3.1 Origin

3.2 Energy Distribution

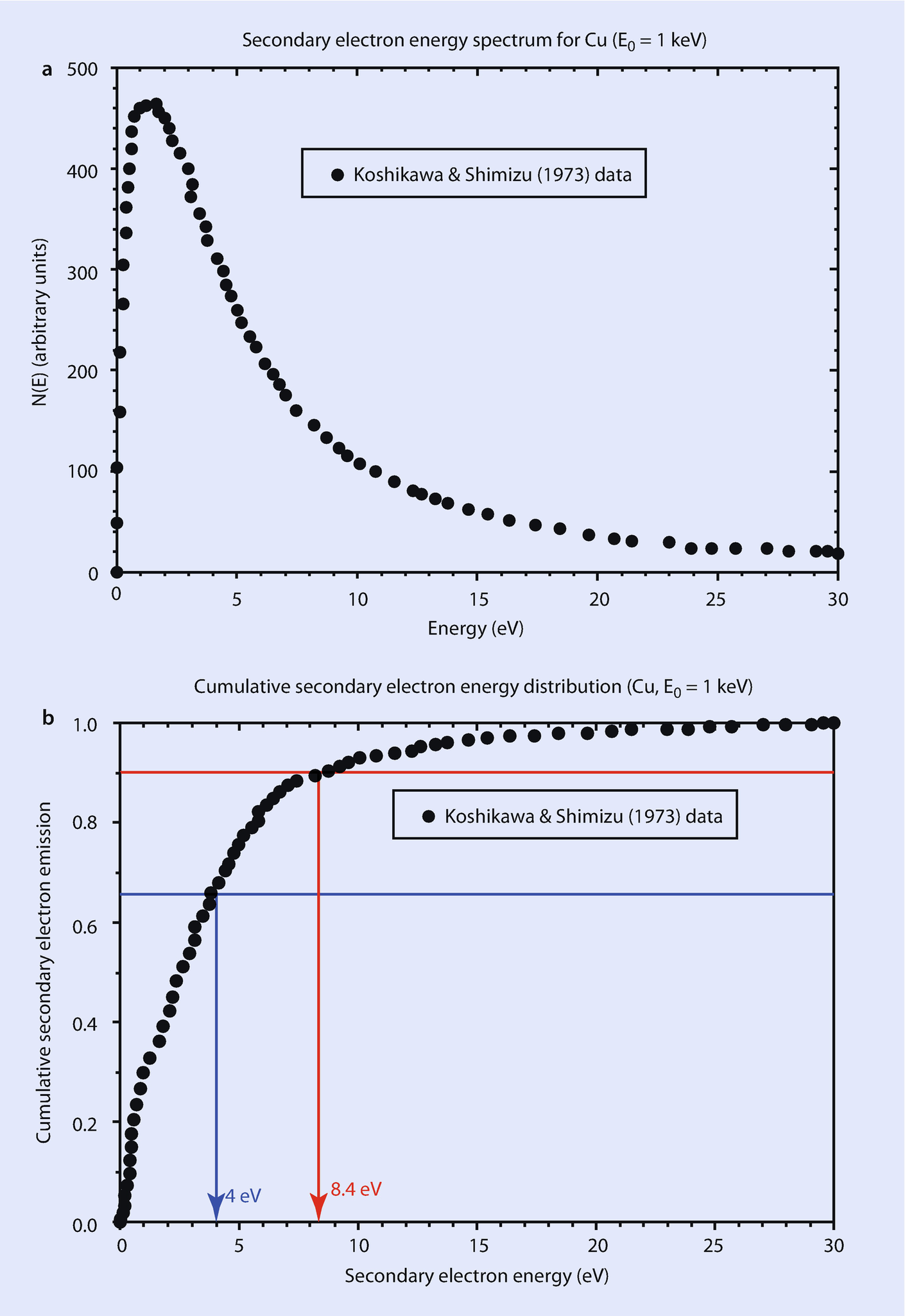

a Secondary electron energy spectrum for copper with an incident beam energy of E0 = 1 keV (Koshikawa and Shimizu 1973). b (Data from ◘ Fig. 3.1a replotted as the cumulative energy distribution)

