DONALD AVERY

The conventional wisdom holds that the years 1914–19 were a time of serious social and political disruption for Canada. But why was this the case? Was it because of the unique and devastating consequences of the Great War when Canada, a relatively small nation of 6 million people, suffered staggering battlefield losses on the Western Front? Or did the searing experience with total war only intensify already existing tensions and problems that divided Canadians on the basis of ethnicity, religion, class and region?1

In this chapter I attempt to address these questions in relation to one region – the Canadian west – and to focus on one social group: European immigrant workers whose status as ‘foreigners,’ or ‘aliens’ became more sharply defined within the context of total war. During the years 1914–19 individuals and groups were deemed loyal or disloyal, law-abiding or revolutionary, according to how their behaviour conformed to the values and norms of the middle-class Anglo-Canadian community. Being an enemy alien – from Germany, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Bulgaria, or Turkey – was the most serious disability, at least until the latter stages of the war when fear of a ‘Bolshevik’ revolution in Canada gained momentum, particularly in those parts of western Canada where industrial conflict escalated.

The most spectacular confrontation occurred during the Winnipeg General Strike of May-June 1919, an event that polarized the city, the region, and the nation. In its desperate attempts to maintain social order the Union Government of Sir Robert Borden passed a series of draconian laws aimed at the radical alien. At the same time, members of the House of Commons seriously debated whether the country should continue to encourage European immigration, or whether the necessary numbers of industrial workers and agriculturalists could be secured from Great Britain and the United States. This cultural bias was reinforced by the growing popularity of eugenics arguments which stressed the supremacy of the Anglo-Saxon and Nordic ‘races’ – and the corresponding hereditary inferiority of eastern and southern Europeans. This debate paralleled developments in the United States, where Congress passed a series of quota laws, virtually excluding those immigrant groups deemed inferior on the basis of race and ethnicity.

What was most striking about the 1919 situation was the popularity immigration restriction enjoyed in the Canadian west, a rather surprising response given the region’s pre-war dependence on foreign workers in both the agricultural and the industrial sectors of the economy. Many western spokesmen, however, regarded this exclusionist movement as a temporary phenomenon, directly related to wartime tensions. This viewpoint was aptly summarized in May 1919 by Thomas Crerar, a prominent prairie politician: ‘A great majority of the people, as a result of the times we have lived through the last four years … are not quite back to normal judgement.’2

Between 1896 and 1914 Canada in general and western Canada in particular experienced unprecedented economic growth: railway mileage doubled, mining production tripled, and wheat and lumber production increased tenfold. This economic expansion was accompanied by dramatic population growth; in the decade 1901–11 the nation’s population increased by a remarkable 34 per cent. Much of this increase was due to immigration; in 1914 it was estimated that 3 million people had entered the country since 1896. Although a substantial number of these ‘newcomers’ settled on the land, the vast majority derived some portion of their annual income from the wage employment offered by the booming agricultural and industrial sectors of the western Canadian economy whose demand for labour, both skilled and unskilled, seemed insatiable.3

Led by the spokesmen for labour-intensive industries, including agriculture, public opinion in western Canada came to favour an immigration policy that went beyond the traditional open-door approach and encouraged the systematic recruitment abroad of men and women who could meet the challenge of a nation freshly embarked upon great enterprise. This opinion found expression in the immigration policies of successive dominion governments. Although the official pronouncements of the Immigration Branch in this period stressed that only farmers, farm labourers, and domestics would be recruited, exceptions were frequently made to accommodate the needs of businessmen in the expanding sectors of the economy of the three prairie provinces and British Columbia. That Canada’s search for immigrant agriculturalists was largely in the hands of steamship agents in search of bonuses further altered official policy; many who entered the country as farmers and farm labourers quickly found their way into construction camps, mines, and factories.4

Faced with the demands of major projects, such as the building of two new transcontinental railways, Canada’s ‘captains of industry’ required a workforce that was both inexpensive and at their beck and call.5 To them the agricultural ideal which lay at the root of Canadian immigration policy increasingly appeared obsolete. Supply and demand should be the new governing principle of immigration policy. The best immigrants would be those willing to roam the country to take up whatever work was available – railroad construction in the Canadian Shield in the summer, harvesting in Saskatchewan in the fall, coal mining in Alberta in the winter, and lumbering in British Columbia in the spring.6 This view ran against the deep-seated Canadian myth of the primacy of the land, but nevertheless it prevailed.7 By 1914 it was obvious, even to immigration officials, that Canada had joined the United States as part of a transatlantic market.8

Statistics on the ethnic composition of this immigration and the regional concentrations of immigrants (settlers and resource workers) as well as their distribution within the occupational structure bring to the surface the contours of what could be called ‘the specificity of the Canadian experience.’ In 1891, at an early stage in Canada’s industrialization, the foreign-born population accounted for 13.3 per cent of the total population, a figure that was roughly comparable to the ratio of immigrants in the United States. However, this foreign population came overwhelmingly (76 per cent) from British sources. By 1921 the percentage of foreign born had jumped to 22.2 per cent (which was about 7 per cent higher than that of the United States), while the foreign born other than British now accounted for 46 per cent of all the foreign-born population. After 1901 the spatial distribution of the foreign-born population was also modified as Ontario’s share declined from 46.3 per cent to 32.8 per cent. In contrast, the surge of immigrants into western Canada greatly changed the demographic character of these four provinces. In 1901 it was home to 31.5 per cent of all foreign born in the country; by 1921 the figure had risen to 54 per cent!9

Of the many immigration problems which faced the Laurier and Borden governments, none was more intractable and none politically more dangerous than that of the movement of Asians into British Columbia. Part of the problem, from Ottawa’s perspective at least, was the concentration of the country’s Asian population along the Pacific coast;10 another was the fact that, as cheap expendable workers, they became a pawn in one of the rawest struggles between capital and labour in a region where the wishes of big business were rarely denied.11 Yet by 1914 the large-scale entry of Chinese, Japanese, and Sikh immigrants for the most part had been curtailed because of the 1905 Chinese Immigration Act, which levied an exorbitant head tax of $500.00, and because of the regulations that were established after the 1907 Vancouver race riots.12

In many ways, the campaign for a ‘White’ British Columbia was similar to developments in the Pacific regions of the United States, where nativist organizations sought to exclude and marginalize Asian immigrants in their midst. Nor is this move surprising. Prior to the outbreak of war, Asian and White immigrants alike moved back and forth across the Canada–United States border in large numbers in search of work. There were also strong ties between labour unions and socialist organizations in the two countries, and radical organizations such as the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) enjoyed considerable success in British Columbia and Alberta in a series of spectacular strikes in 1907 and 1912. As a result, American and Canadian security agencies were already sharing information about anarchist and socialist radicals even before the Great War.13

The economic status of immigrant workers on the eve of the First World War was not favourable. By 1912 the unsettled state of European affairs had helped to produce a prolonged economic slump in the transatlantic economy. This recession was particularly felt in western Canada, a region which was very dependent on foreign capital for its continued prosperity. By the summer of 1914 there was widespread unemployment in the area, the more so since over 400,000 immigrants had arrived in the previous year.14 Before long many prairie and west coast communities were providing relief to unemployed workers.15 But worse was to follow – especially for immigrants unlucky enough to have been born in those countries which took up arms against the British Empire.

