Chapter 17

Musculoskeletal system

HOW TO . . . Manage non-operative fractures

HOW TO . . . Manage steroid therapy in giant cell arteritis

HOW TO . . . Grade muscle strength

HOW TO . . . Aspirate/inject the knee joint

Cervical spondylosis and myelopathy

Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common joint disorder in older patients, causing massive burden of morbidity and dependency. It is not inevitable with ageing.

It is a disorder of the dynamic repair process of synovial joints, causing:

• Loss of articular cartilage (joint space narrowing)

• New growth of cartilage and bone (osteophytes)

Inherited factors determine susceptibility, but individual genes are not identified. ↑ age is the strongest risk factor. ♀ and those with high bone density are at higher risk. Obesity, trauma, and repetitive adverse loading (e.g. miners or footballers) are potentially avoidable factors. ‘Burnt-out’ rheumatoid arthritis or neuropathic joints (e.g. in diabetes), as well as congenital factors (e.g. hip dysplasia), can result in 2° OA.

Clinical features

• Pain—assess severity, impairment, and impact on life. Usually insidious in onset and variable over time, worse with activity, and relieved by rest. Chronic pain may cause poor sleep and low mood

• Only one or a few joints are affected with minimal morning stiffness and often worsening of symptoms during the day

• Restricted movement, e.g. walking, dressing, rising from a chair

• Severe OA can contribute to postural instability and falls

Examination

• Heberden’s nodes (asymptomatic bony swellings on distal fingers) associated with inherited knee OA

• Limp with jerky ‘antalgic’ gait

• Knees may be valgus (knees together, feet apart—‘knock-knees’), varus (knees apart, foot inwards—‘bow-legged’), or flexion deformity

• Hip shortening/flexion (check on couch by flexing the opposite hip to see if the affected hip lifts off the bed—Thomas’ test)

• Restricted range of movement

Investigations

► OA is a clinical diagnosis. Symptoms correlate poorly with radiological findings. The main role of X-ray is in assessing severity of structural change prior to surgery. Features include joint space narrowing, osteophytes, sclerosis, cysts, and deformity. Blood tests are normal, even when an osteoarthritic joint feels warm—reconsider your diagnosis if inflammatory markers are elevated.

Osteoarthritis: management

OA is the most common chronic painful condition. Drug dependence and side effects can be a big problem.

► Always consider non-pharmacological treatments first.

Non-drug treatments

• Exercise: aerobic and focal muscle strengthening. Swimming, yoga, and t’ai chi are particularly good. PT may help. Encourage the patient to exercise despite the pain—no harm will be done

• Heat/cold packs: but be very careful to avoid burns in patients who may have ↓ temperature awareness

• Weight loss: not a quick fix but influences other health outcomes

• Sensible footwear: soft soles with no heels. Trainers are ideal

• Walking aids, e.g. stick (in contralateral hand)

• Education and support: self-management programmes are helpful

• Osteopaths or chiropractors: help some patients but are expensive

Drug treatments

Patients should be offered regular paracetamol in adequate dose before moving onto drugs with greater side effect profiles. Patients may need persuading to try a regular prophylactic dose, perceiving it as a ‘weak’ drug.

• Topical NSAIDs can be helpful and are lower risk than oral

• The next step is to add a low-potency opiate—often combined with paracetamol. Beware constipation and sedation

• A short course of oral NSAIDs can be useful in acute exacerbations, but avoid long-term use. If NSAIDs are used for >1 week or in the presence of known dyspepsia or ulceration, reduce the gastrointestinal risk by co-prescribing, e.g. lansoprazole 15mg od. The cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX-2) selective inhibitors have better gastrointestinal tolerability but have ↑ vascular adverse events and so have fallen out of favour. Both can worsen heart failure

• Intra-articular steroids can be rapidly effective, particularly if the joint is hot/very painful. There is a substantial placebo effect, but symptoms tend to recur after 4–6 weeks. Side effects limit use to four injections/joint/year. The cumulative systemic effect risks osteoporosis

• Counter-irritants, e.g. capsaicin cream, are safe and have some effect

• Oral chondroitin and glucosamine are available unlicensed over-the-counter, but there is little evidence of benefit

Surgical treatment

Includes cartilage repair, osteotomy, and joint replacements. Arthroscopic debridement/lavage has limited evidence and should not be offered unless locking. Indications include pain, deformity, or joint instability where other treatments have failed. Outcomes can be excellent for fitter older people, but cases should be carefully selected.

HOW TO . . . Manage non-operative fractures

• Fractures that very rarely require operative intervention include the pubic rami, humerus, wrist, and vertebra

• Other fractures, often immobilized surgically in younger people, may be treated more conservatively in older patients to avoid perioperative risks (e.g. simple tibial plateau fractures may be immobilized by functional brace)

• Patients with these ‘non-operative’ fractures are often cared for by geriatricians, having been transferred either:

• From A&E to medical, ortho-medical, or ortho-geriatric units

• From orthopaedic wards for ongoing rehabilitation

• Minor fractures can result in significant functional impairment, e.g. a Colles’ fracture, and plaster of Paris (POP) may prevent an older person from washing, dressing, and toileting. Even walking may not be possible (if a frame can no longer be used)

General principles of management

These include:

• Pain control. This allows earlier mobilization and reduces the risks of immobility (pressure sores, pneumonia, thromboembolism)

• Consider novel treatments such as heat, TENS, calcitonin, bisphosphonates, or vertebroplasty for vertebral fracture

• A short course of NSAIDs is sometimes appropriate in low-risk patients, but remember to stop this as soon as possible

• Encouraging mobility and independence as early as possible. Best achieved in a rehabilitation environment. Patient and family often expect ‘bed rest’ after a fracture and may need to be educated

• Consider the mechanism of the fall and injury (see  ‘Assessment following a fall’, pp. 102–103)—are there medical risks that could be reduced? For example, sedating medication, excessive antihypertensive use, undiagnosed illnesses (e.g. urinary infection or minor stroke), need for aids/adaptations

‘Assessment following a fall’, pp. 102–103)—are there medical risks that could be reduced? For example, sedating medication, excessive antihypertensive use, undiagnosed illnesses (e.g. urinary infection or minor stroke), need for aids/adaptations

• Maintaining contact with orthopaedic colleagues. They can advise on when to replace/remove plasters and how much exercise/weight-bearing is appropriate. Ask for reassessment if progress is poor, e.g. ongoing severe pain, or apparent malunion—sometimes a diagnosis has been missed or an interval operation is needed

• A pragmatic approach to weight-bearing may be needed, e.g. in dementia (where concordance with non-weight-bearing is difficult) or where immobility causes an unacceptable rise in frailty

• Prescribing prophylactic heparin if there are multiple risk factors for thromboembolic disease or the patient is immobile

• Osteoporosis treatment (there is no current evidence that bisphosphonates reduce callus formation or delay bone union)

• Start to plan discharge early. Many patients can be managed at home with a care package and outpatient rehabilitation. Others may need transitional care beds (e.g. while they wait to be weight-bearing or for plasters to be removed), after which they can return to an active rehabilitation programme prior to going home

Further reading

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2014). Osteoarthritis: care and management. Clinical guideline CG177.  http://www.nice.org.uk/cg177.

http://www.nice.org.uk/cg177.

