6 Matchmaking

There’s a rise in interest in designs that have a positive social impact. A number of projects are focused on “designing for” a community of people that’s presumed to be disadvantaged. New technologies for students in developing countries. Design contests to create solutions for elderly people or people with disabilities.

While these are often well-intentioned, there are some potential pitfalls to designing for people with this superhero-victim or benefactor-beneficiary mindset. It can lead to specialized solutions that cater to stereotypes about people.

Us and Them

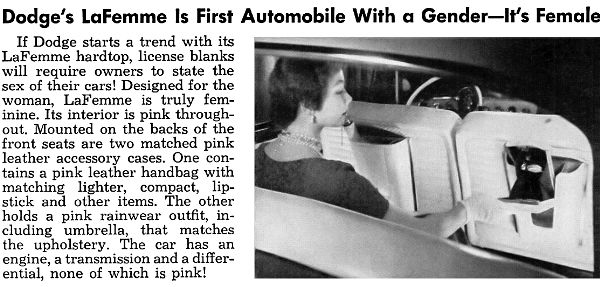

To illustrate the problem let’s consider the Dodge LaFemme, a car designed specifically for women, brought to market in 1955 and canceled in 1956. The car was pink, inside and out, decorated with small roses. It featured a fully equipped matching purse that fit into the back of the passenger side headrest. It was marketed with the headline “By Special Appointment to Her Majesty . . . the American Woman.”

A review of Dodge’s LaFemme, published by Popular Mechanics in July 1955.

While it’s somewhat easy to dismiss this as an artifact of a bygone era of male chauvinism, let’s also consider the failed launch of Bic for Her in 2012. This was a line of pens designed specifically for women that were thinner than standard pens and available in pastel shades of pink, purple, and turquoise. It was marketed on Amazon as having an “elegant design—just for her!” and a “thin barrel to fit a woman’s hand.”

Thin barrel or not, the pens are now a hallmark example of how not to design and market your product to women, thanks to writer Margaret Hartman who sparked thousands of people to write entertainingly sarcastic reviews on Amazon.com. The product was quickly removed from market.

In a more serious example, the automotive industry conducts safety testing with models of humans, also known as crash test dummies. For decades these models were made to match the average male body type, though it was widely known that women were significantly more likely to be injured in a car accident.

In 2011 the federal government started an initiative to reduce demographic disparities in public health. Car accidents ranked high on the list of public health risks. Passenger-side safety ratings plummeted as cars were tested with a petite female crash test model that was 4 feet 11 inches tall and 108 pounds.1 That year, studies revealed that a female driver, wearing a seatbelt, faced a 47% higher risk of death or serious injury than a male driver.2

Decades of design choices where made based on average male-sized testing standards. Engineers and designers were trained to optimize to these standards. It wasn’t that the cars were suddenly less safe. They had always been less safe. It just hadn’t been recognized as a problem.

This wasn’t a sex-specific disparity. The average male crash test model is 5 feet 9 inches tall and 172 pounds. Once the industry started using a range of body types in their safety testing, there was an improvement for any person whose body didn’t match the design of the male crash test model, across all genders, sizes, and ages.

We can see from these examples how the deep perceptions people have about one another can be manifested in the design of products and environments. Many features of the most famous American cityscapes were constructed with a specific intention to exclude groups of people from social and economic opportunities. Even after those structures are demolished, retrofitted, or long gone, it’s striking how an us-and-them mindset continues to manifest in the designs around us.

Some designs are intentionally created to exclude groups of people. It isn’t always a matter of mindlessness or forgetting to consider a community, but a targeted act of discrimination motivated by racism, ableism, sexism, classism, or related motivations to exploit power. Rectifying these forms of exclusionary design requires a shift in culture and a laser-sharp focus on changing the root of that exclusion.

An unspoken hierarchy also appears when attempting to design solutions for groups that are perceived as needing help. Without an authentic and meaningful understanding of a person’s life experiences, stereotypes can prevail. All too often, designers and architects perceive the recipients of their solutions as “other people.” This mindset distances the designers from people they perceive as disadvantaged beneficiaries of their design.

