PATRICE A. DUTIL

On 9 December 1914, when it was obvious that the ‘war to end all wars’ was not going to end as promised by Christmas, an unusual meeting of school trustees took place in Rockland, an Ontario town east of Ottawa in the County of Russell. After the usual shuffle, retrouvailles, and handshakes, Napoléon Desrosiers, the chairman of the local separate school board, called the meeting to order and asked the board secretary, a dapper gentleman named J.A. Lombard, if he was ready to proceed. The meeting was packed. People had things to say.

A few people immediately commented about how the European Entente powers had worked ‘to establish peace and harmony in and among all classes of the various communities.’ The war had broken through barriers, it seemed. One person talked about the British Parliament’s recently passed Home Rule Bill for Ireland – which recognized after centuries that the Catholic Irish had rights to particular freedoms. Someone else remarked how France had also recognized inherent rights in annulling the edicts that had expelled religious orders. One speaker even mentioned Russia, the third leg of the Entente, and its pledge to give Poles complete liberty of language and religion.

The situation in Europe touched sensitive chords in the Rockland Separate School Board. At the same time, the board wanted to discuss ‘Regulation 17,’ a Ministry of Education directive that prohibited teaching in French after grades 1 and 2. The board concluded that the Government of Ontario’s actions in suppressing French-language schools did not ‘affect the unswerving loyalty of the French Canadian to the British Crown.’ Still, it created in their minds ‘animosity and discontent’ and ‘divided energies which should be concentrated on the triumph of a cause dear to all classes, irrespective of race and creed, and hence should, it is earnestly believed, be eliminated for the common good in the present emergency.’

The school board passed motions that encapsulated the discussion and protested the limitations on French in the schools, the discrimination in school inspections, and the suppression of school grants. They signed their petition and Lombard sent it to the Ontario premier, William Henry Hearst. A few weeks later, the premier replied by letter: ‘The government appreciates the unity of sentiment existing throughout the British Empire on the subject of the present war and is of opinion that at least one of the reasons for this unanimity is the gratitude felt by every self-governing unit of the Empire toward the Parent State in respecting and guarding the right of each State or province to legislate freely within the limits of its constitution.’ Responding to the need to address school rights, the premier could hardly have been colder: ‘The Legislature of Ontario unanimously adopted the policy upon which the Regulations governing the English-French schools are based,’ the letter continued, ‘the Regulations are in accord with the wishes of the people as expressed by their representatives in the Legislature and the Government believes in the best interests of the schools. The Government, therefore, is merely doing its duty in carrying out the school law.’1

A few days after the meeting in Rockland, a political rally involving a remarkable cross-section of French Canada’s elite, ranging from nationalistes such as Le Devoir publisher and editor Henri Bourassa and Armand Lavergne and noted Liberals such as Senators Raoul Dandur-and, Phillippe Landry, and Napoléon Belcourt, launched a campaign to raise funds for ‘les blessés d’Ontario’ (the wounded of Ontario), a campaign started by the Association catholique de la jeunesse canadiennefrançaise (ACJC).2 In the diocese of Sherbrooke, a special collection was promoted by Monseigneur Paul LaRocque; the result was a record-setting windfall of over $2,100.00.3 Within a year, this campaign would raise over $22,000 (about $330,000 in today’s currency).

In the crisis days of 1914, when the issues of participation in the war and school rights at home – the two issues that would dominate the 1914–18 period – had already intermixed, the people of Rockland turned to one man, Senator Napoléon Belcourt.4 He openly questioned the quality of a country that suppressed minority rights, and he struggled with the issue of Canada’s involvement with the Entente. At the same time he was eager, by liberal and Catholic convictions, to see Canada defeat Germany and its allies. He was not an anti-imperialist of the Henri Bourassa sort, who would argue that Canada had ‘no moral or constitutional obligation’ in helping the war effort and who equated the Ontario government with the Kaiser’s Prussians.5 As a key player in the political and legal battle over Regulation 17 and in his support for Canada’s participation in the war, Belcourt provides a remarkable prism through which French Canada’s attitude towards the war can be evaluated.

It was argued, and it seems hardly worth contesting almost 100 years later, that French Canada did not ‘do its part’ in the war of 1914–18. From the very beginning of the crisis, there have been five essential reasons advanced to explain this reality. The first reason was the arrogant attitude of governments over Regulation 17, which simply sapped the desire to participate and robbed the federal government of any legitimacy in claiming that Canada’s fight was to help the oppressed. The second related to the first, in that Regulation 17 fuelled the nationaliste anti-imperial campaign. The third was that demographic factors explained the poor numbers: eligible French-Canadian men were more likely to have families to support and work in rural areas in far greater numbers than their anglophone counterparts: in other words, there were fewer available men in Quebec in the seventeen to forty-five age group.6 The fourth reason was that French Canada did not have a martial strain in its culture: calls to arms simply fell on deaf ears. Finally, observers have long pointed to the bumbling administrative decisions made in Ottawa as the government tried to promote recruitment.7

More recently, these positions have been re-examined. Some observers have discounted the importance of Regulation 17 and argued that the ‘imperial question’ – the issue of Canada’s place in the British Empire – was far more significant. Others have argued that the urban/rural demographic explanation of French-Canadian enrolments was hardly distinctive in that Canadian-born English speakers in similar situations were scarcely more likely to sign up.8 Although the absence of a militaristic culture in French Canada is undeniable, some historians have picked up on the fact that the anti-imperialist message of Henri Bourassa was not foreign to Canadians, particularly those recent immigrants from areas other than Britain. In other words, anti-imperialism was hardly an exclusive French-Canadian position. Finally, the almost anti-French-Canadian administrative aspects of the military, both before and during the war, have been explored.

Napoléon Belcourt’s experience as a Franco-Ontarian, Quebecker, and Canadian provides a captivating perspective on French Canada’s war: contrary to the nationalistes, who could easily undermine a national war effort by pointing to the inequities in Ontario, Belcourt – the top defender of Franco-Ontarians – argued in favour of the war effort. Belcourt’s experience points to an underestimated factor in explaining French Canada’s reaction to the war: its isolationism. Belcourt feared isolationism for many reasons. He argued as passionately against isolationism in world affairs, against isolationism towards Britain, and against Quebec’s growing isolationism within Canada as he did against the forced isolation of Ontario’s French-speaking minority. Even though it has been a constant in the French-Canadian outlook or mentalité, this attitude, surprisingly, has not been clearly identified as part of the fabric of French-Canadian ideology.9

Belcourt knew that any effort to encourage a broadly ‘national’ participation was unlikely to yield results while English Canada was brazenly redefining the rights of citizenship: indeed, the actions over Regulation 17 and over conscription threatened to deepen French Canada’s isolationism. With two issues intimately linked in a manner that he did not like, Belcourt was eager to see the schools situation in Ontario resolved and a consensus on the degree of Canada’s enlistment effort because he saw both questions tearing at the Canadian fabric.

Napoléon Belcourt was the son of Ferdinand Belcourt, businessman and member of Parliament for Trois-Rivières, and Marie Anne Clair. The Belcourt ancestors had settled in the Batiscan area in 1675, but the Belcourts were in Toronto in the summer of 1860, preparing for a parliamentary session. Mme Belcourt delivered her child in the capital city of the day while her husband attended to politics (the capital shifted between Canada East and Canada West in those years). All his life, Belcourt would joke that ‘he had taken his precautions’ by being born in Toronto on 15 September 1860.