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is the reduction in bone mass and disruption of bone architecture, resulting in ↑ bone fragility and fracture risk. Results from prolonged imbalance in bone remodelling where resorption (osteoclastic activity) exceeds deposition (osteoblastic activity).

Osteoporosis is very common and very much under-recognized and undertreated. In combination with falls (see  ‘Interventions to prevent falls’, pp. 104–105), osteoporosis contributes to the high incidence of fractures in older people. In the UK, 50% of women aged >50 years have at least one osteoporotic fracture in their lifetime and 32% aged 90 will have had a hip fracture.

‘Interventions to prevent falls’, pp. 104–105), osteoporosis contributes to the high incidence of fractures in older people. In the UK, 50% of women aged >50 years have at least one osteoporotic fracture in their lifetime and 32% aged 90 will have had a hip fracture.

► If you make the diagnosis, do not delay initiating 2° prevention. Always think of osteoporosis when assessing post-operative orthopaedic patients or any patient who has fallen.

Pathology

• Total bone mass ↑ throughout childhood and adolescence, peaks in the third decade, and then declines at about 0.5% per year

• Bone loss is accelerated after the menopause (up to 5% per year) and by smoking, alcohol, low body weight, hyperthyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, hypoandrogenism (in men), kidney failure, and immobility

• Steroids, phenytoin (and other antiepileptics), PPIs, long-term heparin, and ciclosporin cause 2° osteoporosis

• High peak bone mass reduces later risk. Determined by genetics, nutrition (optimal BMI and calcium/vitamin D, especially in childhood), and weight-bearing exercise

• Diagnosis is complicated by the common coexistence of asymptomatic osteomalacia (defective mineralization) in older people with low sunlight exposure

Clinical features

• Osteoporosis itself is asymptomatic—it is the fractures that cause symptoms

• Often presents with a fragility (i.e. low-energy) fracture—wrist, femoral neck, or crush fracture of the vertebral body

• Wedging of vertebrae is caused because there is higher load-bearing by the anterior part of the vertebral body. This can present as:

• An incidental asymptomatic finding (in around a third)

• Progressive kyphosis (‘dowager’s hump’). The bent-over posture is not just unattractive; it causes loss of height, protuberant belly, abdominal compression, oesophageal reflux, and impaired balance with further predisposition to falls and fracture. Restricted rib movements lead to restrictive lung disease

Diagnosis

► Blood tests are normal (except after a fracture). If calcium or ALP is elevated, consider an alternative diagnosis, e.g. metastases or Paget’s disease.

• X-rays may show fractures and give an idea of bone density

• The gold standard is dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scanning (rarely employed in the elderly population, but useful in younger women). Usually two scores are quoted at the hip and spine. The T-score compares bone density to peak bone mass, while the Z-score compares it to age/sex/weight-matched sample. A T-score of <−2.5 defines osteoporosis, with scores of −1 to −2.5 indicating osteopenia

• Peripheral densitometry assessments can be done at the heel, wrist, and ankle, the advantage being that the required machine is more portable. Results correlate with formal testing, but there are concerns about reliability in the ♂ population

• Testosterone levels in men, coeliac, and myeloma testing

In patients aged >75 years, NICE guidelines allow the assumption that osteoporosis exists where there is a:

• Low-energy (a fall from standing height or less) fracture of the wrist, femoral neck, or vertebra OR

• Progressive kyphosis without features of malignancy

Primary prevention of osteoporosis

• Sensible public health measures (e.g. diet, exercise, stop smoking, reduce alcohol) should be advised but generally affect peak bone mass, i.e. too late for older people

• Prophylaxis with a bisphosphonate should be started for those taking significant steroid therapy (>7.5mg/day for more than a month) (see  ‘Osteoporosis: management’, p. 472)

‘Osteoporosis: management’, p. 472)

• HRT is no longer recommended—post-menopausal bone loss returns after it is stopped; ↑ thromboembolic, cancer, and vascular risk

• In patients with falls, osteoporotic risk should be assessed and managed (e.g. using FRAX tool,  http://www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/tool.jsp)

http://www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/tool.jsp)

Osteoporosis: management

• In patients with good calcium intake and normal serum calcium, vitamin D alone should be offered, as additional calcium in this group may cause ↑ cardiovascular mortality

• Oral calcium and vitamin D is cheap and effective, especially in frail institutionalized people (possibly due to treatment of osteomalacia and associated myopathy as much as osteoporosis). Tablets containing calcium are large and chalky, and can be unpalatable. Effervescent tablets or granules may be better tolerated. Take 1200mg calcium and 800IU vitamin D daily

• Bisphosphonates are very effective and used as first line. NICE recommends in any patient aged >75 following a fragility fracture (without the need for DEXA scanning)

• The weekly dose regimens (risedronate 35mg, alendronate 70mg once weekly) are easier to remember and to tolerate than daily dosing, but patients should still take daily vitamin D ± calcium

• Use bisphosphonates cautiously when there is dysphagia or a history of dyspepsia. Upper gut ulceration occurs rarely. Risedronate is better tolerated. Must be taken on an empty stomach 30min before food or other medicines. Swallow the tablet whole with a full glass of water while sitting or standing. Remain upright for 30min after swallowing

• Up to 15% of patients are ‘non-responders’ and continue to lose bone mass. Up to 50% will stop taking the medication within 6 months. In the event of treatment failure (a new fracture), consider adherence, bone turnover markers, and changing medication if indicated

• Contraindicated in hypocalcaemia. Manufacturers advise avoiding in CKD (eGFR <35)

• iv zoledronic acid is given once per year for 3 years and may be used for those patients who cannot tolerate oral preparations due to side effects or poor adherence

• Osteonecrosis of the jaw is a very rare, but serious, side effect (↑ risk with cancer, steroid treatment, and poor dental hygiene). Stop the drug and refer to a maxillofacial surgeon

• Denosumab is a monoclonal antibody given s/c 6-monthly. Do not give if hypocalcaemia exists or if eGFR <15

• Less common drugs, usually advised only by specialist teams include: teriparatide, raloxifene, and calcitonin

• Strontium ranelate significantly ↑ the incidence of stroke, MI, and VTE. It is no longer widely used in the older population

• Vertebroplasty can be considered for severe pain after spinal wedge fracture where conservative measures are not effective

Further reading

National Osteoporosis Guideline Group (2014). Osteoporosis: clinical guideline for prevention and treatment.  http://www.shef.ac.uk/NOGG/NOGG_Executive_Summary.pdf.

http://www.shef.ac.uk/NOGG/NOGG_Executive_Summary.pdf.

Polymyalgia rheumatica

PMR is a common inflammatory syndrome causing symmetrical proximal muscle aches and stiffness. It affects only older people (do not diagnose it under age 50). There is usually rapid (days) onset of shoulder, and then thigh, pain that is worse in mornings. Sometimes associated with malaise, weight loss, depression, and fever. Often quite disabling, with little to find on examination.

