12

THE TONSIL FOCUS

Whether the tonsil focus or the dental focus is more debilitating to the body is difficult to say. Nevertheless, no matter which one holds that dubious honor, there is no question that these two foci are the most pathological focal infections in the body.

W. D. Miller, Edward C. Rosenow, Frank Billings, Martin Fischer, and many other turn-of-the-twentieth-century focal infection researchers studied the effects of tonsil foci just as rigorously as those of dental foci. As discussed in chapter 8, Rosenow proved that the streptococcus bacteria that most commonly reside in the tonsillar region migrate through elective localization or selective affinity to various susceptible areas, or disturbed fields, in the body.1 These disturbed fields can be located anywhere from the eyes to the toes, but the five typical target tissues, or “rheumatic disturbed fields,” that provide the most hospitable environment for the chronic invasion of strep bacteria are the joints, the heart, the kidneys, the gut (stomach and small intestine), and the brain.2

THE ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE TONSILS

Tonsils are large lymph nodes embedded in the mucosal membrane of the throat. The five tonsillar tissues include:

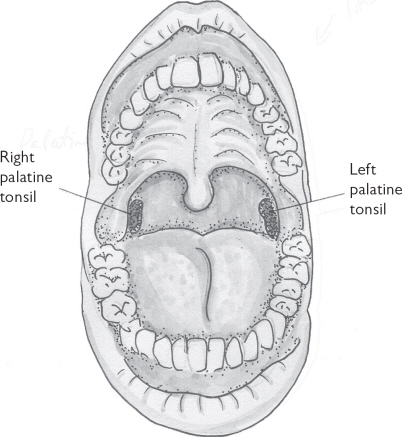

1. The paired palatine tonsils located in the back of the throat, most typically called “the tonsils.” These may or may not be visible in the mouth.

2. The pharyngeal tonsil located in the nasopharynx area in the roof of the mouth, which cannot be seen without special instrumentation. Commonly called “the adenoids,” this lymphatic tissue is approximately 10 millimeters in length (less than half an inch).

3. The lingual tonsil located at the base of the tongue, and bordering the palatine tonsil, which can be inspected only when the tongue is stuck far out of the mouth.

4. The laryngeal tonsil located near the vocal cords in the larynx (windpipe), which is not readily visible without special instrumentation.

5. The bilateral tubal tonsils located just posterior to (behind) the Eustachian tube opening in the nasopharynx, which is also not readily visible without special instrumentation.

These five lymphatic tissues are arranged in a ringlike formation in the throat (at the junction of the oral cavity and the pharynx) that is known as Waldeyer’s ring (see figure 12.1).3

Tonsillar Ring Protects Body from Inhaled or Ingested Toxins

This strategically situated ring of protective lymphatic tissue guards against the invasion of foreign substances into the body. In fact, no food, breath, or microbe can enter the body without passing through the domain of the tonsillar ring.4 Thus, whether toxins are inhaled or ingested, the job of the tonsils is to localize them and produce phagocytes—white blood cells that literally phagocytize, or eat, toxins—that can engulf and destroy these invaders. During these normal lymphatic defensive measures, the tonsils increase in size or swell. However, if the microbes or toxins are particularly virulent, the tonsils may become inflamed and the swelling, pain, and redness associated with a sore throat or tonsillitis ensue.

Figure 12.1. There are five tonsils arranged in a ringlike formation (Waldeyer’s ring) in the throat that protect the body against pathogenic microbes and other toxins.

Tonsils Filter Toxins from the Teeth and Nose

The tonsils also act as an intermediary station of elimination between the head and the body. For example, when German researcher Henke injected small amounts of fine sterilized soot into the nasal mucosa of research subjects, he found that the soot would accumulate in the tonsils within a short period of time.5 Later Henke, along with Permut and Roeder, proved that dental toxins are also quickly shunted to the tonsils. In a study conducted by the three researchers, when India ink was injected into the dental pulp (the center of the tooth) of test subjects, “punctate stipulation”—or little dots—of ink would appear on the tonsillar surface within twenty to thirty minutes.6 Thus, the tonsils are responsible for filtering (if they can) the toxins and microbes from the nasal and oral mucosae.

Direct Communication Between Tonsils and Gut

The digestive system is one long tube from the mouth to the anus. The tonsils—or the remaining lymphatic tissue in the throat after tonsillectomies—are an integral part of that system. They stand like two pillars of defense and detoxification on either side of the mouth. Therefore, anything that is disturbing to the gut is disturbing to the tonsils. The communication between the tonsils and the digestive system is so closely linked that in immunology they have been termed the “gut-associated lymphoid tissue,” or GALT. This system of lymphoid tissues consists of the tonsils and adenoids, the Peyer’s patches (lymphatic aggregations in the ileum, the third part of the small intestine), and the appendix. However, the tonsils are more affected by ingested toxic foods and substances than the more distal lymphatic tissues in the gut, because they are the “site of first encounter (priming) of immune cells with antigens (toxic foods and substances) entering via mucosal surfaces.”7 Therefore, the tonsils filter not only toxins from the nose and mouth but also those ingested and digested by the gut.

THE FORMATION OF A TONSIL FOCUS

Tonsil foci usually develop in childhood from chronic infections. Occasional sore throats, colds, earaches, and fevers can be quite normal in children and, when not suppressed, allow the immune system to exercise and enhance its defensive capabilities. However, the more continuous—and in some cases constant—infections that tend to plague children nowadays are not normal and indicate that something is wrong with that child’s immune functioning.

Three Major Allopathic Mistakes in the Treatment of Tonsillitis

1. Failure to Fully Diagnose

The mistakes modern allopathy makes in the treatment of tonsillitis are threefold. First, conventional doctors fail to adequately diagnose the true cause of the infection. Tonsillitis, strep throat, and other diagnostic labels only describe the outcome—not what caused the infection in the first place. Although the passage of germs in school-age children will occasionally overwhelm even the strongest immune system, chronic infections signal a deeper problem.

Dairy allergy. One of the most common causes of chronic tonsillitis is an undiagnosed food allergy. And of all the classic allergenic foods, the most typical culprit contributing to chronic upper respiratory infections is dairy. That is, although other food allergies can also chronically irritate and inflame the tonsils, milk, cheese, and other dairy products are by far the most culpable.I And when combined with sugar (ice cream, milk chocolate, milkshakes, etc.), as well as the ingestion of other junk foods (soda pop, fried foods, etc.) that have also been proven to reduce immune system functioning, the eventual formation of a tonsil focus in susceptible constitutions is almost ensured.

Suppressed emotions. Another major cause of chronic tonsillitis is emotional disturbance, such as the “lump in the throat” feeling that arises with sorrow and directly affects the tonsils. In fact, one German physician has asserted that she has never seen a tonsil focus in individuals who did not experience the effects of major parental discord as children.8 Most notably, the chronic “stuffing of feelings” that occurs when individuals are not able to fully and authentically express their emotions can greatly block this throat chakra region. This unresolved emotional discord is often a major stimulus in the manifestation of more bouts of tonsillitis, and a chronic cyclical pattern of ill emotional and physical health.

These psychosomatic manifestations are no longer simply a New Age notion but have been incontrovertibly proven through psychoneuroimmunology research. Beginning as early as the 1950s and primarily stimulated by Dr. Hans Selye’s work, studies have revealed that chronic emotional stress weakens immune system functioning, specifically through a decline in natural killer (NK) cells and monocytes (key defender cells). In the case of the tonsils, the classic pattern of the conscientious and sensitive child constantly repressing feelings of anger and sadness not only fuels the cycle of chronic tonsillitis and the eventual formation of a tonsil focus but also can contribute to the future onset of cancer, arthritis, asthma, chronic depression, and anxiety.9

Chronic tonsillitis and emotional repression are especially damaging during a child’s formative years, when the immune system and the psyche are learning to discriminate “self” from “non-self.” In fact, the syndrome PANDAS, discussed later in this chapter, is an example of autoimmune illness that arises directly from streptococcus-infected tonsils and round after round of damaging antibiotic drugs.

