Introduction

Barbara Cantalupo and Lori Harrison-Kahan

My purpose in writing . . . is to give genuine pleasure to my readers. But one must not place heart before art. I try to paint the subject as truthfully as possible in the colors in which I see it myself mentally. Truth-telling should be an author’s religion. It is mine, and because of it I have caused considerable discussion among my own people. But all that I have written has been said in the spirit of love—the love that has the courage to point out a fault in its object.

—Emma Wolf, 1901

Making available an important and influential novel by Emma Wolf (1865–1932), this edition of Heirs of Yesterday (1900) fills a significant gap in American literary studies, Jewish studies, and women’s writing. Although Wolf has received little notice by literary scholars and historians, the Jewish press in her time bestowed attention and praise on the work of this San Francisco writer, who, in 1900 at age 35, was publishing her fourth novel.1 In its front-page review of Heirs of Yesterday, the Jewish Messenger labeled Wolf “one of the rare exceptions to the general rule” in the recent explosion of Jewish fiction. “She is expressly omitted from the category of Jewish novelists who exploit their religion and special class of people and call the result literature,” the reviewer stated.2 During the late nineteenth to early twentieth century, a period of Jewish American literary history dominated by the genre of the New York–centric ghetto tale and by Yiddish-speaking, Eastern European immigrant writers, Wolf’s Heirs of Yesterday offered a very different representation of Jewish life in the United States. Set far from the sweatshops and tenements of the New York ghetto, the novel takes place in the Reform Jewish community of San Francisco’s Pacific Heights. Its central characters, physician Philip May and pianist Jean Willard, are not striving immigrants in the process of learning English and becoming American. Instead, they are cultured, middle-class, native-born Americans who interact socially and professionally with their gentile peers. Overturning readers’ expectations of Jewish American identity and Jewish fiction, as well as complicating well-engrained narratives about US immigration and religious minorities, this edition of Heirs of Yesterday brings a forgotten novel to the attention of twenty-first century readers and scholars. Our introduction expands upon the current scholarship on Wolf, offering biographical background based on new research findings. It also explores key literary, historical, and religious contexts for Heirs of Yesterday, thereby opening avenues for further research on a writer who has been called the “mother of American Jewish fiction.”3

“A Jewish Girlhood in Old San Francisco”: Emma Wolf’s Life and Times

On June 15, 1865, Simon and Annette (Levy) Wolf, Jewish immigrants from Alsace who had settled in the San Francisco Bay Area, welcomed a new daughter. The fourth of eleven children, Emma was to grow up in a family dominated by girls. The Wolfs’ first child was a son, Morris, who was born in 1858 when Annette was twenty years old but died at age four, before Emma was born. Emma joined her older sisters, Florence and Celestine, who were born in 1861 and 1862, respectively. A year after Emma’s birth, in May 1866, another son, Julius, arrived. He was followed by six more girls: Alice in 1869, Isabel in 1870, Mildred in 1873, May in 1875, Estelle in 1876, and Esther in 1879. On September 12, 1878, while Annette was pregnant with Esther, Simon Wolf died unexpectedly on the way home from a routine business trip, leaving his wife to raise ten children on her own. Thirteen-year-old Emma was profoundly affected by the sudden loss of her father; as an adult, she continued to revisit this loss in her fiction (including in Heirs of Yesterday), where the death of a loving paternal figure bears symbolic weight and marks a turn in her protagonists’ fates.

Simon Wolf’s financial success as a businessman meant that the family, with some economizing and despite its size, had the resources to maintain a comfortable middle-class lifestyle. But at a time when most women of their class would not have sought employment, even prior to marriage, their father’s early death impelled Emma and several of her sisters to work, albeit in suitable jobs for women of their social standing. Two of Emma’s sisters, Isabel and May, were employed as schoolteachers, while Alice found work as a private secretary. Like Emma, Alice was also a writer, publishing short stories as well as one novel, A House of Cards, in 1896. Most of the Wolf sisters married out of the wage-earning labor force. Alice, for instance, discontinued her writing career following her marriage to her employer, Colonel William MacDonald, in 1898. Emma, however, remained single, due in part to a congenital physical disability, possibly exacerbated by polio.

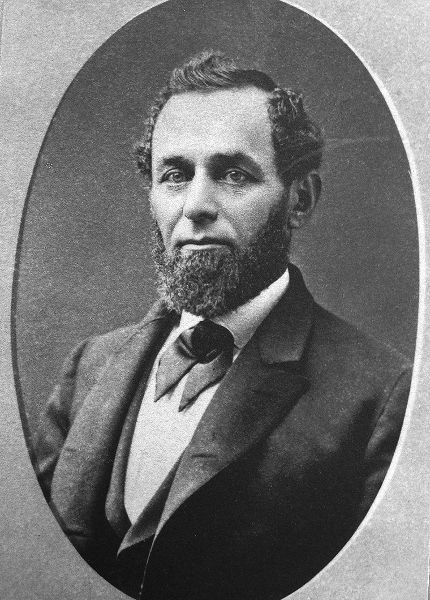

Simon Wolf, Emma’s father.

Courtesy of Donald Auslen.

Emma’s status as a single woman and her limited mobility freed her from domestic duties and allowed her to devote her time and energy to writing. While remaining involved in the lives of her siblings and their children, Emma continued her lucrative career as a writer until age fifty-one, publishing her last and longest novel, Fulfillment: A California Novel, with New York publisher Henry Holt and Company in 1916. As a review of Fulfillment in the Overland Monthly makes clear, Wolf’s fiction had not faltered in style or content: “In the locale, San Francisco, where she lives in real life, the author has woven a web of interesting temperaments in such a manner that the ensuing developments grips [sic] the reader to the last page. . . . the story is told crisply and with artistic restraint.”4 Given such praise from reviewers for the quality of her late work, it is likely that Wolf’s retirement from writing and public life was driven by ill health. When she died in 1932, her obituary in the San Francisco Chronicle noted that she had spent the last fifteen years of her life “virtually confined to her room.”5

Emma Wolf was born at a moment in US history when the Civil War had just come to an end, ushering in a new order with the abolition of slavery in the Southern states. Like the rest of the nation, which was undergoing industrialization and modernization, the West was experiencing rapid development, and Wolf’s hometown of San Francisco was well on its way to becoming a cosmopolitan city, a destination for migrants from around the world. The seeds of the coming era’s progressive reforms were beginning to have an impact upon women, many of whom were demanding rights of citizenship and seeking alternatives to conventional lives of marriage and domesticity. The end of the nineteenth century would prove an especially fertile period for women writers, with the expanded growth of periodical culture and an ever-increasing audience of middle-class female readers. By the time Emma reached adulthood, American Jewish life was also undergoing radical change, as the Reform movement took hold in cities across the nation and middle-class Jewish women formed communal organizations at the local and national levels. The influx of new immigrants led to a dramatic increase in the country’s Jewish population. Hailing from Eastern European countries such as Russia, Austria-Hungary, and Romania, these new immigrants changed the face of American Jewry, reshaping and supplanting religious and secular forms of Jewishness established by previous immigrants from France and Germany and by Sephardic Jews who dated their lineage in the United States back to the colonial era.

Part of a wave of Jewish immigration from Western and central Europe, Wolf’s parents immigrated to the United States in the mid-nineteenth century, fleeing religious prejudice in Alsace-Lorraine, a French territory bordering on Germany. Although the French Revolution had officially “emancipated” Jews in France in the late eighteenth century, promising equality and opportunity for all, “the situation of the Jews in Alsace was by no means comfortable.” As historian Paula Hyman has documented, “Anti-Jewish hostility,” including “anti-Jewish remarks by government officials or in public courtroom proceedings[,] . . . remained a regular feature of Alsatian life into the 1860s.”6 Reports from the Bay Area informed Alsace’s marginalized Jewish population that Jews were an integral part of San Francisco’s cultural and business communities and that economic opportunities would be available upon their arrival in California. Ava Kahn describes Jewish immigration to the West Coast “as part of a chain or family migration [in which] families and friends from the same homelands settled together in the Golden State.”7 For Alsatian Jewish immigrants like the Wolfs, settling with friends and families meant they could live in proximity to other Jews; just as importantly, however, it allowed them to be part of a community in which they could continue to speak French and celebrate their French culture.8

