DESMOND MORTON

During the First World War, more than a fifth of the 619,586 men who joined the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) were married. Others left orphaned children, elderly parents, and other dependants.1 A few left families to rejoin other armies – British, French, Belgian, Serbian, Italian, even Russian – in which they had reserve obligations. Still others slipped back to Germany or the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

In earlier wars, soldiers’ families were often among the sad detritus of a campaign: women and children abandoned to the charity of family and friends, or camp followers at the mercy of weather or the fortunes of armies. The nineteenth-century advent of mass citizen armies and a Victorian determination to remedy evils ensured that by 1914, while soldiers’ families might suffer, they would not generally be neglected. Morale at the front and civil order behind the lines depended on an adequate response to an obvious need. In Canada, soldiers’ families would inspire the largest single charity Canadians had yet created, the Canadian Patriotic Fund (CPF). In a celebratory memoir, some recent papers, and a master’s thesis the role of the ‘Patriotic’ has been explored.2 The focus on the fund during the First World War obscures the fact that the Canadian state and soldiers themselves were larger sources of financial support to most military families than the CPF. Indeed, the fund and the Militia Department were administrative partners in regulating and informing a system that was always complicated by moral and social assumptions as well as by the vagaries of human behaviour.

By creating a separate and ostensibly private organization to assist in meeting the needs of its soldiers’ families, Sir Robert Borden’s Conservative government relieved itself of both expense and a sensitive responsibility. Headed by a Conservative MP who professed to speak for the fund’s largest donors, the ‘Patriotic’ exercised a powerful influence on the living standards and regulation of soldiers’ families, favouring some over others, disciplining those who deviated from its norms, and shaping the behaviour of women who found themselves, in their husbands’ absence, subject to social engineering.

When the government accepted an obligation to offer additional support to a soldier’s dependants, who should qualify? A widowed mother was an obvious beneficiary, but what about an elderly and invalid father or a sister of working age who had depended on her brother to save her from the labour market? In peacetime, a soldier was treated as a marginal member of society. How far could that status improve when he risked his life for king and country? What about women the British army already described as ‘unmarried wives’? No law compelled a man to support a woman who was neither a faithful wife nor a mother. Was a government that compelled a husband to contribute half his pay for her benefit also obliged to be his agent in protecting his interests and those of his children?

At dawn on 4 August 1914 Canadians found themselves officially at war with Germany. During the three previous days, hundreds of French and Belgian reservists had reported for duty, and a voluntary organization to care for their families had begun to take shape in Montreal’s French-speaking community.3 Within days of the outbreak, concern for soldiers’ families became a Canada-wide concern. By war’s end in June 1919, 619,636 men and women had been enrolled in the Canadian Expeditionary Force and 425,821 had been sent overseas, far from those who depended on them for income support. Among them were 88,347 married men. Other soldiers were the sole support of elderly parents or younger siblings. The 3,776 widowers included many with dependent children.4

In 1914 Canada had inherited some practices and precedents for the problems of soldiers’ families, but they were known to only a minority of the few Canadians who had involved themselves with the pre-war militia and Canada’s tiny permanent force. During his two weeks of annual camp, a militia private enjoyed ‘rations and quarters’ – the traditional camp fare of beef stew and fresh bread, a leaky tent and threadbare army blankets – and earned between 50 and 75 cents a day during the camp, depending on his length of service and musketry skill. Permanent-force soldiers earned less, though they could depend on barracks and meals during the winter, while unskilled labouring men experienced high unemployment and short commons. If such soldiers intended to marry, the King’s Regulations and Orders for the Canadian Militia required him to obtain his commanding officer’s permission. The commanding officer ascertained that the soldier was financially able to support a wife, and that ‘the woman is a desirable character.’5 The wife of an approved marriage was included in the ‘married roll’ and became eligible for married quarters – two or more rooms in barracks, depending on rank, family size, and availability – or a small allowance ‘in lieu.’6 The family was entitled to quarters or the allowance even if the soldier-husband was absent on duty. The regulations restricted the permissible ‘married establishment’ of a unit to 12 per cent of its total strength until 1914. To encourage ‘steadier’ old soldiers, the regulations were then changed to allow the inclusion of all senior non-commissioned officers on the ‘married roll,’ but only 8 per cent of lower ranks.7

Until the 1900s civilians administered the militia’s stores and finances. ‘Departmentalization’ began in 1900 with an Army Medical Corps and Army Service Corps. In September 1905 civilian clerks were transferred to a Corps of Military Staff Clerks, composed of non-commissioned officers familiar with regulations and routine. A Canadian Army Pay Corps (CAPC) followed sixteen months later, in ten detachments located wherever permanent force units were stationed. In August 1914 the entire corps consisted of fifteen officers.8 A peacetime militia unit appointed its own paymaster, often a local bookkeeper or accountant who accepted an honorary commission in return for a few days of preparing the pay list after the annual training camp. Few militia paymasters could easily abandon their civilian careers in 1914; even fewer would bring extensive knowledge of militia regulations. However, Canada’s pre-war mobilization plan provided for units to recruit and organize in their home districts: the CAPC would collect and train unit paymasters and pay sergeants, so that when the expeditionary force mustered at Valcartier or Petawawa, pay staff would rejoin their units, ready to exploit their new expertise in military regulations, forms, and jargon. It was not perfect, but no one had a better idea.

Within hours of the British declaration of war, the minister of militia, Colonel Sam Hughes, had scrapped the mobilization plan and despatched telegrams to militia colonels to bring hosts of volunteers to Valcartier, the new militia camp outside Quebec City. Officials struggled to catch up. In further telegrams he explained that soldiers were to be enlisted from 12 August at militia rates of active service pay. Local contingents made their way by rail to Valcartier, where, in an atmosphere of high enthusiasm and administrative chaos, they were formed and reformed into artillery brigades, cavalry regiments, artillery batteries, and, ultimately, seventeen infantry battalions, not to mention the other elements of a standard British-style infantry division. On 22 September the volunteers formally switched from the militia to the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF).

Material considerations weighed lightly on most of the men who crowded armouries and recruiting centres in the hot August days. Canada was in the grip of a severe depression, and many volunteers had been unemployed. Seventy per cent were British born, many of them recent arrivals. Joining the CEF, cynics claimed, guaranteed a cheap passage home to England and away from signs warning: ‘No English need apply.’ Most volunteers, and ideally almost all of them, would have been carefree bachelors, with siblings enough at home to support infirm and indigent parents and other family members. In camp, men with money to spend found clusters of makeshift shops selling food, soft drinks, socks, sweaters, and anything else a soldier might want, short of liquor. A devout prohibitionist, conscious that wives and mothers were worried about the moral health of lonely sons and husbands, Colonel Hughes kept the vast camp dry, though Quebec City’s bars and taverns were close at hand for those permitted to go on leave. By 3 September CEF pay scales were set. For a single man, with ‘all found,’ they were generous. A soldier was also assured that he could assign up to four-fifths of his monthly pay to relatives.9

Colonel Hughes’s call had included married men. The force badly needed trained and experienced officers and non-commissioned officers, and British-trained veterans to stiffen the ranks. Some officers moved their families to the city to enjoy their last few days together. Hughes, a committed feminist and brother of one of Canada’s leading proponents of female suffrage, insisted that any married volunteer must have his wife’s written permission to enlist.10 Before the contingent sailed on 1 October no less than seven officers and 372 other ranks were sent home after a parent or wife protested. Others, to avoid such a humiliating fate, forgot to report their wedded state.11

By no means all wives got their husbands back. Mrs Gerald Wharton was stranded in Buffalo on 9 August after a fight with her husband: ‘I told him I would be better off without him for I worked most of the time to support my child and I think you will agree that I am better off without him but I do not think that he should go free and me be tied down to work to keep myself and his child as well as mine.’12 Mrs Roy Hunter of Kamloops said goodbye to her husband, who ostensibly left to join the First Contingent. Mr Hunter kept on travelling. His wife appealed in vain to the army.13 Mrs Harry Mortimer also got little satisfaction when she saw a picture of her husband with the Canadian Engineers. She insisted that Harry was thirty-five, had married her in 1907, and had left her with three children, but Harry’s brother insisted that the soldier was only twenty-three. ‘So what do you expect four people to starve since my husband enlisted’ demanded Mrs Mortimer, ‘and if I don’t get anything out of this I will publish it in the Papers showing where the public money is going to.’14

Table 8.1

The Marital Condition of the CEF

|

||||

Status |

Married |

Single |

Widower |

Total |

|

||||

Outside Canada |

|

|

|

|

Officer |

7,375 |

15,353 |

118 |

22,843 |

N/S |

42 |

2,354 |

15 |

3,643 |

Other ranks |

80,930 |

314,762 |

3,643 |

399,335 |

Total |

88,347 |

332,466 |

3,776 |

424,589 |

Inside Canada |

|

|

|

|

Officer |

1,718 |

1,590 |

15 |

3,323 |

N/S |

5 |

436 |

2 |

443 |

Other ranks |

36,000 |

153,280 |

2,001 |

191,281 |

Total |

37,723 |

155,306 |

2,018 |

195,047 |

Total |

|

|

|

|

Officers |

9,093 |

16,940 |

133 |

26,166 |

N/S |

47 |

2,790 |

17 |

2,854 |

Other ranks |

116,930 |

468,042 |

5,644 |

590,616 |

Total |

126,070 |

487,722 |

5,794 |

619,586 |

|

||||

Source: NAC, Duguid Papers, vol. 1.

