Any attempt to solve a problem is only as good as the definition of what the problem is. Imagine that the light-bulb in a room stopped working. Naturally you might assume that the problem is that the light-bulb has broken, and go ahead and change it. However this would not be an effective solution if a fuse on the light circuit had blown. The light will never work if you make the wrong assessment about what the problem is and therefore use the wrong solution. In the same way, if you have a body image problem, then you probably see your appearance as the problem. However, in this chapter we can start to build a more accurate explanation of the problem and of how it is being maintained. Only when we have agreed on the true nature of the problem can we find helpful solutions to it.

How many hours a day do you spend thinking about the feature you dislike? For many people with a body image problem, the feature they dislike is at the forefront of their mind for between one and several hours a day. (For some people, it is on their mind all day and sometimes they dream about it as well.) Can you recall the last time anything else in your life occupied that much time? Being preoccupied with or thinking about your features is at the very heart of body image problems. Anything that brings your feature to the forefront of your mind is part of the problem. This includes even positive feedback on your appearance or ‘helpful’ suggestions about how you could improve your looks.

How will it ever be possible to put your worries about your appearance to the back of your mind, and get on with what is important in your life, if your actions keep bringing your appearance back to the forefront of your mind? Even if some of things you do (such as checking in a mirror) temporarily reduce your doubt and help you to stop feeling bad, they are very much part of the problem because they serve to prime your attention and re-train your brain that appearance is highly important. In this chapter, we shall therefore discuss the different ways we maintain body image problems, often without realizing that we are doing so.

Perception is the way we make sense of what we see or hear or smell. In the previous chapter, we saw that many people with a body image problem have lost their ‘rose-tinted glasses’ and in some ways have a heightened sense of awareness of particular aspects of their appearance.

Imagine, for a moment, that a pair of identical twins have been brought up separately. One of them has a body image problem and the other does not. The one without a problem has a positive slant and rates herself as slightly more attractive than others would rate her. When she is in front of a mirror she focuses her attention on those features that are more attractive and less time on those features that are less attractive. The other twin (who has a body image problem) tends to focus on the features that she considers ugly and ignore the features that are more attractive. In addition, she rates the features that she hates as being important in defining who she is. For example if she is preoccupied and distressed by her hips and tummy, she tends to see herself as a walking pair of hips and wobbly tummy and not much else. This twin has a different way of rating her appearance because she has lost the positive slant used by the twin without a body image problem. She focuses her attention on those features that are less attractive and bases her rating of herself on those features. For these reasons and others, the effects of a cosmetic procedure would be unpredictable, as the surgery might not alter her heightened sense of awareness of her appearance or give her back a positive slant. Neither would a cosmetic procedure affect some of the emotional links with ‘ghosts from the past‘ that are still influencing her in the present.

The twin with the body image problem might say she does not want to be ‘deluded’ into thinking that she looks ‘OK’ when she does not, as she fears that she will then be humiliated or rejected when she is not expecting it. However, this reaction is not surprising, as being over-aware of your features fuels the fear of being humiliated.

EXERCISE 4.1: WHICH FEATURES DO YOU VIEW AS ATTRACTIVE AND UNATTRACTIVE?

Complete the following statements. Describe each feature that you view as ugly or unattractive and say what you think is wrong with it.

I focus my attention on the following features that I view as ugly or ‘not right’:

1. ____________________________________

2. ____________________________________

3. ____________________________________

4. ____________________________________

I focus less attention on these features, which others view as being attractive:

1. ____________________________________

2. ____________________________________

3. ____________________________________

4. ____________________________________

Intrusive images are pictures or felt impressions that just pop into your mind, especially when you are more anxious in social situations or in front of a mirror. Images are not just pictures in your mind but can also be felt sensations or impressions you have of how you appear to others.

People with body image problems often experience such images from an observer’s perspective – that is, as if they are looking back at themselves. They believe that the picture in their mind is an accurate representation of how they appear to others. However, this is questionable, as such pictures might be linked to bad experiences and are like ghosts from the past, which have not been updated. Thus if you have been teased or bullied, and learnt from your tormentors that you were ugly or defective, then that memory becomes ingrained and influences you in the present.