The outbreak of war in August 1914 forced the dominion government into a unique situation; to implement a comprehensive set of guidelines for immigrants from hostile countries. Of the persons classified as enemy aliens there were 393,320 of German origin, 129,103 from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, 3,880 from the Turkish Empire, and several thousands from Bulgaria.16 The dominion government’s position was set forth in a series of acts and proclamations, the most important being the War Measures Act of August 1914, which specified that during a ‘state of war, invasion, or insurrection … the Governor in Council may do and authorize such acts … orders and regulations, as he may … deem necessary or advisable for the security, defence, order and welfare of Canada.’ Specific reference was made to the following powers: censorship on all forms of communication and the arrest, detention and deportation of dangerous enemy aliens. Subsequent orders-in-council in October 1914 and September 1916 prohibited enemy aliens from possessing firearms and instituted a system of police and military registration. By end of the war over 80,000 enemy aliens had been registered, though only 8,579 of these were actually interned. This number included 2,009 Germans, 5,954 Austro-Hungarians, 205 Turks, 99 Bulgarians, and 312 classified as miscellaneous. These 8,579 prisoners of war were located in some twenty-four different camps, although most were placed in either Kapuskasing, Ontario, or Vernon, B.C.17

Although there were very few incidents of sabotage or espionage on the home front during the war, enemy aliens soon became the object of intense Anglo-Canadian hostility.18 This was particularly true of those enemy aliens categorized as Austrians, since most of them were immigrants of military age who retained the status of reservists in their old homeland.19 Throughout the fall of 1914 there were also alarming reports about what was afoot in the German-American communities of several American cities; one agent reported from Chicago that ‘should the Germans achieve a single success I believe that we in Canada are in danger of a repetition of the invasion of 1866 on a larger scale.’ What made the threat from the United States even more ominous was the steady flow of migrant labourers across a virtually unpatrolled border; many of those on the move were either enemy aliens or members of alleged pro-German groups such as Finns.20

The fear of a fifth column among unemployed and impoverished enemy alien workers was widespread.21 Conversely, they gave strong support to the notion that enemy aliens who had jobs should be turned out of them: in 1915 there were many dismissals for ‘patriotic’ reasons. This policy was popular among both Anglo-Canadian workers and immigrants from countries such as Italy and Russia, now allied with the British Empire.22 Some labour-intensive corporations, however, held a different point of view.23 The Dominion Iron and Steel Company, for example, resisted the pressure to dismiss their enemy alien employees on the grounds that Nova Scotia workers ‘would not undertake the rough, dirty jobs.’24 It was only when the company obtained an understanding from the dominion Immigration Branch that it could import even more pliable workers from Newfoundland that it agreed to join temporarily in the patriotic crusade.25 Elsewhere corporate resistance was even stronger. In June 1915 English-speaking and allied miners threatened strike action at Fernie, B.C., and Hillcrest, Alberta, unless all enemy alien miners were dismissed. The situation was particularly tense at Fernie, where the giant Crow’s Nest Coal Company initially baulked at this demand. Eventually a compromise was achieved: all naturalized married enemy alien miners were retained; naturalized unmarried enemy aliens were promised work when it was available; the remainder of the enemy alien work force, some 300 in number, were temporarily interned. Within two months, however, all but the ‘most dangerous’ had been released by dominion authorities.26

This action indicated that, despite severe local and provincial pressure, the Borden government was not prepared to implement a mass internment policy. The enormous expense of operating the camps and an antipathy to adopting ‘police state’ tactics partly explain the dominion government’s reluctance. There was also a suspicion in Ottawa that many municipalities wanted to take advantage of internment camps to get rid of their unemployed. Solicitor General Arthur Meighen articulated the view of the majority of the cabinet when he argued that instead of being interned, each unemployed alien should be granted forty acres of land which could be cultivated under government supervision; he concluded his case with the observation that ‘these Austrians … can live on very little.’27 By the spring of 1916 even the British Columbia authorities had come around to this point of view. One provincial police report gave this account of how much things had quieted down: ‘From a police point of view, there has been less trouble amongst them [aliens] since the beginning of the war than previously; the fact that several of them were sent to internment camps at the beginning of the war seemed to have a good effect on the remainder. … In my opinion, if there is ever any trouble over the employment of enemy aliens, it will be after the war is over and our people have returned.’28

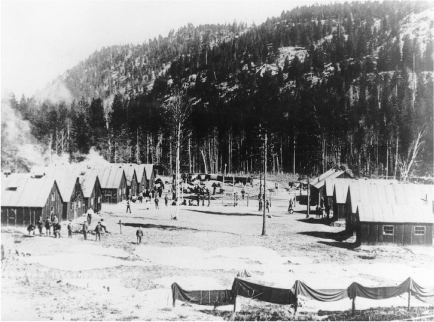

Internment Camp No. 2, Edgewood, British Columbia, ca. 1916 (National Archives of Canada, PA127065)

Yet the changed attitude in British Columbia also reflected a dramatically altered labour market. As the war progressed, serious labour shortages developed in both the province and the country. In the summer of 1915 there was a demand for about 10,000 harvest labourers in the Prairie provinces. Many of those who came to do the harvesting were unemployed enemy alien workers from the slums of Vancouver and Winnipeg who had their transportation subsidized by the dominion and western provincial governments.29 Government involvement in the recruitment of such workers was increased in 1916 when it became apparent that the supply of labour available on the Prairies would again be insufficient to meet the harvest demands. The dominion Immigration Branch now began placing advertisements in United States newspapers urging Americans to look northward for employment. Instructions were also issued to the agents of the branch that the money qualifications of the Immigration Act were to be relaxed. By the end of September 1916 over 5,000 harvesters had crossed the international border, attracted by generous wages ($3.50 a day) and cheap (1 cent per mile) rail fares from border points.30

Increasingly, the practice of securing industrial workers from the United States was also regarded as essential to the maintenance of the Canadian war economy. By an order-in-council of August 1916 the Alien Labour Act was temporarily shelved in order to facilitate the movement of industrial labour northward. Thousands of American residents were soon streaming into Canadian industrial communities,31 but after the entry of the United States into the war in 1917 this source of labour supply was abruptly cut off. Of necessity the focus of Canadian recruitment efforts now shifted overseas, most notably towards East Asia and the West Indies. The most ambitious proposal called for the importation of thousands of Chinese labourers on a temporary basis. But this solution met with the same violent objections it had always encountered from organized labour and nativist opinion, and it was ultimately rejected by the dominion government.32

Since an overseas solution seemed impossible, the new labour situation put a premium on the surplus manpower available in the country. As a result, the alien worker, whether of enemy extraction or not, became a very desirable quantity indeed. The implementation of conscription in the summer of 1917 only aggravated an already difficult situation; by the end of the year it was estimated that the country faced a shortage of 100,000 workers. From the spring of 1917 on, foreign workers found themselves not only wanted by Canadian employers, but actually being drafted into the industrial labour force by the dominion government.33 As of August 1916 all men and women over the age of sixteen were required to register with the Canadian Registration Board, and in April 1918 the so-called anti-loafing act provided that ‘every male person residing in the Dominion of Canada should be regularly engaged in some useful occupation.’34

As early as 1916 the dominion government had adopted the practice of releasing non-dangerous interned prisoners of war (POWs) under contract to selected mining and railway companies both to minimize the costs of operating the camps, and to cope with labour shortages. Not surprisingly, this policy was welcomed by Canadian industrialists, since these enemy alien workers received only $1.10 a day and were not susceptible to trade union influence.35 One of the mining companies most enthusiastic about securing large numbers of the POW workers was the Dominion Iron and Steel Corporation. In the fall of 1917 the president of the company, Mark Workman, suggested that his operation be allocated both interned and ‘troublesome’ aliens, since ‘there is no better way of handling aliens than to keep them employed in productive labour.’ In December 1917 Workman approached Borden, before the latter left for England, with the proposal that the POWs interned in Great Britain be transferred to the mines of Cape Breton Island. Unfortunately for the Dominion Steel Company, the scheme was rejected by British officials.36