Soldiers and their families were early objects of concern. Hardly had the war begun than prominent citizens in most Canadian communities had met to consider what could be done for them. Confident that the war could last for only a few months, federal, provincial, and many municipal governments, railways, banks, and other major employers promised volunteers that their civilian wages would continue ‘for the duration’ and their jobs would be available on their return. On 18 August a meeting was formally convened in Ottawa by the governor general, the Duke of Connaught, to revive the Canadian Patriotic Fund, used in previous wars to meet a variety of needs, from pensions and medical treatments to a medal for the War of 1812. This time, as designed by Herbert Ames, Conservative M.P. for Montreal-St-Antoine, wealthy heir of a large manufacturing business, and an amateur social observer, the ‘Patriotic’ would serve only the needs of soldiers’ families. When the war emergency session of Parliament met on 21 August, legislation for the fund was the second order of business. On 25 August the duke became president and Ames the honorary secretary and de facto manager.15

The government recognized that it could not lay the whole burden of family support on charity. Two precedents were available: families of permanent force soldiers continued to enjoy quarters and subsistence or the financial equivalent, and the British announced a separation allowance of 15 shillings a week to soldiers’ families.16 On 4 September 1914 the cabinet approved a similar ‘separation allowance’ (SA) for families of CEF members. At rates ranging from $20.00 for the wife of a private and $25.00 for a sergeant’s wife to a maximum of $60.00 a month for a lieutenant colonel’s lady, separation allowance would be paid monthly. To avoid overpaying those who continued to collect wages from a peacetime employer, it was stated that other income ‘may be deducted.’17

By early September, a private’s wife was assured of half her husband’s pay (if he bothered to assign it), $20.00 in separation allowance, plus whatever the Patriotic Fund might grant her and her children. Though the CPF insisted that its branches were autonomous, its national officers soon agreed on a maximum scale, depending on the number of children, that limited a family to $30.00 a month in eastern Canada and $40.00 a month in the west. The Montreal branch decided that a woman needed $30.00 per month to live, a child from ten to fifteen years needed $7.50, from five to ten, $4.50, and under five only $3.00. A mother with a child in each age group needed $45.00 a month. With $20.00 of separation allowance and no other earnings, she would receive $25.00 per month from the fund (assigned pay would be ignored). A British reservist’s wife, with only $5.00 from her husband and British SA of $16.68 for herself and a child, needed $27.90.18 The benefits might seem meagre to a middle-class family, but a working-class mother who had lived through two years of economic hard times would feel well off. As Private Frank Maheux of the 21st Battalion assured his ‘poor Angeline,’ it was more than the $22.00 he would have sent home from a logging camp.19

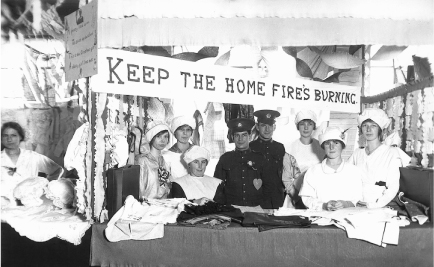

Women hold bazaars for war aid, ca. 1914–16 (City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244, Item 872)

But what if the money did not come? Across Canada, local Patriotic Fund committees took weeks to organize and even longer to gather funds and distribute them. The Montreal branch, Ames’s model for the CPF, accumulated 125 requests by 24 August, but its week-long ‘Lightning Campaign’ took until mid-September to organize.20 Meanwhile, months passed without separation allowance cheques. Wives were obliged to fend off landlords, extend their ‘tick’ at the local grocery store, and drain away their scarce savings.

What had gone wrong? Simply put, Colonel Hughes had derailed the Pay Corps’s plan to train wartime staff. When Lieutenant Colonel W.R. Ward, four CAPC officers, and seven military clerks reached Valcartier in late August, they found a military chaos. Without formed units, no one could appoint paymasters, much less begin the documentation on which pay and allowances were based. Once a unit’s commanding officer was approved by Hughes, he might find a paymaster – sometimes an officer unfitted for more demanding work – and a staff that reflected the CEF’s low level of literacy and bureaucratic experience. Even after units were authorized, their composition kept changing. Soldiers remustered, officers were promoted and demoted, and infantry battalions were switched from eight companies to four companies and back again. Officers ambitious enough to start documentation merely had to do the work over again.

The challenge of arranging assigned pay (AP) or approving SA was too complex for Valcartier. Was it a task for a soldier’s unit, for headquarters in Ottawa, or for some authority in between? If a soldier died or deserted, his pay ended, but what if his family continued to receive cheques? Who would recover the public funds? One theme was clear from the flood of administrative directives: a paymaster or commanding officer who authorized an improper payment would pay for it from his own pocket – and worse. All rules encouraged caution. All that Ward and his CAPC officers could manage was to pay all soldiers up to 21 September, the date when they became part of the CEF. When the First Contingent left for England at the end of September, confessed the author of the Official History: ‘[a]ssignments of pay to families or relatives and establishment of claims to separation allowance were matters which in the majority of cases were still unsettled.’ Not until December 1914 were SA cheques worth $61,815 put in the mail.21

Though Ward implored his novice paymasters to complete documentation during the two-week voyage to England, even with calm weather some of his subordinates proved unequal to the task. ‘It is terribly discouraging to me to realize that all the work I have done in the last few months and one’s best efforts are defeated by the neglect of other people.’22 Ward spent his own voyage compiling a set of financial instructions for the CEF, spelling out duties of paymasters, rates of pay, and accounting procedures. This material was rushed into print in England as the first stage of training the pay organization. The work continued in England, initially in clear, pleasant weather, then under the endless, cold, driving rains that marked the CEF’s first winter. Attestation papers were barely complete and verified before the Canadians left for France at the end of February 1915. Only then could he withdraw unit pay sergeants for training.23 Captain C.M. Ingalls, a CAPC officer and twenty-three-year militia veteran, crossed on the Franconia to find himself and six clerks in a fourteen-square-foot hut on Salisbury Plain, with the task of creating 33,000 pay accounts for the First Contingent. He insisted on moving to a large attic in Salisbury and finally set up an office in London. There he wrestled with record-keeping for a force that included 287 Smiths, many of them named John. To help, he was sent five officers who knew nothing of accounting and a civilian accountant who, he complained, ‘could not and would not interpret military regulations.’24 By August 1915 the Canadian Pay and Record office in London had grown to 740 personnel with fourteen branches, including distinct Separation Allowance and Assigned Pay branches. Divided that month, the separate Pay and Records offices had grown by September 1916 to a combined strength of 2,841 soldiers and civilians.25

Only in 1917 was any of this explained to Canadians. In 1914 Valcartier was described as a model, and no one was allowed to know that the professionals might have handled matters better. The plight of penniless wives and mothers was no fit counterpoint for the national patriotic chorus. Few editors were eager to rain on any parades. Northern Ontario’s Haileyburian was an exception, praising the Patriotic Fund but denouncing Militia Department red tape. One wife in the Ontario mining community had burned her furniture for heat; another was in an asylum and her four children were scattered.26 In Cape Breton, the former mayor of Glace Bay made it his patriotic duty to visit soldiers’ wives and report their grievances to the Militia Department by collect telegram until he was commanded to stop.27

Nor did all the fault lie with the CAPC. John Clovis Martin enlisted as a widower and assigned his pay to another woman. The real Mrs Martin wanted it back. Howard Ferry’s mother demanded his support, but it took weeks to locate which battalion Ferry had joined. Wesley Peters left his child with a woman when he joined the First Contingent. ‘This man is an Indian,’ a CPF investigator scornfully reported, ‘and, evidently, he did not know enough to apply for any allowance for his mother.’28

Recruiting for a Second Contingent began in October. Early in November, the Militia Department tried to avoid administrative delays by sending an immediate $20 payment whenever a separation card had been received, regardless of rank.29 Wives entitled to more soon expressed their grievances, but a final settlement of arrears was possible only in January 1915.30 A flood of correspondence developed over early discharges, changes of address and rank, and proof of identity for foreign-born recruits. ‘Do not pay Separation Allowance to wives of Russians,’ commanded J.W. Borden, the accountant and paymaster general, ‘unless proof of marriage is produced.’31

Separation allowance had been launched with a brief order-in-council. It did not stay simple. Acting for an absent Colonel Hughes in October, Sir James Lougheed reported the plight of widows ‘whose sons were sole support and went to the front.’ His cabinet colleagues dutifully agreed that ‘families be considered to include such.’ A month’s reflection also convinced ministers that, except for pay from the federal or provincial governments, ‘other income’ should not be deducted.32 Private employers were unlikely to continue their generosity if it was penalized.

