PAUL LITT

When he stepped to the podium to address the Canadian Club of Montreal in December 1913, B.K. Sandwell had a novel topic for his audience. They were used to hearing about pressing political issues – imperial unity, the tariff, labour unrest – not frivolities like the theatre. But the drama critic maintained that his beat was ‘a realm in which a vast and ever-increasing number of Canadians acquire a large part of their ideas and opinions.’ Unfortunately, the plays Canadians saw were selected by ‘two groups of gentlemen from New York City’ who had come to dominate the business over the previous ten or fifteen years. They saw the continent as an open field in which to reap profits from their investments and had consolidated the sector so efficiently that Canadian theatre companies were squeezed out. ‘The situation is without a parallel in history,’ Sandwell complained, ‘You may look in vain in a country such as Poland, occupied and administered by an alien conqueror, for any such foreign domination of the Polish stage as exists in Canada, although Canada has not been even invaded for the last hundred years, to say nothing of being conquered. Such a situation could only have come about by a gradual process – have stolen upon us, as it were, unawares.’

However it came about, the situation was, to Sandwell’s mind, unhealthy for a ‘nation in the making.’ American productions purveyed interests and values that were American, not Canadian (or British, which were equally acceptable). Representative of the base republican culture of their origin, this ‘pabulum’ featured ‘grafting aldermen,’ ‘brutal detectives,’ and ‘odoriferous garbage collectors.’ The only silver lining Sandwell could see was that Canadian audiences were, in his estimation, more scrupulous than their Yankee counterparts and therefore less likely to be influenced by such trash.1

Sandwell’s complaint fit into a tradition of Canadian nationalist concern about the influence of American culture that stretches from before Confederation to the present day. What makes his concerns interesting for our present purposes is the historical moment at which they were expressed. Less than a year later, Canada would be swept up in the Great War, a cataclysm that would consume the country for half a decade, spurring Canadian nationalist sentiment to new heights and generating some of the most intense anti-Americanism in the country’s history. In this context one might have expected to see Canadians take action on Sandwell’s complaint. In fact, they proved relatively ineffectual in dealing with the issue. In this chapter I explore why this was so. I focus on the main channels through which culture flowed in wartime Canada, the cultural products that flowed along them, and the interests that controlled the channels – specifically the voluntary sector, the private sector, and government.2 I argue that nationalist responses to continental mass culture were limited by the biases of leading cultural nationalists, by the economic interests of Canadian cultural industries, and by government reluctance to intervene in the marketplace. These factors determined how cultural nationalism would affect Canadian society both during and after the war.

Three months after Sandwell’s appearance, the Canadian Club of Montreal invited another representative of the arts to speak. This time the topic was literature; the speaker, popular historian and journalist Beckles Willson, fresh from a sojourn in England, where he had achieved a modest fame by publishing popular fiction and ingratiating himself into polite society. Willson’s talk amplified many of Sandwell’s themes, spelling out more explicitly the cultural critic’s view of the role of culture in Canadian society. Material things were trivial, he contended, compared with ‘the mind and intellectual tastes, tendencies and achievements’ that confirmed Canadians’ ‘status as a civilized people.’ Culture had work to do in improving Canadians and bolstering their country’s international status. It also gave them ‘heroism, love, suffering, romance,’ essential ingredients of a collective identity. ‘Romance adds to a country,’ Willson explained, ‘peoples it with good spirits, invests it with associations, endears it to those who dwell in it and call it home!’3

Humanism, a sense of social responsibility, and anglophilia characterized Canada’s leading cultural nationalists. For them, culture was the arts and letters; its purpose was not merely to entertain, but to edify. Canada, they believed, should develop a refined cultural life that would improve the minds and hone the aesthetic sensibilities of its citizens and win it recognition among civilized nations. To do so it need only build upon the rich cultural tradition it had inherited from Britain and gradually wean itself from those crude pastimes of frontier days perpetuated so regrettably by its republican neighbour.

For all their firm ideas on matters cultural, neither Sandwell nor Willson offered much in the way of a practical program for promoting the type of superior Canadian culture they advocated. Both recognized that Canada’s cultural predicament was the result of the oligarchical workings of free markets, but neither questioned the fundamentals of the economic system. Instead, they appealed to their audiences to exercise their buying power as consumers in support of Canadian products. They also felt that government should do something to foster Canadian culture. Their conception of what government could do, however, was extremely limited: it could give awards, perhaps, or subsidize artists – although neither Sandwell nor Willson seemed to hold out much hope that it ever would. Willson had an additional, somewhat specific proposal: the Canadian Clubs should sponsor a circulating library of Canadian literature in every town. When neither the workings of the market nor government intervention offered any hope, the only recourse lay in the voluntary sector.

The idea that a circulating library of instructive Canadiana could counter the effects of continental mass culture may seem quaint, but it reflected the culturati’s equation of culture with the artistic and intellectual life of a community. No two communities were alike, of course; their character varied with their size, region, economy, ethno-cultural character, and other variables. But it is possible to identify some common features of community cultural activities in Edwardian Canada. Much of this type of cultural activity was amateur, participatory, and integrated with community traditions and institutions. Church choirs, for example, played a prominent role in the local music scene. They trained a roster of singers, who could be drawn upon for musical productions ranging from concerts of religious or classical pieces to Gilbert and Sullivan operettas. The local opera house, music hall, or theatre often hosted such productions, along with plays staged by amateur theatrical societies. The importance of performing arts in community life was demonstrated by the existence of these venues in centres small and large, the larger communities boasting purpose-built, stand-alone facilities, the smaller ones a multi-purpose hall, sometimes part of the town hall or a downtown commercial block, and frontier towns making do with whatever they could find. These spaces also served as meeting places for painting classes or arts and crafts clubs. In some towns they provided rehearsal space for the town band.

Local cultural activities often were run on a voluntary basis by middle-class community leaders such as the librarian, the church organist and choirmaster, the minister, or the schoolteacher. The presence of these religious and educational leaders in community activities associated with character formation was not surprising. For similar reasons, convention accorded women fuller participation in the arts than they enjoyed in other parts of public life. Such pursuits had social purposes congruent with the middle-class woman’s role as guardian of family respectability and community moral standards. They articulated aesthetic distinctions that signalled social status and demarcated class. They also served the evangelical impulse to save the lower orders and wayward bourgeois by offering a salutary alternative to the pool hall, the tavern, or the cockfight.

