Chapter 27

Ethics

Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards

HOW TO . . . Manage a patient insisting on returning home against advice

HOW TO . . . Assess whether an AD is valid and applicable

Diagnosing dying and estimating when treatment is without hope

The process of CPR decision-making

Capacity

• A patient with capacity is intellectually able to make a decision for themselves

• Capacity and competency are equivalent terms, but the UK Mental Capacity Act has ↑ the use of the former

• It is a fundamental human right and a basic ethical principle that individuals can make autonomous decisions. However, society also accepts that some of its members, e.g. children and adults with severe cognitive problems, sometimes do not have the ability to make decisions for themselves, and mechanisms are in place to protect them

• Older people and ill patients (matched for age) are much more likely to lack capacity than the general population and it is important that a geriatrician should be familiar with capacity and its assessment (see Table 27.1)

• Capacity may be impaired by permanent, temporary, or intermittent/fluctuant cognitive impairment or communication difficulties

• Best English practice has now been enshrined in law by the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (Adults with Incapacity Act 2000 in Scotland)

► Always remember that in declaring someone without capacity, you may be robbing them of the ability to be involved in important decisions about their health and lifestyle—however benevolent your motives, such decisions should never be taken lightly or inexpertly.

Table 27.1 Assessing capacity

| Capacity is decision-specific. Questions which are more complex and/or more important demand a higher level of capacity | Assess capacity for each relevant question individually. Global tests, e.g. mental test scores, are not a substitute and can be misleading |

| Capacity is assumed for adults | The burden of responsibility is with the assessor to prove a lack of capacity |

| Capacity levels may fluctuate. Some types of dementia and delirium can cause transient, reversible incompetence | Ensure the patient is functioning at their best before assessing capacity. If in doubt, repeat the assessment later |

| Ignorance is not the same as a lack of capacity | Patients should be educated about a subject before being asked to make a decision (just as you would expect a surgeon to explain an operation before asking you to sign a consent form) |

| A patient with capacity may make an unwise or unconventional decision | Patients with capacity can make decisions which lead to illness, discomfort, danger, or even death. Carers/relatives often need education and support when the patient chooses an unwise option |

HOW TO . . . Assess capacity

• Trigger—doctors should be alert to the possibility of a lack of capacity, but it is often people closer to the patient (relatives/carers) who highlight a problem. In real life, a capacity assessment is usually only employed where there is conflict or where an important step (such as a will or a change in discharge destination) is being considered. Previous assessments of capacity for other decisions, or at other times, are not a substitute for the latest assessment

• Education—the patient should be given ample time to absorb and discuss the facts/advice. Several education sessions may be needed. Maximize your chance of successful communication, e.g. hearing aids. Encourage other health professionals and relatives to discuss the topic with the patient as well

• Assessment—probe the patient to assess retention, understanding, and reasoning. The UK Mental Capacity Act outlines a functional test of capacity. Does the person have the ability to:

• Retain information related to the decision?

• Use or assess the information while considering the decision?

• Communicate the decision by any means?

The patient can fail at any step, most commonly the first.

In borderline or contentious cases, employ a second opinion (often from a psychogeriatrician).

• Action—document the results of the assessment using observations and patient quotes. If the patient lacks capacity, state how the substituted decision will be made, e.g. medical decision in best interests, involvement of carers, case conference, etc.

For examples of documented capacity decisions, see Boxes 27.1, 27.2, and 27.3.

Further reading

The British Medical Association ( http://www.bma.org.uk) and the General Medical Council (

http://www.bma.org.uk) and the General Medical Council ( http://www.gmc-uk.org) provide extensive guidance on consent and capacity.

http://www.gmc-uk.org) provide extensive guidance on consent and capacity.

The UK Mental Capacity Act 2005 gives a legal framework. Available at:  http://www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/acts2005/ukpga_20050009_en_1.

http://www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/acts2005/ukpga_20050009_en_1.

The Mental Capacity Act 2005

Legislation covering England and Wales that provides a framework to empower and protect people who may lack capacity to make some decisions for themselves. Prior to the Act, decisions were often made guided by case law, and although this statutory law has not dramatically affected the way in which geriatricians function, it has clarified who can take decisions, in which situations, and how they should go about this. It also allows people to plan ahead for a time when they may lack capacity by creating a lasting power of attorney (LPA) which is a legally binding advance directive (AD) (see  ‘Advance directives’, pp. 664–665).

‘Advance directives’, pp. 664–665).

The Act covers a range of decisions, from major (e.g. concerning property and affairs, healthcare treatment, and where the person lives) to more minor everyday decisions (e.g. what the person wears), where the person lacks capacity to make those decisions themselves.

