TERRY COPP

Most of the world remembers the First World War as a time when ‘innocent young men, their heads full of high abstractions like Honour, Glory and England … were slaughtered in stupid battles planned by stupid Generals.’1 English-speaking Canadians, while generally accepting this view, have supplemented it with an imaginative version of a war in which their soldiers won great victories and forged a new national identity. Both of these approaches have served to promote literary, political, and cultural agendas of such power that empirical studies of what actually happened during the war have had little impact upon the historiography. Recently, a new generation of scholars has challenged this approach, insisting that ‘the reality of the war and the society which produced it’ are also worthy of study.2 If historians are to continue to study the past to further understanding of what happened and why it happened that way, they need to remember that the men and women who participated in events like the First World War were not concerned with the views of later generations. The meaning of their war was constantly changing, and since no one knew the outcome or the consequences of decisions which needed to be made, they relied upon the best information available at the time and tried to act in ways that did not violate their shared values. This essay is therefore intended to introduce readers to the events of the war as well as the way historians interpret them.

It is clear, for example, that while Canadians were surprised that the assassination of an Austrian archduke should lead to war, those citizens interested in world affairs had long been aware of the possibility of such a conflict. The enmity between Germany and France, the alliance system, and the increasingly bitter rivalry of the German and British empires were topics of informed discussion throughout most of the decade that preceded the war.3 The ‘naval question,’ which along with reciprocity of free trade with the United States, dominated pre-war political debate, sensitized many of those normally indifferent to such topics. Canadians were divided on issues of war and peace and especially divided on military and naval expenditure precisely because they thought they understood what was at stake.

French-Canadian opinion, at least within Quebec, was almost universally opposed to any form of military expenditure which might underwrite Canadian participation in foreign wars. Within English-speaking Canada there were sharp divisions between pro-empire activists, Canadian nationalists, anti-militarists and declared pacifists. While newspapers such as the Montreal Star and the Toronto Mail and Empire offered strong support for military preparedness, the Toronto Globe, the Methodist Guardian, and the voice of the western farmer, the Grain Growers’ Guide, were equally adamant about the dangers of militarism.4

Canada’s leaders played no part in the decision for war in 1914, and it is literally true that Canada went to war because Britain was at war. This statement, while accurate, does little to help us make sense of the events of August 1914 in Europe or in Canada. To achieve understanding we must answer three different questions: (1) Who was believed to be responsible for the outbreak of war? (2) Why was Britain involved? (3) What kind of war was it going to be? The answers to these questions seemed obvious to informed Canadians. Germany was threatening the peace of Europe and violating Belgian neutrality as part of an attack on France. Britain was defending France against German aggression and coming to the assistance of Belgium. The war was likely to be over by Christmas, after decisive battles between standing armies, but it might last until 1915.

The response of most English-speaking Canadians was predictable. Canada was part of the empire and must actively support the mother country in a just war which Britain had tried to prevent. This view of the origins of the war was dismissed as simplistic in the 1920s, when historians developed a revisionist interpretation which ignored evidence of German intentions. Today, the scholarly consensus presents a picture not very different from the one accepted by Canadians in 1914.5

The country’s commitment to the war effort was not in doubt, but Canada could not provide any immediate assistance. Wilfrid Laurier’s attempt to create a Canadian navy, able to defend Canada’s coasts and assist in the protection of imperial sea lanes, ended with his defeat in 1911. The Liberal-controlled Senate then blocked Prime Minister Robert Borden’s Naval Aid Bill, which offered direct financial assistance to the Royal Navy. As a result, in 1914 the Royal Canadian Navy possessed one seaworthy, if obsolescent light cruiser, HMCS Rainbow and two submarines hastily purchased from the neutral United States by the government of British Columbia.6

Canada’s regular army of 3,000 all ranks, plus some 70,000 volunteers serving in the militia, constituted a far more considerable force than the navy. Under the energetic if eccentric leadership of Sam Hughes, minister of militia since 1911, fifty-six new armouries and drill halls were built and training camps created or expanded. Hughes is usually remembered for his misguided commitment to the Ross rifle, a Canadian-designed and manufactured weapon, which proved deficient under combat conditions. But if Hughes is to be condemned for his errors of judgment, he must also be remembered for encouraging more realistic training, marksmanship, the acquisition of modern guns for the artillery, and the expansion of the militia.7

Whatever view one takes of Hughes, it is evident that no Canadian field force could possibly have gone into action on a European battlefield in 1914. This reality did not deter the minister. On 6 August he sent 226 night telegrams directly to unit commanders of the militia ordering them to interview prospective recruits and wire lists of volunteers for overseas service to Ottawa. Hughes bypassed existing mobilization plans requiring the Canadian Expeditionary Force to assemble at a new, yet to be built, embarkation camp at Valcartier, near Quebec City.

Would the original plan have worked more smoothly? Would a conventionally recruited force of 30,000 men have been ready to leave for England in October? We will never know, but it is impossible not to be impressed with what Hughes and William Price, who created camp Valcartier and organized the embarkation of troops, accomplished in just seven weeks.

Who were the men who volunteered to go to war in 1914? Desmond Morton suggests that, ‘for the most part, the crowds of men who jammed into the armouries were neither militia nor Canadian-born.’8 Most, he argues, were recent British immigrants anxious to return to their homeland in a time of crisis, especially when Canada was deep in a recession which had created large-scale unemployment. The best available statistics suggest that close to 70 per cent of the first contingent ‘were British born and bred’ though the officer corps was almost exclusively Canadian. Command of the First Division went to a British officer, Lieutenant General Sir Edwin Alderson, but Hughes appointed Canadians to command the brigades, battalions, and artillery regiments. Much the same pattern held for the second contingent: 60 per cent were British born, but their officers were Canadian.9

When news of the war reached the colony, Newfoundlanders were still mourning the loss of more than 300 fishermen in a spring blizzard. The response nevertheless was enthusiastic, and in the absence of a recent British immigrant population, recruits were drawn from a cross-section of town and outport communities. Less than 250,000 people lived in Newfoundland in 1914, but thousands volunteered to serve in the Newfoundland Regiment and the Royal Navy.10 Imperial ties were no doubt basic to this response, but many were drawn to serve by the promise of decent pay and a meaningful role in a war which could not be much more dangerous than the sea.

A recent study of ideas current in Ontario before the war argues that the rush to enlist in 1914 was due to cultural influences which ‘worked together to inculcate in young boys the notions of masculinity and militarism that would create soldiers.’ War was presented as ‘masculine event’ and a ‘romantic commitment to war had entrenched itself as a pseudo-religion in the province indoctrinating young boys with a glamorized notion of sacrifice.’11 There may be some limited value in this kind of explanatory framework when we speculate about the motives of those who sought commissions in the expeditionary force, but there is no evidence to indicate that such ideas influenced the relatively small numbers of Ontario-born, ordinary-rank volunteers.

