Italy is Europe’s premier tomato nation. Its total production of fresh and processed tomatoes is more than that of all the continent’s major tomato-growing countries put together. In Italy today, something like 32,000 acres are dedicated to tomato cultivation, producing around 6.6 million tons of tomatoes for the food industry. The market is worth an astonishing $2.2 billion. Tomatoes are consumed both fresh (raw and cooked) and preserved (in cans, jars, and tubes), and their use in sauces with pasta has become a stereotypical element of Italian cookery, even for Italians. In Italy and beyond, the health benefits of tomatoes are praised as a basic element in the “Mediterranean diet.” Lycopene, an antioxidant that tomatoes contain, is known to lower the risk of heart disease, cancer, and premature aging. Never has the tomato enjoyed such favor as it does today.

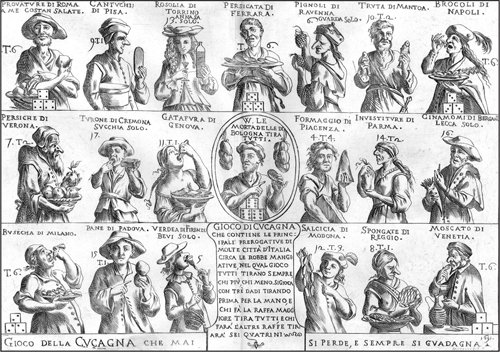

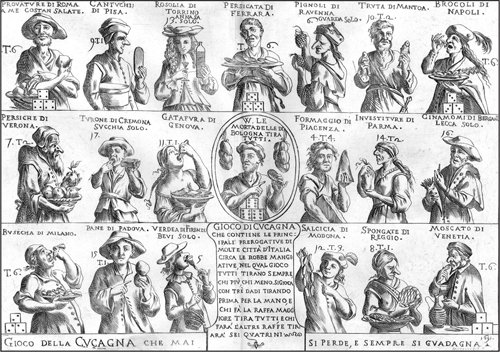

It took a very long time for this to happen, three centuries in fact. The initial reception of tomatoes was hostile, as sixteenth-century physicians were unanimous in regarding this Mexican native as poisonous, the generator of “melancholic humors.” And if the tomato is stereotypical of Italy now, correctly or not, it certainly was not in previous centuries. But there were other stereotypes. In a 1615 letter to the French queen Maria de’ Medici from Mantua, the comic actor and playwright Tristano Martinelli wrote that he was as eager to visit her in Paris as “a Florentine is to eat little fish from the Arno, a Venetian to eat oysters, a Neapolitan broccoli, a Sicilian macaroni, a Genoese gatafura [a cheese-based pie], a Cremonese beans, a Milanese tripe.” Three-quarters of a century later, the same regional stereotypes, plus a few more, were represented in print by Giuseppe Maria Mitelli (figure 1). Not a tomato in sight!

More than three hundred years separate the tomato’s first arrival in Italy in the mid-sixteenth century from its consumption and cultivation on a large scale. Even today, there are areas of Italy where relatively few tomatoes are consumed and cultivated.

The combination of pasta with tomato sauce, pasta al pomodoro, is so widely consumed that it is hard to imagine that it dates back to only the late nineteenth century, by coincidence around the same time that millions of Italians started crossing the ocean to the New World, where the tomato originated. Without this amazing, fortuitous creation, the world would be a much less enjoyable place. Recalling a meal with the dramatist and all-round Fascist celebrity Gabriele D’Annunzio in the 1930s, the poet Umberto Saba recalled the revelation when he was first offered a plate of pasta with tomato sauce. D’Annunzio may have been a disappointment, Saba wrote, but the pasta was not; it was a “crimson marvel” (purpurea meraviglia).

Figure 1 Giuseppe Maria Mitelli’s print depicts early Italian food stereotypes in the form of a board game, Gioco della cuccagna che mai si perde e sempre si guadagna (1691). (© Trustees of the British Museum)

How the tomato came to dominate Italian cookery after such inauspicious beginnings is the theme of this book. We shall look at why tomatoes took so long to be adopted and where in Italy they eventually became popular. We shall consider the international nature of the “Italian” tomato, since it traveled across the Atlantic—several times—and beyond. We will look at the presence of the tomato in elite and peasant culture, in family cookbooks and kitchen account books, in travelers’ reports, and in Italian art, literature, and film. The story will take us from the tomato as a botanical curiosity (in the sixteenth century) to changing attitudes toward vegetables (in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries); from the tomato’s gradual adoption as a condiment (in the eighteenth century) to its widespread cultivation for canning and concentrate and its happy marriage with factory-produced pasta (both in the late nineteenth century); and from its adoption as a national symbol, both by Italian emigrants abroad and during the Fascist period, to its spread throughout the peninsula (in the twentieth century).

