The old, antiquated phoenix is only waiting for his funeral pile, and will not be long finding it, for the time is at hand, and we shall live to see great things. 1

—Fanny to Klingemann, April 14, 1828

Early on June 30, 1825, Zelter and the young builder C. T. Ottmer, escorted by bricklayers, carpenters, and the Singakademie management, assembled off Unter den Linden to lay the cornerstone of a new musical temple. Wielding a hammer, Zelter consecrated the first stone in the name of old Fasch. 2 Designed by K. F. Schinkel, architect of Berlin neoclassicism, the new Singakademie became a living musical museum, its construction linked to Zelter, master mason and guardian of the Prussian musical heritage: on July 11 he secreted official documents inside the cornerstone and on December 11, his birthday, observed the capping-off ceremony. 3 Work continued for about a year before Zelter held his first rehearsal in the new building; the public dedication followed on April 8, 1827, with a performance, appropriately, of Fasch’s monumental sixteen-voice Mass. Felix’s response was to compose his festive Te Deum for the new hall, which could accommodate 250 singers and an orchestra of 50, arranged in an amphitheatric arch within an oblong hall 84 by 42 feet. 4 Zelter no doubt approved of the historicist composition, with its baroque, polychoral formations and ornate counterpoint, all furthering his agendum of glorifying past musical monuments. But by 1827, as Abraham realized, Felix had matured to the point that “his genius was now self-existent, and that further teaching would only fetter him.” 5

The Octet and Midsummer Night’s Dream Overture had indeed unlocked for Felix musical romanticism, worlds removed from the eighteenth century finery of the Singakademie. The overture impressed Zelter variously as a meteor, airy phenomenon, and colliding mosquitoes descending to the earth. 6 But Felix’s testing of the power of instrumental music to express ideas external to music—an experiment encouraged by Zelter’s nemesis, A. B. Marx—may have strained the limits of the elder musician’s aesthetics. By early 1827 Felix’s formal lessons with Zelter were discontinued, to the irritation of the aging musician, who, as Devrient relates, maintained the adolescent had “not yet outgrown his leadership.” 7

Furthering Felix’s new artistic independence were the growing performances of his music outside Berlin. Early in February, the Symphony in C minor, Op. 11, received praise in Leipzig for its youthful energy. 8 The same month, Felix departed for Stettin (Szczecin) in the Prussian province of Pomerania, where, on February 20, he performed the double Piano Concerto in A ♭ major with Loewe, who premiered the Midsummer Night’s Dream Overture and directed Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony and Weber’s Konzertstück (Felix took up a violin part in the symphony and was the soloist in the Konzertstück , performed—unusual for the time—from memory). The overture did not fail to impress, despite its juxtaposition with Beethoven’s colossal score. A reviewer likened the ribald intrusions of the bassoon and English bass horn to a pair of ass’s ears in genteel company, and an artistic lady compared the fluttering, divided strings to swarms of mosquitoes. 9 During his visit, Felix also appeared in private soirées, where he dispatched from memory sonatas of Weber and Hummel, and Beethoven’s Hammerklavier , the culminating, “almost unplayable” fugue of which Felix “conquered” with a “roaring tempo.”

Having returned to Berlin, Felix corrected proofs for the piano-vocal score of Weber’s Oberon , brought out by Schlesinger in March. 10 Over-shadowing this editorial work were preparations for the premiere of Die Hochzeit des Camacho , finally scheduled for April at the Schauspielhaus. On finishing his opera in August 1825, Felix had submitted it to Count C. F. von Brühl, Intendant of the royal theater, who passed it on to Kapell-meister Spontini, holder of a near veto power. Playing the uncooperative bureaucrat, Spontini procrastinated before summoning Felix in July 1826. Ironically enough, Spontini resided in the same building on Markgrafenstrasse where Felix’s family had lived years before. But Spontini had transformed his quarters into a narcissistic gallery, with busts, medals, and sonnets in his praise, and a dais from which he received visitors. 11 Here Spontini deprecated Felix’s score and commented, while pointing through a window to the dome of the French Church, “Mon ami, il vous faut des idées grandes, grandes comme cette coupole ” (“My friend, you must have grand ideas, grand like that dome”). 12 Spontini demanded enough revisions to provoke Abraham into an angry exchange, forcing Brühl to intervene early in 1827. And there were other impediments. No sooner had stage rehearsals begun, early in April, 13 before Heinrich Blume (Don Quixote) contracted jaundice, so that the premiere was delayed until April 29.

Despite late twentieth-century attempts to revive the opera, 14 Camacho has always occupied an uncomfortable position in Felix’s oeuvre. The librettist, variously identified as the Regisseur Baron Karl von Lichtenstein, Karl Klingemann, or the elder August Klingemann, remains unknown, although Rudolf Elvers has demonstrated that the Hanover writer Friedrich Voigts actively participated in at least the first act and probably the second as well. 15 The subject of the opera derives from Cervantes’ Don Quixote , the source for over one hundred operas. But few composers selected the episode of Camacho’s wedding from the second part of the novel (ch. 20–21), and of these only J. B. Schenk’s Der Dorfbarbier (The Village Barber , 1796) enjoyed some success.

Felix’s attraction to Don Quixote reflected a German fascination with Cervantes. In 1799 Ludwig Tieck had translated the novel, and Felix would have also been familiar with the criticism of his uncle, Friedrich Schlegel, who viewed Don Quixote as “the model of the novel, fantastic, poetic, humorous.” 16 No less enthusiastic was Friedrich’s brother August Wilhelm, among the first to defend Cervantes’s technique of inserting digressing stories (such as Camacho’s wedding) within the novel and to recognize the significance of its second part, in which the knight achieves an increasing independence from the chivalrous persona of the first part.

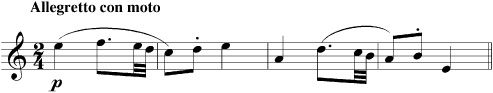

In transforming Cervantes’s tale (in which Carrasco attempts to marry off his daughter Quiteria, in love with the poor Basilio, to the wealthy landowner Camacho) into a romantic Singspiel, Felix had to contend with certain issues. For Devrient the story was suitable only for “a comic dénouement ,” and the librettist’s inability to develop dramatic contexts—Felix himself complained of the overused strophic settings that interrupted the dramatic flow 17 —was ultimately “paralyzing.” 18 Unlike the Midsummer Night’s Dream Overture, in which he could draw upon an entire play for a twelve-minute overture, he now had to produce several hours of music for a single episode from Cervantes’s epic. There is some evidence that, as in the concert overture, Felix considered deploying a network of motives throughout the opera; thus, as the Scotsman John Thomson observed, “each character has a language of its own, so that one can never mistake the strains of Sancho for those of his master….” 19 The Overture commences with a brass fanfare indelibly associated with the Don ( ex. 6.1 ), whose first entrance occurs with the fanfare near the end of Act I, when, imagining Quiteria to be his idealized Dulcinea del Toboso, he springs to her defense. Progressing from tonic to dominant, the motive is ultimately extended to form a complete cadence in the closing bars of the opera, so that the fanfare functions like a motto, framing the opera and renewing itself in the middle. The technique is thus not unlike the motto in the Midsummer Night’s Dream Overture, though now applied across a much larger temporal span. But the knight’s motto proved a miscalculation. Felix covered the Don with too much musical armor; if the nebulous wind chords of the concert overture effortlessly conjure up Oberon’s elves, the ponderous fanfares of Don Quixote fail to convey an “ironical sense of knight-errantry.” 20

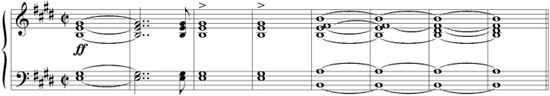

Ex. 6.1 : Mendelssohn, Die Hochzeit des Camacho (1827), Overture

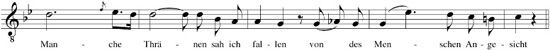

Curiously, in the Overture Felix avoided delineating the other principals with their own motives. Instead, for the second theme of the exposition, he utilized material from the ballet of Act 2, where the opposing forces of Cupid and Wealth clash; a tender phrase from the theme reappears just before the ballet, sung by a chorus to the text, “Love is all conquering, love triumphs in every contest” ( ex. 6.2 ). The ballet itself adheres closely to the novel. Cervantes describes a masquelike entertainment in which rows of nymphs, led by Cupid and Interest, endeavor to free a maiden imprisoned in a wooden castle. Accompanying Cupid’s forces are a flute and tambourine, employed by Felix in an exotic bolero ( ex. 6.3a ). On the other hand, Interest dances a fandango, in which Felix replaces the seductive tambourine with a shimmering triangle to suggest Camacho’s wealth ( ex. 6.3b ). The Spanish dances inject local color into Felix’s score and recall the precedent of Mozart and Weber, who incorporated a fandango and bolero in two operas set in Spain, The Marriage of Figaro and Preciosa (the latter based on a Cervantes novella ).