Author and psychoanalyst Jane Goldberg, Ph.D., has noted that inadequate discrimination of self on the psychological level characterizes the disease of narcissism or lack of appropriate ego development, and inadequate discrimination on the physical level results in cancer or lack of adequate immune system surveillance. These psychosomatic diseases so mirror each other that Goldberg, the author of Psychotherapeutic Treatment of Cancer Patients, has referred to cancer as “a condition of biological narcissism.”10 This strong psychosomatic association helps explain the strong link between the significant emotional issues typically seen in patients with serious tonsil focal infections and (without effective treatment) the eventual onset of cancer. This tonsil focus–cancer link was extensively researched by the German physician Josef Issels and will be covered later in this chapter.

Mercury amalgam fillings. As described earlier, tonsils receive and filter toxins from the teeth and oral cavity. Therefore, when chewing releases mercury from amalgam fillings, this toxic metal passes through the tonsils and remains there when the lymphatic organ is not fully functioning. This accumulation of mercury and other heavy metals in weakened tonsils is another major contributor to the formation of a tonsil focus. Furthermore, as with a dental focus, when the tonsil region becomes a chronic focus, the resident bacteria there continually complex with the metallic or inorganic mercury emitting from neighboring amalgam fillings. When this occurs, the mercury is “methylated” by the bacteria, which renders this newly converted organic mercury ten to one hundred times more toxic than the original metallic mercury in the amalgam filling.11

Susceptibility or miasmic tendency. Another cause of chronic tonsillitis is simply an individual’s inherited weakness, or miasm, as discussed in chapter 1. That is, some people respond to stress—whether it’s dairy, sugar, or emotional pain—with headaches, others with joint pain, and others with chronic upper respiratory infections. Those individuals who respond primarily in the sycotic reaction mode are most prone to frequent tonsillitis, otitis (ear infections), and sinusitis. However, after years of physical or emotional stress, numerous bouts of tonsillitis, and the excessive use of suppressive antibiotics, individuals with a chronic tonsil focus begin to manifest more serious symptoms.

“Diseases of childhood, grown old.” After many years of the infection/drug/immune response cycle, the tonsils become more and more degenerated and the individual begins to function primarily in the exhausted tuberculinic reaction mode. In these cases, fewer bouts of acute tonsillitis occur. This lack of reaction is often mistaken for “growing out of it” as children mature into their teens and twenties. However, these individuals often trade chronic tonsillitis for chronic fatigue, or other symptoms characteristic of a hidden tonsil focus in adults, as described by Dr. Martin Fischer in the mid-twentieth century:

For it is said that the diseases of man’s maturer years are naught but the “diseases of his childhood, grown old.” What was acute sore throat in his teens is a pus-exuding or scarred tonsil later . . . All his diseases in fact are become but the manifestations in the upper decades of life of what in adolescence were “growing pains,” stomach aches, vomiting spells, fever attacks, anemias, headaches, constipations, faintings and fits [seizures].12

2. The Nonjudicious Prescribing of Antibiotics

The excessive use of antibiotics is the second mistake allopathic medicine makes.II Approximately two-thirds of all infants in the United States receive antibiotics within the first two hundred days of their life.13

Mistakenly prescribed for viral infections. The widespread pediatric practice of prescribing antibacterials to treat viral infections including the common cold, many sore throats, and the flu is particularly indefensible.III In fact, the Centers for Disease Control have reported that of the 235 million doses of antibiotics consumed in 2001, an estimated 20 to 50 percent of these doses were unnecessarily prescribed for viral infections.14

Antibiotic resistance. When a patient’s sore throat is of bacterial origin, the overuse of antibiotics is still indefensible except in dire emergencies. The epidemic use of these antibacterial drugs has encouraged the emergence of dangerously mutated antibiotic-resistant strains that do not respond to any antimicrobial drugs.15 In the case of chronic tonsillitis, the continual use of antibiotics almost ensures the formation of a tonsil focus by leaving the more virulent strains of bacterial carcasses and their toxins behind in the connective tissue.

Fortunately, medical students and residents are now taught that children with upper respiratory symptoms should not be treated with antibiotics unless drainage persists for ten to fourteen days. Unfortunately, there is a “striking dichotomy” between what is taught and what is practiced in the doctor’s office. A recent survey of family practitioners and pediatricians revealed that doctors are often pressured to prescribe antibiotics by parents (often through the need of a working parent to more quickly return to work), by legal liability concerns in case the child does develop a more serious infection, and through drug promotion by pharmaceutical companies.16

Linked to autoimmune diseases. Bacteria and other infectious agents, as well as the previously described emotional repression in childhood, have also been implicated in inducing autoimmune disease.17 That is, when bacterial proteins or antigens chronically invade the tonsils, the tonsillar tissue can become so altered that it is no longer recognizable as “self ” to the body’s immune system. Consequently, when the body’s defensive antibodies mount an attack against these foreign bacterial invaders, they are not able to recognize “self ” (the tonsil tissue) from “non-self ” (the bacteria and bacterial toxins). Therefore, these immune system antibodies mistakenly attack both these tissues as if they were foreign invaders. This complication can occur even after the original inciting microbes have been killed.18 Through this autoimmune miscommunication, the “smoldering” tonsil focus becomes even more firmly entrenched in the system, and it slowly but surely loses its capacity to repel foreign toxins from its tissues. Unfortunately, many researchers now believe that the chronic use of antibiotics for tonsillitis actually strengthens this autoimmune response.19

3. Inappropriate and Ineffective Tonsillectomies

The third mistake modern medicine makes is the overuse of tonsillectomies. Although the common practice of prophylactically removing the tonsils as if they were simply vestigial tissues without function has been widely denounced, tonsillectomies are still the second most common surgery of childhood, with 600,000 being performed each year.20 There are a number of reasons why these traditional tonsillectomies “miss the mark.”

vestigial: The term vestigial refers to the remnant or trace of a structure that had been functional in a previous state of human development but currently serves little to no use in the body.

Inadequate diagnosis. First, surgery does nothing to shed any light on or treat the cause of chronic tonsillitis. Therefore, the damage that food allergies, suppressed emotions, mercury, and other toxic stressors cause is then simply shunted postsurgically to deeper immune system defensive organs—primarily the thymus and spleen.

Incomplete surgeries. Second, tonsillectomies are often performed incorrectly. As described earlier, the incomplete removal of these chronically infected lymphoid tissues can be more dangerous to the body than leaving them intact. In the landmark 1928 study by researchers Paul S. Rhoads and George F. Dick, the “stumps” and “tags” left behind from the surgeon’s knife (or spatula) were found to harbor even more pathogenic bacteria per gram of tissue than the original tonsils contained before surgery.21 To quote these researchers directly:

It is shown by this work that tonsillectomy as usually done even by specialists fails to accomplish this end in 73 percent (!) of cases because of incomplete removal of infected tonsillar tissue . . . in many instances the condition resulting from incomplete tonsillectomy is worse than that existing before operation . . . Patients who with systemic diseases attributable to foci of infection failed to improve after their original tonsillectomy, improved strikingly after removal of the pieces of tonsillar tissues remaining from the first operation.22

TONSILLOTOMIES

A tonsillotomy—the excision of only the top part of hypertrophic tonsils—is an example of truly misguided surgery. The tonsils can function only when their surface mucosa with its superficial crypts can excrete toxins. Therefore, cutting off this excretory ability through a tonsillotomy is counterproductive. Dr. Peter Dosch stated, “A tonsillotomy is never able to eliminate a tonsillar interference field but, on the contrary, is more likely to produce one.”23

In 1912, Dr. Frank Billings, another legendary researcher in the focal infection field, made the following remarks about ordinary tonsillectomies:

Ordinary tonsillectomy leaves an abundance of lymphoid tissue which may be sealed over by the operative scar and leaves a worse condition than that for which the operation was made . . . in that foci of infection are frequently walled in.24

In his Manual of Neural Therapy, the German expert in the treatment of foci, Dr. Peter Dosch, reports that the more modern research statistics (mid-1980s) reveal little improvement:

Extensive statistics compiled by university clinics have . . . shown that cures are achieved in only about 50 percent of all cases of those undergoing tonsillar surgery and relapses occur in exactly the same proportion amongst tonsillectomized cases as amongst the untreated. In light of this, Hoff described the results of surgical focus eradication as “shatteringly poor.”25

Remaining scars become interference fields. Even when all of the infected tissue is effectively excised, the remaining surgical scars characteristically give rise to a chronic tonsil interference field with resulting disturbed fields in the body. Dr. Dosch saw so many cases of this condition that he would never discharge any chronically ill patient who had had a tonsillectomy before his or her tonsillectomy scars were tested—“even if the patient’s previous history does not point in that direction.”26

Natural Medicine: The Key to Preventing Tonsil Foci

Most holistic practitioners will say that infants and children are the easiest to treat. In the majority of cases, this pediatric population responds quickly to natural medicine. In fact, an array of holistic therapies have been proven to be safe and highly effective in the treatment of typical pediatric illnesses such as colds, sore throats, and ear infections.27 These treatments include homeopathy (acute and constitutional), drainage remedies, herbal medicine (Western, Chinese, Indian, Brazilian, etc.), essential oils, spinal adjusting, craniosacral manipulation, hydrotherapy, and nutritional supplementation.

