This chapter summarizes what is known about the ‘causes’ of body image problems and what makes a person vulnerable to experiencing one. Although it can be important and useful to have some understanding of how you have come to develop a problem, we do not want to encourage you to look endlessly for reasons or causes. When you fall down a hole, you don’t need to know the exact route by which you arrived at the bottom in order to climb out again. Usually there are fairly obvious triggers for body image problems (for example, being teased during adolescence) or vulnerability (for example, being abused as a child). If there is a family history of a mental disorder such as depression or anxiety, genetic inheritance could also be a factor.

When considering possible causes for your symptoms of body image problem, it is usually helpful to think of three groups of factors, those that:

(a) have made you vulnerable to developing symptoms (for example, childhood abuse, trauma, genetic inheritance and unknown factors)

(b) have triggered your symptoms (such as experiencing acne or being disfigured, or living or working in an environment that places exceptional pressure to ‘look’ a certain way)

(c) have helped maintain your symptoms (for example, the way you react, with particular patterns of thinking and acting).

We will discuss the third group – that is, the patterns that maintain your body image problem – in Chapter 4. It is not only within your ability to change them but doing so is the cornerstone of self-help and CBT. In this chapter, we will examine the first two factors.

As we outlined in the previous chapter, there are many different types of body image problems, and no one can be sure exactly what causes them. What we can safely say is that a body image problem is usually the result of a mixture of psychological and biological factors and life experiences since birth. In some cases long-term parental neglect, and a deep sense of being unloved from childhood, may be important factors. Likewise, a person might be teased by their peers over a long period, or a trauma such as a car crash occurs and the person is left with a disfigurement.

Bullying is not uncommon in schools, particularly during adolescence. Bullies tend to pick on the thing that singles someone out or makes them different from their peer group. Unfortunately, appearance is the thing that is most apparent to others. Many people who have body image problems can recall being picked on in a way that made them feel vulnerable and alone.

Bullying also occurs in relationships, and this can be more subtle. Someone who knows another well tends to know about their insecurities, and may pick on things that they know to be the most hurtful. Unfortunately, this can sometimes be taken as confirming evidence – for example, that the person is fat, or ugly, or has a big nose – when in fact they look perfectly normal.

Bullying does not have to be sustained, or a hurtful remark be made intentionally. One very thoughtless comment can haunt someone for years – a ghost from the past – and sustain a body image problem many years later. Often, when challenged, the person who said it will have had no idea of the lasting preoccupation that this comment has triggered, and will be amazed at the upset caused by something that to them seemed inconsequential.

When you consider possible causes of body image problems, it’s important to remember that life experiences all interact with each other. Imagine that the cause of a body image problem is like a cocktail in a glass. The ingredients of the cocktail will be different for each individual and they will also mix and interact in different ways.

Vulnerability to a body image problem could be due to three types of factors, which may overlap:

• physical conditions, including medical, biological and genetic causes

• personality or psychological traits, and

• life experiences

A mental health problem can sometimes run in families. For instance, if you have a close relative who has had BDD, depression, an eating disorder or obsessive compulsive disorder, you could be at increased risk of experiencing a body image problem at some time in your life. However, having a genetic factor does not mean that you will inevitably develop a body image problem. Similarly, it is possible to develop a body image problem without any evidence of genetic risk, so there is no point in worrying that you may be at greater risk than other people.

Certain aspects of your personality can make you more vulnerable to developing a body image problem. For example, you might be a perfectionist or excessively shy and reserved. Such traits, in combination with one or more triggers, can make you more vulnerable to developing a body image problem.

People with body image problems might also be more aesthetically sensitive than the average person. According to a small study that compared people with BDD with people suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, depression or obsessive compulsive disorder, people with BDD were much more likely than the other three groups to have had an education, training or occupation in art and design. At present, it is unclear whether being more aesthetically sensitive makes you more vulnerable to developing BDD or is a consequence of developing BDD.