Pictures often reflect and reinforce your mood. For example, if you are very anxious, you might have mental pictures of being humiliated in the future. However, treating images as reality can create many problems. Change involves recognizing that you are just seeing a picture in your mind and that this is not current reality.

When you are ashamed of your body, you may think negatively about your appearance by comparing and rating yourself against others unfavourably. You might judge yourself as ‘ugly’, ‘abnormal’, ‘not right’, ‘too fat’, ‘too masculine’ or ‘too feminine’ or ‘not muscular enough’. You may think that others will view you as inferior, flawed or defective. You probably believe that you are extremely noticeable and that others are looking down at you. It might be just your features that you think others are looking down on; or you might assume that the whole of you is being condemned or humiliated.

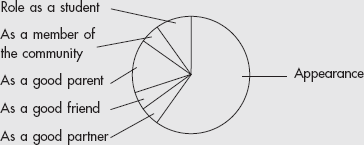

For some people, their appearance becomes the single most important aspect in defining them as individuals and they hold attitudes such as ‘I am my nose’ or ‘My skin defines who I am’. If you hold such an attitude, and are satisfied with your appearance, then you may be worried and anxious about losing your looks. If you are dissatisfied with your appearance, then you are more likely to brood on how helpless you are to do anything to change it.

We hope to show you that your appearance is only part of who you are, and that, even if you are visibly very different from other people, this does not mean you can or should define yourself by your defect.

EXERCISE 4.3: SELF-DEFINITION PIE CHART

The amount of importance someone attaches to their appearance in defining their ‘self’ identity can be represented by a pie chart. In the following example, Amy has filled in a pie chart to show how she defines herself. The divisions in the chart show the relative importance she gives to her appearance and to her roles as partner, friend, parent, member of the community and student. Below the sample, there is an empty pie chart for you to complete.

1. Amy’s completed pie chart

2. Empty pie chart for completion. Indicate how much of the pie is focused on your appearance and how much on all your other roles.

One of the problems in body image disorders is that your thoughts become fused with reality and accepted as facts. As a consequence, you develop a pattern of thinking that is like holding a prejudice against yourself. The same process may occur with the picture in your mind or the felt impression of how you appear to others; your brain fuses the mental picture or impression with reality (the reality that has already lost its positive slant). So what you ‘see’ in a mirror is what you feel (and not what others see or feel and why your loved ones may get so exasperated with you). Fusion is a major factor in keeping body image problems going.

Another way of thinking about this is to consider that what we see in our surroundings is based upon a process that is a bit like waving a torch in the dark. Your mind is constantly creating a picture of the world around you in order to make sense of the world. If your mind is important in creating what you see, then it is not surprising that ghosts from the past and other experiences will influence your body image. From this point of view, what you hear is probably more accurate than what you see. Your mind is less likely to influence what you hear – unless of course you have been conditioned to associate a particular sound with panic.

Later in this book, you will learn how to deal with these thoughts by prefacing them with ‘I am having a thought that I am ugly’, thus underlining that it’s just your thought or a mental event and not reality. Learning to accept these negative thoughts and images willingly as ‘just thoughts’ and not buying into them has been shown to be an important part of overcoming body shame.

EXERCISE 4.4: INTRUSIVE THOUGHTS AND REALITY

What intrusive thoughts do you experience that fuse with reality? List four of them. Then ask yourself: how believable are your thoughts about your appearance? Which of them seems most real to you?

1. ____________________________________

2. ____________________________________

3. ____________________________________

4. ____________________________________

When you are ashamed of your body, you become more focused on your own thoughts and feelings. This makes you more likely to assume that your view of the way you look and the picture in your mind are reality. This in turn interferes with your ability to make simple decisions, pay attention or concentrate on your normal tasks or what people around you are saying. When this problem is severe, it may make you feel more paranoid. Your view of the world now depends on your thoughts and how they chatter away, rather than your experience. In other situations, you may be so focused on comparing yourself with others that you fail to take in the context and find it difficult to concentrate on what people are saying or their body language.

