A Short History

The word athame is of fairly recent vintage, appearing in print for the first time in 1949. That appearance was not in a how-to or history book, but in a fiction novel, written by Gerald Gardner. High Magic’s Aid is not a great book, but it’s an important one and contains the first somewhat recognizable modern Witch rituals. The athame figures prominently in all of the book’s rituals and has been a vital part of modern Witchcraft ever since.

Gardner’s inclusion of a ceremonial knife in his text would not have surprised anyone back in 1949; however, his use of the word athame most likely would have. Athame as a word didn’t exist before Gardner (and/or his initiators), though there are several words that are similar. Most of these “variant spellings” are found in various French translations of the Key of Solomon. (The Key of Solomon is a very influential Italian Renaissance–era grimoire, misattributed to the biblical king Solomon and originally written in Latin.)

The words artave, arthane, and arthame all appear in the many different French translations of the Key of Solomon, and they are all probably a garbled mistranslation of the Latin word artavus. Artavus doesn’t have any deep connection to the realms of magick and Witchcraft, but it does describe a particular type of knife. Artavus was a Medieval Latin word that translates as “penknife” and has been described as a “small knife used for sharpening the pens of scribes.” 1

The 1927 book The Mysteries and Secrets of Magic draws heavily from the Key of Solomon and includes two words very similar to athame. The first appears in an illustration of swords, labeled as an arthany. In the same chapter, the author (C. J. S. Thompson) also mentions the arthana (knife) as a primary magical tool. Curiously, Thompson’s swords are never to be “occupied in any work,” while his arthana is used explicitly for the physical act of cutting. He also includes specific instructions for a white-handled knife that most likely influenced the development of the boline (see chapter 6).

The word arthame shows up in the French book Witchcraft, Magic, and Alchemy by Grillot de Givry, which was published in 1929 (an English translation would show up two years later). De Givry’s book most likely had some impact on those interested in the occult because the word arthame was subsequently picked up by at least one English writer. In his short story The Master of the Crabs, horror writer Clark Ashton Smith uses the word arthame to describe a magical knife. Smith’s story was released in 1948, just one year before Gardner’s High Magic’s Aid.

There are several other words with spellings close to athame that may have influenced Gardner’s word choice back in 1949. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, attame (or atame) is an Old French word that means “to cut or pierce,” and might have influenced all the different translation versions of artavus that appear in French versions of the Key of Solomon.2 Idries Shah (Arkon Daraul), a contemporary of Gardner and most likely his first biographer, speculated in his book Secret Societies (1961) that the word athame might derive from the Arabic term al-dhamme, which translates as “blood-letter.”3 Even less likely as a possible origin, but still worth mentioning, is the word athemay, which appears in the 1801 work The Magus, where the word is used to refer to the sun.

In the end, all or none of these words might have influenced Gardner to choose the word athame for his novel. I’m of the opinion that athame is most likely a misspelling of arthana, though there’s no way of knowing for sure. It’s worth noting that Gardner himself was a fan and collector of knives, even writing a book in 1939 on the Malay kris (an Indonesian dagger with a wavy blade). Some of Gardner’s critics have used this to suggest that Gardner “made up” the idea of using a magical knife in ritual. On that point they are most definitely wrong.

Knives in Ritual and Religion

Knives have been in existence for millions of years. Before modern humans walked the earth, our genetic ancestors were using knives. No one is quite sure when the first knife was actually used, but estimates range from one million years to perhaps two and a half million years ago. The earliest knives were made of stone and probably used mostly for scraping animal remains.

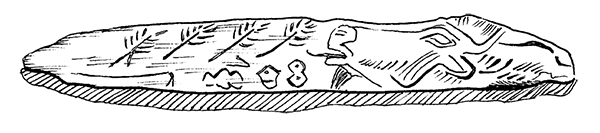

Modern human beings have been using knives since the beginning of our existence, somewhere between 50,000 and 100,000 years ago. Two bone knives found at the Grotte de la Vache (“Cave of the Cow”) in Southern France suggest that early humans began using knives for spiritual and religious purposes as early as 12,000 to 15,000 years ago. 4 The two knives found there contain carvings on their blades that seem to reflect spring and autumn. The autumn blade shows a rutting bison, a few seeds, some branches, and a wilting plant. The spring knife contains the figure of a doe and several wavy lines that may imply water.

