria (Sicily), local tomatoes like the ‘Ferrisi’ and the ‘Pachino’, grown where the soil is slightly saline, which gives them a mineral taste, are highly prized by restaurants as far away as Turin. Farther north in Albenga (Liguria), another furrowed variety, the ‘Cuor di bue’ (Oxheart), underwent a resurgence beginning in the 1980s, after languishing for decades when rounder, smoother varieties had been the fashion (figure 36). In the Sarno River valley, the ‘San Marzano’ has been given “denomination of protected origin” status. A variety originally developed for the export market has become a proud part of the region’s identity and is once again finding its way into cans—even if it now takes a laboratory to determine whether the seeds are genuine ‘San Marzano’.

These developments were the result of a slight shift in the EU’s policy. In the 1970s, the EU’s laws made it illegal to sell any cultivar not on the national list of each member country. Passed to ensure seed quality and “purity,” the laws had the effect of favoring uniformity and large commercial growers at the expense of traditional varieties and smaller growers, since it was expensive to “list” a tomato type. Recently, some flexibility has been introduced into the system, and traditional cultivars have been promoted.

Figure 36 The revival of traditional tomatoes: a crate of ‘Cuor di bue’. (Photograph by F. Gioberti, courtesy of the Cooperativa Ortofrutticola, Albenga)

In the 1990s, one-sixth of the Italian population made their own tomato conserva. Competing with these are ready-made sauces and other products, which abound as never before and now claim more than one-third of the processed-tomato market. Much of Italians’ food is still locally grown and raised, and what was previously seen as a sign of backwardness is now one of the key planks of the Slow Food movement (another Italian export worldwide). Italians also continue to prefer “naturalness” in their foods, and accordingly, their consumption of frozen foods is one-quarter that of the British and one-third that of the French or Germans. In addition, the Italians have turned the much-vaunted “Mediterranean diet” into an ideology, albeit respecting less in practice its components of a high intake of grains, legumes, vegetables, and fruit and a low intake of animal fats, at least compared with thirty years ago.

Finally is the force of tradition in food habits, which is particularly striking in the millions of Italians outside Italy, including their generations of descendants. They, too, continue to bottle tomatoes in the “traditional” way. The troubled teenage protagonist of Melina Marchetta’s novel Looking for Alibrandi (1992) may dread her family’s “tomato day” and the embarrassment that would result if any of her school friends should see her helping out. But as a Sicilian Australian, she comes around in the end, praising the “tradition that we’ll never let go . . . because like religion, culture is nailed into you so deep you can’t escape it.”

In the postmodern world, “tradition” (or something like it) and the “constant flow” of goods demanded by supermarkets (and their consumers) go hand in hand. Italy is no different from North America or northern Europe. Fresh tomatoes are available year-round, grown under plastic during the winter months, in places like Vittoria (Sicily). A few growers even use the same, almost otherworldly, techniques first developed by the Dutch, in which tomato vines 50 feet long, in computer-controlled environments, are given precise doses of water, fertilizers, and pesticides. The irony is in growing ‘Pachino’ tomatoes, famous for the slightly saline taste the soil imparted, in coconut-fiber mats, their roots never touching the local soil. This is indeed a far cry from the day when local farmers protected their tender plants from the wind with pads of the prickly pear cactus.

Mass distribution has transformed the food chain. Today, a supermarket consumer in Vittoria, shopping for those famous local tomatoes anytime between October and April, may be offered something grown locally, but the tomatoes will have traveled more than 1,000 miles in the process. From the countryside around Vittoria, the tomatoes travel by truck to Catania, then by ship to Naples, and then again by truck to Fondi (Lazio), Italy’s largest wholesale fruit and vegetable market, where the supermarket chain purchases and redistributes them and the tomatoes begin their “return” journey. Vittoria’s growers are lucky to earn 90 cents a pound for these greenhouse tomatoes, but the supermarket charges around $2.60 a pound. Most of the difference goes to pay the costs of the distribution system. Organized crime also takes its cut, in what has proved a lucrative business, with the Mafia insisting on using its own transport and packing companies; threatening producers, buyers, and wholesalers; and even trafficking in the illegal immigrants employed in wholesale fruit and vegetable markets like Milan’s Ortomercato. Seventy years ago, New York’s “Artichoke king” could only dream of market infiltration on such a scale.

