Chapter 2. Recent trends in regulatory management practices

Whilst most countries have made some improvements to their regulatory management systems and practices over the last years, few have undertaken comprehensive reforms. In particular, ex post evaluation of regulations remains relatively undeveloped without consistent review methodologies. More needs to be done to ensure that OECD countries reach the agreed standards for their regulatory management practices – namely, the 2012 Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance – in a timely manner. If further improvements are not forthcoming, economies will be slowed by unnecessary burdens, thereby threatening future prosperity. This chapter focuses on recent trends in three key elements of the 2012 Recommendation: the engagement with stakeholders and the use of evidence in the development and revision of regulations.

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Key findings

The global financial and economic crises, and their aftermath, have uncovered stark failings in governance and regulations across the globe. Amid ongoing economic uncertainty, it is imperative to ensure that markets and economies more broadly are able to deliver for all. Against this backdrop, the 2012 Recommendation was developed to help ensure that economies can be put on stronger regulatory footings so as to improve growth. Stakeholder engagement, regulatory impact assessment (RIA), and ex post evaluations are three key enablers to improve regulatory environments across OECD countries. However, despite their importance, countries have been slow to adopt and deepen regulatory management practices to improve the lives of their citizens.

Since 2014, OECD countries have made some improvements in their use of stakeholder engagement and RIA to support the development of laws and regulations. That said, the regulatory lifecycle remains incomplete as ex post evaluation remains less developed.

At a time of general mistrust of governments, it is imperative that consultation with stakeholders provides a meaningful avenue for those affected to be able to help best shape regulations so as to maximise overall well-being. Countries are increasingly seeking feedback from citizens and businesses about regulatory proposals. Nevertheless, consultation could be better integrated into regulatory decision-making. In particular, regulators could better demonstrate how consultations have affected the final development of laws.

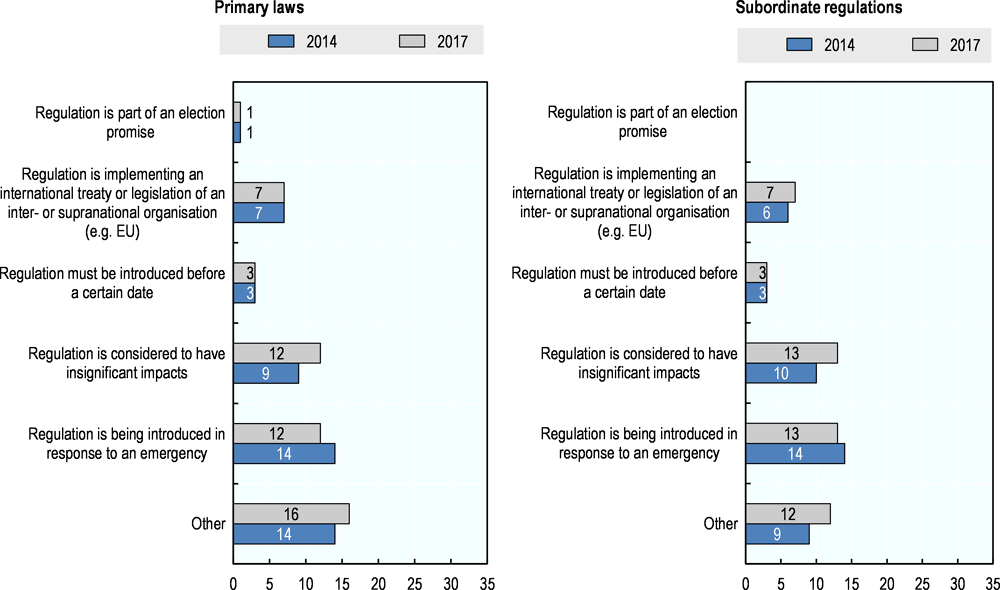

RIA is a central aid to decision making, helping to provide objective information about the likely benefits and costs of particular regulatory approaches, as well as critically assessing alternative options. A growing number of countries apply a proportionate approach to decide whether or not RIA is required and to determine the appropriate depth of the analysis. Whilst this is praiseworthy, it is important to note that a number of countries are excepting regulatory proposals from regulatory management practices, particularly those with significant impacts. This can have the effect of undermining public trust in countries’ regulation making processes. It is therefore important that there is strong political support for the continued use of RIA to help better inform decision making.

The stock of regulations is far larger than the flow, yet scant attention is often paid to regulatory proposals once they have become laws. Ex post evaluation is thus a crucial tool to ensure that regulations remain fit for purpose, that businesses are not unnecessarily burdened, and that citizens’ lives are protected. Yet despite this, there has only been a minor increase in the number of countries that have formal requirements and a comprehensive methodology in place for ex post evaluations.

Although there have been some improvements in the adoption and use of regulatory management tools, they need to be seen in context. The normative framework has long been agreed between members, which ultimately culminated in the 2012 Recommendation. Nevertheless, whilst there have been some notable reforms undertaken, members remain a long way from meeting the 2012 Recommendation.

Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of recent trends and the progress made by OECD countries in implementing the 2012 Recommendation (OECD, 2012[1]). It focuses particularly on stakeholder engagement, regulatory impact assessment (RIA) and ex post evaluation of regulations, where:

-

Stakeholder engagement refers to informing and eliciting feedback from citizens and other affected parties so that regulatory proposals can be improved and broadly accepted by society

-

RIA refers to the process of critically examining the consequences of a range of alternative options to address various public policy proposals

-

Ex post evaluation involves an assessment of whether regulations have in fact achieved their objectives, as well as looking as to how they can remain fit for purpose.

These three areas are important regulatory management practices, forming critical aspects of the regulatory lifecycle.

The analysis is based on results from the 2017 OECD Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance (iREG) Survey, which covers 38 OECD member and accession countries and the European Union. It is the second time, after 2014, that the survey has been run, thereby allowing for the first comparative analysis of trends and improvements in regulatory policy across countries. Graphs over time cover only the 34 countries and the European Union for which data is available for both 2014 and 2017 to facilitate comparison, unless indicated otherwise.

Content of regulatory policies

OECD countries have demonstrated a strong in-principle commitment to regulatory management via the widespread publication of regulatory policy documents. However, the basis and content of various policy documents vary across countries.

Whole-of-government approach for regulatory quality

OECD and accession countries continue to invest in their whole-of-government approach to regulatory quality (Figure 2.1). The vast majority of them have adopted an explicit regulatory policy promoting government-wide regulatory reform or regulatory quality and established dedicated bodies to support the implementation of regulatory policy. They also generally have a specific minister or high-level official who is accountable for promoting government-wide progress on regulatory reform. Countries also continue to use standard procedures for the development of primary laws and subordinate regulations.

Notes: Data for OECD countries is based on the 34 countries that were OECD members in 2014 and the European Union. Data on new OECD member and accession countries in 2017 includes Colombia, Costa Rica, Latvia and Lithuania.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933813951

Application of regulatory management tools to laws initiated by parliament

In most countries, processes and requirements with regards to the use of better regulation tools in the development of new laws seem to focus mostly on laws initiated by the executive. Only in a small minority of OECD countries do the same processes apply to laws initiated by parliament as for the executive (Figure 2.2 and Figure 2.3).

Note: Data is based on 34 OECD member countries.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933813970

In a small minority of OECD countries, there are specific requirements to conduct stakeholder engagement and RIA to support the development of laws initiated by parliament.

Note: Data is based on 34 OECD member countries.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933813989

Evaluation of regulatory policy

Information on the performance of regulatory reform programmes is necessary to identify and evaluate if regulatory policy is being implemented effectively and if reforms are having the desired impact. Regulatory performance measures can also provide a benchmark for improving compliance by ministries and agencies with the requirements of regulatory policy (OECD, 2012[1]). Since 2014, OECD countries have further invested in the evaluation of the use of regulatory management tools. RIA continues to be the most evaluated tool in OECD countries with two thirds of OECD countries having evaluated how it functions in practice (Figure 2.4).

However, reports on stakeholder engagement practices and ex post evaluations are far less frequent. While the number of reports for both have increased since 2014, less than one third of OECD countries are currently reporting on their stakeholder engagement practices and ex post evaluations.

Note: Data is based on 34 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814008

General trends in the adoption of regulatory management tools

Progress towards achieving the 2012 Recommendation in the three focus areas of stakeholder engagement, RIA, and ex post evaluation is partly measured via composite indicators based on information collected through the iREG survey (Box 2.1).

Box 2.1. Construction of the composite indicators

The three composite indicators provide an overview of countries’ practices in the areas of stakeholder engagement, regulatory impact assessment (RIA) and ex post evaluation. Each indicator comprises four equally important and therefore equally weighted categories:

-

Systematic adoption records formal requirements and how often these requirements are conducted in practice.

-

Methodology presents information on the methods used in each area, e.g. the type of impacts assessed or how frequently different forms of consultation are used.

-

Oversight and quality control records the role of oversight bodies and publically available evaluations.

-

Transparency records information which relates to the principles of open government, e.g. whether government decisions are made publically available.

The maximum score for each category is 1 and the maximum score for the aggregate indicator is 4. The composite indicators are based on the results of the OECD 2014 and 2017 Regulatory Indicators Survey, which gathers information from all 38 OECD member and accession countries and the European Union as of 31 December 2014 and 31 December 2017, respectively. The survey focuses on regulatory policy practices as described in the 2012 Recommendation (OECD, 2012[1]). The more of these practices a country has adopted, the higher its indicator score.

The questionnaire and indicators methodology were developed in close co-operation with delegates to the Regulatory Policy Committee and the Steering Group on Measuring Regulatory Performance. The methodology for the composite indicators draws on recommendations provided in the 2008 JRC/OECD Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators (OECD/EU/JRC, 2008[2]). The information presented in the indicator for primary laws on RIA and stakeholder engagement only covers processes of developing primary laws that are carried out by the executive branch of the national government. The information presented in the indicators for primary laws on ex post evaluation covers processes in place for both primary laws initiated by parliament and by the executive.

