DOUGLAS MCCALLA

In this essay I come to the question of the war and the economy from the perspective of a research program that revisits the larger narrative of Canadian economic history. A theme of that larger project, which the war nicely illustrates, is the power of established stories and images, which dominate understanding long after research has called them deeply into question. Such stories are most clearly visible in surveys, introductory texts, and popular accounts, but are also the explicit or implicit context for much specialized research. Even criticism, by reaffirming the importance of familiar themes, can reinforce them. That suggests the need to retell the story on a different basis altogether.

An event as vast as the Great War had profound implications for every aspect of participating societies, their economies very much included. So it is no surprise that Kenneth Norrie, Douglas Owram, and Herbert Emery conclude the chapter on the war in their standard text in Canadian economic history by emphasizing that ‘the war brought important changes in the Canadian economy, changes that would last long beyond the war itself.’ Many of those changes are captured in the image of a wartime ‘boom economy’ – a period of ‘hectic prosperity’ and immense industrial development.1 During the war, Craig Brown and Ramsay Cook write, ‘Canadian industrial plants were vastly expanded and even then stretched to their limits’2 Summing up an era dominated by war, Pierre Berton writes, ‘The change was spectacular. In a half century [from 1899 to 1953], we were transformed from an agricultural nation … to an industrial economy with a bedrock of natural resources.’3

If industry is the most prominent theme, it is not the only one. The war has been understood to have had many economic consequences, including changing ‘a laissez-faire style of economic life … almost beyond recognition’;4 ‘accentuat[ing] the distinctiveness of the prairie region’ and its ‘lack of economic diversification’;5 developing ‘new technologies’ that were subsequently ‘applied to domestic uses’;6 ‘strengthening … economic links between Canada and the US’;7 ‘accelerat[ing] … the movement of people from rural areas to cities’;8 and significantly affecting many other patterns of work, notably for women. For example, in the book accompanying the television series, Canada: A People’s History, the authors write: ‘Tens of thousands of women had taken the place of men in factories, banks, and offices … they were the ones making the economy work and manufacturing the weapons and munitions.’9

The war’s economic importance is reinforced because it is a historical dividing line, a turning point around which our entire narrative is organized. Many specialized studies begin or end with it, and it is a common break point in the internal structures of works that span it.10 Many of the latter include passages such as the following, from Canadian Women: A History: ‘By the end of World War I a full-blown industrial society had emerged.’11 Such phrasing seems to make the war important in Canadian industrial development, although in the authors’ larger discussion it is recognized that the rhythm and chronology of industrialization actually had little to do with the war.

There have been challenges to this dominant impression, notably by Michael Bliss. His work on wartime munitions production underpins most textbook discussions of the war economy, yet in his own survey of business history, Northern Enterprise, he comments only that ‘in some ways the war was good for some kinds of business.’12 Similarly, in his study of Ontario workers during the war, James Naylor observes of the war economy that it ‘had a widely uneven impact on different trades and localities.’13 That tone, rather more common now, after a generation of research on class, regional, and gender themes has highlighted the divisiveness of the war, is captured also by Alvin Finkel and Margaret Conrad in their widely used introductory textbook, in which they argue that the war ‘fail[ed] to usher in a major transformation in society.’ Nevertheless, they still present the war as ‘the catalyst for many changes, the most enduring of which was the enhanced role of the federal government in the lives of all Canadians.’ They also stress industrialization, writing that ‘Canada’s productive capacity received a tremendous boost during the First World War. Although it did not change the direction of the Canadian economy in any major way, the war sped Canadians a little faster down the road to industrial maturity.’14

As all the writers recognize, when the war broke out, the Canadian economy was in a deepening recession, and some of what looks like wartime growth represented no more than a rebound. By the end of 1915 it was realized that this would not be a short war, and the strains of sustaining a growing army and increasing war production were becoming evident. Whatever the pressures, few can have imagined that war conditions would be permanent. Even though the war ran for three more gruelling years, it was not a long period in which to effect fundamental structural changes.