Let us conclude this book with the most important issue of all: taste. Do today’s tomatoes taste different from those of the past, as Citati maintains? The short answer is yes. But there is a long answer too, and it is much more interesting. First, although this may seem obvious, taste is subjective and can vary widely from culture to culture. Moreover, tastes change over time. The tomato depicted in Federico Cesi’s Erbario miniato (see figure 5) may look like some modern-day furrowed varieties, but we cannot assume that it tasted like them.

Today’s food scientists can identify specific tastes. As Harold McGee has written, fruits and vegetables are a mixture of sweet, acid, and bitter tastes. The tomato’s low sugar content (3%, which is low for a fruit) combines with a large amount of savory glutamic acid and aromatic sulfur compounds—more common in meat than in fruits—to produce a unique flavor. This balance of sweetness and acidity goes well with a wide range of foods. Because glutamic acid is the active ingredient in the flavor enhancer monosodium glutamate (MSG), it is no surprise that what is botanically a fruit is most often used as a vegetable.

Of course, there are many kinds of tomatoes. The tomatoes we eat are the result of hundreds of years of work by farmers and plant breeders to bring out those qualities considered desirable or health giving and to reduce those considered unpleasant or harmful. This is where we leave the objective view of the scientist for the subjective realm of our own present and past.

As an illustration of the tomato’s subjective present, let us compare two very different European countries: Britain and Italy. Today, the tomato has different “taste zones.” If we looked at a British seed catalog at random—say, Mr Fothergill’s A–Z of Vegetables—we would find that of the thirty-three varieties of tomato seeds offered for sale in 2007, the descriptions of thirteen contain the word “sweet.” Thus we have expressions like “beautifully sweet,” “very sweet,” “wonderfully sweet,” and, just to vary things a bit, “very high sugar content.” The varietals’ names echo this: ‘Nectar’, ‘Sweet Millions’, and so on. If we chose an Italian seed catalog, however, the picture would be very different. Of the thirty-eight tomato varieties listed in the Fratelli Ingegnoli catalogo guida for 2007, the descriptions of only four highlight sweetness. The emphasis instead is on tomatoes with a “firm pulp,” “strong flavor,” and “deep red color.”

This difference between the British and Italian catalogs can be found in the very different ways that tomatoes are consumed in the two countries. Even the word “fresh” has different meanings. A tomato bought “fresh” in Britain is consumed as a salad tomato, but in Italy, a tomato bought “fresh” is just as likely to be used as a cooking ingredient or for further processing. Different tomato varieties are consumed because different flavors and consistencies are required. On the one hand, salad tomatoes have a high water content and thin skins and are sweet. Processing, on the other hand, requires firm, almost “dry” tomatoes that are not overly sweet, since sweetness will be brought out in the processing. The Italian taste for tomatoes thus has been conditioned as much by a preference for vegetables served firm (as opposed to mushy) as by the dominance of the processing industry in determining which varieties of tomato are grown and marketed, especially over the past hundred years or so.

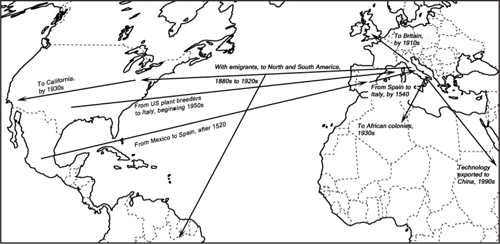

Now let us look at the tomato’s subjective past. Food scientists find it logical that tomatoes are used in a variety of ways, especially as a savory condiment. But for historians, at least for me, there is nothing preordained in the tomato’s history, nothing inevitable about pasta al pomodoro or any of the other many different ways in which tomatoes are prepared and consumed in Italy. Furthermore, there is nothing inevitable about the tomato’s becoming Italy’s dominant “vegetable fruit,” to the point that the average Italian consumes around 198 pounds of fresh tomatoes and almost 66 pounds of processed tomatoes each year. There is nothing inevitable about Italy’s becoming Europe’s premier tomato nation and the world’s second-largest exporter of processed tomatoes, and nothing inevitable about the “Italian” tomato’s becoming an international success story, having crossed the Atlantic Ocean several times and reaching even more distant shores (figure 37). Instead, the tomato’s history in Italy is the result of a series of chance developments.

