For centuries, the study of Chinese herbal medicine has included beauty as one of the results of good health. The concepts of health and beauty are inseparable, focusing on the total well-being of the body’s internal and external functions. To have optimum health and beauty, a great physique and youthful appearance has to start with the body’s inner health, which includes maintaining the balance of yin and yang, chi, and blood action.

To get the most out of The Tao of Beauty, it is important to understand the underlying principles that inform Chinese thought. Whether we are talking about health or the weather, several important concepts apply. At the top of this list is the principle of the Organic Whole, followed by the theory of Yin and Yang. In addition, there are chi or life force, the Five Elements, nature’s Six Climatic Effects, and the Five Emotions.

Using these special points as an outline for your new venture, I promise that you’ll soon be in touch with your body—and your beauty—like never before.

I come from a family of herbalists, and I’ve heard stories since childhood about the amazing work done by such great pioneers as Emperor Shen Nong, who introduced agriculture to the Chinese people around 3000 B.C.E. According to legend, Shen Nong was intrigued by the vast numbers and varieties of plants around him and began to experiment with herbs. As the first in a long line of Chinese herbal “explorers,” he and his disciples tested thousands of these plants—tasting them, cooking them, and making teas from them. In the process of this delicate, dedicated study, they discovered through shrewd and careful observation, that many of these plants not only tasted good but also enabled people to stay vigorous and strong. The vast variety and effects of these herbs was a challenge to Shen Nong and the long line of others who followed him in this quest. Some herbs induced sleep, others wakefulness; still others eased pain or helped people recover quickly from even the most serious illnesses. They also found that some made the skin soft and beautiful and others enhanced youth and vitality.

These formulations were passed down through the generations and refined until, centuries later, during the reign of Huang Di of the Han dynasty (206 B.C.E.–220 C.E.), this knowledge was collected and incorporated into a book entitled The Yellow Emperor’s Classic Book of Medicine. This is generally recognized as one of the first known formal Chinese medical texts.

My mother, who comes from a long line of Chinese herbalists, is an ardent believer in traditional Chinese medicine. She served my family foods that were in season to maintain balance within us; this kept us healthy and strong. Instead of going to the pharmacy for pills if we were ill, she cooked special dishes that were known to treat whatever was out of balance within us. She brewed special herbal tonics that would strengthen our immune systems or speed up our recovery by helping our bodies renew their internal balance. She also prepared toners, bath salts, and other topical treatments that affected our total well-being and promoted beautiful, glowing skin and strong, shining hair.

Few things are more effective than Chinese herbal formulas to maintain balance in the human body. I will show you that a complete beauty regimen can be based on a well-balanced nutritional program designed to provide a foundation of health. This high level of health provides the groundwork for natural beauty and prevention of disease. Western medicine is great for acute intervention—X rays for broken bones, surgery, diagnostics, and so on—but it doesn’t address total wellness from this traditional Chinese perspective.

By the time you’ve finished this book, you’ll be figuring out what foods you need to bring equilibrium or balance to your system. You will incorporate common foods into your diet with natural awareness that they are nourishing your body at a cellular level, encouraging your hair to grow without graying, cleansing your body so that it becomes free of age-causing toxins, even making your fingernails grow long and strong.

The starting place for any study of this ancient practice is a concept we call the Organic Whole.

All life is part of nature—an organic whole that includes the earth and the cosmos. Notice that I said “part of nature,” as in part of a whole.

When the weather turns cold, we know that we need to wear more clothing to stay warm. During winter, we eat heavier, more filling foods—root vegetables, hot soups, and the like—that warm our bodies from the inside out, as opposed to summer, when we eat lighter, cooling foods. During hot weather we need more cooling liquids and foods with a high moisture content to replenish the fluids lost through perspiration. Nature supplies us with juice-filled fruits and melons to make it easier for us to meet this need.

Nature is always in and around us. The seas and trees supply us with the oxygen we inhale to sustain life. In turn, we exhale carbon dioxide, which trees and other plants need for photosynthesis. When we are in harmony with the natural rhythms of nature, we experience a sense of health and well-being. When we oppose these forces, we are edgy, uncomfortable, and in extreme cases, ill. Premature aging can also result from imbalances in our bodies.