The men who gathered at Valcartier were supposed to be at least five feet, three inches, tall with a chest measurement of thirty-three and a half inches, between eighteen and forty-five years of age, and ready to serve for one year ‘or until the war ended if longer than that.’ Officers received from $6.50 a day for a lieutenant colonel to $3.60 for a lieutenant. Non-commissioned officers could earn as much as $2.30 a day, while the basic rate for a soldier was $1.10. The Canadian Patriotic Fund, which is the focus of Desmond Morton’s chapter, provided additional support for families from private donations. The fund, with chapters across Canada, offered support only after a humiliating investigation of the recipients and then provided assistance on a sliding scale which paralleled the army’s rates of pay. A dollar a day was not far below the income of a junior clerk or unskilled labourer and was far above the cash paid to a farm worker. The army was thus an attractive proposition to many single men seeking escape from the dull routines of work or the harsh experience of unemployment. A large number of married men also volunteered, but Sam Hughes, who insisted participation had to be voluntary in every sense of the word, decided that ‘no recruit would be accepted against the written protest of his wife or mother.’ According to the newspapers ‘long lists of men were struck off the rolls’ because of this regulation.12

As the Canadian Expeditionary Force and the Newfoundland Regiment departed for England, a second contingent, which would become the 2nd Canadian Division, was authorized. This decision (7 October) was made in the context of the German advance on Paris, the dramatic retreat of the British Expeditionary Force from Mons, and the miracle of the Battle of the Marne, which saved France from immediate defeat. If the war was seen as a romantic adventure in early August, by October the harsh reality of high casualties and the prospect of a German victory created a more realistic view.

By October Canadian opinion was also deeply affected by the plight of the Belgian people. Voluntary organizations including farm groups, churches, and ad hoc committees responded with offers of money, food, clothing, and plans to aid Belgian orphans and refugees. This spontaneous outpouring of sympathy preceded the first atrocity stories, which served to further intensify anti-German sentiments and public support for participation in a just war.13

The 1st Division arrived in Britain on 14 October and reached its tented camp on Salisbury Plain near Stonehenge just in time for the worst, wettest winter in recent memory. Over the next four months the contingent trained and equipped itself to join the British army in Flanders as a standard infantry division. Major General Alderson, an experienced British officer, was given command. The establishment of 18,000 men included three brigades, each consisting of 130 officers, 4,000 men, and 272 horses. Each brigade contained four infantry battalions of approximately 900 men commanded by a lieutenant colonel. A battalion was made up of four rifle companies, each divided into four platoons. Additional firepower was provided by two sections of two Colt machine guns per battalion. The three divisional artillery brigades, equipped with modern fifteen-pounder field guns, provided the firepower that was supposed to permit troops to assault enemy positions neutralized by shelling.14

There is no consensus among historians as to how well prepared the Canadians were when they entered the line in March 1915. Desmond Morton describes the Canadians as ‘woefully unready.’15 John Swettenham, whose book To Seize the Victory16 is still a very useful survey of the Canadian military effort, emphasized the problems of the Ross rifle and other difficulties with equipment. Bill Rawling’s important study, Surviving Trench Warfare: Technology and the Canadian Corps, 1914–1918, reminds us that the Canadian artillery was not able to fire its guns until the end of January 1915 and then was allotted just fifty rounds per battery. ‘The gunners,’ he writes, ‘would have to wait until the move to France to gain any real experience with the tools of their trade.’ Rawling concludes that the 1st Division was ‘hardly a well-prepared formation,’ but notes that trench warfare was new to the ‘well-trained professional European armies as well.’17 In the official history, Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1914–19, G.W.L. Nicholson quotes the commander of the British Expeditionary Force, Field Marshal Sir John French, who reported that the Canadians were ‘well trained and quite able to take their places in the line.’ This is the sort of thing generals are required to say and has little other value.18

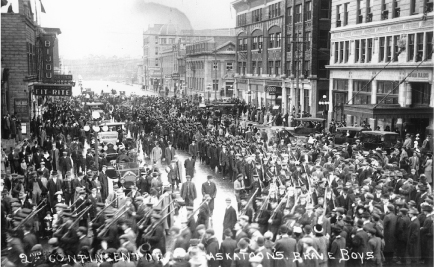

Second contingent of soldiers from Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, 1915 (National Archives of Canada, PA38523)

A recent study of the 4th Infantry Battalion offers a detailed analysis which suggests that the ‘mad Fourth’ worked hard at a comprehensive training program in both England and Europe. Paired with the Royal Welsh Fusiliers in Belgium, platoons were rotated through the trenches and prepared by repeated exercises in rapid fire, fire control, and close combat drill. When first ordered into action in April 1915, the companies leapfrogged forward in perfect order using fire and movement. They were stopped some 600 yards short of their objective and suffered heavy losses, but their counter-attack towards Mauser Ridge played a significant part in stemming the enemy’s initial advance.19 Further studies at the battalion level are necessary before firm conclusions can be drawn, but it is important to recognize that the events of the war may not lend themselves to simple notions of the transformation of raw recruits into experienced professional soldiers. The reality may well be that no Canadian formation fought a more important or more successful battle than 2nd Ypres.20

The German army’s experiment with chlorine gas, as a method of breaking the stalemate on the Western Front, has been re-examined by Tim Cook in his book No Place to Run.21 The Canadians were, he reminds us, sent into a salient which ‘protruded into the German lines like a rounded tumour, eight miles wide and six miles deep.’ The positions they took over from the French covered 4,500 yards north of Gravenstafel Ridge and were overlooked by German observers on Passchendaele Ridge to the east. ‘Shells came from everywhere except straight behind us,’ one gunner noted in his diary. The Canadians were shocked by the state of the trenches, which resembled muddy holes rather than those created in training.

Eight days after their tour of duty began a period of quiet which had settled over the salient was broken by an intense artillery barrage beginning in the late afternoon. ‘Along with the shells came an ominous grey-green cloud four miles long and half a mile deep’ which crept upon the 45th Algerian and 87th French divisions. ‘One by one the French guns fell silent only to be replaced by screaming choking Algerians running into and past the Canadian lines … The victims of the gas attack writhed on the ground. Their bodies turned a strange gas-green as they struggled to suck oxygen into their corrupted lungs. The chlorine attacked the bronchial tubes, which caused the membranes to swell into a spongy mass and ever-increasing amounts of fluid to enter from the bloodstream. The swiftly congested lungs failed to take in oxygen, and the victims suffocated as they drowned in their own fluids.’22 The Canadians were spared all but the edges of the cloud, and it was evident that they would need to launch a counter-attack to check the expected German advance. There was much confusion as well as indecision and moments of panic, but the counter-attacks mounted by the 1st and 3rd brigades that night were carried out with skill and resolution.