Most of the authors quoted are well aware of long-run trends. Yet their questions, the organization of their narratives, and their language reinforce a story of dramatic change in a short time. A case in point is Norrie, Owram, and Emery’s text, whose section on ‘the long-run economic and social consequences of the war’ addresses ‘three long-run effects’ – industrial development, regional inequities, and implications for western agriculture – that it shows were not consequences at all.15 Rather, they were trends and processes that were already well established before 1914 and that would have continued even had the war not intervened. Much the same point can be made of many of the themes of the standard war narrative, as can be seen in selected information on some principal trends (table 6.1). Some data are available on an annual basis and others only at intervals. Of the latter, information drawn from the decennial census misses the war altogether.16 In interpreting series that fluctuated cyclically, it is important to note that the trade cycle was approaching a peak when the pre-war census was taken in 1911 and was at the low point of a trough when the next census was taken in 1921. Evidence from 1926, after the economy had rebounded, helps to compensate for such variations.

Although the sacrifices and readjustments of outputs and consumption of wartime make it imperfect as a representation of living standards then, real growth in Gross National Product per capita is still the single best measure of economic growth (table 6.1, col. 1).17 From this perspective, the war looks more like a complex cyclical episode than a fundamental moment in the longer-term growth of the economy. In real terms (expressed in 1900 dollars), GNP per capita had doubled from $121 to $246 between 1881 and 1911 (and would reach its pre-war peak in 1913 at $259). As we would expect from the story of high wartime outputs, it reached a new high of $273 in 1916 (and a wartime peak, not shown in the table, of $282 in 1917). Of course we cannot know what the pattern would have been had there been no war, but it gives some context to these numbers to note that the wartime peak was only 9 per cent higher than the level of 1913, making the rate of increase during the war no faster than in the pre-war decade. After 1917 real GNP per capita fell sharply, to a trough of $203 in 1921; that figure, however, was still higher than in any year before 1905. By 1926 it had regained its wartime level.

Table 6.1

Some Main War-Era Trends

|

||||||||||

|

|

Real GNP per capita (1900 $) (1) |

Agriculture in GNP Per cent (2) |

Manufacturing in GNP Per cent (3) |

Iron and steel in manufac-turing Per cent (4) |

Women gainfully occupied (000) (5) |

Women’s share of labour force Per cent (6) |

Improved acres prairie farms (000,000) (7) |

Urban share of popula-tion Per cent (8) |

Federal government spending in GNP Per cent (9) |

|

||||||||||

1881 |

|

121 |

35 |

22 |

15 |

|

|

|

26 |

5.7 |

1891 |

|

140 |

28 |

25 |

14 |

196 |

12 |

1.4 |

32 |

5.4 |

1901 |

|

182 |

25 |

21 |

12 |

239 |

13 |

5.6 |

37 |

5.7 |

1911 |

|

246 |

21 |

21 |

17 |

367 |

13 |

23.0 |

45 |

5.8 |

|

1916 |

273 |

24 |

20 |

19 |

|

|

34.3 |

|

13.6 |

1921 |

|

203 |

16 |

22 |

14 |

490 |

15 |

44.9 |

50 |

8.8 |

1931 |

|

|

|

|

|

666 |

17 |

59.7 |

54 |

|

|

|

Urquhar Table 1.6 |

Urquhart Table 1.1 |

Urquhart Table 1.1 |

Urquhart Table 1.12 |

HSC D86, D88 |

|

HSC M41-43 |

1941 definition HSC A1, A68 |

Gillespie Table B-1 |

|

||||||||||

Note: Leacy, Historical Statistics of Canada, D120, 123 gives a higher estimate for women, based on labour force concept: 1901 and 1911, 15 per cent; 1921, 17 per cent; 1931, 19 per cent.