3.3 Escape Depth of Secondary Electrons

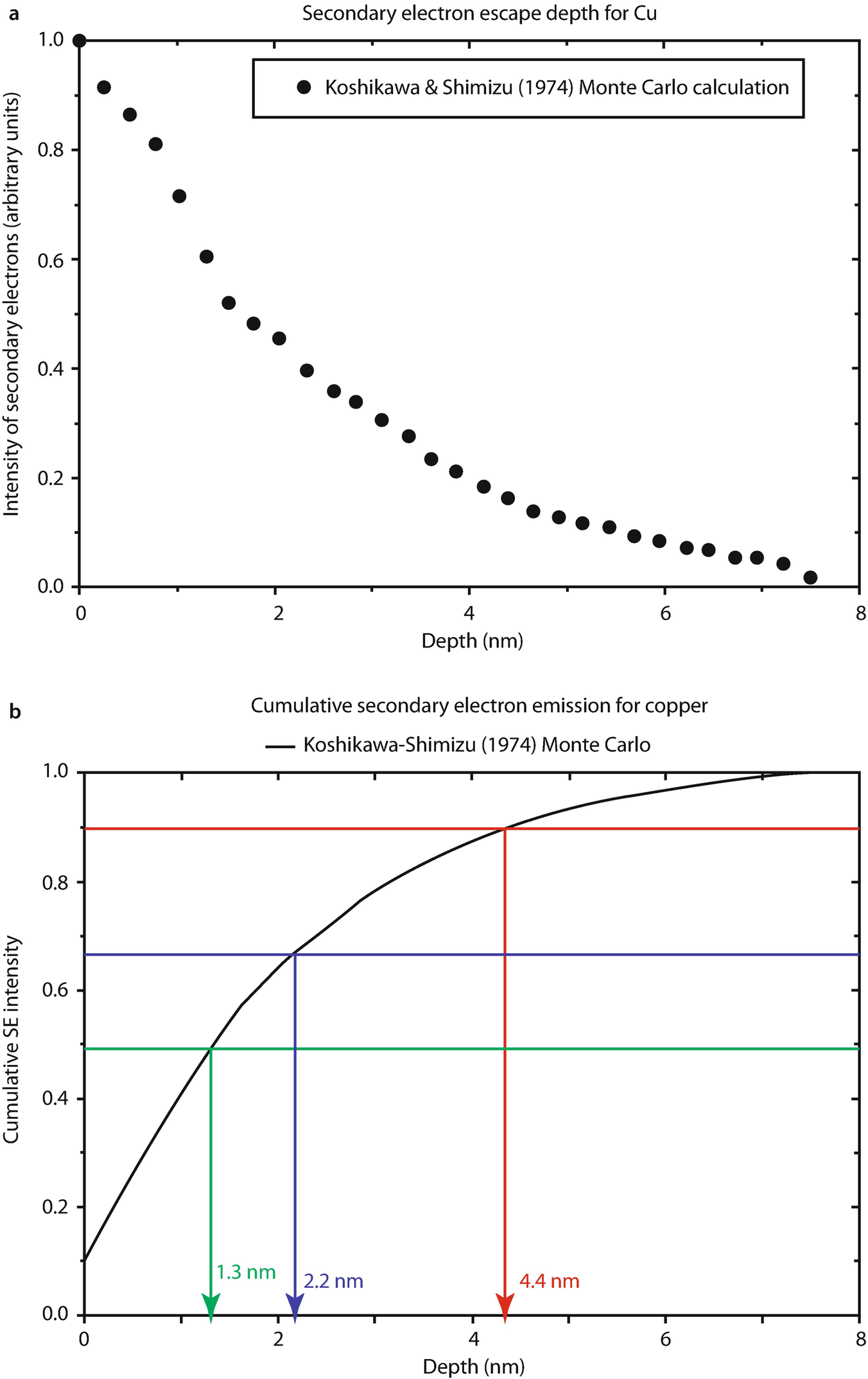

a Escape of secondary electrons from copper as a function of generation depth from Monte Carlo simulation (Koshikawa and Shimizu 1974). b (Data from ◘ Fig. 3.2a replotted to show the cumulative escape of secondary electrons as a function of depth of generation)