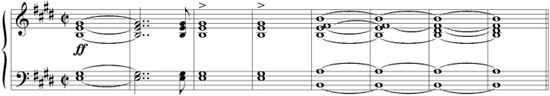

Ex. 6.2 : Mendelssohn, Die Hochzeit des Camacho (1827), Act II

Ex. 6.3a: Mendelssohn, Die Hochzeit des Camacho (1827), Act II, Bolero

Ex. 6.3b: Mendelssohn, Die Hochzeit des Camacho (1827), Act II, Fandango

Elsewhere, the Germanic quality of Felix’s music protrudes, especially in two numbers strongly reminiscent of Weber. In the finale of Act 1 (No. 11) Vivaldo sings off-stage to the jaunty strains of a Waldhorn , and in Act 2 (No. 16), a bridesmaids’ chorus replicates the key and style of the popular chorus from Der Freischütz . These concessions to Berlin taste could not conceal the libretto’s threadbare quality, and for Devrient, who played Carrasco, the score still represented the “musical thought” of Felix’s earlier Singspiele.

An audience filled with family friends greeted the premiere. But the chorus was unsteady, and an exasperated Felix fled before the conclusion of the opera, leaving Devrient to apologize for his friend’s absence. The second performance, scheduled for May 1, was abruptly canceled. 21 At once critics seized on the libretto’s weaknesses. Ludwig Rellstab reported the encouraging, if not deafening, applause, 22 and also the excessive length of the libretto. According to a Leipzig correspondent, the performance precipitated “stormy applause” but opposition to the partisan calls for the composer to appear. 23 Felix was guilty of “overstriving” for effect. The noisy overture was too bloated for the “romantic, idyllic” material; and the composer, known for serious instrumental compositions, was out of his element, so that Cervantes’s tale did not spring fully to life. Meanwhile, a French correspondent hinted that the production was owing to Abraham’s wealth and dismissed the libretto as perhaps the most “maladroit” opera book yet derived from Cervantes. 24 Most damning, the score was “completely Germanic”; ignoring the ballet, the reviewer found no evidence of couleur locale .

These critiques paled against invidious comments in a minor gossip column, the Berliner Schnellpost , edited by M. G. Saphir: “At the Wedding of Camacho a Sunday public [April 29 fell on a Sunday] danced a contra-dance with a Sabbath public. After both sides had been stood up in vain, they fainted.” 25 Felix was hurt when he learned the author of these anti-Semitic sentiments was a “highly gifted musical student, … who had witnessed and shared the excitement of the family during the preparation of the opera, and who knew the score well.” 26 Though Felix later referred to Camacho as “my old sin” 27 —even Zelter had acknowledged its libretto contained no gold 28 —Felix drew from the episode a lifelong distrust of journalism: the most lavish praise from demanding critics could not offset the most contemptible abuse of the tawdriest literary rags. He also developed a phobia of committing to another libretto and henceforth examined numerous subjects only scrupulously to reject them, one by one. (Thus, during the summer of 1828, he declined Eduard Devrient’s libretto on the legend of Hans Heiling, owing to its similarities to Der Freischütz , 29 and even before Camacho was staged, Felix was unable in 1826 to come to terms with Helmina von Chézy, who had proffered a libretto on a romantic Persian subject. 30 ) The brilliant composer of boyish Singspiele for his parent’s residence failed at age eighteen in the public opera house. Curiously enough, in 1828 the Berlin firm of Friedrich Laue issued a piano-vocal score of the opera in heavily revised form, even though Felix did little to encourage the work’s revival. 31 Almost certainly Abraham underwrote this publication, since it was clearly unviable commercially; indeed, a reviewer commented that its price was sehr hoch . 32

While readying Camacho , Felix passed the entrance examination to the University of Berlin. At Easter (April 15) Heyse ended his tutorship of Felix in order to pursue the Habilitation at the university; as a replacement, Abraham hired the student J. G. Droysen (1808–1884), who had arrived in 1826 to study with the philologist August Böckh. 33 The son of a Pomeranian minister, Droysen possessed “knowledge far above his age” 34 and became a lifelong friend of the Mendelssohns. Felix and Rebecka studied Greek with him “as far as Aeschylus,” 35 Droysen’s specialty. On May 8, 1827, Felix matriculated at the university, to obtain the Bildung “so often lacking in musicians.” 36 Founded in 1807, the institution attracted within twenty years a distinguished faculty that boasted Wilhelm von Humboldt as the first rector, and his brother, the natural scientist Alexander von Humboldt, the geographer Ritter, theologian Schleiermacher, philosophers Fichte and Hegel, astronomer J. F. Encke, Indo-Europeanist Franz Bopp, historian Ranke, jurists Savigny and Eduard Gans, and Böckh. Among its students were the future “Young Hegelian” Ludwig Feuerbach (1824), and Heinrich Heine (1821–1822), who, like Felix, spent four semesters at the institution. Felix’s lecture notes in history and geography, 37 and matriculation records confirm he was a most diligent student, though evidently between classes he preferred to improvise on the Midsummer Night’s Dream Overture on the piano of a “beautiful lady.” 38

Felix attended the lectures of the historian Leopold Ranke and zoologist M. H. K. Lichtenstein but was especially drawn to the offerings of the geographer Carl Ritter, 39 who in 1822 had begun to publish his magnum opus , the twenty-one-volume Erdkunde , destined to fill by 1859 some twenty thousand pages. Its full title (Geography in Relation to Nature and Human History, or General Comparative Geography as a Firm Foundation for the Study of and Instruction in Physical and Historical Disciplines ) reveals its daunting scope. For Ritter, the globe had “a life of its own—the winds, waters, and landmasses acting upon one another like animated organs, every region having its own function to perform, thus promoting the well-being of all the rest.” 40 It was probably this aspect of Ritter’s scholarship, stressing the “organic” connectedness of the natural world, which particularly impressed Felix, as he pondered “organic” thematic relations in his own instrumental compositions.

During the spring of 1827 the death of a friend, August Hanstein, shook Felix. He sought refuge in counterpoint, and by the invalid’s bedside conceived an unusual piano fugue in E minor, completed on June 16 along with a second fugue. 41 Later Felix coupled the two with preludes and published them as the Prelude and Fugue, Op. 35 No. 1 (1837) and a contribution to the album Notre temps (1842). These dissonant compositions, featuring subjects rent by angular sevenths and tritones ( ex. 6.4a, b ), were meant to depict his friend’s illness; in the “accelerando” fugue of Op. 35 No. 1, the increasingly agitated counterpoint symbolized for Schubring the “progress of the disease as it gradually destroyed the sufferer.” Climaxing with stentorian octaves, the fugue culminates with a “chorale of release,” 42 a freely composed hymn in E major in which soothing conjunct motion smoothes out the jarring fugal contours. A quiet epilogue, rather like a devotional organ postlude, brings the composition to a hushed close. Schubring took this “specifically church coloring” as evidence of Felix’s fundamental spirituality and noted that his friend habitually began his autographs by inscribing an abbreviated prayer (Lea identified two recurring throughout Felix’s manuscripts: H.D.m ., for Hilf Du mir , “Help me, [O Lord],” possibly from Jeremiah 17:14, and L.e.g.G , for Laß es gelingen, Gott , “Let it succeed, O Lord” 43 ). But this religiosity later exposed Felix to charges of excessive sentimentality; for Charles Rosen, who has regarded Op. 35 No. 1 as “unequivocally a masterpiece,” Felix was essentially the “inventor of religious kitsch in music,” substituting the “emotional shell of religion” for religion itself, 44 and spawning a strain of musical piety that ran through the nineteenth century.

Ex. 6.4a: Mendelssohn, Fugue in E minor, Op. 35 No. 1 (1827)

Contemporaneous with the E-minor fugues is the Piano Sonata in B ♭ major, finished in May 1827, perhaps in response to Beethoven’s death on March 26. When the sonata appeared posthumously in 1868, it received the opus number 106, linking it to Beethoven’s magisterial Op. 106, the Hammerklavier Sonata, with which Felix’s sonata shares its key and several features. The two begin with similar ascending figures and explore the submediant G major in their first movements. Felix’s second movement is a scherzo in B ♭ minor, not unlike the middle of Beethoven’s scherzo, though here again the young composer invokes the elfin imagery of the Octet and eventually disperses his scherzo in another evaporating puff. Considerably less Beethovenian is the Andante in E major, which impresses as an improvisation on the concluding pages of the Midsummer Night’s Dream Overture. But this nocturne-like trance concludes with a dramatic gesture: transitional horn calls that introduce the sprightly, widely spaced Weberesque subject of the finale. Near its midpoint the scherzo suddenly returns, injecting minor-hued shades into an otherwise carefree finale. Unlike the recall of the scherzo in the Octet, though, the technique here flags, and when at the end Felix sums up with a cadential figure, it too sounds somewhat lame, a weak reminiscence of a familiar idea from the Midsummer Night’s Dream Overture.