When you have a picture in your mind of the features that you feel look ugly you become self-focused, as you have to monitor exactly how you look when you don’t have a mirror. It’s as if your features are like a dangerous tiger that has to be watched very carefully. Once a threat is on your mind, you will find that this has an impact on what you notice in the world; you develop a bias in your attention and you become more aware of the way you look. In contrast, someone without a body image problem tends to be focused on what they see in their surroundings or on a task (like talking to the person in front of them), rather than looking back at themselves and constantly monitoring how they think they are coming across.

An attentional bias happens all the time in everyday life. For example, when a woman becomes pregnant, she starts to notice other pregnant women and babies everywhere. It is not that there are more pregnant women and babies – just that she is just more aware of them. Another common example occurs when you or someone you know is about to buy a certain type of car. Suddenly it seems as if there are many more of that type of car on the roads. If you were to concentrate now on how your big toes feel, after a minute or so you might start to feel a sensation that you were not aware of before. A person with a spider phobia will notice a spider in a room far more readily than someone without that kind of fear.

People with body image problems are a lot more aware of a feature (or any changes that occur in their appearance) than someone without a body image problem. This ‘attentional bias’ is a result of their over-concern about their appearance, and also contributes to its maintenance, since their personal world can seem flooded with information about the importance of appearance, reinforcing their own sense of the exaggerated importance of appearance. If you have experienced this, you will know that, because your own fears are related to threats about certain features, you are very likely to want to focus on those features. In this way, a vicious circle is set up, whereby the more preoccupied you are with your features, the more you focus your attention on them, further fuelling your preoccupation and so on. We discuss how to overcome self-focused attention in Chapter 6.

EXERCISE 4.5: WHAT DO YOU ‘OVER-NOTICE’?

Take a moment to consider the past day or past week, and complete the following statements. Try to identify the things about yourself that you tend to notice too much. (These are things that your imaginary twin without a body image problem would hardly notice, if at all.)

I’m over-aware of: _________________________

___________________________

The unintended consequences, for myself, of being over-aware of certain features are:

The unintended consequences, for others, of my being over-aware of certain features are:

To tackle this aspect of a body image problem, start by recognizing that biased attention will very probably lead to biased conclusions. For example, if you constantly monitor your feature, you are more likely to rate it as ugly. Once you recognize this, you can correct for this bias in your mind.

Imagine riding a bicycle that tends to veer to the right when you point the handlebars straight ahead. What would you do to make the bicycle go straight? You would correct for the bias by steering slightly towards the left. You can do exactly the same in your mind. So, if you tend to over-assume ugliness, you can correct your thinking by deliberately assuming that most people, most of the time, do not hold the same view as you and do not notice what you are aware of.

However, it is also important to realize that trying not to notice something, in an attempt to correct this bias, is doomed to failure. This is because it is impossible not to think of something – by telling yourself not to think of something, you inevitably focus your thoughts on that very thing! However, later on we will be teaching you how to practise being absorbed in your surroundings, rather than your own thoughts.

Body shame usually consists of a mixture of different emotions. Typically, someone experiences disgust (directed against the self) and anxiety or depression. Disgust is an emotion that means literally ‘something offensive to the taste’. Objects of disgust may include waste products, injuries and wounds to the body, and moral disgust. With disgust, there is a reflex closing up of the muscles around the mouth. When disgust is directed against the self it is called shame, and when it is directed specifically against your own body, it is called body shame.

Shame about your appearance can be broken down into ‘external’ and ‘internal’ body shame. External shame means believing that others think you are unattractive or ugly; this may lead you to feel anxious in social or public situations. People have learnt that it is humiliating or painful to be rejected and therefore try to avoid it. Human beings are social animals. We want to be part of a group, even if we feel under constant scrutiny. External shame is therefore based on what you worry other people think about you.

