As we mentioned in Chapter 4, body image problems often occur when your thoughts and images become fused with facts. Thus, if you feel ugly then your ugliness is taken as a given fact and you assume that others will get the same impression as you. Being fused with your thoughts and images thus makes your reality very unpleasant. Many people naturally respond by trying either to escape from the thoughts and images or to control them, but this means that you miss out on rewarding life experiences. This chapter is about developing a different relationship with your thoughts and images so you can treat them as ‘just thoughts’ or ‘just a picture in my mind’. Your life will be more rewarding when you truly accept your thoughts and images about your appearance because trying to suppress (or ‘control’) them only makes the preoccupation worse and amplifies your discomfort into pain. This chapter also contains a number of practical exercises to help you examine your relationship with your thoughts and refocus your attention away from your mind.

You may have forgotten how to observe the process of thinking because you have become bound up with the content of your thoughts. The first step is to thank your mind for its contribution to your mental health. Try to distance yourself from its endless chatter and commentary and rating of yourself. This is a difficult skill, which will take time and practice to master, using a number of different exercises (described below).

Just as having an infection might give you a fever, emotional problems will affect your thinking. In common with other emotional problems, body shame will drive your thinking in a more negative and extreme direction. This unhelpful way of thinking will in turn make you feel worse, and influence what you focus upon and what you do. It thus plays a key role in the maintenance of your problem.

Two of the founding fathers of cognitive behavior therapy, Albert Ellis and Aaron Beck, both identified particular patterns of thinking linked with emotional problems. The great advantage of knowing the ways in which your thinking might be affected by your body image problem is that you can more readily spot a negative thought and learn to take these thoughts (and images) with a huge pinch of salt. Think of it as body shame propaganda, aiming to keep you preoccupied, distressed, and restricted. Just as people during the Second World War had to learn to ignore the negative Nazi propaganda (aimed at lowering their morale) that invaded their radios, you can learn to notice unhelpful thoughts without believing them to be true.

BODY SHAME THINKING STYLES

Here are some of the more common types of thinking styles that arise in body shame.

Catastrophizing

Jumping to the worst possible conclusion, e.g. ‘someone will notice my nose and make a really upsetting comment.’

All or nothing (black and white) thinking

Thinking in extreme, all-or-nothing terms, e.g. ‘I am either very attractive or very ugly.’

Over-generalizing

Drawing generalized conclusions (involving the words ‘always’ or ‘never’) from a specific event, e.g. ‘because that person rejected me I know I’ll never find a partner.’

Fortune-telling

Making negative and pessimistic predictions about the future, e.g. ‘I know I’ll never get over this.’ ‘I will be unhappy unless my appearance changes.’ ‘If someone saw me without my makeup they’d be really surprised at how bad I look.’

Mind-reading

Jumping to conclusions about what other people are thinking about you, e.g. ‘that person is looking at me, I can tell they are noticing my bad skin and thinking I’m disgusting.’

Mental filtering

Focusing on the negative and overlooking the positive, e.g. paying far more attention in your mind to the one person who was not friendly to you and overlooking the fact that the others were very warm towards you; or tending to overlook the positive aspects of yourself and what you have going for you.

Disqualifying the positive

Discounting positive information or twisting a positive into a negative, e.g. thinking ‘That person was only nice to me because they thought I was repulsive and felt sorry for me. They’ll probably have a good laugh about me with their friends later.’

Labelling

Globally putting yourself down, in an extreme and self-attacking way, e.g. ‘I’m a worthless, hideous freak.’

Emotional reasoning

Listening too much to your negative gut feeling instead of looking at the objective facts, e.g. ‘I know I’m hideous and will end up alone because I feel it deep inside.’

Personalizing

Taking an event or someone’s behavior too personally or blaming yourself, e.g. thinking ‘That person pushed in front of me when I was trying to get on the train because they think my appearance makes me inferior.’ Recognizing this tendency to misinterpret events in the world around you because of your preoccupation with your appearance can help you reduce the extent to which your body image problem causes you distress.

Demands

Rigid ‘should’, ‘must’, ‘ought’, or ‘have to’ rules about yourself, the world, or other people. Demands for certainty can be a particular issue for any kind of anxiety problem, e.g. ‘I must know just how I look so that I can do whatever I can about it. I should always try to look as good as possible.’

Low frustration tolerance

Telling yourself that something is ‘too difficult’, or ‘unbearable’, or that ‘I can’t stand it’, when it’s actually hard to bear, but bearable. It is in your interests to tolerate these things, e.g. experiencing some degree of discomfort as you face your fears.

Another strategy for intrusive thoughts is to label the thought or feeling by saying it out aloud and writing it down. For example:

‘I am having a thought that I am fat.’

‘I am having a memory of being bullied as a child.’

‘I’m having the feeling of being anxious.’

‘I’m making a rating of myself that I am ugly.’

As an alternative, some people find it more helpful to distance themselves from such thoughts by labelling them as products of their mind, e.g. ‘My mind is telling me I am ugly.’