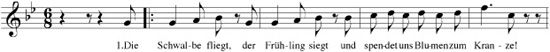

Around the beginning of May 1827 Schlesinger brought out the twelve Gesänge , Op. 8 (the first six had already appeared at the end of 1826). Scholarship has not viewed them as among Felix’s strongest efforts. Admittedly, Op. 8 exudes a certain comfortable domesticity; indeed, several of the texts are by intimates of Felix’s circle, including the poets Karl von Holtei and Friederike Robert, and Droysen, who masqueraded behind the pseudonym of J. N. Voss. Friederike commissioned at least one, No. 6 (the Frühlingslied in Swabian dialect) and specified for its accompaniment a chamber ensemble instead of piano. The song was performed with one flute, one clarinet, two horns, and cello at a Sunday musicale in 1824; later Felix reworked the colorful birdcalls of the flute and clarinet into a piano accompaniment. 45

In a review greeting Op. 8, Marx distributed the songs into groups of courtly love (Minne ), desire (Verlangen ), deep thought (Sinniges ), and contemplation (Anschauung ). 46 Many employ simple strophic settings with repeated music and unobtrusive piano parts. In some, Felix opts for modified-strophic arrangements, with alterations in the vocal line and accompaniment. One example is the operatic Romanze (No. 10), ambiguously labeled aus dem Spanischen , a clue that it was a rejected number from Camacho . 47 Another is the Hexenlied (No. 8), in which Holtei’s image of the Brocken inspired another version of Felix’s supernatural G minor. The most ambitious of the twelve, Hexenlied falls into three sections, of which the first two are identical, while the third takes on its own life and transforms the mischievous staccato work and horn calls of the witches’ dance into blurry piano tremolos and a turn to the major ( ex. 6.5 ).

Other Gesänge aspire toward the artful simplicity of folksong, perhaps none more than the Erntelied (Harvest Song , No. 4), described as an “old church song” and set with austere modal harmonies to convey the grim image of Death the Reaper. Pilgerspruch (Pilgrim’s Saying , No. 5) seeks comfort in the devotional poetry of the seventeenth-century lyricist Paul Fleming. The same verses had inspired Fanny to write a part-song in 1823, 48 and Felix later reused the opening phrase of his Pilgerspruch in the Lied ohne Worte , Op. 38 No. 4 ( ex. 6.6 a, b ). Fanny chided her brother for faulty voice leading in Pilgerspruch , where she uncovered an awkward set of parallel octaves. 49 No innocent bystander, Fanny played a special role in the opus, to which Marx teasingly alluded. No. 12, a setting of Suleika and Hatem’s duet from Goethe’s Westöstlicher Divan , portrayed a “sweet, inward, most pure” form of love, so that one was inclined to label the Lied weiblich (“feminine”), “if there were female composers, and if ladies could absorb such profound music.” Similarly No. 2 (Das Heimweh , “Homesickness”) expressed a certain feminine, languishing quality. As Marx knew, Fanny had composed both, as well as No. 3, Italien , in which she again gave voice to her yearning for southern climes.

Ex. 6.5a: Mendelssohn, Hexenlied , Op. 8 No. 8 (1827)

Ex. 6.5b: Mendelssohn, Hexenlied , Op. 8 No. 8 (1827)

Ex. 6.6a: Mendelssohn, Pilgerspruch , Op. 8 No. 5 (1827)

Ex. 6.6b: Mendelssohn, Lied ohne Worte in A major, Op. 38 No. 4 (1837)

Italien became one of “Felix’s” most popular songs and enjoyed an unusual afterlife. During the 1840s, it inspired A. H. Hoffmann von Fallersleben’s poem Sehnsucht , which appeared in 1848 with Fanny’s music. The sensuous quatrains of Italien were drawn from a poem of the Austrian Franz Grillparzer that had appeared in 1820. 50 Here the poet transports us from the onerous world of prose into a magical Italy of poetry, fragrant olives, cypresses, and murmuring seas, all captured by Fanny’s lilting melody and light chordal accompaniment. When, in 1842, Felix visited Buckingham Palace (see p. 439), Queen Victoria chose to sing Italien and executed its climactic high G as skillfully as any dilettante. 51 After admitting Fanny’s authorship of the song, Felix persuaded Prince Albert to render the Erntelied , whereupon the composer wove motives from both into an improvisation and thus united the feminine and masculine.

Why did Felix subsume three of Fanny’s songs into his own opus? Postmodern standards might vilify his action as artistic theft. But Fanny’s anonymity reflected her time, when many women writers and artists (e.g., the Brontës, George Sand, and George Eliot) adopted masculine pseudonyms to circumvent societal restrictions; indeed, Felix’s aunt Dorothea had published several articles under Friedrich Schlegel’s name. No less meaningful for Fanny than the gender divide was the class divide, which restricted ladies of leisure from pursuing “public” professions. Perhaps for that reason, when Fanny’s first publication, the Lied Die Schwalbe , appeared in an album in 1825, her name was suppressed. 52 In Fanny’s case, her creative voice occasionally merged with that of Felix, a credible stratagem since her compositional style had developed in tandem with his. A balanced view might see Felix’s decision as a compromise, allowing her a public outlet without violating the family’s privacy. Felix’s mantle and Marx’s veiled comments thus offered a limited means of “legitimizing” Fanny’s authorship without exposing her to public scrutiny in the press, all the while preserving lines between the private and public so scrupulously observed in Restoration Berlin. But even this subterfuge was soon enough exposed; John Thomson, after visiting Berlin in 1829, reported about Op. 8 to English music lovers: “three of the best songs,” he wrote, “are by his sister…. I cannot refrain from mentioning Miss Mendelssohn’s name in connection with these songs, more particularly, when I see so many ladies without one atom of genius coming forward to the public with their musical crudities, and, because these are printed, holding up their heads as if they were finished musicians.” 53

During Pentecost in early June 1827, Felix spent idyllic days in Sakrow near Potsdam with a fellow student, Albert Magnus, and composed there the “impromptu” song Frage (Question ). According to Sebastian Hensel, Felix himself crafted the amorous verses, though in 1902 Droysen’s son claimed his father as its author (the song appeared in 1830 as Op. 9 No. 1, with an attribution to J. N. Voss, Gustav Droysen’s pseudonym). 54 Is it true, poet and composer wonder, pausing longingly on a dissonant harmony ( ex. 6.7 ), that a secret admirer asks the moon and stars about him? Only she who shares his feelings and remains faithful can grasp his emotions. Now if Felix actually wrote the poem, who was the object of his affection? A likely candidate is Betty Pistor (1808–1887), who sang in the select Singakademie group Zelter directed on Fridays, when Felix accompanied at the piano. Betty became an intimate of the Mendelssohn children and stirred the younger Felix’s adolescent passion. Frage , in turn, inspired his String Quartet in A minor, Op. 13, the first movement of which he completed, again at Sakrow, on July 28. 55 Did the quartet, which quotes the Lied, symbolize their relationship? The idea does not seem far-fetched, for in 1830 Felix would add a secret dedication to Betty on the manuscript of his next string quartet, Op. 12 in E ♭ major. 56

Ex. 6.7 : Mendelssohn, Frage , Op. 9 No. 1 (1827)

Late in August, at the end of the summer term, Felix joined one of the Magnus brothers, 57 the law student Louis Heydemann, and Eduard Rietz for a holiday. Playfully simulating Ritter’s lectures, they analyzed the geography of the Harz Mountains but lost their way climbing the Brocken. In Wernigerode, Felix made good on a promise to visit the vacationing Betty Pistor. Living a carefree, students’ existence, the friends continued through Franconia and Bavaria, and on September 8 they reached Stuttgart, where Felix met a musician he later hailed as the finest conductor in Germany, P. J. von Lindpaintner. 58 Pausing in Baden-Baden, Felix encountered Ludwig and Friederike Robert, the diplomat Benjamin Constant, and an enthusiastic Frenchman who offered a half-finished opera libretto on the subject of Alfred the Great. Now well advanced into Op. 13, Felix wrote Fanny to ask whether he should incorporate Frage into the work’s conclusion. 59

By September 19 he reached Heidelberg, where he spent several hours with the jurist A. F. J. Thibaut (1772–1840), who in 1814 had argued for codifying German law. When the “Hep-Hep” Riots erupted in 1819, he led his students in defending Jews from attacks. 60 In 1802 Thibaut had begun to collect sacred music and by 1811 was directing an amateur chorus. For Thibaut, ignorance of the musical past, neglect of figured bass, and blending of sacred and secular styles of expression had corrupted music. In Über Reinheit der Tonkunst (On Purity in Music , 1825), he advocated a return to the “pure” style of Palestrina but was less certain about the complex music of J. S. Bach, who had not considered the “needs of ordinary people.” 61 Thibaut’s monograph impressed Felix, but the principal reason for the visit was to consult Thibaut’s library, rich in Italian sacred polyphony of the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries. Just then Felix was beginning to compose the motet Tu es Petrus ; without asking his name Thibaut graciously lent him a setting by the Venetian Antonio Lotti. While Thibaut revealed “the merits of old Italian music,” Felix argued for J. S. Bach’s position as the “fountainhead” in music, and when they parted company Thibaut proposed they build their friendship on Bach and Palestrina, “like two lovers who promise each other to look at the moon, and then fancy they are near each other.” 62