The railway companies, particularly the Canadian Pacific, also received large numbers of POW workers. The reception of these workers harked back to some of the worst aspects of the immigrant navvy tradition of these companies. During 1916 and 1917 there was a series of complaints from POW workers, and on one occasion thirty-two Austrian workers went on strike in the North Bay district to protest dangerous working conditions and unsanitary living conditions. Neither the civil nor the military authorities gave any countenance to their complaints; the ultimate fate of these workers was to be sentenced to six months’ imprisonment at the Burwash prison farm ‘for breach of contract.’37

This coercion was symptomatic of a growing concern among both Anglo-Canadian businessmen and dominion security officials about alien labour radicalism. Not surprisingly, a 65 per cent increase in food prices between August 1914 and December 1917 created considerable industrial unrest, and the labour shortages which began developing in 1916 provided the trade unions with a superb opportunity to strike back. In 1917 there were a record number of strikes and more than 1 million man days were lost. Immigrant workers were caught up in the general labour unrest. In numerous industrial centres in northern Ontario and western Canada they demonstrated a capacity for effective collective action and a willingness to defy both the power of management and the state. The onset of the Russian Revolution in 1917 added to the tension in Canada by breathing new life into a number of ethnic socialist organizations.38

By the spring of 1918 the dominion government was under great pressure to place all foreign workers under supervision, and, if necessary, to make them ‘work at the point of a bayonet.’ The large-scale internment of radical aliens and the suppression of seditious foreign-language newspapers was also now widely advocated.39 In June 1918 C.H. Cahan, a wealthy Montreal lawyer, was appointed to conduct a special investigation of alien radicalism. In the course of his inquiry Cahan solicited information from businessmen, ‘respectable’ labour leaders, police officials in both Canada and the United States, and various members of the anti-socialist immigrant community in Canada. The report which Cahan submitted to cabinet in September 1918 was the basis of a series of coercive measures: by two orders-in-council (PC 2381 and PC 2384) the foreign language press was suppressed and a number of socialist and anarchist organizations were outlawed. Penalties for possession of prohibited literature and continued membership in any of these outlawed organizations were extremely severe: fines of up to $5,000.00 or a maximum prison term of five years could be imposed.40

The hatreds and fear stirred up by the First World War did not end with the Armistice of 1918; instead, social tension spread in ever-widening circles. Anglo-Canadians who had learned to despise the Germans and the Austro-Hungarians had little difficulty in transferring their aroused passions to the Bolsheviks. Though the guns were silent on the Western Front, Canadian troops were now being sent to Siberia ‘to strangle the infant Bolshevism in its cradle.’41 Within Canada, there was widespread agitation against potentially disloyal aliens and those involved in socialist organizations. An editorial in the Winnipeg Telegram summed up these sentiments: ‘Let every hostile alien be deported from this country, the privileges of which … he does not appreciate.’42

In the early months of 1919 the Borden government was deluged by a great wave of petitions demanding the mass deportation of enemy aliens. Enquiries were actually made by the dominion government concerning the possible implementation of a policy of mass expulsion. Surveys by the Department of Justice revealed that there were over 88,000 enemy aliens registered, 2,222 of whom were located in internment camps. There were also 63,784 Russian subjects in Canada, many of whom officials in Ottawa believed to be potentially hostile.43 The policy of mass deportation was rejected, however, because of both its likely international repercussions and the demands it would make on the country’s transportation facilities at a time when the troops were returning from Europe.44

The need to find jobs quickly for the returning soldiers also affected the situation of the foreign worker. Both politicians and businessmen faced a powerful argument in the claim that all enemy aliens should be turned out of their jobs to make way for Canada’s ‘heroes,’ but their actions were also motivated by the fear that the veterans would be radicalized and lured into socialist organizations if their economic needs were not immediately satisfied. By February 1919 the British Columbia Employers’ Association, the British Columbia Manufacturers’ Association, and the British Columbia Loggers’ Association all had announced that their memberships were prepared to offer employment to returned soldiers by dismissing alien enemies. This pattern was repeated in the mining region of northern Ontario, where in the early months of 1919 the International Nickel Company, for instance, dismissed 2,200 of their 3,200 employees, the vast majority of whom were foreigners.45 Even the CPR joined the ‘patriotic crusade’ of dismissals. As Vice-President D.C. Coleman put it, ‘The aliens who had been on the land when the war broke out and who went to work in the cities and towns, taking the jobs of the men who went to the front … [should] go back to their old jobs on the land.’46

But not even the land of the ‘men in sheepskin coats’ was now safe for the immigrant worker; rumours were abroad that the dominion government intended to cancel large numbers of homestead patents, and assaults on aliens by returned soldiers were commonplace.47 Even the usually passive Canadian Ruthenian denounced the harsh treatment which Ukrainians and other foreigners were receiving from the Anglo-Canadian community and the dominion government: ‘The Ukrainians were invited to Canada and promised liberty, and a kind of paradise. Instead of the latter they found woods and rocks, which had to be cut down to make the land fit to work on. They were given farms far from the railroads, which they so much helped in building – but still they worked hard … and came to love Canada. But … liberty did not last long. First, they were called “Galicians” in mockery. Secondly, preachers were sent amongst them, as if they were savages, to preach Protestantism. And thirdly, they were deprived of the right to elect their representatives in Parliament. They are now uncertain about their future in Canada. Probably, their [property] so bitterly earned in the sweat of their brow will be confiscated.’48 By the spring of 1919 the Borden government had received a number of petitions from ethnic organizations demanding either British justice or the right to leave Canada. The Toronto Telegram estimated that as many as 150,000 Europeans were preparing to leave the country. Some Anglo-Canadian observers warned, however, that mass emigration might relieve the employment problems of the moment, but in the long run it would leave ‘a hopeless dearth of labour for certain kinds of work which Anglo-Saxons will not undertake.’49

Concern about the status of the alien worker led directly to the appointment by the dominion government of the Royal Commission on Industrial Relations on 4 April 1919. The members of the commission travelled from Sydney to Victoria and held hearings in some twenty-eight industrial centres. The testimony of industrialists who appeared before the commission reveals an ambivalent attitude towards the alien worker. Some industrialists argued that the alien was usually doing work ‘that white men don’t want,’ and that it would ‘be a shame to make the returned soldier work at that job.’ But in those regions where there was high unemployment among returned soldiers and where alien workers had been organized by radical trade unions, management took a strikingly different view. William Henderson, a coal-mine operator at Drumheller, Alberta, informed the commission that the unstable industrial climate of that region could be reversed only by hiring more Anglo-Canadian workers, ‘men that we could talk to … men that would come in with us and co-operate with us.’ Many mining representatives also indicated that their companies had released large numbers of aliens who had shown radical tendencies; there were numerous suggestions that these aliens should not only be removed from the mining districts, but actually be deported from Canada.50

In the spring of 1919 Winnipeg was a city of many solitudes. Within its boundaries, rich and poor, Anglo-Saxon and foreigner lived in isolation. The vast majority of the white-collar Anglo-Saxon population lived in the south and west of the city; the continental Europeans were hived in the north end. This ethno-class division was also reflected in the disparity between the distribution of social services and the incidence of disease. Infant mortality in the North End, for example, was usually twice the rate in the Anglo-Saxon South End. The disastrous influenza epidemic which struck the city during the winter of 1918–19 further demonstrated the high cost of being poor and foreign.51