Pathology

Pathogenetically similar to GCA (TA); the two conditions commonly coexist and may represent a spectrum of disease. Pain in PMR is thought to be due to synovitis and bursitis.

Diagnosis

► A difficult diagnosis to make reliably—a significant number of patients are misdiagnosed. The following should be present for a firm diagnosis:

2. Bilateral aching and morning stiffness (lasting 45min or more). The stiffness should involve at least two of the following three areas: neck or torso, shoulders or proximal regions of the arms, and hips or proximal aspects of the thighs

The following should also be considered:

• Often have anaemia (usually normochromic normocytic), weight loss, and mild abnormalities of the liver (especially ALP)

• Clinical examination often normal—despite the name, muscle tenderness is absent and pain arises because of bursitis/synovitis. Rarely there may be palpable synovitis in peripheral joints (e.g. knee, wrist)

• Muscle enzymes and EMG are normal

• Temporal artery biopsy (TAB) is positive in <25% and is rarely required

• Exclude other causes (e.g. connective tissue disease, tumour, chronic infection, neurological diseases), particularly if a patient does not respond quickly to steroids

Treatment

• Prednisolone 15mg usually produces a reduction in symptoms, with complete resolution in most within 1 week

• Treat until symptom-free for 3 weeks and ESR/CRP normalize, then reduce the dose quickly initially (e.g. 2.5mg/3 weeks), then more slowly below 10mg (1mg/month or slower), checking for relapse of symptoms or blood tests

• If symptoms recur with an associated rise in ESR/CRP, then put the steroid dose up until both settle, then restart tailing more slowly

• Some patients can be taken off steroids after 6–8 months, but most need long-term steroids (median duration 2–3 years)

• Always give bone protection (e.g. alendronic acid 70mg once weekly with calcium and vitamin D). If a treatment trial, wait until diagnosis clear

• Azathioprine or methotrexate may be used as steroid-sparing agents or as adjuvant therapy with specialist guidance

• Educate and involve the patient in monitoring disease

Diagnostic dilemma and steroid ‘dependency’

Some older patients who were diagnosed with PMR years ago no longer exhibit or remember their symptoms, and will be having steroid side effects. They may resist steroid withdrawal or experience symptoms as steroids are ↓ or withdrawn, even if the characteristic syndrome and inflammatory responses are not displayed.

Many other diseases (even simple OA) respond to steroids (although usually less dramatically). Steroid withdrawal itself can cause general aches, which some have called ‘pseudo-rheumatism’.

Avoid this difficult situation by:

• Comprehensive assessment at onset with good record-keeping, so that others can reappraise the diagnosis if response to treatment is poor

• Ensuring that where the diagnosis is not clear, a treatment trial is reviewed early for impact—if the response is not convincing, then stop the steroids. ► Beware continuing steroids because the patient feels ‘a bit better’

• Considering the differential diagnosis carefully

• Discussing diagnosis and treatment with the patient

• Agreeing with the patient a clear plan for reviewing steroid therapy

• Explaining that steroid withdrawal can cause muscle aches, but the blood tests help us distinguish between this and disease reactivation

Giant cell arteritis

GCA, or TA, is a relatively common (18 per 100,000 over age 50) systemic vasculitis of medium to large vessels. Mean age of presentation 70 (does not occur age <50). More common in women and Scandinavia/northern Europe.

Pathogenesis

• Chronic vasculitis, mainly involving cranial branches arising from the aortic arch. Similar pathology seen in PMR, but different distribution

• Possibly an autoimmune mechanism, but no antibodies/antigen isolated

Clinical picture

• Systemic: fever, malaise, anorexia, and weight loss

• Muscles: symmetrical proximal muscle pain and stiffness as in PMR

• Arteritis: tenderness over temporal arteries—not so much a headache as scalp tenderness. Classically unable to wear a hat or brush hair. If an artery occludes, distal ischaemia or infarction occurs

• Severe headache is present in 90% (due to ischaemia or local tenderness of facial or scalp arteries)

• Jaw claudication (occlusion of maxillary artery)

• Amaurosis fugax: blindness due to occlusion of the ciliary artery, which supplies the optic nerve—this causes a pale, swollen optic nerve, but not retinal damage (which is a feature of central retinal artery occlusion with carotid disease)

• Any large artery, including the aorta, can be affected

► Always suspect GCA if amaurosis fugax involves both eyes (atheroma is more commonly unilateral).

Investigations

• CRP also very high and falls faster with treatment than ESR

• May have normochromic normocytic anaemia and renal impairment

• TAB is highly specific, and therefore the gold standard test. Because the vasculitis may be patchy, TAB is not always positive, i.e. the sensitivity is moderate. TAB becomes negative quickly (1–2 weeks) with treatment

• Ultrasound of the cranial arteries is an alternative to diagnosis

• Same-day ophthalmology assessment if visual symptoms

Treatment

• Never delay treatment while waiting for a biopsy

• Prednisolone 40–60mg (higher doses and slower dose reduction are required than for PMR)

• Amaurosis fugax due to GCA is an ophthalmological emergency that can result in permanent visual loss. Give 60–80mg oral prednisolone or high-dose methylprednisolone iv (500mg to 1g daily for 3 days) and aspirin 75mg and gastric protection with a PPI

• Between a third and a half of patients are able to come off steroids by 2 years

• After stopping steroids, continue to monitor as relapse is common

• Osteoporosis prophylaxis should be started at initiation of steroids (usually a bisphosphonate with calcium and vitamin D)

• Azathioprine and methotrexate are sometimes used as steroid-sparing agents once therapy is established. Consider them if:

• Steroid side effects are prominent

• High steroid doses are required

• There is recurrent relapse off treatment

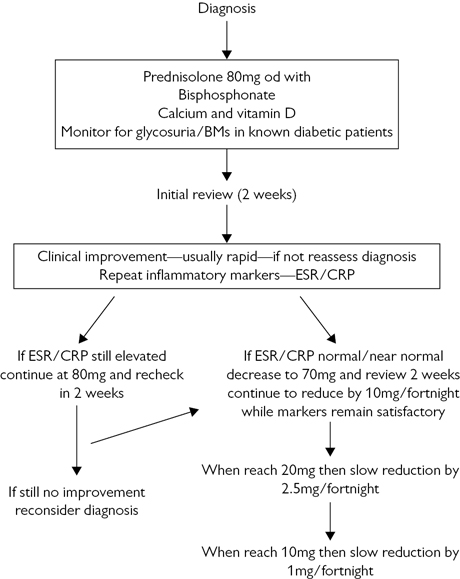

HOW TO . . . Manage steroid therapy in giant cell arteritis

A suggested protocol for steroid treatment in complicated GCA (with visual symptoms or severe jaw claudication) is shown in Fig. 17.1.

Fig. 17.1 A protocol for steroid treatment in giant cell arteritis.

• If rebound of symptoms or inflammatory markers occurs, then take two steps back on the reduction schedule. Wait 4 weeks before reducing again

• Beware a steroid withdrawal syndrome, which can occur without arteritis recurrence. ESR and CRP are normal (see  ‘Diagnostic dilemma and steroid “dependency” ’, p. 475)

‘Diagnostic dilemma and steroid “dependency” ’, p. 475)

• Other blood parameters (anaemia, impaired liver function) may help guide treatment

Muscle symptoms

Muscular symptoms are common in older people and can arise from a range of conditions.