Jews were among the pioneering settlers in the Bay Area during the Gold Rush, and their businesses helped grow and sustain the city of San Francisco. What began as a “population of 462 people ‘living in tents, shanties and adobe huts’ in 1847” became, in three years’ time, a city of 21,000 people.9 Marc Dollinger describes the historical conditions that enabled Jewish integration into the life of the developing city: “The rapid population growth, lack of preexisting Anglo power structure, and trade skills enjoyed by Jewish arrivals combined to create unprecedented Jewish social mobility. . . . San Francisco Jews counted the ‘City by the Bay’ as one of this nation’s most friendly. Jewish residents tended to resist the temptation to live in cloistered Jewish enclaves, enjoying instead the opportunity to live and socialize among the larger non-Jewish community.”10 A firsthand account by Daniel Levy, a friend of the Wolf family and a lay leader at Congregation Emanu-El, confirms Dollinger’s description. In a letter to the editor of the French journal Archives Israélites, dated October 30, 1855, Levy relates: “Among all the areas of the world, California is possibly the one in which the Jews are most widely dispersed. . . . [In San Francisco] the French, for the most part from Alsace or Lorraine, do not actually form a real group and are integrated into the mass of their nearest European neighbors. . . . [Jews] of San Francisco are estimated at more than three thousand. There may be as many as that scattered about in the interior.”11 This number represented about 9 percent of the population at that time, yet despite that small percentage, Jews had a strong influence on the city’s commercial well-being. For example, in 1858 when the much-awaited day that marked the arrival of steamships bringing goods to San Francisco Bay fell on Yom Kippur, the city postponed “Steamer Day” so that “Jews were not forced to choose between commerce and their faith.”12 As San Francisco historians have noted, the “first generation of Jews in the Bay City” were granted such regard because they were “twice as likely as non-Jews to remain in the area permanently . . . [and] were a stabilizing, civilizing influence.”13

In the mid-nineteenth century, Jews began to establish secular and religious roots in the Bay Area, founding philanthropic organizations like the First Hebrew Benevolent Society and the Eureka Benevolent Society and congregations such as Emanu-El and Sherith Israel. As early as 1856, two Jews were nominated for public office in San Francisco and a Jewish judge held a seat on the California Supreme Court.14 Wolf herself described how Bay Area society was relatively free of caste distinctions in a profile of San Francisco that appeared as part of the series “Social Life in American Cities” in The Delineator:

For many years a common hazard and uncertainty of fortune threw down any possible social barriers and prevented the formation of anything suggesting caste. It was in these young days that the seed was sown for that free-and-easy, hail-fellow well-met spirit which characterizes the San Franciscan of to-day. The zest of adventure or the necessity of venture had brought with it a heterogenous agglomeration of all sorts and conditions of men, which accounts for a certain Bohemian tone and mellow worldliness not generally possessed by cities of such recent growth.15

The acceptance that Jews found in San Francisco during Wolf’s lifetime was clearly evident with the election in 1895 of Adolph Sutro, a German American Jew, as mayor. As Edward Zerin explains, “Because Jews were pioneers among pioneers [in the West,] there was little overt anti-Semitism. . . . [T]hey were welcomed into the social life of the community, winning the respect of their fellow citizens.”16

Yet Wolf acknowledged the tentative nature of such social acceptance. In her article in The Delineator, she went on to observe that as “order slowly grew out of chaos . . . society began to evolve with the usual demarcations and distinctions of latter-day living.”17 Heirs of Yesterday similarly reveals how ethno-racial and religious prejudices undergirded the city’s social hierarchy by the late nineteenth century. While Wolf depicts Gilded Age San Francisco as a fairly inclusive environment, she does not shy away from exposing some of the subtler effects of individual and institutional anti-Semitism. In alluding to the differences between Philip May’s experiences in New England and on the West Coast, however, the novel suggests that San Francisco was, comparatively, a haven for members of the minority religion, a place where they could be integrated into the social, economic, political, and cultural life of the city while openly identifying as Jews.

Although New York has now eclipsed all other cities as the locus of Jewish life in the United States, in the nineteenth century, San Francisco was well on its way to becoming the Jewish diaspora’s West Coast counterpart. In her introduction to Jewish Voices from the Gold Rush: A Documentary History, 1849–1880, Ava Kahn details the vibrancy of Jewish life in San Francisco:

San Francisco became the center of Jewish life, as it did of California life. By the 1870s, a distant, drowsy California outpost had become “the City,” a center of Jewish journalism and publication second only to New York City, as well as home to debate and literary societies, clubs, libraries, an orphan home, and a host of fraternal and benevolent organizations. . . . [S]ynagogue leaders in California became more independent than their eastern counterparts and had no inhibitions about speaking up or standing out. At times the community was nonconformist in its practices. Such anomalies as the recitation of the Kaddish, or mourner’s prayer, in tribute to the memory of an admired non-Jew reflected an ability to synthesize Jewish traditions with a new, American way of life. . . . They joined with coreligionists to form the Concordia and other social clubs, to found literary and debating societies, and to establish B’nai B’rith and Kesher Shel Barzel lodges, among other fraternal organizations. In these associations, small merchants could meet independent of the religious and family constraints of the synagogue.18

Kahn’s description affirms a vision of San Francisco not only as a welcoming environment for Jews but also as a place of “nonconformist” innovation where a synthesis between American and Jewish life could be forged, opening the way for new formulations of American Jewishness as a distinct cultural and religious identity. Wolf’s congregation, Emanu-El, founded as an Orthodox synagogue in 1850, soon changed course and “endorsed . . . resolutions” spearheaded by leading Reform rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, who initiated the creation of a uniquely American prayer book, Minhag America, at the Cleveland Conference of 1855; Wise’s goal was to unify American Jews, who adhered to different religious customs due to their diverse national backgrounds.19 In his role as leader and teacher at Emanu-El, Daniel Levy “favored sweeping reforms for the Jews of the West [and concluded that] ‘the future belongs to Reform’” Judaism—a vision espoused by the characters of Jean and Daniel Willard in Heirs of Yesterday.20 As Shari Rabin asserts, Jews on the frontier created flexible and adaptive versions of Judaism and Jewishness in which religion became “a mobile assemblage of resources for living.”21

Scholars of California Jewish history have emphasized the symbolic nature of the West Coast in American Jewish life of the period. Moses Rischin characterizes California as a place that “more than any other appeared from the outset to project—as seen from a Jewish perspective—a sense of America at its most promising, open, and refreshing.”22 The city of San Francisco embodied this openness, allowing “Jews of all origins and persuasions . . . to enjoy the freedom to pursue varied opportunities and lead vibrant lives, to assimilate the best of modern America and the modern world, and to satisfy their special needs as Jews.”23 The majestic Emanu-El, which originated as a small congregation of traders and merchants during the Gold Rush of 1849, stood as a visible testament to all that San Francisco represented for the Jewish residents who had claimed the West Coast city as home. “Like no other building in the nation, the region’s cathedral synagogue dramatically came to symbolize the freedom, equality, openness, and fraternity of America and of the West for Jews and others,” Rischin observes of the centrally located temple whose twin domed towers were a visible feature of the city’s skyline.24 Temple Emanu-El projected a vision of San Francisco Jewry as “progressive” and “open-minded,” according to Judith Pinnolis; as early as the 1880s, for instance, the congregation invited a woman vocalist to serve as cantor.25 If Temple Emanu-El signaled the emergence of modern, urban Jewish society in the new West, the building’s destruction in the 1906 earthquake and fire was a shock and temporary setback for the community, although the temple was subsequently rebuilt and remains an important landmark today. Along with Harriet Lane Levy’s memoir 920 O’Farrell Street: A Jewish Girlhood in Old San Francisco (1947), Wolf’s Heirs of Yesterday is the rare creative work that captures the vitality of Jewish life in Gilded Age San Francisco. Published six years before the earthquake, Heirs of Yesterday stands as a lasting monument to a time and place in American Jewish history that are often overlooked.