From Heidelberg Felix and friends continued to Darmstadt, where he found the “minister of war for musical affairs,” the theorist Gottfried Weber, who committed a faux pas by labeling Beethoven “half again as crazy as he ever was divine,” so that Felix demoted Weber to a “horse-doctor-like scoundrel.” 63 In Frankfurt Felix stayed with Schelble and saw Hiller, who accompanied the students on an excursion on the Rhine to Cologne. At Horchheim, near Coblenz, Felix, Magnus, and Heydemann disembarked to visit Felix’s uncle Joseph, who owned a substantial estate and vineyards overlooking the river. Felix stayed behind to celebrate the annual vintage and then, with Joseph and his wife, Hinni, traveled to Frankfurt to hear Schelble direct a Handel oratorio. By mid-October, Felix had returned to Berlin, where he spent his first evening in Betty Pistor’s company. 64

On October 27 Felix inscribed the title page to his new string quartet, Op. 13, and a few days later finished a Fugue in E ♭ major for the same scoring, 65 on a subject elaborated from the “Jupiter” motive. If the latter, posthumously published as Op. 81 No. 4, impresses as a student exercise, Op. 13 effects a worthy rapprochement with Beethoven’s late quartets, which preoccupied Felix during 1827. 66 Thus, the outer movements—centered largely on A minor—recall textures from those of Beethoven’s String Quartet in A minor, Op. 132. Beethoven’s late style especially impresses itself on the second movement, a heartfelt Adagio with at least three allusions. The opening is similar to the Cavatina of Beethoven’s Op. 130, which Felix nearly quotes in one passage. The center of the Adagio, a chromatic fugue, invokes the second movement of Beethoven’s Serioso Quartet, Op. 95, and the end of the Adagio revives the high-pitched, ethereal sonority concluding the Heiliger Dankgesang of Beethoven’s Op. 132.

To Lindblad Felix revealed his immersion in Beethoven’s late quartets, which offered a guiding principle for Felix’s own work, “the relation of all 4 or 3 or 2 or 1 movements of a sonata to each other and their respective parts, so that … one already knows the mystery that must be in music.”

67

Linking the movements of Op. 13 are references to Frage

, the “theme” of the entire quartet: “You will hear its notes resound in the first and last movements, and sense its feeling in all four.”

68

Thus, Felix incorporated explicit quotations from the song in the outer movements but left more subtle traces in the inner movements. The Quartet begins by reviving the plagal cadences from the end of the Lied before citing its characteristic dotted-rhythmic motive. Reworked at the beginning of the second movement, this figure is present as well in the ingratiating Intermezzo, where the meter shifts from the  of the Lied to

of the Lied to  (

ex. 6.8a

). The scherzo-like center of the Intermezzo delicately outlines the second phrase of the Lied (

ex. 6.8b

). The impassioned finale, which erupts with a free recitative, assimilates a dotted figure into its primary theme but subsequently recalls material from the first two movements. Eventually, Felix returns to the A-major Adagio with which the composition began and now cites the final thirteen bars of the Lied, completing the thematic circle. The dramatic, questioning recitatives (the first movement ends with a recitative-like gesture, the second movement employs a recitative after the fugue, and the finale has several recitatives) challenge the thematic contents of the composition and lead us inexorably back to the Lied, a technique of recall and denial seemingly related to the finale of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.

(

ex. 6.8a

). The scherzo-like center of the Intermezzo delicately outlines the second phrase of the Lied (

ex. 6.8b

). The impassioned finale, which erupts with a free recitative, assimilates a dotted figure into its primary theme but subsequently recalls material from the first two movements. Eventually, Felix returns to the A-major Adagio with which the composition began and now cites the final thirteen bars of the Lied, completing the thematic circle. The dramatic, questioning recitatives (the first movement ends with a recitative-like gesture, the second movement employs a recitative after the fugue, and the finale has several recitatives) challenge the thematic contents of the composition and lead us inexorably back to the Lied, a technique of recall and denial seemingly related to the finale of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.

Ex. 6.8a: Mendelssohn, String Quartet in A major, Op. 13 (1827), Intermezzo

Ex. 6.8b: Mendelssohn, String Quartet in A major, Op. 13 (1827), Intermezzo

The lyricism of the Quartet broaches a second issue—the extent to which absolute instrumental music can express extramusical ideas. In 1828 Felix began to compose what he later termed Lieder ohne Worte (Songs without Words ), textless piano miniatures that imitate features of art song. Op. 13 anticipated these “piano songs” by transplanting “Ist es wahr?” into the realm of absolute chamber music. Felix’s experiment is not unlike Schubert’s String Quartet in D minor, D810 (1824), in which his Lied Death and the Maiden appears in the slow, theme-and-variations movement and imbues the surrounding movements as well. Though Felix could not have known this masterpiece (published in 1831), the two quartets dismantle in similar ways the boundaries between art song and string quartet. Felix’s frequent recitatives, as if beckoning for a text, remind us again that a vocal model was the direct inspiration for his composition.

During the closing months of 1827, Klingemann’s transfer to the Hanoverian legation in London diminished Felix’s circle. The friend’s absence was the subject of a new, mock literary paper launched by the poet Holtei. The Thee- und Schneezeitung (Tea and Snow Journal ), of which eight issues coalesced between September and November, replaced the Gartenzeitung . 69 Lea reports, however, that Felix declined to contribute to the new undertaking. 70 Meanwhile, he enjoyed making new musical acquaintances. In December the clarinetists Heinrich Baermann and his son Carl appeared in Berlin, 71 and Felix himself participated in two public concerts on November 13 and December 25, when he performed Schubert’s ballade Erlkönig (likely his first exposure to that composer’s music) and Lieder of Mozart and Beethoven. 72 For Rebecka, Felix composed a toy symphony (lost; according to Sebastian Hensel, Felix modeled it on Haydn’s “Toy” Symphony, now known to be by Leopold Mozart) and during the winter months organized a small chorus that began to rehearse on Saturdays “rarely heard works,” including parts of the St. Matthew Passion. 73 Returning in earnest to sacred music, Felix completed rapidly the motet Tu es Petrus , Op. 111, and cantatas Christe, Du Lamm Gottes , presented to Fanny on Christmas Eve, and Jesu, meine Freude , finished on January 22, 1828. 74

The cantatas were the first in a series linked to Felix’s Bachian pursuits, including his study of the Passion and also his examination of W. F. Bach’s musical estate, acquired by Betty Pistor’s father, the astronomer K. P. H. Pistor, after a bidding war with Zelter. To Felix devolved the task of sorting through and organizing the manuscripts, among them thirteen cantatas of J. S. Bach; in exchange, Felix received a priceless gift, the autograph of Cantata No. 133 (Ich freue mich in Dir ) 75 and frequent contacts with Betty. But an incident early in 1828 damaged their budding relationship: upon arriving at the Pistor residence to study the collection, Felix was greeted with laughter from Betty’s friends. The hypersensitive composer took offense and refused to attend her birthday celebration on January 14. When, a few weeks later, Betty’s father forbade her to attend his birthday festivities, the Mendelssohns suspected the reason was anti-Semitism, for some of Betty’s relatives had mocked her as “the music-and Jew-loving cousin.” 76 Eventually the families reconciled, but Felix never again visited the Pistor residence.

Christe, Du Lamm Gottes and Jesu, meine Freude follow closely Bachian prototypes, as if bearing out Berlioz’s observation that Felix studied the music of the dead too closely. 77 Both are in one movement and suspend the chorale melodies in the soprano above a web of imitative counterpoint. Orchestral passages frame the movements and separate the chorale strains. In Christe, Du Lamm Gottes , the Lutheran Agnus Dei appears three times in F major, with the second statement skillfully worked into a jagged, chromatic fugato in F minor. Similarly, Jesu, meine Freude relies upon a minor-major exchange: two-thirds through the composition, the initial E minor shifts to a serene E major for “Gottes Lamm, mein Bräutigam” (“Lamb of God, my bridegroom”), where Johannes Crüger’s chorale melody unfolds against a fresh harmonic coloration.

Initially Felix viewed Tu es Petrus

, composed for Fanny’s birthday (November 14, 1827) but not published until 1868 as Op.111, as among his most successful works.

78

In setting this fundamental Catholic text (“Thou art Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church,” Matthew 16:18), Felix invoked not the Lutheran cantatas of Bach but the Italian stile antico

, which ultimately traced its roots to Palestrina, the sixteenth-century foundation of Roman sacred polyphony.

79

According to Fanny, the score alarmed Felix’s friends, who “began to fear that he might have turned Roman Catholic.”

