The Curve is a new way of doing business, making art or running a not-for-profit organization. It focuses on building connections with real people and finding ways to encourage or let them spend money on products, services and experiences they value. It encompasses musicians trying to make a living in an era of widespread casual piracy, charities trying to find new ways to attract donations from a technology-savvy population and a miller trying to sell premium flour to a discerning audience of at-home bakers. The Curve connects the disciplines of marketing and sales with a sprinkling of technology to offer a better way of doing business in a connected world.

The Curve comes in three parts: 1) find your audience; 2) use all the tools at your disposal to figure out what is important to them; 3) let them spend anything from a little to lots (and I do mean lots) of money on things they truly value.

Finding an audience or customer base has always been an important part of any business. The discipline of marketing has evolved over the past two centuries to address that challenge. In the last thirty years, a new tool has emerged to change the rules. The internet has made it possible to share information and ideas globally in a way that was previously unfathomable. On the one hand, this has led to a wave of casual piracy and filesharing that has reduced the revenues of the recorded music industry from $14.6 billion in 1999 to $6.3 billion in 2009, a drop of $8.3 billion in annual revenue.1 On the other, it has seen an explosion of new content reaching new audiences, whether that is the 100 million views that independent musician Alex Day has garnered on YouTube, the 80 million registered users of free online game DarkOrbit or the 25,000 users who subscribe to Home Depot’s series of practical do-it-yourself videos.

This book posits the theory that free stuff – whether pirated, part of a marketing budget or given away by businesses or creators – is the starting point in a relationship with customers or audiences. It doesn’t even have to be free: Nespresso coffee machines, Canon inkjet printers, Sony PlayStations and Gillette razors are all sold at low or negative margins and make their money from the ongoing relationship they have built with their customers. While the razor-and-razor-blades model is long established, this book argues that most companies don’t go far enough in understanding their audience and focusing on moving low-spending customers along the demand curve – while also identifying the superfans who will be the backbone of their business.

The long battle to fight free content will prove to be pointless, although there is logic in not jumping to a free price point faster than necessary. It will be pointless not because the pirates will win but because the competition will start to discover how to use free more effectively. It will figure out how to use the Curve to give something away to attract an audience and make money from that audience somewhere else in the value chain. The real disruptive threat comes from competition, not piracy.

In the short term, not going free may well be very successful. Artists like the Eagles, the Rolling Stones, the Beatles and Pink Floyd can keep their music away from streaming services like Spotify or Pandora and away from YouTube in order to protect their value. They can continue to sell albums, memorabilia and, in some cases, live tours, to an audience of baby boomers who discovered their music on the radio, through word of mouth or by copying music to cassette tape.

What they won’t be doing is finding new generations of fans. The audiences who will grow up, get jobs, earn money and start spending that money on experiences and physical artefacts they truly value. A record label pursuing this strategy is like a hidebound oil exploitation business that owns an oilfield and is pumping out the oil using techniques developed in a different era. It is not an exploration business, seeking out new reserves, and neither is it embracing new techniques to extend the life cycle of its existing resources.

The Curve says that most people in the world want to pay nothing or very little for what you offer. Statistically, amongst the 7 billion humans on the planet, demand for your offering is a rounding error. Fixating on the challenges and opportunities at the low price points is a mistake anchored in twentieth-century thinking, focused on the wrong scarcities and held in place by the tyranny of the physical.

In this book, I will argue that the era of the mass market is ending and the tyranny of the physical is eroding. That the web has enabled businesses and creators to make one-to-one connections with their customers and audiences. That smart businesses and creators will focus on allowing their biggest fans and best customers to spend lots of money on things they truly value. I will describe games businesses where players spend tens of thousands of dollars on a single game and Kickstarter campaigns where 15 per cent of the supporters generate half the income.

Many people are trapped in a world view that sees price as being fixed, and where the only way to make more money is to increase the volume of products or services sold. But things have changed. We now live in a world where it is cost effective to offer customers products at very different price points. Successful businesses, creators and non-profits will stop thinking in terms of units sold or number of donors and instead start thinking about average revenue per user. Artists and creators will learn how to connect with their fans, to provide them with context for their spending and to allow those fans to become part of the journey of creation. They will still be able to finance their art, even as they give it away for free.

We will see how the concept of value is changing. In the developed world where consumer goods are as accessible and as cheap as they have ever been, companies need to compete on something other than price. I will show how value is rooted in evolutionary psychology as a means of self-expression within a social context. I will show where value lies and how you can create it through a careful application of the Curve.

Finally, I will explain how technology is the glue that holds this together. The web has enabled customers and fans to have one-to-one connections with the companies and artists they patronize. A smart organization will use this connection to allow their customers and fans to spend as much as they want – a figure that is probably much higher than you think. Customer Relationship Management (CRM), analytics, behavioural modelling and other technologies are a key part of being a successful Curve organization.

Many companies, creators and charities are already using many of the ideas and concepts outlined in this book. Yet many of them are not connecting the disparate elements of the Curve into a single philosophy that finds users, understands them, and lets them spend wildly varying amounts of money. The Curve joins the dots, and offers a hopeful message: the downward pressure of free competition is inevitable and nothing to fear. Smart organizations will use free to lay a solid foundation on which to build, making money and delighting their biggest fans in the process. They will harness the Curve.