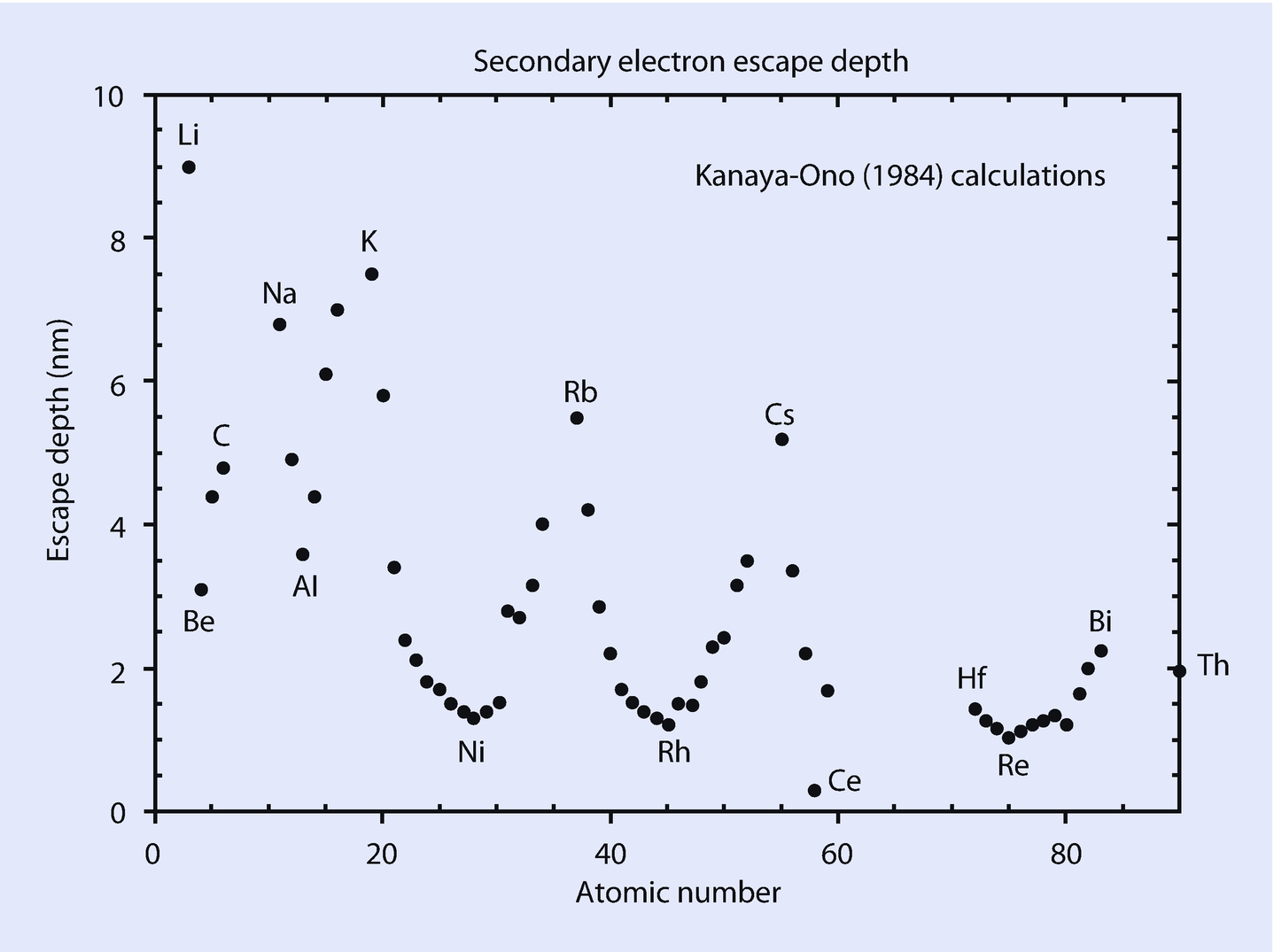

Mean secondary electron escape depth for various materials as modeled by Kanaya and Ono (1984)