It should be possible to distinguish between the following:

• True muscle weakness due to:

• UMN lesions (e.g. midline brain lesions such as tumours, subdural bleeds, degenerative brain disease, or cord pathology such as discs or vertebral collapse)

• Anterior horn cell lesions (e.g. MND, polio)

• Motor nerve root problems (spinal stenosis, malignant infiltration)

• Peripheral motor nerve problems (inflammatory polyneuritis, thyroid disease, toxins, diabetes)

• Neuromuscular transmission problems (myasthenia gravis, malignancy-related impairments, drug-induced problems)

• Muscle abnormalities (dermatomyositis, inclusion body myositis, drug damage—especially steroids or statins, thyroid disease, vitamin D deficiency, electrolyte or pH imbalances)

• Joint disease with local pain and stiffness, reducing use with resulting weakness (e.g. OA)

• Asthenia—feeling of weakness, low energy and apathy as a result of systemic disease (e.g. cancer, heart disease, and chronic lung disease), confinement to bed, or psychological factors (anxiety, depression). Commonly present as feeling too tired/weak to participate in therapy

History and examination

• Take a full history, including drugs and comorbidities

• Ask about muscle pain (rarely a feature of true myopathy—consider overexertion or fibromyalgia) and cramps

• Look for muscle wasting and abnormal movement (localized wasting indicates a problem with the relevant motor nerve or muscle body; fasciculation may indicate MND)

• Is the weakness generalized (usually due to cachexia or myasthenia gravis) or limited to specific tasks (more common with localized muscle weakness)?

• Grade muscle strength with standardized score (see  ‘HOW TO . . . Grade muscle strength’, p. 481) for later comparisons

‘HOW TO . . . Grade muscle strength’, p. 481) for later comparisons

• A lack of demonstrable muscle weakness, despite symptoms, usually indicates asthenia

• Check for fatigability (may indicate myasthenia gravis)

• Ask about CNS disease and examine neurologically (brisk reflexes with upgoing plantars point to the CNS, whereas absent reflexes may indicate peripheral nerve disease)

• Check the joints for degenerative disease; ask about pain and stiffness

• Look for evidence of systemic disease (e.g. thyroid, malignancy)

Investigations

• Screening bloods should include: potassium (K), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), urea, creatinine, LFTs, TFTs, autoantibody screen, FBC, ESR, CRP, serum electrophoresis, and haematinics. CK is elevated after prolonged lie, seizure, or an im injection, or with pathology of the muscle unit

• Plain X-rays can reveal joint disease

• Ultrasound can be used to assess joints and muscle

• CT or MRI scans can demonstrate CNS pathology, cord problems, and degree of muscle atrophy

• Nerve conduction studies and EMG are useful to demonstrate nerve pathology, problems with neuromuscular transmission, and intrinsic muscle disease. It can confirm the diagnosis in a number of conditions (e.g. chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy)

• Muscle biopsy can sometimes be useful

HOW TO . . . Grade muscle strength

The widely used Medical Research Council grading system allows sequential assessments to be compared. It involves assessing muscle activity in isolation, against gravity, and against resistance, and is scored as follows (see Table 17.1).

Table 17.1 Medical Research Council grading system

| 0 | No muscle contraction |

| 1 | Flicker or trace of muscle contraction |

| 2 | Limb or joint movement possible only with gravity eliminated |

| 3 | Limb or joint movement against gravity, but not resistance |

| 4 | Power ↓ but limb or joint movement possible against resistance |

| 5 | Normal power against resistance |

Scores can be augmented if the category is not quite reached (−) or slightly exceeded (+), e.g. minor reduction in power against resistance may be described as 5−.

Paget’s disease

This is a very common bone disease of old age (up to 10% prevalence, more common in men). It is usually clinically silent—only about 5% are symptomatic.

The cause is unknown. There is abnormal bone remodelling. Most commonly affects the pelvis, femur, spine, skull, and tibia. The resultant bone is expanded and disordered and can cause pain and pathological fracture, and predisposes to osteosarcoma.

Presentation

• Most commonly as asymptomatic elevated ALP

• Often an incidental finding on a pelvis or skull X-ray

• Pathological fracture (especially hip and pelvis)

• Bone pain: constant pain commonly in legs, especially at night. The diseased bone itself can be painful, or deformity can lead to accelerated joint disease at, e.g. the hip, knee, or spine. Fracture or osteosarcoma can cause suddenly ↑ pain

• Deformity: bowing of legs or upper arm is often asymmetrical. The skull can take on a characteristic ‘bossed’ shape due to overgrowth of frontal bones

• Deafness: bone expansion in the skull compresses the eighth cranial nerve, causing conduction deafness, which can be severe

• Other neurological compression syndromes, e.g. spinal cord (paraplegia), optic nerve (blindness), brainstem compression (dysphagia and hydrocephalus)

Investigations

• The bone isoenzyme is more specific and useful when liver function is abnormal

• Rarely (e.g. if only one bone is involved), total ALP can be normal, but the bone isoenzyme is always raised

• Other markers of bone turnover, e.g. urinary hydroxyproline are raised

• X-rays show mixed lysis and sclerosis, disordered bone texture, and expansion (a diagnostic feature)

• Radioisotope bone scans show hot spots

• Immobile patients with very active disease can become hypercalcaemic, although this is rare. If calcium and ALP are raised, there is more likely to be another diagnosis (e.g. carcinomatosis, hyperparathyroidism)

Management

As most cases are asymptomatic, often no treatment is required. Symptomatic cases may warrant referral to a rheumatologist

• Analgesia and joint replacement may be needed

• Fractures often require internal fixation to correct deformity and because they heal poorly

• Bisphosphonates (usually by iv infusion) are very useful. They have several effects:

• Reduce vascularity before elective surgery

• Improve healing after fracture

• Improve neurological compression syndromes

• Reduce serum calcium in hypercalcaemia

• Calcitonin is now rarely used

• ALP, other bone turnover biochemical markers, and occasionally nuclear bone scans can be used to monitor the effectiveness of treatment

Gout

Uric acid crystals deposit in and around joints and intermittently produce inflammation. Serum urate levels correlate poorly with the disease manifestations.

↑ incidence with age due to:

• Worsening renal function and impaired uric acid excretion

• ↑ hyperuricaemic drug use, e.g. thiazides, aspirin, cytotoxics

• Common acute precipitants, e.g. sepsis, surgery

Presentation

• Acute monoarthritis in feet or hands is the most common but can also occur in large joints such as knee or shoulder. The joint is very painful, hot, and red. Patients often refuse to bear weight or move the joint. The patient can look unwell and sometimes has a fever

• Chronic tophi (usually painless) over finger joints and in ears can occur, associated with a chronic arthritis. Sometimes mistaken for other more common arthritides

Investigations

• During an acute attack, serum uric acid may be normal or high

• WBC, ESR, and CRP are usually high or very high

• May be cloudy or frankly purulent on visual inspection

• Microscopy shows many inflammatory cells

• Under polarized light, negatively birefringent uric acid crystals are seen in joint fluid or in phagocytes

• X-rays are usually normal (rarely see small punched-out erosions in fingers in chronic tophaceous cases)

The main aim is to exclude an infective arthritis.

