This chapter offers some examples of people with body image problems and gives brief descriptions of how they overcame them. You will notice that some of the examples are of people who have ‘flaws’ in their appearance that most people would agree are observable. Other examples are of people who do not have a ‘flaw’. In other words, most people would agree that their feature is not observable or ‘out of the norm’. However, all the people described in this chapter are distressed about their appearance and this distress is interfering with their lives. Even more importantly, they all managed to reduce their distress and improve their lives by following many of the principles outlined in this book. These examples may not be exactly like your own, so please concentrate on the application of the principles, rather than any slight differences in your own situation. Virtually no one starts a process of recovery from a significant body image problem feeling totally confident that they can recover, so please recognize thoughts like ‘I can see how it could work for someone else but it won’t for me’ as a common by-product of the problem. Just let such thoughts pass through your mind, and give the principles a try.

Eileen is in her mid-twenties. She lives on her own in London and used to work as a supply teacher. Her family live in Cornwall, but she has many good friends whom she used to see regularly. She recently split up with a boyfriend but this was a mutual decision. She used to describe herself as reasonably attractive, happy-go-lucky and a good friend. A year ago she was a passenger in a car that crashed. Although not badly injured, she has some scars on her forehead that have healed well, but are visible to other people. Eileen is devastated about these scars. She has been unable to return to work and increasingly stays on her own in her flat day after day. She will only go out with a baseball hat pulled down low over her face and looks at the ground to avoid catching anyone’s eye. She is frightened that other people will notice her scars and thinks that people have started to back away from her and feel uncertain. Her mood is low and she cannot understand what has happened to the cheerful girl who once confidently stood in front of a class of boisterous children.

First of all, Eileen identified the main problems using the checklist from Exercise 5.1 (page 113) and rated their importance:

1. Feeling very anxious and ashamed about my scars, comparing myself with the way I used to look. Worrying about this most of the day, and having to wear a baseball hat if I have to leave the house. Rating: 10

2. Feeling depressed and tearful about my face. Worrying about other people’s reactions if they see the scars, leading me to spend as much time as I can at home. Rating: 10

3. Worrying about whether I will ever get back to work and have a relationship in the future. Rating: 8

4. Worrying about my treatment and whether it will be possible to remove the scars. Rating: 8

5. Not feeling as if I am ‘me’ any more. Rating: 8

Eileen then kept a record of her activities for the week. From this, it was clear that she spent all her time alone. She spent long periods reading or watching television or thinking about her face. In the morning she spent an hour looking at her scars in the mirror and trying to cover them with make-up, and she returned to check on whether they were visible every one to two hours. Three times a week, she had to go out to get milk and food, but she bought large enough quantities to last for a few days so that she did not need to go out more often. When she went out, she prepared for at least two hours, pulling a baseball cap as low as she could and hurrying back without talking to anyone. She rated her anxiety before going out as 10/10, and coming home again was associated with a huge feeling of relief and a fall in anxiety to 3/10.

To help motivate herself to overcome her problems, Eileen worked through the ‘Exercise 5.3: Understanding your values’ worksheet (see page 120) and identified the directions in life that were important to her. Here are some examples of what she wrote:

• I would like to meet someone and feel that I am the same happy and supportive friend that I used to be, not always talking about my own problems.

• I’d like to be a good sister and see more of my family.

• I’d like to return to work, which I really used to enjoy.

The first step towards helping Eileen change some of her behavior was to encourage her to increase her level of activity and to cut down on her avoidance of leaving the house. To do this, we had to explore the reasons why she was fearful, remove any parts of her behavior that were currently unhelpful (safety behaviors) and put in place some positive strategies.

For Eileen, the most frightening part of going out was the feeling that everyone was staring at her and her scars. This is a very common feeling if there is something about your appearance that is visible to others, and it can often be confirmed by people doing a double-take or staring and asking questions. For this reason, Eileen needed a good response. If someone was staring, she decided that she could:

• Act in a positive way by looking firmly at them and smiling. If someone asked about her scarring she could:

• Respond in a positive way by saying e.g. ‘I was in a car accident. It was several months ago and I’m much better now.’ She could then comment on some aspect of the other person’s appearance, e.g. ‘I like your scarf – do you mind me asking where you got it?’