As members of Emanu-El, the Wolfs were at the center of cosmopolitan Jewish life in Old San Francisco. But when Annette Levy and Simon Wolf first made their separate ways to the Bay Area, San Francisco was still a rough and rowdy Gold Rush town with a small Jewish population. Born in 1838 in Alsace-Lorraine, Annette grew up in San Francisco, arriving in the city at the age of five with her parents, Jonas and Amelie Levy. Simon Wolf, sixteen years Annette’s senior, was also born in Alsace, in 1822, and spent his childhood and early adulthood there before immigrating to the United States. He arrived in New York on January 9, 1851, at the age of twenty-nine, before migrating westward. Several years later, Simon was followed by his sister, Clemence Wolf (1839–1924), who landed in New York before moving to San Francisco to be near her brother. By then, Simon and Annette were married, and Simon arranged for his sister to live with his in-laws. Although the exact story of how Annette and Simon met is not known, Emma’s parents were part of a tight-knit French-Jewish immigrant community where marriages remained endogamous. For the next generation, however, that practice was to change, as evidenced by their daughter Alice’s marriage to the gentile Colonel MacDonald in 1898. Though Emma did not wed, her fiction suggests that she was a careful observer of the courtships and marriages that took place around her. In all of her novels, including Heirs of Yesterday, Wolf makes symbolic use of the marriage plot, with debates over interfaith unions providing the subject matter for her first novel, Other Things Being Equal, in 1892.

In addition to marrying those who shared their faith and background, pioneers like Simon Wolf formed business partnerships with fellow Jews, and these familial and professional worlds often intersected. Simon established a number of general merchandise stores throughout Contra Costa County, working with Jewish partners, including his brother-in-law, Mark Kline (1835–1900), another Alsatian immigrant, who married his sister, Clemence, in 1862. In 1865, the year of Emma’s birth, the brothers-in-law opened a store called Wolf & Kline Merchandise in the mining town of Somersville, now one of many unpopulated ghost towns, remnants of the Gold Rush past. With other businesses in Alamo, Danville, Antioch, Point of Timber, and Brentwood, Simon spent his week traveling from store to store to visit his partners, relying on three modes of transportation (ferry, train, and horse and buggy) and returning to his family in San Francisco on the weekends. In the mid-1860s, he also owned and operated a cigar and tobacco shop in the Russ House in San Francisco, the city’s first three-story grand hotel. By the 1870s he had opened an office for the operation of his Contra Costa stores in San Francisco—an indication that his various business ventures were consistently profitable.26

As part of a Jewish mercantile class that profited from California’s mining boom, the Wolfs lived a comfortable middle-class existence in San Francisco’s fashionable neighborhoods. They employed servants, Irish immigrant women and a Chinese cook, to help care for the large family, including Annette’s parents, who lived with the Wolfs during Emma’s childhood. The deaths of Emma’s maternal grandparents—Amelie passed away when Emma was seven and Jonas when she was eleven—were followed by the unexpected death of her father at age fifty-six. Simon Wolf’s death was also a loss for the larger Bay Area community. “Mr. WOLF during 20 odd years that he was engaged in business in our county, and at times doing a large trade, proved himself an honest, conscientious, upright man and citizen,” read the notice of his death in the Weekly Antioch Ledger. “Always kind and obliging, he had the respect and esteem of an extended circle of friends and acquaintances. To his family he was always kind and affectionate.”27 This description could easily be applied to the Jewish paternal figures in Wolf’s novels, self-made family men like Jules Levice in Other Things Being Equal and Joseph May in Heirs of Yesterday, whose sacrifices and hard work eased the way for their children.

Following her husband’s death, Annette did not remarry and raised her ten children with the help of live-in servants. Although relatively secure due to Simon’s business investments, the family did experience the constraints of a limited income and the fear of economic vulnerability, especially during the panic of 1893 and the subsequent depression. In Wolf’s fiction, monetary concerns emerge even among members of the upper class and upper-middle class, and her bourgeois female characters remain aware of the way their economic circumstances confer a privileged status. After Simon’s death, the Wolf family moved often, partly to accommodate changes in the family’s size and partly due to financial needs. Nonetheless, most of their homes were in what are now known as the Pacific Heights, Presidio Heights, and Laurel Heights neighborhoods of San Francisco—all beautiful locales overlooking the San Francisco Bay. As an adult and a successful author, Emma contributed to the family income and continued to live with her mother and some of her siblings. In 1898, for instance, 2105 Pine Street in Pacific Heights was home to Emma, her mother, three of her unmarried sisters, and her brother, Julius (1866–1923), a businessman who became president of the San Francisco Grain Exchange. In 1901, the family moved to Presidio Heights, today still one of the most prosperous neighborhoods in the city. The Wolf sisters also vacationed at summer resorts, such as the Hotel Ben Lomond in the Santa Cruz mountains, likely the inspiration for some of the natural settings in which Wolf’s characters take temporary reprieve from urban living.28

Wolf family portrait.

Courtesy of Donald Auslen.

Emma and her sisters attended the California public schools, completing their education at San Francisco Girls’ High School, which was founded in 1864. In 1882, at the age of seventeen, Emma graduated from Girls’ High School, which meant that her time there coincided with the principalship of John Swett, an educational reformer who has been described as the “Horace Mann of California.”29 As principal of the school from 1876 to 1889, Swett imposed high standards upon the curriculum with the goal of professionalizing teaching for the current instructors and for the female graduates, more than half of whom would end up in charge of their own classrooms. By graduation, the girls would have obtained

the ability to read and spell well; a fair knowledge of English grammar; some knowledge of the meaning and use of words, of etymology and synonyms; a fair knowledge of algebra and geometry; some knowledge of physical and political geography; a general outline of the history of the world; some knowledge of what to read in English literature, and how to read it; the ability to express their thoughts in correct English, gained by actual practice in composition, rather than by study of technical textbooks on rhetoric; an elementary knowledge of physics, botany, and zoology; some knowledge of physiology and of the laws of health; some training in vocal culture and vocal music; [and] a course, for those who desired it, of Latin, French, or German.30

Believing in a strong link between reading and morality, Swett held particular views about how to promote literacy among youth, including limiting homework for high school girls in order to allow them time to read for pleasure. “From ten to sixteen is the golden period for the reading of good books,” he wrote, “and any course of school-work that deprives pupils of time to read by keeping them all the time at the drudgery of text-book lessons is a mental wrong and a physical sin.”31 He also had particular ideas about the kinds of books that would enrich the minds and moral characters of young people. Recommending writers such as Thomas Carlyle, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and—especially influential for Wolf—Louisa May Alcott, he advised teachers to “see to it that [their pupils] do not poison themselves with sensational and trashy stories and novels,” such as “the sentimental love-stories devoured by too many girls.”32 Harriet Lane Levy, valedictorian of Emma’s class at Girls’ High School and one of the few graduates to continue her education at the University of California Berkeley, described in her memoir how the girls began the school day by reciting lines of verse they had selected, with poets ranging from Shakespeare to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and William Cullen Bryant. When she became a famous writer, Wolf credited the education she received in the San Francisco public schools. In a 1901 interview in the San Francisco Examiner, for instance, she recalled “a valuable lesson” that she learned in grammar school when a teacher “corrected a tendency to the use of superfluous language in my composition. ‘Emma,’ said she, ‘your balconies are bigger than your houses.’ Ever since,” Wolf concluded, “I have tried to avoid verbiage.”33

Wolf’s education thus lay rich ground for her career as a writer, even as her experiences at Girls’ High School reinforced traditional ideas about gender. Among his sample composition assignments, Swett specified that the prompts “A Fairy Tale” and “How to Make Bread” were for girls and the prompt “Going a-Fishing” was for boys, while sample grammar exercises asked students to identify parts of speech in sentences such as “The boys read well, and the girls sing sweetly.”34 If the school’s educational philosophy reinforced gender divisions, Swett’s experience teaching in the San Francisco public school system, with its large number of Jewish and Catholic students, made him a strong advocate for religious liberty and the separation of church and state. Explicitly defending the rights of his Jewish students, he eliminated the practice of devotional prayers and the use of the Bible in daily reading exercises. Levy’s reminiscences of her high school years confirm that the school’s Jewish students would not have experienced significant ostracism due to religious difference. Instead, as Levy relates, social hierarchies were based on the conflation of class and national origin. Levy, whose parents were Polish immigrants, “pretended to be of German origin in school to avoid being considered lower class.”35 As descendants of French-Alsatian immigrants with Germanic backgrounds, the Wolf sisters would have been secure in their social status, although it is unclear whether and to what extent Emma would have been stigmatized for her physical disability. Her friendships with girls of Eastern European descent, including Levy, indicate that she was admired for her studiousness and that she was immune to the snobbery that infected some of her classmates, instead seeking out like-minded peers who shared her intellectual proclivities.