► If in doubt, consider using iv antibiotics until cultures are negative.

Treatment

• Use paracetamol with a short course of NSAIDs with gastric protection

• If you have ruled out infection, local steroid injections are often effective (e.g. methylprednisolone 40mg intra-articular)

• When NSAIDs are contraindicated, use a short course of oral steroids (e.g. prednisolone 30mg od for 5 days)

• Colchicine 0.5mg bd is also effective, but gastrointestinal side effects may limit use

• For chronic arthritis with or without tophi: treat with allopurinol or febuxostat

Prevention

One or two attacks of gout probably do not warrant prophylaxis (especially as such drugs can precipitate further attacks). Instead, try:

• Changing drugs (stop thiazides and aspirin)

• Reduce alcohol (wine is preferable to lager or beer)

• Reduce dietary purines (meat/shellfish)

• Do not leave patients on long-term NSAIDs. Very early use of NSAIDs or colchicine can abort a severe attack of gout

Two or more attacks of gout in one year merit slow introduction of allopurinol (caution in CKD) or febuxostat.

Principles include:

• Start 1–2 weeks after acute inflammation settles

• Consider co-prescription of colchicine or steroids to prevent acute flare

• Dose-titrate to target uric acid level of <300 micromoles/L (associated with reduction in cardiovascular risk)

HOW TO . . . Aspirate/inject the knee joint

Why?

• Aids diagnosis of the swollen joint: infection, crystals, blood

• Useful skill often performed in clinic, DH, or as an inpatient. Hard to do harm

• Allows therapeutic interventions: ↓ pressure and/or injection of medication

• If preceding trauma, obtain X-rays before procedure

• Check clotting and platelets if concerns or on warfarin

Procedure

1. Obtain verbal consent explaining benefits (pain relief, diagnosis, improving mobility) and risks (pain, infection, bleeding, inability to locate joint space)

2. Lay the patient supine with the target knee slightly flexed (a rolled towel under the knee may help with this)

3. Using the parapatellar approach is the simplest; either the lateral or medial aspect of the midpoint of the patella, depending on where most fluid is felt to be

4. Clean and drape using aseptic technique

5. Infiltrate local anaesthetic to subcutaneous tissue if desired

6. Use a 21G (green) needle and 20mL syringe, and briskly insert into the joint, aspirating as you advance. Aim perpendicular to the femur and below the patella. Usual depth 1–2cm

7. Remove as much fluid as possible for relief and samples for analysis. If injecting treatment, keep the needle in place, remove the syringe, and attach a pre-prepared medicine syringe so to avoid repeated skin penetration

Pseudogout

Features

This is an acute, episodic synovitis closely resembling gout, except that:

• Calcium pyrophosphate, rather than uric acid crystals (with positive, rather than negative, birefringence), are found

• Large joints are more commonly affected (especially knees, but also shoulder, hips, wrists, and elbows)

• It is not associated with tophi, bursitis, or stones

• X-rays often show calcification of articular cartilage ‘chondrocalcinosis’ in the affected joint

• It does not respond to allopurinol—so consider this diagnosis where recurrent attacks persist despite allopurinol

As with gout, the patient has an acutely inflamed joint which is very painful to move. They may be systemically unwell with a fever and highly elevated inflammatory markers. Serum calcium is normal.

► Consider this diagnosis in the post-acute patient with a hot, swollen wrist.

Management

Make a confident diagnosis. This usually involves immediate synovial fluid sampling and urgent microscopy to exclude infection and gout.

Effective treatment for acute pseudogout is the same as for acute gout and include:

• Intra-articular steroid injections

• Oral NSAIDs with gastric protection

Long-term preventative treatment is not available.

Contractures

Contractures are joint deformities caused by damaged connective tissue. Where a joint is immobilized (through depressed conscious level, loss of neural input, or local tissue damage), the muscle, ligaments, tendons, and skin can become inelastic and shortened, causing joints to be flexed.

Common causes worldwide include polio, cerebral palsy, and leprosy; in geriatric medicine, common causes include stroke, dementia, and musculoskeletal conditions, e.g. fracture. Contractures are under-recognized—they occur, to some degree, in about a third of nursing home residents and it is still not uncommon to find patients who are bed-bound and permanently curled into the fetal position.

Problems

• Pain: on moving joint but can occur at rest due to muscle spasm

• Hygiene: skin surfaces may oppose (e.g. the hand after stroke or groins in abduction/flexion contractures), making it difficult for carers, and painful for the patient, to keep clean and odourless

• Pressure areas: abnormal posture ↑ risk

• Aesthetics: although the lack of movement causes most disability, the abnormal posture/appearance can be more noticeable

• Function: chronic bed-bound patients may become so flexed that they are unable to sit out in a chair

Prevention

• Where immobilization is short term, e.g. after a fracture, passive stretching followed by exercise regimens should begin promptly

• All health-care staff should understand the importance of maintaining mobility (including sitting out of bed for short periods) and positioning of immobile patients

• Preventative measures are rarely successful at preventing contractures in joints with long-term immobility, e.g. in residual hemiparesis after stroke

• Splinting might help mould the position. Therapists often have expertise in this area

Treatment

• Periodic injection of botulinum toxin is helpful where muscle spasticity is the major problem. There are no real adverse effects, but some patients develop an antibody response after repeated treatment, which renders therapy less effective. Newer preparations are less immunogenic

• There is little point using muscle relaxants, except to help with pain. Even then, drugs such as baclofen, dantrolene, tizanidine, and diazepam usually cause side effects of drowsiness before they reach therapeutic levels. Occasionally assist with PT stretches

• Surgery, e.g. tendon division, has a place in severe cases

• PT can, to some extent, reverse established changes, especially if of relatively recent onset and not severe

Cervical spondylosis and myelopathy

Degeneration in the cervical spine causes neurological dysfunction with both radiculopathy (compression of nerve roots leaving spinal foramina) and myelopathy (cord compression). The resulting mixture of lower (nerve root) and upper (cord) nerve damage causes pain, weakness, and numbness. Progress is usually gradual but can be sudden (especially following trauma). The disease is unusual before the age of 50. Mild forms are very common in the elderly population.