By responding in such a way, Eileen would demonstrate that there was nothing odd or strange about her.

Eileen also needed to modify her safety behaviors such as wearing the baseball cap. She was invited to write down the way people seemed to respond to her and to see if there was another way of explaining this.

Eileen is very tall. Because she was wearing a cap, she was also wearing jeans and an anorak, rather than her normal skirt and top. Add to this the fact that she was looking at the floor to avoid eye contact, and trying to get in and out of a shop quickly, and her behavior could appear very suspicious. This had not occurred to Eileen but she could readily see that this was a possibility. This helped Eileen to prepare a simple plan for increasing her activity.

First of all she considered her hat. Taking it off completely seemed very frightening. She therefore looked at home for different hats, and chose one without a large brim. She chose a small beret in a soft colour. Because this seemed more feminine, she decided to wear a skirt.

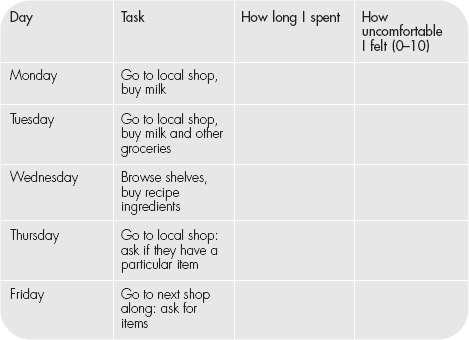

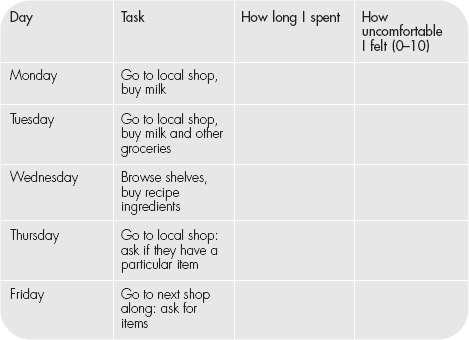

We then worked out a simple exposure program:

Although this table is presented in daily format, Eileen was asked to repeat each task without her safety behaviors, and to focus her attention on her surroundings until her anxiety level dropped to 5 or less, before going on to the next task.

To her surprise, Eileen found this much easier than she had thought, once she got going. One thing that helped immediately was that someone asked her where she had got her hat. She therefore had a very good example of a naturally occurring behavioral experiment, which had disproved the idea that people:

(a) were staring because of her scars (they were looking at her clothes); or

(b) thought she looked freakish or strange (they thought she looked approachable and friendly).

This was the first conversation Eileen had had with anyone for weeks, and it greatly improved her mood and sense of self-esteem. She started to initiate conversations herself, commenting on the weather or the newspaper headlines.

As Eileen began to increase her activity, she found herself worrying less about other people and their response to her. However, she still had lots of worries about her appearance, and felt preoccupied about what she looked like and whether she would ever look as she had before the accident.

We rated Eileen’s ideas about the noticeability of her scars and her preoccupation with them on a scale of 1–10.

The target was to get as close to 0 as possible on both counts. However, if we could reduce the level of worry or preoccupation to 0, then Eileen would be able to achieve all the things she had listed on her valued directions scale, whether or not she still felt the scars were noticeable.

Eileen rated the noticeability of her scars as 8/10, and the amount she worried about them as 10/10.

Eileen decided to keep a record of her thoughts about her appearance and to try to identify her thinking styles (see Chapter 6). She then rated the strength of her belief about the noticeability of her scars and tried to find another way of looking at it.

By focusing on unhelpful thoughts, Eileen could see that she was making her mood lower and triggering more unhelpful beliefs. By questioning whether there was an alternative but equally plausible explanation, she could stop her thoughts spiralling downwards. She now felt able to go and see her family for a short holiday. Whilst there, she tried hard to take part in family activities and, although she found this very anxiety-provoking at first, she was gradually able to relax once she was in the situation. She prepared herself to answer questions about her scarring – but was surprised that no one mentioned it. Eventually, at the end of a long evening at the local pub, someone asked her: ‘I hope you don’t mind me asking, but were you in an accident?’

Eileen actually laughed! ‘Thank goodness! I am supposed be practising answering and no one has asked!’