Sources: M.C. Urquhart, Gross National Product, Canada, 1870–1926: The Derivation of the Estimates (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1993); Leacy, Historical Statistics of Canada; W. Irwin Gillespie, Tax, Borrow & Spend: Financing Federal Spending in Canada 1867–1990 (Ottawa: Carleton University Press, 1991).

In 1881 agriculture had accounted for 35 per cent of GNP and manufacturing for 22 per cent (table 6.1, cols 2 and 3). Three decades later, and after the settlement of the prairies, an entire new agricultural region, agriculture’s share had fallen to 21 per cent. The war briefly reversed this trend, but by 1921 agriculture’s share of GNP had fallen to just one-sixth. Through the same period, manufacturing varied between one-fifth and one-quarter of GNP. Within manufacturing, iron and steel products, at the peak of wartime output, accounted for almost one-fifth of manufacturing value-added (col. 4). This is in keeping with the standard war story, but with 17 per cent of industrial value-added in 1911, this was already the country’s leading industrial sector in the decade before the war. At its wartime peak, iron and steel accounted for about 4 per cent of total GNP. That was a large contribution for a single industry, but even then, other industries accounted for more than 80 per cent of industrial value-added.18 After the war, the share of iron and steel products returned to its normal long-term range, at 14 per cent of the manufacturing sector in 1921 and 1926. That is, wartime production reflected this sector’s peacetime importance and somewhat extended it temporarily, rather than being a fundamental industrial transformation.

With the exception of shells and other munitions, most of what Canada produced during the war was what it could already produce.19 And shells would not be needed after 1918. If the war left genuine, long-term technological gains, they must have been mainly in enhanced industrial capacity for precision work, which could be transferred to other sectors if warranted. But such skills already existed before the war and could have been further developed without munitions work; certainly the technologies to which they might be applied in the 1920s were developing before 1914. Motor vehicles are an obvious example: vehicle registrations were growing before the war and continued to do so even during the war. This was the basis for their sustained expansion afterwards. Much the same could be said of electricals, the telephone, pulp and paper, farm mechanization, and other growth areas of the 1920s.20 In a number of these technologies American companies played a strategic role. Their prominence in Canada was due not to the war but to the evolution of the structure of American business, already well under way before 1914.

Because they figure so prominently in many accounts of the war economy, it is important to discuss women’s role, although the topic is more fully addressed by Joan Sangster in this volume. In 1891, 1901, and 1911 about one ‘gainfully occupied’ worker in eight was female (table 6.1, col. 6). In 1921 women represented 15 per cent of the work force and in 1931 they constituted 17 per cent. Thus, the war era was indeed associated with a growing trend for women to be part of the paid workforce. In terms of the actual work they did, both before and after the war, most of the women worked in clearly gendered sectors. One of these was clerical work, whose rapid growth is sometimes presented as a consequence of wartime replacement of men by women. Women did indeed replace men, but here, too, the war simply continued a pre-war trend.21 More commonly, as we have seen, the story has stressed women’s unconventional work in the war economy, notably in munitions, where it has been estimated that up to 35,000 women were involved.22 That figure comes from sources unlikely to have underestimated; even if accurate, it needs to be put in context. For example, it was less than 10 per cent of the number of women in the ‘gainfully occupied’ labour force in 1911; just 7 per cent of the 490,000 such women in 1921; only slightly over 1 per cent of the whole workforce in either year; and less than 2 per cent of all women aged fifteen and over in Canada in 1911.23 Only a tiny minority of working women were employed in unconventional work, such as the munitions industry, and then only for a short period, at most two years. However emphasized in propaganda at the time and in our subsequent narrative, they were a very small part of the stories of women in the workforce, women in the war, and the wartime economy itself.24

