8 Love Stories

How many objects in your home are the result of inclusive design?

Maybe it’s the adjustable chair at your desk. The keyboard to your computer. Your smartphone touchscreen. Your reading glasses. These, and many more objects, are the descendants of a long history of innovations that were made to remedy exclusion.

Many assistive solutions that were originally marketed to people with disabilities eventually found mainstream potential. As technology improves, functionality gets better and market opportunities expand. In turn, businesses that recognize these opportunities are more likely to invest in making the design of that product highly usable and beautiful.

This remains true for a number of rising technologies. Speech recognition and voice commanding were, in part, initially designed for people with disabilities as a way to interact with computers without using a keyboard, mouse, or screen. Today, millions of people are talking to their cars and household devices to get directions, check the weather, and order pizzas using the same core technologies.

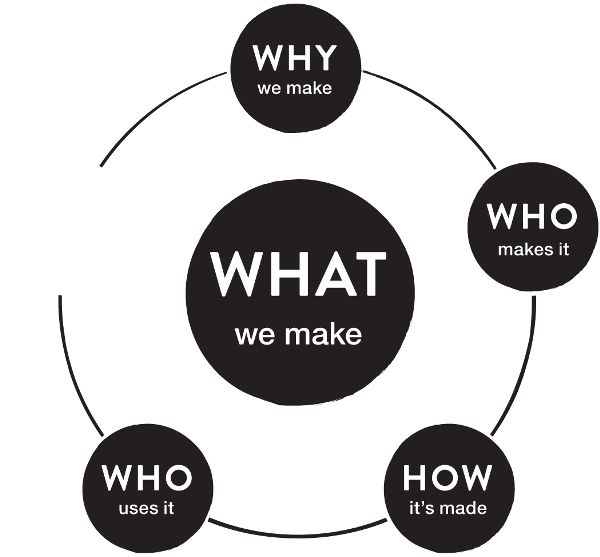

Problem solvers are often eager to start at this point on the cycle, jumping to solutions. This makes it a powerful way to make the business case for shifting toward inclusion.

The deep exclusion habit in what we make is the fixed meaning we assign to objects. A classic creative thinking exercise is to imagine multiple ways of using a typical brick. A brick could be used to build a wall. This fits the expected context and application of a brick.

A brick can also be utilized to hold a door open in the summer. It can be heated and used to cook a meal. Or ground into dust and used as sand. When we change the shape, context, or purpose of an object, it can take on a new meaning.

By stretching our assumptions about the purpose of an object or environment, we can explore how that solution flexes to be whatever a person needs it to be. The signature trait of an inclusive solution is how it adapts to fit each unique person.

This stretch of creativity can be particularly challenging for problem solvers who think about excluded communities and accessibility in fixed ways. A brick is a tool for building walls. A screen reader is a tool for someone who’s blind. Video captioning is a tool for people who are deaf. Accessibility products are often thought of as fixed and specialized solutions for people with disabilities.

As a result, accessible solutions often lack thoughtful design. Physically assistive objects like canes, wheelchairs, prosthetic limbs, or support braces can resemble the cold, medical objects of a surgeon’s operating room: steel metal bars, rough materials, industrial-grade plastics, and lifeless colors. Everything about the design can feel like a cue to the user, and to others around them, that they are a patient in need of help.

The same is often true in the creation of digital products. When a solution is treated as “for disability” or “for accessibility,” there’s often little or no attention paid to the design. A solution might meet all of its functional requirements but still lead to emotional or aesthetic mismatches that can be equally alienating.

Assistive devices, in particular, often play an intimate role in a person’s life. They become much more than just objects. They can be an extension of a person’s independence, beauty, strength, and connection with the world.

The fixed way of thinking about assistive objects often triggers a few common questions before leaders are willing to invest in inclusion:

- ■ What is the business case for it?

- ■ What is the return on investment?

- ■ How can you prove that it works?

Before we dive into business justifications, it’s helpful to study tangible examples of innovations that grew out of mismatched designs. A person who has experienced a great mismatch is likely to take an object that was intended for one purpose and use it in new ways. A desire to participate demands that they work creatively with what’s available to resolve the mismatches for themselves.

Here are some of my favorite examples of inclusive design and the stories behind them.

The Flexible Straw

Joseph Friedman was at an ice cream shop with his young daughter. Sitting at the counter, she was having a hard time drinking her milkshake through the straight paper straw without spilling the drink. Friedman inserted a screw into the straw and tightly wrapped a wire around it to make a flexible joint.

That bend in the straw made it possible for his daughter to comfortably enjoy her beverage. But it also works well for anyone who’s unable to hold a glass to their mouth, or reclined in bed from illness or injury. It also benefits anyone who’s reclined on a beach, enjoying their favorite vacation beverage.