Whilst the indicators provide an overview of a country’s regulatory framework with respect to stakeholder engagement, RIA and ex post evaluation,, they cannot fully capture the complex realities of its quality, use and impact Moreover, they are limited to evaluating the implementation of measurable aspects across the three areas currently assessed and do not cover the full 2012 Recommendation. As such, a full score does not imply full implementation of the 2012 Recommendation. In-depth country reviews are therefore required to complement the indicators and to provide specific recommendations for reform. Please also note that the results of composite indicators are always sensitive to methodological choices and it is therefore not advisable to make statements about the relative performance of countries with similar scores.

Further information on the methodology is available at www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/measuring-regulatory-performance.htm, as well as via an OECD working paper (Arndt et al., 2015[3]). Further analysis of the 2014 iREG survey results were made available through a subsequent working paper (Arndt et al., 2016[4]).

Additional analysis of the results of the 2017 iREG survey by the OECD will be available via an analytical paper (Arndt, Davidson and Thomson, forthcoming[5]).

Please see also the reader’s guide at the beginning of the Regulatory Policy Outlook.

On average, countries have made small improvements in the uptake of regulatory management tools since 2014 (Figure 2.5), with changes of a similar magnitude across the three tools and with respect to both primary and subordinate regulations. Strikingly, ex post evaluation remains the least developed regulatory management tool overall despite the large potential for reform: Countries would benefit from improving the stock of regulation, which is much larger than the flow, to ensure regulations are still relevant, do not impose unnecessary costs on society and do not lead to unintended consequences. For example, reforms to anticompetitive regulation in Australia during the microeconomic reform programme of the 1980s and 90s were estimated to yield gains totalling some 5% of GDP, with households across all income groups significantly better off (Australia Productivity Commission, 2006[6]; OECD, Forthcoming[7]).

Notes: Data for OECD countries is based on the 34 countries that were OECD members in 2014 and the European Union. Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814027

On average across the composite indicators, systematic adoption continues to be the strongest area throughout OECD countries, indicating that the foundations for better regulatory management practices including formal requirements are in place. It is nevertheless noticeably weaker for ex post evaluation, which would indicate less political commitment and also an easy area for improvement.

Methodology has remained behind systematic adoption, and is the second-strongest category. This would suggest that once countries have the systematic ‘building blocks’ in place, they are next focussing on improving their technical capabilities across stakeholder engagement and RIA, in particular.

Transparency has remained relatively weak across OECD countries. It would be anticipated that once the systems are in place with sound methodologies, countries will be able to improve the transparency of their regulatory management practices.

Oversight is still underdeveloped relative to the other three categories, which was also the case in 2014. This suggests that there are real gains that can be made by OECD countries with regards to improving the quality control of regulatory proposals.

It is worth noting that although the overall pace of change is slow, some countries have made significant progress in their regulatory management practices since 2014. Across the three areas, major reforms have been undertaken in Israel, Italy, Japan, and Korea.

-

Israel has made significant progress in strengthening its regulatory policy since 2014. It now has in place stricter rules and guidance for RIA, while the central focus is on regulatory burden reduction including an extensive programme on reviewing existing regulations with respect to the burdens they impose. Stakeholder engagement is now a central part of RIA, although it should be noted that there is no external quality control of RIAs in Israel and the Better Regulation Department does not have a gatekeeper function.

-

Italy recently updated its procedures relating to regulatory management practices, tackling some of the challenges identified in the Regulatory Policy Outlook 2015 (OECD, 2015[8]). Stakeholder engagement has been improved via the introduction of a section in the central government website, RIA quality control has been strengthened, and procedures around ex post evaluations have been improved, although they could be more systematically planned.

-

Japan has made significant efforts to improve its regulatory environment since 2014. It has updated its guidance material for RIA, with a particular emphasis on the importance of conducting a thorough impact assessment of a policy, including the various techniques and processes that ministries can adopt. There are also strengthened rules requiring ex post evaluations within the first five years of new laws. These improvements may yield further benefits if stakeholders were able to be better involved ex ante in the policy development process, and in ex post reviews.

-

Korea has strengthened existing methods of stakeholder engagement and complemented them with online platforms. RIA has been significantly amended via the launch of e-RIA, which is aimed at increasing the quality of RIA whilst at the same time lessening the burden of preparing RIA. There have also been improvements as Korea has moved towards a much more systematic basis for the sun-setting of regulations. However, RIA does not apply to regulations initiated by the National Assembly. More potential gains from the improvements to Korea’s regulatory management practices could be realised if RIA also applied to laws initiated by the National Assembly, which accounts for approximately 90% of primary laws.

So while it is worth noting that some countries have improved their regulatory management practices since 2014, more fundamentally, much remains to be done in order to fully embed the 2012 Recommendation into OECD countries’ systems. The sections below provide a more detailed overview of progress in key areas of the 2012 Recommendation.

Stakeholder engagement

Engaging with those concerned and affected by regulation is fundamental to improve the design of regulations, enhance compliance with regulations and increase public trust in government. Stakeholders include citizens, businesses, consumers, and employees (including their representative organisations and associations), the public sector, non-governmental organisations, international trading partners and other stakeholders (OECD, 2012[1]).

