Chapter 14

Homeostasis

Volume depletion and dehydration

HOW TO . . . Administer subcutaneous fluid

Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion

HOW TO . . . Perform a short ACTH stimulation test (short Synacthen® test)

Volume depletion and dehydration

An important, common, easily missed clinical condition, especially in older people. Highly prevalent among acutely unwell older people admitted to hospital due to a combination of ↑ fluid loss (fever, gastrointestinal loss) and ↓ intake (nausea, anorexia, weakness).

Causes

Often multifactorial and include:

• Gastrointestinal losses (e.g. diarrhoea, NG drainage)

• Sequestration of fluid (e.g. ileus, burns, peritonitis)

Symptoms and signs

• Thirst is uncommon in older people

• Orthostatic symptoms (light-headedness or syncope) and/or postural hypotension. Use passive leg raising for recumbent patients (raise legs by 45° and recheck BP. Improvement suggests volume depletion)

• Nausea, anorexia, vomiting, and oliguria in severe uraemia

• Tachycardia, supine hypotension (late signs, also in fluid overload)

• ↓ skin turgor, sunken facies, absence of dependent oedema

The symptoms and signs of clinically important dehydration may be subtle and confusing. It is therefore under-recognized. Continual clinical assessment, assisted by basic tests (urinalysis; U, C+E), is essential. Invasive monitoring or other tests are rarely needed.

Older patients commonly become dehydrated because:

• They are ‘run dry’ on the wards, as medical (and nursing) staff fear precipitating acute pulmonary oedema through excessive iv fluid administration

• iv infusions often run more slowly than prescribed or cannot run for periods if iv access is lost

• Moderate leg oedema is very poorly specific for heart failure—do not treat this sign alone, in the absence of supporting evidence, with diuretic

► Poor urine output on the surgical (or medical) wards is more often a sign of dehydration than of heart failure. Improving urine volume with diuretics is the wrong treatment.

► There is no sensitive biochemical marker of dehydration—urea and creatinine are commonly in the normal range and may be abnormal when normally hydrated (e.g. in CKD).

Challenges to volume status assessment in elderly patients

This can be difficult and requires care.

There is no gold standard in routine clinical examination, although a capillary wedge pressure will give a reliable estimate in ITU/HDU settings.

Most symptoms and signs can occur in both fluid overload and dehydration—use multiple indicators to make an overall decision about volume status.

Use serial assessments, and if the response to treatment is not as anticipated, review your judgement.

Symptoms

• Thirst is often absent in dehydration

• Confusion can occur in dehydration and fluid overload

• Breathlessness may occur in fluid overload, but also in, e.g. chest sepsis with dehydration

Signs

• Tachycardia may occur in dehydration (may be absent if there is β- blockade) but also occurs in cardiac failure

• Hypotension similarly occurs both in dehydration and cardiac failure. A postural drop is more likely to indicate dehydration but may also be induced by medication or autonomic dysfunction

• Look at the skin turgor—choose a site away from peripheral oedema, e.g. the forehead. Pinch the skin gently and see how quickly it returns to normal. A sluggish response indicates dehydration

• Check for peripheral oedema—remember that in a bed-bound patient, this may collect in the sacral region. It is possible to have peripheral oedema with intravascular depletion (e.g. in hypoalbuminaemia), so this is not a reliable indicator of fluid state

• Check the JVP, which is elevated in cardiac failure and also in tricuspid regurgitation

Investigations

• Urine specific gravity may be high in dehydration, and also in heart failure, and is less helpful when diuretics have been used

• Elevated U, C+E often indicate dehydration—check for the patient’s baseline, if possible. CKD will also elevate urea and creatinine but is likely to be chronic. Remember that frail older people will have a lower creatinine (perhaps even in the normal range) because of low muscle bulk, but this may still represent a marked abnormality for them

• Elevated Hb may occur in dehydration and in chronic hypoxia

Dehydration: management

• Treat the underlying cause(s)

