Chapter 1 Going Blended to Meet the World

Learning should look like it is built for each student, it should be unique to them, not just the same thing for every single student. If it looks designed for the student you can draw their attention and keep it.

—Kyrie Kennemore, 9th Grade

Scaling Blended Learning Transformation

We’ve written this book with systemwide transformation in mind. Although we speak regularly about strategic, incremental changes, this is not about tinkering at the edges. Our goal is to support meaningful change at scale. Ultimately, blended learning is about reinventing what learning looks like for students, and even schools. The schools that win today are the ones that build cultures of sustained learning and innovation across all levels and stakeholder groups. In blended learning terms, winning does not require that other schools lose. In fact, because of the inherent network effects of blended learning, the more schools that build cultures of learning and innovation, the more the collective tide will rise. Through sustained innovation shared over time, transformation is not only possible, it is inevitable.

The seismic shift that education is experiencing demands proactive planning, design, and implementation that is also systemic in nature. It is no longer enough for one progressive teacher to “get it,” because then the only students who benefit are the ones lucky enough to be in that teacher’s class. It is no longer enough for principals, superintendents, and other school leaders to maintain the status quo. All stakeholders must be engaged and involved in the process of shifting behaviors, practices, and culture.

This chapter

- explains the hallmarks of blended learning;

- describes the importance of culture to the success of an organization;

- explores the unique characteristics of a blended learning culture;

- identifies the key stakeholders who should be involved and considered in a blended learning transformation; and

- discusses why this transformation is so important right now.

Clearing Up Blended Learning Confusion

There are many definitions of blended learning. The most frequently referenced comes from a nonprofit, nonpartisan think tank, the Christensen Institute, which states,

Blended Learning is a formal education program in which a student learns: (1) at least in part through online learning, with some element of student control over time, place, path, and/or pace; (2) at least in part in a supervised brick-and-mortar location away from home; (3) and the modalities along each student’s learning path within a course or subject are connected to provide an integrated learning experience.

Sometimes the conversation about blended learning includes references to personalized learning, digital learning, 21st-century learning, and next generation classrooms.

The purpose of this book is not to create a new definition. The evolving nature of technology and its potential application mandates a dynamic and similarly evolving understanding of “blended learning.” Instead, we remain practical, providing readers with scalable classroom practices and examples of theory in action. When successfully implemented, blended learning enables these hallmarks of best teaching and learning practices:

- Personalization: providing unique learning pathways for individual students

- Agency: giving learners opportunities to participate in key decisions in their learning experience

- Authentic Audience: giving learners the opportunity to create for a real audience both locally and globally

- Connectivity: giving learners opportunities to experience learning in collaboration with peers and experts locally and globally

- Creativity: providing learners individual and collaborative opportunities to make things that matter while building skills for their future

The goal of this book is to help educators blend the tools and modalities at their disposal to facilitate the best instruction to meet individual student learning needs. The blended learning models presented here are frameworks and starting points, not end points. Ideally, schools become true learning communities capable of adapting approaches and models to meet their unique needs. This book is designed to provide a foundation so that educators can make the right decisions for the needs of their unique instructional environments.

It Starts With Culture

Business management guru Peter Drucker is credited with the phrase, “culture eats strategy for breakfast.” This is not to say that strategy isn’t important but instead to emphasize that the culture of an organization is the first and greatest determinant of the success or failure of that organization and any initiative that it undertakes. Culture can be described in a number of ways:

- The operationalizing of an organization’s values (Aulet, 2014). A balanced blend of human psychology, attitudes, actions, and beliefs that combined create either pleasure or pain, serious momentum or miserable stagnation. (Parr, 2012)

- A system of shared assumptions, values, and beliefs, which governs how people behave in organizations. (McLaughlin, 2016)

- The way that an organization and its people do things and how they feel when they are doing them.

The common theme of any definition of culture is that it is based on shared values, created and perpetuated by people. These values, attitudes, and beliefs combine to yield patterns of behavior, and consequently impact how stakeholders feel about these behaviors. Heath and Heath assert that behavior is contagious particularly in ambiguous situations and “people look to others for cues about how to interpret the event” (Heath & Heath, 2010, p. 226). Leaders managing a blended learning change initiative must be aware of this and align individual and group motivation and rationale with a climate and conditions that support the desired change. Heath and Heath refer to this process in three parts: 1) Directing the rider—providing clear rationale and direction, 2) Motivating the elephant—inspiring feeling and desire to change, and 3) Shaping the path—building the culture and conditions (Heath & Heath, 2010).

Steve Wilcox, CEO of Aspire Public Schools, describes the Aspire culture as one of confident humility.

