Chapter 9

WHY SELF-HELP WON’T SAVE US

I’m a sucker for a good motivational talk. I devour self-help books, have attended myriad “change your life” seminars, and subscribe to the email lists of many a personal growth guru. Many times I’ve fallen for the seduction of hope, the fantasy that this new practice or that radical idea will change my life, be it a diet, positive thinking, exercise, or a meditation technique.

I can’t say they haven’t given me my share of aha moments. But substantive lasting effect? Not so much, unless you count the lasting effect of blaming myself when the benefits of a new mindset waned or my enthusiasm for it diminished.

While it is true that my life has improved through adjustments of heart and mind, those changes resulted from more than my individual efforts alone. My individual efforts had to be supported by my environment to be effective. When I was being targeted for abuse at my job, no amount of affirmations or meditation practice could have helped me significantly if not bolstered by union action. I had the resources of a unionized workplace, with labor union staff and stewards to support me. Reinforcement like this is a great boon. If you are well resourced, you’re going to do better, plain and simple, regardless of your grit or determination or other personal characteristics. Completely on our own, we may not have what it takes to get the life we want. Techniques like creating a budget and sticking to it can be helpful, but only if there’s money in that budget.

This isn’t to say that we should give up tugging on our own bootstraps or reaching for that next ladder rung. Rather, I’m pointing out how much easier it is to achieve when you have support networks. Our success depends more on our ability to leverage support and change our environment than it does on changing ourselves. Self-help methods that focus on the individual don’t help much if they fail to account for the surrounding environment. If we discount the importance of environment, we end up blaming the individual for failing to succeed or to “be resilient.” That’s wrong. We need to update our definition of resilience to include its relational context. We need each other.

With the right mix of external resources, almost anyone can cope with most kinds of adversity. Those with supportive friends, savings accounts, a working spouse, and a retirement fund will be better able to roll with a layoff, for instance. Maybe they can even put resources into starting a new business, winding up in a better position than before. Unfortunately, optimistic scenarios like that make no sense for people without the same supports. If you’re living paycheck to paycheck, getting laid off is a threat that could easily overwhelm your ability to manage.

Much research supports this notion of “differential impact,” the theory that altering the environment changes individuals and that these changes depend in large part on the resources provided by the environment as opposed to individual motivation.1 In the study cited in the previous chapter about the Romanian orphans, it was found that when these children were adopted by well-resourced families in Britain, years of delayed neurological and physical development were partially reversed.2 Children who received greater opportunities for emotional attachment—with caregivers and with professionals like physical therapists and speech-language pathologists—showed greater developmental gains. An example like this challenges the notion that individual change relies on personal agency. Differences in access to resources is too often overlooked when we try to explain why people fail or succeed.

As another example, if you are relatively advantaged and your mom dies, you likely have a certain reservoir of resilience to draw on and a set of social circumstances that afford you some advantages. Maybe your employer will give you time off to take care of yourself. Perhaps you have money to cover burial costs and pay for supportive therapy. If you are less advantaged and your mom dies, the negative health impact instead may be magnified: perhaps funeral costs stress your already strained budget; perhaps she provided the free child care you depend on; maybe your already weakened immune system now finally gives out, making you more physically vulnerable to getting colds; or maybe the stress of dealing with grief on top of other problems exacerbates your diabetes.

“Unleash the power within,” declares self-help guru Tony Robbins, promising that you can “break through any limit and create the quality of life you desire.”3 Yeah, right. Tell that to a trans kid of color whose parents just kicked him out of the house with only the clothes on his back and open wounds from his last beating. Those slogans just serve to make people feel terrible when they somehow can’t “transform” their own lives. A positive attitude and a meditation practice are great, but don’t be surprised if they aren’t enough to save that kid. Nothing like that can (alone) bail them out so long as they’re denied the safety and support we all need to survive and thrive. They’d be much better served if a guardian angel provided a loving home and supported their education.

Don’t be suckered by stories of people who succeeded despite tremendous odds. Sure, they probably do have some remarkable qualities, like perseverance, intelligence, and grit. Consider Oprah Winfrey, a Black woman born into poverty and raised by a single teenage mom. The odds of her breaking out of poverty—let alone reaching the pinnacle of fame and material success—were certainly stacked against her. But Oprah didn’t break free of poverty alone. She had the support of a loving grandmother and a church community. She found encouragement from teachers who believed in her. She received a full scholarship to attend college. Her admirable qualities allowed her to leverage these resources; she didn’t do it alone.

Bettering our lives is a community endeavor, supported by individual effort.

My friend’s doctor advised her to exercise as a means of treating her heart disease. Well, duh. She didn’t need “expert” admonishment to know that exercise is valuable. She even had a treadmill in her house but was too stressed out from working two jobs and taking care of her kids to ever nail down an exercise routine. It was only after receiving a small inheritance from her uncle that she finally managed to start exercising regularly.

Am I suggesting that if you are overextended you should give up on exercise? Or pin your hopes on a surprise bequest? No! I am suggesting that you consider the conditions of your life first. Even if that seems pessimistic at first, it will help you conceptualize how and if that exercise routine is manageable. Your realism and understanding of your own situation may help you get it started, especially if it means you can avoid useless guilt for (understandably) not making exercise your top current priority.

