Chapter 4 Preparing Teachers for Blended Instruction

Teaching and learning isn’t a one-way street. It is dynamic and flows both ways between student and teacher.

—Conor Brown, 10th Grade

Renowned researcher and learning scientist Dr. Arnetha F. Ball of Stanford University developed the Model of Generative Change for professional development based on the fundamental premise that regulations do not transform schools and teaching, but rather critical thinking, continuous learning with students and from students, and generativity in teachers’ thinking and practices transforms schools and teaching. She explains that teachers are not objects of change, they are agents of change. One of the greatest challenges facing schools in delivering successful blended learning instruction is properly and effectively preparing teachers. In blended instruction, teachers implement a host of new instructional skills, strategies, and technology tools. They must rethink their role in the classroom to transition from owners of information to facilitators of learning. This requires teachers to expand their view of where and how learning happens and what the term “classroom” even means. Technology means little if this shift does not occur. As such, effective professional development may be the most important aspect of achieving a successful blended learning initiative.

A recent study by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation found that only twenty-nine percent of teachers are highly satisfied with current professional development offerings, and a large majority of teachers do not believe that professional development is helping to prepare them for the changing nature of their jobs (Boston Counseling Group, 2014). Most professional development is wasting teachers’ valuable time.

Sadly, this is not news to any experienced educator. This problem is exacerbated in the professional development of blended learning because these new approaches and skills are not small shifts in instructional practice. We are asking teachers to make big leaps; to dramatically adjust their practices; to incorporate new tools; and reimagine what teaching and learning look like. Furthermore, this shift is not subject or grade specific. Every teacher needs this exposure so any solution needs to be scalable and affordable. This creates an immediate challenge because most districts do not have the internal capacity, expertise, nor funding to implement traditional solutions at scale. There are possibilities, however, and many districts are creatively overcoming these obstacles.

This chapter

- illustrates the best practices of highly effective professional development to prepare teachers for blended learning;

- provides guiding principles and a framework for planning and organizing effective blended learning professional development; and

- provides recommendations on how schools can differentiate and even personalize professional development to better meet the unique needs of teachers at various stages of blended learning readiness and proficiency.

As illustrated in the Blended Learning Roadmap, capacity building is an ongoing process with a goal of moving teachers from traditional lecturers to 21st-century facilitators.

What Works in Professional Development

Conclusive research into the best practices of professional development is very difficult to obtain because very few research studies have been conducted that are able to isolate specific variables of effectiveness. In a recent study of effective professional development for blended and 21st-century classrooms conducted by researchers at the Stanford Graduate School of Education, four key promising practices emerged:

- Duration and distribution: professional development should span longer periods of time (some studies indicating 14+ hours broken up into smaller segments)

- Coaching and collaboration: ongoing, iterative coaching and collaboration between teachers and coaches with observations, feedback, planning, and data analysis

- Simulation of practice: role-playing activities and active learning where teachers have opportunities to practice and apply learnings

- Technology: well-designed interactive digital learning experiences can be as effective as in-person methods and provide personalization for pace, content, and readiness. (Ball, 2015)

This research points to the need for schools to fundamentally rethink how most professional development is delivered in order to embed it into regular practice over time, include coaching and collaboration, and provide regular opportunities for teachers to simulate practice. This helps create not just a community of learning, but a community of learners. The finding that technology can serve as an effective modality of professional development is encouraging as it supports the overall blended approach while increasing opportunities for scale and cost management.

Guiding Principle of Blended Learning Professional Development #1: As the Student, So the Teacher (CHOMP)

Recently, the personalized learning movement has inundated the education world. While there is a significant push to creatively differentiate and personalize student-facing instruction, we are just starting to take up the same cause for teachers in a meaningful way. Educators, such as Randall Sampson, Jason Bretzman, Kenny Bosch, and others are helping to create new frameworks and approaches to personalize professional development, and are using Twitter to further the conversation at #PersonalizedPD. Redbird Advanced Learning partnered with Stanford University’s Graduate School of Education to create a personalized professional learning platform where teachers can learn at their own pace, choose their own path, and collaborate with other educators with similar learning objectives.

The goal of these efforts is to allow teachers to trade places with the blended learner in order to experience the benefits of these practices firsthand, thus becoming the 21st-century learners that we are asking them to help create. This is accomplished by infusing what we call the CHOMP framework—Collaboration, Hands-on learning, Ongoing experiences, Mindset shifts, and Personalization—into professional development.