During January and February 1919 there was a series of anti-alien incidents in the city. One of the worst occurred on 28 January, when a mob of returned soldiers attacked scores of foreigners and wrecked the German club, the offices of the Socialist Party of Canada and the business establishment of Sam Blumenberg, a prominent Jewish socialist.52 Reports of the event in the Winnipeg Telegram illustrate the attitude adopted by many Anglo-Canadian residents of the city towards the aliens. The Telegram made no apologies for the violence; instead, the newspaper contrasted the manly traits of the Anglo-Canadian veterans with the cowardly and furtive behaviour of the aliens: ‘It was typical of all who were assaulted, that they hit out for home or the nearest hiding place after the battle.’53 Clearly, many Anglo-Canadians in the city were prepared to accept mob justice. R.B. Russell reported that the rioting veterans had committed their worst excesses when ‘smartly dressed officers … [and] prominent members of the Board of Trade’ had urged them on. Nor had the local police or military security officials made any attempt to protect the foreigners from the mob.54

At the provincial level, Premier Norris’s response to the violence was not to punish the rioters, but to establish an Alien Investigation Board, which issued registration cards only to ‘loyal’ aliens. Without these cards foreign workers not only were denied employment, but were actually scheduled for deportation. Indeed, the local pressure for more extensive deportation of radical aliens increased during the spring of 1919, especially after D.A. Ross, the provincial member for Springfield, publicly charged that both Ukrainian socialists and religious nationalists were armed with ‘machine guns, rifles and ammunition to start a revolution in May.’ The stage was now set for the Red Scare of 1919.55

The Winnipeg General Strike of 15 May to 28 June 1919 brought the elements of class and ethnic conflict together in a massive confrontation. The growing hysteria in the city was accompanied by renewed alien propaganda, a close cooperation between security forces and the local political and economic elite, and finally, attempts to use the immigration machinery to deport not only alien agitators but also British-born radicals. The sequence of events associated with the Winnipeg Strike has been well documented: the breakdown of negotiations between management and labour in the building and metal trades was followed by the decision of the Winnipeg Trades and Labour Council to call a general strike for 15 May. The response was dramatic: between 25,000 and 30,000 workers left their jobs. Overnight, the city was divided into two camps.56

On one side stood the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand, a group of Anglo-Canadian businessmen and professionals who viewed themselves as the defenders of the Canadian way of life on the Prairies. Their purpose was clear: to crush the radical labour movement in Winnipeg. In their pursuit of this goal the Citizens’ Committee engaged in a ferocious propaganda campaign against the opposing Central Strike Committee, both through its own newspaper, the Citizen, and through the enthusiastic support it received from the Telegram and the Manitoba Free Press. The committee’s propaganda was aimed specifically at veterans, and the strike was portrayed as the work of enemy aliens and a few irresponsible Anglo-Saxon agitators.57 John W. Dafoe, the influential editor of the Free Press, informed his readers that the five members of the Central Strike Committee – Russell, Ivens, Veitch, Robinson, and Winning – had been rejected by the intelligent and skilled Anglo-Saxon workers and had gained power only through ‘the fanatical allegiance of the Germans, Austrians, Huns and Russians.’ Dafoe advised that the best way of undermining the control which the ‘Red Five’ exercised over the Winnipeg labour movement was ‘to clean the aliens out of this community and ship them back to their happy homes in Europe which vomited them forth a decade ago.’58

Crowd gathered outside the Union Bank of Canada building on Main Street during the Winnipeg General Strike, Winnipeg, Manitoba, 21 June 1919 (National Archives of Canada, PA163001)

The Borden government was quick to comply. On 15 June the commissioner of the Royal North-West Mounted Police (RNWMP) indicated that one hundred aliens had been marked for deportation under the recently enacted section 41 of the Immigration Act, and that thirty-six were in Winnipeg. In the early hours of 17 June officers of the force descended on the residences of two Winnipeggers: six Anglo-Saxon labour leaders and four ‘foreigners.’ Ultimately, none of these men was summarily deported, as planned.59 In the case of the Anglo-Saxon strike leaders an immediate protest was registered by numerous labour organizations across the country. Alarmed by this uproar, the Borden government announced that it did not intend to use section 41 against British-born agitators either in Winnipeg or in any other centre.60

The foreigners arrested were not so fortunate. The violent confrontation of 21 June between the strikers and the RNWMP, in which scores of workers were injured and two killed, encouraged the hard liners in the Borden government. On 1 July a series of raids was carried out across the country on the homes of known alien agitators and the offices of radical organizations. Many of those arrested were moved to the internment camp at Kapuskasing, Ontario and subsequently deported in secret.61 In their attempts to deport the approximately 200 ‘anarchists and revolutionaries’ rounded up in the summer raids of 1919 the Immigration Branch worked very closely with United States immigration authorities. This cooperation was indicative of a link which was being forged between Canadian and American security agencies; the formation of the Communist Labour Party of America and the Communist Party of America in the fall of 1919 further strengthened this connection.62 The RNWMP and Military Intelligence also maintained close contact with the British Secret Service. Lists of undesirable immigrants and known communists were transmitted from London to Ottawa. Indeed, the Immigration Branch had now evolved from a recruitment agency to a security service.63

In time the repression of militant foreign workers took many different forms. In combating the woodworkers unions, the British Columbia Loggers’ Association implemented an extensive blacklisting system, particularly after the December 1919 loggers’ strike, calculated to purge all members of the IWW and One Big Union (OBU), as well as those ‘known to have seditious, radical or disloyal leanings.’64 In the Rocky Mountains coal-mining district the companies were also successful in withstanding a lengthy strike and purge of local radicals. In this effort both the international headquarters of the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), now concerned over the number of wildcat strikes and the growing radicalism in District 18, and the dominion government provided assistance. This meant that all members associated with the OBU were rejected for employment, while the political records of the remainder of the mining population were thoroughly investigated. A considerable number of alien workers in this region were also placed in internment camps.65 One of them, Timothy Koreichuk, a leading organizer for the Ukrainian Social Democrats in District 18, died while interned at Vernon, British Columbia. To the Ukrainian Labor News Koreichuk was a heroic victim of capitalist oppression: ‘Sleep and dream martyr! Your fervour for the struggle which you have placed in the hearts of all Ukrainian workers will remain forever.’66

The events of 1918–19 produced a spirited national debate on whether Canada should continue to maintain an open-door immigration policy. Since many Anglo-Canadians equated Bolshevism with the recent immigration from eastern Europe, support grew for policies similar to the quota system under discussion in the United States.67 The Winnipeg strike, the surplus of labour, and a short but sharp dip in the stock market sharply reduced the incentive for industrialists to lobby for the continued importation of alien workers. Even the Canadian Manufacturers’ Association, a long-time advocate of the open-door immigration policy, sounded a cautious note: ‘Canada should not encourage the immigration of those whose political and social beliefs unfit them for assimilation with Canadians. While a great country such as Canada possessing millions of vacant acres needs population, it is wiser to go slowly and secure the right sort of citizens.’ Ethnic, cultural, and ideological acceptability had temporarily triumphed over economic considerations. Whether Canada was prepared to accept a slower rate of economic growth in order to ensure its survival as a predominantly Anglo-Canadian nation now became a matter of pressing importance.68