RETHINKING DISADVANTAGE

I mentioned that Oprah was raised by a single teenage mom. What do the words single teenage mom conjure for you? On its own, the phrase is a setup that signals disadvantage. But if you toss aside our heteronormative “family values” bias, it’s not hard to see that the risks for children raised by single teenage moms may have less to do with their parent’s gender or relationship status or age than with financial instability, sexism, racism, ageism, and lack of social supports. Plenty of single mothers have the support they need to raise healthy, happy kids—even doing it better than many dual-parent families. Consider the many cultures where households consisting of multiple generations and extended family are the norm, providing a kind of small village to raise the kids. Remember to keep coming back to exploring systemic roots rather than making assumptions about individuals based on group status.

“LIFESTYLE” APPROACHES TO HEALTH IMPROVEMENT ARE INADEQUATE

If we pin everything on personal behavior change, whatever our concern—sickness, addiction, exhaustion—it’s reasonable to think we’re the problem. We imagine that what’s at work is not systemic injustice but individual maladaptation, requiring an individual response. The message is that it’s not society that’s sick or “crazy” or messed up; it’s you. There’s a term for that: gaslighting. Stress has been pathologized and privatized, and individuals are assigned the burden for managing it.

Even the most personal stress takes place within a social context. If we don’t address collective suffering and the systemic change that might alleviate it, wonderful techniques, like mindfulness as an example, lose their revolutionary potential and instead cause harm. The danger in a personal responsibility approach is not only personal, it also prevents us from considering a broader, more collective reaction to the crisis of inequity.

The “wellness” movement can feel like a religious cult. This may be easier to understand when you consider Karl Marx’s description of religion as the “opiate of the masses.” Though often misinterpreted, Marx was expressing collective responses to pain. Opium, at the time he was writing, was known not just as an addictive drug but as a painkiller, something that helps people tolerate unbearable conditions. Today’s self-help movement is our modern-day opiate of the masses, helping us tolerate difficult lives without challenging the conditions that create it.

Our lives are difficult because of injustice and hard circumstances, not our inadequacy as individuals to be resilient. Anything that helps us cope with the conditions that cause our problems but doesn’t engage with the root cause may only make things worse.

Resilience is conventionally defined as the ability to bounce back from difficult circumstances, but that definition falls short. Resilience also requires having the resources to support bouncing back. If resilience gets defined as an individual trait, individuals will get blamed for their inability to recover from adversity. Every challenge you experience personally, others have experienced too, another reason why resilience is not merely personal but relational, and why connection with others is essential to resiliency.

Consider, for example, how we interpret some of the maladies that trip us up. Did you ever have an asthma attack so severe you had to miss work? When resilience is considered an individual attribute, an inhaler may be prescribed. Yes, that may be helpful and allow you to get to work the next day, but it’s even more helpful to also talk to your neighbor. When you learn that most residents in your apartment complex suffer from asthma, you may be able to organize a collective response that, say, drives your landlord to clean up the damp, dusty, moldy conditions so you (and your neighbors) no longer need inhalers.

Viewing resilience as an individual endeavor may have helped manage the disease, in other words (an opiate for the masses), but viewing it as political, we simultaneously address systemic and personal change for a more lasting solution.

“LIFESTYLE” APPROACHES TO HEALTH IMPROVEMENT RELY ON PRIVILEGE

I used to be a big believer in promoting the idea that good health is achieved by taking personal responsibility for habits like eating well and exercising regularly. That’s much of the premise of my first book, Health at Every Size, often said to be the “bible” of the movement it’s named for.

I appreciate that the book has been transformative for many. I’m proud to hear ongoing stories from readers who tell me the book saved their life or invigorated their professional practice, inspiring a much more rewarding path. Yet now I can also see the limits of the personal responsibility argument, how it leads readers astray, and how it reflected my unexamined privilege.

Valuable as it may be, it’s also important to acknowledge that the ability to make personal behavior changes is a class privilege. By not naming this in my first book, I entrenched the problem. When not properly contextualized, a self-help book like the one I wrote takes responsibility off our culture’s shoulders. The shame I carry now is that this individualized response to health and eating, which I promoted in my first book, is still strongly embedded in many people’s conception of the Health at Every Size® movement. The ethos in my second book, Body Respect, coauthored with Lucy Aphramor, is different. It grounds the Health at Every Size concept in a social justice/systems-oriented frame. These newer ideas are supported and actively endorsed by the Association of Size Diversity and Health (ASDAH), the organization that has trademarked the HAES name, yet this approach does not have full traction in the HAES movement. I urge people who advocate for HAES to adopt this more updated understanding and to recognize the interplay between the personal and the political as we conceptualize healing. This requires a radical revisioning of health care and recognizing that it is not possible to define a health practice divorced of social context.

As Lucy Aphramor and I discuss in Body Respect, a focus on behavior change deflects attention from the more pernicious problem of systemic injustice, obscuring the reality that lifestyle factors account for less than a quarter of health outcomes. It puts the burden on the individual to assume personal responsibility for discomfort around food and weight and disease and adds a new stressor on one’s health, because it lets people be blamed for not doing more to manage or improve their health issues.

Maintaining the primacy of individual lifestyle change is also problematic because it diverts efforts from the more important systems-level issues which might be addressed through collective action. Additionally, it gives the false impression that lifestyle components, like eating and activity habits, are in fact individual “choices,” while ignoring the influence of social context and how it constrains or supports certain behaviors. Well-intended strategies like advising people to eat “a rainbow of foods” and prepare home-cooked meals are easier to follow if you have greater resources, like access to nearby grocery stores, money to spend in them, and time to cook up what you buy while it’s still fresh.