Early on the morning of 24 April, as the Canadians and the first British reinforcements struggled to build new defensive positions, a second gas attack began. The 15th and 8th battalions of Canada’s 2nd Brigade, holding the original lines in what was now the apex of the salient, saw the gas drifting towards them and urged each other to ‘Piss on your handkerchiefs and tie them over your faces.’ Urine, the chemistry students in the army recalled, contained ammonia, which might neutralize the chlorine. Cook quotes Major Harold Matthews’s vivid memories of the moment. ‘It is impossible for me to give a real idea of the terror and horror spread among us by the filthy loathsome pestilence. It was not, I think, the fear of death or anything supernatural, but the great dread that we could not stand the fearful suffocation sufficiently to be each in our proper places and to be able to resist to the uttermost the attack which we felt must follow and so hang on at all costs to the trench we had been ordered to hold.’23

Matthews’s emphasis on the duty of resisting ‘to the uttermost’ and fears of failure to do one’s duty may strike modern observers as strange, but his contemporaries understood him well enough. Courage and determination were no proof against the full force of the gas, however, and as the Canadians slowly retreated, wounded and severely gassed soldiers were abandoned to become prisoners or to face execution. A new defensive line some 1,000 metres further back was established with the assistance of British troops, and the next day the Germans launched a series of conventional attacks near the village of St Julien, where the famous ‘brooding soldier’ Canadian war memorial now stands. After the German advance south of the village was halted, General Alderson was ordered to recapture St Julien and ‘re-establish our trench line as far north as possible.’ This absurd order compounded the growing chaos and led to further heavy losses. Stopping the German advance was one thing; retaking ground in a salient valued solely for reasons of Belgian pride and British prestige was quite another. On 26 April yet another attack into the German positions was launched. The Lahore Division of the British Indian Army advanced until gas, used for the first time defensively, broke the impetus of the attack.24

The Canadians emerged from the battle with horrendous casualties: over 6,000 men, including 1,410 who became prisoners of war. This casualty rate, 37 per cent of the troops engaged, would never be exceeded, not even at the Somme.25 The British and Canadian press lauded the Canadian achievement and the enemy acknowledged their ‘tenacious determination,’ but behind the scenes there were serious conflicts over the conduct of the battle, including sharp criticism of Brigadiers Arthur Currie and R.E.W. Turner. Many Canadian officers were equally unhappy with the performance of senior British commanders.26 After April 1915 this tension between British and Canadian officers helped to ensure that the 1st Division became the core of Canada’s national army rather than an ‘imperial’ formation drawn from a dominion.

News of the gas attack and the valour of the country’s soldiers reached Canada on 24 April before the battle was over. The newspapers reported that Canadian ‘gallantry and determination’ had saved the situation, but they hinted at heavy losses. The Toronto News described the mood: ‘Sunday was one of the most anxious days ever experienced in Toronto, and the arrival of the officers’ casualty list only served to increase the feeling that a long list including all ranks was inevitable. Crowds scanned the newspaper bulletin boards from the time of arrival of the first lists shortly before noon, until midnight, while hundreds sought information by telephone. Historian Ian Miller, writing of Toronto, describes the dawning awareness that whole battalions had been devastated. At first it was impossible to believe that battalions such as the 15th, made up of men from the city’s 48th Highlanders, had been wiped out, and the press assumed that many were prisoners of war. When the full lists were available in early May, the truth was apparent. The 15th Battalion had virtually ceased to exist, and ‘half the infantry at the front have been put out of action.’27 The events of the spring of 1915 transformed the war from a great adventure to a great crusade. A week after the enemy introduced the horrors of gas warfare, the Lusitania was torpedoed off the coast of Ireland with a loss of 1,369 civilians, including 150 children. Newspapers across Canada published heart-rending stories about the victims and survivors of the sinking alongside further accounts of the fighting in the Ypres salient. The war was now recognized as a struggle against a brutal, barbaric enemy.

In revisionist accounts of the Great War some writers have sought to minimize German war crimes in 1914–15, but at the time Canadians recognized policies designed to inspire terror for what they were. Recently, historian Jeffrey Keshen has added to the revisionist approach, arguing that Canadians were ‘manipulated’ by elites and a ‘jingoistic press,’ which presented ‘unrealistically blithe images about trench warfare.’28 In his study, Propaganda and Censorship during Canada’s Great War, based on government censorship files, he suggests that Canadians at home were denied the opportunity to learn the realities of war and were force-fed a romantic version of heroic sacrifice.

This view of the home front is contradicted by Ian Miller’s detailed study of Toronto in which he cites examples of private letters routinely published in the press describing the war in gruesome detail. This was particularly true after the first gas attack when, to cite just one example, a letter from the front printed in the Toronto World informed readers that ‘the dead are piled in heaps and the groans of the wounded and dying never leave me. Every night we have to clear the roads of dead in order to get our wagons through. On our way back to base we pick up loads of wounded soldiers and bring them back to the dressing stations.’29

The censors could do little to prevent the printing of such letters, and they proved equally unable to control the content of articles on the war. One attempt to stop the publication30 of Robert W. Service’s gritty descriptions of his experiences as an ambulance driver was ignored by editors determined to print front-line reports from the popular author and poet. Service’s description of the ‘Red Harvest’ of the trenches, with its images of ‘poor hopeless cripples’ and a man who seemed to be ‘just one big wound,’ left no room for doubt about the ugliness of war.31 The effect of such accounts was to inspire young Canadians to enlist in a great crusade against an evil enemy.32 Historians who are uncomfortable with this reality should avoid imposing their own sensitivities on a generation which had few doubts about the importance of the cause they were fighting for.

The Canadians returned to the battlefields of Flanders on 17 May, capturing ‘one small orchard and two muddy ditches’ at a cost of 2,468 casualties. The capture of the ‘Canadian Orchard’ was a small part of a major Franco-British offensive which included a futile attempt to seize Vimy Ridge.33 Overall Allied losses in May and June totalled more than 200,000 men, a clear demonstration that battles could not be won with the weapons available in 1915. The British and French field commanders were convinced that with more and better shells for the artillery, including ones filled with gas, they would break the German defences. Lord Kitchener, who was striving to create a ‘New Army’ which would place seventy divisions in the field, was less sure. He was preparing for a long war but admitted he had no idea of how it might be won.34 It is evident that the British generals, like their French and German counterparts, were totally surprised by the harsh realities of trench warfare. They simply had no idea of how to get men across the zones of machine-gun, mortar, and artillery fire to close with the enemy. They were equally unprepared to exploit any breach in their opponent’s defensive position if it should occur.