The resolute high-mindedness of cultural leaders from the local to the national levels was a response to the dangers they perceived in contemporary culture. Indeed, their insistence on cultural propriety belied the temptations of pleasurable entertainment that were available everywhere in wartime Canada. ‘Serious’ theatre presented everything from stark tragedies to light-hearted comedies, while vaudeville offered a serial carnival of minstrel shows, song-and-dance men, patter comedians, balladeers, acrobats, jugglers, and animal acts. It was, as Robertson Davies later remarked, the light-entertainment equivalent of television today. Canadians took steamboat excursions, visited amusement parks, rocketed around roller rinks, danced to the latest song, or – prior to Prohibition – fraternized in the hotel bar. The world of print was equally diverse. There were magazines and newspapers for different ethnic groups, regions, religious denominations, trades, professions, classes, and industries. The public consumed vast amounts of sentimental and sensational pulp fiction, including romances, adventures, detective and crime stories, westerns, mysteries, even anthropomorphized animal stories. Those who wanted at least the appearance of being more cultured could acquire cheap reprints of literary classics with decorative matching covers that looked impressive on the bookshelf. Variety distinguished the music scene as well. Records offered performances by famous opera stars such as Caruso, Adelina Patti, or Francesco Tamagno, but consumers could also buy ragtime, jazz, folk, or comedy. Sheet music for popular hits was stored in the piano bench alongside classics by composers such as Mozart and Beethoven.

The rage for ragtime music during the war was an example of mass culture’s capacity for absorbing new styles from subcultures for mainstream consumption. Ragtime took the ‘ragged’ beat of southern Black music and applied it to European song styles, creating a popular new musical style. It served as accompaniment for faster, more sinuous dances – similarly adapted from southern Black culture and popularized by minstrel shows, vaudeville, dance bands, and movies.4 Music and dance went together, of course. Dance crazes such as the foxtrot, the crab-step, even the tango – once deemed the ‘dance of the brothel’ – swept North American cities. Bob Edwards, editor of the Calgary Eye Opener, was not amused: ‘It is said that modern music is merely a reversion to the cave man’s foot-stamping and tom-tom beating,’ he commented. ‘This is quite likely. Anyone who visits a cabaret may hear not only the tom-tom beating but the footstomping – yes, and see the cave man dragging the cave lady about the floor.’5 But Edwards was behind the times; the growing acceptance by the middle class of dancing in commercial dance halls was a notable development of the war years. Times were changing.

The cornucopia of contemporary cultural offerings was consumed, of course, in different ratios and quantities by different individuals in different settings and circumstances. As a general rule the more urban and affluent were exposed to novelty earlier and more often than were their poorer or more rural compatriots. Journalist Bruce Hutchinson, who grew up ‘poor but comfortable’ in suburban Victoria, recalled that his family’s one extravagance was serious theatre. His mother would scrimp to buy gallery tickets for the touring production at the local quality playhouse, the Royal Victoria. Hutchinson’s cultural tastes might be labelled highbrow: he was a member of the debating team at his high school, acted in the dramatic society’s productions, and read ‘Scott, Dickens, Thackeray, Maupassant, and Conrad’ (all purchased second hand or borrowed from the public library). But he also played lacrosse and hockey, and his family attended movies more often than the theatre because it cost them only 10¢ each to see the latest feature.6

The novelty, diversity, and affordability of cultural products was but one manifestation of the constant and accelerating change affecting all facets of Canadian society. Canadian cities, and then towns, were increasingly wired for electricity and telephone (‘Oh! What a Difference since the Hydro Came’ ran the title of a 1912 hit song by Claude Graves, a printer from London, Ontario). South of the border, Henry Ford compressed the time it took to build a Model T automobile from twelve hours and twenty-eight minutes in 1910 to one hour and thirty-three minutes in 1915. Prices plummeted, making tin Lizzies affordable for the average family. By war’s end, 276,000 Canadians owned a car, four times as many than at the beginning of the conflict. Social mores were changing, as well. Moral arbiters such as the Methodist Church had proscriptions against the theatre, dancing, card playing, and drinking, but these injunctions weren’t followed religiously by Methodists, let alone the public at large.7 The flouting of traditional mores was symbolized by the New Woman, a media caricature of unconventional new female behaviour. The New Woman dared to bicycle, play tennis or golf. She dared to don a duster, goggles, and cap and go motoring. She dared to abandon stiff, layered dresses in favour of looser, lighter, more natural clothing. Out went the corset in favour of a new invention, the practical brassiere (‘A very dainty piece of lingerie designed to impart beauty and grace,’ according to one ad). On went rouge and lipstick. The New Woman did all of this, yet she still went to church. Perhaps she had more reason to go than ever before.

Arts organizations were themselves changing along with the changing times. New transportation and communication links were allowing them to network over larger territories. The voluntary sector took advantage of these developments to organize on a regional scale. Music festivals, for example, developed in various regions in the years before the war (the same type of growth was evident in contemporary sports leagues).8 The next step up from regional networks was, of course, national organization. The various Christian churches – with their national executives, regional administrations, and chapters in almost every community – provided a model for organizing on a national scale that was emulated by voluntary organizations such as the Women’s Institute, the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire, and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, all of which promoted variations of the churches’ social agendas. The Canadian Club of Montreal, the organization that Sandwell and Willson addressed before the war, was part of a national voluntary organization founded twenty years earlier to foster national consciousness. These organizations had blazed a trail that voluntary arts organizations would follow.

In the war years, however, the organization of Canada’s voluntary cultural sector paled in comparison with the continent-spanning achievements of the entertainment businesses. As Sandwell had noted in his indictment of theatre, cultural industries had been reconstituted on a continental scale through a process of technological innovation, capital investment, and rationalization that characterized the growth of big business in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Touring circuses, minstrel acts, Wild West shows, and vaudeville companies followed the rail lines from the United States into Canada, circulating from major cities out to regional centres. There were no Canadian equivalents operating nationally because it was impossible to compete with American productions financed and produced for a market ten times as large.