When I was flying back and forth between New York and Paris, New York and Rome, Rome and Hong Kong, Hong Kong and New York on modeling assignments, my body’s “timeclock” was constantly upset as I raced from time zone to time zone. My sleep was so disrupted that I often woke up from a nap exhausted. I was always tired, no matter how much I slept, dehydrated from spending so much time in the pressurized environment of airplanes. And hungry. Really hungry. The balanced, healthy way of eating that my mother had taught me was ignored. It was too old-fashioned for me at that time. After all, I was a modern girl.

I loved my life as an international fashion model, but before long, my looks began to suffer. My hair lost its luster, and my skin was dry and flaking in some areas and tender with acne in others. I had absolutely no energy. I was out of harmony, out of balance. And my body showed it. I went to a series of Western doctors who treated me with antibiotics and injections. My skin would clear up, but recovery was always short-lived, so back to the doctor I’d go. Obviously, with my face breaking out, I was unable to work, so I took time to visit my parents, who were then living in Arizona. My mother immediately began to feed me the foods and tonics my body needed to heal itself and prepared soothing masks and toners to ease the blemishes and pain that were plaguing my skin. Within a week or two, the redness and flaking began to subside and my energy returned. Soon, as balance was restored to my body and my chi was flowing freely, I was my lively, clear-skinned self again.

When we speak of the Organic Whole and the principles of yin and yang, we must remember that these laws are not absolute. In fact, they are quite changeable, just like the weather and the world around us. We’ve all had days that started out at an easygoing, balanced pace, only to have everything erupt with hot yang anger when the flight to the Caribbean was missed, or everything screeched to a halt when a very yin snowstorm blanketed the city. By being aware of the potential for changes that can disrupt the balance of our bodies and our lives, we are able to maintain a higher level of wellness and beauty.

In the process of all this research, ancient Chinese scholars formulated what is known as the “Theory of Opposing Principles.” Simply put, all forces of nature have two equal yet opposing—and very necessary—sides: deficiency and excess, cold and hot, recessive and dominant, negative and positive, dark and light. Yin and yang represent these two fundamental universal forces. When these equal, interdependent components are in balance, optimal movement of the life force—chi, or qi, pronounced “chee”—is possible. Yin energy moves inward and downward, affecting internal organs and body fluids. Yang energy moves upward and outward, toward the surface of the body.

When these forces are in harmony, there is balance. When there is balance, there is optimum health. Where there is optimum health, there is amazing beauty. This occurs when yin and yang are in harmony.

Chinese doctors have traditionally concentrated on keeping these forces balanced in their patients. When yin and yang are in sync, harmony (and thus good health and beauty) prevails. Unlike Western doctors who concentrate on the treatment of illness, Chinese physicians are trained to focus on the wellness of their patients. A good Chinese doctor has only well patients.

Harmony and balance are woven throughout nature so strongly that they make up the cultural fabric of Chinese civilization itself. Even the most humble housewife keeps these ideas in mind while preparing her family’s daily meals.

You have probably been practicing the yin/yang concept already—it’s a supremely natural way to live. For example, hot days (yang) require cooling foods (yin). This is why watermelon tastes so good in the summer—it balances the heat that you feel in the environment and within your own body. Cold days (yin) require warming foods (yang). Few things are better than a steaming bowl of spicy chicken soup or beef stew in the dead of winter.

The Chinese characters for yin and yang present vivid images of their meanings. The character for yin means “shadow” or without sun, “the shady side of the mountain,” while the character for yang means “sun,” as in “the sunny side of the mountain.” Yin is cold or cool and calm, and yang is hot and active. The upper part of the human body is yang and the lower part, yin; the exterior is yang and the interior is yin; the back—which gets sunburned more often—is yang and the front, yin. Your arms, which are yang in nature, as they are extensions of the upper part of the body, also have their yin and yang sides. When you drop your arms to your sides, you will notice that the outside is exposed to the sun, while the inside, which lies against your torso, is not. The outside is yang; the inside, yin.

All life can be divided into equal yet opposing yin and yang forces. The attraction or repulsion of these opposing forces, like the alternating of electrical charges from positive to negative and back, or the action of two toy magnets, makes movement and change possible. This movement provides the underlying life energy, chi, in all life. Yin energy is passive and slow moving, while yang energy is active and fast moving. Yin and yang may cause the movement of chi, but it’s up to us to maintain and control the flow of that force as it moves through our bodies.

