JOAN SANGSTER

There is not one thing heroic about this work. To set free a man to fight. To make the bombs that kill him …

Why men would keep this from us, I fail to understand. A job is not romance …

Betsy Struthers, ‘The Bullet Factory’

This poetic rendition of women munitions workers during the First World War1 was penned in the 1980s, reflecting more recent feminist aversion to the violent machinery of war as well as a healthy scepticism that women doing the drudgery of men’s work was automatically a sign of progress. A diametrically different portrayal appeared in the official history of munitions manufacture in Canada, written by an army colonel just after the war. In the few paragraphs on women in this long tribute to contracts, technology, and war, the author recounts a story to characterize the ‘development of [women workers’] moral sense without which the memory of the struggle would be sordid.’ A woman making fuses is ‘stunned’ to hear that her son has just been killed at the front, but she refuses to go home and grieve as others urge her to do. Instead, she ‘set her face like flint and worked harder than ever’ as a means of asserting her patriotic duty to avenge her son.2 One lesson conveyed – that women took up factory war work for patriotic reasons – remained fixed in many historical accounts for years to come and sometimes even reappears in popular culture today.3

It is hardly surprising that these versions of women and the First World War, distinguished by form, presentation, time period, and ideology, vary so dramatically. What is of interest is why and how such reconstructions of the memory of war make their way into our historical writing and everyday consciousness. Interpretations of women and war – even apparently fictional ones – rest in part on events, documents, and actual living people, but each is also the product of interpretation, engagement, and sensibility, or in other words, the product of history. In this chapter I explore the mobilization of Canadian women during the First World War, giving fresh attention to how and why the memory of war has changed over time. Although there is strong evidence that the war did not result in significant shifts in gender and social structures, the wartime crisis remains a useful means of exploring these shifting historical interpretations, as well as the resilience of gender ideologies, class differences, and social tensions in Canadian society.

Many explorations of the two world wars in North America and Britain over the last twenty years have been focused on the ‘watershed question,’4 asking if changes in work, culture, family, and state provision during wartime effected meaningful and long-lasting changes in women’s lives. This is a legitimate question, especially given the emphasis in war writing on querying transformations in politics, men’s consciousness, and modern culture, but it is nonetheless difficult to measure the war as an engine of ‘progress’ for all Canadian women because of the immense contradictions that wartime mobilization produced. Although it is a much-repeated truism in feminist writing that women’s experiences are marked by differences as much as commonality, it is certainly worth repeating with regard to social class and ethnicity in the context of the Great War. While working-class women were perceived by the state as potential factory fodder, middle-class women were more often courted as political allies. While the latter often portrayed the war as a pathway to political and social ‘regeneration,’ the former became the very real, repressive targets of anxieties and fears concerning moral ‘degeneration.’ Ethnicity further cross-cut these divisions, with white, British-born and Anglo women more likely to embrace the war effort, while women from so-called enemy-alien nations faced marginalization and, for some, the agony of internment of male family members.5 While conscription and trench warfare seemed to impose the ultimate gender demarcation in experience, separating women and men into the two solitudes of the home front and the war front, in fact the Great War accentuated class differences so decidedly that home front women also appeared to inhabit two – or more – solitudes by 1919.

In his impressive exploration of memory and the First World War, Jonathan Vance argues that, by the interwar period, certain hegemonic interpretations of the war had already come to dominate history, politics, and culture. Even writers apparently critiquing the war often unintentionally reinforced these notions of the war as a well-intentioned crusade for democracy; as a homogenizing, unifying event; and as the stimulus to the creation of a new nation and indeed of a new Canadian manhood.6 War mobilization, the state, and gender ideology, as feminist historians have also argued, were interconnected in important ways. The dominant iconography during the First World War revealed man as the ‘just warrior’ and woman as the moral mother, sacrificing her sons to the cause.7 Indeed, this was one of the images used by Nellie McClung in Next of Kin, her 1917 book portraying the war as a regenerating ‘comeback of the soul.’8 The related theme of men’s honourable protection of women and family was utilized in recruiting, symbolized in the government’s poster ‘Hun or Home?’ by an ogre-like German enemy threatening a defenceless mother holding a baby.9 Although other versions of manhood and war were voiced by some dissident socialists, pacifists, and feminists, these definitions were beleaguered and marginalized.10

Even as the war was being fought, Canadian women were creating their own historical version of the war, often drawing on these same images and justifications in order to place themselves strategically within, rather than marginal to, the nation. Women as sacrificing mothers was a key theme in such writing, but so, too, was women as nation builders. Anglo-saxon, middle-class, professional, and politically astute women used the organ of the National Council of Women, Women’s Century, to promote their view that the war would inevitably prove their worth as citizens and lead to a new era described in no less than millenarian rhetoric. British and Canadian women, they claimed, were creating a new ‘soul’ of the nation, contributing to a ‘nobler conception of the state,’ and participating in a ‘peaceful revolution’ for women.11 The Canadian ‘nation’ they extolled, of course, was constructed in the image of their own racial, ethnic, and cultured personas. At the Women’s War Conference called in 1918 by the government, these same women asserted their historical significance by representing themselves as the ‘Mothers of Consolidation,’ walking in the footsteps of other state-builders, the Fathers of Confederation: ‘We are looking forward to a period of reconstruction … As those who fifty years ago gathered together on behalf of their country were known as the “Fathers of Confederation” so these women will be known as the Mothers of Consolidation.’12

Labour newspapers also advanced a watershed theory of the war before it was even over. The Industrial Banner argued that the war was both creating a vital ‘new nation’ and that labour could never return to its former view of women: ‘there will be [a] new status that womanhood will occupy … Things will never revert back to where they were prior to the outbreak of hostilities. That is clearly impossible for womanhood is facing an altogether different horizon, when larger and still greater opportunities open out before the sex.’13 Even some socialists opposed to the war portrayed it as a great divide, arguing that the suffering and exploitation associated with war-making would lead to the radicalization of working-class women in the future.

The notions that war altered women’s political claim to citizenship, led to more acceptance of working women, and undermined ‘Victorian’ sexual and social mores thus emerged in the interwar years as something of historical wisdom. Although historians would later marshal evidence to argue that changing sexual mores were evident in the earlier years of the twentieth century, those people who lived through the war insisted that it not only ‘shot religion high, wide and handsome,’ but also transformed sexual morality, in part because the young were less worried about their ‘virtue’ when death could claim soldiers so quickly. Oral history reveals the power of this image. The war, concluded one man, occasioned a ‘letdown in moral and conduct and dress,’ so much so that by the 1920s ‘there was a lot of horseplay, immorality … girls were more permissive, and the men more daring.’14 It is possible that the way in which historical memory is created and an interviewee’s cognizance of the centrality of this dramatic world event became an understandable hook on which to hang more slowly evolving social changes.

As Cynthia Commachio points out, a defining cultural marker of the ‘flaming youth’ in the 1920s was their claim to be completely different from pre-war youth; their increased social freedom and embrace of consumer culture was self-consciously promoted as a reaction to the war. In popular memory, in other words, the war became a key reference point to explain longer-term shifts in gender relations of the early twentieth century. This theme was often relayed through the popular press. In ‘The Challenge of Freedom,’ appearing in Chatelaine in 1929, the author takes as her basic starting point the assumption that a new ‘freedom, social political and economic’ had been granted to women after the war. During the war, said politician Irene Parlby, women were needed to ‘carry on the work when men were overseas,’ and they both exhibited a new sense of service and secured new recognition for their work. An illustration for the article showed nurses aiding injured soldiers, making the point that ‘during the war, with the courage of an altered status and freedom, women gave “till it hurt.”’15

In contrast, a controversial Canadian film of the 1920s, Carry On, Sergeant! suggested that the cultural images of femininity had not been transformed during the war. Filmed in ‘Hollywood North,’ and intended to provide a truly Canadian war story, the film emphasized the heroism of serviceman Jim McKay and his struggle overseas to stay dedicated to the pure and true wife at home, in the face of the aggressive temptation posed by a French estaminet girl, Marthe, who relentlessly pursues him. Jim eventually gives in to her advances, only to die on the battlefront, at least redeemed for his sexual sins and disloyalty to his wife by dying for his country. The film offered a traditional, dichtomized view of good versus evil women; moreover, the mere presence of the sexual theme was seen as controversial when the film made its debut.16