Labelling your thoughts may feel awkward at first, but with practice it will help you to accept your thoughts or feelings without buying into them. Some people find it helpful to speak their thoughts out loud in a funny voice or the voice of a cartoon character. Again, this can help you to distance yourself from your thoughts and de-fuse them from your ‘self’.

The aim of all these exercises is to acknowledge the existence of such thoughts and label them for what they are. It’s usually best not to challenge their content, as they are strongly bound up with past memories and in body image problems that are often rigidly held. As you progress, you’ll discover that you can experience unpleasant thoughts and feelings and still do what’s important for your life, despite their presence. If you keep doing this, they will slowly fade.

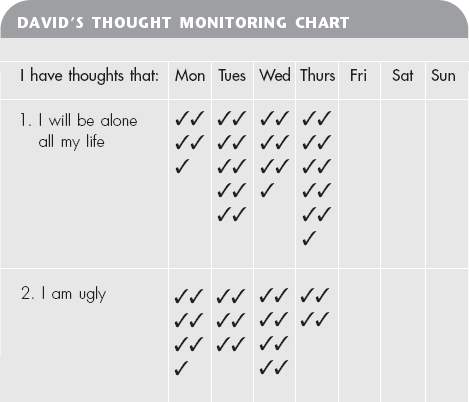

Try making a list of all your recurrent body image thoughts and feelings, label them for what they are, and put a tick in the relevant box each time they occur. Such thoughts are more likely to appear in difficult situations. It can be helpful to monitor them just to see which ones turn up in particular situations and try to bully you. We don’t want you to do this repeatedly – just to see what happens over a few days. You will soon start to develop different ways of looking at your thoughts and not buying into them, brooding, comparing, or paying attention to what your mind is telling you. Here is David’s chart as an example.

A blank thought monitoring chart which you can photocopy can be found in Appendix 2 (page 408). Note that the purpose of monitoring your thoughts is not to challenge their content, or to control or reduce their frequency – just to acknowledge them and to thank your mind for its contribution. If your thoughts are very frequent (and in some people it may be a thousand or more times a day), you might find it easier to use a tally counter and transfer the total at the end of each day to your chart. (You can purchase a tally counter by post. You will easily find a supplier if you type ‘buy tally counter’ into an Internet search engine.) You can also note the situations in which the thoughts most commonly occur in order to see if there is a pattern. It would be useful to know if there is such a pattern so that you can predict what thoughts will turn up and ensure that you are better prepared for them.

You have gathered by now that what we want you to develop is a sense of distance from your thoughts and feelings. This means not buying into them but being aware of them as a passive observer.

This is best illustrated by closing your eyes and bringing to mind, say, a bowl of fruit, then watching it without influencing it in any way. It’s okay if your attention strays away from the orange or if the image changes (for example, the orange falls off the top of the bowl). You should merely be aware of the changing content of your attention without influencing the content in any way. This may not be easy at first, but it’s worth persevering. The technique of distancing your thoughts can also be used just to notice your intrusive thoughts and not to engage with them.

Another analogy for watching your thoughts is to imagine them as cars passing on a road. When you are depressed, you might focus on particular ‘cars’ that tell you that you are a failure and life is hopeless. You cope either by trying to stop the cars or by pushing them to one side (if you’re not in danger of being run over, that is!). Alternatively, you may try to flag the car down, get into the driving seat and try to park it (that is, analyse the idea and sort it out until you feel ‘right’). Of course, there is often no room to park the car and as soon as you have parked one car another one comes along.

Distancing yourself from your thoughts means being on the pavement, acknowledging the cars and the traffic but just noticing them and then walking along the pavement and focusing your attention on other parts of the environment (such as talking to the person beside you and noticing other people passing you and the sights and smells of the flowers on the verge). You can still play in the park and do what is important for you despite the thoughts. In other words, such thoughts have no more meaning than passing traffic – they are ‘just’ thoughts and are part of the rich tapestry of human existence. You can’t get rid of them. It’s just the same as when you are in a city and there is always some slight traffic noise in the background and you learn to live with it. Notice these thoughts and feelings and acknowledge their presence, then get on with your life.

In this exercise, you will need to get into a relaxed position and just observe the flow of your thoughts, one after another, without trying to figure out their meaning or their relationship to one another. You are practising an attitude of acceptance of your experience.

Imagine for the moment sitting next to a stream. As you gaze at the stream, you notice a number of leaves on the surface of the water. Keep looking at the leaves and watch them drift slowly downstream. When thoughts come, put each one on a leaf, and notice each leaf as it comes closer to you. Then watch it slowly moving away from you, eventually drifting out of sight. Return to looking at the stream, waiting for the next leaf to float by with a new thought. If one comes along, again, watch it come closer to you and then let it drift out of sight. Allow yourself to have thoughts and imagine them floating by like leaves down a stream. Notice now that you are the stream. You hold all the water, all the fish and debris and leaves. You need not interfere with anything in the stream — just let them all flow. Then, when you are ready, gradually widen your attention to take in the sounds around. Slowly open your eyes and get back to life.