There are five key principles in the Act:

• Every adult has the right to make his or her own decisions and must be assumed to have capacity to make them unless it is proved otherwise

• A person must be given all practicable help before anyone treats them as not being able to make their own decisions

• Just because an individual makes what might be seen as an unwise decision, they should not be treated as lacking capacity to make that decision

• Anything done, or any decision made, on behalf of a person who lacks capacity must be done in their best interests

• Anything done for, or on behalf of, a person who lacks capacity should be the least restrictive of their basic rights and freedoms

Independent mental capacity advocates

Provision of independent mental capacity advocates (IMCAs) was a requirement of the UK Mental Capacity Act 2005.

An IMCA should be appointed where the following apply:

• The patient lacks, or has, borderline capacity

• There is no legal proxy, close relative, or other person who is willing or able to support or represent the patient

• There is a major decision to be made (e.g. serious medical treatment or a change of habitation)

The IMCA will have authority to make enquiries about the patient and contribute to the decision by representing the patient’s interests, but cannot make a decision on behalf of the patient.

Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards

The DoLS are described in the Mental Health Act (2007) which updates the UK Mental Capacity Act (2005). They aim to protect people in care homes and hospitals from being inappropriately deprived of their liberty. The safeguards have been put in place to make sure that a care home or hospital only restricts someone’s liberty safely and correctly, and that this is done when there is no other way to take care of that person safely. The safeguards apply to vulnerable adults who lack capacity, but not those who are detained under the Mental Health Act (1983). More recently, the Care Act (2014) includes statutory safeguarding policies and procedures for social care in all settings.

What is deprivation of liberty?

As there is no single legal definition of ‘deprivation of liberty’, it can sometimes be difficult to establish whether it is taking place. Restrictions of a person’s activity can range from minor (e.g. not allowing choice of clothing) to extreme restriction (e.g. refusing to allow a person to see family or friends). Whether the restriction is great enough to amount to a deprivation of liberty will depend on the individual circumstances. Case law is growing in this area.

When should the safeguards be used?

People should be cared for in hospital or a care home in the least restrictive way possible, and those planning care should always consider other options. However, if all alternatives have been explored and the institution believes it is necessary to deprive a person of their liberty in order to care for them safely, then strict processes must be followed. These are the DoLS, designed to ensure that a person’s loss of liberty is lawful and that they are protected.

The safeguards provide the person with a representative, allow a right of challenge to the Court of Protection against the unlawful deprivation of liberty, and require that the decision be reviewed and monitored regularly.

If there is concern that a person is being deprived of liberty, then the institution should be approached and concerns addressed; this is often facilitated by the Adult Safeguarding team. If the institution believes that the restrictions are necessary for safe care of the patient, then a DoLS authorization must be sought via the relevant body (see  ‘Compulsory detention and treatment’, pp. 228–229).

‘Compulsory detention and treatment’, pp. 228–229).

Making financial decisions

Power of attorney (POA)

This is a simple legal document that allows an adult who is competent to nominate another person to conduct financial affairs on their behalf. It is only valid while the person donating the attorney remains competent to do so. It is widely misunderstood by the general public to have wider application than it actually does.

Lasting power of attorney for property and financial affairs

• This was introduced in the Mental Capacity Act (2005) and is often, but not always, combined with a health and welfare LPA (see  ‘Making medical decisions’, p. 660)

‘Making medical decisions’, p. 660)

• It enables nomination of an attorney to make decisions about property and financial affairs—usually trusted family member(s)

• Powers include paying bills, collecting income and benefits, or selling property, subject to any restrictions or conditions that might have been included in the LPA

• It can only be used once it has been registered at the Office of the Public Guardian, but this can be done before the donor lacks capacity, so the attorneys can carry out financial tasks under the supervision of the donor

• A registered LPA can be revoked by the donor if they have capacity

Enduring power of attorney (EPOA)

• Before October 2007, people could grant an EPOA so a trusted person could act for them if they could no longer manage their finances. This has now been replaced by property and affairs LPA (see  ‘Lasting power of attorney for property and financial affairs’, p. 658)

‘Lasting power of attorney for property and financial affairs’, p. 658)

• Any EPOA remains valid whether or not it has been registered at the Court of Protection, provided that both the donor of the power and the attorney/s signed the document prior to 1 October 2007

• An EPOA can be used while the donor has mental capacity, provided they consent to its use

• Once capacity to manage finances is lost, the attorney/s are under a duty to register the EPOA with the Office of the Public Guardian

• An EPOA/POA does not cover anything other than financial decisions

Patients who lack capacity

• An LPA/EPOA cannot be made once the patient is incompetent to understand the principles of the document (although it is not necessary for them to be fully competent to run their financial affairs)

• If an LPA/EPOA is not available for incompetent patients, sometimes the finances can be managed informally, e.g. the pension can be paid out and joint bank accounts can continue

• To formally take over financial management in these circumstances (especially for large estates or where conflict exists), an application to the Court of Protection must be made

• Since the Mental Capacity Act 2005, this court can appoint deputies to manage financial, health, and welfare decisions

Testamentary capacity

This refers to the specific capacity to make a will. Solicitors and financial advisors can help draw up a will and occasionally request a doctor’s opinion about competence. Legal guidelines are well established (see  ‘Making a will’, p. 678).