3.4 Secondary Electron Yield Versus Atomic Number

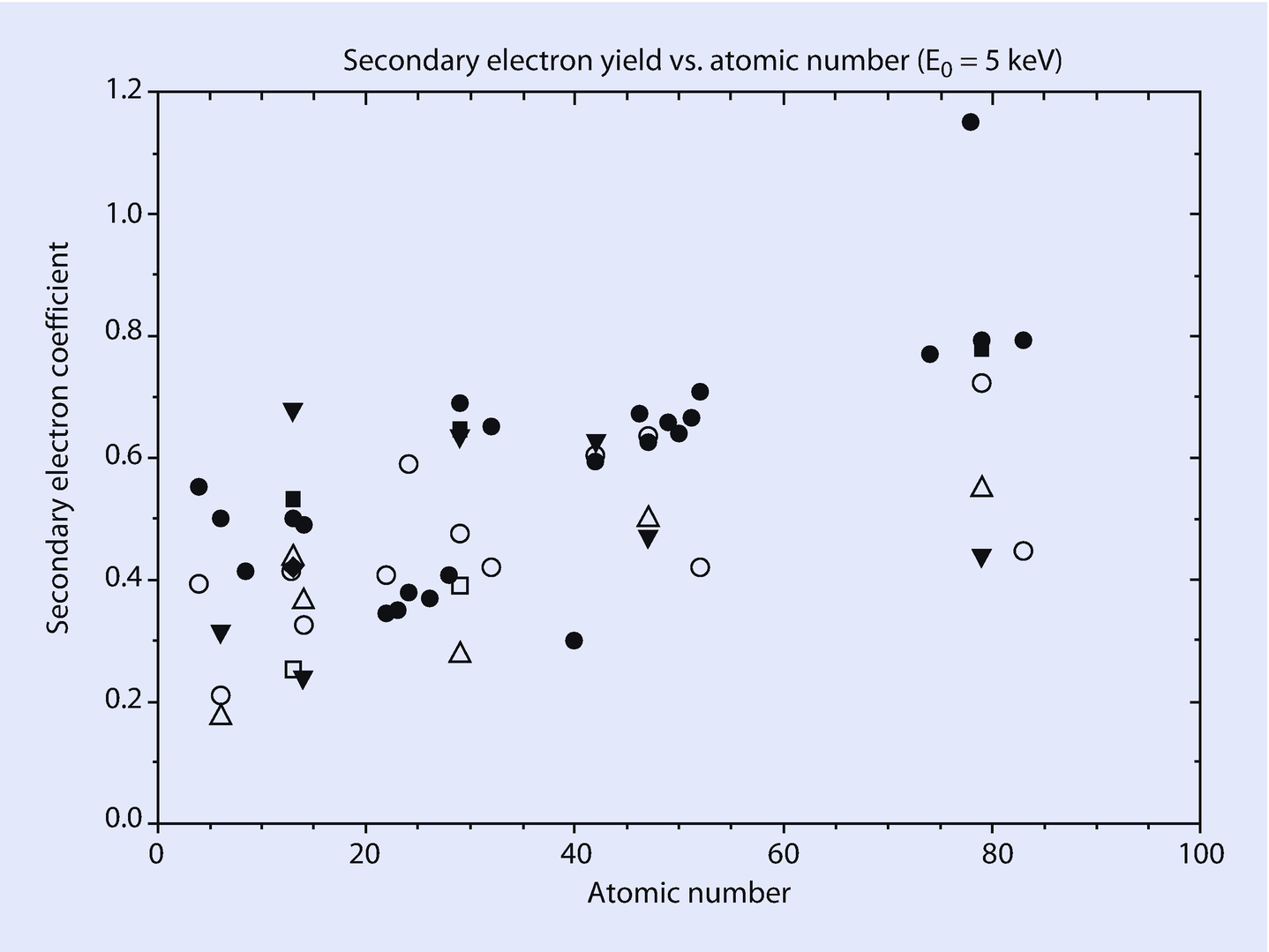

Secondary electron coefficient as a function of atomic number for E0 = 5 keV (Data from the secondary electron database of Joy (2012))

