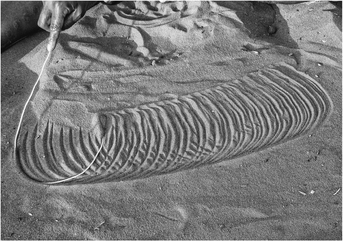

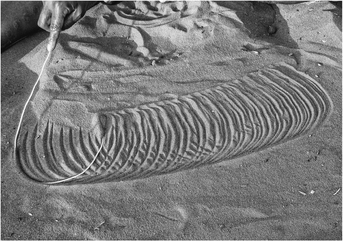

Figure 1.8.1 Using the story-wire (Photo: J. Green)

Jennifer Green

Human interactions consist of a creative bricolage of the resources a culture brings to its communicative tasks. As well as speaking, people might point to real and imagined entities and locations, manipulate fictive objects in the air with their hands, create traces, maps and diagrams, use writing systems, and make permanent or semi-permanent marks on a range of surfaces. Sign languages are the primary mode of communication for some, and for others sign is used either alongside speech, or instead of speech in particular cultural contexts. Tangible items such as tools, technologies and other aspects of the social and environmental context might also be employed (Goodwin and LeBaron 2011; Nevile, Haddington, Heinemann and Rauniomaa 2014). Understanding why particular ways of communicating meaning take precedence over others, and modelling exactly how this complexity is orchestrated remains one of the challenges for understanding human language.

Recent work in linguistics and in a variety of related disciplines has led to a growing recognition of the multimodal nature of human communication (Kendon 2004; Enfield 2009; Jewitt, Bezemer and O’Halloran 2016). Moving away from speech or text-only perspectives it is now the norm to see language as ‘embedded within an interactional exchange of multi-modal signals’ (Levinson and Holler 2014: 1; Vigliocco, Perniss and Vinson 2014). Although usage of the term ‘multimodal’ varies greatly, the ways that people produce and perceive communicative signals can be envisaged as falling within two major modality divisions. Speech utilizes the vocal/ auditory modality, and sign languages, gesture and systems of graphic representation utilize the kinesic/visual one. Within each modality are various systems or ‘potentials’ that convey meaning. The fundamental units of communication can thus be envisaged as ‘composite utterances’ in which elements of different semiotic systems work together (Enfield 2009).

This essay considers several of the semiotic parameters that are employed in the telling of Indigenous sand stories from Central Australia. Sand stories are a traditional narrative form in which skilled storytellers, primarily women and girls, incorporate speech, song, sign, gesture and drawing (Wilkins 1997; Munn 1973; Green 2014). In sand stories a small set of conventionalized graphic symbols are embedded in a complex semiotic field that includes various other types of actions, for example lexical manual signs, as well as speech. Such narrative practices emerge in a particular cultural and ecological niche where soft sand is readily at hand. The significance of the ground is seen on many levels. It is a locus of important information, coding movement, habitation and histories, like a vast notice board. It is a place of day-to-day habitation and relaxation, and for the seated person invites inscription. The surface of the ground is valued for its rich palette and observed in the minutiae of its seasonal variation.

Bringing an analytic perspective to understanding how the complexity of sand stories works to convey meaning raises methodological and conceptual challenges. An interdisciplinary approach to these questions can draw upon insights and methodologies from sign language and gesture studies, ethnomusicology, semiotics, psychology and anthropology, to name a few. Such an approach also presents an opportunity to ‘move beyond the empirical boundaries of existing disciplines’ (Jewitt et al. 2016: 2) and develop new approaches for data analysis that can account for phenomena that in some instances fall below the radar of academic inquiry if a narrow perspective is taken. At the methodological level, and as appreciation for the role of ‘visible bodily action’ (Kendon 2004; Seyfeddinipur and Gullberg 2014) in communication grows, many linguists are using video technologies for language documentation. This enables consideration of multiple aspects of complex utterances, and the ways that various types of action – for example, gesture, sign, drawing and eye-gaze – work together.