‘Making a will’, p. 678).

Signing an LPA

Patients should generally avoid making an LPA while unwell or in hospital, as this would make it harder to prove that the patient had capacity if the validity of the document was ever challenged.

Before an LPA is valid, there must be a certificate of capacity drawn up by an independent third party called a Certificate Provider. The Certificate Provider could be a solicitor, a doctor, or another independent person whom the donor has known personally for at least 2 years. In some cases (e.g. after a stroke), it may be most appropriate to ask a doctor to carry out the assessment.

If a capacity assessment is required, check that the patient understands that once registered, the LPA allows the attorney complete financial control; this power extends into the future and they will be unable to revoke the power if they lack capacity. Document carefully, as shown in Box 27.1.

The signing of an LPA must also be witnessed by an independent person (often a friend or in hospital by an administrator or manager). This should not be confused with the role of a Certificate Provider.

Box 27.1 Assessment of capacity to complete an LPA

I interviewed Mrs Jones today. She indicated she wished to make an LPA in the favour of her husband and did not appear to be under duress from another person. She explained her health was deteriorating and she wanted her husband to manage the ‘bills and things’ if she did not feel up to it in the future. She was able to tell me that she owned a current account, a savings account, some premium bonds, and that the mortgage had been paid off on their house. She understood that an LPA would allow her husband to do as he wished with her money, without necessarily consulting her, both now and in the future. She knew that this power would continue even if she was too ill to be consulted. She confirmed that ‘he has always sorted that sort of thing out and I don’t want him to be stopped from doing it because I can’t sign my cheques—I trust him to do the right thing’.

I believe Mrs Jones has capacity to give lasting power of attorney to her husband.

Dated _____________________

Signed ______________________

Making medical decisions

Lasting power of attorney for health and welfare

• This was introduced in the Mental Capacity Act (2005)

• It enables nomination of an attorney to make decisions about personal welfare—usually trusted family member(s)

• A personal welfare LPA can only be used once the form is registered at the Office of the Public Guardian and the patient has become mentally incapable of making decisions about their own welfare

• It can include the power for the attorney to give or refuse consent to medical treatment if this power has been expressly given in the LPA (a proxy medical decision-maker)

• Also includes power to make some social decisions, e.g. where the donor lives

Patients who clearly lack capacity

• Unless a valid LPA is available in the UK, no one can make a decision about medical treatment for another adult without capacity

• It is always worth enquiring if an LPA is completed or if there is a written or verbal AD made by the patient prior to them becoming incompetent (see  ‘Advance directives’, pp. 664–665)

‘Advance directives’, pp. 664–665)

• Doctors are required by the Mental Capacity Act to make decisions in the ‘best interests’ of their incompetent patients, and this holds true even if there is a valid LPA

• In America, a hierarchy of next of kin can legally make substitute decisions. Relatives are often surprised, and occasionally angry, to find that they have few rights in the UK

• In practice, doctors should routinely consult the next of kin where important or contentious medical decisions are made for patients without capacity. The human rights legislation, through its support of ‘family life’ as a basic human right, will reinforce the social shift towards increasing power for relatives. Relatives can help doctors to decide what the patient might have wanted under the circumstances, assisting decisions about best interest

• If there is conflict between the medical team and relatives about what is in the best interests of the patient that cannot be resolved, the doctor involved may wish to seek a second medical opinion, consult with the hospital legal team, an IMCA, or refer to the courts

Patients who may or may not have capacity

• Patients’ views should always be sought about medical treatments

• Often these views will concur with those of the medical professional, or they are happy to be guided by the doctor

• Rarely, a patient will express a view at odds with either the medical team or their family, in which case a careful assessment of capacity to make their own decision is required

• Assess capacity in line with the principles outlined previously, and document meticulously in the notes (see example in Box 27.2)

see  ‘Making complex decisions’, p. 667.

‘Making complex decisions’, p. 667.

Box 27.2 Assessment of patient refusing a colectomy for cancer

Miss Joseph has told me she will not consent to a colectomy. I have explained the procedure that is being recommended, including the benefits and risks, and she has been able to remember and understand this information without difficulty. She explains that in view of her age and lack of current symptoms, she would rather not put herself through a major operation. She said ‘I am 79 years old and I don’t want to be mucked around’. She understands that by refusing surgery she might be shortening her life and that she may become ill in the future as the tumour grows but feels that this is a ‘lesser evil’ than an operation at the moment. I believe she has capacity to make this decision and we have agreed to discuss it again in 2 weeks’ time during an outpatient appointment after she has spoken to her family.