By engaging with stakeholders – who can contribute their own experiences, expertise, perspectives and ideas to the discussion – governments gain valuable information on which to base their policy decisions. Information from stakeholders can help to avert unintended effects and practical implementation problems of regulations. Tapping into the knowledge of stakeholders is also useful in connection with RIA to collect and check empirical information for analytical purposes, identify policy alternatives, including non-regulatory options and measure stakeholders’ expectations. Furthermore, stakeholders can provide a quality check on the regulators’ assessment of costs and benefits (OECD, Forthcoming[9]).

Meaningful stakeholder engagement in the development of regulation is expected to lead to higher compliance and acceptance of regulations, in particular when stakeholders feel that their views were considered, they received an explanation of what happened with their comments, and they feel treated with respect (Lind and Arndt, 2016[10]). Pro forma consultation without any actual interest in the views of stakeholders because a decision has already been made or failure to demonstrate that consultation comments have been considered may have the opposite effect.

Recent trends in stakeholder engagement

Countries improved their practices with respect to primary laws to a greater extent than with respect to subordinate regulation. Improvements to the transparency of the system – including public access to information on planned consultations; comments received by stakeholders during the consultation phase; as well as on replies to consultation comments – account for most of this change, followed by some slight improvements in the methodology of stakeholder engagement including more engagement at earlier stages of the development of regulations (Figure 2.6 and Figure 2.7).

Notes: Data for OECD countries is based on the 34 countries that were OECD members in 2014 and the European Union. Data on new OECD member and accession countries in 2017 includes Colombia, Costa Rica, Latvia and Lithuania. The more regulatory practices as advocated in the 2012 Recommendation a country has implemented, the higher its iREG score. The indicator only covers practices in the executive. This figure therefore excludes the United States where all primary laws are initiated by Congress. *In the majority of OECD countries, most primary laws are initiated by the executive, except for Mexico and Korea, where a higher share of primary laws are initiated by the legislature.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814046

Notes: Data for OECD countries is based on the 34 countries that were OECD members in 2014 and the European Union. Data on new OECD member and accession countries in 2017 includes Colombia, Costa Rica, Latvia and Lithuania. The more regulatory practices as advocated in the 2012 Recommendation a country has implemented, the higher its iREG score.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814065

Countries which undertook substantive reforms include Iceland, Italy, Israel, Korea, as well as the European Union.

-

Since 2017, Iceland has required early stage consultation with the general public on a legislative intent document and preliminary RIA prior to drafting a law as well as public consultation on the full draft law and RIA before being presented to Cabinet.

-

Italy improved the transparency and forward planning of its consultation system, introducing for example open consultation on draft ex post evaluation ministerial plans.

-

Israel opened up consultation more widely to the general public and connected it to the RIA system, and Korea strengthened their online consultation system in 2015 to allow the general public to submit opinions on draft regulatory bills and RIAs and to access all consultations through a central website.

-

The European Commission has introduced consultation on inception impact assessments and roadmaps in the early stages of the development of legislation. The EC also consults on major aspects of impact assessments and evaluations, and allows stakeholders to comment won draft legislative proposals after the approval by the College of Commissioners and to make suggestions for simplification and review of EU legislation through the REFIT Platform.

On average, stakeholder engagement practices have not improved much in OECD countries though and most countries still have important room for improvement in implementing the 2012 Recommendation with respect to stakeholder engagement. Countries still score highest on systematic adoption and lowest on oversight and quality control, i.e. they have the formal requirements for stakeholder engagement in place yet are lacking the institutional structure to ensure it functions well in practice.

Requirements to conduct stakeholder engagement in the development of primary laws and subordinate regulations

Almost all OECD countries have entrenched stakeholder engagement in their rule-making process by establishing and expanding formal requirements to consult on new laws and regulations (Figure 2.8).

In a number of countries, existing consultation requirements have been expanded since 2014 to cover all new primary laws, where previously the approach was less systematic.

Since 2014, only one additional country has established consultation requirements for the development of subordinate regulations. Overall, requirements are less stringent than for primary laws, i.e. focussing only on some or major subordinate regulations in a third of OECD countries.

Note: Data is based on 34 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814084

Consultation at different stages of rule making

A great majority of OECD countries seem to systematically consult with stakeholders on all or major laws and regulations under development, suggesting that formal requirements are implemented in practice in the vast majority of cases.

While most consultation efforts continue to focus on later stages of the rule-making process, i.e. when a preferred solution has been identified and/or a draft regulation been prepared, the number of countries engaging with stakeholders at an early stage has increased (Figure 2.9). However, the engagement at this stage is not systematic in the vast majority of countries.

In line with less stringent formal requirements, in some countries consultation practices are less developed for subordinate regulations than for primary laws.

Note: Data is based on 34 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814103

Documents available to support stakeholder engagement

OECD countries make a number of different documents available to support stakeholder engagement at the different stages of the rule-making process (Figure 2.10 and Figure 2.11). Countries tend to use these documents more systematically at the later stage of the rule-making process, i.e. when a preferred solution has been identified and/or a draft regulation been prepared.