• Suspend diuretic and ACE inhibitors

• Continually reassess clinically, assisted by urinalysis/U, C+E. Measure and document intake, output, BP, and weight

• If mild: oral rehydration may suffice. A ‘homemade’ oral rehydration mixture can be made by adding a level teaspoon of salt and eight level teaspoons of sugar to a litre of water with a touch of fruit juice. Older people may need time, encouragement, and physical assistance with drinking. Enlist relatives and friends to help

• More severe dehydration, or mild dehydration not responding to conservative measures, will require other measures—usually parenteral treatment, either s/c (see  ‘HOW TO . . . Administer subcutaneous fluid’, p. 405) or iv

‘HOW TO . . . Administer subcutaneous fluid’, p. 405) or iv

• The speed of parenteral fluid administration should be tailored to the individual patient, based on volume of fluid deficit, degree of physiological compromise, and perceived risks of fluid overload. For example, a hypotensive patient who is clinically volume-depleted with evidence of end-organ failure should be fluid-resuscitated briskly, even if there is a history of heart failure. In the absence of end-organ dysfunction, rehydration may proceed more cautiously, but continual reassessment is essential to confirm that the clinical situation remains benign and that progress (input > output) is being made

HOW TO . . . Administer subcutaneous fluid

This method was widely used in the 1950s but fell into disrepute following reports of adverse effects associated with very hypo-/hypertonic fluid. Fluids that are close to isotonic delivered by competent staff are a safe and effective substitute for iv therapy.

• A simple, widely accessible method for parenteral fluid/electrolytes

• Fluid is administered via a standard giving set and fine (21–23G) butterfly needle into s/c tissue, then draining centrally via lymphatics and veins

• s/c fluid administration should be considered when insertion or maintenance of iv access presents problems, e.g. difficult venous access, persistent extravasation, or lack of staff skills

• iv access is preferred if rapid fluid administration is needed (e.g. gastrointestinal bleed) or if precise control of fluid volume is essential

Sites of administration

Preferred sites: abdomen, chest (avoid the breast), thigh, and scapula. In agitated patients who can tear out iv (or s/c) lines, sites close to the scapulae may foil their attempts.

Fluid type

Any crystalloid solution that is approximately isotonic can be used, including normal (0.9%) saline, 5% glucose, and any isotonic combination of glucose–saline. Potassium chloride can be added to the infusion, in concentrations of 20–40mmol/L. If local irritation occurs, change site and/or reduce the concentration of added potassium.

Infusion rate

Typical flow (and absorption) rate: 1mL/min or 1.5L/day. Infusion pumps may be used. If flow or absorption is slow (leading to lumpy, oedematous areas):

• Use two separate infusion sites at the same time

• Using these techniques, up to 2L of fluid daily may be given. For smaller volumes, consider an overnight ‘top-up’ of 500–1000mL, or two daily boluses of 500mL each (run in over 2–3h), leaving the patient free of infusion lines during daily rehabilitation/activity. Some patients need only 1L/alternate nights to maintain hydration

Monitoring

Patients should be monitored clinically (hydration state, input/output, weight) and biochemically as they would if they were receiving iv fluid.

► Be responsive and creative in your prescriptions of fluid and electrolytes. One size does not fit all.

Potential complications

Rare and usually mild. They include local infection and local adverse reactions to hypertonic fluid (e.g. with added potassium).

Contraindications

• Exercise caution in thrombocytopenia or coagulopathy

• s/c infusion is not appropriate in patients who need rapid volume repletion

Hyponatraemia: assessment

A common problem. May be safely monitored, rather than treated, if modest in severity ([Na] >125mmol/L), stable, and without side effects, and if there is an identifiable (often drug) cause.