*

To show how the Curve can work, let’s go back to Trent Reznor’s experiment and consider how he could have released Ghosts I–IV in a pre-digital age. Downloads didn’t exist, but he could still have offered the standard CD at $10, the Deluxe Edition for $75 and the Ultra-Deluxe for $300.

The big problem would have been distribution. Every music store in the world might stock the standard CD, but where to send the 2,500 Ultra-Deluxe Editions. Would Londoners buy fifty copies? How many should record stores in San Francisco get? Were there significantly more fans in Cleveland, where Reznor first got his big break?

Reznor, or his label, would have had to judge where to send the premium items. In some cases, they would guess right, and the Ultra-Deluxe Edition would fly off the shelves, but in others the fabric slipcases would moulder in the stockroom, gathering dust and falling in value until a manager put them in a bargain bin to make way for new stock.

With the emergence of the internet, such problems have been eliminated. Reznor was able to sell his Ultra-Deluxe Editions directly to fans from the Nine Inch Nails’ website with no intermediaries. It didn’t matter whether his fans were in Tulsa, Tonbridge or Toulouse, they could find the Nine Inch Nails website and pay their $300.

The challenge was to make sure that these fans knew about the music. The free download of Ghosts I and the inevitable piracy of Ghosts I–IV were a marketing channel that enabled Reznor to find and communicate with the 2,500 fans who were prepared to spend $300 on his Ultra-Deluxe Edition and the thousands more who liked his music enough to buy the physical or digital versions he offered from his site.

It did more than that, though. Reznor was trying to persuade his biggest fans to spend $300. He needed to make sure that they felt they had received value for their money. Some of that value appeared in the extra content: the books, the artwork and so on. Some of it was in the production values: glossy printing and fancy covers. Some of it was in the scarcity value: only 2,500 copies, each autographed by Reznor. All of these additional elements of value, however, make most sense in a social context. Reznor created value by widening the awareness of his music as much as possible, such that when a friend visited the house of a true Nine Inch Nails fan, he would say something like, ‘Wow, you’ve got one of the limited editions of Ghosts I–IV. That’s so cool.’ The value of the scarce and expensive Ultra-Deluxe Edition was enhanced by the awareness of the music that Reznor’s approach to sharing his work for free created. Far from treating free as an enemy, Reznor harnessed it to spread the word and then worked to move his fans along the Curve to becoming high-end, extremely valuable, customers.

To many companies, the emergence of free is a terrifying prospect. Trapped in an analogue world view, they are transfixed by the spectre that digital distribution is a race to the bottom, an inevitable slide to a price of zero that will destroy entire industries unless it can be stemmed by legislation and technological restrictions. They fail to see the converse of zero. When something, anything, becomes digital, it can be shared freely at no extra cost to the creator. This is an extraordinary opportunity to share; to reach new audiences; to, in the parlance of internet businesses the world over, widen the funnel.

At the same time, it erodes the notion of the mass market. The mass market – where all consumers pay the same price for the same item - is a created concept. It was created by factory owners who found cost-effective ways to make thousands or millions of identical copies of a particular product. The factory owners then worked with marketing agencies and the mass media to build consumer desire. The mass market was not driven by the desires of the consumer. What consumers thought of as their own desires were manufactured by marketing and advertising processes that were every bit as efficient as the processes in the factories that made the goods. The mass market was driven by the cost efficiencies of the producers.

Henry Ford explained the creation of the mass market in his autobiography:

Making ‘to order’ instead of making in volume is, I suppose, a habit, a tradition, that has descended from the old handicraft days. Ask a hundred people how they want a particular article made. About eighty will not know; they will leave it to you. Fifteen will think that they must say something, while five will really have preferences and reasons. The ninety-five, made up of those who do not know and admit it and the fifteen who do not know and won’t admit it, constitute the real market for any product…If, therefore, you discover what will give this 95 per cent of people the best all-round service and then arrange to manufacture at the very highest quality and sell at the very lowest price, you will be meeting a demand which is so large that it may be called universal.2

What the Nine Inch Nails experience showed was that this is no longer necessary. The amount of money a consumer is prepared to spend varies from individual to individual. Some people valued Ghosts I–IV at zero; others at $300. Reznor could reach millions of people for almost no cost and find the 2,500 who loved his music so much that they would pay a hefty premium for the Ultra-Deluxe Edition.

Reznor intuitively understood that consumer demand is variable, not uniform, and the internet has enabled companies to find and satisfy that demand. Whether in entertainment, retailing or manufacturing, digital transition allows us to respond directly to the curve of consumer demand.

The core argument of the Curve has three strands. The first is that people value products at different amounts. Historically, without the rapid communication and distribution enabled by the internet, the job of a business was to find the average price that satisfied the most demand. In the twenty-first century, it has become possible, perhaps even necessary, to be much more discriminatory in your pricing and to find ways to offer customers products and services at wildly differing price points, ranging from free to extremely expensive. We are moving away from an era in which the only way to increase revenue was to sell more units. Now it is possible to vary the price such that the biggest fans of a content creator might pay thousands of times as much as a casual passer-by. It is a totally different way of thinking about pricing, customers and customer relationships.

The second strand is that value is a very complex concept. The value of a product or service is driven as much by how it makes us feel as by its utility. Drawing on the work of biologists and evolutionary psychologists, I will show that the value of something is divorced from its cost, especially at a time when the costs of distribution are plummeting. We will explore ideas of value through the lenses of status, self-expression, mate selection and a range of other intangible factors which all affect our perceptions of value, and our preparedness to pay.