Other studies suggest that healthy people might be slightly positively biased (or ‘wearing rose-tinted glasses’) when it comes to rating their own attractiveness, compared with how others rate them. This tendency can be beneficial, as such individuals are more likely to have happy relationships and to be working successfully and doing the things in life that are important to them. In contrast, people with a body image problem seem to have lost their ‘rose-tinted glasses’ and have no positive bias when rating their own attractiveness. People with body image problems can appear to have problems with their perception – for example, in perceiving their body size to be larger than it really is in anorexia – but the problem lies more in their emotional reaction to their appearance, the degree of importance they attach to appearance and the way they judge themselves. We shall discuss these psychological factors in Chapter 4.

Life experiences that may make you vulnerable during childhood or adolescence include emotional neglect, rejection, bullying or sexual abuse, which can all lead to a sense of being worthless or unloved. Traumatic experiences, such as accidents resulting in scars or a skin condition such as acne or eczema, can lead to a lot of attention being focused on appearance. For others, the importance of appearance might be positively linked with success during childhood (e.g. comments such as ‘You were wonderful on stage and you looked so good,’ rather than ‘Your performance was excellent’). Alternatively, a particular body part, or a person’s height or weight, might have been highlighted. Early dating success, and other adolescent experiences where the importance of appearance is at a premium, could also play their part.

Most cultures value appearance. Less attractive leading female television or movie stars are in the minority, and several recent TV reality shows have focused on unattractive women who undergo a radical transformation. In addition, we are bombarded by advertisements telling us that physical attractiveness is necessary for success and that we need cosmetic products and surgery to achieve the appearance we want.

Some cultures seem to put a greater emphasis on the importance of looking attractive. For example, cosmetic surgery in Brazil is very common and out of proportion to the wealth of the country. Equally, in western culture gay men seem to feel that they are under increased pressure to look attractive. Other cultural aspects can be relevant in individual cases. For example, a Puerto Rican woman was intensely distressed by a small facial scar that she received in an accident. This was because, in her community, a scar was inflicted as a punishment for adultery.

Apart from cultural factors, immediate peers and family can have a big influence on the importance of appearance to an individual. For example, research has shown links between a daughter’s recollection of her mother’s earlier attitudes to her own body and the daughter’s own current body image. In addition, having a more attractive sibling may encourage a person to rate their own attractiveness unfavourably.

There are many medical conditions that can alter someone’s appearance, such as polycystic ovary syndrome (which leads to weight gain and excessive hair growth), or an under-active thyroid (which might lead to weight gain, forgetfulness, excessive tiredness, a hoarse voice, slow speech, constipation, feeling cold, hair loss, dry rough skin, irregular periods and infertility as well as symptoms of anxiety and depression). There are also many medical treatments that alter personal appearance (for example, there may be facial wasting after anti-retroviral treatments for HIV, or ‘moon face’, altered body shape and skin thinning after use of steroids).

However, a change in appearance does not inevitably lead to a body image problem. Body image problems are more closely related to how much you believe that others will notice your abnormality, the importance you attach to appearance and the unfavourable comparisons you might draw with a former self.

There are a very few medical conditions that might aggravate or mimic BDD. If your medical history suggests a possible physical cause or if you are not getting better with conventional treatments, such causes should perhaps be investigated despite their relative rarity. For example, a thyroid problem could be linked to BDD.

Some theories are based on biological explanations – for example, that a ‘defect’ in brain chemicals or an ‘illness in the brain’ causes BDD. This sort of explanation may reduce the stigma and blame attached to individuals with BDD by ignorant people who think that they should just ‘pull themselves together’. However, biological factors alone do not fully explain the symptoms of BDD, and the social stigma will not necessarily be reduced by this approach. Furthermore, such explanations don’t place enough emphasis on the social context and psychological factors involved in BDD and therefore underplay the importance of psychological treatments for the condition.

Trying to unravel the biology of BDD or depression is a complex business, and statements that BDD (or any other mental disorder) is caused by an imbalance of serotonin or other chemicals in the brain are simplistic nonsense. Unfortunately, some pharmaceutical companies have placed far too much emphasis on this aspect and have thus spread misinformation.