Harried officials who devised the separation allowance had little idea of the complexity of family relations in 1914. Initially, Militia Department officials refused to countenance common-law relationships and demanded documented proof of marriage. Widowers were allowed SA for their children but only if the latter were obviously too young for employment (initially under fourteen for boys and sixteen for girls, raised in 1915 to fifteen and seventeen, respectively) and if they had a defined guardian. Divorce in 1914 was scarce and costly, but separations were more common. Could a soldier apply for SA to meet his support payments? Militia Department lawyers approved – if the payments were court ordered. A widowed mother’s sole support must be unmarried – one man might support two parts of a family, but not with SA – and the widow must indeed be solely dependent on the soldier. Receiving support from other siblings disqualified the applicant; a certificate from a clergyman or the local Patriotic Fund committee was required to establish the facts. Anyone collecting a regular salary from federal or provincial governments and all members of the permanent force were denied separation allowance. ‘Applications for the allowance from parties who do not come under the above provisions cannot be considered.’33

Since the war did not end by Christmas, soldiers considered marriage. Could they then apply for separation allowance? Appalled at the spiralling costs and duration of the conflict, the government’s answer would have been a blunt no. SA had been devised for men who were married when they enlisted. But was it wise to do anything to discourage recruiting? Was it fair? Ministers were reminded that ‘the sudden call for volunteers’ had separated couples who might well have exchanged promises to marry. A new order-in-council allowed marriages for men who applied at the moment of enlistment and who were recommended by their new officer commanding, ‘but if not married within twenty days hereafter, the permission [would] be cancelled.’34

As the separation allowance system grew more refined, the Militia Department had to define a wife or, in some cases, more than one of them in ways that fitted nine provincial legal systems. In November 1915 officials granting separation allowance were provided with a definition in which the ingenuity of several lawyers was apparent: ‘For the purpose of the provision of Separation Allowance, “wife” means the woman who was married to the officer or the soldier in question under the laws of the country in which the marriage was solemnised and who has not been separated from her husband by a judicial decree or “separation from bed or board” or some similar decree parting her from her husband’s home and children, but where a wife so separated is entitled either by the agreement or by an order of a competent course to alimony, such wife shall be entitled to the extent of such payments or alimony, to the separation allowance.’35

Family support, public or private, was exclusively for women and children. Men could look after themselves. Or could they? Mr and Mrs John Grant of Sault Ste-Marie had two sons at the front. He had been paralysed since 1902; his wife, a nurse, cared for him and supported her family by taking in boarders. On 22 May 1915 she suddenly died, leaving her husband penniless and alone. Surely, claimed the local M.P., this was a case for separation allowance. So it might be, agreed J.W. Borden, but it was August before the Treasury Board soundly concluded: ‘that instead of dealing with the individual case it would be preferable to have submitted for consideration a general recommendation dealing with cases of this character.’ By then, the problem was theoretical: ‘As both Mr. & Mrs. Grant have died of want since this case was submitted to Treasury Board,’ J.W. Borden minuted: ‘there is no need for an O/C now.’36

The Grant tragedy should have been the kind of problem the CPF could solve, and officials like Herbert Ames stressed its flexible generosity. In practice, since the fund gathered contributions raised by its branches and then reimbursed branches for approved expenditures, the CPF’s rules were as firm as any government bureaucracy. Its donor base ranged from workers giving a day’s pay each month to the multi-millionaires who regularly took Montreal and Toronto campaigns ‘over the top,’ but Ames cheerfully invoked them all to influence government policy in ways he and his colleagues approved.

Assigned pay was an early example. By ‘assigning’ pay to a beneficiary, a soldier supported his family directly. The British required a pay assignment as a precondition for separation allowance. An intermittent libertarian, Colonel Hughes was not inclined to interfere with a soldier’s freedom to spend his pay. Neither was the Department of Justice. Its advisers found no legal authority to interfere with a man’s right to dispose of his earnings; a man was surely the best judge of his family’s circumstances.37 Those responsible for the Patriotic Fund saw the issue differently. Soldiers who spent all their pay and left their families to depend entirely on separation allowance and the CPF burdened the fund more than those who accepted their ‘manly’ responsibility. Not only was such an arrangement inequitable between married soldiers, the fund’s own donors would rebel at the cost of keeping a feckless soldier’s family in decent circumstances.38 From England, Colonel Ward added his support: ‘a large number of men,’ he claimed, ‘have never … made any effort at all to provide for their families … The main trouble is due to the excessive amount of money the men are receiving. I may say that Lord Kitchener is quite annoyed to think that our men are getting 4/6 a day and separation allowance for their families as against the fighting “Thomas Atkins” who is willing to serve his country in the new Army for 1/ a day.’39

After a brief campaign concerted by the newly knighted Sir Herbert Ames, the Patriotic Fund prevailed. On 23 January 1915 an order-in-council commanded that, barring special circumstances argued by the soldier, half the pay of non-commissioned ranks in receipt of separation allowance would be assigned to their dependant as of 1 April.40 For its part, the CPF agreed not to consider assigned pay in assessing the allowance levels for soldiers’ dependants. The fiction that the assignment was purely a soldier’s choice would be sustained, and his money would be available to pay down debts or develop a post-war nest egg. The CPF’s insistence that a private’s wife must now count on her assigned pay, however, hints that the principle was fictitious for the fund, too.

From the outset, the Patriotic Fund administrators worked closely with the Militia Department. Local branches had access to military nominal rolls as an aid in identifying eligible families.41 While the fund could pay an income supplement to any military dependants it judged to be in need of it, receipt of SA soon became a necessary qualification. The CEF’s records were needed to protect the fund against fraudulent claims from families whose breadwinner had been discharged, had deserted the CEF, or had never even joined up. At the same time, the CEF denied any influence on the fund. ‘This is a civilian association run by a civilian committee,’ Major General Logie, commanding in central Ontario, assured a desperate petitioner, and she must make her own approach, perhaps through the Toronto and York County Patriotic Fund Association.42

In Montreal, Miss Helen Reid, director of social work for St John’s Ambulance became convenor of the women’s auxiliary of the powerful local branch of the CPF. The fund, she insisted, had a ‘Third Responsibility.’ In addition to raising and spending money on soldiers’ families, it must provide advice and practical assistance.43 Part of that responsibility was her ‘black book’ of wives who had disgraced the cause. One was Margaret Curran, who left Montreal for Toronto owing rent and without informing the branch. Since Mrs Curran seemed ‘a very respectable looking woman,’ Martha Fennix, Reid’s Toronto counterpart, demanded more details. ‘Our further investigation,’ Reid reported, ‘shows that she left Montreal in the night, owing money to her Landlord, Grocer, Sewing Machine agent, and Gas Company, and in fact to nearly everyone she had had anything to do with.’ Even Curran’s German mother, who had showed up in Montreal, was astonished by her flit. ‘Mrs. Curran cannot be believed,’ Reid concluded, ‘and should be kept under the most strict supervision, not only on account of her German origin, but on account of her character.’44

Handling local enquiries and investigations for the SA administrators was a logical extension of a local committee’s oversight of its charges. Support from the fund depended on home visits, initially by male members of the branch donations committee, then increasingly by their wives and daughters. Employing what was unmistakably a means test, they were on the watch for extravagance – a telephone, a piano purchased by instalment, perhaps only a new hat.45 Fund representatives also investigated reports of adultery, drunkenness, and child abuse and neglect, and their advice was sufficient to suspend or cancel separation allowance, though it was left to the soldier, after receiving the reports, to decide whether to alter his pay assignment.46

