Choosing Your Plants

There are several things to consider as you select plants for your garden: your area’s hardiness zone, your garden’s soil type, each plant’s sun and moisture requirements, and the type of plants (annual, biennial, or perennial) you would like to grow.

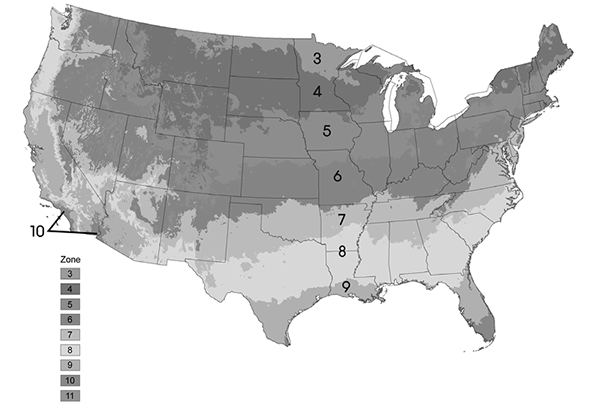

Hardiness zones indicate whether or not a plant can survive the winter in your area. These are based on the average low temperature at which a plant can live. Most annuals, except those that require a long growing season, are not rated by zone as they complete their life cycles in one season. Zones serve as a basic guideline because temperature ranges fluctuate over time. It is also important to take into consideration the protected areas of your property where plants may be sheltered from winds and heavy frost or snow as these make a difference to a plant’s survivability. Refer to the map in Figure 1.3 to help you determine which plants may work best in your area. More detailed and regional maps from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) can be found online.6

Figure 1.3. This is one of many plant hardiness zone maps provided by the US Department of Agriculture.

I live in zone 5 of northern New England, so a plant that is hardy to zone 8, the southern states, is not going to survive in my backyard. However, a plant designated as zone 6 may grow in my garden if it is in a sheltered location. Sometimes it is worth experimenting. A technique to try for plants of a warmer zone than where you live is called “over-wintering,” which is easier to do with plants that are kept in containers. It simply requires that the plant be moved to a warmer, usually indoor, location during the winter. One that I want to try is rosemary. This shrubby evergreen is hardy to zone 7 and obviously will not survive outdoors in a Maine winter. However, with the right conditions indoors, it might do well.

Soil type is the next factor to consider when choosing plants. There are many ways that soil is described, such as light or heavy, but these terms are not all that helpful. Also, while some sources may list up to ten, there are really just four basic types of soil: sandy, silt, clay, and loam. An easy way to figure out what you have is to fill a jar with soil from your garden. Put the lid on tight, shake it vigorously, and then let it sit for a day or two. The soil will settle into distinct layers. With larger particles, sand will settle to the bottom, clay will go to the top, and silt will be in-between. Their percentages will indicate the type of soil you have. If there is a fairly even amount of all three, your soil is called loam.

While a loam soil is considered the best for general gardening, the other types can be adjusted with compost (see Chapter 7). When plant guidelines call for rich soil, it is referring to a loamy soil that has been well composted or fertilized. If you want to grow plants that require sandy soil but your garden is mostly clay, do not add only sand as you will end up with a sort of concrete. Use compost and a little sand to condition a clay soil. Soil type can also be dealt with by using raised beds, containers, or a combination of these.

Along with soil type, moisture content is something to keep in mind when planning which plants to group. An herb that needs dry conditions should not be planted with ones requiring higher moisture. Also, keep in mind that the term “moist soil” does not mean that it should be soggy or waterlogged.

|

Soil Type and Moisture Content |

|

|

Basic Soil Types |

|

|

Sandy |

Largest particles, dry and gritty to the touch, does not hold water |

|

Silt |

Medium-size particles, smooth to the touch, slick when wet |

|

Clay |

Smallest particles, smooth to the touch when dry, sticky when wet |

|

Loam |

A mix of sand, silt, and clay |

|

Soil Moisture Content |

|

|

Dry |

Limited watering, soil dry to the touch even below the surface |

|

Moderately dry |

Top of soil is dry to the touch but may be slightly damp underneath |

|

Moderately moist |

Top of soil may be slightly dry to the touch but remains a little damp underneath |

|

Moist |

Needs frequent watering, soil remains moist to the touch, should never dry out, should not become a puddle or waterlogged |