Dated ______________________

Signed ______________________

Making social decisions

The legal position for social decisions for patients without capacity (e.g. where a patient should live) is the same as for medical decisions. Unless an LPA is in place, the healthcare team should consult with the family to try to ensure that the patient’s best interests are met.

If making a decision against the expressed wishes of a patient without capacity, involve an advocate. Where there are no family members, or there is a lack of support for the patient, an IMCA may be appropriate (see  ‘The Mental Capacity Act 2005’, p. 656). The DoLS should be followed (see

‘The Mental Capacity Act 2005’, p. 656). The DoLS should be followed (see  ‘Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards’, p. 657) and these demand that decisions are made ‘the least restrictive’.

‘Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards’, p. 657) and these demand that decisions are made ‘the least restrictive’.

It may be necessary to apply to the Court of Protection for a court-appointed deputy to supervise welfare decisions.

A very common challenge for the geriatric MDT is the patient who wants to continue to live alone in their own home after they have developed physical or cognitive problems which means they are at risk in that environment (see  ‘HOW TO . . . Manage a patient insisting on returning home against advice’, p. 662).

‘HOW TO . . . Manage a patient insisting on returning home against advice’, p. 662).

HOW TO . . . Manage a patient insisting on returning home against advice

First assess whether the patient has capacity to make the decision:

• Patients with capacity should accept that they are at risk and reason that they prefer to take this risk than accept other accommodation

• In borderline or contentious cases, a second opinion, often from a psychogeriatrician, can be helpful

If the patient has capacity, then they cannot be forced to abandon their home or accept outside help, although the healthcare team and family can continue to negotiate and persuade.

• It is worth determining what motives lie behind the patient’s insistence; sometimes misconceptions can be corrected

• Patients will sometimes agree to a trial period of residential care or care package, and this often leads to long-term agreement

Where the patient lacks capacity, decisions should be made in the patient’s best interest and be the least restrictive option. While the patient should not be discharged to an environment where they will be at unreasonable risk, the team should still attempt to accommodate the patient’s wishes and steps may be taken to reduce risk (e.g. disconnecting or removing dangerous items, alarm systems, or regular carer visits, etc. may still allow a patient to return home). There is no such thing as a ‘safe’ discharge—only a safer one.

Finally record your capacity assessment clearly as per the following example.

Box 27.3 Assessment of patient insisting on returning home against advice

Mr King has been a patient of mine for 2 years. He has a progressive dementia which is now severe, and concern has been expressed by his son and the carers that he is at risk to himself in continuing to live alone at home. He was admitted to hospital on this occasion after a small house fire (he left an unattended pan on the stove). He has had three other admissions since Christmas with falls and accidents. Over the last 2 weeks, I have had several discussions with him about why his family is concerned about him. The nurses, his son, and his home carers have also had such discussions. When I spoke to him today, he was disoriented in person and place (believing he was in a police station and that I was a policeman). He expressed a wish to go home to be with his wife (who died 12 years ago) but could not tell me his address. He did not believe that there were any risks involved in going home and did not accept that there was a possibility of falling over again, saying ‘I am a very strong man, you would be more likely to fall over than me.’ When I discussed the fire, he started talking about his war-time experiences and would not accept that there was a risk of fires in the future. At present I believe that Mr King lacks capacity to make a valid decision about his social circumstances. I have no reason to believe that his level of competency will improve with further education or time. A multidisciplinary best interests meeting has been arranged for next week to discuss if it is practical to continue to support him in his own home or whether placement should be sought.

Dated ____________________

Signed ____________________

Advance directives

• An AD (also known as advance decision) is a patient-led medical decision, made when the patient is competent, which is designed to come into force if a patient becomes incompetent

• ADs were developed to promote personal autonomy

• They may be verbal statements but are more commonly written (sometimes known as a living will)

• ADs are usually employed by patients to refuse aggressive treatment but could, theoretically, be used to request or direct treatment. However, ADs cannot be used to request treatment which would not usually be offered or to withdraw ‘basic care’ (e.g. nursing or analgesia)

• A valid AD holds the same weight in law as a contemporaneous patient decision, and doctors who provide a rejected treatment could be sued for battery. However, a doctor must first assess whether an AD is valid and applicable (see  ‘HOW TO . . . Assess whether an AD is valid and applicable’, p. 665)

‘HOW TO . . . Assess whether an AD is valid and applicable’, p. 665)

• A template AD can be downloaded from the Compassion in Dying charity website ( http://www.compassionindying.org.uk)

http://www.compassionindying.org.uk)