While many war novels were primarily concerned with the traumatic effects of warfare upon Canadian manhood, authors did deal, tangentially, with women. Some authors reproduced the image of the suffering, sacrificing mother, like the Icelandic mother portrayed in Laura Salverson’s Viking Heart, who loses her beloved son to the war.17 Novels also portrayed the war as the pressure cooker that produced a new woman and new gender roles. In Hugh MacLennan’s Barometer Rising, the hero’s love interest, Penny, not only worked as a ship designer (a highly unlikely occupation if there ever was one) but gave birth to his child before they married. Her unusual occupation, her intellectual stature, and her refusal to completely abandon her child in shame left no doubt that she represented a clear break with Edwardian womanhood.18 Likewise, in Douglas Durkin’s The Magpie, the returned veteran, Craig, interacted with three important women in his life, one of whom finds her political voice in the aftermath of her own husband’s death at the front, for she comes to see the war as a callous, greedy exercise in power by the ruling elite. She subsequently becomes an outspoken pacifist and socialist, living with a man who is a labour organizer. Even Craig’s wife, who proves to be selfish, materialistic, and apolitical, secures her new amusements in the country club, cocktails, and adultery, surely something of a departure from past norms. Craig’s ultimate love choice is an accomplished sculptor who finds her artistic voice abroad after working as a nurse in the war.19

The notion of a new woman, born of wartime exigencies, was not simply a creation of masculine authors. Georgina Sime, an upper-middle-class Scottish emigrant to Canada and short-story writer, also portrayed the war as a turning point, creating ‘new freedom’ for working women. In ‘Munitions,’ a piece in her collection, Sister Women, she explored the thoughts of a young domestic turned munitions worker as she rode the streetcar to work one day. The protagonist, Bertha, is literally ‘liberated’ from her safe, boring, and stultifying work as a maid when she takes on munitions work at the urging of a fellow servant. Sime uses the springtime weather as a metaphor for Bertha’s regeneration: ‘the sense of freedom! The joy of being done with cap and gown. The feeling that you could draw your breath– speak as you liked – wear overalls like men – curse if you liked.’ While Sime’s story replays some of the stock themes of middle-class women’s organizations – that munitions work, despite the drudgery involved, would offer women new opportunities – it did convey a less negative view of working-class women. The munitions women’s loud behaviour, bawdiness, and sexualized humour on the streetcar are portrayed not as immoral but rather as good-natured camaraderie.20

The resilient equation of the war with new social and political roles for women was in part shaped by Canada’s close cultural connections to Britain. British novels, newspapers, and immigrants created a path of communication between the two countries, and the British war experience was thus extrapolated to Canada. Commentaries and studies of British women war workers were plentiful, also claiming a ‘renaissance’ in women’s work and status.21 Even in a recent, 1990s Canadian film on women in the First World War, And We Knew How to Dance, this connection is used: footage of British militant suffragettes (including one throwing herself under the King’s horse) and possibly footage of British munitions workers are integrated. By interviewing women whose memories stress women’s non-traditional work and the granting of equality, the filmmakers dramatically and visually reproduce for a contemporary audience the image of the war as a significant breakthrough for Canadian women.

The image of the war as political turning point for women was occasionally queried in the interwar period by feminists disappointed with women’s apparent abandonment of reform and their return to ‘partyism.’22 More recently, historians have also questioned the notion that it was the war that led directly to enhanced political equality.23 However, one can forgive the women at the time for their claims to the contrary, since there was the appearance of a more direct connection. Well-organized, publicly vocal, middle-class women continually promoted the talents of the ‘new woman’ that war had uncovered; their urgent calls for increasing substitution of women in non-traditional ‘men’s work’ underscored their faith that the war would usher in new equality for women – though ironically, they were building a case for their campaign on the arduous labour of working-class women.24

The view of the war as a wake-up call for politicians who rewarded loyal women with the vote remained so tenacious that it affected succeeding generations of historians. Certainly, women’s pro-war loyalty had much to do with Borden’s Wartime Elections Act, a ‘gerrymandering’ ploy used to secure the votes of pro-war women, as Robert Craig Brown frankly notes.25 But according to historian Catherine Cleverdon (whose book appeared in 1950), even the subsequent, wider granting of suffrage in 1918 was largely due to the war. Her interpretation may have been shaped by images of the more recently fought Second World War; it did not question the claims of suffragists themselves that the war was a ‘lever’ that forced ‘women’s body and soul’ into the political arena, and as a consequence, the ‘ballot’ was handed to her after little struggle.26

This argument was eventually challenged by some feminist historians in the 1970s and 1980s, whose critical analysis of the class and race ideology of mainstream suffragists suggested that the war provided male elites with ‘an excuse’ more than a reason to grant the vote.27 As a more critical feminist history emerged, the popular image of the First World War as a watershed that ‘drastically changed the role of Canadian women in the workforce,’ was also questioned, a theme confirmed by subsequent studies of the resilient gender inequalities faced by working women in the 1920s.28 Our reinterpretations, however, have also left us, ironically, in the position of countering the lingering memory of war in women’s oral histories that remain, still, constructed around the war as a life-changing watershed in their lives.

Since the idea that women’s work was transformed during the First World War has been central to the memory of war, we should examine the issue of the mobilization of women’s wage labour for war. Nowhere is the historical evidence more problematic, for every statistic on women’s work, as Deborah Thom argues for the British experience, is suffused with ideology. Statistics showing women’s massive entrance into men’s jobs and munitions in particular were used at the time to promote further use of female labour, to reassure the public that the government labour plan was succeeding, and even to convince women themselves that work was available. For example, the claim by the Canadian government’s Imperial Munitions Board that 35,000 women were working in munitions in 1917 is highly unlikely, compared with other Montreal and Ontario factory employment numbers.29

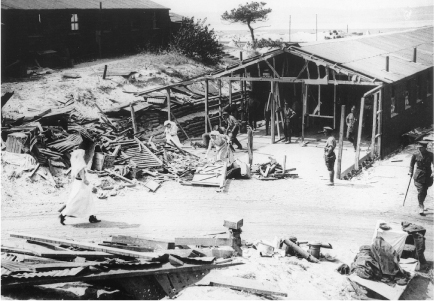

Canadian sisters looking around the ruins of their quarters, which were struck by a bomb, 3rd Canadian Stationary Hospital, ca. 1918 (Archives of Ontario, C224-0-0-10-48, AO 3928)

Photographs are also an intriguingly deceptive source. We are well acquainted with popular images of women making large shells, perhaps dressed in unconventional trousers or overalls, handling machinery and metals coded at the time as masculine. In both Britain and Canada, the government issued a special book of photographs (and in Canada a film) exhibiting this work in order to entice other employers to take on female labour.30 But how representative were such photographs when the majority of working women remained in domestic and other factory employment, and when the largest female incursion into male jobs may have been in clerical work? Not only were munitions photos intended as a labour recruiting tool; they have also remained seared on the public memory, because they were more interesting, unusual, and, at the time, even exotic, given women’s costume of bandanas and bloomers.31 Feminist historians, too, have often utilized pictures of women’s ‘non-traditional’ work as a means of representing war work, reflecting our own understandable fascination with the malleability of the sexual division of labour.32

In Ontario, where probably around 60 per cent of munitions work was located, the provincial government was also able more accurately to track women seeking out munitions work, since the advent of war coincided with the development of new state-run employment bureaux (including separate women’s departments), conscious of their record-keeping role; in some cities, the government admitted, people assumed the bureaux were only for the recruitment of war workers.33 Even in Ontario, bureaucrats sometimes declared that ‘many’ women were flooding into munitions, but added that they did not have the exact statistics on hand.34 Moreover, it is crucial to remember that, outside central Canada, war work was sparse: according to one estimate in 1916, only 1 per cent of war contracts were being filled in the west and 4 per cent in the Maritimes.35 Women’s work encompassed very different problems in these regions; in the last year of the war, for instance, Saskatchewan women’s groups were still desperately pressing all levels of government to find ways to encourage women to take up domestic positions in rural areas.36