Collaborate: Coach, and Create Meaningful Connections

In his book, The Innovator’s Mindset, George Couros says that the three most important words in education are relationships, relationships, relationships. This is especially critical in blended learning environments where connections are fundamental. Couros explains,

Rather than limiting educators’ initiative, and thereby students’ learning opportunities, let’s create environments of competitive collaboration, where educators at all levels push and help one another to become better. . . . We must build and strengthen relationships with (and between) our educators so that every individual sees him or herself as an integral part of a larger whole. (Couros, 2015, Kindle Location 1048 of 3535)

If you ask most teachers how they prefer to learn, their first response is from other teachers. This is an understanding that organizations like Edcamp are validating and building on by providing vehicles where teachers can share and discuss challenges and ideas that are important to them. Edcamp started in May 2010, and since then there are over 1,000 edcamps in all 50 states and across 26 continents. Other models are emerging, such as the “Pineapple Chart” method explained by Mark Barnes and Jennifer Gonzalez in their book Hacking Education, “a systematic way to put a ‘welcome mat’ out for all classrooms, a central message board that lets other teachers know that you’re doing something worth watching today, and if they’d like to come by, your door is open” (Barnes & Gonzalez, 2015), and the Teachers’ Guild by Ideo, a virtual professional community of teachers crowdsourcing education design solutions, found online at www.teachersguild.org. The rapid pace of change and innovation in blended learning further necessitates connection as teachers can learn of new approaches, tools, and strategies from other teachers all the time in real time. Participating in twitter chats like #satchat, #sunchat, #Nt2t (New teachers to Twitter), and #edchat held at scheduled times, or as ongoing conversations can help build your professional learning network (PLN).

The most effective blended learning districts and schools infuse coaching from experts and more experienced blended teachers on a regular basis to help ensure the development of best practices. Tustin Unified School District in California expanded the blended learning capacity of their teachers districtwide by using mentoring exponentially. They started with a group of two teachers who became blended learning experts. Then, each expert coached eight to twelve teachers each year who became fellows. Now in their third year, representing almost half of the teachers in the district, over four hundred teachers have been coached intensely in blended learning. This is a powerful application of professional learning communities (PLCs) and mentor teachers and a great way to achieve the right balance of peer-to-peer and peer-to-expert support.

Figure 4.1 The CHOMP Framework to Professional Development

Links to the Classroom: Help Students Connect

Students find inspiration through connectivity. In fact, social interaction is arguably the greatest motivator driving adolescents. Beyond motivating students, teachers also gain a “sandbox” to model positive and purposeful use of social media when they incorporate connectivity tools into the classroom. Edutopia’s A Guidebook for Social Media in the Classroom, by Vicki Davis, presents several ideas on how to help students connect, and precautions that teachers should take to ensure the sandbox is safe and supervised.

Vignette: Kerry Gallagher, Blended Learning Teacher and Digital Learning Specialist, Boston, Massachusetts (@kerryhawk02)

As a teacher hungry for a constant source of new ideas to keep my students’ learning fresh, I joined a district cohort of fellow educators. We wrote weekly reflections about how we were implementing the instructional practices we learned together. Those write-ups were posted to a closed online course. Only participants had access to it.

After just one post, it felt like something was missing. I worked hard on my reflections. When I’d had a success, I was excited to share it. When I fumbled, I wanted to seek advice from my colleagues. My small cohort was a responsive group, but I knew I could get more feedback if I shared my reflections more widely. I was hungry. More feedback was better.

And so, my blog was born. I started sharing my posts on Twitter and Facebook. My educator friends, personal friends, and family were reading, commenting, and asking me questions about my work. Every interaction that came from those posts gave me new perspectives and new ideas on how teaching and learning could look in my classroom.

As I shared and perused Twitter, I noticed Twitter chats—moderated conversations among groups that use a hashtag to follow one another—and I was hooked. I was part of live conversations with teachers from all over the world. We talked about project-based learning, effective technology integration, and a lot more.

Some of my fellow connected educators and I read one another’s work and talked regularly. A few of us talked so often we planned in-person meetups at conferences. I’ve even co-presented with a couple of them. In one case we had never met in person before the day we presented together!