80

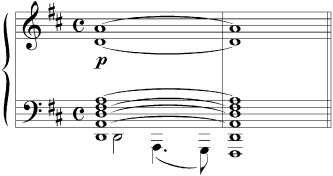

Whether he was able to consult in Thibaut’s library Palestrina’s two settings is unknown, but clearly Felix sought to emulate the Palestrinian ideal—lucid, imitative points of polyphony with carefully regulated dissonances—prized by Thibaut as the “pure” sacred style. Even the appearance of the score, ruled in the archaic meter of  and filled with obsolete breves (double whole notes, =), bespeaks Felix’s fascination with a remote historical period. There is also in the motet a striving for monumentality. Felix specified a chorus in five parts, accompanied by an orchestra expanded to include trombones. Both Felix and Fanny referred to the work as 19 stimmig

(in nineteen parts), and indeed Felix treated the orchestral parts as full participants in the contrapuntal tapestry. After a chordal exordium, the chorus introduces a falling figure in five-part imitation, subsequently magnified by entries in the strings, winds, brass, and even timpani—in all, fourteen entries that suffuse the music with the subject in texted and textless counterpoint, and thus erect a cathedral of sound upon motivic bedrock.

and filled with obsolete breves (double whole notes, =), bespeaks Felix’s fascination with a remote historical period. There is also in the motet a striving for monumentality. Felix specified a chorus in five parts, accompanied by an orchestra expanded to include trombones. Both Felix and Fanny referred to the work as 19 stimmig

(in nineteen parts), and indeed Felix treated the orchestral parts as full participants in the contrapuntal tapestry. After a chordal exordium, the chorus introduces a falling figure in five-part imitation, subsequently magnified by entries in the strings, winds, brass, and even timpani—in all, fourteen entries that suffuse the music with the subject in texted and textless counterpoint, and thus erect a cathedral of sound upon motivic bedrock.

On January 9, 1828 an anonymous poem, Der neuen Zeit (To the New Time ), appeared in Marx’s journal, 81 with an unusual vision of the classical underworld: Ixion is no longer chained to his wheel, Sisyphus successfully rolls his boulder to the top of a mountain, and Tantalus slakes his thirst and tastes the fruit suspended above his head. The three judges of Hades ignore the “empty shades” clamoring to cross the river Styx and enter Elysium, but grant an audience to a youth (likened to Theseus and Hercules), who, reminded that the living have forgotten the great deeds of the departed, returns to the upper world, his soul inspired by the music he has heard in the underworld.

As we know, Droysen was the poet of this dreamlike allegory 82 that celebrated Felix’s efforts to revive the music of the “eternally living dead.” In the Te Deum and Tu es Petrus he had already revived historical periods remote from Bach’s cantatas and the familiar corpus of Protestant chorales. In 1828, Felix continued these historical excavations in another “monumental” motet, Hora est , scored for four four-part choirs and organ continuo. Written for Fanny’s birthday, 83 it was heard at the Singakademie, probably at an early 1829 rehearsal of the St. Matthew Passion and then performed there privately in March 1829 and publicly in November 1829 and January 1830. 84 The inspiration for the motet was a work tied to the Singakademie—Fasch’s identically scored Mass (1786), based in turn upon a sixteen-part Mass by the seventeenth-century composer Orazio Benevoli. Its antiphonal effects, sculpted harmonic blocks, and contrapuntal density offered Fasch a model for his own ideal of sacred music, although he endeavored to improve upon the prototype by rejecting certain licenses of Benevoli, enriching his monochromatic selection of harmonies, and adhering scrupulously to the rule that each four-voice choir should be harmonically independent. Now, in 1828, Felix aspired toward the grandeur of Fasch’s Mass by renewing the techniques of the seventeenth-century polychoral style.

The texts, from the Catholic Office for Advent, comprise the antiphon Hora est and responsory Ecce apparebit . 85 The antiphon summons the faithful from their slumber to behold Christ resplendent in the heavens; the responsory proclaims the Lord will appear upon a white cloud with hosts of saints. For A. B. Marx, who reviewed Hora est , 86 the music explored the mysteries of the monastic rites of early Christendom. The composition projects an unusual tonal pairing, with the dark G minor of Hora est followed by the luminous A major of Ecce apparebit , a juxtaposition calculated to deemphasize the traditional tonic-dominant relationships of tonality in favor of the modal and prototonal colorings of Benevoli’s period. The minor-major contrast and ascending modulation by step underscore the idea of spiritual awakening and renewal. In the first part, priestlike male voices summon the faithful in austere textures that range from monody to four-part harmony. Then, in Ecce apparebit , the four choirs enter as separate harmonic masses. Gradually, they accumulate and spill over into a Più vivace in which all sixteen parts descend in a radiant spiral of imitative counterpoint ( ex. 6.9 ), a level of complexity Felix’s choral music never again attained.

In 1828 Felix enrolled for his second year at the university. During the summer semester he attended lectures by the physicist Paul Erman on light and heat; Ritter on the geography of Asia, Greece, and Italy; and Gans on legal history since the French Revolution. The winter semester, which ran into the early months of 1829, offered the continuation of Gans’s legal history and “natural law or the philosophy of law,” and Hegel’s lectures on aesthetics. 87 One might suppose that Hegel’s views of music piqued Felix’s curiosity, but the search for Hegelian influence on the composer is, in the main, a frustrating enterprise. Though Hegel enjoyed social exchanges with the Mendelssohns, he seems to have used his visits not so much to discuss music as to enjoy whist. 88

Ex. 6.9 : Mendelssohn, Hora est (1828)

In Hegel’s lectures on aesthetics, assembled after his death in 1831 and edited from student notes probably similar to those of Felix, 89 the philosopher elaborated a dialectical approach to the history of art with three principal eras, the archaic or symbolic, classic and romantic. 90 For Hegel art had achieved its most “adequate” representation in the classic period, in which the aesthetic Idea and its form were perfectly united in the idealized human body. But in the romantic (i.e., “Christian”) era, the noncorporeal art of music had distanced itself from classic art and receded into an “unending subjectivity.” Hegel’s sweeping view of art history appears to have elicited skepticism from both Zelter and Felix. Writing to Goethe in March 1829, Zelter observed: “This Hegel now says there is no real music; we have now progressed, but are still quite away from the goal. But that we know as well or not as he, if he could only explain to us in musical jargon whether or not he is on the right path.” 91 Felix too bridled at the Hegelian notion that art had somehow declined, or indeed ceased, “as if it could cease at all!” 92

The life and career of Eduard Gans (1797–1839), with whom Felix studied legal history and natural law, intersected meaningfully with the Mendelssohns, for the jurist’s career was bound up with the question of Jewish assimilation into the modern Prussian state. The son of a prosperous banker who had died insolvent in 1813, Gans studied with Thibaut and finished a dissertation in 1819 on Roman contract law. By 1820 Gans had returned to Berlin and, in the reactionary environment of the Carlsbad Decrees, established a Union for the Culture and Science of Jews. He also joined the Society of Friends (Gesellschaft der Freunde ), organized in 1792 to counter the “terrible state” (Unwesen ) of Orthodox Judaism, and there met two of its founding members, Joseph and Abraham Mendelssohn.

For a while Gans pondered establishing a Jewish colony in America, but instead he came to support the assimilation of Jews into the dominant Prussian culture and likened the process to a river flowing into a sea (“neither the Jews will perish nor Judaism dissolve; in the larger movement of the whole they will seem to have disappeared, and yet they will live on as the river lives on in the ocean” 93 ). But when Gans sought a professorship at the university, the king summarily declared Jews ineligible. Gans’s conversion to Christianity in 1825 enabled him to join the faculty, and he became Hegel’s friend and eventually prepared his Philosophy of Law for publication in 1833. In politics Gans adopted increasingly liberal views, and when he commented favorably about the July 1830 Revolution in Paris, his lectures, which drew audiences of over a thousand, came under suspicion from the authorities. Felix’s 1828 lecture notes clarify that Gans viewed the French Revolution as the defining moment of the modern period, when “all other histories paused,” and when the Hegelian dialectical process indelibly affected the ancien regime ; thus, Prussia was no longer an absolute state, but a “guardianship” state. 94 Gans’s fervent desire, well ahead of his time, was to advance a pan-European synthesis. While playing out the unpredictable role of the assimilated Jew in Berlin society, Gans enjoyed social intercourse with the Mendelssohns and became the “commander and protector of the younger ones.” 95 A “mixture of man, child, and savage,” 96 he actively pressed for the hand of Rebecka, with whom he read Plato, but in 1831, as we shall see, lost the prize to a worthy competitor.

Between lectures Felix pursued several new compositions. In January 1828, he drafted a sprightly Etude in E minor, later reused in the Rondo capriccioso , Op. 14. 97 By February a considerably larger work was forming in his mind, an orchestral overture on Goethe’s two short poems Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage (Meeresstille und glückliche Fahrt ). 98 Felix’s musical inspiration was once again Beethoven, for whom a memorial concert, in which Felix performed a piano trio, was given on March 26. 99 Beethoven’s cantata, Op. 112 on the same poems had appeared in 1822, and in 1824 Marx had actually criticized his favorite composer for representing the solitude of a becalmed vessel by a chorus and orchestra. 100 Quite likely Marx encouraged Felix to “set” the poems without text, as part of the theorist’s agendum to test music’s capacity to express substantive ideas. Indeed, in a spirited defense of programmatic music published in May 1828, Über Malerei in der Tonkunst (On Painting in Music ), Marx identified Felix as a “student” of Beethoven who had brought “this idea to perfection, expressing Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage without using Goethe’s words,” 101 as if Marx were already familiar with Felix’s score (the first version was not performed until September).