While already in 2014 a majority of OECD countries used the draft text of a regulation to support stakeholder consultation at a later stage, countries tend to use this practice more frequently in recent years.

OECD countries also increasingly make RIA available to support stakeholder engagement. However, governments continue to publish RIA more frequently when the preferred solution has been identified, rather than using RIA to inform stakeholders about the nature of the problem and to inform discussions on possible solutions.

Note: Data is based on 34 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814122

Note: Data is based on 34 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814141

Stakeholder engagement in ex post evaluation

A vast majority of OECD countries continue to use ongoing mechanisms by which the public can make recommendations to modify, provide feedback or dispute specific regulations.

However, the use of stakeholder engagement to inform ex post evaluations is far less systematic. Only a minority of the countries surveyed regularly engage with stakeholders when evaluating existing regulations to gather potential suggestions for improvement. This illustrates that countries have some way to go before closing the regulatory cycle.

Note: Data is based on 34 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814160

Minimum periods for public consultation

A growing number of OECD countries have established minimum periods for consultation with the public, including citizens, business and civil society organisations on the development of laws and regulations (Figure 2.13).

Note: Data is based on 34 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814179

By 2017, a majority of countries systematically make use of such minimum periods with a view to ensuring stakeholders have sufficient time to provide meaningful input in the rule-making process. Generally, OECD countries allow for a minimum period of four weeks’ consultation, although there are both shorter and longer periods across members. For instance, Costa Rica, Hungary, Iceland, Lithuania, Poland, anwd Spain provide for shorter periods, while both Switzerland and the European Union have 12 week minimum periods.

Where such minimum periods exist, they are usually applied systematically, i.e. for all or major primary laws or subordinate regulations.

Forms of stakeholder engagement

OECD countries continue to make use of a variety of tools to consult, both with the general public and in a more targeted approach with selected stakeholders (Figure 2.14).

The most popular forms of stakeholder engagement have remained the same: Governments continue to make use of the internet to actively seek feedback from the general public and of advisory groups or preparatory committees to benefit from the expertise of specific groups. Formal consultation with selected groups such as social partners remains a key part of the system in most OECD countries. While countries make increasing use of physical public meetings to complement web-based consultations with the broader public, fewer use virtual public meetings to engage with stakeholders on plans to regulate.

Note: Data is based on 34 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814198

Use of ICTs to engage with stakeholders at different stages of rule making

The use of ICTs by OECD countries to engage with stakeholders throughout the regulatory process is well established and continues to increase (Figure 2.15). The most frequent use of ICTs is to gather feedback from the public on draft regulations and to consult on plans to change existing regulations. Countries make less use of ICTs to consult on plans to regulate and on finalised regulations with a view to ensure stakeholders are engaged throughout the regulatory cycle and not only at one specific stage.

Note: Data is based on 34 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814217

However, information is often dispersed across websites making it hard for stakeholders to find. Websites could be better integrated and linkages between different sites could be improved. The number of countries that have recognised the importance of having a central website listing all ongoing consultations has increased since 2014 to about half of OECD countries.

Forward planning

The number of OECD countries publishing a list of regulations to be prepared, changed or repealed online in the next six months or more has increased, but it is not yet established as a consistent practice across the membership. A majority provides forward planning by publishing such lists on primary laws and around one third of countries do so for subordinate regulations (Figure 2.16). Informing the public more generally about forthcoming consultations is not systematically undertaken although it has slightly improved since 2014 (Figure 2.17).

Note: Data is based on 34 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814236

Note: Data is based on 34 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814255

Feedback and use of consultation comments

OECD countries have put in place mechanisms to ensure the transparency of the consultation process and to effectively integrate it into the regulatory process.

For instance, the number of countries that publish at least for some regulations the views of participants expressed during the consultation has further increased (Figure 2.18). Similarly, most countries include views from consultation in the RIA or pass them on to decision makers in some other way to make sure stakeholders’ feedback effectively feeds into the decision-making process. More broadly, there may be synergies that countries can avail themselves of by incorporating both ex ante and ex post consultations on a central website.

Only a minority of OECD countries provide stakeholders with feedback as to how their input was used in the rule-making process by publishing a response to consultation comments online, and the number has seen a slight decrease for subordinate regulations. As has been found previously, receiving an explanation is a key element for stakeholders to feel included and fairly treated in their interaction with government (Lind and Arndt, 2016[10]).

Note: Data is based on 34 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814274

Regulatory impact assessment (RIA)

Regulatory impact assessment (RIA) provides crucial information to decision makers on whether and how to regulate to achieve public policy goals (OECD, 2012[1]). It is challenging to develop “correct” policy responses which also maximise societal well-being. It is the role of RIA to help assist with this, by critically examining the impacts and consequences of a range of alternative options. Improving the evidence base for regulation through RIA is one of the most important regulatory tools available to governments (OECD, 2012[1]).

A well-functioning RIA system can assist in promoting policy coherence by clearly illustrating the inherent trade-offs within regulatory proposals. It does this by showing the efficiency and distributional outcomes of regulation. RIA also has the ability to reduce regulatory failures: for example RIA can illustrate that reducing risks in one area may create risks for another. RIA can also reduce regulatory failure by demonstrating where there is no case for regulating, as well as highlighting the failure to regulate when there is a clear need (OECD, 2009[11]).