Once you become aware of this, you’ll find yourself automatically identifying which energy and which activities are yin in nature, and which are yang. Quietness is obviously yin, while loudness is yang; peace and stability are yin; war and activity are yang. Cold energy is yin; hot is yang.

All living beings, our bodies included, are in a constant state of change, made possible by the yin/yang interaction. Many factors contribute to change—what we eat, our level of activity or inactivity, job stress, even the weather. While we can be yin today or yang tomorrow, we generally follow a pattern, falling more often into one or the other category.

At the heart of the Tao of beauty is the life force we call chi. Although every form of traditional medicine shares the concept of a living energy that sustains all life, the term chi has no true English-language equivalent. The Japanese refer to this force as ki, while Hindus call it prana. The Greek term is pneuma.

In Chinese medicine chi is interpreted in two ways: internally and externally. Internally, it’s one of the three substances that enable the organs to function; the other two are blood and bodily fluids. Externally, chi is taken in through metabolic nourishment, which is carried by food and water.

Chi moves in the body through a network of channels, or meridians, that govern how the body functions, much like an irrigation system that carries water to a field. These meridians form a network through which chi courses to empower every organ in the body. When energy is blocked or slowed as it travels through these channels, organs, tissues, and even cells are deprived of the power needed to function at top potential. Even one block in the flow of chi can cause the whole organism to malfunction.

Chinese scholars have studied the meridians for thousands of years, developing the healing art we now know as acupuncture, and its related therapy, acupressure, to disperse energy blockages and restore balance. The acupuncturist inserts fine needles in the appropriate meridians to free blocked energy so that chi can move freely, while the acupressure practitioner presses and manipulates points on the body to encourage the flow of chi.

Exercises that manipulate the flow of chi have been practiced in a variety of forms for thousands of years. The Chinese exercise called Chi Kung—chi, meaning “energy,” as well as “breath” and “air,” and kung meaning “work” or “skill”—began as a therapeutic dance to ward off rheumatism and other symptoms of illness. Through the ages, it evolved into a complete energy management program of meditative breathing, concentrated movements, and martial arts. I’ll teach you the basic Chi Kung exercises I learned from my parents in Chapter 10, Exercises for Energy. These exercises direct the flow of chi through the meridians and energize the body.

There are twelve main meridians, each relating to specific organs in the body. Branching from there is a complex network of supplementary channels, of which the smallest, cutaneous, meridians run just under the skin. There are approximately 365 acupuncture points, or energy vortices, along the main channels, with many more along the smaller channels. These points are places where the flow of chi is frequently disrupted. Generally, they are found at indentations or bumps in the path, such as where two muscles intersect, where there is a notch in a bone, or at a joint.

While meridians are not visible to the human eye, they can often be felt. For example, there is a point in the mound of tissue between your thumb and forefinger that will get rid of headaches. With the thumb and forefinger of your right hand, locate the point where your thumb connects with the bones of the forefinger of your left hand, then move back just a little bit into the web of flesh. If you have a headache you will invariably hit a tender spot. That spot is the blocked meridian. Press gently and massage this spot for a minute. Release the pressure and switch hands, using the thumb and forefinger of your left hand to massage the meridian on your right hand. Within another minute or two, you should begin to feel relief from your headache. (NOTE: This exercise is not recommended for pregnant women.)

There are four types of chi—inborn or original, pectoral, nourishing, and defending.

1. Inborn or original chi. This is the life force we inherit from our parents. It is the most fundamental form of chi, and it is stored in the kidneys.

2. Pectoral chi. This is derived primarily from the air we breathe. This chi is stored in the lungs.

3. Nourishing chi. This energy is essential to replenish and revitalize the tissues of the body. Derived from food and water, this life force circulates through the bloodstream.

4. Defending chi. This external energy force protects the body from hostile conditions such as inclement weather or even germs, while maintaining body temperature by controlling the opening and closing of pores. Think of this as an external force field surrounding and protecting your body.

When flows freely through the channels or meridians, we experience not only health and vitality but also full expression of our inner selves.

Chi has five primary functions. Although they are very different, they are closely related. They serve to keep the body operating efficiently and healthily.

1. Growing action. According to the Chinese way of thinking, the initial chi function is growth. Chi is the primary source of energy responsible for growth and development of the body. Lack of chi can result in delayed or slow physical and mental development, insufficient blood formation, weak digestion and bowel function, low energy, or disturbed metabolism. In terms of beauty, this results in weak, short nails, thin hair, and increased hair loss, as well as loss of skin color and tone.