In Chapter 4, we described how various attentional biases influence your awareness of your feature (pages 68–70). Our attention seeks out the subjects that interest us: it is biased towards those subjects and we become more aware of them. What is on our minds will influence what we notice; it’s just part of how the human brain works.

However, in body image problems, this attention bias towards monitoring how you look is one of the factors that keeps the condition going. Being self-focused means being on the outside, looking in at yourself, with an observer’s perspective and being very aware of your thoughts and feelings. Being externally focused means being on the inside, looking out at the world around you and at what you see or hear or smell. People with body image problems are frequently self-focused and constantly monitoring their felt impression or picture in their mind. You might want to know exactly how you look and therefore how likely you are to be humiliated (although whether this is accurate or not is a different matter). Or you could be trying to avoid the gaze of someone who you think is being critical.

Another situation where self-focused attention occurs is in front of a mirror. We know from research that people with body image problems are more likely to focus on their felt impression and on certain features that are viewed as defective compared with people without a body image problem. Furthermore, when individuals without a body image problem look at themselves in a mirror then they tend to focus more on features that they consider attractive.

Re-focusing your attention onto the outside world gives your brain a rest and allows you to take in what the world has to offer.

Overcoming a body image problem will mean broadening your attention to take everything in, not just focusing on your features and refocusing your attention away from your inner world.

It is important to recognize that biased perception is very likely to lead to biased conclusions. For example, if you constantly live in your head and monitor your impression of how you look, you will feel uglier. Excessive self-focus will also mean that your appearance is much more likely to be on your mind and this will increase the number of hours a day you spend being preoccupied. If you know that you tend to overassume that your features are ugly or likely to lead to humiliation, you can correct your thinking by deliberately acting as if you look OK and are safe from attack.

As we also saw earlier, trying not to notice something, as a way of attempting to correct this bias, is always doomed to failure. (The more you try not to think of the pink elephant, the more you end up thinking about it!) However, you can improve the extent to which you focus on other things. The key question is whether focusing your attention inwards helps you to achieve the goals and valued directions you want.

In summary, most people find that being self-focused causes them to dwell more on the ‘ghosts from their past’ and to feel more preoccupied, which in turn makes them feel worse and therefore likely to do less, and become more self-focused. The alternative is to be less ‘on the outside looking in’ at yourself, and more ‘on the inside looking out’ at the world, and doing what is important to you, despite what your mind is telling you.

In any given situation, especially when you are feeling more anxious or withdrawn, you can estimate the percentage of your attention that is being focused on:

(a) yourself (e.g. monitoring how you appear to others or how you feel)

(b) your tasks (e.g. listening or talking to someone or writing)

(c) your environment (e.g. the hum of traffic in the background).

The three must add up to 100 per cent, and the ratio is likely to vary in different contexts. When you are very self-focused, about 80 per cent of your attention might be on yourself, about 10 per cent on the task you are involved in, and 10 per cent on your environment. Someone without a body image problem might normally focus about 10 per cent on him- or herself, 80 per cent on the task, and 10 per cent on the environment. This is an important observation because it means you can train yourself to be more focused on tasks and the environment and less on yourself.

EXERCISE 6.3: RATING YOUR ATTENTION PERCENTAGES

How self-focused are you? Over the next few days, make a note of different situations (e.g. being in front of a mirror, talking to someone of the opposite sex of the same age, reading, etc.) and then rate the percentage of your attention that is on:

a. yourself (0–100 per cent)

b. your task (0–100 per cent)

c. your environment (0–100 per cent)

d. total percentage (remember the three above must add up to 100 per cent)

e. degree of distress (0–100 per cent)

Try to compare the same situation with a different percentage of attention on yourself. For example, compare talking to someone you know well:

a. being very self-focused (for example 80 per cent of attention on self or your felt impression) with

b. concentrating on what you are saying and really listening to your friend (for example, 80 per cent attention on the task).

How does your degree of distress compare in (a) and (b)?

What effect does your change in attention focus have on your friend? Does he or she find you warmer and friendlier?

We hope we have convinced you that it would be helpful to reduce your self-focused attention. When this is difficult, you can use specific exercises that have been proven to help people focus their attention better on the outside world. Think of these exercises as helping you to build the psychological muscle that places your attention on the world around you, rather than on yourself.

The first technique is called ‘task-concentration training’ (TCT), and it was devised by the psychologist Sandra Bogels in the Netherlands. This technique requires practice within progressively more challenging situations.

The technique is that every time you notice that your mind is self-focused (say, above 50 per cent) then you should immediately refocus your attention on to the task or the environment.

Practise being absorbed in a particular task (e.g. having a conversation) and, when you notice your attention is drawn towards yourself, deliberately refocus your attention away from yourself onto something else around you. Similarly, if you tend to focus all the time on how you feel, refocus attention outside yourself on some practical task in hand or on the environment around you. Every time you notice your mind’s endless chatter and focus on how you feel, refocus your attention back on to the task or your environment. As a guide, try to aim for self-focused attention in most contexts to be reduced to 30 per cent or less.