The third element is both liberating and terrifying to large businesses. I will argue that there is no point in fighting free, even though the Curve is much more focused on those customers who do want to give you money than on those who don’t. Businesses are currently trying to fight rapidly falling prices for mass-market products, particularly in the entertainment sector, with legislation, litigation and technological solutions such as Digital Rights Management. As 3D printing becomes a reality, casual piracy will hit Alessi lemon squeezers and Tiffany jewellery in the same way that it has decimated the music industry and threatens books, movies and TV.

The real risk is not that consumers will stop paying for things they value; it is that rival companies will learn how to use the unprecedented power of the internet to reach enormous audiences, potentially by giving away for free what you are trying to sell. They will then make money in different places by allowing those customers or fans who love what they do to spend lots and lots of money on things they truly value.

So you should stop worrying about free. The iron laws of economics, competition and technology mean that it is here to stay. Smart companies will instead look at how they can build upwards, embracing or accepting free, and figure out how to build close, direct, consumer relationships with customers for whom the pirated cheap version doesn’t fulfil their needs. The Curve will show you how to adapt to this new reality.

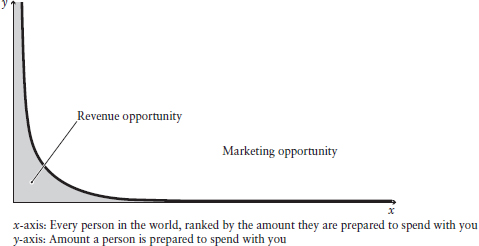

Let’s start by imagining that every single person on the planet is a potential customer or fan for whatever it is you do. All 7 billion of them. Now let’s pretend that we can peer inside their heads and pinpoint how much each individual is prepared to spend on your product, creation or service, whether that is a bag of flour, a live concert or the installation of a luxury swimming pool. Now we sort them by how much they would be happy to spend and arrange them all into a very long line. Those who would be happy to spend the most stand towards the left and those who are prepared to spend the least stand on the right.

Next, we superimpose a bar chart on top of them. Above their heads, floating in space, is a solid bar representing the amount they are prepared to spend, what we might call their individual ‘demand’. The more they are prepared to pay, the taller the bar. If they would not pay for your service, there is no bar. If they are the Sultan of Brunei, one of the richest men in the world, the bar might be very tall indeed. Drawing a line through the tops of those bars would result in a curve that looked a little bit like Figure 1.

To the right are the customers who don’t value what you do. In a world of 7 billion people, that includes nearly everyone. Close to where the curve begins to rise away from zero is the current price point for most products: $10 for a CD, $15 for a DVD, $300 for a silver pendant from Tiffany. Further to the left, as the amount each individual is prepared to pay starts rising more steeply, is where the superfans live. Those are the customers and fans who will happily spend tens, hundreds or thousands of dollars on things you create that they truly value.

Figure 1 is a representation of how much money each of your potential customers is prepared to spend with you, increasing as you move from the right to the left. The total area under the curve is the total amount of money that you might be able to generate from your buyers.

In a world bounded by physical limits, producers had to pick a single price for their products. So when albums used to be sold for around $10 in retail stores, there were fans who would have been prepared to pay much more for an album from their favourite band. That was money left on the table. Other people would have thought that the album was not worth $10. They would not buy it, wait for it to be discounted or pirate it from a friend. That was money left on the table too. With only one price point available for producers, they had to make their best guess of how much someone would pay for a product and hope that they got it right.

Figure 1: The Curve

As this book will explain, that strategy has become both less effective and no longer necessary. The emergence of the internet as a communications medium and as a distribution channel has made it possible to offer many different price points to your customers. The Curve says that if you can build relationships with your customers and your fans, often by giving away stuff that they value, you can, over time, enable them to spend lots more money on things they value even more.

Many people and businesses fixate on the part of the curve to the right, where the downward pressure of piracy and increasing reluctance to pay is, in the phrase beloved of the media industry, turning physical dollars into digital dimes. I see the rightmost section of the Curve as an opportunity. An opportunity to talk to more customers than ever before at a very low cost. An opportunity to spread your net wide, to widen your funnel, to draw more people into your orbit than was possible when physical costs limited your ability to expand. With that opportunity comes a challenge: it is harder to persuade customers to pay for that which they are becoming accustomed to getting for free. So don’t try. Instead try to find the 10 per cent or so of your audience who are prepared not only to pay, but to pay handsomely. Don’t limit how much they can spend, but allow them to spend ten, fifty or a hundred times the previous fixed price. That way you are not only widening your audience reach at the lower price points but replacing much of the lost revenue by nothing more complex than enabling those who love what you do to pay more for things that are valuable to them.

An economist or hard-headed capitalist might rub their hands with glee at the prospect of squeezing every last cent of revenue out of these customers and fans. That is not the point of the Curve. It is also unlikely to work. The Curve is about allowing customers to spend differing amounts depending on their connection with the creator, their circumstances and their own personal sense of value. It enables producers to stop focusing on one-size-fits-all products and gives them the opportunity to satisfy or delight everyone from the casual user to the most ardent superfan. The Curve is about flexibility and choice, and heralds a new era of creative and business freedom.

The Curve will come to dominate how everyone who does business over the internet views their customers. Entertainment businesses will feel it first. Music, books, movies and games are all trending towards free, yet companies who understand how to use the Curve are already making tens, hundreds, even thousands of dollars from individual fans who love what they do and are willing to pay.