The UK Mental Capacity Act clarifies the legality of ADs. In an emergency, if an AD is not provided, or if there is doubt about the legitimacy of an AD, then clinically appropriate treatment should be provided. Where a healthcare professional has a conscientious objection to implementing a valid AD, the care should be handed to another practitioner. Despite the theoretical advantages of ADs for patients, relatives, and the medical team, they are still rarely seen in clinical medicine. There are several barriers to their successful implementation:

• Patients are often unaware of ADs or their legal validity

• Patients and doctors are often reluctant to confront these distressing topics or feel that the other party should initiate discussions

• The transfer of AD from 1° care, family homes, and solicitors (where they are often composed and lodged) to hospital (where they are most commonly designed to be implemented) is often poor

• Concern that views might change in future altered states of health

• ADs may be too vague to inform physicians, e.g. a refusal of ‘life-sustaining treatment’ may not help with decisions about iv fluids

• A high level of competence is required to complete an AD. Patients with conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease have commonly lost the ability to make one by the time of diagnosis

Ideally an AD forms part of the wider process of advance care planning between a patient and healthcare professionals, being promoted by the UK Gold Standards Framework ( http://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk/advance-care-planning).

http://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk/advance-care-planning).

ADs are most likely to be useful when there is a predictable course of illness (disease-specific ADs have been used in AIDS, cancer, MND, and COPD).

HOW TO . . . Assess whether an AD is valid and applicable

If a patient retains capacity, then you should discuss management decisions with them in the usual way. An AD is not an excuse for avoiding, often emotionally difficult, discussions with patients or relatives. Contemporaneous decisions always outweigh a previous AD.

As long as an AD is valid and applicable, it should usually guide treatment. This was true under common law before the Mental Capacity Act, but the conditions of validity and applicability are now more clearly defined.

Validity

• Verbal statements are theoretically valid, but it is much harder to ensure that they are correctly relayed and refusal of life-sustaining treatment must be written

• Ensure that the AD was not given under duress or pressure from a third party

• It is necessary to assess if the patient had capacity at the time the AD was created (both capacity to make an AD and capacity in terms of understanding the pros and cons of the medical treatment they are refusing), and this can be very difficult to assess

Applicability

• If the AD is applicable, then the circumstances should be the same as those defined in the AD, e.g. ‘if I had a stroke, I don’t want to be tube-fed’ may not legally constrain management in other situations

The Mental Capacity Act now defines when an AD is legally enforceable. The following conditions must be met:

• The AD must be valid and applicable

• Written statements must be signed and dated

• Must have at least one signature from a witness who is not a relative, an LPA, or a beneficiary of the will

• If the AD refuses life-sustaining treatment, there must also be a statement to verify that the decision applies to treatment ‘even if life is at risk’

• If a health and welfare attorney has been appointed under an LPA, this attorney should also be involved in discussions about the person’s treatment, and doctors should take information provided by him or her into account.

Further reading

British Medical Association (2017). Advance decisions and proxy decision-making in medical treatment and research.  https://www.bma.org.uk/advice/employment/ethics/mental-capacity/advance-decisions-and-proxy-decision-making-in-medical-treatment-and-research.

https://www.bma.org.uk/advice/employment/ethics/mental-capacity/advance-decisions-and-proxy-decision-making-in-medical-treatment-and-research.

General Medical Council (2010). Treatment and care towards the end of life: decision making.  http://www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/ethical_guidance/end_of_life_care.asp.

http://www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/ethical_guidance/end_of_life_care.asp.

Diagnosing dying and estimating when treatment is without hope

A high percentage of elderly patients admitted to hospital are destined to die despite best medical care. A great deal of financial and human resources, and most importantly patient suffering, could be avoided if this death was predictable. The art of applying treatment aggressively when appropriate but backing off compassionately in other circumstances is one of the most common and challenging tasks in geriatric medicine.

There has been a lot of discussion about DNACPR orders, but decisions about less dramatic lifesaving technologies are just as hard (e.g. whether to admit a patient from a nursing home for iv antibiotics and fluids or selecting patients for renal replacement therapy; see  ‘Renal replacement therapy: dialysis’, pp. 394–395) or when to initiate artificial nutrition (see

‘Renal replacement therapy: dialysis’, pp. 394–395) or when to initiate artificial nutrition (see  ‘The ethics of clinically assisted feeding’, pp. 358–359).

‘The ethics of clinically assisted feeding’, pp. 358–359).