If you are alone and have no specific task to do, you will need to refocus on your environment and make yourself more aware of:

• the various objects, colours, people, patterns and shapes that you can see around you (e.g. fabrics, decor, cars on the street, trees, litter)

• the sounds that you can hear (e.g. the hum of a heater, the sound off traffic, a clock ticking)

• what you can smell (e.g. scent of flowers, traffic fumes, fresh air, fabric softener)

• what you can taste (in the case of food or drink)

• the physical sensations you can feel from the environment (e.g. whether it is hot or cold, whether there is a breeze, the hardness of the ground beneath your feet)

This training is done in a graded manner for specific situations. For example, if you experience marked anxiety in social situations, you can practise the exercise starting with easier situations (e.g. listening to someone telling you about his or her holiday) and moving on to the most difficult situations (e.g. being at a party with strangers). This exercise is normally combined with the exercise in exposure and dropping safety behaviors from Chapter 7 (see page 178). You should also keep a record of each exercise on the self-focused attention chart from this chapter (see page 184).

You and another person (e.g. a relative or friend or a therapist) sit with your backs against each other (so that there is no eye contact). Then other the person tells you a two-minute story (e.g. about his or her holiday). You must concentrate on the story (task) and summarize it afterwards. You should estimate the percentage of your attention that was directed towards your self, towards the task, and towards the environment. Then both of you should estimate the percentage of the story you were able to summarize. The exercise is repeated until the concentration directed towards the task is at least 51 per cent (more than half the total).

You and the other person now turn your chairs, so that you make eye contact. The other person tells you another two-minute story. As in the first listening exercise, you have to concentrate on the story and summarize it afterwards. You should then estimate the percentage of attention directed towards your self, the task, and the environment. Then both of you should estimate the percentage of the story you were able to summarize. Typically, you may become more self-focused because of the eye contact with another person, and, as a result, memorize less of the story than in the first exercise. Think about how this relates to everyday life. The exercise is repeated as before until the concentration directed towards the task is at least 51 per cent.

The other person tells you another two-minute story. Try to distract yourself while listening by looking at your appearance in a mirror (and then try to concentrate again on the story). As in the first listening exercise, estimate the percentage of attention directed towards your self, the task, and the environment. Then both of you should estimate the percentage of the story you were able to summarize. Typically, you may become more self-focused while thinking about your feature, and, as a result, have gaps in the summary of the story at the moments where you thought about the problem. Think about how this relates to problems in your everyday life. Repeat the exercise as before, until the percentage of concentration directed towards the task is at least 51 per cent.

The other person tells you another two-minute story, which involves worries about being rated (e.g. meeting somebody who has a large nose, if this is the main feature that concerns you).

All four exercises need to be repeated until at least 51 per cent of your attention is focused on the task. The effect of the more complex elements in the later exercise means that most people will become more self-focused as a result, but are able to re-focus on the task after some practice.

The speaking exercises are practised in the same way as the listening exercises. This time you tell a two-minute story to the other person, while concentrating on the task (speaking and observing whether the other person listens and understands what he or she is being told). The other person listens. The speaking exercises are repeated in the same way as in the second, third and fourth listening exercises (above) until your attention on the task is greater than 51 per cent.

Practise focusing your attention in non-threatening, everyday situations. An example is walking through a quiet park. You should pay attention to all aspects of the park (what you see, what you hear, what you smell) as well as to each one of your own bodily sensations while walking.

Another example is to listen to music, first to each instrument separately, then to all the instruments at the same time. Focus your attention first on one instrument, and then on all aspects of the music together.

Draw up a list containing approximately ten social situations in which you are anxious. Arrange these situations in a hierarchy, with the first item being the least fear-inducing. This exercise can be combined with the exposure exercise on page 178, and repeated until the attention you place on the task is greater than 50 per cent.

Your goal is to employ task concentration in each situation and quickly re-focus attention to the task after being distracted by fear of being rated. The exercises are built up hierarchically, since in very fear-inducing situations the feelings will absorb most of your attention. As a result, directing your attention to the task is more difficult. It takes practice to train your brain to stay focused on the world around you and away from thoughts and feelings related to your appearance.

The second technique is called ‘attentional training’ and it was devised by the psychologist Adrian Wells from Manchester University. It will help you reduce self-focused attention in the long term and increase your flexibility at switching attention.

This technique has been shown to be of some benefit in depression and some anxiety disorders for reducing self-focused attention in the long term. It is a form of mental training, like going to a psychological gym and getting your attention muscles in shape. It is also something you can practise at home, rather like practising a musical instrument at home in readiness for playing with an orchestra.

The following exercise should be practised when you are alone and not distracted. In other words, this is not a technique you should use to distract yourself when you feel upset or are brooding. In the long term the training can help you to interrupt the cycle of being self-focused so that you eventually become more naturally aware of your external environment. The technique may seem difficult at first but it is worth persevering and doing it in small steps.