We’re confident enough to try new things and not worry too much that we’ll be criticized or penalized too harshly for failure or a drop in results. We’re confident enough to know we are not the experts, but we know some things that position us well to try, learn, fail, and try again. We’re confident enough to say: “We’re doing this our way, at a pace that fits our culture, and aligned with our mission as an organization.” At the same time, we are also humble enough to know we learn everyday from other educators, schools, and systems in powerful ways. We’re humble enough to sit and learn from (and with) others who are struggling through the same challenges or who are kind enough to help us even when the issues we’re struggling to solve are ones they’ve solved long ago. (Arney, 2015, p. xiii)

This sentiment is critical for blended learning schools to risk trying new things while remaining open to learning and honoring their unique strengths and challenges.

A Blended Learning Culture

In a blended learning culture, stakeholders are empowered to take greater ownership of their respective responsibilities. Students become agents and owners of their learning process. In the Summit Schools (a nonprofit network of innovative, blended public high schools) this can be observed with daily project time, where students explore real-world projects as problem-solvers and innovators and often present their own findings, analyses, and recommendations. In the blended learning hubs at Rio Vista Middle School in California, teachers outline learning objectives and students choose their learning path based on their interests. In blended learning schools, schooling does not happen to students. Students are drivers of their learning, even at early ages. Simultaneously, schools, district leaders, and teachers become both facilitators of student learning and 21st-century learners themselves. A blended learning school is a true community of learners who have vested participation in the ultimate manifestation of the learning environment and experience.