Senior British officers, with a few outstanding exceptions, demonstrated a profound lack of imagination and initiative in the early years of the war. The first suggestions for a tracked armoured vehicle which could overcome barbed wire and cross trenches were made in Britain during the fall of 1914, but the army was uninterested. Instead, experiments were carried out by a ‘landships committee’ formed by Winston Churchill through his control of naval expenditures. The first such vehicles, known for security reasons as ‘tanks,’ were ready for use in July 1916 and employed for the first time on 15 September, though another year passed before large numbers were available.35 Steel helmets, which saved many lives, were issued by the French in early 1915, but British and Canadian troops waited another year before helmets became standard issue. The Germans made extensive use of trench mortars, but it was not until August 1915 that the British War Office authorized the mass production of the British-invented Stokes mortar.36 The shortage of artillery shells was not resolved until 1916. The public were not aware of these problems, but they were well informed about machine guns, which were said to account for German success in trench warfare.

The machine-gun movement, which became a popular crusade in Britain, was launched in Canada by John C. Eaton of the department store family, who donated $100,000 to purchase armoured cars equipped with Colt machine guns. The concept of motorized armoured machine-gun carriers was an initiative of Raymond Brutinel, a French immigrant to Canada, who organized ‘the first motorized armoured unit formed by any country during the war.’ Brutinel’s 1st Canadian Motor Machine Gun Brigade was reinforced by the batteries created in Canada, though the static conditions on the Western Front provided little opportunity for mobile warfare, and before 1918 the brigade was used primarily in a static fire support role.37

Other individuals and associations hastened to offer money for additional machine guns, which were to be provided ‘over and above the regular compliment supplied to each battalion.’ By the fall of 1915 these private initiatives were halted by Prime Minister Borden’s embarrassed announcement that all equipment required by the troops would be paid for out of the ‘Canadian Treasury.’38

The arrival of the 2nd Canadian Division in England in June 1915 raised an important question about the future of Canadian formations in the British Army. Sam Hughes was determined that they should serve together and proposed the formation of the Canadian Corps. Normally, the composition of a British corps, made up of two or more divisions, varied according to the exigencies of war, but Kitchener agreed that an exception could be made for the Canadians. Alderson was appointed to command the Corps and two Canadian militia officers, Arthur Currie and R.W. Turner, were promoted to command the 1st Division and the 2nd Division, respectively.39

Despite the evident stalemate and heavy casualties, Allied generals and their political masters agreed that the war must continue. At the Chantilly conference of July 1915 a decision was reached on a massive Anglo-French offensive to be carried out in the spring of 1916. Preparations, especially the production of enough guns and shells to destroy the enemy’s barbed wire and crush his defences, were to be the foundation of an attack they hoped would rupture the enemy front, leading to a mobile war and victory on the field of battle. The same optimism was evident within the German army, where plans for an offensive designed to win the war in 1916 culminated in the attack on the French fortress city of Verdun. The intent was not to capture ground but to bleed the French army and destroy its will to fight.40

The Canadians spent a relatively quiet winter, and it was not until spring 1916 that 2nd Division was committed to a major action. Georges Vanier, the future governor general, who was serving with the 22nd Battalion, wrote to his mother describing the emotions he felt when marching through France, ‘the country I love so much in order to fight in its defence.’41 Then, as the French and German armies tried to destroy each other at Verdun, his battalion and the rest of 2nd Division were ordered to take over positions near St Eloi, which a British division had fought to capture and hold. The British had sunk mine shafts under the German lines and set off explosions that wiped out the landmarks and created seven craters, the largest of which was 50 feet deep and 180 feet across. The attempt to relieve that British division in the midst of the battle compounded a bad initial plan, and the Canadians were soon caught up in a disaster which cost the division 1,173 casualties.42

The battle of St Eloi led to another crisis in command relationships when the Corps commander sought to dismiss General Turner and one of his brigadiers for alleged incompetence. The new British commander-in-chief, General Sir Douglas Haig, refused to confirm the decision because of ‘the danger of a serious feud between the Canadians and the British … and because in the circumstances of the battle for the craters mistakes are to be expected.’43 Canadian historians have tended to side with Alderson and condemn Turner, noting that political interference from Hughes and his representative Sir Max Aitken (later Lord Beaverbrook) saved Turner and cost Alderson his job as Corps commander.44 But the case against Turner is made on Clausewitzian grounds, suggesting that a competent commander is by definition one who reacts properly and masters the situation. If this standard is applied, uniformly few generals on either side make the grade, and we are left with fallible, stubborn, imperfect humans, unable to foresee the future and almost always overwhelmed by the chaos of battle.

The Canadians, now including the 3rd Division, spent the summer of 1916 in familiar positions north of Ypres. The enemy was still able to shell the salient from several directions, making life in the forward lines both miserable and very dangerous. Many Canadian (and British) officers expressed their bitter opposition to orders to hold and attempt to expand the Ypres salient. Sam Hughes, always suspicious of decisions made by British professional soldiers, created a major controversy when he publicly denounced the policy. By the spring of 1916 Hughes had little credibility left, and Borden moved to dismiss his troublesome minister.45

The men serving in the front lines knew little of these policy matters, which seemed remote from the soldier’s experience of war. The best social history of the Canadian Corps is Desmond Morton’s When Your Number’s Up, which is rich in detail.46 Morton notes that, except during an attack, battalions spent one week in the forward positions, with companies rotating between the three lines of trenches. Even quiet periods brought a steady drain of casualties from shells, mortars, and enemy sniping, with much heavier losses recorded during raids on the enemy trenches. Tradition has it that the Canadians invented or at least perfected large-scale raids, but this legend like many others requires revision, not to mention a more sophisticated assessment of their value. As Tim Cook has demonstrated, in the raid carried out in March 1917 at Vimy Ridge, the casualties ‘not only temporarily impaired the fighting efficiency of 4th Division, but called into question the whole policy of raiding.’47

The war also produced tens of thousands of non-battle casualties, including 7,796 who died of disease or accidental injury.48 By 1916 the army and its medical officers had begun to recognize and treat ‘shell shock’ as a traumatic stress disorder of the mind rather than a physiological reaction to explosions. This did not necessarily mean more humane treatment; many medical practitioners believed that nervous soldiers could be made to recover by using electric shock and other methods of forcing a return to duty.49 It is impossible to determine how many soldiers suffered from or were treated for shell shock, but if the ratio observed in the Second World War applies, the total may have reached 20,000.50

In the chapter titled ‘Officers and Gentlemen,’ Desmond Morton presents a series of anecdotes describing the ‘rigid class system’ which separated officers from the men in the ranks. All commissioned officers, he notes, had a soldier-servant called a batman, ‘from the Hindi word for baggage.’ Officers wore a collar and necktie and ate, whenever possible, in an officers’ mess rather than lining up to have food ladled into mess tins. Even the most junior officer was better paid than the most experienced soldier and could look forward to the prospect of leave, which was denied to the ranks. Preferential treatment was provided when an officer was recovering from wounds or coping with the trials of the military justice system. ‘In return for these privileges,’ Morton asks, ‘what did officers actually do?’ The answer ‘at least for regimental officers is that they gave leadership, took responsibility, and set an example, if necessary by dying … Officers were the first out of the trench in an assault or night patrol and last out in a retreat.’51 Not every officer was able to lead by example, and Morton presents the view, first argued by Steve Harris in his book Canadian Brass, that regimental officers were the weak point in the Canadian Corps.52 Morton’s own evidence is mixed, and a far more systematic study of the performance of junior officers is required before any meaningful conclusions can be drawn.