Unfortunately, predicting futile treatment is fraught with difficulty—experienced doctors never underestimate the power of some older people to make a miraculous recovery. The following tips may help:

• Attempt to make a diagnosis (which usually requires some investigations and minor procedures) before estimating the prognosis

• Consider a trial of treatment, but constantly monitor the clinical response and be willing to up- or downregulate how aggressively to treat (e.g. a 2-week trial of NG feeding)

• Sometimes it is helpful to define a ‘ceiling of care’ at the onset of treatment (e.g. oral, but not iv, therapy, a 20 unit maximum transfusion for acute gastrointestinal bleeding)

• Decide about each intervention separately—every procedure and patient will have different risk/benefit and tolerability ratios

• If there is doubt or disagreement about the appropriateness of treatment, seek a second medical opinion

• Remember that medical decisions are not made in isolation—relatives, nurses, therapists, and community carers are ultimately affected by such decisions, and open dialogue will help everyone

The patients’ wishes are paramount, but many severely ill patients do not have capacity to make decisions. Beware patients who reject treatment out of ignorance, misconceptions, or fear. Likewise patients or relatives who continue to demand treatment which is clearly not effective (or inappropriate) require education and support.

Deciding that treatment is futile is not the same as ‘giving up’—a positive decision for end-of-life care allows a change in the therapeutic goal from ‘cure’ to ‘keeping comfortable’ and ensuring a dignified death. While in some branches of medicine, this shift can involve a change in environment (e.g. to hospice) and medical team (to community or palliative care team), in geriatric medicine, the line is often blurred (see  ‘Palliative care’, pp. 642–643).

‘Palliative care’, pp. 642–643).

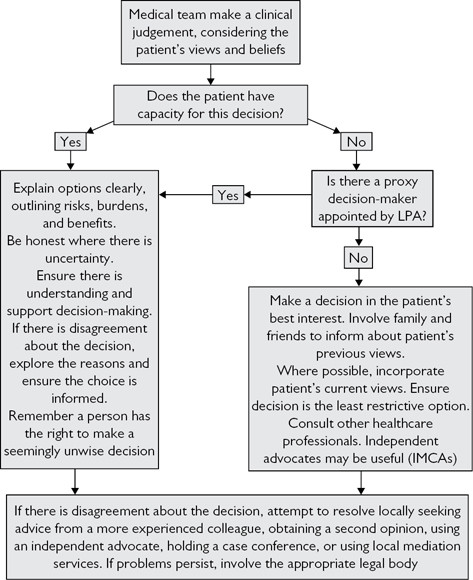

Making complex decisions

All complex decisions should be made with the following in mind:

• The patient should be presumed to have capacity unless proven otherwise and, as such, should be at the centre of the process

• Efforts should be made to optimize decision-making capacity

• All decisions should be in the patient’s best interests

• Wide communication avoids misunderstanding at a later date

Use the flow chart in Fig. 27.1 as a guide.

Fig. 27.1 Flow chart for making complex decisions.

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) was first described in 1967 and is now widely applied both in and out of hospital. Around 20% of those who die in hospital in the UK will have at least one attempt at CPR during their terminal admission. Although the principles of CPR decisions are the same as for other medical decisions, they demand special attention because:

• Cardiac arrest often occurs unpredictably

• Withholding CPR in a cardiac arrest will lead to death

• There is an assumption that all patients will receive CPR in hospital—unlike most treatments, a decision is required to withhold it

• CPR is a highly emotive subject

CPR is undoubtedly a lifesaving procedure (in hospital, around 20% will recover a pulse, and half of these patients will survive to leave hospital). Those who survive CPR have a reasonable life expectancy, but a small percentage (1–2%) will be left with permanent hypoxic brain damage.

Predicting outcome for CPR

(See Table 27.2.)

• Highest success rates are obtained treating arrests due to cardiac arrhythmia on coronary care units, lowest on general medical wards in frail patients with multiple pathologies

• Older patients have lower survival rates, but this is probably a feature of their multiple pathologies, and a good outcome is possible if older patients are carefully selected

• Individual pre-arrest factors are not sensitive or specific enough to be useful in predicting outcome. Morbidity scores combine several variables to attempt to predict outcome of CPR more accurately but are not in common use

Table 27.2 Factors that predict outcome after CPR

| Worse survival rate | Better survival rate | |

| Pre-arrest | MI | |

| Peri-arrest | ||

| Post-arrest |

Further reading

Gold Standards Framework.  http://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk/.

http://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk/.

The process of CPR decision-making

In some circumstances, it is appropriate to decide against doing CPR in the event of a cardiopulmonary arrest. These decisions are known as do not attempt CPR, or do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation (DNACPR), or allow natural death (AND) decisions.

There has been much discussion about the best way of approaching this, with sometimes conflicting views from those in favour of patient autonomy and those who feel this is a medical decision, with many guidelines published. The UK General Medical Council guidance ‘Treatment and care towards the end of life: decision making’ offers a sensible balance ( http://www.gmc-uk.org).

http://www.gmc-uk.org).

When to consider a DNACPR order

• Where attempting CPR will not restart the patient’s heart and breathing (medical futility)

• Where there is no benefit in restarting the patient’s heart and breathing (quality or length of life)

• Where the expected benefit is outweighed by the burdens of CPR

• Where a patient with capacity has decided this is what they want

It may be reasonable to only make decisions for those patients in whom arrest seems likely (e.g. critically unwell, actively dying), although facilities with limited out-of-hours cover may make more prospective decisions. Where no DNACPR decision is made, the presumption is that resuscitation should be attempted.

