— PROFILE —

by Michel Bergeron

This story is not just about a straw bale house, it’s about an architect’s dream house for her family—an affordable, comfortable, ecological home in the city. It is also about an enthusiastic straw-baler determined to be the first to build in a major Canadian urban center—not just on the outskirts, but a mere ten minute walk from the downtown center.

I had been fantasizing about building a straw bale house in Montreal for many years. I had met Julia Bourke, a teacher in the Affordable Housing Program at McGill University who was interested in ecological housing. One day she called to ask if a straw bale house in Montreal was a realistic goal and if I’d be interested in working with her on the project. My positive answer was all she needed to start the process right away.

— THE PROJECT —

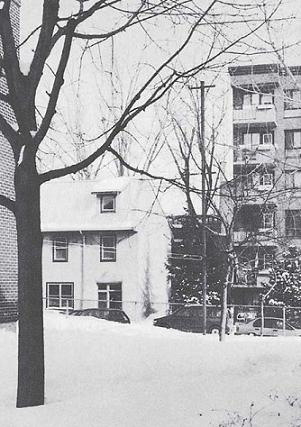

The house that Julia was living in was located on a property that ran between two streets, deep enough for subdivision into two small lots. The street behind was essentially abandoned. She was aware of the existence of a multitude of similar vacant lots in her working-class neigh-borhood, and she discovered that the property had originally had two distinct dwellings. Over the years, however, city regulations had changed to favor larger lots than those typical of Montreal’s early settlements. With many origi nal buildings burnt down or demolished, particularly during the 1970s, these neighborhoods couldn’t be reconstructed. Bourke’s first objective, designing a sustainable home, became paired with a second one: encouraging urban renewal, or sustainability, through the construction of housing on undersized lots.

The dream house turned into a demonstration project when research funding became available through the ACT (Affordability and Choice Today) program funded by the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation. The first objective was to show that small-lot housing could improve housing affordability, promote choice and quality in the urban context, and revitalize older neighborhoods with a type of housing compatible with the historic architectural fabric of the community. The second objective was to introduce straw bale construction to Canadian Cities.

The small-lot issue was not the only regulatory constraint tackled by this project. The city’s regulations, amazingly, prohibited single-family homes in Bourke’s neighborhood, as well as affordable, traditional design choices such as stucco facades and pitched roofs. Our design and construction team worked closely with city planners, providing historical analysis, documentation of existing conditions, identification of potential building sites, and design guidelines. The advice of the city’s professional design review committee was considered, and public opinion was sought through neighborhood consultations. The scope of this effort underscores the necessity of collaboration among architects, housing and planning specialists, contractors, and community organizers.

Accessible and affordable: balloon-frame construction, with bales inserted between studs.

— THE DESIGN —

Sustainability was weighed against affordability in the selection of systems and materials for the house. Most important to Bourke were simplicity and accessibility in the building process. It was essential to her that she and her family be able to contribute easily with their own hands; to understand and love the house not only because of its functionality and beauty, but through their participation in the process. She also wanted to show that the experience of owner-building does not have to be relegated to the countryside.

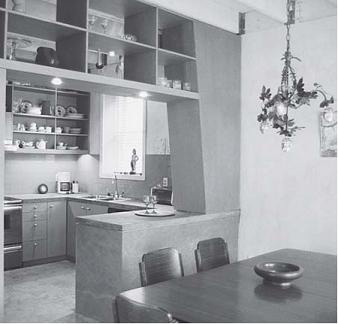

Based on my prior experience, we decided that the most accessible, affordable building technique would be a combination of a traditional balloon frame with straw bale infill. The house is a two-and-a-half-story, 1,700-square-foot building. It features a hydronically heated, straw-bale–insulated slab-on-grade, with its top slab left exposed and waxed, with a linseed-oil sealant. The second and third floors are made of tongue-and-groove softwood boards simply treated with a natural oil finish. Joists of both floors are also exposed underneath to create a warm, spacious feeling. The roof is constructed of durable galvanized steel, or “galvalum”; the pitch is shifted off center toward the street to create a more urban facade as well as more efficient interior attic space. The roof insulation, originally planned to be straw bale, was changed at the last minute to incorporate R-50 “dense-pack” blown-in cellulose. The front, southwest-exposed, 60-degree pitch was planned to eventually support solar panels hooked to the hydronic system. The gentler pitch of the northeast section of the roof also allows better sun penetration into the backyards of both Bourke’s and the neighbor’s house.

The balloon-frame structure was built on a standard 10-inchwide concrete frost wall, insulated with 4-inch rigid rockwool boards covered by cement-fiber panels finished with plaster. Notched bales were inserted in a standing position between studs spaced at 18 inches on center, and attached to them with poly strapping. The 11.2-inch x 31.2-inch notch along the interior edge of each bale accommodates the stud, making the exterior wall plane a fully uninterrupted straw surface. The familiar balloon frame was chosen for the same purpose of keeping the straw unin terrupted from ground to roof, avoiding the extension of floor platforms into the core of the bales. The second- and third-floor joists are therefore attached to a border joist bolted to the inside face of the studs. Windows were installed in cantilevered plywood boxes screwed to the inside studs.