The problem is separation. It’s rooted in the ways we categorize human diversity. The most common ways that we group people by diversity are single dimensions like ability, gender, race, ethnicity, income, sexual orientation, and age. Even if we know that people are more complex than a single dimension, businesses regularly try to solve problems based on these monolithic groupings.

Many of these demographic categories have more to do with business or social power structures than with how people actually interact with the world. It’s unclear why a software designer needs to know the gender identity of a customer, or whether or not they have two X chromosomes, in order to create a better way to organize photos. Unchecked assumptions about any group of people, especially when treated as a monolithic group, might misdirect us toward ineffective, even offensive, solutions.

How we categorize people shapes how we make. With a growing interest in participatory design methods across many professional fields, how is that participation to be facilitated? What kinds of questions do you lead with? Do you meet people in their homes, or require them to visit your office? What tools do you ask them to use when providing input to the design, and are they comfortable using them? Meaningful inclusion is much more than hosting listening tours, focus groups, or interviewing people on the street.

One way to start is by building an extended community of “exclusion experts” who contribute to your design process. These are people who experience the greatest mismatch when using your solution, or who might be the most negatively affected. Develop meaningful relationships with communities that contribute to a design. Designing with, not for, excluded communities is how we put the inclusive in inclusive design.

Disruptive Change

In the pursuit of innovation, it’s common for teams to focus solely on the functional elements of design. It’s equally important to understand the emotional considerations of a design, in particular the familiarity people have already developed with an existing solution. What are their patterns of using a solution? What makes these patterns important to their lives?

Consider a person who takes a carefully planned path through a city to make it on time to work every day. Or the ways they organize important files in their personal computing devices. Something as simple as changing the name of a feature in a software application or a street name in a city could be disorienting for them.

This exclusion habit is often motivated by economic factors. Change for the sake of newness. Growth for the sake of progress. Delight for the sake of differentiation. Fixing perceived disorder into order. Along the way, design changes can disrupt human patterns and relationships. Especially when the problem solver, whether an architect, designer, engineer, or business leader, presumes that their own professional expertise supersedes the life expertise of people who are affected by those changes.

The same thing happens in digital spaces when we change products that people are familiar with. Each time we change a design, by adding new features or moving things around, we require people to learn something new. They have to form new relationships and new patterns of behavior.

The problem is, everyone adapts in their own ways. Not everyone solves problems or learns through the same approaches. But when designers make changes to a product or space, their ability biases can lead the way.

As an example, while at Microsoft, I received a phone call one evening from a product leader who was concerned that there were far fewer women using their product than they expected. He was also concerned by the early solutions that teams were proposing to address this issue.

We took a closer look at the patterns of behavior that were happening in the product. We studied the research of Oregon State University professor Margaret Burnett, who has spent over a decade studying the relationship between gender and software. In her GenderMag project, Dr. Burnett identified a set of facets that consistently lead to differences in how software is used by persons identifying as women or men.3

One facet, in particular, stood out to us: how people prefer to learn. Dr. Burnett also refers to this as a person’s willingness to tinker with new software. She describes a spectrum that spans between two approaches to learning new technology. On one end is a preference to learn through a guided approach, or with the assistance of a human being. On the other end is a high willingness to explore a software interface through trial and error.

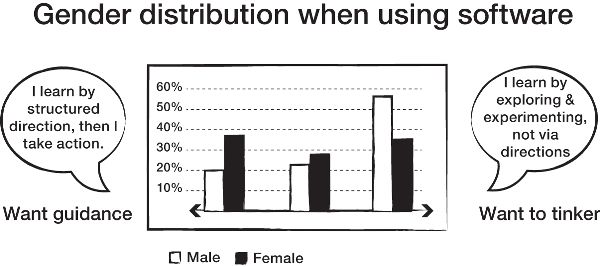

The research showed that people who identified as women distributed relatively evenly across this spectrum. There was a wide range of learning styles that different women used when learning new software. People who identified as men, however, clustered heavily toward the end of the spectrum for tinkering and troubleshooting solutions.

A representation of gender distribution as people discover and learn to use software. (Based on data collected by the GenderMag project in 2016. For more information visit www.mismatch.design.)