Examples of this economic logic at work were evident across the mass media and in all the cultural products they carried. Universal public schooling had boosted literacy rates to higher than 90 per cent of the population by the time the Great War began, creating in the process a mass market for print. Big city evening papers, such as the Toronto Star or Montreal’s La Presse, had built up huge circulations by offering a product with broad appeal. They aimed low with sensationalistic and sentimental material; they simultaneously aimed wide with a variety of offerings to satisfy many different tastes.9

Newspapers were local insofar as each served a particular city and its hinterland, printed news about that area, and reflected its interests. Nevertheless, continental cultural economics shaped their product. ‘Not only is the Canadian newspaper built on American lines,’ complained one observer, ‘it is crammed with American “boiler plate” of all kinds, American illustrations, American comic supplements.’10 He could have added columns, features and sports news. The big dailies also carried international news gleaned from American news services, which, one contemporary feared, gave Canadians ‘impressions which, day by day, trained their minds imperceptively but surely.’11

Nationalist expectations of the press concentrated on magazines; for unlike newspapers, they served a national market. Unfortunately, the magazine market was dominated by American product more directly than that of the newspaper. In the late nineteenth century, American entrepreneurs had responded to rising literacy rates with general-interest magazines that offered a varied menu of short stories, topical non-fiction, commentary, business reports, poetry and arts reviews, all packaged with illustrations, photographs, and advertising in a colourful, attractively designed format. Middlebrow mass-market magazines, such as McCall’s, the Saturday Evening Post, and the Ladies’ Home Journal, were read by tens of thousands of Canadians. English-Canadian entrepreneurs imitated them with publications such as Maclean’s, Saturday Night, and Canadian Magazine, but they found themselves competing in a domestic market already saturated with American product and dominated by American distributors. The smaller French-Canadian market, protected by language, managed to sustain its own general-interest magazines, such as Le Samedi and Revue populaire.12 But even these publications, like their English Canadian counterparts, were American in that they mimicked the American formula for mass market success, substituting Canadian for American content.

Advertising constituted a substantial portion of newspapers and magazines and underwrote most of their cost. Ephemeral publications were inexpensive to purchase because they made most of their money by delivering large audiences to advertisers. Some popular publications, such as the store catalogues, were wholly commercial in content. The field of advertising was evolving from a haphazard commercial practice into a profession with a repertoire of increasingly sophisticated psychological techniques. While each advertisement was intended only to sell a particular product, collectively they promoted consumerism and associated values such as materialism and self-indulgence.

The one form of print communication in which advertising was not intermingled with editorial content was the book.13 The Canadian book market was inundated with products from both British and American publishers. North American rights usually went to American publishers. Canadian publishers, concentrated in Toronto, survived by publishing textbooks for Canadian schools, by acting as agents for British and American publishing houses, and by publishing Canadian editions of foreign books. Patriotic publishers put out Canadian works for a Canadian audience as well, but there were easier ways to make money.

Print was also the medium through which plays and music were transmitted. New songs, for instance, were distributed primarily as sheet music. Songwriters who could afford to lose their investments had local job printers reproduce sheet music of their compositions. Sometimes a local instrument manufacturer or music academy would sponsor the printing as a sideline to its business. Canada’s music publishers did not have the marketing clout required to routinely generate hits. Only New York’s Tin Pan Alley, the music production centre that had grown up around the Broadway musical theatre, wielded that kind of influence. It advertised in mass-market magazines and major newspapers and cross-promoted popular performers and songs. The result was that hit songs could become well known across North America, heard often enough to be known by heart even by people who could not read music. The mass-marketed ditty took on the character of a folk song as it became incorporated into the popular repertoire and was sung for private as well as public entertainment.14

During the war years Canadians became accustomed to a new cultural convenience: music on demand. The piano, long a middle-class symbol of taste and refinement, had been modified by inventors in the late nineteenth century to overcome the inconvenience of not knowing how to play it. The result was the player-piano, a high-tech marvel that brought the sounds of the finest pianists into the home and satisfied ‘all that is fastidious and discriminating in taste,’ in the words of a contemporary ad. Over half of all pianos sold during the war were players.15 Enterprising telephone companies offered Sunday afternoon musical concerts over their networks, but this service did not catch on. More successful was the record player, which was replacing the gramophone. It was produced in polished wood cabinets that fit in with the finest parlour furniture. At first the ‘Victrola’ and its imitators were too expensive for any but the well-to-do, but over the war years mass production made them affordable for the middle class. (‘He suggested furs,’ confided a stylish young lady in one ad, ‘and I suggested a phonograph.’) In the process, a market for 78-rpm records developed, opening a new channel of mass communication. For those who did not have a player piano or record player, the nickleodeon offered a similar experience on a pay-per-listen basis. These commercial coin-operated music machines, located in various public venues such as restaurants, ice-cream parlours, drugstores, pool halls, and saloons, could simulate drums, tambourine, whistle, xylophone, and banjo as well as the piano.16

As diverting as it was, the new music was upstaged by the cultural phenomenon of the decade: the movie. Moving pictures had been around for twenty years, but it was during the war that the feature film was developed and gained acceptance as a mainstream popular entertainment. D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation (1915), often credited as the breakthrough production in the popularization process, was merely the first in a pack of increasingly sophisticated products. One of the big hits of the war years was Tarzan of the Apes (1918), promoted as ‘The Amazing Narrative of a She-Ape that Nursed an Orphan English Child to Astounding Manhood.’ Movie ‘palaces,’ designed to add class and glamour to the movie-going experience, already far outnumbered stage theatres. A star system developed, turning actors like Charlie Chaplin and Canada’s Mary Pickford into household names across North America. Canadian newspapers carried celebrity gossip like the Saint John Globe’s ‘News of the Stage and the Motion Picture World.’ Although most of the movies Canadians saw were American, a large minority came from Britain and France, both of which had burgeoning film industries.

The continental structure of the cultural industries affected Canadian artists as much as consumers. Canadian writers might use Canadian settings, but they worked in internationally popular genres. It was possible to stay in Canada and make a living as a writer, but only if you were an extraordinarily popular author such as Lucy Maud Montgomery or Ralph Connor. Lesser lights moved closer to the big publishers in New York or London and wrote for magazines and newspapers as well as books, always targeting ‘the great middle band in the spectrum of the reading public.’17 The same pattern was true in other areas of cultural production. Canadian theatre troupes survived by serving smaller towns instead of going head to head with the big American shows. This was the approach taken by the Marks Brothers, one of the best-known Canadian touring theatre operations of the era, and by ‘Doc’ Kelley, whose medicine show peddled patent medicines through song and dance, comedy skits, and tricks (and who merits immortality as the originator of the ‘pie-in-the-face’ routine).18 Both acts worked both sides of the border. Similarly, Canadians who wanted to become successful recording artists had to go to the United States to do so. Wartime hits written by Canadians, such as ‘Keep Your Head Down, Fritzie Boy’ and ‘K-K-K-Katy,’ were published in New York. The hit-making machinery behind the popular song was in the States. In all of these cases, it was a challenge to discern what was uniquely Canadian about a cultural product produced and consumed within the continental cultural context.