You can monitor how self-focused you are at any given moment on a scale of between –3 and +3, where –3 represents being entirely focused on your own thoughts and feelings or the impression you have of yourself, and +3 means being entirely externally focused on a task (e.g. listening to someone) or the environment (e.g. what you can see or hear). A zero would indicate that your attention is divided equally between being self-focused and externally focused. Being excessively self-focused is a rating of –2 or –3.

The exercise involves collecting together about nine sounds that you can hear simultaneously. Examples could be: the hum of a computer, the noise of a water filter in an aquarium, a tap dripping, a radio at a low volume, a hi-fi, a vacuum cleaner in a room outside and the noise of traffic. Label each sound – for example, sound number one, the hum of the computer. Try to ensure that one or two sounds do not drown out the others. Sit down in a comfortable chair, relax and focus your gaze on a spot on the wall. You should keep your eyes open throughout. You may experience distracting thoughts, feelings or images that just pop into your mind during the exercise. This doesn’t matter – the aim is to practise focusing your attention in a particular way. Also, don’t blank any thoughts out or try to suppress them while you are doing the exercise.

The exercise consists of three phases. In the first phase, focus your attention on each of the sounds in the sequence in a sustained manner. Pay close attention to sound number one, for no other sound matters. Ignore all the other sounds around you. Now focus on the sound number two. Focus only on that sound, for again no other sound matters. If your attention begins to stray or is captured by any other sound, refocus all your attention on sound number two. Give all your attention to that sound. Focus on that sound and monitor it closely and filter out all the competing sounds, for they are not significant. Go through all the sounds in sequence until you have reached sound number nine.

Now move on to the second phase. You have identified and focused on all the sounds. In this next stage we want you to rapidly shift attention from one sound to another in a random order. For example, you could pass from sound number six to number four to three to nine to one, and so on. As before, focus all your attention on one sound before switching your attention to a different sound.

Then move on to the third phase. Expand all your attention, make it as broad and deep as possible and try to absorb all the sounds simultaneously. Mentally count all the sounds you can hear at the same time.

The exercise needs to be practised twice a day (or a minimum of once a day) for 12–15 minutes. If possible, try to introduce new sounds on each occasion so you don’t get used to them. We appreciate that this is difficult. Keep a record of your attention training on the form below. Like physical training, the exercise needs to be practised repeatedly or your attention muscles won’t get bigger.

If you are excessively self-focused, and you are having difficulty in switching your attention externally, it can be helpful to explore (a) the contexts in which you tend to be self-focused; (b) the pay-off you think you get from being self-focused; and (c) the motivation for being self-focused. For example, some people might use the picture of themselves as a portable ‘internal mirror’ that can be easily carried around with them. Thus, you might want to check your appearance internally so you can know exactly what you look like at all times (and especially when there is no external mirror available). After you have completed the exercises on the following pages it will be helpful to discuss what you have written with a trusted friend or therapist.

EXERCISE 6.4: THE A, B, C, D, E OF SELF-FOCUSED ATTENTION

Activating Event

Describe a recent typical situation in which you were excessively self-focused:

Behavior

Describe what you were doing. For example, were you checking the picture in your mind to see how you looked?

Immediate Consequences

Was there any pay-off from being self-focused? Did it give you a sense that you were taking action to prevent something bad from happening?

Unintended Consequences

What effect did being self-focused have? Did it make you more distressed or preoccupied with your appearance?

What effect did being self-focused have on the people around you? Did you appear to be less friendly or warm?

Alternative Directions

Could you be more externally focused on an activity that is consistent with your goals and valued directions?

Effect of Alternative Directions

What effect did following your alternative direction have?

Identifying a pattern

Can you see a pattern to the way you cope? What are the typical situations in which you are self-focused? Is there a pattern to these situations that you could change? Can you do anything to prevent such situations?

EXERCISE 6.5: QUESTIONING YOUR MOTIVATION FOR BEING SELF-FOCUSED

What is your motivation for being self-focused? Do you sometimes think that being self-focused could help you? Do you feel as if it might prepare you for being humiliated or something bad happening? Try to write down your motivation in the form of an assumption. (For example, ‘If I am self-focused I can prevent others from humiliating me.’)

The types of questions to ask yourself are:

• Does this assumption or rule about being self-focused help you in your goals and valued directions in life?

• Would you recommend to others checking in an internal mirror or being self-focused? If not, why not?

• Is it possible that the picture in your mind is different from how others might see you?

• What doubts do you have about being externally focused and concentrating on what you see, hear and smell?

• Can this assumption be made more flexible?

• Is the cost of being self-focused too high?

Now decide whether holding such assumptions about being self-focused is really helpful and whether you could try an alternative – being externally focused. Write down what you plan to focus on in your external environment.

We described earlier in this chapter how people often have thoughts or images about the way they look that just pop into their minds. Brooding is different and describes a reaction to an intrusive thought or image. It may also be described as ‘ruminating‘. This is a word derived from the term used for the way cows or sheep naturally bring up food from their stomachs and chew the cud over and over again. It describes perfectly the way a person thinks for long periods of time, going over something in their mind time and time again. Sometimes thinking can be productive and creative in terms of trying to solve a specific problem. However, it is not productive when it involves thinking excessively about past events or questions that cannot be resolved.