Where CPR is clearly futile

• A doctor cannot be compelled to provide a futile treatment, and so this is a largely medical decision, although remember that ‘futility’ is rarely clear-cut

• Following the Tracey case (2014), it is clear that doctors have a legal duty to inform patients or their relatives (for a patient lacking capacity) using unambiguous language that this decision has been made. It is only appropriate to withhold this information from a competent patient where it is considered that it would harm them to have such a discussion

Where CPR may be successful

• If CPR may be successful, but outcome may be poor (e.g. quality of life), then a decision made in the best interests of the patient should involve their personal view of that outcome

• For patients with capacity, a careful discussion should be had, outlining the risks, burdens, and benefits of CPR (see  ’HOW TO . . . Manage DNACPR decisions’, p. 671)

’HOW TO . . . Manage DNACPR decisions’, p. 671)

• For those who lack capacity, their views should be approximated from family and friends. Other healthcare professionals should be consulted and an independent advocate (IMCA) may occasionally be useful

HOW TO . . . Manage DNACPR decisions

Ensure you know the local guidelines. Hospitals vary in how this decision is made and recorded, and who is authorized to make DNACPR. Busy physicians need to make time for DNACPR decisions, although they often prove to be easier than anticipated:

• Although it could take 30min to get an elderly patient to make a fully informed decision (many have not even heard of CPR), you can often get a fairly accurate idea from a competent patient with a few quick questions like ‘Have you ever considered your views about resuscitation?’

• Never ignore patient cues, e.g. ‘I don’t suppose I will come out of this?’ or ‘I’ve had my time’. These are ideal times to discuss end-of-life issues and such patients are often relieved by this

• Experienced nurses will often provide helpful guidance

In reality, the majority of DNACPR decisions on geriatric wards will not involve the patient (because of incapacity), so a meeting with relatives may ensue to establish best interest:

• When sensitively handled, there is rarely conflict and many are relieved to be consulted or happy to be guided by the doctor

• Try to use the time to discuss general management (emphasizing positive management steps first—even if that is just maintaining dignity and comfort), so that the family does not perceive the only medical priority is avoiding CPR

• Where conflict does arise, it can be best to leave the patient for CPR and re-address the question later. Relatives often take some time to trust the doctors, to come to terms, or to consult other family/friends, and often the conflict melts away. Remember, CPR is only a small fraction of the patient’s care and it may distract from other more important things. While this might lead to a rise in unsuccessful CPR attempts (with consequent reduction in morale of resuscitation teams and resource implications), it does protect patient autonomy and doctors from complaints/litigation

• No one can be forced to provide a treatment which they feel is inappropriate, so if there is conscientious objection to providing CPR, consider moving the patient to a different doctor/ward

Recording a DNACPR decision

• Write the decision prominently in the medical notes

• Many institutions have a specific form to record these decisions, but ensure that any relevant discussion is fully documented

• Sign, date, and time clearly

• Document the rationale for the decision and the names of those consulted in making the decision

• If the patient/relatives were not consulted, document the reason

• The responsible consultant should endorse a DNACPR order made by a junior doctor as soon as possible

• Ensure the duration of the decision is clear and if ongoing at time of discharge that it is communicated into the community

► Ensure that nurses are aware as soon as a DNACPR order is made.

Rationing and ageism

Rationing

• This has been present in the NHS since its inception in 1948, but the ever increasing cost of modern specialized, technological, and pharmacological medicine, along with the growing sophistication of patients, has meant that recently rationing has become more explicit and contentious

• No UK government has ever openly admitted to rationing, although ‘efficiency saving’ and ‘commissioning’ are thinly disguised ways of handling difficult rationing decisions

• The level at which rationing decisions are made has gradually moved up from physicians themselves (which led to considerable inequality) to hospital managers (which did not remove regional inequality). The introduction of NICE in 1999 was designed to help make rationing decisions at a national level by setting guidelines

• Some initial NICE recommendations that treatments should not be funded (e.g. interferon beta in multiple sclerosis) led to significant lobbying and the development of risk-sharing schemes (allowing government and drug manufacturers to share the cost in certain cases)

• In other cases, funding has been advised, but this has not led to widespread implementation

• So-called ‘postcode prescribing’ refers to the variable availability of drugs, depending on locality-based clinical commissioning groups

Ageism

This is rationing applied by age criteria. Although the 2001 UK National Service Framework has banned explicit rationing (standard 1 states ‘NHS services will be provided, regardless of age, on the basis of clinical need alone’), it is still widespread.