Clearly, the trends that had prompted Sandwell’s pre-war complaint were not restricted to theatre alone, and they grew stronger across the different cultural sectors throughout the war years. Canadians were increasingly plugged in to broader communications networks carrying cultural products around the continent. Styles and slang from the stage and screen were soon seen and heard on the street. In the summer, Canadians played baseball as well as cricket and lacrosse. In the winter, the well-to-do vacationed at American resort hotels from Florida to California. Traditional elements in Canada’s local, regional, and national cultures were not necessarily displaced, but they were increasingly juxtaposed with new influences that flowed faster and more profusely with each passing year. However traumatic the experience of being at war, most Canadians lived the experience from the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, immersed in a North American cultural context in which it was business as usual. Continental channels of distribution continued to feed them a steady diet of new cultural products, and they continued to consume them. There was a thickening layer of shared continental culture in the average Canadian’s life.19

When war broke out in 1914, many cultural enterprises in Canada either ceased or scaled back operations. Some artists stopped working, either because they were temporarily transfixed by events in Europe or because they felt that making art was self-indulgent when lives were on the line overseas and the future of civilization hung in the balance. In Halifax, the Canadian Bioscope Company dissolved and auctioned off its films as personnel dispersed to war service at home and abroad. Many voluntary organizations also diverted their energies from cultural activities to supporting the war effort. Music festivals in the west suspended operations for the duration of the war. Choirs and orchestras lost members. In Toronto, the symphony orchestra stumbled along, then finally disbanded in 1918.

The operations of the continental cultural industries in Canada were restricted in some ways by the outbreak of war. In the performing arts sector, there were fewer shows on tour, owing to wartime exigencies. American theatrical troupes had to contend with disrupted train schedules, unheated theatres, and special wartime taxes. In 1918 the federal government even closed theatres across the country for one day a week to save fuel. After conscription was instituted, it was not unknown for police to arrive at a theatre or dance hall, seal the exits, and march young men who lacked registration papers off to the enlistment office. A raid at the Gaiety Theatre in Toronto in 1918, for example, culled 150 of the 1,000 men in attendance. Such incidents were bad for business.

Nevertheless, the outbreak of war did not substantially alter the channels along which culture flowed or the nature of the cultural products that flowed along them. The continental cultural industries were not flexible enough to accommodate the special needs created by the belligerent status of a small fraction of their market. The themes of shows staged in Canadian theatres were indistinguishable from those put on in peacetime, offering little, other than escapism, to address the cultural needs of a nation engaged in total war.20 Those American cultural products that did deal with the war treated it as a topic of great contemporary interest rather than an all-encompassing cataclysm. It was used as a backdrop to give standard genres added topicality and poignancy. Magazines published informative articles about various aspects of the war effort alongside sentimental short stories about Daddy going off to the front or young lovers torn apart by epic events beyond their control. Advertisers used the war in a similar fashion to sell their goods. ‘In these troubled days,’ read a Columbia record player ad, ‘the comfort and solace that only good music can bring is more than ever needed.’

British cultural products offered a counterbalance. British plays with war-related themes were brought to Canada, including the London hit Under Orders, the spy drama The White Feather, and its sequel, The Black Feather. British film documentaries about the war, such as Britain Prepared (1915) and the Battle of the Somme (1916), played to packed houses across the country. The Canadian public’s interest in the war made it possible for publishers to market otherwise obscure offerings such as The Kaiser as I Know Him by Arthur N. Davis, advertised as ‘Vivid pen-pictures of the Great Enemy of Democracy in action, painted by a man who was for fifteen years the German Kaiser’s personal dentist.’21 Such imports were supplemented with a host of cheaper but no less significant items such as trinkets, postcards, Union Jacks, and portraits of the king and queen.

These products filled a void, but they could not directly address Canada’s unique experience of the war. Ultimately, Canadians were thrown back on their own resources for information and commentary. The crowd gathered around the newspaper office for the latest reports from Europe became a common sight at critical junctures in the conflict. Canadian newsreel producers sprang up to feed the public appetite for knowledge about the Canadian war effort, providing footage of Canadian troops training and staged representations of what was happening at the front. Over time they added material on the British and other Allies’ war efforts, providing a broad view of the war with a Canadian perspective and emphasis. Canadian magazines put the war on their covers and provided thorough coverage, leveraging the rare opportunity to provide a distinctive product valued by their national market.22 Although many arts organizations abandoned their cultural activities at the outbreak of war, their expertise was subsequently recruited to serve the war effort. War causes were supported by patriotic pageants and concerts at which the audience was both entertained and motivated to give more – be it in money, work, or able-bodied sons.

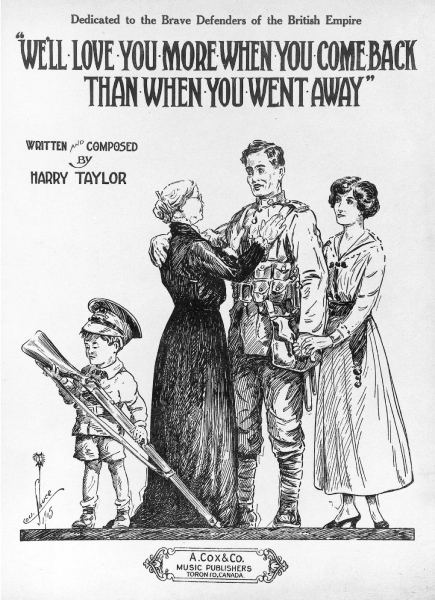

The war gave such domestic productions a comparative advantage over American cultural products. When the war began, book publishers had scrambled to meet the demand for books that could help to explain it, and they reaped commercial rewards for bringing out Canadian works such as Billy Bishop’s Winged Warfare, F.M. Bell’s First Canadians in France, and Gilbert Parker’s The War in the Crucible. A Canadian publisher estimated that over 1,000 different war-related titles were marketed in Canada during the war and that they sold, on average, about ten times as well as the average pre-war publication, some going into print runs of up to 40,000 copies.23 Most fit the mould of Ralph Connor’s The Sky Pilot in No Man’s Land, later characterized as ‘the epitome of a prevalent Anglo-Saxon Canadian view of the War – idealistic, Protestant, evangelical, and British tribal.’24 A Canadian market for war songs temporarily made domestic music publishing a more viable economic proposition. Canadians penned hundreds of tunes about the war, some of them general morale-boosters (‘What the Deuce Do We Care for Kaiser Bill’), others with specific aims such as boosting recruitment (‘We’ll Love You More When You Come Back Than When You Went Away’), and others encouraging efforts on the home front (‘He’s Doing His Bit – Are You?’).25

The advertising industry was another significant domestic producer of war-related culture. The leading experts at commercial persuasion applied their talents to raising money for wartime charities such as the Belgian Relief Fund, the Canadian Patriotic Fund, the Salvation Army and the Canadian Red Cross. They also devised campaigns to promote recruiting, Victory Bonds, and thriftiness on the home front. Some copywriters went over the top to reach their objective:

The invasion of Canada sounded like ‘bosh’ six months ago.