The tomato’s success in both Italy and elsewhere is due in no small part to its malleability. For two centuries, Italians limited the use of the few tomato varieties they had, and their early confusion with the tomatillo points to the tartness of those tomatoes. Dietary rules and practices restricted the uses of a food with such qualities. But as medical ideas shifted, so did the place of the acidic tomato, which found an ever wider place as a condiment, stimulating the appetite and aiding digestion. By the end of the eighteenth century, growers were beginning to develop new varieties, more delicate and less acidic in taste. This, in turn, encouraged a wider use of tomatoes in sauces and even as a dish on their own. It was not long before tomatoes were being used as a substitute for meat in sauces. In the nineteenth century, they began their career as salad tomatoes, first among the poor, and in the second half of the century, new, smaller varieties were used to season pizza and pasta. These varieties were especially well suited to being canned whole, whereas the larger varieties were turned into paste.

Figure 37 The well-traveled “Italian” tomato. (Map by the author)

This is the second factor in the tomato’s particular evolution in Italy: its close association with preservation and processing. The desire to consume tomatoes as a seasoning throughout the year resulted in their being pickled or sun dried, producing full-flavored condiments. Large tomatoes were best suited to sun drying, as well as to the means of preservation developed next, that of turning them into a paste. At first, this paste was dry and used like a spice. It was dark colored, had a very strong flavor, and was used sparingly. But with the invention of canning, tomato paste could be produced in a less concentrated, more liquid form, which retained the tomatoes’ red color, and producers sought less and less acidic varieties.

At the same time, smaller, egg-shaped varieties were proving ideal for canning whole, with their skins removed. As tomato processing became an industry itself and an important export, new tomato varieties were developed—redder, sweeter, firmer, and more productive. Processing brought out their sweetness, with pelati becoming an acceptable substitute for fresh tomatoes. Indeed, Italians found that processed tomatoes were even better suited to sauces than were fresh tomatoes, and their association with industrially produced pasta was born.

This is where human ingenuity, our final factor in the evolution of the tomato in Italy, comes in, first in the form of seasoning, condiment, and sauce. Necessity played an important part, too, as poor Italians resorted to eating what little produce was available during the hot, dry summer months. Raw tomatoes offered a change from the “green” diet of vegetables that was the peasant’s mainstay. The summer salad, in its various forms—the southern acqua-sale, the Tuscan panzanella, and the Ligurian condiglione—became part of Italian regional cooking, especially as Italians gradually became less dependent on it in order to survive. In its cooked form, the tomato found a place in an abundance of dishes. Of course, the greatest leap forward was the creative association of tomato sauce with what was fast becoming a staple: pasta. More than anything else, more than even the EU’s subsidies, the invention and popularity of pasta al pomodoro as a symbol of Italian cooking were behind the success of the Italian tomato worldwide.

Closer to our time, ingenuity in the form of technology has been important as well. Tomato concentrate appears in a range of processed foods, from canned sauces to frozen pizza, and has experienced a popular resurgence in response to claims about the health benefits of lycopene. Even though it may not yet be genetically modified, today’s tomato is a medical “superfood.” Even the plant’s leaves—whose smell repulsed the first botanists and which have long been regarded as toxic because of their effects on pests—may be good for us, as the tomatine they contain apparently reduces cholesterol absorption. The chefs who have recently started to add a sprinkling of leaves in their tomato sauces toward the end of cooking, to impart a freshly picked tomato smell, may have discovered something new about the tomato.