Much the same problem exists with regard to staff officers, brigadiers, and generals. Canadian historians and journalists have concentrated most of their attention on Arthur Currie, because he assumed command of the Canadian Corps in the aftermath of the successful battle for Vimy Ridge. To the general public Currie remains a heroic figure, but as his biographer Jack Hyatt notes, Currie was a complex man with both strengths and weaknesses. Hyatt reminds us that ‘any reasonable judgment of military leadership … requires a consideration of historical record and context.’53 It also requires some basis of comparison, and, in the absence of studies of other divisional and corps commanders, conclusions about Currie must be tentative.

For example, we are just beginning to receive balanced assessments of individuals like Major General A.C. Macdonnell, who led 7th Infantry Brigade before his promotion to command the 1st Division. Ian McCulloch, who has studied the operations of 7th Brigade, suggests that Macdonnell was an exceptional officer, who emphasized high training standards ‘and the development of a new distinctly Canadian attack doctrine.’54 Macdonnell’s colourful personality and personal bravery won him the nickname ‘Batty Mac’ and the kind of popularity that Arthur Currie, with his stiff personality, could never achieve. We know little about the other senior officers, all of whom require study.

While the Canadians endured life in the Ypres salient, the British began their major 1916 offensive: the Battle of the Somme. The Somme is now remembered chiefly for the first day, when 21,000 men were killed and 35,000 wounded,55 the worst single-day disaster in British military history. Canadians did not take part, but the Newfoundland Regiment, part of the British 29th Division, lost 272 men killed and 438 wounded from a strength of 790 men; that is why 1 July is Memorial Day in Newfoundland.56

The failure to achieve the hoped-for breakthrough did not mean the battle was over, and the Somme fighting continued throughout the summer. One of the few bright spots was the success of the Royal Flying Corps in winning air superiority over the battlefield. S.F. Wise, who wrote Canadian Airmen and the First World War, notes that with new tactics and the concentration of 400 aircraft the RFC was able to dominate the sky, forcing the enemy to find the resources to meet this new threat. Fully 10 per cent of the pilots engaged at the Somme were Canadians who had transferred from the army.57

The RFC also played a major role in the new offensive which began on 15 September 1916. The Canadian Corps, three divisions strong, was part of an attack which involved two British armies. The battle of Flers-Courcelette began with the first ever attempt to employ tanks on the battlefield. Haig’s decision to use the small number of tanks then available to assist in a set-piece attack was and continues to be criticized, because it sacrificed the element of surprise.58 It is evident that Haig believed a breakthrough was still possible in 1916, and he insisted on using whatever was available. The Canadians, attacking astride the Albert-Baupaume road, were supported by two detachments of three tanks each. According to Nicholson, the ‘presence of the tanks encouraged many Germans to surrender,’ but most were put out of action in the first hours of the battle.59 The RFC, which attacked the enemy’s trenches with machine-gun fire, may well have played a larger role in securing the initial modest gains. Despite improvements in artillery doctrine and a vast increase in the supply of shells, Flers-Courcelette quickly degenerated into an attritional battle which was to cost the Canadians 24,029 casualties. These losses included 1,250 men of the 4th Canadian Division, which fought its first battle in November 1916.

A Canadian battalion in a bayonet charge on the Somme (Archives of Ontario, C224-0-0-9-18, AO 537)

Haig’s policy of continuing the Somme battle after it was evident that there was little hope of defeating the enemy in 1916 was bitterly opposed by many British political leaders, including David Lloyd George, who became prime minister in December 1916. Lloyd George’s criticisms of Haig and the war of attrition on the Western Front would continue until the armistice, but in the absence of a convincing alternative strategy the British and French armies continued to plan to renew the offensive in 1917.60

Lloyd George was anxious to limit the slaughter in the trenches, but he was not prepared to endorse the various peace proposals put forward by American president Woodrow Wilson, the papacy, and the German government.61 The proposals were widely discussed in Canada, but since it was evident that negotiations were bound to produce a settlement favourable to Germany because of its occupation of important parts of France, most of Belgium, and large areas of the Russian Empire, few Canadians endorsed the idea of an armistice in 1917. As there was no hope of peace on German terms, the Kaiser and his chief advisers decided to employ ‘unrestricted submarine warfare’ as a means of ending Britain’s capacity to continue the war. This policy, implemented in February 1917, led to the sinking of American ships and a declaration of war against Germany by the United States on 6 April 1917.62

Allied military commanders remained committed to victory on the Western Front. The British preferred a plan to win control of the Belgian coast but agreed to cooperate with a French proposal for a coordinated Anglo-French attack designed to encircle and destroy large elements of the German army. Before the ‘Nivelle offensive,’ named for the new French commander Robert Nivelle, began, however, the enemy withdrew its forward defences to a new position known as the Hindenburg Line, some twenty miles to the east. This manoeuvre shortened and strengthened the German lines, destroying what little prospect of success the offensive had promised, but the operation was not cancelled.

The British part in the April offensive, known as the Battle of Arras, included plans for the capture of Vimy Ridge, a feature which dominated the Lens-Douai plain to the east. The Germans did not abandon the ridge when they withdrew to the Hindenburg Line, since the ridge was considered of vital importance and the defences were thought to be impenetrable. The Battle of Arras, like the rest of the Nivelle offensive, yielded little except death and destruction except at Vimy, where the Canadian Corps won an important local victory announced to the world as ‘Canada’s Easter gift to France.’ The success of the Canadian Corps has given rise to a peculiar myth, which relates the capture of Vimy Ridge to the emergence of Canada as a nation. This is a theme requiring analysis of the construction of post-war memory rather than reflecting the actual events of April 1917.63

Canadian historians have also been drawn to the battle for Vimy Ridge when seeking to examine the idea that the Corps was a particularly effective component of the Allied armies. The most systematic study of these issues is Bill Rawling’s Surviving Trench Warfare, in which he examines the changes in weapons and tactics between 1914 and 1918. Rawling argues that ‘each soldier’ became ‘a specialist with a specific role to play in battle.’ The Canadian Corps, he writes, ‘moved away from the concept of the citizen-soldier who could ride and shoot to an army of technicians which, even in infantry battalions, specialized in particular aspects of fighting battles.’64 Rawling believes that the growing sophistication of the Canadian Corps helps to explain the dramatic success at Vimy and in the battles of 1918.