Today, serious men no longer laugh.

This time next year the Battle of Halifax, the Sack of St. John, the Massacre of Montreal, and the Siege of Toronto, may be writing their red histories on the breast of civilian Canada.

Certain commercial campaigns associated themselves with the cause by glamorizing military service while selling men’s products such as razor blades or wristwatches. In newspapers, magazines, posters, and billboards, advertising in the service of war cajoled, pulled at the heartstrings, and frightened readers. It sold the war to Canadians. Conversely, its usefulness in promoting the war effort helped to make advertising more socially and commercially acceptable.26

‘We’ll Love You More When You Come Back Than When You Went Away,’ by Harry Taylor, © Public Domain (National Library of Canada, Music Collection, CSM 08071)

‘Nursing Daddy’s Men,’ by Jean Munro Mulloy, © Public Domain (National Library of Canada, Music Collection, CSM05625)

The federal government’s primary concern in the cultural realm was to censor information that could be deemed useful to the enemy or could undermine the morale of Canadians.27 When it came to using culture to encourage the war effort, it was less certain of its role. It had relied heavily on the press to help to mobilize the country for war in 1914 and sponsored advertising to mobilize human and financial resources. Max Aitken (later Lord Beaverbrook), a Canadian millionaire who had moved to London and ingratiated himself into circles of privilege and power, stepped into the breach, creating the Canadian War Records Office (CWRO), ostensibly to document Canada’s war effort. Under Aitken’s guidance – and with increasing government support – the CWRO also became a publicity office. It chronicled Canada’s war exploits in books, photo-pictorials, paintings, and documentary film. Its publication Canada in Khaki exemplified how the contemporary formula for a successful mass-market magazine could be used to produce a popular, topical chronicle of Canada at war. It included sentimental poems about heroes and sacrifice, light-hearted cartoons, dramatic illustrations, and stories from the front such as ‘Canada in Hunland,’ ‘The Knight Errant from Saskatchewan,’ ‘In Memoriam of A Good Fellow,’ and ‘Christmas Day on Vimy Ridge.’ Prominent, too, were pitches for buying something special for soldiers overseas. ‘Your boy at the front may not like to ask you for them,’ ran one, ‘but cigarettes are everything for him out there.’ Profits from Canada in Khaki went to the Canadian War Memorials Fund. Its success was evidence of how government subsidy could produce a product that suited Canada’s unique circumstances.

Canadians, then, were able to improvise their own cultural products to make up for their usual supplier’s inability to meet their requirements. Had American mass culture been merely inadequate, perhaps such import substitutes would have seen Canadians happily through the war years. But in fact, American cultural products were not merely lacking – they were offensive. Canadians are known for their ability to consume American culture, but the heightened emotions of wartime and the differences in points of view of a belligerent Canada and a neutral United States fomented an unusual cultural indigestion. In movies, for example, U.S. directors had a habit of deploying shots of American patriotic symbols to stir emotions. Audiences in Canada were stirred, but not in the way that was intended. In 1914 the British Columbia censor board banned fifty reels of American film for gratuitous display of the Stars and Stripes. Only seduction and infidelity were snipped more frequently that year.28 In other cases it was U.S. boastfulness that was hard to stomach. A letter to the editor of the Toronto Star complained about ‘moving picture shows that laud American characters and hold up to ridicule Englishmen and women … Everything American is lauded to the skies, from President to the soldier. This is all right for the United States, but entirely out of place in Canada.’29 Canadian theatre-goers were similarly appalled by American stage shows that derided the British Empire and mocked its war effort.

Canadians were ready to be offended by these productions because of their disappointment with the United States for staying on the sidelines during their desperate struggle to save civilization. Most knew little of how America’s neutrality represented a balance between competing factions in its domestic politics. They interpreted Irish-American and German-American anti-British propaganda as indicative of American opinion in general. They gagged on smug pronouncements by American politicians that equated American neutrality with moral superiority, even as U.S. businesses prospered from war orders and the Allied powers grew increasingly indebted to New York bankers. The immense power of their neighbour, a seemingly natural ally, was denied to Canadians for reasons they could not comprehend. Small wonder the American flag was hissed at in Canadian theatres.30

The nature of the problem changed when the United States joined the war in April 1917, but not for the better. As U.S. cultural industries cranked up production of war-themed songs, magazine pieces, movies, and plays, American producers blithely exported domestic war propaganda with no adaptations to accommodate Canadian sensibilities. Canadians suddenly found themselves asked to believe that the United States was saving the world single-handedly. The Passing Show of 1917 at the Gaiety Theatre in Toronto, for instance, featured the American patriotic number ‘Goodbye Broadway, Hello France,’ accompanied by a display of national flags in which the Union Jack was barely visible. Such presumption and insensitivity on the part of eleventh-hour adherents to the cause bred a deep resentment in Canada. Newspaper editors printed indignant editorials. Feelings ran so high that whole audiences walked out of productions. The result was an ‘agitation,’ as one observer put it, ‘to control or modify the United States’ flag-waving tendency.’31 Sandwell’s pre-war complaint about American plays was being rendered in starker tones across a broader cultural landscape. By heightening the contrast between the two countries’ interests and values, the war emphasized the drawbacks of Canada’s dependence on popular culture that largely emanated from outside its borders.

The problem was all the more evident because of Canadians’ war-induced sense of accomplishment, identity, and independent destiny. When Canada turned fifty in 1917, the war was widely regarded as the maturing nation’s rite of passage to full independence and status in international affairs. Canadians took pride in having fought hard for a righteous cause in Europe. Vindicated by victory, they revelled in a sense of accomplishment and maturity. The ‘old bitch gone in the teeth,’ Ezra Pound’s famous characterization of the civilization capable of the carnage of the Great War, did not apply here. Canada was a frisky pup with a sharp bite.