Among Felix’s lesser works of the year is a setting of the Marian antiphon Ave maris stella , commissioned in June by the prima donna Anna Milder-Hauptmann, whom Lea described as a “cold princess.” 102 Composed on one day in July, it received its premiere at the Berlin Marienkirche on May 27, 1829. 103 Felix divided the celebrated Vespers hymn into two sections. Mary’s invocations (Ave maris stella, … funda nos in pace , “Hail, star of the sea,” … “disperse us in peace”) are set in a quasi-operatic, Mozartean vein, with florid embellishments tailored for Milder’s voice. A dissonant Allegro in the minor mode forms the center of the work, with energetic supplications for solve vincla reis (“Loosen the chains of evil”), which yield to an abridged return of the opening, lending the work a rounded ternary, ABÁ shape.

“You see [Felix] is the fashion,” Fanny wrote to Klingemann; 104 indeed, 1828 brought two commissions—the tercentenary of Albrecht Dürer’s death in April, and an assembly of physicians and scientists in September. Felix hurriedly composed two festive cantatas, which have fallen into obscurity, largely owing to their mediocre texts. Sebastian Hensel described the occasions as “universal festivals,” by which “the Germans tried to forget their want of political union”; 105 the nationalistic subtexts of the cantatas are certainly not difficult to discern.

On the first occasion (April 18, 1828) the philologist E. H. Tölken extolled Dürer as the founder of German art, and the archaeologist Konrad Levezow celebrated Dürer’s art as a testimonial to Christian piety. 106 Held in the Singakademie before a royal audience, the festival was a lavish affair, with decorations by Johann Gottfried Schadow and Schinkel. Behind the orchestra appeared a wall in the patriotic colors of red and gold, and in the center stood a six-foot statue of Dürer, framed by smaller statues symbolizing four facets of his work—painting, geometry, perspective, and military engineering. Above the statue loomed a painting based upon a Dürer woodcut (The Peace of the World Redeemer in the Lap of the Everlasting Father ). 107 For the overture Felix pressed into service the Trumpet Overture. After Tölken’s address came the cantata, a score of 143 pages lasting one hour and fifteen minutes. At a dinner feast Schadow feted Felix and proclaimed him an honorary member of the Academy of Art.

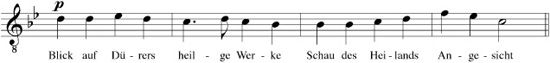

From all indications, Felix struggled to find inspiration in Levezow’s insipid verses. Composed in February and March in about six weeks, the cantata included choruses, solo arias, and recitatives (“dry,” i.e., performed at a piano, and “accompanied,” with orchestral support)—in all fifteen numbers divided into two parts, each culminating in a fugue. The choruses and arias are thoroughly Handelian and reflect Zelter’s deepening attraction to that composer, evidenced by Zelter’s performances of Joshua (1827), Judas Maccabaeus , Alexander’s Feast , and Samson (1828), and Messiah (1829; a planned performance of Acis and Galatea in an arrangement by Felix did not materialize). 108 The distinctly Bachian recitatives seem to anticipate Felix’s efforts to commemorate the Thomaskantor the following year by reviving the St. Matthew Passion.

Ex. 6.10 : Mendelssohn, Dürer Cantata (1828), No. 1

The cantata opens with an expansive plagal cadence later reworked in the unusual conclusion of the Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage Overture ( ex. 6.10 ). The ensuing orchestral Festmusik presents three strains of a marchlike theme that recurs throughout the cantata as a unifying device; in the first number, this theme leads to a chorus imploring the temple of art to open its gate to an unnamed artist, not identified until the third number, where Felix was unable to elevate musically Levezow’s mundane revelation, “Albrecht Dürer ward er genannt” (“He was called Albrecht Dürer”). There follows a review of the virtuous Dürer, who rises to the heavens, aided by flowery metaphors—he is a rock uplifted to the clouds, an eagle soaring beneath the sun.

The second part associates Dürer’s divine gifts with Christ the Redeemer. “Gaze upon Dürer’s sacred works,” the amateur poet urges, and the devout will “see the countenance of the Redeemer,” the “radiant light of hope.” Here Felix conceived the most imaginative portion of the score (No. 10), a tenor aria with violin solo (written for Eduard Rietz) and chorus. In the text the burning tears of a penitent find solace in Dürer’s sacred art. The music begins with a questioning recitative for the violin, which then introduces a falling, sighing figure accompanied by string chords ( ex. 6.11a ). A simple chorale-like melody ( ex. 6.11b ) expresses the restorative power of Dürer’s art. These two thematic elements alternate before the movement concludes with more recitative-like flourishes in the solo violin. The sobering, G-minor tints and brooding tremolos of the aria left their mark on the slow movement of the Reformation Symphony ( ex. 6.11c ), which Felix may have associated with the forceful spirituality of Dürer’s art.

For one of the soloists, Eduard Devrient, the cantata did not reflect Felix’s genius. 109 Nor was Devrient convinced by Felix’s cantata for Alexander von Humboldt, who in 1827 had returned to Berlin as the Prussian monarch’s scientific and cultural advisor. Initially, the world-traveled scientist faced an uncertain repatriation, since some nobility regarded him as a Francophile, but he allayed this concern in November, by lecturing on geography at the university. These lectures, which ran through April 1828, later formed the basis of his masterpiece, Cosmos , a two-thousand-page “sketch of a physical description of the universe.” Their success encouraged Humboldt to offer at the Singakademie additional lectures, open to the public; here, in a forum most unusual for the time, royalty, aristocrats, commoners, and women attended, among them, Fanny (“Gentlemen may laugh as much as they like,” she wrote, “but it is delightful that we too have the opportunity given us of listening to clever men” 110 ).

Ex. 6.11a: Mendelssohn, Dürer Cantata (1828), No. 10

Ex. 6.11b: Mendelssohn, Dürer Cantata (1828), No. 10

Ex. 6.11c: Mendelssohn, Reformation Symphony, Op. 107 (1830), Andante

Humboldt endeavored to counteract the influence of the “nature philosophers,” including Hegel, who wished to “comprehend nature a priori by means of intuitive processes … without using scientific methodology.” 111 A new opportunity to promote Humboldt’s agendum came in September, when the state allowed him to convene an international convention of naturalists and physicians. Six hundred scientists converged upon Berlin, including the Englishman Charles Babbage, who in 1833 would design a prototypical calculator, and the mathematical genius Carl Friedrich Gauss, who piqued Humboldt’s interest in terrestrial magnetism. From Warsaw came Professor Jarocki, traveling with an introverted, eighteen-year-old musician, Frédéric Chopin, who saw Felix but was too insecure to approach him. 112 At the opening session in the Singakademie (September 18, 1828), Felix directed his cantata, and Humboldt gave an address on the social utility of science.

The text of the cantata, by Ludwig Rellstab, charts the progress of the natural world from chaos to unity. Midway in the work a voice of reason interrupts the earth’s struggle against the raging elements, and the light of truth countervails the strife. Now the competing forces collaborate to create the “glorious world,” and the Lord is asked to “bless the strivings of the united force” ( ex. 6.12 ). Writing to Klingemann, Fanny commented on Felix’s unusual scoring—male choir, clarinets, horns, trumpets, timpani, cellos, and double basses: “As the naturalists follow the rule of Mahomet and exclude women from their paradise, the choir consists only of the best male voices of the capital.” 113 Felix chose a male choir to invoke the sound and traditions of male singing societies in Berlin, including Zelter’s Liedertafel , founded in 1809 during the French occupation. Thus, Felix’s music, apportioned into seven choruses, solo numbers, and recitatives, relies less on the Handelian and Bachian models of the Dürer Cantata than on the male choruses of Weber’s Der Freischütz , which evoke a brand of German patriotism associated not so much with the court as with the educated middle class.

Ex. 6.12 : Mendelssohn, Humboldt Cantata (1828)

As an occasional piece the Humboldt Cantata was quickly forgotten, though it later had a strange political afterlife: in 1959, the centenary of the scientist’s death, Felix’s score was revived by the German Democratic Republic. An article appeared in the East German journal Musik und Gesellschaft , where quotations from Rellstab’s text were retouched to conform to the needs of a secular state. Thus, in the final chorus, “Ja, segne Herr was wir bereiten” (“Yes, bless, O Lord, what we prepare”) became “Ja, schützet nun, was wir bereiten” (“Yes, now protect what we prepare”). 114 Alexander von Humboldt’s reaction to the 1828 premiere is not known, although the conference did bring him closer to the Mendelssohns. At Gauss’s urging he renewed his interest in magnetic observations and constructed a copper hut in the garden of Leipzigerstrasse No. 3. Here, while Felix rehearsed the St. Matthew Passion in the Gartensaal , Humboldt and his colleagues recorded changes in the magnetic declination, measurements also taken concurrently in Paris and at the bottom of a mine in Freiberg. Within a few years, what had begun in the Mendelssohns’ garden as a modest laboratory became part of a “chain of geomagnetic observation stations” that stretched around the world, an early instance of international scientific exchange. 115

Felix’s most significant accomplishment of 1828 was the orchestral overture on Goethe’s Meeresstille und glückliche Fahrt . In 1787, returning from Sicily to Italy on a French merchantman, the poet had been becalmed within sight of Capri. A resurgent wind averted disaster when the ship began to drift toward the Faraglioni Rocks, and in 1795 Goethe compressed his experiences—including the “deathly stillness” and “monstrous” breadth of the ocean—into the two poems. Now, in 1828, Felix, having seen the ocean only once (at Bad Doberan in 1824) and never having sailed, endeavored to translate Goethe’s metaphors of stasis and kinesis into orchestral images, as an example of Marxian programmatic music.