The argument that the future of the prairies was distorted by the war depended in part on the war’s failure to foster industrialization (and a mixed-farming economy) in the west that was most unlikely to occur. For prairie agriculture, the story is that the war prompted undue specialization in grains, encouraged expansion onto inappropriate and marginal lands, and lured farmers unwisely into debt to finance their expansion and into neglect of long-term best-practice techniques for short-term gain. But in most respects the war did no more than extend a process already well under way. Thus, the improved acreage in prairie farms quadrupled in each of the two pre-war decades, to reach 23 million acres by 1911 (table 6.1, col. 7). In each of the next five-year intervals another 11 million acres were added to the total, bringing it to about 45 million acres by 1921. Although some of the extension may have been to marginal lands or may have been achieved at undue cost, the process of expansion was by no means over in 1921. Indeed, another 15 million acres were added to the stock of improved land by 1931, and that still did not end farm expansion.25 Equally, about the same proportion of that improved land (around 50 per cent) was seeded in wheat in both 1911 and 192126 – not out of line for a newly opened, rapidly expanding region. The sharply etched agrarian and regional political protests of the immediate post-war era are evidence of war-induced economic discontent, but that discontent was already emerging strongly in the pre-war period. That is, the war reinforced trends; it did not initiate them.

In the agrarian politics of the post-war period, urbanization was often denounced – and sometimes related to the war. The war, in fact, coincided with what seemed a major threshold in urbanization, since the 1921 census recorded that half the population now lived in urban places.27 The figures in table 6.1 (col. 8) are based on the 1941 definition of urban, which included all incorporated villages, towns, and cities. But no matter what definition is used, the trend was the same, and it had begun long before the war. Indeed, urban centres were so much a part of western development that the huge wave of prairie settlement after 1900 actually accelerated the trend.

Thus far we have considered long-term trends for which there is little or no need to invoke the war. By contrast, the war did sharply increase the share of the federal government in the economy. Throughout the period to 1911 federal spending was equal to somewhat over 5 per cent of GNP (table 6.1, col. 9). By 1916 that figure had jumped to 13.6 per cent, and in 1918 it peaked at 16 per cent. This was a huge change. But even with a new level of federal debt, the government quickly reduced its spending after the war, getting back almost to traditional levels by 1926. The standard story also stresses government’s efforts to regulate the economy, some more effective than others; almost none lasted much beyond the war. One wartime innovation that did live on was the tax on income, albeit at a level that exempted most Canadians. Otherwise, the transformation the war had brought in the federal government’s place in the economy was largely reversed in the post-war period.28 On the other hand, the memory of intervention remained.