As 3D printing and digital manufacturing become first a commercial reality and eventually a presence at least in every village, and possibly in every home, they will influence manufacturing industries that previously thought themselves immune to the disruption of the internet and piracy.

This book explores how a fixation with free is only half the story. How the end of the dominance of the mass market is a massive opportunity. How physical artefacts will increase in value even as the price of anything that can be shared as bytes over the internet will collapse.

It is a book that answers the burning question of the internet age: how can we sustain a global economy when the price of everything digital falls to zero?

*

Perhaps the best place to start is to ask the question: what is value? We all understand that value and price are not the same thing. I value my collection of Lego from when I was a small child not because it would be expensive to replace it – I could afford to do so – but because it transports me back thirty years to a time when I was happy, contented and relaxed. Other people might get the same emotional response from eating a homecooked meal made with fresh, high-quality ingredients, watching a football game on a large flatscreen television with friends or driving an open-topped Maserati through the French countryside.

Such emotional responses are more important than the amount of money we spend on the experience. Perhaps the simplest example of this is a daily ritual undertaken by millions of people every day: drinking a cup of coffee.3

To understand the value of a cup of coffee to a twenty-first-century city dweller, we need to go back far in time to our roots as an agricultural society. For millennia, when we lived in an agrarian world, our economy was based on commodities: the animals we could hunt or farm; the vegetables we could forage or grow; and the minerals we could dig out of the ground. The key question that concerned us was availability. If we wanted coffee, was it available at all?

As mankind became better at harnessing technology through the Industrial Revolution and beyond, commodities ceased to be the staple of our economy. As entrepreneurs and businessmen constructed factories and mills, they were able to harness economies of scale: the more product they made, the cheaper each unit of that product became to make. By manufacturing a large number of identical items, businesses could spread the cost of the factory over many units, and employ lower-skilled labour to work on the production lines. Successful businesses processed large quantities of commodities, turning them into large quantities of goods. Availability improved and consumers started to focus on price.

In the post-war period, goods began to be commoditized themselves. Manufacturing advances and then globalization pushed costs down until price no longer became the primary differentiator. The first phase was a transition from price towards a focus on quality. We found quality in the product itself, but we also found quality in the services that surrounded it: home delivery, customized products such as cars or computers, better after-sales service and so on. We moved from being a goods economy to a service economy.

Today, services are being commoditized. Availability, price and quality are becoming assumed as given. We assume we can get great quality consumer goods, great quality food and great quality service whenever we want, for a good price. Which brings me back to coffee.

Coffee is a tradable commodity with prices published on financial websites and in the financial press for investors and speculators to track. When it is roasted and ground, it turns into a good: a pound of premium blend ground coffee at my local supermarket costs just under £5 ($8), and on average that will make around thirty cups for a price of 17p per unit. When sold in a cheap café, its price might rise to £1, or £1.50. When sold in a specialist outlet such as Starbucks, that figure will probably double. Why are people prepared to pay Starbucks as much as £3 for something they could have at home for 17p? Starbucks isn’t selling the commodity of coffee, or the good, or even the service. It makes its margin by selling the experience. In fact, Starbucks is so confident in its ability to keep selling the experience that it no longer worries about telling its customers how much mark-up they are paying on the commodity of coffee.

I used to think that the reason that Starbucks charged such a lot for its coffee was because coffee was expensive. It must be, I thought, given the prices that Starbucks charged. My local Starbucks has made it clear to me that this is not true. They now have a sign up that says ‘Add an extra espresso shot to your coffee for 15p.’ That’s 15p to double the amount of coffee in my £3 cappuccino, which is about what it would cost me if I made it at home. Starbucks is so confident in its value – in the brand, in the environment, in the habits and expectations of its customers – that it is prepared to showcase the disconnect between the price of the commodity it is selling and the cost of the experience it offers on its pricing board.

In the commodity era of limited availability, we asked ‘Can I get it?’ In the goods era of manufactured product, we asked ‘How much does it cost?’ In the service era of quality, we asked ‘Is it any good?’ Now that we can get great products cheaply whenever we want, we have started asking a new question: ‘How will it make me feel?’

We can take this discussion of value further. The film industry may object that if it does not receive fair value for its product it will no longer be able to spend $220 million making movies like The Avengers.4 The problem with that argument is that the amount a movie costs to make has no effect on how much a consumer pays. We pay the same for a cinema ticket or for a DVD whether it’s a $200 million summer blockbuster or a $20 million art-house film. Price has become divorced from the cost of production.

This is playing out again and again now that distribution via the internet has become easy. Consumers are establishing their own sense of how much something is worth. A cup of coffee in a Starbucks environment is worth many times the cost of the underlying commodity. A digital download is worth less to a consumer than a DVD, or a trip to the cinema. The downward pressure of competition and consumer expectations mean that it is irrelevant how much something cost to make; what matters is how much customers value it.

The key to understanding value lies in an understanding of evolutionary theory. In 1859 Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species, a world-changing book that posited two complementary theories for how life evolved to create its most complex example: humanity. Natural selection whereby organisms adapt in response to their environment or threats from other species is well known. His other theory, sexual selection, has long been relegated to secondary status. Sexual selection posits that evolution does indeed have intelligent design at its heart: the intelligent design of choosy females selecting the males with which they wish to mate. The two theories complement each other because for a species to survive and evolve, two things need to happen: the species needs to adapt to the threats and opportunities of the environment and competing species (natural selection) and individual males and females need to pass their genetic material to the next generation (sexual selection). Sexual selection explains why peacocks have evolved huge tails, why nightingales sing so beautifully and why the human mind evolved the capacity for altruism, art, religion and politics.