Recent trends in RIA

Compared to the 2014 results, OECD members on average improved their RIA practices in relation to subordinate regulations to a greater extent than in relation to primary laws, reflecting the larger scope for improvement in delegated legislation practices (Figure 2.19 and Figure 2.20).

In absolute terms, the area of systematic adoption of RIA was most improved between 2014 and 2017 in relation to primary laws. Systematic adoption was already the area where countries scored best in relation to RIA in 2014, and this has continued in 2017. Systematic adoption assesses whether there are developed formal requirements for RIA which includes proportionality and institutional arrangements (OECD, 2015[8]).

The next best improvement between 2014 and 2017 was in relation to oversight and quality control. Oversight and quality control measures whether the functions are in place to monitor the practice of RIA as are the requirements to assure the quality of the analysis (OECD, 2015[8]). Compared to the other composite indicators, OECD members have made more of an effort to improve their oversight and quality control of RIA. Despite this improvement, it still remains the least applied element overall.

Countries which undertook substantive reforms include Chile, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Norway, and the Slovak Republic.

-

In Chile, the Government issued a Presidential Instruction which for the first time introduced the obligation to carry out RIA, focussing on productivity, for the economic ministries.

-

Since the publication of the Government Resolution in late 2014, Israel has provided stricter rules and guidance for RIA, so as to provide a solid basis for a whole-of-government regulatory policy, although the focus is mainly on reducing regulatory burdens.

-

Italy has introduced selection criteria for significant regulations, and attempted to expand its focus of analysis to different types of impacts, for example considering economic, social, and environmental impacts.

-

Japan has made significant efforts to improve its regulatory environment. In 2017 it revised its Implementation Guidelines for Policy Evaluation of Regulations, which updates the 2007 guidelines and continues to highlight the importance of conducting a thorough impact assessment of a policy, including the various techniques and processes that ministries can adopt.

-

To increase the quality of RIA and lessen the burden of preparing RIA statements in Korea, e-RIA was launched in May 2015. It provides the public officials who prepare RIAs the possibility to automatically obtain the necessary data for cost-benefit analysis, and a sufficient amount of descriptions and examples for all fields.

-

Norway improved its standard procedure for developing regulations by updating the Instructions for Official Studies and Reports in 2016. The Instructions establish new thresholds for determining when a simplified versus full analysis is required.

-

In the Slovak Republic, a whole-of-government approach to regulatory policy making was instituted via the introduction of the RIA 2020 – Better Regulation Strategy. This has helped to strengthen the methodological basis for assessing a variety of economic impacts. In addition, the Permanent Working Committee responsible for overseeing the quality of regulatory impact assessments was established in 2015 at the Ministry of Economy.

Notes: Data for OECD countries is based on the 34 countries that were OECD members in 2014 and the European Union. Data on new OECD member and accession countries in 2017 includes Colombia, Costa Rica, Latvia and Lithuania. The more regulatory practices as advocated in the 2012 Recommendation a country has implemented, the higher its iREG score. The indicator only covers practices in the executive. This figure therefore excludes the United States where all primary laws are initiated by Congress. * In the majority of OECD countries, most primary laws are initiated by the executive, except for Mexico and Korea, where a higher share of primary laws are initiated by the legislature.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814293

The largest improvements in subordinate regulations came from countries that had improved their application of RIA to subordinate regulations more generally, i.e. the improvements were across the four areas. Those countries were Israel, Italy, Japan, and Korea, which was a reflection of their RIA reforms more broadly outlined above.

Notes: Data for OECD countries is based on the 34 countries that were OECD members in 2014 and the European Union. Data on new OECD member and accession countries in 2017 includes Colombia, Costa Rica, Latvia and Lithuania. The more regulatory practices as advocated in the 2012 Recommendation a country has implemented, the higher its iREG score.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814312

Although a number of member countries have improved their RIA systems between 2014 and 2017, overall the improvements are marginal. As was foreshadowed in the previous Regulatory Policy Outlook (OECD, 2015[8]), the largest gains for countries from implementing a well-functioning RIA system will come from strengthening transparency practices and oversight. That is still the case today as it was then. Much more needs to be done to fully embed the 2012 Recommendation (OECD, 2012[1]) in member countries’ RIA systems.

Adoption of RIA: Formal requirements and practice

RIA is now required in almost all OECD countries for the development of both primary laws and subordinate regulations. The scope of the requirement has slightly changed, with less countries requiring RIA for all regulations, in line with a more proportionate approach to impact assessment (Figure 2.21).

While implementation still lags behind, the gap between requirement and practice seems to have reduced since 2014 and is smaller for primary laws than for subordinate regulation (Figure 2.22).

Note: Data is based on 34 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814331

Note: Data is based on 34 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814350

Exceptions to RIA and consequences of not conducting RIA

More than one-third of OECD members have exceptions to conducting RIA (Figure 2.23), indicating that countries are improving in adopting a proportionate approach to analysing regulatory proposals. Nevertheless, it is important to ensure that assessments are able to be provided where appropriate, and on that point it is worth noting that there has been an overall increase in the types of exceptions available.

