Harmony Bench

Within the classical ballet tradition, the concept of choreography was preceded by that of arranging: dance masters availed themselves of a codified vocabulary of movements and steps, which they ‘arranged’ into dance compositions. This essay focuses on arranging as a method or practice suited to contemporary interdisciplinary research with an emphasis on the digital humanities. Broadly construed, arranging refers to any process of collecting, ordering, fitting-together, and displaying objects – from flowers to furniture to puzzle pieces. My own thinking is informed by the sequencing of steps known in ballet as enchaînement, a type of classroom exercise in ballet technique in which a series of travelling steps are linked (literally chained) together as a phrase or combination that moves across the dance floor. Enchaînements are built, or arranged, from a discrete vocabulary and syntax that determines which movements or steps may logically precede or follow others. Connections among individual step-units are not wholly predetermined, nor are they wholly open to any connection whatsoever.

While pre-existing the computational, ballet as an aesthetic vocabulary and a mode of training participates in a digital episteme. It cultivates habits of mind and body that resonate with contemporary database logics, valuing, for example, modularity, reversibility, and symmetry within a system of units that can be broken down into ever-smaller components, or conversely, built into an almost infinite number of compositions. Though my own understanding is informed by enchaînement, I find in the larger concept of arranging a productive model for my recent forays into data-driven scholarly projects such as the Mapping Touring1 project I present here. Arranging as a method is concerned with crafting relationships of contingent interdependency; it draws attention to internal coherence and sense-making through the juxtaposition and co-articulation of units of information and their relations.

Mapping Touring is a digital humanities research project that tracks and maps the appearances of early twentieth-century dancers, choreographers and dance troupes with an emphasis on touring. My concern is to represent the dates of performance, cities and venues, and repertory performed, giving shape to economies of movement through which gestural vocabularies and ‘kinesthetic legacies’ (Srinivasan 2007: 2) flowed prior to our current media-saturated era. With this project, I am interested in the movement of movement – how it moves, what it moves, where it moves, why it moves, and who or what moves it. To craft the mapping dimension of the project, however, I have also been required to generate the datasets that can then be plotted and visualized.

Media theorist Lev Manovich cautioned in The Language of New Media, ‘data does not just exist – it has to be generated. Data creators have to collect data and organize it, or create it from scratch’ (2001: 224). The term data comes from the Latin word dare, which means ‘that which is given’ (Galloway 2015). As a mass noun, ‘data’, which are given unordered or unorganized, attain their value as a collection or a set that can be parsed and displayed. Data are given to be arranged, and it is the process of arrangement, first as a set and later as a visualization, that makes data usable and therefore meaningful. Arranging is the process of forging relationships among the given data. Though data have the aura of neutrality, they already carry the weight of interpretation within a system of cultural values that guide identification and assembly within scholarly research. In arranging data, one shapes and re-shapes the relations within a collection such that analysis and further interpretation may follow.

In my Mapping Touring project, we are gathering data about performance engagements from concert dance programmes.2 Although archives contain scrapbooks, route books, correspondence, newspaper reviews, and other artefacts with which we corroborate the performance data, it has been necessary to focus primarily on programmes to delimit the parameters of the project. However, in selecting concert programmes as our source material, we also limit ourselves to performance events that subscribe to a cultural logic in which the creators, performers and audiences of dances are human; dance pieces are identified as unique entities (notwithstanding variability over time); and the dates, times and locations of each event have been documented. Because this project renders the historical record anew, it cannot change that record or offer a substantive challenge to the ideologies and biases that produced it. But in moving from the case study to the dataset, the gaps and absences that historians and cultural scholars have already identified in the record should appear in even greater relief. For this reason, as theatre scholar Debra Caplan (2015) has compellingly argued, macro-histories are most productively arranged in tandem with micro-histories: as methodological complement rather than competitor. Mapping Touring certainly pursues a macro-history of twentieth-century concert dance, but the universalizing tendencies of such a digital humanities project can be interrupted when researchers arrange canonical figures and standardized data alongside micro-histories, local performance cultures and marginalized performance practices.

Initial stages of arranging as a method might include gathering, collecting, generating and evaluating, followed by activities such as filtering, sorting, cleaning, charting and scoping. Later steps might be curating, assembling, visualizing, correcting, testing, juxtaposing, modelling and crafting. Though I have presented these as stages, in point of fact I have found it necessary to travel back and forth along this spectrum of activities. First attempts at data visualization offer new insights as well as rehearsal for the fuller project, and also make errors or a need for additional information apparent. Arranging data through visualization is thus a mode of discovery as well as display. Inevitably, visualizations reveal flaws and deviations in the underlying data, such as misspelled names or titles. Visualizations thus occasion a return to previous steps to correct, refine and clean.