2. Warming action. Chi is the main source of body heat, which maintains the health of the organs. Lack of chi can cause intolerance to cold, especially in the limbs. It can also cause purple lips and runny noses. When chi is flowing properly, your cheeks will be rosy and your lips pink.

3. Defending action. Chi protects the body from invasion of toxins by guarding the surface of the skin. Without sufficient defensive chi, you can develop itching, eczema, or other topical skin irritations.

4. Governing action. Chi maintains the movement of all fluids throughout the body, from blood, perspiration, and saliva to sperm, urination, and excretion. It keeps your blood flowing and controls glandular secretions. Governing action also prevents organs from descending. Poor governing chi can cause water retention and weight gain.

5. Transforming action. Chi performs actions that affect the body’s metabolism, causing changes within the body. This energy relates to the vital energy of blood and fluids, as well as the digestion of food, transforming the essence of the food into the energy the body needs.

The Tao of beauty calls for us to maintain maximum flow of chi. As you will soon learn, there are many simple ways to do this, mostly by using herbs and foods that have been found to restore balance throughout the body, and by cultivating the breathing and exercise techniques associated with the practice of Chi Kung, detailed in Chapter 10.

One of the fundamentals of traditional Chinese philosophies, including medicine and, consequently, of the Tao of beauty, is the theory of the Five Elements—wood, fire, earth, metal, and water. Identified by ancient scholars as essential to sustaining life, these substances provided a matrix for all life.

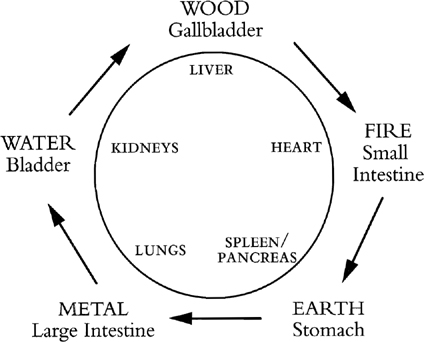

Applied to the seasonal cycles, wood is equated with spring; fire, summer; earth, late summer; metal, autumn; and water, winter. This concept comes directly from ancient Chinese healers who determined that chi moves throughout nature—including our bodies—in a rhythmic, orderly, continuous circuit. These great healers also identified the relationship between the Five Elements and the organs of our bodies.

Just as we are born under specific astrological signs that reflect our personalities, our organs have their own chart related to the Five Elements. We have five main organ groups that correspond to the Five Elements. Each organ group consists of one yin organ and one yang organ; yin organs are solid, while yang organs are hollow. The liver (yin) and gallbladder (yang) are associated with the wood element; the heart (yin) and the small intestine (yang) are associated with fire; the spleen and pancreas (yin) and stomach (yang) are associated with earth; the lungs (yin) and the large intestine (yang) are associated with metal; and the kidneys (yin) and bladder (yang) are associated with water. See this page for a chart that summarizes the way the Chinese view the human body.

The Five Elements represent the five stages that are characteristic to all change. By understanding this concept, we can understand how to restore the yin/yang balance within our bodies and maintain the health and beauty of the Organic Whole.

The circular diagram below illustrates how the nurturing energy of the Five Elements and their corresponding organ groups flows from one element to the other in a “creative” or energy-generating cycle, while the star-shaped diagram shows the controlling or limiting properties of these same elements and organ groups. Like the relationship between mother and child, the elements nurture each other. On the other hand, each element also has the disciplinary quality of a father-child relationship. I’ll do my best to explain the energy flow between the Five Elements as simply as possible.

Starting with wood, follow me around the circle:

• Wood burns, or nurtures fire. Once burned, ashes become part of the earth.

• Therefore, fire generates earth.

• Earth—the source of ore—generates metal.

• Metal—or minerals—dissolve in and therefore empower water.

• Water keeps trees—wood—alive.

The Nurturing Energy Among the Five Elements and their corresponding organs

NOTE: Yang organs are on the outside of the circle; yin organs on the inside.

Now follow me through the star diagram, which demonstrates how the elements control or restrict one another.

• Metal controls or restricts wood, as an axe will cut a tree.

• Wood restricts earth, as the root of a tree will displace soil.

• Earth limits water, as an earthen dam can stop a river.

• Water restricts or extinguishes fire.

• Fire controls or melts metal.