The CPF was not organized everywhere, nor was it the sole source of advice. The province of Manitoba and some smaller cities insisted on a completely autonomous organization. Outside Montreal, Quebec City, and the Eastern Townships, little organization could be found in Quebec, and business was done informally, sometimes by the deputy minister, Sir Eugène Fiset. The mayor of St-Moïse and Father J.V. Beaulieu combined to persuade Fiset to compel Private Belliveau to support his widowed mother. When the widow Précille Chartrand complained that she had never seen the $45 per month her son had been promised on her behalf when he joined the 22nd Battalion, Fiset personally sent her a claims card for her curé to sign. Lt-Col. Émile Rioux asked ‘mon cher Fiset’ to send him the cheque he had negotiated for Mme Amédée Gagnon; for otherwise he would never be paid. She lived in the country and could come in and collect. Fiset obliged.47 When the Hon. A.E. Kemp, MP for Toronto-East, replaced Hughes as minister in November 1916, he accepted the back-channel influence of A.H. Birmingham, Liberal-Conservative organizer for Ontario. True, Mrs Ellen Johnston had received SA from two of her soldier-sons when a son still at home could support her, but she had sent three boys to the front, Birmingham argued, and she was a faithful member of the Loyal Orange Lodge, as were all her sons. Similar consideration was owed to the widow of a former employee of Kemp’s old firm, the Sheet Metal Company.

By the spring of 1915 the pay system seemed to be working for both CEF contingents. By the end of March 1915, Duguid reports, members of the CEF had earned $6,896,290.40 and paid $1,255,372.70 in assignments to families and relatives. Despite the dominance of the British born, $916,154.31, or three-quarters of the money, went back to Canada.48 New battalions organizing in Canada had the benefit of experience.

Most cases were straightforward enough. Frank Amato joined the 180th Overseas Battalion in October 1916, shortly before it went overseas, leaving his wife, Mary, and five children, age eight years to eighteen months, at 68 Mansfield Avenue in Toronto. His mother Angeline, a widow, had other sons to support her. His colonel signed the application and both AP and SA were established by mid-November.49 Edith Pearl Carey of Kingston should have had no complaints, since her husband, a former CPR trainman, continued to receive his railway pay after enlistment and she received separation allowance. Yet she was annoyed that because of her CPR income, the CPF cut her off.50 Other women discovered that army discipline affected them, too. The army took six months to explain to a seventy-year-old British Columbia mother that her son’s assigned pay had stopped after a court martial sentenced him to fifteen months’ imprisonment with hard labour for being ‘drunk on the line of march.’ Bleak poverty added to her shame and disgrace.51 Blanche Cushman pleaded in vain for news of Private Fuisse, a Second Contingent soldier who had ‘left me his unmarried wife and baby, 3 months old, and both homeless and penniless … He has never tried to deny the baby which is a beautiful child and his image a baby girl.’52

Serious administrative problems continued for many soldiers’ families. In Canada, the CEF continued to expand under the newly promoted and knighted Major General Sir Sam Hughes. His freehand style allowed scores and soon hundreds of colonels to recruit battalions in cities, towns, counties, and districts, sometimes under the aegis of an existing militia regiment but increasingly whenever a veteran politician or business leader claimed the right to test his popularity. In a society as unmilitary as Canada, the approach had its merits, but the price was continued chaos.

Inexperienced colonels gave administration a low priority, reproducing some of the chaos of Valcartier. Recruits spent as much as a year in Canada, often billeted in their own homes and raising issues of why separation allowance should be paid to families that saw a lot of them. A typical battalion, according to a pay official, had 50,000 documents; all should have been checked and most were not. New regulations and last-minute scrambles for recruits meant that many units still left Canada with incomplete records. Men who deserted or who were left behind as sick were easily reported as having gone overseas and months followed before the records were corrected. Confusion was compounded when battalions were broken up to provide reinforcements for units in France.53

Lost, incomplete, and confused records victimized families in Canada. Every MP had examples of families left destitute because separation allowances and assigned pay never arrived, claimed E.M. MacDonald, a Liberal MP from Cape Breton: ‘How can you expect enthusiasm among the plain people of the country when you have cases like this right under their noses?’ As a government member, Herbert Ames downplayed the problem, but, as the leading official of the CPF, he insisted that the CPF was the chief alleviating force and blamed pay-masters and soldiers themselves for failing to fill out the necessary forms: ‘Where avoidable mistakes occur, as they do occur sometimes, and when it is brought to the attention of one of our branches that a woman is not getting her assigned pay or separation allowance, through some reason not explained, she need not suffer, because the Patriotic Fund will give her all the money she needs until the rectification is made.’54 ‘Don’t be a bit backward about going after the Patriotic & get all you can,’ Ernest Hamilton commanded from England to his wife, Sara.55 Another man with two children claimed to have done better from the Toronto & York. Yet how many women would care to argue with Helen Reid or one of her minions?

CEF growth added to the burden – and the importance – of the Patriotic Fund. According to Ames, 30,000 families had benefited from the Patriotic Fund by 1916, and the number had doubled by the summer of that year. Whatever the local evidence, Ames continued to insist that the Fund had a flexibility no government could match. In a favourite illustration, he explained to Parliament in 1916: ‘If a millionaire and his coachman enlist as privates in the same regiment, each gets $1.10 a day and the wife of each gets $20 a month. In the case of the millionaire’s wife, $20 a month is a mere incident to her; she has no need of it at all. In the case of the coachman’s wife, provided she has a family of four or five children, she cannot subsist on $20 a month. Consequently the Patriotic fund comes along and says “How much is needed for you and your children to live decently and comfortably?” The Patriotic Fund brings that $20 up to the sum necessary to enable that family to live as a soldier’s family should live.’56

He also insisted that the fund was the perfect answer to calls to increase separation allowances. By sparing taxpayers the enormous expense of raising everyone’s SA when, by CPF standards, only some families urgently needed more money, the fund delivered a substantial benefit to taxpayers while encouraging Canadians to demonstrate their generosity.57 Local branches also put pressure on the government to tighten up payments. The CPF soon discovered that militia records could not always be relied upon to keep track of significant numbers of deserters and deadbeats. The secretary of the Brantford branch of the CPF urged that Walter Jackson of the 198th Battalion be sent overseas or released. He had a large family and a sick wife, and ‘He has, to our knowledge, served in at least three different Battalions, and we understand has made the boast that he will never go Overseas to fight.’58 Fund officials urged that separation allowance not be paid until soldiers had definitively left Canada, and on 24 January 1916 the Militia Department agreed. Agnes Georgeson was one of the early victims. Her husband wanted to switch battalions and took poor advice, getting a discharge before he joined the other unit. Immediately, his family lost all support until the new unit left Canada, leaving Mrs Georgeson and her three children to live on air. Since unemployment had driven her husband to enlist, she had no savings. ‘I can’t rest I am just worried to death thinking about the whole business,’ she told her husband’s colonel. ‘For pity’s sake try and help us someway out of the difficulty.’59 It took three months and a host of letters, all acknowledging the urgent need, before Mrs Georgeson escaped her difficulty. Another change proposed in the summer of 1916 arose when CPF officials noted that an orphan’s pension was only $12.00 a month, while the same child could claim SA of $20.00, the same rate as a mother received. The change was contested, since it threatened to subject an officer’s child to the same rate as that of a private’s offspring.60

The CPF helped to aggravate a larger inequality. At the outbreak of war, thousands of militia had been deployed to protect the coasts, canals, and other sites deemed vulnerable to sabotage by Germans, Austrians, or even Fenians. By 1915 Home Defence service was obviously more boring than dangerous and perhaps was no longer necessary, but local voters and contractors helped to persuade the government to keep 9,000 soldiers guarding forts, canal locks, and internment camps. Their families felt the brunt of public disdain as well as financial hardship, but citing its donors’ opinions, the Patriotic Fund refused to help. By 1916, as inflation sent prices soaring, military pay was inadequate, whether the man earning it was at Ypres or Esquimalt, but home defence soldiers received lower rates of pay and subsistence allowance, and their families were excluded from any CPF bounty.61