The thematic content of sand stories ranges from accounts of day-to-day events to performances of traditional narratives that are closely associated with the topography of the land and its ancestral progenitors or ‘Dreamings’. In remote Indigenous Australia, particularly in the pretelevision era, sand stories were a form of popular entertainment. For children, they provide a context for developing a range of spatial and graphic skills, as well as training and practice in the verbal arts. Although some knowledge of the ways these stories were told in the past is highly endangered, the form is still used, even as the practice is adapting to meet changing social contexts.

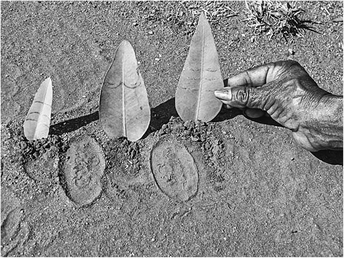

Sand stories begin with the clearing of a space on the ground in front of the narrator. The resultant drawings and mini-installations of objects are both product and process, and involve a complex interplay between dynamic and static elements. The semi-permanence of the graphic marks made on the ground is subservient to broader rhetorical aims as the story unfolds. Between ‘scenes’ or ‘episodes’ the seated narrator wipes the space on the ground in front of them clean before beginning to draw again. Drawing on the ground is done with the hand, or with sticks or wires (Figure 1.8.1). A story-wire is multi-functional, used as a drawing instrument and as a tool to point with. Story-wires are also used to provide rhythmic accompaniment, and repeated tapping of the wire on the ground embellishes the soundscape, sustains the attention of interlocutors and propels the narrative forward. Small leaves are sometimes used to represent story characters and the narrator choreographs these embodied objects on the sand space in front of them, which some have likened to a miniature stage set (Figure 1.8.2).

In sand stories a small repertoire of linear, curvilinear, circular and spiral graphic forms represent people, plants, artefacts, domestic items and other aspects of local environments. One of the most common of these is the ‘U’ shape which represents ‘person’, and this graphic form bears an iconic resemblance to the imprint on the sand made by a seated person. The ways that these simple elements are combined to generate new meanings suggests that the graphic forms of sand drawing have a rudimentary syntax. As can be seen in Figure 1.8.2, a semi-conventionalized oval shape drawn on the ground and representing a wooden dish can co-occur in the context of an arrangement of leaves that represent people. Their age and gender are conveyed by the relative size of the leaves and by the faint traces inscribed on them, derived from the painted designs that women wear when they perform ceremonies. Other lines drawn in the sand are traces of movement, re-enacting ancestral pathways or representing everyday journeys (Ingold 2007; Munn 1973; Green 2014). Varying the speed and rhythm with which a line is drawn or a leaf is moved in these narratives evokes particular types of action. For example, the graphic traces of sporadic or staccato movements are associated with dancing, while unbroken lines may be visual representations of journeys between locations that have been previously inscribed on the drawing space. These aspects of the semantic complex may be observed in real-time, or deduced from the traces that actions leave on the sand.

Figure 1.8.1 Using the story-wire (Photo: J. Green)

Figure 1.8.2 Small objects such as leaves are used to represent narrative characters (Photo: J. Green)

Another feature of lines drawn in sand stories is that they tend to be accurately configured in space, in what Wilkins has referred to as a ‘geo-centred absolute frame of reference’ (Wilkins 1997: 143). They convey correct spatial information, just as deictic or pointing gestures tend to do in Indigenous communities in Central Australia and in many other places in the world. So a line, particularly one representing motion, drawn in an east to west trajectory will be generally interpreted as indicating motion on that cardinal axis, rather than in an arbitrary unspecified direction.