The Controlling or Restrictive Energy Among the Five Elements and their corresponding organs

Ancient Chinese herbal doctors applied this theory of the Five Elements to explain how our organs work in relation to one another within the whole. If you look at the chart on this page, you will understand how the corresponding organs nurture and control one another in the same way that the Five Elements do. For example, the lungs, which correspond to metal, nurture the kidneys, which correspond to water. The lungs also have controlling energy around the liver, which corresponds to wood. We are at our healthiest when these relationships are in balance, and least healthy when they are out of balance.

In their quest to understand how the body works, early scholars noticed many connections between the Five Elements and the five organ systems in the body. They also saw a connection between the face, organ systems, and tissues. They divided the face into five segments, or “senses,” and the rest of the body into five related tissue groups, each corresponding to the Five Elements (see chart on this page).

The eyes reflect the condition of the wood organs—the liver and gallbladder. Sluggish liver function, for example, is often diagnosed by Western physicians when a patient has jaundiced or yellow eyes. The face may also take on a greenish cast if the gallbladder is out of balance. Chinese doctors noticed that these same patients also experienced extreme tiredness and nonspecific joint pain—indicative of tight, rigid tendons, or stagnant chi.

Deficiency of blood and energy in the liver will cause malnutrition of the tendons, which can result in numbness and tremors of the limbs. The Chinese also believe that the nails are the same substance as the tendons and require the same nutrients. Hard, strong nails indicate that the liver is healthy.

Chinese legend says, “The tongue is the sprout of the heart.” Thus the fire organs, especially the heart but also the small intestine, are linked to the tongue. When blood circulates freely and fully, the tongue—and the whole face—will be slightly flushed with a bright, healthy glow. Inefficient blood flow renders the face and tongue pale and white.

The tissue related to this facial sense is the vessel, a term used by Chinese physicians to describe the entire body. Without optimum heart and digestive function, the body is rendered out of balance. A Chinese doctor will use the color, shape, and condition of the tongue to diagnose illness.

The mouth itself is the facial sense linked to the earth organs. The strong, vigorous chi of the spleen encourages a healthy appetite, fully functioning taste buds, and rosy lips. The mouth is also the entrance to the stomach, the yang earth organ, carrying nourishment from the foods we eat into this primary digestive organ. This is how the facial senses, in this case the muscles of the body, are fed.

Likewise, the nose is the facial sense that is related to the metal organs, particularly the lungs but also the large intestine. Strong respiratory function maintains circulation of fluids throughout the body, which makes for thorough and efficient elimination of wastes and activates defending chi energy. This protects the body by blocking the passage of airborne toxins through the skin’s surface, while keeping skin moist and bright.

When the metal organs are “clean” and free of toxins, the skin and hair are radiantly healthy.

The ears are the facial sense that relate to the water organs—the kidneys and bladder. The skeletal system, or bones, constitute, in this case, the related tissue. Thousands of years ago, Chinese scholars observed that if a person’s kidneys, which they considered to be the basis of life, were not functioning, that person would die. In traditional Chinese medical philosophy, the kidneys are said to open into the ears, thus the energy meridian that links the two relates to hearing. When the kidneys are properly functioning and fully nourished, bone marrow production is enhanced, resulting in strong bones.

Other indicators of healthy kidney and bladder function are shining, healthy hair without grey, and strong, pearly teeth.

Traditional Chinese physicians often use these senses and related tissues as diagnostic tools. We will consider them as part of the total beauty-wellness picture.

Here in the West, we see the changes in climate or weather as incidental to our health and well-being. The Chinese believe that these seasonal changes affect us deeply, because adverse conditions can disrupt our natural balance, both internally and externally, by penetrating the protective energy shield that envelops our bodies.

When we speak of “climate,” we are talking about not only the external weather but our internal weather as well. Nature’s Six Climatic Effects—wind, summer heat, dampness, dryness, cold, and fire—are associated with the progression of the seasons: wind with spring, heat with summer (which is different from the heat associated with fire), dampness with late summer, dryness with fall, cold with winter. Fire stands alone, both as one of the Five Elements (see this page) and as one of the Six Climatic Effects.

These conditions can exist alone or in combination—wind-heat and heat-dampness, for example. When one or more climatic conditions are excessive, the body reacts in very specific ways, all of which can be corrected by consuming specific foods to nourish and balance the hot and cold energy in each system of the body.