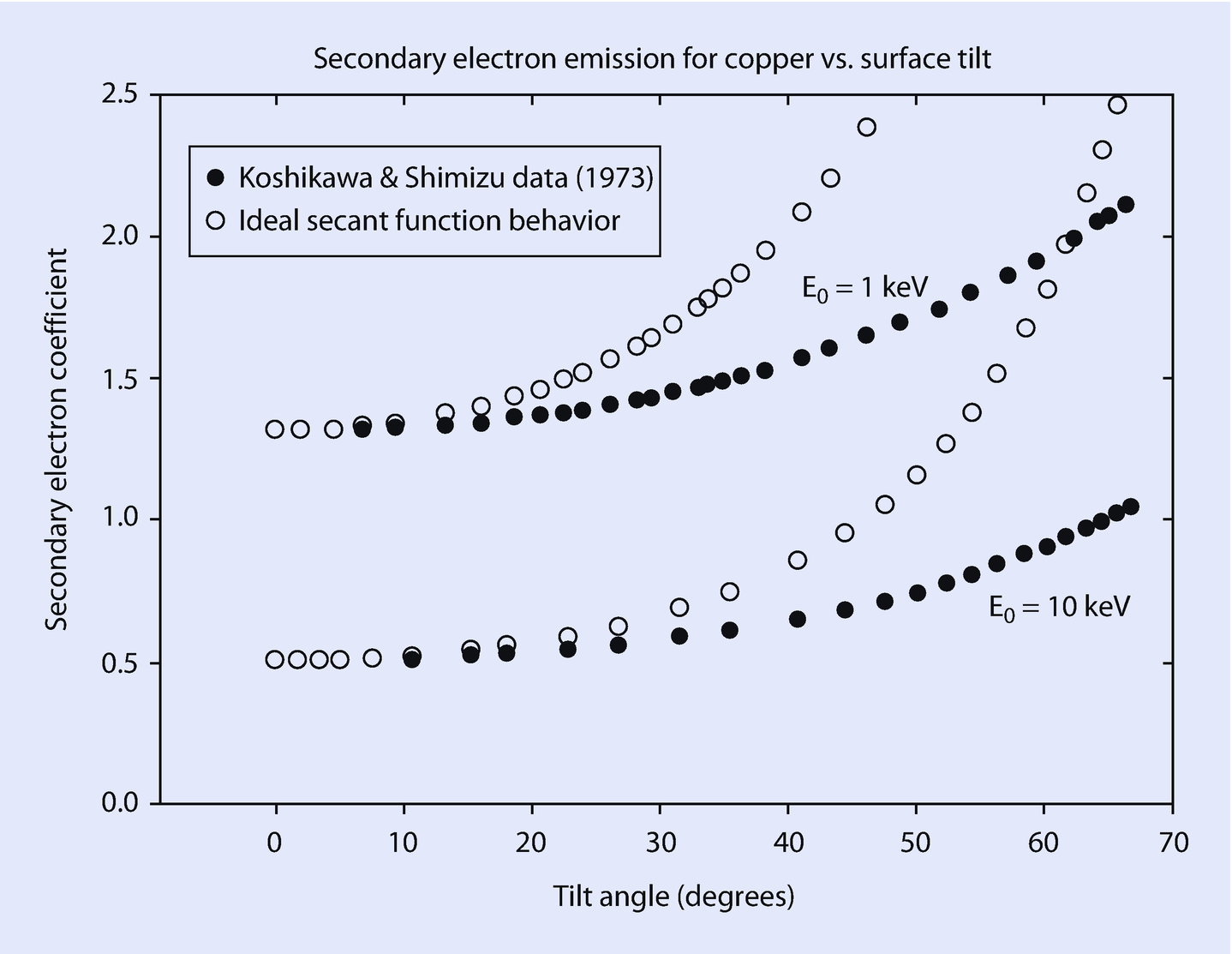

3.5 Secondary Electron Yield Versus Specimen Tilt

Behavior of the secondary electron coefficient as a function of surface tilt (Data of Koshikawa and Shimizu (1973)) showing a monotonic increase with tilt angle but at a much slower rate than would be predicted by a secant function