At the beginning of the war general unemployment ravaged most of the country. The crisis was so severe that Vancouver middle-class women’s groups held emergency mass meetings to raise funds and devise means to deal with poverty-stricken ‘unemployed girls.’ Through 1915 young women were still being forced into service when they wanted factory work; shelters were being sought for the ‘casual poor’; and some female occupations reported that there was a 25 to 30 per cent shortage of jobs for women seeking work.37 An Ontario government inquiry into unemployment published in 1916 was surprised not at women’s presence in the workforce, but only at the massive numbers – as many 8–10,000 – who were jobless. In response, officials could only muster the unimaginative recommendation that women have better vocational training, at home and institutionally, primarily for domestic service, since ‘any woman who is a competent house worker need not fear unemployment.’38 In fact, the National Council of Women (NCW) repeated this suggestion throughout the war, concerned as it was with the shortage of maids. Will it become so desperate that families will have to ‘move into hotels’ as was the case in the United States, worried NCW leader Constance Hamilton, revealing her rather privileged view of the world.39 Recovery in central Canada was not evident until 1916, as women filled clerical positions or found work on war contracts; in the west, bereft of such wartime welfare for business, unemployment plagued some cities well into 1917.

The substitution of women for men was not a significant political issue until later in 1916, when Joseph Flavelle, in charge of the Imperial Munitions Board (IMB), persuaded Borden and the cabinet to create a special labour portfolio in the IMB, to which he appointed one of his eager political protégés, Ontario MPP Mark Irish. Irish made the introduction of female labour into munitions one of his major priorities; he publicized the issue, circulated the British and Canadian books on women in munitions, tried to work closely with provincial governments to faciliate the use of female munitions workers, and lobbied manufacturers heavily, sometimes enticing them with the suggestion that women would be a more malleable, less militant workforce. He also appointed two female ‘welfare supervisors,’ both eminently respectable women, to offer advice to and supervision of the new female workforce.40

There is no doubt that Irish faced some opposition, a fact he was careful to note in his retrospective view of his accomplishments. Employers were sometimes reluctant to hire women for non-traditional jobs, not always because they feared women’s lack of skill or strength but because they did not see the expense involved as justifying the outlay for new facilities such as restrooms and lunchrooms. In 1917, for instance, when some manufacturers perceived a coming downturn in contracts, they resisted hiring women, grumbled Irish, because they did not want to make the expensive ‘alterations’ necessary; they were looking for the largest return on their cash in a short period of time. Similarly, expense was a concern in the internal government debate about hiring women in an explosives plant in Trenton. While one reason was the protective fear of the effects that dangerous chemical work might have on women’s health, in the list of four reasons given number one was that the ‘large expenditure of money’ needed to create facilities for women did not make the substitution ‘economic’ enough.41 Perhaps their decision was fortunate, since on Thanksgiving Day 1918 the plant exploded, levelling half the enterprise and resulting in an exodus of refugees from the town.42

It was not simply that employers feared unsettling the gendered division of labour; occasionally, they saw some working-class women as unsuitable. The company used to hire female inspectors complained initially that ‘common factory girls’ could not or would not do the job well, because they were less committed to the war, while more dedicated, middle-class women ‘would not go down to factory districts and work in close contact with an ordinary class of labour.’ This executive was soon proved wrong: a newspaper article trumpeting the availability of inspection work encouraged two well-educated Peterborough women to write to the prime minister asking for jobs in Toronto, and their successful plan to flee sedate Peterborough reminds us that women did utilize the war as an opportunity for escape or adventure.43

Irish faced other obstacles. In order to persuade women that night shifts posed no dangers to women trying to get to work, the chief press censor agreed to suppress reports of ‘women being interfered with on the streets,’ and some provincial governments altered legal prohibitions on women’s night work. The Ontario government partially relaxed its night work rules for war work, but rejected attempts by some factory owners eager to do likewise in their workplaces.44 The Quebec government, less enthusiastic about the war, refused Irish’s overtures concerning night work and adhered rigidly to other limitations on women’s factory work, much to the annoyance of Irish and the IMB. Irish understandably had more success with patriotic, English middle-class women who set up YWCA-sponsored canteens for factory women. These examples suggest that the federal government’s attitude towards female labour was as much pragmatic and cost conscious as it was protective. Similarly, an Ontario government study arguing for a nine-hour day for women used munitions workers to make the point that reasonable hours would ‘eliminate fatigue’ and mistakes and also lead to ‘maximum output.’45

The philosophy of the IMB concerning the use of female labour was multifaceted. Although both Irish and Flavelle perceived that filling labour shortages was the key issue, Irish also believed that by substituting women, men not only would be released for service, but would be literally edged out. The use of female labour was thus a subtle recruiting tool for the army. Not all government leaders agreed; the future prime minister, R.B. Bennett, complained to Irish that the established gendered division of labour, if not gender peace, would be upset, and according to Irish, Bennett actively discouraged Winnipeg women from working in industry or farm production: ‘[Bennett claims] the employment of women will create a female industrial army doing the work of men at a low wage, which, when the overseas force returns, will be opposed by a male army of unemployed … women once engaged in factory work will never give it up.’46

If the state’s response to female wage earners was shaped by economic and pragmatic issues as well as army recruiting concerns, what was women’s response to the publicized claim that new, non-traditional jobs were available for them? The answers were ambiguous. In Montreal, Nancy Christie shows, these jobs were not necessarily easy to fill, and the Women’s War Registry recommended situating middle-class women in them so that they would not ‘compete with returned soldiers.’47 In Toronto and other centres, women reportedly lined up for munitions work; in one year, over 6,000 women applied for munitions jobs, although only 2,000 were placed. Women’s responses, in other words, were part of a continuing tradition of working-class women moving from one job to another in search of more hospitable working conditions and better pay. With ‘tales of fortunes’ to be made in munitions, working-class women were just as likely as anyone else to want a share.48 The fact that munitions work was sought after also led to ethnocentric cries to keep ‘foreigners’ and ‘aliens’ out – indeed, for Irish this issue was just as explosive as female labour, judging by the hostile letters to the IMB about ‘aliens’ securing placement in war industry.

Women accustomed to factory work may have been less intimidated by the sight of machinery than IMB publicity and articles written by middle-class women suggested. A 1918 Ontario study of applicants for munitions work ascertained that the vast majority were single women of Canadian or British descent between twenty and thirty years of age, and, significantly, over 50 per cent hailed from other factory or domestic work. Far fewer were from the professions or had been ‘leisured’ (a category that may have designated homemakers). In Ontario and Montreal, as many as one-third (a fairly high percentage) were married women, suggesting that working-class wives were also trying to bolster the family economy when jobs were temporarily plentiful.49

The questions of how skilled this work was and also how women perceived their own labour are difficult to ascertain. The label given to women’s munitions work, namely, ‘diluted’ labour, was also suffused with ideology. If dilution meant taking a skilled job and breaking it down into unskilled parts, this was not an accurate description of all female positions; rather, it simply reflected a value judgment about women doing the work! Some of the jobs, assembling fuses and shells, for instance, simply directly substituted female for ‘unskilled’ male labour. Ironically some of these repetitive tasks, such as operating punch presses, would later be dominated by females in the mass production consumer and electrical industries that flourished after the war. It may be, as Thom suggests for Britain, that there were fewer technological shifts in women’s work than we imagine – ‘the innovation was more in the telling of the tale and in the management of people.’50