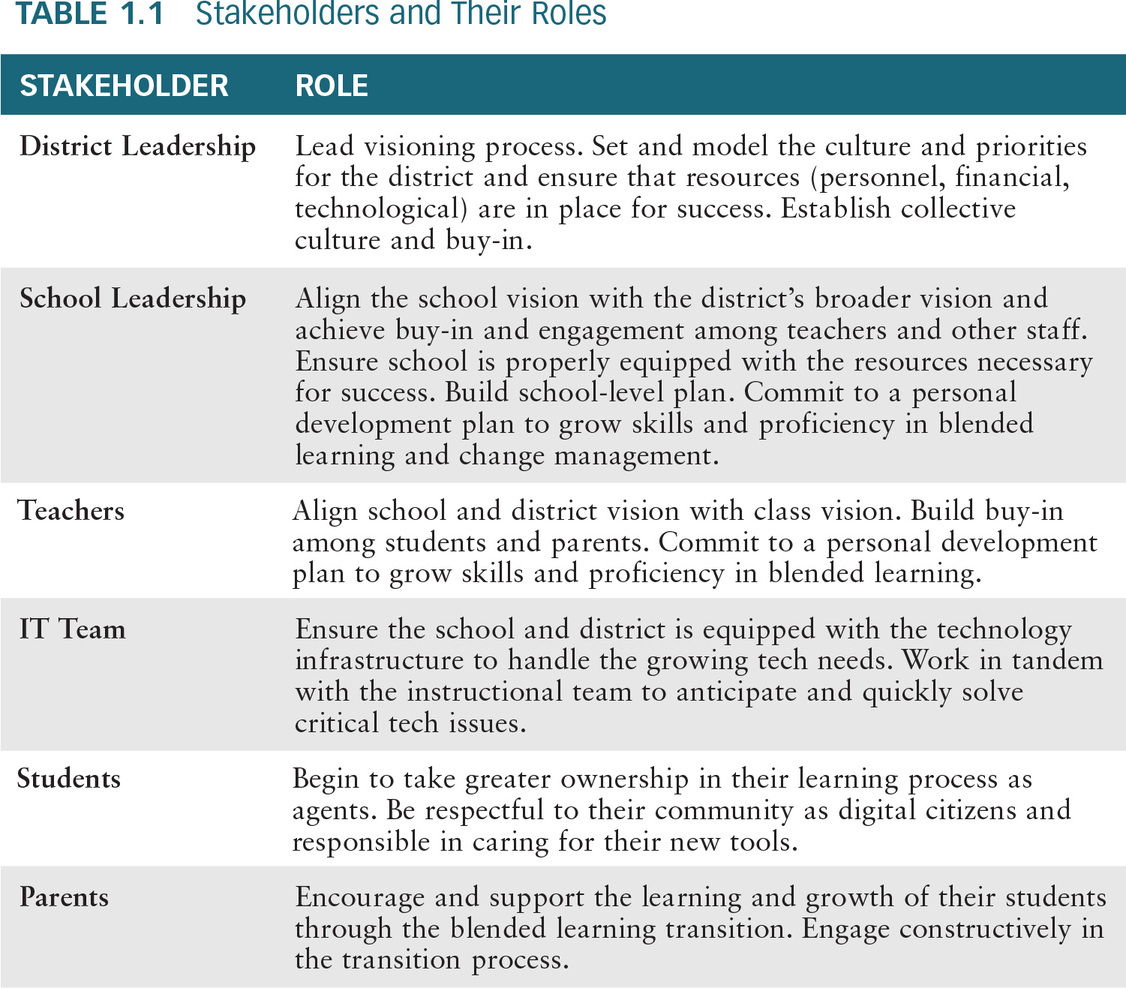

Providing each stakeholder with a voice and a role yields greater ownership and engagement. In a conversation with veteran superintendent Rick Miller, he explained that building culture is the most critical role of the superintendent and that “we have to give teachers opportunities and incentives to move toward a freer and more democratic environment. . . . We need to disrupt the culture of compliance and create one of professionalism and innovation” (Rick Miller, personal conversation, January 28, 2016). The most effective blended learning initiatives occur with all levels of stakeholder groups engaged and moving in concert. This alignment is achieved by building a cohesive vision—which is where the process starts. Table 1.1 explores the roles of stakeholder groups vital to the success of the blended learning transformation.

Where the World Is Going: Our Students Are Already There

We are at the moment in education when our schools can determine if they are Netflix or Blockbuster, Amazon or Borders, Samsung or Blackberry. In each of these cases, the successful organization saw that the entire world was changing and decided they were going to change to be ready for it. The failed organizations had, to their detriment, histories and inertias of people that were used to doing things the way they had always been done. This prevented them from shifting vision and culture at the time when it was most critical to their survival. Most realized their error too late while their successors were building nimble learning organizations ready and positioned for where the world was going, and even helped to shape it.

We now have much more than a glimpse of where education is going. Later in Chapter 12, we discuss how a teenager, Logan LaPlante, learned to “hack school.” He is not alone in his propensity toward hacking. It represents the desire for today’s learners to learn, create, and connect on their own terms, with their own interests, and by their own design. Author Will Richardson describes a conversation with Larry Rosenstock, founder of High Tech High, during a visit to the school: “Larry said, ‘We have to stop delivering the curriculum to kids. We have to start discovering it with them . . . especially now, when curriculum is everywhere’” (Richardson, 2012). Children today are communicating to us through the hours they spend designing their own worlds in Minecraft, through new languages they are building with emojis and symbols, by short-circuiting “no phone” policies through iMessage on their 1:1 school-provided devices. In some ways, a world of unique hackers is emerging and schools will need to learn how to be flexible enough to adapt and change to facilitate learning in a way that meets the hacker’s curious mind.

This is a big shift for most schools, but adopting the blended learning culture, practices, and approaches can be the bridge. Ironically, most schools were designed to help students learn, but they were not designed to learn themselves. The blended learning school is designed both to learn and facilitate learning. This ongoing organizational learning is critical as students are learning technology at younger ages, technology tools are evolving, and requisite skills for success in the marketplace are shifting.

K–12 education stands at its greatest inflection point—a collision course with irrelevance, or the opportunity for reinvention. By the actions and decisions it makes over the next few years, each district, each school, each teacher will choose whether to meet the needs of today’s learners or not.

Wrapping It Up

Austrian neurologist, psychiatrist, and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl stated, “Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.” In this era of rapid change, the stimuli are seemingly infinite. It can feel impossible to create the space described by Frankl in order to bring intention and true choice to the path forward. Schools are not exempt from the pitfalls that can result from failure to create this space when considering blended learning models. There have been many failed attempts as a result of hasty reactive decisions in the face of trends or pressure to improve.

At the same time, space does not mean long-term immobility or inertia. Instead, the space necessary to wisely choose the response to the frenetic stimuli of change is one of awareness of one’s landscape and stakeholders. In this space, the focus is on generating shared vision, developing a 360 degree perspective, encouraging stakeholder voice, and designing an iterative practice. By nurturing a positive blended learning culture and engaging stakeholders in actualizing the shared vision, leaders can more confidently take the first steps in their blended learning journeys.

Book Study Questions

- Think about where you are starting this journey. Based on the definition of blended learning, are there any blended learning practices already in place in your school? Discuss how blended learning differs from technology integration.

- To what extent are you able to currently personalize, help your students connect with other peers or teachers outside their classroom, enable students to have some control over “time, place, path, or pace,” and allow students to create using technology tools?

- What are the current organizational beliefs, values, and attitudes toward technology and blended learning within your school’s culture?

- Thinking about each stakeholder group’s shared attitudes, values, and beliefs: from your stakeholder vantage point, how could you influence other stakeholders to cultivate positive shared attitudes, values, and beliefs?

- Looking at this book’s table of Contents, what are you most excited to learn about? Discuss with your group a strategy for reading this book. Will you proceed in order or in a nonlinear fashion based on key interest points? Get excited to share this journey together!