I can happily say that I no longer wait for professional development opportunities to come my way. When they do, it is great. But, when I’m ready to remix a project and bring new perspective to a topic, I have a whole network of people and resources at my fingertips.

Hands-On Learning

Traditional “sit and get” professional development no longer meets the mark. The days of teachers marching into a lecture hall, auditorium, or cafeteria to listen to a presenter for three hours is not scalable, affordable, or effective. Teachers should be actively engaged in the learning process. An easy way to achieve this is through “tinkering” style sessions where teachers are given times to discover and play with new technology tools in groups or independently. Teachers can also practice facilitating a blended learning lesson with other teachers playing the role of the students. This increases best practices sharing and collective innovation. These learner-driven approaches generate excitement, deeper learning, and multiple opportunities for “aha” moments. Another great approach to engage teachers more actively in professional learning is through gamification, or incorporating gaming elements, such as points, competition, badges, and so forth into learning. The Redbird Professional Learning Platform is an example of gamified professional development as teachers obtain points and badges for completion of projects and activities, and compete to raise their standing on the leaderboard. These types of approaches help to increase the fun of professional development while giving teachers a glimpse into the “gamer” world of many of their students.

Ongoing Learning

Schools must have a structure and environment of continued learning. The role of the leader should be to build this environment and structure. This structure should be ongoing and consistent. It should be a regular part of the week and possibly even the day. Sustainability is achieved when the community becomes a true learning community across all levels. School leadership, teachers, staff, and students should all view themselves as continuous learners. In a world of competing priorities, professional learning is often viewed as important, but not urgent. This is a real danger. When teachers are confronted with their daily schedule and numerous competing priorities, professional learning tends to take a back seat. The commitment must be made by the whole community to prioritize professional learning. This means making the space and time available for teachers to continue their learning.

Building the Structure of Continuous Learning at William Tilden Middle School, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Brian Johnson, Principal of Tilden Middle School, is determined to transform his school into the model blended learning school in Philadelphia. And he is on his way. First, Brian has established himself as the chief learner of his school. He takes advantage of every possible opportunity to get smart by attending conferences, connecting with other leaders across the country, and devouring articles and books on school transformation and blended learning. He recognizes that he is also modeling and setting the stage for his leadership team, teachers, and students. Brian is immersing his teachers in the same sort of learning that they should be replicate for their students. Professional development is inquiry-based and often delivered in station rotation models. He took the same risks with the teachers that they are taking in their classrooms with students and brought them into his planning and iteration process. They witnessed some of the challenges and mistakes he made in the transition process.

Brian is using tools like the Redbird Professional Learning Platform to augment the learning process for staff where they can drive more of their own development in synchronous and asynchronous ways. This is a 3-year growth sequence for the teachers and team at Tilden Middle. Over the course of this time, teachers will have their own personalized professional development paths as these professional learning supports are embedded into the fabric of the school. Brian sought advice from a professional scheduler to help him rethink the school day. He has found the time for teachers to have structured professional development three times per week after school. On Tuesday, they focus on social emotional learning, on Wednesday, blended learning or another focused topic, and Thursday, data review and academic growth. One of Brian’s teachers has already decided to leap ahead and begin new courses in the professional learning platform on GAFE (Google Apps for Education) and Project-based learning. “This is the beauty of personalized learning,” Brian says, “people have the opportunity of autonomy, to build new things, work at their pace, and create.”

Mindset Shifts: Start With the Why Not the What

Often professional development for teachers launches immediately into a new skill, practice, or product without first addressing why it is important or explaining the purpose behind it. This approach undermines the importance of the learner actually being engaged in the process. If a teacher is not clear about the why of blended learning, it will be much more difficult to create the desire or willingness to actually try the practice in the classroom. Simon Sinek’s research points to the effectiveness of inspired organizations in clearly communicating their purpose and mission (Sinek, 2009). The “why” is least effective when it is a top-down mandate or tied to punitive measures. It is most effective when teachers actually see the value in how this instructional practice will have a benefit in the classroom and to the learners. This can be achieved through leveraging current blended learning champions and leaders in the school in teacher-led sessions, coaching, and peer-to-peer classroom visits and observations. If the school does not currently have good models of blended learning, it may be a good idea to send teachers out to conferences or other schools to see and learn about the benefits. Lastly, even just starting professional learning sessions with a conversation and discussion of the “why” is of tremendous value.