Young Napoléon did not grow up in Ontario. He attended the Séminaire St-Joseph in Trois-Rivières, falling under the influence of Monseigneur Laflèche.10 He then attended law school at Laval, graduating summa cum laude in 1882. Called to the Quebec Bar in that year, he was drawn to the province of his birth and established an office in Ottawa two years later. ‘He was my companion at the university,’ Senator Raoul Dandurand recalled, ‘and we were both called to the Bar of Montreal at about the same time. I can still see him coming in to tell me he had decided to establish himself on the Ontario side of the Ottawa River, in a community where, although some lawyers from across the river had offices there; no French lawyer had ever practiced at the bar.’11 He married Hectorine Shehyn in January 1889, the daughter of Quebec Senator Joseph Shehyn, and they had three daughters, Virginie Béatrice (1890–1966), Gabrielle (1892–1986), and Jeanne (1894–1963). Hectorine died in 1901 and on 19 January 1903 Belcourt married Mary Margaret Haycock. Together they had three sons, Jean Wilfrid (1904–85), Paul Lafontaine (1906–79), Victor Philippe (1908–65), and a daughter who died within the year of her birth in 1912.12

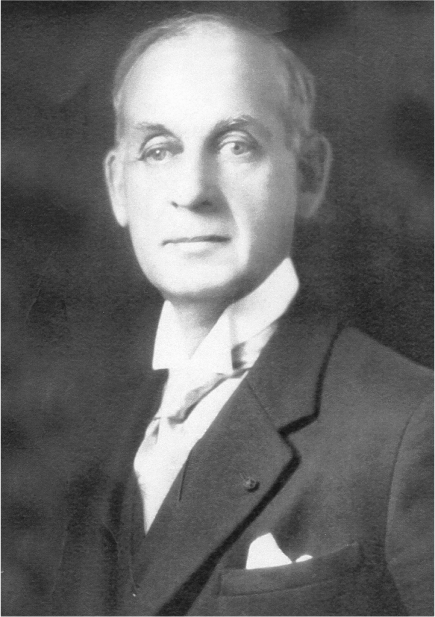

Napoléon Antoine Belcourt, n.d. (photographer unknown. Collection of Marc L. Belcourt)

Although a busy family man, Napoléon Belcourt proved a remarkable convener. His homes, first at 489 Wilbrod and then at 27 Gouldburne, and his offices in the National Bank Building at 18 Rideau Street (across from the Chateau Laurier) and later in the Castle Building at 53 Queen Street were important gathering points for Catholic, francophone, and political circles in Ottawa.13 Belcourt wasted no time in following the family tradition of active involvement in politics. An early supporter of Wilfrid Laurier, he first ran (at age thirty) in the federal election of 1891 in the city of Ottawa, but he was defeated. He tried again in 1896 and was elected in the majority that carried the Liberals to power. He was re-elected in 1900 and 1904. In 1904 he was named speaker of the House, a post he held for three sessions. In 1907 Laurier named him to the Senate. According to his friend C.B. Sissons, the noted Victoria College (University of Toronto) historian, Belcourt was ‘tall and spare, with the dignity befitting a former Speaker.’14 Omer Héroux called him a ‘noble nature.’15 Another observer, remembering him as ‘pale,’ added: ‘While he seemed aloof, his passion for work was such that he could not refuse a favour, an undertaking or a plea.’ Belcourt was a dour, private man. ‘He was ailing all his life,’ remembered his friend Dandurand, ‘haemorrhages laid him low, and often he faced death.’ Another friend said he had ‘a great “team spirit” and the virtues of humility, of cooperation and of confidence that it entails.’16

Impeccably bilingual, Belcourt was acutely sensitive to the English–French dichotomy in Canada and the Irish–French schism in Catholicism. He first married the daughter of an Irish Catholic, then the daughter of a Protestant, but he ‘had been compelled to insist on the use of French at table, lest in the Ottawa milieu they [the family] should lose their mother-tongue.’17 In an article entitled ‘Canadian National Unity’ published in the Westminster in 1907, he complained that little progress had been made in ‘fostering a national spirit’ and argued that the ‘slow development in every branch of human industry, the tardy material progress, the consequent exodus of one-third of our population to the United States … were not calculated to awaken a vigorous Canadian patriotism.’ Yet he seemed optimistic about relations between religions in Canada: ‘The spirit and objective of Confederation can be summarized in two words: “cooperation and solidarity.”’18

He could be harshly critical. Canada’s politics, for instance, were a problem, Belcourt said, because the elite shirked the duties of citizenship and left ‘to the less enlightened classes the task of municipal and legislative representation and government.’ In many ways he was a traditional Liberal. ‘The best government is the one that governs least,’ he argued; ‘it would be a good thing to remind those gentlemen of the need for a greater individualism and of a greater spirit of private enterprise.’19

In terms of Canada’s presence in the British Empire or in international events Belcourt was something of an internationalist, like other Quebec political leaders such as Raoul Dandurand, Rodolphe Lemieux (Laurier’s able Quebec deputies), and, to a certain degree, even Sir Wilfrid himself. ‘Canada is the last hope of democracy,’ he said. ‘The eyes of the whole civilized world are upon Canada, and its attempt to create and maintain an ideal democratic polity will be watched with the keenest interest. Failure to rise to the opportunity will deserve and no doubt receive universal condemnation. Canada owes it to herself and to the world, and to the cause of democracy as well, and especially to her future generations, to assure in her land of “milk and honey” democracy’s ultimate triumph.’20

Together, they faced the wrath of Henri Bourassa, the grandson of Louis-Joseph Papineau, who since the Boer War had distinguished himself in pleading against Canadian involvement in British affairs and in favour of cutting the imperial tie. It would be difficult to exaggerate the vilification of Bourassa in English Canada during the war years, particularly as he sharpened his opposition to the war effort from the middle of 1915 on.21 He was denounced as a German spy, a traitor, and a criminal by some of the prominent men of his day. He often faced police harassment and threats to his life. Bourassa, nonetheless, never failed to speak in English Canada to make his views better known. His searing editorials on the empire and against Canadian imperialists in Le Devoir were collected in a series of pamphlets and books, many of them published for the English-speaking market.22

Inspired by Bourassa’s views, many have generalized Quebec’s attitude as ‘anti-imperialist and nationalist.’ A closer reading of the situation leads me to the conviction that there was a deeper and more meaningful ideology at play. Repeated appeals by the French-Canadian elite – politicians, bishops, business people, some union leaders, eminent journalists – to come to the aid of Catholics, of the French, or of the Belgians equally fell on deaf ears. French Canadians, for the most part, did not want to see their youth squandered in the muddy battlefields of Europe. ‘Isolationism,’ which has seldom been used to define a position in Canada23 and has been employed with so little precision even in the United States, can explain the position of most French Canadians towards the First World War. ‘Isolationism’ as one historian described it, ‘is an attitude, policy, doctrine, or position opposed to the commitment of American force outside the Western Hemisphere, except in the rarest and briefest instances. The essence of isolationism is refusal to commit force beyond hemispheric bounds, or absolute avoidance of overseas military alliances. Rejection of forceful commitments beyond the hemisphere is the point on which all have agreed.’24 This definition – easily applied to Quebec – could also be applied to many parts of Canada in the early twentieth century.

Isolationism in Quebec and in French Canada was tested during the Boer War and in the Naval Bill debates of 1909–10, but it most clearly emerged during the First World War. Bourassa’s version struck a chord in many levels of French Canada’s leadership and in the wider population, but it would be a mistake to argue that he applied the concepts to French Canada on his own. In fact, it was espoused by a wide variety of people who had different reasons for arguing that Canada should not involve itself in defending the Triple Entente powers. In the United States, Senator Robert A. Taft famously commented that the label ‘isolationist’ was given to ‘anyone who opposed the policy of the moment.’ The same could be said of Quebec isolationists, who, like their American cousins, continually denied that they were isolationists.25

The isolationist debate in the United States was very similar to the Quebec experience in other ways. The Chicago Tribune, for example, proudly referred to isolationists as ‘nationalists.’ In both cases, there was a factor of geographic and demographic concentration. In the United States, isolationism was explained by pointing to ethnic, geographic, and economic realities and was found to be prevalent in German and Irish minorities scattered in the United States.26 Voters in the mid-west, notably German- and Scandinavian-American Lutherans, were noticeably isolationist and their influence was felt in Washington.27 Although rooted deeply in the mid-west, isolationists such as Senators Robert La Follette of Wisconsin and George W. Norris of Nebraska proved sufficiently influential to divide many political parties and help to delay American entry in the war until 1917. They would argue that to involve the United States in the European war would imperil democracy at home and would thus be a denial of the very raison d’être of the United States. ‘As Americans, they [French Canadians] deny any close relationship with either France or Europe,’ André Siegfried, the noted French sociologist, pointedly observed in the 1930s.28

Belcourt, holding a view that rejected isolationism and allowed for Canadian involvement in the world, sincerely attempted to justify a presence in a war. Against the likes of Bourassa, he would argue that French Canadians ‘never sought or even contemplated the severance of the British tie.’ For Belcourt, the link to Britain and its political traditions was central to the Canadian compact and thus worthy of defence. Belcourt would insist that Canadians needed the protection of the British Crown and should defend it, militarily if need be, until a reasonable accommodation could be arranged between English- and French-speaking peoples in Canada. The battle over Regulation 17 proved the truth of this assertion.