The bone-knives from Grotte de la Vache are extraordinary for more than the carvings. What makes them really special is that they seem to have never been used for cutting or any other physical purpose. We have no real way of knowing exactly what these knives were used for, but their lack of physical use makes it likely that they were used for some sort of spiritual purpose.

By the year 4500 BCE, knives were being used ceremonially in Pre-dynastic Egypt. Flint knives were used to make sacrifices to the gods and were often elaborately decorated. The Pitt-Rivers knife found in Egypt (named after its owner, English Lieutenant-General Henry Fox Pitt-Rivers), dating from between 3600 to 3350 BCE, was elaborately carved and features over eleven different animals on its blade. 5 Such elaborately carved knives were coveted status symbols in ancient Egypt. Knives never used for cutting were often buried with the Egyptian dead.

Bone knife

Bone knife

In Bronze Age Britain (2500 to 800 BCE), daggers were generally buried with the dead. Oddly, the era’s other most common tool, the ax, was never buried with the dead. Knives must have had a much higher level of significance. Daggers were also sometimes placed in streams, bogs, and other bodies of water for some sort of undetermined ritual and/or spiritual purpose.

For our purposes, the most significant use of knives in ritual and ceremony comes from the European grimoire tradition. Grimoires (which really just means “magick books”) have been around since the ancient Greeks and Egyptians, but really came into their own during the European Renaissance after the advent of the printing press. The most popular and influential grimoire from this period was the Key of Solomon (first showing up in Greek in the fifteenth century), and it included a black-handled knife among its working tools.

The Key of Solomon wasn’t the first book to mention a knife as a working tool. That honor belongs to the Grimoire of Honorius, which dates back to the thirteenth century. The rituals contained in texts such as Honorius and Solomon bear a striking similarity to those of modern Witchcraft. Magick circles are cast and directions are invoked, which means various magicians have been using knives much like we do for at least eight hundred years now, and possibly much longer. Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Jewish grimoires also reference black-handled knives, and there is some indication that the references date back even further to the eleventh century. Those grimoires did not generally call for the use of a ritual knife, but the sword appears often in the symbolism of the Jewish Kabala.

The black-handled knife appearing in the pages of the Key of Solomon meant that its use would merit mention in nearly any treatise on magick and the occult. Books on magick for general audiences have been popular since the invention of the printing press, which means magical knives show up in various odd corners of world history. Joseph Smith, the founder of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (the Mormons), used his family’s ceremonial dagger to cast magic circles on treasure-hunting expeditions.6

Perhaps the most curious reference to the black-handled knife comes from the Dublin University Magazine back in 1849, where the following information appears in a footnote:

A black-handled knife is an indispensable instrument in performing certain rites, and we shall have occasion to describe its virtues by-and-by. It is employed in the ceremonial of Hallow-Eve, and also in the mystic ceremonies performed at the rising of the new moon, as well as in certain diabolic mysteries made use of to include love, etc. 7

Even if the word athame is of fairly recent vintage, the knife as a magical instrument has a long and distinguished history. Every time we pick up our athames, we are partaking in a religious tradition that stretches back into human pre-history. The knives of our ancestors didn’t always look the same as our modern blades, but it’s possible that they were being used for similar purposes. It’s strange to think about it this way, but the knife might very well be the oldest continually used tool currently on the Witch’s altar!

The Black-Handled Knife

Today athame handles come in all sorts of colors and are made from a variety of materials (both natural and synthetic), but traditionally the handle is made of wood and is black. I originally found this to be a strange tradition, but it does have historical precedent and some practical advantages. Much of the black blade’s historicity comes from the Key of Solomon. Since its original composition, it has remained a staple in the library of most magicians (and even many Witches). Everything in the Key of Solomon has been retransmitted numerous times, including references to the black-handled knife.