This proved to be a landmark event for Eileen. She had relaxed enough to discover her old sense of humour, and she went back home feeling much more positive and ready to tackle the next steps in therapy.

(This sometimes happens – a marked success really builds up confidence. But of course the reverse can also happen. You can have a situation that you feel has gone badly. If this happens, don’t jump to negative conclusions. Carefully examine the event, trying not to make value judgements. Look at what happened as feedback. What could you have done differently? What could you have said? How could you have behaved? Decide how you would manage this event if it happened again – make a plan and then move on. Don‘t brood! In this way every event provides feedback for change. There is no such thing as failure so long as you keep on learning!)

Eileen re-rated her scores on noticeability and worry. Not only had her level of worry dropped to 3/10, but her sense of how noticeable her scars were to other people had also fallen.

Eileen kept up her progress with an activity schedule which included going out every day, even if it was just for some shopping, seeing friends and building up her confidence step by step. She kept regular records so that she could talk about her progress during her therapy and to encourage her on days when her mood was lower. Occasionally she had a ‘bad day’, but she focused on the good days, and noticed that things got back to normal much more quickly if she did not brood.

She now began to think about returning to work. This meant planning, reading adverts and completing an application form. Eileen organized this by setting herself manageable goals in a sensible timeframe. Once she had been invited to an interview (this took a number of weeks), she role-played certain interview skills – such as keeping good eye contact, smiling and focusing on other people rather than monitoring her own behavior and responses (see Chapter 6).

At her interview, Eileen took the initiative with regard to her scarring. Rather than having people wonder why she had had so much time off work, she explained about her accident and the scarring. Taking the initiative like this is very helpful in building confidence.

Eileen is now back at work. Of course she wishes the accident had not happened. She still has some visible scarring and people occasionally ask her about it. However, she recognizes that people are curious, that the way she responds means that they very quickly see past the scars, and that her appearance is not the thing that defines her. Her preoccupation and worry has fallen to 1–2. She feels like ‘herself’, recognizes herself when she looks in the mirror, and has plans to start doing some voluntary work for children with special needs.

Fugen was preoccupied with the shape of her nose. She believed that it was misshapen, too big, and did not suit her face. Overall she felt that her nose was very noticeable and abnormal but others could not observe anything that noticeable or abnormal. When she highlighted her nose to a friend who viewed it very closely, the friend could only see a small bump where Fugen thought it was misshapen. However, her friend was viewing her as a whole and did not regard her nose as her identity.

Fugen had had a number of cosmetic procedures earlier in her life, most notably work on her chin, which she said she was happy with, but that it made her nose look worse by contrast. She had approached a number of cosmetic surgeons who did not consider her a good candidate for further surgery. She was spending at least six hours per day preoccupied with her appearance, felt down much of the time, and frequently anxious about her appearance. She worked a few hours from home, having withdrawn from her office, and rarely socialized. She experienced a felt impression of her nose in her mind, which she looked at as an observer. Sometimes this led to doubts as to how exactly she did look and to frequent checking of her nose in mirrors which had to have the right lighting. This often led to further doubts. She avoided bright lights, which cast a shadow. She compared herself to old photographs of how she used to look, and compared her nose to the noses of other women of the same age. Her relationship had broken down, as her partner as was unable to cope with her behavior.

There were two alternative theories to be tested out in therapy:

Theory A (which she had been following for several years) was that the problem was her nose and that this had to be fixed before she could do anything else in life, or she would be humiliated and be alone all her life.

Theory B (which was to be tested during therapy) was that she had an emotional and thinking problem about her nose and that her solutions (by treating it as Theory A) was making her preoccupation and distress with her nose worse.

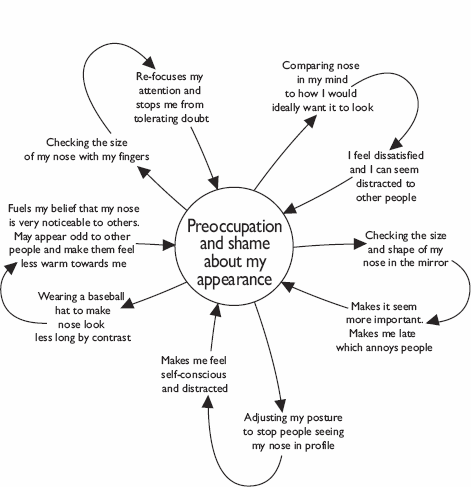

Fugen identified some of her ways of coping with their unintended consequences for her preoccupation and distress, using the vicious flower diagram on page 227.