The debates on this issue had been burning for over two years by the time war was declared against the Kaiser.29 Sensing the growing importance of the Franco-Ontarian community, and urged by Irish Catholics, the Government of Ontario asked its chief inspector of public and separate schools to investigate the quality of education in the Ottawa valley in 1908. He reported that the quality of teaching in the French-speaking schools (known as ‘bilingual schools’ or ‘English-French schools’ because English had a major presence) was poor. The reaction among francophones in the Ottawa region was swift. On 24 January 1909, 100 people from Ottawa met and supported idea of a conference that could unite disparate forces.30 The event took place a year later (both Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier and Leader of the Opposition Robert Borden attended) and a new organization was created, the Association Canadienne-française d’éducation de l’Ontario (ACFEO). Napoléon Belcourt was elected the first president in January 1910. He would occupy his position for two years, until a member of the Conservative Party would be chosen in order to curry favour with governments both in Ontario and in Ottawa. At the time Belcourt assumed his post, French Canadians constituted fully 8 per cent of the population of Ontario, up from 2 per cent at Confederation. According to the census of 1911, there were 202,422 francophones in the province. In 1909, however, the ecclesiastical census of the province reported 247,000 French Canadians. The net effect was that 250,000 was the figure often cited in newspapers and speeches.31

The ACFEO lost little time in bringing to light the weakness of Franco-Ontarian representation in the political and judicial arena and submitted to Prime Minister Laurier a long list of inequities, in terms of judges named to the bench and senators, in comparison with Irish Catholics in Ontario (who were fewer – between 175,000 and 200,000), or the English minority in Quebec.32 The petitioners argued that the weak representation constituted a ‘grave injustice.’ They maintained early that, because of their weak representation in Parliament, they had to be compensated with effective representation in the courts in order to protect their rights.

Events proved them prescient. In March 1911 Howard Ferguson, the future Ontario minister of education and premier, introduced in the legislature a motion asserting that ‘no language other than English should be used as a medium of instruction’ in any school in Ontario.33 Acting on the report of its chief inspector, the Ontario government adopted Regulation 17 in June 1912 (it would be amended in 1913 and made law in 1915).34 Essentially, it outlawed the creation of new bilingual schools, limited teaching in the French language to the first two years of school, imposed the teaching of English from the very first grade, required that all teachers be qualified to teach in English, and limited the use of French as a language of communication. To enforce these new regulations, the government announced that the schools would be monitored by both a French-speaking and an English-speaking superintendent. ‘Circular of Instructions, 17’ was, according to Premier James Whitney, designed to improve the instruction in French-language schools. It quickly assumed a far greater importance than a routine administrative standard. Francophones saw nothing less than the hand of state-ordered assimilation.35

Regulation 17 was enforced by a rule that any school that failed to comply would forfeit support from public funds and that its teachers would be liable to suspension or cancellation of their certificates. From the beginning, the Ottawa Separate School Board, two-thirds of whose trustees were francophones, refused to enforce Regulation 17. The first appeals were political. With weak representation in the Ontario cabinet, leaders of the ACFEO sought help from Ottawa. The new prime minister, Robert Borden, was asked to invoke federal powers to suppress the Ontario law. He refused, but in the fall of 1912 Borden wrote to Whitney to express his concerns. Whitney responded that this issue came under provincial jurisdiction.36 In the face of such obstinacy, Franco-Ontarians organized themselves, helped in no small part by funding received from Quebec sources. In 1913 they launched Le Droit, a French-language daily, and it proved an effective mouthpiece. It supported the Ottawa Separate School Board and cemented support for its actions as it continued to refuse to comply with the hated language rules. It is worth noting that the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste in Montreal, led by Olivar Asselin, raised $12,600 (over $200,000 in today’s currency) for the ACFEO through their « Le sou de la pensée française » campaign. In total, the ACFEO received $15,400 (over $244,000 in today’s currency) from Quebec sources between 1910 and 1913.37

Belcourt, like others, hoped that the provincial elections in Ontario in June 1914 might have helped to cool the situation in Ontario. The governing Conservative Party, still led by Whitney, pledged full endorsement of Regulation 17, while the Liberals, led by Newton Rowell, remained surprisingly vague and non-committal.38 The Conservative Party was returned to power, but the Franco-Ontarian Tories who had supported the Regulations were defeated.

A few weeks after the election, the Ottawa Separate School Board closed its schools, asserting that it could no longer pay its teachers without the support of the provincial government. By September 1914, with the war in Europe now fully engaged and politicians of all stripes in Canada pledging their support to the Triple Entente, 8,000 students in Ottawa were without teachers. Led by Samuel Genest, the French majority sought a city by-law allowing it to issue debentures to raise money for new schools to be operated independently of the Department of Education’s rulings. R. Mackell, one of the minority school board members, asked for an injunction against the board’s decision to close the schools to prevent it from borrowing or paying staff while refusing to comply with Regulation 17. The Ontario Supreme Court ordered the board to reopen its doors and to employ only qualified teachers. Premier Whitney died a few days later and was replaced by William Hearst, who in that October placed the Ottawa Separate School Board under trusteeship. Although the issue had been festering since 1912, there was now a legal point on which Franco-Ontarians could seek redress in the courts, since the political apparatus had completely failed to respond to their demands for justice.

Belcourt leaped at the opportunity to use this case as a platform to argue against the root cause of the action, Regulation 17. Representing the Ottawa Separate School Board, he launched a suit against Mackell and argued the case in early November 1914 before Mr Justice Lennox, an individual Belcourt later described as ‘an ignorant and narrow-minded fanatic.’39 The timing could hardly have been worse for the war effort. English Canada was demanding a national effort to support the British Empire while at the same time denying francophones in Ontario the right to an education in their own language. In late November 1914 the Ontario Supreme Court ruled in favour of Mackell, finding the board guilty of disobeying the laws of the province. Henri Bourassa denounced the ‘Prussians of Ontario.’ Soon the Quebec government, which had kept quiet about the sister province’s affairs, adopted a legislative resolution on 13 January 1915 in which it unanimously deplored the controversy and asserted that the legislators of Ontario were deficient in their understanding and application of traditional British principles.

Belcourt appealed the Lennox decision in the winter of 1915 to the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of Ontario. Chief Justice Clute had listened to the crown’s arguments for two days, and Belcourt was looking forward to pleading in favour of recovering the monies of the Ottawa board taken by the commission and not returned. Belcourt had not stood before the court for ten minutes before Mr Justice Clute said, ‘in a bare-faced exhibition of bigotry and boorishness,’ that no argument could be made that would ‘impress him.’ Belcourt was allowed to continue only when another judge protested, saying that he was very anxious to hear the argument.40 Not surprisingly, the Appellate Court found against the Ottawa Separate School Board in July 1915.