This insight helped us reframe the problem. Was it possible that our product favored a particular learning style? We restructured our research to recruit people by learning style, and interviewed people from multiple genders, including transgender participants.4

We found that people who preferred a guided learning approach, regardless of gender, felt alienated and confused by recent changes we made in the product. They were concerned that important programs had disappeared. Or they couldn’t figure out how to complete tasks they’d known how to do for years, because the interface had changed.

It turned out that when we updated our product, we required people to learn something new. But we did so in a way that reflected our own internal learning styles. This differed from how many of our customers learned. After all, what percentage of the general population is trained to think like engineers? Design decisions were made with the assumption that people would just hunt around and try things until they found what they needed, reflecting our team’s own learning styles and disproportionately benefitting men.

A Sense of Belonging

This ties back to Brown’s insight about her own ways of learning. It isn’t about needing help. It’s about making a personal connection. Guided learning is one way for people to understand why a solution works the way it does, which helps them feel more confident in their abilities to utilize a solution.

We applied inclusive design and sought out customers, across genders, who preferred a more guided learning approach. The process was similar to seeking out people who have ability biases that complement the dominant ability biases of our teams.

These conversations helped us understand elegant ways to connect customers to existing product guidance, and present it in ways that were relevant to the task they were trying to complete. Even more importantly, the engineering and design teams were united around the idea that we could tangibly include customers who could fill the gaps in our own knowledge. We isolated what we didn’t know and sought out this expertise from customers who felt alienated. Then we asked thoughtful questions, and let their answers change our design process.

Disruptive changes can especially be an issue for people with disabilities who might depend on a particular technology to complete essential tasks in their lives. If a software program or website is updated, but the right steps aren’t taken to ensure the updates are compatible with assistive tools like screen readers, the resulting changes can literally prohibit someone from doing their job. Or prevent them from using a form of transit that they need to get to work on time. A change to a payment system can impact a person’s livelihood.

These learning biases can be further reinforced by feedback from customers. Many companies depend on their most engaged users, people who love products as much as the people who make them, to spend time providing feedback.

How feedback is collected often reflects the preferences of the team that builds the product. As you might imagine, if you only take online feedback, or only provide customer support in English, the only people you’ll hear from are people who match this profile. This has a profound impact on which feedback makes its way to the design team.

These feedback channels can also be a signal to customers that they either do or don’t belong with the product. With technology, many customers have a tendency to blame themselves for not being able to figure out the changes on their own. Common indicators are customers who say “I feel like technology is moving so much faster than I am” or “I’m probably not smart enough to figure this out.” In essence, they feel excluded. The impact on people can be deeply emotional.

Shifting that sense of exclusion requires careful attention to who’s missing from a solution and from feedback channels. Whose voices are the loudest and whose are missing? Seek out who’s missing and learn about their existing patterns of behavior. Design solutions that bring them successfully through your changes. Provifde a diversity of ways to get guidance on what’s new and help customers get reoriented with a product they’ve known and used for years.

We can also shift the sense of belonging by opening up the ways that people can contribute to the design process itself. Contributing to the design of a product or environment, even in the smallest ways, increases the emotional connection between a person and that solution.

The push to accelerate growth and change, for cities or software, is often necessary. But how it is implemented is vitally important.

People create emotional connections to a design that make a place, or a product, feel like their own. Introducing change isn’t just about breaking apart concrete or bits of code. It’s breaking apart human relationships. The result may be that people will leave and never return.

Making a change without disrupting a sense of belonging can be difficult. It’s a challenge because it’s an emotional choice, not just a rational one. Those emotional considerations are best described by people who are the most excluded from your solution. Or those who stand to lose the most during times of change, including kids who will interact with the next generation of designs. Their contributions will be one of your greatest resources in designing where to go next.

My House, My Rules

Leaders can be powerful advocates for creating inclusion. They set the house rules. Although leadership can come from anyone in a team, there is a unique responsibility for people at the most senior levels of an organization. They must be willing to do the personal work of understanding inclusive design. Certainly there are functional investments that are important, but a senior leader can make or break a culture of inclusion.