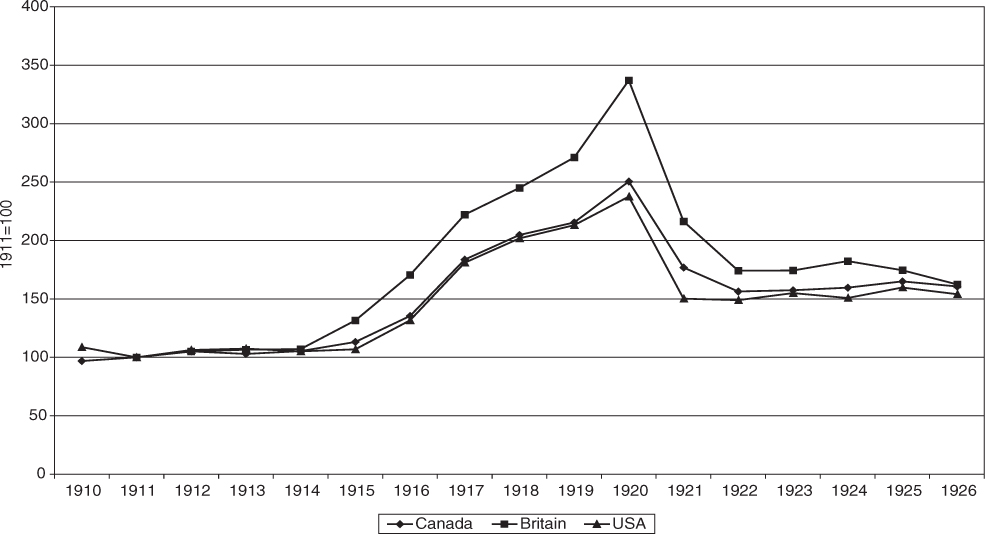

As wartime scarcity and wartime finance began to have their impact during 1915, prices rose. Accelerating inflation led countries to try various measures of price and wage controls and rationing, but with at best partial and limited effectiveness; prices continued to rise anyway. By 1917 prices in Britain had more than doubled from pre-war levels; Canadian and American prices rose less but in almost parallel fashion, even before the United States entered the war (see figure 6.1 for wholesale price indexes).29 In the pre-war decade, Canadian prices had risen considerably, but the wartime inflation was on another scale altogether, one unknown in Canada since the mid-1850s. Although rising prices have been part of the Canadian story of the Great War, their implications have not always been explored, and it is not always evident that the process was universal.30 Discussions can readily leave the impression that the problem could have been prevented by different Canadian policies; for example, this is a clear implication of some accounts of the Canadian government’s approach to war finance. During the war, discussions often focused on the malign figure of the profiteer, caricatured in innumerable cartoons.31 Echoes can be found in later historical accounts, despite the fact that a process this universal and of this magnitude was obviously not attributable to the behaviour of specific individuals or groups.

Inflation affected every aspect of economic life, threatening established understandings of values and relationships among them. The insecurity that resulted was pervasive. Even those whose wartime circumstances allowed their incomes to keep pace with rising costs cannot have been sure that they would continue to do so. In the arguments over wartime sacrifices and choices, existing social fault lines – such as cleavages of class, interest, and region – were sharply highlighted. But the war did not create those divisions.

Among the losers, in one common argument, were Canadian farmers, whose prices were among the first to be subject to control during the war.32 This is especially the case for western grain farmers, who are seen as having borrowed too much, on the expectation of continuing high prices, and thus as having locked themselves into debts that would be very hard to repay at the lower price levels of the 1920s. Ironically, farmers seem to have felt that the marketing processes established during the war were worth preserving or recreating.

Figure 6.1. Wholesale Prices in Three Countries

Sources: Leacy, Historical Statistics of Canada, K33; B.R. Mitchell with Phyllis Deane, Abstract of British Historical Statistics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1962), 476–7; Historical Statistics of the United States, Bicentennial ed. (Washington, D.C., 1976), E23

Both the controls and the buffetings that ordinary people experienced in attempting to keep up might be resisted and resented, but to a degree they could also be understood and accepted as part of winning the war.33 What was much harder to accept was that prices continued to rise after the war, not peaking until 1920. Post-war inflation was clearly a consequence of the war, yet it is important to distinguish between the direct processes involved in fighting and winning a war and the subsequent processes of making peace and reconstructing the economy. After 1920 prices fell quickly, but in 1926 they still were 50 per cent higher than before the war. As Bliss’s careful comment on the war’s effects on business, quoted earlier, suggests, who won and who lost from such precipitous inflation and deflation is less clear than some discussions would suggest; it is by no means clear how far anyone could reliably have discounted all these trends in a way that would ensure strong net gains at each stage. Most obviously, those who borrowed early and paid back in inflated money might have come out ahead if the assets so acquired continued to produce a high enough rate of return once the war was over. In the whole economy, however, such gains were offset by equal and opposite real losses to lenders. In that some of these lenders ultimately were not within the Canadian economy, there may have been some net gain to Canada from the process.

Another implication of wartime inflation is that expressions of current values encountered in the sources at the end of the war are vastly higher than at the beginning. If not carefully discounted, they make wartime growth seem much larger than it was in real terms, and deflating values in the midst of such a rapid and massive disruption is an uncertain process with necessarily arbitrary elements.

The story of prices is a reminder that Canada participated in the culture and institutions of the world economy through flows of goods, capital, credit, people, and information. Both before and after the war, the international reference points for the Canadian economy were Britain and the United States, although the relative balance between them had continued to shift towards the latter. Indeed, one of the war’s most profound long-term economic impacts was the fundamental disruption of the London-centred international financial system by which the world settled accounts.34 During the 1920s states and bankers sought to rebuild what the war had destroyed or to build a new international system; that they ultimately failed had much to do with the depth and severity of the ensuing Great Depression.