It is true that, by war’s end, a small number of women had tasted male work for the first time as they operated elevators, lathes, or milled tools. The Labour Gazette carefully plotted these changes across the country, noting when women were used by piano manufacturing firms in Toronto, as bus conductors in Halifax, or in the rail yards in Fort William. However, these instances were relatively rare, so that in late 1918 it was recorded that the substitution that was ‘commonplace’ in Britain was yet in an ‘experimental stage’ in Canada.51 Rarity made it all the more newsworthy. In Kingston a newspaper columnist entertained his readers with a treatise about women tram conductors: Would their morals be compromised, could they handle it physically? How would customers react? he asked at great length.52

One of the most detailed studies of women’s work, a survey of industrial occupations in Montreal conducted by Enid Price, located a small number of women in railway shops and new industrial positions for women in about half of the metal-working plants doing munitions work, but only one plant claimed that women were paid ‘at the same rate as men.’ Usually, substantial differentials existed in women’s and men’s pay rates; moreover, munitions provided men, proportionately more than women, with the majority of jobs.53 There was little change in rubber, garment, and other factories where women were already a presence, but more noticeable substitution in clerical occupations, such as banking, where wartime labour shortages and the substantial use of female labour not only accelerated a trend towards ‘feminization’ already in motion, but caused ‘enduring’ changes to the nature of clerical work.54 Even if employers were eager to hire women, telling Price that females ‘did routine work better than men,’ they did not abandon their gendered understanding of why and how women worked. The problem with women, bankers intoned, was that they did not see earning as lifelong, they would not do overtime, and if ‘a better position is offered they leave without scruples,’ a sign, apparently, not of entrepreneurship but of ‘disloyalty.’55 Unfortunately, this rare wartime survey drew its information from clerical and managerial staff, not from workers; also, it was sponsored by a business-dominated organization, though one with prominent liberal feminists involved, as an aid to understanding ‘what may be achieved in industry with the increased volume of industrial output by unity of purpose and effort.’56 It, too, in other words, was shaped by ideological suppositions concerning women and work.

Aside from the inflated numbers of women workers, one of the enduring munitions myths was that many women who did not need paid employment took this work for patriotic reasons. Indeed, in And We Knew How to Dance, one informant says, ‘there was everything from poor beggars to society women. We had them getting brought down to work in their chauffeured limousines.’57 Some women may have perceived their work to be both necessary and patriotic, but there is not clear evidence of chauffeured limousines transporting grande dames to the production lines. This myth was seldom promoted in the labour press, more concerned with issues of wages and working conditions and with scoring a political point about class exploitation. In 1915 the Industrial Banner published an exposé of women’s exploitation by peace activist Laura Hughes, who, like many middle-class women before her, went ‘undercover’ to discover life as a real ‘worker.’ Hughes reported on bad ventilation, crowded rooms, and poor pay for unending piecework at the Simpson’s knitting mill that supplied underwear for government contracts.58 Later Banner editorials complained that men and women were being mercilessly exploited in munitions as the owners accrued great profits, ‘taking it out of the hides of their working men and women and working girls by reducing their wages and in some instances increasing their hours of labour as well.’59

Ignoring government pleas not to interrupt war production, women workers also protested, even walked off the job, if they were aggrieved, though press censorship may have kept some protests hidden from public scrutiny.60 Hamilton women munitions inspectors threatened to strike in 1917 when faced with wage reductions for incoming workers, and a conflict was narrowly avoided. In the same year, a group of women approached the Toronto Star in order to gain publicity for their grievances. ‘They are killing us off as fast as they are killing men at the trenches,’ the deputation of six complained with considerable dramatic effect. They cited the case of a fellow worker who supposedly had dropped dead in the streetcar (though she had heart trouble) as well as two others whose fatigue had led to tragic consequences. Twelve-hour shifts, night work, a six-day week, and difficult working conditions were described by the ‘girls,’ who claimed that they had just refused to work a fourteen-hour shift and, as a result, had been told to leave.61 Oral recollections also relay a less than romantic picture of munitions work. One woman working on shells remembers her factory as ‘all these avenues and avenues of clanking, grinding, crashing machines … the machinery was all open. The one thing that they were terrified of was the belts and our hair … and [to the back of us] was a blasting furnace so if there ever was a fire, nothing could have saved us.’62

One of the most telling indicators of gender relations during the war was the attitude of organized labour to the very limited incursion of women into non-traditional jobs. Early skirmishes between unions and employers primarily concerned fair-wage clauses in munitions contracts or the prospect of registration as a feared precursor to conscription.63 Nonetheless, women doing men’s work at lower pay, as well as the de-skilling of work, had always been a perceived threat for organized labour, raising the spectre of a downward pressure on male wages; labour activists warned that capitalists would never easily relinquish their ‘stranglehold on [cheaper] labour.’ Inevitably, then, there were tensions from the shop floor relayed to the political realm: Irish dealt with rumours of a protest by male tram conductors in Toronto over the introduction of women, and when a few women were hired into Montreal railway shops, male workers as far away as Winnipeg were mobilized, ‘incensed’ as they were by the threat of ‘dilution.’64 Nationally, the Trades and Labour Congress (TLC) also became agitated. Their 1917 meeting called for the unionization of women in order to stem their ‘exploitation’ and their threat to male wages; in 1918 they again urged the government to ‘protect’ those women replacing men with better working conditions, though they were also adamant that female labour should not be used before all male labour was exhausted. A more positive strategy was the TLC’s recommendation, endorsed by many labour papers, for equal pay.65 Such pronoucements were in keeping with pre-war ideals; the labour movement, indeed many socialists, embraced the ideal of a family wage with a male breadwinner, seeing the employment of children and wives as a sign of exploitation, not liberation.

As the economy recovered by 1916–17, more women organized, and more went on strike in ‘traditional’ areas of female work. Like men, women embraced unions, even in the public sector for the first time, as a means of protecting their meagre earnings from inflation and protesting intensified work regimes. Judging by the number of strikes involving women, argues Linda Kealey, the period from 1915–20 saw sharp increases in women’s union activism.66 From small-town telephone operators to urban laundry workers, women were showing new interest in the power unions might offer them, dispelling any notion that they were too timid to strike. In Vancouver, a bewildered man was astonished when irate female laundry workers climbed on his car and told him to take his shirts elsewhere.67

Labour struggles during the war thus reflected some masculine ambivalence about female labour but also the rising tide of working-class – especially rank-and-file – militancy. Where women and men shared workplaces, they sometimes struck together, though they seldom questioned the gendered division of labour within the plant. This was the case in a Victoria munitions strike of 1917, sparked by the dismissal of an elected committee-man by a manager determined not to recognize any union group other than that of his skilled mechanics. Other male and female workers in the plant were determined to secure some union representation as well. Moreover, strikers did not rise to the bait when the general manager made the potentially divisive argument that he had been told by the IMB to ‘replace as many men as possible with women.’ Nor was it only in munitions, or in mixed-gender workplaces, that women’s militancy occurred. In a strike of candy makers in Winnipeg the next year, the predominantly female workforce complained that some were working ‘large machinery, replacing men who went to the front’ for paltry wages of $9.00 a week. It was not the crossover into male jobs that was the issue, but the low wages, wildly fluctuating hours offered, and ‘petty persecutions’ by foremen and forewomen (the latter ‘to our shame’ said organizer and socialist Helen Armstrong) that motivated the demand for unionization.68

It is true that, when all the unskilled in a workplace were women, the skilled men might well abandon them. This was the case in an Ottawa strike of women press feeders who could not persuade the male plate printers to support them when they walked out and attempted to unionize. The girls claimed a fellow worker had been fired for merely ‘laughing’ on the line; management labelled it rampant ‘insubordination’ and proceeded to hire replacements. By 1919 the strike became a contested issue within labour’s ranks as the Trades and Labour Congress and its local allies offered no aid to the union, urging the women to return to work. According to one male militant, one disreputable trade union leader was letting his daughter cross the picket line! There is no ‘pep’ in the TLC anymore, charged a male supporter of the women strikers, indicating that the issue was not only one of gender or unskilled/skilled divisions; rather, radicals also saw this as proof of a sedate, accommodating union bureaucracy.69

What is most revealing about all the wartime strikes is that almost none was fought over equal pay or dilution issues. One exception was a Toronto strike of aeroplane assemblers in which 600 men and 100 women struck over wages, overtime, and reinstatement of a fired unionist. The union wanted women to be paid the same rate as machinists and toolmakers when they ‘were doing the same work,’ and it argued strongly to have women’s rates raised, especially in jobs they shared with men. While labour portrayed the skilled men as chivalrous, claiming the machinists had ‘nothing to gain but are out to support those lower down,’ their support for equal pay and better female rates was accompanied by the usual fears that female labour would diminish men’s earning power or their access to jobs. The labour men, reported the press, said women were ‘not indicating if they would return to domestic life after the war, and if it came to laying off a man or woman, the employers had to take a stand.’ There was no mistaking what unionists wanted this to be: ‘we have nothing against the employment of women … what we do claim is that returned soldiers whom the firm apparently will not employ on this work, could do the work and if women are employed then they should be paid the same rate of wages as men.’70 This strike, however, was an exception to a more general pattern of men and women accepting a gendered division of labour but arguing collectively and militantly for the improvement of this entire structure for all working people.