Remembering the Organic Whole, we are part of nature. Our bodies respond to climate in much the same way as does the earth. Just as too much heat burns and cracks the earth’s surface, excessive heat burns and cracks our skin and chaps our lips. Internally, the phenomenon occurs according to our lifestyle and the food we eat. Too much heat energy, caused by stress, anger, fear, or any degree of yang emotion, or caused by foods that are high in this same hot energy—deep-fried or spicy barbecued foods, for example—can disrupt digestion, causing constipation and even dry, cracked lips.

Chinese philosophy considers wind to be a climatic condition that is usually associated with spring but can occur any time of year. Wind moves quickly, just as pain and discomfort can move from place to place in the body. By its very nature, wind is often combined with other climatic conditions to attack our bodies—dampness and wind, heat and wind.

Wind is considered to be an external force. When wind attacks, it tends to break the barrier or energy shield of the skin and invade the upper torso. Symptoms of excess wind include head colds and flu-like symptoms. So, when the weatherman forecasts high winds, we need to stay indoors or dress in the appropriate clothing—scarves, hats, sunglasses—to protect our bodies from penetrating gusts. We also need to apply moisturizing creams to prevent the wind-caused dryness that chaps our skin and lips.

Although generally associated with summertime, excess heat can also occur in spring and fall. Although heat may be the opposite of cold, it too can cause chapped lips and skin. Oil production may be stimulated by summer heat, creating a variety of skin problems beyond sunburn. Perspiration and sebaceous oils combine with airborne pollution to clog up and enlarge pores. Make sure to clean your skin frequently and replenish lost fluids with creams or lotions that will draw moisture to the skin and hold it there. Drink plenty of water.

Excess internal hot energy results from too much yang chi in the gallbladder and kidneys, too much stress, as well as from eating foods that are deep-fried or too spicy. This condition can cause excess yang energy—fevers, boils, or flushed and blemished complexions. It can cause excess thirst, dryness of the lips and tongue, and, especially when the body has excess summer heat energy, strong-smelling urine due to toxins in the body. These toxins are the result of undigested foods and decaying waste in the intestinal and urinary systems. We tend to move more slowly during very hot weather and need to restore body fluids lost in perspiration by drinking plenty of cooling liquids, especially water, and eating foods that cool the body—melons, mint, tofu, green tea, cucumber, squashes, grapefruit, spinach, and tomatoes. The food chart on this page will give you more suggestions for cooling-energy foods to incorporate into your diet.

The Chinese say that dampness is the prevailing energy of early fall, especially in humid climates. A little dampness—as in mild humidity—can actually be helpful, keeping the skin moist and soft. However, for some people, dampness can encourage germ and bacterial growth, which can result in skin that is prone to acne and other infections.

External dampness is caused by weather conditions such as rain, humidity, mist, dew, or even mildew and mold. Excessive dampness is sticky and lingering. Symptoms include rheumatism and arthritis, achiness, heaviness in the head and body, sluggishness in the arms and legs, bloating, cold sweats, fatigue, ennui, heavy secretions from the eyes and nose, diarrhea, and frequent urination or, conversely, water retention. The key to correcting these conditions is to cleanse waste and toxins from the system with special foods, teas, and topical treatments.

Internal dampness is usually caused by consuming too many cold foods—foods that are served cold as well as cold-energy foods—and by too much alcohol, coffee, and sugary drinks and foods (see the food chart on this page). As a result, certain functions of the spleen may be interrupted, causing severe stress on the adrenal glands. When the spleen fails to regulate the flow of fluids in the body, improper functioning of the elimination system results. It is essential that the body’s wastes be expelled or these toxins will contaminate the entire body, causing colds and flu, irritated skin, and nonspecific joint pain—that creaky, achy pain you may feel before it rains. Pancreatic imbalance can lead to diabetes and other immune deficiencies and degenerative conditions.

Dryness is most common in the fall, but can reveal itself as warm dryness in late summer through early fall and cool dryness in late fall through winter. It can also be created artificially any time of year, as in the warm dryness from a heater or furnace or the cool dryness from air conditioning.

Dryness, whether combined with cold or heat, is particularly damaging to the lungs. Internal and external dryness can cause dry, itchy skin, chapped lips, and constipation or hard, dry stools. External dryness can lower the body’s resistance to illness by inhibiting its protective energy shield. This makes the body susceptible to illness and immune deficiency disorders.