Summing up recent historiography on the war and the international economy, Chris Wrigley writes, ‘While it can be acknowledged as a truth that the First World War was a turning point in the history of the international economy, the nature of its impact remains complex and debatable. The effect of the war itself is often difficult to disentangle from other developments. Where the war clearly did have an impact, it could nevertheless be the case that the change would have taken place without it.’35 In essence, in this chapter I seek to make the same case in a specifically Canadian context. The argument is that in the standard Canadian story, major structural changes, long in the making and unlikely to have been any different without the war, are routinely associated with and even attributed to the war. Yet the war did not affect in any fundamental way trends in the structure of the economy and the business system, the prime new technologies, or the dominant urban patterns. Nor did the war economy change any of the fundamental class, regional, gender, interest, and other lines of Canadian society. All of these elements of the story of the war’s impact thus have the story backward: they actually reflect what the Canadian economy had become by 1914.36

Why have we told ourselves otherwise? In essence, historians have followed a political narrative first shaped by actors at the time as they sought to make sense of the events in which they were caught up.37 Once established, periodization, like other kinds of categorization, deeply influences what we can think. Historians have contributed also through their professional attachment to change, often stylized in dramatic terms and organized around turning points – that is, brief moments of actual or potential transformation and even revolution. For textbooks, we can attribute some of the responsibility to the need to use existing secondary material and to fit into established courses and boundaries. Some texts are more effective than others at catching the nuances of recent Canadian literature, with its emphasis on variation and quite specific experiences. Yet even in adding these stories, they cannot avoid reinforcing the main narrative, by emphasis, by pictures, and by not discussing some of the key elements at all. It is common, for example, to rely on pictures, such as those of women munitions workers, whose existence is a function of the wartime propaganda machinery.38 By contrast, there are no pictures of financial processes and other abstract systems.

Munitions factory, ca. 1915 (City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244, Item 850)

The scale of the war, its terrible carnage, and the magnitude of its consequences for the old political order in Europe called deeply into question many basic assumptions about order – political, moral, social, intellectual, and economic. The emergence of a communist regime in Russia was only the most visible evidence of the process. Established understandings of the economic order were, of course, debated throughout the western world. This process had an institutional parallel in the disruption of older patterns of organizing world trade and the settlement of transactions. As the failure of post-war efforts to restore that system suggests, part of the story was really about the peace, a fact that is also evident in the graph of prices, which surged after the war. This is a story that goes back to Keynes and other critics of the post-war processes of re-establishment. Telling it in the Canadian context requires addressing whether Canada had much, if any, autonomy within or influence on the larger macroeconomic processes that shaped it. Another essential issue is what Canadians themselves understood those processes to be and how that affected their decisions. Furthermore, the story of the Canadian economy and the war should begin with a clearer sense of the structure of the economy in 1914. Already a balanced industrial economy, more complex than the traditional story has tended to imply, it was adaptable enough both to send a rapidly expanding contingent overseas and to increase outputs. Its responsiveness and flexibility would be as tested by the return of peace as it had been by the shocks of the war. For the war itself, and its aftermath, the dominant image must be disruption, not transformation.39

It is a pleasure to be able to contribute to a work honouring Craig Brown. As the editor of the first paper I ever submitted to a scholarly journal, he applied his superb editorial skills with a generosity and constructive spirit that were enormously encouraging. In any editing I have undertaken, it is those high standards that I have sought to meet. This paper forms part of a research program undertaken during a Killam Research Fellowship, awarded by the Canada Council, and continued with the support of the Canada Research Chairs program. I am deeply grateful to both. An earlier draft was presented to a colloquium of the History Department at Trent University; my thanks to colleagues for being a sympathetic audience and for their challenging questions. It is not their responsibility that I still do not have answers for many of them.