When a physician is aware of the clinical evidence as well as research studies that prove the effectiveness of natural and nontoxic therapies, treating upper respiratory infections and other common ailments in infants and young children initially with suppressive drugs is rather analogous to killing a flea with a sledgehammer, and borders on malpractice. Therefore, one key measure that could be taught to allopathic practitioners to help prevent future tonsil foci from ever developing is adopting the protocol to first utilize natural nontoxic therapies (through a referral to a naturopathic, chiropractic, acupuncturist, or other holistic practitioner if the allopathic pediatrician is not well versed in natural medicine) and to reserve the use of powerful antibiotics and other drugs only for when these initial measures fail or in the case of major emergencies. This clinical principle and practice was officially adopted at the 1992 American Association of Naturopathic Physicians annual convention:

The use of antibiotics should be reserved for those patients who are unresponsive to naturopathic modalities and are not making significant improvement in a timely manner (i.e., no response after one week of naturopathic therapy).28

DIAGNOSIS OF A TONSIL FOCUS

Besides the all-important history, the first step in diagnosing a tonsil focus is to inspect the palatine tonsils in the back of the patient’s throat for signs of infection such as redness, swelling, or scarring (from surgery or many past bouts of tonsillitis). However, even when tonsils visually appear to be pink and healthy, physicians should still test for the presence of a silent focus by following up this visual examination with energetic testing, assessing the presence of painful pressure points, or studying mucosal samples.

Inspection of the Palatine Tonsils

The palatine tonsils are bilateral almond-shaped masses located on either side of the back of the throat, between the palatoglossal arch and the palatopharyngeal arch. They may or may not be visible behind the palatine arches in the throat (see figure 12.2). The palatine tonsils are located at the level of the second cervical and the upper part of the third cervical vertebrae. Practitioners should note that simply laying the tongue depressor on the tongue and asking the patient to say “ahh” is often adequate to view the palatine tonsils. In fact, when force is applied to the tongue depressor, this pressure often initiates a spasmodic reflex in which the tongue tries to crowd against the roof of the mouth and thus blocks the view of the throat.29

If they are visible, healthy tonsils should be pale pink in color with an irregular surface area formed by crypts—invaginated blind cavities that extend throughout the tissue. These tonsillar crypts, ranging from ten to fifteen in number, can fill with light-colored plugs that may then be secreted and swallowed, which is a normal lymphatic filtering process that occurs in healthy tonsils.

Figure 12.2. The palatine tonsils may or may not be visible.

The shape of the palatine tonsil varies according to age, constitution (miasmic level), and tissue changes from past or present inflammation or infection. For the first five or six years of life, these lymphoid tissues increase in size and can often be readily seen upon inspection. At puberty the tonsils (and the thymus gland) begin to go through physiological involution, and thus diminish.30

Atrophied Tonsils

In many cases, the palatine tonsils can greatly decrease in size, or atrophy. Inspection is not helpful in these cases because the practitioner is unable to see whether the tonsils are normal and healthy or atrophied and degenerated. Many researchers including Frank Billings, Edward C. Rosenow, and Josef Issels have considered small atrophied tonsils to be the most dangerous type of tonsil focus and the most instrumental in the causation of serious diseases such as cancer.31

Hypertrophied Tonsils

The palatine tonsils may also be enlarged, or hypertrophied, and quite visible in the back of the throat. Tonsillar hypertrophy can be a normal response to acute infection, especially in infants and children. Sometimes the tonsils are so enlarged that they are touching, in which case they are referred to as kissingtonsils. When the palatine tonsils are chronically enlarged, especially after puberty, this is usually indicative of the establishment of a tonsil focus and the loss of effective lymphatic defense in the area. In fact, in the early part of the twentieth century, hypertrophied tonsils after puberty were rarely seen.32 In contrast, they are now a common physical exam finding in teens and even adults. In these cases, pathological streptococci have invaded and proliferated in the tonsillar crypts. In acute tonsillitis, these crypts may be filled with pus. In the case of a chronic tonsil focus, however, these crypts are scarred and the mucosa appears wrinkled and contracted. When the tonsillar crypts can no longer excrete, streptococcus bacteria are deprived of their air supply and decompose into even more pathogenic toxic products. Furthermore, invading toxins are no longer able to be harmlessly secreted but are passed directly into the bloodstream.33 Although many researchers believed that the smaller atrophied tonsils were the most degenerative and serious, Dr. W. D. Miller, as well as several of his Berlin colleagues, found the larger hypertrophied tonsils to be the most damaging, and “dangerous accumulators of pathogenic germs.”34 Hypertrophied tonsils have also been linked to hearing and speech dysfunction, sleep apnea (interrupted and/ or shallow breathing during sleep), allergies, and dental malocclusions (bad bites).35IV

Other Signs of Infection

In acute infections, as well as with chronic tonsil foci, the palatoglossal arch directly in front of the paired palatine tonsils can have a bluish tinge, and the uvula (the small fleshy process hanging down from the middle of the throat just above the back portion of the tongue) may be thickened and have gelatinous areas.36V The tongue may or may not be coated.VI

Inspection Cannot Rule Out a Tonsil Focus

However, even when none of these signs is apparent and the tonsils appear perfectly healthy, there may still be a silent focus or interference field. Dosch cautions that “even the most experienced eyes cannot tell by inspection alone whether the tonsils might be acting as a pathogenic focus or not.”37

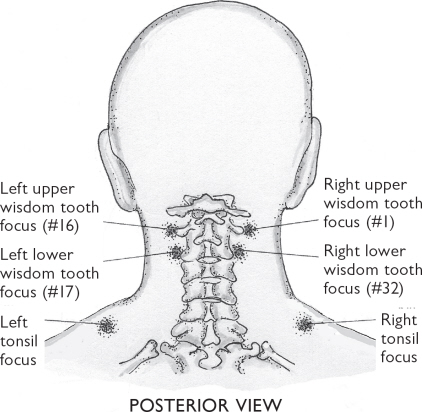

Dr. Ernesto Adler, a renowned Spanish neural therapist, found that patients who had a chronic tonsil focus also had painful pressure points in the trapezius muscle of their upper back and shoulder area. He further correlated painful cervical (neck) pressure points to a wisdom tooth focus (see figure 12.3). Points lateral to the second cervical vertebra are related to upper wisdom tooth foci, while painful points next to the third cervical vertebrae are associated with lower wisdom tooth foci. However, the ipsilateral rule still applies whether the focus is in a tooth or a tonsil. That is, if a right lower impacted wisdom tooth is a chronic focus, then the pressure point just lateral to the right third cervical vertebra should also be tender. Alternatively, if the left tonsil is more degenerated than the right, then the left-sided trapezius points will be more chronically tender and painful.

Of course, sore neck and shoulders and painful trigger points in the upper back have become pandemic in recent times from various reasons—sedentary lifestyles, hunching over a computer for hours at a time, and chronic psychological tension. Therefore, the case for a tonsil focus cannot be based simply on pain elicited from these pressure points during a single examination. However, over time if one or more of these points continues to test positive and is exquisitely tender on deep palpation, the presence of a chronic dental or tonsil focus should be considered.

Mucosal Samples

A sample of the palatine tonsil mucosa can be sucked out with an instrument called the Roeder tonsil sucker.38 This procedure can also be done at home by swiping a sample of the mucus overlying the tonsil with the end of a clean or gloved finger (whether you’ve had a tonsillectomy or not). Simply smelling this sample and monitoring it over time can help diagnose whether you have a chronic tonsil focal infection. If there is no real odor or even just a mildly stale smell, this is less diagnostic of a tonsil focal infection, although a tonsil interference field from tonsillectomy scars can still be present. However, a strong “carcasslike” smell indicative of chronic bacterial invasion and degeneration of tissue is strongly diagnostic of a chronic focal infection.39 Surprisingly, this rotten smell elicited by a finger swab of the tonsils does not necessarily translate into chronic bad breath. Therefore, similar to a coated or uncoated tongue, the absence of halitosis does not rule out the possibility of a tonsil focus.