The wartime national security provisions were extended to the Immigration Act during its 1919 revisions. Of paramount importance was section 41, which stipulated that ‘any person other than a Canadian citizen who advocates … the overthrow by force … of constituted authority’ could be deported from the country.69 This sweeping provision reinforced section 38 of the act, which gave the Governor General in council authority ‘to prohibit or limit … for a stated period or permanently the landing … of immigrants belonging to any nationality or race deemed unsuitable.’ By order-in-council PC 1203, Germans, Austrians, Hungarians, Bulgarians, and Turks were excluded because of their wartime association; PC 1204 barred Doukhobors, Mennonites, and Hutterites because of ‘their peculiar customs, habits, modes of living and methods of holding property.’70

Among European immigrants themselves the enemy alien hysteria and the Red Scare produced great bitterness, and many considered returning home during the summer of 1919, since their future prospects in Canada looked anything but promising. Certainly, there seemed little reason to believe that they could ever become part of the mainstream of Canadian life. In these circumstances Ukrainian, Finnish, and Russian organizations offered an alternative to the ‘Canadian Way of Life’ – an alternative that found sustenance in the achievements of Soviet communism.71 The distinctive outlook of Slavic and Finnish socialists in Canada was described as follows in a 1921 RCMP intelligence report: ‘If in earlier years they came sick of Europe, ready to turn their back on their homelands, and full of admiration for the native Canadian and Canadian civilization, they have changed their point of view. The war and revolution have roused their intense interest in Central Europe. They belong almost wholly to the poorest element in the community, and it is highly exciting to them to see the class from which they come, composed in effect of their own relatives, seize control of all power and acquire all property.’72 Such was the legacy of the year 1919 – the floodtide of radical labour politics in Canada.

Why was there such strong anti-immigrant sentiment among western Canadians during the First World War? And why did the federal government find it necessary to launch so many repressive measures, particularly during the period 1917–19, against groups deemed ‘un-Canadian?’ In part, this nativist campaign can be regarded as an intensification of pre-war bias when negative stereotypes of central Europeans was widespread. In these years, even prominent social reformers such as Reverend Charles W. Gordon (Ralph Connor) and James S. Woodsworth tended to equate immigrant poverty with immorality and ethnic festivals with debauchery and violence.73 RNWMP reports from western Canada also stressed the tendency of foreign workers to take the law into their own hands, the prevalence of knives and guns turning even minor disagreements into violent confrontations. The RNWMP also were distressed by their inability to apprehend labour agitators and ‘criminals,’ largely because ethnic communities often viewed the Law as ‘the enemy.’ This conspiracy of silence appeared particularly threatening in large ethnic ‘ghettos’ such as North End Winnipeg.

Yet another pre-war stereotype was the spectre of foreign agitators and demagogues who sought to disrupt and corrupt western Canadian society. Industrial unrest among immigrant workers, for instance, was usually blamed on anarchists, socialists, and syndicalists who, it was alleged, were able to mobilize the latent violence of the foreign worker. The possibility that the west would become ‘balkanized’ into a series of ethnic fiefdoms also preoccupied reformers prior to 1914 particularly in Manitoba, where the willingness of the Roblin government to exchange immigrant bloc votes for cultural concessions was vigorously denounced by prominent regional spokesmen such as John W. Dafoe, the influential editor of the Manitoba Free Press. These allegations about ‘un-Canadian’ activities gained even greater intensity during the 1917 wartime general election, when recent immigrants from Europe were disfranchised in the name of national security.74

Although the pre-war legacy is important, one should not underestimate the extent to which the war itself dramatically turned western Canadian public opinion against enemy aliens during the war years. As casualties mounted, propaganda about Germany and its allies became more and more vicious, and, according to one account, by 1917 ‘most Canadians … believed that they were fighting a people that inoculated its captives with tuberculosis, decorated its dwellings with human skin, (and) crucified Canadian soldiers.’ Not surprisingly, retaliation against the large and diversified German Canadian community was widespread, including internment, press censorship, confiscation of property, public ostracism, and mob violence. Throughout the war years punitive measures were also directed at Ukrainians and other former citizens of the Austro-Hungarian empire because of their dual loyalty, their predominantly working-class status, and their identification with Bolshevism, particularly during the 1919 Red Scare.

Yet it is instructive that the 1919 immigration restrictions were designed only as emergency measures. This was evident when the Union Government refused to impose a statutory prohibition against German immigration and instead relied upon more flexible orders-in-council. As a result, once the economy had recovered, Canada became an immigration nation once again, and between 1923 and 1930 over 400,000 Germans, Ukrainians, and other European immigrants entered the country, most of them gravitating towards the farms and resource industries of western Canada. In contrast, the numbers of overseas Chinese, Japanese, and East Indians allowed into the country were sharply reduced, while Asian Canadians living in British Columbia were still denied full civil rights.75 As ‘White’ immigrants, central Europeans were immediately candidates for Canadianization, although language, culture, occupation, and place of residence clearly set them apart from Anglo-Canadian society. This social distance was lengthened by the suspicion and hostility many newcomers felt when they discovered that Canada regarded them as second-class citizens. The words of Sandor Hunyadi, the fictional character created by John Marlyn in his book Under the Ribs of Death, vividly describe what Anglo-Winnipeg looked like from the immigrant North End: ‘“The English,” he whispered. “Pa, the only people who count are the English. Their fathers got all the best jobs. They’re the only ones nobody ever calls foreigners. Nobody ever makes fun of their names or calls them ‘bologny-eaters,’ or laughs at the way they dress or talk. Nobody,” he concluded bitterly, “cause when you’re English it’s the same as bein’ Canadian.”’76

Since the publication of Dangerous Foreigners in 1979, the scholarship dealing with ethnic and class conflict in western Canada during the First World War has greatly improved. In terms of scholarly debates, there are two subjects that have particular relevance for this chapter. The first was the specific wartime experience of the different European ethnic groups – notably those branded as enemy aliens. Not surprisingly, given their numbers and their strong sense of community, Ukrainian Canadians have been in the lead, demanding a redress of the wartime wrongs,77 a campaign that has been greatly enhanced by a range of historical studies on this topic.78 A second intriguing debate involves questions about the ‘exceptional’ radical character of the western Canadian labour movement, particularly during the period 1914–19.79 Although the full scope of the controversy cannot be assessed here, these revisionist studies have provided valuable insights into the role immigrant workers assumed, both in western Canada and elsewhere.80

Yet despite this impressive scholarship, there are still important themes that remain unexplored. For example, there is a great need to reassess how Chinese and Japanese residents of British Columbia coped with wartime harassment, how the ideological and religious differences within various European ethnic groups were intensified by four years of conflict, and what role immigrant women assumed in the various labour confrontations of that period, including the Winnipeg General Strike.81 These challenging subjects – and many others – await the attention of future historians of the Canadian west and the First World War.

1 The author has written extensively on this subject. See Donald Avery, ‘Dangerous Foreigners’: European Immigrant Workers and Labour Radicalism in Canada, 1896–1932 (Toronto, 1979); Reluctant Host: Canada’s Response to Immigrant Workers, 1896–1994 (Toronto, 1995); ‘The Radical Alien and the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919,’ in C. Berger and R. Cook, eds, The West and the Nation: Essays in Honour of W.L. Morton (Toronto, 1976).

2 Queen’s University Archives, Thomas Crerar Papers, Crerar to George Chipman, 15 April 1919.

3 O.J. Firestone, Canada’s Economic Development, 1867–1953 (London, 1958), 65.

4 Fifth Census of Canada, 1911 (Ottawa, 1912), 2, 42–4; Robert England, The Central European Immigrant in Canada (Toronto, 1929); George Haythorne and Leonard Marsh, Land and Labour: A Social Survey of Agriculture and the Farm Labour Market in Central Canada (Toronto, 1941), 213–30.