Before the courts, as much as before the Senate or before the public, Belcourt argued against the letter and the spirit of the law on three fronts, and his positions inspired a similar line of argument across the country. First, he maintained that Regulation 17 was effectively removing rights already acquired in the school regulations devised in Canada West by Egerton Ryerson and supported by Oliver Mowat.41 He pointedly did not use the argument that French was guaranteed in the constitution because there simply was no provision for it. Technically, he argued, the separate school law, unlike the public schools law, did not prescribe the use of the English language, indicating that the framers of the legislation had no intention of ever limiting the use of French. He argued, moreover, that Regulation 17 was inconsistent with the requirements of section 93 of the British North America (BNA) Act, which granted the provinces the right to legislate exclusively in the area of education, providing that the rights of denominational schools were not affected. In essence, he maintained that learning in French in Ontario was a right that ‘once granted, is not susceptible of being withdrawn. If withdrawn, as is clearly sought to be done by Regulation 17, the Courts in their ordinary inherent jurisdiction have the power and duty to determine that Regulation 17 is ultra vires of the Legislature.’ Outside the court, and not without some bitterness, Belcourt blamed the negotiators of the 1867 pact for the predicament of Franco-Ontarians. ‘I always believed that the leaders of Lower Canada had completely lost sight and prudence in not demanding a clear and explicit recognition of our religious and linguistic rights,’ he told Henri Bourassa.42

Second, he argued that the usage of French, and by implication the right to be instructed in it, constituted a natural right. In court, he pointed out that Regulation 17 ‘constitutes the only attempt ever made in the British Empire to deprive British subjects of the use of their mother tongue.’43 Outside the court, he was more eloquent: ‘Far from affecting our duty or hiding our devotion to the British Crown and British institutions,’ he argued, ‘the free use of our mother tongue, with the recognition of our laws and our institutions, has been the pure source whence we drew the will, the courage, and the valour which enabled us more than once to save this country for the Empire. Had the French language not been made equal before the law in the past, I would not hesitate to say that to-day it would be an act of simple justice, and of profound political wisdom to recognize it as such.’44

Belcourt’s argument had a more legalistic aspect on the issue of taxpayers’ rights. He claimed that the taxpayers who funded the separate school system had a right ‘similar to other rights of property’ to determine how funds would be spent. ‘Regulation 17,’ he asserted, violated ‘natural law and natural justice’ because it sought to take away the right to have one’s own money, paid in by way of school taxes, applied in accordance with one’s own wishes. While Belcourt was willing to recognize that the Department of Education did have rights to oversee the schooling taking place in the province, he argued that it was a shared duty, the result of a shared funding. Stated otherwise, the government could not deprive the ratepayers of the use or control of the taxes contributed by them to their school boards for educational purposes.45 Outside the court, Belcourt called into question the unequal funding of separate and public schools, particularly the diversion of taxes paid by semi-public, industrial, financial, and commercial corporations to public schools, not to separate schools. Belcourt, utterly beside himself, was defiant:

And, as if this weren’t enough, it is now threatened that if the French-speaking Canadians in Ontario persist – and there can be no doubt that they will – in their present attitude that the French language shall, in certain well defined parts of the province, be the vehicle of instruction, the whole of their school tax contributions will be diverted to the use of the public schools, and they shall, furthermore, be deprived of the schools built and paid for and supported out of their own moneys. The majority may possibly – though it is very doubtful – so ordain; but who will say that such would not constitute a flagrant and intolerable denial of justice? … Not only have the educational authorities in that province passed sentence of death upon the French language in the schools, but they have committed the execution of this sentence to the bilingual teachers who will be required to strangle French speech and French thought. And to make sure that death will ensue, the government has appointed supervising inspectors who know nothing of the French language to supervise the gruesome task. Why not suppress the name as well as the thing itself?46

Belcourt’s third key argument was that Regulation 17 was, ‘educationally speaking, an absurdity.’ He described the educational reach of the regulation as ‘manifestly a pedagogical heresy’ and ‘utter nonsense,’ in that students would have to be taught subjects in a language that they could not understand. Outside the court, he protested that that Franco-Ontarians hardly deserved such treatment. Education was a key promise for a better future, and government efforts to stifle the learning initiative were counterproductive. Franco-Ontarians were aiding the development and prosperity of Ontario; they lived in peace and harmony with their neighbours and did not deserve discriminatory practices.47

Every court of the Province of Ontario rejected Belcourt’s arguments. As news of court decisions unfailingly disappointed and the obstinacy of Queen’s Park proved unshakable, the schools in the shadow of Parliament Hill in Ottawa rapidly became ethnic battlegrounds. Father Charles Charlebois, curé of Sainte-Famille parish and the guiding spirit of the resistance in Ottawa, considered that perhaps having a friend inside the governing Tory party might be an asset to the movement. He sent a long, hand-written letter to Senator Phillippe Landry in January 1915, asking him to assume the presidency of the ACFEO. Landry, an old ultramontane Tory and speaker of the Senate, accepted the offer a month later and promptly drafted a letter to the Ontario premier that again linked the war and Ontario’s educational battle: ‘Should not the entente cordiale which today united the English and the French on the battlefields of Europe be able to bring together in our own country the descendants of those two great nations?’48 Hearst never responded, leaving the courts to answer.

The controversy caught fire in March 1915, when the Ontario government effectively declared 190 schools in the province ineligible for grants. It then secured passage of a bill empowering it to set up a commission to take over the duties of the Ottawa Separate School Board; in July it abolished the Ottawa Separate School Commission and named a three-person commission (one of whom would be French speaking) to manage the schools. Despite Sir Wilfrid Laurier’s urgings, the Liberal opposition led by Rowell supported the bill. Suddenly, the issue was spilling far beyond the boundaries of Ontario’s Queen’s Park and onto Parliament Hill, Quebec, and Rome.

In June 1915 bishops and archbishops in French Canada sent a petition to Pope Benedict XV, telling him that the French language was a ‘rampart’ against the mixed marriages deplored by the Holy See. Their argument was that the battle against Orangeism in Ontario had to be successful; otherwise, the Protestant forces would exert themselves against Catholicism in other provinces. The petition also asked him to put pressure on the Canadian political system, because under Regulation 17 Catholic schools would fall within the inspectorate of Protestants, which ‘places them at the mercy of an enemy of their traditions and beliefs.’49 Mgr Latulippe, the Bishop of Haileybury, travelled to Rome to explain the situation and returned in October 1915. At that point, Phillippe Landry urged Cardinal Bégin of Quebec City to go to Rome to direct ‘the battle that must begin before the roman congregations … Only your Éminence can bring us victory.’50

As the school year began in September 1915, two teachers (the Desloges sisters) were fired. In protest, they occupied the Guigues School and declared that they were no longer working for the Separate School Board. Defended in the streets by angry parents, they had created their own institution on board property and refused the inspection of the government. When in the same fall the Supreme Court of Ontario sustained the validity of Regulation 17, Belcourt decided to take the case to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London. ‘The French and Catholic minority in Canada has better chances of obtaining justice from the privy council than it does from the Supreme Court,’ he told his colleague Aimé Geoffrion. ‘Having seen these English speaking judges in the Supreme Court up close for over 25 years, I can say that all of them, almost without exception, held views that were passably narrow and an invincible prejudice against us. I can’t help having more confidence for our cause in front of the Privy Council than the Supreme Court when it comes to minority rights.’51 Belcourt hoped for a political solution; the procedural delays created by Government of Ontario lawyers in Mackell v. Trustees showed that a quick solution was not forthcoming.52

The decision of the Ontario Supreme Court galvanized Franco-Ontarian efforts. Belcourt, never content to limit his presence to the courtroom, also took to the streets. In the winter of 1916 he started a campaign to encourage Ottawa taxpayers not to pay their school taxes. His efforts were supported by a strike of bilingual teachers53 and by a march of 5,000 French Canadians to Parliament Hill, asking for federal intervention. A handful of representatives met with Prime Minister Borden, but without success.54 At the same time, the Quebec legislature passed a bill authorizing municipalities in Quebec to make contributions towards the financing of ‘bilingual agitation’ in Ontario. Wilfrid Laurier, who had been fairly quiet on the issue, grew indignant. Not surprisingly, he invoked many of the arguments Belcourt had rehearsed since the beginning of the crisis. He vented his spleen on Stewart Lyon, editor of the putatively Liberal Globe, and accused him of not living up to the principles of Blake and Mowat. ‘The whole situation is one which is very clear and which can be easily settled upon the lines of Liberalism, as it was forty years ago by the Mowat government,’ he told Lyon; ‘it was then agreed, and everybody accepted, that every child in Ontario should receive an English education but that parents of French origin should also have the right, in addition, to have their children taught in their own language. Who can object to this? Is there a Liberal who is not ready to stand for this reasonable position? I confess to you that I am disturbed by the present attitude of your paper. I am not disposed for my part to yield neither to the extremists of Nationalism nor to the extremists of Toryism.’55 Laurier also dissected the issue in what he called a ‘too prolonged correspondence’ with Newton Rowell, the Ontario Liberal leader, in the spring of 1916. Laurier was despondent: ‘Henceforth, the Orange doctrine is to prevail – that the English language only is to be taught in the schools. That seems to me absolutely tyrannical.’ By mid-May, Laurier had concluded that the ‘line of cleavage’ separating him and Rowell was now ‘final and beyond redemption.’ He told Rowell, ‘I write with a heavy heart. The party has not advanced; it has sorely retrograded, abandoning position after position before the heavy onslaughts of Toryism.’56

Events proved even harder to bear for Laurier that spring, when the Liberal government in Manitoba rescinded the clause in the School Act that gave the parents of ten children the right to request bilingual instruction.