Figure 12.3. Adler’s trigger points associated with chronic tonsil or wisdom teeth (third molar) foci

Energetic Testing

Energetic testing is another method of physical examination relied on heavily by holistic physicians to determine the presence or absence of a tonsil focus, as well as to ascertain whether that focus is active or dormant. In fact, energetic testing in the form of kinesiology, reflex arm length testing, Matrix Reflex Testing, Auriculomedicine, or electroacupuncture (Voll, Vega, etc.) is essential to corroborate a suspected active tonsil focus, as well as to indicate how it should best be treated. Positive tests through a “therapy localization” of the tonsil area or through a filter such as a homeopathic vial, a sample of tonsil tissue, or a hand mudra are ways the patient’s “inner physician” can signal that an area of focal stress needs to be treated. (See appendix 3, “Energetic Testing Explained,” for more information.)

Is the Dental or the Tonsil Focus Most Culpable?

Energetic testing can help determine if the tonsil is the primary focus or if it is secondary—that is, the disturbed field of a dental focus. Based on research confirming that toxins from the teeth very quickly and directly migrate to the tonsillar tissue, many holistic physicians and dentists advocate the treatment of all dental foci before dealing with the tonsils.40 However, this pathway is not simply a oneway street, because the bacteria and the toxins they excrete may also migrate from the tonsils to the teeth. For example, cavitation surgery of a third molar extraction site is less successful when there is a neighboring tonsil focal infection, especially if that tonsil focus was the original cause of the formation of the dental focus. This latter observation was made by Dr. Henry Cotton as early as the 1920s. Cotton was a brilliant physician who specialized in researching the effect of focal infections in the onset of mental illness. After conducting extensive clinical and laboratory research, he asserted that in most cases the wisdom teeth were not infected because they were impacted but were impacted because they were infected, and that this “infection is transmitted from the tonsils.”41

Through clinical research (energetic testing, observing the effects of auriculotherapy and neural therapy treatments, taking a careful follow-up history each visit, etc.), my colleagues and I have found that the hypotheses of both Cotton and Henke are valid. That is, sometimes the originating focus is the tonsils, and at other times it is the teeth. Effective and sophisticated energetic testing methods are often required to make this relatively complex diagnostic differentiation in order to arrive at a more informed decision regarding appropriate treatment. When serious and permanent decisions must be made, such as the extraction of a tooth versus a tonsillectomy, the gathering of as much knowledge as possible is crucial to the final decision-making process.

Identifying the Disturbed Fields

Energetic testing can also assist with determining which areas of the body—that is, the disturbed fields—have been affected by the tonsil focus. This understanding of the primary cause of painful arthritic joints or chronic fatigue can be both relieving and inspiring. In the case of kinesiological methods, the direct experience of feeling the difference between a weak muscle before treatment compared with an incredibly strong muscle after treatment is empowering to the patient’s subconscious mind-and greatly adds to his or her capacity to heal.

Laboratory Testing

As with most foci, blood tests are not useful in determining the presence of a chronic tonsil focus because longstanding and insidious foci have lost the capability to initiate major immune system responses. Thus, standard blood and urine tests often come back negative. However, in one study of two hundred patients with “clear-cut cases of [dental or tonsil] focal infection,” 63 percent showed a definite leukopenia (decreased white blood cell count) typical of chronic infection, as well as albuminuria (increased albumin or protein in the urine) indicative of chronic liver and kidney dysfunction.42 Therefore, a complete blood count (CBC) may be worthwhile to test for an abnormal white blood cell count, and a urinalysis may elicit positive changes in the albumin count. On the other hand, negative blood tests can never rule out a focus. Dr. Martin Fischer’s frustration with these chronic streptococcal focal infections in the mid-twentieth century are just as valid today for clinicians seeking positive laboratory confirmation:

The streptococcal infections of greatest importance today present a far different front. Instead of acute, their disease manifestations occupy years, are practically afebrile [no temperature], without marked increase in leucocyte count [i.e., white blood cell count normal], and with only the vaguest of localizing signs and symptoms.43

Furthermore, the presence of strep bacteria from a throat culture has been deemed “neither reliable nor valid” in the diagnosis of chronic tonsillitis in numerous studies.44 The “rapid strep test,” which is not dependable even for use with acute infections, is not appropriate for determining the presence of bacteria in chronic tonsil focal infections either.

SYMPTOMS OF A TONSIL FOCUS—THE FIVE RHEUMATIC DISTURBED FIELDS

To most modern readers, the word rheumatism sounds rather passé. For many it may conjure up the image of a grandmother bundled up against the cold in her rocking chair, wringing her painful arthritic hands. However, rheumatic diseases are still very much alive and present in our modern world, and their effects continue to have both a subtle and not-so-subtle impact in most of our lives.

Rheumatism is a general term that refers to various disorders in the body marked by inflammation, degeneration, and derangement of the connective tissues. Rheumatism confined to the joints is known by its more common name arthritis. The related term rheumatic fever is the name for the “acute inflammatory complication of Group A streptococcal infections, characterized mainly by arthritis, chorea [brain disturbance], or carditis [heart inflammation] . . . with residual heart disease as a possible sequel of the carditis.”45 In focal infection terminology, the term rheumatic is used to characterize all the areas in the body—that is, the disturbed fields— where streptococcus bacteria typically metastasize. As previously discussed, Billings, Rosenow, Price, and other early-twentieth-century researchers found that the rheumatic disturbed fields emanating from chronic dental and tonsil focal infections centered primarily in five major areas: the joints, the heart, the kidneys, the gut (stomach and intestine), and the brain.46

Although antibiotics have been credited with a decline in cases of rheumatic fever, a significant decrease had begun even before the introduction of penicillin as a result of improved nutrition, hygiene, and standards of living.47 Furthermore, the liberal dosing of antibiotics without first appropriately assessing the culpable microbe has rendered the diagnosis of streptococcus-induced acute rheumatic fever and its complications relatively obsolete.VII However, over the decades as resistant bacterial strains have emerged, streptococcal infections have increased in virulence and rheumatic fever epidemics have reemerged with a vengeance in more recent times. Laurie Garrett elaborates on this phenomenon in her book The Coming Plague:

In 1985 rheumatic fever broke out among white middle-class residents of the Salt Lake City region of Utah. In just three years’ time the incidence of the disease skyrocketed eightyfold (between 1982 and 1985), and nearly a quarter of the patients suffered recurrences of the disease despite aggressive antibiotic therapy.48

This Pulitzer Prize–winning scientific writer further noted that “such ailments as rheumatic fever, strep pneumonia, and general respiratory infections with streptococcus in young children had never disappeared—or even significantly diminished—in the poor countries of the world.”49 Many knowledgeable holistic practitioners would argue that these streptococcal inflammatory syndromes have never significantly diminished in developed nations either but currently have other disease appellations such as fibromyalgia, Tourette’s syndrome, and PANDAS. These more contemporary-sounding syndromes also result from chronic bacterial focal infections that are fueled by the toxic effects of sugar and other toxic foods, amalgam fillings, petroleum chemicals, and inherited and acquired miasmic susceptibility in the weakened progeny.