1 Kenneth Norrie, Douglas Owram, and J.C. Herbert Emery, A History of the Canadian Economy, 3rd ed. (Scarborough: Thomson/Nelson, 2002), 282, 279. See also Robert Bothwell, Ian Drummond, and John English, Canada, 1900–1945 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1987), 169.

2 Robert Craig Brown and Ramsay Cook, Canada 1896–1921: A Nation Transformed (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1974), 234.

3 Pierre Berton, Marching As to War: Canada’s Turbulent Years, 1899–1953 (Toronto: Doubleday Canada, 2001), 1. This understanding of the Canadian socio-economic context also informs Berton’s ‘stereotype’ of Canadian soldiers; see Desmond Morton, When Your Number’s Up: The Canadian Soldier in the First World War (Toronto: Random House, 1993), 277–8.

4 Brown and Cook, Canada, 1896–1921, 249.

5 Gerald Friesen, The Canadian Prairies: A History (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1984), 349. See also John Herd Thompson, The Harvests of War: The Prairie West, 1914–1918 (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1978), 71–2.

6 Alison Prentice et al., Canadian Women: A History, 2nd ed. (Toronto: Harcourt Brace Canada, 1996), 283.

7 Graham D. Taylor and Peter A. Baskerville, A Concise History of Business in Canada (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1994), 390. A similar view is expressed in Don Gillmor, Achille Michaud, and Pierre Turgeon, Canada: A People’s History, (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 2001), 2: 131.

8 Alvin Finkel and Margaret Conrad, History of the Canadian Peoples, 3rd ed. (Toronto: Addison Wesley Longman, 2001), 2:209.

9 Gillmor, Michaud, and Turgeon, Canada: A People’s History, 2:101.

10 For example, see S.N. Broadberry and N.F.R. Crafts, eds, Britain in the International Economy, 1870–1939 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992). Although its title suggests that the book covers the whole period, all but one of the essays end in 1914 or begin after the war.

11 Prentice et al., Canadian Women, 112.

12 Michael Bliss, Northern Enterprise: Five Centuries of Canadian Business (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1987), 374.

13 James Naylor, The New Democracy: Challenging the Social Order in Industrial Ontario, 1914–25 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991), 41.

14 Finkel and Conrad, History of the Canadian Peoples, vol. 2, quotes at 201, 208, and 185–6.

15 History of the Canadian Economy, 277. Friesen, quoted earlier, also goes on to show why the west was developing as it was.

16 In addition to the main census, there was a prairie census in 1916 and an annual postal census of manufactures. More and better annual data were also beginning to be produced by Canada’s growing statistical system.

17 For a discussion of the standard of living question in wartime, see Jay Winter, ‘Paris, London, Berlin: Capital Cities at War’ in Jay Winter and Jean-Louis Robert, eds, Capital Cities at War: Paris, London, Berlin 1914–1919 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 10–13.

18 In terms of employment, iron and steel at its peak in 1917 accounted for over 11 per cent of the 675,000 jobs in industry. See The Canada Year Book 1921 (Ottawa: King’s Printer, 1922), 365.

19 See for example, Ian M. Drummond, Progress without Planning: The Economic History of Ontario from Confederation to the Second World War (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1987), 149–50 and table 9.1, 410. In this book, see also Kris Inwood, ‘The Iron and Steel Industry,’ 201 and tables 11.3, 11.4, 416–18; and Tom Traves, ‘The Development of the Ontario Automobile Industry to 1939,’ 208–15 and table 12.4, 422.

20 In the case of farm mechanization, a common war story has the federal government attempting to foster the adoption of tractors, although there is nothing to suggest that the program had anything to do with the rate of adoption of tractors by farmers. For this story, see Finkel and Conrad, History of the Canadian People, 186; Brown and Cook, Canada, 1896–1921, 238. Norrie, Owram, and Emery (History of the Canadian Economy, 276) show in their war chapter a picture of a custom threshing outfit, yet such mechanized operations were not specifically or uniquely associated with the war. See Cecilia Danysk, Hired Hands: Labour and the Development of Prairie Agriculture, 1880–1930 (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1995), 94.