Anne Failes, whose husband served on the Welland Canal Force, reported that she paid $10.00 for rent, $10.00 for groceries, $5.00 for gas and fuel, $3.50 for clothes and boots, $2.50 for meat and $2.00 each for milk, school books, and an allowance to her aged parents, leaving nothing for a doctor or medicine if any of her four children became sick. Neither her advocacy nor that of Major General Logie, nor a petition from Mrs A.W. Matsell and six other soldiers’ wives in Calgary made any difference.62 Private W.R. Duke, who guarded German internees at Kapuskasing, might as well have been in France so far as his family in New Liskeard was concerned. He earned $300.00 a year less than a CEF soldier, and his wife had to leave their three children and go to Haileybury to find work. ‘Now is it fair,’ she asked the prime minister, ‘that a Government should place parents in such a position that both had to be away from their home and family and no one to train the children for proper citizens of Canada?’63 A desperate Katie Dickinson, with five sick children and mounting medical debts, pleaded that her husband be sent overseas: he ‘could fill a needy corner at the “Front” if he only had the chance, & then his family could be placed out of reach of want.’ She got her wish.64

Initially the councils of the Patriotic Fund were divided by arguments over Home Defence families. Halifax, Vancouver, and other communities that supplied most of the troops favoured involvement; large inland cities that supplied the bulk of the funds did not. The big cities prevailed, since, as Ames explained to the minister, ‘contributions would dry up immediately’ if anything was diverted to families of home-defence troops.65 Resentment at ‘shirkers’ dodging German bullets found an echo in CPF advice and the government’s response. On the eve of the 1917 election, A.G. McCurdy, the Union candidate in Halifax and Kemp’s parliamentary secretary, reported a touching meeting with a woman and her four children who had been turned into the street. The rate had to go up, ‘otherwise very many of the wives and families of the home defence men will be subject to poor relief and I hate that and you know how the men will hate it.’ A week later, the government finally set pay and allowances for home defence troops at the CEF level.66 The Patriotic Fund did not revise its policy.

As the war dragged on, complications in the administration of separation allowances grew. In October 1916 in a report to cabinet it was acknowledged that ‘quite a large number of soldiers having two wives have come to light.’ Most were wives married in England and abandoned when the soldier emigrated to Canada and attracted another mate. Some Canadians took on an extra wife while in Britain. On New Year’s Day 1916 Mrs Alex S. Seeley of Manchester demanded that the Militia Department track down her husband, who, she learned, had another wife in Canada. Indeed, she may have suspected it: ‘when he married me i asked him if he weren’t a married man and he told me that he was not a married man but if he was a married man he would soon do away with her an come back to me in england.’ Now she wanted the Militia Department ‘to hunt him up and make him support his child.’67 An ‘Old Original’ from the 8th Battalion, Corporal Seeley now claimed Mrs V. Seeley of Renfrew, Ontario, as his wife. He himself had been discharged as ‘medically unfit (hysteria)’ in April 1916.68

Unlike the Canadians, the British Army had accepted common-law marriages, and some of the common-sense advantages were apparent when the bigamy issue emerged. While a British soldier could support the wife who supported him when he enlisted, Canadian law required that only the first wife be supported. In most cases, that left the Canadian wife and offspring destitute, since cancellation of her separation allowance also cancelled her ‘Patriotic.’ Faced with these facts, the cabinet obligingly adopted British practice: PC 2615 redefined a soldier’s wife as ‘the woman who has been dependent on him for her maintenance, and who has been supported regularly by him, on a bona fide permanent domestic bases for at least two years prior to his enlistment.’69 The reaction was mixed. Helen Reid and other leading women in the Patriotic Fund administration exploded with indignation: the order ‘countenances bigamy, non-support and desertion, and thereby imperils the greatest asset of the state and society – viz the family and the home.’ It would turn Canada into a ‘happy hunting ground’ and worse than a Turkish harem where ‘all wives and children were provided for.’ Armed with the British precedent and careful wording to meet the requirement of Quebec law, the cabinet was unmoved.70

Once enlisted, of course, regulations had made it clear since 1915 that soldiers had no business getting married. Political jealousy helped to make trouble for Sergeant W.H. Sharpe, a former Toronto civic employee, when he married Alma Freed in 1916, more than a year after he had described her as his wife in his enlistment papers. Since she had already borne him a son, PC 2615 helped to guide the official reaction: he had only regularized the status of his ‘unmarried wife.’71 That argument would not help Doris Green, who had married Private W.H. Simpson, an orderly at the Ontario Military Hospital at Orpington in Surrey, and who by 1917 was pregnant. Since there was no question of a pre-war engagement, there was no case for SA. Her indignant brother took advantage of Sir Robert Borden’s well-publicized presence in Britain and wrote directly to Canada’s prime minister to denounce the injustice: ‘The practical outcome seems to be that Canada is to secure marriages and healthy human propagation “on the cheap” as our vernacular has it.’ After three years of war, did Canada assume ‘that these young soldiers will remain chaste and sterile during the lustiest years of their manhood?’ Canada’s official response was that soldiers had repeatedly been reminded of the rules and that whatever inducements the men themselves might have offered had utterly no backing from the Canadian authorities.72

With thousands of Canadian men spending months and even years in England, marriage was a serious issue. Major General Sir John Wallace Carson, the Montreal mining magnate whom Sir Sam Hughes had appointed as his agent in Britain, deplored saddling Canada with expensive, $20.00-a-month allowances because soft-hearted colonels had yielded to any excuse for marriage. ‘There is no doubt at all but that we are being “soaked” with many men that are getting married.’ To cure the problem, Carson assigned one of his many surplus colonels, H.A.C. Machin, a future director of the Military Service Act, to put a stop to it.73

Sir Sam Hughes’s influence in England was undercut in September 1916 after Borden appointed his friend Sir George Perley, Canada’s high commissioner in London, to a new portfolio as minister of the overseas military forces of Canada (OMFC). It ended entirely when Sir Edward Kemp replaced him as minister of militia in November. Among the least of Perley’s inherited problems was a claim for separation allowance from one of the ministry’s chief clerks, W.O.1 G.B. Goodall, a stalwart character who had already earned the Meritorious Service Medal. After two years of engagement, Goodall had married his betrothed only to be denied privileges less respectable soldiers enjoyed. A gentle spirit with a powerful wife, Perley urged his colleague Sir Edward Kemp to reconsider the issue. Women like Mrs Goodall or Mrs Green would be entitled to a widow’s pension if their husband died, and ‘in practically every case these English wives will ultimately become residents of Canada and mothers of Canadian children.’74 In July Perley’s advice became an order-in-council: soldiers overseas could now marry with a commanding officer’s consent and a clergyman’s certificate of good character: ‘should there be any suspicion that she is not “a proper person to receive the allowance,” a pay officer would investigate.’75

During 1916 a major component of CEF enlistment was older soldiers recruited in special battalions for the Canadian Forestry Corps and the Canadian Railway Troops. Because they worked far from the front lines and usually qualified for working pay, railway and forestry troops found almost as little sympathy from the Patriotic Fund as Home Defence soldiers. The fund’s assistant secretary, Philip Morris, insisted that such troops must include working pay in calculating their AP. Their family income would thus include both the AP and the SA, and the fund would have to spend little or nothing on them. The donors, as usual, would insist on it! J.W. Borden, as paymaster general, hardly made a strong case for the railway and forestry troops by claiming that ‘dependents are sometimes inclined to spend money too freely, thus leaving the soldier himself without anything on his return home.’76

Until 1917 generosity to dependants, if often more theoretical than real, was crucial to voluntary recruiting. Women had been identified early as crucial influences on a man’s decision to enlist. Lavish claims for the generosity of the separation allowance and the flexible compassion of the Patriotic Fund helped men to join up with a clear conscience. Their families would be well cared for. Though the government was slow to notice, however, voluntary recruiting for CEF infantry had virtually dried up in the late summer of 1916. By the winter of 1917 the government came face to face with the dilemma of imposing conscription or reducing its fighting strength on the Western Front. To do so when Russia was collapsing and the French army had mutinied after the disastrous offensive on the Chemin des Dames was unthinkable for Sir Robert Borden. The Military Service Act, introduced in June 1917, meant that henceforth most CEF volunteers and virtually all conscripts would be single.

Packaging at the Women’s Canadian Club, Ottawa, September 1918 (W.J. Topley, National Archives of Canada, PA800010)

Conscription had another consequence. As the country divided, it grew steadily more difficult for the Patriotic Fund to contemplate serious fundraising. Though Montreal’s March 1917 campaign broke all records, it could not be repeated.77 By 1918, as Morris admitted in his history of the fund, parts of British Columbia were distinctly inhospitable.78 Earlier oversubscriptions and tight-fisted management meant that a crisis was postponed. Indeed, when the war ended on 11 November 1918, two years earlier than feared, the CPF emerged with an embarrassing surplus.