At Girls’ High School, Emma developed a close friendship with a fellow Jewish student, Rebekah Bettelheim (1864–1951), a Hungarian immigrant who arrived in San Francisco from the East Coast at age ten. The daughter of Aaron Bettelheim, a progressive rabbi who left Hungary in protest over some of his colleagues’ religious fanaticism, Rebekah would go on to marry Rabbi Alexander Kohut and become a leader in the American Jewish community in her own right, publishing two autobiographies that document her life experiences on both coasts. Writing in 1925 of her childhood friend, by then a “brilliant authoress,” Kohut remembered Wolf as a strong student. She “was handicapped from birth by a useless arm, but there was no defect in her mentality,” Kohut wrote admiringly. “Her memory was the most remarkable I have ever encountered. She could quote with equal facility the texts of long poems or the fatality statistics of each of the world’s great battles.” Kohut described Wolf as serious and sensitive, a lover of natural beauty. During botany excursions in the California sandhills, the two girls collected “new specimens of flowers” to mount and display at home, “v[ying] with each other . . . to get . . . the largest and best collections.”36

These walks also provided the girls with opportunities to discuss their shared religious background. Like most thoughtful adolescents, they struggled to define their still-forming identities, openly debating whether it was better to identify as Jewish or to assimilate fully. Their conversations continued to have a profound influence on the two friends, even as they ended up on diverging paths. From her adult standpoint as a distinguished communal leader, having married a widowed rabbi with eight children and devoted herself to the cause of Jewish education, especially for women, Kohut reflected on her conversations with Wolf in her 1925 memoir, My Portion:

But what meant most of all to me, perhaps, in those impressionable days of adolescence, was the exchange of innermost thoughts with my classmate. I had begun to doubt the worthwhileness of all the sacrifices it seemed to me that my father and his family were making for Judaism. What was the use of it all, I questioned. Why make a stand for separate Jewish ideals? Why not choose the easier way and be like all the rest? The struggle was too hard, too bitter. Emma Wolf was undergoing much the same inner conflict. It meant real suffering to both of us. The spiritual growing pains of adolescence are hard to bear. They cannot be laughed out of existence.37

Despite claims from historians that the Golden State removed the restrictions that Jews faced in Europe and on the East Coast, Kohut’s declaration makes clear that prejudice against Jews did exist in California. The effects of anti-Semitism may have been minor compared to those experienced by Jews in other regions; nonetheless, these two young Jewish women struggled with, and were shaped by, their sense of difference. Here, Kohut notes the “sacrifices” her father made for Judaism. Elsewhere in her memoirs, she discusses Rabbi Bettelheim’s efforts to forge alliances across religious lines and befriend clergymen of various faiths. Kohut inherited her father’s “desire for the understanding and amity of those outside the family, the tribe, the religion, the nation,” writing that “my father’s attitude about people outside the creed is also my attitude.”38

Judging by Wolf’s fiction, these conversations with Kohut about religion left a long-lasting impression on her heart and mind as well. In Other Things Being Equal, for example, Wolf’s Jewish heroine, Ruth Levice, learns from her father that friendships between Jews and Christians are natural outgrowths of “fellow-feeling,” echoing the worldview that Kohut inherited from Rabbi Bettelheim. “I’ve always been led to believe that a broad-minded man of whatever sect will recognize and honor the same quality in any other man,” states Ruth, asking, “Why shouldn’t I move on an equality with my Christian friends?”39 The tension between “mak[ing] a stand for separate Jewish ideals” and being “like all the rest” is also at the center of Heirs of Yesterday. While Philip May takes assimilation to the extreme, going so far as to pass as Unitarian, most of the other Jewish characters, including the heroine, Jean Willard, find ways to maintain their Jewishness without significantly jeopardizing their place in mainstream American society. Importantly, it is the institution of Reform Judaism that allows Wolf’s Jewish-identified characters to negotiate a middle ground and, by the novel’s end, to begin bringing Philip back into the fold.

Wolf and her family made similar negotiations. As early members of Temple Emanu-El, they were at the vanguard of significant changes in American Judaism, with a new generation of spiritual and lay leaders pushing to modernize a religion that was associated with stagnant Old World values. In 1885, a group of rabbis, led by Kaufman Kohler and Isaac M. Wise, convened a conference in Pittsburgh, where they adopted a set of principles that became the basis of Reform Judaism until 1937, when the Central Conference of American Rabbis implemented revisions. Known as the Pittsburgh Platform, the 1885 document held that Jews are “no longer a nation, but a religious community”; that “the modern discoveries of scientific researches in the domains of nature and history are not antagonistic to the doctrines of Judaism”; and that “Judaism [is] a progressive religion, ever striving to be in accord with the postulates of reason.” The articles also addressed the outdatedness of “Mosaic and religious laws [that] regulate diet, priestly purity, and dress,” noting that such rigid observance “is apt rather to obstruct than to further modern spiritual elevation.”40 As one of the earliest American novels to engage with Reform theology and practice, Heirs of Yesterday can be read productively alongside religious documents like the Pittsburgh Platform as well as subsequent literary works depicting America’s Reform Jewish community, such as Sidney Nyburg’s The Chosen People (1917), whose protagonist, Philip Graetz, is a Reform rabbi of a Baltimore congregation.41

In the late nineteenth century, Wolf’s congregation, Emanu-El, became one of the nation’s leading Reform synagogues. Under the leadership of Rabbis Elkan Cohn and Jacob Voorsanger, it initiated looser interpretations of religious law in order “to remake the Jewish liturgy, ritual, and credo to suit the values of the New World.”42 For instance, in an egalitarian attempt to “remed[y]” “the evil” that “excluded women from . . . many privileges to which they are justly entitled,” all congregants were seated together during services, whereas traditionally women were relegated to a separate gallery.43 Emanu-El was one of the first synagogues in the country to prioritize Friday evening services above Saturday morning, thus leaving Saturday open for business or leisure. As Marc Lee Raphael has demonstrated, Voorsanger, who was appointed rabbi of Emanu-El in 1886, one year after the Pittsburgh conference, strongly emphasized the progressive potential of Reform Judaism by drawing links to the American belief in “manifest destiny” and its implied assumption of white superiority. A proponent of assimilation in all matters but religion, Voorsanger was concerned that the influx of newly arrived Eastern co-religionists with their “‘meaningless, Oriental rites’” would “chain Jews to the ghetto,” going so far as to support immigration restrictions to ensure that Jews who were already settled in the United States would not be deemed backward and racially inferior by association. According to Raphael, Voorsanger’s convictions resulted in a “general rejection of all which stood between Judaism and the non-Jewish world” for many Emanu-El members.44 Thus, in accordance with the Pittsburgh Platform, practices that would have interfered in Jews’ ability to socialize and conduct business with their gentile counterparts, such as kosher dietary laws or strict Sabbath observance, were largely abandoned.

While these reforms created a version of Judaism that more closely resembled the practices of their Christian neighbors, many late nineteenth-century Jewish families in San Francisco went a step further, nominally observing holidays like Christmas and Easter to better fit in with the nation’s religious majority. Though these holidays primarily served as yearly occasions to bring family together, rituals like gift giving, Christmas tree decorating, and Easter egg hunts were adopted as part of the festivities, though stripped of their religious significance. In her memoir, The Haas Sisters of Franklin Street, Frances Bransten Rothmann recalls how her German Jewish grandparents “assimilated the customs and rituals of Christian Americans” after immigrating to San Francisco in the nineteenth century.45 At Christmas, the Haas family’s opulent Queen Anne home (today one of the only Victorian mansions in San Francisco that functions as a tourist attraction) was transformed into a “winter wonderland,” complete with a “centerpiece [that] featured a plump suckling pig with a shining red apple protruding from its open snout” and a “ceiling-high tree [that] shone as it revolved slowly on a music stand.”46