There is much to be learned from this and other explorations of the evolution of tactics, but Vimy was primarily a set-piece battle dominated by artillery. The troops were carefully rehearsed to move quickly to their assigned objectives, relying on ‘one heavy gun for every twenty yards of front and a field gun for every ten yards, twice the density available in the Somme battles.’65 This enormous firepower, most of it British, together with the elaborate counter-battery work of British and Canadian gunners permitted the Corps to move steadily across the sloping, featureless terrain. By early afternoon on 9 April three of the four divisions had reached the crest of the ridge. When Hill 145, the objective of 4th Division, fell three days later, the entire ridge was in Canadian hands. The victory was costly, 3,598 dead and 6,664 wounded,66 but the attack, Rawling argues, ‘ended with a different balance between cost and results.’67

After Vimy the Corps commander, Sir Julian Byng, was promoted, and Arthur Currie took over the task of directing what had become Canada’s national army. As Jack Hyatt has demonstrated in his biography of Currie, the transition to Corps commander was fraught with personal and political difficulties. To Currie’s everlasting credit these issues did not interfere with his leadership of the Corps in action.68 In August 1917 Currie orchestrated the capture of Hill 70 on the outskirts of Lens and forced the enemy to try to retake it at enormous cost.69 Many historians regard this action as the outstanding achievement of the Corps.

Currie did his best to prevent the Canadians from being drawn into the Third Battle of Ypres, known to history as Passchendaele. Even Haig’s most ardent defenders are unable to persuade themselves that the continuation of offensive operations in Flanders made sense in the fall of 1917.70 The original plan, with its promise of an advance to the Belgian coast, may have had some merit, but by October, when the Canadians were sent into action, the battle could be justified only as an effort to pin down and wear out the German army. Attritional warfare is a two-edged sword, however, and British losses at Passchendaele were at least as great as those suffered by the enemy.71

General Sir Arthur Currie, commander of the Canadian troops in France, ca. 1918 (Archives of Ontario, C224-0-0-9-51, AO 6547)

Currie protested vigorously against participation in the battle and tried to enlist Prime Minister Borden in the cause. Hyatt suggests that his opposition was overcome only when Haig intervened to personally persuade Currie that Passchendaele must be captured. Because he had great respect for Haig, Currie obeyed, and the Canadians were committed to a battle which has come to symbolize the horrors of the Western Front.

Currie’s opposition to Canadian participation at Passchendaele did not mean that he was opposed to Haig’s overall strategy of wearing down the enemy by attacking on the Western Front. What Currie and a number of other generals questioned was Haig’s stubborn persistence in continuing operations which had little chance of success. At Passchendaele the Canadians did succeed in capturing the ruins of what had once been the village, but the cost of the month’s fighting, more than 15,000 casualties, was a price no Canadian thought worth paying.72 As Third Ypres ended, the first large-scale tank battle in history was fought at nearby Cambrai, and for a brief moment it appeared that the long-sought breakthrough had been achieved. Then the Germans counter-attacked, regaining most of the lost ground. The war would continue into 1918.

At home Canadians reacted to the war news and the endless casualty lists in varying ways. In French-speaking areas of Quebec the war had never seemed of much importance and few young men had volunteered. The exploits of the one French-Canadian battalion, the 22nd, were featured in the daily newspapers, but public opinion remained generally indifferent or hostile to pleas for new recruits. Henri Bourassa and other nationalist leaders demanded redress from the ‘Boche’ of Ontario, where French-language schools had been abolished, but there is no evidence that reversal of this policy would have altered French-Canadian attitudes towards the war. The Canadian victory at Vimy Ridge had no discernable nation-building impact in Quebec.

The situation was very different in most English-speaking communities.73 Hundreds of thousands of young men had joined and tens of thousands had been killed or wounded. Winning the war, thereby justifying these sacrifices, was a shared goal which few challenged. When the pool of able-bodied volunteers dried up in late 1916, public opinion favoured conscription long before Prime Minister Borden announced its introduction. The near unanimity of opinion in English-speaking Canada was evident in the 1917 federal election, when most opposition candidates, ostensibly loyal to Wilfrid Laurier and the Liberal Party, campaigned on a win-the-war, pro-conscription platform.74

Arthur Currie tried to keep the Canadian Corps out of politics, but the Unionist political managers were determined to use the military vote to influence the outcome in marginal ridings. The manipulations of the soldiers’ vote for partisan political purposes should not be allowed to obscure the overwhelming endorsement the men serving overseas gave to the Unionist cause.

The prospect of an Allied victory appeared remote in January 1918. The collapse of czarist Russia and the seizure of power by the Bolsheviks led to negotiations to end the war in the east. Inevitably the peace treaty, signed at Brest-Litovsk, was dictated by Germany and included vast transfers of territory. The German army could now bring large numbers of troops to the Western Front and seek victory on the battlefield before the American Expeditionary Force was ready for combat.75 The French government and military believed that the best they could hope for was to withstand the expected German attack and prepare to renew the offensive in 1919, relying on the full force of the American army. The British government shared this view, though General Haig insisted that, after defeating a German attack, the Allies could win the war in 1918 by vigorous action.76

In 1918 the Canadian Corps played a major role, out of all proportion to its relative size. One reason was the decision to maintain all four Canadian divisions at full strength rather than follow the British example and reduce the number of infantry battalions from twelve to nine. The Canadian Corps found the men it needed not through conscription but as a result of the decision to break up the 5th Division forming in England and use its battalions to reinforce the four divisions in the field. This move allowed the Corps to solve its manpower problems for the spring of 1918, though it was evident that if the war continued, tens of thousands of conscripts would be required. Currie was also responsible for improvements in the training and organization of the Corps, including a reorganization of Bruitnel’s machine gunners into a mobile reserve ‘mounted in armoured cars and directly under the control of the corps commander.’77

Between March and June 1918 the Germans unleashed four major operations, recovering all the ground gained by the Allies since 1914, capturing 250,000 prisoners, and inflicting more than 1 million casualties on the Allied armies.78 It was all in vain. The German commanders gambled everything on a collapse of Allied morale, but when the offensive ended in July, their armies, overextended and exhausted, faced a powerful and resolute Allied coalition under the command of Marshal Ferdinand Foch.