New ministers in Ottawa and London and a harsher edge to Canada’s war effort encouraged tighter control of military manpower and more efficient administration. By the end of 1916 the Separation Allowance and Assigned Pay Branch had grown into an impressive bureaucracy. In January 1916 the branch held 65,100 separation allowance accounts. Growth that year was spectacular: by year-end, the department claimed 231,518 SA and AP accounts. In a single month, when twenty battalions left for overseas, the branch had to add 32,267 accounts.79 Each AP and SA account required a ledger page and a monthly cheque to the correct address to recipients who were often semi-literate and who seldom grasped the importance of regimental numbers in military filing systems. Defective systems allowed cheques to keep flowing to families of men who had deserted, perhaps to re-enlist under an assumed name. Others may have been honourably discharged, but a crucial document had been lost.

In March 1917 Major Ingalls, who had developed the Canadian Pay and Records offices in London, returned to Ottawa to oversee the SA and AP Branch, an operation that had grown in a year from 1,000 to 13,500 square feet of space and from 189 to 2,055 ledgers.80 Ingalls inherited a staff of 494 men and 131 women, working at lower salaries than their counterparts in the nearby Imperial Munitions Board. Among his tasks was recruiting women and urging able-bodied male employees to enlist. Permitted to move his branch to a larger building, he installed time clocks and acquired forty-six cheque-writing machines, six scriptographs to sign them, and two mimeographs to produce forms. In the summer of 1917 he hired ninety-two women to consolidate AP and SA accounts in a single ledger. They needed forty-six days. By the end of the summer, the machinery allowed him to send out 250,000 cheques as fast as the post office could handle them.81

Ingalls also found himself blamed for everyone else’s negligence, insouciance, and greed, from lazy paymasters to dishonest clients. Soldiers told families of promotions before they were promulgated. Deserted wives claimed separation allowance from Ingalls’s branch and husbands disowned them there. It was Ingalls who heard from widows, abandoned after a ‘sole support’ son insisted on switching his assigned pay to a newly married wife. His office was the target for any of the 10,000 SA or AP beneficiaries in the Ottawa area who dropped in on his branch to demand service. He reported ‘the persistent manner in which women write for cheques before they are due.’ Until he moved his operation, Ingalls even lacked a private room to meet his visitors.82 Fed up with investigative delays and inconsistencies, the Militia Department backed the SA Branch with its own Appeals Board and a staff of ‘lady investigators.’ In February 1917 the cabinet approved the Board of Review, consisting of two experienced lawyers and the CPF’s assistant secretary, Philip Morris. The chairman was a Nova Scotia lawyer and veteran, Major J.W. Margeson. Within a year, the new board had reviewed 40,000 files and ruled on 28,000 of them.83 Investigators, usually from the local CPF branch, tracked down overpayments to families of deserters, checked out ‘sole support’ claims from widows, and sent a Mrs Diprose to Carleton county jail for six months for pretending to be a Mrs Jones for the sake of her SA.84 Another investigator, May Morris, played a more positive role in investigating a Toronto widow’s claim that one of her soldier-sons was her ‘sole support.’ The father of H.W. and H.T. Smith was a messenger for the Bank of Commerce when he died in 1914, leaving nothing for his widow and four children. The bank provided a three-year annuity, the widow’s two sons enlisted, and each assigned $20.00 to support their mother and her mother. The elder son’s request for SA was refused, partly because the Smiths’ clergyman did not know that the bank annuity had expired, and partly because the Toronto CPF believed that a fifteen-year-old son should have gone to work to support his mother. May Morris got justice done.85

Tightening up was predictably unpopular. T.S. Ewart, a Winnipeg lawyer, complained that Margeson’s board had cut off a widow who had lost a son at Ypres because her other son had survived as a prisoner of war. Surely she could write to him, a Militia Department official insisted, and demand a larger assignment.86 Another Winnipeg law firm considered a message from Ingalls to their client to be ‘so grossly impudent and impertinent that it is difficult to reply to it at all.’ The client, Mrs Carey, had two sons at the front and her late husband, assumed to be well off, in fact had died penniless. The eldest son, who was expected by the AP Branch to support her, was well known to be an invalid. Ingalls was unrepentant. Mrs Carey needed a certificate from the CPF or a clergyman, like everyone else. With so many improper applicants, ‘great care was needed.’87

Recovering overpayments to families after death or discharge could be sensitive. Often a death notice failed to reach Ottawa in time to stop the monthly cheques; in other cases, it took months to collect a man’s personal effects and to finalize his estate. Reclaiming a few hundred dollars from a widow or a bereaved mother was not easy. Other ranks soon gained an officer’s privilege of a full month’s pay after death. An order-in-council in February allowed widows to receive their SA and AP as a gratuity until their pension was formally granted.88 While Ingalls agreed to be judicious about the dead, he was convinced that when families improperly collected SA during a soldier’s three months of post-discharge pay, they did it ‘with a full knowledge that they were taking money that was not due to them.’89

Overpayments helped to justify the first increase in separation allowance since the war began. When surplus battalions were broken up overseas, scores of sergeants lost their stripes and their families lost $5.00 of their separation allowance. Promotions and reversions forced Ingalls’s branch to make up underpayments and recover overpayments, often just before the man regained his rank.90 His answer was to standardize all SA at $25.00, an act approved by the government for December 1917, just before soldiers’ wives and mothers exercised the special franchise granted them by the Wartime Elections Act. Continuing inflation justified a second increase, in September 1918, to $30.91

A little smugly, Ingalls reported his branch’s policy of stopping SA, usually on CPF advice, ‘for the reason that the wives of the soldiers have become immoral or something like that.’ Whatever most MPs felt, he provoked outrage from R.B. Bennett, a former Alberta Conservative leader and future prime minister: ‘By what right do you stop payment because someone tells you that she has become immoral?’ shouted Bennett. ‘I want to know that!’ Ingalls fumbled: he had only acted on instructions; he was new to the job; he had righted some injustices, but ‘in the larger part of the cases,’ he insisted, the grounds were sound. Bennett was not mollified. When a man assigned $20.00 a month to his wife, did that mean ‘that the Government of Canada becomes the censor of her morals?’ No, quibbled Ingalls, the assigned pay was never stopped, only the SA. Finally, the committee chairman intervened to rescue him in the name of conventional morality: ‘I would not say that the Government becomes the censor of [a wife’s] morals. When the soldier goes to the front, he leaves his wife and family, usually, in trust to the Government and the Patriotic Fund. Now if that woman becomes immoral and forgets the care of her children, and becomes a drunkard and those children are likely to starve or run wild, the country owes an obligation to the children as well as the wife.’92

Apart from the Patriotic Fund’s Helen Reid and her counterparts in other branches, family support issues were largely determined by men. Even Reid, sufficiently powerful to be added to the CPF’s national committee at the end of the war, always reported to the Montreal branch through Clarence Smith, a former executive of Ames’s family shoe business. If not entirely missing from the record, the beneficiaries of the family support programs are very largely silent. They certainly had grievances. Allowances that may have seemed generous to a working-class family in 1914, steadily lost value when inflation hit in 1916. By the war’s end, consumer costs had risen 46 per cent.93 Even early in the war, the gap between the Department of Labour’s cost of living figures and the amount the Patriotic Fund considered sufficient was far higher in the west than the east, and it grew with inflation (see table 8.2) fund officials argued that eastern donors heavily subsidized the western provinces, and allowances in the west were at least $10.00 higher than in the east, but soldiers’ wives in Calgary or Vancouver compared themselves with their neighbours, not with their counterparts in Toronto or Halifax.

Table 8.2

Cost of Living and Soldiers’ Family Benefits, 1915

|

||||

Province |

Family* |

Adjusted**1 |

CPF + SA*** |

Difference |

|

||||

PEI |

$47.06 |

$35.81 |

$31.20 |

–$4.61 |

NS |

50.94 |

38.44 |

35.00 |

–3.44 |

NB |

51.86 |

38.51 |

35.32 |

–3.19 |

QC |

51.20 |

37.00 |

36.30 |

–0.70 |

ON |

46.97 |

37.92 |

37.22 |

–0.70 |

MB |

58.15 |

48.15 |

43.60 |

–4.55 |

SK |

63.04 |

51.34 |

42.73 |

–8.66 |

AB South |

61.76 |

45.26 |

37.30 |

–7.96 |

AB North |

61.76 |

43.61 |

45.51 |

+1.90 |

BC |

63.00 |

53.45 |

39.79 |

–13.66 |

|

||||

* Cost of living figures for food, fuel, and rent for a family of five.