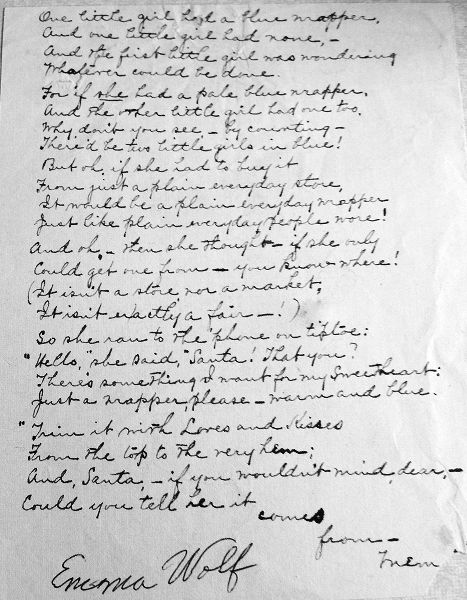

The Wolfs appear to have incorporated aspects of Christmas into their practice as well, especially as the family expanded through intermarriage to include gentile spouses and children who were not raised as Jewish. One of the rare mementos of Emma saved by her descendants is a rhyming poem that she composed for a niece as part of a Christmas celebration. In the twenty-four-line poem, “a little girl” laments that her friend does not have a “blue wrapper” like her own. Instead of going to a “plain everyday store” to purchase “a plain everyday wrapper / just like plain everyday people wore,” the girl finds a solution by running “to the phone on tiptoe” and putting in a call to Santa: “‘Hello,’ she said, ‘Santa! That you? / There’s something I want for my Sweetheart: / Just a wrapper, please—warm and blue.’”47 As sweet and simple as it is, the poem betrays a deeper meaning that resonates with Wolf’s symbolic use of the intermarriage plot in Other Things Being Equal: it suggests an ideal of equality (“two little girls in blue”), but, notably, outward sameness is achieved through the accumulation of luxury goods, available not to “plain everyday people” but to those for whom material means can override other obstacles of difference. In Other Things Being Equal, Wolf uses class signifiers—including fashionable clothing, elegant decor, educated speech, and cultured mannerisms—to indicate “that religion is the sole factor differentiating” Jews from their gentile neighbors; the 1892 novel employs “genteel realism” to “create believable upper-middle-class [Jewish] characters and to convince . . . readers that an interfaith union based on the principle of sameness—‘other things’ . . . ‘being equal’—is realistic as well.”48

Emma Wolf’s handwritten poem to her niece.

Courtesy of Donald Auslen.

In explaining the often radical reinvention of religious and familial traditions on the Western frontier, historian Ava Kahn notes that San Francisco Jews were “able to participate more effectively in the development of [the city’s] Jewish communities” because they did not have “to accommodate themselves to a preexisting Jewish social and religious structure” as Jewish immigrants did in the East. As Kahn writes, “In the Pacific West, all was their own creation.”49 This proved especially true for the elite group of entrepreneurs who had built wholesale empires and whose children became the scions of Jewish high society in the Gilded Age. In addition to witnessing the formation of Jewish religious institutions like synagogues, nineteenth-century San Francisco saw the creation of Jewish secular institutions, including social clubs modeled on the gentile club system. Emma’s brother, Julius, for instance, was a member of the all-male Concordia Club, which was founded in 1864 by denim manufacturer Levi Strauss and other German American Jewish merchants.50 To maintain the clubs’ exclusive status, initiates were nominated and voted on by existing members.

In Heirs of Yesterday, Philip May rejects his father’s suggestion that he try to get into a Jewish club like the Concordia or the Verein, another fraternal club, which originated as a paramilitary group to safeguard the German Jewish community in the aftermath of the Gold Rush. Instead, Philip believes that a Christian club “will prove more congenial than would a club composed entirely of Jews, from whom I have become estranged both socially and sympathetically” (101).51 That Philip ends up blackballed from the Christian club by an anti-Semitic member proves that economic and professional status still could not trump prejudice, serving as an important reminder that Jews created their institutions not only out of a sense of ethno-religious camaraderie and separatism but also because of gentile society’s exclusionary practices. Interestingly, Wolf not only reflects on how anti-Semitism restricts participation in the city’s social life but also shows that blackballing can occur within the ranks; in a turning point of the novel, Philip is rejected from his father’s club as well. By including both instances of rejection, Wolf demonstrates her unwillingness to settle for an easy critique. Whether she is writing about religious exclusivity or changing gender roles, she maintains a nuanced ideological stance and examines sociopolitical issues from multiple angles.

With the formation of the National Council of Jewish Women (NCJW) in 1893, the late nineteenth century also became an especially active period for Jewish women’s organizations around the nation, and San Francisco was no exception. As a member of the Philomath Club, the Bay Area’s first secular organization exclusively for Jewish women, Wolf was part of an emergent San Francisco literary scene that coincided with the rise of the women’s club movement in the 1890s. Founded by Bettie Lowenberg, a prominent member of Temple Emanu-El, the Philomath Club drew upon the synagogue’s sisterhood for its membership, gathering together intellectually minded, affluent women who were interested in “literary and educational pursuits and [the promotion of] civic ideals.”52 Lowenberg was a socialite and philanthropist who later became a published author—her first novel, The Irresistible Current (1908), like Wolf’s Other Things Being Equal, took on the subject of Christian-Jewish intermarriage—and under her leadership, the Philomath Club had a strong literary bent. True to its name, the club’s primary mission was study and learning. But through members’ specific choices of “literary and educational pursuits,” coupled with a collaborative enactment of upper-class mores, the club accomplished a secondary mission: it made Jewish women an integral and visible part of San Francisco’s secular, bourgeois culture.

Despite the shared ethno-religious background of their club’s membership, the Philomath women rarely addressed Jewish texts and topics. Instead, they undertook a course of study that “foster[ed] the neo-colonialism of Anglo-Saxonism,” in Anne Ruggles Gere’s words.53 English literature was a frequent topic in the Philomath’s early years, with lectures on writers such as Tennyson and Carlyle. In addition, the women studied topics such as the German legend of Faust, American history, and transcendental philosophy. In the refined comfort of the club’s meeting space at the luxurious Palace Hotel, Wolf was thus able to extend her high school education, engaging in discussion with Jewish women of various ages, attending lectures by professors from nearby Stanford University, and delivering papers herself. Both Wolf and her former classmate Harriet Lane Levy were listed on the program for the Philomath’s first open meeting on January 14, 1895, which featured musical and oratorical performances by club members. As the San Francisco Chronicle reported of the event, “There was a large and distinguished audience present. . . . Miss Emma Wolf’s essay, ‘The Passing of the Ideal,’ a protest against the masculine woman, Miss Harriet Levy’s satire and Miss Florence Prag’s paper showing that intellect is always appreciated by great minds, irrespective of nationality or religion, were all heartily applauded.”54

Like women’s clubs around the nation, the Philomath fostered an environment in which women flourished, creating opportunities for members to display their artistic and intellectual talents. While some outside commentators at the time viewed women’s clubs as covers for suffrage activism, historians have shown that the club movement was largely a conservative force, especially among upper-class and upper middle-class women. Wolf’s presentation, which voiced fears about the “passing” of feminine ideals, demonstrates that the club was devoted to the maintenance of women’s domestic sphere and the cult of true womanhood. In deference to Lowenberg’s beliefs that direct participation in government would corrupt women, the Philomath Club took an anti-suffrage stance, avoiding the topic of the woman’s vote at club meetings.55

Still, by participating in the city’s cultural and intellectual life in a public setting, the Philomath women were contributing to a shift in gender norms. Karen Blair has argued that club activities can be understood in terms of “domestic feminism”—the notion that the woman’s sphere of the home could be extended further to have a positive moral influence on public affairs.56 The Philomath Club supported and nurtured its members’ efforts to enter public life, as suggested by the paths of the three women whose presentations at the first open meeting were singled out by the Chronicle. Florence Prag (1866–1948), who was one year behind Wolf and Levy at Girls’ High School and whose mother was a beloved teacher at the school, would go on to break gender and religious barriers in national politics, making history as the first Jewish congresswoman when she replaced her deceased husband, Julius Kahn, as one of California’s representatives to the House of Representatives in 1925. (By then, with the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, even the club’s staunchest anti-suffragists had conceded the value of women taking more active roles in public affairs.)