Her commitment for change was to treat her problem ‘as if’ she had an emotional and thinking problem, rather than a problem with the appearance of her nose (even though she didn’t believe it). After all, if treating it as Theory B for several months didn’t work, then she could always go back to her previous way of treating it as Theory A. She also recognized that there could have been ghosts from the past (such as when she was bullied as a child) that influenced the way she felt about her appearance. Furthermore, she recognized that some of her ways of coping were making her preoccupation worse and that she was on an endless treadmill of further checking. She was very fearful of being humiliated and left alone in the world. However, she also knew that many of her solutions were now the problem. They were causing much of her unhappiness and isolation.

The first step was for Fugen to keep a record of how often she checked her nose both with her fingers and in the mirror, using a ‘tally counter’ she bought via the Internet. This helped her to monitor her checking, made her more aware of just how much checking she was doing, and helped her to steadily reduce and stop the checking.

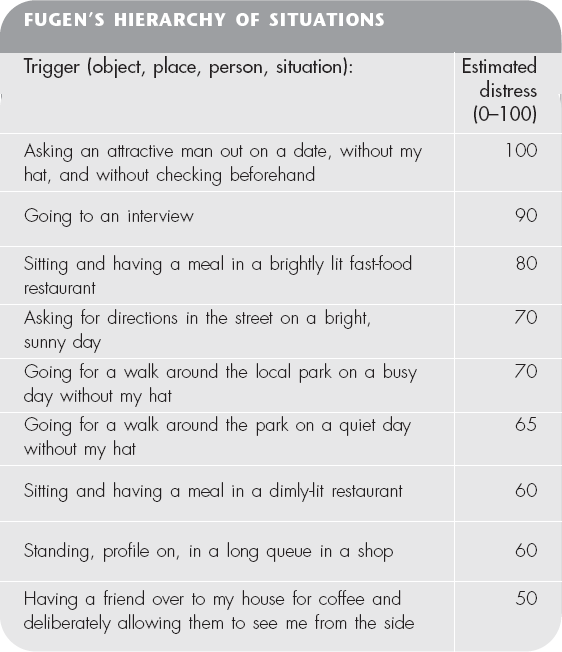

She learnt how to use mirrors in healthy way and to refocus her attention more on what she saw without making any judgement. At the same time, Fugen developed a hierarchy of situations she was anxious about or was avoiding.

Fugen found using a hierarchy helpful in three main ways:

1. It helped her see more clearly that recovery could be a series of gradual steps, rather than taking her usual ‘all or nothing’ view of ‘stop being so silly’ or ‘of course I’m devastated; so would anyone else be’.

2. She used her hierarchy as a guide for areas in which to conduct ‘behavioral experiments’ (see example below).

3. She used her hierarchy as a guide to help her practise approaching situations without her safety behaviors. She could then re-direct her attention into the surroundings, away from her felt impression of how she was coming across. This was particularly difficult and the main strategy to re-focus her attention was ‘task concentration training’ (see Chapter 6). She rediscovered her love of nature, and found it especially helpful in the early stages to practise re-focusing her attention onto trees and plants as she walked. This helped to ‘anchor’ her attention in the outside world and then she found she could more readily move it around to other aspects of her task or environment.

Fugen eventually learnt to stop brooding about her nose. This was a great relief, as the brooding just made her feel worse and more preoccupied. Her mind constantly generated more questions, to which there were no solutions.

After she had made some progress with changing her behavior, Fugen learnt to develop a different relationship with her intrusive thoughts and images about her appearance. She viewed her thoughts and images about her appearance as her internal ‘BDD TV’. She considered that her thoughts could be like a ‘history channel’ (for when she brooded about the past), the ‘BDD propaganda newsflash’ (for when an upsetting image or thoughts would suddenly enter her head), or ‘adverts’ for when her mind was telling her that she ‘needed to know how exactly she looked’ or how she could fix it and had a strong urge to check her appearance. Over time, these ‘BDD TV broadcasts’ became less frequent and distressing. She was able to return to work in her office. She contacted some of her old friends and about six months later developed a new relationship.