The Canadian Corps, holding ground well to the north of the main point of the German attack, was initially required to place divisions under British command, but after Currie protested, the Corps was reunited under his control. Although this policy was bitterly resented by the British senior officers, who were fighting a life-and-death struggle with the German army, Currie and Borden were adamant: the Canadians would fight together.79

On 8 August 1918 the Corps, deployed alongside Australian, British, and French formations, launched an attack at Amiens which was so successful that it became known as the ‘black day’ of the German army. S.F. Wise, who is preparing a book-length study of the Amiens battle, emphasizes the effect the Allied advance had on the German high command. ‘They had struck,’ he writes, ‘a crippling blow at the will of the enemy, surely the chief object of strategy.’80 The offensive soon lost momentum, but this time Haig agreed to break off the action and mount a new attack at Arras to be spearheaded by the Canadians. The period from 8 August to 11 November 1918 became known as the ‘Hundred Days,’ a period in which the Allied armies made spectacular gains, defeating the German armies in a series of battles which many historians believed determined the outcome of the war.81 Throughout the Hundred Days the Canadians were in action at Amiens, Drocourt-Quéant, Canal du Nord, Cambrai, Valenciennes, and Mons.82 The cost of these victories, more than 40,000 casualties,83 was high, but they were seen as the necessary price of ending the war in 1918. Recently, British military historians have concentrated their research on this period, arguing that too much attention has been paid to the attritional battles of 1916 and 1917. Developing the themes first argued by John Terraine,84 historians associated with the Imperial War Museum in Great Britain have begun an assessment of every division which fought in the armies of the British Empire. Their preliminary work suggests that many British as well as the Canadian, Australian, and New Zealand divisions were highly effective military organizations before and during the Hundred Days.85

Canadian historians have long argued that the Canadian Corps, which was continuously in action during the last months of the war, was instrumental in the Allied victory. This theme has been reinforced by the publication of Shane B. Schreiber’s book, Shock Army of the British Empire,86 which portrays the Corps as an exceptionally effective, professional organization capable of sustaining successful operations over a three-month period. A somewhat different approach to the last phase of the war has been offered by University of Calgary historian Tim Travers, who is critical of the strategic and operational doctrines pursued by Haig’s armies in 1918.87 Bill Rawling, who never allows himself to forget the human consequences of military decisions and tactical innovation, provides another kind of balance to the military effectiveness school by analysing casualty rates, which were exceptionally high in 1918.88

Canadians were not involved in the negotiations which led to the armistice of 11 November 1918, but it is evident that both Currie and Borden shared the views of British, French, and American diplomats, who were determined, in President Wilson’s words, ‘to make a renewal of hostilities on the part of Germany impossible.’ This meant that Germany would have to surrender more or less unconditionally, and so it proved. Canada’s military effort in the First World War allowed the prime minister to insist upon the right to sign the Treaty of Versailles and to secure separate membership in the League of Nations.89 Canada’s new international status was only one sign of the growing sense of nationhood felt by English-speaking Canadians.

The Canadian Corps and the Canadian people had accomplished great things together in what they believed to be a necessary and noble cause. Most Canadians held to this view of their war experience despite the rise of revisionist accounts of the causes of the conflict and efforts by poets, novelists, and historians to portray the Great War as an exercise in futility. When the decision to build a great memorial at Vimy Ridge was made, the purpose was ‘to commemorate the heroism … and the victories of the Canadian soldier.’ The memorial was to be dedicated ‘to Canada’s ideals, to Canada’s courage and to Canada’s devotion to what the people of the land decreed to be right.’90 It was this view of the war that sent enthusiastic crowds into the streets when General Haig visited Canada in 1925.91 It was this memory of the war that sustained the regular army and militia volunteers throughout the years of retrenchment and depression.

1 Samuel Hynes, A War Imagined: The First World War and English Culture (London, 1990), ix.

2 Martin Stephan, The Price of Pity: Poetry, History and the Myth of the Great War (London, 1996), xv.

3 Ian Miller, ‘Our Glory and Our Grief: Toronto and the Great War,’ PhD thesis, Wilfrid Laurier University, 1999, 28–53.

4 Newspaper opinion on these and other issues can be found in J. Castell Hopkins, ed., The Canadian Annual Review of Public Affairs (Toronto, 1914–18), (hereafter CAR), as well as in the newspapers themselves, available on microfilm.

5 A good introduction to the current research may be found in Keith Wilson, ed., Decisions for War, 1914 (London, 1995).

6 Marc Milner, Canada’s Navy (Toronto, 1994).

7 The story of Hughes’s deeds and misdeeds may be followed in CAR and the Debates of the House of Commons. See Ronald Haycock, Sam Hughes: The Public Career of a Controversial Canadian, 1885–1916 (Waterloo, 1986).

8 Desmond Morton, When Your Number’s Up: The Canadian Soldier in the First World War (Toronto, 1993), 9.

9 CAR, 1914, 180.

10 Ibid., 197.

11 Mark Moss, Manliness and Militarism (Toronto, 2001), 143.

12 CAR, 1914, 182, 227, 190.

13 Evidence for the public commitment to Belgium and its refugees may be found in every Canadian newspaper. See CAR, 1914, 228, for a summary.

14 A.J.M. Hyatt, General Sir Arthur Currie: A Military Biography (Toronto, 1987), 16.

15 Morton, When Your Number’s Up, 31.

16 John Swettenham, To Seize the Victory (Toronto, 1965).

17 Bill Rawling, Surviving Trench Warfare: Technology and the Canadian Corps, 1914–1918 (Toronto, 1992), 21, 23.

18 G.W.L. Nicholson, Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1914–1919 (Ottawa, 1962), 49.

19 Andrew Iarocci, ‘The Mad Fourth,’ MA thesis, Wilfrid Laurier University, 2001.

20 For the most detailed account of 2nd Ypres see A.F. Duguid, Official History of the Canadian Forces in the Great War, 1914–1919, Vol. 1 (Ottawa, 1938). No further volumes were published. See also Daniel G. Dancocks, Welcome to Flanders Fields, the First Canadian Battle of the Great War: Ypres, 1915 (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1988).

21 Tim Cook, No Place to Run: The Canadian Corps and Gas Warfare in the First World War (Vancouver, 1999), 13.

22 Ibid., 21.

23 Ibid., 25, 24.

24 Nicholson, Canadian Expeditionary Force, 78, 83–4.

25 Rawling, Surviving Trench Warfare, 221.

26 Timothy Travers, ‘Currie and 1st Division at Second Ypres, April 1915,’ Canadian Military History (hereafter CMH), 5, 2 (1996), 7–15.

27 Quoted in Miller, ‘Our Glory and Our Grief,’ 115, 117–18.

28 Jeffrey A. Keshen, Propaganda and Censorship during Canada’s Great War (Edmonton, 1996) xi—xii.

29 Miller, ‘Our Glory and Our Grief,’ 131.

30 Keshen, Propaganda and Censorship, 29.

31 Toronto Star, 14 December 1915.

32 A total of 42,000 men had been accepted for enlistment in the 2nd and 3rd contingents before Second Ypres. A further 35,000 men enlisted immediately after the battle and by the end of 1915 212,000 men were under arms. The Canadian-born proportion of this total was 30 per cent. CAR 1915, 208–9.