5 For early studies of the experience of European immigrant workers in the Canadian frontier see James Fitzpatrick, University in Overalls (Toronto, 1920), and Edmund Bradwin, The Bunkhouse Man (Toronto, 1928).

6 Ukrainian Rural Settlements, Report of the Bureau of Social Research (Winnipeg, 25 January 1917); J.W. Dafoe, Clifford Sifton in Relation to His Times (Toronto, 1931), 318–19; Canada, House of Commons Debates, 1905, 7686; ibid., 1911, 1611. There are also extensive references to this trend in National Archives of Canada (NAC), Immigration Branch (IB) Records, ff. 29490 and 195281.

7 For the more traditional view of the primacy of agricultural immigrants see Norman Macdonald, Canada, Immigration and Colonization, 1841–1903 (Toronto, 1968); Robert England, The Colonization of Western Canada (Toronto, 1936); and Harold Troper, Only Farmers Need Apply (Toronto, 1972).

8 American scholarship on the transatlantic movement of European immigrant workers is extensive. Two of the most useful studies are John Brodar, The Transplanted: A History of Immigrants to Urban America (Bloomington, Ind., 1987), and Gerald Rosenblum, Immigrant Workers: Their Impact on American Labor Radicalism (New York, 1973).

9 M.C. Urquart and K.A.H. Buckley, eds, Historical Statistics of Canada (Toronto, 1965), Series A, 133–42; Canada Manpower and Immigration, Immigration and Population Statistics, (Ottawa, 1974), 3: 7–15.

10 In 1891 approximately 98 per cent of the Chinese population was in British Columbia; although numbers declined somewhat during subsequent decades, 60 per cent of Canada’s Chinese were still in the province in 1921. In contrast, over 90 per cent of the Japanese and East Indian population lived in British Columbia until the Second World War. Peter Li, The Chinese in Canada (Toronto, 1982), 51.

11 Peter Ward, White Canada Forever: Popular attitudes and Public Policy towards Orientals in British Columbia (Montreal, 1978); Edgar Wickberg, ed., From China to Canada: A History of the Chinese Communities in Canada (Toronto, 1982).

12 Patricia Roy, A White’s Man’s Province: British Columbia’s Politicians and Chinese and Japanese Immigrants, 1858–1914 (Vancouver, 1989); Hugh Johnston, The Voyage of the Komagata Maru: The Sikh Challenge to Canada’s Colour Bar (Delhi, 1979).

13 Ross McCormack, Reformers, Rebels and Revolutionaries: The Western Canadian Radical Movement, 1899–1919 (Toronto, 1978); Mark Leier, Where the Fraser Flows: The Industrial Workers of the World in British Columbia (Vancouver, 1990).

14 Labour Gazette (1914), 286–332, 820–1.

15 This report appeared in the Winnipeg-based Ukrainian newspaper Robotchny Narod, 14 March 1914. Other newspapers claimed that over 3,000 Bulgarian navvies had returned to Europe during the fall of that year.

16 Fifth Census of Canada, 1911 (Ottawa, 1912), 2: 367; J.C. Hopkins, ed., Canadian Annual Review of Public Affairs (CAR) 1915 (Toronto, 1914–18), 353.

17 Revised Statutes of Canada, 1927, chap. 206, vol. 4, 1–3; Canadian Gazette, 15 August 1914. NAC, Sir Robert Borden Papers (BP), 56666, C.H. Cahan to C.J. Doherty, 14 September 1918.

18 Canadian citizens of African-Canadian, Chinese, Japanese, East Indian, and Aboriginal backgrounds also encountered discrimination during the war years. One of the most blatant was the way volunteers from these groups were treated by the Canadian military establishment. Although about 5,000 Indians, 1,000 Blacks and several hundred Chinese and Japanese enlisted in the Canadian forces, they were predominantly assigned to low-status jobs in the construction or forestry units overseas. See James Walker, ‘Race and Recruitment in World War I: Enlistment of Visible Minorities in the Canadian Expeditionary Force,’ Canadian Historical Review 70, 1 (March 1989), 26.

19 Major General W.D. Otter, Internment Operations, 1914–20 (Ottawa, 30 September 1920), 2, 6, 12; CAR, 1916, 433.

20 CAR, 1916, 433; Joseph Boudreau, ‘The Enemy Alien Problem in Canada, 1914–1921,’ unpublished PhD thesis, University of California, 1964, 50–103.

21 Canadian Ruthenian, 1 August 1914.

22 NAC, Department of Militia and Defence Headquarters (DND), f. C-965 #2, Report, Agent J.D. Sisler, 9 August 1914. There were numerous other reports in this file.

23 Some of the strongest support for internment camps came from prominent citizens in heterogeneous communities. In Winnipeg, for example, J.A.M. Aikins, a prominent Conservative, warned that the city’s enemy aliens might take advantage of the war ‘for the destruction of property, public and private.’ NAC, BP, 106322, Aikins to Borden, 12 November 1914.

24 Canadian Mining Journal, 15 August 1914.

25 NAC, IB, f. 775789, T.D. Willans, travelling immigration inspector to W.D. Scott, 9 June 1915; D.H. McDougall, general manager, Dominion Iron and Steel Corporation, 29 May 1915.

26 Northern Miner (Cobalt) 9 October 1915; CAR, 1915, 355; NAC, DND, file 965, No. 9, Major E.J. May to Colonel E.A. Cruickshank, district officer in command of military district #13, 28 June 1915.

27 Otter, Internment Operations, 6–12; NAC, Arthur Meighen Papers (MP), 106995, Meighen to Borden, 4 September 1914. The European dependants of these alien workers obviously had to live on even less, because after August 1914 it was unlawful to send remittances of money out of the country. NAC, Chief Press Censor Papers, vol. 196, Livesay to Chambers, 4 December 1915.

28 British Columbia Provincial Archives (BCPA), British Columbia Provincial Police (BCPP), file 1355–7, John Simpson to Chief Constable of Greenwood to Colin Campbell, supt of the BCPP, 26 January 1916.

29 NAC, IB, f. 29490, No. 4, W. Banford, Dominion immigration officer to W.D. Scott, 13 May 1915; BCPA, Sir Richard McBride Papers, McBride to Premier Sifton (Alta), 30 June 1915. About 20,000 Canadian troops had also been used in gathering the harvest during 1915.

30 NAC, IB, f. 29490, No. 6, W.D. Scott, ‘Circular Letter to Canadian Immigration Agents in the United States,’ 2 August 1916.

31 NAC, Sir Joseph Flavelle Papers, 74, Scott to Flavelle, director of imperial munitions, 11 August 1916; IB, f. 29490, No. 6, J. Frater Taylor, president of Algoma Steel to Flavelle, 17 August 1917. The number of American immigrants entering the country was 41,779 in 1916 and 65,739 in 1917.

32 China provided over 50,000 labourers to the Allied cause. They were transported from Vancouver to Halifax in 1917 for service in France. British Columbia Federationist, 18 January 1918; Vancouver Sun, 7 February 1918; Harry Con et al., From China to Canada: A History of the Chinese Communities of Canada (Toronto, 1982), 119.