Countless research studies have proven that streptococcal bacteria have a marked affinity, or tropism, for specific tissues in the body, thus again proving Rosenow’s theory of selective affinity or elective localization. The particular form of the streptococci microbes can vary, but Billings and Rosenow, as well as Price in separate studies, all found that they generally tend to be of the Streptococcus viridans or Streptococcus hemolyticus (pyogenes) species, or a hybrid of the two.VIII Billings described the research conducted by his protégé Rosenow in detail:

The dominant organism found in abscesses and sealed crypts of the faucial tonsil are Streptococcus viridans and Streptococcus hemolyticus (pyogenes). The S. viridans is usually a surface growth, while the S. hemolyticus is frequently found in pure culture in the deeper infected tissues. In acute rheumatism the bacteria obtained from joint exudates and rheumatic nodes have been studied by Dr. E. C. Rosenow, fellow of the Memorial Institute for Infectious Diseases, cooperating with us. He has found that organisms from rheumatism appear to occupy a position between S. viridans and S. hemolyticus. They are more virulent than the former and less virulent than the latter.50

As was previously described, this streptococcus bacteria disseminates out into tissues and organs from focal infections primarily by blood, lymph, and nerve (axonal) transport. The five major disturbed fields that the streptococcus bacterium most prefers—the brain, heart, joints, kidney, and gut—provide the most hospitable environment for this microbe’s continued survival. In fact, the chill that often triggers the onset of an acute rheumatic illness (e.g., a cold or influenza) is one indicator of the change in the body’s internal temperature that has the effect of altering tissue pH. This temperature change and pH alteration favors the growth of streptococcus bacteria in relatively avascular (“partial oxygen”) environments that have the potential of becoming chronically disturbed fields. In fact, any change in environment (exposure, hard work, injury, amalgam filling, sugar bingeing, and so forth) can “alter the nutrient medium” and facilitate easier ingress of microorganisms from a focus to a disturbed field—or simply increase the pathogenicity of the microbes that are already comfortably settled into their tissue of choice.51

Where a microbe specifically chooses to settle in the body is also influenced by the individual’s miasmic tendency, or reaction mode. For example, a rheumatic manifestation in an individual reacting primarily in the tuberculinic miasm is painful rheumatoid arthritis, whereas someone in the luetic reaction mode may succumb to chronic heart disease. However, simultaneous microbial metastasis to multiple areas is not uncommon, especially in the case of these five rheumatic disturbed fields. Dr. Cotton explained why heart disease and rheumatoid arthritis often occur together:

There may be also repeated attacks [of rheumatic fever] from which the patient recovers, then finally a more severe attack occurs, from which the patient may not recover. As the heart lining is similar to that of the joints it is often attacked by these organisms. This explains the popular expression that “the rheumatism had gone to the heart.”52

The Arthritic Joint Disturbed Field

The metastasis of streptococcus bacteria into the joints and muscles has probably been the most widely researched outcome of dental and tonsil foci.53 In fact, the streptococcus-induced acute rheumatic fever that is characterized by red, hot, and swollen joints most often begins with tonsillitis.54 As was previously discussed, the recognition and subsequent diagnosis of rheumatic fever is now less frequent because antibiotics often quickly reduce the early symptoms of acute ear, nose, and throat infections in school-age children (~ ages 4 to 18). Allopathic physicians herald this symptomatic reduction in acute illness as a modern-day scientific success; however, in light of the astounding proliferation of chronic rheumatic illnesses, the ultimate usefulness of antibiotics is hard to warrant. For example, in 1940 the seventh edition of the Merck Manual described only four arthritic manifestations—rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, gout, and gonorrheal arthritis.55 In less than two generations, however, the fifteenth edition of this manual in 1987 described more than one hundred. Although the Merck editors boast that “increasingly effective drugs have been introduced” to combat these illnesses, this explosion of arthritic diseases and the concomitant proliferation of immunosuppressive drugs (e.g., corticosteroids) and new anti-inflammatories with “serious adverse effects”IX such as Vioxx and CelebrexX hardly illustrates a success story for anyone—with the exception of the pharmaceutical drug companies.56

Every component of our musculoskeletal system is susceptible to streptococcal (as well as staphylococcal and gonococcal) infection. Microbes may travel to the muscles, causing myositis, fibromyalgia, tendonitis, or muscle strain; to the ligaments, contributing to acute and chronic sprains; and to the joint itself, with resulting rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis (degenerative joint disease), adhesive capsulitis (i.e., frozen shoulder), synovitis, and bursitis. Through the extensive research of Rosenow, Price, Haden, and others, chronic and insidiously silent tonsil and dental focal infections were found to be the root cause of most—if not all—of these arthritic disorders.57 Although no recent research has been conducted to determine how many individuals suffering from the “newer” rheumatism-related syndromes—fibromyalgia, Sjögren’s, Raynaud’s, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and Lyme disease—have focal infections, in my clinical experience it has been in the ninetieth percentile.

The Cardiac Disturbed Field

Most focal infection research in regard to heart disease has been centered on dental foci as well as periodontal (gum) disease.58 However, microorganisms from the tonsil region just as commonly migrate through the bloodstream to the heart muscle (myocarditis), the valves (endocarditis), or the pericardium (pericarditis).XI And, as previously mentioned, acute rheumatic fever, in which the most common sequella (lingering sign or symptom) is carditis (heart inflammation), most commonly begins with tonsillitis.59

As is the case for arthritis, it is well documented that a bout of rheumatic fever can precipitate chronic heart disease.60 However, since the heart area often causes no local pain or other symptoms, it can be even more insidious than joint disease and remain undiagnosed for years, or even a lifetime. This is especially true in children, in whom the cardiac symptoms “may be so mild that they escape notice” but later manifest as a valvular scar.61 This classic “rheumatic heart disease without a history of rheumatic fever” affects primarily the mitral valve, and secondarily the aortic valve. In fact, the common diagnosis of mitral or aortic valve prolapse, regurgitation, or stenosis (from an incompetent bulging, thickened, and/or stenosed or narrowed opening disrupting normal blood flow) manifesting clinically in a (readily apparent or subtle) pericardial rubbing sound (“friction rubs”) or valvular murmur or click most often develops from undiagnosed rheumatic fever that is typically considered at the time to be simply a bad cold or “the flu that’s going around.” Mitral valve disease can be so mild that it goes virtually unnoticed, or it may cause chronic palpitations, dyspnea (difficult breathing), chest pain (angina), and fatigue.62

Tonsil and dental foci are not only instrumental in triggering rheumatic fever but are often the root cause of it and continue to sustain this chronic and insidious form of heart disease. The intermittent but continual translocation of bacteria from these undiagnosed oral focal infections can slowly degenerate the heart valve, cardiac muscle, and pericardial tissue and can be the underlying basis—along with mercury amalgam fillings— of “essential” hypertension (high blood pressure), myocardial infarctions (heart attacks), and cerebrovascular accidents (strokes).63 Cor pulmonale—thickening of the right ventricle of the heart with resulting heart failure—has been specifically correlated to hypertrophied tonsils and adenoids, and successful treatment of this syndrome has been documented through tonsillectomy surgery in a pediatric population (children under age eight).64

essential hypertension: Essential hypertension refers to cases of high blood pressure that are deemed idiopathic—i.e., they have no obvious diagnosable causation.

One negative aspect of any form of heart disease or extra heart sounds (friction rubs, valvular murmurs or clicks) is that this diagnosis can follow patients throughout their life and compel dentists to prescribe antibiotics for all their dental procedures—even for twice-a-year cleanings. Although the fear of potential bacteremia (bacteria circulating in the blood) is founded on accurate focal-infection premises as well as in some cases on active heart disease such as chronic infective endocarditis,XII this dogmatic allopathic mandate ensures a life of chronic intestinal dysbiosis for millions, with all the attending immune system deficiencies that excessive antibiotics engender.

Recently, after five decades of endorsing prophylactic antibiotics, the American Heart Association (AHA) finally concluded that there’s no evidence that they work:

“We’ve concluded that if giving prophylactic antibiotics prior to a dental procedure works at all—and there’s no evidence that it does work— we should reserve that preventive treatment only for those people who would have the worst outcomes if they get infective endocarditis,” noted Chair of the new guidelines writing group Walter R. Wilson, M.D., from Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, in a statement issued by the AHA. “This changes the whole philosophy of how we have constructed these recommendations for the last 50 years.”65

The new AHA guidelines still include recommendations for prophylactic antibiotics in the case of more vulnerable populations—those with artificial heart valves, a previous history of infective endocarditis, or serious congenital heart defects.

Even before this change in policy, however, after some years of submitting to this practice, many holistically oriented patients chose to refuse these antibiotic prescriptions and substitute natural antibacterial herbs (e.g., Thorne’s Entrocap) or homeopathic or isopathic remedies (e.g., SanPharma’s Notatum 4X drops) during dental procedures.

Order Notatum 4X from BioResource at (800) 203-3775, and Entrocap from Thorne at (800) 228-1966.

Order Notatum 4X from BioResource at (800) 203-3775, and Entrocap from Thorne at (800) 228-1966.