Internal shame is what you think about yourself. It occurs if you rate yourself negatively, sometimes even feeling a sense of disgust about all or part of yourself. You feel unattractive or ugly to yourself and feel you have to limit the damage to yourself either by avoiding or giving in to others. However, what matters is the sense of not meeting your own standard and being something less than you want to be. Often people continue to feel damaged and spoiled in some way long after the specific events that caused the shame have passed.

Internal and external shame often go together but not always. Thus, someone may rate himself or herself as ugly according to their own standards but know that others are not bothered by it. Equally, someone may believe that others think they are ugly but not care about their opinions.

Shame is not something that we are born with. It is something we probably learn over time. Positive feelings about ourselves usually come from parents and peers when we are loved and given compliments. Thus, from a young age, children develop a sense of pride when they know others feel positively about them and this enables them to feel positive about themselves. We discussed some of these issues in Chapter 3 on how a body image problem develops.

EXERCISE 4.6: INTERNAL OR EXTERNAL SHAME?

How much is your problem driven by concern about what you think others think (external shame)? And how much is it driven by your own standards (internal shame)? For example, would you still have a body image problem if you had a guarantee that no one was thinking negatively about your features? Or would you still have a body image problem if you were completely alone on a desert island and knew that you were not going to be rescued?

Write down one or two thoughts based on external shame, then estimate what percentage of your shame is external.

External:

Now write down one or two thoughts based on internal shame, then estimate what percentage of your shame is internal.

Internal:

You might feel anxious in social situations, or before checking in the mirror, hoping you might see something different from how you think you look in your mind’s eye. However, after you look in a mirror you may feel worse. You might feel disgust as you rate your feature as ugly. During a long session in front of a mirror, some people might experience feeling disconnected from their bodies and a sense of being very unreal. Some might become angry or feel more shame for wasting so much time.

Anxiety is usually triggered by a sense that you are in danger. The threat might be real or imagined and may be from the past (for example, a memory), present or future. When anxiety dominates the picture, your mind will tend to think of all the possible bad things that could occur (‘catastrophizing’) and will want to know for certain that nothing bad will happen in the future. This leads to people worrying about how to solve non-existent problems. The natural desire is to escape or avoid situations that are anxiety-provoking. Anxiety can produce a variety of physical sensations, including feeling hot and sweaty, having a racing heart, feeling faint, wobbly or shaky, muscle tension (for example, headaches), upset stomach or diarrhoea.

If, however, you are becoming despondent about the future, you may feel down or emotionally ‘numb’ or feel that life has lost its fun. These are core symptoms of depression.

Others may frequently feel hurt and angry because they feel they are being unfairly treated and humiliated when they don’t deserve it, or don’t deserve to be born the way they are. They may become irritable or lash out.

If you are feeling stressed by a conflict in a relationship or you have been depressed, withdrawn, inactive and brooding on the past, it will probably make you more self-focused and more preoccupied with how you look, creating a further vicious circle. Anything that improves your mood and decreases other stresses is likely to improve your body image.

EXERCISE 4.7: THE EFFECT OF YOUR MOOD ON YOUR BODY IMAGE

Completing the following statements will help you assess the effect of your mood on your body image.

I feel __________________________________________

When (in what context)?

The unintended consequences of such feelings on my preoccupation with my feature(s) are:

The unintended consequences of such feelings on others are:

Many people with body image problems experience negative thoughts, images, or doubts relating to their appearance. One way of coping is to try to push them out of your mind or to suppress them. Unfortunately, the main effect of suppressing intrusive thoughts is to increase the frequency of the upsetting thoughts and make the person feel worse. This is quite normal, since your brain will keep putting them back into your mind while it is trying to sort them out.

To understand how trying not to think of something increases rather than decreases its intrusiveness, try the following experiment. Close your eyes and try really hard not to think of a pink elephant. For a minute, try and push any image of a pink elephant out of your mind. Every time you think of a pink elephant, try to get rid of it from your mind.