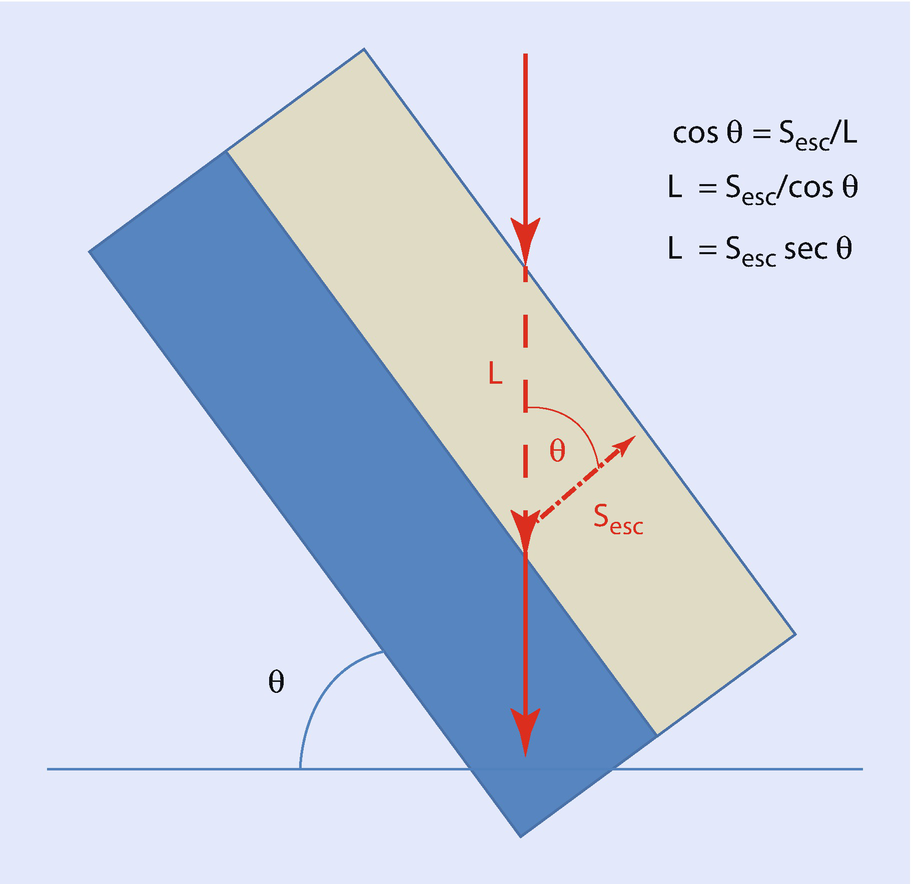

Simple geometric argument predicting that the secondary electron coefficient should follow a secant function of the tilt angle

The monotonic dependence of the secondary electron coefficient on the local surface inclination is an important factor in producing topographic contrast that reveals the shape of an object.