Both interior and exterior plasters are made of the same 5:1 lime-cement mix. Dry oxide pigments were added to finish coats for color Graded sands were used in decreasing sizes from base to finish of the exterior coats to reduce moisture capillarity. Chopped straw was incorporated in the base coats for additional cohesion. A narrow strip of expanded metal lath was nailed to the interior face of each stud to hold the plaster.

Another innovative ecological aspect of the house is the use of Isobord panels (see chapter 15, “Beyond the Bale”) for all the cabinets, baseboards, and a few decorative wall panels. These surfaces were also simply treated with natural oil-based finishes. Milk paints were used everywhere else where color or protection was desired.

Straw bale construction sites attract curious visitors.

— THE WORK AND RESULTS —

The building permit was delayed due to ongoing municipal elections, so only the site excavation and foundations were done before winter froze hard. As soon as the temperature became mild again in April the framing was started, even though the snow had yet to melt and the ground was not thawed. There were a few unusual details to care for in the structural work: along with studs spaced at 18 inches on center, they also had to span two and a half stories in a single piece. Since you don’t find 2x4s that long any more in this prefab world, two lengths had to be spliced together. For wall-raising convenience this was done after the first floor was built. A good set of temporary braces was necessary to hold the frame firmly together during construction.

After the roof was assembled, sheathed, and temporarily waterproofed with tar paper, the straw work could finally begin. A pizza party was organized for the first delivery of bales. Expected to arrive in the late afternoon, the 35-foot flatbed with 350 bales aboard finally got in at 8:30 due to a tire replacement on the highway and a lot of tango dancing with the cars parked along the narrow streets of the neighborhood.

Two workshops were held during the weekend when we poured the straw bale slab (see “The Archibio Sandwich Slab” in chapter 5), and TV and newspaper reporters and photographers assailed us, while a growing number of curious and amazed neighbors suddenly realized that something very unusual was happening. Two kindergarten classes even came along to play with this fantastic new construction material!

During the duration of the bale work we were careful to bag and store the considerable quantities of loose straw produced by the notching. In fact, we ended up packaging no less than 250 garbage bags of the loose stuff. Since mulching materials are like gold in a city, these and some 75 damaged bales were happily recycled by community gardeners.

A few modifications and adjustments were also required in the subsequent work. We had begun the bale attachment procedure by tying the bales to the frame with horizontal metal H pins made from masonry wall-reinforcement rods. These ladder-type, light-gauge wires are easily cut and rigid enough to make good staples. The whole system was too labor-intensive, however, and not always as reliable as we wanted. The pinning would have worked better if done by the same people all the time, but we had such a rotation of volunteers that it was impossible to maintain consistently rigid attachments.

After a short period of investigation we came up with the strapping solution. I bought a tensioner, a crimping tool, crimps, and a couple of rolls of poly strapping from a packaging-tools supplier. The new system made the work progress much faster. Many bales could be placed in a row without any sort of attachment, and then strapped in a bundle while others were installed in the next row, and so on, in rotation. We could adjust the rhythm to the number of people involved. It also appeared that the strapping contributed to the overall stability of the building by making every wall like one huge, rigid panel. We also successfully used the strapping system to retie odd-shaped bales and make new ones, which made 64-inch-long bales as easy to make as 18-inch ones. We even thought for a moment that we could strap together one long bale to fill the entire height of the house and lift it into place like a giant cigar. Yet appropriate tensioning to keep the bale from rippling seemed too hard to achieve, though this idea could lead to further experimentation in the preassembly of entire sections of freestanding walls.

The characteristic deep window well of a straw bale house.

The Bourke family kitchen.

The other problem we had was the plaster mix. We fiddled awhile with a base mix that was always lacking cohesion. No matter what proportions of water or sand we used, the plaster would not stick well to the straw. I finally realized that the lime we were using was probably not fully hydrated and that it needed to be soaked before being mixed with the other ingredients (see chapter 11). As soon as we started to pre-soak the lime, even for just an hour, the mix became easy to work with, directly on the straw. Chopped straw was added to the first and second coats to reduce cracking. Because the weather had been a blessing and the sun was constantly shining hot, special care was needed to keep the fresh plaster continually moist to favor an appropriate cure. Other than a couple of cracks, which seem directly related to expansion of the metal lath supporting the sunexposed plaster or to joints with wood pieces, the exterior walls are crack-free. The interior plaster didn’t fare as well, displaying many superficial cracks, the causes of which are currently being investigated. Fortunately the interior walls are less vulnerable to weather and can wait for the necessary maintenance.

Sensors were installed in the slab at four locations and in the walls at five others to monitor seasonal as well as long-term moisture fluctuations. Readings should help us understand the seasonal movements of moisture in both slab and walls, if any (see chapter 14 for more on this subject).

Voilà!

The Bourke family moved in after four intense months of work, but it was three more months before all the interior details were finished and an open house was held for the public. No less than a thousand visitors queued up during two sunny weekends in October to see for themselves the feasibility of a straw bale family dream. They probably all went home with a vivid image of the sage green straw bale house as a distinctive reminder of “green architecture” in the city.