The use of wood in the hilts of ceremonial daggers was most likely the result of sheer practicality. The majority of daggers made during the Renaissance and Middle Ages had wooden handles. Wood was simply cheaper and more abundant than the alternatives (like metal or ivory). The only odd thing about a “black wooden handle” is that wood generally doesn’t come in black. To get a black wooden handle one generally has to paint or stain the blade’s hilt.

One of the most intriguing explanations I’ve read for the black handle is that wooden hilts were generally stained black by the blood of ritual magicians. Apparently many of those magicians were nicking their palms to draw blood for various magical purposes. When that blood was absorbed by the knife’s wooden handle, it would turn the hilt black. I’ve always found that explanation a bit macabre, but it’s certainly possible.

The color black has a practical application too: it absorbs energy better than any other color. By using a black-handled knife, the Witch can more easily “set aside” a little energy for later use. The handle isn’t going to absorb copious amounts of energy, but sometimes every little bit helps. It’s even possible to direct extra energy raised in ritual directly back into the athame. Think of it as a spiritual battery located conveniently in one of your primary working tools!

Why a Doubled-Edged Blade?

I think much of the history of the athame is rather straightforward. As we’ve seen, knives with black handles have long been a part of the magical tradition. The word athame is a little newer, but there are words quite similar to it dating back centuries. What I’ve had more trouble with is figuring out exactly why the traditional blade has a double edge.

The grimoire tradition that gave birth to the athame features several different types and styles of knives. Most versions of the Key of Solomon feature mainly double-edged blades in their illustrations. When a single-edged blade is shown, it’s generally an outlier. The arthany pictured in C. J. S. Thompson’s more contemporary The Mysteries and Secrets of Magic has a curved single-edged blade, and he also includes an equal number of single-edged and double-edged blades.

I think the reason the athame is traditionally double-

edged is because the majority of daggers and knives in ritual books were depicted that way. It might also be because a double-edged blade looks more like a mini-sword than a knife with a curved blade. Since the sword and athame are often used interchangeably in ritual, it makes sense for them to be constructed in a similar fashion.

Over the last one hundred years, the definition of dagger has come to refer to a double-edged knife with a pointy end. Since ceremonial knives are often called daggers, it makes sense for them to resemble our modern interpretation of the dagger. (There are some traditional daggers with single-edged blades, but those are the exception and are usually found outside of Europe.) Daggers are also often seen as more exciting than the rather utilitarian knife, and what could be more exciting than a ritual blade used for magical work?

There’s also a practical reason for the double-edged blade, and it’s something I think about every time I consider a curved blade for use as an athame. The athame is designed to project energy. Energy, like most things, takes the path of least resistance. With a double-edged blade, there is no path of least resistance; energy travels equally through every part of the blade. With a single-edged knife, energy is not going to be distributed through the blade equally.

I know many people who use an athame with a single edge and they have no trouble projecting energy and doing good work in circle. However, I think the unequal distribution of energy through the blade would be something I couldn’t overcome. It would bug me constantly. If you find a blade you like with a single edge, by all means use it. Just realize that it might give you some trouble when you project energy out of it.

Knife Superstitions

There are a whole host of superstitious beliefs attached to knives, so be careful when giving a knife as a gift or when letting someone else use your athame. Many of the superstitions involving knives are related directly to their use as cutting tools. Receiving the gift of a knife will often result in the severing of a friendship. When a knife is received from a lover, it is a sign that the relationship will soon come to an end.

If someone you love does give you a knife (or a new athame) as a gift, there is a way to reverse the friendship curse. Simply hand the gift-giver a token of appreciation “in payment” for the knife. This is said to restore the bonds that might otherwise have been severed by the knife’s blade. It’s considered unlucky to close an open pocketknife that has been opened by someone else. Similarly, sheathing a knife you didn’t draw is also bad luck.