It would take time for the case to make its way to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London, and action was required immediately. The Liberals, led by Laurier himself, pressed Borden to work against the Ontario school regulations. Laurier drafted a motion, along with Rodolphe Lemieux, Laurent-Olivier David, and Paul-Emile Lamarche, a nationalist MP who was rapidly developing ties with the Laurier camp. On 9 May 1916 Ernest Lapointe tabled the motion in the Commons, resolving ‘that this house, especially at this time of universal sacrifice and anxiety, when all energies should be concentrated on winning the war, while fully recognizing the principle for provincial rights and the necessity of every child being given a thorough English education, respectfully suggest to the Legislative Assembly of Ontario the wisdom of making it clear that the privilege for the children of French parentage being taught in their mother tongue be not interfered with.’57 The Lapointe motion, which was clear in not requesting that the federal government use its powers of disallowance, was debated, but it was rejected by 107 votes to 60. Although seven French-speaking members elected under the Conservative-Nationalist banner voted in favour, the French-speaking ministers in Borden’s cabinet voted against the motion, claiming that the symbolism of castigating provincial legislation was ruinous to confederation. The vote was predetermined but could only depress Laurier further: eleven western members and one Ontario member of his own caucus voted against the Lapointe resolution.

Ten days later the French-speaking ministers in Borden’s cabinet, led by Esioff-Léon Patenaude, drafted a memorandum asking that the federal government intervene before the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in Great Britain and threatened to resign if no action was taken. Borden refused to acquiesce to the demand.58 In protest, the now seventy-year-old Conservative Senator Philippe Landry quit the speaker’s chair of the Senate in order to dedicate himself entirely to the Franco-Ontarian battle, and he campaigned across Quebec to raise awareness of what was happening in Ontario. Landry drafted a revealing aide-mémoire of arguments regarding the struggle against Regulation 17, part of which concerned ‘national honour’: ‘A people that finds itself faced with an unjust and merciless aggressor has the honorable duty to resist to the last. This is our case in Ontario. We are in the same situation as the Belgians and the French. A people owe it to its honour to reject national insults. Regulation 17 holds many screaming ones: a) It places our language below that of German. b) It places us as stewards of the state like simple savages with its double inspectorate. The struggle has so long been engaged that we cannot abandon it without national disgrace. We have burned our bridges.’59 Without a doubt, his greatest success occurred when he accompanied Belcourt to a rally of 10,000 people at the Parc Lafontaine in Montreal on 19 June 1916 and gave a thundering speech denouncing the school regulations. Belcourt then left for Europe, to argue the case before the Privy Council and to visit the front.

In London, Belcourt repeated many of the same arguments he had used in the past, but added a few extra notions. He held that section 133 of the BNA Act implied the right to teach French where francophones requested it. ‘I presented this argument to the judicial council by saying that in order to fully and freely exercise their rights as citizens as conferred by the Confederation Act, as much to defend and protect himself, his belongings and his freedom, and also to fulfill his fair share of duties, every citizen must have the right to use his mother tongue,’ he told Bourassa. ‘That is why it is necessary to recognize the right to French-language education for those whose mother tongue is French. Section 133, by decreeing that both English and French are official languages, implies that there is a right to education in the French tongue.’60 Belcourt went further. He argued that Regulation 17 had caused real harm to the French Catholic minority in Ontario in terms of religious freedom. He argued that the objective of section 93 was to perpetuate religious rights legally established at the time of Confederation. In Ontario, laws passed in 1863 authorized the building of Catholic schools and ensured rights to taxes in order to maintain them. By removing the right to learn in French, Regulation 17 was in effect denying the right to a religious education. Hopeful that the justice that had eluded Franco-Ontarians at home could be found in the Parliament of the mother country, Belcourt ended his argument before the Privy Council and proceeded to a fact-finding tour of the Western Front (see below).

While the battle of the Somme raged, Franco-Ontarians awaited the judgment of the high London tribunal, as well as some sort of pronouncement from Rome. The Holy See responded on 27 October 1916. In his Encyclical Letter Benedict XV refused to take sides between the Irish and the French-speaking Catholics of Ontario and instead limited its verdict to a call for calm and unity. Two weeks later, the Privy Council in London rendered its decision. It found Regulation 17 intra vires, but declared ultra vires the takeover of the Ottawa Separate School Board. For Belcourt, there was finally some vindication. By finding that the provincial government had no right to take over schools, the Privy Council effectively gave the school board the tools to continue its fight. ‘In other words,’ he told Henri Bourassa, ‘if the government had been able to put its hand on our schools and control them, it also had the right to impose Regulation 17 … The Privy Council declared ultra vires the takeover of our schools. Otherwise, I must repeat, the minority would have been rendered impotent.’61

The Privy Council and pontifical decisions effectively ended the legal fight over Regulation 17, but it did not take away any of the bitterness. Indeed, the Hearst government in Ontario passed new legislation to strike down school boards that did not comply with the government and insisted that new settlers in Northern Ontario sign agreements not to educate their children in French. As Belcourt noted, the Ontario government ‘did not try at any time to settle the question … [and] did not want the question to be settled,’ simply because it perceived it as an issue on which it could hold onto power.62 The greater significance of Regulation 17, however, was its effect on French Canada at large. The monthly magazine L’Action Française was launched in 1917; its primary focus would be language rights in Canada. Belcourt and Landry had also alerted all the francophone communities in the land to their difficulties, and their mailboxes were consistently replenished with encouraging correspondence and petitions from across the country.

The high points in the battle over Regulation 17 paralleled almost exactly the cruellest losses of life on the battlefields of Europe. As tempers flared in Canada over the rights of citizenship of the French minority, the mounting casualties intensified the cry for more support of the war effort. The fight between English and French now would take place over the enlistment of soldiers for the war effort, a battle that would further bruise an already demoralized French-Canadian population.

Did French Canadians refuse to fight? Yes, and no. Although no records of language spoken were kept by the military, it is commonly asserted that roughly 62,000 French Canadians enlisted in some way in the war effort (about 620,000 men in Canada were enlisted in total). By the end of the war, it is estimated that there were 35,000 French-speaking men from all parts of Canada in uniform. Although French-speaking soldiers would be deployed in other units (one historian estimated that 62 per cent of Quebec’s infantry volunteers joined English-speaking battalions),63 fourteen explicitly French-Canadian battalions were created during the war (identified on their cap badge as Bataillon Canadien-français or Bataillon Outremer): eleven from Quebec, one from Alberta (the 233ième Nord-Ouest), one from New Brunswick (the 165ième Acadien), and one from eastern Ontario (the 230ième voltigeurs Canadiensfrançais).64 Still, only three of the fourteen French-speaking battalions, the 22nd, 41st, and 69th, were recruited to strength (1,100 men). Many soldiers were decorated for their valour. Clearly, French Canadians fought in the war.