The war and its aftermath also demonstrated the impracticality of pre-war schemes for imperial federation and nudged Canada towards greater constitutional autonomy. While still valuing their British cultural heritage, Anglo-Canadians gained a keener consciousness of the ways in which they were not British, and they would increasingly support autonomist foreign policies and imperial devolution. This trend only made Canada’s dependence on continental mass culture all the more problematic. If Canada became less British, mass culture and the American values it bore would become relatively more influential, increasing the danger of what one contemporary called ‘spiritual bondage,’ a condition he defined as ‘the subjection of the Canadian nation’s mind and soul to the mind and soul of the United States.’32

The offence given by American cultural products reinforced cultural nationalists’ determination to foster a Canadian culture that would offset the influence of continental culture in the marketplace. The feasibility of this project varied widely from one cultural sector to the next. The cultural industries in Canada during the war years can be categorized roughly into two types. There were some that had Canadian producers serving their domestic market. In others, Canadian producers were scattered, small, and lacking in collective consciousness or power. Often the political clout in these sectors lay with distributors or retailers whose interest lay in a steady supply of American product.33 The significance of this distinction was evident in the publishing, theatre, and movie industries, three high-profile cultural sectors targeted by nationalist initiatives in the wake of the war. In the first, nationalist and business interests combined with some success, while in the latter two they did not.

It was no coincidence that Canadian producers were entrenched most firmly in the older print media. Newspapers were a special case in which a local product would exist under most circumstances. The magazine and book publishing industries in Canada, for their part, pre-dated the rise of big business on a continental scale in the late nineteenth century. Despite the dominance of external producers, there were Canadian producers serving a Canadian market in this sector. Moreover, literature, the high culture in this medium, was considered a fundamental aid to nationalism because it both proved the existence of and disseminated national identity. Thus, there was a shared interest between nationalists and Canadian cultural industries in reserving some space in the domestic market for Canadian publishers.

In the past these factors had occasionally moved the government to set aside its laissez-faire principles and intervene in the marketplace. During the 1870s and 1880s the federal government had done its best to avoid enforcing international copyright conventions, thereby subsidizing the Canadian publishing industry by allowing it to profit from publishing cheap editions of foreign works.34 After it was forced to toe the line in the 1890s, the government toyed with protectionist measures on the rationale that Canadian publishers were frequently frozen out of their own market by the British and American practice of granting North American rights to American publishers.35 It also subsidized Canadian newspapers and magazines with low second-class mail rates, a policy designed, as Sir Wilfrid Laurier put it, ‘to foster a national consciousness.’36 In 1917 the federal government played a role in breaking Canadian newspapers’ dependence on American news services, providing a $50,000 annual subsidy to support Canadian Press.37 The magazine industry would campaign successfully in the post-war period for a protective tariff, demonstrating once again the sector’s ability to move the government to defend its interests.

In cultural sectors where there was no established Canadian production industry, fostering Canadian content was much more of a challenge. Nevertheless, efforts were made. In 1919 Canadian investors launched the Trans-Canada Theatre Society to secure ‘complete control of a professional theatre route entirely in Canada.’ Their business plan was to buy up theatres to create a chain across the country that would show touring versions of British plays (which presumably would offset the influence of U.S. plays, creating a balanced ‘Canadian’ theatre scene). Things did not work out as planned. Trans-Canada faced competition not only from American stage productions, but also from movies, which grew tremendously in popularity in these years. It went bankrupt in 1924.38

Nationalist impulses in the movie business followed a somewhat different path to the same dead end. A number of film producers were inspired by the post-war climate of cultural nationalism – and the possibilities it created for raising funds – to make movies in Canada on subjects both Canadian and non-Canadian. The most successful was Ernest Shipman, a Canadian with Hollywood experience who produced a clutch of films over half a decade following the war. Shipman’s modus operandi was to raise money in the city closest to the locale in which he was filming. ‘A New Industry in Canada,’ proclaimed his Calgary newspaper ad in March 1919. He offered locals a piece of the action for Back to God’s Country, with the assurance that his wife, Nell, ‘the greatest outdoor girl on the screen today,’ would be the star.39

The movie business was still in a state of flux, and it was possible for independent producers like Shipman to find distribution in North America and return profits to investors. But in the early 1920s Hollywood studios began buying up film distributors and theatres in order to guarantee a market for their products. Vertical integration shut Canadian productions out of domestic and international markets, blocking the development of a Canadian feature film industry before it got properly started.40 Other western nations responded to the flood of cheap and attractive film imports from Hollywood in the post-war period with protectionist policies aimed at reserving a slice of their own markets for domestically produced films. In Canada’s case, however, there was no established domestic production industry for the government to protect. Exhibitors were the dominant economic interest in the sector, and they wanted a steady supply of cheap and popular American product. The general public may have been interested in seeing Canadian movies, but there was no economic ‘interest’ backing a Canadian movie production industry.

The cultural nationalist impulse produced more tangible results in the voluntary sector. The organizational impulse evident in the sector in the pre-war years was just as strong in the post-war period and, energized by war-induced nationalism, spurred the development of a nation-wide web of cultural nationalist groups in the 1920s. There were new and revived professional associations in the arts, music festivals, academic organizations, and service clubs, all bound together with newsletters, journals, conferences, and national executives.41 ‘The war itself had broken down the barriers of mountain, lake and sea,’ Brooke Claxton would recall in his memoir. ‘Right across Canada were associations and individuals concerned about the same kind of things and working to the same goals.’42

This expanding network extended beyond voluntary organizations in the arts and letters to universities, cultural institutions, and the few cultural industries where Canada had domestic producers. Its activities in the post-war period reflected its power base. The painters of the Group of Seven, Canadian nationalism’s poster boys of the post-war era, were nurtured by the Canadian advertising graphics industry, then promoted by the National Gallery and the Canadian press. Maclean’s magazine pledged to print only Canadian non-fiction and a minimal amount of non-Canadian fiction. The Canadian Magazine went farther, promising 100 per cent Canadian content. A new firm in Ottawa, Graphic Press, dedicated itself to only Canadian works – an ideal it pursued for the better part of a decade before collapsing into bankruptcy. Other Canadian publishers devoted themselves to fostering a native literature in addition to publishing the foreign trade books and textbooks that still brought in most of their money. A flurry of anthologies, literary histories, and other published proof of national identity followed.

While such projects gave cultural nationalists a sense of accomplishment, they did little to offset the influence of continental mass culture. Despite American wartime provocations, Canadians had negligible success challenging continental mass culture on its own turf in the immediate post-war period. One is tempted to conclude that if nothing happened under these circumstances, nothing ever would happen. More to the point is to ask why this dog didn’t bark – or, to put it more accurately, why it merely whimpered.

One possible explanation is that Canadian-American cultural relations simply returned to the status quo ante bellum: once the war ended, the gap between American and Canadian sensibilities closed, and the problem faded into a distant memory. But this was not, in fact, the case. In the 1920s America kept churning out ‘how we won the war’ productions, and Canadians continued to find them offensive. Sensitivities were still raw enough that Canadian advertising executives advised U.S. companies to carefully review their advertisements to ensure that they did not provoke Canadian customers. Late in the decade, an ambitious Canadian film production, Carry On Sergeant, was produced in large part as a Canadian rejoinder to American war movies.