Evolutionary psychologists such as Amotz Zahavi and Geoffrey Miller have used Darwin’s sexual selection theory to explain many human traits that are hard to reconcile with an evolutionary path fixated on ‘survival of the fittest’. Zahavi’s Handicap Principle suggests that certain physical traits have evolved to demonstrate conspicuous consumption of energy. The mere existence of a handicapping trait such as a peacock’s tail is a proxy for the strength and vitality of the peacock itself because only a strong, healthy peacock can afford to squander the energy needed to produce and maintain a beautiful tail. For humans, handicapping traits include our predilection for art, for humour, for gaining economic status and for conspicuous consumption. Our sense of value, evolved over millennia, is rooted in a social context, which has been amplified by the ease of sharing in a digital environment. It has become internalized and socialized. Our behaviours are no longer driven purely by sexual selection but by the habits, traits and cultural expectations that have evolved alongside them.

As a result, value is not in the realm of the bean counter or the bill of materials. Value lies in the way something makes us feel. Every time you choose to buy a branded product in a grocery store instead of the own-brand version, you are paying additional money because of how it makes you feel. When you buy organic or premium or an expensive microbrew beer, you are making a statement about who you are, to yourself or to others, with your choices.

There may be other reasons why you may be prepared to pay more. That microbrew beer might cost more because the small brewery does not have the economies of scale of a global brewing giant like Anheuser Busch. It might attract a premium due to its scarcity. It might claim to be made with organic or premium ingredients. Many of these may, however, be part of the rationalization that you make to yourself for why you believe this beer is worth the extra money. In the end, the beer may taste better simply because it is more expensive.

The theme of value will crop up time and again throughout this book. Some people value self-expression. Some value status. Some want to be the first to get something and will pay a premium for that. Other people will happily trade money for time. Many of these motivations are deeply embedded in human psychology and evolution. Understanding where, why, and what consumers value will be the key to building or maintaining a successful business in the twenty-first century.

Focusing on how much it cost you to make something, especially if that thing can be distributed electronically at almost no outlay via the internet, will blind you to the opportunities that this new era of distribution can bring you.

*

My understanding of the Curve emerged from a close involvement with media businesses since 1994, first as an investment banker covering media and technology through the dotcom boom and then as an entrepreneur working in the online and video game sectors. Throughout that period I have come to believe that many industries, particularly in the media, have misunderstood the areas of their business where they add true, sustainable economic value and where they have been able to extract value simply by the happy accident of the historic - and disappearing – limitations of physical products.

In the days before the internet, the challenges facing a newspaper business were enormous. Every day, they had to discover what the news was, decide what was worth printing, copy- and sub-edit the text, lay it out, print it and distribute millions of copies to retailers or subscribers up and down the country. Having solved that problem, it made sense for the newspaper business to bundle up all sorts of other businesses – classified advertising, weather reports, financial analysis, crossword puzzles and so on – into the same distribution channel.

Today, we are living in a period of great unbundling. I write a blog on the business of games. It has a niche audience who care very much about how the games industry is changing and how they can make money from it. I have 20,000 readers every month, an audience that is far too small for most newspaper businesses to care about. Most importantly, and unlike the newspaper businesses, I don’t need an expensive infrastructure to deliver this news and analysis. I can reach the audience interested in my blog on the business of games sitting at my computer. In my living room. In my underpants.*

Many of the elements that make up the newspaper business remain the same: the gathering of the news, the filtering and the editing. But the distribution element is going away. It’s still expensive to do that distribution. What has changed is that too few people now value that aspect of the business enough to pay for it, and since the fixed costs of printing and distribution, and the commercial and managerial infrastructure that supports it, is not getting rapidly cheaper, traditional media businesses are in trouble.

This is not a problem of piracy, or one of customers refusing to pay for high quality. It is a technological shift driving a process first described by economist Joseph Schumpeter, one that is crucial to the operation of a thriving capitalist economy: creative destruction.

Schumpeter was an Austrian-American economist writing in the 1950s. To him, the engine of growth of the capitalist system was the disruption caused by entrepreneurs innovating with new products or services at the expense of the existing companies and workers who had carved out for themselves a position of power. That power might derive from market dominance, from political support, from logistical and distribution excellence or from technological advances. Flexible, adaptable entrepreneurs attempt to find better, cheaper or faster products that fulfil a market need while incumbents struggle to adapt. Schumpeter’s work has been built on by other economists, notably Clay Christensen, who coined the phrase ‘The Innovator’s Dilemma’ to exemplify how successful companies focus on their customers’ existing needs and struggle to change business practices to meet future or unstated ones. Entrepreneurs, looking for ways to offer new products and services, bring what Christensen calls ‘disruptive innovation’ to the market.