There may also be a relentless stream of thoughts comparing yourself to others. These are self-critical, self-attacking thoughts. Your mind can be made up of different parts, which may be in conflict (e.g. one part may want to eat some chocolate and another part tells you that would be stupid when you want to lose weight). When you attack yourself, one part of your mind may tell you, for example, ‘You are so ugly compared with him’, or ‘You deserve to look like an alien’. Such thoughts tend to make you fall into submission and you can end up feeling very small.

Other examples of self-attacking thoughts are:

You’re disgusting |

You’re a failure |

You’re stupid |

|

||

You’re inferior |

You’re useless |

You’re worthless |

|

||

You’re inadequate |

You’re not good |

You’re bad |

|

||

|

enough |

|

|

||

You’re unlovable |

You’re worthless |

You’re defective |

|

||

You’re repulsive |

You’re nothing |

You’re a freak |

People with body image problems tend to put themselves down about:

• their appearance

• having an emotional problem and not being able to ‘pull themselves together’

• having done something that may have worsened their appearance

• the consequences of having a body image problem, such as not having a partner.

Here are some examples of what we mean:

• George, who was preoccupied with the idea that his eyes were too big, attacked himself for being ‘a freak’.

• Harry viewed himself as a ‘total idiot’ because he believed that pushing certain areas of his face, initially in an attempt to improve his appearance, had made his looks worse.

• Sarah thought she must be unlovable because she didn’t have a boyfriend, although it was really her BDD that meant she tended to stay at home and made it very difficult for her to meet men.

Brooding or self-attacking can lead to a number of unintended consequences, such as:

• feeling more distressed about your appearance

• feeling more depressed

• thinking more about bad events from the past

• believing thoughts in which you put yourself down

• being more pessimistic about the future

• being less able to generate effective solutions to problems and less confident in the ones you do generate

• becoming more withdrawn and doing less of what is important to you

• becoming more likely to be ignored and criticized by others.

When most people brood, it makes them feel worse and they are more likely to avoid getting involved in life. Any counselling that encourages you to search endlessly for reasons why you have a problem can also encourage you to brood.

By contrast, excessive worry is thinking about all the possible things that could go wrong in the future (also called ‘catastrophizing) which will make you more anxious. Many people with body image problems therefore use a mixture of brooding and worrying, depending on their mood. When you are more depressed brooding tends to focus on the past, with ‘Why?’ types of question, for example: ‘Why did I have that surgery?’, or ‘Why was I born this way?’ There are variations on this theme, including fantasy thinking, which starts with ‘If only’, for example: ‘If only I could look better’; ‘If only I could win the lottery and get the surgery done’. By contrast, worries tend to start with ‘What if’ type of questions, for example, ‘What if my make-up doesn’t hide my spots today?’

The first step is to monitor yourself to see in what times of day, places, and situations you brood and how often you do it. You can do this with a tally counter or a simple tick chart for whenever you ruminate (use the same chart below). This awareness will help you to change your behavior.

Now you have understood how difficult brooding is to stop and how powerful these thoughts can be when they are pulled by emotions. However, they can also be very harmful and we are now going to show you ways in which you can begin to escape the power of brooding.

The first step in understanding brooding, self-attacking thoughts and worries is to do a functional analysis on the process. Work out the unintended consequences of your brooding or worrying or self-attacking below.

Your goal will be to stop engaging in the content of your brooding or worries and not respond to the incessant demands. As soon as you have noticed yourself brooding or worrying, refocus attention outwardly on the real world. Choose to do something that you value and which is consistent with the goals that take you closer to long-term reduction in preoccupation with your appearance. Then monitor the effect of this change. This means having a realistic plan or timetable for the activities you are avoiding and what is important in your life rather than doing what you feel. Eventually you will be able to stand back and observe your thoughts, not buy into them and act in a valued direction in your life.

EXERCISE 6.6: THE A, B, C, D, E OF BROODING, WORRYING OR SELF-ATTACKING

Activating Event

Describe a recent typical situation in which you were brooding, worrying or attacking yourself. Did it start with an intrusive thought, image or memory? What were you doing at the time?

Behavior

What did you tell yourself? Was it a ‘Why’ or ‘If only’ question? Were you trying to find a reason? Can you label it as an example of brooding, worrying or self-attacking, or some combination of the above?

Immediate Consequences

Was there any pay-off from brooding or worrying? Did you avoid anything that was uncomfortable as a result of brooding or worrying?

What effect did the brooding, worrying or self-attacking have on the way you felt?

What effect did it have on how self-focused you became on a scale between –3, which is totally focused on what you were thinking, to +3, which is totally focused on environment or tasks?

What effect did brooding, worrying or self-attacking have on the time you could devote to what is important in your life?

What effect did the brooding, worrying or self-attacking have on your environment or the people around you?

Did you do anything in excess as a consequence (e.g. drink more, use drugs, binge-eat, purge?)

Overall, how helpful was it to buy into your brooding, worrying or self-attacking?