Clinical features

• Subtle or absent in mild cases

• [Na] = 115–125mmol/L: lethargy, confusion, altered personality

• At [Na] <115mmol/L: delirium, coma, seizures, and death

Causes

Iatrogenic causes are the most common. Acute onset, certain drugs, or recent iv fluids make iatrogenesis especially likely.

Important causes include:

• Drugs. Many are implicated (see Box 14.1)

• Excess water administration—either NG (rarely po) or iv (5% glucose)

• Failure of heart, liver, thyroid, kidneys

• Stress response, e.g. after trauma or surgery, exacerbated by iv colloid or 5% glucose

• Hypoadrenalism: steroid withdrawal or Addison’s disease

• Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH)

In older people, multiple causes are common, e.g. heart failure, diuretics, and acute diarrhoea.

Approach

Take a careful drug history, including those stopped in the past few weeks. Examine to determine evidence of the cause and volume status (JVP, postural BP, pulmonary oedema, ankle/sacral oedema, peripheral perfusion).

Investigations

Clinical history and examination, urine, and blood biochemistry are usually all that are needed. Ensure that the sample was not delayed in transit or taken from a drip arm. If genuine hyponatraemia, take:

• Blood for creatinine, osmolarity, TFTs, LFTs, glucose, random cortisol

• Spot urine sample for sodium and osmolarity

Consider a short adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) test to exclude hypoadrenalism, particularly if the patient is volume-depleted and hyperkalaemic (see  ‘HOW TO . . . Perform a short ACTH stimulation test (short Synacthen® test)’, p. 411).

‘HOW TO . . . Perform a short ACTH stimulation test (short Synacthen® test)’, p. 411).

Hyponatraemia: treatment

• Combine normalization of sodium with correction of fluid volume and treating underlying cause(s)

• The rate of correction of hyponatraemia should not be too rapid. Usually, correction to the lower limit of the normal range (~130mmol/L) should be achieved in a few days. Maximum correction in any 24h period should be <10mmol/L. Full correction can reasonably take weeks

• Acute, severe hyponatraemia with moderate/severe symptoms such as seizures, should be considered for treatment with hypertonic saline to reduce the risk of complications

• Rapid correction risks central pontine myelinolysis (leading to quadriparesis and cranial nerve abnormalities) and is indicated only when hyponatraemia is severe and the patient critically unwell

► By definition, hyponatraemia is a low blood sodium concentration. Therefore, a low level may be a result of low sodium, high water, or both. Dehydration and hyponatraemia may coexist if sodium depletion exceeds water depletion. This is common—do not worsen the dehydration by fluid-restricting these patients.

Box 14.1 Drugs and hyponatraemia

• Most commonly diuretics (especially in high dose or combination), SSRIs, carbamazepine, NSAIDs

• Other drugs include opiates, other antidepressants (MAOIs, tricyclic antidepressants), other anticonvulsants (e.g. valproate), oral hypoglycaemics (sulfonylureas, e.g. glipizide), PPIs, ACE inhibitors, and barbiturates

• Combinations of drugs (e.g. diuretic and SSRI) are especially likely to cause hyponatraemia

• If hyponatraemia is problematic and the treatment is needed, consider other drugs that are less likely to cause a low sodium (e.g. mirtazapine for depression)