The concentration of the press on women in munitions was parallelled by their fascination with women farm workers. By 1917 many levels of government were frantic to find people to harvest crops, also important to the war effort. In eastern Ontario, farm labour was so scarce that the respectables overseeing the farm recruiting urged that a woman recently convicted of wearing male attire have her federal sentence suspended so that she could join the ranks of rural labour. Why should someone be sent to a federal prison for donning men’s clothes, they mused, when she could be out doing the work of a man?71 Farm labour shortages were also a problem in the prairie west, where women were sought after as domestic and general hands.

The most visible historical records, again, often stress women’s incursion into untraditional labour and the recruitment of patriotic, Anglo-Saxon, middle-class girls to join the ranks of the ‘farmerettes.’ Official pictures published by the Ontario government, for instance, showed women beside large trucks and tractors, in rustic hats and even bloomers, posing with the tools of their trade, often smiling for the camera. Newspapers, still entranced with the notion of ‘inverted roles,’ in this case cultured, urban females joining the ranks of rustic, rougher labour, gave the campaign considerable publicity. Like Mark Irish, the government claimed its recruitment project was initially opposed by reluctant farmers and growers, but with some prodding and after a summer of work, they realized how useful women were, leading to new acceptance of female labour and higher food production. Within this major recruitment, however, a gendered division of labour remained intact: men were used for harvesting, girls and women for ‘lighter’ work, such as fruit picking, which, as a participant at the Women’s War Conference noted, had always been female work. Moreover, the actual numbers of ‘farmerettes,’ especially urban women with no connection to farms, were smaller than other groups. The Ontario government first targeted high school boys in 1917, adding girls when the latter pushed to be included, and in the following year male harvesters numbered 6,000, high school boys 8,000, and the fruit pickers campaign placed only 1,200 women.72

As with the mobilization of munitions labour, the question was not so much that women were doing forms of work unknown to female labour, but that growers were reluctant to provide the economic outlay – such as housing – for this temporary workforce. As Margaret Kechnie points out, the recruitment of college girls for farm work by well-placed women reformers, in cooperation with the Ontario government, was not without its wrinkles. Despite the attempts of the YWCA to set up supervised camps for the girls, amenities were rustic – worse, wages were so low that there were rumours of a berry pickers’ strike in 1917.73 Bad weather, uncertain harvests, costs of food and board caused discontent, and the next year, notwithstanding the intervention of the NCW to improve the situation,74 the number of college girls declined, while high school girls, especially those raised on farms, predominated.

The farmerettes were not simply overwhelmed by the difficulties of making a decent wage through such hard, hot labour. As Kechnie relates, using the diary of one University of Toronto student, they also looked down on their rural counterparts, who were seen as common and coarse.75 Some farmerettes also saw the regular farm workers as immoral. Indeed, a major theme running through the recruitment of farm and urban labour was the belief that women’s morals needed extra protection, endangered as they were by war conditions. The war was certainly not a homogenizing and unifying experience for one middle-class woman who went to pick fruit, only to complain bitterly to the government that her fellow female pickers were predominantly low-class, immoral, and sexually depraved. In her lengthly report on the flax pickers, Miss Taylor claimed there were constant ‘moral irregularities,’ largely because the flax-milling company refused to pay for matrons from the YWCA or the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU).

The girls, she wrote, had ‘rough house dances every night in the barn,’ entertained men in their tents, and displayed absolutely no sense of modesty, doing their washing ‘half dressed’ near country roads where anybody could look on. Their tents were like pig stys, with ‘half washed underwear hanging on the trees.’ ‘It smelt like a choir of negroes,’ she wrote, with a racist flourish. The so-called camp captain in charge, she continued with disgust, was an ‘elocutionist from Toronto [who] smoked cigarettes and painted herself,’ and who introduced a camp doctor who supposedly gave ‘certain pills to girls who had made the mistake of indiscretion.’ The few college girls stuck together, appalled as things ‘degenerated,’ and even some decent girls were ‘ruined.’ The worst part, she concluded, was that these lower-class girls dared to call themselves ‘patriotic,’ a label she clearly thought should be reserved for the decent, sexually moral, and upright women of Canada.76

Miss Taylor’s apocalyptic version of things falling apart reflected a strong concern voiced by various religious and reform organizations that the wartime emergency also required the vigilant protection of the family and morality, including sexual purity. Because the war emergency unleashed strong anxieties about sexual laxity and non-conformity, mobilizing morality for war was just as important in the minds of many as mobilizing the raw power of labour for war production.

On the one hand, morality was associated with patriotism, loyalty to the empire, and the defence of Anglo-Saxon values in the face of the ‘Teutonic aggressors.’ Women who supported the war portrayed it as a just crusade; the national regeneration that they claimed the war would bring was moral regeneration. This was epitomized in the WCTU’s successful campaign against alcohol, deemed by the WCTU an even greater ‘scourge than war … or German bullets.’77 The morality of patriotism was lived out by many women in voluntary work. Women raised hundreds of thousands of dollars through imperialist organizations like the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire (IODE) or through the Red Cross; in 1914 alone the IODE contributed to the construction of a naval ship, a hospital wing, and many ambulances. As well as mobilizing their considerable financial power, these women gave unpaid, volunteer labour to the registration of citizens; to organizations like the Canadian Patriotic Fund; to the production of clothes, bandages, and other goods for the military; and to thrift campaigns. Some of these efforts clearly crossed class lines, drawing in white, Anglo, working-class women. Perhaps most important, these women became political allies for those waging the war. They aided recruiting efforts, declaring from public platforms that only the selfish women would ‘hold back their husbands, fathers and brothers,’78 while also publicly repudiating feminist pacifists, castigating them mildly as naive and misguided or more forcefully as ‘dupes’ of the enemy.79

The moral endorsement of prominent women was highly sought after by the ruling elite, hence Borden’s attempts to secure Nellie McClung’s support for the Wartime Elections Act. The government’s Women’s War Conference of 1918 represented a prime example of this mutually sought-after alliance. The attendance list was a who’s who of important farm and reform groups, though labour women, as well as those from non-Anglo communities, including Québécoise women, were noticeably absent. Delegates passed resolutions ranging from the control of food production and conservation to prohibition and industrial activity. They were most profuse in their thanks to the government for ‘taking them into their confidence’ and for placing one woman on the Registration Board. An NCW article even urged the government to consult with an appointed, not elected, ‘advisory board of women … with [a] strong magnetic woman [Emily Murphy] at the helm.80 Eager to assert their new political respectability, they also demanded reforms such as equal pay and a new federal children’s bureau.