21 F.H. Leacy, ed., Historical Statistics of Canada, 2nd ed. (Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 1983), D10 to D85. See also note to table 6.1. For trends in office work, see Graham S. Lowe, Women in the Administrative Revolution (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1987), 49.

22 David Carnegie, The History of Munitions Supply in Canada, 1914–1918 (London: Longmans, Green, 1925), 254. The actual passage reads ‘35,000 women, it is estimated, helped to produce munitions in Canada during the war.’

23 It was equivalent to less than 6 per cent of the 600,000 men (or about 16 per cent of the c. 220,000 men with ‘industrial’ occupations) who joined the Canadian Expeditionary Force during the course of the war. For these numbers, see Morton, When Your Number’s Up, 277–9.

24 For context on the biases in the historiography of women and war, see Colin Coates and Cecilia Morgan, Heroines and History: Representations of Madeleine de Verchères and Laura Secord (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002).

25 By 1971, when the series in Historical Statistics of Canada ends, there were over 80 million improved acres of land in prairie farm holdings.

26 See Handbook of Agricultural Statistics, Part 1 – Field Crops 1908–63 (Ottawa: Dominion Bureau of Statistics, 1964), 17–19.

27 Cf. Gillmor, Michaud, and Turgeon, Canada: A People’s History, Vol. 2, 132.

28 On British parallels, see Kathleen Burk, ‘Editor’s Introduction,’ in K. Burk, ed., War and the State: The Transformation of British Government, 1914–1919 (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1982), 4–6.

29 There were equivalent patterns in other price series and other countries, with some variation in amplitudes. See Chris Wrigley, ‘The War and the International Economy,’ in Chris Wrigley, ed., The First World War and the International Economy (Cheltenham, U.K.: Edward Elgar, 2000), 18. Of seventeen countries listed in his table 1.5, only Spain, Australia, New Zealand, India, and the United States had lower peaks than Canada. Most other European countries for which there are data had more severe inflation than the United Kingdom. See also the discussion in Bothwell, Drummond, and English, Canada, 1900–1945, 181–2.

30 The best textbook account is in Bothwell, Drummond, and English, Canada, 1900–1945, 181–2. Much is made of inflation in Prentice et al., Canadian Women, but the presentation is confusing and lacks proportion, for example, in speaking of ‘high prices for the necessities of life’ (231) in 1914–15.

31 Jean-Louis Robert, ‘The Image of the Profiteer,’ in Capital Cities at War, 104–32.

32 See, for example, R.T. Naylor, ‘The Canadian State, the Accumulation of Capital, and the Great War,’ Journal of Canadian Studies 16, 3 and 4 (Fall-Winter 1981), 39.

33 See Ian Hugh Maclean Miller, Our Glory and Our Grief: Torontonians and the Great War (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002), 13.

34 See Norrie, Owram, and Emery, History of the Canadian Economy, 262–3.

35 Wrigley, ‘The War and the International Economy,’ 25.

36 For a similar emphasis, see Bill Albert, South America and the First World War: The Impact of the War on Brazil, Argentina, Peru and Chile (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 2.

37 See, for example, the discussion of sources in Miller, Our Glory and Our Grief, 205–8.

38 See, for example, the images of women workers in munitions in Norrie, Owram, and Emery, History of the Canadian Economy, 273; Gillmor, Michaud, and Turgeon, Canada: A People’s History, 117; Brown and Cook, Canada, 1896–1921, illustrations section after 274; and Peter A. Baskerville, Ontario: Image, Identity, and Power (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 2002), 165.

39 See the account of much earlier wars in Louise Dechêne, Le partage des subsistances au Canada sous le régime français (Montreal: Boreal, 1994).