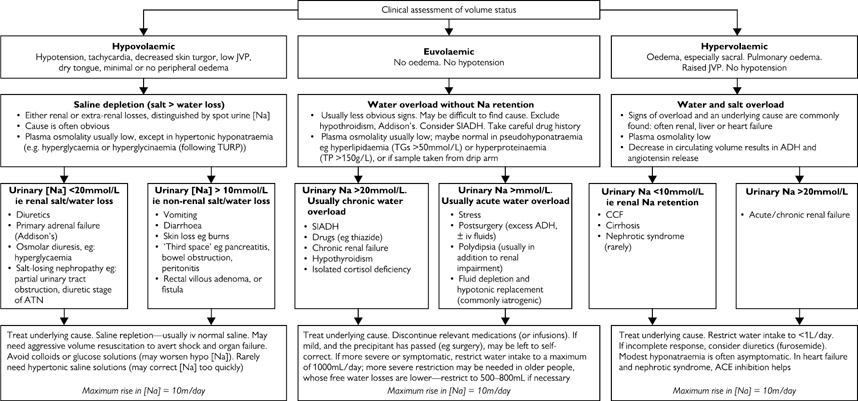

Fig. 14.1 Hyponatraemia: aetiology and treatment. TG, triglyceride; TP, turgor pressure; TURP, transurethral resection of the prostrate.

Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion

Definition

Less than maximally dilute (i.e. inappropriately concentrated) urine in the presence of subclinical excess body water.

► SIADH is massively over-diagnosed, especially in older people, leading to inappropriate fluid restriction. Consider it a diagnosis of exclusion—drugs or organ impairment cause a similar clinical syndrome.

Diagnosis

Essential features include:

• Hypotonic hyponatraemia ([Na] <125mmol/L and plasma osmolarity <260mOsm/L)

• Normal volume status, i.e. euvolaemia—there is slight water overload, but not clinically identifiable

• Normal renal, thyroid, hepatic, cardiac, and adrenal function

• Inappropriately concentrated, salty urine: osmolarity >200mOsm/L and [Na] >20mmol/L)

• No diuretics, or ADH-modulating drugs (opiates, anticonvulsants, antidepressants, NSAIDs, barbiturates, and oral hypoglycaemics). Drug effects may take days or weeks to diminish

Causes

Common causes include:

• Neoplasms (especially bronchogenic, pancreatic)

• CNS disease (especially trauma, subdural haematoma, stroke, meningoencephalitis)

• Lung disease (TB, pneumonia, bronchiectasis)

• Some drugs cause low sodium by an SIADH-like effect, but this is not the true syndrome

Treatment

• If mild, and the precipitant has passed (e.g. surgery), may be left to self-correct

• If more severe and/or symptomatic, restrict water intake to a maximum of 1000mL/day; more severe restriction may be needed in older people whose free water losses are lower—restrict to 500–800mL, if necessary

• Drug treatments are generally reserved for refractory cases or where fluid restriction is not tolerated. Demeclocycline acts by blocking the renal tubular effect of ADH and is first line. Vasopressin receptor antagonists can also be used (e.g. tolvaptan)

HOW TO . . . Perform a short ACTH stimulation test (short Synacthen® test)

The diagnosis of adrenocortical insufficiency is made when the adrenal cortex is found not to synthesize cortisol despite adequate stimulation. Within 30min of ACTH stimulation, the normal adrenal releases several times its basal cortisol output.

Performing the test

• The test can be done at any time of the day

• Steroid treatment (e.g. prednisolone) may invalidate results; these should be stopped at least 24h before the test. Oestrogens should also be suspended

• Take blood for baseline cortisol. Label the tube with patient identifiers and the time taken

• Give 250 micrograms of Synacthen® (synthetic ACTH, 1-24 amino acid sequence). Give iv if iv access is present; otherwise im

• Thirty minutes after injection, take more blood for cortisol. Label the tube with patient identifiers and the time taken

Interpreting the test

A normal response meets three criteria:

• Baseline cortisol level >150nmol/L

• 30min cortisol greater than baseline cortisol by 200nmol/L or more

The absolute 30min cortisol carries more significance than the baseline–30min increment, especially in patients who are stressed (ill) and at maximal adrenal output.