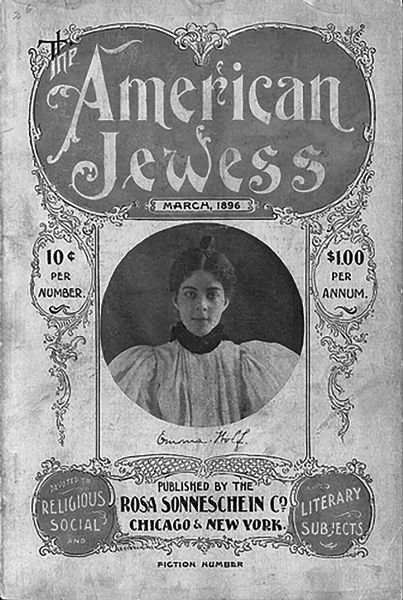

Though Prag’s fame would come later, by the time of the 1895 meeting, Wolf and Levy were already rising literary stars. Having earned a bachelor’s degree in philosophy at the University of California Berkeley, Levy wrote regularly for The Wave, where her short stories, society pieces, and dramatic criticism made her one of the San Francisco journal’s most promising young writers.57 Wolf, too, had published in The Wave. One of her earliest short stories, “Brissac’s Little Debt,” appeared in the journal in February 1892. In the same year, Wolf published her first novel, Other Things Being Equal, with A. C. McClurg to critical acclaim. Due in part to its controversial intermarriage plot, the book became a popular success. It continued to be read and discussed, including by other women’s clubs, well into the twentieth century and was published in a revised edition in 1916. As evidence of Wolf’s national reputation, the American Jewess, the journal founded by editor Rosa Sonneschein to serve as an unofficial promotional organ for the NCJW, profiled her in 1895, noting that Other Things Being Equal “had already reached the third edition and is read by Jews and gentiles with equal interest.”58

It is no accident that Wolf’s most prolific period as a writer occurred in tandem with the golden age of the women’s club movement and during a formative period for women’s rights in the United States. Against the backdrop of shifting gender ideologies, Wolf published five novels between 1892 and 1916, as well as short stories and poems in magazines such as the American Jewess, the Smart Set, and Century. The terms of gender, class, and religion that Wolf negotiated in her own life also played out in the pages of her fiction. These negotiations are further evident in the permutations of her literary career; expanding her oeuvre to include works absent of Jewish characters and themes, Wolf explored a writerly persona unconstrained by ethno-racial difference. But if Wolf’s representation of middle-class Jewish life on the Western frontier in her first book, Other Things Being Equal, made her one of the earliest Jewish women novelists in the United States, her fourth novel, Heirs of Yesterday—with its nuanced treatment of religious, cultural, and familial identity—solidified her status as one of the mothers of American Jewish fiction and positioned her as a pioneering figure in women’s writing and American literary history.

Emma Wolf on the cover of the American Jewess (March 1896).

A “Mother of American Jewish Fiction”: Emma Wolf’s Writing

In an article that appeared in the San Francisco News in the “Who’s Who in San Francisco” column in 1930, two years before her death, Wolf recalled having her first short story published when she was twelve years old. “There was no joy in the experience. I cried bitterly over the affair,” Wolf told reporter Helen Piper, explaining that the piece of juvenilia was not published under her own free will. Instead, “a daring cousin,” thinking “the tale a work of art” and “prompted by the noble purpose of presenting [her] to the literary world[,] . . . stole the manuscript and gave it to the village paper.” The story’s publication proved a source of humiliation for Wolf. “Too ashamed to face anyone,” she “imagined that all the townsfolk were laughing at” her “little love story.”59 The anecdote may not seem like the auspicious beginnings for a literary career, but years later Wolf made an even more dramatic—and this time voluntary—literary debut. In 1892, she published her first novel, Other Things Being Equal, with A. C. McClurg, as well as the short story “Brissac’s Little Debt” in The Wave.

Together, these two publications establish cultural identity as a central theme for Wolf and indicate that her material was often based on astute observations of real people, places, and events. While Other Things Being Equal tells the story of Ruth Levice, the daughter of middle-class Jewish immigrants from France now living in San Francisco, Wolf drew primarily upon her French heritage for “Brissac’s Little Debt.” Demonstrating her connections to her birthland in the American West and to her parents’ homeland of Alsace-Lorraine, the frame narrative of the story is set at the Cercle Français, a private men’s club for French merchants founded in San Francisco in the 1880s and to which Wolf’s brother, Julius, belonged. Arriving late to a reception at the club after a tiring journey, the story’s main character, Josef Brissac, interrupts his friends at a game of cards to tell them of a “little adventure” that “began about twenty years ago and ended last week.” Brissac begins his tale by recalling a traumatic event that occurred in France when he was seventeen years old: his witnessing of the sexual assault and violent death of his mother at the hands of German soldiers during the Franco-Prussian War. He explains to the men that, just the week before, while “riding alone across the plain” in Arizona, he finally had the opportunity to avenge his mother’s murder when he came upon a wounded German in the “scorching” desert. Instead of offering the parched man a drink from his full canteen, Brissac “laughed gayly” and “slowly, very slowly . . . poured the water, drop by drop, upon the blistering sand.” The story’s ending returns to the frame narrative, where Brissac elicits his friends’ responses to his actions, “curious to have [their] verdict of the means [he] took of discharging” the “debt.” The group of friends—which includes a fierce French patriot named Little Chalmont, who had also seen the horrors of war up close—does not respond with words. Instead, Wolf writes, “There came a sound not often heard in the gathering of men,” and she concludes the story with this line: “Little Chalmont was crying.”60

In this provocative treatment of masculinity that captures the deep and lingering emotional effects of war, the brutal death of Brissac’s mother stands in for the men’s loss of and distance from their motherland—a loss that they continue to mourn, even as immigrants in a new land. In this respect, “Brissac’s Little Debt” shares with Wolf’s Jewish-themed novels, Other Things Being Equal and Heirs of Yesterday, an interest in exploring the relationship between familial ties and cultural heritage. But, in other ways, the 1892 short story is atypical for Wolf. “Brissac’s Little Debt” is her rare work of prose without female characters at the center.

Wolf’s five novels and most of her short stories are works of domestic fiction, focusing on young, white, middle-class women whose lives are typically moving in the direction of marriage. Wolf’s reference to her youthful publication as a “little love story” indicates her long-standing inclination toward plots that center around courtship and marriage. As literary critics such as Nina Baym have shown, most nineteenth-century American fiction written by women and for female audiences relied on domestic plots. A novel that ends happily with a Jewish-Christian couple overcoming their religious differences in order to marry, Other Things Being Equal might be labeled a “love story,” though it could hardly be described with the diminutive “little.” Rather, Other Things Being Equal uses its intermarriage plot to tackle big questions about class and gender, faith and secularism, modernity and assimilation, religious pluralism and bigotry, charity and familial obligations—not to mention its more straightforward but equally weighty probing of why people from different backgrounds fall in love and what makes for a successful union.61

If Wolf experienced embarrassment about the publication of her first story, she appears to have grown a thicker skin by the time her first novel was published. Certainly, it would be difficult to imagine anyone laughing at Other Things Being Equal. This accomplished debut, which reads as a work by a mature writer, garnered almost universal praise for its style.62 However, in her willingness to challenge cultural and religious norms through a favorable portrayal of intermarriage, Wolf risked a different kind of negative response. Not surprisingly, her work was a frequent target of criticism within the Jewish community, and the novel continued to be a source of controversy and debate more than a decade after its initial publication. A 1904 article in the Los Angeles Herald, for instance, reported that Rabbi Sigmund Hecht of Congregation B’nai B’rith in Los Angeles opened a talk on intermarriage and apostasy by discussing the “mild sensation” caused by Wolf’s novel. Counterintuitively trying to downplay the impact of Wolf’s novel with the word “mild” and the false claim that her book was now gathering dust “upon the topmost shelves” of libraries (a claim that his own invocation of the text as a means of connecting to his audience immediately belies), Hecht summarized the controversy: “There were those among the readers of her book who roundly denounced the spirit in which it was conceived and written and declared that the author had broken with her ancestral religion and was trying to undermine the faith of her co-religionists,” while “others . . . hailed the sentiments expressed in that book as the powerful manifestation of the progressive spirit of Judaism.”63 Despite the controversy, Wolf did not appear to experience shame about her religious beliefs or regret about her positive representation of intermarriage. When Other Things Being Equal was republished in a slightly revised edition in 1916, she doubled down on the importance of her theme, writing in a new foreword: “In presenting this revised edition to a new generation, the author feels that the element of change has touched very lightly the romantic potentialities obtaining at the time of the original writing. . . . Christian youth still chances upon Jewish youth, and with the same difference of historic background, the same social barriers and prejudices—the same possibilities of mutual attraction. The humanest love knows no sect. . . . It is the story of that beauty, which the author, in this revised edition, for a new generation, has not cared to revise.”64

The existence of the revised edition of Other Things Being Equal further disproves Rabbi Hecht’s assertion that the novel had “seen its day.” If this had been the case, Wolf’s publisher, A. C. McClurg, would not have continued publishing editions of the novel. Yet Hecht’s critique of Wolf is worth serious consideration. It speaks to the ways that the male-dominated American Jewish establishment subtly suppressed the influence of a Jewish woman writer whose progressive ideas, and means of conveying them, were likely to reach a broad audience and have popular appeal.