It is well established, too, that lifestyle-oriented changes yield greater health improvement for people with greater privilege in their lives. Paradoxically, some of the “downstream” methods of tackling inequalities in health can widen the very inequity gap they target.

To be clear, behavior change is valuable, but it can’t remove the stressors you face. No matter how you change your eating or activity habits, the factors that make up your lifeworld—challenges like stigma, job insecurity, poverty, and caregiver responsibilities—will remain unchanged. Naming inequity and systemically working toward a fairer world is important not just on a systemic level. On an individual level, naming and acknowledging the social roots of health inequities can help a person lighten up on the self-blame, realistically consider their life circumstances, and come up with solutions that best allow them to engage in self-care.

While health-promoting behaviors make sense for everyone, for individuals with hard lives, building a fairer society and helping them manage the challenges of poor treatment will matter far more to health outcomes than whether they eat their veggies. Focusing on systemic roots over individual-level paradigms helps not only marginalized people, but everyone, though the relative impact might be stronger for those who face more barriers.

THE SYSTEMIC APPROACH IN PRACTICE

If you’d asked me to write a chapter about behavioral practices for good health a couple of decades ago, I would have led with nutrition and exercise. It’s the common expectation—and believing in it is probably why I made it my expertise. When obtaining my PhD in physiology, I specialized in nutrition, and I also have a master’s degree in exercise science, in addition to a master’s degree in psychotherapy. I even taught college courses in nutrition for fifteen years. But that’s not how I’d do it today.

Examining our medical and social institutions’ default focus on nutrition and exercise, and my own past orientation, provides a good way to understand both what’s wrong with the old way of thinking about behavior change and how a systems-focused approach improves on the outdated models.

MYTH-BUSTING NUTRITION

First, nutrition. I’ve got a five-hundred-plus-page unpublished manuscript that I used as a textbook for students in my college nutrition courses languishing in my computer. It represents more than a decade of work. Yet it’s still unpublished, because I no longer think it’s right. I no longer believe in an emphasis on carbohydrates, protein, fat, vitamins, and minerals as the way to help people lead healthier, happier, more fulfilled lives. More rules and hang-ups about what to eat are precisely what we don’t need. For one thing (and maybe you’ll need to read this twice, it’s so counterintuitive), data show that people who care less about nutrition quality tend to eat more nutritiously than people who focus on diet.4 More than that, public health research into what affects our health finds that eating and exercise, combined, represent only about 10 percent of the overall impact of “modifiable determinants” (things we can change, as opposed to genetics).5 It’s also well established that health risks from the effects of stigma are far worse and make a much bigger difference than even the “unhealthiest” dietary habits.6

But, more important, I gave up this way of thinking because I’ve come to understand that most nutrition research conclusions are wrong. Hear me out. This topic has been well considered by many scientists who are busting the paradigm. Physician-scientist John Ioannidis’s report “Why Most Published Research Findings Are False” is the most cited paper in PLOS Medicine. As he aptly puts it, “claimed research findings may often be simply accurate measures of the prevailing bias.”7 In an opinion piece published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, Dr. Ioannidis bluntly states that nutrition epidemiology is in need of “radical reform.”8 To perfectly capture the absurdity of the field, he writes about what would happen if you subscribe to popular conceptions about what’s good and bad for you:

Eating 12 hazelnuts daily (1 oz) would prolong life by 12 years (i.e., 1 year per hazelnut), drinking 3 cups of coffee daily would achieve a similar gain of 12 extra years, and eating a single mandarin orange daily (80 g) would add 5 years of life. Conversely, consuming 1 egg daily would reduce life expectancy by 6 years, and eating 2 slices of bacon (30 g) daily would shorten life by a decade, an effect worse than smoking. Could these results possibly be true?

The answer to his rhetorical question is obviously no.

Ioannidis and his team—and others—have shown, again and again, and in many different ways, that much of what biomedical researchers conclude in published studies—conclusions that are used when we are advised to consume more antioxidants or less meat—is misleading, exaggerated, and often flat-out wrong. His work has been widely accepted by the medical community and published in the field’s top journals.

Ioannidis blames two major factors for this dissonance: confounding and selective reporting. Confounding describes the misconception that A causes B when, in reality, some other factor, X, actually causes B. For instance, eating sausage may be associated with a shorter lifespan. So eating sausage makes you die young. Oops! Confounding! Maybe sausage eaters die early because the same people who eat sausage are also lower in socioeconomic status. Lower socioeconomic status is the confounding factor and actually drives the shorter lifespans of sausage eaters. Confounding comes up all the time in weight and weight-loss research, a topic I have explored in depth in my previous books. It is true that many diseases are more commonly found in heavier people, for example. But you’d be wrong to conclude from that that high weight causes disease.

If yellow teeth are common among people with lung cancer, do yellow teeth cause cancer? Of course not. Epidemiological studies show us relationships, but not causality. Studies show an association between high weight and cardiovascular disease, for instance, but not the fact that heavier people experience a stress response resulting from weight stigma and that stress is a major factor in cardiovascular disease. And common sense tells us that yellow teeth, like lung cancer, can result from smoking. Smoking—like stress—is the confounder.