Sun requirements are, of course, an important consideration, too. Here again, the requirement categories are basic guidelines. I have found that some plants noted to require full sun actually do well in the parts of my garden that do not get a full six hours of direct sunlight. However, these areas are sheltered by a fence and I think the warmth that is maintained in these locations provides a good balance. Experimentation is the best way to determine what will work best for your garden.

|

Sun Requirements Decoded |

|

|

Full sun |

At least 6 hours of direct sun |

|

Partial sun |

Between 4 to 6 hours of sun |

|

Partial shade |

Between 2 to 4 hours of sun. While plants in this category need sun, they also need relief from it. |

|

Shade |

Less than 2 hours of direct sun |

|

Dappled or filtered sun |

A mix of sun and shade |

Don’t let all this information overwhelm you. Knowing the conditions in your garden allows you to choose the most appropriate plants. Refer to the Plants at a Glance table for an overview of the general requirements for the herbs listed in Part 3 of this book. While we want to provide the best conditions for our plants, one of the good things about herbs is that they are generally hardy and can do well even if everything is not perfect.

Another point to consider is the types of plants you want to grow. Like flowers, herbs fall into the categories of annuals, biennials, and perennials. As its name implies, an annual completes its life cycle in one year. It flowers, sets seed, and dies in a single season. Biennials take two seasons. These usually only bloom and set seed in their second season. Perennials live from year to year. While the top portion usually dies back in the autumn, the roots remain alive but dormant through winter. In the spring, perennials come up again.

Annuals take a little more work, as they need to be replaced each year. Some will reseed themselves, but not all. One thing I enjoy about annuals is the change-up they give to my garden each season. They can be grouped differently and planted in different spots. In addition, even though biennials have longer lifetimes, they can be changed out every couple of years for different effects.

You should also consider the remedies you want to make when choosing plants. For example, if you and your family are prone to catching colds and the flu or suffer from digestive issues, you may want to consider a garden that will be most useful for these particular needs. APPENDIX A will be helpful for this as it contains a listing of ailments and conditions and the herbs used to treat them.