** Adjusted for missing father.

*** SA of $20.00 plus CPF assistance for a family of five.

Source: NAC, Duguid Papers, vol. 1.

‘The Patriotic Fund,’ as E.W. Nesbitt, M.P., explained, ‘is … looked upon to a great extent as a charity, there is no getting over it,’ and its stigma was everywhere, from means tests by middle-class wives and daughters with their own grievance over the wartime dearth of maids and charwomen, to newspaper complaints about alleged extravagance by soldiers’ wives.94 Soldiers might urge their wives to demand their rights from ‘The Patriotic,’ but little in the socialization of Canadian working-class women gave them the courage or the knowledge to do so.95 Even separation allowance depended on applications by a husband or son, mediated by a highly fallible bureaucracy that stretched from behind the lines in France through Ottawa to an overstretched postal system.

SA recipients could organize in support of a higher rate, but it was not easy. The Soldiers’ Wives Leagues formed during the South African War were now dominated by the wives of senior militia officers with patriotism, not feminism or maternity, on their minds.96 As part of her ‘Third Responsibility,’ Helen Reid encouraged groups of wives to meet for lectures on infant care and to practise motherly crafts, but the auspices were not encouraging for grievances.97 During the war, the National Council of Women recorded several ‘Next-of-Kin’ Associations for soldiers’ wives, but most proved quarrelsome and short lived.

Alberta was a leading example. In Calgary, Jean McWilliam, a prewar Scottish immigrant and wife of a British reservist, worked as a cleaning woman and police matron to support herself and her two children. She saved enough to buy a boarding house and found the energy to organize a Next-of-Kin Association with help from local socialists. Arguments for higher allowances were mixed with demands for limits on profits, higher taxes for the rich, and equal pensions regardless of rank. She also wanted free vocational education for soldiers’ children and internment of unemployed enemy aliens. The Calgary group soon confronted a similar association from Edmonton, organized by officers’ wives. When the two organizations struggled for the right to be incorporated by the province, the Edmonton women gained support from Roberta McAdams, a nursing sister with strong Tory credentials, elected by Alberta soldiers overseas. Alberta’s Non-Partisan upheld the Calgary women as ‘a working-class organization with the proletarian outlook’ and denounced the Edmontonians as ‘ultra-patriots,’ but the Edmonton group prospered.98 It reported 300 members at monthly meetings in 1918–19 and a provincial grant that allowed them to run a home for forty children. Its activities, concludes Linda Kealey, ‘were probably more typical of Next-of-Kin Associations.’99

Even the wives of ordinary soldiers could not always count on the left. Winnipeg’s Women’s Labour League was sympathetic but robustly denied official support for higher allowances, since its responsibility was to ‘working girls and women’ and because contradictory statements suggested that the wives did not ‘know their own minds.’100 On the other hand, Mrs J.C. Kemp seems to have organized her Vancouver’s Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Wives Association by walking the political tight-rope, including Sir Charles Hibbert Tupper and Charles Macdonald in her organizing meeting and including jobs as fruit pickers in her program as well as higher allowances, pensions equalization, and demanding immediate conscription to ‘help our boys end this war.’ In the fall, Mrs Kemp was reported as surviving a split, because her critic, Mrs Fink ‘did not offer the suggestion politely.’101

By the war’s end, Canada’s was a seriously stressed country, profoundly divided by class, region, and the raw wound of imposing conscription on Quebec. Most of the lines of fracture were reflected in the families of soldiers and those who had undertaken to care for their needs. Exhausted by his wartime services to the Patriotic Fund, Ames left to join the staff of the new League of Nations, leaving his role in the fund to W.F. Nickle, outspoken Conservative MP for Kingston. Ideally, in the eyes of its managers, the fund would have ended with the war, but its staff and its surplus compelled it to continue social service to families whose soldiers had abandoned them and as reluctant administrators of Ottawa’s post-war emergency relief for unemployed veterans.

Table 8.3

International Rates of Separation Allowance and CPF, 1918

|

||||

Family State |

Canada* |

Great Britain |

Australia |

United States |

|

||||

Wife |

$30.00 |

$9.00 |

$10.00 |

$15.00 |

Wife and 1 child |

40.00 |

16.00 |

13.00 |

25.00 |

Wife and 2 child |

43.00 |

21.00 |

16.00 |

32.50 |

Wife and 3 child |

47.00 |

24.00 |

19.00 |

37.50 |

1 child |

25.00 |

7.00 |

– |

5.00 |

4 children |

30.00 |

25.00 |

– |

30.00 |

Widowed mother |

35.00 |

9.00 |

10.00 |

10.00 |

|

||||

* Canadian separation allowance: $25.00.

Source: Special Committee on Pensions, 1918, 185.

For a debt-ridden government, the cost of separation allowance became an added reason for the Militia Department to speed the return and demobilization of married soldiers. Some 38,000 women and children returned as ‘dependants,’ almost all from Great Britain. Soldiers with wives and families in England joined them at Buxton and travelled on ‘family ships’ to Saint John.102 Since 4 August 1914 about 20,000 Canadian women had become war widows.103 Since 1916 their financial fate had rested with a three-member Board of Pension Commissioners, chosen for its immunity to pressure and dedication to strict regulations. The board wrestled with many of the complexities the separation allowance administrators had faced and came to similar conclusions.104 Like the war itself, Canadian demobilization was completed earlier than most experts and administrators had predicted.105 By August 1919, 97 per cent of the CEF had returned from overseas.

Neither the war nor its conclusion left happy memories. Thousands of working-class women had come in painful contact with both charity and bureaucracy, and neither experience had been pleasant. If men believed that their families would be fairly treated in their absence overseas, they often returned to find them living in the shabbiest house on the street. Even with helpful neighbours, few women could maintain a farm, and those who tried business sometimes fell foul of the CPF or licensing authorities. Some women, as the CPF boasted, used natural frugality, good luck, a steady income, and the fund’s oversight to pay off debts, establish savings, and lay a foundation for a prosperous post-war farm or small business. Others had little to show for years of loneliness, anxiety, and struggle but a semi-stranger with bad habits and painful memories, trying to resume his place at the head of the family. Others discovered premature widowhood and continued dependence on suspicious bureaucrats from the Pension Board.

More valuable, if only potentially, was an accumulation of experience and knowledge about a lot of Canadian families. Enough had been learned about the Patriotic Fund that, when war returned in 1939, its revival seems barely to have been considered. Instead, families subsisted on a more generous version of the separation allowance and appealed, in their crises, to an Ottawa-based board or its local agents, usually from the Canadian Red Cross.106

Family life, as usual, continued as well as it could.

This article evolved as part of my preparation for a book, entitled Fight or Pay, on the families of Canadian soldiers in the First World War. It reflects contributions from many colleagues and students, including Barbara Wilson, Cheryl Smith, Adrian Lomaga, Tanya Gogan, Ulric Shannon, Jenny Clayton, and Gibran van Ert. However, it also reflects the leadership and example of Craig Brown, my colleague and friend over many years and my inspiration in addressing innumerable questions about Canada and its Great War.

1 National Archives of Canada (NAC), MG 30, A.F. Duguid Papers, statistical records for the Official History of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. Using needle-sorting equipment, Duguid’s staff identified 9,093 officers, 47 nursing sisters, and 116,930 other ranks as married members among the 619,586 who served in the CEF in 1914–19.

2 See Philip H. Morris, ed., The Canadian Patriotic Fund: A Record of Its Activities from 1914 to 1919 (Ottawa: n.p. [1920]); also W.F. Nichols, Canadian Patriotic Fund: A Record of Its Activities from 1919 to 1924, 2nd Report (n.p., n.d.). Articles include Margaret McCallum, ‘Assistance to Veterans and Their Dependents: Steps on the Way to the Administrative State,’ in W. Wesley Pue and Barry Wright, eds, Canadian Perspectives on Law and Society: Issues in Legal History (Ottawa: Carleton University Press, 1988), 157 et seq.; Desmond Morton and Cheryl Smith, ‘“Fuel for the Home Fires”: The Patriotic Fund, 1914–1918,’ Beaver 74, 4 (1995), 12–19; Charles Humphries, ‘Keeping the Home Fires Burning: British Columbia Women and the First World War,’ unpublished paper presented to the Canadian Historical Association conference, Charlottetown, 31 May 1992; and David Laurier Bernard, ‘Philanthropy vs the Welfare State: Great Britain’s and Canada’s Response to Military Dependants in the Great War,’ Master’s thesis, University of Guelph, 4 September 1992.