Note: Data is based on 34 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814369

However, the consequences of not conducting RIA in circumstances where it was required are limited. Only in eight countries is there a requirement to undertake a post-implementation review in the event that RIA does not take place where it ought to have (Figure 2.24).

Note: Data is based on 34 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814388

Threshold tests for RIA

Countries are moving towards a more proportionate approach to RIA (Figure 2.25). Although relatively few countries provide a threshold test for whether to undertake RIA, it is published in even less. Only Mexico, the United States and the European Union publish such information.

Note: Data is based on 34 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814407

The use of threshold tests for determining whether a full RIA as opposed to a simplified RIA is undertaken has increased for both primary laws and subordinate regulation, to around one third of OECD countries.

Analysis of costs, benefits and distributional effects

Countries increasingly quantify costs and benefits, in particular for primary laws (Figure 2.26 and Figure 2.27).

The number of OECD countries requiring the quantification of benefits for primary laws has increased since 2014 from 26 to 30. The scope of the requirement of quantifying costs has been extended with 25 compared to 23 countries requiring a quantification of costs for all primary laws and 20 compared to 18 for all subordinate regulation.

Quantification of benefits still lags behind quantification of costs. While in the majority of OECD countries quantification of costs is required for all regulations, quantification of benefits is often only required for some regulations. The identification of distributional effects of regulation is now required in less countries than in 2014, and its scope of application has been reduced to fewer regulations (Figure 2.28).

Note: Data is based on 34 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814426

Note: Data is based on 34 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814445

Note: Data is based on 34 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814464

Types of impacts assessed in RIA

For most types of impacts, the number of countries requiring an assessment has slightly increased (Figure 2.29). Economic impacts, such as on competition and on small businesses, impacts on the environment and on the public sector as well as the budget remain the most frequently assessed types of impacts.

Note: Data is based on 34 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814483

Despite an increase, the analysis of social impacts, e.g. on income inequality and poverty remains comparably less developed across countries. Likewise, the assessment of impacts on foreign jurisdictions remains low compared to other types of assessment, with about nearly two-thirds of OECD countries requiring an assessment at least for some regulations.

Interestingly and in line with a dynamic technological environment, there has been a significant increase of countries assessing the impacts of new regulations on innovation, which is now done in 29 OECD countries.

Ex post evaluation

The stock of laws and regulations has grown rapidly in most countries. However not all regulations will have been rigorously assessed ex ante, and even where they have, not all effects can be known with certainty in advance. Regulations should be periodically reviewed to ensure that they remain fit for purpose.

Many of the features of an economy or society of relevance to particular regulations will change over time (OECD, 2017[12]). For instance, markets change, technologies advance and preferences, values and behaviours within societies evolve. And the very accumulation of regulations over time can lead to interactions that exacerbate costs or reduce benefits, or have other unintended consequences (OECD, Forthcoming[7]).

It is also evident that the stock of regulations will generally be much larger than the flow, with proportionately greater aggregate impacts. Even a small improvement in the quality of the regulatory stock, therefore, could bring large gains to society (OECD, Forthcoming[7]).

The 2012 Recommendation therefore calls on governments to “[c]onduct systematic programme reviews of the stock of significant regulation against clearly defined policy goals, including consideration of costs and benefits, to ensure that regulations remain up to date, cost justified, cost effective and consistent, and deliver the intended policy objectives.”

Evaluations of existing regulations can also produce important learnings about ways of improving the design and administration of new regulations – for example, to change behaviour more effectively. In this way, ex post reviews complete the ‘regulatory cycle’ that begins with ex ante assessment of proposals and proceeds to implementation and administration (OECD, 2015[8]; OECD, Forthcoming[7]).

Recent trends in ex post evaluation

Despite the high benefits in reforming the stock of regulation ex post evaluation systems are still rudimentary in most OECD countries and changes since 2014 are marginal on average (Figure 2.30 and Figure 2.31). Most improvements were made to oversight and quality control and the systematic adoption of ex post evaluation. Despite these improvements however, oversight and quality control to ensure effective implementation continue to be underdeveloped.

Notes: Data for OECD countries is based on the 34 countries that were OECD members in 2014 and the European Union. Data on new OECD member and accession countries in 2017 includes Colombia, Costa Rica, Latvia and Lithuania. The more regulatory practices as advocated in the 2012 Recommendation a country has implemented, the higher its iREG score.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814502

Countries which undertook substantive reforms of their ex post evaluation systems over the last years include Austria, Denmark, France, Italy, Japan, Korea, and the United States.

-

Austria has introduced mandatory ex post evaluation for major laws and regulations.

-

Denmark has introduced several principle-based ex post reviews, for example on the overlaps between local, regional and federal regulation, and the Danish Business Forum now conducts in-depth reviews of regulations in different policy areas.

-

France has engaged in important simplification efforts, including a public stocktake exercise, and has released in 2017 new guidelines for the evaluation of public policies.