However, cleaning data risks erasing important information in favour of standardization. In this way arranging data is also like arranging steps in ballet, where cleaning refers to a process of bringing dancers into alignment and producing a desired level of uniformity prior to performance. Both forms of cleaning are subtractive rather than additive: they take away ‘impure’ features. It is only when seeing an arrangement together that one can see what is out of place – what is ‘noise’ or what does not make sense and requires further investigation or scholarly analysis. Not all anomalies, however, are impurities to eradicate; many lead to important discoveries, add nuance, or open new lines of scholarly or aesthetic inquiry. Though cleaning is necessary to make data meaningful by making comparison possible, premature or overly zealous cleaning can erase the very differences one hopes to find.

For example, in a small project helping me test the larger Mapping Touring idea, I assembled performance data from Anna Pavlova’s tours to Central and South America during the First World War (see Figure 1.2.1).3 In plotting the performance locations on a map I discovered an anomaly. It would appear that Anna Pavlova and her company are in Puerto Rico and San Francisco at the same time. Human error is the most logical explanation for the uncertainty as to where Pavlova actually was. However, the dataset is incomplete, and company members did not always travel together due to injuries or visa problems. Furthermore, the turn of the twentieth century is full of copycat performers who stole each other’s routines and sometimes performance identities. What is clear is that this particular arrangement of location information revealed an anomaly that requires further attention, whether that ultimately means correcting the data or following its lead toward a new analysis of Pavlova’s global movements. While I could clean this data by simply erasing the unlikely San Francisco appearances, doing so without first determining how they came to be listed there would be a missed opportunity. Arranging can reveal outliers, but the difference between a mistake and a discovery can only be discerned with further exploration.

Creating new arrangements of old information can help scholars re-examine assumptions and inherited narratives. In concert dance history of the twentieth century, for example, New York City quickly emerges as a global cultural capital. Yet, creating an arrangement of performance data that weights all locations equally – regardless of the number of engagements – paints a very different picture of what it meant to be a performing artist or performance audience in the first half of the twentieth century. Suddenly unexplored mid-sized cities and small towns emerge as important destinations for the arts. How might evaluations of audience sophistication shift if, for example, we discover that artists perform the same repertory in small towns as they do in large cities? Or if it appears instead that artists select different repertory for different cities, what might that indicate about how they relate to audiences, or their understanding of audience perception? Arranging touring information alongside railway routes and other modes of transportation (Wilke 2014; Elswit 2015) promises to shed additional light on performance engagements in smaller towns, and might further assist in re-evaluating the geography of aesthetic cosmopolitanism in light of long-distance networks (Latour 1987) that connect movement vocabularies across continents. Arranging the domestic touring pathways of concert dance with popular vaudeville and burlesque circuits will also give historians and cultural theorists a better understanding of how movement vocabularies circulate in relation and in direct response to each other.

For the sake of this essay, I have only focused on a small portion of Pavlova’s touring data, but the possibilities of arranging as method lie not only in rendering a single strand of data in different visual arrangements, but also arranging touring information from different artists alongside each other. For example, understanding Pavlova’s movements during the First World War would be further amplified by creating an arrangement that included the performance

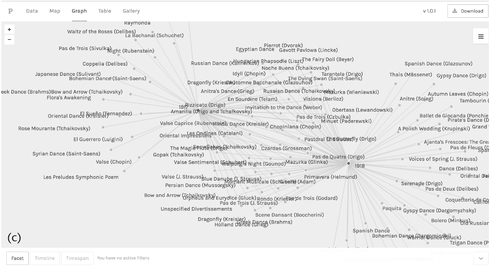

Figure 1.2.1 These screenshots represent three arrangements of the same data as (a) a list, (b) a map, and (c) a network, which I have opted to present in three different visualization platforms. Each arrangement highlights a different component of the underlying data from Pavlova’s touring in Central and South America during the First World War: the list in Tableau shows a chronological progression in tandem with repertory performed; the map in CartoDB represents an a-temporal geo-spatial accumulation of events; the network in Palladio sorts repertory into works performed in the 1917 and 1918 calendar years, and those shared between the two as part of the same performance season, which generally runs July–June.

engagements of other artists or companies during the same time period, such as Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, Isadora Duncan, or Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn. How do their touring patterns relate to each other? Are the movements of one contingent on the movements of another? Does one seem to exhibit more freedom of movement than another?