Roz, aged 32, was preoccupied with her weight and shape. She was especially concerned with her stomach and the upper part of her thighs. She frequently stood in front of the mirror, changing the angle she looked at herself from, attacking herself in her mind for being ‘fat and disgusting’. She would poke, squeeze, or even hit areas of fat on her body. She did not have a diagnosed eating disorder but would spend a lot of time researching different diets and slimming products on the Internet, and was usually ‘on a diet‘. She avoided foods that she considered extremely ‘unsafe’ such as white bread. And she would usually avoid eating in public. If she deviated from her diet plan she would feel guilty about having ‘let herself down’ and become very angry. She would then very often try and starve herself the next day or try and burn off more calories at the gym. She would tend to either weigh herself excessively, or avoid weighing herself for fear of finding out that she had gained weight. She would frequently compare herself with other people, especially focusing on people who were her ideal size and shape. One way of comparing herself with her ideal size and shape, which often provoked a significant drop in her mood, was to put on clothes that she had worn when she was in her early twenties.

She recognized that her solutions – monitoring her weight and shape and constantly comparing herself with others – were making her very unhappy and had become self-perpetuating. However, change was going to involve real commitment to experiencing some unpleasant thoughts and feelings. A number of her problems had developed after two of her relationships had broken up. Throughout her life, her family had always commented on how pretty she was, and how it was very important to look after herself and to have a happy marriage.

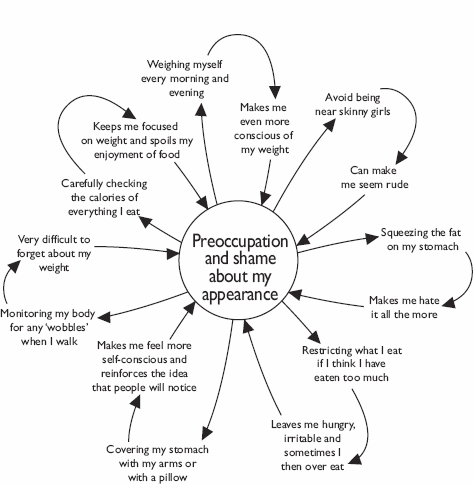

As part of getting to grips with her body image problem, Roz built her own vicious flower, overleaf.

As part of her recovery, Roz resolved to stop buying fashion magazines for herself, and to replace them with novels and magazines on music. She practised using a mirror in a healthier way, as described in Chapter 7. A crucial step in recovery for Roz was what she called ‘positive eating’. This meant that she concentrated on eating regularly, three meals with a mid-morning snack, but with an emphasis on health rather than weight loss. She therefore took great care to eat plenty of fruit, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, lean meat and fish. She also made exercise part of her weekly routine, focusing more on boosting her fitness and stamina than on burning off calories.

Roz identified an early memory of her family sitting watching television when she was a child. She recalled that whenever a celebrity appeared on the screen, her parents and older sister would comment on whether that personality had gained or lost weight. She realized that this had led her to fear gaining weight and being criticized. She took one of those memories and restructured it in her imagination. She imagined her older self walking into the living room and scolding her family, and them apologizing and admitting that it was a bad habit. This helped her to feel more confident in reducing her own self-attacking.

An important symbolic step for Roz was to throw away her ‘twenty-something’ clothes, and update her wardrobe to clothes the right size for her now. She also increased her social life, but initially found it very hard to resist comparing herself with others. She shocked herself by keeping a frequency record of her comparing for a few days. Over the next couple of weeks, she deliberately focused on the sounds, smells, and décor of the places where she met friends, to help keep her attention away from comparing.

Roz practised thinking of her critical thoughts about her appearance as ‘mental traffic’, and considered herself as a pedestrian standing at the side of the road watching the traffic go by. One thought that she found particularly hard to allow to pass was an idea that if she stopped worrying about her weight she would become obese, and feel much worse than she already did. She decided to think of this thought as a particularly unpleasant-looking, dirty and polluting ‘lorry’ driving down her psychological ‘street’ – harder to ignore, but not worthy of her attention. She realized that fears of losing control of her weight were entirely natural, in view of the fact that she had given it so much importance over the years. However, she decided that she would see how her healthy living worked out for at least six months before considering any changes.