-

Italy introduced a new set of procedures for ex post evaluation, including criteria to select major laws and regulations, and strengthened its institutional settings.

-

Japan introduced a threshold test for ex post evaluation and improved its methodology and oversight of ex post evaluation.

-

Korea has recently subjected its ex post evaluation system to its ex ante RIA requirements, started a series of in-depth reviews of regulations in specific policy areas, made ex post evaluations publicly available, introduced quality control and publishes now every year a report on the performance of the ex post evaluation system.

-

The United States has introduced a stock-flow linkage rule and the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) has issued guidance to implement this rule, requiring ex post evaluation of regulations. OIRA also reviews the quality of ex post evaluations.

Notes: Data for OECD countries is based on the 34 countries that were OECD members in 2014 and the European Union. Data on new OECD member and accession countries in 2017 includes Colombia, Costa Rica, Latvia and Lithuania. The more regulatory practices as advocated in the 2012 Recommendation a country has implemented, the higher its iREG score.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814521

Requirements for ex post evaluation

The number of countries with formal requirements for ex post evaluation has only slightly increased and it is still not mandatory in one third of OECD countries (Figure 2.32). Furthermore, in most countries where a requirement exists, it does not apply systematically to all or major regulations. OECD countries have put in place different types of requirements to trigger ex post evaluations, including “thresholds”, “sunsetting” clauses or automatic evaluation requirements. A growing number of countries conduct evaluations of regulations on similar issues as a “package”.

Notes: Data for OECD countries is based on the 34 countries that were OECD members in 2014 and the European Union. Data on new OECD member and accession countries in 2017 includes Colombia, Costa Rica, Latvia and Lithuania.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814540

Methodology of ex post evaluation

Overall, a majority of OECD countries are still yet to establish a comprehensive methodology for ex post evaluation (Figure 2.33). Furthermore, there has been no noticeable improvement across the different dimensions since 2014.

Assessing whether the regulation’s goals have been met is an integral part of a sound ex post evaluation system. However, this is part of the standard methodology for ex post evaluation only in around one-third of OECD countries.

Notes: Data for OECD countries is based on the 34 countries that were OECD members in 2014 and the European Union. Data on new OECD member and accession countries in 2017 includes Colombia, Costa Rica, Latvia and Lithuania.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814559

Ad hoc reviews of the stock of regulation conducted in the last 12 years

Principle-based reviews continue to be the most frequently used type of ad hoc review of the stock of regulation (Figure 2.34). However, there has been a significant increase in countries conducting public stocktakes and, to a lesser degree, “in-depth” reviews.

Note: Data is based on 34 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814578

Ongoing management of regulation

Since 2014, more OECD countries make use of ‘stock-flow linkage’ rules to remove or rationalise existing regulations (e.g. one-in X-out rules), but remain a minority overall (Figure 2.35).

The first OECD country to formalise such approach was the United Kingdom in 2011, with other countries such as Canada and Germany following in 2012 and 2015, respectively. More recently, France, Korea, the United States and Mexico have introduced their own versions of regulatory offsetting. While there are a number of countries presently experimenting with stock-flow linkage rules, or considering introducing them, the overall number remains marginal (OECD, Forthcoming[13]).

Note: Data is based on 34 OECD member countries and the European Union.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

StatLink https://doi.org/10.1787/888933814597

References

[3] Arndt, C. et al. (2015), “2015 Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance: Design, Methodology and Key Results”, OECD Regulatory Policy Working Papers, No. 1, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jrnwqm3zp43-en.

[5] Arndt, C., P. Davidson and E. Thomson (forthcoming), “Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance 2018”, OECD Regulatory Policy Working Papers, OECD, Paris.

[4] Arndt, C. et al. (2016), “Building Regulatory Policy Systems in OECD Countries”, OECD Regulatory Policy Working Papers, No. 5, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/dbb1a18f-en.

[6] Australia Productivity Commission (2006), “Potential Benefits of the National Reform Agenda”, Report to the Council of Australian Governments, https://www.pc.gov.au/research/completed/national-reform-agenda/nationalreformagenda.pdf (accessed on 07 June 2018).

[10] Lind, E. and C. Arndt (2016), “Perceived Fairness and Regulatory Policy: A Behavioural Science Perspective on Government-Citizen Interactions”, OECD Regulatory Policy Working Papers, No. 6, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/1629d397-en.

[12] OECD (2017), “Closing the regulatory cycle: effective ex post evaluation for improved policy outcomes”, http://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/Proceedings-9th-Conference-MRP.pdf.

[8] OECD (2015), OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2015, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264238770-en.

[1] OECD (2012), Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264209022-en.

[11] OECD (2009), Regulatory Impact Analysis: A Tool for Policy Coherence, OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264067110-en.

[7] OECD (Forthcoming), Best Practice Principles on Reviewing the Regulatory Stock, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[9] OECD (Forthcoming), Best Practice Principles on Stakeholder Engagement in Regulatory Policy, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[13] OECD (Forthcoming), One-in X-Out: A Discussion Note, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[2] OECD/EU/JRC (2008), Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators: Methodology and User Guide, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264043466-en.