Too often, data visualizations are presented as rhetorical black boxes – assertions presented without substantiating data, which nevertheless claim status as truth through quantification. A hermeneutic approach to data, however, considers the arrangement at hand, supporting the critical evaluation of what Orit Halpern describes in Beautiful Data as the ‘aesthetic crafting to this knowledge, [the] performance necessary to produce value’ (2014: 5). What does a specific arrangement suggest or argue, and how do the aesthetics of the arrangement help or hinder that argument? What other arrangements might counter its claims? What is the ideological bent of the data or its process of generation? What role does software play in foregrounding or obscuring certain interpretive possibilities?

Arranging, which enables combinations and re-combinations of a given set of data, establishes contingent interdependencies among (in)dependent variables. In the case of Anna Pavlova, one is reminded (or learns for the first time) of the diversity and extensiveness of Pavlova’s repertoire. Not only did Pavlova and her dancers perform familiar classics from the Russian ballet canon, they performed social dance pieces, orientalist works, indigenous-themed dances, operas, and dances composed in response to local dance traditions. The Dying Swan might have captured the public’s imagination, but arrangements of Pavlova’s repertory tell a more nuanced story. Furthermore, Pavlova is remembered for the global reach of her touring, but the business and mechanics of travel, along with competition among dance artists for venues and audiences, has not been fully researched. Nor have scholars delved into comparative analyses of thematic or stylistic similarities in repertory across companies. Yet when looking at a map of touring, a list of performance locations, or the spread of repertory performed from season to season, such considerations come to the fore. Arranging performance data into sets and visualizations opens new avenues for analysing networks and geographies of influence, political economies of touring, and the global circulation of movement practices and aesthetics.

As a method for contemporary interdisciplinary research, arranging combines experimentalism with composition in scholarship. Researchers arrange data, working back and forth through processes of gathering, cleaning, displaying, and analysing, crafting relationships among pieces of information to determine which arrangement might offer a new perspective or prompt a new question. Arrangements, like the enchaînements found in ballet studios, offer internally coherent, yet potentially inexhaustible combinations. They can expand or contract in scope but remain rule-bound; they are flexible but logical. A shift of relation can produce new interpretations and understanding.

1 Mapping Touring is supported by the Office of Research’s Grants for Research and Creative Activity in the Arts and Humanities at The Ohio State University. See Bench 2015.

2 Archives frequently contain both performance programmes and souvenir programmes. Souvenir programmes are generally produced for an entire tour and contain extensive contextual information such as biographies, librettos and photographs, but do not reflect the locales in which an engagement was held. Performance programmes, in contrast, document the specifics of each performance event within a local context, including local advertisements and announcements.

3 This project was undertaken in conversation with dance scholar Kate Elswit for a co-authored presentation. See Bench and Elswit.

Bench, H. (2015). Mapping Touring: Dance History on the Move. www.harmonybench.wordpress.com.

Bench, H. and Elswit, K. (2015). Mapping Dance Touring: Onstage and Backstage. Presentation at the American Society for Theatre Research, Portland, OR, Nov. 5–8.

Caplan, D. (2015). Big Data and the ‘Obscurity’ of Yiddish Theatre. Presentation at the American Society for Theatre Research, Portland, OR, Nov. 5–8.

Elswit, K. (2015). Merging Tables and Layering Maps. Moving Bodies, Moving Culture. Last modified 28 July 2015. https://movingbodiesmovingculture.wordpress.com/2015/07/28/merging-tables-and-layering-maps/.

Galloway, A. R. (2015). From Data to Information. Last modified 22 September 2015. www.cultureandcommunication.org/galloway/from-data-to-information.

Halpern, O. (2014). Beautiful Data: A History of Vision and Reason since 1945. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Latour, B. (1987). Science in Action: How to Follow Scientists and Engineers through Society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Manovich, L. (2001). The Language of New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Srinivasan, P. (2007). The bodies beneath the smoke or what’s behind the cigarette poster: unearthing kinesthetic connections in American dance history. Discourses in Dance, 4(1): 7–47.

Wilke, F. (2014). Performance, Transport and Mobility: Making Passage. London: Palgrave MacMillan.