Knives have also been said to have the ability to affect the weather. As early as 1727, written reports detail how Mediterranean sailors used daggers to break up heavy winds and even ward off tornadoes.8 I know a few Witches who use their blades while practicing weather magick, and this feels similar.

There’s a long tradition of metal objects serving as deterrents against malevolent forces. The best-known object in this category is the “lucky” horseshoe, but knives play into this belief as well. The demons of northern India are apparently so stupid that they will simply run into a naked blade and cut themselves. Knives have also been used throughout Europe to ward off evil spirits. Placing a knife in the bottom of a boat will keep evil spirits away and ensure smooth sailing (or rowing). Filling a large jar with water and placing a knife inside of it is said to repel the Devil. Allegedly, Satan gets so focused on looking at his reflection that he forgets to bother people. Black-handled knives were also used to keep evil Irish fairies at bay as recently as the nineteenth century.

A Jewish superstition calls for the separation of religious books and iron implements such as knives. Books are thought to preserve lives, while iron ends them. Additionally, knives should never be used to help read a religious text. My athame is often near my Book of Shadows, and they have probably rubbed against each other at least once or twice.

There are several superstitions related to dropping a knife, many of them contradictory. A knife sticking into the ground point first and hilt up can mean good luck or that you will soon be dead. Another legend says that a dropped knife means unexpected company will soon be arriving. The direction in which the dropped knife points will be the direction from which they come. In Finland, there are several “dropped knife” superstitions related to fish. If a knife is dropped while cleaning fish and it points toward the sea, good fishing is assured on the fisherman’s next trip. If it points toward land, the next expedition will end in failure.

Not all the superstitions surrounding knives are bad. Placing a knife under the bed of a woman giving birth is said to help with pain, the idea here probably being that the knife will absorb the pain so it no longer troubles the mother-to-be. An athame in tune with a Witch giving birth will probably be even more effective at channeling away some of that pain. In some parts of Europe, knives were placed directly in a baby’s crib to ward off evil spirits. (That’s one I don’t want to try at home.)

In Greece, knives are often placed under pillows to ward off bad dreams. It doesn’t sound like the safest practice to me, but if I was being plagued by nightmares, there’s nothing I would want more in dreamscape than my athame. In addition to warding off bad dreams, knives in Greece were sometimes used to rid homes of insects. I don’t understand the reasoning behind this, unless of course they rid the house of insects by stabbing each one individually.

Because metal was so precious and magical in the ancient world, oaths were often taken upon knives. The next time you or a friend has to “swear to” do something, do it while holding an athame. That will hold both of you to your promise.

Native American Knife Lore

Pagan and magical histories often exclude Native American legends and traditions. It’s a serious oversight because modern Witchcraft has been tremendously influenced by Native American spiritualities. All of the Witches out there who use smudge sticks owe their Native American friends a hearty thank-you. In addition, nearly all the information we have about plants and stones native to the Americas initially came from Native Americans.

While I don’t know of any traditions involving the athame that came directly from America’s first inhabitants, Native Americans do have several interesting legends and customs involving the knife. They’ve also been using knives nearly as long as Europeans, and have used a wide variety of knife types over the last twelve thousand years, too. Native American knife blades have been made of wood, shell, horn, bone, teeth, copper, and even meteoric iron!

Contrary to popular belief, metallurgy existed in the Americas before the arrival of Europeans. Native metallurgists possessed exceptional skill and were as advanced as their European counterparts; however, most Native American societies used their knowledge to achieve different ends. Empires like that of the South American Inca preferred to craft ornamental items instead of weapons.9

One of the reasons we seldom associate America’s original inhabitants with metallurgy is that they most often worked with copper. Copper is a beautiful decorative metal and can be quite useful; however, it’s a very soft metal. Metal knives became more common in North America once Native Americans had access to iron. Eventually they became quite adept at making knives from bayonet blades, iron files, and other metal scraps.