Creative destruction and disruptive innovation are vital to the health and dynamism of a capitalist society. They are part of the reason capitalism has proven to be such a powerful force for business, technological and arguably social innovation compared with other rival ideologies. They show why it is so difficult for companies to adapt to rapid technological change and that, in the long run, their failure to adapt doesn’t matter to society at large. More accurately, it is a good thing for society. Old businesses fail and fade away. New businesses arise to take their place. The world adapts to the new behemoth until it, in turn, faces its own disruptive interruption. Think of how IBM, a manufacturer of mainframes, was disrupted by Microsoft who wanted to put a PC on every desk. How Microsoft was disrupted by Google in turn, moving the centre of computing away from the desktop and towards the cloud. And now Google must adapt to a world where search – its core business – is being disrupted by the rise of the social web and Google’s dominance of our experience of the internet via the browser is threatened by Apple’s success with smartphones and tablets.

The technology world has long been used to the pace of creative destruction. Other industries are only just beginning to feel it.

*

In 1989, a middle-aged woman suddenly imagined a book that she would write.

‘I wrote the early chapters in about an hour – as though they were being dictated to me. I wrote in longhand, on a lined copy book and I believe, though the originals are now in Boston, that few changes were made to these opening chapters when the novel was published in early 1991. Then, I stopped. I did nothing at all with them.’5

Her busy life meant that she did not carry on writing her first draft of her debut novel despite pressure from her husband to do so. Then something changed.

The woman was producing a play. After the play, she and her husband went to dinner at Scott’s restaurant, an expensive eatery in London’s exclusive Mayfair, with two friends, a couple who had been to see the play with them. Her husband said, ‘Josephine is writing a novel.’6 Josephine said, ‘Hush.’ Her friend said, ‘May I see it?’

The woman was Josephine Hart. The husband was advertising entrepreneur Maurice Saatchi. The friend was Ed Victor, one of the highest profile literary agents in the world. The book was Damage. It sold over a million copies worldwide, was translated into twenty-six languages and made into a 1992 film by Louis Malle, starring Juliette Binoche and Jeremy Irons.

That story illustrates how many people view the process of getting a book published. Be connected. It’s not about your talent, it’s about who you know. Approaching the slush pile never works.

They are not entirely wrong.

Ed Victor is a literary agent who moves in socialite circles. Not only are he and his wife Carol invited to every literary party going, but they also attend fashion, film and society soirées. As the Guardian puts it, ‘anywhere the beautiful, famous and talented are gathered, Victor is certain to be in their midst, his gentle New Yorker charm and affability concealing the fabled steely core’.7 Aspiring writers have wondered how they are going to get representation from Ed Victor. At the Hay Literary Festival, an annual jamboree of literature and the arts held in the small Welsh town of Hay-on-Wye, one audience member had a question for Victor.

‘How do I get my manuscript to you if I don’t go to that kind of party?’

‘You don’t,’ Victor replied.

Ed Victor is not a believer in the ‘slush pile’, the book publishing industry’s term for the collections of unsolicited manuscripts that sit around the office of a literary agent or, more rarely, a publisher’s office waiting to be read and evaluated, usually by a junior employee. To many writers, the slush pile seems like their only hope of discovery. They send manuscript after manuscript, printed double-spaced, single-sided on A4 paper, following specific and often contradictory instructions on whether to staple or to bind, how much biographical detail to put on each page or more. They read terrifying statistics such as ‘only 1 per cent of books from the slush pile get published’ and despair of ever bring able to find a publisher for their work.8 In Ed Victor’s world, and the world that many aspiring writers imagine to exist, getting published is not an issue of raw talent, hard work or dogged persistence; it is a matter of who you know.

There is another way.

In April 2010, a young writer in Austin, Minnesota was trying to work out if she could afford to make the trip to Chicago to see an exhibition of Jim Henson’s Muppets. A huge Muppets fan, she was happy to make the eight-hour drive, but she couldn’t afford the fuel, let alone pay for a hotel.

The woman wasn’t a stranger to hard work. She had a full-time job caring for disabled people that earned her $18,000 a year. In her spare time she wrote. Prolifically. By the time she was seventeen, she had written fifty short stories and finished her first novel (although by her own admission it wasn’t very good). Ten years later, she had seventeen completed manuscripts, mainly in the genre of young adult paranormal romantic fiction. She had also collected dozens, perhaps hundreds, of rejection letters.

Unlike Josephine Hart, this young writer didn’t hobnob with the rich and famous. Instead, she was lucky to have been born several decades later. The writer decided that if she wanted to make the trip to see the Muppets, she needed to do something radical. She offered one of her books as an ebook in Amazon’s Kindle store.

In the first six months that she self-published her books, Amanda Hocking made $20,000 selling 150,000 copies.9 By January 2012 she had sold 1.5 million copies and earned $2.5 million. As with Josephine Hart, Hollywood came knocking. In February, 2011, Canadian screenwriter Terri Tatchell optioned one of Hocking’s trilogies. Not bad for an author who had been turned down time and again by respected literary agents and publishing houses.

The stories of Josephine Hart and Amanda Hocking each represent extremes: the one of the old, privileged Establishment of publishing, the other of a new, electronic, free-for-all where talent that lies unrecognized by traditional channels can reach its audience in new, unfettered ways, freed from the tyranny of the slush pile, the agent and the marketing-led editor. They are not representative of the experience of the majority of aspiring writers, but they do highlight some persistent myths about the publishing process as well as the pace of rapid change.