3 See Desmond Morton, ‘Entente Cordiale? La section montréalaise du Fonds patriotique canadien, 1914–1923 : le bénévolat de guerre à Montréal,’ Revue d’histoire de l’Amérique française 53, 2 (1999), 208–11.

4 Statistics have been compiled from charts prepared for A.F. Duguid’s unpublished second volume of his Official History of the Canadian Forces in the Great War: General Series (Ottawa: King’s Printer). See NAC, Duguid Papers, vol. 1.

5 The King’s Regulations and Orders for the Canadian Militia, 1910 (with amendments), 139, s. 832. Officers met a more demanding standard, having to demonstrate that their ‘means are such as will enable him to maintain himself and family in a manner befitting his position as an officer’; s. 830 (2). The Canadian regulations were a close-to-literal copy of the British regulations.

6 Married quarters were provided with a ration of coal or wood and marked a Victorian-era advance from an era when a soldier’s wife set up housekeeping behind a blanket at the end of her husband’s barrack room. See W.D. Otter, The Guide: A Manual for the Canadian Militia (Infantry) … (Toronto: Copp Clark, 1913).

7 Ibid., 140–1; ss. 832–3, 844; Handbook of the Land Forces of British Dominions,. Colonies and Protectorates (Other than India), Part I, The Dominion of Canada (London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1911), 118–22, 126–31. The Canadian regulations virtually echoed the British model, with changes to reflect the local currency.

8 Canada, Militia List, August 1914, 119.

9 CEF rates of pay were higher than for the peacetime militia or the permanent corps: a dollar a day for a private, plus ten cents a day of ‘field allowance’; a sergeant collected a total of $1.50 a day and a lieutenant, $2.60. Officers collected $150.00 in ‘outfit allowance’ to buy uniforms and camp equipment. ‘Working Pay’ for farriers, cooks, butchers, bakers, wheelers, and other scarce trades ranged from $0.50 to $1.00 a day. On separation allowance and assignments, see Duguid, Official History, 57; see PC 2254, 3 September 1914 in appendix, 91, 61–2.

10 James L. Hughes, inspector of schools for Toronto and Colonel Hughes’s elder brother, had espoused votes for women, equal pay for women teachers, compulsory cadet training for both sexes, and the principles of the Loyal Orange Lodge since the early 1880s.

11 Duguid, Official History, appendix 94, 62. This was the second largest category, after the 5 officers and 2,159 other ranks sent home for medical reasons and ahead of the 13 officers and 269 other ranks who asked to be released. Colonel W.R. Ward, the CEF’s chief paymaster, suggested that the large number of subsequent claims for separation allowance grew out of concealment of marriage. NAC, Ward to J.W. Borden, Accountant and Paymaster General, 4 November 1914, RG 24, vol. 1271, HQ 593-2-35.

12 NAC, Mrs Wharton to Militia Department, 5 December 1914, RG 24, vol. 1271, HQ 893-2-35.

13 NAC, Henry T. Denison to Col. A. LeRoy, 12 September 1914; note on memo from OC, 6th Field Company, CE, RG 24, vol. 4656, f. 99–88 vol. 1; Humphries, ‘Home Fires,’ 7.

14 NAC, Charles E. Roland, Manitoba Patriotic Fund to Militia Department, 26 February 1915; Mrs Harry Mortimer to Officer of Pay, 31 May 1915, RG 24, vol. 1234, HQ 593-1-12.

15 See ‘A Bill to Incorporate the Canadian Patriotic Fund’ Bill No. 7, Special Session, 21 August 1914. Ames was the author of The City below the Hill (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1972 [reprint]), and the CPF presented an opportunity to test many of his ideas about reforming the poor.

16 For the importance of the precedent for Canada see NAC, Canadian Patriotic Fund circular 4, C.A. McGrath Papers, vol. 2, 4.

17 NAC, Report of 27 August 1914; PC 2266, 4 September 1914.

18 Canadian Patriotic Fund Circular No. 2, MG 28 I, 5, vol. 1. On British and Allied reservists, see Duguid, Official History, 1: 61–2. British SA was based on the number of children. A French reservist received 35 cents per day from France and from the French consul; outside the CPF, Belgian families depended on local charity (see ibid.). The CPF maintained families of British and French reservists on the same basis as CEF families. When Italy joined the Allies, families of Italian reservists received support at a much lower level. See Morris, Canadian Patriotic Fund, 7, 29–32, 339.

19 Desmond Morton, ‘A Canadian Soldier in the First World War: Sergeant François-Xavier Maheux,’ Canadian Military History 1, 1–2 (1992), 80; Morton and Smith, ‘“Fuel for the Home Fires,”’ 15. (As the correspondence reveals, Maheux was not forthcoming with assigned pay until he left Canada in June 1915, and his wife was obliged to use his assignment to pay off his old debts.)

20 See Morton, ‘Entente Cordiale?’ 218–19.

21 Duguid, Official History, appendix 230, 163.

22 NAC, Ward to Borden, 4 November 1914, RG 24, vol. 1271, HQ 593-2-35.

23 NAC, Ward to J.M. Borden, Accountant and Paymaster-General, 4 November 1914, RG 24, vol. 1271, HQ 593-2-35. See also Duguid, Official History, Appendix 230, 163.

24 Ingalls testimony in ‘Proceedings of the Special Committee on Returned Men, 1917,’ in Canada, Sessional Papers (Ottawa, 1917) (hereafter ‘Returned Men, 1917’), 1125.

25 Duguid, Official History, appendix 124, 164.

26 NAC, Haileyburian, 30 March 1915, cited in RG 24, vol. 1235, HG 593-1-13.

27 NAC, Memorandum re John C. Douglas, RG 24, vol. 1235, HG 593-1-12.

28 Morton and Smith, ‘Fuel for the Home Fires,’ 13.

29 NAC, Memorandum, n.d., RG 24, vol. 1343, HQ 593-3-22.

30 Among the complaints was one from the adjutant of the 24th Battalion on behalf of Mrs J.A. Gunn, the wife of his commanding officer. See NAC, Capt. Gerald Furlong to A&PMG, 26 December 1914, RG 24, vol. 1343, HQ 593-3-22.

31 NAC, Borden to Ward, 4 January 1915, RG 24, vol. 1271, HG 593-1-35, vol. 3. See also the Stalker case: Fiset to the British Consul-General at San Francisco, 26 March 1918, vol. 1234, HG 593-1-12.

32 NAC, Report of 7 October 1914 to PC 2553, 10 October 1914.

33 NAC, PC 2266, 4 September 1914, set out the initial terms and rates for separation allowance in a single page. For comparison after three years, see Militia and Defence Regulations Governing Separation Allowance, 1 September 1917, under PC 2375. RG 24, vol. 1252, HG 593-1-82.

34 NAC, PC 193, 28 January 1915.

35 NAC, PC, 2605, 26 November 1915, amending PC 2266, 27 August 1915; cited in Morton and Smith, ‘Fuel for the Home Fires,’ 15.

36 NAC, J.W. Borden minute to: Treasury Board to General Fiset, 10 August 1915, RG 24, vol. 1234, HG 593-1-12. The order was passed, and in January 1916 James Stevens, paralysed from the waist down, expressed his gratitude for $120 in SA; NAC, Kemp Papers, Stevens to Edward Kemp, 12 January 1916, vol. 34, f. 1198.

37 NAC, E.L. Newcombe to Eugene Fiset, 5 December 1914 and Fiset to Newcombe, 8 December 1914, citing Article 986 of the Royal Warrant, ss. 144, 145, The Militia Act, RG 24, vol. 1271, HG 593-1-35.

38 NAC, see Ames to Hughes, 18 November 1914, RG 24, vol. 1271, HQ 593-2-35; Hughes to Ames, 4 December 1914; Canadian Patriotic Fund circular no. 2, [October, 1915] MG 28, I, 5, vol. 1.

39 NAC, Ward-Fiset, January 1915, RG 24, vol. 1271, HQ, 593-2-35.

40 Report of 18 January 1915, reflecting British and Patriotic Fund pressure, and PC 1148, 23 January 1915.

41 NAC, John D. Adams, Toronto and York Patriotic Fund Association to OC, Military Police, Exhibition Park, 21 November 1914; S.P. Shantz to Major-General F.L. Lessard, 25 November 1914, RG 24, vol. 4285, 34-1-10, vol. 2.

42 NAC, Major-General Logie to Mrs S.H. Raun, 30 August 1916, RG 35, vol. 4286, 34-1-10, vol. 2.