For Northern California’s Hupa tribe (also sometimes spelled Hoopa), knives were a symbol of wealth and social status. Ornate obsidian knives used only in ritual were sometimes up to twenty inches long and two and a half inches wide. If I saw a knife like that in circle, I wouldn’t automatically start thinking of social status, but I would be suitably impressed.

Other tribes used knives to indicate social standing too, but the Ojibwe (known by many as the Chippewa) and Sioux of the American West and Midwest wore theirs. Many in these two tribes placed sheathed knives around their necks to indicate wealth. Larger knives indicated greater amounts of wealth. Triangular knives were later worn around the necks of Sioux leaders to indicate rank.10

Plains tribes in what is now Missouri used to swear on their knives in a threefold ritual. They’d begin by holding a knife in their right hand raised up toward the sun while reciting an oath. They would then lower the knife and place it between their lips and finally on their tongue.11

Perhaps the most fearsome knife (and ceremony) among the natives of North America was known as the Blackfoot Bear Knife Bundle. Common among the Blackfoot (Niitsitapi) tribes, the Bear Knife Bundle featured a large knife with a bear skull attached to the handle. The knives themselves inspired a great deal of fear, and as a result, their owners were largely left alone. Part of that might also be because the initiation ceremony for the Bear Knife Bundle is rather extreme.

To receive a Bear Knife Bundle, the initiate is required to catch the knife when it’s thrown at him. After catching the knife, the initiate is then “cast naked upon thorns and held there while painted and beaten thoroughly with the flat of the knife.” 12 It’s no wonder that individuals who survived the ordeal were given a wide berth in their communities. I’m glad that I avoided such obstacles when I obtained my athame.

Athame Correspondences

Most Witches honor the elements of earth, air, fire, and water and associate many of their magical tools with one of those elements. Often the association between element and tool is obvious. The cup or chalice is designed to hold water, so the cup is naturally an expression of water. Incense smoke wafts through the air and thus is associated with the element of air. Salt is used by many Witches for cleansing and is most always linked to the element of earth. Since salt is often mined from the earth, this association makes sense to most of us.

I have always associated the athame (and, by extension, the sword) with the element of fire, but there is some disagreement about this among Witches and other magical practitioners. Depending on the tradition and the individual Witch, the athame is sometimes linked to the element of air. This association comes from the nineteenth-century magical order the Golden Dawn, one of the most important occult orders in history. In the symbology of the Golden Dawn, the wand is considered a tool of fire and the knife of air. Many famous Witches have maintained this association, most notably Doreen Valiente, considered by many to be the “mother of modern Witchcraft.”13

On some levels, the association with air makes a great deal of sense. Since the athame is rarely if ever used for physical cutting, it must only be cutting through the air. We certainly aren’t using our blades to cut through gods or spirits. The element of air is often associated with creativity and communication, two things that are important during Wiccan ritual. Without a degree of creativity and imagination, we’d be unable to see the magick circle that surrounds so many of us in our rites. Communication is also a vital skill in Witchcraft. If we are unable to articulate our desires, they will never manifest. It’s also important that we communicate properly to the entities we want to have join us in circle. If holding an athame makes someone a better communicator, maybe its energies are aligned with air after all.

What element a ritual tool is associated with may not seem all that important in the long run, but how we perceive a tool controls a lot of how we interact with it. I associate my athame with the element of fire because the things I do with it during ritual are linked to modern Witchcraft’s perception of that element. When I cast a ritual circle, I’m not just moving around energy; I’m creating a new space between the worlds. There’s a line spoken in some circle castings that states: “We are in a time that is not a time and a place that is not a place.” When I use my athame to create a circle, I am transforming the space I stand in into something else entirely.

Fire consumes and changes all that it touches. Once something has been touched by flame and heat, it will never be as it once was. When I purify and bless items with my athame, I’m fundamentally changing them. A bowl of salt used in ritual is often purified with the athame; that purification drives all “uncleanliness” from the salt, changing it. I do the same with water, and when I make the consumption of bread and wine truly sacred, I do so by touching them with my athame. For me, the athame is the tool of transformation during ritual. Almost everything that changes during my rites as a Witch has been touched by a blade.