In general, any biological changes observed in the brain of a person with BDD can be reversed by psychological treatment or physical therapy. Permanent structural damage in someone who recovers from BDD is unlikely, and the use of medication does not tell us anything about the cause of BDD.

A body image problem usually occurs as an understandable response to specific events and in a particular context. Many of the triggers in a body image problem are long-term difficulties that may drain someone emotionally and psychologically over time. The most common triggers for a body image problem are:

• being teased or bullied about being different, for example your height, being chubby or your legs being thin

• being aware of a change in your appearance such as being found attractive and then developing acne or a skin condition

• being involved in an accident and developing a scar.

Sometimes a body image problem such as BDD seems to occur out of the blue, without any identifiable trigger or social factors. In this case there could be more biological factors at work.

Even when there are strong biological influences in your body image problem, the way you react to the problem still influences the severity of the symptoms. For example, if there is a significant genetic component you may be ashamed both of having a family history of mental disorder and of your body image disorder. The way you respond (for example, by being withdrawn and inactive and brooding on how awful you are for having a body image problem) could determine the severity of your symptoms and the speed of your recovery.

Even if a health professional recommends that you take medication for BDD or another problem such as depression or an eating disorder, there is nothing to stop you easing your symptoms by also using the approaches described in this book. This will involve developing a more compassionate and caring view of yourself, acting as if you truly believe you have nothing to be ashamed of in your appearance, and doing more of the activities you are avoiding.

One way of thinking about your mind is that it consists of a large number of modules, each designed to do certain jobs. For example, there is a module for fear, another for memory, and so on. In some mental disorders, there may be damage to a particular module. In conditions like dementia, for instance, there may be damage to the module for memory. In other disorders, certain modules are trying too hard or shutting down because there is an excessive load on the system.

A body image problem can be regarded as a failure in the brain’s system because it is overloaded and is trying too hard to solve a problem with the way you feel about your appearance. In such a case, the mind’s solutions become a problem. The system is overloaded because of the way you try to escape from unpleasant thoughts, images and feelings, or control your feelings by brooding about the past or worrying about all the bad things that could occur. The mind normally tries to fix unpleasant thoughts and feelings by escaping from them or finding ways of controlling them, and it copes the best way it can. This process can be seen in abnormal brain scans and serotonin activity. In our opinion, these biological changes do not cause the body image problem but are more of a reaction to it – the consequence of the mind desperately trying to escape from and control the way you feel.

This is not to say that the biology is not important, as it does become part of the process. For example, when you are stressed, your cortisol goes up, and over time this will reduce your serotonin levels. As your serotonin goes down, you may feel more tired. This will affect your sleep and the next day this will affect the way you cope with everyday events. Your body and your mind work together and one has an effect on the other. However, you can switch off these biological responses by acting against the way you feel about your appearance, and this will lead to better feelings. We shall develop this psychological understanding of body image problems in Chapter 4.

Each of us is a product of our genes and what we have learnt since we were born. The way we think and act is shaped by our experiences. Throughout this book, we emphasize the importance of the context. For instance, lots of ‘bad’ events may occur, especially in childhood, from emotional and physical abuse and neglect to lack of boundaries or learning about the importance of appearance. If we experienced unpleasant events when we were younger, we tend to avoid anything similar and anything that reminds us of them when we are older. If you were teased or not loved during childhood or adolescence, it would not be surprising if you grew up believing yourself to be ugly.

Much of our development occurs without our being aware of it, and we are exposed to literally millions of moments of learning. It is utterly impossible to unravel or organize them into a causal order. This is why therapies that promise to ‘get to the bottom of it all’ and discover the cause of your body image problem in childhood are often unhelpful. In fact, such therapies may sometimes make things worse by encouraging you to brood on the past.

If you do have very low self-esteem and are very self-critical, you may justify your actions as a way of protecting yourself (or even punishing yourself before others can punish you) and making sure you are not hurt or not criticized by others. In this book, we will be examining if this really prevents bad things from happening or whether it makes it more difficult to achieve what you really want to achieve in life.