History

• Neck pain and restricted movement may be present but are neither specific nor sensitive markers of nerve damage. Pain may radiate to the shoulder, chest, or arm in a dermatomal distribution (see  Appendix, ‘Dermatomes’, p. 700)

Appendix, ‘Dermatomes’, p. 700)

• Arms and hands become clumsy, especially for fine movements (e.g. doing up buttons). Weakness, numbness, and paraesthesiae can occur

• Leg symptoms usually occur later, with a UMN spastic weakness and a wide-based and/or ataxic gait, often with falls

• Urinary dysfunction is unusual and late

• Rarely can cause vertebrobasilar insufficiency symptoms

Signs

• Arms have predominantly lower motor signs with weakness, muscle wasting, and segmental reflex loss. The classical ‘inverted supinator’ sign is due to a C5/6 lesion where the supinator jerk is lost but the finger jerk (C7) is augmented—when the wrist is tapped, the fingers flex

• Legs may have brisk reflexes, ↑ tone, clonus, and upgoing plantars. In severe cases, a spastic paraparesis with a sensory level can develop

Differential diagnosis

This is wide and includes:

• MND (look for signs above the neck and an absence of sensory symptoms/signs)

• Peripheral neuropathy (no UMN signs)

• Other causes of spastic gait disorders

Investigations

• Plain X-rays in older people almost always show degenerative changes, which correlate poorly with symptoms. They are only useful in excluding other pathology or in demonstrating spinal instability

• MRI scanning is the investigation of choice. Bone and soft tissue structures and the extent of cord compression are all well demonstrated

• CT scanning may be used where there are contraindications for MRI

• Nerve conduction studies can help confirm the clinical impression and exclude other pathology

Management

Cervical collars do not influence progression but can sometimes help with radicular pain and may provide partial protection from acute decline following trauma. The only definitive treatment is surgical—laminectomy with fusion for stabilization.

Surgery is indicated for:

• Progressive neurology (especially if rapidly progressive—consider steroids while surgery is arranged)

• Severe pain unresponsive to conservative measures

• Myelopathy more than radiculopathy

Discuss the risks and benefits with the patient—function is rarely restored once lost, but pain improves and further damage is usually avoided.

Osteomyelitis

Infection of the bone that is most common in the very young and the very old. It is important in geriatric practice because it complicates conditions that frequently occur in older patients, yet presentation is often non-specific and indolent, so the diagnosis may be missed.

Vertebral osteomyelitis

• Usually affects the thoracolumbar spine

• Patients complain of mild backache and malaise and will often have local tenderness. When examining a patient with pyrexia of unknown origin (PUO), always ‘walk’ the examining fingers down the spine, applying pressure to find local bony pain

• Vertebral osteomyelitis (commonly T10–11) may lead to:

• Perivertebral abscess with a risk of cord compression

• Vertebral body collapse with angular kyphosis

• Discitis occurs when the infection involves the intervertebral disc. The patient is relatively less septic, and X-rays appear normal until disease is very advanced (at which point end-plate erosion can occur). Haematogenous spread may occur after surgery or disc space injections

• Haematogenous spread is most common, often after UTI, catheterization, iv cannula insertion, or other instrumentation

• Commonly due to Staphylococcus aureus (consider MRSA), less commonly Gram-negative bacilli, rarely TB

Osteomyelitis of other bones

• Generally more common in children but arise in older patients in some circumstances:

• As a complication of orthopaedic surgery

• As a complication of ulceration (venous or pressure ulcers)

► Always consider osteomyelitis in non-healing ulcers; may be present in as many as 25%.

• In susceptible individuals (e.g. diabetic patients with vascular disease and neuropathy are prone to osteomyelitis in small bones of the feet)

• Organisms include S. aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis (especially with prostheses), Gram-negative bacilli, and anaerobes

Clinical features of osteomyelitis

• Pain is usual but may be missed if there is a pre-existing pressure sore, or the patient has peripheral neuropathy and foot osteomyelitis (e.g. diabetics)

Investigations

• Blood cultures should be taken in all and are positive in around half

• ESR and CRP are usually raised (although very non-specific)

• X-ray changes lag behind clinical changes by about 10 days. Initially normal or showing soft tissue swelling. Later develop classic changes: periosteal reaction, sequestra (islands of necrosis), bone abscesses, and sclerosis of neighbouring bone

• MRI is the investigation of choice, being both sensitive and specific, even in early disease

• Radioisotope bone scanning will show a ‘hot spot’ with osteomyelitis but will not distinguish this from many other conditions (e.g. fracture, arthritis, non-infectious inflammation, metastases, etc.)

• Biopsy or FNA of bone is required to guide antibiotic therapy—this may be done through the base of an ulcer or using radiological guidance (ultrasound is useful here)

• Wound swabs reveal colonizing organisms and are often misleading

Treatment

• General measures such as analgesia and fluids if needed

• Obtaining tissue specimens permits bacterial culture and determination of antimicrobial sensitivity. Duration of therapy is usually long, and identification of the organism allows antibiotic precision to reduce side effects. After specimens are obtained, but prior to results, ‘best guess’ therapy may be started according to local guidelines and with microbiological advice

• Treatment is initially iv, often later converted to oral therapy

• Total treatment duration is usually many weeks or months (depending on sensitivity of organism and extent and location of infection)

• Surgical drainage should be considered after 36h if systemic upset continues or if there is deep pus on imaging

Complications

• Chronic osteomyelitis infection becomes walled off in cavities within the bone, discharging to the surface by a sinus. Symptoms relapse and remit as sinuses close and reopen. Bone is at risk of pathological fracture. Management is long and difficult—this is a miserable complication of joint replacement. Culture organisms and use appropriate antibiotics to limit spread. Surgical removal of infected bone and/or prosthesis is required for cure. Involve specialist bone infection teams, if possible

• Malignant otitis externa occurs when otitis externa spreads to cause osteomyelitis of the skull base. Occurs particularly in frail, older diabetic patients. Caused by Pseudomonas and anaerobes. Facial nerve palsy develops in half, with possible involvement of nerves IX–XII. Requires prolonged antibiotics, specialist ENT input, and possible surgical debridement

The elderly foot

Foot problems are very common (>80% of over 65s) and can cause major disability, including ↑ susceptibility to falls. A particular problem in older people because:

• Multiple degenerative and disease pathologies occur and interact

• Many older people cannot reach their feet—monitoring and basic hygiene (especially nail cutting) may be limited

• Patients think foot problems are a part of ageing or are embarrassed by them and do not seek treatment

• Health professionals often neglect to examine the feet and are too slow to refer for specialist foot care. It is common to find a patient naked under a hospital gown but still with thick socks on

• Inappropriate footwear may be worn—most older people cannot afford or refuse to wear ‘sensible’ shoes such as trainers

• Access to chiropody services is variable on the NHS (rationed to diabetic patients and those with peripheral vascular disease in most areas)

Nails

• Very long nails can curl back and cut into toes

• Nails thicken and become more brittle with age. This is worsened by repeated trauma (e.g. bad footwear), poor circulation, or diabetes. Ultimately, the nail looks like a ram’s horn (onychogryphosis) and cannot be cut with ordinary nail clippers

• Fungal nail infection (onychomycosis) produces a similarly thickened, discoloured nail

• Ingrowing toenails can cause pain and recurring infection

Skin

• Corns (painful calluses over pressure points with a nucleus/core)

• Cracks and ulceration (see  ‘Leg ulcers’, p. 593)

‘Leg ulcers’, p. 593)

Between the toes

Fungal infection (‘athlete’s foot’) is very common. The skin maceration that results is a common cause of cellulitis.