33 NAC, IB, f. 75789, A. Macdonald, Employment Agent, Dominion Coal Company to Scott, 25 July 1916.

34 CAR, 1918, 330; ibid., 1916, 325–8; Statutes of Canada, 9–10 Geo. v, xciii. The reaction of the Trades and Labor Congress to the treatment of enemy alien workers varied. On one hand, they endorsed the ‘patriotic’ dismissals in 1915; by 1916, however, the congress executive was concerned that the dominion government intended to use large numbers of enemy aliens as cheap forced labour. Proceedings of the Thirty-First Annual Session of the Trades and Labor Congress of Canada, 1915 (Ottawa, 1915), 16–17; ibid., 1916, 43.

35 Otter, Internment Operations, 9–14; NAC, Secretary of State Papers, Internment Operation Section, file 5330, No. 7, Major Dales, Commandant Kapuskasing to Otter, 14 November 1918; Desmond Morton ‘Sir William Otter and Internment Operations in Canada During the First World War,’ Canadian Historical Review 55 (March 1974), 32–58.

36 NAC, BP, f. 43110, Mark Workman to Borden, 19 December 1918; ibid., 43097, Borden to A.E. Blount, 1 July 1918.

37 CAR, 1915, 354; Internment Operation Papers, Otter to F.L. Wanklyn, CPR, 12 June 1916.

38 McCormack, Rebels, Reformers and Revolutionaries: The Western Canadian Radical Movement, 1899–1919 (Toronto, 1977), 143–216; Francis Swyripa and John Herd Thompson, eds, Loyalties in Conflict: Ukrainians in Canada During the Great War (Edmonton, 1983).

39 NAC, DND, C-2665, Major-General Ketchen, officer commanding Military District 10, to secretary of the Milita Council, 7 July 1917; Department of Justice Papers, 1919, file 2059, Registrar of Alien Enemies, Winnipeg, to Colonel Sherwood, Dominion Police, 17 August 1918; CPC, 144–A-2, Chambers to secretary of state, 20 September 1918.

40 NAC, BP, f. 56656, C.H. Cahan to Borden July 20, 1918; BP, f. 56668, Cahan to Borden, 14–20 September 1918, 45; BP, f. 56668, Cahan to Borden, 14 September 1918. The fourteen illegal organizations also included the IWW, the Group of Social Democrats of Anarchists, the Chinese Nationalist League, and the Social Democratic Party; the latter organization was removed from the list in November 1918. NAC, BP, f. 56698, Cahan to Borden, 21 October 1918; Statutes of Canada, 1919, 9–10 Geo. v, lxxi–lxxiii.

41 James Eayrs, In Defence of Canada: From the Great War to the Great Depression (Toronto, 1967), 30.

42 Winnipeg Telegram, 28 January 1919.

43 NAC, Internment Operations, f. 6712, Major General Otter to acting minister of justice, 19 December 1918; Justice Records, 1919, vol. 227, Report, chief commissioner Dominion Police to director of public safety, 27 November 1918.

44 NAC, BP, f. 83163, Sir Thomas White to Borden, 31 February 1919. On 28 February 1919 the German government lodged an official complaint with British authorities over ‘the reported plan of the Canadian government to deport all Germans from Canada.’ IB, f. 912971, Swiss ambassador, London, England to Lord Curzon, 28 February 1919.

45 Vancouver Sun, 26 March 1919; Department of Labour Library, Mathers Royal Commission on Industrial Relations, ‘Evidence,’ Sudbury hearings, 27 May 1919, testimony of J.L. Fortin, 1923.

46 Montreal Gazette, 14 June 1919.

47 In April 1918 an amendment to the Dominion Land Act denied homestead patents to non-naturalized residents; the subsequent amendments to the Naturalization Act in June 1919 also made it extremely difficult for enemy aliens to become naturalized. NAC, Department of Justice Papers, 1919, f. 2266, Albert Dawdron, acting commissioner of the Dominion Police, to the minister of justice, 28 July 1919; Statutes of Canada, 1918, 9–10 Geo. v, c. 19, s. 7; House of Commons Debates, 1919, 4118–33.

48 NAC, Chief Press Censor, 196–1, E. Tarak to Chambers, 11 January 1918 (translation), 91; IB, f. 963419, W.D. Scott to James A. Calder, minister of immigration and colonization, 11 December 1919; Toronto Telegram, 1 April 1920; MP, f. 000256, J.A. Stevenson to Meighen, 24 February 1919; Canadian Ruthenian, 5 February 1919.

49 NAC, IB, f. 963419, W.D. Scott to James Calder, minister of Immigration and Colonization, 11 December 1919; Toronto Telegram, 1 April 1919; NAC, Meighen Papers, 0000256, J.A. Stevenson to Meighen 24 February 1919.

50 Department of Labour Library, Mathers Royal Commission, ‘Evidence,’ Victoria hearings, testimony of J.O. Cameron, president of the Victoria Board of Trade; ibid., Calgary hearings, testimony of W. Henderson; ibid., testimony of Mortimer Morrow, manager of Canmore Coal Mines.

51 Alan Artibise, Winnipeg: A Social History of Urban Growth, 1874–1914 (Montreal, 1975), 223–45, Manitoba Free Press, 3 November 1918.

52 NAC, DND, C-2665, Secret Agent No. 47, Report (Wpg), to Supt Starnes, RNWMP, 24 March 1919.

53 Winnipeg Telegram, 29 January 1919.

54 Public Archives of Manitoba, OBU Collection, R.B. Russell to Victor Midgley, 29 January 1919.

55 Manitoba Free Press, 7 May 1919; Western Labor News, 4 April 1919. The Alien Investigation Board was legitimized by the passage of order-in-council PC 56 in January 1919, which transferred authority to investigate enemy aliens and to enforce PC 2381 and PC 2384 from the dominion Department of Justice to the provincial attorney general. Between February and May the board processed approximately 3,000 cases, of which 500 were denied certificates. RCMP Records, Comptroller to Commissioner Perry, 20 March 1919; Manitoba Free Press, 7 May 1919, 83. NAC, MP, 000279, D.A. Ross to Meighen, 9 April 1919.

56 D.C. Masters, The Winnipeg General Strike (Toronto, 1959), 40–50; David Bercuson, Confrontation at Winnipeg (Montreal 1974), 103–95.

57 Murray Donnelly, Dafoe of the Free Press (Toronto, 1968), 104; RCMP Records, 1919, vol. 1, Major-General Ketchen to secretary of the Militia Council, 21 May 1919; Winnipeg Citizen, 5–20 June 1919.

58 Manitoba Free Press, 22 May 1919.

59 NAC, BP, 61913, Robertson to Borden, 14 June 1919; BP, diary entries 13–17 June; RCMP Records, CIB, vol. 70, J.A. Calder, to Commissioner Perry, 16 June 1919; IB, f. 961162, Calder to Perry, 17 June 1919.

60 Tom Moore to E. Robinson, 24 June 1919 cited by Manitoba Free Press, 21 November 1919; NAC, BP, diary entry 20 June 1919; NAC, BP, f. 61936, Robertson to Acland, 14 June 1919; Manitoba Free Press, 18 June 1919.

61 Ukrainian Labor News, 16 July 1919; Norman Penner, ed., Winnipeg: 1919: The Strikers’ Own History of the Winnipeg General Strike (Toronto, 1973), 175–81; NAC, IB, f. 912971, No. 3, T.J. Murray, Telegram to J.A. Calder, 30 October 1919; Department of Justice Records, 1919, file 1960, deputy minister of justice, to Murray and Noble, 5 November 1919.