Placed in perspective (about 30 per cent of the Canadian population was French Canadian), however, it is evident that the effort was relatively light. On a province-by-province basis, Quebec ranked at the bottom by every measure. Far fewer eligible men (15.3 per cent) in Quebec volunteered for the war effort than the Canadian average (31.4 per cent).65 It must also be remembered that 18 per cent of Quebec’s population at that time was English speaking; Quebec figures therefore must not be interpreted as solely ‘French speaking.’ Conscription eventually had to be used to increase enlistments, and Quebec supplied more conscripts as part of its contribution (34.1 per cent) than the Canadian average (20.5 per cent). In terms of men who actually served overseas, Quebec had the lowest ranking at 14.4 per cent (the next lowest was Saskatchewan at 21 per cent). By one calculation, French-Canadian participation was ‘the lowest rate in the white Empire.’66

If isolationism was widely held in French Canada, it did have its limits. It was, as in the United States, an ‘ideology under stress.’67 The political leadership in Quebec never argued against the war effort and did support it in many ways. The Catholic Church, at the height of its influence in Quebec, supported war against Germany and its allies, but there is little doubt that there was dissension among the bishops and among local priests, close to the people, who were not partisans of the call for enlistment.68

Indeed, many French Canadians spoke in support of Great Britain and France in the late summer and early fall of 1914.69 Parliament met in a special session on 18 August, and all the bills dealing with the war were passed without a dissenting vote.70 Henri Bourassa’s first editorial in Le Devoir of 29 August defined the nationaliste position. On 8 September he asserted that aid to the empire was as critical as it was natural.71 Church pronouncements in favour of war first appeared on 23 September 1914. At the same time, Médéric Martin, mayor of Montreal, announced that employees of the city mobilized by Belgium or France would continue to receive their salaries. The Montreal chapter of the Canadian Patriotic Fund was launched with panache with Mgr Bruchési, the archbishop of Montreal, and Mayor Martin present. The efforts were directed by the English-speaking elites of Montreal, but the fund’s direction and management were held as exemplary of an ‘entente cordiale’ in September 1914.72

There were surprisingly few elected politicians who spoke out against enlistment. Rodolphe Lemieux, for example, was unforgiving in his intense criticism of Sam Hughes, but he supported the war effort and encouraged enlistment nonetheless. Indeed, his own son would soon enlist.73 Senator Belcourt was no exception in his eloquence. ‘Enlist, my young compatriots!’ he urged a large crowd assembled in Montreal’s Sohmer Park in October 1914. ‘If we have to send two or five or ten French-Canadian regiments, we’ll know how to find them,’ he continued. ‘Is it not because the sacred cause of freedom for all is in imminent peril that the real civilization is threatened to its very root? I know that you do not love war any more than I do. We Canadians are a pacifist race. For over one hundred years we have lived in complete peace and we appreciate its worth to the degree where we will make all the necessary sacrifices to ensure its survival here and its return elsewhere. Our pacifist spirit must not compel us to become doctrinaire pacifists.’ His argument was liberal. Canada had to fight to affirm the right to live, to defend liberty, honour, the solidarity of civilized peoples, to avenge the outrages and the national insults, and to protect the weak from the brute: ‘Canada, no more than other civilized nations, has no right to remain a silent witness to the terrible and barbaric drama that is being played out on the bloodied and devastated fields of Belgium and France. England may be next; perhaps even Canada. Hence our duty is clear. It is urgent, it is immediate, and it will only be accomplished when we will have exhausted – if we must – all our resources of men and money … French Canadians are not going to negotiate their share of sacrifices; they never had, they never will. Their devotion to the empire is as total as every resource at their disposal. It is clear now that the war will be long and that it will bring incalculable and terrible losses and sacrifices.’74

Belcourt’s assurance that French Canada would not ‘negotiate’ its participation was exaggerated. ‘The pity of it is,’ the writer Elizabeth Armstrong would write twenty-five years later, ‘that the government never took full advantage of this French Canadian ardour of 1914.’75 In the 1st Division that went to France, only one company was French speaking. Of the 36,267 men who formed the first contingent of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1,245 (3.4 per cent) were listed as ‘French-Canadian.’76 The only senior French-Canadian officer was Lieutenant-Colonel H.A. Panet of the Royal Canadian Horse Artillery, a division that proved its valour at the second battle of Ypres, barely a few weeks after landing in Europe.

The weak French-Canadian presence could easily be explained by the reality that the military life was not seen as particularly attractive or worth pursuing. In 1912 only 27 of a total of 254 officers of the Canadian army were French Canadian.77 Given this tradition, the early news on enlistment was not surprising and tested the most entrepreneurial spirits. Arthur Mignault, a Montreal doctor, singularly rose to the challenge and did so brilliantly.78 He put up $50,000 ($793,836 in today’s currency) to raise a regiment, soon called the Royal 22nd (or, as they would be nicknamed in English, the Van Doos). It would take Mignault and others almost six months to bring the corps to capacity (many recruits decided to desert), so that it could make the trip overseas, but he did attract honourable men, not the least of whom were Georges Vanier and Thomas Tremblay. Mignault also established a French-Canadian hospital, General Hospital No. 8, at St-Cloud, near Paris.

On the whole, however, Ottawa’s recruitment policy of relying on local initiative to create military units while keeping central control on deployment did not work well in French Canada.79 Apart from Dr Mignault, few wealthy or entrepreneurial French Canadians showed an inclination to find recruits, and civilian recruitment associations that were effective in English Canada simply did not work effectively in Quebec or in French Canada generally.80 J.L. Granatstein and J.M. Hitsman have demonstrated that, in terms of administrative designs, the Canadian militia was ‘structured to be unattractive to French Canadians.’81 Sam Hughes and his lieutenants consistently proved insensitive to the need for ensuring some form of homogeneity within ranks. This negligence had multiple effects. First, it clearly discouraged enlistment. What point could there be in joining the ranks with a few neighbourhood chums when chances were likely that one would be thrown into battle with people who did not share – or respect, it must be said – one’s language and culture? Hughes, and the politicians in cabinet he reported to, simply were blind to the racialism of their own society, a concept that was hardly foreign to them, since it extended into the burgeoning world of professional hockey. Indeed, four years before the war started, a rule had been adopted in order to guarantee a team of recognizably French-Canadian players: no National Hockey Association club could hire a French-Canadian player unless the Canadien had given its approval. In 1912 the practice was relaxed somewhat so as to allow each team a complement of two French-Canadian players, while the Canadien was allowed two English-Canadian players. Surely, Hughes and his advisers could have absorbed a lesson on how French Canadians prized recognizably francophone undertakings.82

Other efforts to mount regiments tell a story of frustration, incompetence, and negligence. The second attempt to form a regiment of French Canadians, the 42nd, failed quickly. The 41st Battalion was too beset by corrupt and incompetent leadership to be sent abroad.83 The 57th Battalion also collapsed and most of its soldiers were transferred to the hapless 41st or to the 22nd. Efforts to raise the 69th Battalion to capacity failed but did furnish the 22nd with more troops. The 167th was raised to capacity but was squandered by the incompetence of its leader, Colonel Onésime Readman. The 206th, led by a close friend of the Tory government, Tancrède Pagnuelo, would become an even worse embarrassment. The 165th Battalion, which was raised in Acadia, was dissolved upon its arrival in England, and its soldiers were scattered in English battalions. Against all odds, in the poisoned atmosphere of the winter of 1916 a battalion of Franco-Ontarians was created in eastern Ontario, but it, too, would serve only to replenish depleted units. Efforts at enlistment failed generally and, as Desmond Morton has observed, efforts to recruit suitable officers did no better.84 In the end, although thirteen distinctively French-Canadian battalions had been created (most not near half capacity) by the summer of 1916, the military had clearly failed to mount an effective recruitment campaign.

There were fine opportunities. The fiery nationaliste and francophile Olivar Asselin, for example, initiated the 163rd battalion at the end of November 1915.85 It was brought to battle strength by May 1916, only to be sent to Bermuda. It finally reached Europe in November 1916, but there was broken up to provide reinforcements. Asselin would serve briefly as a platoon commander in the 22nd, but he was then redeployed to reinforce an English-speaking unit. Asselin’s abilities were simply squandered. The management of recruitment by Ottawa consistently undermined efforts on the ground. The federal government’s inability to identify and capitalize on war heroes revealed an overwhelming indifference to propaganda needs. Olivar Asselin was one of the most recognizable figures in Quebec and a nationaliste who argued for participation. That his battalion was never used as a unit, but only exploited for reinforcements, was a colossal error.86

Ottawa’s insensitivity to the need to routinely create role models in French Canada resulted in an impressive list of screw-ups. Remarkably, three of the six French-Canadian officers in the French-speaking company of the legendary first CEF division that went to Europe would eventually become lieutenant colonels, yet in the assessment of one historian, ‘most were fated to return to Quebec for the humiliating struggle to recruit compatriots for the front.’87 Major general Oscar Pelletier, who commanded a great deal of respect, was placed in charge of an outlook post on the island of Anticosti. François-Louis Lessard, the only French-speaking general in the army and a personable character, was made inspector general of troops in eastern Canada.88 Colonel J.P. Landry, son of the senator and speaker of the Senate and the highest-ranking militia officer before the war, was finally given command of the 5th Brigade of the 2nd Division in 1915, but his commission was revoked. He was perhaps too inexperienced to lead men into battle, but the implication stung. ‘His father, Senator Philippe Landry, had taken command of the Franco-Ontarian resistance to Regulation 17,’ notes Desmond Morton. ‘Sam Hughes had struck back.’89 Not surprisingly, the dream of a French-Canadian brigade would never materialize.