It is hard to escape the conclusion, however, that the government got the better end of this political alliance. When the war ended, there was no children’s bureau; moreover, equal pay had never been a remote possibility in the government’s labour strategy, which had not even sanctioned ‘fair wage’ clauses in its munitions contracts. When women took seriously the government’s rhetoric about their new importance, lobbying in 1919 for a female delegate at the Versailles Peace Conference, Borden’s private response was revealing: ‘I cannot see any possible advantage in selecting representatives from [the women’s] societies mentioned…. I do not know of any work they could do if they came … I should prefer … not to take any action.’81

The absence of labour and non-Anglo women at the 1918 conference was a stark reminder that the women’s movement was not unified during the war. Indeed, some working-class women used the labour press as a vehicle to critique the prosecution of war, while the most radical socialist women challenged the war itself, indicting capitalism and militarism as the root causes of the unnecessary conflict.82 Linking ethnicity and class in their critiques, socialists like the fiery Helen Armstrong mounted a courageous critique of the government’s nativist internment policies, pointing to their cruel consequences for the ‘starving’ women and children of internees.83

These ethnic and class tensions and the very different conceptions of morality that shaped working-class and middle-class women’s sensibilities about war were manifested in other contexts, too. The hiring of women of ‘good pedigree’ as munitions ‘welfare supervisors’ reflected the understanding by government officials that women with high moral standards were needed to oversee working women’s less certain morals in a rough, masculine, working environment. This was made clear in 1918, when the Air Force wanted to use the services of the IMB welfare supervisor Mrs Fenton (who had actually been laid off) to oversee women in its employment, and the IMB agreed in order to prevent the taint of sexual immorality and the ‘cesspit’ of ‘public scandal’ from touching the Air Force.84

The perceived influx of women into new and masculine employments – even if it was very exaggerated – accentuated the anxieties of middle-class reformers about the sexual morality of working-class women. In Women’s Century, a prominent reformer explained with an anecdote. She was sitting on the streetcar, listening to girls from the factories, whose ‘careless, reckless’ approach to life and love indicated little respect for the ‘sanctity of marriage.’ These girls, living in a ‘feverish state of unnatural excitement and unrest all day’ and in the ‘darkened gloom’ of sensational movies at night were disturbing enough, but her second example was worse. A young woman, ostentatiously dressed in her new-found wealth, sat with her silk blouse unbuttoned, flirting with a young soldier. The only thing worse than her shockingly loose morals was her ‘designedly wicked … foolish temptation’ of this fine ‘specimen of young manhood.’ Similar concerns, of course, resulted in the creation of ‘hostess houses’ by the YWCA near military camps both to protect soldiers from predatory prostitutes and to keep young women from endangering their sexual virtue. ‘Girls and Khaki’ were a potentially lethal combination warned many writers; the ‘glamour of a uniform’ might lead to women’s easy abandonment of morality.85

Social workers and reformers repeatedly voiced their fear that delinquency and family upheaval might result when the patriarchal authority of men was transferred to the battlefront, though it was primarily working-class families that came under their critical view. Concerns about the morality of working-class wives also characterized the state and charitable aid (intended primarily to aid enlistment) provided for dependent wives of soldiers. The Canadian Patriotic Fund (CPF), Nancy Christie argues, reinforced at its ‘very basis the preservation of class boundaries,’ while simultaneously acting to ‘morally regulate’ women, through their ‘family visits’ inspecting women’s spending, behaviour and morals.86 CPF visitors had to ascertain if women were ‘worthy of assistance,’ properly searching for wage work to supplement their allowance, eschewing ‘wastefulness, luxuries and recklessness.’87 That this regulation was resented was evident not only in some oral recollections, but also in the more politicized columns of labour papers. In 1917 the Industrial Banner cautioned soldiers’ wives to beware of the ‘leading ladies,’ who would call and pretend interest in their welfare when they were interested only in securing their vote. These women are the wives of men making fortunes, while we suffer, scrape by and serve overseas, the same people who moralistically inspect your Patriotic Fund spending, claiming ‘[you] were not conducting yourself in a manner becoming a lady,’ daring to ‘go out to the movies rather than scrubbing floors.’88

The war thus engendered a rhetoric of regeneration, but also heightened anxieties about degeneration. Nor was existing legislation on morality perceived to be adequate. In 1918 the federal government pushed through a criminal code amendment making it a crime to have a home ‘unfit for a child’ because of the parents’ ‘sexual immorality, habitual drunkenness or any other form of vice.’ A few years after the war, prominent lawyer and child-saver W.L. Scott explained that he had drafted the bill for the government because it was found that there were ‘many instances’ where the father went to the front and the mother and some ‘scoundrel’ then ‘lived in adultery’ to the ‘great detriment of the child’s morals,’ though the problem of adultery was not confined to these families.89 Similarly worded legislation in Ontario was used to prosecute parental neglect and ‘immorality,’ sometimes even women who ‘deserted’ homes they claimed were violent.90 Debating the bill in 1918, some parliamentarians noted that the bill reflected the intensified moralism of the war atmosphere, and they worried its vague scope would lead to ‘mischevious’ and ‘extreme’ prosecutions. It nonetheless became law, and its use in the next decades, particularly against working-class and poor families, confirmed some of these fears.91

This was simultaneously a period of intense legal prosecution of sexual ‘immorality,’ especially the sale of sex. In 1918 a federal bill was enacted to criminalize those who falsely registered as man and wife in hotels and boarding houses, and the age of consent for girls was raised. As a response to the highly organized social purity campaigns, prostitution laws were extended in 1913 and 1915, creating new offences such as living off the avails of prostitution and tightening offences such as procuring. Public investment in the idea that white slavery and prostitution threatened both the home and young innocent women resulted in increased policing; in the first two years of the war, John McLaren notes, the conviction rate for bawdy-house arrests across Canada was two to three times what it had been in the early years of the century.92

NCW and WCTU women clearly saw the war as the vehicle for needed purification, ridding Canada of alcohol, prostitution, venereal disease, and immorality. This campaign was sometimes described in eugenic and ethnocentric language, stressing the value of Anglo-Saxon culture and the need to limit reproduction of the eugenically ‘unfit.’ Wartime pressures also led to more public discussion of venereal disease, and under pressure from medical, reform, and military forces, provinces took action through Public Health Acts, while tough, even draconian, controls were implemented through the new federal Venereal Diseases Act of 1918, a measure applauded by those women who feared VD as a scourge against womanhood.93 These anti-VD campaigns, however, were also shaped by class assumptions. Just after the federal VD law was passed, Mark Irish suggested to Flavelle that more anti-VD education needed to be done in ‘large industrial works,’ such as munitions, for ‘both men and women of the lower order grades of life recognize only one penalty as arising from sexual intercourse, namely pregnancy,’ while the greater evil, VD, was little understood by ‘these workers.’ Although he saw this VD issue as a ‘sidelight’ to his major task of dilution, Irish equated such moral education directly with the work of the female welfare supervisor, Mrs Fenton, who had supposedly dealt with a number of ‘unfortunate’ cases of moral downfall.94 It is not surprising that, even after the war, those women most likely to be incarcerated in reformatories under the VD act were poor, working-class women.

The anti-VD campaign was linked to another moral project of the war years, namely, the creation of voluntary female police patrols, whose job was to ‘rescue’ women by policing urban spaces and preventing – or directly halting – sexual immorality. Responding to the ongoing lobbying of middle-class reformers, police matrons had been hired in some Canadian cities, but the war ‘brought to a climax’ an intense campaign to integrate women into policing, though primarily in a separate sphere dealing with domestic and moral issues. Drawing on the model of British patrols, the NCW repeatedly extolled their value as a protective measure against VD and to stop the ‘charity girl, patriotic prostitute and incorrigible girl from becoming a professional prostitute.’95 The patrols suggested that the moral problem of the day was not only sex for sale but sex given away, reflecting the increasing promiscuity of women. As the Toronto police chief grumbled during the war, prosecutions of ‘houses of ill fame’ had declined, but this decrease did not ‘necessarily indicate the morality of the city had improved, but merely that sexual intercourse is indulged in other ways in other places beyond the reach of the police.’96 In 1918 voluntary female patrols were set up in Toronto and Hamilton, and Montreal hired its first policewomen, whose work, as Tamara Myers shows, was hampered in part because the working-class women they patrolled sometimes resented this moral surveillance and intervention.97 As in Britain, the means for ‘women to move into an area of masculine authority’ was accomplished by cooptation into police ideology and culture, and the exercising of arbitrary power over other women.98