Happily, six months later, she was far happier and less consumed by anxiety about her weight, and was even more convinced that it was not worth focusing on. Her social life had improved and she was able to be a better friend. Her friends liked the fact that she was no longer preoccupied with her weight and shape and was fun to be around.

Tom is a student. He enjoys a drink with his mates, particularly when the pub is showing the premier league football games. He describes himself as amiable, friendly and the last person to be aggressive or get into a fight.

Unfortunately, Tom was unlucky. He was in the wrong place at the wrong time when a fight developed. Someone smashed a bottle and caught him across the face. He now has a characteristic glass injury with a scar running from the corner of his mouth across his cheek. He was referred to the plastic surgeons asking for ‘scar removal’. Although the scar will soften and fade over time, it will remain visible.

Tom had a number of problems when he first came for treatment.

He disliked the change in his appearance and was preoccupied with the idea that the injury was ‘unfair’. He kept brooding about the injury. (‘If only I had not gone that night, if only I had left when I planned etc.’)

He felt irritable, his mood was low and he felt jumpy with other people. He also reported that girls looked at him oddly and were inclined to avoid him, whilst other men seemed more aggressive. He started to avoid pubs and stopped spending evenings with his friends.

Like Eileen, Tom was concerned about his appearance. However, his case included some additional problems. The first is related to trauma. Some disfiguring injuries occur as a result of an accident, and this can cause a post-traumatic stress disorder with flashbacks of the incident, avoidance of the scene or reminders of what happened. Mood can be low, with heightened awareness and poor sleep. People may have episodes of ‘dissociation’ or blanking when their mind seems to switch off. But it’s also important to recognize that some of these symptoms are the body’s normal response to trauma. In the first few weeks after an accident it is not at all unusual to experience these effects, and they usually get better without treatment. The best thing to do is get back to as normal a life as possible, talk to friends about what happened and try not to avoid people or situations.

But Tom had the additional problem that his injury seemed to bias people’s response to him. He now looked ‘tough’. He gave this example:

‘As I walked into the pub, there was a girl just ahead of me, so I opened the door for her and stood back. She looked at me as if she was going to smile and then she froze and hurried in, just nodded at me.’

Tom thought that this girl had concluded that he was rough and not the sort of person she should be talking to. He found himself ‘catastrophizing’ and telling himself that he would ‘always’ have this problem and that girls would ‘never’ want to go out with him.

Tom found this situation very difficult to manage because it was so different from his actual character. In order to deal with it, he needed to take charge of the situation before anyone else came to inappropriate conclusions. Instead of looking down and avoiding eye contact, or trying to hide his face, he needed to do the opposite. He needed to look directly at people and smile. He had to get in first, before people made judgements about him, and he needed some ice breakers to show that he had a sense of humour and was not aggressive. He settled on the following:

‘I know I look tough – but I was just in the wrong place at the wrong time.’

‘You should have seen the other chap.’

James Partridge, from the charity Changing Faces (see page 376), has a good way of diffusing the tension when walking into a room, which Tom also found helpful. This is a particularly useful strategy if you are wearing bandages or dressings or have recent scars:

‘Good evening everybody – not looking my best tonight I’m afraid!’

The key is not so much what is said as how it is said – and being ready with an immediate response in a way that gets rid of any tension. Tom had to practise this strategy, rating his response.

As you can see, sometimes the best thing to do was walk away. It is important to recognize, especially when other people have been drinking or are showing off in front of friends, that taking control of the situation can mean removing yourself, even if briefly, before other aggressive behavior develops. This is not a negative avoiding response, but a controlled judgement and a positive way of coping with a potentially dangerous situation.

Tom built up a number of different ways of answering questions and behaving in a way that put other people at their ease. As he increased his social activities and time spent with friends, so the flashbacks and ‘re-experiencing’ of the attack faded, he started to sleep better, and, although he remembered what happened, he no longer felt as though he was constantly reliving it. Like Eileen, he would far rather he did not have the scar. But he no longer searches for a surgical solution, nor does he let it get in the way of doing what he wants to do.

Nicola is six. She was born with a port wine stain or birthmark on her face. The red colour makes the birthmark very visible to other people, and the texture is slightly less even than the other side.