62 In October 1918 the United States Congress had passed an amendment to the ‘Act to Exclude and Expel from the United States Aliens Who Are Members of the Anarchist and Similar Classes’; Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman and 247 other ‘Reds’ were deported to Russia under this measure in December 1919. John Higham, Strangers in the Land (New York 1966), 308–24; NAC, IB, f. 961162, No. 1, F.C. Blair, secretary of immigration and colonization, memorandum to J.A. Calder 24 November 1919; ibid., John Clark, American Consul-General, Montreal, to F.C. Blair, 19 June 1920.

63 NAC, IB, f. 961162, assistant director RCMP (CIB division) to F.C. Blair 4 August 1920; William Rodney, Soldiers of the International: A History of the Communist Party of Canada, 1919–1929 (Toronto, 1968), 7–21.

64 UBC Archives, British Columbia Loggers’ Association Minute Book, 8 August, 12 December 1919.

65 Glenbow Institute (Calgary), Western Coal Operator Association Collection (WCOA). W.R. Wilson, president of the Crow’s Nest Coal Company to W. McNeill, president of the WCOA 2 September 1919; ibid., Samuel Ballantyne, chairman of the UMWA International Commission to MacNeill 2 September 1919. See also Allen Seager, ‘Class, Ethnicity and Politics in the Alberta Coalfields, 1905–1945,’ in Dirk Hoerder, ed., Struggle a Hard Battle: Essays on Working-Class Immigrants (DeKalb, Ill., 1986).

66 Ukrainian Labor News, 29 October 1919.

67 In addition to the pressure to exclude enemy aliens and pacifists, there was considerable support for the suggestion that Canada should not accept immigrants from certain regions because of their alleged racial deficiencies. Hume Conyn, MP for London, Ontario, cited the writings of eugenist writer Madison Grant as justifying the exclusion of ‘strange people who cannot be assimilated.’ Higham, Strangers in the Land, 308–24; House of Commons Debates, 1919; 1916, 1969, 2280–90.

68 Industrial Canada (July 1919), 120–22. Maclean’s (August 1919), 46–9. Wellington Bridgman’s Breaking Prairie Sod (Toronto, 1920) is an extreme example of the western Canadian backlash towards European immigrants.

69 ‘An Act to amend an Act of the present session entitled An Act to amend The Immigration Act 1919,’ Statutes of Canada, 1919, 9–10 Geo. V, ch. 26, s. 41.

70 PC 1203 and PC 1204 were enacted on 9 June 1919. Statutes of Canada, 1919, 9–10 Geo. v, vols 1–11, X; NAC, IB, f. 72552, no. 6, F.C. Blair, secretary, Department of Immigration and Colonization, to deputy minister, 11 August 1921.

71 NAC, DND, C-2817 Major General Gwatkin to S.D. Meuburn, minister of militia, 5 August 1919; IB, f. 563236, No 7, deputy attorney general of Ontario to F.C. Blair 6 November 1919; Ivan Avakumovic, The Communist Party in Canada: A History (Toronto, 1975), 1–53.

72 Surveillance of communist ‘infiltrators continued throughout the 1920s. NAC, Department of Justice, 1926, file 293, C. Starnes to deputy minister of justice, 27 October 1926; Avakumovic, Communist Party in Canada, 1–53; Barbara Roberts, Whence They Came: Deportation from Canada, 1900–1935 (Ottawa, 1988), 71–97, 125–58.

73 Ralph Connor, The Foreigner (Toronto, 1909); J.S. Woodsworth, Strangers Within Our Gates (Toronto, 1909).

74 John Herd Thompson, ‘The Enemy Alien and the Canadian General Election of 1917,’ in Swerpa and Thompson, Loyalties in Conflict, 25–47.

75 Li, Chinese in Canada, 50–65; Kay Anderson, Vancouver’s Chinatown: Racial Discourse in Canada, 1875–1980 (Montreal and Kingston, 1991), 49–160.

76 John Marlyn, Under the Ribs of Death (Toronto, 1957), 18.

77 L.Y. Luciuk, A Time for Atonement: Canada’s First Internment Operations and the Ukrainian Canadians, 1914–1920 (Kingston, 1988); L.Y. Luciuk and S. Hryniuk, eds, Canada’s Ukrainians: Negotiating an Identity (Toronto, 1991); L.Y. Luciuk and R. Sydoruk, In My Charge: The Canadian Internment Camp Photographs of Sergeant Willian Buck (Kingston, 1997); L.Y. Luciuk, N. Yurieva, and R. Zakaluzny, eds, Roll Call: Lest We Forget (Kingston, 1999); Lubomyr Luciuk, Searching for Place: Ukrainian Displaced Persons, Canada, and the Migration of Memory (Toronto, 2000).

78 Other studies on the internment of Ukrainian Canadians include M. Lupul, ed., A Heritage in Transition: Essays in the History of Ukrainians in Canada (Toronto, 1982); O. Martynowych, Ukrainians in Canada : The Formative Years (Edmonton, 1991); F. Swyripa, Ukrainian-Canadians: A Survey of Their Portrayal in English-Canadian Works (Edmonton, 1978); P. Yuzyk, The Ukrainians in Manitoba: A Social History (Toronto, 1953).

79 The major advocates for western radical exceptionalism were Masters, Winnipeg General Strike, McCormack, Reformers, Rebels, and Revolutionaries, Martin Robin, Company Province, Vol. 1, The Rush for Spoils (Toronto, 1972), and Bercuson, Confrontation at Winnipeg, and Fools and Wisemen: The Rise and Fall of the One Big Union. This viewpoint has been challenged by a number of historians, notably Greg Kealey, ‘1919: The Canadian Labour Revolt,’ Labour / Le Travail 13 (Spring 1984) 11–44; David Frank and Nolan Reilly, ‘The Emergence of the Socialist Movement in the Maritimes, 1899–1916,’ in R.J. Brym and R.J. Sacouman, eds, Underdevelopment and Social Movements in Atlantic Canada (Toronto, 1979); Suzanne Morton, ‘Labourism and Economic Action: The Halifax Shipyards Strike of 1920,’ Labour / Le Travail 22 (Fall 1988), 67–98; and James Naylor, The New Democracy: Challenging the Social Order in Industrial Ontario, 1914–25 (Toronto, 1991).

80 Since the mid-1970s there have been a number of studies dealing with the convergence of ethnicity and class within the western Canadian labour movement. They include Stanley Scott, ‘A Profusion of Issues: Immigrant Labour, the World War, and the Cominco Strike of 1917,’ Labour / Le Travail 2 (Spring 1977), 54–78; Jim Tan, ‘Chinese Labour and the Reconstituted Social Order in British Columbia,’ Canadian Ethnic Studies 19, 3 (1987), 68–88; Gillian Creese, ‘Organizing against Racism in the Workplace: Chinese Workers in Vancouver before the Second World War,’ Canadian Ethnic Studies 19, 3 (1987), 35–46; Allen Seager, ‘Socialist and Workers: The Western Canadian Coal Miners, 1900–21,’ Labour / Le Travail 16 (Fall 1995); John Kolasky, The Shattered Illusion: The History of Ukrainian Pro-Communist Organizations in Canada (Toronto, 1979).

81 There are a number of important studies in which the pivotal role immigrant women assumed within the Canadian labour movement is analyzed. For three different perspectives see Ruth Frager, Strife, Class, Ethnicity, and Gender in the Jewish Labour Movement of Toronto, 1900–1939 (Toronto, 1992); Varpu Lindstrom, Defiant Sisters: A Social History of Finnish Immigrant Women in Canada (Toronto, 1988); Frances Swyripa, Wedded to the Cause: Ukrainian Women and Ethnic Identities, 1891–1991 (Toronto, 1993).