The mobilization of morality for war therefore had both coercive and class-specific consequences, whatever the good intentions proclaimed by those doing the moralizing. Some working-class families, embracing the dominant notions of sexual respectability, were disturbed by their daughters’ apparent embrace of ‘immmorality’ during the war and endorsed this coercion. In one court case, ‘Katie,’ a young woman from small-town Ontario, ran away to Toronto and was charged with vagrancy; she was then sent to the reformatory to be treated for VD. Even after release, she wanted to stay in Toronto, to the consternation of her guardian siblings. Her brother, serving overseas, intervened, writing that he wanted her ‘in an institution until he [came] home to look after her and take charge.’ The one advantage of the war for some incarcerated women was the difficulty of deportation; when a recent Welsh immigrant working in munitions was sentenced to the same reformatory, she escaped deportation because no ship could be found to take her home.99

There is also some evidence that the women and their families who were accused of immorality either resented the notion that their class position made them less respectable or embraced different standards of dress, dating, and sexual and familial mores that challenged the values of middle-class sobriety and sexual purity. Soldiers might also defend their partners against the moral approbation of the legal authorities. When one soldier’s wife was charged with performing an illegal abortion on a friend, she was incarcerated, only to give birth herself to an illegitimate child. The reformatory superintendent and the local Children’s Aid Society differed over whether the child should be adopted as soon as possible or the woman should be ‘compelled to nurse it as long as possible’ (probably to atone for her shame), but both agreed she had to admit her ‘improper actions’ and hope that her husband would ‘protect’ her when he returned. However, it ‘appears from his letters,’ said the superintendent with some surprise, ‘that he will forgive her.’ A younger woman, arrested on street-walking charges and sent to the reformatory, secured even more adamant support from her soldier fiancé, who wrote to the superintendent from a nearby military hospital, begging to see his ‘Violet,’ at least once a month. ‘I looked into this matter and I don’t think Violet is so bad as things look, therefore I’m going to stand by her. And I will tell the world I’m going to marry her as soon as she gets out,’ he declared.100 His loyalty, especially given the charge, may have been somewhat unusual, but it does suggest that the moral surveillance of women so keenly embraced by some reformers during the war did not meet with the approval of those women and their families most likely to fall under the gaze of roving morality patrols.

In 1918 the Ontario government prepared public circulars encouraging women to leave war-related jobs. Yet, there is little evidence that they were actually disseminated widely – probably because the number of women who had occupied ‘men’s’ jobs during the war had never been large. The greater historical value of these documents lies in their articulation of the prevailing gender ideology, promoted by the state but with a broader resonance as well. Sustaining the image of the patriotic war worker, the circulars declared that many women had worked as a patriotic ‘duty’ or because they found it ‘interesting,’ and now some did not want to ‘give this up and go back to housekeeping.’ The problem was to be solved, however, by employers who appealed to women’s patriotic deference to the soldier’s need to support his family and reminded women that this work was not their right. The publicity left the door open for women ‘who needed to work’ to continue to do so, but not in the jobs that men claimed as theirs.101

The gender conflict that some, like R.B. Bennett, had feared, however, did not preoccupy the state in the aftermath of war as much as the class and ethnic divisions. Tensions – between men and women, within families separated by war – undoubtedly existed in the wake of a perceived blurring of traditional gender roles, and perhaps they were negotiated by the emphatic post-war assertion of an ideology of separate spheres.102 However, the more visible political fallout from the war was articulated in the conflicts that erupted as part of the country’s ‘workers’ revolt’ and the state’s anti-ethnic Red Scare. As labour historians have argued, this revolt was already evident during the war, but it erupted with full force in 1919.103 Before 1919 women had already taken sides. When Borden was asked by military figures to offer some recognition to the pro-war Women’s Volunteer Reserve in Winnipeg, he was reassured that ‘these were a good class of women’ because during the recent civic strike they had acted as strike-breakers, taking over telephone operators’ jobs.104 A year later, women would again be sharply divided during the strike, highlighting divisions in no way limited to the west. In Ontario, there emerged a new political organization of women from trade unions, union auxiliaries, and label leagues, quite self-consciously forming their ‘own national council of women’ distinct from the NCW, and in the Maritimes previously unorganized women wage-earners in textiles, candy-making, and service work took an active part in the 1919 labour revolt.105

This was not the historical version of war that many feminists had carefully crafted. Nellie McClung’s Next of Kin and the NCW’s Women’s Century claimed that war had created a new sisterhood, drawing women together, erasing artificial differences of wealth and status.106 Yet evidence suggests otherwise. The women who testified before the federal Mathers Royal Commission on Industrial Relations in 1918 and 1919 were more concerned with a ‘living wage’ than moral regeneration; they spoke of the material struggles of homemakers who could not support their families on soldiers’ pensions, of rising food prices, and of women’s marginal wages. Working-class children, testified Calgarian Mary Corse, were forced into early work, denied an education, let alone the ‘better things in life, like music.’ ‘If I go to the corner with a tin cup and beg for some bread for my children, I am arrested as a vagrant,’ she continued; ‘another woman can stand on the corner with her furs, boots and corsage bouquet and collect nickels for the veteran … and she is commended for her petty little scheme. Those are inequalities.’107

As a reflection of working-class views, this historical source also is problematic, since the hearings attracted the politicized, vocal, and socialist-minded women. Nonetheless, their angry indictment of capitalism and their passionate commitment to social transformation indicate how the war crisis might accentuate class differences or speed the radicalization of some women. The one middle-class reformer who testified, Rose Henderson, provided a symbol of political change. A well-educated probation officer with the Montreal Juvenile Court, Henderson declared in Women’s Century in 1918 that labour and capital should seek a rapprochement for the good of humanity, but by the time she testified in 1919, Henderson had cast her lot with working-class and socialist organizations, perhaps losing her job because of these allegiances. When urged by the Mathers Commission to comment on the alien ‘problem,’ she responded with the radical quip, ‘there is no alien in my vocabulary.’ Nor were her other demands mild: ‘remove the profiteers … abolish child labour … nationalize [medicine]’ she declared. ‘The real revolutionist’ at this moment, she told the commission men, perhaps thinking of her own transformation, ‘is the woman.’108

Rose Henderson’s call to socialist arms has not been the dominant historical view of Canadian women and the First World War. The myth of unity, patriotism, and homogeneity, as Vance points out, was remarkably resilient in the interwar period, an observation that extends to much feminist writing as well. In part, the unfolding myth of the war as an engine of progress and a positive watershed for women was shaped by the inevitable hegemony of those with more power to shape public images, symbols, and consciousness; this patriotic memory of war was certainly actively promoted by some elites in the face of evidence of post-war class conflict.109 As Veronica Strong-Boag perceptively notes, the post-war political realignment revealed that Canadian society could ‘benefit its elite and reward the women as well as the men – though not to the same extent.’110 At the same time, the positive image of the war was probably integrated into popular consciousness because it offered comfort in the face of loss and, for women, eager anticipation of increasing gender equality and progress.

Critical reappraisals of the war have not upheld this image of progress, especially for women workers – though it is entirely possible that a future generation of feminist historians will challenge our definitions of ‘progress.’ Working-class women experienced not massive shifts in the technology of work, but an acceleration of existing trends, such as the feminization of clerical work. The ideal of a male breadwinner and dependent family persisted in post-war social welfare policy, and both work and family were affected by heightened moral and sexual anxieties unleashed by the war, with working-class women those most often targeted as potential dangers to the sexual status quo. The war also accentuated existing class and ideological tensions among women, stimulating the autonomous political organizing of socialist, labour, and pacifist women. The memory of war for these women was summed up in The Magpie by Jeannette, the woman radicalized by the war. ‘The soul of the world’ she told her friend Craig ‘was lost’ in the mud of France and it was up to the women to retrieve it. From the ‘bitterest depths of her heart’ she announced that the world needed to be ‘turned upside down,’ with the ‘pampered daughters’ of the rich forced to work for starvation wages: ‘My only hope now is that those who are down now may have a chance to get up and enjoy the pleasures of life before the end comes.’111

1 Betsy Struthers, ‘The Bullet Factory,’ Censored Letters (Oakville: Mosaic Press, 1984).

2 David Carnegie, The History of Munitions Supply in Canada (London: Longmans, Green, 1925), 257.

3 This is relayed through interviews in the recent documentary film, And We Knew How to Dance: Women and World War I, directed and researched by Maureen Judge (Ottawa: National Film Board of Canada, 1993).