It is accepted that some medical interventions, e.g. ITU, may be less effective when applied to older people, but remember:

• Some older people are physiologically younger (i.e. chronological age does not correlate well with biological age)

• Some treatments (e.g. thrombolysis in MI) save more lives in an older age group (number needed to treat is lower because untreated death rate is higher than in younger groups)

Disability and dependence costs the state dearly. Preventing strokes, operating on severely osteoarthritic hips, etc. are often highly cost-efficient interventions if they enable patients to stay at home, rather than go into costly institutional care. There is good evidence that the average patient uses the majority of healthcare resources in the last year of their life, but it is rarely possible to predict prospectively when patients are entering their terminal year, nor is there evidence that voluntary restriction of medical treatment by ADs (see  ‘Advance directives’, pp. 664–665) has any cost-cutting effect.

‘Advance directives’, pp. 664–665) has any cost-cutting effect.

There is a more fundamental ideological principle that sectors of the population who are perceived to have less social worth are less likely to complain and are largely politically inactive, and should not be discriminated against—whether those sectors are defined by age, sex, or race. The commonly quoted ‘fair innings’ argument suggests that after a certain age, you have had your ‘share’ of world resources and younger patients should therefore take precedence. Older people commonly hold to this philosophy. This method of rationing assumes that everyone uses equal resources and enjoys equal quality of life up until the point that it ‘runs out’. The logical consequence is that high users of resources (e.g. people with diabetes) should have had their fair innings at a much younger age. In reality, society accepts that some of its members will take more than they give to the system—it is prejudice that allows us to accept rationing for older patients, but not for a child with cerebral palsy.

Further reading

Grimley Evans J. The rationing debate: Rationing health care by age: the case against. BMJ 1997; 314: 822.

Williams A. The rationing debate: Rationing health care by age: the case for. BMJ 1997; 314: 820.

Elder abuse

Defined as any act, or lack of action, that causes harm or distress to an older person. Under-recognized, with few prevalence studies. One estimated around 5% of community-dwelling older people have suffered verbal abuse, and 2% physical abuse. Probably more prevalent within care homes, but precise extent unknown.

Types of abuse

Psychological

• Bullying, shouting, swearing, blaming, etc.

• Look for signs of fear, helplessness, emotional lability, ambivalence towards caregiver, withdrawal, etc.

Physical

• Hitting, slapping, pushing, restraining, etc.

• May also include inappropriate sedation with medication

• Look for injuries that are unexplained, especially if they are different ages, evidence of restraint, excess sedation, broken glasses, etc.

Financial

• Inappropriate use of an older person’s financial assets

• Includes using cheques, withdrawing money from an account, transferring assets, taking jewellery or other valuables, failing to pay bills, altering wills, etc.

Sexual

• Forcing an older person to participate in a sexual act against their will

• Look for genital bruising or bleeding, or sexual disinhibition

Neglect

• Deprivation of food, heat, clothing, and basic care

• Occurs in situations where an older person is dependent

• Look for malnutrition, poor personal hygiene, and poor skin condition

• Easier to spot in situations where a certain standard of care is anticipated (e.g. patients from care homes being admitted to hospital who are unkempt, dirty, or inappropriately dressed may raise concerns)

Who abuses?

• Commonly someone in a caregiver role

• Often arises because of carer anger, frustration, and lack of support, training, or facilities, along with social isolation

• Relationship difficulties between carer and recipient, and carer mental illness or substance misuse (e.g. alcohol) exacerbates the situation

• Sleep deprivation or dealing with faecal incontinence may also precipitate abuse

► Most are under extreme stress (‘at the end of my tether’) and extremely remorseful afterwards.

HOW TO . . . Manage suspected elder abuse

The UK Government’s Care Act (2014) guidance provides a structure for local safeguarding policies and procedures. The term ‘safeguarding’ means a range of activities aimed at upholding an individual’s fundamental right to be safe.

If abuse is suspected, then early referral to the local social services adult safeguarding team will trigger and coordinate a multi-agency investigation.

Key features include:

• Involvement of all agencies involved in the patient’s care (GP, home carers, etc.)

• Investigation will be detailed and individually tailored

• As abuse is usually as a result of caregiver stress, a common approach is to attempt to relieve that stress (e.g. providing home care, day care, respite care, health support, advice about sleep or continence, financial help, rehousing, etc.), while maintaining the patient at home

• Close multidisciplinary supervision is essential until the situation improves

• Removal of the patient from an abusive situation may occasionally be done using laws designed primarily for other purposes, e.g. the Mental Health Act (provision to act in the best interests of patients with mental illness)

• Police involvement may occasionally be necessary where there are no remediable factors or a very high risk for future harm

• Further information is available from the following UK charities:

• Action on Elder Abuse,  http://www.elderabuse.org.uk

http://www.elderabuse.org.uk

• Age Concern,  http://www.ageuk.org.uk

http://www.ageuk.org.uk