Figure 1.8.3 An action results in a mark on the ground and ends with a deictic gesture in the air (video still, Eileen Pwerrerl Campbell, Ti Tree 2007) (Green 2014: 164)

At the micro-analytic level, disassembling sand stories into a series of semantically coherent action units or ‘moves’ shows how units of action in sand stories are not amenable to bounded categories. The ‘burden of information’ (Levinson and Holler 2014: 1) may shift from one means of expression to another, and be distributed across different media. Let us follow a simple action that illustrates this point. The narrator’s hand moves seamlessly across the soft surface of the ground, leaving a visible trace before moving into the air in a unitary action that crosses media – the earth and the air (Figure 1.8.3). This action disrupts pre-conceived notions of what the boundaries between gesture and drawing might be and demonstrates the semiotic possibilities of communicative actions that have graphic consequences. In the example shown in Figure 1.8.3, spatial information is distributed between the graphic traces on the ground and the pointing gesture in the air. This composite action that crosses media coheres as a semantic whole.

The types of vocal performance found in sand drawing are similarly complex, and without an interdisciplinary and collaborative approach that draws on insights from linguistics and musicology some of the richness of these vocal repertoires might be lost or overlooked. In addition to conventionalized or arbitrary aspects of spoken language that are amenable to traditional linguistic analyses, there are idiosyncratic vocal effects and poetic devices that add rhetorical flavour and texture to performances. Some sand stories include song, and repeated song texts may punctuate longer texts that are more speech-like. Some vocal phenomena fall on a continuum between sounds that are characterized as more like ‘speech’ and those that sound more like ‘song’. Moving between vocal performances that are either more song-like or more like ordinary speech has the pragmatic effect of signalling degrees of formality of a sand story. An interdisciplinary methodology helps to investigate the relationship between various aspects of speech, such as pitch, intonation and rhythm, and features of music or song – beats, melody and musical rhythms. Delineating the similarities and differences between sand story songs and other song repertoires from Central Australia leads to a more sophisticated understanding of the ethnopoetics of the verbal arts from that region, and, more generally, of the diversity of verbal art forms world-wide.

In the Indigenous sand drawing tradition from Central Australia the integration of diverse communicative resources is complex and aesthetically appealing. Understanding how sand stories work provides an insight into the narrative traditions of an ancient culture. As a case study in complexity, enriched by an interdisciplinary approach, it contributes to the theory and analysis of multimodality in human communication, and shows how communicative messages that draw on multiple modalities are integrated. Developing tools for the analysis of multimodal narrative performances such as these challenges disciplinary boundaries and leads the study of ‘language’ in a new direction. This approach highlights similarities and differences between differing theoretical perspectives and research domains. More broadly it contributes to understandings of the human language capacity, its relationship to other aspects of cognition, and the role that various types of human action play in communication.

Enfield, N. J. (2009). The Anatomy of Meaning: Speech, Gesture, and Composite Utterances. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Goodwin, C. and LeBaron, C. (2011). Embodied Interaction: Language and Body in the Material World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Green, J. (2014). Drawn from the Ground: Sound, Sign and Inscription in Central Australian Sand Stories. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ingold, T. (2007). Lines: A Brief History. Abingdon: Routledge.

Jewitt, C., Bezemer, J. and O’Halloran, K. (2016). Introducing Multimodality. Abingdon: Routledge.

Kendon, A. (2004). Gesture: Visible Action as Utterance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Levinson, S. C. and Holler, J. (2014). The origin of human multi-modal communication. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 369(1651): 20130302–20130302. doi:10.1098/rstb.2013.0302.

Munn, N. D. (1973). Walbiri Iconography: Graphic Representation and Cultural Symbolism in a Central Australian Society. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

Nevile, M., Haddington, P., Heinemann, T. and Rauniomaa, M. (2014). Interacting with Objects: Language, Materiality, and Social Activity. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Seyfeddinipur, M. and Gullberg, M. (2014). From Gesture in Conversation to Visible Action as Utterance. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Vigliocco, G., Perniss, P. and Vinson, D. (2014). Language as a multimodal phenomenon: implications for language learning, processing and evolution. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 369(1651): 20130292–20130292. doi:10.1098/rstb.2013.0292.

Wilkins, D. P. (1997). Alternative representations of space: Arrernte narratives in sand. Proceedings of the CLS Opening Academic Year, 97(98): 133–164.