The Kidney Disturbed Field

The streptococcus microbe also has a special affinity for the kidneys, rendering the rheumatic renal disturbed field as prevalent as the heart and joint fields.66 German ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist Dr. Gruner explains the relationship between ENT infections and these paired blood-cleansing organs:

A special dependence exists between the kidneys and the area of the ear, nose, and throat, because damaging substances can penetrate the body via the skin and mucous membranes in the ear-nose-throat area of the body that the kidneys must eliminate.67

Additionally, in five-element acupuncture theory, the ears have been linked with the kidney meridian and the water element for millennia.68

Acute kidney infections—nephritis, glomerulonephritis, and pyelonephritis—occurring most commonly in children older than age three and in young adults, typically arise after the classic streptococcal infections of tonsillitis and otitis (ear infection).69 That is, in focal infection terminology, these kidney infections manifest either as acute disturbed fields from throat and ear infections or from the acute exacerbation of chronic tonsil and ear focal infections. Renal (kidney) disturbed fields may also arise from gonococcus-infected genital foci such as the prostate and fallopian tubes.

As with heart disease, the relationship between the tonsil focus and the resulting kidney infection often goes undiagnosed because there is a latent period of one to six weeks (average of two weeks) between the upper respiratory streptococcal or genital gonococcal infection and the nephritis. Even more insidiously, about 50 percent of patients with kidney infections are symptom-free (or the mild bladder and back symptoms go unnoticed or unreported).70

In the early twentieth century, researchers Le Count and Jackson found that in animals, although the kidneys’ “acute lesions heal,” their place was taken “by scars, subcapsular retractions, retention (tubular) cysts, and other evidences of ‘chronic interstitial nephritis.’”71 That is, beyond the apparent (or nonapparent) acute signs and symptoms—oliguria (frequent urination), fever, and cystitis or urethritis (pain on urination)—the chronic manifestations of a renal disturbed field are rarely recognized. For example, chronic low back pain (mild to moderate) and fatigue, two of the most characteristic symptoms, classically referred to in Chinese medicine as “deficient kidney chi,” may never be correlated to bouts of childhood tonsillitis. In contrast to the acute kidney and bladder infections that can plague teenagers and young adults, the chronic—yet often mild and intermittent—symptoms from kidney disturbed fields linger for years in adults. The pervasive ENT infections that implant chronic foci in the body are possibly the explanation as to why “by the time the average person reaches age seventy-two, his or her kidneys are operating at only 25 percent of their capacity.”72 Focal infections also often underlie and even fuel interstitial cystitis, a relatively common autoimmune condition in women characterized by chronic bladder inflammation and irritation.

The Digestive Disturbed Field

The primary areas of disturbance in the digestive system are the stomach and small intestine. Dr. Cotton commented on the formation of these disturbed fields:

The stomach and duodenum [first section of the small intestine] are very frequently the seat of secondary foci [disturbed fields]. The infection is conveyed to the stomach, either by means of constant swallowing of infected material from the mouth—teeth and tonsils—or through the lymph or blood circulation, more probably the former.73

One of the major rheumatic manifestations of these disturbed fields are gastric (stomach) and peptic (duodenal) ulcers.74XIII Gastric and peptic ulcers are often refractory to treatment, especially when the primary contributing focal infection is not diagnosed and addressed. Even the reported success of the relatively recent treatment of campylobacter-induced ulcers with bismuth (e.g., Pepto-Bismol) and antibiotics has been found by many practitioners to be lacking and to have a high rate of recidivism (recurrence of the ulcer).75

Appendicitis arising from infection in the ileum and ascending colon can be secondary to a tonsil or dental focal infection or to a genitourinary focus (prostate, fallopian tubes, etc.); however, it can also present independently as a primary focus itself due to major intestinal dysbiosis.

The large intestine and gallbladder are also frequently disturbed rheumatic fields emanating from tonsil focal infections.76 The warm, wet, and enclosed sac of the gallbladder is an especially inviting environment for streptococcus microbes, as well as migrating of intestinal parasites. A major contributing factor to the microbial infestation of the large intestine is biomechanical. That is, as Dr. Cotton observed, we are still paying the price for “getting up on our hind legs.”77 This upright posture forces the bowel contents to “run uphill” in many parts of the colon and to constantly work against the effects of gravity. Furthermore, this bipedal position can seriously interfere with the circulation of blood and over time exhaust the organs, rendering them more prone to infection. This more posturally vulnerable large intestine in humans renders them more susceptible to diseases such as ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, and irritable bowel syndrome, which are often initiated and maintained by a focal infection and fueled by an undiagnosed food allergy.XIV

Stomachaches and appendicitis are often symptoms of focal infections, or disturbed fields from a focal infection, that are actively forming in childhood. These areas of infection and inflamed mucosa (the inner lining of the intestine, gallbladder, stomach, etc.) often manifest later in the adult as chronic ulcers, gastritis, cholecystitis (gallbladder inflammation), “heartburn,” esophageal reflux, and colitis.

The Brain Disturbed Field

Mental conditions caused by tonsil and dental focal infections are relatively unique from the other four rheumatic syndromes in two primary ways. First, only in rare cases do the microorganisms themselves actually invade the tissues of the brain. However, the pathogenic streptococcal excretion products originating in the tonsils and teeth are easily transported through blood and lymphatic vessels, as well as along nerve pathways (axonal transport), to the central nervous system (CNS)—that is, the brain and spinal cord.78 Billings, Rosenow, Upton, Cotton, and others identified this migration in numerous research studies in the early twentieth century and also recorded the resulting disorders—encephalitis (inflammation of the brain), meningitis (inflammation of the membranes that surround the brain), epilepsy, brain abscesses, insomnia, and various other “nervous and mental conditions.”79 Dr. Patrick Störtebecker of Sweden later confirmed these earlier studies through compelling evidence that the combination of mercury from amalgam fillings and bacteria from dental and tonsil focal infections is readily transported from the mouth to the brain and is instrumental in the causation of neurological disorders such as epilepsy, multiple sclerosis (MS), myasthenia gravis, and Parkinson’s disease.80

A second phenomenon relatively unique to the CNS disturbed field is that when the brain is affected, rarely are the joints. That is, unlike the common specificity for some streptococcal strains that attack both the joints and the heart or the joints and the kidneys or gut, in many cases brain and other CNS disorders stand alone.81XV

Chorea, PANDAS, and Tourette’s—All the Same Disorder?

Chorea, a disorder characterized by involuntary movements, has been documented for over a century to be a common manifestation after streptococcal illness and can occur in up to 10 percent of rheumatic fever attacks.XVI This 10 percent estimate, however, is probably too low, because “choreic movements may merge imperceptibly into purposeful or semi-purposeful acts that serve to ‘cover up’ the involuntary motion.”82 And similar to the other insidious rheumatic manifestations, chorealike movements may not begin until much later—sometimes up to six months—after tonsillitis or other acute streptococcus infections.83 Therefore, this and other CNS neurological disorders are rarely correlated to the original strep infection by the patient’s general practitioner.

Chorea and other post-streptococcal-infection CNS manifestations have recently acquired a more modern appellation, PANDAS, which is the acronym for pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections. PANDAS describes a wider spectrum of neurological and psychological disorders that can arise in children after a bout of strep throat.84 The two hallmark manifestations of PANDAS—tics or chorea-like movements and obsessive-compulsive disorders (OCD)—are also seen in Tourette’s syndrome.

OCD-like motor tics can include spitting, licking, touching, smelling, finger and foot tapping, piano-playing movements, kissing, jumping, kicking, hopping, turning, shoulder shrugging, eye blinking, wrinkling of the forehead, nose twitching, pursing of the lips, and other facial grimaces. Vocal tics include swearing, counting (usually inaudibly), coughs, grunts, and clearing the throat—which is also a classic indication of a likely chronic tonsil focus. Obsessive-compulsive concerns overlay the majority of these tics, especially in the area of symmetry—that is, needing to have things “even.”85 For example, an OCD child (or adult) may feel compelled to count out four taps with the right foot, and then four taps with the left.