Nicola’s parents were very protective. They did not want her to play rough games with other children at playgroup because they feared ‘another injury’. They also worried about her being bullied by other children and spent a lot of time on the Internet trying to find new forms of laser treatment that might help her. Nicola’s father worried that she might be promiscuous when she was older because this would be ‘the only way she could get a boyfriend’. Her mother thought that it was good that she had an older sister because ‘she would be able to stand up for Nicola and stop other children teasing her’. (It is important not to anticipate problems. It is equally possible that Nicola will be the confident child and stand up for her sister! )

As we discussed in earlier chapters, younger children are very accepting of visible difference. As she goes through school, however, she may encounter more problems, as appearance becomes more important for her social group.

We made the following changes with Nicola: First of all, her parents contacted her school and ensured that everyone there knew what a port wine stain was, how it is treated and that there was no reason to exclude her from any activities. They quickly agreed that they wanted her to be treated just like the other children.

Next we all ‘brainstormed’ what Nicola could call her port wine stain. We wanted something easy to remember that everyone would understand and which she could use to answer questions. We called it her ‘birthmark’.

The idea that one’s appearance is special rather than abnormal is important here. No feature is ever ugly or horrible or nasty, but rather pink, bumpy or different.

Nicola’s parents practised this when other people asked them about her. In doing this, they were illustrating or ‘modelling’ a positive coping response for Nicola, instead of avoiding situations where other people might ask them about her. Her sister, grandparents and teachers all learnt to refer to this as her ‘birthmark’. As she grows older, Nicola will copy them and use the same kind of response when she is on her own.

Many children’s’ stories make a link between ‘beauty and goodness’. This is not a helpful link for a child. There are lots of books that celebrate difference or simply avoid this kind of comparison. The charity Changing Faces (see page 376) has a list, but they are not difficult to find if you browse in a bookshop or on the website of an online book retailer.

Some parents like to meet others who manage similar issues for their children. Again, Changing Faces offers this kind of peer support and contact, which can help parents exchange good ideas. Nicola’s parents met others through the charity and felt supported by being part of a group working towards better acceptance of variation in appearance.

Nicola is still growing up. As she does so, there will be more challenges for her, but because she has the support of a strong family and social network she is likely to cope with them well. Like others with the same condition, she will choose what she wants to do in life and with whom. Her ‘birthmark’ will not limit her opportunities or force her to compromise in relationships or in her career.

Sabine was a 24-year-old single woman who lived with her parents. Her main problem, of several years’ duration, was a preoccupation with her skin. She felt that her cheeks had become saggy and there was fullness of the lower face, causing lines and ageing, and that she had acne scarring. She was preoccupied to a lesser extent with wrinkling and sun-damaged skin. She wanted intense light therapy or cream for ageing and wrinkling skin, and a skin peel. It was on her mind for at least 10 hours a day, and she was checking in mirrors or reflective surfaces about 20 times a day. She avoided having a photo or videos taken, though she would take a photo of herself on her cameraphone, which she used to compare with photos of when she was much younger.

She was constantly comparing her features with others in the media or to people she met, and with old pictures of herself. She tried to hide her face with her hair. She had been significantly depressed for some time and did nothing at home apart from watching TV, and trying to change her appearance in her mind. She felt constantly tired, and often slept during the day and woke early. Her appetite was variable and she had lost a bit of weight. She often believed the future to be hopeless. She was extremely self-conscious and fearful of others quietly laughing at her and humiliating her and avoided social, public situations.

She had no enjoyment of anything and did not plan anything. If she did go out, then her mind was elsewhere, comparing herself with others. She might try to convince her mother about how unattractive she was. She might push her cheeks up to where they used to be, as she used to look. She tended to brood on the past and why she was born this way and how she could change her skin. Overall, she felt that her face was extremely noticeable (e.g. to a stranger passing at a distance in the street), but others could not observe anything abnormal. She had some acne problems when she was about eight to ten years younger, when she was teased about having a ‘pizza face’.

There were two alternative theories to be tested out in therapy.

Theory A (which she had been following for several years) was that the problem was her skin and that this had to be fixed before she could do anything else in life.

Theory B (which was to be tested during therapy) was that she had an emotional problem about her skin and that her solution (by treating it as Theory A) was making her preoccupation and distress with her skin worse.