But this is more than just a history of the tomato. From the start, the tomato was closely linked to food ideas and habits as well as with other foodstuffs, with pizza and pasta being only the most obvious. Finally, the tomato’s uses were continually subject to change, from production to exchange, distribution, and consumption. For all these reasons, the tomato is an ideal basis for examining the prevailing values, beliefs, conditions, and structures in the society of which it was a part and how they changed over several centuries.

The recipes reproduced in the book are historical in that they originally appeared in printed and manuscript sources throughout the tomato’s Italian history. Although I cannot vouch for them personally, they do not seem dangerous.

This book is part of my ongoing research project on the reception and assimilation of New World plants into Italy, supported by the generous funding of the United Kingdom’s Leverhulme Trust. I was able to begin the project in 2005/2006 by taking a year’s leave from teaching and administration, which was funded by the Wellcome Trust, as part of a strategic award held jointly by the Universities of Leicester and Warwick, and by a semester of university study leave in 2007. As a visiting professor for six months in 2006, I also was fortunate to benefit from the unparalleled facilities at Villa I Tatti, the Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies, in Florence. I would like to thank all these institutions for their generous support to make my research and writing possible. I also must acknowledge the interlibrary loan department at the University of Leicester Main Library for patiently and expertly handling a seemingly never-ending series of bizarre tomato-oriented requests, and to the Biblioteca dei Georgofili in Florence, where I spent many happy hours immersed in old farming manuals.

As always, my greatest pleasure has been the interaction with other scholars and interested individuals, especially since I am something of an interloper in the world of food history. I would particularly like to thank Allen Grieco (Villa I Tatti, Florence) for reminding me to pay close attention to details like shape and color when reading historical references; Sheila Barker (Medici Archive Project, Florence) for introducing me to the project’s magnificent database; Ken Albala (University of the Pacific) for his infectious enthusiasm for all things related to food and its history; Amy Goldman (New York) for her queries and expertise regarding “heirloom” tomatoes; Alessandra Guigoni (University of Cagliari) for sharing her knowledge and publications concerning Sardinia; and Donna Gabaccia (University of Minnesota) for sharing her work in progress on the Columbian exchange.

I also benefited greatly from the suggestions of my colleague Chris Dyer (University of Leicester), as well as Mauro Ambrosoli (University of Udine), Ottavia Niccoli (University of Trento), Alessandro Pastore (University of Verona), Lucia Tongiorgi Tomasi (University of Pisa), Jules Janick (Perdue University), Nerida Newbigin (University of Sydney), Lia Markey (Florence and Chicago), Joan Thirsk (University of Oxford), and Simone Cinotto (University of Turin).

I am grateful to those people who so generously made their images available for this book: Paolo Cason (www.paolocason.it/libia) for contributing his pictures of colonial Libya, Alfonso Messina (www.solfano.it/sgammeglia) for the archive photos of Canicattì, and Gianfranco Barbera at the Cooperativa Ortofrutticola of Albenga, home of the revived ‘Cuor di bue’ tomato. Author Pier Luigi Longarini and publisher Maurizio Silva graciously allowed me to use images from Longarini’s Il passato … del pomodoro (Parma: Silva, 1998), and local historian Catherine Tripalin Murray kindly allowed me to reproduce an old photograph from A Taste of Memories from the Old “Bush”: Italian Recipes and Fond Memories from People Who Lived in Madison’s Greenbush District, 1900–1960 (Madison, Wis.: Italian-American Women’s Mutual Society, 1988).

Finally, I would like to express my thanks to the anonymous readers who read the book on behalf of Columbia University Press, and especially to Jennifer Crewe for her interest in the project and to copy editor Margaret Yamashita for casting an attentive eye over my wordy enthusiasm.

All translations are my own, unless otherwise indicated.