Even when she was not writing about intermarriage, Wolf’s adherence to a “progressive spirit of Judaism” would continue to dog her throughout her career. The larger questions of how to define Jewishness and whether to maintain orthodoxy or modernize religious practice would shape the works she wrote and determine the stories she chose not to tell. These questions would also dictate which of her writings were published and by whom—and, in turn, who her readers were. The story of how Wolf came to write and publish Heirs of Yesterday—her only extant work with explicitly Jewish content besides Other Things Being Equal—is also a story about the cultural institution of publishing and the gatekeeping role played by the Jewish publishing industry in shaping mainstream representations of Jewishness. The novel’s publication history and reception—from initial responses to its decades of obscurity and up to its recovery today—have much to tell us about which, and whose, versions of Jewish identity hold the greatest weight. In contrast to works by writers like Abraham Cahan and Anzia Yezierska, which have dominated university syllabi and scholarship over the past fifty years, Heirs of Yesterday has remained out of print in part because of the way it challenges conventional understandings of turn-of-the-twentieth-century Jewish identity, ethnicity, and Jewish American fiction. As a novel set in San Francisco that grapples with secularism, Reform theology, and genteel anti-Semitism, Heirs of Yesterday moves us beyond fairly narrow and geographically confined notions of American Jewish identity.

In the years after publishing Other Things Being Equal, Wolf continued to dedicate herself to fiction writing. Previous research has suggested that Wolf turned away from Jewish themes with novels like A Prodigal in Love (1894) and The Joy of Life (1896), both of which revolve around characters who are siblings. Inspired by Wolf’s own large, female-dominated household, as well as by classic works about sisterly relations like Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility and Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women, the family in A Prodigal in Love consists of six girls, while The Joy of Life uses two brothers—and the women who enter their lives—to, in Wolf’s own words, “contrast the materialist with the idealist.”65 Even the short story that Wolf published in the American Jewess, “One-Eye, Two-Eye, Three-Eye” (1896), is absent of Jewish themes, with Wolf again using the contrasting experiences of three sisters to offer a critique of marriage. On the surface, then, the body of work that Wolf published in the 1890s suggests that she left behind the themes of cultural and religious heritage to center on class, gender, and family dynamics. But new research informs us that there is more to the story.

During the period of the 1890s that saw the rising popularity of the ghetto tale, heralded by the Jewish Publication Society’s (JPS) release of British Jewish writer Israel Zangwill’s Children of the Ghetto in 1892, Wolf was actively writing Jewish fiction. The records of the JPS, now housed at Temple University, reveal that they rejected three works by Wolf between 1894 and 1900: a lost manuscript titled A Dreamer of Dreams; a children’s story, “Little Jaffa,” which she submitted for a literary contest; and a manuscript that became the novel Heirs of Yesterday. It is not that Wolf took a hiatus from Jewish content; rather, it appears that she was having more difficulty getting her Jewish-themed material into print. When Heirs of Yesterday finally appeared in 1900, it was published by A. C. McClurg, the Chicago-based firm that had previously taken a chance on Wolf with Other Things Being Equal and subsequently published The Joy of Life.66

The idea to publish her work with the JPS, the nation’s first Jewish publisher, did not originate with Wolf herself. In 1893, the society, in search of “native talent” and aware of the popularity of Other Things Being Equal, contacted Wolf to inquire whether she had a manuscript for their consideration.67 She did. Wolf was working on A Dreamer of Dreams, a novel whose title, taken from a line in Deuteronomy, signaled a theme of spiritual struggle: “If a prophet or a dreamer of dreams arises among you and gives you a sign or a wonder, and the sign or wonder that he tells you comes to pass, and if he says, ‘Let us go after other gods,’ which you have not known, ‘and let us serve them,’ you shall not listen to the words of that prophet or that dreamer of dreams.”68

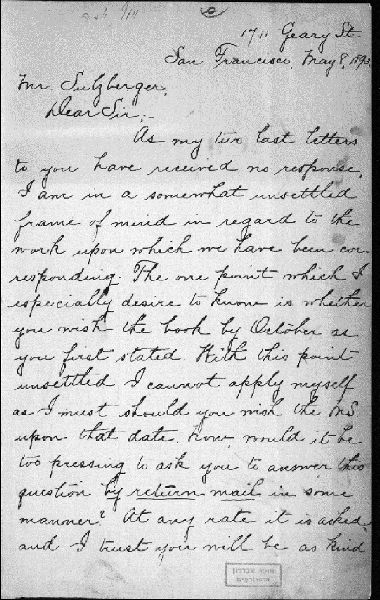

With the original manuscript now lost, the little we know about A Dreamer of Dreams comes from JPS records, including letters Wolf exchanged with JPS chairman Judge Mayer Sulzberger and the minutes from meetings in which the publication committee discussed and evaluated her manuscript. Based on Wolf’s correspondence, her interactions with the JPS’s leadership appear at times fraught, and her ability to work with them was perhaps doomed from the outset. A letter from Wolf to Sulzberger dated May 8, 1893, though respectful, contains hints of her frustration. “As my two last letters to you have received no response, I am in a somewhat unsettled frame of mind in regard to the work upon which we have been corresponding,” she begins, explaining that she was waiting for Sulzberger to confirm that he wanted the book by October in order to “apply myself as I must” to meet the deadline. If the letter begins with a complaint, going so far as to evoke Sulzberger’s guilt for failing to respond in a timely manner, it concludes with a politely worded demand: “Now, would it be too pressing to ask you to answer this question by return mail in some manner? At any rate it is asked and I trust you will be as kind as heretofore and set me right.”69 Even if lightened at the end by a mild compliment (i.e., noting Sulzberger’s previous kindness), the letter reveals an impatient and assertive side to Wolf’s personality. Although others who knew Wolf have portrayed her as retiring, gentle, and even “saintly,” she was not simply a passive and compliant woman.70 Her tone in this letter helps contextualize choices she made throughout her career. These are the words of a dedicated and ambitious writer who was willing to stand by her convictions and ruffle feathers rather than readily comply with the literary establishment’s expectations for her.

Emma Wolf’s letter to Judge Mayer Sulzberger, chairman of the Jewish Publication Society (May 8, 1893).

Courtesy of the Abraham Schwadron Collection at the National Library of Israel.

Subsequent letters from Wolf show that she did finally receive the requested response from Sulzberger, and on November 14, 1893, Wolf mailed the JPS a copy of her manuscript. “I herewith submit for your kind consideration, the MS. entitled ‘A Dreamer of Dreams,’ sincerely trusting it will meet your requirements and approval,” Wolf wrote to Sulzberger. “Should you find any objections upon points which you think I could remedy, I trust you will not hesitate to mention them.”71 Though more deferential in tone than her previous correspondence, this confidently worded letter indicates that Wolf viewed Sulzberger as a professional equal; in requesting his feedback and expressing her willingness to revise the manuscript, she also shows that she saw book publishing as a cooperative venture between writer and publisher. From Wolf’s reference to “objections upon points,” we may further infer that she anticipated pushback. Given the response to Other Things Being Equal, Wolf was well aware that her own religious principles would meet with opposition from others in the Jewish community, especially from an institution like the JPS, which toed the line between orthodoxy and reform to maximize its audience in the interest of revitalizing Jewish American culture.