Much confounding is residual, meaning we can’t know if confounding is present unless we measure confounders. That doesn’t often happen. For example, if we don’t measure weight stigma, we’ll never know about its possible role in anything associated with fat. As there is compelling evidence that weight stigma causes much of the disease we blame on fat, this huge oversight means that our prescriptions are causing the very problem they aim to solve.9 To complicate matters, some confounders may not even be measurable, such as how a person’s lifestyle might change over time, their genetic and epigenetic background, or the interactions of foods in their diet.

Ioannidis’s second culprit, selective reporting, means that you’re likely to read a lot of confounding studies. Studies that confirm certain established (or profitable!) points of view, he shows, are more likely to reach print and pixels. So, because people tend to believe the nutrition-causation link, a report showing a link between sausage and early death is more likely to be published than one that doesn’t show that link. Research and conclusions that can be exploited by private industry are also more likely to be funded—and published—than research questioning those results. The food industry wields enormous influence over what questions even get asked, in addition to who asks them or how they are answered.

Speaking from my experience working in the field of weight science, academic careers depend on adhering to the status quo because research follows the money. Very little funding for “obesity” studies does not come from corporations who have a vested interest in the results. Even government funds are doled out by grant review committees composed of researchers with ties to private industry. In fact, I don’t know of a single “obesity” researcher involved in government grant review committees, government policy panels, or major “obesity” research organizations who does not have some financial tie to a pharmaceutical or weight-loss company.

Distinctions have blurred among private industry, science, government, and medicine, and the line between promoting health and making a profit has grown less firm than you might imagine. Much of what is believed to be true about nutrition reflects the values of the food, diet, and wellness industries more than scientific fact. It’s akin to letting the coal industry teach us about climate change.

Have you bought into the nutrition myths? Most of us have. It would be hard to exist in this culture without absorbing some of its mythology. Hint: if you’ve ever jumped on the bandwagon for a Paleo, gluten-free, low-carb, low-fat, low-salt, high-protein, or alkaline diet; or stocked up on a “superfood”; or avoided dairy or sugar, this includes you. Sure, some dietary restrictions make sense for individuals with specific diseases—forgoing gluten if you have celiac disease, for instance, or dairy if you’re lactose intolerant—but no well-supported evidence proves that such “eliminations” can help any outside those minorities of sufferers.10

I write this knowing it will inflame some readers who are invested in their food hang-ups. Engaging in critical thought about our own buy-in to mythology can feel threatening. It is particularly insidious because our allegiance to those myths links so closely to our sense of self. When a nutrient or food is portrayed as offering an opportunity for long life, or to allow us to be seen as attractive and smart, or to get more done in the day, it plays on our insecurities. Adhering to nutrition beliefs can give us a sense of belonging and even a feeling of moral superiority—that we “know” what’s best. Like religion. Also like religion, nutrition myths tend to tie us to myths of paradise past; indeed, the idea that we need to return to the diets of our ancestors seems to have a particular hold on people. It feeds off a sense that modernity is dangerous and unnatural, causing us ills from which only a get-back-to-nature diet can save us.

Our food fears get bolstered and legitimized by the claims of so-called lifestyle diets. Keto, Paleo, and gluten-free diets, for example, provide socially acceptable avenues for food fears and restrictions, veiled in health tones, which provide cover for the emerging diagnosis of orthorexia.* Avoiding sugar is seen as morally superior and wholesome, rather than recognized as a symptom of disordered or restrictive eating.

Experience shows me that asking people to challenge their belief system about particular foods or diets is akin to asking them to change their religion. It threatens their identity and a history of time, energy, and money invested in something that may not have been in their best interest. Their belief system not only nurtures their internal beliefs (if in a perverse way), it may buy them social currency or gain them acceptance and respect in their profession.

Assumptions about food and bodies are so deeply rooted and culturally supported that we may not even recognize them as ideas—opinions, really—to be analyzed and challenged. The difficulty some people may have in moving to an understanding that dieting, for example, is more likely to result in weight gain than weight loss, and that the pursuit of weight loss is damaging, not health promoting,* may be so overwhelming as to set up vehement—and sometimes unconscious—resistance. Particularly as this is tied to the fantasy of a better life, it may feel as if I’m taking someone’s hope away.

Nutrition’s role in good health is wildly exaggerated and misunderstood. Even in diseases where food choices play a more explicit role in management—as in celiac disease, lactose intolerance, or heartburn—a focus on putting what you know about how foods affect your disease into the context of your life is key to being able to implement any dietary changes. I’m not suggesting people ignore nutrition entirely—just that we put it into perspective. You need a critical mind to do that.

We build our lives and identities around powerful myths. We’re fed fantasies that eating a certain way leads to easy weight loss, guaranteed health, or simple self-cures. It’s easy to get suckered in. But I assure you, there is no magic in eating in a particular way.† The real secret to eating well depends on dumping food rules and mythical thinking.

EATING THROUGH A SYSTEMS-INFORMED LENS

Consider this anecdote: A woman believes that she is too fat and wants to lose weight. By cutting back on her calories in recurrent bouts of restrictive eating (dieting), she’s temporarily successful, losing a few pounds a few times. As a result of so-called “successful” dieting, she also finds herself uncontrollably binge-eating at times—something she’d never struggled with before. A “behavior change” (also known as “lifestyle change”) approach would have the woman attempt to change her habits around food, by following a dietitian-prescribed diet, for instance, or trying to eat more intuitively.