The gripping story of French-Canadian courage in the trenches of Europe belonged to the 22nd Regiment. But even the 22nd, part of the 5th Infantry Brigade of the 2nd Division, was poorly used. Almost 5,000 men served in the 22nd Battalion, most of them volunteers. The average age of the soldiers was twenty-four and for the officers twenty-seven. More than 1,100 of them died; a few thousand more suffered injuries. It was a unit that had more than its share of morale problems, and, in the absence of a steady leadership during extended periods, discipline problems were grave. Five men in the 22nd were executed, the most by far of any battalion. Indeed, 28 per cent of soldiers executed by the Canadian army were French Canadian, clearly a disproportionate number.

The soul of the 22nd was Thomas Tremblay, who was second in command in March 1915 when the unit was sent to Europe. Georges Vanier (who would become the first French-Canadian governor general) called Tremblay ‘the greatest French Canadian soldier since Salaberry,’ a man who was ‘just and severe,’ but who ‘despised danger; his men knew – and you can’t trick a soldier – that he had no fear, eager to do himself what he asked of others.’90 The 22nd showed it could fight when Tremblay led them. In the first days of January 1916 Tremblay – not even thirty years old – assumed command of the unit. In that month, Vanier and four men destroyed a German nest in a daring mission. Tremblay would eventually lead a three-day drive at Courcelette (where every officer was injured or killed) and in the Regina Trench in the fall of that year. Earl Haig, the British field marshall, described the Courcelette battle as ‘the most effective blow yet delivered against the enemy by the British Army.’91 But the rewards for Tremblay’s courage were slight. When the 5th Brigade needed a new commander, Thomas Tremblay was overlooked, although he was more experienced and more decorated than the other candidate. He would eventually command, but only three months before the end of the war. Sadly, Tremblay would be forgotten by his countrymen.92

Ottawa proved unable or unwilling to use the stories of French-Canadian courage at the front to encourage enlistment. Two years into the war, the 22nd was still the only French-Canadian battalion at the front, since the 41st, the 57th, and the 69th had been broken up and dispersed as reinforcements in the ranks of the 22nd. In July 1916 officers of the 206th Battalion were blamed for serious disciplinary problems and were sent home. Given the abundance of bad news, the press and the politicians in English Canada were increasingly critical of the poor recruitment effort in French Canada. Rodolphe Lemieux responded in the House of Commons that, by his count, there were between 8,000 and 9,000 French Canadians in the ranks of the infantry battalions in Canada and overseas by the middle of 1916. When French Canadians in other branches of the service or in English-speaking units were included, it was calculated that approximately 12,000 francophones were active in the military.93

The bitterness and confusion around enlistment poisoned efforts to improve the situation. In the summer of 1916 Talbot Papineau took his cousin Henri Bourassa to task for discouraging enlistment in a series of published letters, but to little effect.94 Talbot Papineau himself would eventually die at the front. All the same, the noisy exchange revealed the tension of the situation. In November 1916 Arthur Mignault was asked to head a commission to reorganize the recruiting of French Canadians in Canada, but nothing substantive resulted.

Belcourt personally would discover the conditions of the front in the summer of 1916. After he made his arguments against Regulation 17 before the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, he joined a delegation of thirty-three parliamentary representatives from the British Empire on a fact-finding tour of the front. They were received and entertained by the king and queen, the president of the French Republic, and the prime ministers of Britain and France and members of their cabinets. He left with ‘impressions of the deepest kind which can never be forgotten or duplicated.’ He visited the French and British fronts: the Somme, Picardie, and the Grand Fleet in the North Sea. He saw Compiègne, Aisne, Préronne, and then Ypres. He met the 22nd and he was touched: ‘May I say here that never was I more proud of my French blood and that my compatriots were represented in the battle line, as they are in many other places, by such brave fellows that they were taking their full share of the sacrifices and would in good time be entitled to their share in the ultimate triumph.’ His description of the troops was positive: ‘Nowhere can you find a more robust and healthier looking lot of men and in better spirits, all conscious of the great task entrusted to them, individually and collectively, imbued with the calm resolve to give up their lives if necessary, for the sake of Canada, the Allies and democratic ideals.’ Belcourt’s rhetoric was again decidedly, if sentimentally, liberal: ‘the tie which so closely unites and binds the Allies is the bond of a common sentiment, of common ideas of right and justice … It is the struggle of might against right; it is the fate of democracy which is being decided on the battlefields of Europe. And to me it is quite inconceivable that it can be God’s will to allow democracy to perish, because the very faith which is common to all the allies and democracy itself, rests upon common ideas of equal liberty, of common brotherhood.’95

Belcourt did not hesitate to share his impressions upon his return to Canada. ‘I broke down and could not restrain the tears,’ he said; ‘my heart bled at the sight of such suffering and anguish and I uttered the most earnest prayer of my life that this horrible butchery, this devilish slaughter and carnage might then end. My pacifist instincts, my abhorrence of this ceaseless torrent of horrors got the better of my judgment and I prayed for peace, for immediate peace.’ Yet he did not hesitate to link his emotions with the need for Canada and the United States to end their isolationism:

I wholly fail to understand how anyone, with anything like an adequate conception of the rights of man, of human justice, of the solidarity of men and nations to another one, can fail to grasp the supreme duty of the hour, can hesitate to proffer whatever aid or assistance may be in his power, to help avenge an outraged humanity and destroy the colossal scourge of Prussian piracy and bloodshed, so long as so elaborately designed and prepared, so wickedly and brutally inflicted on innocent Belgium, Serbia and France.

…

Neutrality in certain parts of the world may be explainable, but I feel quite sure that there is a certain democratic nation which will ultimately be driven to the inevitable, if tardy, conviction that mere money making is after all but a very poor, indeed a very miserable compensation for the loss of national prestige, national honour, caused by neglecting or ignoring international modern solidarity, the solidarity of civilized mankind.96

Belcourt was proud to speak both English and French in Europe. The high point of the visit for him was the occasion of a speech he gave in Paris, in response to the welcoming words of the French president. Raoul Dandurand later recalled ‘They chose him as their spokesman at the Elysée, Paris, before the President of the French Republic, who has since remarked more than once that Senator Belcourt’s speech was one to be long remembered.’97 For Belcourt, it was remarkable that a speech in French was made, ‘on the soil of France, at the one and only real international function during the visit and at one of its most solemn and inspiring moments.’98

Belcourt left Europe as the battle entered its bloodiest phase in August 1916. As the war dragged into 1917, statistics painted a picture that only invited comparisons. Up to the end of April 1917 a total of 14,100 French Canadians had enlisted – 8,200 from Quebec, meaning that 42 per cent of enrolees came from outside Quebec. In comparison, according to Sessional Paper 143B, 125,245 native-born, English-speaking Canadians had enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, and 155,095 British subjects born outside Canada had also done so.99 In other words, less than 5.1 per cent of enlisted men were French speaking.

To force enlistment, the Borden government passed the Military Service Act on 24 July 1917, requiring all men between the ages of twenty and thirty-five without families to support to register. In Quebec, many hostile demonstrations erupted, but by Thanksgiving of that year the first conscripts were called to report, exemption tribunals were organized, and men were summoned for duty by mid-November. By the end of the year, 117,000 men from Quebec had reported and all but 2,000 asked to be excused from serving. Every student from Laval University appeared before the tribunal armed with a letter from his school asking that he be exempted.