Internal dryness can cause a decrease in body fluids. Such excessive dryness results in a dry mouth, nose, and throat; coughing, especially the dry, wheezy kind; constant thirst; cessation of sweat; and infrequent urination.

Restoring moisture to both the environment and especially the body is the best way to counteract dryness. If necessary, invest in a humidifier to restore moisture to the air distributed through your home heating and air-conditioning system. Take care that your body is hydrated inside and out. Moisturizing creams and lotions will ease dryness, itching, and flaking. To guarantee internal moisture, drink ten to twelve eight-ounce glasses of water per day and eat plenty of moisture-rich foods—melons, cucumbers, honey, avocado, sesame seeds, squashes, grapefruits, tomatoes, yogurt, and the like.

Also, stop smoking. Specifically damaging to the lungs and respiratory system, cigarette smoke invades the body’s protective energy shield, lowering its resistance to healing.

Ordinarily associated with wintertime, cold conditions, like wind, can arise any time of year, especially once the sun has set in the evenings.

Everyone knows that when temperatures are very low, our bodies fight to maintain body heat. Pores close and capillaries contract. Blood rushes to the cheeks to help keep them warm. Cold can cause chapped lips and dry, flaky, or cracked skin. Prolonged exposure to frigid temperatures can even result in broken capillaries in unprotected areas. Although cold may initially stimulate blood flow and energy levels, after a while, energy levels may drop precipitously to conserve body heat, resulting in pale, even blue, skin. Protect your skin from external cold by wearing appropriate clothing and using protective lotions.

Symptoms of excessive internal cold can include loss of appetite, impeded digestion, joint pain or inflammatory arthritis, cold, pale hands and feet, forgetfulness, and fatigue. These conditions indicate an overall weakness or slow metabolism. While excessive internal cold is often caused by dietary imbalances, notably too many cold-energy foods, it can also be caused by long-term illness, surgery, or even pregnancy and childbirth. Warming tonics made from yang-energy herbs that generate internal heat—cloves, cinnamon, cardamom, ginger, anise and star anise, basil, rosemary, and sage—will provide relief. Refer to the food chart on this page for more information.

Sage (Salvia officinalis)

The ultimate or extreme energy of all seasons, fire is both one of the Six Climatic Effects and one of the Five Elements. Chinese apply the term “fire” to any extreme or abnormal climate condition where symptoms associated with the original chi system are intensified.

Essentially, external fire is similar to heat, when the outside of your body burns up on a hot day. Internally, fire prevails when the body’s chi is overstimulated or intensified. Smoking and exposure to smoky conditions cause “lung fire,” while overeating or overindulgence in rich food and drink, with such symptoms as indigestion, heartburn, gas, and even ulcers, creates “stomach fire.” Alcohol abuse and alcoholism create both “stomach fire” and “liver fire.” Temper tantrums or frequent outbursts of anger cause “liver fire.” Prolonged internal fire causes permanent damage to the affected yang organ-energy system and, ultimately, to the secondary yin organs.

Too much internal fire can cause fevers, flushing, bloodshot eyes, painful, swollen gums, and an irritated, bright red tongue, not to mention acne flare-ups. In women, the ultimate example of excessive internal fire is menstrual problems—painful ovulation, premenstrual pain, painful cramps, a heavy, dark flow, and irritability.

The only effective way to protect the body from the ravages of fire is to practice moderation in both diet and lifestyle. This includes maintaining balance in the systems of the body by nourishing it at a cellular level.

In the chapters ahead, I’ll share with you some of the remedies—from foods to eat to formulas to apply topically—that are traditionally given to help balance climatic conditions.

While conditions caused by climatic conditions are, as a rule, external, those caused by the emotions are primarily internal. In the West, such ailments are considered psychological, or even imaginary, in nature. Chinese tradition states that five emotional states are at the root of many physical conditions. These emotions are anger, joy, sadness/grief, anxiety/worry, and fear. When these emotions are in balance, the body is stronger and has less illness.

The emotions cannot cause diseases but they can aggravate them, even injuring the health of the related organs (see chart on this page). When the emotions are in harmony or balance, the body is without illness. When one or more emotions are too strong or too weak, physical symptoms may occur.

Western doctors are now beginning to accept the mind-body-spirit or emotional-physical link with illness. Physical ailments that are rooted in emotional conditions are no longer considered psychosomatic.