The first step was to understand that the ‘solutions’ were the problem, and while she continued to treat her skin as the problem, her preoccupation and distress would persist and her life would continue to be severely limited.

She was desperate to change and agreed to test out Theory B (that the real problem was her preoccupation with her appearance and being excessively self-focused). She focused on a felt impression of herself, which had become fused with reality. What she saw in the mirror was therefore what she felt. She then believed what her mind was telling her about being ugly as a witch.

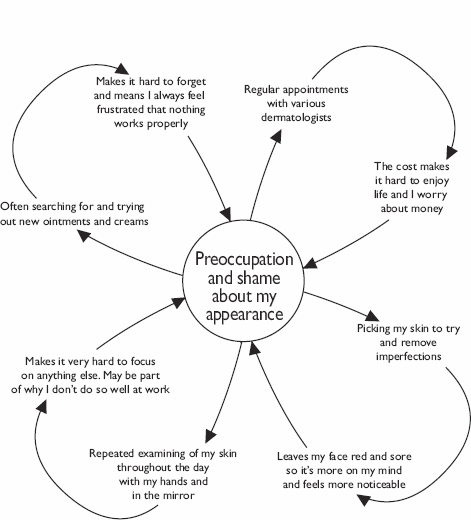

She spent some time developing a good understanding of what was keeping the problem going and identified a number of ways of coping that maintained her preoccupation. She put all this in her vicious flower diagram opposite.

She recognized that, in order to test the theory that the problem was her solutions, each of these petals would have to be pulled off. Logically, she thought, if her situation improved by treating her problem ‘as if’ it were a preoccupation problem, she would learn more about what the true nature of her problem was. However, one strategy she found particularly difficult was checking her appearance using either the mirror or her mobile phone. She decided to conduct an experiment to help make the link between checking and her preoccupation clearer. She recorded the number of hours she was preoccupied with her appearance, and how much distress it caused her on a ‘normal’ checking day. Then the next day she increased her checking by at least 50 per cent. She had thought that she might need to repeat this again to really help herself ‘get the message’ but in fact the middle of the afternoon on day two she was so anxious and disturbed about her appearance that she resolved to try as hard as she could to resist checking for the next few days to see how that affected her. Happily this was a very significant step on her road to recovery.

Sabine defined her problems as follows:

1. Feeling anxious and ashamed about the

condition of the skin on my face. Rating: 10

2. Feeling down and as if my life is over. Rating: 7

Sabine also completed the Exercise 5.3 ‘Understanding your values’ worksheet (see page120) and became clearer in her mind that she no longer wanted her appearance to stand for her life. She was particularly inspired to follow her valued directions in the area of contributing to her community through working with children, and in the area of socializing with friends.

Having realized just how much of her attention had become trained onto her appearance, Sabine consistently practised switching her attention away from what her mind was telling her towards the outside world, using ‘task concentration training’ (described in Chapter 6). To make her attention more flexible, she practised ‘attention training’ in the dining room most days (also described in Chapter 6).

To help lift her low mood, Sabine drew up an ‘activity schedule’ to restore some routine to her life, and become more productive. She also started to spot when she was engaging in brooding and thinking about the past, and practised bringing her attention back into the outside world in the ‘here-and-now’. She viewed much of her activity scheduling as taking care of her life and herself, and ignoring the negative messages her depressed brain was sending her.

Sabine developed a hierarchy of situations she was anxious about and/or avoiding, and conducted a number of behavioral experiments and exposure to such situations whilst gradually dropping her safety behaviors. One of her experiments is shown below:

As part of her desire to keep her body image problem at bay in the long term, Sabine used imagery re-scripting on experiences of when she had been teased and bullied (see Chapter 8 for more on this). She was moved to tears when she imagined her younger self being bullied, and became far more sympathetic towards herself about her worries. She re-framed her body image problem as being like a bully itself, and resolved not to let it push her around into self-focus, avoidance, camouflage or checking. She decided that her negative, threatening, and critical thoughts about her appearance were like a bully’s threats, and she became determined to do what she wanted to do, in spite of the threats. Gradually, she introduced more of what was important in her life. She started to do some voluntary work and new skills so that eventually she could return to work. She caught up with old friends and developed a new relationship after about six months.