A normal Synacthen® test excludes Addison’s disease. If the test is not normal:

• Consider further tests, such as the prolonged ACTH stimulation test, usually after specialist advice, e.g.:

• ACTH level (elevated in 1°, and low in 2°, hypoadrenalism)

• The prolonged ACTH stimulation test

• If the patient is very unwell, give hydrocortisone 100mg iv, pending confirmation of hypoadrenalism

Hypernatraemia

Causes

• Usually due to true ‘dehydration’, i.e. water loss > sodium loss

• Not enough water in, or too much water out, or a combination, e.g. poor oral intake, diarrhoea, vomiting, diuretics, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus

• Rarely due to salt excess—iatrogenic (iv or po), psychogenic, or malicious (poisoning)

• Very rarely due to diabetes insipidus (urine osmolarity low) or mineralocorticoid excess (Conn’s syndrome)

Commonly seen in older people with sepsis: ↑ losses (sweating), reduced oral intake, and reduced renal concentrating (water-conserving) mechanism.

Clinical features

• Hypotension (supine and/or orthostatic)

• Urine scanty and concentrated

• Lethargy, confusion, coma, and fits

Tests

Urea and creatinine are often high but may be in the high normal range; the patient is still water-depleted. Potassium is low in Conn’s. Hb and albumin are often high (haemoconcentration), correcting with treatment.

Treatment

• Usually iv fluid is required; rarely s/c fluid will be sufficient

• Fluid infusion rates should not be too cautious, e.g. 3L/24h is reasonable, guided by clinical and biochemical response. Too rapid infusions risk cerebral oedema, especially in the more chronically hypernatraemic patient

• Ensure the patient becomes clinically euvolaemic, as well as normo-natraemic—most dehydrated patients have a normal [Na] and will correct into the normal range before the patient is fully hydrated

• Many patients are sodium-deplete, as well as water-deplete; therefore, consider alternating normal saline with 5% glucose infusions

► Even mild hypernatraemia is usually clinically important and needs attention.

Hypothermia: diagnosis

A common medical emergency in older people, occurring both in and out of hospital.

Definition

• Core temperature <35°C, but <35.5°C is probably abnormal

• Mild: 32–35°C; moderate: 30–32°C; severe: <30°C

• Fatality is high and correlates with severity of associated illness

Causes

Often multifactorial.

• Illness (drugs, fall, sepsis)

• Defective homeostasis (failure of autonomic nervous system-induced shivering and vasoconstriction; ↓ muscle mass)

• Cold exposure (clothing, defective temperature discrimination, climate, poverty)

In established hypothermia, thermoregulation is further impaired and is effectively poikilothermic (temperature varies with the environment).

► Hypothermia is a common presentation of sepsis in hospital in older people, and probably an indicator of poor prognosis. Do not ignore the temperature chart.

Diagnosis

Rectal temperature is the gold standard, but well-taken oral or tympanic temperature will suffice.

Ensure the thermometer range includes low temperatures (mercury-in-glass thermometer range usually 34–42°C, thereby underestimating severity in all but the mildest cases).

Presentation

Often insidious and non-specific. The patient will frequently not complain of feeling cold. Multiple systems affected.

• Skin: may be cold to touch (paradoxically warm if defective vasoconstriction). Shivering is unusual (this occurs early in the cooling process). There may be ↑ muscle tone, skin oedema, erythema, or bullae

• Nervous system: signs can mimic stroke with falls, unsteadiness, weakness, slow speech, and ataxia. Reflexes may be depressed or exaggerated, with an abnormal plantar response and dilated, sluggish pupils. Conscious level ranges from confused/sleepy to coma. Seizures and focal signs can occur

• Initially vasoconstriction, hypertension, and tachycardia

• Then myocardial suppression, hypotension, sinus bradycardia

• Eventually extreme bradycardia, bradypnoea, and hypotension. May lead to false diagnosis of death; however, the protective effect of cold on vital organs means survival may be possible

• Dysrhythmias include AF (early), VF, and asystole (late)

• Renal: there is early diuresis, with later oliguria and ATN

• Respiratory: respiratory depression and cough suppression occur with 2° atelectasis and pneumonia. Pulmonary oedema and ARDS occur late