Other OCD manifestations include constant hand washing and worries about dirt and germs; chronic worrying about any subject but especially religious and sexual issues, as well as safety (for oneself or for others) concerns; ritual arranging of things (stuffed animals, clothes, setting the table, etc.); and repeated “checking” compulsions (stove turned off? doors locked? etc.). Commonly associated symptoms include sloppy handwriting, slight slurring of the speech, separation anxiety (e.g., going to school), hyperactivity, and attention deficit disorder.86 Of course, many of these signs can simply indicate a normal phase of childhood. However, when symptoms arise frequently and continue for long periods (even if they do wax and wane), children should be examined by a knowledgeable physician (a neurologist or holistic doctor aware of focal infections and familiar with PANDAS and Tourette’s syndrome).XVII

Autoimmune Dysfunction in the Basal Ganglia

The letter “A” in the PANDAS acronym aptly describes the real “molecular mimicry”—or autoimmune tendency—of the strep bacterium, which is the primary underlying microbe that sustains a chronic tonsil focus.87 Recently, neural imaging evidence has indicated that the basal ganglia are the areas of the brain most affected.88XVIII These two “pistachio-nut-size areas deep within the brain” receive input from the cerebral cortex and thus have an effect in modifying behaviorXIX and also act as an overall inhibitory “brake” on movement. Therefore, lesions (any pathological process or disturbance in function) in the basal ganglia nuclei have been linked with various movement disorders, including chorea, PANDAS, and Parkinson’s.89

Allopathic Treatment for PANDAS

The current recommended treatments for PANDAS are typically allopathic—primarily antibiotics and even possibly prophylactic antibiotics (long-term use). In many cases, however, these medications do more long-term harm than good by further ensuring an autoimmune response in a chronic tonsil focal infection and its related streptococcus-infected CNS disturbed fields, as well as chronic intestinal dysbiosis. Other novel therapies undergoing clinical trials, including plasmapheresis (a “blood-cleaning” procedure) and intravenous immunoglobulin, are presently restricted to the treatment of very ill patients since the former treatment carries the risk of serious side effects and the latter can cause headaches, nausea, or vomiting.90

I have never seen a child diagnosed with Tourette’s syndrome who did not have an accompanying tonsil focus, and usually a history of a previous significant streptococcal infection.XX Therefore, Tourette’s syndrome and PANDAS are very possibly simply new names for the present-day escalating rheumatic brain disturbances that often occur from increasingly resistant and virulent strep infections. This CNS-damaging tonsil focal infection can be implanted initially from an acute bout of tonsillitis, or it can be an exacerbation of a chronic tonsil focus from many past bouts of tonsillitis and accompanying rounds of antibiotics. Therefore, the current plethora of Tourette’s diagnoses, along with the closely associated hyperactivity and attention deficit disorders, may very well reflect the devastating effects of the modern-day mode of excessively prescribing antibiotics and other allopathic drugs (as well as mercury-preserved vaccines—see chapter 15). In my experience, nontoxic natural treatments for tonsil foci and their associated CNS disorders are greatly superior to allopathic intervention.

Subclinical PANDAS?

Finally, it is interesting to ponder the subclinical (subtle) PANDAS effects that individuals may have been unaware of for years. In general, baby boomers who suffered from numerous childhood upper respiratory infections, whether or not the infections were diagnosed as strep throat at the time, received countless courses of antibiotics. And for the most part, this generation could certainly have been characterized as idealistic, daring, hedonistic—and also perhaps a little obsessive? In fact, many might recognize some of the aforementioned symptoms—counting for symmetry, constantly clearing the throat,XXI obsessive thinking, and compulsive tapping— as subtle but chronic behaviors they have intermittently engaged in for years. For those readers who can identify with one or more of these rheumatic CNS symptoms, the diagnosis and treatment of a possible chronic tonsil (or other) focal infection may be in order.

Dr. Cotton, who had enormous success curing all types of mental illnesses as the medical director at the New Jersey State Psychiatric Hospital, discussed the physical nature of emotional disorders in his 1921 Princeton University lecture series:

For years we have been content to consider mental disorders in two large groups, designated as “organic” [actual pathological changes found in the brain tissue] and “functional” [no pathology found in the brain] . . . This led to the erroneous viewpoint that certain mental diseases could occur independently of any changes in the brain . . . It should be said that the primary lesion which determines the abnormal mental state is most frequently not to be found in the brain itself. The brain cells are constantly influenced by abnormal conditions in other parts of the body through the circulation. Thus, frequently there is a direct action on the cerebral elements by the morbid agents carried directly through the circulation . . . We have seen many recoveries among the acute psychoses occur in a day or two after the removal of the chronic foci of infection . . . we have to recognize the physical nature of the disturbance . . .

Psychoses arise from a combination of many factors, some of which may be absent, but the most constant one is an intracerebral, biochemical, cellular disturbance arising from circulating toxins, originating in chronic focal infections situated anywhere throughout the body.91

Thus, in a time when heredity was considered of “paramount importance in the causation of mental disease,” Cotton was an outspoken and courageous pioneer in the field of psychiatry. In fact, even researchers currently working in the newly emerging mind-body field of psychoneuroimmunology have still not caught up to what Cotton observed countless times at the New Jersey State Hospital in the early 1900s: that chronic focal infections have a major, and sometimes singular, influence on the onset of all types of mental disease.92

Patients who have directly experienced relief from their depression, anxiety, panic attacks, tics, obsessive-compulsive ideations, and other psychological disorders through the clearing of their tonsil, dental, or other focal infection know the emotionally liberating experience effective holistic medicine can provide. In fact, just the psychological benefit derived from simply understanding that psychological disorders are not always solely caused by emotional tendencies resulting from a classic dysfunctional family background is profoundly empowering. And concurrent or future in-depth psychological work and spiritual understanding is immeasurably benefited when these psychophysical obstacles to cure are removed from a patient’s body and consciousness.

The Tonsil Interference Field—Another Contributor to Brain Dysfunction

The brain is adversely affected not only by bacterial toxins but also by nerve dysfunction from a tonsil interference field. The scars in a tonsil interference field remaining after a tonsillectomy, or the scars generated from chronic streptococcal infection (i.e., the focus is both infected and scarred), are a constant disturbing “noise” to the sensitive nerve fibers flowing through this region.93 The primary route of disturbance is cervicocranial— from the neck to the head—through sympathetic nerve dysfunction via the tonsil’s neighboring ganglion.

As discussed previously, autonomic ganglia perform two major functions in the body: (1) they control autonomic—sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve— function, and (2) they act as “storage depots” to hold excess toxins. The palatine tonsils in the back of the throat lie 1 inch away from one of the most important ganglia in the body—the superior cervical. This upper neck ganglion is composed solely of sympathetic motor nerve fibers that control blood circulation in the entire head—the scalp, face, and the brain.94 Tonsillar scars retract and compress the tissues in the nearby superior cervical ganglion, chronically disturbing sympathetic nerve flow. When these sympathetic motor nerves are irritated, they vasoconstrict and decrease the blood flow to all the organs and tissues they innervate. Thus, a tonsil scar interference field chronically deprives the brain of adequate blood flow, oxygen, glucose, and other nutrients. The resulting cerebral ischemia, hypoxia, and hypoglycemia can contribute to numerous neuropsychological disorders, including memory loss and “brain fog,” depression and fatigue, and chronic anxiety. Furthermore, since the sympathetic nerves that innervate the pineal gland derive solely from the superior cervical ganglion, chronic insomnia also commonly results from a tonsil interference field. Other clinically observed cranial signs of a chronic tonsil focus include headaches, dizziness, and even balding from chronic scalp ischemia.95

The two most effective treatments for a tonsil scar interference field are auriculotherapy and constitutional homeopathy, which are described in the following section.

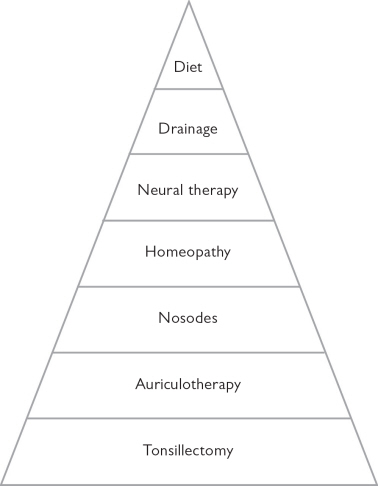

THE SEVEN MOST EFFECTIVE TREATMENTS FOR A TONSIL FOCUS

Similar to the dental treatment pyramid previously illustrated, the seven most effective treatments for a tonsil focus—both focal infections and scar interference fields—are depicted in figure 12.4. It should again be noted that although Rosenow, Billings, Cotton, and numerous other early researchers were truly giants in the field of focal infection diagnosis and treatment, not one of them was aware of the miraculous effects of the correctly prescribed constitutional homeopathic remedy. In fact, although dietary and other general holistic advice was given to patients, only two specific treatments were primarily employed to treat tonsil focal infections in the early and mid-twentieth century—surgery and streptococcal vaccines.XXII More information on these vaccines is included in the following nosodes section (the fifth suggested therapy), because vaccines and nosodes are closely related. Tonsillectomies are the last option, after all other avenues have been exhausted, and therefore are listed seventh in this list.