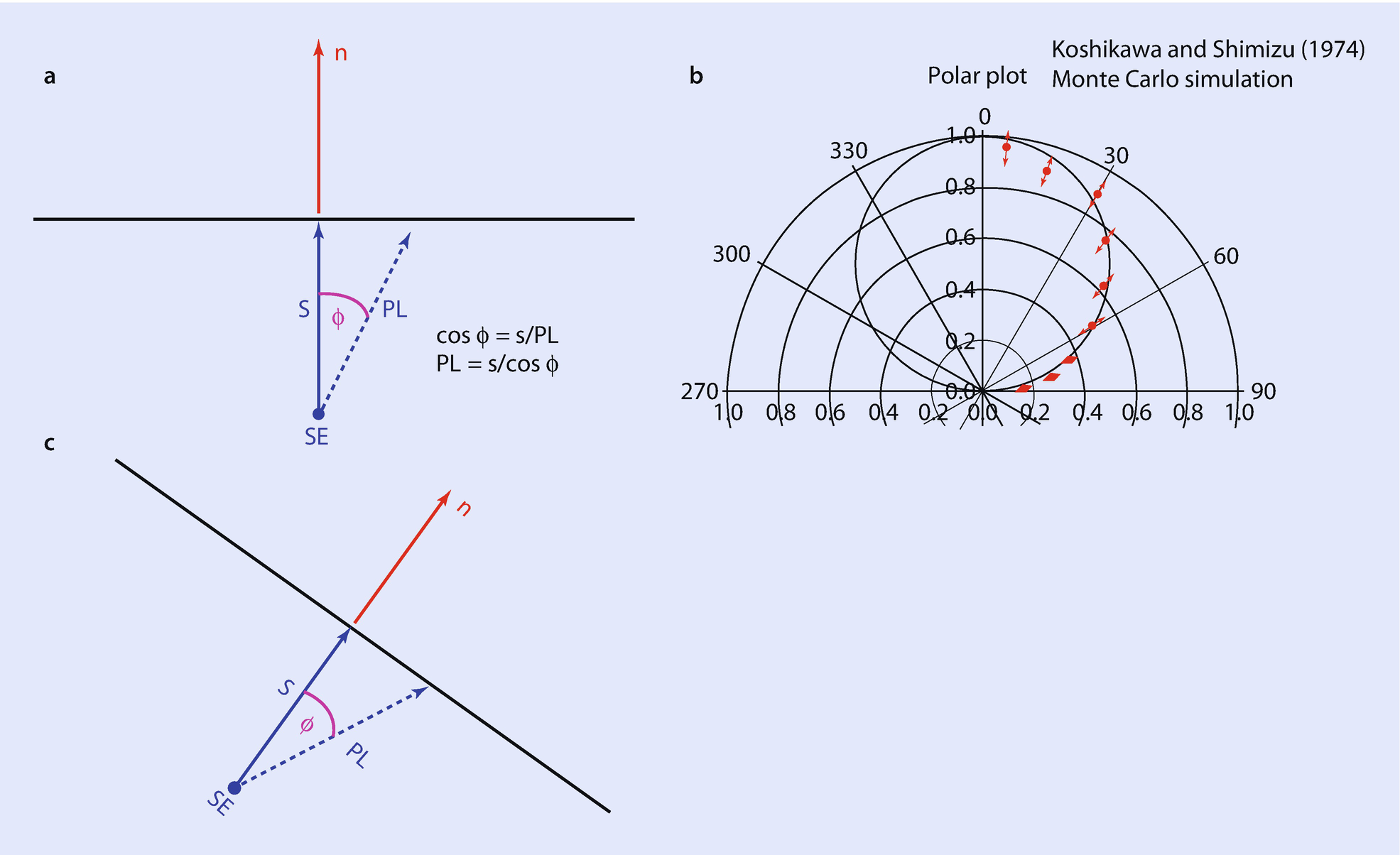

3.6 Angular Distribution of Secondary Electrons

a Dependence of the secondary electron escape path length on the angle relative to the surface normal. The probability of escape decreases as this path length increases. b Angular distribution of secondary electrons as a function of the angle relative to the surface normal as simulated by Monte Carlo calculations (Koshikawa and Shimizu 1974) compared to a cosine function. c The escape path length situation of ◘ Fig. 3.7a for the case of a tilted specimen. A cosine dependence relative to the surface normal is again predicted

Even when the surface is highly tilted relative to the beam, the escape path length situation for a secondary electron generated below the surface is identical to the case for normal beam incidence, as shown in ◘ Fig. 3.7c. Thus, the secondary electron trajectories follow a cosine distribution relative to the local surface normal regardless of the specimen tilt.

3.7 Secondary Electron Yield Versus Beam Energy

a Behavior of the secondary electron coefficient as a function of incident beam energy for the conventional beam energy range, E0 = 5–30 keV (Data of Moncrieff and Barker (1976)). b Behavior of the secondary electron coefficient as a function of incident beam energy for the low beam energy range, E0 < 5 keV (data) (Data of Bongeler et al. (1993)). c Dependence of the secondary electron coefficient on incident beam energy for C, Al, Cu, Ag, and Au (Reimer and Tolkamp 1980)