Problems arising from imbalances in the Five Emotions are more difficult to treat than those caused by climatic factors. After all, we experience a wide range of emotional highs and lows throughout the day. Situations arise, however, when an emotion becomes so powerful that it overwhelms a person’s body and spirit.

Anger has been found to relate to the liver, so too much anger can alter the flow of the liver chi, resulting in liver damage. To the Chinese, anger stems from an excess of heat (yang) energy in the bloodstream. Anger runs the gamut from resentment and outrage to jealousy and frustration. We believe that ruddy-complexioned people are more prone to emotional outbursts than those who are less “full-blooded.”

An angry person often has a wide-eyed expression and tension in their joints and tendons—clenched fists, a squared jaw, and a taut stance. Left unchecked, anger can cause high blood pressure, headaches, dizziness, and even liver damage and gallbladder distress. The hot yang energy produced by anger and imbalance often shows up as acne in women before or during their menstrual cycles.

Repressed anger often results in stagnant or restricted flow of chi and, as with excessive anger, results in liver and gallbladder damage.

Everyone knows that happiness—joy—is good for the heart. This energy can give us a beautiful glow, but like everything in life, too much of anything is not good for you. An old Chinese proverb states that when one is excessively joyful, the spirit scatters and can no longer be stored. Excess joy is regarded not so much as happiness or contentment but as overexcitement or agitation. Too much joy can lead to “nervousness” or agitation and insomnia because joy is directly connected to the heart. It can also lead to intestinal upset, such as diarrhea. Too little joy exhibits itself in depression and oversleeping.

When joy is present, the facial sense—the tongue—is relaxed, moving with laughter; the related tissue, the body, or vessel, is in harmony.

Symptoms of anxiety range from moodiness and depression to obsessive and compulsive behavior. These emotions affect the spleen, pancreas, and stomach, altering the flow of the chi through these organs. The facial sense related to these earth emotions is the mouth, which in anxious times can be dry and tense, with lips pursed or downturned. Muscles, the related tissue, are often strained and tense.

According to the Chinese, too much anxiety can result in intense muscle fatigue, nausea, impaired digestion, and sometimes even in premature graying of the hair.

In the Chinese system, sadness and grief are associated with the lungs and large intestine. Sobbing, for example, originates deep within the lungs. These two emotions are generally treated the same way. Sadness and grief, when appropriately expressed in response to an incident or emotional stimulus, are regarded as healthy. However, when these emotions are overwhelming or unresolved, respiratory functions—the functioning of the lungs—can be disrupted. Anyone who has experienced intense sadness or has grieved for a loved one can attest to how this strong emotion can leave their insides in knots, proof of how the large intestine can be affected.

Tears of sadness and grief affect the facial sense associated with this emotion—the nose—by causing excess mucus, better known as a runny nose, and the related tissue, the skin, by causing redness, blotchiness, and sometimes break-outs. The hair, which is also a related tissue, may fall out in times of intense sadness.

A little fear can be a good thing. It keeps us from stepping out into traffic or walking into dark alleys. In the Chinese tradition, fear affects the kidneys and bladder, interrupting the flow of chi in these organs. Chronic or unresolved fear—too much fear—can damage the kidneys or bladder and cause a variety of problems, from bedwetting and frequent urination to kidney stones, bladder infections, and in men, premature ejaculation.

In times of fear, hearing is intensified, connecting the facial sense, the ear, to this emotion. The tension caused by fear interrupts the development of bone marrow, linking the related tissue, bone, to fear.

Refer to the chart below, “The Chinese Way to View Your Body,” for a clear picture of how the Five Elements are related to the body’s five organ systems, facial senses, related tissues, and emotions. This intricate connection explains why your heart flutters with joy when you see your little daughter running into the room with a bunch of flowers, and why you may have an upset stomach when you’re worried about those final exams you just finished. This also explains the connection between that red, runny nose you have when you’ve been crying, and why children sometimes wet their pants when they’re frightened.

Problems arising from emotional imbalances are more difficult to treat than those caused by external, climatic factors. After all, we experience widely ranging emotional highs and lows throughout the day. Situations can arise when an emotion becomes so strong that it overwhelms a person’s body and spirit. While hostile factors, including overwrought feelings, may cause disease, an individual’s inherited energy system—genetics—must be considered. Other factors in this mix are lifestyle, relationships, work, diet, and exercise habits.