Typewriters and Keyboards

One of the first typing machines was invented with a woman named Countess Carolina Fantoni da Fivizzano, in the early 1800s. She was the friend and lover, according to some sources, of Italian inventor Pellegrino Turri. The countess slowly lost her vision at a time when the only way for someone who was blind to send letters was by dictating their note to another person, who would transcribe the message to paper.

In order to keep their communications private, the Countess and Turri invented a machine that could be used to write notes by pressing a key for a single letter, raising a metal arm to press each letter into carbon paper. This invention made writing accessible to people who are blind, but many derivatives have evolved over the past two centuries into the modern-day keyboards for computing and mobile devices.

FingerWorks

Wayne Westerman wanted to create a method of interacting with a computer that required no force in the hand. He was motivated, in part, by his own severe case of carpal tunnel syndrome. His company, FingerWorks, developed a way to replace a keyboard with a touchpad for each hand.

They initially marketed their invention to people with hand disabilities and repetitive-strain injuries to their arms. The company had a base of passionate customers who came to depend on FingerWorks products in their daily computer usage. There was also an increase in customers who were interested in the design as an easier way to navigate their computer, regardless of their abilities or limitations.

FingerWorks sold their technology to Apple in 2005, enabling the tech giant to build their first gesture-controlled multitouch interface, the iPhone. Westerman is listed on a 2007 iPhone patent.1 However, in the process, the original FingerWorks product was discontinued.

PillPack

The childproof cap on prescription bottles was invented in the 1960s, about the same time that manufacturers started to apply candy coating to pills of aspirin. They needed a way to ensure that children couldn’t access the bottles.

However, childproof caps are hard for everyone to use, not just children. People with limited dexterity of their hands, many of them due to age or injury, have a particularly difficult time opening a childproof bottle. Further, for people who take multiple medications, the risk of mistaking medication can be serious, even deadly, and a curved surface of a pill bottle increases this risk by making it difficult to read instructions on the label.

PillPack founder and second-generation pharmacist T. J. Parker and his team partnered with IDEO to design a better way to deliver prescriptions. They focused on people who faced the greatest mismatches in using medication. Some of them were long-term cancer patients who took over a dozen different medications in one week.

Their final solution wasn’t simply a more accessible pill bottle. They reimagined the prescription delivery service. A patient can order their prescriptions through PillPack and their medication arrives in presorted packages. So rather than the patient needing to organize their medications manually, they simply remove one small pouch that contains the right medication for the right time of day.

For the 30 million people who needed to take more than five prescription medications in one day, this solution drastically improves safety and convenience. PillPack is now working to improve the system of interactions between patients, pharmacies, doctors, and insurance companies, with the launch of their comprehensive service Pharmacy OS.

Sonification of the Stars

Wanda Díaz-Merced is an astronomer, born and raised in Gurabo, Puerto Rico. A passionate math and science student, she and her sister dreamed of riding in a space shuttle. While studying astronomy, she started to lose her eyesight. For an astronomer, one of the key ways to study data from astronomical events is through visual illustrations. As her eyesight changed, Díaz-Merced worried that she wouldn’t be able to continue to practice and grow in her profession.2

She started using a technique called sonification, which makes it possible to “listen” to the stars by turning the data from stellar radiation into audio files. She matches the patterns of the data to pitches of sound. During her PhD research she explored new and better techniques for sonification of astronomical data. She wrote:

Sound offers a way to increase sensitivity to visually ambiguous events embedded in the kinds of data space scientists and astronomers analyze. Radio waves are conveyed by drums, x-rays by the harpsichord, and so on.3

Díaz-Merced continues to practice astronomy at a world-class level. Sonification also improves access to astronomical data for a much broader group of people. In particular, for any astronomer who is unable to distinguish the colors used in a data visualization or anyone who’s losing their vision due to age or injury. And for practitioners in any data-oriented field, using the combination of audio and visual information gives them greater access to the nuances of their data.

Vint Cerf is best known as a father of the Internet. He’s considered one of the primary architects of its early development. In 2002, Cerf authored “The Internet Is for Everyone,” a summary of what makes Internet access a human right, key threats to that access, and a plea for the Internet to be engineered in ways that make it usable by anyone in the world. To this day, Cerf asserts the importance of accessibility: “It’s almost criminal that programmers have not had their feet held to the fire to build interfaces that are accommodating for people [with disabilities].”4

He also created some of the earliest protocols for email. Cerf is hard of hearing and his wife is deaf. At the time, they couldn’t use a telephone to communicate. His work on email started, in part, as a way for him and his wife to stay connected when they weren’t together in the same room.

Email, of course, is today nearly as ubiquitous as the Internet. Along with closed captioning and subtitles, it has become a key technology for people who are deaf, have hearing loss, or are simply separated by time and space.