|

Plants at a Glance |

|||||||

|

Herb |

Type |

Zone |

Light |

Soil |

Moisture |

Height |

Spacing |

|

Angelica |

Biennial |

4 |

Partial shade |

Loam |

Moderately moist |

5–8' |

3' |

|

Anise |

Annual |

Any |

Full sun |

Sandy loam |

Dry |

24" |

12–18" |

|

Basil |

Annual |

Any |

Full sun |

Loam |

Moist |

1–2' |

12–18" |

|

Bay |

Perennial |

8 |

Full sun to partial shade |

Sandy loam |

Moderately dry |

2–50' |

Depends on pruning |

|

Borage |

Annual |

Any |

Full sun |

Sandy or chalky loam |

Moist |

1–3' |

24" |

|

Caraway |

Biennial |

3 |

Full sun |

Sandy loam |

Slightly dry |

18–24" |

6–8" |

|

Cayenne |

Annual |

7 |

Full sun |

Any |

Moist |

24–36" |

24" |

|

German chamomile |

Annual |

Any |

Full sun to partial shade |

Sandy |

Moderately dry |

30" |

6–8" |

|

Roman chamomile |

Perennial |

5 |

Partial shade |

Loam |

Moderately moist |

8–9" |

18" |

|

Clary |

Biennial |

4 |

Full sun |

Slightly sandy loam |

Moderately moist |

2–3' |

9–12" |

|

Herb |

Type |

Zone |

Light |

Soil |

Moisture |

Height |

Spacing |

|

Coriander/cilantro |

Annual |

Any |

Full sun to partial shade |

Any |

Dry |

18–14" |

8–10" |

|

Dill |

Annual |

Any |

Full sun |

Loam |

Average moisture |

3' |

10–12" |

|

Fennel |

Perennial |

4 |

Full sun |

Sandy or loam |

Moderately dry |

4–5' |

12" |

|

Garlic |

Perennial |

4 |

Full sun |

Loam |

Moderately moist |

1–2' |

6" |

|

Hyssop |

Perennial |

4 |

Full sun to partial shade |

Sandy or loam |

Moderately dry |

2' |

12" |

|

Lavender |

Perennial |

5 |

Full sun to partial shade |

Slightly sandy loam |

Dry |

2–3' |

12–24" |

|

Lemon balm |

Perennial |

4 |

Full sun to partial shade |

Loam or sandy loam |

Moderately moist |

1–3' |

12–24" |

|

Lemongrass |

Perennial |

9 |

Full sun |

Sandy loam |

Moist |

3–5' |

2–4" |

|

Marjoram |

Perennial |

9 |

Full sun |

Sandy |

Moderately dry |

12" |

6–8" |

|

Herb |

Type |

Zone |

Light |

Soil |

Moisture |

Height |

Spacing |

|

Parsley |

Biennial |

5 |

Full sun to partial shade |

Loam |

Moist |

12" |

8–10" |

|

Peppermint |

Perennial |

5 |

Full sun to partial shade |

Loam or slight clay |

Moist |

12–36" |

12–24" |

|

Rosemary |

Perennial |

8 |

Full sun |

Sandy |

Dry |

3–6' |

24–36" |

|

Sage |

Perennial |

4 |

Full sun to partial shade |

Sandy loam |

Moderately moist |

1–3' |

24" |

|

St. John’s wort |

Perennial |

3 |

Full sun to partial shade |

Slightly sandy loam |

Moderately dry |

2–3' |

16–18" |

|

Spearmint |

Perennial |

4 |

Partial shade |

Loam |

Moist |

12–18" |

12–24" |

|

Thyme |

Perennial |

5 |

Full sun to partial shade |

Sandy loam |

Moderately dry |

6–12" |

10–12" |

|

Valerian |

Perennial |

4 |

Partial shade to full sun |

Loam |

Moist |

3–5' |

36" |

|

Yarrow |

Perennial |

2 |

Full sun to partial shade |

Any |

Moist |

1–3' |

18" |

Depending on the herb and the part or parts of it that you want to use to make remedies, you may need more than one plant. This is because most leaves are better when they are harvested before a plant flowers. For example, if you want to use the leaves, seeds, and roots of angelica you will need separate plants. On the plant from which you take leaves, cut the flower heads off so they do not bloom and go to seed. This way, you can continue harvesting leaves that will be full of flavor and medicinal potency. The plants that you let flower are the ones from which you would harvest seeds and roots. Sow a few of the seeds in the autumn to propagate more plants. Angelica is a biennial that is good at reseeding itself. I started out with two small plants and now have an angelica patch in a corner of my garden.

Plan for Aggressive Plants

Peppermint and spearmint have robust root systems that can be invasive and take over your garden. The easiest way to deal with them is to grow them in containers. Another way to keep them in check is to sink barriers about twelve inches deep into the soil around them. Stones, bricks, or other garden edging material can be used for the barriers. Large clay flowerpots or clay chimney flues also work well. In addition, the roots of marjoram can become aggressive if the plant is not divided every couple of years.

Given a chance, dill, lemon balm, St. John’s wort, and valerian will also try to take over the garden, but not because of rambunctious root systems. You can almost guarantee that any seeds they drop will sprout, producing many plants. This can be avoided by removing the flowers before they have a chance to go to seed. You will find more information about growing herbs in containers in Chapter 9.

6. Visit http://planthardiness.ars.usda.gov for more USDA maps.