Personalize Choice, Differentiation, Pace, and Skills

It is critical that professional learning experiences acknowledge that teachers are at different starting points, have different needs, and learn different ways. If a professional learning experience does not allow for this personalization, it is failing in two ways: 1) it is not providing teachers what they need to build their blended practice, and 2) it is not modeling for teachers how they should be rethinking their own classrooms for their students. There are a number of ways in which professional learning can be personalized, and not surprisingly they resemble how learning can be personalized for students: by pace, path, place, and modality. Later in this chapter, we discuss in much greater detail how schools and districts can differentiate professional development for different types of teachers.

Links to the Classroom: What Are Your Strengths Now?

In new initiatives it is sometimes easy to feel that everything must change and fast. Be careful with this feeling as there are many practices that you are currently implementing that are working very well. Identify some of these strong practices, even taking the time to ask students what they currently love about the classroom learning experiences. In some cases, teachers may strategically decide not to change something dear to students, and in other cases to build it out through blended practices. This method of starting with strengths also increases the sustainability of the initiative.

Guiding Principle of Blended Learning Professional Development #2: Differentiate to Cross the Chasm

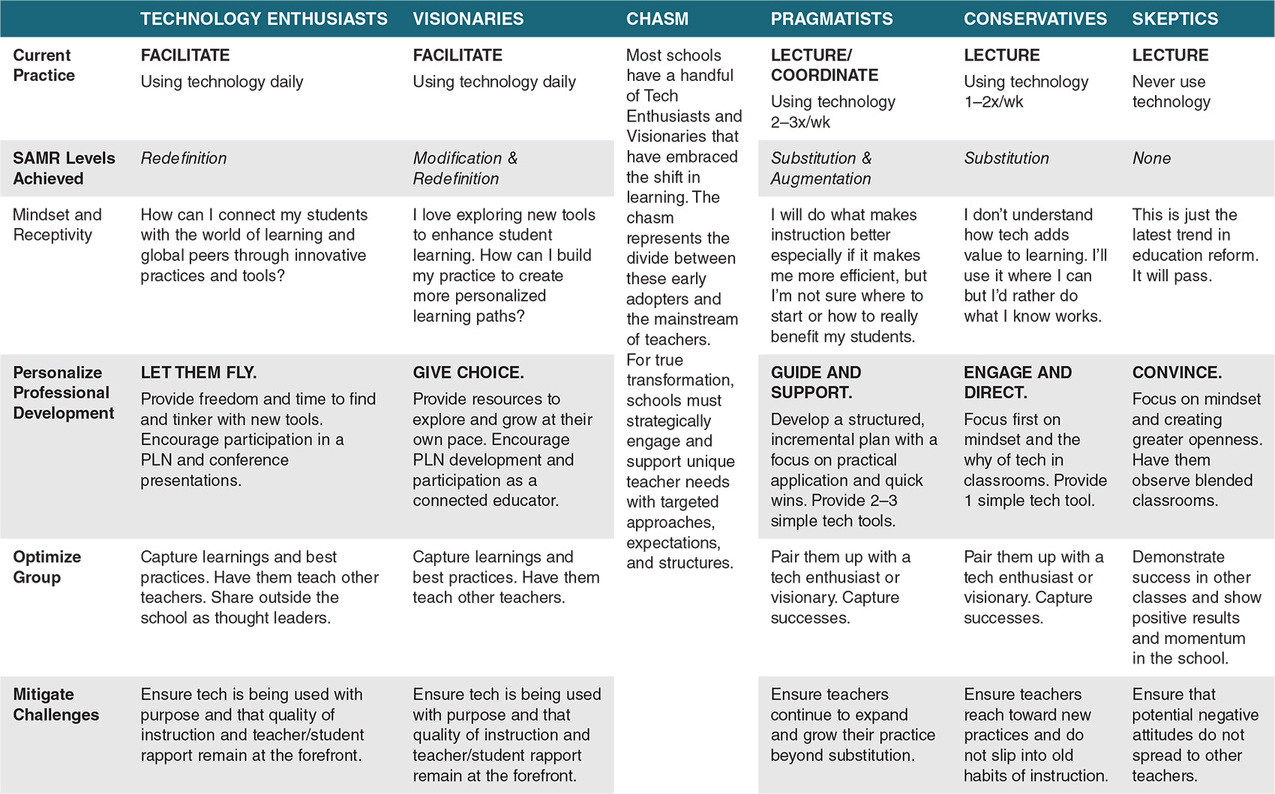

As you walk through the halls of most schools, one thing becomes immediately evident. A few classrooms have adopted blended learning practices and are zooming with technology integration while other classrooms (usually the majority) remain lecture oriented and more teacher-centered. This is the chasm. The Tipping Point by Malcolm Gladwell (2006) refers to the point at which an idea, concept, technology, or tool extends from being niche to part of the mainstream culture. In almost every adoption of new technology—from the new iPhone to the hoverboard—there is a progression of adoption. The bell curve pictured in Figure 4.2 largely holds true for the adoption of blended learning in schools. In most schools today, each of these groups of teachers exists. The chasm that we refer to is the divide between the early adopters and mainstream teachers.

Bridging the Gap/The Tipping Point

It is vital for schools to think about widespread transformation. In order to do this, we have to bridge the chasm to include adoption of the pragmatists and the conservatives. Take for example the wearable technology Google Glass. There was a small subset of people who jumped on board immediately. These are the tech enthusiasts and visionaries. They are willing to take risks with new models, products, and approaches. Many of them found value in being able to search news items right from their eyewear, get directions on the go, and maintain constant contact with information that’s only a blink away. The challenge with Google Glass was that it never spread to reach the pragmatists and conservatives. The benefit never became clear, affordable, and usable enough for the mainstream, so Google Glass has largely faded out.

By contrast, when smartphones were first introduced, many people wondered why they would need a computer in their pocket; now nearly everyone who can afford a smartphone has one. Pragmatists adopted smartphones when they realized the added benefit in being able to pull directions, or easily check in online for a flight. Conservatives adopted smartphones when flip phones were no longer available or when they could no longer find the proper accessories. Eventually virtually everyone adopted the smartphone, but at different times and for different reasons.