1. Diet

To reiterate the central thesis of chapter 5, although a clean and conscious diet cannot cure a chronic tonsil focus, without a reasonably clean and conscious diet a tonsil focus cannot heal. In other words, without “plugging the dike” against chronic irritants—allergenic foods, refined sugar, and rancid hydrogenated oils—the tonsillar tissue will inflame daily and thus be unavailable for healing and repair.

The Gut and the Tonsils Work Synchronously

As previously described, the digestive system can be thought of as one long tube, from the mouth to the anus. The tonsils are the two lymphatic pillars that lie on either side of the entrance to this digestive system, and they act as the first defense against all toxic ingested substances. As part of the GALT (gut-associated lymphoid tissue), the tonsils and adenoids—or the remaining lymphatic tissue in the throat after tonsillectomies and adenoidectomies—work so synchronously with the

Figure 12.4. The seven most effective treatments for a chronic tonsil focus, ranging from the most general to the most specific and strongest intervention

Peyer’s patches (in the third part of the small intestine) and appendix that they are functionally considered to be the same tissue. Therefore, any foods or substances that augment intestinal dysbiosis also augment the continued pathogenicity of a chronic tonsil focus. The opposite is also true—that is, any foods or substances that irritate and inflame the tonsils also irritate and inflame the lymphatic mucosa of the intestine.

Must Heal the Gut to Heal the Tonsils

Thus, in order to clear a chronic tonsil focus, individuals must also clear their chronic intestinal dysbiosis. In the case of major tonsil focal infection, an individual may need to adhere to a clean diet for many years. It is especially important to avoid a primary food allergen, since this has a direct adverse effect on the immune functioning of the GALT system. Almost everyone with a major tonsil focus has a dairy allergy, and many have secondary sensitivities to wheat, corn, soy (even properly fermented), and other foods. Although rigid adherence is not always necessary—that is, the use of organic raw butter, cultured cottage cheese, some raw goat and sheep cheeses, and occasional desserts and alcohol during celebratory occasions may not badly sabotage an individual’s progress—the general axiom that “the cleaner one’s diet, the faster one’s healing” tends to hold true. In most instances, through trial-and-error testing, knowledgeable holistic patients become quite aware of what foods serve and do not serve their general well-being. Foods that are questionable can be energetically tested by a holistic practitioner and then double-checked by the patient through the elimination-challenge test at home. (See chapter 6 for more information on the elimination-challenge test.)

MILK FOR ULCERS—TREATMENT DEBUNKED

The past use of milk for treating ulcers has currently been debunked.96 Furthermore, this practice is unwarranted for treating a rheumatic ulcer caused by a focal infection because it only exacerbates the dairy allergy that most probably contributed to the formation of the tonsil focus in the first place.

DEALING WITH CRAVINGS

It’s important to note that being too rigid with a diet is never a good idea, especially since the opportunistic candida fungus that greatly proliferates in the presence of toxic microbes or mercury can dramatically magnify a person’s sugar cravings. Do the best you can, and when cravings become too intense, indulge in low-glycemic-index treats that are easier on the pancreas—fresh fruit with nuts (soaked and dehydrated according to Sally Fallon’s instructions); homemade muffins with raisins, apples, bananas, and nuts; French toast with cinnamon and honey or maple syrup; and so forth.

Additionally, patients with a chronic tonsil focus need to supplement their often-depleted digestive functioning with a quality enzyme supplement. For those individuals with a major rheumatic gut disturbed field, their chronically irritated stomach and small intestine mucosas require the gentle supplementation of a hydrochloric-acid-free and protease-free enzyme, such as Gastric Comfort (601) from Enzymes, Inc. Those with no significant history of ulcers, gastritis, or stomach or intestinal pain may choose to supplement with Dipan 9 from Thorne.

Gastric Comfort, aka 601, is available from Enzymes, Inc., at (800) 637-7893. Dipan 9 is available from Thorne at (800) 228-1966.

Gastric Comfort, aka 601, is available from Enzymes, Inc., at (800) 637-7893. Dipan 9 is available from Thorne at (800) 228-1966.

2. Drainage

Gemmotherapy (plant stem cell) drainage remedies are essential components in the treatment of tonsil foci. Often basic drainage for the liver with Juniper (Juniperus communis) or Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis); the kidneys with Juniper or White Birch (Betula pubescens); and the pancreas, stomach, and small intestine with Fig (Ficus carica) or European Alder (Alnus glutinosa) is sufficient. However, specific drainage for the tonsils is also often needed.

White Willow (Salix alba), which is both antiinflammatory and analgesic (pain relieving), makes an excellent gargle for painful throats. Another remedy indicated for tonsillitis is Black Poplar (Populus nigra), especially in cases with mercury amalgam fillings (past or present). The excellent Silver Fir (Abies pectinata) remedy is used most often in pediatric patients to treat tonsillitis, especially for children who suffer from chronic infections. It additionally helps remineralize bones and teeth, reducing dental cavities, strengthening the enamel, and therefore preventing future potential dental focal infections.

Specific drainage for rheumatic disturbed fields such as the joints with Mountain Pine (Pinus montana), the heart with Hawthorne (Crataegus oxyacantha), and the brain with Olive (Olea europaea) or Linden Tree (Tilia tomentosa) may also be indicated.

Gemmotherapy remedies are available from PSC Distribution at (631) 477-6696 or www.epsce.com and from Gemmos LLC at (877) 417-6298 or www.gemmos-usa.com.

Gemmotherapy remedies are available from PSC Distribution at (631) 477-6696 or www.epsce.com and from Gemmos LLC at (877) 417-6298 or www.gemmos-usa.com.

Natural drainage through the normal emunctories in the head—that is, through the various orifices—can also be enhanced. When toxins are released from the brain and face while the patient is receiving appropriate treatment, itching and redness may occur in the eyes, ears, nose, and throat. This is usually a positive sign, indicating that the prescribed drainage remedies, constitutional homeopathy, auriculotherapy, and other holistic treatments are working and releasing toxic metals or microbes.XXIII To facilitate this transport, use an eyewash with eyebright (Euphrasia officinalis) herbal drops diluted with water in an eyecup, ear drops (e.g., mullein and garlic in olive oil), nasal and sinus washes (neti pots), and Karach’s oil treatment for throat and tonsil detoxification (all available from health food stores).XXIV Colonics or home enemas may also be indicated during this period.

EAR DRAINAGE/BRAIN FUNCTION CONNECTION IN ANIMALS

Holistic veterinarian Don Hamilton has noticed this phenomenon in animals. In his book Homeopathic Care for Cats and Dogs, he observes:

There is an observed connection between the ears and the brain. Suppressed ear disease can lead to brain problems—and curative treatment of brain disease may be followed by an ear discharge. Suppressive treatment of the discharge may reawaken the brain illness.97

Finally, drinking adequate amounts of pure water (according to thirst) can further augment natural physiological drainage during this period. And since the tonsillar tissue in a focal infection is always (subtly or not-so-subtly) chronically inflamed, adequate pure water intake can reduce this heat, as well as dilute and help expel surface microbes. However, water should not be drunk in excess at meals to prevent diluting the stomach and intestinal juices and impairing efficient digestion.

Effective reverse-osmosis water purifiers can be ordered from Radiant Life at (888) 593-8333, or go to www.radiantlifecatalog.com, and from Mary Cordaro at www.marycordaro.com.

Effective reverse-osmosis water purifiers can be ordered from Radiant Life at (888) 593-8333, or go to www.radiantlifecatalog.com, and from Mary Cordaro at www.marycordaro.com.

3. Neural Therapy

The treatment of the tonsil focus through various neural therapy methods has been successfully utilized for almost a century. In children as well as adults with acute inflammation of this chronic focus, isopathic remedies can be very effective. For example, the SanPharma isopathic fungal remedy Notatum 4X, known in holistic circles as a “natural antibiotic,” can significantly reduce strep and staph bacterial infections without any of the side effects that antibiotics create. Notatum 4X drops or the stronger 3X tablets are often indicated for acute tonsillitis or when a chronic tonsil focus acutely flares up.