What did you notice? Most people find that, when told not to think of a pink elephant, all they can think of is a pink elephant. Understanding this apparent paradox is the key to understanding and overcoming a body image problem. Many people with this problem are caught in the trap of trying too hard to rid themselves of thoughts and doubts, and in fact this brings about the very opposite of what they want.

If you are still not convinced that trying to get rid of intrusive thoughts, images, or doubts makes them worse, try an experiment. Spend one day dealing with your thoughts in the usual way, and record their frequency and the distress they cause you. Spend the next day trying to get rid of your thoughts or images, and record their frequency and your distress levels. The following day, repeat the first step, and then the next day the second step.

What happened? Most people discover that the harder they try to get rid of their thoughts and images, the more frequent and disturbing they become. If you don’t try so hard not to have the thought or image that’s bothering you, it will bother you much less! After all, a thought is intrusive only if you don’t let it in and recognize it for what it is. Embrace such thoughts, fully accept them and carry them as part of you. You will learn later not to engage with them, as they are, after all, just thoughts.

Trying to avoid or escape from difficult situations is a very natural response and can be the right thing to do in certain situations. For example, it may sometimes be helpful to keep your distance from a bully but at other times you may have to engage with them. It’s all about finding the appropriate response for a particular problem and not avoiding your thoughts and feelings about what seem like bad events. Escaping from difficult thoughts and images is always unworkable.

If you have fused your thoughts with reality and believe them to be true, it’s not surprising that you want to escape from them. In order to escape unpleasant thoughts and feelings, you might start to:

• avoid activities and people that you have previously enjoyed, and become more focused on yourself

• withdraw from friends or family

• spend more time in bed

• use alcohol or drugs to numb your feelings

• brood about the past and try to work out reasons for the way you feel

• avoid calling friends because you think you may be humiliated or rejected

• try to distract yourself with the Internet or DVDs

• ‘put your head in the sand’ and pretend that the problems around you will go away if you ignore them

• ignore the door bell or telephone

Such behaviors become habitual so you may not even be aware of why you are doing them. In many ways, escape is a natural response to try to avoid bad feelings. However, it merely digs you deeper into your hole.

EXERCISE 4.8: CONSEQUENCES OF THOUGHT SUPPRESSION

What thoughts and pictures in my mind related to my appearance am I trying to suppress or escape from?

What are the unintended consequences of trying to suppress or avoid these thoughts and pictures?

Some people cope by trying to ‘put right’ or make sense of past events or their appearance by brooding, constantly mulling the problem over. If this sounds familiar, you are probably trying to solve problems that cannot be solved or analyse a question that cannot be answered. This usually consists of lot of ‘why?’ questions. ‘Why am I so ugly?’ or ‘Why did I get that surgery?’. Another favourite is the ‘if only. . .’ fantasies, as in ‘If only I looked better. . .’. Alternatively, you may be constantly comparing yourself unfavourably with others and making judgements and criticizing yourself. Brooding invariably makes you feel worse, as you never resolve the existing questions and may even generate new questions that cannot be answered.

The process of worrying is a variation on the same theme, in which you try to solve non-existent problems. These usually take the form of ‘What if. . .?’ questions. Examples include ‘What if my partner leaves me?’ and ‘What if I get called names in front of others? Chapter 6 will help you ‘think about thinking’ in more detail and explain how you can best cope with your mind’s tendency to try to solve such worries.

You may also find yourself brooding on why you look the way you do, or why you had a particular cosmetic procedure. This brooding process may reduce your distress for a brief period so you get a payoff because brooding seems to ‘work’. Then the next time you feel bad, you will have trained yourself to brood or avoid activity again. Unfortunately, in the long term this will make you feel more depressed. All the time spent alone means that you miss out on what is important to you in life and prevents you from having any positive experiences. The belief that you are ugly or unlovable is therefore strengthened, as you are unable to test out or disprove your negative expectations.

EXERCISE 4.9: WHAT DO I BROOD OR WORRY ABOUT?

Write down the three things that you most often brood or worry about. For each one, write down the main ‘Why?’, ‘If only’ or ‘What if?’ question.