Many Witches also view the athame as a tool for channeling one’s magical will. Magical will is the sum total of our interactions with those around us, the gods, and the earth. When we do positive things, we add to our will. Just like a fire grows when you add more wood to it, the will grows when we engage in positive experiences. We can also add to our magical will by believing in ourselves. A good Witch is determined and steadfast—more qualities that add to one’s collective will.

Our actions add to our will, but they are not what allow us to use this personal reserve of energy. To tap into our magical will, we have to believe that magick is a real and powerful force. To utilize will, the Witch has to believe that they are capable of creating change and that they can control that change. Witchcraft is not a science experiment; it’s practiced to create specific results. To create “a time that is not a time and a place that is not a place,” we have to know that we are capable of such an action. If our will is full of positive energy and we are convinced of our own power, the world opens up and we can manifest change within it.

Because our magical will allows us to create change, it’s most often associated with the element of fire, another strong reason to associate the athame with that element. The athame serves as a way to release our true will out into the universe and manifest our desire to walk between the worlds. We use the knife to direct our will because the pointy tip is sharp and precise, just like our will should be in order to practice effective magick.

In addition to linking their tools to the four elements, many Witches also link them to the Goddess and the God and female/male energies. This symbolism is most manifest in the ritual of the symbolic Great Rite. The Great Rite is the celebration of two polarities coming together. In many Traditional Witchcraft traditions, this idea is often expressed in the idea of sexual union between a woman and a man. Since sexual coupling is generally not a part of group ritual, the Great Rite is most often celebrated symbolically, with the athame representing the phallus and the cup representing the womb.

In my own personal practice, I don’t tend to think of my athame as “masculine”; I think of it as one half of a whole. The creation of new things and energies generally requires at least two forces to unite. To celebrate the mystery of life requires two active principles. In Witchcraft, these principles are often represented by the chalice and the athame. Thinking of an athame as “masculine” doesn’t suddenly turn it into a penis; it’s still just a tool. But looking at it in such a way helps some to see and experience the truths and mysteries of the natural world. (The Great Rite is explored in more detail in chapter 6.)

1. Sorita d’Este and David Rankine, Wicca: Magickal Beginnings (London: Avalonia, 2008), p. 71.

2. James W. Baker, “White Witches: Historic Fact and Romantic Fantasy,” in Magical Religion and Modern Witchcraft, ed. James R. Lewis (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1996), p. 177.

3. d’Este and Rankine, Wicca: Magickal Beginnings, p. 73.

4. Alexander Marshack, “Exploring the Mind of Ice Age Man,” National Geographic vol. 147, no. 1 (1975), p. 83.

5. All of the Egyptian material in this chapter comes from a morning spent at the British Museum. Most of the tourists there were taking pictures of the Rosetta Stone, while I spent my time photographing flint knives and placards.

6. D. Michael Quinn, Early Mormonism and the Magical World View (Salt Lake City, UT: Signature Books, 1998), p. 71.

7. d’Este and Rankine, Wicca: Magickal Beginnings, pp. 82–83.

8. d’Este and Rankine, Wicca: Magickal Beginnings, p. 84.

9. Charles C. Mann, 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus (New York: Knopf, 2005), pp. 82–83. Mann’s book is endlessly fascinating and one of the most reread books in my house. This is a must-read.

10. Colin F. Taylor, Native American Weapons (Norman,OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2001), p. 37.

11. Ibid., p. 40.

12. Clark Wissler, “Ceremonial Bundles of the Blackfoot Indians,” Anthropological Papers vol. 7, part 2 (New York: American Museum of Natural History, 1912), p. 132.

13. Janet and Stewart Farrar, A Witches’ Bible: The Complete Witches’ Handbook (Custer, WA: Phoenix Publishing, 1996), p. 253. Originally published as The Witches’ Way.