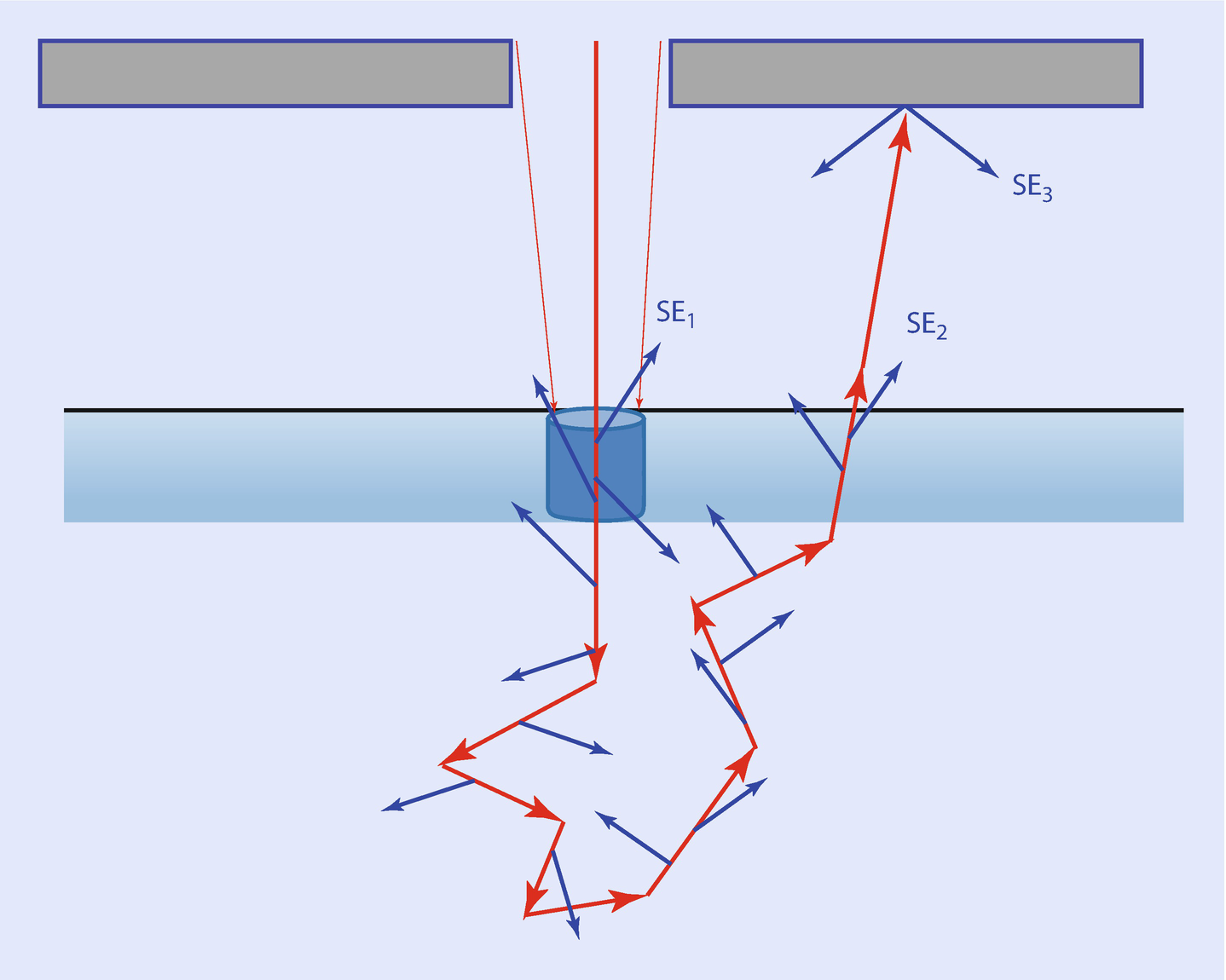

3.8 Spatial Characteristics of Secondary Electrons

Schematic diagram showing the origins of the SE1, SE2, and SE3 classes of secondary electrons. The SE1 class carries the lateral and near-surface spatial information defined by the incident beam, while the SE2 and SE3 classes actually carry backscattered electron information. The blue rectangle represents the escape depth for SE, and the cylinder represents the volume from which the SE1 escape

Incident beam footprint, high resolution, SE1 (9 %)

BSE generated at specimen, low resolution, SE2 (28 %)

BSE generated remotely on lens, chamber walls, SE3 (61 %)

A small SE contribution designated the SE4 class arises from pre-specimen instrumental sources such as the final aperture (2 %) that depends in detail on the instrument construction (apertures, magnetic fields, etc.). These measurements show that for gold the sum of the SE2 and SE3 classes which actually carry BSE is nearly ten times larger than the high resolution, high surface sensitivity SE1 component. These three classes of secondary electrons influence SEM images of compositional structures and topographic structures in complex ways. The appearance of the SE image of a structure depends on the details of the secondary electron emission and the properties of the secondary electron detector used to capture the signal, as discussed in detail in the image formation module.

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.5 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.5/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.