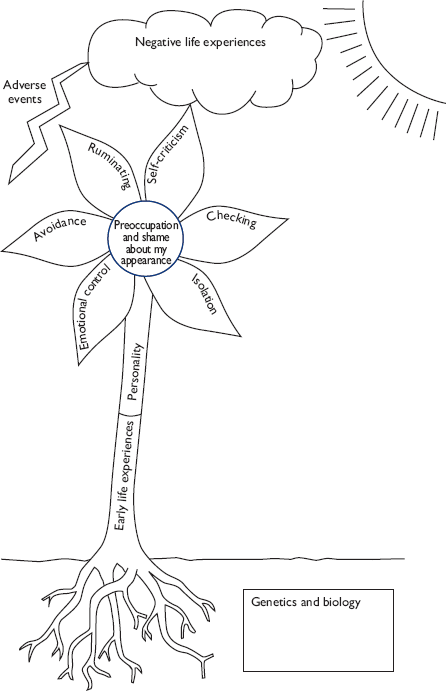

In the following drawing, we use the metaphor of a flower to identify areas of vulnerability to, and triggers for, body image problems. You will see that the roots represent the biological causes of vulnerability, such as your genes. Your psychological make-up and life experiences (the other two factors that lead to vulnerability) form the stem and leaves. Triggers (bad things that have happened recently and have triggered the body image problem) are shown by clouds and lightning – as life is never going to be all sunlight and warmth.

Now try this exercise for yourself on a blank flower with its stem and roots (see page 54). You can consider the risk factors under the following headings.

Are there any possible genetic or biological risks? For example, do you have a family history of mental disorder? Did you have a persistent skin problem like eczema or acne? Were you born with a visible difference in your appearance? Have you regularly taken an illegal substance?

Are there aspects of your personality that make you vulnerable? For example, have you always had low self-esteem, been a perfectionist, had an anxious temperament, or been someone with a particular appreciation of art and beauty?

Did you have any bad experiences like bullying or neglect when you were younger that might have made you more vulnerable and less able to cope well with stress now? Did your parents or culture emphasize the importance of appearance? Does success in your work depend on what you look like (e.g. modelling or acting)?

Have there been social or personal problems in your life, like the break-up of a relationship or an accident such as a car crash? Have been there any major changes in your role in life?

By writing down the factors that might have made you vulnerable to your body image problem and inserting labels on the roots, leaves and thunderstorms in your picture, you are building an understanding view of the ‘history’ behind your body image problem. This will help you to be less critical of yourself for having a body image problem, and will help put your problem in context.

Don’t worry if you can’t identify particular factors that make you vulnerable to developing a body image problem. It can sometimes be difficult to be certain of the causes, especially if a problem developed from a young age. As yet, we do not fully understand all the causes of body image problems. Constantly searching for a reason might seem like a good idea if you think that you need to find the reason before you can fix the problem. This approach usually works with physical problems: if you have a chest pain caused by a lack of oxygen to your heart because of a blockage in an artery, then a doctor can do the right investigations to find the blockage and bypass the blocked artery with a graft. However, this approach does not work if you have an emotional problem, because – the more you try to stop feeling bad by searching for an elusive ‘root cause’, the more you focus on how bad you are feeling. As a result, you are likely to end up making yourself feel worse.

Inevitably, you will read or be told different things by different therapists or doctors. The more opinions you seek and the more books and websites you read, the more your doubts will increase. Some experts may emphasize the role of brain chemicals, while others may empathize with your childhood experiences. Change involves learning to tolerate uncertainty and accepting that you will never know the ‘exact’ combination of factors that might be relevant for you. Some of the ‘causes’ are probably in the unknown category and, even if you knew the exact order of events, you probably can’t do anything effective about them. Just say no to any therapy that offers to find the route you took into the hole. Instead, insist on a proven psychological treatment for a body image problem that helps you get out of the hole!