CHAPTER 6

Pain, Not Suffering

My early “success” involved shooting everyone in the room, then asking if they could support my position. Then I learned that there was always someone with heavier artillery, and that allies were the key to success. We need to understand and apply the principles of leveraged support and convince others that “the road less traveled” is less traveled because it’s an inferior road.

Compartmentalizing Pain

Facebook displays more public grief than any other media platform, in my experience. We see photos of injured people, of people in hospital beds with tubes and wires attached, and of deceased relatives, as well as memorials to former pets and so forth. Private grief has given way to a public rending of garments, virtually.

We are all faced with pain. Some of us face it professionally and institutionally—hospice workers, surgeons, police officers, therapists (to name a few). Yet most of these people are able to endure, despite seeing death, assisting those in great pain, and counseling those in grief. They don’t absorb the pain they encounter, nor the suffering; otherwise, who could do their jobs? I’ve always been surprised that a clinician, hearing generally woes and regrets for forty hours a week, can still drive home devoid of road rage and engage in dinner conversation about her daughter’s soccer game or son’s music recital.

In most holy books, there’s an admonition to “turn the other cheek.” We may hear it in a sermon or from a parent in response to a hurt that was inflicted by someone else. And it’s true that a visceral reaction to being struck or hurt is often ill advised. After all, sometimes the hurt is inadvertent.

But nowhere in any tract or proverb that I’ve read or heard are we advised to turn the other cheek and allow ourselves to continue to be hit. We can deal with the pain the first time, but we needn’t submit ourselves to ongoing suffering.

Pain is unavoidable. Suffering is not.

We undergo pain, often unpreventable. But suffering is a decision, a choice, a measured response.

I was always skeptical of wakes. I recall a classmate who had a serious heart condition so severe that he couldn’t participate in games and had purple lips. Finally, halfway through high school, it was determined that an operation was necessary and he was thought to be ready. He died on the operating table.

When a group of us attended the very Italian wake, I was astounded at the public grieving, crying, and lamentations that went on. But I realized later that this was the “appointed suffering” stage, where we all joined in the pain and the mutual support, family and friends. Jews sit shiva for the same purposes. After the prescribed period of suffering, we are to get back to our lives. Some of us, of course, choose to continue to suffer. That is a choice, not a biologic requirement. That sounds harsh, perhaps, but it’s true.

I love dogs and have, therefore, lost dogs to age and illness. It’s horrible; their lives are too short. But my response is to honor their deaths and then acquire more dogs to continue in their spirit, and that’s the advice I’ve given to countless people who have come to me in the same condition. Suffering doesn’t help. The pain must be dealt with, but it’s never the pain that lasts, it’s the self-imposed suffering.

I’ve encountered people who, years later, decry their not choosing a lottery number on a certain day, bemoan the relationship they allowed to attenuate, complain about the poor deal they received from someone else, or regret the job assignment they didn’t pursue or accept. It is a litany of suffering that benumbs the spirit and saps all energy.

We need to compartmentalize pain; otherwise, it seeps into every crevice of our existence. Our missing a promotion at work shouldn’t lessen our enjoyment of our children’s accomplishments at school. A bad argument at home can’t affect our judgment in evaluating a subordinate’s performance on the job.

If we don’t compartmentalize pain, we allow it to surface and to fuel anger in inappropriate settings. You don’t want to scream obscenities at the cop who pulled you over because your spouse said vile things at breakfast, and you don’t want to explode at your boss after you found out that the vet can’t do anything for your pet.

It’s not a matter of other people not understanding your pain (though they often don’t), but it is a matter of their perception of how you deal with suffering (“Would you please step out of the car?”; “I don’t know if he can deal with the pressures of leading the western office”).

This is my advice to you if you want to control pain and reduce suffering to be highly successful:

• Allow yourself to suffer for a given period and to a given degree, but not uncontrollably.

• Replace what was lost with a new pursuit or interest or relationship.

• Tell people you trust about your pain, but do not inflict your suffering. And don’t allow them to do so either.

• Don’t grieve publicly (that is, among strangers and virtual acquaintances). It actually demeans your pain by making it a spectacle.

Life is far too diverse and unpredictable to avoid pain and suffering, but we can compartmentalize the pain and limit the suffering so that we can be resilient and energetic, and escape long-term depression.

Generalizing Victories

I once managed international sales forces. Because I was trained to search for distinctions, I was constantly asking, “What’s distinctive about the best performers compared with the next best?” What I found, among the obvious traits (high self-esteem, enthusiasm, and so forth), was the ability to generalize from a specific positive and isolate specific negatives.