Marx’s treatise Über Malerei in der Tonkunst had allied “modern” music with the visual arts to reorient the Horatian simile linking poetry and painting, to explore ties between painting and music. Felix’s musical inspiration was Beethoven’s cantata—among other similarities, the two works share their key, D major, display broadly spaced sonorities, and are bipartite, with linking transitions 116 —yet there is compelling evidence Felix approached his score as a tone painting. Thus, he “wanted to avoid an overture with [a slow] introduction”; rather, the work comprised “two separate tableaux.” 117 What is more, Lea reported that around this time Felix began to paint, 118 an activity that found its counterpart in Felix’s manipulation of instrumental colors and timbres. To expand the orchestral palette and extremes of its registers, he added a piccolo, contrabassoon, and serpent (a now obsolete bass instrument related to the cornet family), and, in the coda, a third trumpet. And he experimented with subtle instrumental mixtures, as in the opening harmony, a symmetrical string sonority, the middle of which is inflected by clarinets and bassoons ( ex. 6.13a ). Calm Sea projects static pedal points in the neutral strings, with occasional touches of woodwinds, and, at the end, a fluttering figure in the flute, the first suggestion of a breeze. In contrast, Prosperous Voyage begins with a transition energized by woodwind and brass chords, as, in Goethe’s classical allusion, Aeolus releases his winds.

Ex. 6.13a: Mendelssohn, Calm Sea (1828)

Ex. 6.13b: Mendelssohn, Prosperous Voyage (1828)

Ex. 6.13c: Mendelssohn, Prosperous Voyage (1828)

The thematic material of the overture derives from a murky motive, initially submerged in the contrabass, that outlines the tonic D-major triad in its unstable first-inversion, descending from the root D through A to F#. This motive washes over much of Calm Sea , as in bars 36–40, where five statements appear in the first and second violins, clarinet, cellos, and double bass, and underscore the impenetrable, static quality of Goethe’s verse. But in Prosperous Voyage , the motive undergoes metamorphosis. Its characteristic dotted rhythm reemerges in the windswept first theme, while the lyrical second theme, which later served as a musical greeting between Felix and Droysen, outlines the motive in ascending form ( ex. 6.13b, c ). The tonal stasis of Calm Sea , primarily associated with a D major destabilized by non-root-position chords, gives way in Prosperous Voyage to a tonal voyage in sonata form that eventually finds haven in the port. The coda depicts the triumphant ending of the journey, a scene conceived by Felix (Goethe’s poem ends with just the sighting of land): the dropping of anchor, cannonades from the shore greeting the vessel, and joyous fanfares performed by three trumpets, which secure the tonic triad in root position. But the surprise ending, with its pianissimo plagal cadence (D major–G-major–D-major), brings us full circle to the beginning, where the inaugural harmonic progression moves to the subdominant G major. As in the Midsummer Night’s Dream Overture, the end thus refers to the beginning, and Felix emerges as a romantic tone poet, whose vivid score not only depicts images in Goethe’s poetry but also extrapolates from its verses new interpretations.

After Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage was premiered privately on September 7, 1828, 119 the concertmaster of the king’s orchestra, Leopold Ganz, offered to present it publicly. But Felix declined for two reasons. 120 In effect, he himself had become becalmed in his compositions; the public was tired of his work, and he had “gently slipped into forgetfulness,” where he wished to remain until his own return from travels abroad. Felix was still recovering from the failure of Camacho and the intense scrutiny of the public eye. There was, however, another cause for concern: “It was a great grief to me to hear that the King’s band has refused to be led by me in public; but I cannot feel hurt, for I am too young and too little thought of.” The exact nature of this contretemps—perhaps it was an anti-Semitic incident—remains a mystery, but the hurt was sufficient to convince Felix to withdraw. Not until 1832 was the overture heard publicly in Berlin; meanwhile, he repeated it at his residence, including at least one performance with Fanny as a piano duet, with lights dimmed to create the appropriate mood. 121

For much of 1828 Felix’s studies kept him in Berlin. The holidays, though, permitted some travel. Around Pentecost in May he escorted his brother, Paul, and school friends on a walking tour of Eberswalde, a summer resort northeast of Berlin. There they visited modern factories and drank Bierkaltschale with Droysen and Ferdinand David. And in October, between the semesters, Felix traveled to Brandenburg, where he met Justizrat Steinbeck, director of the local Singverein. At the piano Felix rendered Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony and at the local churches performed fugues from the Well-Tempered Clavier and as many Bach organ works as Felix knew from memory. At a pastor’s behest, Felix even endeavored to explain to some military officers the mysteries of fugues. The pièce de résistance was his improvisation on Christe, Du Lamm Gottes , which, Felix explained to Lea, Fanny could play for her since Fanny already knew it by heart and understood thoroughly his “manner.” 122

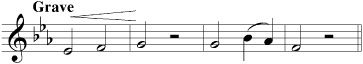

Upon returning to Berlin, Felix celebrated Fanny’s and Zelter’s birthdays. For Fanny, he completed Hora est and some piano pieces, including examples of the new Lied ohne Worte . To Klingemann, Fanny divulged that Felix had “lately written several beautiful ones,” though only one from 1828, a Lied in E ♭ major recorded on her birthday, has survived. 123 Its lyrical melody and chordal accompaniment provided a prototype for several piano Lieder that followed; indeed, one passage, marked Grave , impresses as a sketch for the Lied ohne Worte Op. 19b No. 4 ( ex. 6.14a, b , 1829). Felix’s textless songs of 1828 may have been related to a musical game he had played as a child with his sister, in which they devised verses to fit to instrumental pieces. 124 If so, Fanny may have played a role in developing the new genre; the Lieder may have been a “means of communication for Felix and Fanny,” 125 though Charles Gounod’s assertion, that Felix published several of Fanny’s Lieder ohne Worte under his name, has never been proven. 126

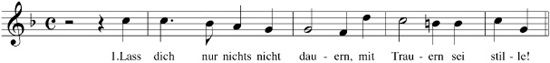

On Zelter’s seventieth birthday (December 11, 1828) the Singakademie held a grand celebration. Goethe contributed verses symbolically uniting the arts of architecture, poetry, and singing, but this time the task of composing a festive cantata fell to Zelter’s assistant, C. F. Rungenhagen. 127 Was Felix asked to set the verses but declined? We do not know, though he did contribute a modest part-song for male voices, the Tischlied “Lasset heut am edlen Ort,” hastily set to verses Goethe dispatched to Berlin on December 6. 128

Ex. 6.14a: Mendelssohn, Grave (1828)

Ex. 6.14b: Mendelssohn, Lied ohne Worte in A major, Op. 19b No. 4 (1829)

Hardly less festive were the Christmas celebrations in the Mendelssohn residence. Felix composed another toy symphony (lost), and the circle of friends expanded to greet new arrivals, including the mathematician Peter Gustav Lejeune Dirichlet (1805–1859), whom Alexander von Humboldt introduced to the family. In Cologne, Dirichlet had studied with G. S. Ohm, formulator of the law of electric resistance (1827). When Dirichlet became enamored of Rebecka, Gans quarreled and fought with him “like a schoolboy” 129 and endeavored to win the prize by reading Plato in Greek with her (their relationship, Fanny noted wryly, remained Platonic). Dirichlet joined the faculty of the university in 1831, the year of his engagement to Rebecka. They married the next year and lived in Berlin until 1855, when he filled a vacancy at the University of Göttingen caused by the death of the century’s leading mathematician, Gauss. 130

In October another suitor, Wilhelm Hensel, arrived after five years in Italy. Since he had not been allowed to correspond with Fanny, they had grown apart. The old circle of friends had changed (according to Sebastian Hensel; the new circle practiced a “coterie-slang not intelligible to the uninitiated”); 131 Fanny had developed an intimate psychological dependence on Felix, through whom she sublimated her musical needs, arousing Wilhelm’s jealousy; and the family was pulled toward politically liberal views through their friendship with Gans. Meanwhile, Wilhelm had become more conservative and expressed royalist leanings. Nevertheless, Fanny and Wilhelm rekindled their relationship; on Christmas Eve, he gave her a miniature Florentine pocket album in the shape of a heart, with delicately scalloped, gilded pages, in which he inscribed, “This little book is very like the heart,/You write in it joy or sorrow.” 132 Here, through August 1833, Fanny recorded musical sketches, while her fiancé and, later, husband entered poems and drawings around events in the couple’s lives, including Fanny’s pregnancy and the birth of their son Sebastian in 1830, and the tragic delivery of a stillborn daughter in 1832.