This progression also holds true as it relates to blended learning adoption in schools. There are usually a few teachers in each school who are the tech enthusiasts and visionaries. They will try new technology tools and attempt to implement blended learning regardless of what the school does. Catlin Tucker’s school was not doing any blended learning or tech integration, but she chose to make it work in her own low-tech classroom. She would be considered a visionary. There are many teachers like her who are pushing to make this transition regardless of what is happening in their school.

Figure 4.3 Differentiated Approaches to Professional Development

Courtesy of Redbird Advanced Learning.

The mainstream of teachers tend to be more pragmatic or conservative in their approach to blended learning. Pragmatists want to see the tangible benefit and how it will make their lives easier, make them more efficient, or allow them to better engage students. Pragmatists are waiting until it is easier to grade student papers and submit grades online using the new Learning Management System compared to doing these activities on paper. Conservatives are waiting until paper-based systems are no longer an option. These groups may be trying a few things here and there, but they are largely waiting for the tipping point. If a school leader or district is trying to achieve large scale reform, these later adopters must be converted and approached differently. The good news . . . now, we can leverage technology in professional development to make this possible.

Figure 4.3 dives into the different groups and how school and district leadership can think about differentiating professional development across key groups of teachers and engaging them in the school’s overall learning process.

Wrapping It Up

Most schools seeking to transition to a more blended instructional model to some degree are experiencing a wide distribution of adoption among teachers. The most successful schools and districts recognize these distinctions among teacher groups and provide professional development opportunities accordingly. In the planning of professional development, we highly recommend that the starting point is holistic in nature with broad goals and vision for the teaching and learning that we want to occur in the classroom. This will vary from district to district and even from school to school; however, this vision will generate the roadmap necessary for the plan for professional development to emerge.

By reiterating the guiding principles of blended learning professional development—

- As the student, so the teacher: building professional development experiences that reflect the practices and tenets of a blended and 21st-century classroom; and

- Differentiating to cross the chasm: establishing opportunities for teachers to learn in more personalized forms;

—schools will integrate and create a community of learning and learners fostering sustaining practice, and a higher quality of teaching and learning, ultimately leading to achievement gains among students.

Book Study Questions

- What is your school or district’s broader vision for the teaching and learning experience you want to create?

- What are the skills that will be required for teachers to achieve this vision in the classroom?

- How will you create a range of professional development opportunities and paths to better differentiate and ultimately personalize professional development?

- How will you facilitate teachers engaging actively in their own professional development?

- How will you measure the success of your professional development initiatives?