If most of us try to play an instrument unsuccessfully, we generalize that negative: I have no affinity for music. But what’s actually occurred is that you couldn’t learn how to play the piano at age twenty with that particular instructor amidst the other obligations and time pressures of that period. (Originally, I feared speaking in public, and now I’m among the fewer than 1 percent of all speakers in the Speaker Hall of Fame.)

I’ve heard poor salespeople say things like:

Maybe I’m not cut out for sales.

This new product can’t be sold.

The customers are getting tired of the offerings.

You’re not giving me the same support I used to get. (I loved that one!)

They were generalizing from a single negative experience, or even several. But what they were creating was their own “doom loop”: I didn’t sell this, I’m not very good at sales, the next person I visit will realize it, I didn’t make that sale either, I’m not very good at this, the next person…

The best people talked like this:

I can sell anything.

I love to face new objections.

People can’t resist me.

I’m going to set new records.

This isn’t merely about being “positive,” though I’ve discussed the power and importance of that already. It’s about the ability to generalize from a specific success to general success. In this case, you learn to play the piano and say, “I can master any instrument I choose to.”

You create an “achievement loop”: I sold this over tough objections, I can overcome any objection, the next person I see will experience this, that person bought, I’m constantly overcoming objections, the next person will experience this, I sold to that person…

The occasional setback becomes an aberration in an achievement loop, but the occasional victory becomes “luck” in the doom loop.

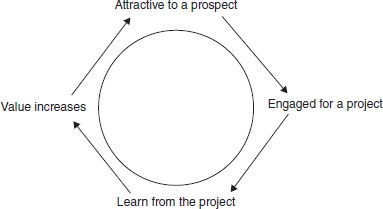

Figure 6.1: A Sales Achievement Loop

When I realized I could successfully speak in front of tough high school assemblies, I realized I could speak anywhere—not just in that high school before those groups, and not just at seventeen, and not just in that city. I realized that what I was doing wasn’t luck because I was able to constantly replicate it.

In figure 6.1 you can see a sample achievement loop for a salesperson. You prove yourself attractive to a prospect, you win the business, you learn from the experience (replicate success), your value as a resource increases, and you become even more attractive to the next prospect. This is all based on refusing to see singular or isolated successes as one-time (or, worse, random) events, but rather as indications of how genuinely good you are.

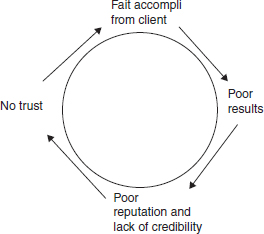

Figure 6.2 shows the doom loop for a sales professional, which no amount of training will solve or improve. This is a coaching challenge, helping people generalize from specific achievements rather than setbacks.

I’m convinced that the prime differentiator between those who are in pain because of presumed failings and engage in endless suffering and those who are free of pain and engaged in continuing victories is the ability to generalize single successes into lifelong beliefs about worth.

Figure 6.2: The Doom Loop

Bill Buckner was an excellent ballplayer for the Boston Red Sox, but his entire athletic history has been reduced to the ball that went through his legs while he was playing first base in the sixth game of the 1986 World Series against the New York Mets. The Red Sox would have won the series, but that error allowed the Mets to win game six, and they went on to win the seventh game and the championship.

Buckner should never have been in the game. He was injured, and there was an excellent defensive replacement available late in the game, but the manager chose to leave Buckner in “to experience the glory of winning the series” and that proved to be a horrible decision. Despite his career with three teams (he had set records as a first baseman) that single error was generalized into his overall evaluation. People still talk about it in Boston. (I’m sure they’re saying similar things in Seattle about the Patriots winning the Super Bowl in 2015, when Seahawks coach Pete Carroll called for a pass that was intercepted on the goal line at the end of the game, though they had the best runner in the game available and just two yards to go for the winning touchdown and second consecutive Super Bowl title.)

We can’t allow ourselves to be defined—especially by ourselves—by a single error or some poor choices. We have to define ourselves by our success and achievement, and that success and achievement can be a single instance that fuels future ones.

One of the counterintuitive points I found is that generalizing victories often relies on the subordination of ego.

Subordinating Ego

I discussed earlier, with only mild hyperbole, my technique for gaining consensus: shoot first, ask politely later. I belonged to a consulting firm in Princeton where this was the rule (picture Mad Men on steroids), and we practiced the quick draw rather than the consummate argument. Argument was for debate teams, and didn’t those go out with Latin?