Morgan’s Inspiration Island

In the blazing summer heat of San Antonio, waterparks are an important place for children and their families to cool down and play. One waterpark is named after Morgan Hartman, who, with her parents Gordon and Maggie, built this “park of inclusion.” They were inspired to do so after years of being unable to find great play spaces for Morgan, who has cognitive and physical disabilities. They set out to create a place where children with and without disabilities could play together in a barrier-free environment.

There are a few things that make Morgan’s Inspiration Island extraordinary, beyond its colorful water features and accessible design.

First, the Hartmans included a wide range of people with disabilities and specialists in creating the park. Second, they developed ways to adjust water temperature in real time so it can be personalized to a child’s sensory needs. Third, they worked with engineers at the University of Pittsburgh and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs to stock the park with motorized wheelchairs that are powered by compressed air, a design called the PneuChair.5 The chairs are safe for water play and only take 10 minutes to recharge.6 And lastly, the park is free of charge to anyone with a disability.

Many of these examples are love stories. In fact, love is a common trait in the creation of inclusive solutions. Some stories center around a person who was personally affected by a mismatched design. Their love for a profession or lifelong passion for an activity put a sharp focus on how it could be improved. Then they worked directly on building a better solution.

Other stories come from a mismatch that loved ones faced when something interrupted their connection to each other.

In all cases, people worked with their intimate understanding of exclusion, and with the participation of excluded communities, to design a solution that went on to benefit a wider group of people. There are many more stories of inclusive design, some that reach massive commercial success and others that are working quietly in the background of everyday life. Drawing from these examples, here are four ways to start building a business justification for inclusion:

1. Customer Engagement and Contribution

Engagement with a product increases when it’s easier to use. The key to this business justification is to demonstrate exactly how mismatched designs are affecting real customers. Work with excluded communities to record the challenges they face when using your product. Detail the kinds of hacks that they use to make the product work. Make it crystal-clear and tangible. Present these stories to leadership teams as obstacles to customer engagement and explain how removing those specific mismatches can reduce the friction for many more customers.

Another type of engagement happens when customers contribute to the development of your product. Most types of technology and how they’re made are largely mysteries to the general public. Yet these solutions play a primary role in people’s daily lives. Their inclusion can mean more to them than you realize. Meeting in person and incorporating their input can increase their sense of belonging with your brand and product. Listen carefully to people and pay attention to the emotional connections. Share the stories of how they influenced your design decisions.

2. Growing a Larger Customer Base

It can seem counterintuitive to start with a sharp focus on excluded communities. The strength of this approach is that it outlines clear constraints, helping teams build a deep understanding of how to connect with a wider target audience.

In a similar way, aspirational brands commonly focus on an elite community to build mass-market products. For example, working with world-class athletes to build a new footwear line. Or partnering with blockbuster filmmakers to explore augmented reality experiences. Stronger constraints can push designers and engineers to innovate. The key is to do so in a way that translates to a broader market by finding ways to make the solution relevant to a general audience.

Another way to build a business case for inclusion based on market size is through the persona spectrum. Quantify the number of people whose abilities lie within the permanent, temporary, and situational categories of a spectrum of exclusion. If more is better, this argument is one way to present inclusive design as a significant market opportunity.

3. Innovation and Differentiation

Leaders are often surprised by how inclusion can fuel innovation. Accessible solutions, in particular, have a history of seeding innovations that benefit a broader audience. This is for two reasons.

First, many companies have decades’ worth of ideas and prototypes that they’ve developed but never released into the world. These solutions often sit unused, like a pantry of ingredients in a kitchen. Then, with a shift in perspective or context, an ingredient that was originally intended for one purpose becomes useful in a new way. When teams shift toward inclusion they discover new solutions, but also new ways to make use of existing but unused solutions.

For example, screen contrast. Computer displays can be adjusted to increase the contrast in colors between different elements, like text and the background it sits against. This feature was vitally important to people with types of low vision that make it difficult to distinguish between objects on a screen if their colors are similar.

Screen contrast became relevant to a much wider group of people once mobile phones arrived. Suddenly, anyone who was using a phone in bright sunlight had a hard time reading the information on the screen. As smartphones evolved, they used existing screen contrast technologies to automatically adjust a screen and make it readable outdoors. A new problem created new relevance for an existing technology, improving the product for a wider group of customers.

Second, innovation is amplified by new perspectives. Through inclusive design methods, a team learns how to open their process to include people with complementary ability biases and new kinds of expertise. Sometimes the person who can have the greatest impact on a solution is someone who has relevant expertise but isn’t deeply involved in the technical intricacies.

Many inclusive innovations don’t require a dramatic reinvention of technology. They don’t require tearing down existing solutions to create new ones. Often, it’s just applying a new lens to the resources that already exist, and forming new combinations of existing solutions. It starts by employing new perspectives to reframe the problems we aim to solve.