From Italy Hensel had brought his imposing canvas Christ and the Samaritan Woman by the Well and the copy of Raphael’s Transfiguration . Viewing the paintings at the Academy of Art, the king noted that the artist had “not used his time in Rome unproductively.” 133 In January 1829 the academy nominated Hensel for membership, clearing the way for his appointment as court painter. His improving prospects overcame Lea’s lingering reservations, and on January 22 Fanny and Wilhelm were engaged. In a poem for the occasion, Hensel contrasted the cold Berlin winter with the rejuvenating springtime within his breast. 134 On February 2 the lovers resumed corresponding, and the next day they were alone together for the first time. 135 Through Wilhelm’s servant, they exchanged daily letters. Twenty-one have survived (February–October 1829), including thirteen by Fanny available to Sebastian but suppressed in Die Familie Mendelssohn , where he alluded only to their “truly pathetic, heart-moving beauty.” 136 With filial devotion Sebastian strove to preserve the harmonious image of his parents’ relationship; still, reading between the lines of his account suggests the engagement was anything but smooth. Thus, Fanny’s “constant task” was “to shape two natures into one harmonious integrity.” 137 Indeed, the letters, published only in 1995, 138 reveal a troubled engagement, as do several elliptical entries in Fanny’s diary. In January, Fanny took exception to one of Wilhelm’s drawings of her; on February 4 there was controversy about one of his letters; on February 17 he had a fit of jealousy; and on March 1 there was a dramatic scene with Lea about the wedding. Only on March 19 did Fanny feel “truly engaged”; yet, at the end of September, just days before the wedding, she noted another Streit . Through all this, Wilhelm impresses as an emotionally distraught, insecure man of thirty-five; Fanny, at twenty-three, as a woman bent on mollifying her fiancé, while becoming increasingly anxious herself about Felix’s impending departure for England.

The early weeks of the engagement coincided with the intensifying rehearsals of the St. Matthew Passion, in which Fanny was intimately involved, even though her role was subordinate: while Felix conducted Bach’s masterpiece before the social elite of Berlin, Fanny sang as an alto in the chorus, reinforcing the gender divide between public and private. Eyewitness accounts of Eduard and Therese Devrient, Marx, Fanny, Schubring, and Zelter, among others, document the preparations for the event, Felix’s two performances in March, and their enthusiastic reception. 139 But the primary sources contain inconsistencies, and the significance of the revival—the prime mover in the nineteenth-century rediscovery of Bach—has provoked no little controversy.

The revival began as a private initiative at the Mendelssohn residence, where Felix assembled a small chorus of friends to rehearse portions of the Passion. Schubring informs us that the devotees numbered only about sixteen, including the Devrients, Schubring, his theology classmate E. F. A. Bauer, and the painter and art historian Franz Bugler. At this stage Felix merely intended to explore the Passion to disprove Schubring’s skeptical assertion that Bach’s music offered only a “dry arithmetical sum.” 140 But another incentive may have been Marx’s announcement in April 1828 of Schlesinger’s decision to publish the work. Appearing in 1830, Marx’s piano-vocal score of the Passion was an important by-product of Felix’s performances; indeed, Marx used his journal to wage a “press campaign” for the work and issued a stream of reports before and after the performances in March and April 1829. 141

Exactly when the rehearsals at Leipzigerstrasse No. 3 began remains unclear. Eduard Devrient claims they were underway by the winter of 1827, while his wife Therese dates the first meetings from October 1828. 142 Initially, like Zelter, Felix had no thought of a public revival; rather, the rehearsals were intended for the private edification of his circle. To venture before the public was to raise formidable obstacles: largely ignorant of Bach’s music, Berlin audiences would not tolerate the complexities of the Passion, and its unusual scoring—requiring two orchestras and two choruses—offered another hindrance. But as the rehearsals advanced, a new musical world opened to Felix. In particular, the “impersonation of the several characters of the Gospel by different voices” impressed Eduard Devrient as the “pith of the work,” a practice “long forgotten” in old church music. 143 Devrient yearned to sing the role of Christ and to realize through performance the dramatic continuity of the Passion.

The rest of Devrient’s entertaining account is well known: how, one day in January 1829, he roused Felix from his slumber to convince him to perform the work, how the two set off to Zelter, how Zelter demurred, comparing the venture to the brazen child’s play of two “snot-nosed brats” (Rotznasen ), how Devrient held firm and overcame Zelter’s resistance, and how the two—dressed in a Passionsuniform of blue coats, white waistcoats, black neckties and trousers, and yellow leather gloves—enlisted the vocal soloists from the Royal opera and secured the approval of the Singakademie management. Finally, Felix captured the significance of the undertaking with the observation, “And to think that it has to be an actor and a young Jew who return to the people the greatest Christian music!” 144

Other documents encourage us to refine Devrient’s account. First, the issue of the performance was raised not in January but a few weeks earlier: on December 13 Felix and Eduard petitioned the Singakademie to use the hall for the performance, which was granted in exchange for a fee of fifty thalers. 145 Around this time, the two friends must have come to terms with Zelter, for on December 27 Fanny was able to report to Klingemann about another “special” condition not mentioned by Devrient: “[Felix] has many different projects before him, and is arranging for the Academy Handel’s cantata Acis and Galatea , in return for which the Academy will sing for him and Devrient the Passion, to be performed during the winter for a charitable cause….” 146 Felix sent his arrangement to Zelter on January 8 and promised to begin work on another one, of a Handel Te Deum . 147

We can identify three other concurrent “projects.” From Fanny’s diary, we know Felix was absorbed in a “heavenly symphony”; indeed, on January 3, Fanny recorded in her heart-shaped diary a few bars from the finale of the Reformation Symphony, proving her brother was already pondering that composition early in 1829. 148 Then, at the end of the month, he dated the autograph of the Andante con variazioni for cello and piano, 149 published in 1830 as the Variations concertantes Op. 17. Built upon a graceful D-major theme, the work comprises eight variations, of which the first six adhere closely to the theme. But in the turbulent seventh variation in D minor, the piano part erupts in a martellato octave passage that disrupts the symmetry of the theme. In the final variation, the theme returns, only to undergo expansion in a free, stretto-like coda before the composition comes to a tranquil close. Dedicated to the composer’s brother, the variations reveal Paul to have been an amateur cellist of considerable ability.

Felix’s third project from this period proved more burdensome: on February 23 he completed a recitative and aria for soprano and orchestra, “respectfully dedicated” to Anna Milder-Hauptmann—one might speculate, in exchange for her agreement to sing one of the soprano roles in the Passion. Only a few pages of the score survive, revealing a fairly conventional recitative with agitated string tremolos (Tutto è silenzio ), in which we learn that the unidentified character has been accused of murdering her husband, and the beginning of a soothing Handelian aria (Dei clementi , “Merciful gods”). 150 In April, after Felix departed for England, Fanny rehearsed this piece with the prima donna, who insisted Fanny phrase the vocal part, a request she considered ridiculous but agreed to oblige, as she realized how “thoroughly sick” Felix had become of the composition. 151

On February 2 choral rehearsals of the Passion began in the Singakademie, one day before Felix’s twentieth birthday, when wind musicians serenaded him with arrangements of the Doberan Harmoniemusik and Overture to Camacho . Joining the celebration, Ludwig Robert contributed a poem inspired by the piano fugue for Hanstein (see p. 172), and Wilhelm gave Felix Jean Paul’s serendipitous novel of adolescent awakening, Flegeljahre (Fledgling Years ; 152 two years later the novel’s twins, Walt and Vult, would inspire Robert Schumann to compose the piano cycle Papillons ). As the rehearsals continued, additional members of the Singakademie augmented the chorus. Felix rehearsed from the piano until the orchestra joined the chorus on March 6. The dress rehearsal was held on March 10, and the following evening he presented Bach’s masterpiece publicly for the first time in one hundred years.

The soloists were the sopranos Anna Milder-Hauptmann and seventeen-year-old Pauline von Schätzel, alto Auguste Türrschmidt, tenors Heinrich Stümer (Evangelist) and Carl Adam Bader (Peter), baritone Eduard Devrient (Christ), and basses J. E. Busolt (High Priest and Governor) and Weppler (Judas). The chorus was 158 strong (47 sopranos, 36 altos, 34 tenors, and 41 basses), nowhere near the 300 to 400 mentioned in Devrient’s account. 153 Most of the orchestral personnel were amateurs from the Philharmonische Gesellschaft founded by Eduard Rietz in 1826 (the first chairs of the strings and the winds were members of the royal Kapelle). Using a baton, Felix conducted from a piano placed diagonally on the stage, with the first chorus behind and second chorus and orchestra before him. According to Devrient, instead of continually beating time, Felix occasionally lowered his baton, so as to “influence without obtruding himself.” 154 Therese Devrient reported that the familiar Protestant chorales were sung a cappella , though Marx, contradicting her claim, maintained the orchestra accompanied all the chorales except Wenn ich einmal soll scheiden . 155