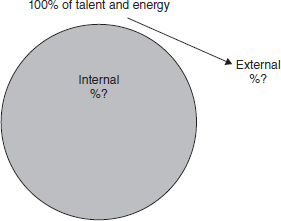

In figure 6.3 you can see a representation of something I realized once I was licking my wounds, counting my scars, and notching my guns. Every organization—and person—has only 100 percent of talent and energy to expend. The old rubrics and apothegms about “giving 110 percent” belong in dated movies about Notre Dame football or admonitions from some motivational guru who’s asked that you build sand castles on the beach at high tide.

That energy and talent is applied either externally or internally. Period.

For the organization:

Internal is office gossip, turf battles, concerns about job security, desires for promotion, an attractive coworker, the poor food in the vending machines, the boring boss.

External is the client or customer, the product, service, and relationship.

Figure 6.3: Where Is the Energy Going?

For the individual:

Internal is self-doubt, self-limiting beliefs, paranoia, low self-esteem, concerns about health, hidden aspirations, stress.

External is the family, career, contributions to society, philanthropy, new experiences.

I learned that we must subordinate ego to truly create an external focus professionally and personally. It occurred to me at long last that meeting my critical objectives was far more important than triumphing over others at every opportunity. I didn’t need the best office, only a good one; I didn’t require 100 percent unanimity, just enough support to achieve my purpose. I learned that consensus is something you can live with, not something you die for.

We often suffer the most when we lead with our egos. You can see the person in the meeting who tries to get the “right” answer before all others in front of the boss, or who cuts off colleagues to suggest her solution first. I have a strong ego, in the sense that I’m very confident and am not intimidated in any business or social situation. But I’ve learned to allow my presence to speak for itself, rather than speaking to demonstrate that I’m present.

Here’s what I mean: I meet some people who immediately tell me, on any pretext at all, that they were quoted in the New York Times or that they’re just back from Venice or that they once understudied on Broadway. It’s their opening salvo—the same as me drawing my guns in the old days, trying to “wow” the other person immediately to establish superiority. Yet it’s far more powerful to simply comment during conversations using your experience and learning.

“The David is breathtaking, we were fortunate to get to Firenze to see it a year ago.”

“I agree with you about Far Niente and Heitz Cellars, what other big California red wines do you favor?”

As I mentioned, you’re reading my sixtieth book. An overbearing woman was introduced at dinner the other night, a relative of one of my best clients, and she regaled me with her accomplishments. When she asked me what I did, I said, “I write a little.” She said, “How nice, have you ever actually written a book?”

“Yes,” I said, “more books on consulting than anyone in history.” She was quite subdued after that.*

This chapter is about pain, not suffering, and I’m addressing it here in a slightly different way. It’s painful to continually argue with people, and you will be made to suffer, if they can manage it, at some future point. (It’s tough to refuse the suffering imposed by relatives or bosses.) If you subordinate your ego—don’t forsake it or deny it, merely subordinate it in the moment—you’ll have a totally different approach to gaining influence or even denying influence to others who don’t merit it.

I knew I had “made it” when I didn’t constantly have to prove myself to others. In many cases, colleagues do this for you, extolling your accomplishments for those unfamiliar with you in a kind of social evangelism. But in most instances, your presence is sufficient: knowing when to interject and when to accept, when to suggest and when to merely approve.

I was waiting to speak at an event with about two hundred people, sitting at a table in the rear of the room. The woman next to me looked at my initials monogrammed on my shirt cuff, and the same initials on my pen, and my name on my briefcase. She looked at me and said quite innocently, “Are you afraid you’ll forget who you are?”

Just like my erstwhile insistence on initials, persistence in informing people how good we are, seeking to win every single point, and trying to parade our superiority is not the way to gain wealth, and it’s certainly not the way to achieve any kind of accomplishment without stress. But I feel that many people who begin anything by telling you how good they are or how much they have are displaying initials—trying to remind themselves who they are in their own image of themselves.

But it’s only the image seen by others that matters.

You don’t want to discourage children by never allowing them to win at a card game or checkers or tic-tac-toe. You don’t want to discourage a partner by always cooking something better than he does or taking a better photo, or dancing a tango.

Organizations need to subordinate corporate ego (banks, phone companies, and cable operations are justifiably considered arrogant and uncaring) as much as people need to subordinate personal ego.

If my wife and I hadn’t subordinated our egos at the right times (at least most of the time) we wouldn’t have made it for forty-seven days, let alone forty-seven years.

Afflict the Comfortable; Comfort the Afflicted

Thus far I’ve been discussing your pain and your suffering, with the first largely involuntary and the second mostly voluntary. We all experience pain—physical and mental—but we inflict suffering on ourselves, sometimes for a lifetime.