33 Nicholson, Canadian Expeditionary Force, 103.

34 Llewellyn Woodward, Great Britain and the War of 1914–18 (London, 1967), chap. 4.

35 B.H. Liddel Hart, The Tanks (London, 1959), Vol. 1, chap. 2.

36 Woodward, Great Britain, 43–4.

37 Cameron Pulsifer, ‘Canada’s First Armoured Unit,’ CMH, 10, 1 (2001), 45–57.

38 CAR, 1915, 207–11.

39 Nicholson, Canadian Expeditionary Force, 114.

40 Ibid., 160–200.

41 Deborah Cowley, ed, Georges Vanier: Soldier (Toronto, 2000), 79.

42 Nicholson, Canadian Expeditionary Force, 137–45.

43 Quoted in Hyatt, General Sir Arthur Currie, 55.

44 See the recent articles, Tim Cook, ‘The Blind Leading the Blind: The Battle of the St. Eloi Craters,’ CMH, 5, 2 (1996), 24–36; and Thomas P. Leppard, ‘The Dashing Subaltern: Sir Richard Turner in Retrospect,’ CMH, 6, 2 (Autumn 1997), 21–8.

45 The events are outlined in CAR, 1916, 260–1.

46 See also Tony Ashworth, Trench Warfare, 1914–1918: The Live and Let Live System (New York, 1980).

47 Tim Cook, ‘A Proper Slaughter: The March 1917 Gas Raid on Vimy,’ CMH, 8, 2 (1999), 7–24. But see, in the same issue, Andrew Godefroy, ‘A Lesson in Success: The Calonne Trench Raid 17 January 1917,’ 25–34.

48 Nicholson, Canadian Expeditionary Force, 535.

49 Morton, When Your Number’s Up, 198. See also Thomas E. Brown ‘Shell Shock in the Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914–1918,’ in C.G. Rolland, ed., Health Disease and Medicine: Essays in Canadian History (Hamilton, 1984).

50 Terry Copp and Bill McAndrew, Battle Exhaustion: Soldiers and Psychiatrists in the Canadian Army, 1939–1945 (Montreal, 1994).

51 Morton, When Your Number’s Up, 107.

52 Stephen J. Harris, Canadian Brass: The Making of a Professional Army, 1860–1939 (Toronto 1988), 98.

53 A.M.J. Hyatt, ‘The Military Leadership of Sir Arthur Currie,’ in Bernd Horn and Stephen Harris, eds, Warrior Chiefs (Toronto, 2001), 44.

54 Ian McCulloch, ‘Batty Mac: Portrait of a Brigade Commander of the Great War, 1915–1917,’ CMH, 7, 4 (1998), 22.

55 Woodward, Great Britain, 148.

56 Nicholson, Canadian Expeditionary Force, 507–9. See also David Facey-Crowther, ed., Better Than the Best: The Story of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, 1795–1995 (St John’s, 1995).

57 S.F. Wise, Canadian Airmen and the First World War (Toronto, 1980). See also Guy Hartcup, The War of Invention: Scientific Developments, 1914–1918 (London, 1988).

58 Trevor Pidgeon, The Tanks at Flers (Cobham, U.K., 1995), 21–30.

59 Nicholson, Canadian Expeditionary Force, 169.

60 Ibid., 198.

61 Woodward, Great Britain, 227–42.

62 Holger H. Herwig, ‘Total Rhetoric, Limited War: Germany’s U-boat Campaign, 1917–1918,’ in Roger Chickering and Stig Forester, eds, Great War, Total War (Cambridge, 2000), 189–206.

63 Jonathan Vance, Death So Noble: Memory, Meaning and the First World War (Vancouver, 1997).

64 Rawling, Surviving Trench Warfare, 217. For a parallel discussion of British tactical innovation see Paddy Griffith, ed., British Fighting Methods in the Great War (London, 1996).

65 Rawling, Surviving Trench Warfare, 219.

66 Nicholson, Canadian Expeditionary Force, 265.

67 Rawling, Surviving Trench Warfare, 219.

68 Hyatt, General Sir Arthur Currie, 74–5.

69 Nicholson, Canadian Expeditionary Force, 272–97.

70 Robin Prior and Trevor Wilson, Passchendaele: The Untold Story (New Haven, Conn., 1996).

71 Hyatt, General Sir Arthur Currie, 84–5.

72 Nicholson, Canadian Expeditionary Force, 327.

73 See, for example, Leslie Frost, Fighting Men (Toronto, 1967).

74 Patrick Ferraro, ‘English Canada and the Election of 1917,’ MA thesis, McGill University, 1971.

75 Holger H. Herwig, The First World War: Germany and Austria-Hungary (New York: 1997), 392–5.

76 Woodward, Great Britain, 324.

77 Hyatt, General Sir Arthur Currie, 102–3, 102.

78 Ibid., 105–6.

79 Nicholson, Canadian Expeditionary Force, 460.

80 S.F. Wise, ‘The Black Day of the German Army: Australians and Canadians at Amiens, August 1918,’ in Peter Dennis and Jeffrey Grey, eds, 1918: Defining Victory (Canberra, 1999), 32.

81 G.D. Sheffield, ‘The Indispensable Factor: The Performance of British Troops in 1918,’ in Dennis and Grey, 1918, 72–94. For a more critical approach, see Timothy Travers, How the War Was Won: Command and Technology in the British Army on the Western Front, 1917–1918 (London, 1992).

82 Shane B. Schreiber, Shock Army of the British Empire: The Canadian Corps in the Last 100 Days of the Great War (Westport, Conn., 1997).

83 Nicholson, Canadian Expeditionary Force, 485–506.

84 John Terrraine, To Win a War: 1918, the Year of Victory (London, 1998).

85 John Lee, ‘The SHLM Project – Assessing the Battle Performance of British Divisions,’ in Paddy Griffith, ed., British Fighting Methods in the Great War (London, 1996), 175–181.

86 Schreiber, Shock Army of the British Empire.

87 Travers, How the War Was Won.

88 Bill Rawling ‘A Resource Not to be Squandered: The Canadian Corps on the 1918 Battlefield,’ in Dennis and Grey, 1918, 43–71.

89 Robert Craig Brown, Robert Laird Borden: A Biography. Vol. II, 1914–1937 (Toronto, 1980), 155–8.

90 Canada, House of Commons Debates, 1922.

91 John Scott, ‘Three Cheers for Earl Haig,’ CMH, 5, 1 (1996), 35–40.