A systems approach would have the woman take a step back and look at the systemic roots. While food habit change may be a part of the “solution,” it leaves unchanged those social contexts that affect how she feels in her body and why she wants to lose weight. Looking to systems, we might work with the woman to explore how social determinants have a personal impact—for example, having the woman unpack the sexist advertisements that surround us and how she feels when she consumes this media. The idea is not that knowing that painful embodied experiences are rooted in systemic issues will somehow make a person immune to feeling the effects of these systems. Rather, it is acknowledging that these systems persist and that her body dissatisfaction and efforts to change take place within an unsupportive environment. By addressing the roots of why food is so conflicted for them, people are then empowered to make the individual changes that may be most helpful.

My first book encouraged “intuitive eating,” an approach created and popularized by dietitians Evelyn Tribole and Elyse Resch in their 1995 book of that title.11 Their model was subsequently validated by the research of Tracy Tylka and colleagues and continues to evolve.12 As Tribole describes it, “Intuitive eating is a personal process of honoring health by listening and responding to the direct messages of the body in order to meet your physical and psychological needs.”13 I’m still on board with this concept. Applied in the right context, a transition from dieting to intuitive eating has been life-saving to many.

When context isn’t considered, however, there are undeniably classist undertones to promoting intuitive eating. For those in privileged social positions, choosing foods and amounts that intuitively appeal might be a possible approach to eating, but for others, systemic conditions may not permit just following their bodies’ cues. Consider a single mother who works full-time while also attending school. She struggles to find enough time and money to feed her kids, so eating necessarily takes on a pragmatic and functional role. She cannot simply decide to eat what she would most prefer at any given time. She may have to go beyond a comfortable level of fullness when food is available—for instance, if she has a free meal available at her restaurant job that she is not allowed to pack up and take home. Stopping at Burger King for Double Whoppers on the ride between school and daycare may be the most affordable and expedient choice for feeding the kids. Advising this woman to eat what she truly wants and stop when she is full is likely to only exacerbate the stress she may already feel by making her feel she is doing health “wrong.” Her current strategies meet her conditions for time, money, convenience, and all the other values helpful in a decision of what’s really going to be the most nourishing self-care.

Of course, spaces of belonging like class do not operate in isolation, either. Taking a systems approach also means considering how people relate to their bodies and their choices around food in relation to cultural stereotypes and tropes. Returning to our example, we might also consider how racism and sexism impact this woman’s food choices (she is Latinx). She may face issues like unequal pay, further constraining her financially. Damaging ethnic tropes such as the stereotype that Latina women are pigeonholed as hypersexual may also lead to problematic beliefs about her body or her single mother status. These stereotypes may interact with each other and with classist assumptions to generate significant stress, which in turn may impact the way she experiences her body and makes choices around food.

Besides sexism, classism, and racism, a blanket prescription to listen to your body may fail in other ways. For example, it assumes that body signals are working appropriately, which may not be true for people with a history of trauma. A strong impulse toward body harm is not uncommon for trauma survivors and others. Body wisdom is not always to be trusted for other reasons as well. Remember our earlier discussion of how unconscious bias wires into us? We’re predisposed to think in stereotypes and culturally accepted values. You’ve absorbed messages from diet culture that influence your food and eating preferences but may not be in your best interest.

Returning again to our example, I want to remind you, too, of the need to challenge conventional ideas about coping behaviors. Rather than being a sign of failure of will or character or a response to unmet emotional needs, for example, bingeing is often the body’s attempt to restore health. The drive for calories that is at the root of a binge is likely a direct result of restrictive eating. In other words, the diet is the problem, and the binge the body’s attempt at a solution. Help comes when we address the root problem—the diet. In this vein, we can show appreciation for the binge as a temporary solution when we don’t have other skills—and focus on a more long-range solution to the problem of dieting consistent with ideas expressed in chapters 4 and 10.

Intuitive eating can be a tool to help people cope no matter what circumstances they’re in, but it must be approached in a nuanced, trauma-informed, and social-justice-informed way. When we don’t consider people’s individual stories, we reinforce dominant narratives and cater to more privileged people by default.

Instead of first prescribing behaviors, we can help people examine the conditions of their lives that support and inhibit self-care. We can help them take stock of both challenges and resources in their lives to support them in moving away from self-blame and finding their power. Addressing the social determinants of health gives people the skills and control over their lives to improve self-care. Only then can practical discussions follow of appropriate, manageable, and compassionate self-care, whether it’s being more thoughtful about hunger cues, stocking up on frozen veggies, or shoring up defenses to manage stigma and injustice. That helps us get at the crux of the matter.

Centralizing social justice means that you start from the perspective that our individual stories matter, looking at how we live our lives in relation to others and to power structures that open or constrain our options.* Without deliberately choosing this perspective, there is a tendency to default to the dominant narrative that renders invisible the struggles facing marginalized groups and how these barriers limit everyone’s ability to be authentically and fully seen, to become aware of a fuller range of potential solutions, and to define what self-care means for them. Only after we have explored people’s life circumstances can we consider what appropriate self-care looks like. Eating apples makes sense in some circumstances, while choosing French fries is far more valuable and health-promoting in others.

EXERCISE THROUGH A SYSTEMS-INFORMED LENS

To understand how a systems-informed lens can improve health behaviors, consider a different approach to self-care, one that’s embedded in a social context. I’ll use exercise as an example.

Few people would argue with the suggestion that exercise enhances health and well-being. Yet, this awareness rarely seems effective at motivating or sustaining active lifestyles. Nor does shaming people about their weight. Even if exercise helped people lose weight—and research shows it doesn’t—the promise of weight loss hasn’t proven to help people sustain a regular exercise habit.