Alternative Directions

What alternative direction could you find that are consistent with your goals and valued directions instead of brooding or worrying?

Effect of Alternative Directions

What effect did following your alternative direction have?

Is there a pattern to the situations that are typically linked to brooding, worrying or self-attacking that you could change? For example, can you do anything to prevent such situations?

As we mentioned earlier, a common preoccupation in body image problems is to try to find reasons for why you look the way you do or what you should have done in the past. The problem is that this type of enquiry takes your mental focus straight back into your mind (trying to solve it as an appearance problem) again, whereas your aim should be to focus on the ‘here-and-now’ problems in the outside world – like being a good partner, a good parent, employee and member of the community.

Sometimes people brood because they feel they have a good reason to do so. If you are struggling to stop brooding or worrying, it may be helpful to understand your motivations about brooding (or your thoughts about your thoughts). Here are some examples of the motivations that people with body image problems give:

• ‘I can prepare myself for the worst.’

• ‘I can figure out where I went wrong and I won’t make the same mistake again.’

• ‘If I don’t it will let people who have hurt me off the hook.’

• ‘It means I don’t have to think about the bad things that are happening now.’

People can hold positive motivations about worrying (e.g. ‘I must worry in order to think through all the things that could possibly go wrong’) as well as recognizing the negative consequences, (‘If I worry, then I will go crazy and I won’t be able to think straight’). Not surprisingly, this brings on more anxiety and depression. Feeling anxious and depressed will pull you back into brooding and being self-focused. Learning to distance yourself and break free from your emotions is tough and requires a lot of practice.

Do you sometimes think that brooding or worrying could help you? Do you feel as if you need to prepare yourself for being humiliated or something bad happening? Try to write down your assumptions about the benefits of brooding or worrying, e.g. ‘If I brood, then I can prepare myself for the worst.’

1._______________________________________

2._______________________________________

3._______________________________________

Now ask yourself:

• Does this assumption about brooding help me in my goals?

• Can this rule about brooding or worrying be made more flexible?

• Does my assumption help me to follow the directions in life that I want to follow?

• Is the cost of brooding or worrying too high?

• While I hold this assumption about my brooding or worrying, do I become more preoccupied and act in ways that are unhelpful?

• For how long am I going to carry on with my solution?

Now decide whether holding such assumptions about your brooding is really helpful. Then write down some alternatives you can try.

1._______________________________________

2._______________________________________

3._______________________________________

4._______________________________________

People who are critical of themselves (feeling, for example, that they are ugly, weak, or pathetic) might also have reasons for allowing themselves to be bullied by their minds. It is often helpful to ask yourself: What is my greatest fear if I give up criticizing and bullying myself? Criticism can also act as a warning (‘If I don’t tell you how fat you are and you don’t lose weight, then nobody will love you’). Sometimes self-criticism can be triggered by a memory or be linked to your identity. Examples of assumptions behind self-criticism in depression are:

• If I don’t put myself down, then I’ll be arrogant.

• If I don’t get in first with criticism, someone else will.

• I attack myself so I can improve myself.

• I attack myself so I get the humiliation I deserve.

• If I don’t criticize myself, I’ll get fat.

This sort of reasoning is probably an important factor in maintaining long-standing depression and low self-esteem. You might like to consider the costs and benefits of keeping up such a strategy.

What do you think is your motivation or the assumptions behind your self-attacking thoughts?

1._______________________________________

2._______________________________________

3._______________________________________

4._______________________________________

• Does self-attacking make your preoccupation and mood worse?

• Does it help you achieve the goals you have set yourself?

• Does it help you stick to your valued directions in life?

• Is self-attacking something you would teach a friend or relative in a similar position? If not, why not?

Having identified what you believe to be the costs and benefits of self-attacking, you could talk these ideas through with a friend or health professional to see whether self-attacking helps or whether there is an alternative to your strategy. You might want to consider whether an alternative compassionate approach might help you to achieve the goals you want in life. Compassion is putting yourself in another person’s shoes and being able to understand their emotional experience and be moved by it. It means being non-judgmental and sensitive to the distress and needs of your mind. Thus it is very understandable for your mind to want to try and protect you and prevent you, for example, from being arrogant or being rejected. However, there are other ways of achieving the same goal. It may be helpful to talk to someone about an alternative that does not lead you to feel more distressed and to miss out on life.

Another activity that takes up a lot of mental time in body image problems is trying to solve the wrong problems. Problemsolving is a good skill to have if the problem is current and exists in the real world, but not if it doesn’t. For example, if your car has broken down and you have to get to a job interview, you could brood on ‘Why does this always happen to me?’ (and just make yourself more frustrated and depressed). Alternatively, you could worry about ‘What if I don’t get the job?’ (and make yourself more anxious). You can problem-solve only if you can turn brooding into a ‘How?’ question. For example, you could ask yourself: ‘How am I going to get to the centre of town on time? I could ring for a taxi, but that will be a bit expensive. I could get a train, but I might now miss the one that would get me there in time. Getting this job is important, so I’ll take a taxi.’ The most important point is to solve only existing problems or ones that you can do something about. You can also practise for an event, though there aren’t that many situations where this applies. For example, if you have an interview coming up, then you might ask a friend to do a role-play and practise being interviewed.