But what about how we affect others?

James Carville, the brilliant political analyst and operative, was my guest not long ago at my annual Thought Leadership Conference. He has insights into political creatures such as I’ve never heard, especially over some fine Maker’s Mark bourbon. He told a fascinating story when asked why Bill Clinton has such charisma and charm.

Carville related that when Bill Clinton walked into a room—as candidate, president, visitor, guest, whatever—he made it a habit to seek out a person he thought was the most uncomfortable, the lowest “ranking,” the most unlikely to be invited, and immediately strike up a conversation. Carville pointed out that anyone in the room would have dropped whatever they were doing to have the limelight shining on them in speaking with Clinton, but instead he directed attention to the person who needed some confidence and, perhaps, some glory.

I think this is a marvelous practice. I belong to the National Speakers Association, and am in their Speaker Hall of Fame. I belong to the Institute of Management Consultants and have been named a fellow, one of only two people in history with both credentials. As a result, we receive all kinds of initials to use after our names, different color name tags, different seating, and so on, and on, and on. If I wanted, my business card or signature line could look like this:

Alan Weiss, PhD, CSP, CMC, CPAE, FCMC

That and a couple of bucks might get me on a bus.

And this is the way people treat each other, with these tribal signs of hierarchy. It’s as if a lack of initials makes you unintelligent, non-sentient. There are actually people I encounter with two dozen or more stupefying and idiotic initials after their names, all hieroglyphics, all ego driven and vain. When I mentioned this once on Twitter, twenty people left in a huff, all trailing indecipherable initials behind them.

I’m afflicting the comfortable.

The title of this segment derives from early descriptions of Jesus: he comforted the afflicted and afflicted the comfortable. It’s never my intent to cause people pain, but sometimes, I do merely by pointing out the folly in their habits or the nonsense in their reasoning. The suffering they endure is usually a function of whether they continue to combat the argument or insist on converting me to their way of thinking, or whether they can accept other points of view with open-mindedness and lack of threat to their own egos.

Being a contrarian, maverick, or provocateur means that you generally upset the apple cart and rock the boat. (As I write this, the news headline is that former Tour de France champion Greg LeMond is claiming some racers hid small motors in their bikes!) We are going to cause disturbance, disruption, and discontinuities. The productive key to all this is to do so with improvement in mind, and not destruction or vengeance. If you think back to my earlier example of “shooting” everyone in a meeting and then asking, “Shall we do it my way?” you’ll see that the disruption is not positive and is meant to create pain and suffering.

I’ve grown. I think!

Comforting the Afflicted

As in Bill Clinton’s case, we encounter people at work and in our lives who are “afflicted”: with guilt, fear, envy, low self-esteem, a persecution complex, and so on. Sometimes they are simply afraid to speak up, tentative about their ideas. I believe we have to give them permission and even courage.

When I facilitate groups, I make it a habit to call on people from whom we’ve heard very little or nothing at all. I make sure I get back to people on phone conferences who tried to say something but were overrun by more assertive colleagues. I will poll groups to ensure that everyone has an opportunity to speak.

If we don’t engage in this dynamic, we lose important insights, creativity, and ideas. There is zero correlation between volume and intelligence (as I can attest from the oaf sitting next to me at the bar last night loudly proclaiming that New Mexico is the only place to go to escape northern winters. Right, if you’re a prairie dog.).

One of the most powerful techniques in your arsenal is drawing out people who have trouble emerging from their own cones of silence and, often, terror.

Afflicting the Comfortable

Sed quis custodiet ipsos custodes? (Who shall guard us from the guardians?) Juvenal raised that issue millennia ago, and it’s a good question even today.

There are far too many people who are self-satisfied and smug.

Who are these people? And why should we afflict them instead of merely ignoring them?

• They are so self-absorbed that they suck up all the oxygen in the room, demanding things for themselves without considering others. One person is cold and wants the temperature for the room changed without checking with the other thirty people sitting there.

• They not only have their own opinions, they have their own “facts.” They will tell you that money will take care of motivation and complaints, yet research shows that money isn’t a motivator, while reward from the work itself is.

• They have a poverty mentality that they wish to foist on others. Let’s buy cheap seats and sneak up to better, vacant ones during the game. Let’s buy cheap tickets and talk the gate agent into upgrading us.

• They insist that they prevail in matters of taste, not just principle. “Why would you go to that restaurant, I have a much better place we can go.”

A Million Dollar Maverick mindset calls for us not just to rock the boat but, occasionally, to capsize it. It’s our duty to help those who need others’ courage and insights, and to muffle those who think someone died and left them in charge.