It was in this heavy atmosphere of forced enlistment that the Union Government was created and that the long-delayed election of 17 December 1917 was held. In Quebec, the campaign would serve to show how unpopular the Borden government had become. Bourassa (a supporter of Borden in 1911) now endorsed the Laurier Liberals. Quebec was united as never before in its rejection of the war and the attitude of the Union Government towards Regulation 17. Quebec voted overwhelmingly (72 per cent) against the government; indeed, seventeen ridings were won by acclamation. Only three ridings, strongly anglophone, voted Union. In the Maritimes, as in Ontario, the Liberals lost many ridings but inevitably held those that had strong French-speaking populations. The verdict crystallized the reality of a clash between English and French and, increasingly, of French Canada’s isolation from the rest of the country. In the final days of the year, Joseph Francoeur tabled a motion in the Quebec legislature: ‘This house is of the opinion that the province of Quebec would be disposed to accept the breaking of the Confederation pact of 1867 if, in the other provinces, it is believed that she is an obstacle to the union, progress and development of Canada.’ The motion was debated in late January 1918 but was not voted on.

Conscription thus became commonplace in neighbourhoods and towns that had vehemently opposed it. When called to report during the winter of 1918, Quebeckers protested angrily, and protests came to a head in Quebec City during the Easter weekend at the end of March. Provoked by insensitive gestures and forced enlistments, leaderless and disorganized crowds sometimes 15,000 strong gathered in front of the recruitment office. In response, the military set up a barricade of sorts at the intersection of St-Vallier and St-Joseph Boulevards, and reinforcements from Toronto were brought in to secure the peace. Riots were finally squelched when five men were shot and killed. The shots that rang out in that wet, early spring only confirmed that the gulf that separated English and French Canadians seemed unbridgeable.100

Anti-conscription parade at Victoria Square, Montreal, Quebec, 24 May 1917 (National Archives of Canada, C6859)

As the German offensive in the summer of 1918 took its toll, more and more French-Canadian men were marched to war. In the end, 27,557 would be drafted (about 23 per cent of the conscripted corps).101 The news from the front hit hard among the Liberal leadership. Rodolphe Lemieux lost a son in late August 1918.102 Six months later, on 24 March 1919, he nonetheless introduced a motion for amnesty for conscientious objectors: ‘That, in the opinion of this House, amnesty should now be granted to religious conscientious objectors to military service,’ even though very few men claimed conscientious objector status in Quebec.103

Napoléon Belcourt would spend his post-war years (he died of a stroke on 7 August 1932) trying to harmonize the discordant voices in Canada’s politics. Like many Liberals, Belcourt was disillusioned by the war effort.104 After the disappointing decision of the Privy Council, the battle to save Ontario’s French-language schools would have to stay political, outside the courts. Belcourt was again named president of the ACFEO in 1921, a post he would hold until 1930. A war that many thought could unite French and English Canadians had proved everything to the contrary.105

From his unique perspective, Belcourt was worried that Quebec – already isolated from international events – was now isolating itself within Canada, and he dedicated much of the rest of his life to building bridges between English and French Canadians. He supported the Bonne entente movement’s attempt to find the common elements of Canada’s two founding peoples and thus to try to reconstruct the connections necessary for a healthy confederation, and through it he met English-Canadian intellectuals he would enlist in the crusade against Regulation 17. Leaders of the Bonne entente introduced him to C.B. Sissons, who would write an eloquent protest against the education laws of Ontario in 1917.106 In 1918, on the heels of the conscription crisis, William Henry Moore published The Clash! A Study of Nationalities.107 Belcourt, who considered it ‘a really marvellous book’ because it confirmed his view that English and French Canadians were growing dangerously apart, sent 200 copies to France and Britain with a personal letter to each recipient. Belcourt also worked with key Toronto intellectuals to found the Unity League.108 As he would boldly state a few years later, ‘French Canadian nationality is not fanciful dream or mere hope. It is a reality living and capable of indefinite survival…. French Canadians … have the right to expect and to receive the complete recognition and the treatment due to a full partner in good standing in the Confederation partnership.’109 He restated his argument:

The covenant or deed which gave life to the Canadian federation, and upon which it must now and ever depend, constitutes nothing more and nothing less than a partnership agreement, without limit of time … All the members of the national firm put all their respective assets and all their goodwill into common pool, to be administered for the advancement and prosperity of each and all, every one reserving to itself autonomous control over its own local concerns, with mutual guarantees, and under their protection of the King and Parliament of the United Kingdom. It is the traditional and universally recognised rule concerning all partnerships that partners shall render to one another from time to time a true and faithful account of the doings of the partnership. The application of the rule becomes especially necessary, or, at all events, very desirable, whenever anyone or more of the partners exhibit symptoms of disaffection or disappointment. It would be idle or worse for anyone in Canada to deny that for some time past such symptoms have been and are still here only too much in evidence.110

Belcourt never abandoned the crusade against Regulation 17 and continued to argue that the right to schooling was tied to the right of free speech. He was an active member of the Unity League and missed no opportunity to participate in the halting, if renewed, dialogue between English and French. As he told the Student Christian Movement Conference at Convocation Hall, University of Toronto, in late December 1922: ‘For more than a century and a half the French of Canada have tenaciously insisted upon and persisted in the maintenance and preservation of their religious beliefs and practices, their linguistic rights and privileges, their customs, habits and usages and traditions. They have accepted and loyally performed their obligations to the Crown and their duties of citizenship. They secured responsible Government for Canada and twice at least saved Canada for the Empire.’ Acknowledging that, in the sensitive post-war years, his message of reconciliation might be difficult to accept, Belcourt asked for an understanding of French Canadians: ‘Let us not forget that everyone individually contributes to the prosperity, solidarity and progress of the Dominion, that each is entitled to equal right and equal consideration, each owing allegiance to the whole. Our motto ought to be “All for each and each for all.” Canadian national unity is today the paramount need of Canada. We shall never obtain it, or preserve it unless we practice that which it has been my great privilege to, very inadequately but most sincerely and earnestly, preach.’111

Belcourt also worked closely with the Irish-Catholic leadership in Ontario to heal the wounds of Regulation 17.112 In his encouraged state, he considered that the resolution of the issue would play a critical role in bridging the chasm between Quebec and the rest of Canada. Upon Howard Ferguson’s accession to the premiership in 1924, he wrote to William Moore, ‘the Premier is responsible for Regulation 17; I have not lost hope that he will after all feel inclined to do justice.’113 Events would prove him right. Conceding that the Ontario government’s actions in education had been a total disaster, Howard Ferguson, the same man who had sharpened the claws of Regulation 17 in 1912, repealed the measure in 1927.

Belcourt also maintained a vibrant dialogue with the nationalistes in Quebec, who in turn on 24 May 1924 awarded him the only ‘Grand Prix d’Action française’ they would ever grant. A medal was struck in his honour, and it was dedicated as a recognition of ‘the most fecund and meritorious act in defense of the French soul in America.’ Belcourt attended the induction in the Parc Lafontaine with his family as well as his brothers and sisters and heard the Chanoine Groulx heap praise on him. In his typically modest way, Belcourt accepted the prize by acknowledging that ‘it is to the Ontario minority that your congratulations are principally addressed.’114 Armand Lavergne offered his congratulations and thanks comme Canadien a few days later from his office in Quebec City.

There were many images of French Canada during the Great War that would endure, many that would fade. People would remember tales of men hiding in the woods for fear of conscription; of Rodolphe Lemieux, losing his son at the front, comforted by Sir Wilfrid; the unbound courage of Georges Vanier; the passion of Henri Bourassa; the public service of Arthur Mignault; the brave leadership of Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Tremblay; ordinary soldiers like Private Paul-Adrien Lambert, who enlisted in the 22nd as quickly as he could and so honoured himself and his company in combat that he was awarded the most esteemed Distinguished Conduct Medal. There also were victims, such as Honoré Bergeron, a forty-eight-year-old card-carrying carpenter and father of six, killed in the streets of Old Quebec, not far from his home, for protesting conscription.