4. Avoiding the High Cost of Retrofitting Inclusion

Many teams and companies treat accessibility and inclusion as an add-on, something to consider only in the final stages of completing a product. It’s the unfortunate result of the bell-curved belief in an average human. A team that treats inclusion as an afterthought focuses first on people they imagine are most like themselves, especially in ability and in cognitive and societal preferences. They commonly believe that this group of people represents the majority of their audience.

Conversely, they will assume that demographically underrepresented groups of people, like people with disabilities, are edge cases, a small percentage of the population that doesn’t represent large opportunities for revenue. This is simply a myth. The myth of the minority user.

After decades of building products with an average-human mindset, there is a lot of neglected accessibility work that needs to be addressed. While it’s hard to gauge exactly what percentage of all websites are inaccessible, a growing number of accessibility audit firms will tell you that their clients are often surprised at how many of their websites and digital products don’t meet legal standards for accessibility. It can take huge resource investments to fix these basic issues. This is the high cost of treating accessibility as an afterthought.

Another way to quantify the cost of retrofitting inclusion is the number of lawsuits and public relations missteps companies face when they release discriminatory solutions. From aggressive startups to careful tech incumbents, there are plenty of examples of how costly it can be to neglect issues of inclusion during the product development process.

Cathy O’Neil, author of Weapons of Math Destruction, does an excellent job of detailing the potential dark depths of human biases that are baked into technology.7 Beyond the accidental chat bot that’s trained to spew hate speech, or a selfie filter that resembles insensitive racial caricatures, O’Neil provides examples of how machine learning is amplifying the cycle of exclusion on a massive scale, from predictive policing to the algorithms that determine what advertisements show up in your phone. The cycle of exclusion is amplified when machines are coded through human bias.

Ideally, every new product or project would consider inclusive design from the beginning, as a way to proactively save time and resources. There would be no retrofitting required. More feasibly, inclusive design needs to happen when and where it can, while always pushing to happen earlier in the development process.

The best way to do this is to weave inclusive design methods throughout the entire process of developing a solution. There is no one-size-fits-all approach to practicing inclusive design. Each company needs to employ a combination of methods that complements their existing processes.

Beautiful Objects, Human Emotions

The cycle of exclusion culminates with the solutions that we introduce into the world. What we make is a powerful starting point in the cycle of exclusion. It can spark the imagination. It’s the point in the cycle that embodies our excitement for innovation.

Introducing a new technology into society can have a profound impact on how people feel and behave. Sometimes it’s an intense obsession, like Pokémon Go. At other times, it’s a lukewarm affection that grows into a deep dependency, such as touchscreen smartphones. The relationships between humans and objects are filled with emotions.

Being rejected by exclusionary designs can lead to negative emotions. In contrast, a design that fits a person’s unique body and mind can have a positive emotional impact. Whether it’s the beauty of listening to the sounds of a distant star or the sense of adventure that comes from making new friends in a water park, the mark of a successful inclusive solution is that it’s both a functional and an emotional fit.

In many ways, people are slower to change than technology. Building inclusive solutions doesn’t mean that everyone has to personally embrace the values of inclusion. As we discussed at the opening of this book, inclusion can easily be mistaken for being a nice person. What if, instead, the skills of creating inclusive solutions were the measure of a successful engineer, teacher, civic leader, or designer?

What if, rather than trying to change how problem solvers feel about inclusion, we could build inclusivity by changing how we create solutions? Could that be a faster path to a more inclusive society?

What we choose to make shapes the future of who can participate in and contribute to society. Mismatches can help us stretch our thinking far beyond technology for the sake of technology. A brick is more than a brick. The objects that assist us are more than accessories. Inclusive methods can help ensure that in our pursuit of innovative solutions we are also making solutions that are humane.

Takeaways: How Inclusion Drives Innovative Outcomes

Exclusion habits

- ■ A limited willingness to imagine how a solution in one context can adapt to provide new kinds of value in a different context.

- ■ Only focusing on functional outcomes and ignoring emotional mismatches.

How to shift toward inclusion

- ■ Assess the greatest mismatches in what you make. What barriers currently exist, and how would adapting those barriers open access to more people?

- ■ Explore how a solution can adapt to be whatever a person needs it to be. Focus on creating flexible systems that fit people in unique ways as they move from one environment to the next.

- ■ Seek out inclusive-design love stories that already exist in your business. How are people using and adapting your solutions as a way to connect with the people and activities that they love?

- ■ Build a business case for inclusion based on how it supports:

- □ Customer engagement and contribution,

- □ Growing a larger customer base,

- □ Innovation and differentiation,

- □ Avoiding the high cost of retrofitting inclusion.