On the other hand, a “systems approach” to increased exercise proves much more valuable. To see what that might look like, try the reflection exercise that follows. You can do it as a solo writing exercise, but it’s best if you do this with a partner or a group so you’ll be exposed to valuable ideas that you may not have thought of on your own.

I’m going to ask you to think back to different times in your life. If you think using different ages than I suggest will help you capture time periods in your life that were significantly different from one another, please adjust.

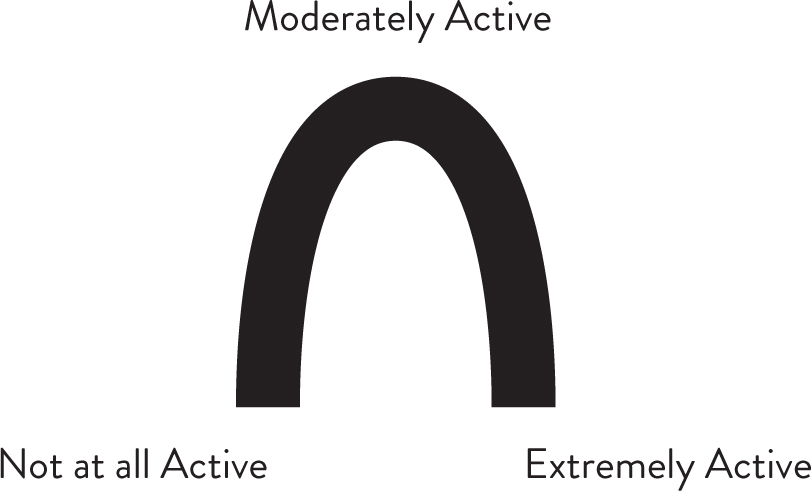

To help us see this more literally, I drew a picture representing a continuum of the amount of activity you get in a day.

As you can see, I’ve asked you to view the bottom left of the horseshoe as representing no participation in activities, the middle as representing moderate levels of activity, and the right end representing participating in extreme amounts of activity.

Think back to when you were nine years old. Put a mark on the horseshoe that represents how active you were, with your age (9) next to it. Consider these questions:

•How active were you and what were you doing?

•What did you like about it?

•What helped you achieve that level of activity?

•What hindered your activity?

Try to make these observations nonjudgmentally. If you are doing this exercise with a partner or group, discuss your answers. If you are doing this solo, write them.

For ages sixteen, twenty-five, and your present age, also mark the horseshoe, write your age, and answer the questions above. (If you’re younger, modify accordingly.) If there’s another time period that seems significant to you, explore that, too.

Now it’s time to analyze your data.

First, notice whether your activity levels changed over time. If they didn’t, I promise you that at some point they will. If nothing else causes a change in habits, injury or aging will.

For most people, activity levels change over time. This is an important point because it helps us understand that the conditions of our lives help establish our activity habits and attitudes. For example, my parents would send me out as a nine-year-old kid to play. That was my job. There were a lot of kids in the neighborhood, and the cul-de-sac kept us safe and confined. Several families had pools in their yards, and we had plenty of green space. I was a good athlete, and playing sports got me attention and respect. I also remember it being fun. All of these factors contributed to my being regularly active.

At sixteen, likewise, I played on several high school and intramural sports teams, continued to enjoy sports, and continued to appreciate the attention for being a good athlete.

At twenty-five, my activity level had dropped off. I was working long hours and found it hard to find the time for sports. My activity level has been inconsistent through much of my adult life, slowing when I’m injured or overextended with work, increasing during warmer weather and family vacations.

Reflect on your exercise history and consider what conditions supported you in exercising regularly and what hindered you. For me, the supportive standouts would be whether an activity is fun and social. The biggest hindrance is lack of time.

Do this in a group and you will learn a lot more from others’ experiences. This exercise helps me become aware that if I want to be more active, the key for me is to try to make it social, like getting on a team or participating in classes. When I’m overextended with work, I have to get more creative about making activity be part of what I do so it doesn’t require extra time—like biking to appointments, having walking meetings with my colleagues or students, and so on.

Unlike me, you may discover that your hindrances stem from your attitude toward your body. When I was a kid, if your body served as a big target in grade school dodgeball, it was like kids had license to bully you. It makes sense that experiences like this color our current attitudes.

Whatever you discover from this activity, that’s where the intervention lies. Approach this from a compassionate stance and consider how to maximize your resources and work through your challenges. What challenging conditions in your life are changeable? What are the activities that can be supported by the current conditions of your life? What resources can you grab onto?

Think critically, too, about your beliefs about exercise. For example, if you sometimes get on exercise kicks to lose weight, it may be helpful to know that’s a myth. “What?” you might ask. “If I believe that, I might stop working out altogether!” In fact, though, the opposite is true. This awareness is important for many reasons, not the least of which is that when people exercise only for weight loss, they often give up on exercise when it doesn’t have the desired result.

Research also shows that vigorous exercise is fun for some but not everyone, and that’s supported by biochemistry. People vary in to what extent we secrete hormones (like endorphins) that lead to a “runner’s high” feeling, making vigorous exercise more rewarding for some of us. Secrete a lot of endorphins and it may drive a strong desire for exercise and a feeling of dissatisfaction without it, fueling an exercise habit. Others may not get as much of a pleasure reward and likely won’t be as athletic as their exercise-loving counterparts.