A more significant factor was Canada’s tendency to think of itself as British – if no longer as a British colony, at least as a British North American nation. This perception fostered the practice of depending on British books, music, theatre, and film to offset American products instead of producing Canadian equivalents. Canadians maintained an unwarranted faith in the mother country’s continuing economic power and international influence, and they assumed that British cultural products would win in the marketplace, owing to their inherent superiority. Continued reliance on British culture as an antidote to American influence obscured the need for made-in-Canada solutions to Canada’s unique cultural predicament.

This anglophilic reflex was reinforced by the tendency of the upper classes to associate British culture with high culture and American culture with low culture. Their model for a national culture was British culture or, at least, what they thought of as British culture: the canon of literature, fine art, serious theatre, and classical music. It was a model moulded to offset their negative impressions of mass culture. The class dimensions of this concept, high versus low, were conflated with nationalism, creating a parallel dichotomy of Canadian versus American. This bias was accommodated by the fact that the locus of Canadian cultural nationalism lay in the voluntary sector. Even if leading cultural nationalists had been interested in competing with American cultural producers in the marketplace of mass culture, they lacked the ability to do so. They were not business people with market knowledge, economic power, and political influence. The technologies that facilitated media transmission of culture were foreign to them. Indeed, as we have seen, the print media were the only Canadian cultural producers that had the economic significance and political clout – with the support of nationalists – to move the government to act against American cultural imports.

The Canadian cultural nationalism forged by the wartime experience would be influential in Canadian cultural policy for the next half century. A generation of cultural nationalists for whom the war was a formative experience would launch the Radio League, create the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, support the National Film Board, champion the Massey Commission, and breathe life into the Canada Council.43 All of these key components of the Canadian cultural establishment would be shaped by the voluntary sector’s brand of cultural nationalism. Not until the 1960s would a new generation rethink its predecessor’s assumptions and try again to Canadianize the more popular forms of culture purveyed in the continental cultural marketplace. By that time continental mass culture had had another half-century to entrench itself in the northern half of North America. As Canadian compromises go, this wasn’t such a bad deal. Canadians enjoyed unfettered access to the mass culture that defined them as North Americans while developing parallel means of distinguishing themselves as above all that. Cultural nationalism flowed along the paths of least resistance, complementing rather than confronting continental mass culture.

1 Bernard K. Sandwell, ‘Our Adjunct Theatre,’ Addresses Delivered before the Canadian Club of Montreal, 1913–1914 (Montreal, 1914), 97. Sandwell noted that theatre, once suspect as a lowbrow, immoral diversion, was on its way upmarket and was increasingly being accepted in proper society. His assertion about Canada’s not having been invaded, of course, excluded the War of 1812, various rebel incursions, and the Fenians. For an earlier, more wide-ranging analysis of the various ways in which American influences were affecting Canada, see Samuel E. Moffatt, The Americanization of Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1972 [1906]).

2 The main exception was, of course, francophone Quebec, where anglophobia prevailed over anglophilia, and a relatively compact population with a distinctive culture and language created a viable regional market for locally produced cultural goods and impeded American cultural imports. Some of what follows applies to Quebec, but the province was, as always, a special case.

3 Beckles Willson, ‘Canada’s Undeveloped Literary Resources,’ Addresses Delivered before the Canadian Club of Montreal, 1913–1914, 192.

4 Elaine Keillor, Vignettes on Music in Canada (Ottawa: Canadian Musical Heritage Society, 2002), 217.

5 Calgary Eye Opener, 2 December, 1916.

6 Bruce Hutchinson, The Far Side of the Street (Toronto: Macmillan, 1976), 41–2, 46–7. See Daphne Read, ed., The Great War and Canadian Society: An Oral History (Toronto: New Hogtown Press, 1978), for a variety of individuals’ memories of the war, some of which deal with cultural activities.

7 The Methodists’ rules were relaxed somewhat by doctrinal reforms in 1914. See Ann Saddlemyer and Richard Plant, eds, Early Stages: Theatre in Ontario, 1800–1914 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1990), 48, 346. For a discussion of the degree to which the church effectively exercised moral leadership in small town Ontario of the late nineteenth century, see Lynne Marks, Revivals and Roller Rinks: Religion, Leisure, and Identity in Small-Town Ontario (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1996), 210.

8 Maria Tippett, Making Culture: English-Canadian Institutions and the Arts Before the Massey Commission (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1990), 55–6. Organizational networks had been built up in previous decades through postal and telegraph communication and rail transportation. During the war, two new technologies, the telephone and the automobile, accelerated this trend. Both were overcoming range limitations in these years. Transcontinental long-distance telephone service had just become available but was not yet routine, while the road system required to make the car a viable alternative for long-distance travel would come in the years following the war.

9 Paul Rutherford, The Making of the Canadian Media (Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1978), 49.

10 Archibald McMechan, ‘Canada as a Vassal State,’ Canadian Historical Review 1, 4 (December 1920), 349.

11 J. Castell Hopkins, ed., Canadian Annual Review of Public Affairs, 1918 (Toronto: Annual Review. Co., 1914–18), 123.

12 Rutherford, Making of the Canadian Media, 46, 49.

13 It should be noted, however, that some books had ads, particularly for other books, inside their covers.

14 Keillor, Vignettes, 161.

15 So popular was the player piano that some Canadians could not leave home without it. During the war years, Robert J. Flaherty, the Arctic explorer and filmmaker who made the famed documentary, Nanook of the North, took his player piano with him on one of his expeditions. On departing the Belcher Islands, Flaherty gave his ‘singing box,’ as the Inuit called it, to a Native friend who subsequently suffered a common piano-owner’s dilemma when he found it would not fit into his igloo. Enterprising in his returns policy, he transported it over 280 miles south to Fort George to give it back to its original owner. Wayne Kelly, Downright Upright: A History of the Canadian Piano Industry (Toronto: Natural Heritage / Natural History Inc., 1991), 38.

16 Keillor, Vignettes, 142–5.

17 Gordon Roper, Rupert Schieder, and S. Ross Beharriell, ‘The Kinds of Fiction, 1880–1920,’ in Carl Klinck, ed., The Literary History of Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1965), 312.

18 Ann Saddlemyer and Richard Plant, eds, Later Stages: Essays in Ontario Theatre from the First World War to the 1970s (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997), 128.