As well as ways of thinking, people with body image problems use a variety of different behaviors to cope with their condition. However, these strategies usually make the situation worse in the long term. For example, if you have a body image problem you may try to escape from or avoid social or public situations – in severe cases you may become housebound or only go out at night or when you are heavily madeup. This is an example of a ‘safety behavior’, which is intended to prevent harm and reduce anxiety but usually leaves people feeling worse and prevents them from testing out their fears. For instance, you might be:

• repeatedly checking your appearance in a mirror

• seeking reassurance about your feature

• feeling your skin with your fingers

• cutting or combing your hair to make it ‘just so’

• picking your skin to make it smooth

• comparing your feature against models in magazines or people in the street

• measuring body parts to see ‘how bad they are’

• covering up or altering the shape (padding out) body parts using clothing

• styling hair to cover up a flaw, draw attention away from a flaw, or until hair is ‘just so’

• re-touching your hairstyle throughout the day

• using make-up to conceal flaws, or applying it until it is ‘just so’

• re-touching make-up repeatedly throughout the day

• looking for and trying out new beauty products

• researching or seeking cosmetic surgery

• collecting magazines for photographs and appearance-related articles

• making frequent trips to beauty salons or hairdressers

• doing ‘DIY’ cosmetic surgery, having dermatological treatments, and dental procedures

• changing posture or covering a feature with your hand

• avoiding social situations

• avoiding ‘attractive’ people

• being careful about the choice of lighting

• being careful about choice of certain mirrors

• using alcohol or drugs to alter your mood

• using ‘mental’ cosmetic procedures in your imagination

• brooding about the past

It’s worth reflecting on what you think might happen to someone with a relatively healthy body image who practised a number of these activities on a regular basis. We tried this once for just a few hours, and we soon started to become preoccupied and dissatisfied with our own appearance. Thus a further vicious circle has been set up, as the unintended consequence of safety behaviors is to increase preoccupation and distress.

All methods of escaping from a situation or checking how you look are safety behaviors. A message we shall return to over and over again is that safety behaviors maintain your worry. They prevent you from testing out your fears, allow the worry to persist and make the problem worse in the long term. Clearly, you have to stop all your safety behaviors if you are to overcome your body image problems successfully.

Many of these safety behaviors therefore also have an effect on others around you. Examples include:

• Frequently seeking reassurance. This can leave another person feeling frustrated and impotent when they are unable to have a lasting effect (if any) on how you feel.

• Other people thinking you are obsessed with yourself and finding this boring or unattractive.

• Your worries placing restrictions on socializing, reducing your friends’ or partner’s pleasure at seeing you, and increasing your sense of isolation and conflict.

• Your worries about your looks increasing feelings of jealousy, placing strain on a relationship.

• Your worries about your looks restricting physical intimacy.

• Wearing particular types of clothes to hide a feature, which might provoke comments.

• Keeping your head down and avoiding eye contact, leading others to assume that you are not interested in them. They will then back off and you are more likely to think there is something wrong with you

• Being distracted by your worries about your looks causing you to seem aloof or uninterested. This in turn may lead people to be less warm towards you than they would otherwise be.

All these examples show how a safety behavior can leave you trapped in a cycle, where the behavior you have put in place to protect you becomes the problem in two different ways. First, it preoccupies you and prevents you attending to what is really happening. Second, it stops you developing a positive and helpful way of behaving with other people.

The US psychologist Steve Hayes uses a metaphor to describe people who are trying to cope with a body image problem through no fault of their own. Imagine you’re blindfolded and placed in a field with a tool bag. You’re told that this is what life is all about and that your job is to run around this field, with the blindfold on. Now, what you don’t know is that there are some deep holes in this field. So you start running around and enjoying life. However, sooner or later you fall into a deep hole. You can’t climb out and you cannot find an escape route. So you feel inside your tool bag for something you can use to get you out. The only tool is a shovel. So what do you do? You start digging. It’s seems so obvious because you are stuck and can’t get out. Soon you notice you’re not out of your hole, so you try digging faster; but you’re still in the hole. So you try big shovelfuls, you try throwing the dirt far away from you and so on, but you’re still in the hole.