Defenders of the traditional process point out that the quality of submissions is generally terrible. Blogs such as Slushpile Hell highlight howlers from covering letters including risible grammar, awful prose and a level of high-handed arrogance that would make even a literary agent blush: ‘Look, I have two international bestsellers on my hands, you can trust me and make lots of money or not trust me and miss out on making your career, either way, I’ve got the bestseller.’10

Against this background, the literary agent and the publisher are all that stands between the public and a tide of effluent, say proponents of the value of publishing. This is arrant nonsense.

There is no doubt that there is huge value in the role of the editor. Few books spring from an author’s mind perfectly formed and ready to be published, and the same is true for screenplays, for television scripts, for graphic novels, for music tracks or for video games. A seasoned and professional editor or producer can make an enormous difference to the quality and commercial success of a product. The danger is when the commercial role of the editor as gatekeeper gets mixed up with the creative role of the editor as creative adviser. The role of the gatekeeper is a function of the pre-internet world, and has a much diminished value against a backdrop of abundant digital distribution. An understanding of the Curve shows the rapid change from the era of Josephine Hart to that of Amanda Hocking. At its heart is the changing nature of what is scarce and what is abundant.

In 1989, when Hart first put pen to paper, the internet barely existed. In 1992, the year that Damage, the movie based on Hart’s novel, was released, I was at Oxford University, editing a paper called The Oxford Student. One of the reasons I remember Damage so clearly is that we had only very basic technology. We had advanced from literally cutting and pasting stories to typesetting using a desktop publishing program called QuarkXPress, but getting access to pictures was enormously difficult. If we were lucky, we could persuade the press departments of movie distributors to send us, by post, high-quality 8” × 12” black-and-white stills from the movie. I can still remember the glossy image from Damage, Jeremy Irons and Juliette Binoche in a (tastefully) naked embrace, not least because it was one of the few pictures we had. We reused it on every possible occasion.

In that era, easy access to digital content was scarce. Photographs had to be taken, developed, scanned and cropped. Film was expensive. Storing pictures was expensive. A photographer with the key to a darkroom was a huge asset to a student newspaper, reducing our reliance on publicity shots. We only had one such photographer. The distribution and sharing of content was difficult. The formats were overwhelmingly analogue.

When the ability to make copies of content is scarce, it also tends to be expensive. As an editor, I was aware of the enormous cost of printing 13,000 copies of a paper every week. (Enormous by the standards of a student union, anyway.) In the same way, a commissioning editor reviewing content from the slush pile would have been aware of the enormous cost of accepting a book into the publishing process. Not only did the book need to be professionally edited, typeset and designed, it had to be printed, sold into retail channels, and distributed. The amount of money required to bring a physical book to market was colossal, and there was no alternative.

Fast forward twenty years and almost every aspect of the process has been rendered vastly cheaper by the advance of technology. Modern word processors can do much of the typesetting of the book as the author writes. (My self-published book, How to Publish a Game, was entirely typeset in a default theme from Microsoft Word.) Design is still expensive, but designers are easier to find than ever before using websites or social media. Retail is no longer the only way to reach an audience and physical books are no longer even necessary. What was previously scarce has become abundant.

The one element that still remains incredibly valuable is the role of a good editor. Almost every piece of creation can be improved by a strong partnership between creator and editor. The creative value of the editorial role remains strong. The gatekeeping aspect is the element that is dwindling in value.

In the Amanda Hocking case there was no editor to perform either role. Hocking put her novel up on Amazon as it stood, rejected by professionals in the publishing world. There it found an audience. That audience spread and multiplied by that oldest of marketing techniques, word of mouth, multiplied by the power of social media. Naysayers will rightly point out that Hocking’s books would have been better if they had had a professional publishing organization behind them. They might have been tighter. More grammatically sound. More closely plotted. They also would not have been published.

This distinction between the creative role of the editorial function and the gatekeeping role is at the heart of the changes to the business landscape driven by the internet. A gatekeeper used to have scarce resources to allocate to publish a book. Now a self-published author can reach millions of potential readers just by uploading her content to a blog, to an eReader or to a new distribution channel.

There are those who bemoan this change. Who fear the tide of dross that will emerge when anyone, not just the privileged few, can publish and when a tight-knit cabal of English Literature graduates no longer have control over what can and cannot be turned into a book. A quick glance at the bestseller list at Christmas, packed with ghost-written celebrity memoirs and sure-fire hits from established novelists, suggests that the cabal does not always put great quality or original content first.

The demise of the gatekeeping role will lead to an explosion in creativity across all entertainment businesses, and then across all businesses. Good ideas can spread faster than ever before, fanned by the winds of social media and effortless sharing, untrammelled by the costs of distribution and finding new users, whether niche or global, at a speed and scale unimaginable when Damage was released.

With this abundance comes a new scarcity: that of attention. The problem is no longer how to get published; it is to get noticed when you have been published. That is the challenge facing twenty-first-century businesses: how to attract attention in a world of almost limitless information.

*

It is said that Samuel Taylor Coleridge was the last man to have read everything. Or at least everything that mattered. Thomas Young, born in 1773, was also said to be ‘the last man who knew everything’.11 Imagine if they lived today. When Google is busy digitizing every out-of-copyright book, and many that are in copyright, too. When a hundred hours of video are uploaded to YouTube every single minute.12 When armies of professionals, amateurs, bloggers and bystanders are creating content at every second of every day. Surely they would have cried out for a gatekeeper?