19 How were Canadian interests served by this situation? The answers vary by cultural sector and according to whether the interest in question was that of the consumer, producer, distributor, or cultural nationalist. The mass cultural milieu exposed Canadian consumers to a broader world. It was possible to appreciate Latin dance or southern Black music without ever leaving the country, even if one was fuzzy on their provenance. Canadians might end up with a watered-down or caricatured version of these styles, but they were exposed to something different from what they were likely to experience within their local cultural milieu.

There was also a place for Canadian identity in international mass culture. Enough was published on the various regions of Canada to give Canadians and foreigners a sense of the diversity of their country and the character of its various parts. However, most people entertained vague impressions rather than a detailed knowledge based on extensive reading. The stereotype of a timeless, picturesque, pre-modern Quebec, for example, prevailed despite the growth of cities and industry in the province. Gilbert Parker’s romance The Money Maker (1915), set in a fictitious Quebec parish, took this approach because that was its author’s understanding of this part of his native country. ‘I think the French Canadian one of the most individual, original, and distinctive beings in the modern world,’ wrote Parker. ‘He has kept his place, with his own customs, his own Gallic views of life, and his religious habits, with an assiduity and firmness’; Roper, Schieder, and Beharriell, ‘The Kinds of Fiction, 1880–1920,’ 290. The other dominant image of Canada was the great northwest, otherwise known as ‘God’s Country,’ a snowbound realm on the margin of civilization peopled by noble savages, mad trappers, gold-crazed prospectors, strapping lumberjacks, and dauntless Mounties. Caricatures like these projected an image of Canada to foreign lands that was as skewed and partial as those Canadians had from their imported impressions of other parts of the world.

Allan Smith has written extensively on the North American dimension of Canadian identity in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. See Smith, Canada – An American Nation? (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1994), particularly the essays ‘The Continental Dimension in the Evolution of the English-Canadian Mind’ (originally published in the International Journal 31, 3 [1976], 442–69), and ‘Samuel Moffatt and the Americanization of Canada’ (first published as the Introduction to a reissue of Moffat, Americanization of Canada, vii–xxxi.

20 The Toronto Evening Telegram of Saturday 9 December, 1916, for instance, listed H.M.S. Pinafore, The Merry Wives of Windsor, Charley’s Aunt, Irving Berlin’s comedy Watch Your Step, and a ‘thrilling story,’ Yellow Pawn, at a variety of theatres – the Royal Alexandra, the Grand Opera House, Shea’s, Loew’s Yonge Street, and the Regent.

21 Canada in Khaki. A tribute to the officers and men now serving in the overseas military forces of Canada (Toronto: published for the Canadian War Records Office by Musson, n.d.), 2: 189. Davis’s book was published in the United States and Britain by Harper & Brothers, a firm with offices in New York and London, but in an arrangement typical of the publishing industry in the English-language world, it was offered in Canada by the Musson Book Company of Toronto.

22 In the process, they tended to vacillate between courageous optimism and bleak despair, if only to exploit all available modes of sensationalism. Maclean’s, for example, ran a cover illustration of a Canadian soldier strangling a German in November 1918, with the caption, ‘Buy Victory Bonds and Strengthen His Grip.’ Just a few months earlier it had featured an article entitled ‘Why We Are Losing the War.’

23 Hugh Eayrs, president of Macmillan, in Canadian Bookman, 1919, as quoted in George L. Parker, ‘A History of a Canadian Publishing House: A Study of the Relation between Publishing and the Profession of Writing, 1890–1940,’ PhD thesis, University of Toronto, 1969, 59.

24 Roper, Schieder, and Beharriell, ‘The Kinds of Fiction, 1880–1920,’ 311.

25 See ‘Canadian Sheet Music of the First World War,’ Music on the Home Front: Sheet Music from Canada’s Past, on the Web site of the National Library of Canada: http://www.nlc-bnc.ca/sheetmusic/m5-170-e.html.

26 H.E. Stephenson and C. McNaught, The Story of Advertising in Canada (Toronto: Ryerson Press, 1940), 171, 185.

27 Jeffrey Keshen, Propaganda and Censorship during Canada’s Great War (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 1996), 107.

28 Peter Morris, Embattled Shadows: A History of Canadian Cinema, 1895–1939 (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1978), 55.

29 Toronto Daily Star, 25 November 1916, as cited in Saddlemyer and Plant, Later Stages, 105n20.

30 Hugh L. Keenleyside, Canada and the United States (New York: Knopf, 1929), 365–8.

31 Hopkins, Canadian Annual Review, 1918, 123.

32 McMechan, Canada as a Vassal State, 347.

33 Ted Magder explains the lack of a feature film production industry in post-war Canada in these terms, and same explanation seems to apply to other cultural sectors with the same industry structure. See Magder, Canada’s Hollywood: The Canadian State and Feature Films (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993), 25. This categorization is somewhat speculative and may require revision once more research on these cultural sectors during this period becomes available. Moreover, it is a generalization that has to be qualified with regard to Canadian publishers, because they could (and did) easily lapse into the role of mere ‘distributors’ for British or American books. Many, however, entertained greater ambitions, using profits from publishing foreign works to invest in Canadian works.

34 George L. Parker, The Beginnings of the Book Trade in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1985), 167–93.

35 Parker, ‘History of a Canadian Publishing House,’ 25.

36 Fraser Sutherland, The Monthly Epic: A History of Canadian Magazines, 1789–1989 (Toronto: Fitzhenry & Whiteside, 1989), 27.

37 Rutherford, Making of the Canadian Media, 55.

38 John Herd Thompson with Allan Seager, Canada: 1922–1939: Decades of Discord (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1985), 171. Just prior to the war, the British Canadian Theatrical Organization Society had been formed to bring in English touring companies to counteract U.S. influence. See Patrick B. O’Neill, ‘The British Canadian Theatrical Organization Society and The Trans-Canada Theatre Society,’ Journal of Canadian Studies 15, 1 (Spring 1980).

39 Calgary Eye Opener, 15 March 1919.

40 The federal and some provincial governments established film bureaus to produce documentaries, but the feature film business remained an American free-market monopoly.

41 Mary Vipond, ‘The Nationalist Network: English Canada’s Intellectuals and Artists in the 1920s,’ Canadian Review of Studies in Nationalism 7, 1 (1980), 32–52.

42 Claxton as quoted in Sandra Gwyn, Tapestry of War: A Private View of Canadians in the Great War (Toronto: HarperCollins, 1992), 488.

43 In the case of radio, the government was spurred to action, despite the existence of a Canadian distribution industry plugged into American supply lines. However, in this case the nationalist cause enjoyed the support of Canadian print industries that feared competition from broadcasting.