People with body image problems might spend a lot of time trying to solve the wrong problem in their heads. They will spend hours making mental plans about how a ‘defect’ can be fixed or camouflaged (e.g. ‘If I can get my nose fixed, then I can do things I want to do in life’ or ‘If I can get the right skin product, then it may fix my skin’). Mental planning might appear to instil hope but it usually leads to an endless search for solutions that never help (or make it worse) or do not reduce the preoccupation or distress. If you try to solve it as an appearance problem, rather than an emotional problem, then it will increase your preoccupation and distress about your appearance. If you treat it as an emotional problem, it has a completely different solution. Instead you start to focus on what you are avoiding in life and what you want your life to stand for. You can then begin to test out alternatives to see whether the bad things you are predicting actually happen, or whether there are better ways of coping with the bad things that might happen (for example if you are rejected).

EXERCISE 6.7: THE A, B, C, D, E OF MENTAL PLANNING AND TRYING TO SOLVE THE WRONG PROBLEM

Activating Event

Describe a recent typical situation in which you were mentally planning or investigating a solution for what you believed to be an appearance problem.

Behavior

What mental plans were you making or what did you do?

Immediate Consequences

Was there any pay-off from mental planning and investigating? Did it give you a sense of hope that you were doing something to solve your ‘defect’? Did you avoid anything in life that you find difficult?

What effect did the mental planning have? Did it eventually make you more frustrated or angry?

What effect did your mental planning have on how self-focused you became on a scale between –3, which is totally focused on what you were thinking, to +3, which is totally focused on your environment or tasks?

What effect did the mental planning have on the time you could devote to your valued directions and what is important in your life?

What effect did your mental planning have on the people around you?

Did you do anything in excess as a consequence (e.g. drink more, use drugs, binge-eat, purge)?

Overall, how helpful is it to do your mental planning?

Alternative Directions

What alternative direction could you find that is consistent with your goals and valued directions instead of mental planning?

Effect of Alternative Directions

What effect did following your alternative direction have?

Is there a pattern to the situations that are typically linked to mental planning, worrying or self-attacking that you could change? For example, can you do anything to prevent such situations from occurring? Can you plan the day using an activity schedule that follows your valued directions? What can you do to stop yourself from being alone at certain times?

Another repetitive thinking pattern in body image problems is to compare your feature with someone else’s and then judge yourself against that feature. Comparing is fairly common in people without body image problems (especially in women) but it occurs more frequently in people with body image problems. People typically compare the feature they don’t like with the same feature in someone else of the same age and sex. They may compare themselves with air-brushed models in the media or people they meet in everyday life. There is nearly always an upward comparison with people who have the same feature that is considered more attractive. Alternatively, you may compare your feature with the way the same feature looked in the past.

The first step is to monitor yourself to see in what contexts (times of day, activities and situations) you compare and how often you do it. Being more aware of when you are comparing will help you change your behavior. Self-monitoring, using a tally counter, can increase your awareness of your comparing tendency, as it may be occurring many hundreds of times a day.

The motivation for comparing is usually to know where you stand in relation to someone else as a form of threat monitoring (e.g. ‘I have to know where I stand in case I am humiliated’). This usually leads to safety-seeking behaviors such as keeping your head down and trying to camouflage your ‘defect’. This makes sense if you are an animal – for example, a puppy will roll over in front of a larger dog and be submissive. This strategy is highly effective at avoiding a conflict and preventing the puppy being harmed. However, when you ‘roll over’ this is another example of treating the body image issue as an appearance problem and has a number of unintended consequences.

Try to understand the function of your comparing using the table below. Instead of comparing, we would encourage to you broaden your attention to all the sights, sounds and smell and textures around you or focus on the whole of a person’s appearance rather than just a part – and to fully listen to what another person is saying.

EXERCISE 6.8: THE A, B, C, D, E OF COMPARING

Activating Event

Describe a recent typical situation in which you compared your feature? What were you doing at the time?

Behavior

Who or what did you compare yourself with?

Immediate Consequences

Was there any pay-off from comparing? Did you think it prevented something bad from happening?

Unintended Consequences

What effect did the comparing have on the way you felt?

What effect did it have on how self-focused you became on a scale between –3, which is totally focused on what you were thinking, to +3, which is totally focused on environment or tasks?

What effect did the comparing have on your valued directions and the time you can devote to what is important in your life?

What effect did the comparing have on the people around you?

Did you do anything in excess as a consequence (e.g. drink more, use drugs, binge-eat, purge)?

Overall, how helpful was it to compare?

Alternative Directions

What alternative direction could you find that is consistent with your goals and valued directions? What could you do instead of comparing?

Effect of Alternative Directions

What effect did following your alternative direction have?

Is there a pattern to the situations that are typically linked to comparing that you could change? For example, can you do anything to prevent such situations occurring? Do you need to buy that celebrity magazine? Can you put old photographs back in the album, etc?