There is no “one size fits all” activity plan. As we all have different attitudes toward our bodies and movement and respond differently to activity, we need to address the meaning of activity in a person’s life, and to get creative about how we can meet the need for movement.* A “just do it” attitude is not the answer.

WEALTH AND EMOTIONAL RECOVERY

As we’ve discussed, we can’t separate the personal from the structural.

Many people are poor because of structural forces, like a labor market offering insufficient jobs at good wages, mass incarceration as the means for addressing drug problems, or lower pay for women compared to men and for People of Color compared to white people. According to US census data, on average, in 2017 women were paid 80 cents to every man’s dollar.14 It’s significantly worse for Women of Color: Black women earned just 61 cents and Hispanic women earned just 53 cents for every dollar white men earned.15

And in case you buy into the myth that education is the great equalizer, let me dispel that, too, as it doesn’t shield Women of Color from the pay gap. The pay gap actually widens for women at higher education levels and is largest for Black women who have bachelor’s and advanced degrees.16 Black women in particular trail behind in terms of income no matter how closely they follow the educational guidelines. Given the barriers Black women face at every step along the way—in being admitted to college, paying for college, and managing student loans—higher education is a massive undertaking without guarantees of financial payoff.

Transgender Americans also earn significantly less, experiencing poverty at double the rate of the general population, with transgender People of Color experiencing even higher rates.17 The National Center for Transgender Equality has found that 43 percent of Latino, 41 percent of Native American, 40 percent of multiracial, and 38 percent of Black transgender respondents lived below the federal threshold for poverty in 2015.18

Disabled people suffer from income inequality too; research consistently finds they are less likely to be employed than non-disabled people, and when employed they receive, on average, lower pay.19 Including workers of all occupations, those with a disability earn 66 cents for every dollar those with no disability earn.20

Most inequality analysis focuses on income rather than wealth. While income inequality is stark, it pales in comparison to wealth inequality. (“Wealth” refers to total assets minus debts, so it’s a different measure than income, speaking to a larger history of money.) Women own only 32 cents on the dollar compared to men.21 For Women of Color, the gap is a far worse: median wealth for single Black women is just pennies on the dollar compared to white men and white women.

Let me help put this into perspective by examining my own financial and educational background. You may have heard the expression “born with a silver spoon in their mouth.” That phrase describes the life I was born into, almost literally. For those of us with a social justice lens, it’s a derogatory trope, implying a sense of entitlement rather than recognition of the unearned advantages that led to the wealth. My parents didn’t see it this way. They were so proud to be able to offer me opportunity that they actually bought a silver baby spoon and engraved it with my name and birth date to commemorate my birth.

My parents were proud of what our family had accomplished. Their parents came as penniless immigrants to this country, Jews escaping the pogroms of Poland, and only a generation later, my parents were thriving in the upper middle class.

We descended from people victimized by racial genocide overseas and continued to be victimized by anti-Semitism in this country. The narrative my parents imparted to me—and believed—was that anyone who tries hard enough could overcome adversity and succeed, that we had worked hard for and deserved our wealth and advantage. While the hard work was certainly true, this narrative invisibilizes the skin-color privileges that supported our success: from hiring advantages and GI Bill coverage for education and home ownership (which was often inaccessible to People of Color), to bank loans (often refused to People of Color), redlining (the practice of differentiating areas of a city by race, often leading to the denial of necessary goods and services to People of Color), police protection (not similarly granted to People of Color), and much, much more. Others who work just as hard but have fewer advantages don’t get this outcome.

A deeper dive into family history reveals even more flaws in the notion that we live in a meritocracy. Consider my grandmother’s story—she went from “rags to riches,” seemingly embodying the American dream. Yet the backstory shows how illusory this is.

My grandmother came to America as a preteen, fleeing the Nazi occupation of Poland prior to World War II. The Nazis had occupied her home, stealing her family’s food and belongings, terrorizing them, and relegating them to the floor while the police occupied their beds. Upon immigrating to the United States, she moved in with extended family in a tiny cramped tenement apartment on the Lower East Side of New York City. She spoke no English and got the only job available to girls in her situation, working long hours under unsafe conditions in a silk factory, where she was horribly exploited. Her family members worked similarly hard. All the family’s earnings went toward survival; they struggled to make it, sometimes going hungry. Later, when they had greater income, the money was invested in my grandmother’s brothers’ education and denied to her.

Seeing no way out, my grandmother demonstrated extraordinary ingenuity: she stole a sewing machine and fabric and built a small business in the little time she had away from her factory job. She learned English and absorbed silk trade lore by listening to conversations among her bosses at work. The business she started, later called Bacon & Graham, thrived and was passed through my father to, at present, my brother. It’s grown through the past eighty years, now employing over fifty people.

I asked my grandmother to tell me about Graham, presumably her business partner. The day she answered that question was the day I became a feminist.

My grandmother told me that nobody would do business with a woman, so she invented a fictitious male business partner. When people asked to speak to Mr. Graham, she would say, “Oh, Mr. Graham’s not available right now, but he’s asked me to help you.”

So, let’s review. How did my family fortune get started? Criminal activity (stealing) helped them overcome anti-Semitism and discrimination against immigrants, later bolstered by lying to combat sexism, and greatly supported by the racism that provided opportunities to white people while discriminating against People of Color.