The JPS’s deliberations on her manuscript confirm its desire to steer clear of overly controversial material, as the “objections” were entirely focused on content rather than style or aesthetic value. Soon after receiving Wolf’s manuscript on November 24, 1893, the society sent it out to a series of readers: Dr. Marcus Jastrow on November 27; Rev. Dr. Joseph Krauskopf on December 11; Mr. Simon A. Stern on January 8; Mr. A. L. Isaacs on January 15; and finally, on February 7, Dr. Cyrus Adler, a leading Jewish scholar and editor who was one of the founders of the press as well as of the American Jewish Historical Society.72 On February 28, 1894, the publication committee met to discuss Wolf’s novel among other agenda items. The minutes reveal that they were unable to arrive at a decision due in part to “slim attendance” at the meeting. According to the minutes, Isaacs’s “favorable report” met with strong opposition from Adler: “Dr. Adler agreed with Dr. Isaacs in thinking the story good from a story-teller’s point of view, but considered some of the characters immoral, and the Rabbi hero impossible. In his opinion, the fact that whenever a traditional Jewish custom is discussed in the book, the Rabbi declares himself conscientiously unable to observe it, ought to suffice to prevent the publishing of the book by the Society.” Isaacs, in turn, “thought that the Society would be missing a fine opportunity to make itself popular . . . and that the Committee ought to avoid judging” Wolf’s manuscript “from any but the literary point of view.”73

The minutes offer only a tantalizing glimpse of Wolf’s lost manuscript. Like Heirs of Yesterday, the book appears to deal with the modernization of American Judaism. But unlike Wolf’s other fiction, in which none of her Jewish characters are clergymen, Dreamer apparently featured a rabbi as its main character. From the sound of it, Wolf was using fiction—one of the few public forums available to women in the nineteenth century—as a means of grappling with the important theological questions of the day. That her “rabbi hero” chooses to forego traditional observance implies that the book was written in a “progressive spirit” and was sympathetic to Reform Judaism, with its initiative to modernize Jewish religious practice as an “alternative to assimilation.”74 Although the brief summary of the meeting offers no details about the style of Dreamer, its high literary quality was undisputed. The writing was likely artful and accessible, drawing upon the principles of realism as her other novels did. In Isaacs’s opinion, the work would attract a popular audience, perhaps even because of its controversial subject matter; the popularity of a work of fiction by a homegrown American author would be a real boon to the JPS, whose reputation at that point rested largely on historical texts, with the exception of Zangwill’s book about Jewish life in the London slums, Children of the Ghetto.

If the minutes are too spare to shed substantive light on Wolf’s manuscript, they do succinctly capture the competing demands on the JPS and the factors that went into the production of Jewish American fiction at the turn of the twentieth century. Even as the society was committed to publishing works of high quality, artistic value was not the dominant criteria for all of its board members. Many believed the publications should serve political and didactic functions. Given its mission of unifying the Jewish people through shared culture, the press feared alienating readers. Adler’s concerns about immorality and the “impossible” rabbi character stem from the press’s commitment to “Jewish pluralism and doctrinal neutrality.”75 Most, but not all, of the publication committee may have taken issue with Wolf because they opposed radical Reform Judaism, but their objections were born less from personal ideologies and more from pragmatism. On the one hand, for Isaacs, the controversial nature of the work that bothered Adler would boost the book’s popularity. On the other hand, Adler felt that the work would prove too divisive; like Other Things Being Equal, it would highlight ruptures within the Jewish community.

Although the committee adjourned the initial meeting, deferring the decision about Wolf’s manuscript so that more members could be present for the discussion, Adler’s argument was ultimately to win out. On March 28, 1894, a special meeting was convened at the JPS office in Philadelphia with two objectives: to arrive at a final decision about whether to publish Wolf’s novel and to consider the report of the Bible translation committee. The minutes of the meeting, again, reveal a mixed response to A Dreamer of Dreams. On one side, Jastrow and Stern advised against publication. On the other, Isaacs was joined in his support for publication by Reform rabbi Joseph Krauskopf. Krauskopf’s support for Wolf’s novel is not surprising; as leader of the Philadelphia synagogue Keneseth Israel and champion of Reform innovator Isaac Mayer Wise, Krauskopf had openly expressed his concern that the JPS held an anti-Reform bias.76 It was Adler who broke the tie, “mov[ing] that it is not expedient to publish the novel ‘Dreamer of Dreams.’”77 Since the JPS was a subscription service, with all members automatically receiving copies of the society’s published works, Adler was not simply motivated by marketability in making his tie-breaking decision. Unlike Isaacs, who insisted that the JPS would benefit from Wolf’s popularity even if readers did not need to be enticed to purchase the book, Adler feared that the novel would tarnish the JPS’s reputation. While the brief minutes intimate that some members of the committee may have been offended by Wolf’s novel, Adler’s use of the word “expedient” presents us with an incontrovertible fact: despite the quality of Wolf’s writing and her skill as a popular storyteller, a significant portion of the JPS’s readers would have found the novel’s liberal stance offensive and held the society, not just the author, accountable.

However Wolf responded to the news, the JPS’s rejection of A Dreamer of Dreams did not affect her productivity or dampen her aspirations to further her career as a writer. Her second published novel, A Prodigal in Love, appeared in 1894 with New York publisher Harper & Bros. Especially productive throughout the 1890s, the decade that saw the publication of four of her five novels, Wolf attributed her success to hard work and determination. “Inspiration,” she explained, “was an illusion that I once believed in, in common with most younger beginners. Perspiration has much more to do with it.”78 Nor did the JPS’s rejection deter Wolf from trying to publish with them again. Fewer than three years after they passed on A Dreamer of Dreams, Wolf entered her story “Little Jaffa” in a literary contest sponsored by the JPS. In an effort to reach the youngest generation of American Jews, the JPS promised a prize of one thousand dollars, a large sum for 1896, to the writer who submitted the best children’s story.79 In this case, we have even less information about the content of Wolf’s manuscript and the prize committee’s deliberations, but it is clear that the debate was contentious and that some of the contention was sparked by Wolf’s writing.

Among the twenty-seven manuscripts received by the JPS, Wolf’s story was preferred by one vote to the other top-rated story, Louis Pendleton’s Lost Prince Almon. Wolf again had won the support of Rabbi Krauskopf, as well as Simon Stern, a Reform lay leader who had opposed publication of A Dreamer of Dreams. According to Jonathan Sarna, when the committee reached an impasse in its deliberations, they decided to follow “the Solomonic suggestion” of one of the members that it was best not to award a prize if they could not arrive at a consensus.80 The contestants were subsequently notified of the JPS’s decision to refrain from selecting a winner. Wolf never knew that her story was one of two considered the best of the twenty-seven submissions, nor did she know that the vote was so close. She received the same form letter as all of the contestants, informing her that the committee decided not to award a prize because “no story of Jewish interest suited to young readers and satisfactory to the Judges” was “offered.” The letter complimented the “competitors on the ability and taste displayed in many of the stories submitted” and “expresse[d] the hope that works from their pens may someday be added to the Society’s list”—words that may have given Wolf partial encouragement to submit one more manuscript, Heirs of Yesterday, to the JPS soon after.81

The content of “Little Jaffa” remains a mystery, and events that transpired after the contest at once heighten the mystery and offer potential clues about Wolf’s lost work. Eager to bring out quality children’s literature, the JPS decided to publish two of the works submitted for the contest. One was Sara Miller’s Under the Eagle’s Wing (1899), a piece of historical fiction-cum-adventure story about a teenage boy who becomes a disciple to Moses Maimonides in Egypt during the Middle Ages. The other, Louis Pendleton’s Lost Prince Almon (1898), turned out to be the story that deadlocked the committee, rivaling Wolf’s “Little Jaffa” as a top contender for the literary prize. What makes the decision to publish Lost Prince Almon and not Wolf’s story especially curious is its author background. Despite the JPS’s mission to publish and promote Jewish writers, Pendleton was not Jewish. He was a Southerner whose previous works for children included a Civil War adventure, In the Okefenokee: A Story of War Time and the Great Georgia Swamp (1895), and a story of postbellum race relations, The Sons of Ham: A Tale of the New South (1896). Marketed by the JPS as an illustrated gift book for Jewish children, Lost Prince Almon follows the adventures of a young Prince Jehoash, later to become king of Judah, and was drawn from the Old Testament. Combining religious and historical content with the exotic veneer of Orientalism, Miller’s and Pendleton’s stories share the didacticism common to nineteenth-century children’s literature. Based on the JPS’s decision not to publish “Little Jaffa,” despite the fact that more than half of the members of the prize committee saw value in it, we can assume that the text defied expectations for religious children’s literature of the time. Given the committee’s responses to this and other works by Wolf, it is exceedingly unlikely that the decision reflected on her capabilities as a writer.

Thus, a published work of Jewish children’s literature from Emma Wolf was never to be. Interestingly, however, her story “One-Eye, Two-Eye, Three-Eye,” which appeared in the American Jewess in 1896, engages with the tradition of didactic children’s literature, especially its effect on girls; the story takes its title from a Grimm brothers’ fairy tale to offer a critique of gender relations and the institution of marriage. The year 1896 was to prove an important one for Wolf. In addition to seeing this story and her poem “Eschscholtzia (California Poppy)” printed in the American Jewess, she published The Joy of Life with A. C. McClurg and began a correspondence with Zangwill, the JPS’s star author of Jewish fiction, which would last for four years and have a strong influence on both their careers.82