4 Joan Scott, ‘Rewriting History, ‘in Behind the Lines: Gender and the Two World Wars, ed. Margaret Higonnet et al. (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1987), 23.

5 This complexity, for instance, was evident in the English-language labour press; some papers announced their support for the lofty aims of the war, even if they condemned its method of prosecution, particularly the conscription of men, but not wealth. The majority of the 8,579 internees were Ukrainians. See Peter Melnyck, ‘The Internment of Ukrainians in Canada,’ and Donald Avery, ‘Ethnic and Class Tensions in Canada, 1918–20,’ in Frances Swyripa and John H. Thompson, eds, Loyalties in Conflict: Ukrainians in Canada During the Great War (Edmonton: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, 1983), 1, 77–99; Gregory S. Kealey, ‘State Repression of Labour and the Left in Canada: 1914–20: The Impact of the First World War,’ Canadian Historical Review 73, 3 (1992), 281–314. Owing to a lack of access to non-English language sources, I have concentrated more on class than on ethnicity in this chapter, but there is ample evidence that ethnicity and culture were also major dividing points for women – with the best documented being French/English divisions.

6 Vance, Death So Noble: Memory, Meaning and the First World War (Vancouver: UBC Press 1997).

7 Francis Early, A World without War: How U.S. Feminists and Pacifists Resisted World War I (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1997), 91–2.

8 Nellie McClung, Next of Kin: Those Who Wait and Wonder (Toronto: T. Allen, 1917), 62.

9 The poster is reproduced in Desmond Morton and Cheryl Smith, ‘Fuel for the Home Fires: The Patriotic Fund, 1914–18,’ The Beaver 75, 4 (1995), 12–19.

10 Early, A World without War. On gender and war see also Cynthia Enloe, Does Khaki Become You? The Militarisation of Women’s Lives (London: Pluto Press, 1983).

11 Women’s Century (hereafter WC) August 1916.

12 Globe and Mail, 28 February 1918.

13 Industrial Banner (hereafter IB), 26 November 1915; 17 September 1915.

14 Interviews with Margaret Hand, Martha Davidson, and Jake Foran, in Daphne Read, ed., The Great War and Canadian Society: An Oral History (Toronto: New Hogtown Press, 1978), 217, 188, 213.

15 Parlby’s concern was that a younger generation, less interested in public service than in simple rebellion, did not understand what to do with their ‘new freedom.’ C.B. Robertson, ‘The Challenge of Freedom,’ Chatelaine, November 1929, 10; for similar concerns, see A.N. Plumptre, ‘What Shall We Do with “Our” Flappers?’ Maclean’s, 1 June 1922, 64–6.

16 Globe and Mail, 13 November 1928. Both R.B. Bennett and Arthur Meighen loaned (and lost) money to the company for this nationalist endeavour. See Peter Morris, Embattled Shadows: A History of Canadian Cinema, 1895–1939 (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1978), 72. My thanks to Cathy Yager for these references.

17 Salverson, Viking Heart (New York, 1923). Even still, as Jonathan Vance points out in Death So Noble, her sacrifice helped to underscore the image of a new nation in which the immigrant son was one with the native-born son.

18 MacLennan, Barometer Rising (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1958).

19 Durkin wrote The Magpie in New York City in the bohemian 1920s, of course, which may explain why these characters appeared so unconventional (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1974).

20 J.G. Sime, ‘Munitions!’ in Sister Women (London, 1919); reprinted in Sandra Campbell and Lorraine McMullen, eds, New Women: Short Stories by Canadian Women, 1900–1919 (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press, 1991), 332. As Campbell points out, Sime’s more candid and ‘liberal’ views on sexuality distinguished her from other middle-class feminist writers at the time.

21 I. Andrews, Economic Effects of the War on Women and Children in Great Britain (New York: Oxford University Press, 1923), 174.

22 Anne Anderson Perry, ‘Is Women’s Suffrage a Fizzle?’ Maclean’s, 1 February 1928, 5–7.

23 Over the last thirty years, historical writing has reflected the wider concerns of Canadian feminist enquiry. Authors first explored wage labour and politics, drawing on both Marxist and feminist analyses, proceeded to questions of social welfare, and have alluded more recently to culture or enquiries into wartime moral regulation, though studies stressing ethnicity and race are less prevalent. For one of the first reinterpretations of the war see Ceta Ramkhalawansingh, ‘Women during the Great War,’ in Janice Acton et al., eds, Women at Work: Ontario, 1880–1930 (Toronto: Women’s Press, 1974), 261–309. On politics, see Carol Bacchi, Liberation Deferred? The Ideas of the English-Canadian Suffragists (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1983). For a different view that stresses the importance of the war for women’s suffrage, see John Herd Thompson, The Harvests of War: The Prairie West, 1914–18 (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1978). In later works pacifism and socialist women have been explored: Barbara Roberts, A Reconstructed World: A Feminist Biography of Gertrude Richardson (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1996); Thomas Socknat, Witness against War: Pacifism in Canada, 1900–45 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1987); Linda Kealey, Enlisting Women for the Cause: Women, Labour and the Left in Canada, 1890–1920 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998). Social welfare has been examined by Margaret McCallum, ‘Assistance to Veterans and their Dependants, Steps on the Way to an Administrative State,’ in Wesley Pue and Barry Wright, eds, Canadian Perspectives on Law and Society: Issues in Legal History (Ottawa: Carleton University Press, 1988), 157–77; Nancy Christie, Engendering the State: Family, Work, and Welfare in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2000), chap. 2. Regulation has been analysed by Tamara Myers, ‘Women Patrolling Women: A Patrol Woman in Montreal in the 1910s,’ Journal of the Canadian Historical Association 4 (1993), 229–45.

24 The claim on the part of many patriotic women that they had abandoned the suffrage cause for the duration was not entirely true. Some pro-war suffragists like the NEFU did halt their open campaigning, but their pens did not stop for a minute, and every column, speech, and recruiting opportunity they could, they reminded men that they were now proving their loyalty to the state – a clear plea for the vote.

25 Robert Craig Brown, Robert Laird Borden: A Biography, Vol. 2, 1914–37 (Toronto: Macmillan, 1980), 100.

26 Cleverdon, The Women’s Suffrage Movement in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1974), 7. For quotes see Rose Henderson in WC, Jan. 1919.

27 Bacchi, ‘Liberation Deferred?’; Brian Tennyson, ‘Premier Hearst, the War and Votes for Women,’ Ontario History 57, 3 (1965), 115–21.

28 Ramkhalawansingh, ‘Women During the Great War,’ 74, 261; Veronica Strong-Boag, The New Day Recalled: Lives of Girls and Women in English Canada, 1919–39 (Toronto: Copp Clark, 1988).

29 This number does not make sense in comparison with numbers given by the Trades and Labour Branch of the Ontario government, Enid Price’s study of Montreal discussed below, or even the Canadian Annual Review.

30 Canada, Imperial Munitions Board, Women in the Production of Munitions in Canada (Ottawa: Imperial Munitions Board, 1916).

31 For this argument relating to Britain, see Deborah Thom, Nice Girls and Rude Girls: Women Workers in World War I (London: I.B. Tauris, 1998), 87–90.

32 Feminist iconography has drawn on images of women’s non-traditional work, such as that of the later Rosie the Riveter. Another example is the poster (showing an Asian woman driving a tractor) that I prepared with Kate McPherson for the book, Bettina Bradbury et al., eds, Teaching Women’s History, Challenges and Solutions (Edmonton: University of Athabasca Press, 1995).