• Gastrointestinal: hypomotility may lead to ileus, gastric dilation, and vomiting. Hepatic metabolism is reduced (including of drugs). There is a risk of pancreatitis with hypo- or hyperglycaemia

• Other: disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), pressure injuries, and rhabdomyolysis

Investigations

• CK and urinalysis (may show rhabdomyolysis)

• ABGs (looking for metabolic and respiratory acidosis and lactate. Do not correct for temperature)

• ECG (abnormalities include prolonged PR interval, J waves (peak between QRS and T in leads V4–6) at <30°C, and dysrhythmia)

• Serum cortisol (consider if there are features of hypoadrenalism or hypothermia is unexplained or recurrent)

► It is important to repeat key investigations during rewarming, e.g. U, C+E, ECG, and ABGs.

Hypothermia: management

Monitoring

Regular BP, pulse, temperature, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, and glucose; continuous ECG; consider urinary catheter. Consider ITU.

Treatment principles

• Mild hypothermia should be managed with gentle warming and close monitoring

• The features of severe hypothermia may mimic those of death. Begin resuscitation while gathering information that permits a decision as to whether further intervention is likely to be futile or else not in the patient’s interests. Stop resuscitation according to clinical judgement; generally do not declare dead until re-warmed or re-warming fails

• Re-warming: rate should approximate that of onset (0.5–1°C/h if not critically unwell). Caution, as re-warming may lead to hypotension. A combination of the following modalities is usually sufficient:

• Passive external: surround with dry clothes and blankets/space blankets

• Active external: hot air blanket (‘Bair HuggerTM’), hot water bottle, bath

• Active internal: heated oxygen, fluid, and food

• System support: maintain airway, ventilate as necessary. Good iv access. Warm iv fluid: may need large volumes as warming causes vasodilatation. Treat organ dysfunction as appropriate. Cardiac pacing only if bradycardia is disproportionate to reduced metabolic rate

• If severe, or multiple organ failure, consider ITU. Handle carefully—rough handling and procedures (including intubation) may precipitate VF

Sudden, severe hypothermia ± cardiac arrest (e.g. due to water immersion) is uncommon in older people. If it occurs, manage in the usual way with rapid, invasive re-warming, supported by ITU.

Drug treatment

Consider:

• Empirical antibiotics (most have evidence of infection on careful serial assessment)

• Adrenal insufficiency (treatment: hydrocortisone 100mg qds)

• Hypothyroidism (treatment: liothyronine 50 micrograms, then 25 micrograms tds iv, always with hydrocortisone)

• Thiamine deficiency (malnourished or alcoholic) (treatment: B vitamins oral or iv) (as Pabrinex®)

Drug metabolism is reduced, and accumulation can occur. Efficacy at the site of action is also reduced. Exercise caution with s/c and im drugs (including insulin) that may accumulate and be mobilized rapidly as perfusion improves.

Prevention

Before discharge, establish why this episode occurred—is recurrence likely? (Consider housing, cognition, hypoglycaemia, sepsis, etc.) Consider how further episodes may be prevented or terminated early.

HOW TO . . . Monitor temperature

No method is absolutely precise.

• Traditional mercury-in-glass thermometers are now rarely used in hospital, having been replaced due to risks to patients, staff, and the public

• Digital electronic and infrared thermometers can provide reliable results when used correctly and in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions

• Thermochromic (forehead) thermometers are imprecise, although they may be useful for screening or with uncooperative patients

Digital electronic thermometers

These may permit oral, axillary, or rectal measurement. They typically require a small period of equilibration and patient compliance.

Infrared (‘tympanic’) thermometers

These measure the temperature of tissue within, and close to, the eardrum, returning a value rapidly. Ensure that the earlobe is gently pulled posteriorly and superiorly, straightening the external ear canal, before inserting the probe fairly firmly.

Ear wax has only a slight effect, reducing measured temperature by <0.5°C.