Perhaps. Or maybe they would have preferred to see ideas shared, spread and discussed widely. To see communities springing up around topics that were deemed too niche to be successful for mainstream audiences. To see topics which were dumbed down when produced for a mainstream audience reach their full potential for a niche audience that can be reached in the cheap distribution environment enabled by the internet.

(I used to use as an illustration of this emergence of niches that could not thrive under the traditional music publishing business the idea of a jazz-bluegrass-fusion band. When I first pitched this book to my agent, he immediately named a jazz-bluegrass-fusion band called Phish that he really liked. They play jazz, bluegrass and pretty well anything else you can imagine improvised into one unique whole. The niches are thriving.)*

In the world before the web, the only viable option was curation, where we as consumers let paid professionals choose which works we would get to see and which ones were destined never to be released. We had no choice: the commercial realities of distribution meant that curation was necessary to persuade companies to invest the meaningful sums of money necessary to bring a product to market. Now, in the twenty-first century, we have an alternative: filtering. The filtering model takes advantage of the fact that we can now distribute and share digital content at almost no cost and puts the quality control filter in place after publication, not before.

Traditional gatekeepers bemoan the lack of curation in today’s markets. There is no doubt that the internet is flooded with poor-quality content, mainly because of the low barriers to entry. On the other hand, quality, like beauty, is largely in the eye of the beholder. Is opera inherently more important than grime? Does Perry Mason trump Vampire Diaries? Is a blog on the business of games more or less valuable than one on the ins and outs of commercial bread making?

It no longer matters. It is so cheap to publish that anyone who creates can put their content out to be judged by the only group that matters: their audience. The gatekeepers are losing their grip on the content world. There are many challenges to the digital world, and many of the tools that we will need to make sense of the abundance of content in the twenty-first century have yet to be written. The reality is, though, that gatekeepers are losing their power. As the role of the gatekeeper diminishes, so the opportunities for the creator grow.

The Curve doesn’t apply only to art and content, although it is easiest to grasp through that lens, since the world of entertainment is the world that is being affected by the digital transition more rapidly than any other. It can apply to any business that deals with consumers.

*

Marcus Sheridan had a problem.

It was 2009 and his business was in trouble. River Pools and Spas was a twenty-employee installer of in-ground fibreglass pools in Virginia and Maryland. Before the financial crisis hit, the firm averaged six orders per month. Now they were down to two. That winter, four customers who had planned to install pools costing more than $50,000 asked for their deposits back. The company was consistently overdrawn and heading for bankruptcy. Four years later, River Pools and Spas is thriving. The company is making more revenue than it did before the financial crisis while its advertising costs have plummeted. Why? Marcus Sheridan was an early adopter of the Curve.

Fibreglass swimming pools are expensive. It’s hard to say just how expensive, because there are so many options and variables, but the cost can range from $20,000 to $200,000. Most of River Pools’ customers pay between $40,000 and $80,000. Sheridan’s business already had the top end of the Curve covered: it offered expensive, bespoke solutions to its customers’ needs. His challenge was at the low end of the Curve.

Sheridan’s response to his troubles in 2009 was unconventional. He was spending $250,000 a year on advertising on radio, television and via pay-per-click on the web. He slashed the budget by 90 per cent. At the same time, he started talking directly to his customers:

I just started thinking more about the way I use the internet. Most of the time when I type in a search, I’m looking for an answer to a specific question. The problem in my industry, and a lot of industries, is you don’t get a lot of great search results because most businesses don’t want to give answers; they want to talk about their company. So I realized that if I was willing to answer all these questions that people have about fiberglass pools, we might have a chance to pull this out.13

Sheridan started to try to answer the questions that his customers had about pools. He wrote articles about the problems and issues that affect fibreglass pools. He listed all his competitors in Virginia and Maryland in a single post. He wrote blog posts about how much they cost. Within twenty-four hours of posting about the cost, his article was the top search result for every fibreglass pool, cost-related phrase you can think of. Sheridan has generated $1.7 million in business that originated just from that single post that he wrote four years ago.

River Pools is one of the first websites that many people find when searching for the costs or problems of fibreglass pools. The company’s website acts as a resource for anyone trying to find out about pools as much as it acts as a sales mouthpiece. Sheridan is honest about the shortcomings of fibreglass pools and that gains him the respect and trust of his customers. A customer who has read a lot of Sheridan’s online material, thirty pages or more, and then books an appointment, converts to a purchaser 80 per cent of the time, compared with an industry average of 10 per cent.

What Sheridan started doing in 2009 is now known as content marketing. He is building a relationship with his audience by offering high-quality, useful information for free. He uses analytics and data tools to help him understand what his audience wants. Then he allows his customers to spend lots of money on, in his case, a swimming pool.

Different businesses, organizations or creators will adapt to the Curve in different ways. Some will find that what they do is already available for free, and will have to seek out ways to let their biggest fans spend large amounts of money on things they value. Some will have products that are naturally personalized or expensive and use the free distribution of the web to pursue a content marketing strategy. Charities will use the web to reach new potential donors and offer them a range of donation points, all in a social, connected context. Retailers will stop focusing on shifting products and focus on the average revenue per customer. All will use technology to share stuff with their customers and to track and analyse their preferences.

The Curve shows artists, retailers, manufacturers and service providers how it is still possible to make money in a world where the price of so many things is heading towards zero. It is a time filled with possibilities. To make the most of it, we need to look at what has changed to make the Curve a possibility. We will start by examining how what was once scarce has now become abundant and what was once abundant is now scarce.