Does this relate to your experience of trying to solve your body image problem? You might be seeking help from this book or going to a therapist in the hope that you can find a bigger or better shovel to help you feel better. Well, the fact is that you can’t dig your way out. However, if you let go of the shovel, you can feel around to see whether there is anything else to help you out – a ladder, for example. Remember, you are blindfolded and you won’t be able to find the ladder or anything else until you drop the shovel. From the perspective of this book, your shovel represents the attempts you are making to control or escape from the way you feel about your appearance.

It is important to remember that, like falling down a hole in the example above, having a body image problem is completely understandable. Yes, life is unfair but it’s not your fault – you’ve fallen down a hole. You have the ability to get out but, before you started to read this book, you did not know what to do, and you did what you did because it seemed natural. We are not saying that the situation is hopeless but, and this is very important, your solutions – trying to avoid or control the way you feel about your appearance – are not working. All they do is make the situation worse and make you feel more stressed and depressed. Remember, working out how you fell into your hole is not going to get you out of it. Some therapies unintentionally provide you with a bigger shovel.

Only when you stop shovelling can you feel around for something to help you out – like a ladder or rope. This may seem like a leap of faith but if you don’t accept the uncertainty, it’s guaranteed to get worse.

The essence of overcoming a body image problem using the various techniques outlined throughout this book is to gather evidence to see ‘which theory fits the facts’. Doing the various tasks will allow you:

1. to find out whether what you fear will happen does in fact happen, and

2. to learn new ways of behaving by acting against the way you feel.

You will also be finding out whether the results of your experiment best fit your existing explanation for your body image problem or an alternative. In body image problems there are two broad alternatives to be tested:

Theory A: I have a problem with the way my hair looks. My solution is to take every possible step to avoid being humiliated and rejected. This has led me to avoid people, hide my hair, and repeatedly check in mirrors.

Theory B: I have a problem with being excessively preoccupied by my hair and am worried about being humiliated and rejected; my ‘solutions’ (driven by theory A) have become my problem and feed my preoccupation.

Try thinking of your own body image problem in terms of two competing theories. Remember that only one theory can be correct – they can’t both be true. In the space below, write under ‘Theory A’ how you have viewed the problem, and how it has led to you using avoidance and safety behaviors. Then write against ‘Theory B’ another way of looking at your experience that would enable to test out your alternative.

Theory A:

Theory B:

If you have a body image problem, you will probably have been following Theory A for many years. However, in order to determine whether Theory B might be the correct explanation for your problems, you will have to act as if it were correct, at least for a time while you collect the evidence.

This may seem rather scary. But think of it like this: if, after, say, three months, you remain unconvinced, you can always go back to Theory A and carry on with your current solutions. Remember the image of the hole and the spade? You might believe that the risk of being humiliated or being rejected through testing out Theory B is too high to risk dropping your spade to see if there is in fact a ladder there. However, if you don’t let go of the spade, then you won’t ever know if there is anything else there to take hold of. If there’s nothing there, you can always go back to your spade; but if you don’t test out the alternative theory, all you will ever have is your spade – and all you will do is dig yourself further into the hole, causing yourself more distress and limiting your life even more.

It may seem to you that digging your way out of a hole works because you are doing something with the tools you have and stopping bad events from happening. It is therefore likely that you will avoid or escape from unpleasant thoughts and situations in the future because such behavior has been ‘reinforced’; it has apparently been successful. However, as we have already pointed out, if you cope by avoiding or escaping from unpleasant thoughts or situations, the technique becomes unworkable for a number of reasons:

1. Your ‘solutions’ of avoidance and escape will make you feel worse and more depressed as you come to realize that they are not going to work and you begin to worry more about problems.

2. Avoidance often prevents you from finding out whether something is true or not. For example, if you never ask a person why he appeared to ignore you, you will never find out if it was because he dislikes you or whether, for instance, he was not wearing his contact lenses or was busy worrying about a problem of his own.