Bone/joint disease

• A bunion (hallux valgus) is an outpointing deformity of the big toe, which can overlap the second toe

• Hammer toes are flexion deformities of proximal interphalangeal (IP) joints

• Claw toes have deformities at both IP joints

• OA or gout of the metatarsophalangeal joint causes pain and rigidity

• Neuropathic foot: long-standing severe sensory loss in a foot (e.g. diabetics, tabes dorsalis), with multiple stress fractures and osteoporosis disrupting the biomechanics of the joints (Charcot’s joint). The foot/ankle is swollen and red, but painless with loss of arches (rockerbottom foot)

Circulation impairment

Common. Assess vasculature (including an ABPI; see  ‘HOW TO . . . Measure ABPI’, p. 307) if there is pain, ulceration, infection, or skin changes.

‘HOW TO . . . Measure ABPI’, p. 307) if there is pain, ulceration, infection, or skin changes.

Sensory impairment

Touch, pain, and joint position sense are all important to maintaining normal feet.

HOW TO . . . Care for the elderly foot

Prevention

• Inspect both feet frequently (at least every other day). A hand mirror assists inspection of the sole. ► If a patient cannot see, reach, or feel their feet, someone else should be helping them regularly

• Examine for swelling, discoloration, ulcers, cuts, calluses, or corns

• If these are identified, consult a health professional (podiatrist, nurse, or doctor) promptly

• Wash feet daily in warm water with mild simple soap. If feet are numb, check that the water temperature is not too hot with a hand or with a thermometer (35–40°C is best)

• After washing, dry feet thoroughly, particularly between the toes

• Change socks or stockings daily

• Dry, hard, or thick skin should be softened with emollients such as liquid and white soft paraffin ointment (‘50:50’)

• Footwear should be supportive but soft. Take particular care with new footwear, inspecting feet frequently after short periods of wear to ensure that no sores have developed

• Cut nails regularly, cutting them straight across and not too short

Treatment

• Qualified podiatrists or chiropodists will debride calluses/corns and use dressings and pressure-relieving pads to prevent them from recurring. Availability on the NHS has been severely restricted recently (only diabetics qualify in most regions), so cost may deter patients

• Treat athlete’s foot (e.g. clotrimazole cream bd for 1 week)

• Distinguish between thick, discolored nails due to onychomycosis from simple onychogryphosis by sending nail scrapings for microscopy for fungal hyphae. Topical antifungal treatment is often not practical, and tablet treatment (e.g. terbinafine) can take months to be effective, so the vast majority of elderly patients remain untreated. If you do decide to use terbinafine, monitor liver function and be wary of drug interactions

• Surgery may be used to remove nails or correct severe bone deformity

The elderly hand

Hand problems are common in older people and may lead to functional problems (finding it hard to perform necessary ADLs), as well as social and cosmetic problems (e.g. unable to wear a wedding ring). Hand function can be assessed by:

• Opening and closing the hand—looking for smooth and full movement

• Assessing ability to make a pincer grip

• Asking the patient to perform fine motor tasks (e.g. doing up a button)

Hand deformity

• Heberden’s nodes (at distal IP joint) and Bouchard’s nodes (at proximal IP joint) are common in older hands and have X-ray appearances of OA. They are rarely painful, but hands may become clumsy or difficult to use

• Mallet finger is a flexion deformity of the distal IP joint, usually after trauma (due to tendon rupture). Splinting acutely can correct the problem

• Trigger finger arises because of digital tendinitis and tenosynovitis (inflammation of tendons and tendon sheaths of the hand, often with fibrosis). More common in people with diabetes. The finger may lock in flexion, suddenly extending with a snap. Treat with rest and splinting, and consider NSAIDs with gastric protection. Steroid injection may help, or surgical release can be done

• Swan-neck deformity occurs classically in rheumatoid arthritis (but also with other tendon problems) and involves hyperextension of the proximal IP joint with flexion of the distal IP joint. Can cause significant disability, and surgery may help

• Boutonnière deformity is flexion of the proximal IP joint and hyperextension of the distal IP joint, due to tendon rupture, dislocation, fracture, OA, and rheumatoid arthritis. Early splinting may help, but surgery is rarely useful

• Dupuytren’s contracture is progressive contracture of the palmar fascial bands, producing flexion deformities of the fingers. Occurs mainly in older men, with diabetes, alcoholism, or epilepsy. Autosomal dominant inheritance (incomplete penetrance). Steroid injection may help early disease; advanced disease requires surgery

Common hand symptoms

• Cold hands are commonly reported in older patients, and indeed hands may feel cold, despite good vascular supply. Reassure, and use simple measures (gloves, warm soaks) to provide relief

• Numb hands should prompt assessment for nerve entrapment or peripheral neuropathy, but symptoms may be present in the absence of these. Patients will describe intermittent pins and needles or just a lowered sense of touch and may be clumsier. Use of warm soaks, analgesia, stretching exercises, and reassurance can be helpful

• Hand cramps can be troublesome, especially at night. Try warm soaks, hand stretches, or calcium supplements to relieve

• Dropping objects in the absence of demonstrable pathology is common and may result from subtle changes in proprioceptive ability

Repetitive strain injury

This is becoming more common in older people, often from excessive use of computers. Treatment is with rest, analgesia, and modification of the precipitating behaviour.

Carpal tunnel syndrome

• More common with age, OA, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, hypothyroidism, obesity, smokers, or those who apply repetitive strain to the wrist

• Hand and wrist pain with paraesthesiae and numbness in the median nerve distribution

• The patient will often wake at night with burning or aching pain, numbness, and tingling; shaking the hand provides relief

• Reduced sensation in the median nerve distribution and weak thumb abduction are common and suggestive

• Check for Tinel’s sign (tingling in the median nerve region, elicited by tapping the palmar surface of the wrist over the median nerve site in the carpal tunnel) or Phalen’s test (flexion of the wrist for 1min)

• Thenar muscle atrophy occurs late

• Older patients will often have multilevel nerve entrapment (cervical as well as at the wrist)

• Treatment is initially with splinting and analgesia. Steroid injections can help; surgery is usually curative. Consider this even in frail patients in whom function (e.g. ability to hold their frame) is impaired

Complex regional pain syndrome

• Also known as reflex sympathetic dystrophy or shoulder hand syndrome

• Occurs in the extremities, characterized by pain, swelling, limited range of motion, vasomotor instability, skin changes, and patchy bone demineralization

• Can occur following an injury, surgery, or a vascular event such as MI or stroke

• Pathophysiology poorly understood

• Think of the diagnosis where there is intense throbbing arm pain with an alteration in skin temperature

• Autonomic testing is abnormal, and bone scans show ↑ uptake early in the disease. X-rays may show osteopenia, and MRI may show skin and tissue changes later in the disease

• Early mobilization after a stroke helps prevent this condition

• Early disease can be treated with smoking cessation, topical counter-irritants (e.g. capsaicin), oral NSAIDs, and steroids. Bisphosphonates help prevent bone loss and provide pain relief

• More advanced disease may respond to regional sympathetic nerve blocks and generally require specialist pain team input

The painful hip

► The important diagnosis not to miss in the frail elderly is fracture.

Having a low threshold of suspicion and for investigation is key.