When someone in a leadership position declares they are committed to inclusion, some people will be inspired to follow. Others will be skeptical after years of knowing the opposite to be true. And absolutely everyone will be waiting for what happens next.

People are often caught off guard after they declare a commitment to inclusion. The first thing they need to contend with is everything that isn’t inclusive. It will show up and make itself known. How a leader listens to, learns from, and invests in shifting these exclusions will be the greatest indicator of their true intentions. Here are four considerations for leaders who want to improve the inclusion of their team.

- ■ Make promises that you can keep. Acknowledge the current state of inclusion in your organization and address fundamental issues of access before moving on to other areas of inclusion. Greater damage to inclusion comes from declaring it a promise while having no plan for how to implement the change. Or building new innovations on top of systems that lack basic accessibility. A broken promise is more detrimental than making no promise in the first place.

- ■ Set an expectation that inclusion is a long game. Balance the cultural history that led us to where we are today with the reasons why inclusion matters to the future of an organization. Have measured plans for how to address entrenched exclusion habits. These have to account for the tradeoffs in resources that need to be made in order to build inclusive solutions. Specific people need to be accountable for completing the work. The work is hard and the road is long. But, as progress begins to happen, inclusion can be one of the strongest ways to mobilize people around a shared purpose. The work is meaningful, not just because it benefits overlooked communities, but because it can drive new ideas for growth with untapped ingenuity and fresh thinking.

- ■ Create a system of incentives and rewards that will motivate people to make inclusive designs. If the incentive structure for an engineer, designer, or marketer specifically calls out rewards for making inclusion a priority at the beginning of the design process, it demonstrates that an organization is truly committed to inclusion. If investments in inclusion, like accessibility, are treated as an added tax, paying that tax will always be deferred in favor of other business priorities. What we measure shows what we value.

- ■ Bring people along in the process. Create a diversity of ways for people to contribute to changing your perspective as a leader. Apply the power of your leadership position to uplifting the excluded communities that are affected by your choices.

It isn’t organic. It doesn’t happen purely through goodwill. It takes intention, planning, and stamina.

Connecting People

Inclusive solutions connect people, whether they’re in a neighborhood or somewhere on the Internet. The solutions that we build can be economic catalysts for excluded communities. Cities and technologies can bridge people to better opportunities through access to work, education, and social resources.

But how we go about making those solutions sets the stage for who benefits from the opportunities. This is what distinguishes inclusive growth from growth that only benefits a few.

Design influences how people view themselves and their community. The outcomes of design carry the imprints of the professionals who crafted them. They are scratched and scored by the remnants of their creators’ thought processes and assumptions. Even after the architect or designer is long gone, their mark endures. The generations of people who live with those designs every day can tell you the exact ways in which that design was a success and a failure.

In times of growth and revival, how we go about creating our solutions can be the difference between perpetuating or transforming the cycle of exclusion. Moments of change are the ideal time to focus on inclusion. The key to success is matching great design challenges with great guidance from exclusion experts.

■ ■ ■

Takeaways: How Exclusion Experts Resolve Mismatches

Exclusion habits

- ■ A “for others” or “superhero” mindset, where pity and stereotypes influence design decisions without any meaningful contribution from excluded communities.

- ■ A top-down approach to making decisions. Presuming that professional expertise supersedes life experience.

- ■ Disregarding existing patterns of familiarity in pursuit of growth. Change for the sake of change.

How to shift toward inclusion

- ■ Identify exclusion experts. These are people who stand to lose the most or face the greatest mismatches with any changes you make to a solution.

- ■ Design with, not for. Facilitate meaningful ways for exclusion experts to contribute to your design process.

- ■ Understand the emotional value that people have already invested in an existing solution. Incorporate these emotional considerations as you create new designs.

- ■ Maintain an ongoing community of exclusion experts who can fill your own gaps in perspective. Build relationships with local organizations that support excluded communities. Understand the role your product plays, or could play, in people’s lives.

- ■ Review the techniques you use to collect, sort, and analyze customer feedback. Analyze how the design of that system determines who is willing and able to contribute feedback. Whose voice is loudest? Whose is missing?