3. Avoidance and escape have unintended effects on the people around you. Your friends and family might stop trusting you and end up taking on your responsibilities. This in turn could create a vicious circle in which you feel incapable of doing certain things.

4. Avoidance stops you from doing what is important to you. For example, you want to be a person to whom your friends and family can turn for support or to be a good parent. When you can’t do these things you will inevitably feel more depressed. You might spend more time focusing on yourself and beating yourself up. Your behavior then has an effect on the people around you. Others may be critical or unsupportive and you will probably become more depressed, in a vicious circle.

While you focus on your negativity, you totally buy into the content of your thoughts as if they were facts. These thoughts are just mental chatter, not objective evidence. In general, the aim should be to ‘understand’ these thoughts, not so that you can question whether they are true or not, but to consider how you react to them.

Many people have their first taste of being really worried about their appearance when they are teenagers. This is not only a time of considerable change in appearance, but also a time when humans are biologically programmed to become more aware of being physically attracted to others and wanting others to be physically attracted to them. For some people with body image problems it seems as if their attitude to their appearance has not been updated since they were much younger. Many still treat their appearance every day as if looking their best is as important as it would be on a special occasion, TV appearance, or first date. Part of recovery is becoming more flexible in the standards you set for your appearance, and on most days prioritizing other aspects of your life.

One way of thinking about the way your actions might be maintaining your problem is to think about the message they send your brain. The more you act as though an aspect of your appearance is something shameful, or has potential for you to be humiliated, the more your brain understands that a flaw (or flaws) in your appearance is an important problem. Because of this, your brain will frequently send you thoughts about your appearance so that you don’t forget to solve the problem. It will also keep your nervous system on ‘red alert’ in situations you have trained it to believe are threatening. It will do this by, for example, over-preparing for the situations, using safety behaviors or avoiding them, or escaping from them. This ‘red alert’ means anxiety, and a tendency to jump to the conclusion that something threatening is happening. This just makes your life more difficult and less enjoyable, as you can’t relax and fully engage in experiences that you would otherwise find rewarding.

Really understanding how your solutions are the problem is a crucial step in overcoming a body image problem. Here are some examples of how coping strategies and ‘safety behaviors’ backfire and in fact fuel a body image problem:

Use the blank table provided in Appendix 2 (page 390) to monitor your safety behaviors and their consequences over a period of time.

You can use what you have written in this table to build up your own ‘vicious flower’, diagram, as described in the next section.

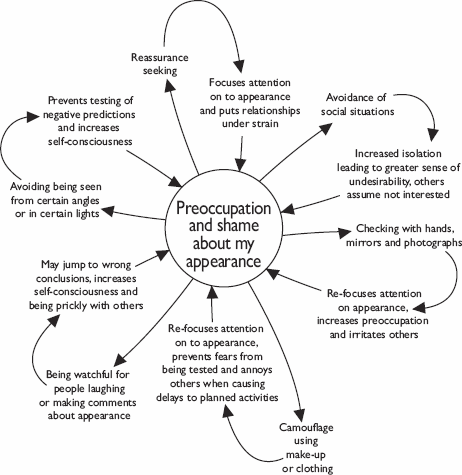

A vicious flower is a model you can use to help think through the effects of your current methods of coping. There are several completed vicious flowers in Chapter 9 and we have provided an example on page 93. This visual illustration of how a body-image problem is being maintained can be very striking. Many people are surprised to see just how much is ‘going on’ in the maintenance of their body image problem.

We have also provided a blank vicious flower on the next page for you to fill in yourself, though it’s sometimes easier to draw your own on a blank sheet of paper so that you can have as many ‘petals’ as you wish. Once you have filled in or drawn your own vicious flower, you can return to it as you progress through the rest of this book. You might add a new petal if you identify a new safety behavior, but we hope that most of your time will be spent pulling the petals off your flower by facing things you have been avoiding, re-training your attention, and dropping unhelpful safety behaviors.