Did my family work hard? Absolutely. But many people do. These stories are just a small snippet of the many unearned advantages I have had that paved the way for my financial success. As another example, it was easier for me to do well in college because it was paid for, along with my living expenses, by my parents, freeing me to focus on my studies.

My parents kept that engraved silver spoon in a safe deposit box, giving it to me on the day of my bat mitzvah. For them, it was an assertion of their commitment to providing advantages to support my success. For me, it’s a reminder of injustice, that I didn’t earn my financial advantages, and the responsibility that comes with that.

Incidentally, spoons are also an important metaphor in the disability community, yet with a very different meaning.22 For people with disabilities, spoons represent the emotional resources a person has to draw from. Everything one needs to do throughout the day requires emotional resources, represented by a certain number of spoons. The spoons are replaced only when one rests and replenishes. If you run out of spoons, you are depleted and have nothing more to give to your day.

This metaphor conveys that for some, particularly people with disabilities, energy must be rationed, and it calls attention to what it takes for them to manage and accomplish tasks. Able-bodied people are less likely to consider energy expended on ordinary tasks like showering or getting dressed. Spoon theory explains the difference between those who don’t seem to have energy limits and those who do.

It is not without irony that I note the contrast between the spoon metaphor in the two cultures. In my parents’ culture the spoon is about unexamined privilege, signifying a celebration of wealth, a belief that it is deserved, and speaks to flagrant spending. People with disabilities don’t have the luxury of not seeing their disadvantage; they need to remain aware that they have limited resources for survival so they can ration and conserve.

Something is wrong here. This is why our financial resources, health outcomes, personal care behaviors, and more need to be understood in a social context. Chalking health up to individual responsibility clearly misses the mark.

PRIVILEGE AND RESPONSIBILITY

The struggle to survive in an unjust society requires one to find wellness mechanisms to maintain a commitment to self, healing, nurturance, and community. It is the duty of all of us, but especially those with power and privilege, to dismantle the systems that harm us.

Having the tools to develop the intention and praxis of liberation requires doing the work on ourselves and actively dismantling systems we benefit from. Hunter Ashleigh Shackelford, a non-binary Black fat cultural producer, multidisciplinary artist, and community activist, shared with me some tangible ways in which non-Black people, especially white people, can show up and work to undo some of the damage that underlies our collective trauma and prevent it from going forward:

•Make reparations. We must be committed to giving property and financial resources to Black communities. Healing starts with acknowledging our legacy of contributing to and benefiting from the oppression of Black people globally.

Here are some examples of worthwhile reparation efforts: donating to crowdfunding campaigns for individual Black people; amplifying Black people’s work on social media; giving property; providing mental health services; offering vouchers for food, scholarships, and paid internships; donating time and labor to Black entrepreneurs; paying for child care for Black families; providing a platform for Black people to speak.

•Decolonize. It will take longer than our lifetimes to decolonize ourselves from systems of oppression that have existed for hundreds of years. But we can make a commitment to disrupt the historical trauma that gets carried from one generation to the next. This trauma consists of not just pain, but also the unconscious bias we pass on and the violence we inflict without knowing why we’re doing it.

The work of decolonization requires learning (and relearning) how to humanize everyone, especially those across races and those descended from the African diaspora. Here are some steps to take to begin this project: Have difficult conversations with those who look and identify like you about how to unpack the internalizations of bias and violence toward those different from you. Be vulnerable enough to recognize that your privileges can lead you to make decisions or implement violence that you may not even realize, but that can deeply harm marginalized communities. Fight like hell for the world you want to live in and who you want to be within that world.

•Repeat. Audre Lorde said, “Sometimes we are blessed with being able to choose the time, and the arena, and the manner of our revolution, but more usually we must do battle where we are standing.”23 That is our call to action to develop ourselves when there’s no one watching, when there’s not a conflict to deescalate, when the goal is a freedom we cannot feel yet. We must be committed to moving tangible resources into Black communities and to the internal decolonization of the legacy of trauma we have inherited. Anything less represents complicity with the status quo.

Shackelford’s excellent recommendations apply specifically to mitigating white supremacy and supporting Black liberation, but I hope they’ll also help you to reflect on how you can support liberation from other sources of oppression.

BRINGING IT HOME

Self-help fails to deliver to the degree we’ve come to expect as it puts the responsibility on us as individuals and deflects attention from the inequitable access to resources and opportunity that support positive change. Leveraging resources will take you further than you can ever go alone. Supportive families, employers, communities, and governments play a larger role in improving our lives than do our efforts at self-improvement. We can all play a role in providing opportunity for others to thrive and in advocating for systemic change. Now that you better understand this context and its importance, let’s turn to resilience strategies and the practical information you need to heal.

*Orthorexia refers to a disorder that includes symptoms of obsessive behavior in pursuit of a healthy diet. It is not currently an official diagnosis formally recognized in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (DSM-5).

*My previous books get you up to speed on these.

†I want to be clear: For people with certain disorders or diseases, dietary manipulation may be a medical necessity. But the benefits received by a person who has celiac disease when they avoid gluten aren’t magical.

*Hat tip to the Black Lives Matter movement for bringing attention to the fact that All Lives Don’t Matter until Black Lives Matter.

*For some folks, like people with exercise compulsions or histories of disordered eating, sometimes the most self-caring thing you can do is not exercise. Trust that instinct (or your health care providers, if they’re recommending stopping exercise) and know that eventually you can get to a place where movement is part of your life again.