Note that tympanic thermometers may offer a choice of displaying temperature as either ‘true tympanic’ or the derived value ‘oral equivalent’. Ensure that you are familiar with the thermometer in use in your hospital and what output they give—tympanic or ‘oral equivalent’.

Measurement in practice

• Precise temperature measurement is fundamental to detecting and monitoring disease

• Fever may be due to infection, malignancy, inflammation, connective tissue disease, or drugs

• A reduced or absent fever response to sepsis is seen in some elderly patients. Do not dismiss modest fever (<37.5°C) as insignificant or rule out infection because the patient is afebrile

• Hypothermia occurs inside and outside hospital and may be missed, unless thermometers with an appropriate range (30–40°C) are used

• Temperature varies continuously—lowest in peripheral skin, highest in the central vessels and brain. No site is truly representative of the ‘core’ temperature. Typically, when compared with oral temperature, axillary temperatures are 1.0°C lower, and rectal and tympanic temperatures 0.5–1.0°C higher (but see notes on tympanic thermometry, also in this box)

• Where clinical suspicion is high, make measurements yourself, complementing monitoring by nursing staff. Body temperature changes continuously, and a fever may manifest only after the patient has re-warmed following a cooling ambulance journey

• The hand on the forehead to assess core temperature (and on the palm of the hand to determine peripheral vasodilation) is of value in screening for sepsis and can be incorporated into daily rounds without time penalty

Heat-related illness

An important cause of morbidity and mortality in older people, but the risk is much less appreciated than that of hypothermia. The contribution of heat stress to death is rarely mentioned on death certificates, but epidemiological studies indicate significant excess morbidity and mortality during extended periods of unaccustomed hot weather (e.g. France 2003: 15 000 excess deaths). There is an ↑ incidence of acute cerebrovascular, respiratory, and especially cardiovascular disease.

Risk factors

• Consider older people as being relatively poikilothermic, i.e. lacking close control of body temperature in some circumstances

• Homeostasis is weakened due to raised sweating threshold, reduced sweat volume, altered vasomotor control, and behavioural factors (lessened sensation of temperature extremes)

• Climate: high temperature, high radiant heat (sitting in sunshine, indoors or out), high humidity

• Drugs, e.g. diuretics, anticholinergics, psychotropics

• Comorbidity: frailty, cerebrovascular and cardiovascular disease

A spectrum of illness

The presentation is usually different in older people, typically occurring not after extreme exertion, but during heatwaves in temperate zones.

• Prickly heat (‘miliaria’): itchy, erythematous, papular rash. Treatment: cool, wash, antihistamines

• Heat oedema: peripheral oedema, usually self-limiting

• Heat syncope: ↑ syncope risk due to fluid depletion and vasodilation

• Heat exhaustion: is a potentially catastrophic illness. Dehydration and heat stress leads to non-specific presentation with collapse, immobility, weakness, vomiting, dizziness, headache, fever, and tachycardia. However, treatment should result in rapid improvement

• Heat stroke occurs when untreated heat exhaustion progresses to its end-stage (hyperthermic thermoregulatory failure). Core temperature is generally >40°C; mental state is altered (confusion → coma); circulatory and other organ failure is common, and sweating is often absent. CNS changes may be persistent and severe. Prognosis reflects pre-existing comorbidity, severity, and complications, and is often poor

Management

• Individual response. Emergency inpatient treatment required. Identify and reverse precipitants. Cool rapidly until temperature 38–39°C—fan, tepid sponging, remove clothing. Close monitoring (temperature, BP, pulse saturation, urine output); consider invasive central venous pressure monitoring. Cool iv fluids according to assessment of fluid/electrolyte status

• Community response. Local environment modification—fans, air conditioning, shade windows, open windows at night, seek cooler areas, avoid exercise, maintain or ↑ cool fluid intake, light/loose clothing. Education of patient and carers. Governments should have public health measures in place to reduce the impact of heat waves