Hip fracture

• The absence of a recent fall and ability to weight-bear should not put you off obtaining an X-ray

• In any bedbound patient after a fall, look for inability to lift the leg off the bed and pain on movement (especially rotation), even if they are not fit to stand. A shortened externally rotated leg is a useful sign but will occur in many who have replacement hips and is not seen in all

• Some patients can walk on a fractured hip

• Get anteroposterior pelvis and lateral hip X-rays

• Have the X-rays reported by a radiologist—changes can be subtle

• Check for pubic ramus fractures, as well as fractures of the femoral head and shaft

• If initial films are normal but clinical suspicion is high, an MRI should be obtained and is sanctioned in NICE guidance. It is important to make the diagnosis early—do not be afraid to argue your case with radiology

Almost all hip fractures require surgical repair no matter how frail the patient (conservative management with or without traction is painful and has a massive morbidity and mortality). By contrast, low-energy pelvic fractures in older people do not require surgery (see  ‘HOW TO . . . Manage non-operative fractures’, p. 469). Even with surgery, the 30-day mortality for a fractured neck of femur is high (8–9%). Remember to initiate osteoporosis treatment.

‘HOW TO . . . Manage non-operative fractures’, p. 469). Even with surgery, the 30-day mortality for a fractured neck of femur is high (8–9%). Remember to initiate osteoporosis treatment.

Osteoarthritis

• Pain is ‘boring’ and stiffness occurs after rest

• Restriction of movement occurs in all planes

• OA can significantly ↑ chance of falls

• Total hip replacement is now widely available and very effective

• Consider referral for radiographic moderate/severe disease with ongoing pain or disability despite trial of conservative treatment

• There is 1% mortality, but older people often have a good long-term result. Revision surgery is rarely needed because activity levels are lower than in younger people (and life expectancy less)

Other causes of hip pain

• Paget’s disease: also causes 2° OA

• Radicular pain referred from the spine

• Septic arthritis: rare and difficult diagnosis to make, but consider joint aspiration under ultrasound if your patient appears septic with a very painful hip, especially after recent hip surgery

• Vitamin D insufficiency may present with pelvic girdle weakness and pain

• Avascular necrosis of the femoral head (rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, steroids)

The painful back

Assessment

• History should include position, quality, duration, and radiation of pain, as well as associated sensory symptoms, bladder or bowel problems, and a systems review

• Undress the patient and look for bruising and deformity

• Apply pressure to each vertebra in turn, looking for local tenderness

• Look for restriction of movement and gait abnormality

• Always check neurology and consider bowel/bladder function

► ‘Red flags’ for serious pathology include acute onset, leg weakness, fever, weight loss, and bowel and bladder dysfunction (including a new catheter).

Causes

• OA of the facet joints becomes more common than disc pathology with advancing age (discs are less pliable and less likely to herniate)

• Osteoporosis and vertebral crush fractures can cause acute, well-localized pain, chronic pain, or no pain at all

• Spondylolisthesis most commonly affects the lumbar spine and is worse on activity or standing

• Metastatic cancer should always be considered, especially if pain is new or severe, there are constitutional symptoms such as weight loss, or pain from an apparent fracture fails to improve

• Vertebral osteomyelitis and infective discitis should be considered in those with fever and raised inflammatory markers, especially if they are immunosuppressed (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis on steroids)

► Not all back pain comes from the spine. Differential diagnoses that should not be missed include pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer, biliary colic, duodenal ulcer, aortic aneurysm, renal pain, retroperitoneal pathology, PE, Guillain–Barré syndrome, or MI.

Investigations

• FBC, ESR, myeloma screen, CRP, ALP, calcium, PSA (in men)

• MRI is good at identifying serious pathology, e.g. cancer, infection, compression syndromes

• CT can be done if unable to have MRI but has lower diagnostic yield

• Bone scan is sometimes useful if there are multiple sites of pain

• Plain X-rays may reveal diagnosis, but ‘wear and tear’ changes are very common and correlate poorly with pain. May miss serious pathology

Treatment

Firstly, make a diagnosis to guide therapy.

Specific therapies include:

• Bisphosphonates, calcitonin, or vertebroplasty for osteoporotic collapse

• Radiotherapy and/or steroids are very effective for metastatic deposits

• Urgent surgery or radiotherapy should be considered for cord compression, with high-dose iv steroids while awaiting definitive treatment

General therapies for most diagnoses include:

• Standard analgesia ladder (see  ‘Analgesia’, p. 136)

‘Analgesia’, p. 136)

• PT is often helpful in improving pain and function or at least preventing deconditioning

• Exercise and weight loss (if obese) are difficult to achieve but will help

• TENS can help some and is without side effects

• Antispasmodics, e.g. diazepam 2mg, if muscular spasm is prominent

• Consider referral to a pain specialist for local injections, e.g. facet joints or epidurals

• Once serious pathology has been excluded, a chiropractor/osteopath can sometimes help

The painful shoulder

The shoulder joint has little bony articulation (and hence little arthritis), but lots of muscle and tendon which is prone to damage. Many conditions become chronic, and examining elderly people will reveal a high prevalence of pain and restricted movement. Patients compensate (e.g. by avoiding clothes that need to be pulled over the head) and may not report symptoms.

Before diagnosing one of the conditions that follow, exclude systemic problems such as PMR and rheumatoid arthritis. Remember that neck problems, diaphragmatic pathology, apical lung cancer, and angina can also produce shoulder pain.

Frozen shoulder/adhesive capsulitis

• Usually idiopathic but sometimes follow trauma and stroke

• More common in people with diabetes

• Loss of rotation (internal and external) and abduction

• Painful for weeks to months, then stiff (frozen) for further 4–12 months

• Mainstay of treatment is PT/exercise—avoid rest

• Intra-articular steroids may help pain and improve tolerance to early mobilization

Biceps tendonitis

• Pain in specific area (anterior/lateral humeral head) aggravated by supination on the forearm while the elbow held flexed against the body

• Treatment is rest and corticosteroid injection, followed by gentle biceps-stretching exercises

Rotator cuff tendonitis

• Dull ache radiating to the upper arm with ‘painful arc’ (pain between 60° and 120° when abducting the arm)

• Rest, occasionally with immobilization in a sling, and corticosteroid injection

• Arthroscopic decompression can sometimes relieve pain

Rotator cuff tear

• Reduced range of active and passive movements of shoulder

• Ultrasound and MRI diagnostic

• Treat with rest and corticosteroid injection

• Surgical repair possible in some cases

Shoulder dislocation

• May occur after a fall (usually anterior) or seizure (may be posterior)

• Shoulder is painful and appears deformed, and X-rays will confirm

• Check for neurovascular damage; pain relief, and arrange joint reduction by manipulation

Glenohumeral osteoarthritis

• Uncommon site for arthritis—there is usually previous trauma

• Presentation and examination similar to frozen shoulder

• Classic examination findings are of:

• Local glenohumeral joint line tenderness and swelling anteriorly

• Loss of range of motion of external rotation and abduction

• Initial treatment is with analgesia and mobilization

• Joint injection with steroids can be useful

• Failure to respond to conservative measures should prompt consideration of surgical referral for joint replacement—this is highly successful in appropriate patients